Abstract

One of the common long-term consequences observed in survivors of COVID-19 pneumonia is the persistence of respiratory symptoms and/or radiological lung abnormalities. The exact prevalence of these post-COVID pulmonary changes is yet unclear. Few authors, based on their early observations, have labeled these persistent computed tomography (CT) abnormalities as post-COVID lung fibrosis, which appears to be an overstatement. Lately, it is being observed that many of the changes seen in post-COVID lungs are temporary and tend to show resolution on follow-up, with only a few developing into lung fibrosis. Thus, based on the presumptive diagnosis of lung fibrosis, these patients should not be blindly started on anti-fibrotic drugs. One must not forget that these drugs can do more harm than good, if used injudiciously. It is better to use the term “post-COVID interstitial lung changes”, which covers a broader spectrum of pulmonary changes seen in patients who have recovered from COVID-19 pneumonia. At the same time, it is essential to identify the sub-set of COVID-19 survivors who are at an increased risk of developing lung fibrosis and to carefully chalk out management strategies so as to modify the course of the disease and prevent irreversible damage. Meticulous and systematic longitudinal follow-up studies consisting of clinical, laboratory, imaging, and pulmonary function tests are needed for the exact estimation of the burden of lung fibrosis, to understand the nature of residual pulmonary changes, and to predict the likelihood of development of lung fibrosis in COVID-19 survivors.

KEY WORDS: Lung fibrosis, PC-ILC, post-COVID interstitial lung changes, post-COVID pulmonary fibrosis

Background

As the COVID-19 pandemic is unfolding, apart from the acute illness, there is now an emerging concern about its multisystemic involvement and frequently encountered long-term complications.[1] Nearly one-third of subjects recovered from COVID-19 pneumonia report a persistence of pulmonary abnormalities in their post-recovery phase.[2] The true nature of the long-term pulmonary sequelae, as seen clinically or on imaging, is at present unclear. Based on the early observation of these persistent or residual pulmonary changes on computed tomography (CT), some authors have labeled them as 'lung fibrosis',[2] which appears to be an overstatement as lung fibrosis denotes permanent and irreversible damage or scar formation in the lungs, and raises serious prognostic concerns. However, recent evidence show the temporary nature of these pulmonary changes in a significant majority of COVID-19 survivors. A recent study by Liu C et al.[3] revealed gradual absorption of lung abnormalities in COVID-19 subjects on subsequent follow-up CT, with 67.4% of patients showing complete recovery at four weeks after discharge. This observation of the reversible nature of abnormalities is also in concordance with our early clinical experience with post-COVID conditions in one of India's tertiary-care hospitals having a dedicated COVID-19 wing. Thus, it is better to use the term “post-COVID interstitial lung changes” over “lung fibrosis” to encompass a broader spectrum of pulmonary changes that are seen in patients recovered from COVID-19 pneumonia. The present paper aims to stress that in a significant majority of COVID-19 survivors, the residual lung changes observed during follow-up are temporary and seen to regress with time, with only a small fraction of these individuals developing frank lung fibrosis. We have also attempted to evaluate the predictive factors that can help triage COVID-19 survivors who will be at an increased risk of developing lung fibrosis.

Dilemma of post-COVID lung fibrosis

The peripherally distributed, bilateral, diffuse ground-glass opacities (GGOs), consolidation, reticulations, or mixed pattern of lesions are the typical imaging features seen in acute COVID-19 pneumonia.[4] CT plays a vital role in the evaluation of acute and recovered COVID-19 pneumonia subjects (follow-up).[5] Some of these abnormalities are seen to persist even in the convalescent or recovery phase. Yu M et al.[6] reported lung fibrosis (in the form of persistence of interstitial thickening, air bronchogram, irregular interface, coarse reticular pattern, and parenchymal bands) in 14 of the 32 patients evaluated in their post-recovery phase. In another long-term follow-up study done on a small group of patients (n = 11) during previous SARS epidemic, Wu X et al.[7] reported the persistence of reticulation and GGOs in 10 patients and traction bronchiectasis in 2 patients at 84 months follow-up. In contrast, Liu D et al.[8] reported resolution of CT abnormalities in 79% of the post-COVID subjects (n = 149) at the 4th week of follow-up. Such contradictory findings in the literature stimulate one to understand that the present information regarding the pulmonary changes is speculative, and larger prospective cohort studies are required to solve the query regarding the actual estimation of the prevalence of pulmonary fibrosis following COVID-19 pneumonia. The interstitial changes seen on CT in a majority of the patients during the recovery phase may be due to the residual persistent inflammation or secondary to reperfusion edema, and not due to fibrosis per se; it can disappear on follow-up [Figure 1]. Lesser fraction of patients may present with persistent pulmonary changes or with apparent fibrosis on long-term follow-up [Figures 2 and 3]. Further, longer-ranging observational studies to evaluate these changes on imaging and its correlation with pulmonary function tests are essential to differentiate these residual lung imaging findings from fibrotic lung disease. However, one must not forget that COVID-19 pneumonia has affected millions of people worldwide, and even a minuscule proportion with long-term complications like pulmonary fibrosis may result in considerable morbidity and mortality.

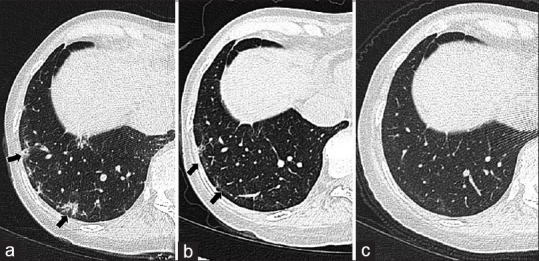

Figure 1.

Complete clearance of pulmonary findings. A 49-year-old female who recovered from acute COVID-19 pneumonia continued to have persistent dyspnea and myalgias in the post-recovery phase: (a) follow-up chest CT done at 30 days; (b) 60 days; and (c) 120 days after discharge from hospital showing gradual, but complete resorption of peripheral small areas of GGOs and reticulations in right basal lung (black arrows)

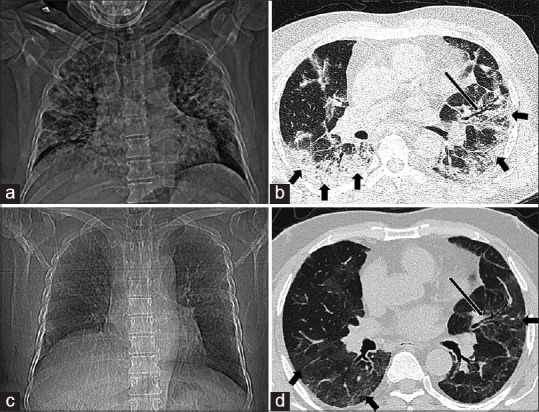

Figure 2.

Post-COVID interstitial lungs changes - partial clearance of parenchymal changes with persistent lower airway abnormalities. A 40-year-old male patient with diagnosis of severe COVID-19 pneumonia showing: (a) diffuse reticulonodular shadows in bilateral lungs on baseline chest radiograph; (b) diffuse peripheral consolidation (thick black arrows) with association mild bronchiectasis (long black arrow) on baseline CT with total severity score 20/25; (c) follow-up at 12 weeks after disease onset demonstrates clearance of previously seen reticulonodular shadows on frontal chest radiograph; and (d) subtle GGOs (thick black arrows) in peripheral lungs with persistent bronchiectasis (long black arrow) on follow-up CT

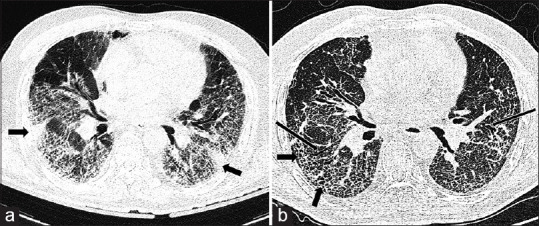

Figure 3.

Post-COVID interstitial lungs changes – progression of pulmonary changes to apparent fibrosis. A 60-year-old male patient with diagnosis of severe COVID-19 pneumonia showing: (a) multiple GGOs with patchy areas of consolidation (thick black arrows) in bilateral lungs with CT severity score 21/25 at the time of admission to the hospital; (b) follow-up high resolution CT after six months revealed predominant microcystic lung changes with septal thickening (thick black arrows) and tractional bronchiectasis (thin black arrows) suggestive of fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis can result from various causes related to age, chronic inflammation, toxic inhalants, genetic and idiopathic factors.[9] Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a known predisposing factor for pulmonary fibrosis, which is frequently seen in severe COVID-19 pneumonia.[10] Various other mechanisms, including direct viral injury and immune dysregulation are also implicated in pulmonary damage caused by SARS-CoV-2.[11] The ARDS is pathologically characterized by the diffuse alveolar damage in the inflammatory phase, followed by organizing and fibrous reactive phases, and can progress to irreversible lung abnormalities leading to lung fibrosis.[12] The release of tissue necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), metalloproteinases, and other growth factors, may incite pulmonary epithelial injury and intrapulmonary endotheliitis, which is believed to be the cause for post-COVID interstitial lung changes with or without associated pulmonary fibrosis.[13]

However, the stratification and early identification of subjects who are vulnerable to progressive pulmonary damage with COVID-19 pneumonia is a new challenge. The previous reports from the other coronavirus infections (SARS, MERS) as well as the short-term follow-up with post-COVID-19 subjects suggest that advanced age, severe or critical illness at presentation, underlying comorbidities (such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic renal disease, underlying malignancy, and immunosuppression), and abnormal laboratory parameters (including, leukocytosis, lymphopenia, increased D-dimer, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values) are predictive clinical and laboratory factors for the adverse pulmonary outcome.[14] Likewise, extensive pulmonary involvement on chest X-ray or CT, ventilator-induced lung injury, high viral load in circulation, chronic alcoholism, smoking, and genetic factors (blood group A, gene cluster on chromosome 3) are other suspected determinants responsible for persistent or progressive pulmonary damage in COVID-19 survivors.[14] A recently published prospective study has revealed that old age, male gender, cigarette smoking, high CT severity score, and long-term mechanical ventilation are associated with “post-COVID-19 pneumonia lung fibrosis”.[15]

There is no uniform consensus regarding the treatment of long-term sequelae of COVID-19 pneumonia. Low dose of corticosteroids is effective for prevention of lung remodeling following the infectious insult, and is associated with rapid and significant improvement.[16] The use of anti-fibrotic agents, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib in the sub-set of severe or critically ill COVID-19 survivors has been shown to decrease the fibrotic sequelae.[14] However, injudicious use of anti-fibrotic drugs even in the milder forms of residual pulmonary changes seem to have become a fad these days. It not only adds to an unnecessary cost burden, but can also do more harm than good in the form of adverse drug reactions in some subjects.[17,18] Prolonged administration of antiviral drugs, immunomodulators, and lung transplantation are the other options to prevent and treat pulmonary fibrosis.[18] Pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation, a healthy diet, and good psychological health are the general measures encouraged to practice with the belief of hastened pulmonary healing.[18] The periodic and systemic follow-up with post-COVID-19 subjects is pivotal, and the follow-up should depend upon the patient's condition at discharge.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the authors feel that it is not appropriate to label every patient with residual lung changes as pulmonary fibrosis in COVID-19 pneumonia survivors, and the novel anti-fibrotic therapy should not be used indiscriminately. However, at the same time, it is essential to remember that, even though the actual prevalence of pulmonary fibrosis may be small in COVID-19 survivors, it remains a considerable health concern, considering the vast number of COVID-19 cases worldwide. Further, systemic longitudinal follow-up studies consisting of clinical, laboratory, imaging, and pulmonary function tests are needed to estimate the exact burden and nature of residual pulmonary changes and lung fibrosis fibrosis in COVID-19 survivors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Garg S, Garg M, Prabhakar N, Malhotra P, Agarwal R. Unraveling the mystery of Covid-19 cytokine storm: From skin to organ systems. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13859. doi: 10.1111/dth.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mo X, Jian W, Su Z, Chen M, Peng H, Peng P, et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2001217. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu C, Ye L, Xia R, Zheng X, Yuan C, Wang Z, et al. Chest computed tomography and clinical follow-up of discharged patients with COVID-19 in Wenzhou City, Zhejiang, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:1231–7. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-324OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg M, Gupta P, Maralakunte M, Kumar-M P, Sinha A, Kang M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT and radiographic findings for novel coronavirus 2019 pneumonia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Imaging. 2021;72:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg M, Prabhakar N, Bhalla AS, Irodi A, Sehgal I, Debi U, et al. Computed tomography chest in COVID-19: When and why? Indian J Med Res. 2021;153:86–92. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_3669_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu M, Liu Y, Xu D, Zhang R, Lan L, Xu H. Prediction of the development of pulmonary fibrosis using serial thin-section CT and clinical features in patients discharged after treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:746–55. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Dong D, Ma D. Thin-section computed tomography manifestations during convalescence and long-term follow-up of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:2793–9. doi: 10.12659/MSM.896985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D, Zhang W, Pan F, Li L, Yang L, Zheng D, et al. The pulmonary sequalae in discharged patients with COVID-19: A short-term observational study. Respir Res. 2020;21:125. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01385-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: Mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:276–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934–43. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Zheng X, Tong Q, Li W, Wang B, Sutter K, et al. Overlapping and discrete aspects of the pathology and pathogenesis of the emerging human pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92:491–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Zhou H, Zhou Y, Wu X, Zhao Y, Lu Y, et al. Risk factors associated with disease severity and length of hospital stay in COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81:e95–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George PM, Wells AU, Jenkins RG. Pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19: The potential role for antifibrotic therapy. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:807–15. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30225-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udwadia ZF, Koul PA, Richeldi L. Post-COVID lung fibrosis: The tsunami that will follow the earthquake. Lung India. 2021;38(Suppl):S41–7. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_818_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali RM, Ghonimy MB. Post-COVID-19 pneumonia lung fibrosis: A worrisome sequelae in surviving patients. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2021;52:101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myall KJ, Mukherjee B, Castanheira AM, Lam JL, Benedetti G, Mak SM, et al. Persistent post-COVID-19 interstitial lung disease. An observational study of corticosteroid treatment. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:799–806. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-1002OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrisi SE, Pavone M, Vancheri A, Vancheri C. When to start and when to stop antifibrotic therapies. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:170053. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0053-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojo AS, Balogun SA, Williams OT, Ojo OS. Pulmonary fibrosis in COVID-19 survivors: Predictive factors and risk reduction strategies. Pulm Med. 2020;2020:6175964. doi: 10.1155/2020/6175964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]