Abstract

We have characterized the role of YPR128cp, the orthologue of human PMP34, in fatty acid metabolism and peroxisomal proliferation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. YPR128cp belongs to the mitochondrial carrier family (MCF) of solute transporters and is localized in the peroxisomal membrane. Disruption of the YPR128c gene results in impaired growth of the yeast with the medium-chain fatty acid (MCFA) laurate as a single carbon source, whereas normal growth was observed with the long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) oleate. MCFA but not LCFA β-oxidation activity was markedly reduced in intact ypr128cΔ mutant cells compared to intact wild-type cells, but comparable activities were found in the corresponding lysates. These results imply that a transport step specific for MCFA β-oxidation is impaired in ypr128cΔ cells. Since MCFA β-oxidation in peroxisomes requires both ATP and CoASH for activation of the MCFAs into their corresponding coenzyme A esters, we studied whether YPR128cp is an ATP carrier. For this purpose we have used firefly luciferase targeted to peroxisomes to measure ATP consumption inside peroxisomes. We show that peroxisomal luciferase activity was strongly reduced in intact ypr128cΔ mutant cells compared to wild-type cells but comparable in lysates of both cell strains. We conclude that YPR128cp most likely mediates the transport of ATP across the peroxisomal membrane.

Peroxisomes are essential subcellular organelles involved in a variety of metabolic processes. Their importance is underlined by the identification of an increasing number of inherited diseases in man in which one or more peroxisomal functions are impaired (24, 40, 50). One of the main functions of peroxisomes is the degradation of fatty acids. In vertebrates, this takes place not only in peroxisomes but also in mitochondria. Long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) and medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) are oxidized in mitochondria, whereas very long-chain fatty acids and certain branched-chain fatty acids are first shortened in peroxisomes and subsequently oxidized to completion in mitochondria. This and other metabolic functions of peroxisomes (30, 40, 50) imply the existence of transport proteins in the peroxisomal membrane to shuttle metabolites from the interior of peroxisomes to the cytosol and vice versa. Indeed, several reports have appeared indicating the existence of such carrier proteins (11, 33, 34, 42, 43, 50).

We and others have been using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model organism to study the functions of peroxisomal membrane proteins (PMPs) for a number of reasons. First, in contrast to mammalian cells, peroxisomes in yeast are the sole organelles in which β-oxidation of fatty acids takes place (18). Second, S. cerevisiae is an easy organism to manipulate genetically, and its entire genome sequence is available to enable specific studies. Third, S. cerevisiae can use fatty acids as sole carbon source and therefore mutants disturbed in fatty acid β-oxidation can be readily identified by their growth characteristics in media supplied with different fatty acids.

In the last few years, much information has become available on peroxisomal membrane proteins involved in peroxisome biogenesis (7, 37, 39, 51). In contrast, there is very little information on the peroxisomal membrane proteins involved in metabolite transport. Earlier we reported the existence of two independent pathways for fatty acid transport across the peroxisomal membrane (11): one for the coenzyme A (CoA) esters of LCFAs, which is dependent on the peroxisomal ABC transporter proteins Pxa1p and Pxa2p as first identified by Shani and Valle (11, 33, 34, 38), possibly acting as acyl-CoA ester transporters (46), and one for MCFAs, which is dependent on the peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetase Faa2p and Pex11p (45).

In this paper we report on the S. cerevisiae orthologue of human PMP34 (53) and Candida boidinii PMP47 (23), YPR128cp, which is a member of the mitochondrial carrier family (MCF) of solute transporters, which includes carriers like the ADP/ATP carrier, the dicarboxylate carrier a.o (25). We show that YPR128cp is functionally involved in MCFA β-oxidation and peroxisome proliferation and we conclude that YPR128cp mediates the transport of ATP across the peroxisomal membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and culture conditions.

The wild-type strain used in this study was S. cerevisiae BJ1991 (matα leu2 trp1 ura3-251 prb1-1122 pep4-3 gal2). The fox1Δ and Pxa2Δ and faa2Δ mutants have been described before (11, 43). Yeast transformants were selected and grown on minimal medium containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (YNB-WO) (Difco) supplemented with 0.3% glucose and amino acids (20 μg/ml) as needed. Liquid rich media used to grow cells for DNA isolation, growth curves, subcellular fractionation, β-oxidation assays, immunogold electron microscopy, and enzyme assays were composed of 0.5% potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 0.3% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, and either 3% glycerol, 25 μM laurate, or 0.12% oleate–0.2% Tween 40, respectively. Before shifting to these media, the cells were grown on minimal 0.3% glucose medium for at least 24 h. Minimal oleate medium contains YNB-WO supplemented with all amino acids and 0.12% oleate plus 0.2% Tween 40.

Cloning, sequencing, and disruption of the YPR128c gene.

To construct ypr128cΔ deletion mutants, the entire YPR128c open reading frame was replaced by the kanMX4 marker gene (48). The PCR-derived construct for disruption comprised the kanMX4 gene flanked by short regions of homology (50 bp) corresponding to the YPR128c 3′ and 5′ noncoding regions. pKan was used as template with the YPR128c primers (5′-CTGCGTAAAAGTACAGACACCCTGGAAGCTAGGCCAAGATTGTTACGAGCATACATCACGTACGCTGCAGGTCGAC and 5′-CGATCAAGAGTTCAATGCCATTAACAAATATTTGAC TAC T T TCCATAC TG T TGG TGACAGATCGATGAAT TCGAGC TCG ). The resulting PCR fragments were introduced into S. cerevisiae wild-type BJ1991 cells and Pxa2Δ and faa2Δ mutant cells. G418-resistant clones were selected by growth on YPD plates containing G418 (200 mg/liter) (48).

Subcellular fractionation and Nycodenz gradients.

Subcellular fractionation was performed as described by Van der Leij et al. (41). Organelle pellets were layered on top of 15 to 35% Nycodenz gradients (12 ml), with a cushion of 1.0 ml of 50% Nycodenz solutions containing 5 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid, pH 6), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM KCl, and 8.5% sucrose. The sealed tubes were centrifuged for 2.5 h in a vertical rotor (MSE 8x35) at 19,000 rpm at 4°C. Gradients were analyzed for enzyme activity of various marker enzymes as described below. In addition, 150 μl of each fraction from the Nycodenz gradient was used for precipitation in a 2-ml Eppendorf tube together with 1,350 μl of 11% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). After being left overnight at 4°C, samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The pellet obtained was resuspended in 100 μl of Laemmli sample buffer and used for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Preparation of lysates.

Cells were harvested and washed twice in water, and lysates were prepared in a buffer containing 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol by disrupting the cells with glass beads on a vortex. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 1 min at 13,000 rpm in an Eppendorf centrifuge.

Western blotting.

Proteins were separated in SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 190 mM glycine, 20% methanol). Blots were blocked by incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The same buffer was used for incubation with primary antibodies and with immunoglobulin G (IgG)-coupled alkaline phosphatase. Blots were stained in buffer composed of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) and nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) following the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Mannheim).

Electron microscopy.

Oleate-induced cells were fixed with 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and 0.5% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde. Ultrathin sections were prepared as described by Gould and Valle (8).

NH epitope tagging and antibodies.

For epitope tagging of proteins, the NH epitope with the sequence MQDLPGNDNSTAGGS was used, which corresponds to the amino terminus of mature hemagglutinin protein and is recognized by a polyclonal antiserum. To introduce the NH tag, an oligonucleotide adaptor encoding the NH epitope was ligated into the SacI and BamHI sites of the single-copy catalase A (CTA1) expression plasmid as described by Elgersma et al. (4).

Enzyme assays.

β-Oxidation assays in intact cells were performed as previously described by Van Roermund et al. (44). Cells were grown overnight in media containing oleate to induce fatty acid β-oxidation. The β-oxidation capacity of wild-type cells grown on oleate in each experiment was taken as a reference (100%) and is expressed as the sum of CO2 and water-soluble β-oxidation products produced. Rates of oleate (C18:1) and laurate (C12:0) β-oxidation in cells grown on oleate were 12.1 ± 1.5 and 2.7 ± 0.6 nmol/h/mg of protein, respectively. The β-oxidation activity in lysates prepared from cells grown on oleate as measured with laurate as the substrate amounted to 12.1 ± 0.5 nmol/h/mg protein.

3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity was measured on a Cobas-Fara centrifugal analyzer by monitoring the acetoacetyl-CoA-dependent rate of NADH consumption at 340 nm (49). Fumarase activity was measured on a Cobas-Fara centrifugal analyzer monitoring the APADH production at 365 nm. The reaction was started with 10 mM fumarate in an incubation mixture of 100 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, 4 U of malate dehydrogenase (Boehringer) per ml, and 1 mM APAD for 5 min at 37°C. Luciferase activity was measured in intact cells and in lysates as described by Vieites et al. (47). Cultured cells were centrifuged, washed twice with distilled water, and resuspended in sterile water to be kept in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 4°C until used. Cells (3 × 106) were then diluted in 200 μl of oxygen-saturated 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5), and 25 μl of d-(−)luciferine (20 mM; final concentration, 2.2 mM) was added to the reaction chamber. The activity, measured as the peak light intensity in wild-type cells in each experiment, was taken as a reference (100%) (160 nV/cell). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method described by Smith et al. (35).

RESULTS

YPR128cp belongs to the MCF.

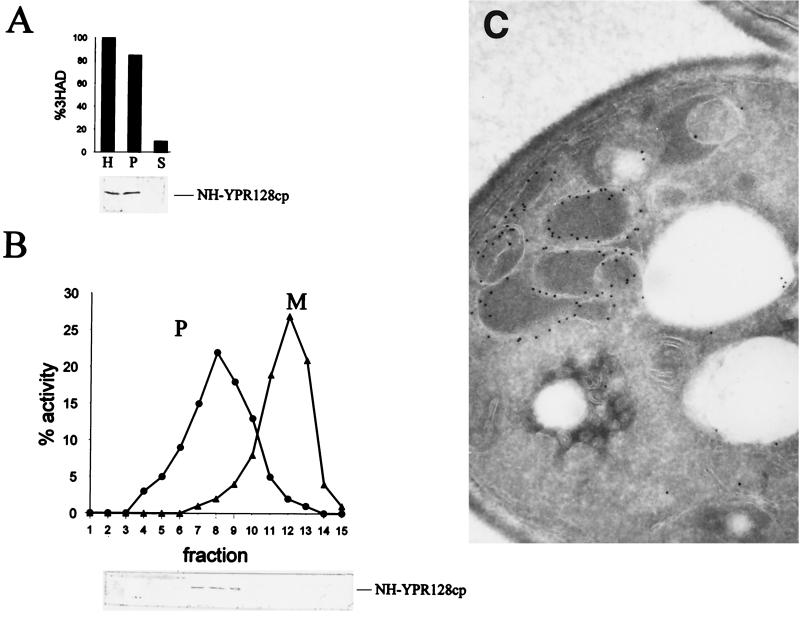

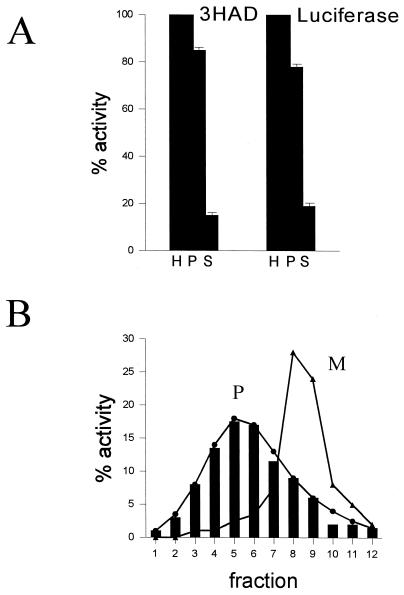

One of the predictions of our earlier studies (44) is that, by analogy with mitochondria, the peroxisomal membrane contains a variety of different transport proteins such as an ac(et)ylcarnitine carrier to shuttle acetylcarnitine and probably other carnitine esters produced in peroxisomes across the peroxisomal membrane. Similarly, a dicarboxylate carrier has been proposed to exist (42). We use S. cerevisiae as a model system to investigate this issue. Previously, Moualij et al. (25) reported 35 open reading frames encoding putative proteins belonging to the MCF in the yeast genome. Each member was characterized by the presence of six trans-membrane-spanning regions. The phylogenetic tree constructed by Moualij et al. can be subdivided into 27 subgroups, including the ADP/ATP, phosphate, citrate, dicarboxylate, acylcarnitine/carnitine, and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) carriers. In order to find proteins in this family that are peroxisomal, we inspected the putative promoter sequences of the 35 MCF genes for the presence of an oleate response element (consensus CGG-N14/N19-CCG [15, 31]). Of the 14 open reading frames thus identified, the products of six were localized by tagging the proteins at their N termini with the NH epitope (Table 1). Fractionation of homogenates prepared from cells expressing these NH-tagged MCF proteins and grown on oleate showed that all the NH-tagged versions were present in the organellar fraction (Fig. 1A). Subsequent fractionation of the organellar pellet by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation revealed that NH-YPR128cp cofractionated with the peroxisomal marker 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Fig. 1B), whereas the other NH-MCF proteins cofractionated with the mitochondrial marker (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Putative members of yeast MCF

| MCF membrane | Gene | ORFa | OREb (CGG---N14/N19---CCG) | Localization (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADP/ATP carrier | AAC1 | YMR056c | 786CGG---N17---CCG | Mitochondrial (1) |

| ADP/ATP carrier | AAC2 | YBL030c | 753CGG---N10---CCG | Mitochondrial (19) |

| ADP/ATP carrier | AAC3 | YBR085w | 428CGG---N13---CCG | Mitochondrial (17) |

| Graves' disease protein | YHR002w | ? | ||

| “Graves' disease protein” | YPR011c | Mitochondrial (NH tagged) | ||

| Member MCF | YNL083w | ? | ||

| Member MCF | YGR096w | ? | ||

| ADP/ATP carrier | YPR128c | 839CGG---N14---CCG | Peroxisomal (NH tagged) | |

| Phosphate carrier | MIR1 | YJR077c | 853CGG---N20---CCG | Mitochondrial (29) |

| RNA splicing protein | MRS3 | YJL133w | 153CGG---N15---CCG | Mitochondrial (52) |

| “RNA splicing protein” | MRS4 | YKR052c | Mitochondrial (52) | |

| “Tricarboxylate transport protein” | PET8 | YNL003c | ? | |

| Member MCF | YDL119c | ? | ||

| Member MCF | YHM1 | YDL198c | 649CGG---N18---CGG | Mitochondrial (NH tagged) |

| “Phosphate carrier” | YER053c | ? | ||

| Member MCF | YMR166c | ? | ||

| Member MCF | YGR257c | ? | ||

| Dicarboxylate carrier | DIC1 | YLR348c | 346CGG---N19---CCG | Mitochondrial (13) |

| “Uncoupling proteins” | OAC1 | YKL120w | 517CGG---N13---CCG | Mitochondrial (2) |

| “FAD carrier” | FLX1 | YIL134w | ? | |

| “FAD carrier” | YIL006c | ? | ||

| “FAD carrier” | YEL006w | ? | ||

| Member MCF | RIM2 | YBL192w | ? | |

| Carnitine carrier | CAC | YOR100c | 672CGG---N17---CCG | Mitochondrial (NH tagged) |

| Member MCF | ARG11 | YOR130c | Mitochondrial (3) | |

| Member MCF | YMC2 | YBR104w | Mitochondrial (20) | |

| Member MCF | YMC1 | YPR058w | 639CGG---N21---CCG | Mitochondrial (9) |

| “Citrate carrier” | YFR045w | ? | ||

| “Citrate carrier” | YPR021c | ? | ||

| “ADP/ATP carrier” | YOR222w | ? | ||

| “ADP/ATP carrier” | YPL134c | 675CGG---N18---CCG | Mitochondrial (NH tagged) | |

| Citrate carrier | CTP1 | YBR291c | Mitochondrial (14) | |

| Succinate-fumarate carrier | ACR1 | YJR095w | 686CGG---N19---CCG | Mitochondrial (NH tagged) |

| Member of protein machinery for MIM | YHM2 | YMR241w | 829CGG---N20---CCG | Mitochondrial (27) |

ORF, open reading frame.

ORE, oleate response element (CGG---N14/N19---CCG is the consensus sequence).

FIG. 1.

Identification of YPR128cp as a peroxisomal membrane protein in S. cerevisiae. (A) Subcellular fractionation of wild-type cells expressing NH-YPR128cp. Oleate-grown cells were fractionated by differential centrifugation of a homogenate (H) into a 17,000 × g pellet (P) and supernatant (S). The upper panel shows the activity of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (3HAD), a peroxisomal marker, whereas the lower panel shows the NH-YPR128cp fusion protein as detected on Western blot using an antibody against the NH tag. (B) The 17,000 × g pellet (P) was further fractionated by Nycodenz equilibrium density gradient centrifugation (fractions 1 to 15). Mitochondrial (M) and peroxisomal (P) matrix markers are fumarase (▴) and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (3HAD) (●), respectively (upper panel), and NH-YPR128cp was detected by immunoblot analysis (lower panel). (C) Immunogold electron micrograph showing association of NH-YPR128cp with the peroxisomal membrane. NH-YPR128cp was visualized using specific antibodies against the NH epitope and protein A-gold particles.

Immunogold electron microscopy of cross-sections of NH-YPR128cp-expressing-cells revealed exclusive labeling of the peroxisomal membrane (Fig. 1C). The identification of YPR128cp in the peroxisomal membrane is in line with recent data from Geraghty et al. (6).

Together, these results indicate that YPR128cp is a member of the MCF, but localized in the peroxisomal membrane. Based on sequence similarity, YPR128cp belongs to the subgroup of the ADP/ATP carriers within the MCF in S. cerevisiae (25). Highest sequence similarity was observed with the gene products of the Candida boidinii PMP47 gene, the Plasmodium falciparum adenine nucleotide translocase mRNA, and the human Pmp34 gene.

YPR128cp is required for growth on MCFAs.

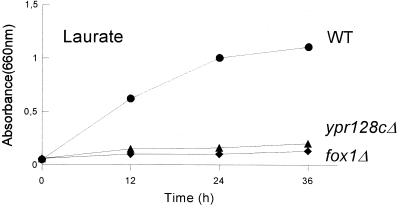

Deletion of the YPR128c gene did not affect growth on media containing glucose, acetate, or glycerol as a carbon source. Interestingly, growth on the LCFA oleate was also not affected, while growth in media supplemented with the (MCFA) laurate was impaired (Fig. 2). Since peroxisomal assembly mutants are not able to grow on oleate, the observation that deletion of the YPR128c gene still allows growth on oleate supports the assumption that YPR128cp is not involved in peroxisomal protein import. Rather, the specific growth defect on MCFA suggests that YPR128cp is required for a selective aspect of fatty acid metabolism, involving the β-oxidation of MCFAs.

FIG. 2.

Growth of wild-type and mutant cells on laurate. The strains shown are wild-type (WT), ypr128cΔ, and fox1Δ cells.

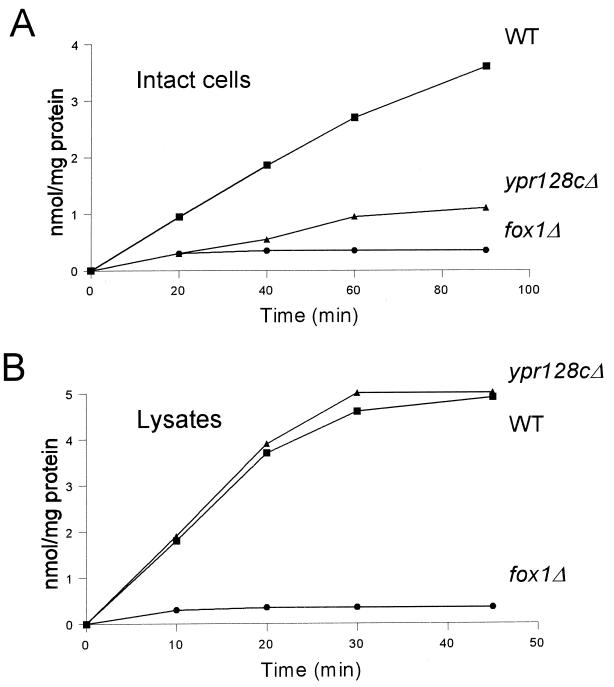

YPR128cp is involved in MCFA β-oxidation.

The capacity of wild-type and ypr128cΔ cells to metabolize fatty acids was investigated using radiolabeled fatty acids of varying chain length. The β-oxidation of LCFAs like oleate was normal in intact ypr128cΔ cells, while the oxidation of MCFAs like laurate was reduced compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, MCFA β-oxidation activity in lysates prepared from wild-type and ypr128cΔ cells was comparable (Fig. 3B). These results illustrate that the activity of the β-oxidation enzymes themselves is not affected in ypr128cΔ cells. This also implies that the capacity to transport CoA esters of LCFAs into or β-oxidation products out of peroxisomes is unaffected. In fact, these results strongly suggest that a transport step specific for MCFA β-oxidation is impaired in ypr128cΔ cells.

FIG. 3.

Lauric acid β-oxidation in oleate-induced wild-type (WT), ypr128cΔ, and fox1Δ cells. (A) β-Oxidation in intact cells. (B) β-Oxidation in cell lysates. [1-14C]lauric acid oxidation is expressed as the sum of [1-14C]CO2 and water-soluble β-oxidation products produced.

Earlier studies have indicated that a small fraction of LCFAs enter peroxisomes as free fatty acids, whereas most of the LCFAs are activated in the cytosol and rely on the heterodimeric ABC transporter Pxa1p/Pxa2p for entry into peroxisomes (11). Transport of MCFAs into peroxisomes occurs as free fatty acids and requires the active involvement of Pex11p (45). After transport, the activation into MCFA-CoA esters occurs by the peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetase (Faa2p) (11). Both Pex11p and Faa2p are located at the periphery of the peroxisomal membrane (21–23, 32, 45). Inside the peroxisomes, β-oxidation of both medium-chain and long-chain acyl-CoA esters is catalyzed by the same set of enzymes. Therefore, the MCFA-specific β-oxidation defect observed in ypr128cΔ cells suggests that YPR128cp functions in the Faa2p-dependent pathway.

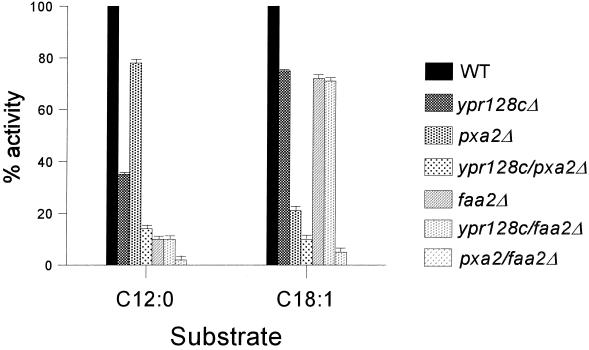

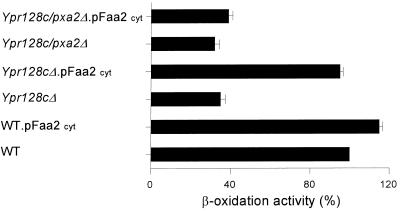

To further study the involvement of YPR128cp in a transport step specific for MCFA β-oxidation, double mutants were generated in which the YPR128c gene and the gene encoding Pxa2 or Faa2 were deleted (ypr128cΔ/Pxa2Δ and ypr128cΔ/faa2Δ). The cells were subsequently used to analyze the β-oxidation activity using radiolabeled MCFAs and LCFAs. ypr128cΔ/Pxa2Δ cells showed a block in both MCFA and LCFA β-oxidation activity (Fig. 4), whereas ypr128cΔ/faa2Δ cells were specifically disturbed in MCFA β-oxidation, which confirms that YPR128cp functions in the same fatty acid entry pathway as Faa2p and not in the Pxa2p-dependent pathway.

FIG. 4.

β-Oxidation activity measurements using fatty acids of different chain lengths. Cells grown on oleate medium were incubated with 1-14C-labeled MCFA (C12:0) or LCFA (C18:1), and β-oxidation rates were measured (see Materials and Methods). The β-oxidation rates in wild-type (WT) cells were taken as a reference (100%) and are expressed as the sum of [1-14C]CO2 and water-soluble β-oxidation products. Each experiment was performed at least two times, and the means are shown by error bars.

Based on these results, YPR128cp could be involved in the provision of the cofactors required for MCFA β-oxidation, in particular ATP and CoASH.

Evidence that YPR128cp and Faa2p are involved in the same pathway.

A possible function of YPR128cp would be the transport across the peroxisomal membrane of certain substrates required for MCFA β-oxidation or, more specifically, for the ATP-dependent conversion of MCFAs into their respective CoA esters by Faa2p. As peroxisomes readily lose their structural integrity upon isolation, we decided to test this possibility by an in vivo experiment in which we expressed Faa2p in the cytosol as previously reported (11, 45). If YPR128cp is required for specific transport of one of the substrates of Faa2p, the prediction would be that expression of Faa2p in the cytosol would result in active MCFA β-oxidation which is no longer solely dependent on the presence of YPR128cp. Instead, the MCFA β-oxidation will now become dependent on the presence of the peroxisomal ABC half-transporters Pxa1p and Pxa2p that will transport the CoA esters of the MCFAs produced by the cytosolic Faa2p into the peroxisomes.

To study this, we expressed an Faa2p version that lacks its peroxisomal targeting signal in ypr128cΔ cells, ypr128cΔ/Pxa2Δ cells, and wild-type cells and measured MCFA β-oxidation activity in cells grown on oleate medium. The results (Fig. 5) show that the mislocation of Faa2p to the cytosol rescues the MCFA β-oxidation defect observed in ypr128cΔ cells, as predicted. The observation that cytosolic Faa2p is not able to rescue the MCFA β-oxidation defect in YPR128cΔ/Pxa2Δ cells confirms the assumption that the cytosolically produced MCFA-CoA esters enter the peroxisomes via the Pxa1p/Pxa2p ABC transporter. From these experiments, we conclude that YPR128cp provides Faa2p with one of its substrates (ATP or CoASH), probably by facilitating substrate transport across the peroxisomal membrane.

FIG. 5.

Mislocalization of Faa2p to the cytosol complements the MCFA β-oxidation defect in ypr128cΔ cells. Cells were grown on oleate-containing medium and incubated with 1-14C-labeled laurate, and β-oxidation activity was measured (see Materials and Methods). The β-oxidation rates in wild-type (WT) cells were taken as the reference (100%) and are expressed as the sum of [1-14C]CO2 and water-soluble β-oxidation products. Each experiment was performed at least two times, and the means are shown by error bars.

Evidence that YPR128cp is an ATP carrier.

Since the sequence similarity of YPR128cp strongly suggested that it may serve as an ADP/ATP carrier, we used peroxisomal firefly luciferase to measure the ATP consumption within peroxisomes. The use of luciferase was introduced by Kennedy et al. (16) as an extremely sensitive method of monitoring free ATP in vivo at the subcellular level. To verify the experimental set-up, we first studied the subcellular localization of luciferase in transformed yeast cells grown under different conditions. Fractionation of homogenates prepared from wild-type and ypr128cΔ cells transformed with luciferase and grown on glucose showed that more than 90% of the luciferase activity was present in the organellar fraction (not shown), while approximately 75% of the activity was found in the organellar pellet of oleate-grown cells (Fig. 6A). Subsequent fractionation of the organellar pellets by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation showed that the luciferase activity cofractionated with the peroxisomal marker enzyme 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Fig. 6B), indicating that luciferase is completely located in peroxisomes, at least under conditions when its expression is relatively low.

FIG. 6.

Subcellular localization of luciferase in oleate-grown cells of S. cerevisiae transformed with the luciferase-SKL construct expressed under control of the CTA1 promoter (see Materials and Methods). (A) Luciferase-expressing wild-type cells were fractionated by differential centrifugation of a homogenate (H) into a 17,000 × g pellet (P) and supernatant (S), followed by the measurement of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (3HAD) and luciferase activity. (B) The 17,000 × g pellet (P) was further fractionated by Nycodenz equilibrium density gradient centrifugation (fractions 1 to 12). Mitochondrial (M) and peroxisomal (P) matrix markers are fumarase (▴) and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (3HAD) (●), respectively. Luciferase activity (solid bars) was measured in the fractions (see Materials and Methods).

Next, we measured the in vivo activity of luciferase in luciferase-expressing wild-type and ypr128cΔ cells, which were grown under different conditions. ypr128cΔ cells grown on glucose or oleate showed very little luciferase activity in contrast to wild-type cells (Fig. 7A). However, in lysates of these cells, luciferase activities were comparable (Fig. 7B). These results illustrate that the reduced activity of luciferase measured in intact ypr128cΔ.pLUC-skl cells is not due to a reduction in luciferase activity per se. In all cases the ypr128cΔ.pLUC-skl strain could be complemented with respect to the MCFA β-oxidation and luciferase activity by transforming the cells with the wild-type YPR128c gene, indicating that we specifically monitored the function of YPR128cp in living cells by measuring the luminescence produced by the intraperoxisomal luciferase. These data show that a transport step specific for both MCFA β-oxidation and luciferase activity is impaired in ypr128cΔ cells. The most likely explanation for the reduction in apparent activity of luciferase in ypr128cΔ cells would be a lowered intraperoxisomal ATP level as a consequence of the absence of YPR128cp. However, MCFA β-oxidation in peroxisomes also requires free CoASH. In order to rule out the possibility that YPR128cp is somehow involved in the provision of intraperoxisomal CoASH rather than of ATP, we tested the effect of CoASH on the activity of luciferase over a wide concentration range. This is especially important since firefly luciferase has a binding site for CoASH and affects light production by the enzyme. Importantly, Pazzagli et al. (28) have shown that CoASH has no effect on the peak light intensity but does have an effect on the integrated light production, since CoASH prevents the rapid inhibition of light production, producing a virtually constant production of light with time (see also Fig. 2 in reference 5). For these reasons we have measured peak light intensities rather than light production over a certain time scale in the experiment in Fig. 6, thereby eliminating the potential interference by CoASH. In separate experiments, we established that CoASH indeed had no effect on the peak light intensity produced by the enzyme, which leads us to conclude that YPR128cp is required for the transport of ATP and not CoASH (see Discussion).

FIG. 7.

YPR128cp is functionally involved in the transport of ATP. Luciferase activity was measured in vivo in luciferase-expressing wild-type (A) and ypr128cΔ (B) cells and in lysates. Cells were grown on 0.3% glucose and for different time periods on oleate. The luciferase activity in wild-type cells was taken as a reference (100%). Each experiment was performed at least two times, and the means are shown by error bars.

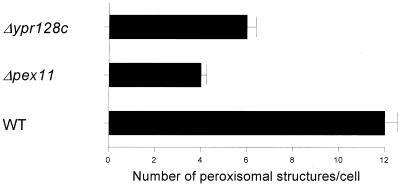

YPR128cp is also required for normal peroxisome proliferation.

In S. cerevisiae, the peroxisomal number and volume are regulated in response to changes in the carbon source of the growth medium. Cells grown on glucose contain only one or two small peroxisomes, whereas cells grown on oleate contain many more peroxisomes.

Since previous studies revealed that MCFA β-oxidation is required for peroxisomal proliferation (45), we also studied peroxisomal proliferation in ypr128cΔ cells during the transition from glucose- to oleate-containing medium using the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-based proliferation assay developed by Marshall et al. (22), which allows visualization of peroxisomal structures in living S. cerevisiae cells. For this purpose we expressed GFP containing a peroxisomal targeting signal type 1 AKL (GFP-PTS1) in wild-type, ypr128cΔ, and pex11Δ mutant cells.

We found that 3 h after a shift to oleate, the ypr128cΔ cells showed less peroxisomal structures per cell than wild-type cells (Fig. 8), which indicates that YPR128cp plays a role in a process that affects peroxisomal number or proliferation.

FIG. 8.

YPR128cp plays a role in the regulation of peroxisomal morphology and abundance in S. cerevisiae. Fluorescent structures labeled with GFP containing a peroxisomal targeting signal (GFP-PTS1) in various S. cerevisiae mutants. Cells were grown on oleate-containing medium for 3 h. The number and morphology of the peroxisomes were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. At least 100 cells were observed (in random fields) in each sample. Each experiment was performed at least two times, and the means are shown by error bars.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, several studies in the yeast S. cerevisiae have clearly shown that the peroxisomal membrane is not freely permeable to low-molecular-weight compounds but is a closed structure which requires the presence of carrier proteins in the peroxisomal membrane catalyzing the transport of specific metabolites. Indeed, we provided evidence for the existence of a dicarboxylate carrier in the peroxisomal membrane required for reoxidation of intraperoxisomal NADH (42) and a tricarboxylate carrier for the provision of intraperoxisomal NADPH (43). Furthermore, transport proteins have been shown to be involved in the import of fatty acids across the peroxisomal membrane, which may proceed via two distinct routes (11). The first route probably involves the transport of CoA esters of fatty acids as mediated by the two ABC half-transporters Pxa1p and Pxa2p, whereas the second route involves the transport of free fatty acids mediated by Pex11p, followed by the intraperoxisomal activation via the acyl-CoA synthetase Faa2p. LCFAs such as oleate are predominantly transported via the first route, whereas MCFAs are predominantly transported via the second route (11).

Several peroxisomal membrane proteins have been identified which may be involved in metabolite transport. One of these is YPR128cp, the orthologue of human PMP34 and C. boidinii PMP47, which is a member of the MCF of solute transporters, which includes the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier, the mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine carrier, and the mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier a.o. According to Moualij et al. (25), S. cerevisiae contains 35 proteins belonging to this family. In a search for peroxisomal carriers belonging to this family, we identified 14 proteins, the expression of which is controlled by an oleate response element. YPR128cp was the only one, however, which turned out to be peroxisomal. Since mitochondria are the ultimate site of reoxidation of NADH and degradation of acetyl-CoA (to CO2 and H2O), which are both produced during β-oxidation, it is not surprising that the expression of several mitochondrial carriers is also under the control of fatty acids via oleate response elements.

The studies described in this paper clearly show that YPR128cp plays a central role in the oxidation of MCFAs but not of LCFAs. This is concluded from the fact that ypr128cΔ cells failed to grow on lauric acid, whereas growth on oleate-containing medium was normal. Similar characteristics have previously been reported for the faa2Δ strain (11). Additional evidence for the concept that YPR128cp and Faa2p both function in MCFA oxidation came from experiments with double mutants. Indeed, the double mutant ypr128cΔ/faa2Δ showed impaired oxidation of laurate but not of oleate, whereas the double mutant ypr128cΔ/Pxa2Δ was disturbed in both laurate and oleate oxidation.

There are several options for the function of YPR128cp. The first would be transport of medium fatty acids per se. Model studies with artificial membranes, however, have shown that free fatty acids of short- and medium-chain length can diffuse very fast from one leaflet of the membrane to the other (10). According to these authors, the short- and medium-chain fatty acids would rapidly traverse the peroxisomal membrane, followed by their activation to a CoA ester as catalyzed by Faa2p. Based on these considerations, a role of YPR128cp in the provision of ATP and/or CoASH, both required for activation of MCFAs in the peroxisomal interior, would be more logical.

Making use of the elegant system developed by Kennedy et al. (16), which is based on the use of luciferase as a sensitive indicator of the concentration of ATP, we have now obtained experimental evidence suggesting that YPR128cp indeed functions as a carrier of ATP. This is concluded from the fact that the apparent activity of intraperoxisomal luciferase was found to be strongly deficient in YPR128cΔ cells. Since luciferase catalyzes an ATP-dependent reaction, these data indicate that the intraperoxisomal level of ATP is reduced in YPR128cΔ cells. The most likely explanation for this finding is that YPR128cp catalyzes the transmembrane transport of ATP.

The luciferase system that we used does not allow one to study whether YPR128cp is an ATP uniporter or an exchanger, with ATP being imported and ADP or AMP being exported from peroxisomes. This matter can only be resolved if YPR128cp is expressed in artificial liposomes, as has been done, for instance, for the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (36) and the carnitine/acylcarnitine carrier (12). Such experiments are now in progress. Recently, a paper by Nakagawa et al. (26) described the involvement of the YPR128cp orthologue PMP47 from C. boidinii in the metabolism of MCFAs. In their paper the authors speculate about a possible function of PMP47 in the transport of ATP based on the sequence similarity of PMP47 to ADP/ATP carriers. In contrast to the work presented in this paper, however, no experimental data were presented to provide evidence for this postulate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephen Gould for GFP-PTS1 constructs and G. E. Mochtar for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian G S, McCammon M T, Montgomery D L, Douglas M G. Sequences required for delivery and localization of the ADP/ATP translocator to the mitochondrial inner membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:626–634. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colleaux L, Richard G F, Thierry A, Dujon B. Sequence of a segment of yeast chromosome XI identifies a new mitochondrial carrier, new member of the G protein family, and a protein with the PAAKK motif of the histones. Yeast. 1992;8:325–336. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabeel M, Soetens O, De Rijcke M, Pratawi R, Pankiewicz R. The ARG11 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes a mitochondrial integral membrane protein required for arginine biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25011–25018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.25011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elgersma Y, Vos A, van den Berg M, van Roermund C W T, van der Sluijs P, Distel B, Tabak H F. Analysis of the carboxy-terminal peroxisomal targetting signal 1 in a homologous context in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26375–26382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford S R, Buck L M, Leach F R. Does the sulfhydryl or the adenine moiety of CoA enhance firefly luciferase activity? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1252:180–184. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00150-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geraghty M T, Bassett D, Morell J C, Gatto G J, Jr, Bal J, Geisbrecht B V, Heiter P, Gould S J. Detection patterns of protein distribution and gene expression in silico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2937–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Gould S J, Keller G A, Schneider M, Howell S M, Garrard L, Goodman J M, Distel B, Tabak H F, Subramani S. Peroxisomal protein import is conserved between yeast, insects and mammals. EMBO J. 1990;9:85–90. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould S J, Valle D. Peroxisomal biogenesis disorders: genetics and cell biology. Trends Genet. 2000;16:340–345. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graf R, Baum B, Braus G H. YMC1, a yeast gene encoding a new putative mitochondrial carrier protein. Yeast. 1993;9:301–305. doi: 10.1002/yea.320090310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton J A, Kamp F. How are free fatty acids transported in membranes? Is it by proteins or by free diffusion through the lipids? Diabetes. 1999;48:2255–2269. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.12.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hettema E H, Van Roermund C W T, Distel B, Van den Berg M, Vilela C, Roderigues-Pousada C, Wanders R J A, Tabak H F. The ABC transporters Pat1 and Pat2 are required for import of long-chain fatty acids into peroxisomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1996;15:3813–3822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indiveri C, Iacobazzi V, Giangregorio N, Palmieri F. Bacterial overexpression, purification, and reconstruction of the carnitine/acylcarnitine carrier from rat liver mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:589–594. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakhniashvilli D, Mayor J A, Gremse D A, Xu Y, Kaplan R S. Identification of a novel gene encoding the yeast mitochondrial dicarboxylate transport protein via overexpression, purification, and characterisation of its protein product. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4516–4521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan R S, Mayor J A, Gremse D A, Wood D O. High level expression and characterisation of the mitochondrial citrate transport protein from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4108–4114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpichev I V, Small G M. Global regulatory functions of Oaf1p and Pip2p (Oaf2p), transcription factors that regulate genes encoding peroxisomal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6560–6570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy H J, Pouli A E, Ainscow K E, Jouaville L S, Rizzuto R, Rutter G A. Glucose generates sub-plasma membrane ATP microdomains in single islet β-cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13281–13291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolarov J, Kolarova N, Nelson N. A third ADP/ATP translocator gene in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12711–12716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunau W H, Dommes V, Schulz H. Beta-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, peroxisomes, and bacteria; a century of continued progress. Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34:267–342. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawson J E, Douglas M G. Separate genes encode functionally equivalent ADP/ATP carrier proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation and analysis of AAC2. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14812–14818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannhaupt G, Stucka R, Ehnle S, Vetter I, Feldman H. Analysis of a 70 kb region on the right arm of yeast chromosome II. Yeast. 1994;10:1363–1381. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall P A, Krimkevich Y, Lark R, Dyer J M, Veenhuis M, Goodman J M. Pmp27 promotes peroxisomal proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:345–355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall P A, Dyer J M, Quick M E, Goodman J M. Redox-sensitive homodimerisation of Pex11p: a proposed mechanism to regulate peroxisomal division. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:123–137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCammon M T, Dowds C A, Orth K, Moomaw C R, Slaughter C A, Goodman J M. Sorting of peroxisomal membrane PMP47 from Candida boidinii into peroxisomal membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20098–20105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser H W, Bergin A, Cornblath D. Peroxisomal disorders. Biochem Cell Biol. 1991;69:463–474. doi: 10.1139/o91-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moualij B E, Duyckaerts C, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Sluse F E. Yeast functional analysis reports. Yeast. 1997;13:573–581. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199705)13:6<573::AID-YEA107>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa T, Imanaka T, Morita M, Ishiguro K, Yurimoto H, Yamashita A, Kato N, Sakai Y. Peroxisomal membrane protein PMP47 is essential in the metabolism of middle-chain fatty acid in yeast peroxisomes and is associated with peroxisome proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3455–3461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulsen I T, Sliwinski M K, Nelissen B, Goffeau A, Saier M H. Unified inventory of established and putative transporters encoded within the complete genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pazzagli M, Devine J H, Peterson D O, Baldwin T O. Use of bacterial and firefly luciferases as reporter genes in DEAE-dextran-mediated transfection of mammalian cells. Anal Biochem. 1992;204:315–23. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phelps A, Schobert C T, Wohirab H. Cloning and characterisation of the mitochondrial phosphate protein gene from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1991;30:248–252. doi: 10.1021/bi00215a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy K J, Mannaerts G P. Peroxisomal lipid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:343–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.002015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rottensteiner H, Kal A J, Binder M, Hamilton B, Tabak H F, Ruis H. Pip2p: a transcriptional regulator of peroxisome proliferation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1996;15:2924–2934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakai Y, Saiganji A, Yurimoto H, Takabe K, Saiki H, Kato N. The absence of PMP47, a putative yeast peroxisomal transporter, causes a defect in transport and folding of a specific matrix enzyme. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:37–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shani N, Watkins P A, Valle D. PXA1, a possible Saccharomyces cerevisiae ortholog of the human adrenoleukodystrophy gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6012–6016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shani N, Valle D. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the human adrenoleukodystrophy transporter is a heterodimer of two half ATP-binding cassette transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11901–11906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streicher-Scott J, Lapidus R, Sokolove P M. The reconstituted mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocator: effects of lipid polymorphism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;315:548–554. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subramani S. Components involved in peroxisome import, biogenesis, proliferation, turnover, and movement. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:171–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swartzman E E, Viswanathan M N, Thorner J. The PAL1 gene product is a peroxisomal ATP-binding cassette transporter in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:549–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabak H F, Braakman I, Distel B. Peroxisomes: simple in function but complex in maintenance. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:447–453. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van den Bosch H, Schutgens R B H, Wanders R J A, Tager J M. Biochemistry of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:157–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van der Leij I, Van der Berg M, Boot R, Franse M M, Distel B, Tabak H F. Isolation of peroxisome assembly mutants from Saccharomyces cerevisiae with different morphologies using a novel positive selection procedure. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:153–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Roermund C W T, Elgersma Y, Singh N, Wanders R J A, Tabak H F. The membrane of peroxisomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is impermeable to NAD(H) and acetyl-CoA under in vivo conditions. EMBO J. 1995;14:3480–3486. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Roermund C W T, Hettema E H, Kal A J, van den Berg M, Tabak H F, Wanders R J A. Peroxisomal β-oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidence for an isocitrate/2-oxoglutarate NADP redox shuttle. EMBO J. 1998;3:677–687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Roermund C W T, Hettema E H, Van den Berg M, Tabak H F, Wanders R J A. Molecular characterization of carnitine-dependent transport of acetyl-CoA from peroxisomes to mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and identification of a plasma membrane carnitine transporter, Agp2p. EMBO J. 1999;18:5843–5852. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Roermund C W T, Tabak H F, Van den Berg M, Wanders R J A, Hettema E H. Pex11p plays a primary role in medium-chain fatty acid oxidation, a process that affects peroxisomal number and size in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:489–497. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verleur N, Hettema E H, van Roermund C W T, Tabak H F, Wanders R J A. Transport of activated fatty acids by the peroxisomal ATP-binding-cassette transporter Pxa2 in a semi-intact yeast cell system. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:657–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vieites J M, Navarro-Garcia F, Prez-Diaz R, Pla J, Nombela C. Expression and in vivo determination of firefly luciferase as gene reporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1321–1327. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wach A. Yeast functional analysis reports. Yeast. 1996;12:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wanders R J A, IJlst L, Poggi F, Bonnefont J P, Munnich A, Brivet M, Rabier D, Saudubray J M. Human trifunctional protein deficiency: a new disorder of mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188:1139–1145. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91350-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wanders R J A, Schutgens R B H, Barth P G. Peroxisomal disorders: a review. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:726–739. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterham H R, Cregg J M. Peroxisome biogenesis. Bioessays. 1997;19:57–66. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiesenberger G, Link T A, Ahsen U, Waldherr M, Schweyer R J. MRS3 and MRS4, two suppressors of mtRNA splicing defects in yeast, are new members of the mitochondrial carrier family. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:23–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wylin T, Baes M, Brees C, Mannaerts G P, Fransen M, Van Veldhoven P. Identification and characterisation of human PMP34, a protein closely related to the peroxisomal integral protein PMP47 of Candida boidinii. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:332–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]