Abstract

Aim

To assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on admissions of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) in countries participating in the Stent-Save a Life (SSL) global initiative.

Methods and Results

We conducted a multicenter observational survey to collect data on patient admissions for ACS, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and PPCI in participating SSL member countries through a period during the COVID-19 outbreak (March and April 2020) compared with the equivalent period in 2019. Of the 32 member countries of the SSL global initiative, 17 agreed to participate in the survey (three in Africa, five in Asia, six in Europe and three in Latin America). Overall reductions of 27.5% and 20.0% were observed in admissions for ACS and STEMI, respectively. The decrease in PPCI was 26.7%. This trend was observed in all except two countries. In these two, the pandemic peaked later than in the other countries.

Conclusions

This survey shows that the COVID-19 outbreak was associated with a significant reduction in hospital admissions for ACS and STEMI as well as a reduction in PPCI, which can be explained by both patient- and system-related factors.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Stent Save a Life, COVID-19

Resumo

Objetivos

Avaliar o impacto da pandemia COVID-19 nas admissões de doentes com síndromes coronárias agudas (SCA) e angioplastia coronária primária (PPCI) em países que participam da iniciativa global Stent-Save a Life (SSL).

Métodos e resultados

Realizámos estudo observacional multicêntrico para coletar dados sobre admissões de doentes por ACS, STEMI e PPCI nos países participantes no SSL durante um período do surto COVID-19 (março e abril de 2020) em comparação com o período homólogo de 2019. Dos 32 países membros da iniciativa global SSL, 17 aceitaram participar no estudo (3 de África, 5 da Ásia, 6 da Europa e 3 da América Latina (LATAM)). Observámos uma redução global de 27,5% e 20,0% nos internamentos com SCA e STEMI, respetivamente. A diminuição do PPCI foi de 26,7%. Essa tendência foi observada em todos os países, exceto dois. Nestes dois países, a pandemia atingiu o pico mais tarde do que nos restantes.

Conclusões

Este estudo mostra que o surto de COVID-19 foi associado a uma redução significativa de admissões hospitalares por SCA e STEMI, bem como uma redução de PPCI, o que pode ser explicado por fatores relacionados com o doente e com o sistema.

Palavras-chave: Enfarte do miocárdio, Stent Save a Life, COVID-19

Introduction

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has placed an enormous burden on health services and brought significant changes in the social life of populations worldwide.1, 2 Reports have suggested a decrease in the number of patients presenting to hospitals with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Stent-Save a Life (SSL) aims to improve the delivery of care and patient access to the life-saving indication of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI), thereby reducing mortality and morbidity in patients suffering from acute coronary syndromes (ACS).13, 14 SSL is a global project, with member countries from all continents collaborating to develop solutions to logistical and organizational barriers that block patient access to the best current treatment for STEMI, which is PPCI. The current pandemic has added new challenges to already identified difficulties.

The aim of the present analysis was to investigate the rate of PPCI during the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 in countries participating in the SSL global initiative in comparison with the same period in 2019.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive observational study was conducted through a survey of countries participating in the SSL initiative. Of the 32 SSL member countries, 17 agreed to contribute to the survey (three in Africa, five in Asia, six in Europe and three in Latin America).

The requested data correspond to the period of March and April 2020 compared to March and April 2019. We collected data on the number of patients admitted with ACS and STEMI and the numbers of PPCI procedures performed.

Data sources varied by country: some were national registries, representing the total population, while others were based on local databases collected by the regional SSL group.

Results

Information was received from the 17 participating countries.

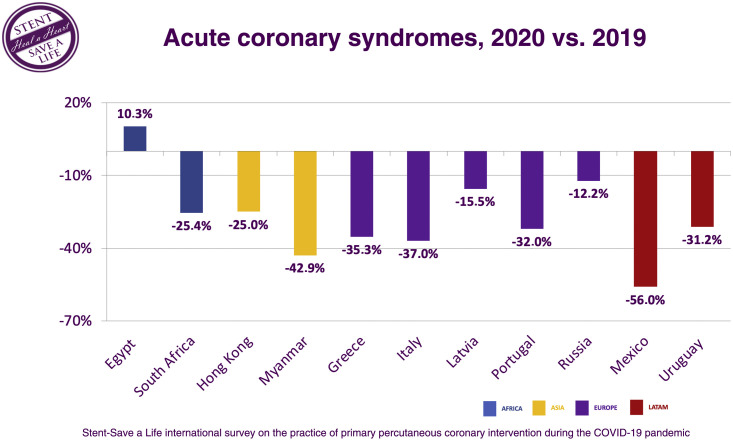

The mean reduction in numbers of ACS patients admitted to the hospital was 27.5%. All countries showed a reduction except Egypt, where there was an increase of 10.3%. In Myanmar and Mexico, a fall of >40% was observed (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Comparison of patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes in March and April 2020 versus March and April 2019 in selected countries. LATAM: Latin America.

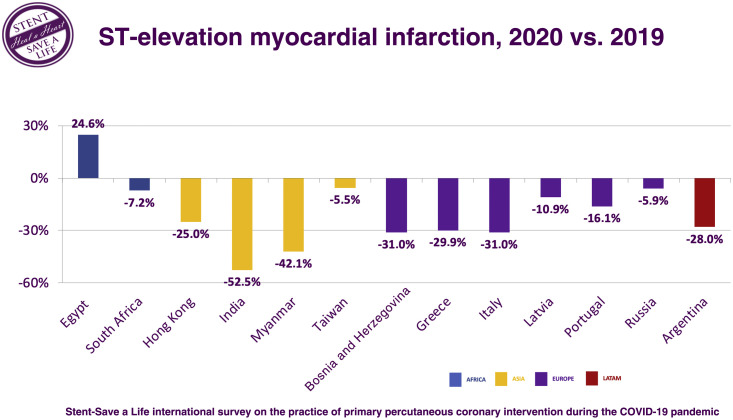

The mean reduction in numbers of STEMI patients admitted to the hospital was 20.5%; as for ACS in general, reductions were seen in all countries with the exception of Egypt (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Comparison of patients admitted with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in March and April 2020 versus March and April 2019 in selected countries. LATAM: Latin America.

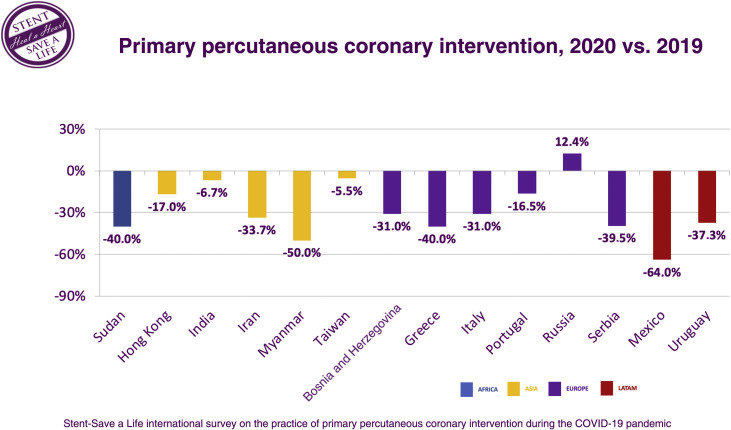

The mean reduction in PPCI numbers was 26.7%. All countries except Russia showed a reduction in PPCI during the pandemic in the 2020 period compared to the same period in 2019. In Sudan, Myanmar, and Mexico, the fall was ≥40% (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Comparison of patients admitted for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in March and April 2020 versus March and April 2019 in selected countries. LATAM: Latin America.

Discussion

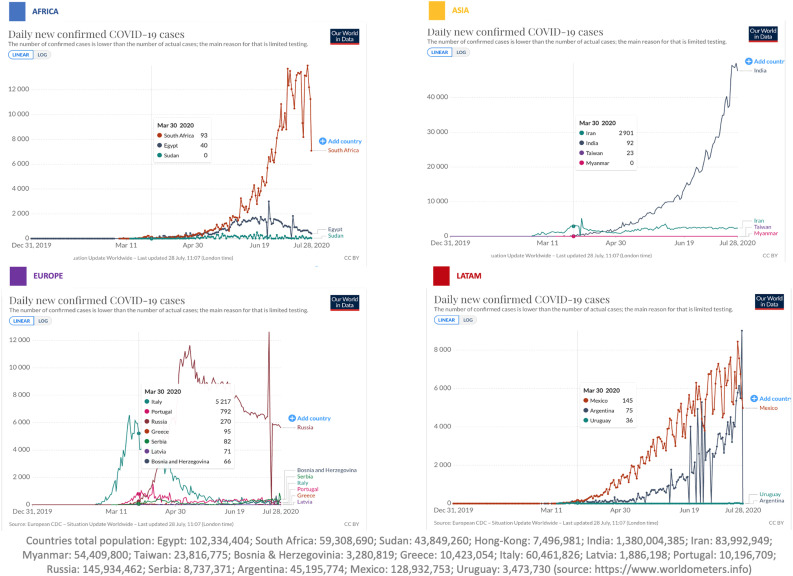

The results show a significant decrease in hospital admissions of patients with ACS and in the numbers of PPCI procedures performed in almost all countries in this survey during the pandemic compared to the same period in 2019. The mean reduction in ACS patients admitted to the hospital was 27.5%, with a reduction of more than 40% in three countries: Mexico, Myanmar and Sudan. The increased activity observed in Egypt and Russia, according to local SSL officials, is related to the considerable efforts made in 2019 to expand the capacity for invasive treatment of ACS in these countries, which resulted in the opening of more catheterization laboratories and development of STEMI networks. Another explanation is that the period under analysis (March and April 2020) was the most critical time of the pandemic in Western Europe, whereas the peak of incidence in Egypt and Russia occurred later, as shown in Figure 4 .15 A report by Mohamed Sobhy (personal communication) of SSL Egypt revealed that, when the number of patients enrolled in May and June 2019 was compared to the number enrolled in May and June 2020, the number of ACS patients was also lower. The total number of ACS patients enrolled in the Egyptian registry in May and June 2020 decreased by 18.3% and the number of STEMI cases fell by 16.0%.16 Given that the peak incidence outside Western Europe occurred later, these data may lead us to speculate that, in countries where the peak was delayed, the impact will have been even more marked than reported for the months of March and April.15

Figure 4.

Evolution of the pandemic by region (Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America) with prevalence centered on March 30, 2020 according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. LATAM: Latin America.

This reduction in the number of patients admitted to hospitals with STEMI was quickly noticed by interventional cardiology departments, with several centers and societies reporting the phenomenon. In a study by Rodríguez-Leor in Spain comparing equivalent periods of 2019 and 2020,3 there was a significant decrease in diagnostic procedures (-56%), percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) (-48%), structural interventions (-81%) and PCI in STEMI (-40%). Similarly, a lower rate of hospital admissions for ACS was observed during the COVID-19 outbreak in northern Italy.4 Also in Italy, a nationwide survey collected data on admissions for STEMI through a one-week period during the COVID-19 outbreak and observed a 48.4% reduction in admissions for myocardial infarction (MI) compared with the equivalent week in 2019.10

The European Society of Cardiology also launched a worldwide internet-based questionnaire that was designed to capture the perception of cardiologists and nurses with regards to changes in frequency and timing of STEMI admissions.16 Overall, there was a perception that the number of admissions of patients with STEMI was substantially reduced, by more than 40%.

In other continents, activity and hospitalizations for ACS were also reduced. A study of 79 centers in all 20 Latin American countries showed a decrease in the number of coronary interventions (-59%) and in STEMI care (-51%).11 In a Taiwanese study, although there was no reduction in STEMI admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant delay in seeking medical help was found.12 While the pandemic started later in the USA than in Europe, a study on two US centers also observed a 9.5% reduction in patients diagnosed with STEMI in March 2020 compared to March 2019.5 Another study, based on data from 21 medical centers in Northern California, showed that the weekly rates of hospitalization for MI decreased by up to 48% following the first reported death from COVID-19 on March 4, 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.6 Garcia et al.7 also observed a 38% reduction in activation of cardiac catheterization laboratories for STEMI in the USA. A study by Tam et al.8 in Hong Kong, China, drew attention to the impact of COVID-19 in time components of STEMI care. Patient delay was 318 min during the epidemic period and 83 min in the previous period.8 Information on increases in patient delay and system delay is still scarce but, given that widespread saturation of health systems has been observed, particularly in terms of emergency and intensive care, it is plausible that STEMI patients could have been impacted in terms of timely access to PPCI.

The causes for the reduction in the number of PPCI procedures are probably multifactorial and we can only speculate. What is certain is that the number of patients admitted to hospitals and treated by PPCI was reduced. The most obvious explanation is that patients avoided hospitals for fear of becoming infected, but we also have no data to refute the possibility of a real reduction in the incidence of acute coronary syndromes. However, based on the Lombardia Cardiac Arrest Registry, Baldi et al.17 compared out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) during the pandemic period in Italy with the same period in 2019 and observed an increase of 58% in OHCA, which supports the hypothesis that ACS patients chose not to go to the hospital.

The mission of the SSL global initiative13, 14 is to reduce mortality from MI. Patient delay, i.e. the time from symptom onset until patients seek medical attention, has multifactorial causes, but results largely from a failure to correctly identify the symptoms of a potential ACS and, in countries with less resources or without organized networks, from patients’ difficulties in reaching health services.18, 19 At a time when people are facing a highly infectious disease, while flooded with televised images of disrupted hospitals and constantly warned to stay at home by the authorities, the natural reaction is to disregard the symptoms and avoid going to the hospital.

Finally, it is also unclear whether there was in fact a reduction in the number of ACS during the study period. Decreases in physical exercise due to lockdown, the adoption of teleworking, reductions in atmospheric pollution and other related drastic changes in our habits may have had an effect on the stability of atherosclerotic plaques.20

It was soon realized that patients with COVID-19 had significant secondary cardiovascular disorders and complications; moreover, patients with a cardiovascular history were more likely to have unfavorable outcomes.21, 22 Guidelines have been issued on the management of both cardiovascular patients22, 23, 24, 25 and catheterization laboratories26, 27, 28 in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Medical societies are recommending the deferral of elective procedures. This means that, during this period, patients no longer have access to the important advances of recent decades in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease. It is still unknown how long the pandemic will last and how many months or years it will be necessary to work in a protected environment. The logistics needed to deal with COVID-19 issues, even outside infection peaks, require an enormous enhancement of material and human capabilities. Many of the SSL member countries were already struggling with severe scarcities of resources, which have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Governments and hospital administrations themselves, when trying to respond to public opinion, may tend to focus more on the COVID-19 crisis, neglecting cardiovascular disease to some extent. It is up to cardiology societies in general, and the SSL global initiative in particular, to argue that ACS patients should continue to receive the quality care that this condition deserves.

Limitations

The main limitations of this study are that it is retrospective and does not represent all the member-countries of the SSL global initiative. Another limitation lies in the fact that neither patient delay nor system delay times were obtained and that no data on mortality were provided. In a period when hospitals were under such strain, it would have been very difficult for the teams to obtain further prospective data in addition to what was requested.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in addition to the direct effects of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system, this pandemic may also increase mortality by reducing hospital admissions.

It is important for countries involved in the SSL global initiative to draw attention to the needs of patients with ACS in general, and STEMI in particular, by developing awareness campaigns for the public to recognize symptoms and to act swiftly. At the same time, appropriate efforts should be made to ensure that hospital organizations, when focused on treating COVID patients, do not neglect other patient cohorts, including those with ACS.

It is also important to ensure that diagnostic and therapeutic activity is gradually resumed in safe conditions for both patients and professionals.

In terms of the impact on daily practice, this survey clearly demonstrated an overall reduction in the numbers of patients hospitalized for ACS and PPCI procedures. Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease continues to be prevalent, and so it is necessary to warn decision makers not to forget this fact and to establish action plans and protocols that aim to overcome the barriers imposed by the pandemic crisis.

Funding

The authors state that they have no funding to declare.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating centers and researchers who collected the data, with particular acknowledgments to SSL Project Managers Rodab Almahady (SSL Sudan), Ka Chun Alan Chan (SSL Hong Kong), Babak Geraiely (SSL Iran), Georgia Lygkouri (SSL Greece), Ana Domingues (SSL Portugal), Anastasia Kochergina (SSL Russia), Nemanja Djenic (SSL Serbia), and Ignacio Cigalini (SSL Argentina).

The data underlying this article are available at https://www.dropbox.com/home/PROJECTOS/ARTIGOS%20EM%20EXECUCAO/DATA%20AVAILABLE/SSL%20survey.

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grasselli G., Pesenti A., Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020;323:1545–1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodríguez-Leor O., Cid-Álvarez B., Ojeda S., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interventional cardiology activity in Spain. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Filippo O., D’Ascenzo F., Angelini F., et al. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during COVID-19 outbreak in northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:88–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zitelny E., Newman N., Zhao D. STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic - an evaluation of incidence. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2020;48:107232. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon M., McNulty E., Rana J., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia S., Albaghdadi M., Meraj P., et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam C.F., Cheung K.S., Lam S., et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong-Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzler B., Siostrzonek P., Binder R., et al. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–1853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C., et al. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayol J., Artucio C., Batista I., et al. An international survey in Latin America on the practice of interventional cardiology during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a particular focus on myocardial infarction. Neth Heart J. 2020;28:424–430. doi: 10.1007/s12471-020-01440-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y.H., Huang W.C., Hwang J.J., et al. No reduction of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction admission in Taiwan during coronavirus pandemic. Am J Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.06.030. S0002-9149(20)30607-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widimsky P., Fajadet J., Danchin N., et al. ‘Stent 4 Life” targeting PCI at all who will benefit the most: a joint project between EAPCI, Euro-PCR EUCOMED and the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. EuroIntervention. 2009;4:555–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.https://www.stentsavealife.com/ [accessed 24.05.20]

- 15.https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/india?country=∼IND [accessed 26.07.20]

- 16.Pessoa-Amorim G., Camm C., Gajendragadkar P., et al. Admission of patients with STEMI since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. A survey by the European Society of Cardiology Heart Journal. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldi E., Sechi G., Primi R., et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:496–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira H., Calé R., Pinto F., et al. Factors influencing patient delay before primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the Stent for life initiative in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira H., Pinto F., Calé R., et al. The Stent for Life initiative: factors predicting system delay in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37:681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato A., Minami Y., Katsura A., et al. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute coronary syndrome caused by plaque erosion. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driggin E., Madhavan M., Bikdeli B., et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ESC guidance for the diagnosis and management of CV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Education-General/Topic%20pages/Covid-19/ESC%20Guidance%20Document/ESC-Guidance-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf [accessed 24.05.20]

- 24.Mahmud E., Dauerman H.L., Welt F.G., et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic: a position statement from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerkar P., Naik N., Alexander T., et al. Cardiological Society of India: document on acute MI care during COVID-19. Indian Heart J. 2020;72 doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welt F., Shah P., Aronow H., et al. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from ACC's Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romaguera R., Cruz-Gonzalez I., Ojeda S., et al. Consensus document of the Interventional Cardiology and Heart Rhythm Associations of the Spanish Society of Cardiology on the management of invasive cardiac procedure rooms during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo S., Yong A., Sinhal A., et al. Consensus guidelines for interventional cardiology services delivery during COVID-19 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:e69–e77. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]