Abstract

Background

Imaging Somatostatin Subtype Receptor 2 (SST2) expressing macrophages by [DOTA,Tyr3]-octreotate (DOTATATE) has proven successful for plaque detection. DOTA-JR11 is a SST2 targeting ligand with a five times higher tumor uptake than DOTATATE, and holds promise to improve plaque imaging. The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential of DOTA-JR11 for plaque detection.

Methods and Results

Atherosclerotic ApoE−/− mice (n = 22) fed an atherogenic diet were imaged by SPECT/CT two hours post injection of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 (~ 200 pmol, ~ 50 MBq). In vivo plaque uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 was visible in all mice, with a target-to-background-ratio (TBR) of 2.23 ± 0.35. Post-mortem scans after thymectomy and ex vivo scans of the arteries after excision of the arteries confirmed plaque uptake of the radioligand with TBRs of 2.46 ± 0.52 and 3.43 ± 1.45 respectively. Oil red O lipid-staining and ex vivo autoradiography of excised arteries showed [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake at plaque locations. Histological processing showed CD68 (macrophages) and SST2 expressing cells in plaques. SPECT/CT, in vitro autoradiography and immunohistochemistry performed on slices of a human carotid endarterectomy sample showed [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake at plaque locations containing CD68 and SST2 expressing cells.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate DOTA-JR11 as a promising ligand for visualization of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12350-020-02046-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: SPECT, atherosclerosis, inflammation, molecular imaging

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.1 Most cardiovascular events are caused by atherosclerosis, in which plaques form over time due to continuous inflammation and lipid deposition in the arterial wall. Current imaging techniques focus on plaque morphology or measures such as calcium score, which are used for cardiovascular risk assessment to improve clinical risk scores.2 Inflammation is a crucial factor in atherosclerotic plaque and plays a crucial role in plaque initiation, progression, and destabilization.3,4 Imaging plaque inflammation may complement traditional imaging methods, providing a better risk stratification of patients at risk of future cardiovascular events.

2-Deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose ([18F]FDG) has proven a reliable non-invasive imaging method not only to detect, but even to quantify the degree of inflammation in plaques.5–718F-FDG, therefore, provides a valuable tool to assess and monitor disease burden.8 However, background uptake in normal tissue and high uptake of 18F-FDG in the myocardium severely hinders detection of coronary plaques,9,10 and warrants the search for novel radioligands.

Somatostatin Subtype Receptor 2 (SST2) is highly expressed on activated macrophages.11,12 As macrophages are the main inflammatory cell type in atherosclerotic plaque, SST2 has been proposed as a relevant imaging target for inflammation-based plaque detection. A number of studies have reported on the use of SST2 for inflammation-based imaging of atherosclerosis.13–19 Moreover, Tarkin et al. recently prospectively validated [68Ga]Ga-[DOTA, Tyr3]-octreotate (DOTATATE) as a marker for plaque inflammation 20 in a clinical study. They demonstrated the feasibility to detect both carotid and coronary plaques with [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. Moreover, [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE could better discriminate between high-risk and low-risk lesions compared to [18F]FDG.

Various radioligands, based on SST2 agonists, for SST2-targeted imaging and therapy have been developed and used over the past 20 years for detection and treatment of SST2-expressing tumors.21 More recently, a new generation of radioligands based on SST2 antagonists has been developed and described, showing more favorable pharmacokinetics and higher tumor uptake than agonists like DOTATATE. Of these, the compound JR11 (Cpac[d-Cys-Aph(Hor)-d-Aph(Cbm)-Lys-Thr-Cys]-d-Tyr-NH2) performed best in preclinical and clinical studies as an imaging as well as a therapeutic agent.21–24 Based on the reported favorable biodistribution and targeting efficiency of DOTA-JR11, we studied the potential of DOTA-JR11 in inflammation imaging for atherosclerotic plaque detection as it could yield higher TBRs than agonistic radioligands. We therefore used [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography/Computed Tomography (SPECT/CT) to image plaques in vivo in an atherosclerotic mouse model, and assessed target binding in human plaque material.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Setup

Atherosclerotic female ApoE−/− mice on a C67BL/6J background (n = 22) were purchased from Charles Rivers (Calco, Italy) at 6 weeks of age, and were fed a high fat diet (0.3% cholesterol, Altromin Spezialfutter GmbH & Co. KG, Lage, Germany) ad libitum from an age of 8 weeks up to 20 weeks. All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal studies committee and were in accordance with Dutch animal ethical legislation and the European Union Directive.

Radiolabeling

[111In]In-DOTA-JR11 (MW = 1690 g/mol) (kindly provided by Dr. Helmut Maecke) was radiolabeled with [111In]InCl3 (Covidien, Petten, The Netherlands) with a specific activity of 200 MBq/nmol as described previously.25 Radiochemical purity (> 95%) and incorporation yield (> 99%) were evaluated with high-pressure liquid chromatography and instant thin-layer chromatography on silica gel. Quenchers (3.5 mM gentisic acid, 3.5 mM ascorbic acid, 7% ethanol) were added to prevent radiolysis as described previously.26

In Vivo Imaging and Validation

Mice (n = 22) were injected with 50 MBq/200 pmol [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with 0.1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), with a total injection volume of 150 µL. Four mice were co-injected with a 100 × excess of unlabeled DOTA-JR11 to test the specificity of the radioligand. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isofluorane 2 hours post injection, after which they were injected with 50 µL CT-contrast agent (Exitron Nano 12000, Milteny Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). Immediately after contrast agent injection, mice were transferred to a VECTor5/CT scanner (MILabs B.V. Utrecht, The Netherlands) on which a CT scan was made followed by a SPECT scan. The time between radioligand injection and imaging was based on pilot experiments (data not shown). The CT scan was made with the following settings: full scan angle; accurate scan mode; 50 kV tube voltage; 0.24 mA tube current; 3.5 minute scan time. CT scans were reconstructed at a resolution of 80 µm. SPECT was performed with the M3.0 pinhole collimator (resolution < 1.3 mm, sensitivity > 30,000 cps/MBq). Data were acquired in list-mode using the following acquisition parameters: 1 h scan; 15 positions; spiral scan mode; fine step mode. Scans were reconstructed with energy windows incorporating a width of 20% of the In-111 photo peaks of 171 and 245 keV with background windows of 2.5% on either side of the photo peak windows, and scatter correction was applied according to Ref. 27 Reconstructions were performed with a SROSEM (Similarity Regulated Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization28) algorithm with 9 iterations, 128 subsets, with a voxel size of 0.4 mm and a post reconstruction 3-dimensional Gaussian filter was applied (1 mm full width at half maximum).

After in vivo imaging, mice were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane, after which the vasculature was flushed with PBS via the left ventricle, and thymectomy was performed. In this state, the thorax of the euthanized mice was scanned ‘in situ’ to circumvent signal interference from thymic uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 with signal from plaque uptake. CT and SPECT settings for in situ imaging were the same as for in vivo imaging, except for a shorter SPECT scan duration of 30 minutes.

The arteries were removed after in situ imaging, and cleaned of remaining connective tissue. They were then stained for lipids (Oil Red O (ORO) according to standard protocol) to confirm plaque presence, and scanned ex vivo with SPECT/CT. The scan settings for ex vivo imaging were the same as in situ settings except for four SPECT positions due to a smaller field of view. Subsequently, the arteries were cut open and used for ex vivo autoradiography (n = 4) or embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek Europe B.V., Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) and stored at – 80 °C for histological analysis (n = 14). After ~ 2 weeks, arteries used for ex vivo autoradiography were placed on a phosphor screen overnight and read using a phosphor imager (Cyclone, Perkin Elmer).

Ex vivo Carotid Endarterectomy Study

To investigate binding of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 to and its potential for imaging of human plaque tissue, we performed an ex vivo study with human carotid endarterectomy (CEA) tissue slices. For this purpose we sliced a CEA sample (acquired with informed consent and approved by the medical ethics committee of the Erasmus MC, MEC 2008-147) into 2 mm slices. Even-numbered slices were embedded in O.C.T. compound and stored at − 80° C for later in vitro binding assays and histological evaluation. Odd-numbered slices were incubated with 200 MBq/1 nmol [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 in 20 mL PBS with 0.1% BSA for one hour. After incubation, the slices were washed in PBS with 0.1% BSA until no residual radioactivity remained in the washing medium as measured by a dose calibrator (Dose calibrator VDC-405, Comecer Netherlands, Joure, The Netherlands). The slices were subsequently placed on a holder, and imaged with the VECTor5/CT. CT and SPECT settings were the same as for the in vivo mouse scan, except a mouse 1.6 pinhole collimator (resolution < 1.6 mm, sensitivity > 1500 cps/MBq) was used with 38 scan positions, and the scans were reconstructed with a Gaussian filter of 0.5 mm full width at half maximum.

Immunohistochemistry and In Vitro Binding Assays

Embedded mouse arteries and CEA slices were sectioned into 5 µm sections, which were immunohistochemically stained for CD68 (Mouse: 1:100, Biorad, MCA1848; human: 1:100, Abcam, ab955) and SST2 (1:100, Abcam, clone UMB-1) to assess target presence and presence of macrophages. In short, sections were fixed in cold acetone for 5 minutes, endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.3% H2O2, and non-specific binding was blocked with 1% BSA for mouse CD68 staining and 2% normal goat serum for SST2 and human CD68 staining. The primary antibody was omitted from the protocol in negative controls.

10 µm sections, adjacent to the 5 µm sections used for immunohistochemistry, were cut from the embedded CEA slices to assess radioligand uptake via an in vitro competition binding assay (autoradiography). Sections were incubated for 1 h with 10−9 M [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 with or without an excess of 10−6 M unlabeled DOTA-JR11 to asses specific binding. Slides were exposed to phosphor screens overnight and read with a phosphor imager (Cyclone, Perkin Elmer). Haematoxylin–eosin staining according to standard protocol was performed on the sections afterwards.

Quantification and Statistics

SPECT/CT data were analyzed with Vivoquant (Invicro) by quantification of the activity within manually drawn regions of interests (ROIs) based on contrast-enhanced CT images. In vivo ROIs were drawn for the aortic arch and the brachiocephalic artery, whereas the vena cava inferior and jugular vein were used as background regions. In situ ROIs were the aortic arch and brachiocephalic artery, and the heart ventricles were taken as background tissue. ROIs on ex vivo images were also the aortic arch and brachiocephalic artery for plaque areas, and the relatively healthy descending thoracic aorta as background. Target-to-background-ratios (TBRs) were calculated and expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

In vitro autoradiography analysis was performed by drawing ROIs around tissue sections in Optiquant (Perkin Elmer), quantifying the signal as Digital Light Units (DLU)/mm2 and comparing non-blocked to blocked tissue sections.

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test data for normality. The student’s t test was used to compare means of normally distributed data, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-parametric data.

Results

Mouse Plaque Imaging

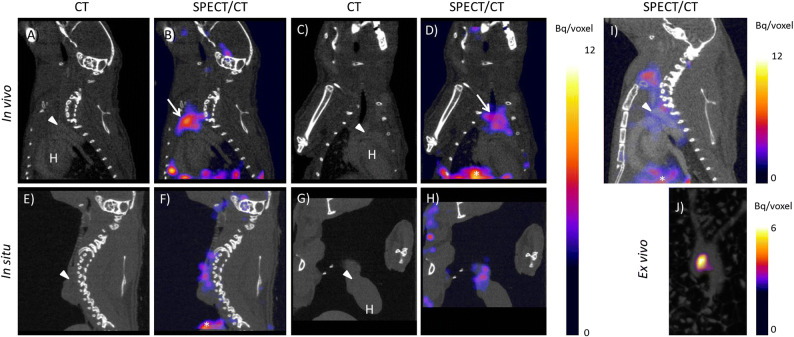

In vivo SPECT/CT imaging 2 h after intravenous injection of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 showed focal uptake at locations of plaque formation in the vasculature of all animals (Fig. 1A-D), with an average TBR of 2.23 ± 0.35. Thymic uptake (average TBR of 2.28 ± 0.51) of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 masked plaque signal and therefore complicated visualization and quantification. Therefore, ‘in situ’ scans were made in post-mortem thymectomized animals. In situ SPECT/CT imaging confirmed plaque uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 as seen in in vivo images (Fig. 1E-H), with a TBR of 2.46 ± 0.52. Blocking studies with an 100x excess of DOTA-JR11 significantly reduced the arterial signal (TBR in vivo blocked: 1.47 ± 0.36; TBR in situ blocked: 1.36 ± 0.15, P = 0.05, see Fig. 1I and Online Resource 1) Likewise, blocking significantly reduced uptake in the thymus (TBR 1.32 ± 0.43, P = 0.05).

Fig. 1.

[111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in mouse atherosclerotic plaque two hours post injection of 200 pmol [111In]In-DOTA-JR11. A Sagittal CT, B saggital SPECT/CT, C coronal CT, and D coronal SPECT/CT image of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in vivo in an atherosclerotic mouse. E Sagittal CT, F saggital SPECT/CT, G coronal CT, and H coronal SPECT/CT image of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in situ in the mouse displayed in (A-C) scanned post-mortem after thymectomy and flushing of the vasculature with PBS. I Sagittal SPECT/CT image of a mouse two hours post injection of 50 MBq/200 pmol [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 plus a 100 × excess of unlabeled DOTA-JR11. Plaque uptake was strongly reduced by blocking. J Maximum intensity projection image of the excised arteries of the mouse shown in (A-H). Focal uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 is visible at the plaque location. Arrowheads indicates the location of the aortic arch containing plaque, arrows indicates thymic uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11, *Indicates uptake in the liver, H indicates the heart

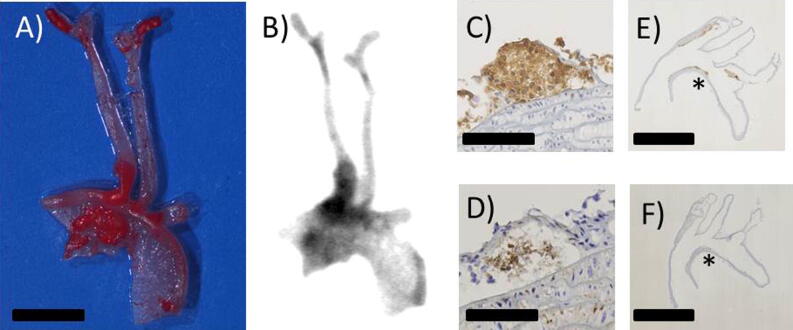

Presence of plaque in excised arteries was confirmed by ORO staining of excised arteries. Ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging of the mouse arteries showed uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 at plaque locations in the aortic arch and brachiocephalic artery with a TBR of 3.43 ± 1.45 (Fig. 1J). Ex vivo autoradiography and ORO staining of excised, cut open arteries confirmed uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 in plaque (Fig. 2A, B). Immunohistochemistry of the arteries confirmed presence of SST2 and CD68 expressing cells in plaque (Fig. 2C-F).

Fig. 2.

A Excised, cut open and Oil red O stained arteries of a mouse injected with 200 pmol [111In]In-DOTA-JR11. Scale bar indicates 2 mm. B Matching high resolution ex vivo autoradiogram to the arteries shown in (A), showing [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake at plaque locations. C, D show immunohistochemistry for CD68 (macrophages) and Somatostatin Subtype Receptor 2 (SST2) expressing cells in mouse plaque, respectively. Scale bar indicates 100 µm. E, F show the overview of the histological sections shown in (C) and (D); the asterisk marks the location of the zoomed area in (C) and (D). Scale bar indicates 2.5 mm

Human Plaque Imaging

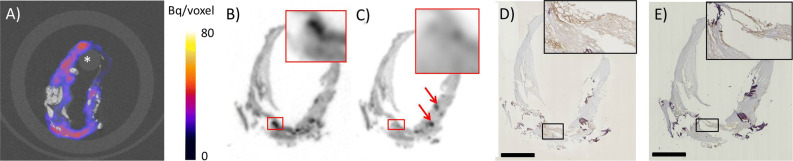

Two millimeter thick slices of a human carotid endarterectomy sample incubated with [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 showed focal hotspots of radioligand uptake detectable by SPECT, reflecting the presence of SST2 as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3). Noticeably, no radioligand uptake or SST2 expression was visible in areas of macrocalcifications visible in CT. In vitro autoradiography performed on 10 µm sections of adjacent 2 mm slices showed specific binding of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 when compared to adjacent sections incubated with a 1000 × excess of unlabeled DOTA-JR11 (non-blocked = 35 × 106 ± 90 × 105, blocked = 25 × 106 ± 63 × 105 DLU/mm2, P = 0.005, see Online Resource 2 and Fig. 3). Moreover, radioligand uptake visualized on in vitro autoradiography co-localized with CD68 and SST2 expression on adjacent sections, and signal as seen on the SPECT/CT images of the adjacent 2 mm slices (Fig. 3B-E).

Fig. 3.

[111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in human carotid endarterectomy (CEA) tissue after incubation with [111In]In-DOTA-JR11. A Transverse SPECT/CT image of a 2 mm slice of a CEA sample. Calcifications are visible in CT in white, the asterisk indicates the holder used to keep the 2 mm slice in place. B, C In vitro autoradiography of adjacent 10 µm sections made of an adjacent 2 mm slice of the same CEA sample seen in (A). The section in B was incubated with 10−9 M [111In]In-DOTA-JR11, the section in C was incubated with 10−9 M [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 plus a blocking dose of 10−6 M unlabeled DOTA-JR11. The inset shows the boxed region at higher magnification, the red arrows indicate sectioning artifacts (tissue folds). D SST2 and E CD68 immunohistochemistry on 5 µm sections adjacent to B and C, with matching insets. Scale bar indicates 2 mm

Discussion

We have demonstrated the feasibility of imaging atherosclerotic plaques by targeting SST2 with DOTA-JR11, by visualizing plaque with In-111 labeled DOTA-JR11 in a mouse model of atherosclerosis and in human plaque tissue. We showed that radioligand uptake is located in plaque regions in the mouse vasculature as evidenced by in vivo and in situ SPECT/CT imaging, autoradiography, and ORO staining. [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in human plaque tissue co-localizes with SST2 and CD68 expressing cells, whereas blocking studies show target-specific uptake in vivo and in situ in mouse plaque, and in vitro in human tissue.

High thymic uptake of [111In]In-DOTA-JR11, visible in the in vivo SPECT images and in line with reported SST2 expression in mice in this tissue,29 is problematic when visualizing plaque in the used atherosclerotic model. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that the in vivo signal visible next to the thymus did originate from plaque, by comparing the intensity and the localization of plaque signal in the in vivo, in situ, and ex vivo SPECT scans, as well as the ex vivo autoradiography. Thymic uptake is not expected to interfere with human plaque imaging as thymic activity wanes during adolescence, and little SST2-ligand binding has been found in dedicated studies.30 Ex vivo imaging of a human CEA sample showed that SPECT imaging using [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 is feasible in human plaque tissue and that radioligand uptake co-localizes to regions of inflammation as evidenced by CD68 and SST2 immunohistochemistry. These results indicate that DOTA-JR11 has potential for imaging of inflammation in human plaques.

Oncological studies reported a five times higher uptake of DOTA-JR11 over DOTATATE in SST2 positive tumors.21–23 It is hypothesized that antagonistic ligands such as DOTA-JR11 have more binding sites on the receptor than agonistic ligands such as DOTATATE.31 Although the exact mechanism for this difference in uptake remains to be elucidated, the growing amount of studies using SST2-mediated imaging in atherosclerosis 13–19 indicate DOTA-JR11 as an interesting candidate for further studies.

DOTATATE and DOTA-JR11 have not been compared for the detection of atherosclerotic plaque. Two preclinical studies have tested [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE for plaque imaging in mouse models, however. Although it is difficult to compare studies using different animal models and different imaging systems, the results found in 14,15 indicate that [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE has a lower TBR compared to [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 in our study. Rinne et al. found an aorta to blood ratio of 0.67 ± 0.04 using [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in vivo in IFG-II/LDLR−/−ApoB100/100 mice,15 indicating low radioligand uptake in plaque. However, they also reported a high plaque to wall ratio of 2.1 ± 0.5 for [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in autoradiographic studies. Li et al. found a similar plaque to non plaque ratio of ~ 1.8 after autoradiographic analysis of ApoE−/− arteries incubated with [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE.14 We found an in vivo TBR of 2.23 ± 0.35 and an in situ TBR of 2.46 ± 0.52, and in the autoradiogram of the mouse arteries we found a TBR of 3.43 ± 1.45. Taken together, these studies warrant further investigations into the added value of DOTA-JR11 over DOTATATE in atherosclerotic patients.

If a five times higher uptake of DOTA-JR11, as was found in oncological studies, would be found in atherosclerosis as well, DOTA-JR11 could offer possibilities for visualization of less inflamed plaques or plaques with lower SST2 expression. Moreover, the DOTA chelator of JR11 allows labeling with different radionuclides including Ga-68, making DOTA-JR11 attractive for PET imaging. Although different radiometals result in differences in binding affinity of DOTA-JR11,32 the attractive pharmacokinetics of DOTA-JR11 are conserved when labeled with Ga-68.24

Because inflammation in different plaque regions can have a substantial effect on the rupture risk of atherosclerotic plaques, future studies should investigate whether DOTA-JR11 uptake can be correlated to different plaque phenotypes. A better interpretation of radioligand uptake related to plaque phenotype could be a major step in patient risk stratification.

Conclusion

Our results indicate DOTA-JR11 as a promising ligand for atherosclerosis imaging based on our promising in vivo results and ex vivo validation studies. DOTA-JR11 could be a valuable improvement in imaging of inflammation in atherosclerotic disease.

New Knowledge Gained

The SST2 targeting radioligand [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 can be used to detect plaques in a mouse model of atherosclerosis by visualizing plaque inflammation. [111In]In-DOTA-JR11 uptake in human plaque tissue indicates the translational potential of this radioligand for human imaging. Recent success of SST2 imaging in atherosclerosis with DOTATATE, and a five times higher TBR of DOTA-JR11 than DOTATATE in oncological studies, make DOTA-JR11 an interesting ligand for further studies in atherosclerosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic supplementary material 1 (PDF 711 kb)

Electronic supplementary material 2 (M4A 5634 kb)

Electronic supplementary material 3 (PPTX 2418 kb)

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

Eric J. Meester, Boudewijn J. Krenning, Erik de Blois, Marion de Jong, Antonius F. W. van der Steen, Monique R. Bernsen and Kim van der Heiden report no relevant disclosures.

Abbreviations

- SST2

Somatostatin subtype receptor 2

- SPECT

Single photon emission tomography

- CT

Computed tomography

- ORO

Oil red O

- CEA

Carotid endarterectomy

- TBR

Target-to-background-ratio

Footnotes

The authors of this article have provided a PowerPoint file, available for download at SpringerLink, which summarizes the contents of the paper and is free for re-use at meetings and presentations. Search for the article DOI on SpringerLink.com.

The authors have also provided an audio summary of the article, which is available to download as ESM, or to listen to via the JNC/ASNC Podcast.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Erasmus MC. K. van der Heiden is funded by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (Proj. No. NHS2014T096).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Monique R. Bernsen and Kim van der Heiden have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators I Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specifi c mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;380(9859):1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quillard T, Libby P. Molecular imaging of atherosclerosis for improving diagnostic and therapeutic development. Circ Res. 2012;111(2):231–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: A dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(10):709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd JHF, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105(23):2708–2711. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020548.60110.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawakol A, Migrino R, Hoffmann U, et al. Noninvasive in vivo measurement of vascular inflammation with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2005;12(3):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueroa AL, Subramanian SS, Cury RC, et al. Distribution of inflammation within carotid atherosclerotic plaques with high-risk morphological features a comparison between positron emission tomography activity, plaque morphology, and histopathology. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:69–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.959478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudd JHF, Narula J, Strauss HW, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation by fluorodeoxyglucose with positron emission tomography. Ready for prime time? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(23):2527–2535. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buettner C, Rudd JHF, Fayad ZA. Determinants of FDG uptake in atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(12):1302–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Rudd JHF. PET imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(8):443–457. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott DE, Li J, Blum AM, Metwali A, Patel YC, Weinstock JV. SSTR2A is the dominant somatostatin receptor subtype expressed by inflammatory cells, is widely expressed and directly regulates T cell IFN-gamma release. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(8):2454–2463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2454::AID-IMMU2454>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalm VASH, van Hagen PM, van Koetsveld PM, et al. Expression of somatostatin, cortistatin, and somatostatin receptors in human monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285(2):E344–E353. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00048.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rominger A, Saam T, Vogl E, et al. In vivo imaging of macrophage activity in the coronary arteries using 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT: Correlation with coronary calcium burden and risk factors. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(2):193–197. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Bauer W, Kreissl MC, et al. Specific somatostatin receptor II expression in arterial plaque: 68 Ga-DOTATATE autoradiographic, immunohistochemical and flow cytometric studies in apoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinne P, Hellberg S, Kiugel M, et al. Comparison of somatostatin receptor 2-targeting PET tracers in the detection of mouse atherosclerotic plaques. Mol Imaging Biol. 2015;18(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11307-015-0873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mojtahedi A, Alavi A, Thamake S, et al. Assessment of vulnerable atherosclerotic and fibrotic plaques in coronary arteries using 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;5(1):65–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malmberg C, Ripa RS, Johnbeck CB, et al. 64Cu-DOTATATE for non-invasive assessment of atherosclerosis in large arteries and its correlation with risk factors: Head-to-head comparison with 68 Ga-DOTATOC in 60 patients. J Nucl Med. 2015;2015:1–33. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.161216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen SF, Sandholt BV, Keller SH, et al. 64Cu-DOTATATE PET/MRI for detection of activated macrophages in carotid atherosclerotic plaques significance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(7):1696–1703. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan MYS, Endozo R, Michopoulou S, et al. PET/CT imaging of unstable carotid plaque with 68Ga-labeled somatostatin receptor ligand. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(5):774–780. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.181438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Evans NR, et al. Detection of atherosclerotic inflammation by 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET compared to [18F]FDG PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(14):1774–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fani M, Nicolas GP, Wild D. Somatostatin receptor antagonists for imaging and therapy. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(Supplement 2):61S–66S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.186783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wild D, Fani M, Fischer R, et al. Comparison of somatostatin receptor agonist and antagonist for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy: a pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(8):1248–1253. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.138834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalm SU, Nonnekens J, Doeswijk GN, et al. Comparison of the therapeutic response to treatment with a 177Lu-labeled somatostatin receptor agonist and antagonist in preclinical models. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(2):260–266. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.167007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs S, Pandit-Taskar N, Reidy D, et al. Biodistribution and radiation dose estimates for 68 Ga-DOTA-JR11 in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(3):677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Blois E, Schroeder RJ, de Ridder CMA, van Weerden W, Breeman WAP, de Jong M. Improving radiopeptide pharmacokinetics by adjusting experimental conditions for bombesin receptor-mediated imaging of prostate cancer. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;57:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Blois E, Chan HS, de Zanger R, Konijnenberg M, Breeman WAP. Application of single-vial ready-for-use formulation of 111In- or 177Lu-labelled somatostatin analogs. Appl Radiat Isot. 2014;85:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa K, Harata Y, Ichihara T, Kubo A, Hashimoto S. A practical method for position-dependent compton-scatter correction in single photon emission CT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10(3):408–412. doi: 10.1109/42.97591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaissier PEB, Beekman FJ, Goorden MC. Similarity-regulation of OS-EM for accelerated SPECT reconstruction. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61(11):4300–4315. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/11/4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofland LJ, Lamberts SWJ, Van Hagen PM, et al. Crucial role for somatostatin receptor subtype 2 in determining the uptake of [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]octreotide in somatostatin receptor-positive organs. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(8):1315–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferone D, Pivonello R, Kwekkeboom DJ, et al. Immunohistochemical localization and quantitative expression of somatostatin receptors in normal human spleen and thymus: Implications for the in vivo visualization during somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35(5):528–534. doi: 10.3275/7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginj M, Zhang H, Waser B, et al. Radiolabeled somatostatin receptor antagonists are preferable to agonists for in vivo peptide receptor targeting of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(44):16436–16441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607761103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fani M, Braun F, Waser B, et al. Unexpected sensitivity of sst 2 antagonists to N-terminal radiometal modifications. J Nucl Med. 2012;202:1481–1490. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.102764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Electronic supplementary material 1 (PDF 711 kb)

Electronic supplementary material 2 (M4A 5634 kb)

Electronic supplementary material 3 (PPTX 2418 kb)