Abstract

Background:

Media exposure which was traditionally restricted only to television has now broadened to include various handheld devices and constant internet access. Although high quality educational and interactive screen time is beneficial, excessive addiction and early introduction of such media use has various deleterious consequences.

Aim:

To estimate the exposure of media among Indian children and its influence on early child development and behaviour.

Settings and Design:

A tertiary care hospital based cross-sectional study.

Materials and Methods:

We included 613 children between 18 months and 12 years who visited the paediatric out-patient department for a well or a sick visit. Their media exposure was extensively analysed along with Problematic Media Use Measure Short Form (PMUM-SF). They were screened for behaviour problems using the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) accordingly. Those under five years were also subjected to a screening using Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ3).

Results:

The most common gadget used was television followed immediately by smartphones. The average daily screen time was 2.11 hours, Mean+SD=2.11+1.53, 95% CI 2.11+ 0.12, found in (40.1%) of the study population. The prevalence of screen addiction was 28.1%, majority being boys. Increased screen time and media addiction were significantly associated with concerns in communication, problem-solving and personal-social domains, as well as conduct, hyperactivity and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) problems.

Conclusion:

We conclude that media exposure among children should be enquired as a routine. This helps to curtail unhealthy digital media practices at the earliest to ensure a digital safe environment for children.

Keywords: Behavior, development, problematic media

Digital media has undergone an explosive revolution since the introduction of smartphones in 2007. It has virtually conquered the lives of children, with the advent of easily portable gadgets (smartphones and tablets) and instantly available internet access. The first 5 years of life are crucial for critical brain development, and they lay the foundation for socio-emotional relationships, as well as healthy habits.[1] Excessive screen use has negative influences in the various domains of development[2] and also causes behavioral problems among preschoolers as well as school-going children which may persists as the child grows older.[3] In our Indian population, there is a paucity of data on the burden of the latest digital media gadget exposure among children and its harmful effects. Although there are studies on problematic media use among adolescents, such data are meager among children. Hence, this study was conducted to estimate the exposure of digital media devices among children, its association with early child development, and behavior as well as media addiction. The true estimate of the quantity of media exposure among children will pave way for policy-makers of the country to come up with media guidelines which would be appropriate for the child and the family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in the pediatric outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital, from October 2019 to April 2020. The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee, and a detailed informed consent was obtained from the parents in the local regional language.

Inclusion criteria

This includes all children who attended the pediatric outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in Chennai for a well or sick visit in the age group between 1½ years and 12 years.

Exclusion criteria

Children with an acute illness requiring hospitalization

Children not residing with parents

Children with established developmental delays due to cerebral palsy, genetic or metabolic conditions

Children already diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorders (ODD), and conduct disorders.

The sample size was calculated with media use among children being around 72% in previous studies. The margin of error was kept as 5%, the confidence interval (CI) as 95% and the sample size was estimated to be 598. Considering the possibility of 10% nonresponders, 658 participants were approached among whom 613 responded to the questionnaire. The categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. The quantity variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the baseline characteristics. The group comparisons for the categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was carried out using the statistical software SPSS software (2008, version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

We developed a questionnaire in English consisting of 43 items based on various studies on media use among children [Refer Supplement].[4,5] The senior faculty of the department determined the questionnaire to have face validity; however, it was not tested for reliability. Age was divided into two groups: (1) 1.5 years–5 years and (2) >5–12 years. Gender, nutritional status, socioeconomic status, and type of family were noted.

Duration of media exposure was noted for weekdays and weekends separately, for gadgets such as television (TV), mobile, laptop/computer, videogame, and other devices if specified. Response options were graded as (a) 0 h-no media exposure at all, (b) <30 min per day, (c) >30 min but <1 h per day (d) approximately 1–2 h per day (e) 2–3 h per day approximately (f) >3 h per day. To calculate the approximate minutes per hour engaged in screen time, options “b” and “c” were equated to 0.5 h, option “d” to 1.5 h, option “e” to 2.5 h and option “f” to 3.5 h per day.[6] The total duration of screen time was calculated as follows:

Total screen exposure of the child was calculated by adding the duration of response options for all the gadgets.[7] Screen time of >2 h per day was considered as “excessive” based on studies done in the past.[8,9]

Parents were asked about co-viewing media with their child, the response options being (a) always alone, (b) always with parent, and (c) partly. The background TV use while doing homework was also asked. Media multitasking was asked as “How often, if ever, does your child like to use more than one type of media at a time, for example, play a handheld game while he/she is watching TV or listening to music while he/she is using the computer?” Response options were (a) most of the time, (b) sometimes, (c) only once in a while, and (d) never. To estimate the age at which children were first exposed to TV/mobile we asked parents, “To the best of your recollection, at what age did your child begin to regularly watch TV/mobile?” The response was graded as (a) <1 year, (b) 1 year, (c) 2 years, (d) 3 years, (e) 4 years, (f) never used, and (g) recent in last 1–2 years. Child's ownership of a media gadget, content and the modes used to access it were asked.[10] The child's ability to navigate mobile phone devices was asked as “Does your child need help to use your mobile?”[10] The maximum duration that children would spend using mobile in a single setting was asked as “In one sitting, how many minutes does your child typically play with a mobile device? options given were (a) <5 min, (b) 5–10 min, (c) 11–20 min, and (d) >20 min. Parents were also asked about the various reasons for letting their child use mobile as well as when their child would typically stop playing on mobile phone devices. A detailed probe regarding the YouTube usage of children, if they use the main YouTube or the one designed for kids under 5 was also asked.[5]

To estimate parental use of media, we asked mothers to indicate their own media use duration and divided it as >5 h and ≤5 h.[7] They were also asked how frequently they read books to their child with responses given as (a) Never, (b) less than once a month, (c) once or twice a month, (d) once a week, (e) several times a week, and (f) daily.[11] It was decided to ask only mothers and not fathers, as studies done in the past found associations between maternal media use and child's media use as well as its correlation with behavioral difficulties among children.[7,11]

The BEARS questionnaire was used to identify sleep problems in preschool children. The tool's acronym represents bedtime issues, excessive day time sleepiness, night awakenings, regularity and duration of sleep, and snoring.[12] The Problematic Media Use Measure Short Form (PMUM–SF) was used to estimate the screen addiction among children of our entire study population. It consists of nine items. The responses to each item were based on a five-point Likert scale as (1) never, (2) seldom, (3) sometimes, (4) often, and (5) always. Children who obtained a score of three and above in five or more questions were considered to have problematic media use/addiction.[11] The developmental screening test, Ages and Stages Questionnaire 3rd edition was used to screen children in the age group between 1½ years and 5 years.[13] Child Behavior Checklist was used to screen behavior problems among children up to 5 years of age. Children were categorized “normal,” “borderline clinical range,” and “clinically significant problems.”[14] Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scale was used in our study to screen for behavior problems in children beyond 5 years of age up to 12 years. The scores for the problem behavior items and strengths are categorized according to the new 4-band as (a) close to average, (b) slightly raised (or slightly lowered), (c) high (or low), and (d) very high (or very low).[15]

RESULTS

We invited 658 participants for our study and around 613 parents responded to the questionnaire. We analyzed 348 children in the age group of 1.5 years to 5 years and 265 children in the age group beyond 5 years and 12 years. The demographic data of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population

| Age (years) | Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age-wise distribution of gender of the study participants | ||

| 1.5-5 | 188 (55.13) | 160 (58.82) |

| >5-12 | 153 (44.87) | 112 (41.18) |

| Economic status of the study population# | ||

| Upper | 96 (15.70) | |

| Upper middle | 232 (37.80) | |

| Lower middle | 225 (36.70) | |

| Upper lower | 49 (8.00) | |

| Lower | 11 (1.80) | |

| Employment of parents | ||

| Father only employed | 399 (65.10) | |

| Mother alone employed | 13 (2.10) | |

| Both parents employed | 201 (32.80) | |

| Type of family | ||

| Nuclear family | 388 (63.30) | |

| Joint family | 225 (36.70) | |

#Modified Kuppusamy’s scale

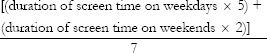

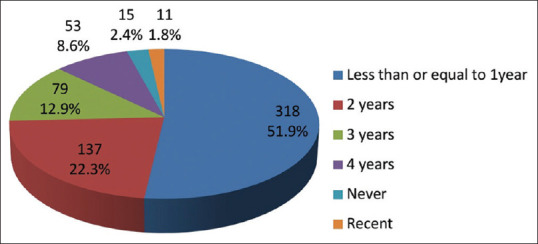

Out of 613 children in our study population, the majority of them (n = 580, 94.6%) viewed TV either alone or in combination with other devices. TV alone was viewed by 52 children (9.0%). The most common combination was TV and mobile viewed by 392 children (67.6%). Sixty children in our study population did not use mobile phones. Most of our children used two gadgets overall (65.1%), and the majority had no gadgets in their bedroom (n = 427, 69.65%). We found that the average daily screen time of the study population was 2.11 h [Table 2]. Our children predominantly started to use gadgets such as TV and mobile phones within the 1st year of life [Figures 1 and 2]. Most of our children (n = 583, 95.1%) had co-viewing of media with their parents or primary caregiver either at all times or partly. TV use in the background and media multitasking were absent in the majority of our children accounting to 85% and 81.2%, respectively.

Table 2.

Screen time of the study population and other media variables

| Screen time (h) | Mean±SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Screen time of the study population | ||

| Weekdays | 9.41±7.94 | 8.78-10.03 |

| Weekend | 5.35±3.87 | 5.05-5.65 |

| Average | 2.11±1.53 | 2.23-1.99 |

|

| ||

| Distribution of average screen time | ≤2 h, n (%) | >2 h, n (%) |

|

| ||

| n (%) | 367 (59.90) | 246 (40.10) |

|

| ||

| Other media variables | Present, n (%) | Absent, n (%) |

|

| ||

| Co-viewing | 583 (95.10) | 30 (4.90) |

| Television use in the background | 92 (15.00) | 521 (85.00) |

| Media multitasking | 115 (18.80) | 498 (81.20) |

CI Confidence interval; SD Standard deviation; n - Number of children

Figure 1.

Pie chart showing age at the first use of Television by children in the study

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing age at the first use of smartphones by children in the study

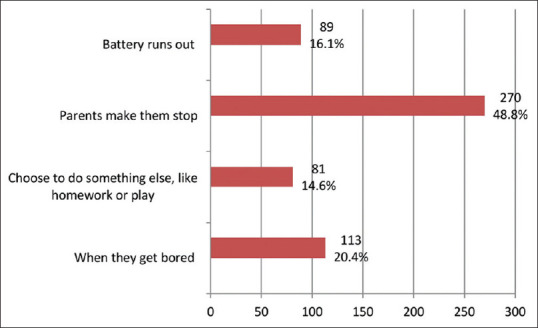

We found that 47% of children (n = 288) viewed gadgets for both education and entertainment. Out of the 553 children who used mobile phones, a majority of them (68.4%, n = 378) did not require any help to use the gadget. We observed that most of the children in our study (65.6%, 363/553) viewed smartphones >20 min in one sitting. Children had to be forced to stop mobile use in nearly half the cases [Figure 3]. Reason for parents to give smartphones to their children was predominantly for entertainment among 65.1% (n = 360) and for mealtime in 27.3% (n = 151) of the children. Majority of our children viewed the YouTube application instead of the website.

Figure 3.

Bar diagram showing reason for children to stop mobile phone use

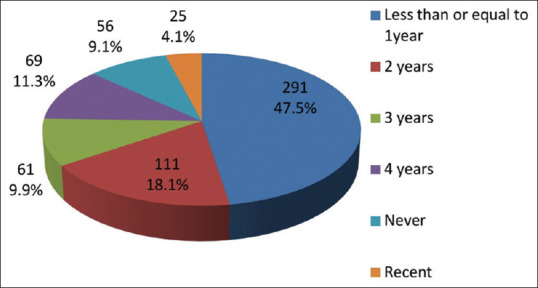

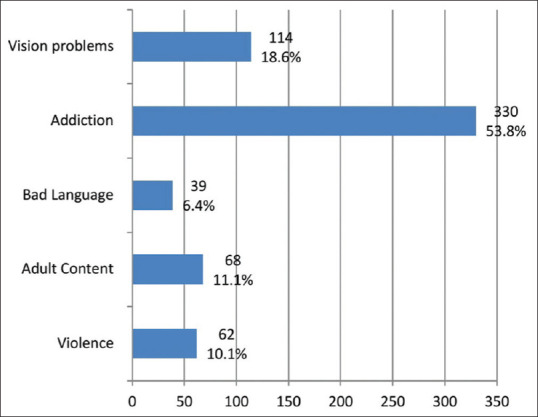

The average screen time of various types of media used by mothers was estimated as 1.89 h (mean ± SD = 1.89 ± 1.49, 95% CI 1.89 ± 0.12). Around 66.6% (n = 408) of the mothers said that they never read books to their children. The box and whisker chart depicting the average screen time of mothers (left) and children (right) is shown in Figure 4. The (+) represents the mean, the dark horizontal line denotes the median, and the values within the box represent the inter-quartile range. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the inter-quartile range and outliers are beyond whiskers. The distribution of screen time among parents and children had predominant overlap and was similar. Parents were also asked on their cause of concern regarding their child's media use [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Box and Whisker plot showing excessive screen time of mothers and children in the study

Figure 5.

Bar diagram showing parental concern on media use

The prevalence of addiction in our study as estimated by PMUM-SF was found to be 28.1%, of which boys constituted the majority being around 66.3% and girls 33.7%. We found that in both the age groups of our study, boys had more media addiction than girls and this was statistically significant. The item with the highest mean (M = 2.20) and the highest rating as “always” was “It is hard for my child to stop using screen media.” Tables 3 and 4 show the association of increased screen time and media addiction with various domains of development. Increased screen time of >2 h and media addiction were associated with clinically significant pervasive developmental disorder problems and ADHD problems which reached statistical significance in the under-five age group. The other domains such as affective problems and ODD were associated with increased screen time and media addiction, respectively.

Table 3.

Ages and Stages Questionnaires and screen time

| Average daily screen time (h) | Normal, n (%) | Monitoring zone, n (%) | Refer, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASQ communication and average screen time | ||||

| <2 | 186 | 7 (36.8) | 18 (42.9) | <0.001* |

| >2 | 101 | 12 (63.2) | 24 (57.1) | |

| ASQ personal social and average screen time | ||||

| <2 | 199 | 4 (25) | 8 (25) | <0.001* |

| >2 | 101 | 12 (75) | 24 (75) | |

| ASQ problem solving and average screen time | ||||

| <2 | 184 | 14 (60.9) | 13 (33.3) | <0.001* |

| >2 | 102 | 9 (39.1) | 26 (66.7) |

*Chi-square test. ASQ Ages and Stages Questionnaires

Table 4.

Ages and Stages Questionnaires and problematic media use measure addiction

| PMUM addiction | Normal, n (%) | Monitoring zone, n (%) | Refer, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASQ communication and PMUM addiction | ||||

| Yes | 59 | 11 (57.9) | 24 (57.1) | <0.001* |

| No | 228 | 8 (42.1) | 18 (42.9) | |

| ASQ personal social and PMUM addiction | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 9 (56.2) | 19 (59.4) | <0.001* |

| No | 234 | 7 (43.8) | 13 (40.6) | |

| ASQ problem solving and PMUM addiction | ||||

| Yes | 60 | 11 (47.8) | 23 (59.0) | <0.001* |

| No | 226 | 12 (52.2) | 16 (41) |

*Chi-square test. PMUM Problematic media use measure; ASQ Ages and stages questionnaires

Among children older than 5 years of age increased screen time of >2 h was associated with conduct and hyperactivity problems. Media addiction was associated with statistically significant behavioral problems and low prosocial behavior in all the SDQ scales. We found that when children co-viewed media with adults, they showed age-appropriate development in communication and personal-social domains which was statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed 348 children in the age group of 1½ years to 5 years and 265 children in the age group beyond 5 and 12 years. We did not find any differences with regard to behavioral problems or screen media addiction based on gender or type of family. However, boys were found to have more inattention and aggressiveness compared to girls as observed by Tamana et al.[3] TV was found to be the most common device used by children either alone or in combination (94.6%) followed by smartphones (90.2%). Similarly, TV was the predominant gadget used by children in a recent study done by Domingues-Montanari et al.,[16] whereas it was smartphones as observed by Khiu and Hamzah among Malaysian preschoolers.[17] The reason for the traditional TV use, to be still predominant in our study could be attributed to the excessive use of TV by older adults, thereby predisposing exposure among children.

Previous studies found an increased risk of sleep problems among children who have media devices in their bedroom. This was attributed to the suppression of melatonin by the blue light emitted from gadgets, the delay in sleep onset, more violent content at night, and media displacing soothing bedtime routines.[18,19] There were no sleep problems in 69.65% of our study population and no bedroom gadgets as well. This was higher than that observed by Asplund et al. where they reported that 56% of their study group had no bedroom gadgets.[20] Children in the under-five age group, who had co-viewing of media with adults showed age-appropriate development in various domains such as communication, personal social, and problem-solving. This was supported by Samudra et al. who also found that co-viewing of educational media greatly improves children's vocabulary.[21]

The prevalence of excessive screen time in our study was found to be 40.1% which was similar to the observation made by Khiu and Hamzah.[17] There was a gender-based difference on excessive screen time in our study where the prevalence among boys was 60.6% and 39.4% among girls, which was also observed by Carson et al.[22] Similar to our observation, Kabali et al. found that most children (92.2%) started using mobile devices before 1 year of age.[10]

PMUM scale was done to estimate problematic media use in children which indicates the use of media to the extent of causing a disturbance in the functioning of the individual and not merely the excessive hours of use alone.[11,23] The prevalence of addiction in our study across all ages as estimated by PMUM was found to be 28.1%, of which boys constituted 66.3%. Studies done on problematic smartphone use alone showed that the prevalence rate among children and adolescents can vary widely between 5% and 50%.[24,25] Children identified to have problematic media use or addiction by PMUM, scored below the cutoff in developmental domains such as communication, personal social, and problem-solving, thereby requiring referral for definitive developmental assessment. Such children also had behavioral problems. As there are no studies on PMUM which looked at developmental effects of media addiction, our data could not be compared.

We found that children with excessive screen time of > 2 h had parental concerns in communication, problem-solving, and personal-social development. This was supported by Lin et al. who observed that increased screen time was significantly associated with a delay in cognition, language, and motor milestones.[26] Radesky et al. found that toddlers had concerns in social-emotional development when parents used digital media gadgets as a coping strategy to calm the child.[27] Studies have also found that cognition domain of children improve when screen time was limited to < 2 h per day.[28] Our observation of behavioral problems among children with increased screen time was supported by various cross-sectional and longitudinal studies which found that children with excessive TV use had significant ADHD problems.[29,30] Poulain et al. found that preschoolers media use and their behavioral problems were mutually related over time. Their baseline computer use predicted conduct and emotional problems at follow-up, whereas baseline use of smartphones predicted hyperactivity and conduct problems at follow-up.[31]

The strengths of this study include the large sample size based on the Indian population. Ours is also the first study to analyze addictive media use among children < 12 years of age in India using the PMUM-SF and the effect of media addiction on development in young children. There were certain limitations in our study. Ours being a cross-sectional study, there is a possibility of the association being bidirectional, and therefore, cause and effect cannot be ascertained. Thus, longitudinal studies are required to draw definite conclusions which can have ethical concerns with the current knowledge. Since the data were based on parental reports, there is a chance of social desirability bias and recall bias. Our results may not apply to rural population and those with less access to digital gadgets. Although our study focused on the addictive nature of media use among children, the other patterns of problematic media use such as antisocial behaviors, pathological gaming, etc., were not studied probably because of the age group selected. Media is used as a platform for education during the current COVID-19 lockdown. This calls for further studies on digital learning. We conclude that pediatricians should look into media use among children in their regular visit as it has implications for development and behavior. Since there are no Indian recommendations on media use for children, policymakers should formulate guidelines on permissible and healthy screen exposure on basis of further research to safely enhance digital literacy.

What is already known?

Excessive duration of media use negatively affects early child development and causes behavioral problems.

What does this study add?

Apart from the duration of media use, screen addiction among children under 12 years was analyzed and found to negatively influence early child development and behavior.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely acknowledge Prof. Sarah E. Domoff, PhD Central Michigan University, USA for her valuable inputs on PMUM scale.

PROFORMA

Basic patient information and Demographics

Name: Ht: Wt:

-

Age

(a) 1.5 yrs to 4yrs (b) >4-12yrs

-

Gender of the child

(a) male (b) female

-

Nutritional status:

(1) normal (2) overweight (3) obesity (4) underweight

-

Socio-economic status:

(1) upper (2) upper middle (3) lower middle (4) upper lower (5) lower

-

Parental employment status

a) father b) mother c) both

-

Number of parents in the household

(a) Two-parent household (a1) Father abroad b) Single-Parent - (i) widowed (ii) divorced (iii) separated

-

Type of family

a) nuclear family b) joint family

-

If Joint family, grandparents media use

(a) yes (b) no

-

Other siblings

(a) yes (b) no If yes no----

-

Which class is your child currently studying?

Academic

-

Since starting school, has your child repeated any grades?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

How is your child's school performance

(a) Excellent (b) Above average (c) Average (d) Below average (e) Very poor

Physical activity

-

During the past week, how long did your child engage in physical activity that made him or her sweat ?

(a) Atleast 30 min/day (b) >30 min (c) none

-

Sleep Difficulties

Child's media use- gadget details

-

Which of the following devices does your child ever use in your home? Tick all that apply

a) TV b) smartphone c) Tablet d) computer/laptope) hand held video games f) kindle reader

-

Which of the following items, if any, does your child have in his/her bedroom Tick all apply

a) TV b) smartphone c) Tablet d) computer/laptop e) hand held video games f) kindle reader g) none

-

What is the most common Screen media used by your child ? Tick all that apply

a) TV b) smartphone c) Tablet d) computer/laptop e) hand held video games f) kindle reader

Average Weekday screen time use by your child

Average Weekend Screentime use by your child

-

How much of this time is spent co-viewing with parent?

a) Always alone b) Always with parent c) partly

-

When your child does homework, how often, if ever, is the TV on in the background

(a) Most of the time (b) Some of the time (c) Only once in a while and (d) Never

-

How often, if ever, does your child like to use more than one type of media at a time, for example, play a handheld game while he/she is watching TV or listening to music while he/she is using the computer? (multitasking)

(a) Most of the time (b) Some of the time (c) Only once in a while (d) Never

-

To the best of your recollection, at what age (in years/months) did your child begin to regularly watch

(i) TVa) <1yr b) 1yr c) 2yrs d) 3yrs e) 4yrs f) never used

(ii) mobilea) <1yr b) 1yr c) 2yrs d) 3yrs e) 4yrs f) never used

-

Does your child own his/her own device?

a) yes b) no

-

Mode of Content delivery

a) Youtube b) Netflix c) Tv channels d) Audibles, Amazon prime

-

Content of programs your child watches

a) Educational b) entertainment c) Both

-

Mention top 3 programs your child watches

Mobile usage

-

Does your child need help to use your mobile

a) yes b) no

-

In one sitting, how many minutes does your child typically play with mobile device?

a) <5 minutes b) 5-10 min c) 11-20 min d) >20 min

-

When does your child typically stop playing on mobile device?

a) When they get bored b) They choose to do something else, like homework or set to play c) I make them stop

d) The battery runs out e) Another reason

-

Reason for letting your child use mobile? Tick all that apply

a) As an entertainment b) During meal time c) To do your routine work e.g., Household work

d) To keep the child calm in public places e) To put the child to sleep f) To keep them occupied during trips/journeys

g) For school homework

YouTube usage

-

Does your child ever use Youtube website/App?

a) Yes b) No c) Dont know

-

Do they use the main Youtube website/App or the Youtube kids app designed for under 5s?

a) Main Youtube website/App b) Youtube kids app designed for under 5s c) Don't know

-

Here is a list of things that your child may have watched on Youtube. Tick all that apply

a) Cartoons, movies, whole programmes, animation b) Funny videos, jokesc) Music videos

d) “How to “ videos/tutorials about hobbies/sports e) Unboxing videos- eg. Where toys are unwrapped or assembled

f) Game tutorials/watch other people/kids play games

Parental media use and concerns

On a typical day, how much time per day do YOU (mother) spend?

-

What type of cell phone, if any, do you have? (Circle one)

a) A 'smartphone' (you can send emails, watch videos, access the Internet on it)

b) A regular cell phone (just for talking and texting)

c) I don't have a cell phone

-

Do you have Apps and/or games on your mobile that your child plays with?

a) Yes b) no

-

How do you choose the Apps that you download for your child?

(a) Educational value (b) Entertainment (c) both

-

How often do you read books (traditional/electronic) to or with your child?

(a) Never (b)) less than once a month (c)) once or twice a month (d)) once a week (e)) several times a week (f)) daily

-

How often is the TV on, while doing household work even if no one is actually watching it?

(a)) Always (b)) Most of the time (c)) Some of the time (d)) Hardly ever (e)) Never

-

Which of the following media devices cause maximum conflict/disagreement with your child when you switch off ?

(a)) TV (b)) Smartphone (c)) Tablet (d)) Computer (e)) Video game

-

Concerns about Media: How concerned are you about your child's media use? Tick all that apply

a)) Violence on TV/Videos b)) Adult Content on TV/Videos c)) Bad Language on TV/Videos d)) Addictive nature of Computer Games

-

Problematic Media Use Measure Short Form (PMUM-SF)-Tick all that apply

Screen addiction

| Age | Education | Income | Profession | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father | ||||

| Mother |

| TODDLER/PRESCHOOL CHILD (2-5yrs) | |

|---|---|

| Bedtime problems | Does your child have any problems going to bed? Falling asleep? |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | Does your child seem overtired or sleepy a lot during the day? Does she still take naps? |

| Awakenings during the nights | Does your child wake up a lot at night? |

| Regularity and duration of sleep | Does your child have a regular bedtime and wake time? What are they? |

| Snoring | Does your child snore a lot or have difficulty breathing at night? |

| (a) 0 hours | (b) <30 min | (c) <1hour | (d) 1-2 hrs | (e) 2-3 hrs | (f) >3 hrs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | ||||||

| Mobile/tab | ||||||

| Laptop/computer | ||||||

| Videogame | ||||||

| Others (pl.specify) |

| (a) 0 hours | (b) <30 min | (c) <1hour | (d) 1-2 h | (e) 2-3 h | (f) >3 h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | ||||||

| Mobile/tab | ||||||

| Laptop/computer | ||||||

| Videogame | ||||||

| Others (pl.specify) |

| (a) 0 hours | (b) <30 min | (c) <1hour | (d) 1-2 hrs | (e) 2-3 hrs | (f) >3 hrs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | ||||||

| Mobile/tab | ||||||

| Laptop/computer | ||||||

| Videogame | ||||||

| Others (pl.specify) |

| 1 Never | 2 Seldom | 3 Sometimes | 4 Often | 5 Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is hard for my child to stop using screen media | |||||

| Screen media is the only thing that seems to motivate my child | |||||

| Screen media is all that my child seems to think about | |||||

| My child’s screen media use interferes with family activities | |||||

| My child’s screen media use causes problems for the family | |||||

| My child becomes frustrated when he/she cannot use screen media | |||||

| The amount of time my child wants to use screen media keeps increasing | |||||

| My child sneaks (stealthily uses) using screen media | |||||

| When my child has had a bad day, screen media seems to be the only thing that helps him/her feel better |

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Paediatric Society Digital Health Task Force. Ottawa, Ontario, Ponti M, Bélanger S, Grimes R, Heard J, Johnson M, et al. Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22:461–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Media and Young Minds. Council on communications and media. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20162591. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamana SK, Ezeugwu V, Chikuma J, Lefebvre DL, Azad MB, Moraes TJ, et al. Screen-time is associated with inattention problems in preschoolers: Results from the CHILD birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advancing Children's Learning in a Digital Age. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://joanganzcooneycenter.org/

- 5.Ofcom.org. Ofcom. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/home .

- 6.Hinkley T, Verbestel V, Ahrens W, Lissner L, Molnár D, Moreno LA, et al. Early childhood electronic media use as a predictor of poorer well-being: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:485–92. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poulain T, Ludwig J, Hiemisch A, Hilbert A, Kiess W. Media use of mothers, media use of children, and parent-child interaction are related to behavioral difficulties and strengths of children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:23. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jago R, Stamatakis E, Gama A, Carvalhal IM, Nogueira H, Rosado V, et al. Parent and child screen-viewing time and home media environment. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downing KL, Hinkley T, Salmon J, Hnatiuk JA, Hesketh KD. Do the correlates of screen time and sedentary time differ in preschool children? [Last accessedon 2020 May 08];BMC Public Health. 2017 17:285. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4195-x. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5372288/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, Budacki JG, Mohanty SH, Leister KP, et al. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1044–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domoff SE, Harrison K, Gearhardt AN, Gentile DA, Lumeng JC, Miller AL. Development and validation of the problematic media use measure: A parent report measure of screen media “Addiction” in children. Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2019;8:2–11. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shahid A, Wilkinson K, Marcu S, Shapiro CM. BEARS sleep screening tool. In: Shahid A, Wilkinson K, Marcu S, Shapiro CM, editors. STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. [Last accessed on2020 Mar 11]. pp. 59–61. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4419-9893-4_7 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squires J, Bricker DD, Twombly E, Potter L. Ages and Stages Questionnaires: A Parent-Completed, Child-Monitoring System. 3rd ed. USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–45. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domingues-Montanari S. Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53:333–8. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khiu AL, Hamzah H. Exploratory analysis of pilot data: Trends of gadget use and psychosocial adjustment in pre-schoolers. Southeast Asia Early Child J. 2018;7:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beyens I, Nathanson AI. Electronic media use and sleep among preschoolers: Evidence for time-shifted and less consolidated sleep. Health Commun. 2019;34:537–44. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1422102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrison MM, Liekweg K, Christakis DA. Media use and child sleep: The impact of content, timing, and environment. Pediatrics. 2011;128:29–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asplund KM, Kair LR, Arain YH, Cervantes M, Oreskovic NM, Zuckerman KE. Early childhood screen time and parental attitudes toward child television viewing in a low-income Latino population attending the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children. Child Obes. 2015;11:590–9. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samudra PG, Flynn RM, Wong KM. Coviewing educational media: Does coviewing help low-income preschoolers learn auditory and audiovisual vocabulary associations? AERA Open. 2019;5:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carson V, Spence JC, Cutumisu N, Cargill L. Association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and screen time among pre-school children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:367. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domoff SE, Borgen AL, Foley RP, Maffett A. Excessive use of mobile devices and children's physical health. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2019;1:169–75. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez OL. Problem mobile phone use in spanish and british adolescents: First steps towards a cross-cultural research in Europe. Psychol Soc Netw Identity Relatsh Online Communities. 2016;2:186–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen CF, Tang TC, Yen JY, Lin HC, Huang CF, Liu SC, et al. Symptoms of problematic cellular phone use, functional impairment and its association with depression among adolescents in Southern Taiwan. J Adolesc. 2009;32:863–73. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin LY, Cherng RJ, Chen YJ, Chen YJ, Yang HM. Effects of television exposure on developmental skills among young children. Infant Behav Dev. 2015;38:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radesky JS, Peacock-Chambers E, Zuckerman B, Silverstein M. Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:397–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise J. Screen time: Two hour daily limit would improve children's cognition, study finds. [Last accessed on 2020 May 11];BMJ. 2018 362:k4070. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/362/bmj.k4070 . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller CJ, Marks DJ, Miller SR, Berwid OG, Kera EC, Santra A, et al. Brief report: Television viewing and risk for attention problems in preschool children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:448–52. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozmert E, Toyran M, Yurdakök K. Behavioral correlates of television viewing in primary school children evaluated by the child behavior checklist. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:910–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.9.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulain T, Vogel M, Neef M, Abicht F, Hilbert A, Genuneit J, et al. Reciprocal Associations between Electronic Media Use and Behavioral Difficulties in Preschoolers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:814. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]