Abstract

The toxicity of aluminum (Al) in acidic soil limits global crop yield. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-like gene superfamily has functions and structures related to transportation, so it responds to aluminum stress in plants. In this study, one half-size ABC transporter gene was isolated from wild soybeans (Glycine soja) and designated GsABCI1. By real-time qPCR, GsABCI1 was identified as not specifically expressed in tissues. Phenotype identification of the overexpressed transgenic lines showed increased tolerance to aluminum. Furthermore, GsABCI1 transgenic plants exhibited some resistance to aluminum treatment by ion translocation or changing root components. This work on the GsABCI1 identified the molecular function, which provided useful information for understanding the gene function of the ABC family and the development of new aluminum-tolerant soybean germplasm.

Keywords: GsABCI1, ABC transporter, aluminum tolerance, wild soybean, overexpression

1. Introduction

Acidic soils account for more than 30% of land area worldwide, particularly in the tropics and subtropics [1,2,3,4]. In soils with pH below 5, insoluble aluminum is mainly released into the soil in the form of soluble Al3+, where it will promptly inhibit the elongation of plants and the absorption of water and nutrient by roots, eventually leading to the loss and quality decline of crop products [5,6,7]. In fact, in an acidic soil environment, the toxicity of aluminum has become the main abiotic stress and limiting factor for crop production [8,9,10]. In order to resist the toxicity of aluminum, most plant species have adopted mechanisms in long-term evolution, namely, external exclusion and internal tolerance mechanisms. Exclusion mechanisms have a range of processes in plants, including the secretion of carboxylic acids (citrate, oxalate, malate), conservation of the cell wall, secretion of inorganic phosphorus, transmembrane efflux, and regulation of rhythmic pH variation [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The internal mechanism is to sequester or isolate Al to vacuoles and other areas insensitive to aluminum [18,19,20,21,22].

At present, aluminum tolerance gene families have been identified in plant species. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter protein superfamily comprises diverse, complex, and ubiquitous proteins [23]. The Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, and soybean genomes contain an estimated 131, 121, and 261 members of the ABC family, respectively, and these proteins are divided into 8 basic subfamilies (ABCA-ABCG and ABCI) based on the domain organization and homologous relationship [24,25,26]. ABC transporters are a family of membrane-bound proteins that mediate transport across biofilms by hydrolyzing ATP. They contain a conservative cytoplasmic domain, called the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) (also known as an ATP-binding cassette) [26]. In addition to this domain, ABC protein also includes one or two hydrophobic transmembrane domains (TMDs). Recently, studies have suggested that the ABC transporter proteins in plants not only participate in the transport of alkaloids, steroids, phenols, lipids, metal ions, hormones, salts, organic acids, and xenobiotics but also contribute to the modulation of ion channels and plant–pathogen interactions [27,28,29,30,31,32]. In some studies, several members of the ABC transporter superfamily were identified as being involved in enhancing resistance to aluminum toxicity. For instance, in rice, aluminum toxin-sensitive proteins OsSTAR1 and OsSTAR2 were identified, which are responsible for UDP-glucose efflux [33]. It has been speculated that the transported UDP-glucose is the precursor substance of hemicellulose and pectin of cell wall components, thereby exerting the modification function of the cell wall, limiting the accumulation of aluminum, and reducing the toxicity of aluminum [33,34,35]. Similarly, FeSTAR1, FeSTAR2, and SbSTAR1 have similar functions in buckwheat and sweet sorghum [36,37]. Larsen discovered three aluminum-sensitive proteins encoded by an ABC transporter gene (ALS3), which was necessary for the redistribution of Al3+ from highly sensitive tissues [38]. Its homologous genes FeALS3 and GmALS3 were also identified in buckwheat and soybean [39,40]. Moreover, some ABC transporter genes, such as HvABCB25, CcABCG7, FeALS1.1, FeALS1.2, and OsALS1, were also isolated, conferring aluminum tolerance in wild barley, pigeon pea, buckwheat, and rice, separately [41,42,43]. Among them, OsALS1 encodes an aluminum transporter protein, which is supposed to work cooperatively with OsNrat1 and participate in aluminum translocation [43,44].

Soybean (Glycine max) is one of the most important oil and protein crops in the world, but its genetic diversity has decreased in the process of artificial domestication and breeding selection from wild soybean to cultivated soybean [45]. Wild soybean (G. soja) is believed to have a broader genetic basis and a stronger tolerance for abiotic stress, which provides opportunities to identify the potential genes related to Al resistance [46]. In the current study, a half-size ABC transporter gene was isolated from the BW69 line (Al-resistant) of wild soybean (G. soja), named GsABCI1, and the response of the gene expression pattern to aluminum treatment was detected by qPCR. The function of GsABCI1 was identified and subjected to subcellular localization and phenotypic analysis of root components as well as transgenic overexpression lines from A. thaliana and G. max. We hypothesized that GsABCI1 could improve the aluminum tolerance of wild soybean through aluminum translocation or alteration of root composition.

2. Results

2.1. GsABCI1 Encodes an ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Protein

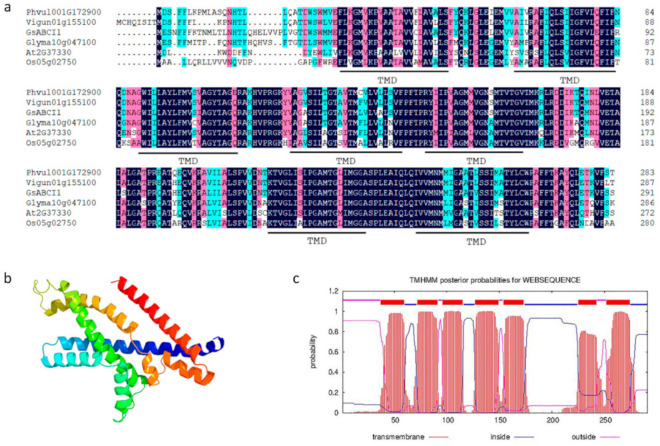

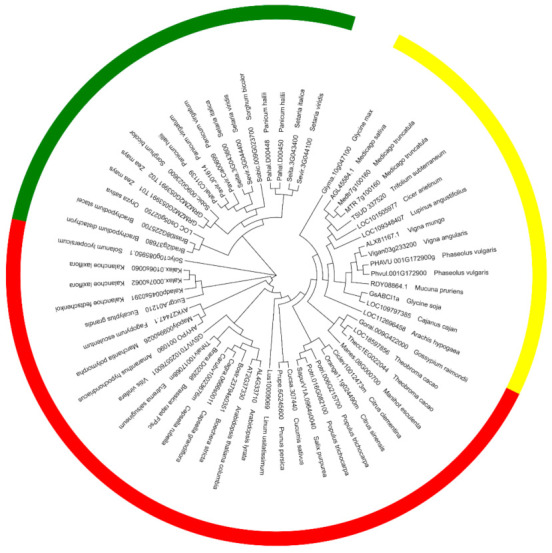

Based on the gene expression profile of aluminum-resistant wild soybean (unpublished data), an aluminum-induced gene encoding ABC transporter protein was cloned. A BLAST search using the ABC protein sequence identified two unique homologues, Glyma03g175800 (GmABCI1) and Glyma10g047100 (GmABCI13), in the soybean genome of Williams82. By sequence alignment, we found that only two base sequences located at 567 and 720 were mutated in Glyma03g175800, Therefore, we named the isolated gene GsABCI1 according to the Human Genome Organization (HUGO) scheme and previous studies [25]. The full-length genome sequence of GsABCI1 included 3 exons and 2 introns with a cDNA of 1163 bp in length, including a 678 bp open reading frame (ORF), and encodes a peptide of 291 amino acids (Additional file S1: Table S1). At the amino acid level, GsABCI1 shows 76% and 62% identity with AtALS3 (At2g37330, A. thaliana) and OsSTAR2 (Loc_Os01g0674700, Oryza sativa), respectively. Phvul.001G172900 from Phaseolus vulgaris shared 92.8% identity with GsABCI1 and is the closest homologue of Leguminosae sp. Prediction using TMHMM (Server v. 2.0) and Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine v2.0 showed that GsABCI1 is a permease protein that has seven predicted transmembrane domains (TMDs, 37–59, 72–91, 96–115, 127–149, 154–173, 225–242, 252–274) without nucleotide-binding domains (NBD), and therefore was classified as a half-size ABC transporter. (Figure 1c). According to the phylogenetic analysis, GsABCI1 homologues exist in different species including dicotyledons and monocotyledons. GsABCI1 is clustered with legume species, so it is speculated that the genes of the ABC family are conservative to some extent in a wide range of legume species (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

(a) Multiple sequence alignment and protein structure analysis of the GsABCI1 and ABC domain of other species. The line below the sequence indicates the predicted conserved trans-membrane domains (TMDs). The black part indicates the amino acids shared between the sequences. Phvul.001G172900: Phaseolus vulgaris; Vigun.01g155100: Vigna unguiculata; Glyma.10g175800: Glycine max; At2g37330: Arabidopsis thaliana; Os05g02750: Oryza sativa. (b) Prediction of the GsABCI1 protein structure model. One color represents one protein fold. (c) Prediction of the transmembrane domain of GsABCI1 protein. Red line: transmembrane structure, blue line: inside the membrane, and purple line: outside the membrane.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the GsABCI1 protein and other ABC transporter proteins. The different colors represent the species type. Yellow, red, and green represent legume, dicotyledons (except the legume), or monocotyledons.

2.2. GsABCI1 Expression Responses to Aluminum Stress in Wild Soybean (Glycine soja)

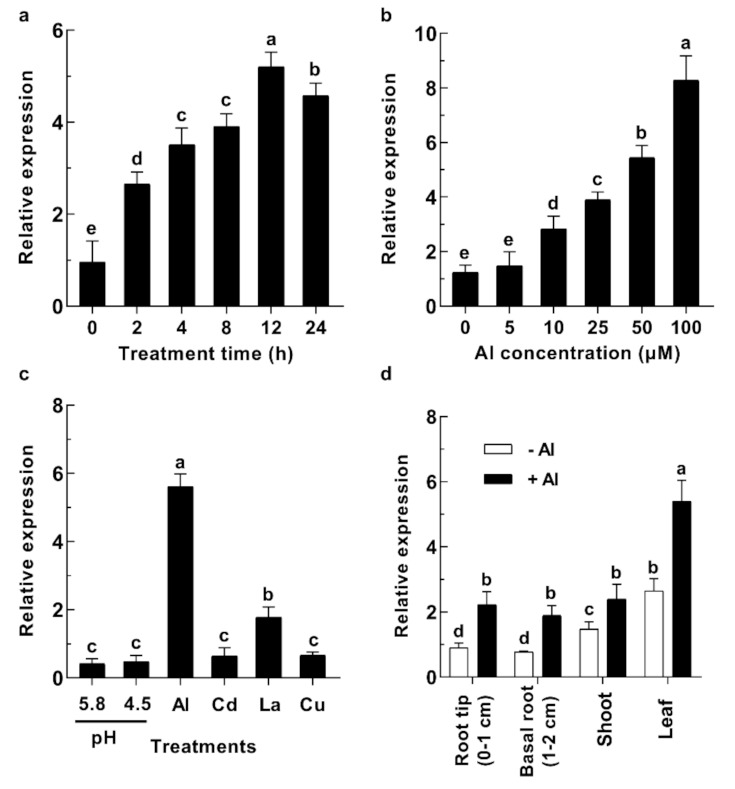

The time-response experiment revealed that GsABCI1 was expressed in the root within 2 h of Al treatment and that the expression level increased significantly with prolonged treatment time. However, the expression level began to decline after 12 h of treatment (Figure 3a). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 3b, the expression of GsABCI1 in the roots was prominently increased with increasing Al concentration after eight hours of exposure. In the experiment examining the response to metals and different pH, the expression of GsABCI1 was induced by Al and lanthanum (La) but not by copper (Cu) or cadmium (Cd), and the induced expression was dramatically lower with La than Al. Between the two pH values, the expression of GsABCI1 was not increased with pH 4.5 (Figure 3c). In the tissue-specific expression experiment, the expression of GsABCI1 was concentrated in the root, shoot, and leaf with or without Al exposure, and the expression in leaves was higher than that in roots (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

The detection of the GsABCI1 expression pattern. (a) Time-dependent expression pattern of GsABCI1. Plants were treated with a solution containing 50 μM AlCl3 for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Root tips (0–1 cm) were collected for qPCR after different time treatments. (b) Dose-dependent expression pattern of GsABCI1. Plants were exposed to a solution containing 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, or 100 μM AlCl3 for 8 h. Root tips (0–1 cm) were collected for qPCR after 8 h in different Al treatments. (c) The GsABCI1 expression of response to metals and different pH values. Seedling plants were grown under different pH (pH 4.5, or 5.8) conditions or in solutions (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3, 23 μM CdCl3, 10 μM LaCl3, or 0.5 μM CuCl2 for 8 h. Root tips (0–1 cm) were collected for qPCR after 8 h in different treatments. (d) Tissue-specific expression pattern of GsABCI1. Seedling plants were cultivated in a solution with 0 or 50 μM AlCl3 for 12 h. Root tips (0–1 cm), Basal roots (1–2 cm), shoots, and leaves were collected for qPCR after treatment. The expression levels of all candidate genes were determined by using the 2−ΔΔct method. The data are the means ± SDs (n = 3). The different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

2.3. Generation and Detection of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines

To identify the function of GsABCI1, the vector containing a 35S strong promoter original was constructed, and several lines of the transgenic plant were obtained by staining and cotyledon node transformation, respectively. The transgenic T1 A. thaliana and G. max were transformed and confirmed by PCR identification with a specific primer for the amplification of the glufosinate-resistant genes (Additional file S2: Table S2). Combined with herbicide identification, the results demonstrated that the GsABCI1 was integrated into the genomes of recipient plants (Additional file S3: Figure S1). Three overexpression transgenic lines of each soybean and A. thaliana with high gene expression in the T3 generation as determined by qPCR were selected to study the Al tolerance phenotype of transgenic GsABCI1 plants.

2.4. Overexpression of GsABCI1 Enhances Phenotypic Tolerance to Aluminum

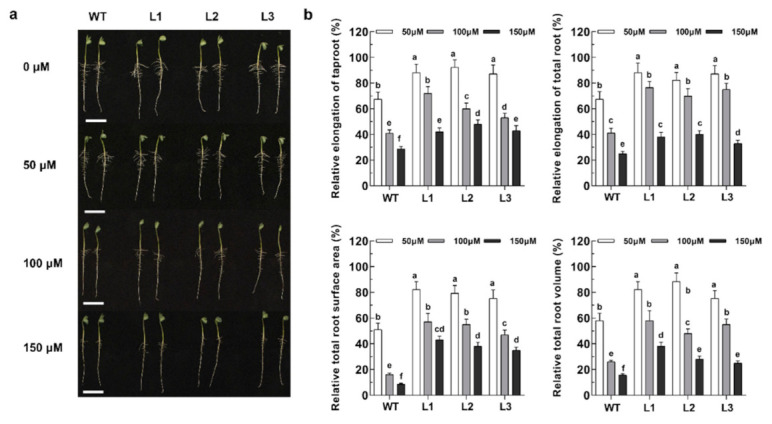

To compare the growth phenotypes of the wild type (WT) and three transgenic lines (L1, L2, L3) at physiologically relevant concentrations of Al, an Al dose–response analysis in solution culture was performed. As shown in Figure 4a, the root elongation of both the WT and transgenic soybean lines was inhibited to some extent by various concentrations of Al and the higher the concentration of Al was, the greater the suppression effect. However, the three transgenic lines were significantly less inhibited than the WT. For instance, when the Al concentration was 100 μM, the taproot elongation of WT was inhibited by 58%, while that of L1, L2, and L3 were inhibited by 28%, 44%, and 46%, respectively (Figure 4b). The auxiliary data describing the relative total area, relative total root length, and relative total volume illustrate that the root growth of the transgenic lines was less affected by the toxic compound than that of the WT under Al stress (Figure 4). In the presence of Al, both the WT and transgenic A. thaliana lines were severely inhibited under 150 μM Al treatment, but the relative root elongation of the transgenic A. thaliana was significantly higher than that of the WT under Al treatment (Additional file S4: Figure S2). Those results indicate that the overexpression of GsABCI1 in transgenic A. thaliana or G. max confers increased resistance to aluminum toxicity.

Figure 4.

Phenotypic detections of the GsABCI1 transgenic soybean lines. (a) Morphological analysis of the roots of the WT and three transgenic lines (L1, L2, L3). (b) Analysis of relative taproot elongation, relative total root elongation, relative total root surface area, and relative total root volume in the WT and three transgenic lines (L1, L2, L3). Soybean seedlings with consistent growth were identified and transferred into a 0.5 μM CaCl2 hydroponic solution (pH 4.5) containing 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM AlCl3 for 12 h. Photograph taken, scanned, and acquired data through Image J. Bar = 5 cm. The data are the means ± SDs (n = 16). The different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

2.5. GsABCI1 Involves the Translocation of Aluminum in Roots

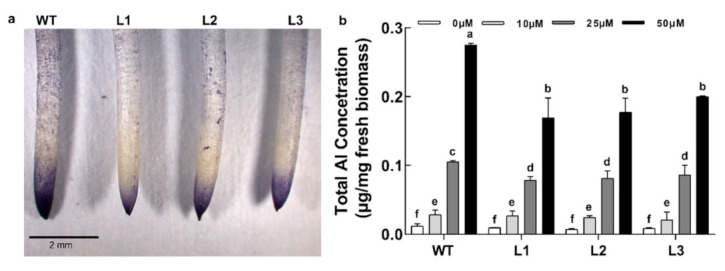

The roots of the soybean were stained with the aluminum indicator dye hematoxylin, and the total aluminum accumulation was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The diffusion pattern of surface-bound Al3+ in the transgenic lines was substantial and extended from the apical region to the mature region. The WT root had strong staining in a local area near the root tip (Figure 5a), which is the area where plants are sensitive to Al toxicity. Additionally, the ICP-MS quantification of Al accumulation showed slight differences in the total Al concentration in the roots (0–2 cm) of the WT and transgenic lines (Figure 5b). Generally, under high Al concentrations (25 or 50 μM), the Al3+ accumulation of the transgenic lines was less than that of the WT strain, but the difference was not significant under the low concentration (10 μM) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Analysis of Al accumulation patterns. (a) Al-treated (25 μM AlCl3 for 24 h) roots of WT and transgenic soybean lines were stained with hematoxylin, washed, and photographed. Bar = 2 mm. (b) The total Al accumulation in the roots. Soybean seedlings with consistent growth were transferred into a 0.5 μM CaCl2 hydroponic solution (pH 4.5) containing 0, 10, 25, or 50 μM AlCl3 for 24 h. The Al of the roots (0–6 cm) was extracted by 2N HCl and determined. The data are the means ± SDs (n = 12). The different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

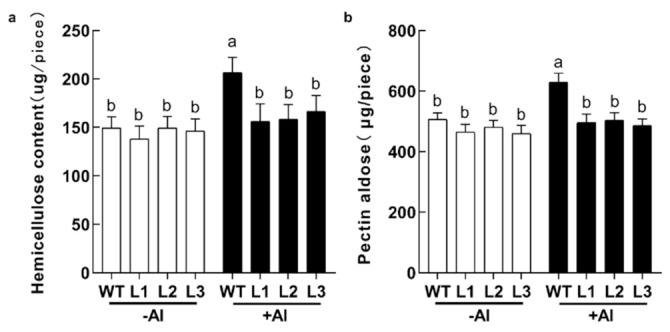

2.6. Root Component Changes of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines under Aluminum Stress

The soybean root cell wall has been recognized as the primary target of aluminum toxicity, with hemicellulos and pectin being the major constituents of the cell wall. The homologous gene of GsABCI1 was identified to be potentially involved in the transport of UDP-glucose and thus alter cell wall composition. Therefore, we analyzed whether the aluminum resistance of the transgenic lines was associated with hemicellulose and pectin aldose metabolism. As shown in Figure 6, the hemicellulose and pectin aldose contents of the GsABCI1 transgenic line were significantly lower than those of the wild type under aluminum treatment.

Figure 6.

Root component of the GsABCI1 transgenic soybean lines. (a) Hemicellulose content in the root cell wall of the wild type and three transgenic lines. (b) Hemicellulose or pectin aldose was extracted from the root cell wall of plants with or without 50 μM aluminum treatment. The data are the means ± SDs (n = 12). The different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

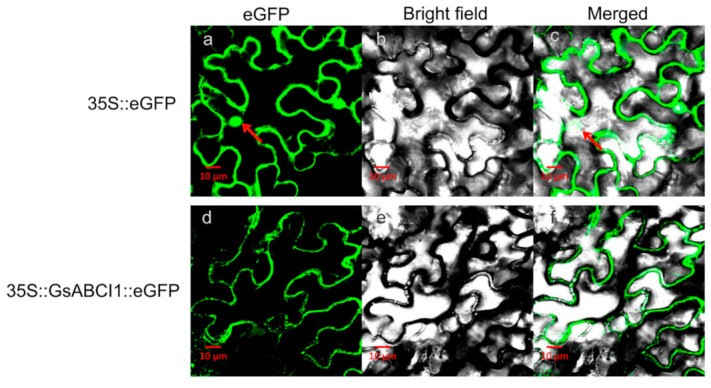

2.7. GsABCI1 Subcellular Localization in the Plasma Membrane

To determine the subcellular localization of GsABCI1, the GsABCI1-GFP fusion protein was transiently expressed in epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana. As shown in Figure 7a–c, GFP emitted green fluorescence throughout the whole cell. In contrast, the GsABCI1-GFP fusion protein had no signal in the nucleus but had a strong green fluorescent signal in the cell membrane (Figure 7d–f). In general, these results indicate that GsABCI1 protein is localized to the plasma membrane as predicted by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (accessed on 6 June 2021)).

Figure 7.

Subcellular localization of GsABCI1 in Nicotiana benthamiana cells. (a–c) Localization of 35S::eGFP in N. benthamiana leaf cells. (d–f) Localization of 35S:GsABCI1::eGFP in N. benthamiana leaf cells. Fluorescence signs in the epidermal cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy. The specific vector was transformed into N. benthamiana leaf by an infiltration method. (a,c) The arrows indicate the position of the nucleus.

3. Discussion

The toxicity of aluminum has a far-reaching impact on agriculture all over the world, which severely limits crop yields by inhibiting root growth and nutrient absorption [6,47,48,49]. At present, the function and mechanism of anti-Al-related genes in some plants have been identified, including AtALMT1, TaALMT1, GmALMT1, AtMATE, VuAAE3, TaMATE1, OsFRDL4, OsSTAR1, OsSTAR2, AtMGT1, OsNrat1, and AtSTOP1, which can provide basic data for elucidating the physiology and genetics of aluminum tolerance mechanisms [33,47,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. It has been found that the ABC transporter gene superfamily has the function of material transport related to plant responses to abiotic stresses, and plays a key role in plant physiology and development [25]. The ABCI subfamily is a unique ABC family in plants, which does not exist in animals [59]. It has been identified that gene members of many species are related to aluminum tolerance. OsSTAR1 and OsSTAR2 are members of the ABCI subfamily, which is one of the most important mechanisms of aluminum toxicity in rice [33]. In dicotyledonous plants Arabidopsis thaliana AtABCI16 and AtABCI17, the corresponding aluminum toxicity was also identified [59]. Larsen discovered Al-sensitive mutants and isolated the gene ALS3(At2g37330), which caused this phenomenon of Al insensitivity [38]. Soybean is one of the most widely cultivated crops in the world, and it is also an important source of human protein, oil, and animal feed. A few days ago, it was identified that the ABCI subfamily gene GmABCI13(Glyma.10g47100) was highly expressed in the soybean roots under aluminum stress, and it was also considered as the orthologous gene of ALS3, which indicated that the ABCI subfamily had extensive aluminum tolerance in plants [40]. In this study, we identified the ABCI subfamily gene GsABCI1 in wild soybean (G. soja) as being related to aluminum tolerance and speculated that it might be involved in the transportation of cell wall structural components.

By sequence alignment, GsABCI1 showed a high degree of homology with the already identified ABCI subfamily genes, especially with GmABCI13 (Figure 1a). GsABCI1, which contains the transmembrane domains of the ABCI transporter, the conservative transmembrane domain, is similar to its homologues and is assumed to have a similar function (Figure 1). The phylogenetic analysis of GsABCI1 protein and other ABC transporter shows that the GsABCI1 protein sequence was conserved among different species, especially among dicotyledons. It encodes a previously uncharacterized half-type ABC transporter system permease protein, which consists of seven transmembrane domains and does not contain an ATP-binding domain, which means that it must interact with other proteins to provide the energy needed to drive substrate movement [38,43,60]. This seems to be similar to the interaction between OsSTAR1 and OsSTAR2 in rice, and further research is needed [33].

While similar in structure to homologous ABC family genes, GsABCI1 still has its unique functions. The expression pattern of GsABCI1 shares many similarities with that of the dicot gene, At2g37330, but is different from that of the monocot gene, OsSTAR2 [33,49]. The expression of GsABCI1 is not limited to the roots like OsSTAR2 but is expressed in various tissues of the plant, especially in the stems and leaves (Figure 3d). After 12 h of aluminum stress, the expression level of GsABCI1 reached its maximum and the peak of the expression level was later than that of rice OsSTAR2. It was speculated that Al might first act on the binding of other substances or transcription factors in soybean root cells, and then induce the expression of GsABCI1 (Figure 3a) [61,62]. Furthermore, we speculated that the transmembrane domain of GsABCI1 may be the pathway of trivalent metal transport, because the expression of GsABCI1 is specifically increased by exposure of Al3+ and La3+ but not Cd2+ or Cu2+ (Figure 3c). The subcellular cells of the GsABCI1 protein were localized to the plasma membrane (Figure 7). Therefore, it is speculated that GsABCI1 may be involved in the transmembrane transport of some substances.

In order to further verify the role of GsABCI1 in aluminum resistance, GsABCI1 was transformed into cultivated soybean and A. thaliana. Compared with the treatment control, with the increase of the aluminum concentration, aluminum stress inhibited the elongation of the main root of wild-type and transgenic soybean or A. thaliana (Figure 4, Additional file S4: Figure S2). However, the relative root elongation and other root morphology data of transgenic lines were significantly higher than those of the wild type. Consistent with the speculation, the overexpression of GsABCI1 enhanced the tolerance of A. thaliana or soybean to aluminum. Similar abiotic stress phenotypes were also studied in other ABC genes of other crops. For example, SbSTAR1 enhanced the aluminum tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana by regulating hemicellulose [37]. In this study, the contents of hemicellulose and pectin aldose in GsABCI1 transgenic soybean lines and wild-type roots were also determined to study the response mechanism of soybean to aluminum stress, and the results were similar to previous studies [17,33,37,62,63,64,65,66]. We speculated that GsABCI1 transgenic soybean may enhance the tolerance of plants to aluminum stress by mediating the changes of hemicellulose and pectin aldose, but it does not change under the condition of aluminum treatment, which seems to be not directly mediated (Figure 6). The measurement of hematoxylin staining and aluminum accumulation showed that compared with the WT strain, the total aluminum accumulation in the root tip of transgenic strain decreased, while the total aluminum accumulation in the distal tip slightly decreased (Figure 5). Other researchers suggested that both ALS3 and ALS1 may be involved in the mechanism of aluminum movement in insensitive tissues or subcellular structures [38,60]. Therefore, it is speculated that GsABCI1 also mediates the loading or unloading of aluminum and its transportation from the root tip to the root elongation area or even to the aluminum-insensitive leaf area, thus enhancing the tolerance of plants to aluminum toxicity [67]. We speculated two possible mechanisms of GsABCI1-mediated aluminum tolerance, which may need further exploration. Consequently, further study on the function of the GsABCI1 gene will enrich our understanding of the mechanism of aluminum tolerance in plants.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growing Conditions

The seeds of wild soybean BW69 were obtained from the Guangdong Sub-Center of the National Center for Soybean Improvement (Guangzhou, China). To break dormancy and enhance germination, sterile seeds were treated with a sulfuric acid solution for 15 min, washed thoroughly with sterile double-distilled water (ddH2O) five times, and germinated in soil mixed with quartz sand and vermiculite (1:1) for two days. Uniformly germinated seeds were transferred to a hydroponic system (pH 5.8) containing 1/4 Hoagland’s solution at 25 °C, 60% relative humidity (RH), 550 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity, and 16 h/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod [68,69]. The nutrient solution was renewed every two days. After disinfection and vernalization, A. thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) and transgenic lines were grown in a greenhouse under the following conditions: 21–23 °C; 60% relative humidity; 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity; and 16 h/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod.

4.2. Isolation of the GsABCI1 Gene from Wild Soybean and Vector Construction

To isolate the GsABCI1 gene, total RNA was extracted from the roots of wild soybeans BW69 by TRNzol Reagent (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). The conversion to cDNA was performed by a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA eraser (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. Based on the previous analysis of acidic aluminum tolerance-related gene expression profiles (unpublished data), GsABCI1 was amplified by a specific primer (Additional file S2: Table S2). The PCR product was inserted into the pLB-simple vector and confirmed by sequencing. The above method referred to a previously described method [70].

For the overexpression of GsABCI1 in soybean and A. thaliana, the coding region of GsABCI1 was amplified using gene-specific primers with the XbaI site and SacI site (Additional file S2: Table S2). GsABCI1 was then cloned into the pTF101.1 binary vector with the phosphinothricin acetyltransferase (bar) resistance gene (encoding phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase, PAT, conferring resistance to glufosinate herbicide) as the plant selection marker, which was driven by a modified CaMV 35S promoter [71].

4.3. Generation of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines

The recombinant vector pTF101.1-GsABCI1 was transformed into agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (for A. thaliana) or EHA101 (for soybean) by electroporation (Gene Pulser Xcell™ Electroporation Systems, Hercules, California, US) and confirmed by PCR [72,73]. A. thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was used for transformation by the floral dip method [74]. The nationally approved soybean cultivar (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Beijing, China), Huachun6, was used as the recipient for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation, as previously described with slight modification [75,76,77]. In short, mature soybean seeds without spots were plated on Petri dishes and sterilized. After exposing the sample to airflow for two hours to remove the Cl2, the disinfected soybean seeds were sown in the germination medium (GM) for five days. The primary and shoot seed coats were removed from the germinated seeds, and the cotyledonary nodes were cut approximately 10 times with a scalpel. Afterward, the explants were infected for 30 min by immersion in a liquid with the Agrobacterium suspension and placed on cocultivation medium (CM) in a darkroom for three days. After cocultivation, the explants were washed and inserted into sprout-induced medium (SIM) with Timentin (Realtimes, Beijing, China) at 30–45° angles to induce shoots for two weeks under. Then, the hypocotyl of the explants was cut again and cultured on sprout-induced medium for another two weeks. The numerous induced shoots were transferred to sprout elongation medium (SEM) with Timentin for 2–8 weeks, and the new sprout elongation medium was changed every two weeks. The explants that grew larger than 3 cm were dipped in an indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) solution for 1–4 min and transferred to root spread medium (RSM) with Timentin for two weeks. The seedlings were transplanted to sterile soil, and the seeds were harvested in the culture chamber. All medium components used for genetic transformation are shown in the table (Additional file S5: Table S3).

4.4. Detection of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines

T0 transgenic soybean plants were tested by phosphinothricin following the manufacturer’s instructions. In the early flowering period of soybean, herbicide (Liberty®, Bayer, Monheim am Rhein, Germany) was applied at the same position as the third compound leaf of the transgenic soybean at a concentration of 135 mg L-1, and the soybean leaf condition was observed three days after application. Similarly, T0 transgenic A. thaliana plants were sprayed with herbicide (Liberty®, Bayer, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for identification. In addition, for molecular identification, total DNA was extracted from the leaves of the T3 and T4 transgenic lines by 2 × Taq Plus Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The PCR was performed with 10 μM final concentrations of primers and the following program: 94 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 2 min; and 72 °C for 5 min for the final extension [76]. The specific identification primers (Additional file S2: Table S2) used in PCR amplification were designed according to the vector and the GsABCI1 sense fragment sequence.

4.5. Phenotypes of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines

To analyze the phenotype of Al stress-related genes in wild type (WT) and GsABCI1 overexpression lines, the seeds of T3 homozygous transgenic soybean lines and WT were germinated and adapted in a 0.5 μM CaCl2 hydroponic solution (pH = 5.8) for one day. The identified seedlings of soybean were transferred into a 0.5 μM CaCl2 hydroponic solution (pH 4.5) containing 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM AlCl3 for 12 h. Like the previous method, the A. thaliana seeds of T3 transgenic lines and WT were sterilized by 0.1% HgCl2 solution and grown on 1/2 mannitol salt (MS) agar plates (2% sucrose, 0.8% agar, pH 5.8) [75]. To break dormancy and ensure uniform germination, the A. thaliana seeds were initially cultured on MS medium for 2 days in the dark at 4 °C. Then, the uniform (about 1 cm) A. thaliana seedlings were moved to 1/2 MS agar plates (2% sucrose, 0.8% agar, pH 4.5) with 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, or 150 μM AlCl3 for two days [76].

In the phenotypic experiment, plants were grown in the greenhouse under the following conditions: 21–23 °C, 60% relative humidity, 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity, and 16 h light/8 h dark cycles. The seedlings were photographed and labeled in sequence before and after Al3+ treatment, and then the length of the main root was analyzed using ImageJ. Al3+ sensitivity was evaluated by relative root elongation expressed as (root elongation with Al3+ treatment/root elongation without Al) × 100% [78].

In addition, the soybean root systems of treated plants were scanned by an Epson Expression 10000 XL scanner (Epson, Japan) to determine the relative total area, relative total root length, and relative total volume to assist in the evaluation of Al3+ tolerance [79]. All experiments were repeated at least three times with 16 biological replicates.

4.6. Bioinformatics Analysis of GsABCI1

Vector NTI was used for the amino acid sequence alignments of GsABCI1 with the ABC transport system permease protein (ABC.X2.P) genes in O. sativa (OsSTAR2, Os05g02750), A. thaliana (ALS3, At2G37330), G. max (GmABCI13, Gm10g047100), P. vulgaris (Phvul001g172900), and V. unguiculata (Vigun01g155100). The phylogenetic tree analysis using MEGA-X was based on the JTT model and was enhanced by iTOLs (https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 6 June 2021)). Peptide sequence information was obtained from Phytozome (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html (accessed on 6 June 2021)). The transmembrane domain prediction was performed by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (accessed on 6 June 2021)). The protein model is predicted by Protein Homology/nalogy Recognition Engine v2.0 (Phyre2, http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/ (accessed on 6 June 2021)).

4.7. Subcellular Localization of GsABCI1

To analyze the subcellular localization of GsABCI1 protein, the GsABCI1 (lacking a termination codon) gene was inserted at the 5′-terminus of the GFP gene in the pCMBIA1302-GFP vector under the control of the 35S promoter to express a GsABCI1-GFP fusion protein in N. benthamiana cells. The recombinant vector pCMBIA1302-GsABCI1 was then transformed into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 by the freeze-thaw method and confirmed by molecular identification. The coding region of GsABCI1 was amplified using gene-specific primers (Additional file S2: Table S2; the NcoI and Spel sites are underlined). The transient expression of the GsABCI1-GFP fusion protein was observed using a Lecia TCS SP8 STED 3× confocal laser scanning microscope (Lecia, Solms, Germany) [80].

4.8. Expression Pattern of GsABCI1

In the experiment, to investigate the expression pattern of GsABCI1 in wild soybeans (G. soja), the plants were subjected to the following treatments: to determine time-dependent expression, plants were treated with a solution containing 50 μM AlCl3 for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h; to determine dose-dependent expression, plants were exposed to a solution containing 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, or 100 μM AlCl3 for 8 h; to determine tissue-specific expression, seedling plants were cultivated in a solution with 0 or 50 μM AlCl3 for 12 h; and to determine expression in response to metals and different pH values, seedling plants were grown under different pH conditions or in solutions (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3, 23 μM CdCl3, 10 μM LaCl3, or 0.5 μM CuCl2.

To investigate the expression pattern of GsABCI1, total RNA was extracted using TRNzol Reagent (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), and the conversion to cDNA was performed by HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. The cDNA quality was assessed by PCR using specific primers for ACTIN3 to exclude genomic DNA contamination. The primers for qRT-PCR were designed using Primer Premier 6.0 software. qRT-PCR was performed in the 96-well (20 μL) format using the ChamQ™ Universal SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) for Real-Time PCR on a CFX96™ Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), which included three technical replicates. ACTIN3 was used as an internal control. The expression levels of all candidate genes were determined by using the 2−ΔΔct method [70,79]. All primers used in qRT-PCR are shown in Additional file S2: Table S2.

4.9. Analysis of Al Accumulation Patterns

To analyze Al accumulation patterns, 5-day-old WT and transgenic soybean seedlings were exposed to a CaCl2 hydroponics solution (pH 4.5) with 25 μM AlCl3 for 24 h. Subsequently, to evaluate the amount of surface-bound Al, the roots (0–2 cm) were stained with hematoxylin for 30 min, washed three times with ddH2O, and observed using a physical microscope (Leica Microsystems, Leica, Germany) [81]. To quantify the Al status of roots, the seedlings were exposed to a CaCl2 hydroponics solution (pH 4.5) with 0, 10, 25, or 50 μM AlCl3 for 24 h. Then, the roots (0–6 cm, 10 roots, three replicates) were digested, and the Al3+ was extracted by 2N HCl for 24 h with occasional shaking. The Al3+ concentration in the extracts was determined by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ELEMENT™ Series ICP-MS optical emission spectrometer, Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA) [38].

4.10. Root Component Analysis of GsABCI1 Transgenic Lines

We selected the soybean roots (0–2 cm) treated with 0, 50 μM AlCl3 in Section 4.9 for root component analysis. The DNS colorimetric method was used for hemicellulose measurement. In short, hemicellulose is converted into reducing sugar after acid treatment, which reacts with DNS to generate a red-brown substance. The product has a characteristic absorption peak at 540 nm, and the content of hemicellulose can be quantitatively detected by changing the absorbance value [37]. Pectin aldose was measured by the carbazole colorimetric method. The basic principles were as follows: protopectin was hydrolyzed into soluble pectin in dilute acid solution, and further converted into galacturonic acid; galacturonic acid condensed with carbazole in a strong acid environment to generate a purplish red compound; the product had a characteristic absorption peak at 530 nm; the content of protopectin could be calculated by the change of the absorption value [82].

5. Conclusions

In summary, a half-size ABC transporter gene, GsABCI1, was isolated and its aluminum-induced expression pattern was described in this study. These results showed that GsABCI1 was responsive to aluminum stress and might enhance aluminum tolerance through aluminum transport or indirectly changing root components. Those results will provide some information for understanding the gene function of the ABC family and soybean germplasm development.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Tianfu Han from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for kindly gifting us with the pTF101.1 binary vector for generation of GsABCI1 transgenic lines. Finally, Ke Wen is very grateful to Xiaoyu Zhang for her silent care and support. Will you marry me?

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms222413264/s1.

Author Contributions

K.W., H.P. and H.N. designed the study. H.P. was responsible to gene cloning, vector construction, genetic transformation, and detection of transgenic lines. K.W. completed gene sequencing, molecular identification of transgenic plants, analysis of resistance to Al toxicity growth phenotype, analysis of aluminum accumulation patterns, analysis of expression pattern, subcellular localization, and analysis of genetic bioinformatics. R.H., X.L. and Q.M. replicated and prepared all the plants used for the study experiments. K.W. and H.N. have written manuscripts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971966, 31771816, 31971965), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B020220008), the New Varieties Cultivation of Genetically Modified Organisms (2016ZX08004002-007), the China Agricultural Research System (CARS-04-PS09), the Projects of Science and Technology of Guangzhou (201804020015), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0101505), the project of the Key Laboratory of Plant Molecular Breeding of Guangdong Province (GPKLPMB201905).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Xia J., Yamaji N., Kasai T., Ma J.F. Plasma membrane-localized transporter for aluminum in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18381–18385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Uexküll H.R., Mutert E. Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant Soil. 1995;171:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00009558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochian L.V., Hoekenga O.A., Piñeros M.A. How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:459–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eticha D., Zahn M., Bremer M., Yang Z., Rangel A.F., Rao I.M., Horst W.J. Transcriptomic analysis reveals differential gene expression in response to aluminium in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) genotypes. Ann. Bot. 2010;105:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barceló J., Charlotte P. Fast root growth responses, root exudates, and internal detoxification as clues to the mechanisms of aluminium toxicity and resistance: A review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2002;48:75–92. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kochian L.V. Cellular mechanisms of aluminum toxicity and resistance in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;46:237–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.46.060195.001321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma J.F., Ryan P.R., Delhaize E. Aluminium tolerance in plants and the complexing role of organic acids. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:273–278. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinraide T.B. Identity of the rhizotoxic aluminum species. Plant Soil. 1991;134:167–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00010729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kollmeier M., Felle H.H., Horst W.J. Genotypical Differences in Aluminum Resistance of Maize Are Expressed in the Distal Part of the Transition Zone. Is Reduced Basipetal Auxin Flow Involved in Inhibition of Root Elongation by Aluminum? Plant Physiol. 2000;122:945–956. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivaguru M., Balusška F., Volkmann D., Felle H.H., Horst W.J. Impacts of Aluminum on the Cytoskeleton of the Maize Root Apex. Short-Term Effects on the Distal Part of the Transition Zone1. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:1073–1082. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J.F., Hiradate S. Form of aluminium for uptake and translocation in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) Planta. 2000;211:355–360. doi: 10.1007/s004250000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J.F., Taketa S., Yang Z.M. Aluminum Tolerance Genes on the Short Arm of Chromosome 3R Are Linked to Organic Acid Release in Triticale. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:687–694. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sade H., Meriga B., Surapu V., Gadi J., Sunita M.S.L., Suravajhala P., Kishor P.B.K. Toxicity and tolerance of aluminum in plants: Tailoring plants to suit to acid soils. BioMetals. 2016;29:187–210. doi: 10.1007/s10534-016-9910-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magalhaes J.V., Liu J., Guimarães C.T., Lana U.G.P., Alves V.M.C., Wang Y.-H., E Schaffert R., A Hoekenga O., Pineros M., E Shaff J., et al. A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1156–1161. doi: 10.1038/ng2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horst W.J., Schmohl N., Kollmeier M., Ka F.E.B., Sivaguru M. Does aluminium affect root growth of maize through interaction with the cell wall—Plasma membrane—Cytoskeleton continuum? Plant Soil. 1999;215:163–174. doi: 10.1023/A:1004439725283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X.F., Ma J.F., Matsumoto H. Pattern of Aluminum-Induced Secretion of Organic Acids Differs between Rye and Wheat. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1537–1544. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J.L., Zhu X.F., Peng Y.X., Zheng C., Li G.X., Liu Y., Shi Y.Z., Zheng S.J. Cell Wall Hemicellulose Contributes Significantly to Aluminum Adsorption and Root Growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1885–1892. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.172221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda K., Kariuda M., Itoi H. Blueing of sepal colour of Hydrangea macrophylla. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2251–2254. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83019-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma J.F., Hiradate S., Nomoto K., Iwashita T., Matsumoto H. Internal Detoxification Mechanism of Al in Hydrangea (Identification of Al Form in the Leaves) Plant Physiol. 1997;113:1033–1039. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng S.J., Ma J.F., Matsumoto H. High aluminum resistance in buckwheat.I. Al-induced specific secretion of oxalic acid from root tips. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:745–751. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simões C.C., Melo J.O., Magalhaes J.V., Guimarães C.T. Genetic and molecularmechanisms of aluminum tolerance in plants. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012;11:1949–1957. doi: 10.4238/2012.July.19.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen R., Ma J., Kyo M., Iwashita T. Compartmentation of aluminium in leaves of an Al-accumulator, Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. Planta. 2002;215:394–398. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0763-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locher K.P. Mechanistic diversity in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:487–493. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen V.N.T., Moon S., Jung K.-H. Genome-wide expression analysis of rice ABC transporter family across spatio-temporal samples and in response to abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:1276–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra A.K., Choi J., Rabbee M.F., Baek K.H. In Silico Genome-Wide Analysis of the ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Gene Family in Soybean (Glycine max L.) and Their Expression Profiling. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019:8150523. doi: 10.1155/2019/8150523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia O., Bouige P., Forestier C., Dassa E. Inventory and Comparative Analysis of Rice and Arabidopsis ATP-binding Cassette (ABC) Systems. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:249–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arana M.R., Altenberg G.A., Altenberg M.R.A.A.G. ATP-binding Cassette Exporters: Structure and Mechanism with a Focus on P-glycoprotein and MRP1. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019;26:1062–1078. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666171012105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verrier P.J., Bird D., Burla B., Dassa E., Forestier C., Geisler M., Klein M., Kolukisaoglu U., Lee Y., Martinoia E., et al. Plant ABC proteins--a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watts G.F. An ABC of HDL: A paradigm shift in managing lipid disorders. Mod. Med. 2004;29:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong J., Pineros M., Li X., Yang H., Liu Y., Murphy A.S., Kochian L.V., Liu D. An Arabidopsis ABC Transporter Mediates Phosphate Deficiency-Induced Remodeling of Root Architecture by Modulating Iron Homeostasis in Roots. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:244–259. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rea P.A. Plant ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007;58:347–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z.C., Yamaji N., Motoyama R., Nagamura Y., Ma J.F. Up-Regulation of a Magnesium Transporter Gene OsMGT1 Is Required for Conferring Aluminum Tolerance in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1624–1633. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.199778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang C.-F., Yamaji N., Mitani N., Yano M., Nagamura Y., Ma J.F. A Bacterial-Type ABC Transporter Is Involved in Aluminum Tolerance in Rice. Plant Cell. 2009;21:655–667. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tahara K., Nishiguchi M., Frolov A., Mittasch J., Milkowski C. Identification of UDP glucosyltransferases from the aluminum-resistant tree Eucalyptus camaldulensis forming β-glucogallin, the precursor of hydrolyzable tannins. Phytochemistry. 2018;152:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roselló M., Poschenrieder C., Gunse B., Barceló J., Llugany M. Differential activation of genes related to aluminium tolerance in two contrasting rice cultivars. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015;152:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Che J., Yamaji N., Yokosho K., Shen R.F., Ma J.F. Two Genes Encoding a Bacterial-Type ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter are Implicated in Aluminum Tolerance in Buckwheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:2502–2511. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao J., Liang Y., Li J., Wang S., Zhan M., Zheng M., Li H., Yang Z. Identification of a bacterial-type ATP-binding cassette transporter implicated in aluminum tolerance in sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) Plant Signal. Behav. 2021;16:1916211. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2021.1916211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsen P.B., Geisler M., Jones C.A., Williams K.M., Cancel J.D. ALS3 encodes a phloem-localized ABC transporter-like protein that is required for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005;41:353–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyna-Llorens I., Corrales I., Poschenrieder C., Barcelo J., Cruz-Ortega R. Both aluminum and ABA induce the expression of an ABC-like transporter gene (FeALS3) in the Al-tolerant species Fagopyrum esculentum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015;111:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agrahari R.K., Kobayashi Y., Borgohain P. Aluminum-Specific Upregulation of GmALS3 in the Shoots of Soybeans: A Potential Biomarker for Managing Soybean Production in Acidic Soil Regions. Agronomy. 2020;10:1228. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10091228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W., Feng X., Cao F., Wu D., Zhang G., Vincze E., Wang Y., Chen Z.-H., Wu F. An ATP binding cassette transporter HvABCB25 confers aluminum detoxification in wild barley. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;401:123371. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niu L., Li H., Song Z., Dong B., Cao H., Liu T., Du T., Yang W., Amin R., Wang L., et al. The functional analysis of ABCG transporters in the adaptation of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) to abiotic stresses. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10688. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lei G.J., Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Fujii-Kashino M., Ma J.F. Functional characterization of two half-size ABC transporter genes in aluminium-accumulating buckwheat. New Phytol. 2017;215:1080–1089. doi: 10.1111/nph.14648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang C.-F., Yamaji N., Chen Z., Ma J.F. A tonoplast-localized half-size ABC transporter is required for internal detoxification of aluminum in rice. Plant J. 2012;69:857–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y., Du H., Li P., Shen Y., Peng H., Liu S., Zhou G.-A., Zhang H., Liu Z., Shi M., et al. Pan-Genome of Wild and Cultivated Soybeans. Cell. 2020;182:162–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao Y., You Q., Duan G., Ren J., Chu S., Zhao J., Li X., Zhou X., Jiao Y. Quantitative trait loci analysis of seed oil content and composition of wild and cultivated soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J., Magalhaes J.V., Shaff J., Kochian L.V. Aluminum-activated citrate and malate transporters from the MATE and ALMT families function independently to confer Arabidopsis aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 2009;57:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma J.F. Syndrome of Aluminum Toxicity and Diversity of Aluminum Resistance in Higher Plants. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2007;264:225–252. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)64005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma J.F. Role of Organic Acids in Detoxification of Aluminum in Higher Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:383–390. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoekenga O.A., Maron L.G., Piñeros M.A., Cançado G.M.A., Shaff J., Kobayashi Y., Ryan P.R., Dong B., Delhaize E., Sasaki T., et al. AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9738–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602868103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sasaki T., Yamamoto Y., Ezaki B., Katsuhara M., Ahn S.J., Ryan P.R., Delhaize E., Matsumoto H. A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 2004;37:645–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang C., Pineros M., Tian J., Yao Z., Sun L., Liu J., Shaff J., Coluccio A., Kochian L., Liao H. Low pH, Aluminum, and Phosphorus Coordinately Regulate Malate Exudation through GmALMT1 to Improve Soybean Adaptation to Acid Soils. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1347–1361. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lou H.Q., Fan W., Xu J.M., Gong Y.L., Jin J.F., Chen W.W., Liu L.Y., Hai M.R., Yang J.L., Zheng S.J. An Oxalyl-CoA Synthetase Is Involved in Oxalate Degradation and Aluminum Tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:1679–1690. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Oliveira A.L., Martins-Lopes P., Tolrá R., Poschenrieder C., Tarquis M., Guedes-Pinto H., Benito C. Molecular characterization of the citrate transporter gene TaMATE1 and expression analysis of upstream genes involved in organic acid transport under Al stress in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) Physiol. Plant. 2014;152:441–452. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Fujii-Kashino M., Ma J.F. Functional analysis of a MATE gene OsFRDL2 revealed its involvement in Al-induced secretion of citrate, but a lower contribution to Al tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:976–985. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng W., Luo K., Li D., Zheng X., Wei X., Smith W., Thammina C., Lu L., Li Y., Pei Y. Overexpression of an Arabidopsis magnesium transport gene, AtMGT1, in Nicotiana benthamiana confers Al tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:4235–4243. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen A., Chen X., Wang H. Genome-wide investigation and expression analysis suggest diverse roles and genetic redundancy of Pht1 family genes in response to Pi deficiency in tomato. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iuchi S., Koyama H., Iuchi A., Kobayashi Y., Kitabayashi S., Ikka T., Hirayama T., Shinozaki K., Kobayashi M., Kobayashi Y., et al. Zinc finger protein STOP1 is critical for proton tolerance in Arabidopsis and coregulates a key gene in aluminum tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9900–9905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang J., Park J., Choi H., Burla B., Kretzschmar T., Lee Y., Martinoia E. Plant ABC Transporters. Arab. Book. 2011;9:e0153. doi: 10.1199/tab.0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larsen P.B., Cancel J., Rounds M., Ochoa V. Arabidopsis ALS1 encodes a root tip and stele localized half type ABC transporter required for root growth in an aluminum toxic environment. Planta. 2007;225:1447–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li C.X., Yan J.Y., Ren J.Y., Sun L., Xu C., Li G.X., Ding Z.J., Zheng S.J. A WRKY transcription factor confers aluminum tolerance via regulation of cell wall modifying genes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019;62:1176–1192. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang C.-F., Yamaji N., Ma J.F. Knockout of a Bacterial-Type ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Gene, AtSTAR1, Results in Increased Aluminum Sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1669–1677. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaskowiak J., Kwasniewska J., Milewska-Hendel A., Kurczynska E.U., Szurman-Zubrzycka M., Szarejko I. Aluminum Alters the Histology and Pectin Cell Wall Composition of Barley Roots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3039. doi: 10.3390/ijms20123039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sujkowska-Rybkowska M., Borucki W. Pectins esterification in the apoplast of aluminum-treated pea root nodules. J. Plant Physiol. 2015;184:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang J.L., Li Y.Y., Zhang Y.J., Zhang S.S., Wu Y.R., Wu P., Zheng S.J. Cell Wall Polysaccharides Are Specifically Involved in the Exclusion of Aluminum from the Rice Root Apex. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:602–611. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guillon F., Moïse A., Quemener B., Bouchet B., Devaux M.-F., Alvarado C., Lahaye M. Remodeling of pectin and hemicelluloses in tomato pericarp during fruit growth. Plant Sci. 2017;257:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Exley C., Burgess E., Day J.P., Jeffery E.H., Melethil S., Yokel R.A. Aluminum toxicokinetics. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1996;48:569–584. doi: 10.1080/009841096161078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeng Q.-Y., Yang C.-Y., Ma Q.-B., Li X.-P., Dong W.-W., Nian H. Identification of wild soybean miRNAs and their target genes responsive to aluminum stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoagland D.R., Arnon D.I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Circ. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1950;347:32. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu J., Suo H., Yi R., Ma Q., Nian H. Glyma11g13220, a homolog of the vernalization pathway gene VERNALIZATION 1 from soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], promotes flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:232. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0602-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frame B.R., Shou H., Chikwamba R.K., Zhang Z., Xiang C., Fonger T.M., Pegg S.E.K., Li B., Nettleton D.S., Pei D., et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation of Maize Embryos Using a Standard Binary Vector System. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:13–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.000653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.E Hood E., Helmer G.L., Fraley R.T., Chilton M.D. The hypervirulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens A281 is encoded in a region of pTiBo542 outside of T-DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1986;168:1291–1301. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1291-1301.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suo H., Ma Q., Ye K., Yang C., Tang Y., Hao J., Zhang Z.J., Chen M., Feng Y.-Q., Nian H. Overexpression of AtDREB1A Causes a Severe Dwarf Phenotype by Decreasing Endogenous Gibberellin Levels in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murashige T., Skoog F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ma Q., Yi R., Li L., Liang Z., Zeng T., Zhang Y., Huang H., Zhang X., Yin X., Cai Z., et al. GsMATE encoding a multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporter enhances aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1397-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zia M., Rizvi Z.F., And R. Agrobacterium mediated transformation of soybean (Glycine Max L.): Some conditions standardization. Pak. J. Bot. 2010;42:2269–2279. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nezames C.D., Ochoa V., Larsen P.B. Mutational loss of Arabidopsis SLOW WALKER2 results in reduced endogenous spermine concomitant with increased aluminum sensitivity. Funct. Plant Biol. 2013;40:67–78. doi: 10.1071/FP12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cai Z., Cheng Y., Xian P., Ma Q., Wen K., Xia Q., Zhang G., Nian H. Acid phosphatase gene GmHAD1 linked to low phosphorus tolerance in soybean, through fine mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018;131:1715–1728. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma Q., Xia Z., Cai Z., Li L., Cheng Y., Liu J., Nian H. GmWRKY16 Enhances Drought and Salt Tolerance Through an ABA-Mediated Pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana . Front. Plant Sci. 2019;9:1979. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Delhaize E., Craig S., Beaton C.D., Bennet R.J., Jagadish V.C., Randall P.J. Aluminum Tolerance in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (I. Uptake and Distribution of Aluminum in Root Apices) Plant Physiol. 1993;103:685–693. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Konishi T., Kotake T., Tsumuraya Y. Chain elongation of pectic beta-(1-->4)-galactan by a partially purified galactosyltransferase from soybean (Glycine max Merr.) hypocotyls. Planta. 2007;226:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.