Abstract

Introduction

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, regulations for substance use services changed to accommodate stay-at-home orders and physical distancing guidelines.

Methods

Using in-depth interviews (N = 14) and framework analysis, we describe how policymakers developed, adopted, and implemented regulations governing services for substance use disorders during COVID-19, and how policymakers' perceived the impacts of these regulations in New York State.

Results

During the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers shifted to more inclusive approaches of knowledge generation and co-production of recommendations. Barriers to adoption and implementation of new regulations included medication/services supply, lack of integration, stigma, and overcriminalization.

Conclusion

Findings from this study highlight the potential feasibility and benefits of co-produced policies for substance use services and the need for consistent service supply, better integration with health care services, reduced stigma, improved funding structures, best practice guidelines, criminal justice reform, and harm reduction support. These considerations should inform future policy maintenance and modifications to substance use services related to COVID-19.

Keywords: Qualitative, Implementation, Substance use services policy, COVID-19

1. Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state governments modified laws and administrative regulations for substance use disorder (SUD) services on a temporary basis to promote access that accommodated stay-at-home orders and physical distancing guidelines (Henry et al., 2020). Specifically, regulations changed providers' scope of care, medication prescribing/dispensing, and confidentiality/privacy (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020d) (Table 1 ). Changes also included definitions of essential services, scheduling and documentation requirements, and permissible modes of contact and reimbursement. Further, regulation changes pertaining to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) addressed the admission of new patients, prescribing of medications, treatments of existing patients, dispensation of medication, and role of providers (Bao et al., 2020). Regulation changes related to harm reduction programs expanded allowable modalities for psychoeducation and naloxone training and distribution (New York State Department of Health, 2020a).

Table 1.

Regulatory changes.

| Regulatory change | Effective dates |

|---|---|

| Telehealth/telemedicine | |

| Buprenorphine: initial visit and induction can now be conducted via telemedicine (follow up visits before/after change could be telemedicine) (Prevoznik, 2020). | 3/16/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Naltrexone: no change (all visits could be telemedicine before/after change; injection must be at a clinical site) | 3/16/2020 |

| Methadone: follow up visits can now be telemedicine (initial visit remains in person) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020b). | 3/16/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| All telemedicine visits may occur in homes (both provider and client); Medicaid was excluded from this prior to change (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020b). | 3/16/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Audio only visits may be used for all MOUD follow up visits (buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) (visual required before change) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020b). | 3/16/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Telemedicine does not need to be delivered via HIPAA compliant platform (needed to before change) – approved platforms include Doxy.me, Zoom (free), FaceTime, Skype, WhatsApp, FB Messenger, Google Hangouts (NOT permitted: FB Live, Twitch, TikTok); i.e., penalties waived during the emergency for not using HIPAA compliant telemedicine technologies (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020a). | 3/17/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Medication dosage | |

| In states with declared emergencies: exceptions for all “stable” patients in an OTP to receive 28 day take home doses of MOUD; 14 day take home medications for patients who are “less stable” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020c). | 3/16/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Reimbursement | |

| New York state Medicaid Only: parity with existing off-site or face to face visits (100% of Medicaid payment rate) – allows providers to be at home and receive parity on rates (Cuomo et al., 2020a, Cuomo et al., 2020b). | 3/23/2020 & 3/27/2020 - until the disaster emergency declared by NYS Executive Order No. 202 ends |

| Licensing | |

| Temporary, emergency, or fast-tracked licensure, or the temporary waiver of certain licensure requirements for health care providers (McDermott, 2020) | 3/25/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Confidentiality provisions | |

| CARES legislation aligned 42 CFR Part 2 with HIPAA protections (i.e., a loosening of confidentiality protections for covered entities) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020a) | Legislation passed; SAMHSA has 1 year to clarify rule; 3/17, 3/27, and 3/30 |

| Naloxone | |

| Naloxone provided by mail; No mandate on providing rescue breathing (New York State Department of Health, 2020a). | 3/30/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

| Harm reduction | |

Harm reduction coalition: syringe service and harm reduction provider operations:

|

3/11/2020 - until the public health emergency ends |

The rapid change in SUD services regulations due to COVID-19 offers an opportunity to document impacts and policymaking processes to inform future policy decisions. Documenting these changes is important because historically limited research has existed on the policymaking process (Purtle et al., 2015), particularly in the area of SUD service regulations (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). Understanding policymaking processes that result in the adoption and implementation of evidence-based policies can elucidate practical strategies to increase the development of evidence-based policies, which are greatly needed to address the high rates of mortality among people with SUD.

The purpose of this paper is to describe 1) how regulations governing services for SUD during COVID-19 were developed, adopted, and implemented, as well as 2) perceived impacts of regulations and recommendations for policies to be maintained. Our research is responsive to calls for qualitative research to identify policymaker perspectives on the policy implementation process (Meisel et al., 2019) and the advancement of policy dissemination and implementation research to fill gaps in translation (Purtle et al., 2015). We do this by using in-depth interviews with policymakers in New York State.

The study is guided by the Framework for Dissemination of Evidence-Based Policies, which describes policymaking development and dissemination process (Purtle et al., 2017). Research with this framework highlights how development, implementation, and adoption often takes years, through a mostly top-down, linear approach whereby policymakers (i.e., legislators, governmental administrators, and lobbyists) build consensus on how to address shared goals (Brownson et al., 2017). While this process may include formal channels for public input, such as solicitation of public comment from stakeholders delivering services or consumers, these opportunities are usually structured so that information flows unidirectionally back to high level policymakers during pre-established points early in the process. The framework informed study design and methods, and guided analyses and data interpretation.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling & recruitment

We sampled key informants from policymaking organizations involved in developing and supporting the implementation and adoption of regulations governing SUD services in New York State. The study broudly defined policymaking to include decision-making that influences SUD service regulations development, implementation, and adoption (Meisel et al., 2019). We relied on a previously published definition of policymaker that encompasses this broad perspective:

Policy-makers are individuals at some level of government or decision-making institution, including but not limited to international organizations, non-governmental agencies or professional associations, who have responsibility for making recommendations to others.

As such, we recruited participants from state and local governments (including health related executive departments and state legislature), as well as nongovernmental patient and professional organizations involved in SUD services advocacy, from both patient and provider perspectives. We recruited additional organizational representatives by asking each participant for suggestions of other key stakeholders, both within and outside of their organizations (Marshall, 1996; Patton, 1990). We recruited via email; 91% of people who we emailed agreed to participate, one organization did not respond to the invitation. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board reviewed the study and deemed it exempt.

2.2. Data collection

We conducted semistructured in-depth interviews between July and October 2020. The study offered participants $75 for completing the interview; several individuals were unable to accept compensation due to organizational regulations. Interviews occurred remotely using a video-conferencing platform and lasted 30–54 min. The interview guide incorporated topics from the previously described Framework for Dissemination of Evidence-Based Policies (Purtle et al., 2017). Questions addressed how organizations developed and supported implementation/adoption of regulatory changes related to SUD services due to COVID-19. Questions were open-ended and included probes to further explore participants' responses. See Appendix 1 for the full interview guide.

The same interviewer (first author) conducted all interviews. Given the small number of participants, the team preferred to use a single interviewer to promote consistency in the use of the interview guide and to promote prolonged engagement (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). Prolonged engagement is the process by which a qualitative researcher becomes immersed in the data through exposure to repeated themes, which can allow the researcher to confirm new information during the course of data collection by seeking multiple perspectives on the same topic (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). For example, the interviewer is able to identify potential themes during data collection and then conduct member checking, or respondent validation, by asking participants to comment on if they believe preliminary themes are valid (Lietz et al., 2006).

2.3. Data analysis

We recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded the interviews, with two coders reading each transcript. We developed an initial codebook from the interview guide and the Framework for Dissemination of Evidence-Based Policies. The team added additional codes during the coding process. Expected codes derived from the framework included: 1) policy development (i.e., critical feedback is solicited by target audience and incorporated into policies), 2) adoption (i.e., decisions to undertake a policy), 3) implementation (i.e., policy is applied with fidelity), and 4) maintenance (i.e., policy is embedded) (Purtle et al., 2017).

Using a framework analytic approach (Gale et al., 2013), the study team mapped codes to the conceptual model, determining broad themes and subthemes. We mapped emergent themes to this framework in a spreadsheet and repeatedly condensed them to produce a thematic map that depicts how themes related to the conceptual framework. We flagged coding discrepancies and then discussed them until we achieved consensus and coders agreed that saturation of codes had occurred. We kept an audit trail of the analysis process to enhance dependability and confirmability (Korstjens & Moser, 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Description of the sample

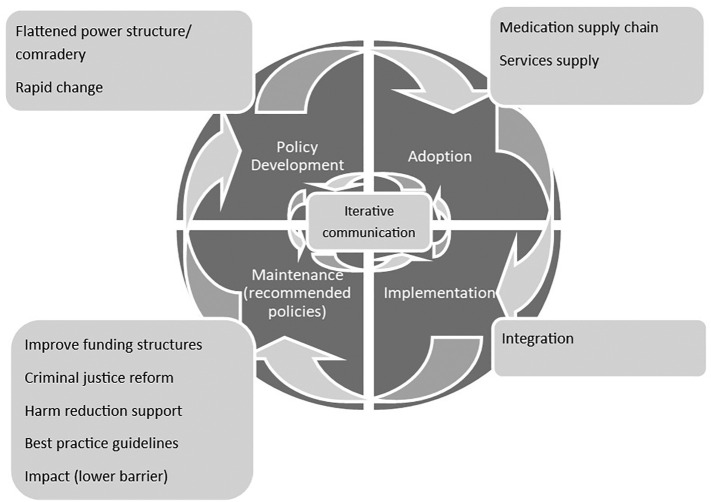

The sample included 14 individuals from 10 organizations: state/local government (5 organizations with 9 participants) and nongovernmental organizations (5 organizations/ participants). Fig. 1 depicts results of the framework analysis, which maps themes to the Framework for Dissemination of Evidence-Based Policies. The wedges inside the circle show the elements from the framework. We modified the shape of the figure to be circular and added arrows to denote “iterative communication” instead of a linear top-down model with passive and active dissemination. In the outer boxes, we depict the emergent themes relevant to each of the framework's areas (Fig. 1). The themes are discussed in detail next.

Fig. 1.

Thematic map.

3.2. Iterative communication & policy development process

Iterative communication was a key component of the New York State modified SUD regulation development process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike the traditional top-down, linear approach common to policy development, participants described repeated and open communication channels between state-level policy developers and end users within addiction treatment organizations. Multiple participants described engaging in daily “town hall” style virtual meetings with providers to both explain regulatory changes and solicit feedback on barriers and facilitators of implementation that they used to change policies, effectively “co-producing” policy with end users. For example, participants reported using information learned in these meetings to immediately revise regulations to better meet providers' and patients' needs. One participant from a patient advocacy organization highlighted this phenomenon in the following quote where they describe rapid changes after providers raised unforeseen negative consequences of a regulation.

[As part of] the Expanded Syringe Access Program… pharmacies were not allowed to advertise that they had syringes in stock. But then within four weeks, I got another email that said effective immediately the pharmacies were allowed to advertise - that they amended it…that was a…decision that they quickly changed in light of COVID.

3.2.1. Flattened power dynamic, comradery & rapid change

“Flattened power dynamics and comradery” and “rapid change” facilitated bi-directional communication. All participants described how the urgency of responding to COVID-19 restrictions, combined with the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic, changed the usual process of policy development and implementation to be less hierarchical and more collaborative. In the quote below, one of the participants who represented a patient advocacy group described how diverse stakeholders came together to make sense of changes and develop processes to meet patient needs.

The information was happening so quickly that we actually were catching discrepancies. And there were…different interpretations, for example, of DEA regulations… the first visit of a - Buprenorphine visit by telemedicine was hotly disputed. It was not clear whether it was allowed for it to be over a telephone, without a two-way video communication. We were just getting inundated with emails… It was a really chaotic month for us, and trying to share that. We try to share it to people who just are on the ground, who are doing the work, who are using drugs. And at the same time, trying to filter all that information down and have it be as accurate as possible in the moment… And we were talking about, was this going to be permanent? How is this going to help? What else needed to be done to see if we could benefit from any of these regulatory changes in a more permanent way.

As described in this quote, the policy development process centered information from patients and providers on the ground to modify policies in real time. Policymakers described using field offices to communicate with providers and understand patients' needs at a local level. These forums leveraged trusted existing relationships between policymakers and provider organizations and deepened those ties by opening real-time lines of communication and establishing processes to troubleshoot challenges between meetings. In this way, a distinct sense of comradery emerged that participants described as novel. The next quote highlights this process during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our field offices have very close relationship with the providers. There's a pretty constant exchange of information…the barrier to communicate with us is pretty low. Providers do it for all sorts of reasons all the time. We leverage that. We took advantage of that to get feedback.

3.3. Adoption & implementation

3.3.1. Medication supply chain

Themes that policymakers raised related to adoption and implementation of policies centered on limitations in the supply of medications and services. One respondent summarized the problem with the medication supply chain by saying:

…the United States has a unique issue in that manufacturers can only manufacture so much of an opioid with the approval of the DEA, because the DEA is actually the entity that sets the quotas for what manufacturers can produce.

These quotas would have limited the ability of patients to immediately fill prescriptions for a larger supply of medications than usual (one of the regulatory modifications). Medication production quotas served as a barrier to adoption because organizations did not want to adopt policies that they could not feasibly implement. Rapid modifications to lift these quotas were crucial in increasing the supply of medications so that provider organizations could adopt policies that allowed them to prescribe and pharmacies to dispense longer prescriptions (e.g., 4 weeks instead of one week) to reduce visits.

3.3.2. Services supply chain

Policymakers were concerned that provider organizations would close without rapid changes to billing structures to allow for increased reimbursements for telehealth and less frequent medication dosing. Closures of service organizations would have prevented adoption of changes and reduced the supply of providers able to meet increasing need among patients. One participant described this as follows:

We just did what we thought we needed to do to help the programs to stay afloat because it's very important to preserve the capacity of the system to help keep the staff and the clients safe from COVID.

Regulatory changes to billing structures were a key component of maintaining services supply. As the next quote highlights, one important area of these changes relates to how opioid treatment programs are paid under fee-for-services reimbursement, where fewer visits mean reduced revenue that threatens programs' financial viability. As a result, reimbursement needed to shift to a capitated model.

Most of the programs lost huge amounts of third-party Medicaid revenue since whenever they were giving patients more than a one-week supply, they simply wouldn't get paid for the other medication or the services that would be reimbursed, whether it's telehealth or basically telephone communication.

3.3.3. Integration

Lack of integration across service types was a main theme in implementation. Participants described a lack of integration between substance use services and three other areas: 1) general medical services, 2) mental health services, and 3) harm reduction services. One participant described how SUD service providers “were not included in the list…of health care providers…who were granted immunity from liability” due to COVID-19, and how they were initially unable to access emergency funding for PPE. Another participant described “strong resistance, [to implementing substance use medication policies among mental health services] because historically, there's been a divide between mental health and substance use.” Participants repeatedly highlighted harm reduction services as being initially left out of the policy development conversation. For example, guidelines did not initially include syringe service workers in the list of essential workers, even though substance use treatment providers were included. However, due to rapid change and bidirectional communication, the guidelines addressed this within days.

3.3.4. Stigma

Participants reported that stigma perpetuates the lack of integration. For example, one participant described the divide between harm reduction and other substance use services as driven by stigma:

I think even though we've come a long way in terms of lawmakers and their staff recognizing the value of harm reduction and syringe services, how much they are really part of the fabric of healthcare provision in this county, it is still kind of considered like a low priority. There is still some stigma and, depending on the office, sometimes a lot of stigma or dismissive attitude towards this work.

Participants also identified how stigma limited providers' interest in implementing what was perceived as permissive policies. For example, one state agency director described how providers' stigma toward patients using methadone led to a belief that extended take-home doses of methadone should be limited, earned very gradually and only through long-term compliance with program guidelines. Because of this perspective, providers sometimes required patients to come into the program daily, even though regulatory changes meant they were eligible for a multi-day supply of medication.

3.4. Maintenance (recommended policies)

3.4.1. Impact (lower barrier)

Participants voiced unanimous support for the maintenance of regulatory modifications to promote “lower barrier” addiction services. Many participants were quite enthusiastic, reporting that the policies were “game changing” and that they should maintain “anything to increase access” to services. The following quote highlights how telehealth can lower the barrier to accessing substance use services:

For them, it's much more around transportation and managing your family. And so, it's easier to do a telehealth visit, rather than take your kid and your other two kids. You can only go after school, but what if you have to work all day? All of those kinds of things. There's been a lot of that burden of just access that I think has been relieved.

3.4.2. Improve funding structures

Despite this strong support, stakeholders acknowledged that there is a need to improve funding structures to support the fiscal viability of maintaining these changes. Participants highlighted billing structures related to complexity and daily reimbursement for methadone dispensation, for example, as needing to change. One participant highlighted how temporary changes to allow for opioid treatment programs to bill through a bundled payment could be maintained as a long-term solution, describing these billing structures as ideal “for patients that are really truly stable in treatment like at the point where they just don't need any more counseling…like a maintenance patient.” Participants also called for continuity of parity in payment for services delivered via telehealth, along with flexible funding mechanisms to support patients with technology by maintaining similar reimbursement for telephonic, video-delivered telehealth, and in-person services.

3.4.3. Best practice guidelines

Policymakers also acknowledged that just because policies allowed care to be provided in new ways (for example via telehealth), that best practice guidelines would need to be established to give providers information on how to determine which modality of care to use with different patient populations to promote “patient-centered care.” One participant highlighted this in the following quote:

It's the trade off with convenience, and making sure that that's working, and yet, really checking in and making sure that people are getting care that they really need…this is where it's a program and clinical work. And those are what the policies of the program need to be. Those are the things that - these are standards. This is where it's a best practice issue. Not necessarily a regulatory issue, but certainly where the guidance has to start to look.

3.4.4. Criminal justice reform & harm reduction support

Several policymakers highlighted how criminal justice and substance use services policies overlap. For example, policymakers described how possession of syringes can be illegal, which can drive injection drug users to reuse needles rather than purchasing clean needles at a pharmacy. They explained that reusing needles can lead to poorer health outcomes and carrying old needles can risk arrest, both of which can disrupt insurance and receipt of substance use services. During COVID-19, syringe policies changed to allow substance users to carry a larger supply of clean needles. Syringe policy changes, combined with other COVID-19-related decarceration policies, reduced arrests and incarceration for low-level offenses, particularly those related to substance use. Policymakers endorsed expanding and maintaining “de-penalization of syringes for possession and purchase”, which would allow pharmacies to sell unlimited syringes. Several participants discussed the importance of continued decarceration and diversion as a way of “break[ing] that long-term cycle [in and out of jail], which everyone knows in this sphere is destructive.”

4. Discussion

Our findings reveal how the unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic and co-occurring opioid overdose epidemic fostered rapid policy development, adoption, and implementation processes that deviated from the traditional linear process described in the Framework for Dissemination of Evidence-Based Policies. We also highlight how themes aligned with the elements of the framework related to adoption, implementation, and maintenance, even though the process differed substantially. We describe how medication/services supply, lack of health care integration, stigma, and overcriminalization were barriers to adoption, implementation, and maintenance of policies. While some of the policy changes made progress toward addressing these barriers, due to the emergency nature of the regulatory changes whether changes will be maintained or further modified is unclear.

4.1. Policy development process

The environmental context stemming from the pandemic and ongoing opioid overdose epidemic allowed policymakers to shift from the traditional top-down policy development approach described in our conceptual framework (Purtle et al., 2017), to one that was more aligned with critical policy analysis, as highlighted by our findings related to bi-directional communication and inclusive approaches to policy development. Similar to our findings, critical policy analysis is a policymaking approach that uses inclusive strategies to generate knowledge and co-produce recommendations; critical policy analysis also identifies the impact of policies on marginalized groups (Cairney, 2020). Co-production of policy is also associated with enhanced legitimacy, which can improve compliance (Weible et al., 2020) and ultimately produce positive health outcomes. Our findings highlight how in New York State bi-directional communication channels and a flattened power dynamic evolved to co-produce policies with end-users, while attending to the disparate impact of policies on marginalized groups, like syringe services workers.

In the United Kingdom, early research on COVID-19-related policymaking identified a similar “trial and error” approach of “adaptive policymaking” (Cairney, 2020), which relied heavily on trusted relationships (Cairney & Wellstead, 2020). Lessons learned from our study suggest how critical policy analysis can work when stakeholders have trusting relationships and operate to reach a common goal (i.e., maintaining services for people with substance use disorders), and standard bureaucratic pathways are relaxed. How critical policymaking might facilitate diffusion of innovation and how to maintain the successful aspects of a nimble process during times when an “all-hands-on-deck” dynamic is not in place remain questions. Two factors seem especially relevant: (1) more real-time feedback loops (e.g., ongoing “town hall” style communication) and (2) streamlined flow of information from federal agencies to state agencies to community organizations.

4.2. Adoption, implementation, & maintenance

While the structure of the policy development process deviated from our conceptual model, themes related to barriers in the process mapped closely with the framework (adoption, implementation, and maintenance). Barriers included medication/services supply, lack of integration, stigma, and overcriminalization. For example, addiction services continued to operate in silos across harm reduction, to addiction specialty programs, and general health care settings. These differences included funding, resources, restrictions and regulations on patient services, and the subsequent stigma. Examples included who was initially considered essential workers and access to needed resources like personal protective equipment. Integration between SUD services and primary medical care is a potential mechanism for addressing this gap in services (Donohue et al., 2018). Similar to our findings, stigma is described as a potential barrier to integration (Adams & Volkow, 2020), and a facilitator of criminalization (Corrigan et al., 2017). Changes to policies during COVID-19 may help to address some of these longstanding problems. For example, loosening restrictions in service provision allowed for greater innovation and flexibility in reimbursement, which appeared to improve service supply.

4.3. Limitations

Our sample size included 14 organizational representatives from the major policy organizations active in New York State. However, other policy organizations exist from which we did not interview anyone. Further, the perspectives provided by the representatives who we did speak to are not necessarily generalizable to the other members of their organizations. However, this limitation is inherent in all qualitative research, which seeks to provide in-depth explanations rather than wide generalizability (Carminati, 2018).

By design, our sample included only policymakers in nonservices organizations. Use of this sample provides a unique perspective into the process of policy development, but it offers only one side of the adoption and implementation process. Additional research from the perspective of services organizations should seek to fully understand the implementation process. Findings from our study will inform our future research on the implementation of the regulations using a cross-sectional survey of providers. Our study also focused on the processes of policy development, implementation, and adoption rather than the impacts of policy changes. Therefore, future research should measures patient-level outcomes and patients' perspectives of policy changes.

4.4. Recommendations

Findings highlight the potential feasibility and benefits of using a critical policy development process to co-produce policies for SUD services. We also highlight how barriers to SUD services adoption, implementation, and maintenance may hinder gains if not explicitly addressed in policy. Given that overall policymakers were enthusiastic about the opportunities resulting from the rapid change brought on by the pandemic, addressing these barriers to maintain innovations may facilitate nimbler, patient-centered service delivery.

Policy recommendations based on results suggest that any future roll back of changes to SUD services regulations should be done slowly and that there should be careful consideration of maintaining policies that have had favorable outcomes. In fact, in many cases, participants reported enthusiasm at the opportunity to rethink traditional policies and service provision moving forward, using the loosened restrictions as a model to innovate addiction treatment. Policies previously considered “low threshold” or the purview of harm reduction services could have a place in specialized treatment programs. In fact, other researchers identified how such programs are being successfully adapted in Rhode Island (Samuels et al., 2020). Lower barrier service models might include fewer in-person visits to better accommodate work schedules and allow for patient-centered take-home medication schedules. Guidelines should address challenges related to billing structure, and programs should re-evaluate best practice guidelines so that services have fidelity and continuity.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Interview guide

Funding information

Research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Award Number: T32DA03780). Content is the author's sole responsibility and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The Columbia University Center for Healing of Opioid and Other Substance Use Disorders—Intervention Development and Implementation (CHOSEN) provided administrative support and funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors do not have any disclosures to declare.

References

- Adams V.J.M., Volkow N.D. Ethical imperatives to overcome stigma against people with substance use disorders. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2020;22(8):702–708. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y., Williams A.R., Schackman B.R. COVID-19 can change the way we respond to the opioid crisis – For the better. Psychiatric Services. 2020 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R.C., Colditz G.A., Proctor E.K. Oxford University Press; 2017. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney P. The UK government’s COVID-19 policy: Assessing evidence-informed policy analysis in real time. British Politics. 2020 doi: 10.1057/s41293-020-00150-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney P., Wellstead A. COVID-19: Effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians, and the public. Policy Design and Practice. 2020:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carminati L. Generalizability in qualitative research: A tale of two traditions. Qualitative Health Research. 2018;28(13):2094–2101. doi: 10.1177/1049732318788379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet Retrieved from.

- Corrigan P., Schomerus G., Shuman V., Kraus D., Perlick D., Harnish A.…Smelson D. Developing a research agenda for understanding the stigma of addictions part I: Lessons from the mental health stigma literature. The American Journal on Addictions. 2017;26(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo A.M., Zucker H.A., Frescatore D. Comprehensive guidance regarding use of telehealth including telephonic services during the COVID-19 state of emergency. 2020. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/update/2020/no05_2020-03_covid-19_telehealth.htm

- Cuomo A.M., Zucker H.A., Frescatore D. New York state medicaid coverage and reimbursement policy for services related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/update/2020/no07_2020-03_covid-19_reimbursement.htm

- Donohue J.M., Barry C.L., Stuart E.A., Greenfield S.F., Song Z., Chernew M.E., Huskamp H.A. Effects of global payment and accountable care on medication treatment for alcohol and opioid use disorders. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B.F., Mandavia A.D., Paschen-Wolff M.M., Hunt T., Humensky J.L., Wu E.…El-Bassel N. COVID-19, mental health, and opioid use disorder: Old and new public health crises intertwine. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S111–S112. doi: 10.1037/tra0000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstjens I., Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. The European Journal of General Practice. 2018;24(1):120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietz C.A., Langer C.L., Furman R. Establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research in social work: Implications from a study regarding spirituality. Qualitative Social Work. 2006;5(4):441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M.N. The key informant technique. Family Practice. 1996;13:92–97. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott W. 2020. DEA-067 letter. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel Z.F., Mitchell J., Polsky D., Boualam N., McGeoch E., Weiner J.…Cannuscio C.C. Strengthening partnerships between substance use researchers and policy makers to take advantage of a window of opportunity. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2019;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0199-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors COVID-19: Suggested health department actions to support syringe services programs (SSPs) 2020. https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/covid-19_hd_recommendations_for_ssp_support_final_04.06.20.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA strategic plan: 2016-2020. 2015. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/nida_2016strategicplan_032316.pdf Bethesda, MD Retrieved from.

- New York State Department of Health COVID-19 guidance for opioid overdose prevention programs in New York state. 2020. https://nyoverdose.org/docs/program_covid19_guidance.pdf

- New York State Department of Health COVID-19: Guidance for people who use drugs. 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-people-use-drugs-guidance.pdf

- Patton M.Q. SAGE Publications, inc; 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. [Google Scholar]

- Prevoznik T.W. 2020. DEA-068 letter. [Google Scholar]

- Purtle, J., Dodson, E. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2017). Policy dissemination research. In R. C. Brownson, Graham, A. C., Proctor, E. K. (Ed.), Dissemination and implementation research health: Translating science to practice. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190683214.003.0026. [DOI]

- Purtle J., Peters R., Brownson R.C. A review of policy dissemination and implementation research funded by the National Institutes of Health, 2007–2014. Implementation Science. 2015;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0367-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels E.A., Clark S.A., Wunsch C., Jordison Keeler L.A., Reddy N., Vanjani R., Wightman R.S. Innovation during COVID-19: Improving addiction treatment access. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(4):e8–e9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2020. EAP and COVID-19: COVID-19 public health emergency response and 42 CFR part 2 guidance. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Opioid treatment program (OTP) guidance. 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Opioid treatment program (OTP) guidance. 2020. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf Retrieved from.

- Tricco A.C., Zarin W., Rios P., Nincic V., Khan P.A., Ghassemi M.…Langlois E.V. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: A scoping review. Implementation Science. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0717-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vital Strategies Incorporated Safer drug use during the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020. https://www.vitalstrategies.org/wp-content/uploads/Safer-drug-use-during-the-COVID-outbreak.pdf

- Vital Strategies Incorporated Syringe services and harm reduction provider operations during the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020. https://www.vitalstrategies.org/wp-content/uploads/Syringe-Services-and-Harm-Reduction-During-COVID-19-Outbreak.pdf

- Weible C.M., Nohrstedt D., Cairney P., Carter D.P., Crow D.A., Durnová A.P.…Stone D. COVID-19 and the policy sciences: Initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sciences. 2020;53(2):225–241. doi: 10.1007/s11077-020-09381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Interview guide