Abstract

The meniscus is a critical component of a healthy knee joint. It is a complex and vital fibrocartilaginous tissue that maintains appropriate biomechanics. Injuries of the meniscus, particularly in the inner region, rarely heal and usually progress into structural breakdown, followed by meniscus deterioration and initiation of osteoarthritis. Conventional therapies range from conservative treatment, to partial meniscectomy and even meniscus transplantation. All the above have high long-term failure rates, with recurrence of symptoms. This communication presents a brief account of in vitro and in vivo studies and describes recent developments in the field of 3D-printed scaffolds for meniscus tissue engineering. Current research in meniscal tissue engineering tries to combine polymeric biomaterials, cell-based therapy, growth factors, and 3D-printed scaffolds to promote the healing of meniscal defects. Today, 3D-printing technology represents a big opportunity in the orthopaedic world to create more specific implants, enabling the rapid production of meniscal scaffolds and changing the way that orthopaedic surgeons plan procedures. In the future, 3D-printed meniscal scaffolds are likely to be available and will also be suitable substitutes in clinical applications, in an attempt to imitate the complexity of the native meniscus.

Keywords: meniscal tissue engineering, meniscal regeneration, 3D printing, scaffold, biomaterials

1. Introduction

The knee is one of the largest and most complex joints in the human body. Every structure in the knee joint is important, while the meniscus represents a bulwark against the destruction of the joint. The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous structure, which is found within the knee joint between the medial and lateral femoral condyles and the tibia (Figure 1) [1]. As a vital part of the joint, it plays a significant role in shock absorption, by distributing evenly the load between the medial and lateral compartment and increases the joint congruity and diffusion of synovial fluid along the articular surfaces during physical activity [1,2]. The knee joint still represents the most common anatomical location of pain seen in primary care or general practice settings [3]. In fact, meniscal injuries are known to be the most frequently encountered and treated injuries in the knee joint and, as a result, their prompt diagnosis and appropriate management are of great importance in orthopaedic practice [1,2,4].

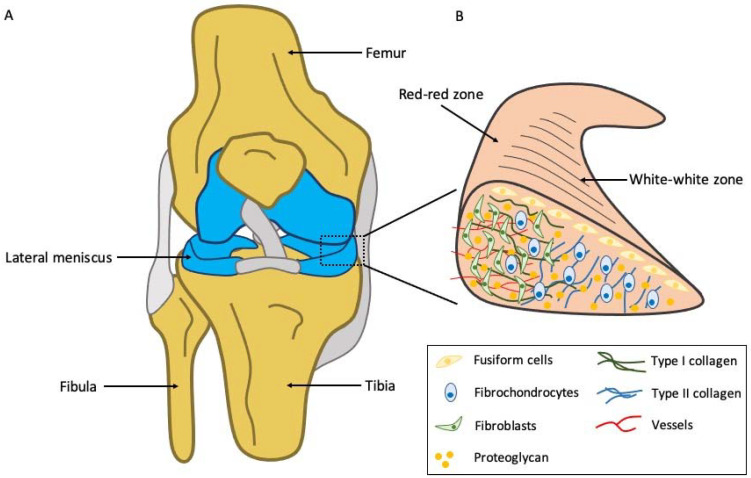

Figure 1.

Basic anatomy of the knee, with the meniscus located within the knee joint between the tibial plateau and the femoral condyles (A), which consists of distinct zones of varying cell populations that are distinct in morphology and phenotype; the inner region contains rounded or oval shaped fibrochondrocytes that produce type II collagen, whereas the outer region is mainly populated by fibroblast-like cells and randomly oriented type I collagen. Aggrecan, which is the major proteoglycan, is organized in a complex architecture and provides the tissue-specific biomechanical characteristics (B).

In this communication, we will mainly focus on the options provided by 3D-printing technology and the combination of different materials, in order to build a 3D construct similar to a native meniscus, giving the opportunity to change the direction of treatment in the near future.

Non-operative management is useful for the initial treatment of meniscal injuries. Anti-inflammatory and analgetic drugs, strengthening exercises of the quadriceps, modifications in activities of daily living, unloader bracing, and intra-articular injections have been shown to improve knee function and reduce joint pain [1]. In the case of failure of non-operative management, there are three main methods for the operative management of meniscal tears (from resection to preservation): (i) arthroscopic total/partial meniscectomy, (ii) meniscal repair, and (iii) meniscal reconstruction (meniscal scaffolds, meniscal allograft transplantation) [1,5,6]. Although, meniscal transplantation is generally utilized as an alternative management option for selected patients, with previous complete or almost-complete meniscectomy, it is a technically demanding and time-consuming procedure. Therefore, it should be performed only after considerable practice and taking into consideration factors related to the patient (skeletally mature, mild unicompartmental degenerative changes, younger than 45 years, normal mechanical axis of the knee joint) [1,7].

2. Principles of Meniscal Substitution

There are three types of meniscus replacement and reconstruction: (i) autografts (tendon, fat or/and perichondral tissue), (ii) allogenic transplants (cadaveric), and (iii) artificial meniscus prostheses [8]. Autografts use a patient’s own tissue, with no immunologic reactions. Recently, surgeons have started using tendon autografts to replace the meniscus, with several advantages: (i) the possibility of replacing the entire meniscus, (ii) availability of any size of meniscus, and (iii) relatively fast patient recovery [8,9,10]. Autografts are intended to stimulate the native cell migration, to promote the remodeling phase, and resulting in the formation of meniscus-like tissue [8]. Meniscal allografts may be considered as a preferred modality for knee joint restoration. However, allografts have many limitations, such as mismatch between donor and recipient (difficulty in obtaining a matching allograft meniscus); the availability of donor tissue in many countries; the technically demanding operation, which can take several hours to perform; its longevity and possibility of disease transmission [8,9]. As a result, three-dimensional (3D)-printed biomaterial constructs offer an effective way to achieve improved biomimetic strategies and have been tested to generate different human tissues, including meniscus [2].

In the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, 3D-printing technology has grown in the last decades, starting from 1986, in order to fabricate customized objects without the need for a mold [11,12]. The first 3D-printing machine was patented by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1994 and become commercially available in 1997 [12]. The application of 3D-printing facilities has shown promising results for quick and cost-effective solutions in different medical fields, such as cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery, urology, dentistry, vascular, and orthopaedic surgery [6,11,13].

The advantages of using 3D-printing technology include the ability to product patient-specific scaffolds with complex shapes, which are capable of homogenous cell distribution, and the ability to imitate the extracellular matrix [14,15,16]. However, it should be noted that they have serious disadvantages, such as the need for specialized equipment, the expensive materials, and the production time needed for scaffolds with a more precise and intricate construction (Table 1) [16,17]. In order to overcome these issues, researchers use natural and synthetic polymers (Table 2), or their combination, as engineered scaffolds and have demonstrated their promising properties for meniscal regeneration [2,9,18].

Table 1.

Summary of the advantages and disadvantages of 3D-printing scaffolds in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

| 3D-Printing Scaffolds for Meniscus Tissue Engineering | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Fabrication of complex structures |

| Use of various types of biomaterials | |

| Easy application of computer-assisted methods | |

| Scaffold design using patient-specific data | |

| Disadvantages | Specialized equipment |

| Expensive materials | |

| Production time (more precise and intricate scaffold) | |

| Highly specific protocols | |

Table 2.

Summary of natural and synthetic polymers for meniscus tissue engineering.

| Polymeric Materials | Types | |

|---|---|---|

| Natural polymers | Proteins | Collagen |

| Silk fibroin | ||

| Gelatin | ||

| Polysaccharides | Hyaluronic acid | |

| Sodium alginate | ||

| Agarose | ||

| Chitosan | ||

| Synthetic polymers | Aliphatic polyesters | Polylactic acid (PLA) |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | ||

| Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) | ||

| Polyglycolic acid (PGA) | ||

| Others | Polyurethane (PU) | |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | ||

| Polycarbonate urethane (PCU) | ||

| Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | ||

| Polyethylene oxide (PEO) | ||

3. Applications of 3D-Printing Scaffolds for Meniscal Tissue Engineering

Considering the field of orthopaedics, it is possible to identify four main application categories of 3D-printing technology: (i) surgical pre-operative planning, (ii) patient-specific implants and orthoses, (iii) personalized instruments and surgical guides, and (iv) biomaterial constructs (tissue-specific scaffolds or/and small tissues) [6,19]. The 3D-printed meniscal scaffolds are a very promising technology, which it is capable of manufacturing patient-specific scaffolds with custom shapes and consistent quality [20]. The development of 3D-printing has provided a new horizon for meniscus repair and regeneration and, as a result, there is a clear need to develop patient-specific implants (Figure 2).

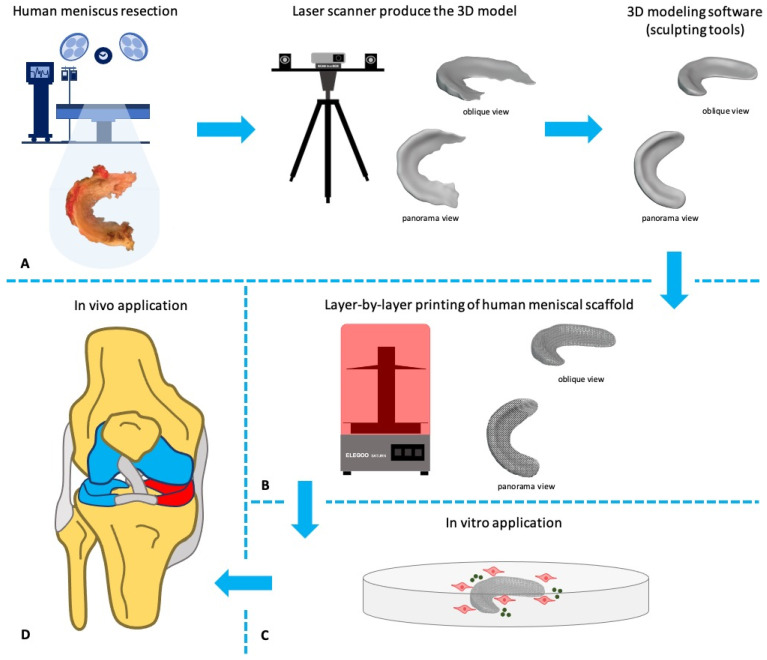

Figure 2.

The cycle of scaffold fabrication and implantation. The anatomic contour of the medial meniscus was obtained from a live human donor, who had undergone total knee replacement, and a custom-made meniscal scaffold was fabricated for a total graft (A), with layer-by-layer deposition of silicone resin using 3D printing technology (B). The meniscal scaffold was bioactivated with primary or stem cells and growth factors, and cultured in a bioreactor, stimulating at least one aspect of the in vivo environment (C). The final step was the meniscal scaffold implantation (D).

A semi-automatic segmentation method was proposed, in order to obtain a 3D model of the meniscus tissue made from polycaprolactone (PCL) with different internal architectures. For this reason, high-quality MRI images were acquired from healthy male volunteer subjects and an advanced segmentation software was used for the fabrication of tissue engineering scaffolds [21]. This 3D model is a vital step in the right direction to the translation of individualized tissue engineering into daily clinical practice, where treatment of meniscal lesions is envisioned. Filardo et al. developed a patient-specific meniscus prototype based on 3D-bioprinting of a human cell-laden scaffold. A 3D model of a bioengineered medial meniscus was created, based on MRI scans of a human volunteer. Primary mesenchymal stem cells were isolated from bone marrow of the iliac crest and used for cell-laden bio-ink preparation. They found that the selected bio-ink presented good printability and shape fidelity, allowing the fabricated tissue to mimic the morphology of the native meniscus [22]. The fabrication of a 3D cell-printed meniscus construct presents great potential as an advanced strategy for the effective repair of the damaged meniscus [18,22]. For example, Chae et al. developed a 3D cell-printed meniscus scaffold using a mixture of synthetic polymers and cell-laden decellularized meniscal extracellular matrix bio-ink [18]. In vivo experiments demonstrated that the 3D cell-printed meniscus scaffolds exhibited biocompatibility and excellent mechanical properties as well as improved biological functionality [18].

PCL is a synthetic, biodegradable polymer that has been widely used in biomedical applications, because of its high biocompatibility and mechanical strength [20,23]. In tissue engineering, a 3D-printing-based biomimetic and composite tissue-engineered meniscus scaffold, consisting of PCL/silk fibroin (SF) was evaluated and demonstrated high biocompatibility and biomechanical properties. This combination of PCL and an SF scaffold augmented by synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells demonstrated excellent structural, biomechanical, and functional properties for meniscus regeneration and chondroprotection [23]. However, using PCL scaffolds in axial tensile tests, would lead to deformation at different rates and may create a break in the structure, which renders it unsuitable for translation applications. In order to overcome this, Gupta et al. developed a composite scaffold, which mimics the mechanical properties of the human meniscus and also presents a self-healing capacity, leading to the repair of microfractures during loading and unloading cycles. They utilized a 3D-printed scaffold and an interpenetrating network (IPN) based on a hydrogel system and achieved retention of functionality of the differentiated chondrocytes within the IPN and formation of the vasculature of the transplanted scaffold [24].

The engineering of human meniscus remains challenging, due to its two district regions: the outer vascularized dense fibrous connective tissue, and the inner completely avascular and aneural fibrocartilage region, with a high proportion of proteoglycans, which are responsible for the viscoelastic compressive and the hydration grade. [7,9,24,25]. Hydrogel-based biomaterials play a pivotal role in meniscal engineering strategies, due to their high water content, which resembles the meniscal tissue, and due to the fact that they can be fabricated under favorable conditions, enabling the encapsulation of cells and labile biomolecules [25]. Hydrogel-based biomaterials have the ability to be seamlessly integrated into water matrices and create a more ‘native’ microenvironment; making them the first choice for 3D bioprinting applications for meniscal repair [26].

While conventional hydrogels are highly biocompatible and widely used for tissue engineering processes, they present certain disadvantages, such as high cost, possible immunogenic responses, and low mechanical resistance; restricting their use in persistent load-bearing applications (i.e., the knee joint) [27]. Therefore, hydrogels can be programmed through simple chemical modification (reduction-oxidation reactions, ions, protonation, and the cleavage of acid–labile chemical bonds) to exhibit optimal properties, such as porosity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, in order to prevent an excessive immune response, while reducing the reliance on immune suppression [28,29]. Moreover, electrospinning is an attractive method for creating nanofibrous scaffolds, in order to reinforce the poor mechanical properties of hydrogels [30].

In more recent studies, different human cell sources have been used in conjunction with electrospun scaffolds and hydrogel, as an attractive combination for generating meniscus-like neotissue [31,32]. In one study, Baek et al. used human cells, which were seeded onto aligned electrospun collagen type I scaffolds and were encapsulated in a tricomponent hydrogel [31]. They found that multilayered constructs composed of electrospun scaffolds, with infrapatellar fat pad cells embedded in a tricomponent hydrogel, produced the most meniscus-like neotissues, with greater deposition of collagen type I, while generating the highest mechanical properties compared to the meniscal, mesenchymal stem, and synovial cells [31]. Romanazzo et al. developed a biomimetic construct that can instruct encapsulated stem cells to differentiate into either meniscal chondrocytes or fibroblasts [32]. They found that an alginate hydrogel functionalized with an extracellular matrix derived from inner and outer region of the meniscus was able to differentiate into either meniscal chondrocytes or fibroblasts. They also exhibited the printability of these functionalized hydrogels, demonstrating that their co-deposition alongside PCL micro-filaments improved the mechanical properties of the 3D bioprinted constructs [32].

Interestingly, Bahcecioglu et al. fabricated a 3D-printed, artificial and anatomically-shaped meniscus scaffold, and subsequently infused it with two different cell-laden hydrogels in the outer and inner part, to imitate the bizonal biochemical composition of the meniscal [33]. In their study, a meniscal construct with total variation was produced by using agarose and gelatin methacrylate hydrogels in the inner and outer region of the 3D-printed PCL scaffolds, and which was cartilage-like and fibrocartilage-like at the inner and outer portion, respectively [33]. This technique has potential for future use as a substitute for total meniscal replacement.

Despite the promising prospects of tissue-engineered scaffolds for meniscus regeneration, there are still many important problems with the use of current materials to build a construct similar to a native meniscus [20,22,23]. The meniscus extracellular matrix (MECM) is usually derived from xenogeneic and allogeneic tissue sources, with a possible negative reaction provoking strong immune and toxicity responses [20]. A possible explanation for this immune response may be the inadequate decellularization of the source tissue. For that reason, Chen et al. combined a MECM-based hydrogel and 3D-printed scaffold to stimulate whole meniscus regeneration [34]. In their study, a hybrid, 3D-printed and wedge-shaped porous PCL scaffold, followed by injection with the optimized MECM-based hydrogel, promoted whole meniscus regeneration in vivo [34]. In a recent in vitro and in vivo study, performed by Sun et al., a ready-to-implant anisotropic meniscus, utilizing a 3D-bioprinting protein releasing a cell-laden hydrogel-PCL composite scaffold, was evaluated by transplanting it into the knee joints of goats [35]. This 3D-bioprinted meniscal scaffold contained mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), cell-laden hydrogel encapsulating PLGA microparticles carrying transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3), or connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in different regions. The in vitro and in vivo evaluation of the meniscus constructs demonstrated resemblance to the native meniscus, as well as long-term chondroprotection of the regenerated meniscus [35].

4. Conclusions

The use of 3D-printing in the orthopaedic field needs to be taken into consideration, in order to change health care. The advent of 3D-printing technology, with new 3D imaging techniques, makes the near future of meniscal scaffolds promising; while personalized 3D meniscal scaffolds are starting to be designed. Today, similarly to any new technology, 3D-printing meniscal scaffolds have introduced many advantages and possibilities to the orthopaedic world, and they provide a big opportunity to help and change the way that orthopaedic surgeons plan their procedures. In particular, hydrogels have been recognized as promising vehicles for tissue engineering and play an important role in 3D bioprinting. Thus, the ideal hydrogel-based scaffolds should provide safety and biocompatibility, be easily manufactured, be flexible in application, and should possess suitable pores for cell adhesion, growth, and proliferation. Despite this progress, the properties of hydrogel-based scaffolds can be more improved by combining different natural or synthetic polymers and using 3D-printing technology to manufacture the meniscus. Finally, legislative regulations and rules must be established, in order to ensure that meniscal scaffolds meet the appropriate criteria and to guarantee their correct use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.V. and N.K.; investigation, A.V.V. and N.K.; data curation, A.V.V., N.K. and K.K.; figures creation, A.V.V.; writing-original draft preparation, A.V.V. and N.K.; writing-review and editing, A.V.V. and K.K.; supervision, N.K. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Doral M.N., Bilge O., Huri G., Turhan E., Verdonk R. Modern treatment of meniscal tears. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:260–268. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jian Z., Zhuang T., Qinyu T., Liqing P., Kun L., Xujiang L., Diaodiao W., Zhen Y., Shuangpeng J., Xiang S., et al. 3D bioprinting of a biomimetic meniscal scaffold for application in tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2021;6:1711–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchis-Alfonso V., Dye S.F. How to Deal With Anterior Knee Pain in the Active Young Patient. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach. 2017;9:346–351. doi: 10.1177/1941738116681269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopf S., Beaufils P., Hirschmann M.T., Rotigliano N., Ollivier M., Pereira H., Verdonk R., Darabos N., Ntagiopoulos P., DeJour D., et al. Management of traumatic meniscus tears: The 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020;28:1177–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-05847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhan K. Meniscal Tears: Current Understanding, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus. 2020;12:e8590. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DePhillipo N.N., LaPrade R.F., Zaffagnini S., Mouton C., Seil R., Beaufils P. The future of meniscus science: International expert consensus. J. Exp. Orthop. 2021;8:24. doi: 10.1186/s40634-021-00345-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rijk P.C. Meniscal allograft transplantation—Part I: Background, results, graft selection and preservation, and surgical considerations. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2004;29:728–743. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(04)00600-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler P.W., Rothrauff B.B., Buerba R.A., Shah N., Zaffagnini S., Alexander P., Musahl V. Meniscal substitution, a developing and long-awaited demand. J. Exp. Orthop. 2020;7:155. doi: 10.1186/s40634-020-00270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y., Chen Y., Wan X., Zhao C., Qiu P., Lin X., Zhang J., Huang Y. Preparation and Characterization of an Optimized Meniscal Extracellular Matrix Scaffold for Meniscus Transplantation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8:779. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milenin O., Strafun S., Sergienko R., Baranov K. Lateral Meniscus Replacement Using Peroneus Longus Tendon Autograft. Arthrosc. Tech. 2020;9:e1163–e1169. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagheri A., Jin J. Photopolymerization in 3D Printing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019;1:593–611. doi: 10.1021/acsapm.8b00165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wendel B., Rietzel D., Kühnlein F., Feulner R., Hülder G., Schmachtenberg E. Additive Processing of Polymers. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2008;293:799–809. doi: 10.1002/mame.200800121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aimar A., Palermo A., Innocenti B. The Role of 3D Printing in Medical Applications: A State of the Art. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. doi: 10.1155/2019/5340616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaszczyńska A., Moczulska-Heljak M., Gradys A., Sajkiewicz P. Advances in 3D Printing for Tissue Engineering. Materials. 2021;14:3149. doi: 10.3390/ma14123149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamay D.G., Usal T.D., Alagoz A.S., Yucel D., Hasirci N., Hasirci V. 3D and 4D Printing of Polymers for Tissue Engineering Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019;7:164. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Placone J.K., Mahadik B., Fisher J.P. Addressing present pitfalls in 3D printing for tissue engineering to enhance future potential. APL Bioeng. 2020;4:010901. doi: 10.1063/1.5127860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Do A.-V., Khorsand B., Geary S.M., Salem A.K. 3D Printing of Scaffolds for Tissue Regeneration Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015;4:1742–1762. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae S., Lee S.-S., Choi Y.-J., Hong D.H., Gao G., Wang J.H., Cho D.-W. 3D cell-printing of biocompatible and functional meniscus constructs using meniscus-derived bioink. Biomaterials. 2021;267:120466. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auricchio F., Marconi S. 3D printing: Clinical applications in orthopaedics and traumatology. EFORT Open Rev. 2016;1:121–127. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H., Liao Z., Yang Z., Gao C., Fu L., Li P., Zhao T., Cao F., Chen W., Yuan Z., et al. 3D printed poly(ε-caprolactone)/meniscus extracellular matrix composite scaffold functionalized with kartogenin-releasing PLGA microspheres for meniscus tissue engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021;9:662381. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.662381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cengiz I., Pitikakis M., Cesario L., Parascandolo P., Vosilla L., Viano G., Oliveira J., Reis R. Building the basis for patient-specific meniscal scaffolds: From human knee MRI to fabrication of 3D printed scaffolds. Bioprinting. 2016;1–2:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2016.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filardo G., Petretta M., Cavallo C., Roseti L., Durante S., Albisinni U., Grigolo B. Patient-specific meniscus prototype based on 3D bioprinting of human cell-laden scaffold. Bone Jt. Res. 2019;8:101–106. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.82.BJR-2018-0134.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z., Wu N., Cheng J., Sun M., Yang P., Zhao F., Zhang J., Duan X., Fu X., Zhang J., et al. Biomechanically, structurally and functionally meticulously tailored polycaprolactone/silk fibroin scaffold for meniscus regeneration. Theranostics. 2020;10:5090–5106. doi: 10.7150/thno.44270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta S., Sharma A., Kumar J.V., Sharma V., Gupta P.K., Verma R.S. Meniscal tissue engineering via 3D printed PLA monolith with carbohydrate based self-healing interpenetrating network hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1358–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rey-Rico A., Cucchiarini M., Madry H. Hydrogels for precision eniscus tissue engineering: A comprehensive review. Connect Tissue Res. 2017;58:317–328. doi: 10.1080/03008207.2016.1276576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J., Xiong J., Wang D., Zhang J., Yang L., Sun S., Liang Y. 3D Bioprinting of Hydrogels for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Gels. 2021;7:144. doi: 10.3390/gels7030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamparelli E.P., Lovecchio J., Ciardulli M.C., Giudice V., Dale T.P., Selleri C., Forsyth N., Giordano E., Maffulli N., Della Porta G. Chondrogenic commitment of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a perfused collagen hydrogel functionalized with hTGF-b1-releasing PLGA microcarrier. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:399. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X., Shou Y., Tay A. Hydrogels for Engineering the Immune System. Adv. Nanobiomed Res. 2021;7:2000073. doi: 10.1002/anbr.202000073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y. Programmable hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2018;178:663–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fazal F., Sanchez F.J.D., Waqas M., Koutsos V., Callanan A., Radacsi N. A modified 3D printer as a hybrid bioprinting-electrospinning system for use in vascular tissue engineering applications. Med. Eng. Phys. 2021;94:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baek J., Sovani S., Choi W., Jin S., Grogan S.P., D’Lima D.D. Meniscal Tissue Engineering Using Aligned Collagen Fibrous Scaffolds: Comparison of Different Human Cell Sources. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2018;24:81–93. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanazzo S., Vedicherla S., Moran C., Kelly D.J. Meniscus ECM-functionalised hydrogels containing infrapatellar fat pad-derived ste cells for bioprinting of regionally defines meniscal tissue. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018;12:1826–1835. doi: 10.1002/term.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahcecioglu G., Hasirci N., Bilgen B., Hasirci V. A 3D printed PCL/hydrogel construct with zone-specific biochemical composition mimicking that of the meniscus. Biofabrication. 2019;11:025002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aaf707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen M., Feng Z., Guo W., Yang D., Gao S., Li Y., Shen S., Yuan Z., Huang B., Zhang Y., et al. PCL-MECM-Based Hydrogel Hybrid Scaffolds and Meniscal Fibrochondrocytes Promote Whole Meniscus Regeneration in a Rabbit Meniscectomy Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:41626–41639. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b13611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Y., You Y., Jiang W., Wu Q., Wang B., Dai K. Generating ready-to-implant anisotropic menisci by 3D-bioprinting protein-releasing cell-laden hydrogel-polymer composite scaffold. Appl. Mater. Today. 2020;18:100469. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2019.100469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.