Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the status of and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination of healthcare workers in two major hospital systems (academic and private) in Southern California. Responses were collected via an anonymous and voluntary survey from a total of 2491 participants, including nurses, physicians, other allied health professionals, and administrators. Among the 2491 participants that had been offered the vaccine at the time of the study, 2103 (84%) were vaccinated. The bulk of the participants were middle-aged college-educated White (73%), non-Hispanic women (77%), and nursing was the most represented medical occupation (35%). Political affiliation, education level, and income were shown to be significant factors associated with vaccination status. Our data suggest that the current allocation of healthcare workers into dichotomous groups such as “anti-vaccine vs. pro-vaccine” may be inadequate in accurately tailoring vaccine uptake interventions. We found that healthcare workers that have yet to receive the COVID-19 vaccine likely belong to one of four categories: the misinformed, the undecided, the uninformed, or the unconcerned. This diversity in vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers highlights the importance of targeted intervention to increase vaccine confidence. Regardless of governmental vaccine mandates, addressing the root causes contributing to vaccine hesitancy continues to be of utmost importance.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine hesitancy, vaccine acceptance, healthcare professionals

1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in late 2019 and reached a global pandemic level by March 2020 [1]. By October 2021, 244 million known infections were recorded worldwide, with 45 million cases in the United States (U.S.) resulting in over 736,000 deaths [2]. Unprecedented global research efforts produced effective COVID-19 vaccines in record time, with the first doses becoming available in December 2020 [3]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) were the first group in the U.S. to be offered COVID-19 vaccinations. However, several months into the vaccination effort, many remain hesitant and unvaccinated despite increasingly stringent vaccination policies.

Vaccine hesitancy, the leading threat to global health [4], is the refusal of vaccination despite availability and accessibility. HCW vaccine hesitancy can be rooted in many factors including fears about safety and efficacy [5,6], preference for physiological herd immunity (i.e., natural inoculation) [7], distrust in government [8,9], maintaining a sense of personal freedom [6,10], sociodemographic characteristics, and broader external or organizational factors [11]. A recent scoping review of 35 studies published after vaccine authorizations found a hesitancy rate of 22.5% among 76,471 HCWs [12]. Hesitancy rates among HCWs are occupation and context dependent. For instance, 96% of the practicing physicians in that study had been fully vaccinated [13]. In contrast, only about a third (37.5%) of HCWs in skilled nursing facilities had been vaccinated, compared to three-fourths (77.8%) of nursing home residents [14]. In another study, data collected from 2500 U.S. hospitals show regional differences in HCWs vaccination rates—from a high of 99% at Houston Methodist Hospital, the first hospital to introduce vaccination mandates, to a low of between 30% and 40% at Florida hospitals [15]. No identified studies have been conducted in the Southern California region.

Experts suggest that given our global connectivity, addressing the threat of COVID-19 is highly dependent on increasing vaccination rates everywhere to reach herd immunity levels [16]. HCWs are a critical partner in moving vaccine-hesitant populations toward vaccination. HCWs are more trusted and viewed more positively than elected officials or government agencies [17]. Therefore, addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs is a complex but important task in reaching herd immunity. As hesitancy is not uniform, vaccine uptake and preference analyses will allow us to detect HCW subgroups with low vaccination acceptance. Identifying the determinants of vaccine hesitancy among these subgroups and then tailoring the vaccination campaign to fit each sub-group’s concern is essential to addressing vaccine hesitancy.

In the present study, we sought to determine what proportions of HCWs in Southern California were accepting of, hesitant about, or resistant to a COVID-19 vaccine. Additionally, we sought to profile HCWs who are hesitant about or resistant to a COVID-19 vaccine by identifying key sociodemographic, occupational, political factors and specific beliefs that distinguish them from those who accept a COVID-19 vaccine. While this cross-sectional exploratory study had no explicit hypotheses, our approach was guided by several assumptions: (1) most HCWs would accept vaccination, (2) HCWs job characteristics including direct patient interaction would facilitate vaccine acceptance, (3) sociodemographic characteristics of HCWs such as gender, race, age, and educational attainment will be associated with intention to take vaccine, (4) vaccine hesitancy among HCWs will be influenced by several factors, including insufficient knowledge about the vaccines, misinformation from social media, political affiliation, and previous COVID-19 infection. Understanding the characteristics that predict vaccine hesitancy among HCW subgroups will enable health administrators to apply and evaluate tailored interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an online, cross-sectional survey of HCWs at two large hospital systems (academic and private) in Southern California. The study protocol was reviewed by the respective IRBs of each participating institution and deemed exempt. Both hospitals started vaccinating their HCWs against COVID-19 on 17 December 2020.

2.1. Sample and Recruitment Strategy

Recruitment occurred relatively early after vaccination distribution; between 5 and 26 February 2021 at the academic hospital, and 3 and 17 April 2021 at the private hospital. We distributed the online Qualtrics survey via institution-wide email listservs, with 8848 recipients at the academic hospital and 3062 recipients at the private hospital. Listserv recipients included physicians, nurses, advanced practice providers, pharmacists, other allied health professionals, administrators, and nonclinical ancillary staff. All employees of both hospital systems were invited to participate in the study. The initial invitation email to complete the survey was followed by two email reminders to encourage participation. The survey was anonymous and voluntary.

2.2. Data Collection Process

A working group developed a survey to understand HCWs’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the COVID-19 vaccination. The survey was based on previous questionnaires conducted in the context of the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic. It was pilot-tested with 7 healthcare professionals and revised to ensure readability and understandability. The final survey included exclusively forced-choice questions to avoid missing data. The overall survey response rate was 20.9% (2491 respondents/11,910 total possible recipients) with a dropout rate of 17%. This modest response rate can be attributed to the spike in COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations in Southern California, coinciding with the dates when the study survey was administered. The increased workload and burnout among HCWs presented a barrier to survey completion.

2.3. Measures

The survey instrument was composed of five parts: (1) Demographics: including age, gender, race, ethnicity, education level, self-reported history of chronic illness, income level, household size, and political party affiliation; (2) Clinical characteristics: including position within the healthcare field, clinical work setting, medical specialty, frequency of contact with COVID-19 patients, and self-reported history of flu vaccination; (3) COVID-19-related misinformation: including belief in a synthetic origin of the virus, belief in COVID-19 being a hoax, and belief that COVID-19’s impact on the healthcare system is exaggerated; (4) COVID-19 knowledge: understanding that COVID-19 is more deadly and contagious than seasonal flu, estimated COVID-19 mortality for self and an average American, understanding of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness; (5) COVID-19’s impact: COVID-19’s financial impact and whether someone close had a severe illness or died due to COVID-19. We derived the primary outcome, COVID-19 vaccine behavior/hesitancy, from two questions—(a) receipt of any dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and (b) in case of a negative answer, intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine within the next six months. We considered answers “unsure”, “probably not”, and “definitely not” indicative of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The 37-item survey took, on average, 15 min to complete.

2.4. Analysis

All data were exported into SPSS 26.0 for analysis. Data were first reviewed at a univariate and descriptive statistics level, and the ability of the data to conform to the assumptions of the planned analysis [18]. Analyses included a review of the vaccination rates and presentation of the descriptive statistics. We then performed multinomial logistic regression. This method is similar to logistic regression but allows for an outcome variable with 3 or more levels since our outcome variable had three categories (vaccinated, not vaccinated, and hesitant). The data supported assumptions for multinomial logistic regression. The outcome variable was structured to have three categories: (1) Vaccinated (2) Not vaccinated, and (3) Hesitant to be vaccinated. Independent variables were fit to the multinomial logistic regression model in hierarchical order with demographic variables added first, followed by participant’s occupation and clinical area of employment. Next, we entered COVID-19 and vaccine-related variables, sources of news, political party affiliation, and frequency of patient contact. The independent variables were fit as covariates. Categorical or nominal variables were dummy coded prior to estimation.

Realizing that there is a continuum between total acceptance and complete refusal of vaccinations, we conducted clustering analysis to further describe groups of currently unvaccinated HCWs holding varying degrees of indecision about vaccination. We used the kernel k-means method (Kernlab R package) and the kernel function of the radial basis (Gaussian kernel) to perform a cluster analysis. This method, representing a more generalized k-means approach to cluster analysis, is well-suited for linear and nonlinear separable inputs because the data type is usually unknown. Kernel k-means cannot determine the number of clusters. Therefore, we used the variance ratio criterion (VRC) to determine the number of clusters. VRC was selected due to its excellent performance against other internal criteria to determine the number of clusters [19]. The literature suggests that VRC is the most effective criterion for purposes of cluster number determination [20,21]. We set the number of clusters to four, with the highest value based on the variance ratio criterion (Table 1).

Table 1.

The number of clusters analyzed by variance ratio criterion.

| Number of Clusters | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance ratio value | 2.8167 | 4.7548 | 4.2031 | 3.8492 | 2.9618 |

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Overall, 2491 respondents answered the survey between 5 February and 17 April 2021. Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the sample. Among 2491 HCW respondents, 35% were nurses, 19% were physicians, and 7% were administrators. Respiratory therapists, advanced practice providers, and pharmacists each represented about 3% of the sample. The remaining 29% were other allied health professionals. The majority of participants were White (73%), non-Hispanic (77%), women (75%), born after 1965 (75%), and college-educated or higher (74%). The most reported political affiliation was Democrat/leaned Democrat (46%), while 30% were Republican/leaned Republican, and 24% reported no lean to either political party.

The HCWs participating in the survey were significantly impacted by the pandemic. Sixty-one percent reported having at least intermittent contact with COVID-19 patients, with 28% having frequent contact. Thirteen percent reported being diagnosed with COVID-19, and 42% said that someone close to them had suffered severe disability or died from COVID-19. Forty-seven percent of participants stated that the pandemic had negatively affected them financially.

There was diversity in beliefs about the virus and the vaccine. Twenty-three percent considered seasonal influenza as more contagious than COVID-19, 32.6% overestimated the mortality associated with COVID-19, while 11.5% underestimated its severity. A sizeable fraction of the sample held conspiratorial beliefs about COVID-19, with 38% of the sample believing the virus is or could be manmade, 15% suggesting the impact of COVID-19 is overblown, and 6% not rejecting the notion that the pandemic is a hoax. A large majority (80.2%) identified vaccine efficacy to be 90% or greater.

COVID-19 vaccination rate at the time of survey administration was high, with 2103 (84.4%) reporting having received it. Vaccine uptake was highest among physicians (96.2%) and lowest among respiratory therapists (70.3%), while 78.6% of nurses were vaccinated. Among the 391 unvaccinated HCWs at the time of the survey, 87 (3.5%) were willing to receive the vaccine, leaving 304 HCW (12.2%) whom we classified as vaccine hesitant. Additional sample characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 618 (24.81) |

| Female | 1.867 (74.95) |

| Other/non-binary | 6 (0.24) |

| Age | |

| 1946–1964 | 615 (24.94) |

| 1965–1980 | 800 (32.44) |

| 1981–1996 | 998 (40.47) |

| After 1996 | 53 (2.15) |

| Race | |

| White | 1.815 (72.86) |

| Black or African American | 123 (4.94) |

| Asian American | 438 (17.58) |

| Pacific Islander | 47 (1.89) |

| Native American | 68 (2.73) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 570 (22.88) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 1.921 (77.12) |

| Education | |

| Some college | 326 (13.09) |

| Associate degree | 319 (12.18) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 823 (33.05) |

| Graduate degree | 397 (15.94) |

| Doctoral degree | 525 (25.10) |

| Household income level | |

| Less than USD 50,000 | 124 (4.98) |

| USD 50,000–100,000 | 526 (21.12) |

| USD 101,000–150,000 | 624 (25.05) |

| USD 150,000–200,000 | 405 (16.26) |

| USD 201,000–250,000 | 261 (10.48) |

| Greater than USD 250,000 | 365 (14.65) |

| Decline to respond | 186 (7.47) |

| Political Affiliation | |

| Democrat/lean Democrat | 1.158 (46.49) |

| Republican/lean Republican | 743 (29.83) |

| No lean | 590 (23.69) |

| Occupation | |

| Physician | 473 (18.99) |

| Attending | 348 (13.97) |

| Resident | 108 (4.34) |

| Fellow | 17 (0.68) |

| Nurse | 869 (34.89) |

| Nurse practitioner/Physician Assistant | 83 (3.33) |

| Pharmacist | 61 (2.45) |

| Respiratory Therapist | 91 (3.65) |

| Administrator | 176 (7.07) |

| Patient care assistant | 738 (29.63) |

| Clinical area | |

| ICU | 604 (24.25) |

| Non-ICU | 853 (34.24) |

| Emergency Department | 177 (7.11) |

| Outpatient | 808 (32.44) |

| Clinical Specialty | |

| Critical care | 187 (7.51) |

| Adult | 104 (4.18) |

| Pediatric | 83 (3.33) |

| General Medicine | 486 (19.51) |

| Adult | 375 (15.05) |

| Pediatric | 111 (4.46) |

| Subspecialty | 975 (39.14) |

| Adult | 744 (29.87) |

| Pediatric | 231 (9.27) |

| Surgery | 310 (12.44) |

| Emergency | 163 (6.54) |

| Not medical | 370 (14.85) |

| Contact with COVID-19 patients | |

| Frequent * | 698 (28.02) |

| Intermittent ** | 838 (33.64) |

| No contact | 955 (38.34) |

| Recent flu vaccination | |

| Yes | 2.285 (91.73) |

| No | 206 (8.27) |

* direct care once a week/contact with many during one shift, ** direct care less than once a week/consult on the cases.

3.2. Predictors of Vaccination Intentions

We used a Chi-square test to determine the likelihood of vaccination for all participants. The model’s overall fit was excellent (Likelihood Ratio Chi-sq = 975.8, df = 96, p < 0.001) and achieved an overall correct classification rate of 88.6%. The Cox and Snell R2 was moderate at 0.33. This reflects the overall characteristics of the model in that the model was strong in predicting whether a participant was vaccinated (correct classification = 97.9%) but had a lower success rate at predicting the not vaccinated group (correct classification = 43.3%) and was fairly weak in predicting the hesitant group (correct classification = 26.6%). Thus, our model effectively predicted the likelihood of a participant being vaccinated. Table 3 presents the univariate distribution of data across the three outcome groups (vaccinated, not vaccinated, and hesitant).

Table 3.

Univariate distribution of data across three outcome groups.

| Vaccinated | Hesitant | Not Vaccinated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % | SE | Mean or % | SE | Mean or % | SE | |

| Male | 91.10% | 6.10% | 2.80% | |||

| Latinx | 83.20% | 11.40% | 5.40% | |||

| Black | 74.80% | 17.90% | 7.30% | |||

| Asian | 93.20% | 5.70% | 1.10% | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <25 years | 77.40% | 20.80% | 1.90% | |||

| 25–40 years | 81.90% | 11.90% | 6.20% | |||

| 41–55 years | 87.00% | 8.90% | 4.20% | |||

| 56–75 years | 91.50% | 4.60% | 3.90% | |||

| Education Level | ||||||

| Some College | 85.30% | 8.60% | 6.10% | |||

| Associate Degree | 80.60% | 12.20% | 7.20% | |||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 81.90% | 12.40% | 5.70% | |||

| Graduate Degree | 85.90% | 9.60% | 4.50% | |||

| Doctorate Degree | 94.40% | 3.70% | 1.90% | |||

| Chronic Illness | 87.80% | 8.10% | 4.10% | |||

| Household Size | 2.94 | 0.03 | 3.31 | 0.08 | 3.33 | 0.12 |

| Income | ||||||

| <USD 50,000 | 86.30% | 9.70% | 4.00% | |||

| USD 50,000–100,000 | 81.60% | 12.70% | 5.70% | |||

| USD 101,000–150,000 | 84.00% | 11.10% | 5.00% | |||

| USD 151,000–200,000 | 86.40% | 9.10% | 4.40% | |||

| USD 201,000–250,000 | 87.40% | 8.00% | 4.60% | |||

| >USD 250,000 | 93.40% | 2.50% | 4.10% | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Nurse | 80.80% | 7.60% | 3.60% | |||

| Physician | 96.60% | 2.10% | 1.30% | |||

| NP/PA | 94.00% | 3.60% | 2.40% | |||

| Administration | 93.20% | 5.70% | 1.10% | |||

| Clinical area | ||||||

| Intensive Care Unit | 82.00% | 11.80% | 6.30% | |||

| Emergency Department | 84.70% | 11.30% | 4.00% | |||

| Outpatient | 90.60% | 5.80% | 3.60% | |||

| Specialty area | ||||||

| Adult Critical Care | 80.80% | 12.50% | 6.70% | |||

| Adult Specialty Care | 86.60% | 8.60% | 4.80% | |||

| Peds Critical Care | 80.70% | 9.60% | 9.60% | |||

| Peds Specialty Care | 80.50% | 13.00% | 6.50% | |||

| COVID conspiracies | ||||||

| COVID is manmade | 4.02 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.09 | 2.65 | 0.13 |

| COVID is a hoax | 4.85 | 0.02 | 4.53 | 0.06 | 4.16 | 0.12 |

| COVID impact is exaggerated | 4.61 | 0.02 | 3.84 | 0.09 | 2.99 | 0.13 |

| COVID vs. Flu | ||||||

| Flu is more contagious | 2.69 | 0.03 | 2.90 | 0.07 | 3.00 | 0.11 |

| History of Flu vaccine | 88.90% | 7.60% | 3.50% | |||

| Recent Flu vaccine | 89.70% | 7.50% | 2.80% | |||

| COVID impact | ||||||

| Financial impact | 82.90% | 10.90% | 6.20% | |||

| Someone close had COVID | 83.00% | 10.30% | 6.70% | |||

| Someone close was hospitalized | 85.30% | 9.90% | 4.80% | |||

| Someone close died | 88.60% | 8.20% | 3.10% | |||

| Estimated COVID mortality | ||||||

| Underestimate | 71.10% | 14.60% | 14.30% | |||

| Overestimate | 89.50% | 8.00% | 2.50% | |||

| Likelihood of dying from COVID | ||||||

| High | 73.40% | 15.70% | 11.00% | |||

| Low | 93.40% | 5.10% | 1.60% | |||

| COVID vaccine knowledge | ||||||

| Underestimate efficacy | 58.10% | 25.10% | 16.80% | |||

| Prior COVID diagnosis | ||||||

| Recovered from COVID | 71.60% | 20.20% | 8.30% | |||

| Contact with COVID patients | ||||||

| Frequent | 84.10% | 10.70% | 5.20% | |||

| Intermittent | 85.60% | 9.70% | 4.77% | |||

| No contact | 87.60% | 7.75% | 4.61% | |||

| Political party affiliation | ||||||

| Democratic | 93.90% | 4.50% | 1.60% | |||

| Republican | 78.60% | 13.20% | 8.20% | |||

| Social media use | ||||||

| Well connected | 3.86 | 0.02 | 3.73 | 0.07 | 3.83 | 0.1 |

| News sources | ||||||

| Cable news | 87.90% | 8.00% | 4.10% | |||

| Mainstream news | 91.10% | 5.70% | 3.20% | |||

| Social media | 85.70% | 10.20% | 4.10% | |||

| Family or friends | 73.00% | 19.70% | 7.40% | |||

While the overall fit was strong, only certain variables offered explanatory power (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of vaccination intention.

| Not Vaccinated | Hesitant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR [95% CI] | B | p-Value | aOR [95% CI] | B | p-Value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male | 0.66 [0.32,1.37] | −0.41 | 0.240 | 0.91 [0.57,1.45] | −0.09 | 0.701 |

| Latinx | 0.58 [0.30,1.10] | −0.55 | 0.100 | 0.75 [0.49,1.12] | 0.75 | 0.194 |

| Black | 1.07 [0.42,2.71] | 0.07 | 0.740 | 1.6 [0.85,3.02] | 1.6 | 0.149 |

| Asian | 0.10 [0.03,0.31] | −2.28 | <0.001 | 0.44 [0.25,0.75] | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.55 [1.08,2.22] | 0.43 | 0.010 | 1.83 [1.42,2.36] | 1.83 | <0.001 |

| Education level | 1.02 [0.77,1.36] | 0.02 | 0.810 | 1.33 [1.11,1.59] | 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Chronic illness | 1.60 [0.89,2.85] | 0.47 | 0.120 | 1.44 [0.98,2.14] | 1.44 | 0.070 |

| Household size | 1.17 [0.95,1.44] | 0.16 | 0.100 | 1.19 [1.04,1.37] | 1.19 | 0.013 |

| Income | 1.04 [0.89,1.22] | 0.04 | 0.590 | 0.89 [0.80,0.99] | 0.89 | 0.045 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Nurse | 1.54 [0.85,2.70] | 0.43 | 0.150 | 1.03 [0.70,1.54] | 0.03 | 0.867 |

| Physician | 1.14 [0.31,4.15] | 0.13 | 0.810 | 0.29 [0.12,0.67] | −1.25 | 0.004 |

| NP/PA | 0.78 [0.12,4.82] | −0.26 | 0.730 | 0.3 [0.08,1.14] | −1.21 | 0.077 |

| Administration | 0.35 [0.07,1.81] | −1.06 | 0.170 | 0.65 [0.30,1.44] | −0.43 | 0.287 |

| Clinical area | ||||||

| Intensive Care Unit | 0.87 [0.42,1.80] | −0.14 | 0.600 | 0.92 [0.57,1.48] | −0.09 | 0.725 |

| Emergency Department | 1.11 [0.19,6.50] | 0.1 | 0.830 | 0.63 [0.20,2.04] | −0.46 | 0.442 |

| Outpatient | 0.42 [0.21,0.83] | −0.87 | 0.009 | 0.5 [0.31,0.79] | −0.70 | <0.001 |

| Specialty area | ||||||

| Adult Critical Care | 0.73 [0.21,2.50] | −0.32 | 0.610 | 0.78 [0.34,1.81] | −0.24 | 0.569 |

| Adult Specialty Care | 0.98 [0.52,1.85] | −0.02 | 0.960 | 1 [0.65,1.55] | 0.01 | 0.976 |

| Peds Critical Care | 1.21 [0.34,4.37] | 0.19 | 0.770 | 0.76 [0.29,1.98] | −0.28 | 0.570 |

| Peds Specialty Care | 0.92 [0.37,2.33] | −0.08 | 0.870 | 1.18 [0.64,2.17] | 0.17 | 0.591 |

| COVID conspiracies | ||||||

| COVID is manmade | 1.37 [1.12,1.68] | 0.32 | 0.002 | [1.19,1.55] | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| COVID is a hoax | 0.82 [0.62,1.10] | −0.19 | 0.195 | [0.68,1.10] | −0.14 | 0.235 |

| COVID impact is exaggerated | 1.66 [1.33,2.01] | 0.51 | <0.001 | [1.01,1.41] | 0.17 | 0.043 |

| COVID vs. Flu | ||||||

| Flu is more contagious | 0.68 [0.52,0.89] | −0.40 | 0.005 | 0.91 [0.76,1.08] | −0.10 | 0.261 |

| History of Flu vaccine | 0.47 [0.23,0.93] | −0.77 | 0.032 | 0.33 [0.20,0.55] | −1.12 | <0.001 |

| Recent Flu vaccine | 0.09 [0.04,0.17] | −2.47 | <0.001 | 0.29 [0.17,0.50] | −1.23 | <0.001 |

| COVID impact | ||||||

| Financial impact | 1.66 [1.00,2.76] | 0.51 | 0.05 | 1.29 [0.91,1.81] | 0.25 | 0.148 |

| Someone close had COVID | 1.83 [0.27,12.4] | 0.6 | 0.537 | 6.4 [0.74,55.01] | 1.86 | 0.09 |

| Someone close was hospitalized | 1.49 [0.21,10.6] | 0.4 | 0.691 | 5.68 [0.65,49.77] | 1.74 | 0.116 |

| Someone close died | 1.18 [0.17,8.14] | 0.17 | 0.867 | 4.74 [0.55,40.88] | 1.56 | 0.157 |

| Estimated COVID mortality | ||||||

| Underestimate | 1.10 [0.56,2.17] | 0.09 | 0.782 | 0.97 [0.56,2.17] | −0.03 | 0.915 |

| Overestimate | 1.34 [0.67,2.68] | 0.29 | 0.415 | 1.34 [0.67,2.68] | 0.29 | 0.188 |

| Likelihood of dying from COVID | ||||||

| High | 2.91 [1.57,5.37] | −1.07 | <0.001 | 2.3 [1.52,3.48] | −0.83 | <0.001 |

| Low | 0.56 [0.22,1.45] | −0.58 | 0.230 | 0.61 [0.36,1.05] | −0.49 | 0.077 |

| COVID vaccine knowledge | ||||||

| Underestimate efficacy | 13.9 [7.92,24.4] | 2.63 | <0.001 | 7.08 [4.85,10.35] | 1.96 | <0.001 |

| Prior COVID diagnosis | ||||||

| Recovered from COVID | 1.88 [1.01,3.52] | 0.63 | 0.047 | 2.58 [1.73,3.85] | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| Contact with COVID patients | ||||||

| Frequent | 1 [0.71,1.44] | 0.01 | 0.961 | 1.04 [0.82,1.33] | 0.04 | 0.735 |

| Political party affiliation | ||||||

| Democratic | 0.45 [0.22,0.95] | −0.79 | 0.035 | 0.47 [0.29,0.75] | −0.76 | 0.002 |

| Republican | 1.34 [0.72,2.47] | 0.29 | 0.354 | 1.19 [0.77,1.83] | 0.17 | 0.429 |

| Social media use | ||||||

| Well connected | 1 [0.78,1.30] | 0.01 | 0.977 | 0.85 [0.72,1.01] | −0.16 | 0.061 |

| News sources | ||||||

| Cable news | 1.39 [0.67,2.87] | 0.33 | 0.380 | 1.14 [0.69,1.89] | 0.14 | 0.598 |

| Mainstream news | 1.77 [0.76,4.13] | 0.57 | 0.184 | 1.29 [0.72,2.28] | 0.25 | 0.392 |

| Social media | 0.50 [0.19,1.31] | −0.69 | 0.159 | 0.72 [0.39,1.32] | −0.33 | 0.287 |

| Family or friends | 0.69 [0.24,1.96] | −0.38 | 0.481 | 1.09 [0.55,2.20] | 0.09 | 0.800 |

Bold—statistically significant predictors of vaccination intention.

Asian American participants were highly likely to be vaccinated, and to a lesser degree, younger HCWs. No other demographic variables added predictive value to the outcome. In the remainder of the model, the most significant predictor of COVID-19 vaccination was the individual’s approach to influenza vaccines: those with recent or previous flu vaccinations were more likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, HCWs working in an outpatient area of the health systems were more likely to be vaccinated, as were those leaning Democrat. Conversely, the most significant predictors of a participant not getting vaccinated included: inaccurate knowledge of COVID vaccine efficacy, belief that COVID-19 is a manmade virus, belief that the impact of COVID-19 is exaggerated, perceived low risk of dying if infected, having a prior diagnosis of COVID-19, and being financially impacted by COVID-19.

The comparison of “vaccinated versus hesitant” showed several differences. Overall, older, higher educated participants who lived in homes with more family members were more likely to be hesitant to receive the vaccine. Conversely, physicians and HCWs with higher income were less likely to be hesitant. Important variables that did not predict either HCW vaccination or hesitancy included gender, presence of chronic illness, specialty area of practice, source of news, frequency of contact with COVID-19 patients, and having someone close affected by COVID-19.

3.3. K-Means Cluster Analysis

To determine characteristic groupings of the unvaccinated, we conducted a K-means cluster analysis. According to the values of the variance ratio criterion, participants were separated into four clusters (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of four clusters.

| Total (n = 304) | Group 1 (n = 38) | Group 2 (n = 94) | Group 3 (n = 86) | Group 4 (n = 86) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 53 (17) | 10 (27) | 14 (15) | 16 (19) | 13 (15) |

| Female | 251 (83) | 28 (73) | 80 (85) | 70 (81) | 73 (85) |

| Age | |||||

| 1946–1964 | 50 (16) | 16 (42) | 18 (19) | 9 (10) | 7 (8) |

| 1965–1980 | 87 (29) | 10 (26) | 29 (31) | 28 (33) | 20 (23) |

| 1981–1996 | 155 (51) | 11 (29) | 46 (49) | 46 (53) | 52 (61) |

| After 1996 | 12 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 7 (8) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 242 (80) | 29 (77) | 76 (81) | 72 (84) | 65 (75) |

| African American | 27 (9) | 2 (5) | 8 (9) | 6 (7) | 11 (13) |

| Asian American | 19 (6) | 4 (10) | 5 (5) | 6 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Pacific Islander | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Native American | 12 (4) | 3 (8) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 98 (32) | 13 (34) | 44 (47) | 21 (24) | 20 (23) |

| Non-Hispanic | 206 (68) | 25 (66) | 50 (53) | 65 (76) | 66 (77) |

| Education | |||||

| Some college | 40 (13) | 3 (8) | 28 (30) | 7 (8) | 2 (2) |

| Associate degree | 56 (18) | 4 (10) | 28 (30) | 16 (19) | 9 (10) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 128 (42) | 15 (39) | 31 (33) | 46 (53) | 36 (42) |

| Graduate degree | 48 (16) | 9 (24) | 5 (5) | 10 (12) | 24 (28) |

| Doctoral degree | 31 (10) | 7 (18) | 2 (2) | 7 (8) | 15 (17) |

| Political Affiliation | |||||

| Democratic | 54 (18) | 2 (5) | 8 (9) | 6 (7) | 38 (44) |

| Republican | 155 (51) | 26 (68) | 44 (47) | 52 (60) | 33 (38) |

| No lean | 95 (31) | 10 (27) | 42 (44) | 28 (33) | 15 (18) |

| Occupation | |||||

| Physician | 11 (4) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 7 (8) |

| Nurse | 144 (47) | 20 (54) | 31 (33) | 49 (57) | 44 (51) |

| NP/PA | 5 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Pharmacist | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| CRT/RRT | 23 (7) | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 14 (16) | 2 (2) |

| Administrator | 11 (4) | 5 (13) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Allied health | 106 (35) | 7 (18) | 56 (60) | 17 (20) | 26 (30) |

| Clinical Area | |||||

| ICU | 95 (32) | 14 (37) | 20 (21) | 43 (51) | 18 (21) |

| Non-ICU | 116 (38) | 10 (27) | 41 (44) | 25 (29) | 40 (47) |

| Emergency room | 25 (8) | 5 (13) | 2 (2) | 9 (10) | 9 (10) |

| Outpatient | 68 (22) | 9 (23) | 31 (33) | 9 (10) | 19 (22) |

| Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine | |||||

| Definitely not | 121 (40) | 26 (69) | 56 (60) | 17 (20) | 22 (26) |

| Probably not | 102 (33) | 12 (31) | 31 (33) | 27 (31) | 32 (37) |

| Not sure | 81 (27) | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | 42 (49) | 32 (37) |

| Willingness to recommend COVID-19 vaccine | |||||

| Definitely not | 55 (18) | 22 (58) | 24 (25) | 8 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Probably not | 98 (32) | 14 (37) | 41 (44) | 25 (29) | 18 (21) |

| Not sure | 103 (39) | 2 (5) | 27 (29) | 41 (48) | 33 (38) |

| Probably yes | 35 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 7 (8) | 26 (31) |

| Definitely yes | 13 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (6) | 8 (9) |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy | |||||

| Accurate | 119 (39) | 6 (16) | 24 (25) | 40 (47) | 49 (57) |

| Underestimate | 185 (61) | 32 (84) | 70 (75) | 46 (53) | 37 (43) |

| Recent Flu vaccination receipt | |||||

| Yes | 195 (64) | 12 (41) | 62 (66) | 53 (61) | 68 (79) |

| No | 109 (36) | 26 (59) | 32 (34) | 33 (39) | 18 (21) |

| Perceived likelihood of dying from COVID-19 | |||||

| Low | 261 (86) | 33 (87) | 90 (96) | 63 (73) | 75 (87) |

| Average | 21 (7) | 3 (8) | 2 (2) | 12 (14) | 4 (5) |

| High | 22 (7) | 2 (5) | 2 (2) | 11 (13) | 7 (8) |

| Estimated mortality from COVID-19 | |||||

| Underestimate | 137 (45) | 29 (76) | 55 (58) | 31 (36) | 22 (26) |

| Accurate | 119 (39) | 8 (21) | 29 (31) | 38 (44) | 44 (51) |

| High | 48 (16) | 1 (3) | 10 (11) | 17 (20) | 20 (23) |

| Seasonal flu is more contagious than COVID-19 | |||||

| Yes | 68 (22) | 30 (79) | 18 (19) | 12 (14) | 8 (9) |

| No | 93 (31) | 2 (5) | 19 (20) | 31 (36) | 41 (48) |

| Not sure | 142 (47) | 6 (16) | 57 (61) | 43 (50) | 37 (43) |

| Seasonal flu is deadlier than COVID-19 | |||||

| Yes | 48 (16) | 24 (63) | 15 (16) | 5 (6) | 4 (5) |

| No | 136 (45) | 4 (10) | 19 (20) | 66 (77) | 47 (55) |

| Not sure | 120 (39) | 10 (26) | 60 (64) | 15 (17) | 35 (40) |

| COVID-19 is a manmade virus | |||||

| Yes | 108 (35) | 35 (92) | 40 (42) | 22 (25) | 11 (13) |

| No | 94 (31) | 2 (5) | 17 (18) | 13 (15) | 62 (72) |

| Not sure | 102 (34) | 1 (3) | 37 (40) | 51 (60) | 13 (15) |

| COVID-19 is a hoax | |||||

| Yes | 32 (10) | 27 (71) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| No | 238 (78) | 5 (13) | 69 (73) | 79 (92) | 85 (99) |

| Not sure | 33 (11) | 6 (16) | 22 (25) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) |

| The impact of COVID-19 is exaggerated | |||||

| Yes | 104 (33) | 34 (89) | 50 (53) | 11 (13) | 9 (10) |

| No | 153 (50) | 1 (3) | 24 (25) | 60 (70) | 68 (80) |

| Not sure | 47 (15) | 3 (8) | 20 (22) | 15 (17) | 9 (10) |

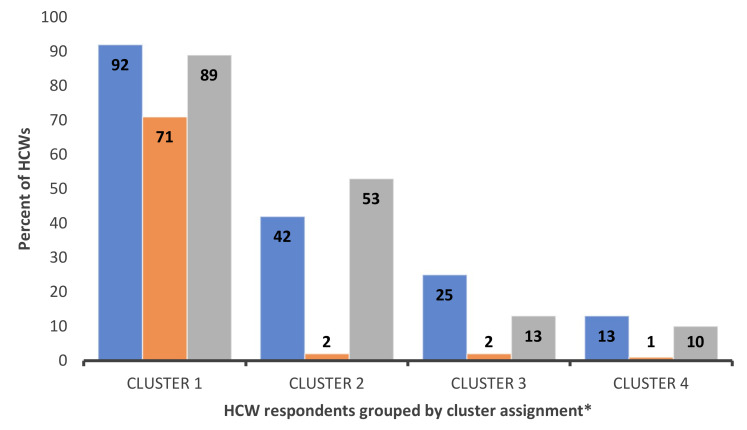

Respondents grouped in cluster 1 “misinformed” (n = 38) were slightly older and leaned Republican. They strongly opposed the COVID-19 vaccine, refusing to receive and/or recommend the COVID-19 vaccine. This group underestimated both the COVID-19 vaccine’s efficacy and COVID-19 mortality. They consider seasonal flu as more contagious and deadly than the COVID-19 virus. Finally, members of this cluster were more likely to believe several COVID-19 conspiracies (e.g., COVID-19 is a hoax). As seen in Figure 1, members of this group are subjects of disinformation from politically leaning news media.

Figure 1.

HCW support of COVID-19 conspiracy theories by cluster. Blue: HCWs that believe COVID-19 is a manmade virus; Orange: HCWs that believe COVID-19 is a hoax; Grey: HCWs that believe the impact of COVID-19 is exaggerated; * Cluster derivation and definitions are provided in surrounding text.

Members of cluster 2 “uninformed” (n = 94) tended to be less educated (60% lacking undergraduate degree), were more likely Hispanic/Latinx (47%), and worked in outpatient areas (33%) as allied health providers (60%). This cluster is the second least willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. This group underestimated the impact of the pandemic and the efficacy of the vaccine. They were primarily unsure about comparisons between COVID-19 and seasonal influenza. Unlike members of cluster 1, this group is less impacted by disinformation but lacks access to reliable and easy-to-understand vaccine information.

Cluster 3 “undecided” (n = 86) members were more open to receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, with half of the respondents unsure about vaccine receipt. Members of this cluster were predominantly White nurses and respiratory therapists working in an ICU. They understood the personal risk of exposure to the virus and knew the severity of COVID-19 disease, correctly assuming it is deadlier than seasonal flu. Participants in this cluster strongly leaned Republican.

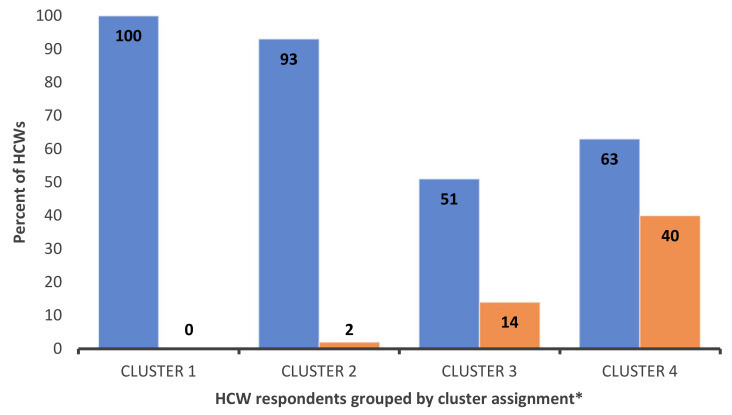

Cluster 4 “unconcerned” (n = 86) members were younger and racially diverse. This cluster is the most educated and leaned Democrat. Members of this cluster had an accurate knowledge of the vaccine’s efficacy and the lowest support of COVID-19 conspiracies. While hesitating to receive the vaccine themselves, respondents in this cluster were willing to recommend it to others (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HCWs willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine versus willingness to recommend vaccine to others. Blue: HCWs that probably or definitely would NOT receive COVID-19 vaccine; Orange: HCWs that probably or definitely WOULD recommend COVID-19 vaccine to others; * Cluster derivation and definitions are provided in surrounding text.

4. Discussion

We found that HCWs are a heterogeneous group with varying attitudes toward vaccination. In our cohort of 2491 HCWs who had been offered the vaccine and responded to our survey, 2109 (84%) were vaccinated, and 304 (12%) were vaccine-hesitant. Vaccination and hesitancy rates varied by age, ethnicity, professional roles, work setting, political affiliation, attitudes toward influenza vaccination, and knowledge of both COVID-19 severity and vaccine efficacy. Furthermore, HCWs who believe that the media has exaggerated the severity of the pandemic perceived the risk of vaccination to be greater than the risk of infection. Our findings parallel those of other studies [8,22,23,24,25] and underscore the importance of tailored communication strategies to disseminate scientific data to increase HCWs’ confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine.

We found that vaccine hesitancy was associated with older age and higher education. In additional analyses, age and education positively correlated with political affiliation (Republican) and occupation (nurse), respectively. Highly educated nurses were more hesitant to accept vaccination, often citing concerns in open-ended comments over unrealized side-effects of the vaccination, including its potential impact on fertility and pregnancy. HCWs who were leaning Republican tended to be older and more hesitant of COVID-19 vaccination. This underscores the politicized nature of the pandemic and the potential of one’s political affiliation to have a more substantial influence on vaccination decisions than age and susceptibility to the virus [6]. This finding is in line with surveys of the general public [26,27,28]. Prior COVID diagnosis was also associated with vaccine hesitancy, potentially reflecting HCWs’ preference for physiological immunity. Finally, as in other studies [29,30,31], one’s family size was predictive of vaccine hesitancy. This finding can be explained through interrelated factors, including socioeconomic status.

Trust is the essential factor in gaining acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. Alongside the public, HCWs have been exposed to conspiracy theories such as claims that the government intentionally created COVID-19 or that health organizations have exaggerated its lethality for financial or political purposes. These conspiratorial beliefs were strongly associated with vaccine refusal and were not limited to HCWs with lower education. Cognitive biases can be an underlying cause of conspiratorial beliefs even among educated HCWs. For instance, the availability heuristic may skew their perception of vaccination safety, while confirmation bias may strengthen their vaccine hesitancy through selective exposure to evidence [32,33]. HCWs financially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic were likely to exhibit vaccine skepticism. This finding may point to the difference between COVID-19 disinformation among White and well-educated HCWs and inequality-driven medical mistrust among racially diverse groups of HCWs made vulnerable by the pandemic.

We found four distinct clusters among vaccine-hesitant HCWs, suggesting that the dichotomous “anti-vaccine vs. pro-vaccine” separation of HCWs may not be adequate in informing interventions.

Cluster 1 members (misinformed) are dominated by vaccine-related myths and skeptical attitudes toward vaccine effectiveness. This cluster is the highest on the vaccine hesitancy continuum but also the smallest. Building trust within this group may be challenging and require strategies that utilize direct peer-to-peer communication [34]. For instance, HCWs may become “vaccine ambassadors” by directly engaging their colleagues in common settings (e.g., social media groups) and addressing relevant misinformation, as modeled by the “Nurses Who Vaccinate” organization members. However, directly reacting to misinformation may produce backlash among members of this cluster [35]. A stronger approach is to adopt methods used by the anti-vaccination movement, relying on personal and emotional narratives [36]. These narratives may center on “conversion” of an anti-vaccination HCW to pro-vaccine ideology [37] or stories highlighting personal risks of COVID-19 that can be avoided through vaccination [38]. Vaccine mandates may also be effective in increasing uptake among this group. However, mandates carry the risk of completely isolating this group and losing them to the profession at a time with an already high dropout due to COVID-19 and other burn-out [39].

Cluster 2 (uninformed) appears to be the sub-group of HCWs with the greatest need for accurate and easy-to-understand vaccine information. An educational campaign providing evidence-based information on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccination, with contents addressing their concerns, could further COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in this group [40]. Such an educational campaign needs to employ various communication channels, including printed materials, email blasts, social media, and short videos. This group seems to be negatively affected by the changing and evolving information around COVID-19. Clearer messaging about the reasons and need for evolving recommendations are essential for this group. This messaging can be achieved by hosting open discussions where HCWs at different levels can provide input and ask questions.

Members of cluster 3 (undecided) are the closest to acceptance on the vaccine hesitancy continuum. Their hesitancy may be attributed to partisan group identity. Several communication strategies can be effective in reaching this group. One is to highlight the non-partisan nature of vaccination decisions and endorsement of the COVID-19 vaccine from various political figures [41]. It is important to emphasize that vaccination is a social contract in which cooperation is the morally correct choice [42]. Leveraging social norm cues is another tactic to increase vaccination in this group. Several studies have documented the impact of perceived vaccine coverage in the social circle on vaccination behavior for influenza [43] and HPV [44]. Additionally, members of this group might be more inclined to accept vaccination resulting from a personal choice rather than coercion. Motivational interviewing is an effective approach to support a sense of personal freedom while decreasing vaccine hesitancy. Both CDC [45] and WHO [46] have released training modules describing this technique.

Finally, cluster 4 (unconcerned) are willing to recommend vaccination to others but have not been vaccinated themselves (yet). Their hesitancy may stem from under-estimating personal risks. Interventions rooted in behavioral economics (nudges) may increase vaccination rates in this group [47]. For instance, some hospitals use peer pressure to encourage vaccination (e.g., HCWs wearing “I am vaccinated” badges, public posting of vaccination rates) [48]. Pre-scheduling vaccination appointments or providing vaccination bonuses are promising evidence-based nudges to reach this group [49]. Additionally, messaging promoting prosocial motivations (e.g., protecting one’s community from COVID-19) can enhance vaccination intentions in this group [50].

Limitations

While our study has many strengths, including recruitment from both a public and private hospital system, and across a broad range of HCWs, in this constantly evolving response to the pandemic, it is limited by its “point in time”, to a time when vaccinations were fairly new. Our response rate of 20.9% introduces nonresponse bias and may not be fully representative of the HCWs population at the two hospital systems or generalized to other hospital systems. However, this response rate mirrors other surveys on the same topic systematically reviewed by Li et al. [11]. As there is no scientifically proven lower limit for an accepted survey response rate, several approaches, such as early- to late-responder comparisons, may help address nonresponse bias. For our study, there were no significant differences between the early and late responders. Additionally, our study is cross-sectional and does not allow us to establish temporal causality, explore vaccination uptake and relies on self-report. It is likely that HCWs’ opinions on vaccination evolved over time. Hence, future surveys using validated instruments and relying on vaccination rates are needed to capture these changes. In this survey, anonymity was stressed, and the pressure to be vaccinated had not yet been a public discussion. This likely resulted in important information that later may have been harder to obtain. Our results remain highly relevant, even when California legislation now calls for mandated HCW vaccination. Vaccination mandates have minimal influence on vaccine hesitancy. According to several recent surveys [51], about 50% of vaccine-hesitant HCWs would quit, start looking for other employment or both if their hospital system introduced a mandate. Our data point to important subgroups that need to be engaged as it is HCWs’ advice that will help sway public uptake of vaccination. Our clusters, each in their own way, will need to be convinced of the “why” as they play an important role in reaching similarly minded groups of vaccine-hesitant communities that are often in close contact (echo chambers).

5. Conclusions

HCWs have a strong influence on patient and public perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccines, and therefore are one of the most valuable assets in disease prevention. Unvaccinated HCWs are less likely to recommend the vaccine to others [6,8]. Vaccine hesitancy is the most significant barrier to achieving herd immunity, thus contributing to lingering infection and mortality within strained healthcare systems [4,52]. Our study found diversity in vaccine hesitancy among HCWs and highlights the need for unique and targeted interventions depending on degrees, types, and causes of hesitancy. Consequently, messaging should be tailored to specific subgroups to increase the understanding of the science behind vaccines. Interventions should elicit HCWs’ concerns with empathy, and policymaking should be inclusive of vaccine-hesitant subgroups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.C., L.K.L. and P.P.; methodology, L.K.L., A.A.C. and W.L.B.; formal analysis, A.D., B.J.D. and U.E.O.; investigation, S.T.; data curation, A.D., P.P. and U.E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., J.C.A.-M. and B.P.; writing—review and editing, A.D., J.C.A.-M., B.P., S.B.M., S.S. and A.A.C.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, S.S. and S.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) NIMH grant MH58107. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed by the respective IRBs of each participating institution and deemed exempt.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to institutional policies and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request in a controlled access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Reports. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports.

- 3.Food and Drug Administration COVID-19 Vaccines. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines.

- 4.World Health Organization Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- 5.Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., Srouji S., Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020;35:775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shekhar R., Sheikh A.B., Upadhyay S., Singh M., Kottewar S., Mir H., Barrett E., Pal S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines. 2021;9:119. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontanet A., Cauchemez S. COVID-19 herd immunity: Where are we. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:583–584. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterson P., Meurice F., Stanberry L.R., Glismann S., Rosenthal S.L., Larson H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–6706. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamieson K.H., Albarracin D. The Relation between Media Consumption and Misinformation at the Outset of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the US. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirzinger A., Munana C., Brodie M. Vaccine Hesitancy in Rural America. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronaviruscovid-19/poll-finding/vaccine-hesitancy-in-rural-america/

- 11.Li M., Luo Y., Watson R., Zheng Y., Ren J., Tang J., Chen Y. Healthcare workers’ (HCWs) attitudes and related factors towards COVID-19 vaccination: A rapid systematic review. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021 doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswas N., Mustapha T., Khubchandani J., Price J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health. 2021;46:1244–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Medical Association AMA Survey Shows Over 96% of Doctors Fully Vaccinated against COVID-19. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-survey-shows-over-96-doctors-fully-vaccinated-against-covid-19.

- 14.Gharpure R., Guo A., Bishnoi C.K., Patel U., Gifford D., Tippins A., Jaffe A., Shulman E., Stone N., Mungai E., et al. Early COVID-19 First-Dose Vaccination Coverage among Residents and Staff Members of Skilled Nursing Facilities Participating in the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program-United States, December 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:178–182. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilboa M., Tal I., Levin E.G., Segal S., Belkin A., Zilberman-Daniels T., Biber A., Rubin C., Rahav G., Regev-Yochay G. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination uptake among healthcare workers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021;46:1–6. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burden S., Henshall C., Oshikanlu R. Harnessing the nursing contribution to COVID-19 mass vaccination programmes: Addressing hesitancy and promoting confidence. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77:e16–e20. doi: 10.1111/jan.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SteelFisher G.K., Blendon R.J., Caporello H. An Uncertain Public-Encouraging Acceptance of Covid-19 Vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:1483–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2100351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabachnick B.G., Fiddell L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics. 7th ed. Volume 5. Pearson; New York, NY, USA: 2007. pp. 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milligan G.W. A Monte-Carlo study of 30 internal criterion measures for cluster-analysis. Psychometrika. 1981;46:187–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02293899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krolak-Schwedt S., Eckes T. A Graph Theoretic Criterion for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Data Set. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1992;27:541–565. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2704_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milligan G.W., Cooper M.C. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika. 1985;50:159–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02294245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciardi F., Menon V., Jensen J.L., Shariff M.A., Pillai A., Venugopal U., Kasubhai M., Dimitrov V., Kanna B., Poole B.D. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions of COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers of an Inner-City Hospital in New York. Vaccines. 2021;9:516. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grochowska M., Ratajczak A., Zdunek G., Adamiec A., Waszkiewicz P., Feleszko W. A Comparison of the Level of Acceptance and Hesitancy towards the Influenza Vaccine and the Forthcoming COVID-19 Vaccine in the Medical Community. Vaccines. 2021;9:475. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadoth A., Halbrook M., Martin-Blais R., Gray A., Tobin N.H., Ferbas K.G., Aldrovandi G.M., Rimoin A.W. Cross-sectional Assessment of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Health Care Workers in Los Angeles. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021;174:882–885. doi: 10.7326/M20-7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver K., Raut A., Pierre S., Silvera L., Boulos A., Gale A., Baum A., Chory A., Davis N., D’Souza D., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine receipt at two integrated healthcare systems in New York City: A Cross sectional study of healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.24.21253489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milligan M.A., Hoyt D.L., Gold A.K., Hiserodt M., Otto M.W. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: Influential roles of political party and religiosity. Psychol. Health Med. 2021;46:1–11. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1969026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisel O. Vaccination as a social contract: The case of COVID-19 and US political partisanship. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2026745118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026745118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz J.B., Bell R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021;39:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudson A., Montelpare W.J. Predictors of vaccine hesitancy: Implications for COVID-19 public health messaging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:8054. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher K.A., Bloomstone S.J., Walder J., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Mazor K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173:964–973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Dobalian A., Ward K.D. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Determinants among Adults with a History of Tobacco or marijuana use. J. Community Health. 2021;46:1090–1098. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00993-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stolle L.B., Nalamasu R., Pergolizzi J.V., Varrassi G., Magnusson P., LeQuang J., Breve F. Fact vs. fallacy: The anti-vaccine Discussion Reloaded. Adv. Ther. 2020;37:4481–4490. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan W., Liu D., Fang J. An Examination of Factors Contributing to the Acceptance of Online Health Misinformation. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:524. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moniz M.H., Townsel C., Wagner A.L., Zikmund-Fisher B.J., Hawley S., Jiang C., Stout M.J. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Healthcare Workers in a United States Medical Center. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.29.21256186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ball P., Maxmen A. The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature. 2020;581:371–374. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01452-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou W.S., Budenz A. Considering emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: Addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Commun. 2020;35:1718–1722. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latkin C., Dayton L.A., Yi G., Konstantopoulos A., Park J., Maulsby C., Kong X. COVID-19 vaccine intentions in the United States, a social-ecological framework. Vaccine. 2021;39:2288–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Islam M.S., Kamal A.M., Kabir A., Southern D.L., Khan S.H., Hasan S.M.M., Sarkar T., Sharmin S., Das S., Roy T., et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0251605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klompas M., Pearson M., Morris C. The Case for Mandating COVID-19 Vaccines for Health Care Workers. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021;174:1305–1307. doi: 10.7326/M21-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dzieciolowska S., Hamel D., Gadio S., Dionne M., Gagnon D., Robitaille L., Cook E., Caron I., Talib A., Parkes L., et al. Covid-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among Canadian healthcare workers: A multicenter survey. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021;49:1152–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.04.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palm R., Bolsen T., Kingsland J.T. The Effect of Frames on COVID-19 Vaccine Resistance. Front. Political Sci. 2021;3:41. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.661257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korn L., Böhm R., Meier N.W., Betsch C. Vaccination as a social contract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:14890–14899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919666117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruine de Bruin W., Parker A.M., Galesic M., Vardavas R. Reports of social circles’ and own vaccination behavior: A national longitudinal survey. Health Psychol. 2019;38:975–983. doi: 10.1037/hea0000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen J.D., Mohllajee A.P., Shelton R.C., Othus M.K., Fontenot H.B., Hanna R. Stage of adoption of the human papillomavirus vaccine among college women. Prev. Med. 2009;48:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines Among Your Patients. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/VaccinateWConfidence-TipsForHCTeams_508.pptx.

- 46.World Health Organization Conversations to Build Trust in Vaccination. A Training Module. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/TrainingModule_ConversationGuide_final.pptx?ua=1.

- 47.Pennycook G., McPhetres J., Zhang Y., Lu J.G., Rand D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020;31:770–780. doi: 10.1177/0956797620939054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chevallier C., Hacquin A.S., Mercier H. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Shortening the Last Mile. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021;25:331–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickland J.C., Reed D.D., Hursh S.R., Schwartz L.P., Foster R.N.S., Gelino B.W., Le Comte R.S., Oda F.S., Salzer A.R., Latkin C., et al. Integrating Operant and Cognitive Behavioral Economics to Inform Infectious Disease Response: Prevention, Testing, and Vaccination in the COVID-19 Pandemic. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.20.21250195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rutten L.J.F., Zhu X., Leppin A.L., Ridgeway J.L., Swift M.D., Griffin J.M., St Sauver J.L., Virk A., Jacobson R.M. Evidence-Based Strategies for Clinical Organizations to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021;96:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamel L., Lopes L., Kearney A., Sparks G., Stokes M., Brodie M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. [(accessed on 17 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-june-2021/

- 52.Paul E., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021;1:100012. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to institutional policies and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request in a controlled access.