Abstract

Yra1p is an essential nuclear protein which belongs to the evolutionarily conserved REF (RNA and export factor binding proteins) family of hnRNP-like proteins. Yra1p contributes to mRNA export in vivo and directly interacts with RNA and the shuttling mRNP export receptor Mex67p in vitro. Here we describe a second nonessential Saccharomyces cerevisiae family member, called Yra2p, which is able to complement a YRA1 deletion when overexpressed. Like other REF proteins, Yra1p and Yra2p consist of two highly conserved N- and C-terminal boxes and a central RNP-like RNA-binding domain (RBD). These conserved regions are separated by two more variable regions, N-vr and C-vr. Surprisingly, the deletion of a single conserved box or the deletion of the RBD in Yra1p does not affect viability. Consistently, neither the conserved N and C boxes nor the RBD is required for Mex67p and RNA binding in vitro. Instead, the N-vr and C-vr regions both interact with Mex67p and RNA. We further show that Yra1 deletion mutants which poorly interact with Mex67p in vitro affect the association of Mex67p with mRNP complexes in vivo and are paralleled by poly(A)+ RNA export defects. These observations support the idea that Yra1p promotes mRNA export by facilitating the recruitment of Mex67p to the mRNP.

Newly synthesized precursor RNAs become associated with hnRNP proteins and components of the splicing and 3′-end-processing machinery to undergo a series of well-coordinated processing steps resulting in the formation of export-competent mRNP complexes. As a number of hnRNP proteins remain associated with the mRNA during its translocation through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), they were previously proposed to contain signals recognized by specific mRNA export receptors (8, 11, 25, 43).

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mex67p-Mtr2p heterodimer and its human orthologue TAP-p15 play a central role in mRNA export and represent so far the best-characterized mRNA export receptors (12, 16, 17, 33). Indeed, conditional mutations in Mex67p induce a rapid nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA as well as of specific transcripts, consistent with an essential role in mRNA export (13, 36). The human TAP protein was identified as the cellular factor interacting with the constitutive transport element (CTE) present in RNAs from simple retroviruses (12). Because the injection of CTE RNA into Xenopus oocytes competes with the export of cellular mRNAs, TAP was also described as a component of the normal mRNA export pathway (26, 31). Mex67p and TAP present the main features of mRNA export receptors, or nuclear export factors, since both shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, cross-link to poly(A)+ RNA in vivo, and directly interact with FG-nucleoporins at the NPC (2, 4, 16, 17, 39).

TAP binds the viral CTE very strongly and specifically (5). In contrast, the interaction of TAP and Mex67p with cellular RNAs is nonspecific and of low affinity, suggesting that these export factors associate with poly(A)+ RNA through protein-protein interactions rather than direct binding to RNA (2, 5, 17, 33). Consistently, Yra1p, an hnRNP-like protein which directly interacts with Mex67p, was identified in a genetic screen for mutations synthetically lethal with a MEX67 mutation as well as by affinity purification with tagged Mex67p from yeast extracts (40, 42). Yra1p had initially been purified as a protein with strong RNA-RNA annealing activity, but it is still unclear whether this activity is relevant to Yra1p function in vivo (27). The interaction between Mex67 and Yra1p is direct and occurs in the presence or absence of RNA. Yra1p belongs to an evolutionarily conserved family of hnRNP-like proteins, called REF (RNA and export factor binding proteins), which has more than one member in several species. The REF proteins exhibit nonspecific affinity for RNA, and they are all characterized by a central RNP-motif RNA-binding domain (RBD) and two highly conserved N- and C-terminal boxes (N box and C box). These conserved regions are separated by two more variable domains (N-vr and C-vr) (42). In higher eucaryotes, the variable regions are rich in glycines and asparagines, reminiscent of the RGG domain of certain RNA binding proteins (7). Consistent with a direct role of Yra1p in mRNA export, both Yra1p depletion and analysis of a YRA1 conditional mutant under nonpermissive conditions result in nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA. Mammalian REF proteins interact with TAP, and Aly, one of the mouse REF proteins, also called REF1-I, is able to rescue a YRA1 gene disruption in yeast, indicating that the function of the REF proteins in mRNA export has been conserved (40). For these reasons, REF proteins have been proposed to participate in mRNA export by facilitating the recruitment of Mex67p/TAP to cellular mRNPs (40, 42).

Yra1p was found earlier in a screen for genes causing overexpression-mediated cell growth arrest (9). Similarly, Mlo3, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homologue of Yra1p, was also isolated as a gene causing cell cycle arrest when overexpressed (15). The mouse homologue Aly was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen as a protein interacting with LEF1, a transcription factor regulating the activity of the T-cell receptor alpha enhancer. In that study, Aly was proposed to facilitate the functional collaboration of multiple proteins and their assembly into a complex (6). Aly was also described previously as a chaperone protein regulating the activity of transcription factors containing a leucine zipper (44). These latter data suggest that REF proteins may function at multiple steps in mRNA biogenesis and expression.

In this study, we pursue the functional characterization of Yra1p in mRNA export. We describe a nonessential homologue of Yra1p, Yra2p, which functionally overlaps with Yra1p. The phenotypic and biochemical analyses of Yra1p deletions show that the RBD is dispensable for viability as well as RNA binding and indicate that the C-terminal and N-terminal domains of the protein are functionally overlapping and redundant for both RNA and Mex67p binding. Yra1 mutants compromised in Mex67p binding have parallel defects in poly(A)+ RNA export. As lower amounts of Mex67p are associated with mRNP complexes in these Yra1 mutant strains, the data support the view that Mex67p is recruited to the mRNP through an interaction with Yra1p.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and constructs.

The yeast plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. The Myc-tagged YRA2 gene construct expresses an N-terminally tagged protein and was obtained in two PCR amplification steps. First, 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences (500 bp) were amplified as BamHI-SalI and SalI-BamHI fragments, respectively. The 3′ primer for the 5′ flanking fragment was designed so that the SalI site is preceded by the ATG codon followed by a Myc-tag sequence. The 5′ primer for the 3′ flanking fragment contained a SalI site just upstream of the YRA2 stop codon. The 5′ and 3′ flanking fragments were digested with SalI, ligated, and amplified again with the external 5′ and 3′ primers. The final PCR product was digested with BamHI and cloned into YCpLac22-SalI cut with BamHI from which the unique SalI cloning site had been eliminated; this generated the cassette construct Myc-YRA2 ± 500 (pFS2131). The YRA2 coding sequence was amplified from genomic DNA as a SalI fragment and cloned in frame into the Myc-YRA2 ± 500 cassette linearized with SalI to generate YCpLac22-Myc-YRA2 (pFS2262). For Myc-Yra2p overexpression, the BamHI insert of pFS2262 was subcloned into the high-copy-number plasmid YEpLac112 (TRP1, 2μm) to generate YEpLac112-Myc-YRA2 (pFS2261). The same strategy was used to generate the cassette construct YCpLac22-HA-YRA1 ± 500 (pFS2128) and HA-YRA2 ± 500 (pFS2343). The construct expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Yra2p was obtained by subcloning the YRA2 genomic SalI fragment from pFS2262 into pFS2343 cut with SalI to generate pFS2345. The constructs expressing wild-type HA-YRA1 (pFS2146) or HA-YRA1 truncations (14–227, 1–210, 14–210, 77–227, 1–167, and 14–167; pFS2151, pFS2154, pFS2155, pFS2156, pFS2145, and pFS2148, respectively) were obtained by PCR amplification of the corresponding sequences as SalI fragments on the YRA1 cDNA and cloning into pFS2128 cut with SalI. The HA-ΔRBD construct was obtained by ligating a 5′ BamHI-XhoI PCR fragment containing 500-bp YRA1 5′ flanking sequences and codons 1 to 77 (with the HA tag) to a 3′ XhoI-BamHI fragment containing codons 167 to 227 and 500-bp 3′ flanking sequences. The ligated products were PCR amplified with the BamHI external primers and cloned into YCpLac22 cut with BamHI to generate pFS2268. Construct pHA-YRA1+int (pFS2233) was obtained by cloning the YRA1 genomic coding sequence as a SalI PCR fragment into pFS2128 linearized with SalI.

TABLE 1.

Yeast vectors and plasmids used in this studya

| Code | Name | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pFS1876 | pURA3-YRA1 | YRA1 gene plus intron cloned as a 1.6-kb BamHI PCR fragment into YCpLac33 (URA3/CEN) | 42 |

| pFS2273 | YCpLac22-SalI | TRP1/CEN vector SalI killed | This study |

| pFS2274 | YEpLac112-SalI | TRP1/2μm vector SalI killed | This study |

| pFS2131 | pMyc-YRA2 ± 500 | YCpLac22-SalI with a 1-kb BamHI insert consisting of 500-bp YRA2 5′ flanking sequences, the ATG codon, a Myc tag, a unique SalI site followed by a stop, and 500-bp YRA2 3′ flanking sequences | This study |

| pFS2262 | pMyc-YRA2 | YRA2 coding sequence inserted as a SalI PCR fragment into pFS2131 cut with SalI | This study |

| pFS2261 | pMyc-YRA2 (2μm) | BamHI insert of pFS2262 subcloned into YEpLac 112 cut with BamHI | This study |

| pFS2343 | pHA-YRA2 ± 500 | Same as pFS2131 but with an HA tag | This study |

| pFS2345 | pHA-YRA2 | YRA2 coding sequence inserted as a SalI fragment into pFS2343 cut with SalI | This study |

| pFS2128 | pHA-YRA1 ± 500 | YCpLac22-SalI with a 1-kb BamHI insert consisting of 500-bp YRA1 5′ flanking sequences, the ATG codon, an HA tag, a unique SalI site followed by a stop, and 500-bp YRA 3′ flanking sequences | This study |

| pFS2146 | pHA-YRA1 | Wild-type YRA1 cDNA inserted as a SalI PCR fragment into pFS2128 cut with SalI (TRP1, CEN) | This study |

| pHA-YRA1 mutants | Insertion of HA-YRA1 truncations as SalI PCR fragments into pFS2128 cut with SalI (TRP1, CEN) | This study | |

| pFS2233 | pHA-YRA1+int | YRA1 gene+intron coding sequence cloned as a SalI PCR fragment into pFS2128 cut with SalI | This study |

| pFS2321 | pHA-YRA1 | BamHI insert of pFS2146 subcloned into YCpLac111 (LEU2, CEN); same for YRA1 mutants | This study |

| pPS808 | pGAL1-GFP vector | Vector for expression of galactose-inducible N-terminal GFP fusions URA3/2μm | 20 |

| pPS811 | pGAL-GFP-NPL3 | NPL3 coding sequence cloned in pPS808 | 20 |

| pFS1915 | pGAL-GFP-YRA1 | YRA1 cDNA cloned as a SalI PCR fragment into pPS808 cut with SalI | This study |

| pFS1941 | pGAL-GFP-YRA2 | YRA2 coding sequence cloned as a SalI PCR fragment into pPS808 cut with SalI | This study |

| pGAL-GFP-YRA1 mutants | YRA1 cDNA portions cloned as SalI, XhoI, or SalI/XhoI PCR fragments into pPS808 | This study | |

| pFS1858 | TAP-tag-KANr | ProtA and calmodulin binding domains amplified from the original TAP-tag-TRP1 cassette were inserted as a PacI-AscI fragment into pFA6a-GFP-KANr-MX6 cut with the same enzymes | 29, 22, and this study |

The constructs for the preparation of GST fusions in E. coli are described in Materials and Methods.

The wild-type YRA1 construct in YCpLac22 was transferred to YCpLac111 (LEU2/CEN) by subcloning the BamHI insert to generate pFS2321. The YRA1 mutant constructs were subcloned similarly to generate pFS2322 to pFS2327.

The galactose-inducible green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion constructs were obtained by cloning YRA2 (pFS1941) and the complete YRA1 cDNA coding sequence (pFS1915) or truncations thereof (codons 14 to 227 in pFS2044, 1 to 210 in pFS2043, 14 to 210 in pFS2065, 77 to 227 in pFS2062, 1 to 167 in pFS2041, 14 to 167 in pFS2063, 1 to 77 in pFS1955, 77 to 167 in pFS2061, and 167 to 227 in pFS2064) as SalI PCR fragments into vector pPS808-810 (GAL-GFP, URA3, 2μm) cut with SalI, in frame with the upstream GFP sequence. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion constructs were obtained by cloning the same PCR SalI fragments into pGex4T-1 (YRA2 in pFS2113 and YRA1 codons 14 to 227 in pFS1984, 1 to 210 in pFS1985, 14 to 210 in pFS2115, 77 to 227 in pFS2114, 1 to 167 in pFS1986, 14 to 167 in pFS2116, 1 to 77 in pFS2118, 77 to 167 in pFS2071, and 167 to 227 in pFS2072). The construct coding for wild-type GST-Yra1 has been described previously (42). GST-MEX67 construct pFS1816 was obtained by cloning the coding region as an EcoRI PCR fragment into pGex4T-1.

The TAP-tag-KANr cassette (pFS1858) was obtained by inserting a PCR fragment, containing the protein A (ProtA) and calmodulin binding domains amplified from the original TAP-tag-TRP1 cassette (29), as a PacI-AscI fragment into pFA6a-GFP-KANr-MX6 cut with the same enzymes (22).

Yeast strains.

Yeast strains used in this study are summarized in Table 2. The YRA1 shuffle strain yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1> (FSY1026) in the W303 background (MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3) was described earlier (42). The shuffle strain yra1::HIS3/yra2::KANr <pURA3-YRA1> (FSY1135) was obtained by backcrossing the yra2::KANr Euroscarf deletion strain (BY4742, matα his3Δ1 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 YKL214c::KanMX4; accession no. Y15064) three times with the YRA1 shuffle strain FSY1026. Strains expressing functional Yra1 truncations were obtained by transformation of the YRA1 shuffle strain with wild-type or mutant YCpLac22-HA-YRA1 plasmid followed by selection against the pURA3-YRA1 plasmids on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates. The strains used to prepare extracts for pull-down assays were constructed as follows. The strain expressing Gle2p with a C-terminal HA tag (GLE2-HA, FSY1121) was obtained by genomically tagging GLE2 with an HA epitope through insertion of a DNA cassette at the 3′ end of the gene in a haploid W303 strain using KANr as a selectable marker (22). Strains expressing GFP-tagged Mex67p and Pab1p (MEX67-GFP and PAB1-GFP, FSY1113 and FSY978, respectively) were obtained by chromosomal insertion of a DNA cassette at the 3′ end of the genes using HIS3 as a selectable marker in the W303 wild-type strain for MEX67 and KANr as a selectable marker in the protease-deficient strain BJ2168 for PAB1. Strains expressing GFP-Yra2, GFP-Yra1, GFP-Yra1 deletion mutants, or GFP-Npl3 were obtained by transforming W303 with pGAL-GFP-YRA2 (pFS1941), pGAL-GFP-YRA1 (pFS1915), pGAL-GFP-YRA1 deletion mutants (see above, pPS808 constructs), and pGAL-GFP-NPL3 (20). Cells transformed with these plasmids were grown to mid-log phase in Ura− medium containing 2% glucose, washed, induced for 4 to 5 h in selective medium containing 3% galactose–1% raffinose, and examined under the microscope or processed for extract preparation.

TABLE 2.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| W303 | Wild type | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 | |

| FSY1026 | YRA1 shuffle | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1+int; pFS1876> | 42 |

| FSY1135 | YRA1/ΔYRA2 shuffle | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 yra2::KANryra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1+int; pFS1876> | This study |

| Yra1 mutant strains | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 yra1::HIS3 <pTRP-HA-YRA1 mutant> | This study | |

| FSY1071 | ΔYRA2 (Y15064) | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 ykl214c::KanMX4 | Euroscarf strain BY4742 |

| PSY1042 | pse1-1 Δkap123 | MAT? ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 trpΔ63 pse1-1 kap123::HIS3 | 35 |

| FSY1113 | MEX67-GFP | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 MEX67-GFP-HIS3 | This study |

| FSY1121 | GLE2-HA | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 GLE2-3HA-KANr | This study |

| BJ2168 | Protease deficient | MATaleu2 trp1 ura3-52 pep4-3 pre1-407 prb1-1122 | 1a |

| FSY978 | PAB1-GFP | MATaleu2 trp1 ura3-52 pep4-3 pre1-407 prb1-1122 PAB1-GFP-KANr in BJ2168 | This study |

| FSY1246 | PAB1-TAP-tag/ MEX67-3HA | MATaade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 yra1::HIS3 PAB1-TAP-tag-KANrMEX67-3HA-TRP1 <pURA3-YRA1+int; pFS1876 > | This study |

The strains expressing Pab1-ProtA, Mex67-HA, and wild-type or mutant forms of HA-Yra1 (PAB1-TAP-KANr MEX67-HA-TRP1 yra1::HIS3 <pLEU-YRA1>) were obtained by genomically tagging PAB1 and MEX67, respectively, with a TAP-tag-KANr cassette (pFS1858) and the HA-TRP1 cassette (22, 29) in the YRA1 shuffle strain to generate YFS1246. This strain was transformed with wild-type or mutant HA-YRA1 constructs on YCpLac111 (LEU2/CEN) followed by plasmid shuffling on 5-FOA. Some of the Yra1 mutant proteins (e.g., 1–167, 77–227, and ΔRBD) were expressed at low levels in the Pab1-TAP/Mex67-3HA double-tagged strain, resulting in an enhanced temperature-sensitive phenotype. In these strains, Pab1p contains both a calmodulin binding tag and a ProtA tag fused to its C terminus, but only the ProtA tag was used in the experiments described here.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

Yra1-GST and Yra2-GST fusions, ProtA-Pse1-6xHis, and 6xHis-RanQ69L were expressed in the Escherichia coli M15 pRep4 strain. Cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-HCl [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol) plus 1 tablet of complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics) per 40 ml and lysed with a one-shot cell disrupter (Constant System Ltd.) set to 1.75 × 105 kPa (1.75 kilobars). Cell debris were removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 12,000 × g, and GST fusions were affinity purified on glutathione-agarose beads (Pharmacia) as described by the manufacturer. For the RNA binding assays, Yra1- and Yra2-GST fusions were purified in lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, eluted from beads in 1× phosphate-buffered saline–10 mM glutathione–10% glycerol, and concentrated with a Centricon 30 (Amicon) concentrator. GST-Mex67 was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells. Induction was performed at 16°C for 48 h; cells were lysed in 100 mM KOAc–10 mM HEPES (pH 7)–2 mM MgOAc–10% glycerol and purified as described above. RanQ69L-GTP and ProtA-Pse1-6xHis were prepared as described previously (10).

In vitro binding with recombinant Pse1p.

The E. coli lysate containing ProtA-Pse1-6xHis was adjusted to 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated with different GST fusions immobilized on beads in the presence or absence of 1 mM GTP and ∼10 μg of RanQ69L loaded with GTP (Pharmacia). Each binding reaction mixture contained 200 μl of E. coli lysate and 5 μg of GST fusion in a final volume of 300 μl. Binding reactions were performed for 1 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel; beads were washed three times with 500 μl of lysis buffer plus 0.1% Triton X-100, resuspended in 2× sample buffer, and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Coomassie blue staining or Western blot analysis.

GST pull-down assays with yeast extracts.

Yeast lysates for pull-down assays were prepared from cells grown in selective or yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD) medium at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0. When galactose inductions were needed (extracts expressing GFP-Yra1, GFP-Yra2, and GFP-Npl3), cells were grown overnight in selective medium containing 2% glucose, washed, and induced for 5 h in selective medium containing 3% galactose and 1% raffinose. Cell pellets corresponding to 80 OD600 units of cells were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.6], 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol) containing complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail and lysed with a one-shot cell disrupter set to 2 × 105 kPa (2 kilobars). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min. Extract corresponding to 4 OD600 units of cells (50 μl) was incubated with 5 μg of GST-tagged recombinant protein immobilized on 20 μl of packed glutathione agarose beads in a final volume of 200 μl of lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 90 min at 4°C on a turning wheel. Beads were then washed three times with 300 μl of lysis buffer plus 0.1% Triton X-100, resuspended in 30 μl of 2× sample buffer, boiled, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. RNase-treated extracts were obtained by incubating 100 μl of extract (8 OD600 units of cells) with 15 μg of RNase A for 20 min at 25°C prior to the binding experiment.

Affinity purification of HA-Yra1p and HA-Mex67p with ProtA-Pab1p expressed in yeast.

Strain FSY1246 shuffled with wild-type or mutant YRA1 constructs on LEU2/CEN was grown in YEPD–2% glucose overnight at 30°C to an OD600 of 1. Cells were spun, resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.6], 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor mix) per 100 OD600 units of cells, and lysed by vortexing in the presence of glass beads. RNase A treatment was done as described above. Binding reactions were performed in a final volume of 300 μl containing 150 μl of extract, 50 μl of 50% immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose (Pharmacia), and 150 μl of lysis buffer on a turning wheel for 90 min at 4°C. Beads were washed four times with 400 μl of lysis buffer for 5 min. Bound proteins were eluted from the beads by addition of 200 μl of 2 M KCl–20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, for 15 min at 4°C, followed by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid. The eluted samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-HA and anti-Npl3p antibodies.

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analyses were performed according to standard procedures. The anti-Npl3p and the anti-GFP antibodies, a kind gift of Pam Silver (34), the anti-Gle1p, a kind gift from Laura Davis, and the anti-HA antibody (Roche Diagnostics) were used at a 1:2,000 dilution. The protein signals were revealed with Super Signal West Pico or West Femto Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) whenever stated in the figure legends.

Electrophoretic mobility retardation assay.

An 80-nucleotide RNA probe was prepared by in vitro transcription with T3 RNA polymerase (Promega) using pBluescript KS(+) digested with SmaI as the template. Reactions were performed in binding buffer (15 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% NP-40, 10% glycerol) in a final volume of 10 μl containing 1 μl of GST fusion eluted from beads (50 or 500 ng/μl) and the RNA probe (10,000 cpm). After 20 min at room temperature, samples were separated on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was carried out at a constant voltage of 120 V at 4°C in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Protein-RNA complexes were visualized by autoradiography.

In situ hybridization.

Shuffled yeast strains (yra1::HIS3 <pTRP1-HA-YRA1>) expressing wild-type or truncated versions of HA-Yra1p were grown in YEPD–2% glucose to mid-log phase at 25°C. Cells were shifted to 37°C for 1 h or kept at 25°C before being fixed and processed for in situ hybridization with a digoxigenin-labeled oligo(dT) probe and fluorescently labeled antidigoxigenin antibodies as described earlier (38).

RESULTS

Yra2p, a nonessential homologue of Yra1p, rescues a YRA1 deletion.

Yra1p belongs to the evolutionarily conserved REF family of hnRNP-like proteins. At least two REF members have been identified in Caenorhabditis elegans, Xenopus laevis, mouse, human, S. pombe, and S. cerevisiae (40, 42). Yra2p (YKL214c) corresponds to the second protein in yeast sharing the same domain organization as members of the REF family. Yra2p shows 58% overall homology to Yra1p (19% identity and 39% similarity), and most conserved residues are located within the N and C boxes and the RBD (data not shown).

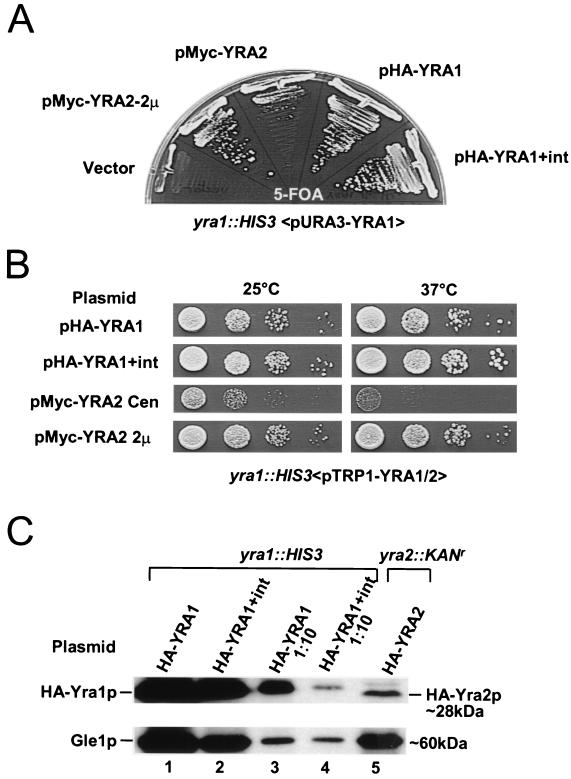

Yra2p is not essential for growth, and a ΔYRA2 strain exhibits no growth phenotype between 18 and 37°C (data not shown). To determine whether Yra2p is functionally related to Yra1p, we tested whether overexpression of Yra2p may complement an otherwise lethal YRA1 deletion strain (Fig. 1A). The YRA1 shuffle strain, which contains a YRA1 deletion covered by the wild-type YRA1 gene on a URA3 plasmid (yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1>) was transformed with empty vector and low-copy-number or multicopy plasmids (pMyc-YRA2 or pMyc-YRA2 2μm) containing the YRA2 gene driven by its own promoter and expressing Yra2p with an N-terminal Myc tag. Transformants were streaked on 5-FOA-containing medium to select against pURA3-YRA1. Consistent with the essential nature of Yra1p, the empty vector did not allow growth of the YRA1 shuffle strain on 5-FOA. In contrast, Yra2p partially complemented the YRA1 deletion when expressed from a low-copy-number plasmid and fully rescued the lethal phenotype when overexpressed (Fig. 1A and B). These data show that Yra1p and Yra2p have redundant or overlapping functions.

FIG. 1.

(A) Overexpression of Yra2p complements the YRA1 deletion. The YRA1 shuffle strain (yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1; pFS1876>) was transformed with an empty TRP1 vector (YCpLac22), and constructs carrying an N-terminally Myc-tagged YRA2 gene on a centromeric (Myc-YRA2; pFS2262) or high-copy-number (Myc-YRA2, 2μm; pFS2262) plasmid and N-terminally HA-tagged YRA1 cDNA (HA-YRA1; pFS2146) or gene plus intron (HA-YRA1+int; pFS2233). Both YRA1 and YRA2 genes were expressed from their own promoters. Complementation of the YRA1 deletion by these constructs was assessed by growing the transformants for 5 days at 30°C on medium containing 5-FOA. (B) Growth phenotypes of FOA+ shuffled strains described for panel A. The indicated strains were grown in rich medium, and 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on YEPD–2% glucose at 25 and 37°C. (C) Yra2p is 10-fold less abundant than Yra1p. Shown are the results of Western blot analysis of the yra1::HIS3 knockout strain containing low-copy-number HA-YRA1 cDNA (pFS2146; lane 1) or HA-YRA1 gene (pFS2233; lane 2) plasmids and a yra2::KANr knockout strain containing a low-copy-number HA-YRA2 plasmid (pFS2345; lane 5). Samples in lanes 3 and 4 are 10-fold dilutions of the protein extracts loaded in lanes 1 and 2. The blot was probed with anti-HA antibody and anti-Gle1p as an internal control for protein loading. The protein signals were revealed with Super Signal West Femto Chemiluminescent substrate.

The YRA1 gene contains an intron which is longer and located further downstream from the methionine initiator codon than are other yeast intervening sequences (27). Low-copy-number plasmids containing the YRA1 gene with or without its intron and encoding a Yra1 protein with an N-terminal HA tag (pHA-YRA1 or pHA-YRA1+int) similarly rescued the YRA1 disruption between 25 and 37°C, indicating that neither the deletion of the YRA1 gene intron nor the HA tag substantially disturbed Yra1p function (Fig. 1A and B).

To define the relative amounts of Yra1p and Yra2p, both factors were expressed as HA-tagged proteins from a low-copy-number plasmid in strains with deletions of the corresponding wild-type gene (Fig. 1C). Western blot analysis showed that the levels of HA-Yra1p expressed from the YRA1 cDNA are about five times higher than when expressed from the YRA1 gene with intron (compare lanes 1 and 2 or 3 and 4). The levels of HA-Yra2p are roughly 10-fold lower than those of HA-Yra1p encoded by the intron-containing gene (compare lanes 4 and 5). Yra2p fully complements a YRA1 deletion when expressed from a high-copy-number plasmid, which raises its levels to those of Yra1p (data not shown). These observations suggest that Yra1p and Yra2p have similar activities (Fig. 1B and C).

Yra1p, Yra2p, and Mex67p associate with mRNPs in vitro.

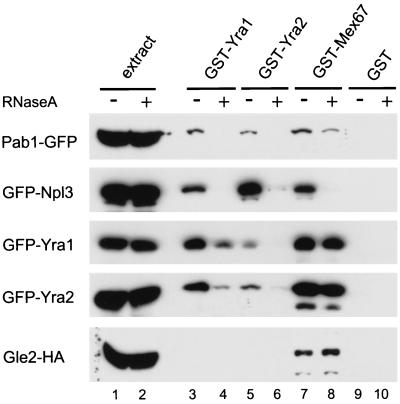

The proposed roles of Yra1p and Mex67p in mRNA export imply that these two proteins associate with mRNP complexes. To initiate the biochemical characterization of these complexes, the interaction of Yra1/2p and Mex67p with mRNPs was indirectly tested by incubating these proteins as E. coli GST fusions with total yeast extracts and testing their ability to select defined components of mRNP complexes. As these interactions may be indirect and mediated by RNA, they were examined in untreated extracts or extracts subjected to a preliminary RNase treatment (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

GST-Yra1, GST-Yra2, and GST-Mex67 associate with mRNPs in total extracts. Whole-cell extracts of strains expressing different RNA binding proteins as HA or GFP fusions were incubated with GST-Yra1, GST-Yra2, GST-Mex67 fusions, or GST alone immobilized on beads. Extracts were first incubated with (+) or without (−) RNase for 20 min at 25°C. Bound proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western analysis using anti-GFP (34) or anti-HA antibodies (lanes 3 to 10). A fraction (1/20) of the total extracts (with or without RNase A treatment) was analyzed in parallel to control for input protein levels (lanes 1 and 2). The protein signals were revealed by normal enhanced chemiluminescence.

Indeed, GST-Yra1, -Yra2, and -Mex67 but not GST alone was able to select two well-described mRNA binding proteins, Npl3p and the poly(A) binding protein Pab1p (20, 23, 32), from yeast extracts expressing these two proteins as GFP fusions. These interactions were disrupted when the extracts were first treated with RNase A, indicating a bridge by RNA and supporting the idea that the Yra1-, Yra2-, and Mex67-GST fusions associate with RNP complexes under these conditions. GST-Yra1 and GST-Yra2 also selected GFP-Yra1 and GFP-Yra2 from extracts; these interactions were only partially affected by RNase treatment, indicating that a fraction of Yra1/2p may form homodimers or heterodimers, as described previously for the mouse homologues (6, 30). In contrast, the association of GST-Mex67 with GFP-Yra1 and GFP-Yra2 was not sensitive to RNase A treatment. In the reciprocal experiment, GST-Yra1 and GST-Yra2 were similarly able to pull down GFP-Mex67 from extracts in an RNA-independent manner (data not shown). These data are consistent with the direct interaction described previously between Mex67p and Yra1p and add Yra2p as an additional partner for Mex67p (40, 42).

GST-Mex67 was also able to pull down HA-tagged Gle2p from extracts, and this interaction was not dependent on RNA (Fig. 2). Gle2p is an NPC-associated protein directly involved in mRNA export (3). The interaction between Mex67p and Gle2p suggests that these two proteins may function in a common step of mRNA export at the pore. GST-Yra1 and -Yra2 did not pull down HA-Gle2p under these conditions either because the assay was not sensitive enough or because the interaction of Gle2p and Yra1/2p with Mex67p is mutually exclusive.

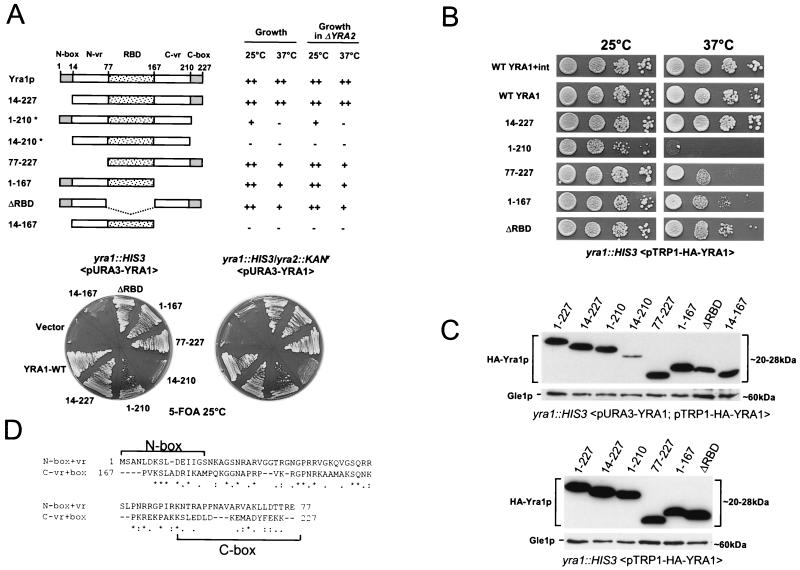

The growth phenotypes of Yra1p truncations indicate a functional redundancy between the N- and C-variable regions.

The conserved domain organization of Yra1p, Yra2p, and other members of the REF family indicates a high evolutionary pressure on the function and overall architecture of these proteins. To define the importance of the Yra1p conserved domains in cell growth, various N- and C-terminal deletions were generated within the HA-YRA1 cDNA and the constructs were tested for their ability to rescue a YRA1 deletion (Fig. 3A). Since Yra2p functionally overlaps with Yra1p (Fig. 1A), the phenotypes of the Yra1 mutants were tested in the presence or absence of Yra2p. The HA-YRA1 mutant plasmids were transformed into the YRA1 shuffle strain (yra1::HIS3 <pURA3 YRA1>) as well as in a YRA1 shuffle strain from which YRA2 had been deleted (yra1::HIS3 yra2::KANr <pURA3-YRA1>). The Yra1 mutant proteins were examined for their ability to rescue the YRA1 deletion in either genetic background by streaking the transformants on 5-FOA-containing medium (Fig. 3A). The growth phenotypes induced by the Yra1 truncations were subsequently examined by spotting serial dilutions of the FOA+ strains at 25 or 37°C (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of Yra1p deletion mutants in the presence or absence of Yra2p. The YRA1 and YRA1/ΔYRA2 shuffle strains (yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1; pFS1876> and yra1::HIS3/yra2::KANr <pURA3-YRA1; pFS1876>) were transformed with constructs coding for the indicated Yra1p truncations. Transformants were grown on 5-FOA plates at 25°C for 5 days (bottom). Growth on 5-FOA indicates complementation of the YRA1 deletion. Duplicates were grown at 37°C (data not shown), and growth phenotypes at 25 and 37°C are summarized at the top. Yra1 truncations indicated by an asterisk have a dominant negative phenotype when expressed in a wild-type strain background. (B) Growth of Yra1 wild-type (WT) and mutant strains at 25 and 37°C. The yra::HIS3 shuffled strains (FOA+) expressing wild-type or mutant Yra1p from a plasmid (TRP1/CEN) were grown in rich medium, spotted as 10-fold serial dilutions on YEPD–2% glucose, and grown for 3 days at 25 or 37°C. (C) Wild-type and mutant HA-Yra1p protein levels expressed in the presence (top) or absence (bottom) of the wild-type pURA3-YRA1 gene. The YRA1 shuffle strain (yra1::HIS3 <pURA3-YRA1>) was transformed with low-copy-number plasmids (TRP1/CEN) expressing HA-tagged wild-type or truncated Yra1p proteins as indicated. Total protein extracts were prepared before (top) or after (bottom) elimination of pURA3-YRA1 on 5-FOA and examined by Western blotting with an anti-HA antibody. The blots were simultaneously incubated with an anti-Gle1p antibody as an internal control for protein loading. The strains expressing Yra1 mutants 14–210 and 14–167 are not viable on 5-FOA. (D) CLUSTALW alignment of the N- and C-terminal regions of Yra1p (N-box+N-vr, aa 1 to 77; C-vr+C-box, aa 167 to 227) reveals a homology of about 50%. The sequences corresponding to the conserved boxes are indicated.

Deletion of the highly conserved N box (mutant 14–227) did not affect cell growth at 25°C, and cells grew marginally less well at 37°C. Deletion of the C box (mutant 1–210) impaired growth at 25°C, and cells did not grow at 37°C. Deletion of both conserved boxes was lethal, indicating that at least one conserved box is required for viability. The two mutants lacking the C-terminal box also had a strong dominant negative phenotype (data not shown). Unexpectedly, a mutant lacking the RBD was perfectly viable at 25°C, and growth was mildly affected at 37°C. More importantly, mutant 77–227 or 1–167, lacking the complete N-terminal or C-terminal domain, respectively, also grew well at 25°C with a minor growth defect at 37°C. These observations together with the inessential nature of the RBD support the idea that the N-box+N-vr (N-terminal region) or the C-vr+C-box (C-terminal region) is sufficient for viability. The expression of these short regions without the RBD, however, did not rescue ΔYRA1, or only very poorly in the case of the C-vr+C-box (amino acids [aa] 167 to 227), presumably because of the low expression levels of these short Yra1 portions (data not shown). Finally, a construct encoding just the N-vr region and the RBD (mutant 14–167) was expressed to wild-type levels but did not support growth on 5-FOA, further supporting the idea that at least one conserved box is required for viability. In most cases, the growth phenotypes of the mutant Yra1 proteins were only marginally enhanced in the absence of Yra2p, indicating that this protein does not substantially contribute to growth when expressed at normal levels.

Western blot analysis of the Yra1 mutant proteins before and after shuffling on 5-FOA showed that all Yra1 truncations were expressed (Fig. 3C). The amounts of the nonviable mutant 14–210 were clearly lower than those of full-length Yra1p, whereas the levels of the viable truncations 77–227, 1–167, and ΔRBD were close to those of the wild type. In other experiments, however, involving different strain backgrounds and slightly different culture conditions, the levels of these three truncations were substantially reduced (see below), and these variations are difficult to explain at present.

In conclusion, the viability of Yra1 truncations containing the RBD and just one conserved box and variable region (mutants 1–167 and 77–227) strongly suggests a functional redundancy between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of Yra1p. Accordingly, alignment of these domains (aa 1 to 77 and 167 to 227) revealed substantial similarity (around 50%), supporting the idea that these two regions have similar functions (Fig. 3D).

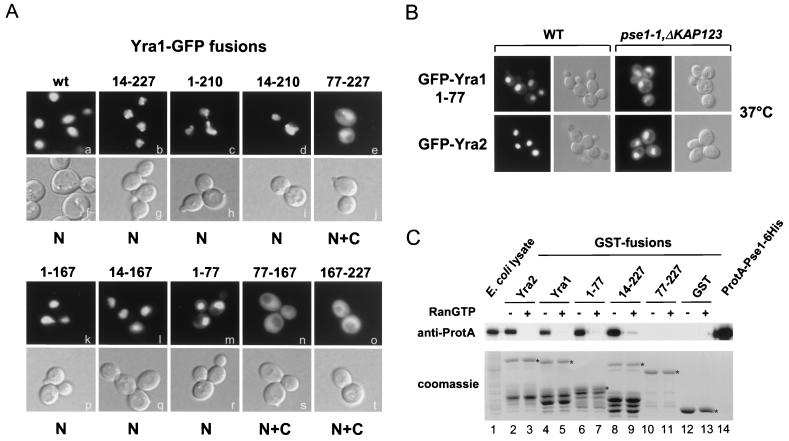

Yra1p contains an NLS in its N-vr region and is imported by the importin-β-like factor Pse1p.

Yra1p is located within the nucleus at steady state. To map the nuclear localization signal (NLS) in Yra1p, various portions of the protein were expressed as GFP fusions in the yeast wild-type strain W303 and examined for localization (Fig. 4A). A fusion containing the N-terminal region of Yra1p (aa 1 to 77) efficiently targeted GFP into the nucleus (panel m). The deletion of the N box from full-length Yra1p (14–227) did not interfere with its nuclear localization (panel b), indicating that the NLS lies within the N-vr region of the protein. Consistently, all the truncations containing the N-vr appeared nuclear (panels c, d, k, and l). Notably, the GFP fusions missing either one or both highly conserved boxes (14–227, 1–210, and 14–210) had the tendency to form aggregates within the nucleus or at the nuclear periphery (panels b, c, and d; see Discussion). GFP fusion 77–227, which lacks the N-vr region, exhibited weak nuclear accumulation as well as cytoplasmic staining consistent with a nuclear import defect (panel e). The nuclear fraction of this mutant protein may result from passive diffusion and is sufficient for function since the Yra1 77–227 truncation is perfectly viable (Fig. 3A). Finally, GFP fusions containing the RBD (77–167) or the C-terminal region (167–227) exhibited a homogenous distribution throughout the cell presumably due to free diffusion of these small proteins between the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (panels n and o). It cannot be excluded that the functional truncation 77–227 contains a second weaker NLS. This NLS could be revealed by fusing the C-terminal region of Yra1p to multiple GFP moieties to generate a chimeric protein that is too large to cross the nuclear envelope by diffusion. In the absence of an additional NLS, the fusion protein is expected to be restricted to the cytoplasm and unable to rescue a YRA1 deletion.

FIG. 4.

(A) The NLS of Yra1p maps within the N-vr region. Wild-type (wt) yeast cells were transformed with plasmids expressing full-length or truncated versions of Yra1p fused to GFP from a galactose-inducible promoter. Transformants were grown at 30°C to mid-log phase in selective medium containing glucose, washed, induced for 4 h in selective medium containing galactose, and examined for GFP fluorescence signal under a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a 100× objective lens and a cooled charge-coupled device camera. Cells were photographed for GFP fluorescence (panels a to e and k to o) and by Nomarski optics (panels f to j and p to t). The localization of each GFP fusion is indicated as N (nuclear) or N+C (nuclear and cytoplasmic) below each set of pictures. (B) The importin-β-like transport factor Pse1p mediates the nuclear import of Yra1-GFP and Yra2-GFP fusions. Plasmids expressing GFP fused to the N terminus of Yra1p (GFP-Yra1-1–77 containing the NLS) or Yra2p (GFP-Yra2p) from a galactose-inducible promoter were transformed into a wild-type strain (WT) or a strain containing a conditional mutation in PSE1 and a deletion of KAP123 (pse1-1 Δkap123), two genes encoding functionally related importin-β-like import factors. Transformants were grown to mid-log phase in selective medium plus glucose, washed, induced for 4 h in medium containing 3% galactose–1% raffinose, and shifted to 37°C for 1 h. Cells were then photographed for GFP fluorescence (left) and by Nomarski optics (right). (C) Pse1p directly interacts with Yra1p and Yra2p in vitro. The indicated Yra1-GST and Yra2-GST fusions or GST alone immobilized on glutathione beads was incubated with an E. coli lysate containing the ProtA-Pse1-6xHis fusion protein in the presence or absence of RanQ69L-GTP. After washing, proteins bound to the beads were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and either subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-ProtA antibody to detect ProtA-Pse1-6xHis bound to the beads (top) or Coomassie blue stained to visualize the GST fusions present in the binding reactions (bottom). Full-length GST fusions are indicated by an asterisk.

To define the nuclear import pathway used by Yra1p and Yra2p, the distribution of GFP-Yra1-1–77 and GFP-Yra2 fusions was examined in strains defective in various importin-β-like import factors. The localization of these GFP fusions was not modified in strains containing conditional alleles in KAP95/importin β (14), KAP104 (1), or CSE1 (45) or strains disrupted for MTR10 (37), SXM1 (35), and NMD5 (A. Jacobson, unpublished data, and data not shown). In contrast, both fusions could be detected in the cytoplasm of a pse1-1 Δkap123 temperature-sensitive strain shifted to 37°C (35), indicating that Pse1p contributes to the nuclear import of Yra1p and Yra2p (Fig. 4B). However, GFP-Yra1-1–77 and GFP-Yra2 were only partially delocalized in this mutant background, suggesting that the mutation is too weak to completely block import or that additional import factors are involved.

The direct interaction of Yra1p/Yra2p with Pse1p was examined in vitro (Fig. 4C). Full-length Yra2p, Yra1p, and Yra1 truncations were purified as GST fusions on glutathione beads. Loaded beads were incubated with an E. coli lysate containing a ProtA-Pse1-6xHis fusion protein as described previously (10) in the presence or absence of mammalian RanQ69L-GTP. This mutant form of Ran is unable to hydrolyze GTP. The binding of ProtA-Pse1-6xHis to the beads was examined by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with an anti-ProtA antibody. Both GST-Yra2 and GST-Yra1 but not GST alone directly interacted with ProtA-Pse1-6xHis. This interaction was disrupted by Ran-GTP, confirming that Pse1p acts as an import receptor for these related hnRNP-like proteins (lanes 2 to 5, 12, and 13). Furthermore, the GST-Yra1 fusions 1–77 and 14–227 but not 77–227 interacted with ProtA-Pse1-6xHis, confirming that the N-vr region of Yra1p mediates the interaction with Pse1p (lanes 6 to 11). The localization and binding experiments taken together demonstrate that Yra1p contains a strong NLS within the N-vr and not the C-vr region as proposed earlier (27, 40); however, this NLS is not absolutely required for function, since a truncation lacking the N-terminal domain is viable.

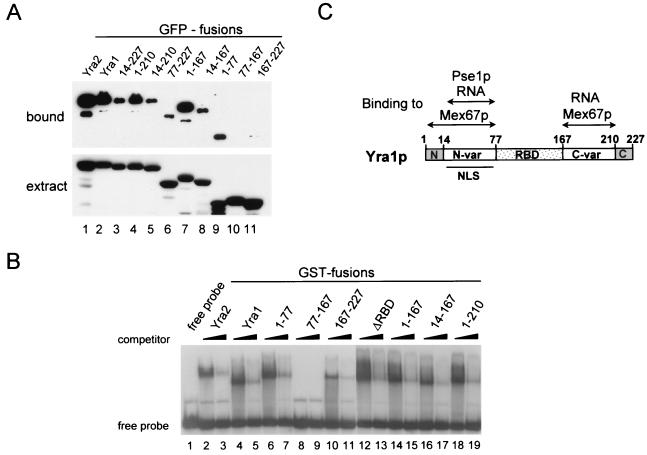

The N-vr and C-vr regions of Yra1p mediate binding to Mex67p.

Yra1p directly interacts with Mex67p (40, 42). To investigate which region of Yra1p binds Mex67p, different Yra1p deletion mutants fused to GFP were expressed in yeast and whole-cell extracts were used in pull-down assays with recombinant GST-Mex67 (Fig. 5A). As already shown in Fig. 2, GFP-Yra1 as well as GFP-Yra2 binds to GST-Mex67 (lanes 1 and 2). Deletion of the C-terminal box of Yra1p (fusion 1–210) did not affect binding to GST-Mex67 (lane 4); however, deletion of the N-terminal box (fusion 14–227) substantially reduced binding, indicating that this conserved sequence contributes to the interaction with Mex67p (lane 3). Deletion of both conserved boxes (fusion 14–210) did not affect binding efficiency any more than did deletion of the N box alone (lane 5).

FIG. 5.

The N- and C-terminal variable regions of Yra1p bind to Mex67p and to RNA. (A) GST-Mex67 pull-downs of Yra2- and Yra1-GFP fusions from extracts. The indicated Yra1- and Yra2-GFP fusions were expressed in vivo from a galactose-inducible promoter. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with GST-Mex67 purified from E. coli and immobilized on beads. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody (upper panel). A fraction (1/20) of the total extracts was analyzed in parallel to confirm that all the GFP fusions were expressed to comparable levels (lower panel). (B) Yra1p and Yra2p bind RNA in vitro. An electrophoretic mobility retardation assay was performed with an 80-nucleotide 32P-labeled RNA probe (lane 1) and the purified GST fusions indicated above the lanes. For each protein, binding was carried out in the presence of 50 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18) or 150 (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19) ng of tRNA competitor per μl. The binding reaction mixtures contained 500 ng of GST fusion 77–167 (RBD) and 50 ng of all the other fusion proteins. Protein-RNA complexes were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (C) Summary diagram of Yra1p domains and partners.

The interaction between Yra1p and Mex67p is likely to be essential for mRNA export. Because Yra1p truncations containing the RBD and either the N-terminal or the C-terminal domain are sufficient for viability (Fig. 3A), these protein fragments should bind Mex67p. Indeed, both the 1–167 and 77–227 GFP fusions interacted with GST-Mex67 (lanes 6 and 7), although the 77–227 fusion bound with lower affinity. The RBD alone (77–167) did not bind GST-Mex67 (lane 10), but the N- and C-terminal regions (1–77 and 167–227) alone interacted with GST-Mex67p, although to different extents (lanes 9 and 11). The N-terminal region exhibits a higher affinity for Mex67p under these experimental conditions, and the N box substantially contributes to this interaction (compare lanes 6, 7, and 8). These data taken together indicate that either the N-vr or the C-vr regions of Yra1p are necessary for Mex67p binding. These observations are consistent with the analyses of Yra1 mutants in vivo (Fig. 3A) and support the idea that the N- and C-terminal regions of Yra1p are functionally overlapping.

Our attempts to map interaction domains by two-hybrid analysis were unsuccessful; a Mex67 bait fusion interacted efficiently with FG-nucleoporins or Mtr2p preys but did not interact with a Yra1 prey, although this fusion was functional based on its ability to rescue a YRA1 disruption. One possibility may be that the activation domain of the Yra1 prey fusion is not exposed correctly (data not shown).

The N-vr and C-vr regions of Yra1p bind RNA.

Yra1p was first identified as a protein with RNA-RNA annealing activity (27) and was more recently shown to bind RNA (40, 42). The central regions of Yra1p and Yra2p show strong homology to an RNP-like RBD (RRM), although the RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs are not highly conserved. To test whether Yra2p binds RNA in vitro and to define the region(s) in Yra1p mediating the interaction with RNA, various GST fusion proteins purified from E. coli were tested for their ability to bind an 80-nucleotide-long 32P-labeled RNA probe in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Fig. 5B). Yra2p and Yra1p exhibited comparable affinities for the RNA probe, and the complexes formed could be challenged with an excess of tRNA, reflecting a nonspecific interaction between the GST fusions and the RNA. Strikingly, the RBD (77–167) exhibited no RNA binding activity, even when added to the binding reactions in 10-fold-higher amounts than the other proteins. In contrast, both the N-terminal (1–77) and C-terminal (167–227) domains bound the RNA. Consistently, deletion of the RBD (ΔRBD) did not affect interaction with RNA. Furthermore, deletion of the conserved C box (1–210) or the complete C-terminal domain (1–167) did not substantially affect RNA binding. Finally, a fusion containing just the N-vr region and the RBD (14–167) was still able to induce an RNA shift. These observations taken together indicate that the highly conserved N box, C box, and RBD are not required for RNA binding but that at least one variable region, N-vr or C-vr, is necessary to interact with RNA. These data show that the two variable regions of Yra1p not only interact with Mex67p but also are implicated in RNA binding (Fig. 5C). Earlier data have shown that Yra1p can interact simultaneously with Mex67p and RNA (42).

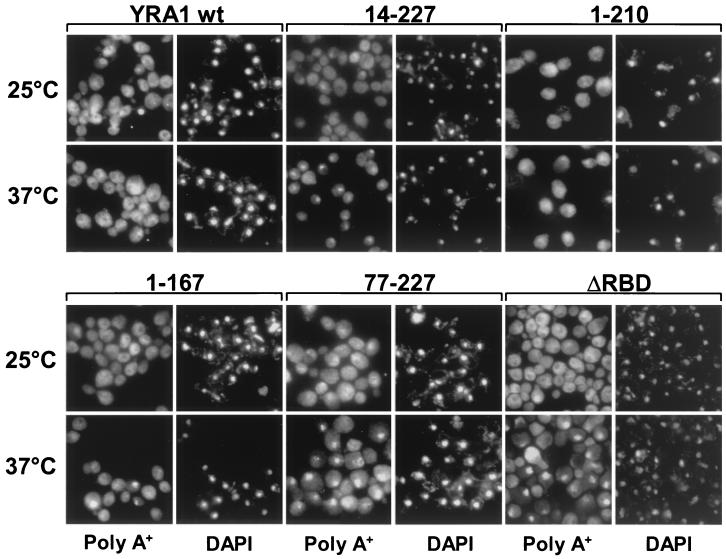

Yra1 truncations induce poly(A)+ RNA export defects.

To assess the importance of individual Yra1p domains in poly(A)+ RNA export in vivo, in situ hybridizations with oligo(dT) were performed on strains expressing functional truncations of Yra1p as described for Fig. 3B. The strains were grown at 25°C to mid-log phase and subjected to analysis by fluorescent in situ hybridization at 25°C or after shifting the cells for 1 h to 37°C (Fig. 6). No nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA was detected in strains expressing wild-type Yra1p or the C-box deletion mutant (1–210). Deletion of the C-terminal domain (mutant 1–167) induced a modest poly(A)+ RNA export defect at 37°C. Deletion of the N box (14–227) or the complete N-terminal region (77–227) induced a more substantial export defect at 37°C. As the N-terminal deletions showed a lower affinity for Mex67p in vitro (Fig. 5A), the data indicate a correlation between the abilities of Yra1 mutants to interact with Mex67 and to promote poly(A)+ RNA export. Because the regions of Yra1p involved in Mex67p interaction also mediate RNA binding, it cannot be excluded that the export defect in strains lacking one of the two RNA binding regions (1–167 or 77–227) is due, in part, to a lower affinity of these Yra1 truncations for RNA in vivo, although they did not show substantially different RNA binding activities in vitro (Fig. 5B). Finally, inefficient nuclear localization of mutant 77–227, which lacks the NLS, may also contribute to the stronger export defect in this mutant (Fig. 4A). Although the RBD is required for neither Mex67p nor RNA binding in vitro (Fig. 5), the ΔRBD mutant strain exhibited a substantial poly(A)+ RNA export defect at 37°C, indicating that this conserved domain is important for optimal Yra1p function in mRNA export.

FIG. 6.

Localization of poly(A)+ RNA in strains expressing wild-type (wt) Yra1p or Yra1p truncations as indicated at the top. Strains were grown at 25°C or shifted for 1 h to 37°C. Poly(A)+ RNA was detected by in situ hybridization with a digoxigenin-labeled oligo(dT) probe and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody (left panels). The location of the nuclei was determined by staining the same cells with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; right panels). Cells were photographed as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

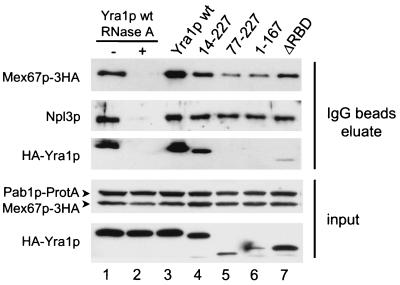

The association of Mex67p with mRNPs is weakened in strains expressing mutant Yra1p.

We have shown that recombinant Yra1p, Yra2p, and Mex67p associate with mRNP complexes in extracts (Fig. 2), and in situ hybridizations on Yra1 mutant strains support the idea that efficient mRNA export depends on the interaction of Mex67p with Yra1p. To assess whether Yra1p influences the association of Mex67p with mRNPs in vivo in a more direct assay, we examined the levels of Mex67p associated with mRNP complexes in the presence of wild-type or mutant Yra1p (Fig. 7). For these experiments, the poly(A) binding protein Pab1p was tagged with ProtA at its C terminus in strains expressing HA-tagged Yra1p (wild type or mutant) as well as HA-tagged Mex67p (Materials and Methods). Pab1p is a very abundant, mainly cytoplasmic protein, but a fraction of Pab1p is nuclear and interacts with components of the 3′-end formation complex CF1A (23); Pab1p is therefore likely to be bound to nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNP complexes.

FIG. 7.

Yra1p facilitates the recruitment of Mex67p to the mRNP. mRNP complexes associated with Pab1p-ProtA in extracts expressing wild-type (wt; lanes 1 to 3) or mutant (lanes 4 to 7) HA-tagged Yra1p and HA-tagged Mex67p were affinity purified on matrix-bound IgG. Equal amounts of each extract were used for affinity purification. In lanes 1 and 2, extract containing wild-type Yra1p was preincubated for 20 min at 25°C with or without 30 μg of RNase A before purification on IgG beads. Proteins bound to Pab1-ProtA were eluted by high-salt treatment (2 M KCl) of the beads. IgG bead eluates (top) or total input extracts (bottom) were analyzed by Western blotting. Anti-HA antibodies were used to detect Mex67p and Yra1p; the hnRNP-like protein Npl3p was used as an internal control for mRNP purification and revealed with anti-Npl3p antibodies. Pab1-ProtA was detected in the input samples by cross-reaction of the anti-HA primary and anti-mouse secondary antibodies. For all samples, 1/10 of the eluted samples (IgG bead eluate) was used for the analysis of Mex67p and Npl3p and 1/4 was used for Yra1p. One-twentieth of the material used in each pull-down experiment was analyzed in parallel to determine the levels of these proteins in the starting extracts (input). Western blots were developed with Super Signal West Femto Chemiluminescent substrate in the case of IgG bead eluate samples and Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate in the case of input samples.

Total extracts were prepared from these strains grown at 30°C, and the Pab1-ProtA was affinity purified on matrix-bound IgG. Pab1p-associated mRNP complexes were eluted from the beads with high salt (2 M KCl) and analyzed for the presence of Mex67p, Yra1p, and the well-characterized mRNP-associated hnRNP-like protein Npl3p by Western blotting (Fig. 7). Mex67p, Yra1p, and Npl3p copurified with Pab1-ProtA on the IgG beads. This interaction was inhibited by pretreating the extract with RNase A, indicating that the association of Pab1p with Mex67p, Npl3, and Yra1p is bridged by RNA and that mRNP complexes were selected under these conditions (Fig. 7, compare lanes 1 and 2). The levels of Npl3p in the IgG fraction remained unchanged irrespective of the nature of Yra1p in the extract. These observations confirmed that similar amounts of RNP complexes had been selected from wild-type and mutant extracts and that the binding of Npl3p was independent of Yra1p (compare lane 3 with lanes 4 to 7). In contrast, lower amounts of Mex67p were reproducibly pulled down by Pab1p-ProtA from extracts containing mutant Yra1p (compare lane 3 with lanes 4 to 7). Because the levels of Mex67p in the input were comparable in all samples, these data strongly support a role for Yra1p in the efficient recruitment and/or association of Mex67p with the mRNP complex. Some Yra1 mutant proteins, i.e., 77–227, 1–167, and ΔRBD, were expressed in very small amounts in the Pab1-ProtA/Mex67-3HA double-tagged strain, resulting in a more pronounced temperature-sensitive phenotype (lanes 5 to 7, input, and data not shown). These mutant proteins were barely or not at all detectable in the IgG eluate, either because the assay was not sensitive enough or because these proteins dissociate from the mRNP during purification. The low level of expression of these mutant proteins is likely to contribute to the lower levels of Mex67p associated with mRNPs in these extracts. These data taken together show that the association of Mex67p with mRNP complexes in vivo is affected in Yra1 mutants defective in poly(A)+ RNA export and support the idea that Yra1p contributes to the binding of Mex67p to mRNPs.

DISCUSSION

Yra1p and other members of the REF family of hnRNP-like proteins have been proposed to participate in mRNA export by recruiting the mRNA export factor Mex67p/TAP to the mRNP. This study presents a functional analysis of Yra1p conserved domains and shows that Yra1 deletion mutants defective in Mex67p interaction have parallel poly(A)+ RNA export defects and a decrease in the amounts of Mex67p associated with mRNP complexes. These results confirm the model that Yra1p facilitates the recruitment of Mex67p to the mRNP to promote mRNA export. Overexpression of Yra2p, a second member of the REF family in S. cerevisiae, fully complements a YRA1 deletion, indicating overlapping or redundant functions for these two proteins (Fig. 1).

REF proteins contain a central conserved RNP-type RBD and two highly conserved N and C boxes separated by more variable regions, N-vr and C-vr. Surprisingly, the RBD of Yra1p exhibits neither RNA nor Mex67p binding activity in vitro and is not essential for growth. In contrast, both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of Yra1p mediate RNA and Mex67p binding in vitro. Consistent with the functional overlap between these two domains, Yra1 truncations lacking either the N-terminal or C-terminal domain are viable (Fig. 3 and 5). Neither the N box nor the C box is absolutely required for RNA or Mex67p binding in vitro, but at least one of these sequences is necessary for viability. One possibility is that these conserved boxes optimize the binding activities of the adjacent N-vr or C-vr region in vivo. Solving the three-dimensional structure of Yra1p, in a cocrystal with Mex67p and/or RNA, will be necessary to understand the function of its conserved domains.

Deletion of the N box or the complete N-terminal or C-terminal domain induces nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA. As there was a good correlation between the effect of the Yra1 mutations on Mex67p binding and the degree of nuclear poly(A)+ RNA accumulation (Fig. 5 and 6), the data support the idea that mRNA export depends on an efficient interaction between Yra1p and Mex67p.

The Yra1 ΔRBD mutant efficiently binds RNA in vitro and contains both Mex67p binding domains; this mutant nevertheless induces a substantial poly(A)+ RNA export defect, indicating that the RBD is important for efficient mRNA export. The RBD may have a structural role which is important for the proper folding of Yra1p in vivo. Alternatively, it may engage in additional nonessential interactions which stimulate export. In that respect, the conserved RBD of Aly, the Yra1p mouse homologue, has been shown to directly interact with the activation domain of a subset of transcription factors, suggesting that Aly, and by analogy Yra1p, may contribute to multiple steps in mRNA biogenesis and possibly enhance export by establishing a functional link with the transcription machinery (6, 44).

The amounts of Mex67p associated with mRNP complexes were substantially reduced in the Yra1 mutant strains deficient in mRNA export (Fig. 7). In the case of the Yra1 ΔRBD mutant, these observations indicate that the RBD, although not directly involved, may nevertheless optimize the interaction between Mex67p and Yra1p. The impaired association of Mex67p with mRNP complexes in the Yra1 mutant strains may also be due, in part, to the lower levels of expression of the Yra1 mutant proteins in the starting extracts. For unclear reasons, the levels of the N- and C-terminal truncations (77–227 and 1–167) were particularly low in the Pab1-ProtA/Mex67-3HA double-tagged strain. As proportionally less Mex67p copurified with mRNPs in these samples, the data are fully consistent with a direct role of Yra1p in recruiting Mex67p to the mRNP. The poorly expressed Yra1 mutant proteins 1–167 and 77–227 were not detectable in the affinity-purified mRNP complexes, whereas Mex67p was reduced but clearly visible in these samples. These observations may suggest that additional interactions stabilize Mex67p on the mRNP after its recruitment by Yra1p. Alternatively, a fraction of Mex67p may associate with the mRNP independently of Yra1p. Finally, Mex67p may be recruited to different mRNP populations, some of which are naturally devoid of Yra1p. The results taken together show that poly(A)+ RNA export depends on the binding of Mex67p to the mRNP through an interaction with Yra1p. Whether the export of all or only a subset of mRNP complexes depends on this interaction is an interesting question for the future.

At least one highly conserved N box or C box is required for growth. However, the N box and C box are unlikely to have equivalent roles, as the deletion of the C box, but not the N box, induces a temperature-sensitive phenotype (Fig. 3). In addition, Yra1 mutants lacking the C box (or both the N box and C box) have a substantial dominant negative growth phenotype in a wild-type strain background even when expressed from a low-copy-number plasmid (data not shown). This phenotype may be related to the tendency of these mutants to form aggregates when expressed as GFP fusions (Fig. 4A). The C-box deletion mutant does not generate a clear poly(A)+ RNA export defect when expressed on its own (Fig. 6). As the C box is not playing a major role in Mex67p or RNA binding (Fig. 5), it may be required for a different aspect of Yra1p function. The C box could engage in nonessential interactions with additional partners or mediate conformational changes important for association-dissociation reactions between Yra1p and the mRNP or between Yra1p-containing complexes and other components along the export pathway.

The functional organization of the Yra1p domains has been conserved in REF proteins from higher eucaryotes. In mouse REF1-II and REF2-II, the central RBD similarly exhibits no RNA or TAP binding activity, whereas the N-terminal and C-terminal domains are implicated in both of these interactions. However, as in Yra1p, the RBD is important for the activity of REF1-II in mRNA export in vivo (30). Yra1p and REF2-II contain an NLS within the N-vr region, and the two proteins are imported through conserved pathways, since nuclear import of REF2-II is promoted by RanBP5, the mammalian homologue of Pse1p. REF2-II import is also mediated by transportin and a combination of importin-β and RanBP7 (D. Görlich and E. Izaurralde, personal communication). Nuclear import of Yra1p by additional import receptors could explain the partial delocalization of GFP-Yra1p in the pse1-1 Δkap123 mutant (Fig. 4B).

The central M domain of Mex67p mediates heterodimerization with the essential export factor Mtr2p, and this interaction is important for the localization of Mex67p at the pore. Consistently, a recent report indicates that Mex67p interacts with FG-nucleoporins in vitro only as a Mex67p-Mtr2p heterodimer (33, 39). Another report proposes that Mtr2p is not absolutely required but may enhance the interaction of Mex67p with FG-nucleoporins in vitro (41). Here, we examined the interaction of a GST-Mex67 fusion with wild-type or mutant GFP-Yra1 fusions expressed in yeast extracts. Mtr2p present in extracts could associate with GST-Mex67p and enhance its ability to interact with GFP-Yra1. However, our earlier data showed that Mex67p and Yra1p interact in vitro in the absence of Mtr2p. We have also shown that the N-terminal domain of TAP including the leucine-rich repeat region (aa 1 to 372) mediates the interaction with Yra1p/REF proteins (42). This interaction is conserved in yeast, as the corresponding N-terminal domain of Mex67p (aa 1 to 264) interacts with GST-Yra1/2 fusions (D. Zenklusen, unpublished data). It is therefore unlikely that Mtr2p is required for the Mex67p-Yra1p interaction, but it could modulate this association.

Both mouse REF2-II and Aly (REF1-I) proteins shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm even in the absence of RNA (30, 47). Based on the extensive functional conservation between Yra1p and REF2-II, Yra1p is likely to shuttle as well, although a standard assay for protein shuttling in yeast (20) initially scored Yra1p as a nonshuttling protein (40, 42). As an indication that Yra1p is shuttling between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, localization of a functional ProtA-tagged Yra1p by immunoelectron microscopy has detected the fusion protein on both sides of the pore, in association with the nuclear basket and the cytoplasmic fibrils (B. Fahrenkrog and E. Izaurralde, personal communication).

Yra2p overexpression fully rescues a YRA1 deletion, and GFP-Yra2 was selected from extracts by GST-Mex67 in an RNA-independent manner, consistent with a direct interaction between these two proteins (Fig. 2). Although the activities of Yra2p and Yra1p appear to overlap broadly, the two proteins may have distinct roles under physiological conditions. To investigate a possible role for Yra2p in the export of a specific class of transcripts, we examined heat shock RNA export in a ΔYRA2 strain. However, analysis of heat shock protein synthesis in this strain after a shift to 42°C did not reveal an essential role for Yra2p in the export of these regulated transcripts (Y. Strahm, unpublished data). Further studies will be required to determine whether Yra1p and Yra2p are involved in the export of different types of transcripts.

The GST pull-down experiments also identified an RNA-independent interaction between Mex67p and the RNA export factor Gle2p (Fig. 2). An interaction between the human homologues TAP and hGle2 has been described earlier, which involves the C-terminal half of TAP, indicating that distinct domains of TAP bind REF and hGle2 (2). The corresponding proteins in S. pombe, spMex67p and spRae1p, were also shown to associate in a complex in vivo (46). Gle2p, spRae1p, and hGle2 accumulate at the NPC, and hGle2 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and cross-links to poly(A)+ RNA in vivo (3, 19, 24, 28). Gle2p, spRae1p, and hGle2 are thought to function at the pore, but the exact role of these homologous proteins in mRNA export is not defined. They may interact with the mRNP via a yet unidentified mRNP component and promote export in conjunction with Mex67p/TAP. Alternatively, they may contribute to the interaction of Mex67p/spMex67p/TAP with the pore. Gle2p was not detected in the pull-down assays with GST-Yra1p and GST-Yra2p, suggesting that these proteins do not directly associate. These observations also suggest that Mex67p bound to Gle2p in extracts may not be recognized by GST-Yra1/2, either because the fraction of Mex67p associated with Gle2p is too low or because the interaction of Yra1p, Yra2p, and Gle2p with Mex67p is mutually exclusive. Further studies will be required to elucidate the functional relationship between Mex67p and Gle2p.

YRA1 was initially isolated in a screen for GAL-inducible yeast cDNAs causing overexpression-mediated growth arrest (9). We observed a similar phenotype when overexpressing the YRA1 cDNA from its own promoter. Interestingly, overexpression of the YRA1 gene, which contains an unusually long intron, had no dominant negative phenotype, whether it was expressed from GAL1 or its own promoter. The levels of Yra1p were 5 to 10 times lower in strains expressing the YRA1 gene than in those expressing the YRA1 cDNA (Fig. 1C). These observations suggest that the Yra1p levels are tightly controlled by a mechanism involving the YRA1 intron. It will be interesting to determine whether Yra1p affects its own production by interfering with the transcription, splicing, or stability of the corresponding pre-mRNA.

Recent reports showed that mouse Aly (REF1-I) and several other proteins, including SRm160, DEK, RNPS1, and Y14, are recruited to mRNP complexes during spliceosome assembly and become tightly associated with the spliced mRNPs. Splicing was proposed to be required for efficient export by ensuring a tight coupling between the processing and export machineries (18, 21, 47). However, anti-REF antibodies were shown to inhibit the export of mRNAs from Xenopus oocyte nuclei, whether these were injected as in vitro-transcribed pre-mRNAs or as non-intron-containing mRNAs, indicating that REF associates with both types of transcripts in vivo (30). In yeast, only a small fraction of genes contains introns and splicing is therefore unlikely to be a necessary step for export. Yra1p and/or Yra2p could nevertheless stimulate the export of spliced transcripts through preferential association with these mRNAs. It will be interesting to determine whether Yra1 mutants primarily affect the export of spliced transcripts and whether Yra1p and/or Yra2p associates with spliceosomes and splicing products in vitro.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Elisa Izaurralde for valuable discussions and sharing data prior to publication. We are grateful to E. Izaurralde, U. Kutay, M. Rosbash, and T. Heick-Jensen for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank D. Görlich for the RanQ69L and Pse1p expression constructs; P. Silver for plasmids, strains, and anti-GFP and anti-Npl3p antibodies; and J. Aitchison, M. Fitzgerald-Hayes, E. Hurt, A. Hopper, A. Jacobson, A. M. Tartakoff, and S. Wente for different yeast strains. We are also grateful to Verena Müller for technical assistance and R. Sahli, D. Sanglard, and other members of the Microbiology Institute for their help.

These studies were supported by a research grant (no. 049135.96/1) from the Swiss National Science Foundation to F.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitchison J D, Blobel G, Rout M P. Kap104p: a karyopherin involved in the nuclear transport of messenger RNA binding proteins. Science. 1996;274:624–627. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Aris J P, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:17–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachi A, Braun I C, Rodrigues J P, Pante N, Ribbeck K, von Kobbe C, Kutay U, Wilm M, Gorlich D, Carmo-Fonseca M, Izaurralde E. The C-terminal domain of TAP interacts with the nuclear pore complex and promotes export of specific CTE-bearing RNA substrates. RNA. 2000;6:136–158. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailer S M, Siniossoglou S, Podtelejnikov A, Hellwig A, Mann M, Hurt E. Nup116p and Nup100p are interchangeable through a conserved motif which constitutes a docking site for the mRNA transport factor Gle2p. EMBO J. 1998;17:1107–1119. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bear J, Tan W, Zolotukhin A S, Tabernero C, Hudson E A, Felber B K. Identification of novel import and export signals of human TAP, the protein that binds to the constitutive transport element of the type D retrovirus mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6306–6317. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun I C, Rohrbach E, Schmitt C, Izaurralde E. TAP binds to the constitutive transport element (CTE) through a novel RNA-binding motif that is sufficient to promote CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. EMBO J. 1999;18:1953–1965. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruhn L, Munnerlyn A, Grosschedl R. ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCR alpha enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1997;11:640–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burd C G, Dreyfuss G. Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science. 1994;265:615–621. doi: 10.1126/science.8036511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daneholt B. A look at messenger RNP moving through the nuclear pore. Cell. 1997;88:585–588. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81900-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinet C, Vargas A M, el Maghrabi M R, Lange A J, Pilkis S J. Expression of the liver 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase mRNA in FAO-1 cells. Biochem J. 1993;293:173–179. doi: 10.1042/bj2930173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorlich D, Dabrowski M, Bischoff F R, Kutay U, Bork P, Hartmann E, Prehn S, Izaurralde E. A novel class of RanGTP binding proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:65–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Görlich D, Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grüter P, Tabernero C, von Kobbe C, Schmitt C, Saavedra C, Bachi A, Wilm M, Felber B K, Izaurralde E. TAP, the human homolog of Mex67p, mediates CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. Mol Cell. 1998;1:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurt E, Strasser K, Segref A, Bailer S, Schlaich N, Presutti C, Tollervey D, Jansen R. Mex67p mediates nuclear export of a variety of RNA polymerase II transcripts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8361–8368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iovine M K, Wente S R. A nuclear export signal in Kap95p is required for both recycling the import factor and interaction with the nucleoporin GLFG repeat regions of Nup116p and Nup100p. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:797–811. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.4.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javerzat J P, Cranston G, Allshire R C. Fission yeast genes which disrupt mitotic chromosome segregation when overexpressed. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4676–4683. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang Y, Cullen B R. The human Tap protein is a nuclear mRNA export factor that contains novel RNA-binding and nucleocytoplasmic transport sequences. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1126–1139. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katahira J, Strässer K, Podtelejnikov A, Mann M, Jung J U, Hurt E. The Mex67p-mediated nuclear mRNA export pathway is conserved from yeast to human. EMBO J. 1999;18:2593–2609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kataoka N, Yong H, Kim N V, Velazquez F, Perkinson R A, Wang F, Dreyfuss G. Pre-mRNA splicing imprints mRNA in the nucleus with a novel RNA-binding protein that persists in the cytoplasm. Mol Cell. 2000;6:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraemer D, Blobel G. mRNA binding protein mrnp 41 localizes to both nucleus and cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9119–9124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M S, Henry M, Silver P A. A protein that shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is an important mediator of RNA export. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1233–1246. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Hir H, Izaurralde E, Maquat L E, Moore M J. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20–24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 2000;19:6860–6869. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longtine M S, McKenzie A, Demarini D J, Shah N G, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle J R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minvielle-Sebastia L, Preker P J, Wiederkehr T, Strahm Y, Keller W. The major yeast poly(A)-binding protein is associated with cleavage factor IA and functions in premessenger RNA 3′-end formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7897–7902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy R, Watkins J L, Wente S R. GLE2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe export factor RAE1, is required for nuclear pore complex structure and function. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1921–1937. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakielny S, Dreyfuss G. Transport of proteins and RNAs in and out of the nucleus. Cell. 1999;99:677–690. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasquinelli A E, Ernst R K, Lund E, Grimm C, Zapp M L, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M L, Dahlberg J E. The constitutive transport element (CTE) of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) accesses a cellular mRNA export pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:7500–7510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portman D S, O'Connor J P, Dreyfuss G. YRA1, an essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene, encodes a novel nuclear protein with RNA annealing activity. RNA. 1997;3:527–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard C E, Fornerod M, Kasper L H, van Deursen J M. RAE1 is a shuttling mRNA export factor that binds to a GLEBS-like NUP98 motif at the nuclear pore complex through multiple domains. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:237–254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Seraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigues J P, Rode M, Gatfield D, Blencowe B J, Carmo-Fonseca M, Izaurralde E. REF proteins mediate the export of spliced and unspliced mRNAs from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1030–1035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031586198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saavedra C, Felber B, Izaurralde E. The simian retrovirus-1 constitutive transport element, unlike the HIV-1 RRE, utilises factors required for the export of cellular mRNAs. Curr Biol. 1997;7:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sachs A B, Bond M W, Kornberg R D. A single gene from yeast for both nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylate-binding proteins: domain structure and expression. Cell. 1986;45:827–835. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos-Rosa H, Moreno H, Simos G, Segref A, Fahrenkrog B, Panté N, Hurt E. Nuclear mRNA export requires complex formation between Mex67p and Mtr2p at the nuclear pores. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6826–6838. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seedorf M, Damelin M, Kahana J, Taura T, Silver P A. Interactions between a nuclear transporter and a subset of nuclear pore complex proteins depend on Ran GTPase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1547–1557. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seedorf M, Silver P A. Importin/karyopherin protein family members required for mRNA export from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8590–8595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segref A, Sharma K, Doye V, Hellwig A, Huber J, Luhrmann R, Hurt E. Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear mRNA export, binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 1997;16:3256–3271. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senger B, Simos G, Bischoff F R, Podtelejnikov A, Mann M, Hurt E. Mtr10p functions as a nuclear import receptor for the mRNA-binding protein Npl3p. EMBO J. 1998;17:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]