Abstract

Croton lechleri, commonly known as Dragon’s blood, is a tree cultivated in the northwest Amazon rainforest of Ecuador and Peru. This tree produces a deep red latex which is composed of different natural products such as phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and others. The chemical structures of these natural products found in C. lechleri latex are promising corrosion inhibitors of admiralty brass (AB), due to the number of heteroatoms and π structures. In this work, three different extracts of C. lechleri latex were obtained, characterized phytochemically, and employed as novel green corrosion inhibitors of AB. The corrosion inhibition efficiency (IE%) was determined in an aqueous 0.5 M HCl solution by potentiodynamic polarization (Tafel plots) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, measuring current density and charge transfer resistance, respectively. In addition, surface characterization of AB was performed by scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy techniques. Chloroform alkaloid-rich extracts resulted in IE% of 57% at 50 ppm, attributed to the formation of a layer of organic compounds on the AB surface that hindered the dezincification process. The formulation of corrosion inhibitors from C. lechleri latex allows for the valorization of non-edible natural sources and the diversification of the offer of green corrosion inhibitors for the chemical treatment of heat exchangers.

Keywords: corrosion inhibition efficiency, admiralty brass, acid pickling solution, dragon’s blood, supercritical CO2 extraction, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, Tafel plots, linear polarization resistance, XPS, SEM-EDS

1. Introduction

Corrosion is the destructive electrochemical attack of a metal by the working environment [1]. The cost of prevention, maintenance, and replacement of damaged infrastructure associated with corrosive processes have been estimated as 5% of an industrialized nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) per year [2]. The design of heat exchangers, which are devices that transfer thermal energy (enthalpy) between two or more fluids [3], requires material with high thermal conductivity and a low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTA). Copper and its alloys are widely used materials for the construction of heat exchangers [4]. Admiralty brass (AB) shows excellent thermal properties (thermal conductivity of 110 W/m K and CTA of 2.02 × 10−5 °C−1) with a nominal chemical composition of 0.04% As, 71.00% Cu, 1.00% Sn, and 28.00% Zn [5]. However, the negative effects that fouling and corrosion products might have on the copper-based heat exchangers are well-document [6]. This issue can be mitigated by periodic cleaning with acid pickling solutions that contain a corrosion inhibitor to reduce or eliminate the destructive effects of the solution on the metal surface. A corrosion inhibitor is a chemical compound that is added in small concentration to a medium to decrease its corrosive nature [1]. The major industries that use inhibited pickling solutions for maintaining heat exchangers are oil and gas exploration and production, crude oil refining, chemical manufacturing, heavy manufacturing, and water desalination and treatment [7,8]. The corrosion inhibitor market was valued at $3.27 billion worldwide in 2017, with a total consumption of ca. 1.15 million tons [9]. Thiazole, triazole, and tetrazole derivatives are compounds widely employed as a base for the corrosion inhibitors’ formulation used in copper heat exchangers [10,11,12,13,14], but these compounds might have adverse effects on health and the environment [15,16]. Hence, the identification of green alternatives for corrosion inhibitors is required [17]. Natural products have been studied as corrosion inhibitors for which efficiencies are related to their chemical structure, composed in part by heteroatoms with free electron pairs such as O, N, and S capable to bond onto the metal surface [18,19]. Natural extracts that contain alkaloids and phenolic compounds have shown corrosion inhibition for mild steels, carbon steels, aluminum, and cooper in acidic media [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Croton lechleri is a tree of the family Euphorbiaceae, found in the northwest Amazon basin, especially, in the countries of Ecuador and Peru. This tree produces a deep red latex locally known as “Dragon’s blood”. This latex is used for healing wounds as well as a starting material in the isolation and purification of botanical drugs [27]. The chemical constituents of C. lechleri latex are proanthocyanidins, polyphenolic components [28], alkaloids such as tapsine [29], and minor amounts of terpenoid compounds [30]. Both the alkaloids and phenolic compounds contained in C. lechleri latex should exhibit inhibition corrosion properties on metallic specimens such as AB in acidic media. The extracts of at least three species of genus Croton have been evaluated as corrosion inhibitors with good results under acidic conditions [31,32,33].

The extraction of bioactive or functional compounds from vegetable matrices depends on the extraction technique and the solvents used [34]. Lyophilization, solvent and supercritical CO2 extraction are techniques employed to obtain high-quality products, with a good process yield, and low environmental impact [35,36,37]. Lyophilization is a concentration method that gently removes water from aqueous extracts [38]. It is performed at low temperature and reduced pressure, which eliminates the risks of heat degradation and bumping. In the case of latex samples, it is adequate for obtaining undamaged mixtures of solved and suspended solids. Soxhlet extraction is a classical extraction method for isolating a compound or a determined group of compounds according to the polarity of the solvent employed [34]. Supercritical fluid extraction with CO2 is an alternative non-toxic technique for extracting natural compounds at low temperatures with no use of contaminant solvents [39]. A related technique, named supercritical antisolvent extraction, can assist in overcoming the limited capacity of CO2 to dissolve polar compounds [40], resulting in micro- and nanoparticle-sized products [41].

In this study, we used lyophilization, solvent extraction, and supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction to obtain C. lechleri solid extracts for their characterization as novel green corrosion inhibitors of AB in hydrochloric acid media. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to identify C. lechleri extracts as corrosion inhibitors. Phytochemical characterization of the C. lechleri extracts showed the presence of alkaloid or phenolic compounds. The corrosion inhibition efficiency (IE%) was electrochemically determined for the three extracts on AB in hydrochloric acid. The corrosion inhibition mechanism of the extract with the highest inhibition efficiency was studied based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and superficial analyses, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray photoelectronic spectroscopy (XPS), indicating the formation of a protective layer of alkaloids on the AB surface.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lyophilization of C. lechleri Latex (CL1)

A total of 500 mL of Dragon’s blood was purchased from local producers from Tamiahurco village, Napo province, Ecuador. Six samples of 50 mL of C. lechleri latex were cooled at −60 °C in an ultra-freezer. Later, they were placed in a lyophilizer (SP Scientific–Genevac, BTP-9E LOVE, Stone Ridge, NY, USA) for five days until constant mass to produce a red-brown solid.

2.2. Chloroform Extract from C. lechleri Latex (CL2)

The 100 mL of C. lechleri latex was adjusted to pH 11 with KOH pellets (85%, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). After cooling down the mixture at 3 °C overnight, the resulting red-brown solid was submitted to Soxhlet extraction with 250 mL of chloroform (ACS, EMSURE®) for 12 h, twice. Then, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, yielding a beige solid.

2.3. Supercritical CO2 Antisolvent Extraction from C. lechleri Latex (CL3)

After lyophilization of the C. lechleri latex, 30 g of freeze-dried C. Lechleri underwent dynamic maceration with 500 mL of ethanol at atmospheric pressure and at 20 °C for 19 h. The final concentration of the ethanolic extract was adjusted to 30 mg/mL by vacuum evaporation. Then, CO2 flowed continuously at 10 L/min (atmospheric conditions) in a precipitator vessel at supercritical conditions (90 bar, 35 °C). Simultaneously, the ethanolic extract was allowed to flow at 1 mL/min through a 1 mm nozzle. When the supercritical CO2 and the ethanolic extract were in contact, an antisolvent extraction occurred (see Figure S1). The solvent and soluble compounds were extracted in the supercritical mixture of CO2-ethanol (waste) while the non-soluble compounds precipitated as dry particulate pink solid.

2.4. Quantitative Determination of Alkaloids in the Extracts from C. lechleri Latex

Then, 100 mL solutions were prepared with distilled water with concentrations of 1 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL for CL1, CL2 and CL3, respectively. Sample CL1 was subjected to a previous treatment whereby 10 mL of CL1 solution was adjusted at pH 2 with 2 M HCl followed by rinsing with 3 portions of CHCl3 and pH adjusting of the aqueous phase at 7, with 0.1 M NaOH. Then, 5 mL of CL1, CL2 and CL3 solutions were mixed with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered solution at pH 4.7 (prepared with 0.2 M sodium phosphate (96%, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA)) and 0.2 M citric acid (>99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) into a separatory funnel. After adding 5 mL of 0.1 mM bromocresol green (95%, Lobal Chemie, Mumbai, India) solution, four portions of CHCl3 were placed in the following order: 1 mL, 2 mL, 3 mL, and 4 mL. The resulting mixtures were shaken for 30 min in an automatic shaker. The organic phases were collected and dried over anhydrous magnesium sulphate and filtered. The resulting solution was poured in a 10 mL volumetric flask and the volume was completed with CHCl3. The total alkaloid content was determined by spectrophotometry UV-vis (Shimadzu, UV-3600 Plus, Kyoto, Japan) at 416 nm using an atropine (>99%, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) standard curve (0–12 µg/mL). Alkaloid values were expressed as atropine equivalents wt% of extract.

2.5. Determination of Total Phenols Content in the Extracts from C. lechleri Latex

Additionally, 10 mg of CL extracts were dissolved in 70% MeOH (ACS, EMSURE®). An aliquot of 0.5 mL of this solution was poured in a 10 mL volumetric flask. Then, 2 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (2 M, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) were added. The mixture was agitated for 2 min, followed by 5 min repose. Then, 1 mL of 20% Na2CO3 (>99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was added, and the volume was completed with 70% MeOH. The resulting mixture was left in the dark for 2 h. Finally, the total phenols content was determined by spectrophotometry UV-vis in the absorbance maximum of gallic acid (97.5–102.5%, Sigma Aldrich) standard curve (0–10 μg/mL). Total phenols values were expressed as gallic acid equivalents wt% of extract.

2.6. Electrochemical Determination of the Corrosion Inhibition Efficiency for the Extracts from C. lechleri Latex

Electrochemical measurements were made with potentiostats/galvanostats Autolab PGSTAT128N and Autolab MAC (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland), employing a three-electrode cell. Experiments were run with Nova 2.1. software. The working electrodes were made of copper admiralty (alloy C44300, nominal chemical composition of 0.0030% Pb, 0.0350% Fe, 0.0430% As, 71.8500% Cu, 1.0300% Sn, and 27.0000% Zn, Metal Samples, Co., Inc., Munford, AL, USA) with an exposed area of 0.283 cm2. After the specimen were mechanically ground with 220, 500, 1000, and 2000 emery paper, they were polished with 0.3 µm alumina and washed with ethanol and type I water, then dried, and placed in a cell. A Ag0/AgCl/KCl 3 M electrode (CHI111P, CH Instruments, Inc., Bee Cave, TX, USA) and a titanium plate were used as a reference and counter electrodes, respectively. Tafel essays were made by measuring the open circuit potential (OCP) for at least 1800 seconds. Then, a dynamic potential perturbation was applied from −200 mV to 200 mV vs. OCP at a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy essays were conducted polarizing the working electrode with an alternating signal of 5 mV amplitude, at the OCP, with frequencies from 0.1 Hz to 0.5 MHz. Data were analyzed employing Zview(R) and Origin 8.1. software.

2.7. Superficial Characterization of AB Electrodes

All samples were cleaned using compressed air to remove loose particles and other contaminants and placed in a charge-reduction sample holder. SEM micrographs and EDS spectra were measured with a Phenom ProX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an acceleration voltage of 15.0 kV at 0.5 mbar.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was performed using PHI VersaProbe III (Physical Electronics), equipped with a 180 hemispherical electron energy analyzer, using a monochromatized Al Kα source with energy 1486.6 eV. Energies bandpass of 255 kV and 55 kV were used for Survey and high-resolution operation. The spot size diameter was 100 μm. The polished AB sample was cleaned using a sputtering Ar gun for 3 min to remove carbon and oxidized material.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemical Screening of the Extracts from C. lechleri Latex

Three different techniques were used to obtain solid extracts from the latex of C. lechleri (see Figure S2). Lyophilization of the latex of C. lechleri produced a red-brown solid (CL1) with an 18 wt% yield. Chloroform Soxhlet extraction yielded a 0.17 wt% beige solid (CL2), while the supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction gave 1.84 wt% of a pink solid (CL3). Table 1 shows the alkaloid and phenolic compound contents for the three extracts. CL1 and CL3 are phenolic-rich extracts with 46.5 wt% and 52.2 wt%, respectively. CL2 is an alkaloid-rich extract with 51.9 wt% content. Extract CL1 showed both kinds of natural products, while extracts CL2 and CL3 were intentionally enriched in alkaloids and phenolic compounds, respectively. Extract CL2 was obtained after adjusting to alkaline con-ditions (pH = 11), which favored the extraction of alkaloids using chloroform [42]. On the other hand, the sample of the latex of C. lechleri was pretreated with ethanol to obtain CL3, which favored the extraction of phenolic compounds [28].

Table 1.

Alkaloids and phenolic compounds content for triplicated measurements of the solid extracts obtained from the C. lechleri latex.

| Entry | Alkaloid Content (wt. %) | Phenolic Compound Content (wt. %) |

|---|---|---|

| CL1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 46.5 ± 1.9 |

| CL2 | 51.9 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| CL3 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 52.2 ± 0.4 |

3.2. Potentiodynamic Polarization Plots of AB in HCl Media with the Extracts from C. lechleri Latex

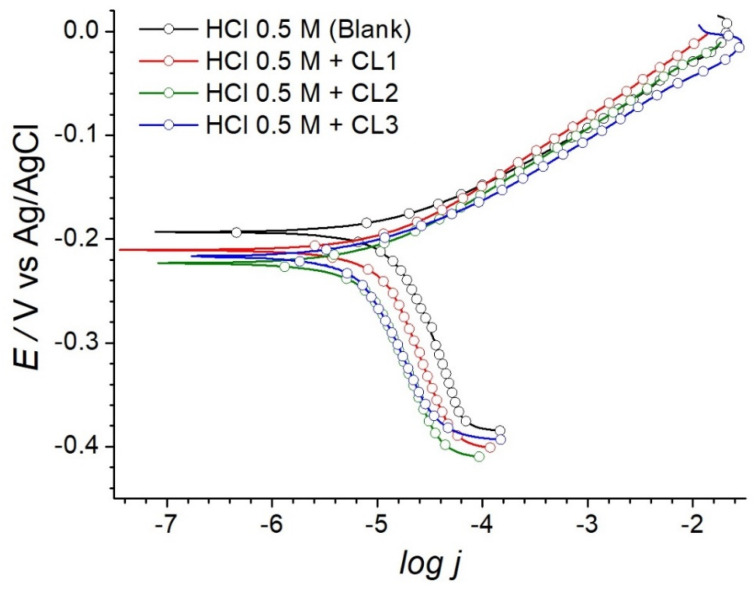

Figure 1 shows the potentiodynamic polarization curves for AB in 0.5 M hydrochloric acid aqueous solution at 25 °C employing the three different extracts from C. lechleri latex CL1, CL2, and CL3 at a concentration of 300 ppm, 50 ppm, and 200 ppm, respectively. The solubility limit was reached for the three extracts under the working conditions. In all cases, the corrosion current density decreased with the presence of the extracts, which indicates the corrosion inhibition on the surface of AB. These C. lechleri extracts could be classified as a mixed-type inhibitor because of a remarkable decrease in the cathodic as well as corrosion currents, with a slight decrease in the anodic currents and shift in the corrosion potential (Ecorr) to lower values [43,44]. This effect significantly increased with increased concentrations of CL3 from 50 ppm to 200 ppm (see Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Potentiodynamic polarization plots of AB in 0.5 M HCl in the presence of various extracts of extracts from C. lechleri latex at 25 °C.

Electrochemical parameters, including Ecorr, cathodic Tafel slope (βc), anodic Tafel slope (βa), corrosion current density (jcorr), and IE% are provided in Table 2. The jcorr and Ecorr were obtained from the extrapolation of anodic and cathodic Tafel linearized current regions. Values of IE% were determined using Equation (1) as follows:

| (1) |

where and jcorr represent the corrosion current densities in the absence and presence of inhibitor, respectively. CL1 inhibited in 30.48% the corrosion of AB in HCl media. The CL3 sample showed an improved inhibition of 48.93% compared to CL1, despite its lower concentration. This result might be related to a higher phenolics content and compound purification due to the supercritical antisolvent process [45]. Moreover, the size and the spheric shape of the particles obtained in CL3, which showed diameters of about 300–600 nm (see Figure S4), might increase the surface coverage area and availability compared to the coarse CL1 powder [46,47,48]. The IE% was found to increase continuously with an increase in the concentration of CL3 (see Table S2). The highest inhibition efficiency of 51.57% was reached with the alkaloid-rich CL2 in a low concentration of 50 ppm. The use of biomolecules for the formulation of corrosion inhibitors is expected to have a lower environmental impact compared to commercial inhibitors from chemical synthesis [49]. Hereafter, we focused on CL2 for further analysis to develop better insight into the inhibition process.

Table 2.

Tafel polarization parameters for AB in 0.5 M HCl with extracts from C. lechleri latex at 25 °C.

| Entry | Ecorr (V) | βc (mV/dec) | βa (mV/dec) | jcorr (μA/cm2) | IE% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCl 0.5 M | −0.193 | 281.6 | 53.8 | 14.84 | - |

| HCl 0.5 M + CL1 | −0.210 | 261.5 | 62.9 | 10.32 | 30.48 |

| HCl 0.5 M + CL2 | −0.211 | 241.5 | 57.5 | 7.19 | 51.57 |

| HCl 0.5 M + CL3 | −0.214 | 238.0 | 47.5 | 7.58 | 48.93 |

3.3. EIS of AB in HCl Media Inhibited with CL2

After Tafel measurements, EIS was carried out by varying the frequency from 0.1 Hz to 0.5 MHz. Equation (2) was used to calculate IE% as follows:

| (2) |

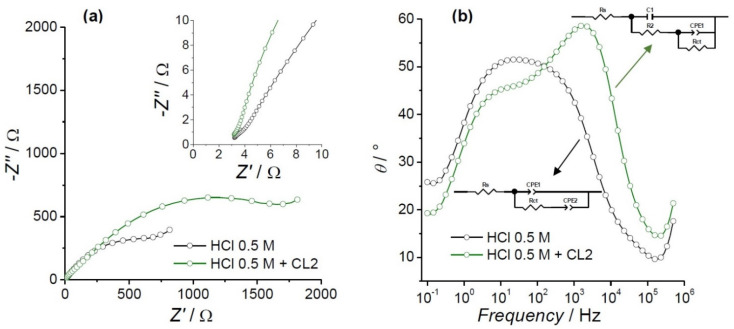

where and Rct represent the charge transfer resistance in the absence and presence of CL2, respectively. Figure 2 shows the impedance diagrams obtained in the presence and absence of 50 ppm of CL2 at Ecorr in HCl 0.5 M. The Nyquist plot reveals one loop at high frequencies (see Figure 2a inset). A second loop is observed at middle frequencies and the beginning of a diffusional impedance for both spectra (see Figure 2a). All loops are distorted semicircles. Deviations of the ideal semicircles can be attributed to the inhomogeneities on the alloy surface such as point defects, grain boundaries, and lattice distortions [50]. Independent of the polishing treatment, the admiralty surface formed oxide films by the contact of the metallic electrode with atmospheric or dissolved oxygen. This thin oxide layer is observed in the Nyquist plot as one loop at high frequencies.

Figure 2.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy diagrams of AB at Ecorr in 0.5 M HCl, in the absence (black lines) and the presence (green lines) of CL2: (a) Nyquist plots (inset: zoom in at high frequencies) and (b) Bode diagrams (insets: equivalent circuits).

The Nyquist spectra with and without the inhibitor were fitted using equivalent circuits (see Figure 2b insets), where Rs is the solution resistance, Rct is the charge transfer resistance, CPE1 and CPE2 are constant phase elements, R2 is the oxide film resistance, and C1 the capacitance for the oxide film. EIS fitting parameters are summarized in Table 3. For AB in HCl media, a CPE1 of 496.6 (µF)n was obtained with a value of n = 0.63, describing the behavior of the capacitor, while a value of 6.29 (mF)n was determined with n = 1.13 for the CPE2. For the impedance spectra, fitting in the presence of CL2, C1 was found to have a value of 3.45 µF. This circuit is composed of two-time constants nested, which indicate a porous or inhomogeneous layer onto the AB where the charge transfer occurs (see Figure 2b) [12]. Similar behavior was observed in a set of trials performed with different concentrations of CL3 (see Figure S5), where a new time constant emerged as the CL3 concentration increased. The increase of Rct in the presence of CL2 is due to the formation of a layer of inhibitor that prevents electronic interchange. An IE% of 57.15% was determined using Equation (2), comparable to the one determined by Tafel plots.

Table 3.

Results of resistance and goodness fit values from impedance measurements.

| Entry | Rs | Rct | R1 | Sum of Squares | IE% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCl 0.5 M | 3.049 | 1221 | - | 0.03649 | - |

| HCl 0.5 M + CL2 | 3.602 | 2850 | 19.83 | 0.24907 | 57.16 |

3.4. Investigation of the Morphology and Surperficial Composition of AB by SEM-EDS and XPS

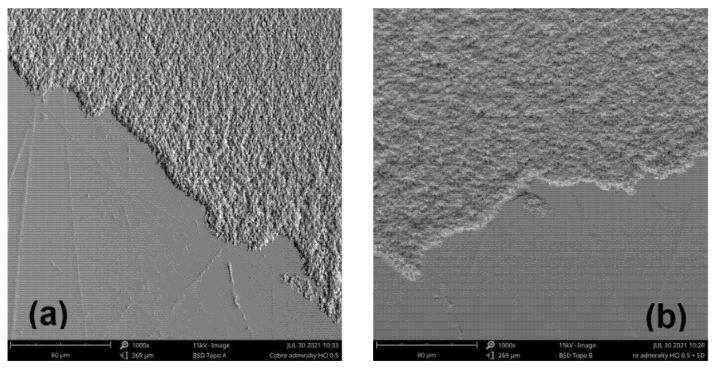

Figure 3 shows the SEM images of AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl solutions in the absence and presence of CL2 at 50 ppm. The surface of the metal sample was significantly damaged in the HCl solution, indicating a high level of corrosion (see Figure 3a), while in the presence of CL2, the surface of AB was smoother, indicating a decreased corrosion rate (see Figure 3b). This phenomenon might be related to the formation of a stable protective layer of CL2 on the AB surface.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of AB (a) in 0.5 M HCl and (b) in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2.

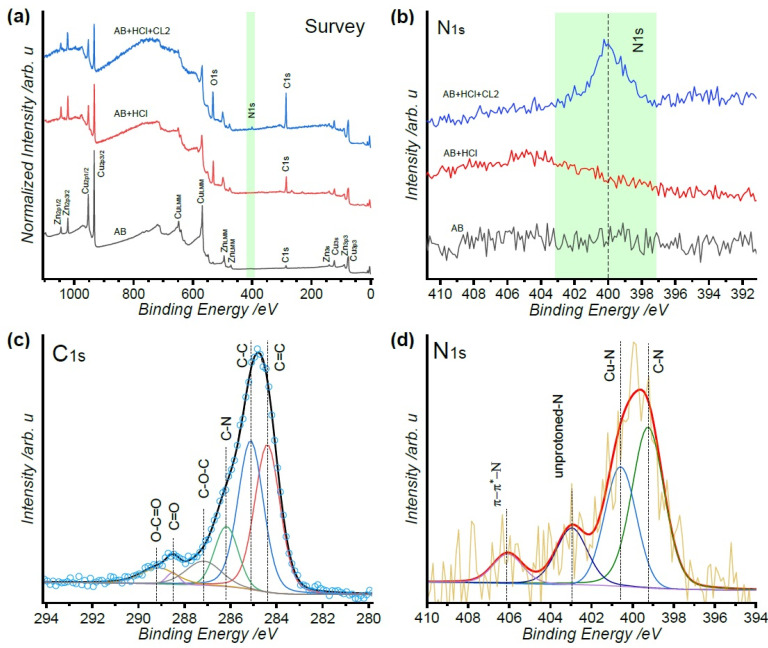

Comparative XPS survey spectra for a polished metal sample (black line), AB immersed in 0.5 M HCl (red line), and AB immersed in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2 (blue line) are shown in Figure 4a. The inhibited-metal sample presented increased oxygen and carbon peaks, which can be mainly attributed to the organic composition of alkaloid-rich CL2 deposition on the surface. Moreover, nitrogen was only observed in the AB surface treated in the presence of CL2 confirming the presence of an alkaloid-rich layer in the surface (see Figure 4b). This layer attenuated the metallic register intensity of copper and zinc. As shown in Figure 4c, the C1s core level presented several components such as C=C binding at 284.4 eV and C-C at 285.12 eV. A shoulder was attributed to C-N at 286.17 eV and three additional peaks at 287.16 eV, 288.5 eV, and 289.12 eV associated with C-O-C, C=O, and O-C=O, respectively [51,52]. These types of bonds can be found in the tapsine alkaloid (see Figure S6), which has been isolated from the latex of C. lechleri [29]. The N1s high-resolution feature presents chemical environments for C-N and Cu-N binding energies at 400.45 eV and 399.35 eV, respectively, an unprotonated N atom binding at 402.75 eV followed by π-π * plasmon at 406.06 eV, as presented in Figure 4d [53,54,55]. Thus, the alkaloid-rich extract CL2 can form a protective film on the AB/solution interface via the Cu-N coordination bonds through N lone pair and copper. This barrier film effectively hinders the corrosion of the AB substrate by the HCl medium. The Cu2p3 feature presented a typical orbital splitting with an ∆E = 19.9 eV for all the samples (see Figure S7a). The full width at half maximum (FWHM) changed from 1.293 eV for the polished metal sample to 1.414 eV for the corroded samples related to the formation of Cu(I). The latter was confirmed by the weak satellites at 947 eV. The behavior of Zn2p3 presented a splitting orbital with an increment of the FWHM from 1.479 eV for the polished AB to 1.863 eV for the corroded samples as well as a shift on the Zn2p3/2 peak of 0.394 eV, which was attributed to the formation of Zn(II) on the surface (see Figure S7b).

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of the (a) survey scan and (b) N1s for a polished AB (black line), AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl (red line), and AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2 (blue line). (c) C1s and (d) N1s spectra for the CL2 inhibited AB sample.

The mechanism of brass corrosion in acidic media has been reported as a two-step dezincification process [56]. Initially, zinc is preferentially or even selectively dissolved [57] followed by a dissolution–redeposition of copper on the alloy surface, generating copper-rich islands or porous films [58] as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Our experimental results agree with this process, as evidenced by the difference in the surface composition of Cu (70.48%) and Zn (29.42%) for a polished metal sample (see Figure S8) compared to the composition of Cu (82.12%) and Zn (17.88%) for AB treated in 0.5 M HCl (see Figure S9). The inhibition capacity of CL2 is attributed to the molecular structure of natural products that were enriched in alkaloid compounds. Tapsine structure shows two aromatic rings with π electrons and heteroatoms such as nitrogen and oxygen, that can interact with the d-orbitals of the metal by their lone pairs to form a well-adsorbed organic film. The layer, formed on the surface, can isolate the alloy from the corrosive solution, which has been observed in mixed-type inhibitors [59,60,61,62] as evidenced by the conserved surface composition of Cu (69.70%) and Zn (30.30%) for AB treated in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2 (see Figure S10). Furthermore, many alkaloids as well as other natural products form complexes with Cu+ or Zn2+ that prevents the formation of soluble metallic chlorides, limiting the overall oxidation process [63]. A comparison of the AB samples by the naked eye after immersion in 0.5 M HCl solution in the absence and presence of CL2 at 50 ppm showed the inhibition potential of dragon’s blood extracts (see Figure S11). From an industrial point of view, the formulation of corrosion inhibitors based on C. lechleri latex offers two opportunities—the valorization of a non-edible natural source and the diversification of the availability of corrosion inhibitors for the chemical treatment of equipment in different industrial sectors. These green corrosion inhibitors might provide an option for the corrosion mitigation in the cleaning process of heat exchangers increasing their lifecycle.

4. Conclusions

In summary, lyophilization, chloroform Soxhlet extraction, and supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction techniques were successfully employed to obtain novel green C. lechleri solid corrosion inhibitors of AB in 0.5 M HCl media. CL1, which is the dry C. lechleri latex, showed the presence of alkaloid and phenolic compounds with an IE% of 30.48%. Microparticles of CL3 enriched in phenolic content provided an IE% of 48.93%, while CL2 was enriched in alkaloid compounds showing an IE% of 57%. Adsorption onto the surface of AB of the alkaloid molecules in CL2 was proposed as the mechanism of corrosion by slowing down the dezincification process of the metal sample. Further purification and processing of CL2 should improve its solubility and corrosion-inhibition efficiency. Studies at various concentrations and temperatures as well as computational simulations are performing by our group to obtain information about the adsorption process and thermodynamics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alfredo Viloria, Paola Ordoñez, and Ruth Oropeza for the valuable discussion. We thank Elizabeth Mariño for the SEM images and EDS spectra. The authors would like to thank to Corporación Ecuatoriana para el Desarrollo de la Investigación y Academia-CEDIA for the financial support given to the present research, development, and innovation work through its CEPRA program, especially for the CEPRA XV-2021-015 fund.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online: Figure S1. Pilot plant of supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction of CL3. Table S1. Conditions of supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction of CL3. Figure S2. Photographs of solid extracts obtained from C. lechleri by lyophilization, solvent extraction, and supercritical CO2 antisolvent extraction. Figure S3. Potentiodynamic polarization plots of AB in 0.5 M HCl in the presence of CL3 at several concentrations at 25 °C. Figure S4. Microphotography of CL3 spherical particles. Table S2. Tafel polarization parameters for AB in 0.5 M HCl with CL3 at concentration of 50 ppm–200 ppm at 25 °C. Figure S5. Bode diagrams of AB at Ecorr in 0.5 M HCl at various concentrations of CL3. Figure S6. Chemical structure of tapsine. Figure S7. Cu2p3 and Zn2p3 XPS spectra for a polished AB, AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl, and AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2. Figure S8. EDS spectrum of a polished AB sample. Figure S9. EDS spectrum of AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl. Figure S10. EDS spectrum of AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2. Figure S11. Photographs of AB after immersion in 0.5 M HCl and 0.5 M HCl with 50 ppm CL2.

Author Contributions

A.P.-C., C.C.-M., P.C.-P., M.A.M. and M.d.C.G. conceived and designed the experiments. A.P.-C., C.C.-M., R.L., C.R., M.A.M. and M.d.C.G. performed the experiments. All authors analyzed the data. A.P.-C., C.C.-M., P.C.-P., C.R., M.A.M., M.R. and M.d.C.G. wrote the draft manuscript. A.P.-C. supervised the writing process and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Corporación Ecuatoriana para el Desarrollo de la Investigación y Academia-CEDIA, grant number CEPRA XV-2021-015.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Revie R.W., Uhlig H.H. Corrosion and Corrosion Control. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callister W.D., Rethwisch D.G. Materials Science and Engineering an Introduction. 9th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R.K., Sekuli D.P. Fundamentals of Heat Exchanger Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung D.D. Materials for thermal conduction. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2001;21:1593–1605. doi: 10.1016/S1359-4311(01)00042-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brass Alloy UNS C44300. [(accessed on 17 November 2021)]. Available online: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=6371.

- 6.Sherif E.-S.M., Erasmus R.M., Comins J.D. Inhibition of copper corrosion in acidic chloride pickling solutions by 5-(3-aminophenyl)-tetrazole as a corrosion inhibitor. Corros. Sci. 2008;50:3439–3445. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meroufel A.A. Corrosion and Fouling Control in Desalination Industry. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Germany: 2020. Corrosion Control during Acid Cleaning of Heat Exchangers; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramana Murthy R.V.V., Katari N.K., Satya Sree N., Jonnalagadda S.B. A novel protocol for reviving of oil and natural gas wells. Pet. Res. 2019;4:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ptlrs.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu M.-D., Xing N., Ai L.-S., Wang J., Chen X.-Y., Jiao Q.-Z., Shi L. Development of polyacid corrosion inhibitor with 2-vinylpyridine residue. Chem. Pap. 2021;75:6127–6135. doi: 10.1007/s11696-021-01728-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taha K.K., Mohamed M.E., Khalil S.A., Talab S.A. Inhibition of Brass Corrosion in Acid Medium Using Thiazoles. Int. Lett. Chem. Phys. Astron. 2013;14:87–102. doi: 10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILCPA.14.87. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benali O., Zebida M., Benhiba F., Zarrouk A., Maschke U. Carbon steel corrosion inhibition in H2SO4 0.5 M medium by thiazole-based molecules: Weight loss, electrochemical, XPS and molecular modeling approaches. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021;630:127556. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satpati A.K., Reddy A.V.R. Electrochemical Study on Corrosion Inhibition of Copper in Hydrochloric Acid Medium and the Rotating Ring-Disc Voltammetry for Studying the Dissolution. Int. J. Electrochem. 2011;2011:173462. doi: 10.4061/2011/173462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiang Y., Li H., Lan X. Self-assembling anchored film basing on two tetrazole derivatives for application to protect copper in sulfuric acid environment. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020;52:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiang Y., Guo L., Li H., Lan X. Fabrication of environmentally friendly Losartan potassium film for corrosion inhibition of mild steel in HCl medium. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;406:126863. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messina E., Giuliani C., Pascucci M., Riccucci C., Staccioli M.P., Albini M., Di Carlo G. Synergistic Inhibition Effect of Chitosan and L-Cysteine for the Protection of Copper-Based Alloys against Atmospheric Chloride-Induced Indoor Corrosion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:10321. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stupnišek-Lisac E., Gazivoda A., Madžarac M. Evaluation of non-toxic corrosion inhibitors for copper in sulphuric acid. Electrochim. Acta. 2002;47:4189–4194. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(02)00436-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang H.-M. Role of Organic and Eco-Friendly Inhibitors on the Corrosion Mitigation of Steel in Acidic Environments—A State-of-Art Review. Molecules. 2021;26:3473. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raja P.B., Sethuraman M.G. Natural products as corrosion inhibitor for metals in corrosive media—A review. Mater. Lett. 2008;62:113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2007.04.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiang Y., Zhang S., Tan B., Chen S. Evaluation of Ginkgo leaf extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor of X70 steel in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2018;133:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis G.D., Von Fraunhofer J.A., Krebs L.A., Dacres C.M. The use of tobacco extracts as corrosion inhibitors. NACE-Int. Corros. Conf. Ser. 2001;2001-March:NACE-01558. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebenso E.E., Eddy N.O., Odiongenyi A.O. Corrosion inhibitive properties and adsorption behaviour of ethanol extract of Piper guinensis as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in H2SO4. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;2:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okafor P.C., Ikpi M.E., Ekanem U.I., Ebenso E. Effects of extracts from nauclea latifolia on the dissolution of carbon steel in H2SO4 solutions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013;8:12278–12286. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kliskic M., Radosevic J., Gudic S., Katalinic V. Aqueous extract of Rosmarinus officinalis L. as inhibitor of Al ± Mg alloy corrosion in chloride solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2000;30:823–830. doi: 10.1023/A:1004041530105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berković K., Kovač S., Vorkapić-Furač J. Natural compounds as environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitors of aluminium. Acta Aliment. 2004;33:237–247. doi: 10.1556/AAlim.33.2004.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostovari A., Hoseinieh S.M., Peikari M., Shadizadeh S.R., Hashemi S.J. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1 M HCl solution by henna extract: A comparative study of the inhibition by henna and its constituents (Lawsone, Gallic acid, α-d-Glucose and Tannic acid) Corros. Sci. 2009;51:1935–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2009.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramanyam N.C., Sheshadri B.S., Mayanna S.M. Quinine and strychnine as corrosion inhibitors for copper in sulphuric acid. Br. Corros. J. 1984;19:177–180. doi: 10.1179/000705984798273128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleindl P.A., Xiong J., Hewarathna A., Mozziconacci O., Nariya M.K., Fisher A.C., Deeds E.J., Joshi S.B., Middaugh C.R., Schöneich C., et al. The Botanical Drug Substance Crofelemer as a Model System for Comparative Characterization of Complex Mixture Drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;106:3242–3256. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Marino S., Gala F., Zollo F., Vitalini S., Fico G., Visioli F., Iorizzi M. Identification of minor secondary metabolites from the latex of Croton lechleri (Muell-Arg) and evaluation of their antioxidant activity. Molecules. 2008;13:1219–1229. doi: 10.3390/molecules13061219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milanowski D.J., Winter R.E.K., Elvin-Lewis M.P.F., Lewis W.H. Geographic distribution of three alkaloid chemotypes of Croton lechleri. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:814–819. doi: 10.1021/np000270v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones K. Review of Sangre de Drago (Croton lechleri)—A South American Tree Sap in the Treatment of Diarrhea, Inflammation, Insect Bites, Viral Infections, and Wounds: Traditional Uses to Clinical Research. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2003;9:877–896. doi: 10.1089/107555303771952235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felipe M.B.M.C., Silva D.R., Martinez-Huitle C.A., Medeiros S.R.B., Maciel M.A.M. Effectiveness of Croton cajucara Benth on corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in saline medium. Mater. Corros. 2013;64:530–534. doi: 10.1002/maco.201206532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajeswari V., Kesavan D., Gopiraman M., Viswanathamurthi P., Poonkuzhali K., Palvannan T. Corrosion inhibition of Eleusine aegyptiaca and Croton rottleri leaf extracts on cast iron surface in 1 M HCl medium. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014;314:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geethamani P., Kasthuri P.K., Aejitha S., Geethamani P. Mitigation of mild steel corrosion in 1M sulphuric acid medium by Croton Sparciflorus A green inhibitor. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 2014;2:507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarker S.D., Nahar L., editors. Natural Products Isolation. 3rd ed. Volume 1. Humana Press; London, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azmir J., Zaidul I.S.M., Rahman M.M., Sharif K.M., Mohamed A., Sahena F., Jahurul M.H.A., Ghafoor K., Norulaini N.A.N., Omar A.K.M. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013;117:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gómez-García R., Campos D.A., Aguilar C.N., Madureira A.R., Pintado M. Valorisation of food agro-industrial by-products: From the past to the present and perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;299:113571. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lampakis D., Skenderidis P., Leontopoulos S. Technologies and Extraction Methods of Polyphenolic Compounds Derived from Pomegranate (Punica granatum) Peels. A Mini Review. Processes. 2021;9:236. doi: 10.3390/pr9020236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawasaki H., Shimanouchi T., Kimura Y. Recent Development of Optimization of Lyophilization Process. J. Chem. 2019;2019:9502856. doi: 10.1155/2019/9502856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reverchon E., De Marco I. Supercritical fluid extraction and fractionation of natural matter. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2006;38:146–166. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2006.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meneses M.A., Caputo G., Scognamiglio M., Reverchon E., Adami R. Antioxidant phenolic compounds recovery from Mangifera indica L. by-products by supercritical antisolvent extraction. J. Food Eng. 2015;163:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2015.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guamán-Balcázar M.C., Montes A., Fernández-Ponce M.T., Casas L., Mantell C., Pereyra C., Martínez de la Ossa E. Generation of potent antioxidant nanoparticles from mango leaves by supercritical antisolvent extraction. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;138:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaisberg A.J., Milla M., Planas M.C., Cordova J.L., de Agusti E.R., Ferreyra R., Mustiga M.C., Carlin L., Hammond G.B. Taspine is the cicatrizant principle in Sangre de Grado extracted from Croton lechleri. Planta Med. 1989;55:140–143. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palanisamy G. Corrosion Inhibitors. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2019. Corrosion Inhibitors. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fateh A., Aliofkhazraei M., Rezvanian A.R. Review of corrosive environments for copper and its corrosion inhibitors. Arab. J. Chem. 2020;13:481–544. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldino L., Della Porta G., Osseo L.S., Reverchon E., Adami R. Concentrated oleuropein powder from olive leaves using alcoholic extraction and supercritical CO2 assisted extraction. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;133:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J., Huang Y., Liu D., Gao Y., Qian S. Preparation of apigenin nanocrystals using supercritical antisolvent process for dissolution and bioavailability enhancement. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;48:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng Y., Sun J., Wang F., Sui Y., She Z., Zhai W. Effect of particle size on solubility, dissolution rate, and oral bioavailability: Evaluation using coenzyme Q10 as naked nanocrystals. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012;7:5733–5744. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang S.-J., Kim M.-S., Kim J.-S., Park H.J., Cho W.K., Cha K.-H. Enhanced bioavailability of sirolimus via preparation of solid dispersion nanoparticles using a supercritical antisolvent process. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:2997–3009. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quraishi M.A., Chauhan D.S., Saji V.S. Heterocyclic biomolecules as green corrosion inhibitors. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;341:117265. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jüttner K. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of corrosion processes on inhomogeneous surfaces. Electrochim. Acta. 1990;35:1501–1508. doi: 10.1016/0013-4686(90)80004-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang L., Tian J., Meng J., Zhao R., Li C., Ma J., Jin T. Modification and Characterization of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Use in Adsorption of Alkaloids. Molecules. 2018;23:562. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh P., Srivastava V., Quraishi M.A. Novel quinoline derivatives as green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium: Electrochemical, SEM, AFM, and XPS studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;216:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lebrini M., Suedile F., Salvin P., Roos C., Zarrouk A., Jama C., Bentiss F. Bagassa guianensis ethanol extract used as sustainable eco-friendly inhibitor for zinc corrosion in 3% NaCl: Electrochemical and XPS studies. Surf. Interfaces. 2020;20:100588. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang D., Liu S.H., Shao Y.P., Di Xu S., Zhao L.L., Liao Q.Q., Ge H.H. Electrochemical and XPS studies of alkyl imidazoline on the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in citric acid solution. Corros. Rev. 2016;34:295–304. doi: 10.1515/corrrev-2016-0016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan B., Xiang B., Zhang S., Qiang Y., Xu L., Chen S., He J. Papaya leaves extract as a novel eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for Cu in H2SO4 medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;582:918–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polunin A.V., Pchelnikov A.P., Losev V.V., Marshakov I.K. Electrochemical studies of the kinetics and mechanism of brass dezincification. Electrochim. Acta. 1982;27:467–475. doi: 10.1016/0013-4686(82)85025-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burzyńska L. Comparison of the spontaneous and anodic processes during dissolution of brass. Corros. Sci. 2001;43:1053–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0010-938X(00)00130-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou P., Ogle K. Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. The Corrosion of Copper and Copper Alloys; pp. 478–489. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rani B.E.A., Basu B.B.J. Green Inhibitors for Corrosion Protection of Metals and Alloys: An Overview. Int. J. Corros. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2012/380217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu Q.-M., Wang D., Han M.-J., Wan L.-J., Bai C.-L. Direct STM Investigation of Cinchona Alkaloid Adsorption on Cu(111) Langmuir. 2004;20:3006–3010. doi: 10.1021/la034964q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai L., Fu Q., Shi R., Tang Y., Long Y.-T., He X.-P., Jin Y., Liu G., Chen G.-R., Chen K. ‘Pungent’ Copper Surface Resists Acid Corrosion in Strong HCl Solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014;53:64–69. doi: 10.1021/ie402609g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh M.M., Rastogi R.B., Upadhyay B.N. Inhibition of Copper Corrosion in Aqueous Sodium Chloride Solution by Various Forms of the Piperidine Moiety. Corrosion. 1994;50:620–625. doi: 10.5006/1.3293535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H.-J., Zhang W., Wu Y.-C. Alkaloids—Their Importance in Nature and Human Life. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2019. Anti-Corrosive Properties of Alkaloids on Metals. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon request.