Abstract

The filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans reproduces asexually through the formation of spores on a multicellular aerial structure, called a conidiophore. A key regulator of asexual development is the TFIIIA-type zinc finger containing transcriptional activator Bristle (BRLA). Besides BRLA, the transcription factor ABAA, which is located downstream of BRLA in the developmental regulation cascade, is necessary to direct later gene expression during sporulation. We isolated a new developmental mutant and identified a leaky brlA mutation and the mutated Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyclin homologue pclA, both contributing to the developmental phenotype of the mutant. pclA was found to be 10-fold transcriptionally upregulated during conidiation, and a pclA deletion strain was reduced three- to fivefold in production of conidia. Expression of pclA was strongly induced by ectopic expression of brlA or abaA under conidiation-suppressing conditions, indicating a direct role for brlA and abaA in pclA regulation. PCLA is homologous to yeast Pcl cyclins, which interact with the Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase. Although interaction with a PSTAIRE kinase was shown in vivo, PCLA function during sporulation was independent of the A. nidulans Pho85 homologue PHOA. Besides the developmental regulation, pclA expression was cell cycle dependent with peak transcript levels in S phase. Our findings suggest a role for PCLA in mediating cell cycle events during late stages of sporulation.

Asexual sporulation is a widely distributed reproductive mode among fungi. For most species of agricultural or medical importance, spores serve as the means of distribution and infection. The genetic mechanisms of sporulation of Aspergillus nidulans and Neurospora crassa have been studied in detail (2, 16). The life cycle of A. nidulans consists of two developmental phases, a sexual phase and an asexual one, which are both triggered by environmental and endogenous signals. Asexual development begins with the extension of an aerial hypha, the conidiophore stalk, from a specialized thick-walled foot. After apical extension, the stalk tip begins to swell and forms the vesicle, from which two layers of cells are produced by synchronous budding. The first cell generation, called metulae, buds two or three times to produce the second cell generation, the sporogenic phialides. Repeated asymmetric divisions of the phialides lead to long chains of green-pigmented, mitotically derived spores, called conidia. The molecular genetic analysis of asexual sporulation of A. nidulans revealed that several hundred genes are differentially expressed during the formation of the conidiophore (2, 27, 46, 47).

Analysis of aconidial mutants and mutants that develop aberrant conidiophores revealed genetic interactions directing conidiophore formation (3, 12, 27). Initiation of asexual development was shown to be regulated by a group of early genes, termed fluffy genes, due to the cotton-like appearance of mutant colonies (23, 52). Later expression of conidiation-specific genes was shown to be mainly regulated by three developmental genes, brlA, abaA, and wetA. These latter genes were proposed to define a central, linear regulatory pathway responsible for proper temporal and spatial gene expression during conidiophore development and spore maturation (8, 34). brlA encodes a TFIIIA-like zinc finger transcription factor expressed early during conidiophore formation and was shown to be necessary and sufficient for directing sporulation (1). The brlA locus consists of two overlapping transcription units, both essential for normal development, although their products seem to have redundant functions (40). abaA is activated by brlA during the middle stages of conidiophore development. ABAA contains an ATTS DNA binding domain and is, like BRLA, required for transcriptional activation of several sporulation-specific genes (4, 34). abaA induces wetA expression which, in response, stimulates expression of further structural conidiophore-specific genes. In addition to this central, linear regulation pathway, the modifier genes medA and stuA were found to be responsible for the correct spatial and temporal expression of brlA (9, 32, 33). While medA function during development is still unknown in detail, stuA was analyzed at the molecular level. It encodes a transcription factor with an APSES DNA-binding motif (15).

In vegetative hyphae of A. nidulans, nuclear division is not necessarily coupled to septation, resulting in filamentous growing, multinucleate cells (13). This is different for all cell types of the conidiophore produced from the vesicle where a complex switch of cell and nuclear division and cell growth occurs. Metulae, phialides, and conidia are uninucleate and of determined size and volume, which requires strict coordination of nuclear division and cytokinesis. Metulae undergo limited mitotic divisions to produce two or three phialides, whereas the phialide nucleus divides up to 100 times to form a chain of conidia. Conidia immediately arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle until they are induced upon germination. At the same time as this dramatic change in the cell cycle, a switch from filamentous to a pseudohyphal, budding-like growth pattern occurs.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the passage through the Start cell cycle checkpoint leads to morphological changes in the yeast cell that permit polarized growth towards the budding daughter cell. The cell cycle checkpoint which monitors morphogenesis was found to be regulated through the master cell cycle regulator, the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) Cdc28 (Cdc2 homologue) (25). Another nonessential CDK, the Pho85 kinase, also appears to be involved in the regulation of morphogenesis. Pho85 has emerged as an important model for the role of CDKs in processes beyond cell cycle control, as it is involved in the regulation of a broad spectrum of cellular processes (reviewed in reference 5) including metabolism, morphogenesis, and transcriptional regulation. The pleiotropic nature of Pho85 function has been ascribed to its association with multiple cyclin partners, of which 10 are known so far. A yeast strain lacking the entire Pcl1/Pcl2 subfamily of Pho85 cyclins displays strong morphological defects such as elongated buds, random budding in diploids, and delocalized actin patches (24, 31, 45). The main regulator of the cell cycle in A. nidulans is the Cdc2 homologue NIMXcdc2, which is required throughout the cell cycle (38). As in most eukaryotic cells, NIMXcdc2 is associated with the B-type cyclin NIMEcyclinB, which mediates NIMXcdc2 activity (38). Thus far, NIME was the only known cyclin in A. nidulans. In addition to Cdc2-cyclin B activity, the β-casein kinase NIMA is also required for entry into mitosis (37, 58). NIMA is necessary for the nuclear localization of NIMXcdc2-NIMEcyclinB complex and was found to induce chromatin condensation, most likely by phosphorylation of histone H3 (14, 53, 58). There is a second CDK known in A. nidulans (PHOA) which is homologous to the yeast Pho85 kinase and was shown to control developmental responses to phosphorus-limited growth (10) but appears not to be directly involved in cell cycle regulation or morphogenesis.

Several experimental findings suggest the coupling of cell cycle requirements to the specific morphological requirements of developmental cell types in A. nidulans. It was shown that the central regulator of asexual sporulation in A. nidulans BRLA activates cell cycle gene expression, such as that of nimE and nimX (57). Furthermore, a specific nimX mutation, which makes NIMX resistant to negative regulation by tyrosine phosphorylation, was found to display a strong defect in conidiophore morphogenesis, although the strain was not impaired in cell cycle progression (55–57). The mutant produced septated conidiophore stalks in contrast to the unseptated wild-type conidiophore stalks and was impaired in the development of the correct cell types of the conidiophore (57).

Here, we describe the isolation and characterization of a second cyclin gene of A. nidulans, named pclA, which is specifically required for conidiation, suggesting a CDK-PCLA kinase function during sporulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids and culture conditions.

Supplemented minimal and complete media for A. nidulans were prepared as previously described, and standard strain construction procedures were used (19). A list of A. nidulans strains used in this study is given in Table 1. Standard laboratory Escherichia coli strains (XL-1 Blue and Top 10 F′) were used. Plasmids and cosmids are listed in Table 2. To synchronously induce differentiation of conidiophores, a thin mat of mycelia was filtered from liquid culture and placed upon an agar plate. For temperature-sensitive mutant strains, 42°C was considered the restrictive temperature. For the isolation of cell cycle phase-specific RNA, the wild-type strain FGSC26 was blocked at the beginning of S phase by incubation in the presence of 90 mM hydroxyurea for 4 h, which completely blocks nuclear division (7). A nimA5- and a bimE7-carrying strain were grown for 8 h at a permissive temperature and then blocked at late G2 (nimA5) and M phase (bimE7), respectively, through a shift to restrictive temperature for 3 h. Conidium production was determined with confluent plate cultures. A total of 106 conidia of a fresh spore solution that had been washed three times in 0.85% NaCl–0.02% Tween 20 solution were inoculated with 4 ml of medium containing 0.6% agar and poured onto a 1.5% agar plate. After incubation at 37°C, the top layer was excised with the end of a disposable 1-ml pipette tip (diameter, 0.8 cm) and transferred to 0.5 ml of NaCl-Tween solution. Probes were homogenized with a 5-ml homogenizer (B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany), and appropriate dilutions were counted with a hematocytometer.

TABLE 1.

Strains of A. nidulans used in this study

| Strain (mutant) | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| FGSC26 | biA1; veA1 | FGSC |

| GR5 | pyrG89; wA3; pyroA4; veA1 | G. May, Houston, Tex. |

| RMSO11 | pabaA1 yA2; ΔargB::trpC ΔB; trpC801 veA1 | 43 |

| SRF200 | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; veA1 | 21 |

| SSNI2 (9/28) | pyrG89; wA3; pyroA4; brlA43 veA1, transformed with pRG1 | This study |

| SSNI10 (9/28-D) | wA3; ΔargB::trpC ΔB; pyroA4; brlA43::pclA veA1 | RMSO11 × SSNI2 |

| SSNI13 | wA3; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; brlA43::pclA veA1, transformed with pDC1 (argB) and pSNI26 (pclA) | This study |

| SSNI23 | wA3; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; brlA43::pclA veA1, transformed with pDC1 (argB) and pTA111 (brlA) | This study |

| RSH94.4 | methG; ΔbrlA veA1 | 51 |

| SSNI29 | methG; ΔbrlA veA1, transformed with pSNI40 (brlA43) | This study |

| SSNI30 | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; ΔpclA::argB veA1 | This study |

| SWTA | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; veA1, transformed with pDC1 (argB) | This study |

| SSNI37 | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; ΔpclA::argB veA1, transformed with pSNI67 (pclA) | This study |

| SSNI39 (9/28β) | pyrG89; wA3; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; brlA43::pclA veA1 | SSNI10 × GR5 |

| PhoΔ17 | pyrG89; wA3 phoA1; pyroA4; veA1 | 10 |

| HB9 | pyrG89; phoA1; pyroA4 | 10 |

| 9/28Δpho1 | pyrG89; wA3 phoA1; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; brlA43::pclA veA1 | SSNI39 × PhoΔ17 |

| SSNI44 | pyrG89; phoA1; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; ΔpclA::argB veA1 | SSNI30 × HB9 |

| SSNI56 | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; veA1, transformed with pSNI99 (alcA::pclA-HA) | This study |

| SSNI57 | pyrG89; ΔargB::trpCΔB; pyroA4; veA1, transformed with pSNI99 (alcA::pclA-HA) | This study |

| SO12 | yA2; wA3; nimA5; chaA1 riboB2 veA1 | J. Doonan, Norwich, United Kingdom |

| JG100 | yA2 pabaA1; methG1; bimE7; veA1 | J. Doonan, Norwich, United Kingdom |

| TTA292 | biA1; alcA(p)::brlA; methG1; veA1 | 1 |

| TPM1 | biA1; alcA(p)::abaA; methG1; veA1 | 34 |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Cosmid or plasmid | Construction | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript KS(−) | Cloning vector | Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany |

| pUC18 | Cloning vector | MBI Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany |

| pCR2.1-TOPO | TA-cloning vector for cloning of PCR fragments | Invitrogen, NV Leek, The Netherlands |

| pDC1 | A. nidulans argB gene in pIC20R | 6 |

| pRG1 | Plasmid containing the pyr4 gene from N. crassa | 50 |

| W23F08 | pclA-containing cosmid | FGSC |

| pSNI26 | 3.1-kb SmaI/EcoRV pclA-containing fragment in pUC18 cloning vector | This study |

| r5d06a1 | cDNA clone containing pclA | FGSC |

| pSNI38 | 2.7-kb XbaI fragment from genomic DNA of SSNI10 in pUC18 cloning vector containing the brlA43 gene | This study |

| pTA111 | 4.5-kb fragment of brlA genomic region | T. H. Adams |

| pSNI40 | brlA43 allele downstream of 2 kb of the natural promoter of brlA | This study |

| pSNI67 | 3.1-kb SmaI/HindIII pclA-containing fragment from pSNI26 and pyr4 gene in pBluescript KS(−) cloning vector | This study |

| pSNI35 | pclA deletion construct; 685 bp of the pclA coding region was replaced by the argB gene | This study |

| GTEP1 | 3xHA-containing plasmid in pBluescript KS(−) | A. P. Mitchell, New York, N.Y. |

| pSNI39 | 3.4-kb EcoRI pclA-containing fragment from W23F08 cloned behind the alcA promoter and the argB gene cloned into the NotI site of pBluescript KS(−) | This study |

| pSNI99 | 3xHA in Eco47III site of pclA (pSNI39) | This study |

Molecular techniques.

Standard DNA transformation procedures were used for A. nidulans (59) and E. coli (41). For PCR experiments, standard protocols were applied by using a Capillary Rapid Cycler (Idaho Technology, Idaho Falls, Idaho) for the reaction cycles. The 9/28 mutant (strain SSNI2) was isolated as a conidiation-deficient strain derived from a restriction enzyme-mediated DNA integration (REMI) mutagenesis experiment with the strain GR5. Mutagenesis was performed as described earlier (21). To clone pclA by complementation of the sporulation defect, SSNI2 was crossed to RMSO11, and an arginine auxotrophic strain was selected from the progeny. This strain, SSNI10, was cotransformed with an ordered chromosome VIII-specific A. nidulans genomic library (kindly provided by R. Prade and J. Arnold, Athens, Ga.) (54) together with the argB-containing plasmid pDC1 for selection. For identification of the pclA-containing cosmid W23F08, subclasses of the library cosmids were pooled and subsequently tested for complementation of the sporulation defect. A 3.1-kb SmaI/EcoRV fragment was obtained by subcloning the W23F08 cosmid and testing different subclones for complementation. DNA sequencing was performed with the automatic sequencer ALFexpress (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and Cy5-labeled primers or by a commercial sequencing company (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Genomic DNA was extracted from the fungus with the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was isolated with TRIzol according to the manufacturer's protocol (GibcoBRL Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom). DNA and RNA analyses (Southern and Northern hybridizations) were performed as described in reference 41.

Protein extracts, IP, and Western blotting.

Overnight cultures of Aspergillus cells were harvested by being filtered through Miracloth (Calbiochem-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), dried by being pressed between paper towels, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. After being extensively ground in liquid nitrogen, cells were resuspended in protein extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.05% Triton X-100) supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Roche), 5 mM benzamidine, and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Protein extracts were clarified twice by centrifugation in a Heraeus Biofuge 13 at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. For immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments, 10 mg of protein was adjusted to 150 mM NaCl and incubated with 10 μl (5 to 7 μg/μl) of monoclonal antibody HA.11 (clone 16B12; Berkeley Antibody Co., Richmond, Calif.) for at least 2 h at 4°C. Fifty microliters of 50% protein G-agarose (Roche) was added, and incubation was continued for at least 3 h. Agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed five times with protein extraction buffer. Proteins were eluted by being boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer for 5 min. Aliquots were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis. For Western blot analysis, a monoclonal antibody raised against the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (16B12; see above) or a polyclonal antibody raised against a PSTAIRE-containing synthetic peptide (Anti-PSTAIR; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) was used. Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) was used for Western blotting, and antibody detection was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Electron microscopy.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), colonies grown on plates were transferred with a piece of agar onto 5% glutaraldehyde for fixation. After several washes with water, the pieces were transferred to ethylene glycol-monoethyl ether and incubated overnight at room temperature. They were then transferred to water-free acetone and critical point dried. The samples were then sputter coated with gold and observed with a Hitachi S-530 SEM.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of a new developmental mutant.

A. nidulans transformants derived from a REMI mutagenesis experiment with SmaI as a restriction enzyme were screened for strains with abnormal conidiophore morphology. One of these mutants (9/28), which appears as red-brownish colonies due to the lack of colored conidiospores (Fig. 1, upper panels), was colony purified and crossed to a wild-type strain. Since a forced heterokaryon conidiated like the wild type, the mutation appeared to be recessive. Analysis of progeny colonies derived from the sexual cross revealed a ratio of 1:1 of conidiating to nonconidiating colonies. This suggested that the defect is due to a single mutated locus. Southern blot analysis of several mutant progenies revealed that the integration of the plasmid used for transformation was not linked to the mutant phenotype (data not shown).

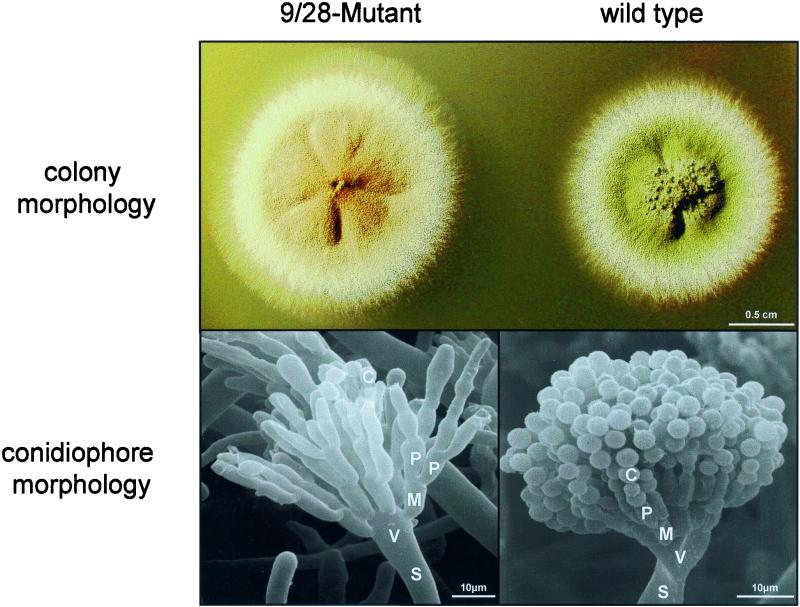

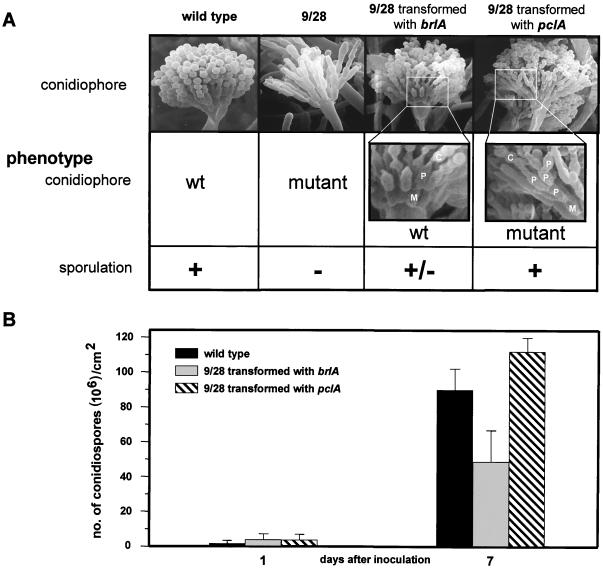

FIG. 1.

Phenotype of the 9/28 mutant. (Top) A 9/28 mutant (SSNI2) and a wild-type strain (FGSC26) were grown for 2 days on an agar plate. (Bottom) SEM picture of a 9/28 mutant and a wild-type conidiophore. S, stalk; V, vesicle; M, metula; P, phialide; C, conidium. The wild-type conidiophore picture is reprinted from reference 21 with permission.

The mutation did not affect vegetative growth, hyphal morphology, or branching, and the mutant was able to produce viable ascospores after self-mating as well as after crosses with different strains. The timing of initiation of asexual sporulation and the number of conidiophores were not altered in the mutant compared to the wild type. However, the mutant fails to produce chains of conidiospores and displays abnormal conidiophore morphology (Fig. 1, lower panels). The swollen vesicle at the end of the stalk produces the first cell generation of the conidiophore, the metulae. These cells are of determined size and volume and appear to be correctly developed in the mutant. In contrast to the wild type, however, the mutant fails to produce the layer of sporogenic phialides but develops multiple generations of phialides instead. Occasionally, single spores are observed at the tip of these cells. Sometimes the cells derived from the metulae are hypha-like elongated structures or resemble reiterated conidiophore stalks (Fig. 1). The phenotype resembles in some way the abacus mutant, but a cross of a 9/28 mutant and an abaA mutant strain revealed that a different gene was affected in the 9/28 mutant. In this paper, we show that the 9/28 mutant has a composite phenotype due to a tightly linked double mutation. Through recombination during the REMI mutagenesis, the developmental regulator gene brlA was fused to the promoter region of the new identified cyclin homologue pclA (see below). As a result, both genes were mutated and contribute to the 9/28 developmental phenotype.

Molecular cloning of the pclA gene.

Since the mutated locus was not tagged to the integration of the transformation plasmid, we isolated the corresponding gene through complementation with an ordered genomic cosmid library of A. nidulans. A 9/28 mutant strain carrying an argB mutation was constructed (SSNI10) and used as a recipient strain of pooled cosmids from the library cotransformed with the argB-containing plasmid pDC1. Transformants were screened for spore production, which could easily be detected upon examining their colony color. Successive transformation of the mutant strain with subclasses of the cosmid library led to the identification of one cosmid (W23F08), which complemented the sporulation defect of the mutant ectopically. Subcloning of this cosmid revealed a 3.1-kb SmaI/EcoRV fragment, which complemented the sporulation defect of the mutant with high frequency, suggesting that the entire gene was located on this clone (pSNI26) (Fig. 2A). With this fragment as a probe, a 2.2-kb transcript was detected in wild-type RNA (Fig. 2B).

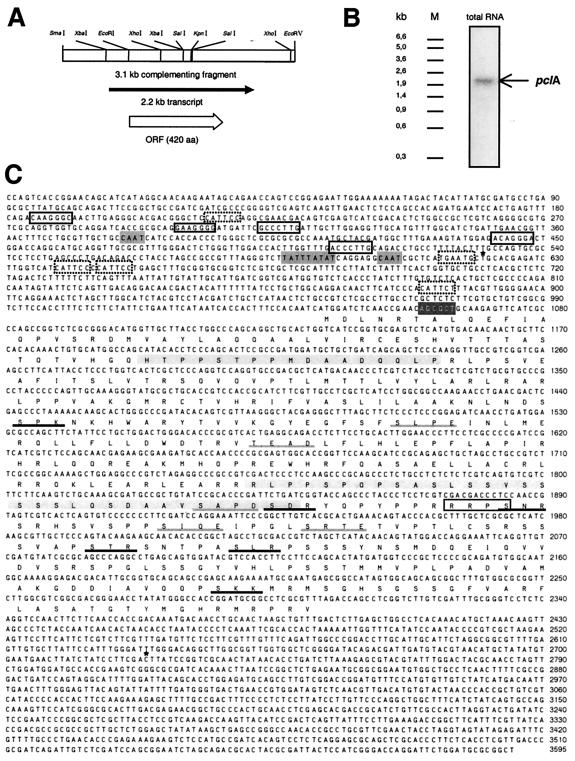

FIG. 2.

Molecular analysis of pclA. (A) Partial restriction map of the pclA locus. The location of the transcript and the ORF is indicated. (B) Detection of the 2.2-kb pclA transcript. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA of the wild-type strain FGSC26 was fractionated by denaturing gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane. The membrane was hybridized with a gene-specific [α-32P]dATP-labeled probe for pclA and exposed to an X-ray film for 2 days. (C) The sequence of the pclA locus was determined with the 3.1-kb complementing restriction fragment shown in panel A or the corresponding pclA cosmid as a template and synthetic oligonucleotides as primer. The coding region was sequenced on both strands. The predicted transcriptional start site (http://www.fruitfly.org) and the end of a cDNA obtained from the Advanced Center for Genome Technology (University of Oklahoma) are marked above the sequence (∗). TATAAA- and CAAT-like boxes in the promoter region are marked in dark grey. Putative binding sites of the transcription factors BRLA (in open boxes) and ABAA (in dotted boxes) are indicated. The derived amino acid sequence of the ORF is given below the sequence in the one-letter code. In the amino acid sequence, the following putative sites are highlighted: PEST sequences (grey), cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation site (open box), protein kinase C phosphorylation sites (black underlined), and casein kinase II phosphorylation sites (grey underlined). The Eco47III restriction site in which the HA epitope was inserted is highlighted with white letters. The sequence is available in the EMBL database under the accession numberAJ272133.

Sequencing of the DNA fragment led to the identification of an open reading frame (ORF) of 420 amino acids (aa), which showed strong homology to yeast cyclins Pcl1, -2, and -9 (Fig. 2C). The Aspergillus gene was therefore named pclA.

Structure of the pclA locus.

The 3.1-kb pclA-containing restriction fragment and 500 bp of the gene locus upstream and downstream of the SmaI and the EcoRV restriction site were sequenced. The pclA coding region was sequenced on both strands. A corresponding cDNA clone was found in the A. nidulans cDNA sequencing project of the Advanced Center for Genome Technology at the University of Oklahoma (www.genome.ou.edu/fungal.html) and kindly provided by the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC) (Kansas City, Kans.). This 2-kb cDNA clone was sequenced on both strands and compared to the genomic sequence. Since no difference was identified, the pclA gene does not contain any intron. The length of the cDNA is in good agreement with the 2.2-kb pclA transcript detected in a Northern blot (Fig. 2B). The transcriptional start site was predicted to be 423 bp upstream of the pclA ORF (http://www.fruitfly.org). Four hundred forty and 663 bp upstream of the ATG two CAAT boxes and 465 bp upstream of the ATG a TATAAA-like box were identified. In addition, we found five putative Bristle response elements and five putative Abacus response elements, which correspond to binding sites for the development-specific transcription factors BRLA and ABAA (Fig. 2C). Sequence motifs were indicated if they did not differ by more than one nucleotide from the consensus sequence as defined in references 4 and 11.

The start of the coding region of pclA could be assigned on the basis of homology of the encoded protein PCLA to yeast cyclins. The ORF encodes a polypeptide of 420 aa with a calculated molecular mass of 47 kDa. A short ORF of 59 aa which may have a role in translational regulation of pclA (26) was detected on the cDNA clone 177 bp upstream of the ATG of the long ORF. Sequence analysis of the deduced PCLA protein led to the identification of several motifs. We found two putative PEST sequences, one cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, and six protein kinase C and five casein kinase II phosphorylation sites (Fig. 2C), suggesting posttranslational modification of PCLA.

Homology of PCLA to yeast Pho85 cyclins.

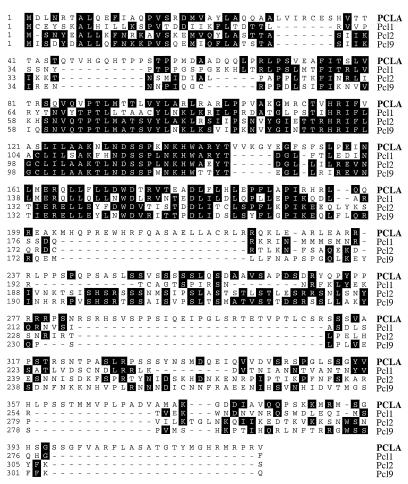

In a search for PCLA sequence similarity in the databases, we found homology to the Pho85 cyclins of S. cerevisiae. Pho85 is a cyclin-dependent kinase, which plays different roles in the life cycle of S. cerevisiae in association with different cyclin subunits. For Pho85-cyclin complexes, roles for regulation of the cell cycle (17, 29, 30), regulation of acid phosphatase expression (20), transcriptional regulation of stress response genes (48), regulation of glycogen metabolism (49), and cell morphogenesis (45) are reported. All 10 cyclin partners of Pho85 were grouped into two subfamilies based on phylogenetic analysis (31). Alignment of PCLA with the Pho85 cyclins revealed that PCLA belongs to the Pcl1/Pcl2 subfamily with the strongest homologies to Pcl1 (31% identity) (Fig. 3). PCLA (420 aa), however, is more than 100 aa longer than its nearest homologues Pcl1, -2, and -9 (279, 308, and 304 aa). The homology was distributed throughout the protein but was most evident in the conserved cyclin box region (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of PCLA with yeast cyclins Pcl1, -2, and -9. The alignment was generated with the Megalign program (DNASTAR) by the Jotun Hein method with a PAM250 weighting table. Amino acids which are identical in at least two proteins are highlighted in black.

pclA partially complements a double mutant.

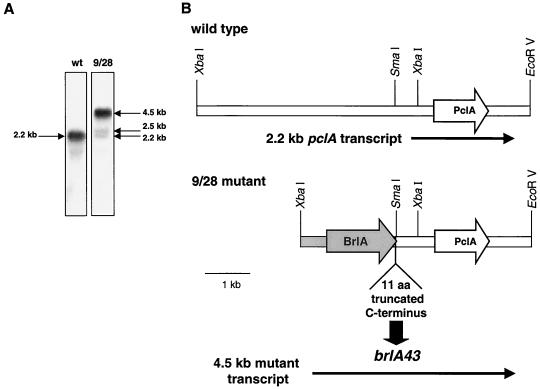

After identification of the pclA gene we tested whether the mutation leading to the developmental defect was located within the pclA gene. Therefore, the pclA gene was PCR amplified and cloned from genomic DNA of a mutant strain. Five of the obtained clones were sequenced and compared to the wild-type pclA gene. Surprisingly, no differences were detected. To further address the nature of the mutation causing the conidiation defect, total RNA of a mutant strain was isolated and analyzed for the mRNA level of the pclA transcript in a Northern blot. In comparison to the 2.2-kb pclA-specific transcript of the wild-type strain, a shift of the transcript to 4.5 kb was observed in the mutant. In addition, two weak signals of 2.2 and 2.5 kb appeared (Fig. 4A). From these results we proposed a mutation in the upstream region of pclA leading to this altered transcript. Therefore, we analyzed the corresponding genomic region by Southern blotting and found that the restriction pattern of the mutant differs from that of the wild type immediately upstream of a SmaI site (data not shown). The 9/28 mutant strain was derived from a REMI mutagenesis experiment where random plasmid integration is favored by the addition of restriction enzyme (in this case, SmaI) during the transformation event (22). As mentioned above, the mutant phenotype of the 9/28 mutant was not linked to the plasmid integration, and the recombination in the pclA promoter region at the SmaI site indicates that this genomic rearrangement is due to the enzymatic activity of SmaI during mutagenesis. The shifted transcript would then be a consequence of transcript initiation of an upstream gene running through the pclA locus. To isolate this gene, we cloned it from genomic DNA of a mutant strain as a 2.7-kb XbaI fragment by colony hybridization, taking the 600-bp SmaI/XbaI fragment of pclA as a probe (Fig. 4B). To our surprise, sequencing of this clone (pSNI38) identified brlA, the central regulator of asexual development, as the upstream gene. Furthermore, we found that the brlA gene was mutated, as 11 aa of the C terminus are replaced in the mutant by 10 aa translated from the pclA upstream region (Fig. 4B). This new brlA allele was named brlA43. Using the brlA gene as a probe in a Northern blot analysis with 9/28 mutant RNA, we found that it hybridized to the same 4.5-kb transcript as the pclA gene (results not shown). When we transformed the mutant strain SSNI10 with a brlA-containing plasmid, we obtained sporulating transformants with high frequency, indicating that the brlA43 allele also contributes to the mutant phenotype. However, when we compared the brlA transformants (SSNI23) with the transformants obtained with the pclA gene (SSNI13), we found that brlA rescued the morphological conidiophore defect of the mutant but only partially rescued the sporulation defect, whereas pclA rescued the sporulation defect but not the morphology defect (Fig. 5). This indicates a composite phenotype of the 9/28 mutant due to a double mutation of the brlA and the pclA genes.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the 9/28 mutation. (A) Fifteen micrograms of total RNA of the wild-type strain FGSC26 and a 9/28 mutant strain isolated 25 h after induction of development was analyzed for the expression of the pclA transcript on a Northern blot as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) Schematic representation of the pclA locus in the wild-type strain FGSC26 (top) and a 9/28 mutant strain (bottom) as analyzed by Southern blotting. The locations of the transcripts and the ORFs are indicated. The new identified brlA mutant allele was named brlA43.

FIG. 5.

Transformation of the 9/28 mutant with brlA or pclA, respectively, only partially complements the mutant phenotypes. The wild-type strain GR5, the mutant strain 9/28-D (SSNI10), and the mutant strain 9/28-D transformed with either the brlA (SSNI23) or the pclA (SSNI13) gene were phenotypically analyzed. (A) Strains were grown for 2 days on agar plates. (Top) SEM image of the corresponding conidiophores. S, stalk; V, vesicle; M, metula; P, phialide; C, conidium. An image of wild-type conidiophores was taken from reference 21 with permission. (B) Strains were inoculated in a top agar layer, and conidium formation was determined after 7 days as described in Materials and Methods. The spore production of the 9/28 mutant could not be determined as it was under the limit of detection in the experimental setup.

To prove this, we separated the two mutations independently from the original mutant. Consequently, we cloned the isolated mutant brlA43 allele downstream of 2 kb of the natural brlA promoter and cotransformed this plasmid (pSNI40) into a brlA deletion strain (RSH 94.4). Whereas the brlA deletion strain only produces stalks, the brlA43 transformants (SSNI29) displayed the 9/28 conidiophore morphology and a reduction of conidiation (data not shown). In contrast, a pclA deletion strain produced conidiophores with wild-type morphology but with a reduced amount of conidiospores (see below).

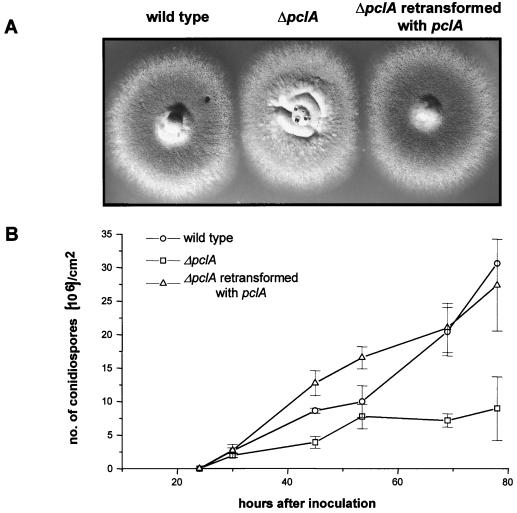

pclA is required for sporulation.

To investigate the role of pclA in A. nidulans in more detail, we replaced 685 bp encoding 227 aa of the pclA gene through the nutritional marker gene argB (Fig. 6A). A pclA+, arginine auxotrophic strain (SRF200) was transformed with the linearized pclA deletion construct to arginine prototrophy. The relatively large flanking regions of the gene locus are necessary to direct the construct to the pclA locus through homologous recombination. Among 10 transformants tested in a Southern blot analysis, 2 contained the deletion construct as predicted according to a gene replacement event (Fig. 6B). The pclA deletion strains (SSNI30) appeared green-brownish compared to a dark-green wild-type strain, indicating a reduced number of green-pigmented conidiospores (Fig. 7A). The deletion did not affect vegetative growth, initiation of sexual and asexual development, or the number of formed conidiophores. Therefore, sporulation was quantified by plating spores in top agar layers, and conidiospore production was subsequently analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Wild-type strain SRF200, which was used to construct the pclA deletion strain (see above), was transformed with pDC1 to arginine prototrophy, and two different transformants were included in the experiment as wild-type controls to eliminate the effects of media on sporulation (SWTA). As an additional control, a pclA deletion strain was retransformed with the entire pclA gene, and two transformants were also included in the experiment (SSNI37). The pclA deletion strain displayed a conidiation rate of about 30% compared to that of wild-type strains 3 days after inoculation (Fig. 7B). Spore formation was not blocked by pclA deletion, as the number of conidia is constantly increasing. Compared to the wild type, however, conidium formation was found to be slowed, and sporulation of the pclA deleted strain never reached wild-type rate. After incubation for 5 days, the number of spores in the deletion strain was less than 20% of that of the wild type (data not shown). As the timing of the formation of the conidiophore-specific cell types was as in wild-type strains, the reduction of spore number in the pclA deletion strain appears to be caused by slower cell divisions of the sporogenic phialides. The pclA-deleted strains which were retransformed with the pclA gene behaved like the wild type, proving that the sporulation defect is specific for pclA deletion (Fig. 7).

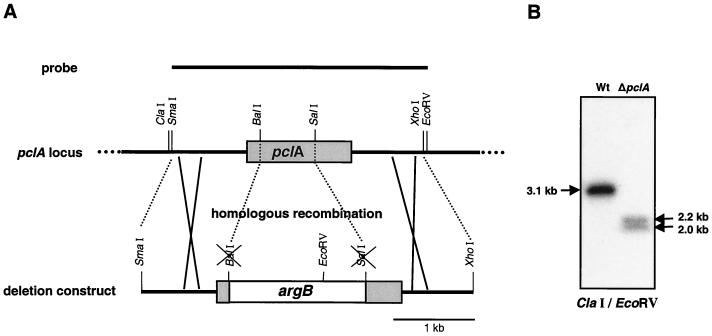

FIG. 6.

Deletion of the pclA gene. (A) Scheme of pclA deletion by homologous recombination. A total of 685 bp between the BalI and the SalI site encoding 227 aa of the pclA gene were replaced through the nutritional marker gene argB in the deletion construct. A wild-type strain (SRF200) was transformed with the linearized pclA deletion construct to arginine prototrophy. The flanking regions of the gene locus are necessary to direct the construct to the pclA locus through homologous recombination. (B) Genomic DNA of the wild-type strain SRF200 and the pclA deletion strain SSNI30 was digested with ClaI and EcoRV and analyzed by Southern blotting for replacement of the pclA gene. The SmaI-EcoRV pclA-containing fragment was taken as a probe.

FIG. 7.

Dependence of asexual sporulation on PCLA. A wild-type strain (SWTA), a pclA deletion strain (SSNI30), and a pclA deletion strain retransformed with the pclA gene (SSNI37) were analyzed for conidium production. (A) Strains were grown for 2 days on agar plates. (B) Conidiospores were inoculated in a top agar layer, and production of conidia was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were taken at the times indicated.

PCLA acts independently of PHOA during sporogenesis.

The yeast cyclin homologues of PCLA interact with the CDK Pho85. The A. nidulans homologue of Pho85, PHOA, was recently shown to mediate developmental decisions to specific environmental conditions like phosphorus concentration, pH, and inoculation density (10). However, when standard laboratory minimal or complete medium with nonlimiting phosphorus concentrations is used, a phoA deletion strain does not display a discernible phenotype. As the pclA deletion strain has a specific phenotype under these conditions (see above), it is unlikely that PCLA interacts with PHOA during sporogenesis. The deletion of a CDK normally displays a more pronounced phenotype than deletion of a single cyclin subunit of a CDK (31). To test that PCLA does not interact with PHOA as a kinase partner during sporogenesis, we constructed a strain carrying the 9/28 mutation and the phoA deletion allele phoA1 by a sexual cross. Progeny strains were isolated and checked for the mutant alleles phenotypically (9/28) and by Southern blot analysis (phoA). The progeny strain 9/28ΔphoA1 carrying the original mutation of the 9/28 mutant and the phoA1 allele was isolated and looked phenotypically like a 9/28 mutant strain. Transformation of this strain with the pclA gene led to complementation of the sporulation defect of the strain, indicating yet again that PCLA acts independently from PHOA during sporogenesis (data not shown). Furthermore, we constructed a strain carrying the pclA and the phoA deletion alleles by crossing the individual mutant strains HB9 (phoA1) and SSNI30 (ΔpclA). The double mutant progeny strains (SSNI44) also displayed the sporulation defect of the pclA deletion strain, demonstrating that the pclA mutation is epistatic over phoA1 (data not shown).

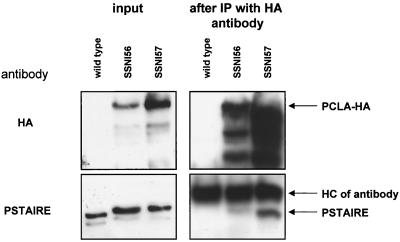

PCLA interacts with a PSTAIRE kinase in vivo.

Because the genetic data presented above suggested that PCLA does not require PHOA for its developmental role, we wanted to test whether PCLA interacts with a CDK in vivo. To allow co-IP experiments, we constructed an HA epitope-tagged version (3xHA) of PCLA by cloning the 111-bp epitope carrying DNA into the Eco47III site of pclA. This restriction site is located at the very N terminus of the encoded protein, outside of the highly conserved cyclin box (see Fig. 2C). To test for functionality of the engineered fusion protein, we transformed a 9/28 mutant strain with the construct and obtained sporulating colonies (data not shown). This demonstrates that the epitope does not interfere with the biological function of the cyclin. However, we were not able to detect the protein in Western blot analyses, probably because the expression level of the protein under the natural promoter is rather low. Therefore we used a construct with the pclA::HA gene under the control of the inducible alcA promoter (pSNI99). Since the alcA promoter is induced by threonine as a carbon source, we grew SRF200 transformants on liquid glucose medium for 14 h, harvested and washed the mycelium, and subsequently incubated it for 4 h in threonine medium. Using protein extracts of these cultures, we detected a specific protein band with a molecular mass of about 55 kDa in a Western blot analysis, which is in good agreement with the predicted mass of 50.6 kDa of the fusion protein (Fig. 8). In addition, several smaller degradation products were visible. Two independent transformants (SSNI56 and SSNI57), which showed different expression levels probably due to different integration numbers of the construct, were used. In protein extracts derived from cultures grown on glucose, no signal was obtained (under repressing conditions; results not shown). The protein extracts of the induced cultures were subjected to a co-IP experiment. Putative CDKs were detected with an anti-PSTAIRE antibody, which recognizes the conserved PSTAIRE peptide motif of this protein family. In crude cell extracts of wild-type cells, the antibody reacted with two prominent bands of 30- to 40-kDa molecular mass. After precipitation of the PCLA protein with the anti-HA antibody, one of the putative CDKs was found in the precipitate (Fig. 8). The protein was not found in a control strain where PCLA was not epitope tagged. This shows that PCLA interacts with a CDK in vivo and functions as a cyclin in A. nidulans.

FIG. 8.

PCLA interacts in vivo with a PSTAIRE-like kinase. Mycelial extracts were prepared from a wild-type strain (SWTA) and two strains containing alcA::pclA-HA (SSNI56 and -57) 4 h after alcA induction by transfer of an overnight culture from repressing medium (glucose) to threonine medium. (Left) One hundred micrograms of total protein was analyzed by Western blotting with either a monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope (top) or a polyclonal antibody against a PSTAIRE-containing peptide (bottom). (Right) Ten milligrams of total protein was subjected to IP with a monoclonal HA antibody. Aliquots of the IP were analyzed by Western blotting with either a monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope or a polyclonal antibody against a PSTAIRE-containing peptide.

pclA transcript regulation is complex throughout the life cycle of A. nidulans

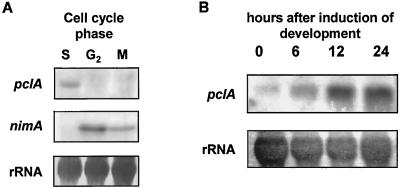

Pho85 cyclin family members Pcl1, -2, -5, and -9, the yeast cyclins most closely related to Aspergillus PCLA, are expressed in a cell cycle-dependent manner (5). To examine pclA gene expression in A. nidulans, total RNA was isolated from strains blocked at different stages of the cell cycle, as described in Materials and Methods. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA of each stage was analyzed by Northern blotting for the mRNA level of pclA. As an internal control, the cell cycle-regulated nimA transcript was taken. In cells blocked in S phase, the nimA transcript was absent, whereas a specific signal was obtained in G2 and a weak signal in M phase-blocked cells (Fig. 9). These findings are consistent with the known transcript regulation of nimA (39). The pclA transcript was detected in cells blocked at the beginning of S phase but was absent in the G2- or M-phase-blocked cells (Fig. 9). This result indicates that pclA is transcriptionally regulated during the cell cycle with a peak in S phase, suggesting a role for pclA during early stages of the cell cycle.

FIG. 9.

pclA transcription regulation is cell cycle and development dependent. (A) Total RNA of the wild-type strain FGSC26 was isolated 3 h after a hydroxyurea-imposed block in S phase. A nimA5- and a bimE7-carrying strain were grown for 8 h at permissive temperature (30°C) and then blocked at late G2 (nimA5) and M (bimE7) phase through a shift to restrictive temperature (42°C) for 3 h. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed for the mRNA level of pclA on a Northern blot as described in Fig. 2. nimA was taken as an internal control. (B) Total RNA of the wild-type strain FGSC26 was isolated at different time points after induction of synchronous asexual development by exposure to an air interphase. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA was analyzed for the mRNA levels of pclA on a Northern blot as described in Fig. 2. To assure equal loading of the lanes, the RNA on membranes was stained with methylene blue before hybridization.

Genes involved in conidiophore formation and sporulation are often regulated at a transcriptional level (28, 43). Since the pclA gene was found to play an important role during conidium formation, we analyzed pclA expression during conidiation. Asexual development was synchronized by transferring a thin mycelial mat filtered from liquid culture to an agar plate (8). This exposure of cells to an air interphase induces development. Total RNA of wild-type strain FGSC26 was isolated at different time points after induction, and total RNA of each stage was analyzed by Northern blotting for the mRNA level of pclA. To quantify the intensity of the signals on X-ray film, we used the computer program ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The experiment with subsequent quantification was repeated three times with 3, 7, and 15 μg of RNA. In all cases, pclA was found to be upregulated at least 10-fold after induction of development, peaking in the late phase of conidiophore development. rRNA was included as an internal control (Fig. 9). The upregulation of pclA during late stages of conidiation correlates well with the sporulation phenotype of the deletion strain. The complex regulation pattern during development and cell cycle suggests a role for pclA in coupling these cellular processes.

Since regulatory proteins potentially cause phenotypes when overexpressed, we tested pclA for this, with the alcA promoter to drive the expression. Spore germination, hyphal morphology, vegetative growth, and production of conidia were not affected by increased levels of pclA (results not shown).

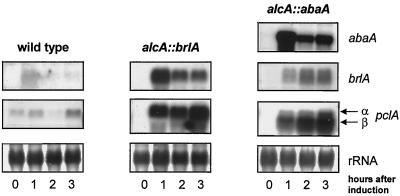

pclA regulation is BRLA and ABAA dependent.

The pclA promoter contains five putative response elements for binding of ABAA and BRLA (Fig. 2C). To elucidate whether these regulators in fact control pclA transcription, we chose a direct approach and analyzed pclA expression under conidiation-suppressing conditions in liquid culture, using strains carrying the brlA or abaA gene under the control of the inducible alcA promoter. Strains were grown overnight in liquid culture on glucose (repressing) medium before transfer to threonine (inducing) medium. At 0, 1, 2, and 3 h after induction of the alcA promoter, samples were taken and analyzed in Northern blot experiments after RNA isolation. As pclA transcript is only hardly detectable in vegetative cells, an increase of pclA expression after artificial induction of the transcription factors fused to the alcA promoter should be readily identifiable. The overexpression of the two regulatory genes after induction was controlled by hybridization of a Northern blot with a corresponding gene-specific probe for either brlA or abaA. As expected, brlA and abaA transcripts are absent from vegetative hyphae. Upon transfer to inducing medium, the two regulatory genes were strongly transcribed from the alcA promoter (Fig. 10). To investigate whether induced expression of brlA or abaA in these strains also stimulates pclA transcription, we probed duplicate Northern blots with a pclA-specific probe. We detected a strong increase of pclA transcript after induction of brlA as well as abaA (Fig. 10). However, in contrast to the full-length pclA mRNA (termed pclAα) induced upon brlA expression, we observed the occurrence of a smaller mRNA species of pclA of about 1.7 kb in length (termed pclAβ) upon abaA expression. pclAα mRNA was also detectable but not significantly induced under these conditions, whereas the smaller mRNA was found to be strongly induced (Fig. 10, right). This smaller mRNA species is unlikely a product of RNA degradation, as no such shifts were observed in other blots with the same RNA. As we observed the smaller mRNA species only in this artificial system after overexpression of abaA, it may be due to recognition of a different transcription initiation site caused by extensive binding of ABAA to the pclA promoter. The enhanced expression of pclA is not caused by the medium changes, as pclA transcript increases only slightly in wild-type cells (Fig. 10, left). We think that this increase is due to brlA expression, as we observed a weak brlA induction after the shift of wild-type cells to threonine medium (Fig. 10, left column, top panel). Developmental processes are often induced by nutrient limitation. It was reported that brlA is induced in liquid culture as a response to carbon or nitrogen limitation (42). Adaptation of the cells to the different carbon source in the induction experiments may cause similar responses leading to the weak brlA induction. We also analyzed stuA dependence of pclA transcription, as we found that pclA mRNA amounts persist on a low level in a stuA1 mutant. In a direct approach with an alcA::stuA-containing strain as described above, we could not confirm stuA dependence of pclA transcription (data not shown).

FIG. 10.

Induction of pclA mRNA by ectopic expression of brlA and abaA. Total RNA was isolated from a wild-type strain (FGSC26), a strain containing alcA::brlA (TTA292), and a strain containing alcA::abaA (TPM1) grown on repression medium (glucose) (0 h) and after alcA induction by transfer to threonine medium (1, 2, and 3 h). RNA was analyzed for the mRNA levels of abaA, brlA, and pclA. To assure equal loading of the lanes, the RNA on membranes was stained with methylene blue before hybridization.

Our results indicate that BRLA and ABAA upregulate pclA in collaboration during conidiophore development by directly increasing pclA transcription (Fig. 10).

DISCUSSION

The molecular analysis of asexual development in A. nidulans led to the identification of a complex regulatory system, which is mainly characterized by transcriptional control mechanisms leading to differential expression of structural genes required for conidiophore formation. As the pattern of cell growth, nuclear division, and cytokinesis changes dramatically during elaboration of the different cell types of the conidiophore, it was proposed that some developmental interactions between the cell cycle and the developmental program must exist (35). Recently, it was shown that the main cell cycle regulators NIMXcdc2 and NIMA are upregulated on mRNA and kinase activity levels in a brlA-dependent manner (57). Here, we report the isolation of the cyclin pclA as a new developmental gene required for the fast, repetitive cell divisions of the phialides, which subsequently lead to long conidium chains of the conidiophore. pclA was found to be regulated during the cell cycle and induced through BRLA and ABAA during development. Our data suggest a role for pclA in mediating cell cycle events during developmental cell type formation.

pclA was isolated by partial complementation of a new developmental mutant (9/28), later characterized as a double mutant carrying a new leaky brlA (brlA43) allele fused to the pclA locus. The mutant displays a sporulation defect and an altered conidiophore morphology. With the REMI mutagenesis method, applied for the isolation of the 9/28 mutant, a rearrangement of the genome occurred. Surprisingly, this brought the brlA gene in close proximity to the pclA locus and resulted in a modification of the C terminus of the BRLA protein. A total of 11 aa were replaced through 10 aa. In addition, this mutation caused a readthrough of the brlA transcript and a severe reduction of the original pclA transcript. Instead, in the wild type we identified two genes upstream of pclA with high homology to an endo-β-1,4-glucanase (accession no. AF043595) from A. aculeatus and a C-8 sterol isomerase (Swissprot accession no. Q92254) from N. crassa (results not shown). Two lines of evidence prove that the BRLA modification is the cause for the morphological conidiophore phenotype of the mutant and that the misfunction or nonfunction mutation of the pclA gene due to the fusion transcript causes the sporulation defect of the mutant. (i) Transformation of the mutant with the brlA gene could rescue the morphological conidiophore defect of the mutant, but rescue the sporulation defect only partially. Transformation with the pclA gene restored the sporulation defect but not the morphology defect. (ii) We were able to separate the two mutations and could show that the corresponding single-mutant phenotypes, established independently from the original mutant, add to the 9/28 double-mutant phenotype. First, transformant strains of a brlA deletion strain with the isolated mutant brlA43 allele displayed the conidiophore morphology of the 9/28 mutant but were reduced in sporulation in comparison to the wild type. Second, deletion of the pclA gene leads to a severe reduction of conidiospore production but not to any other morphological changes of the conidiophore. The isolation of a leaky brlA allele is in agreement with a recent analysis of different null and leaky brlA mutations, where it was shown that the majority of leaky mutations lie in the 3′ half of the gene, possibly in the region that carries the presumptive DNA binding domain (18). Hypomorphic brlA alleles permit more extensive development than null mutants, which only form conidiophore stalks but no more differentiated cells, demonstrating the complexity and the central importance of brlA in the regulation of sporulation.

We showed that pclA is required during sporogenesis by the phialides as a pclA deletion strain displays a strong reduction of conidium production. Initiation of development and of all cell types of the conidiophore was not delayed. Spore germination, hyphal morphology, sexual development, or vegetative growth was not affected by pclA deletion, suggesting that pclA is a new development-specific gene. pclA expression was upregulated late during conidiophore formation, which correlates well with the late developmental phenotype of the pclA deletion strain. We could induce inappropriate expression of pclA by overexpression of the central developmental regulators brlA and abaA in liquid culture. Since BRLA activates abaA and ABAA also induces brlA transcription, it could be that the activation of pclA is only dependent on one of the transcription factors. However, we believe that both, BRLA and ABAA, contribute to the induction because BRLA overexpression led to an increase of exclusively pclAα and ABAA led to a strong induction of pclAβ and only a weak induction of the α transcript. This makes pclA a class A gene as defined in reference 34. Class A genes are regulated by either BRLA or ABAA or both. There are other class A genes known which share with pclA not only the expression pattern but also a function late in development, during spore formation. The conidial laccase YA is involved in spore pigment synthesis and the hydrophobine RODA is important for the hydrophobicity of conidia (for a review, see reference 2).

Time course sporulation analysis showed that the speed of spore formation was reduced in a pclA-deleted strain compared to the wild type, and even longer incubation of the deletion strain did not result in the same number of spores as in wild-type strains. As mentioned above, this delay was not due to inappropriate initiation of conidiophore formation nor to later differentiation of the conidiophore-specific cell generations, the metulae or phialides, and therefore suggests a slower cell division of the sporogenic phialides leading to this phenotype. All cells of the A. nidulans conidiophore derived from the vesicle are uninucleate and are produced in a budding-like fashion, in contrast to the multinucleate, filamentous, vegetative cells. This requires a strict coupling of nuclear division and cell septation and might also be accompanied by an increase of the speed of the cell cycle, given that in a short time up to 100 conidiospores are produced from one phialide. Therefore, pclA could be responsible for adaptation of the cell cycle to the fast, repetitive spore formation by the phialides. This likely cell cycle function for pclA during development is supported by the expression pattern of pclA mRNA in undifferentiated cells. We observed a pclA transcript concentration peak in S phase, suggesting a role for pclA during early stages of the cell cycle. As no function of pclA in vegetative cells could be detected, we think that pclA has a role in linking the cell cycle particularly to development during the elaboration of the conidia.

We found that PCLA interacts with a PSTAIRE-like kinase in vivo. Since the yeast PCLA homologues interact with Pho85, it seemed likely that PCLA activates PHOA (Pho85) in A. nidulans. PHOA was shown to be required for linking developmental decisions to environmental conditions like pH and phosphorus concentration (10). We could, however, exclude PHOA as a partner for PCLA during sporulation, as a phoA-deleted strain did not display the developmental phenotype of a pclA deletion strain, suggesting another interacting kinase for PCLA during development. One partner could be a second phoA/PHO85-related gene in A. nidulans, which Bussink and Osmani proposed existed (10). Furthermore, the experimental finding that the main cell cycle CDK nimXcdc2 is developmentally regulated in a brlA-dependent manner suggests the possibility that PCLA interacts with this kinase. In fission yeast the PCL-like cyclin PAS1+ was shown to interact with a Pho85- and a Cdc2-like kinase in vivo; nevertheless, a cellular function could before now only be assigned to Pas1p associated with the Pho85-like kinase Pef1, which appears to be responsible for the activation of G1-S-specific gene transcription (44).

Besides a function of pclA in the regulation of cell cycle events, other roles for pclA might also be discussed. Recent analysis of S. cerevisiae revealed that Pho85-cyclin complexes (Pcl2 and Pho80) phosphorylate the cell cycle transcription factor Swi5 in vitro (29), suggesting a role for Pho85-cyclin kinase in regulating Swi5 activity. Furthermore, there is experimental evidence that yeast Pcl cyclins link cell cycle decision of the cell to morphogenetic events, probably by modifying the actin cytoskeleton. Pho85-Pcl2 kinase was recently shown to phosphorylate Rvs167p in vitro, which is involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton (24). In addition, a diploid strain lacking the entire Pcl1/Pcl2 subfamily displays morphological defects, such as elongated buds, connected chains of cells, and random budding (31, 45). This resembles the formation of the cell types of the conidiophore, which is thought to be a budding-like process. Whether a CDK-PCLA kinase complex regulates transcriptional activation or directs cytoskeletal components specifically required during spore elaboration, however, remains to be elucidated.

So far, only the B-type cyclin NIME and PCLA, described in this paper, were identified experimentally in A. nidulans and sequence comparison of yet over 6,000 expressed sequence tags (www.genome.ou.edu/fungal.html) did not reveal the existence of additional cyclins. In contrast to S. cerevisiae, where different cyclin subunits associated with the Pho85 or Cdc28 kinase specify its function and activity, the regulation of CDK activities may be different in A. nidulans. Whether Aspergillus cyclins are able to bind to more than one CDK, which was reported for the novel PCL-like cyclin PAS1+ in fission yeast (44) and is known for several cyclins in higher eukaryotes (for a review, see reference 36), and by this means provide the different cellular functions for CDK-cyclin complexes will therefore be of high interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. A. Osmani (Danville, Pa.), A. J. Clutterbuck (Glasgow, United Kingdom), B. L. Miller (Moscow, Idaho), and T. H. Adams (Mystic, Conn.) for providing us with different A. nidulans mutant strains. We are grateful to A. Hassel and G. Kost (Marburg, Germany) for the help with the scanning electron microscope and thank H. D. Ulrich, M. Bölker, N. Requena, and M. Scherer for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grant SFB 395 and the DFG. N.S. holds a fellowship from Schering AG.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams T H, Boylan M T, Timberlake W E. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell. 1988;54:353–362. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams T H, Wieser J K, Yu J H. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:35–54. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.35-54.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams T H, Yu J H. Coordinate control of secondary metabolite production and asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:674–677. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adrianopoulos A, Timberlake W E. The Aspergillus nidulans abaA gene encodes a transcriptional activator that acts as a genetic switch to control development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2503–2515. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews B, Measday V. The cyclin family of budding yeast: abundant use of a good idea. Trends Genet. 1998;14:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aramayo R, Adams T H, Timberlake W E. A large cluster of highly expressed genes is dispensable for growth and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 1989;122:65–71. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergen L G, Morris N R. Kinetics of the nuclear division cycle of Aspergillus nidulans. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:155–160. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.1.155-160.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boylan T M, Mirabito P M, Willett C E, Zimmerman C R, Timberlake W E. Isolation and physical characterization of three essential conidiation genes from Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3113–3118. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busby T M, Miller K Y, Miller B L. Suppression and enhancement of the Aspergillus nidulans medusa mutation by altered dosage of the bristle and stunted genes. Genetics. 1996;143:155–163. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bussink H J, Osmani S A. A cyclin-dependent kinase family member (PHOA) is required to link developmental fate to environmental conditions in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1998;17:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y C, Timberlake A J. Identification of Aspergillus brlA response elements (BREs) by genetic selection in yeast. Genetics. 1992;133:29–38. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clutterbuck A J. A mutational analysis of conidial development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 1969;63:317–327. doi: 10.1093/genetics/63.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clutterbuck A J. Synchronous nuclear division and septation in Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;60:133–135. doi: 10.1099/00221287-60-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Souza C P C, Osmani A H, Wu L P, Spotts J L, Osmani S A. Mitotic histone H3 phosphorylation by the NIMA kinase in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell. 2000;102:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutton J R, Johns S, Miller B L. StuAp is a sequence-specific transcription factor that regulates developmental complexity in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1997;16:5710–5721. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebbole D J. Morphogenesis and vegetative differentiation in filamentous fungi. J Genet. 1996;75:361–374. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinoza F H, Ogas J, Herskowitz I, Morgan D O. Cell cycle control by a complex of the cyclin HCS26 (PCL1) and the kinase PHO85. Science. 1994;266:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.7973730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith G W, Stark M S, Clutterbuck A J. Wild-type and mutant alleles of the Aspergillus nidulans developmental regulator gene brlA: correlation of variant sites with protein function. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:892–897. doi: 10.1007/s004380051155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Käfer M. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv Genet. 1977;19:33–131. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaffman A, Herskowitz I, Tjian R, O'Shea E K. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor PHO4 by a cyclin-CDK complex, PHO80-PHO85. Science. 1994;263:1153–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.8108735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karos M, Fischer R. hymA (hypha-like metulae), a new developmental mutant of Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology. 1996;142:3211–3218. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuspa A, Loomis W F. Tagging developmental genes in Dictyostelium by restriction enzyme-mediated integration of plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8803–8807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee B N, Adams T H. Overexpression of flbA, an early regulator of Aspergillus asexual sporulation, leads to activation of brlA and premature initiation of development. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:323–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Colwill K, Aneliunas V, Tennyson C, Moore L, Ho Y E, Andrews B. Interaction of yeast Rvs167 and Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase complexes may link the cell cycle to the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1310–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew D J, Reed S I. A cell cycle checkpoint monitors cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:739–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo Z, Sachs M S. Role of an upstream open reading frame in mediating arginine-specific translational control in Neurospora crassa. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2172–2177. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2172-2177.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinelli S D, Clutterbuck A J. A quantitative survey of conidiation mutants in Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;69:261–268. doi: 10.1099/00221287-69-2-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayorga M E, Timberlake W E. The developmentally regulated Aspergillus nidulans wA gene encodes a polypeptide homologous to polyketide and fatty acid synthases. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:205–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00279362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Measday V, McBride H, Moffat J, Stillman D, Andrews B. Interactions between Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase complexes and the Swi5 transcription factor in budding yeast. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:825–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Measday V, Moore L, Ogas J, Tyers M, Andrews B. The PCL2 (ORFD)-PHO85 cyclin-dependent kinase complex: a cell cycle regulator in yeast. Science. 1994;266:1391–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.7973731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Measday V, Moore L, Retnakaran R, Lee J, Donoviel M, Neiman A M, Andrews B. A family of cyclin-like proteins that interact with the Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1212–1223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller K Y, Toennis T M, Adams T H, Miller B L. Isolation and transcriptional characterization of a morphological modifier: the Aspergillus nidulans stunted (stuA) gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:285–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00259682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller K Y, Wu J, Miller B L. StuA is required for cell pattern formation in Aspergillus. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1770–1782. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirabito P M, Adams T H, Timberlake W E. Interactions of three sequentially expressed genes control temporal and spatial specificity in Aspergillus development. Cell. 1989;57:859–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirabito P M, Osmani S A. Interactions between the developmental program and cell cycle regulation of Aspergillus nidulans. Dev Biol. 1994;5:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan D O. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osmani A H, McGuire S L, Osmani S A. Parallel activation of the NIMA and p34cdc2 cell cycle-regulated protein kinases is required to initiate mitosis in A. nidulans. Cell. 1991;67:283–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osmani A H, van Peij N, Mischke M, O'Connell M J, Osmani S A. A single p34cdc2 protein kinase (encoded by nimXcdc2) is required at G1 and G2 in Aspergillus nidulans. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1519–1528. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osmani S A, May G S, Morris N R. Regulation of the mRNA levels of nimA, a gene required for the G2-M transition in Aspergillus nidulans. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1495–1504. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prade R A, Timberlake W E. The Aspergillus nidulans brlA regulatory locus consists of overlapping transcription units that are individually required for conidiophore development. EMBO J. 1993;12:2439–2447. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skromne I, Sanchez O, Aguirre J. Starvation stress modulates the expression of the Aspergillus nidulans brlA regulatory gene. Microbiology. 1995;141:21–28. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stringer A M, Dean R A, Sewall T C, Timberlake W E. Rodletless, a new Aspergillus developmental mutant induced by directed gene inactivation. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1161–1171. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka K, Okayama H. A pcl-like cyclin activates the Res2p-Cdc10p cell cycle “start” transcriptional factor complex in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2845–2862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tennyson C N, Lee J, Andrews B J. A role for the Pcl9-Pho85 cyclin-cdk complex at the M/G1 boundary in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:69–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timberlake W E. Developmental gene regulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Dev Biol. 1980;78:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Timberlake W E. Molecular genetics of Aspergillus development. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:5–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timblin B K, Bergman L W. Elevated expression of stress response genes resulting from deletion of the PHO85 gene. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:981–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6352004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timblin B K, Tatchell K, Bergman L W. Deletion of the gene encoding the cyclin-dependent protein kinase Pho85 alters glycogen metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;143:57–66. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waring R B, May G S, Morris N R. Characterization of an inducible expression system in Aspergillus nidulans using alcA and tubulin-coding genes. Gene. 1989;79:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wieser J, Adams T H. flbD encodes a Myb-like DNA-binding protein that coordinates initiation of Aspergillus nidulans conidiophore development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:491–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wieser J, Lee B N, Fondon III J, Adams T H. Genetic requirements for initiating asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Genet. 1994;27:62–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00326580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu L, Osmani S A, Mirabito P M. Role for NIMA in the nuclear localization of cyclin B in Aspergillus nidulans. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1575–1587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong M, Chen H J, Prade R A, Wang Y, Griffith J, Timberlake W E, Arnold J. On the consistency of a physical mapping method to reconstruct a chromosome in vitro. Genetics. 1996;142:267–284. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ye X S, Fincher R R, Tang A, O'Donnell K, Osmani S A. Two S-phase checkpoint systems, one involving the function of both BIME and Tyr15 phosphorylation of p34cdc2, inhibit NIMA and prevent premature mitosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:3599–3610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye X S, Fincher R R, Tang A, Osmani S A. The G2/M DNA damage checkpoint inhibits mitosis through Tyr15 phosphorylation of p34cdc2 in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1997;16:182–192. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye X S, Lee S L, Wolkow T D, McGuire S L, Hamer J E, Wood G C, Osmani S A. Interaction between developmental and cell cycle regulators is required for morphogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1999;18:6994–7001. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye X S, Xu G, Pu R T, Fincher R R, McGuire S L, Osmani A H, Osmani S A. The NIMA protein kinase is hyperphosphorylated and activated downstream of p34cdc2/cyclin B: coordination of two mitosis promoting kinases. EMBO J. 1995;14:986–994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yelton M M, Hamer J E, Timberlake W E. Transformation of Aspergillus nidulans by using a trpC plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1470–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]