Abstract

Objective:

To analyze timing and sites of recurrence for patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer.

Background:

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection is standard treatment for locally advanced gastric cancer in the West, but limited information exists as to timing and patterns of recurrence in this setting.

Methods:

Patients with clinical stage II/III gastric cancer who were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by curative-intent resection between January 2000 and December 2015 were analyzed for 5-year recurrence free survival (RFS), timing and site of recurrence.

Results:

Among 312 identified patients, with a median follow-up of 46.0 months, 38.8% (121) patients experienced recurrence with an overall 5-year RFS rate of 58.9%; 95.8% for ypT0N0, 81.0% for ypStage I, 77.4% for ypStage II, and 22.9% for ypStage III. First site of recurrence was peritoneal in 49.6%, distant (not peritoneal) in 45.5 %, and locoregional in 11.6%. The majority (84.3%) of recurrences occurred within 2 years. Multivariate analysis revealed that ypT4 status was an independent predictor for recurrence within 1 year after surgery (OR 2.58 [95% CI 1.10–6.08], p = 0.030).

Conclusions:

The majority of recurrences in patients with clinical stage II/III gastric cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent curative resection occurred within 2 years. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pathologic T stage was a useful risk predictor for early recurrence.

Introduction

Perioperative chemotherapy, including neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, has been a standard treatment for locally advanced gastric cancer since several phase III trials proved its benefit compared to surgery alone in the last 10 years 1–4. Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves the cure rate compared with resection alone 5,6, gastric cancer still recurs in 25–40% of patients 7,8. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used to treat patients with locally advanced tumors that are likely to have nodal involvement and thus more likely to have micrometastatic disease. As such, beginning treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy may clear micrometastases as well as reduce the size of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes prior to definitive resection. However, proponents of adjuvant treatment may argue that upfront resection allows for definitive local control, after which patients can receive definitive treatment for residual micrometastatic disease, thus decreasing the burden of disease treated using chemotherapy. If a patient has an operative complication, however, this could result in delay or even deferral of recommended adjuvant treatment.

As recurrence is a major predictor of death from disease 7–12, understanding patterns of recurrence is crucial to improving the strategy of postoperative treatment and follow-up. These patterns have been described, but the majority of studies include patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy 7–19. Two studies of recurrence patterns have included patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, but neither specifically focused on patients with gastric adenocarcinoma (i.e. they included gastroesophageal junction cancers) with several years’ follow-up 7,8. The aim of this study was to determine the concordance of these previously described patterns of recurrence with those in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by curative-intent operation for gastric cancer.

Methods

Patient characteristics and clinicopathological data

All patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and retrospective review was approved by our institutional review board. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics, and treatment information were collected from the prospectively maintained surgical gastric cancer database and electronic medical record. Inclusion criteria were histologically confirmed primary gastric adenocarcinoma of clinical stage II or III, receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and R0 resection between January 2000 and December 2015. Exclusion criteria were clinical stage I, IV, or unknown, and incomplete data regarding recurrence site. Tumor depth (T stage), lymph node status (N status), and TNM stage were classified according to the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system 20. Clinical and pathological TNM staging were classified according to the cTNM and ypTNM staging systems, respectively 21. Clinical TNM stage was determined by CT scan and endoscopic ultrasonography. Staging laparoscopy was commonly used for staging before treatment to rule out occult metastatic disease (determined by peritoneal nodules or positive peritoneal cytology). Patients who were pathologically diagnosed as positive cytology by staging laparoscopy were categorized into clinical stage IV. Patients with clinical stage ≥ T3 and/or node-positive disease were offered neoadjuvant treatment. Pathological chemotherapy response was assessed by an experienced gastric cancer pathologist on a scale from 0 to 100%.

Follow-up

Follow-up after resection consisted of visits to the outpatient department with blood tests (complete blood count, chemistry panel, and sometimes carcinoembryonic antigen level and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 level) and a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 3–6 months for the first 2 years and every 6–12 months for years 3–5. Survival was measured from the date of surgery, and recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured to the date of recurrence, date of death of any cause, or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. All records were reviewed by a second oncologist, and outside correspondence was reviewed to capture patients who received follow-up tests outside our center. The date of recurrence was the date of pathological diagnosis or date of CT scan if no pathology was obtained. The sites of first recurrence were categorized as peritoneal metastasis (including ovarian metastasis), distant metastasis excluding peritoneal metastasis, or locoregional recurrence. Locoregional recurrence included the anastomotic site, gastric bed, and lymph nodes at the gastric bed or in the extent of the D2 resection, as determined by confirmatory radiographic imaging or by biopsy. Distant metastasis included sites outside of the locoregional definition, including hematogenous metastasis and lymph node metastasis outside the extent of the D2 resection. Overall survival (OS) after recurrence was measured from the date of recurrence to date of death from any cause or last follow-up, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics, clinicopathological characteristics, recurrence date and site, and survival were examined. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables using a Mann-Whitney U test. Survival was described using the Kaplan-Meier method and survival differences evaluated using log-rank test and Cox regression analysis. Univariable analyses were performed for all potential confounding variables and effect modifiers. Considering sample size, all variables with a significance level of p < 0.1 in the univariable analysis were included as independent variables in the multivariable analysis. Data were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]), odds ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval), or hazard ratio (HR; 95% confidence interval), unless otherwise stated. P values of < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical calculations were conducted using SPSS® software version 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). The cumulative incidence of recurrence among recurrence sites was compared by competing risk analysis using R software version 3.6.3 (http://www.r-project.org) 21.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 1,144 patients who underwent R0 gastrectomy for primary gastric cancer between January 2000 and December 2015 at our center, 799 patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 32 patients whose cancer was clinical stage I, IV, or unknown, and 1 patient with unknown recurrence site were excluded. Demographics, clinicopathological characteristics, and operative and pathological findings of the study cohort (n = 312) are shown in Table 1. Stage distribution was near equal, with 148 (47.4%) and 164 (52.6%) patients with clinical stage II and III cancer, respectively, before preoperative treatment. Most (211; 67.6%) patients received anthracycline + 5-FU + platinum neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A small fraction (9; 2.9%) received neoadjuvant radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy. Nearly half of patients (150; 48.1%) also received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas few received radiotherapy (19; 6.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics. Categorical data are given as n (%) and continuous data as median (IQR).

| No recurrence (191) | Recurrence (121) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 115 (60.2) | 67 (55.4) | 0.398 |

| Age, years | 63 (54–70) | 62 (52.5–70) | 0.703 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.6 (24.0–29.3) | 25.9 (23.1–28.8) | 0.163 |

| Year of surgery | 0.084 | ||

| 2000–2010 | 85 (44.5) | 66 (54.5) | |

| 2011–2015 | 106 (55.5) | 55 (45.5) | |

| Tumor location | 0.408 | ||

| Upper third | 53 (27.7) | 35 (28.9) | |

| Middle third | 56 (29.3) | 42 (34.7) | |

| Lower third | 80 (41.9) | 41 (33.9) | |

| Whole stomach | 2 (1.0) | 3 (2.5) | |

| cT | 0.013 | ||

| 1 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 | 7 (3.7) | 3 (2.5) | |

| 3 | 89 (46.6) | 36 (29.8) | |

| 4 | 94 (49.2) | 82 (67.8) | |

| cN positive | 104 (54.5) | 71 (58.7) | 0.463 |

| cStage | 0.306 | ||

| II | 95 (49.7) | 53 (43.8) | |

| III | 96 (50.3) | 68 (56.2) | |

| Neoadjuvant regimen | 0.050 | ||

| Anthracycline + 5-FU + platinum | 137 (71.7) | 74 (61.2) | |

| Platinum-based doublet | 20 (10.5) | 27 (22.3) | |

| FOLFOX | 19 (9.9) | 10 (8.3) | |

| Taxane + 5-FU +platinum | 9 (4.7) | 8 (6.6) | |

| Other | 6 (3.1) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 7 (3.7) | 2 (1.7) | 0.301 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 87 (45.5) | 63 (52.2) | 0.262 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 5 (2.6) | 14 (11.6) | 0.001 |

| Type of gastrectomy | 0.224 | ||

| Distal | 106 (55.5) | 55 (45.5) | |

| Total | 81 (42.4) | 63 (52.1) | |

| Proximal | 4 (2.1) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Number of dissected nodes | 25 (19–32.5) | 24 (18–31) | 0.260 |

| ypT | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 25 (13.1) | 2 (1.7) | |

| 1 | 33 (17.8) | 7 (5.8) | |

| 2 | 30 (15.7) | 11 (9.1) | |

| 3 | 72 (37.7) | 43 (35.5) | |

| 4 | 30 (15.7) | 58 (47.9) | |

| ypN | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 114 (59.7) | 21 (17.4) | |

| 1 | 45 (23.6) | 19 (15.7) | |

| 2 | 24 (12.6) | 27 (22.3) | |

| 3 | 8 (4.2) | 54 (44.6) | |

| yp Stage | < 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 45 (23.6) | 9 (7.4) | |

| 2 | 89 (46.6) | 25 (20.7) | |

| 3 | 32 (16.8) | 85 (70.2) | |

| Not classified (ypT0Nany) | 25 (13.0) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Tumor size, cm | 3 (1.6–5) | 4.1 (2.5–6.9) | < 0.001 |

| Pathological response, % | 40 (10–82.5) | 20 (5–50) | 0.001 |

| Lauren type | < 0.001 | ||

| Intestinal | 106 (55.5) | 39 (32.2) | |

| Diffuse | 47 (24.6) | 56 (46.3) | |

| Mixed | 33 (17.3) | 25 (20.7) | |

| Not reported | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Differentiation | 0.001 | ||

| Well | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Moderate | 76 (39.8) | 25 (20.7) | |

| Poor | 105 (55.0) | 93 (76.9) | |

| Not reported | 5 (2.6) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 79 (41.4) | 84 (69.4) | < 0.001 |

Recurrence-free survival

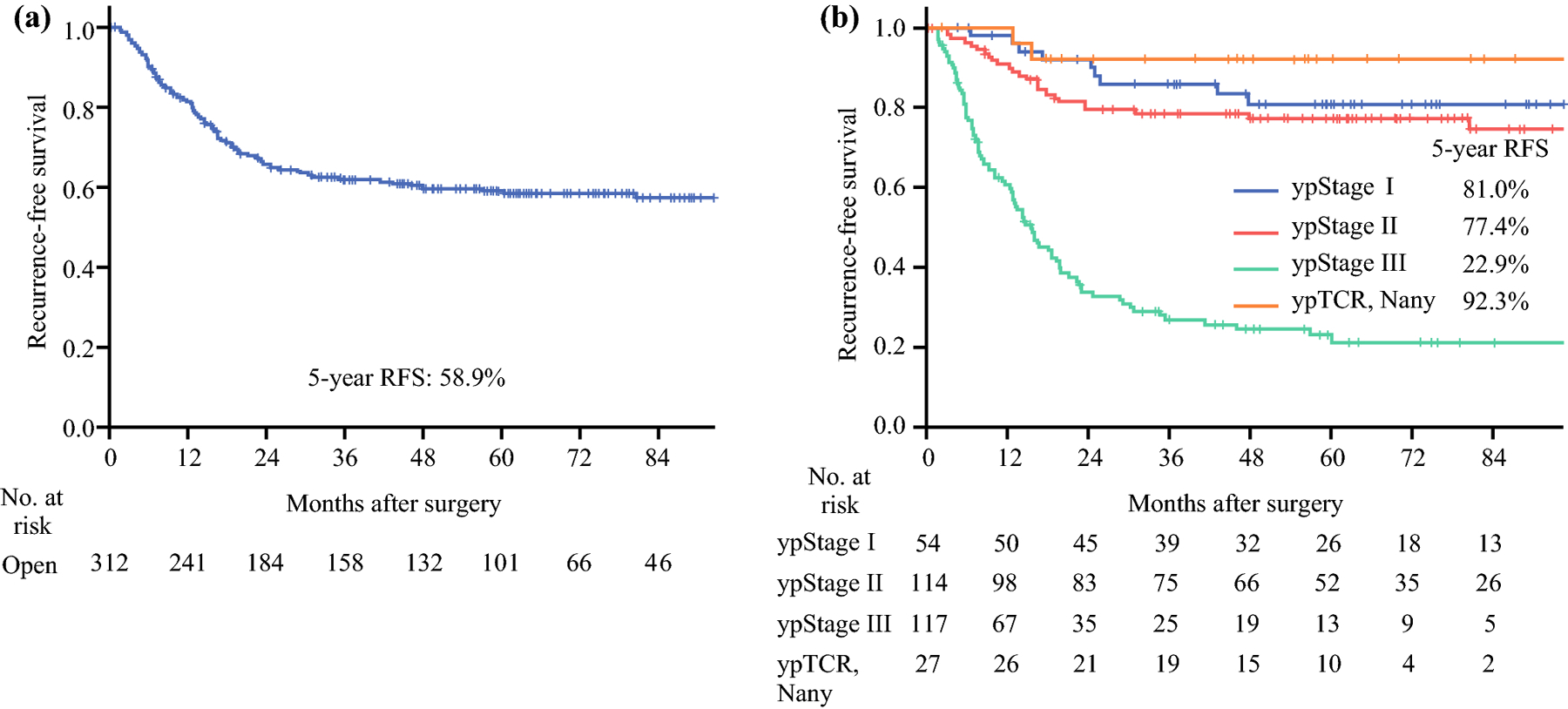

Of 312 patients, 121 (38.8%) patients had a recurrence during a median follow-up of 46.0 months. Median RFS among all patients was 37.0 (IQR 12.9–65.0) months. For the 121 patients who experienced recurrence, median RFS was 12.7 (IQR 6.2–19.4) months. The 5-year RFS in the total cohort was 58.9%, 81.0% for ypStage I, 77.4% for ypStage II, and 22.9% for ypStage III (Figure 1). Of 27 patients with ypT0, 3 patients had ypN positive status and all 3 patients recurred, whereas 1 of 24 patients with ypT0N0 had a recurrence. The 5-year RFS for patients with ypT0 was 92.3%.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for recurrence-free survival for the entire cohort (n = 312) (a) and by ypStage (b).

Predictors of RFS

Uni- and multivariable analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with RFS. Univariable analysis revealed that tumor size > 4 cm (p = 0.004), diffuse or mixed Lauren histology (p < 0.001), poor differentiation (p < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion (p < 0.001), ypT3 or higher, ypN positive status, adjuvant radiotherapy (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with worse RFS, and distal gastrectomy (p = 0.026) and pathological response rate > 75% (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with better RFS (Table 2). Multivariable analysis narrowed the list of factors to distal gastrectomy (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.45–0.97], p = 0.033) as predictive of better RFS rates, and ypT4 (HR 3.87 [95% CI 1.45–10.32], p = 0.007) and ypN positive status (ypN1 HR 2.18 [95% CI 1.03–4.60], p = 0.041; ypN2 HR 4.64 [95% CI 2.34–9.22], p < 0.001; ypN3 HR 11.84 [95% CI 5.92–23.67], p < 0.001) as predictive of worse RFS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with recurrence-free survival.

| Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age > 60 years | 0.94 | 0.66–1.34 | 0.730 | |||

| Female sex | 1.1 | 0.77–1.58 | 0.589 | |||

| Year of surgery, 2011–2015 | 0.75 | 0.52–1.07 | 0.116 | |||

| Tumor location in the middle or lower third | 0.82 | 0.560–1.21 | 0.316 | |||

| Distal gastrectomy (vs. total or proximal) | 0.67 | 0.47–0.95 | 0.026 | 0.66 | 0.45–0.97 | 0.033 |

| Tumor size > 4 cm | 1.69 | 1.18–2.43 | 0.004 | 0.8 | 0.53–1.19 | 0.270 |

| > 25 dissected nodes | 0.8 | 0.56–1.14 | 0.218 | |||

| Diffuse or mixed Lauren type | 2.22 | 1.52–3.26 | < 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.52–1.52 | 0.667 |

| Poor differentiation (vs. well or moderate) | 2.27 | 1.47–3.51 | < 0.001 | 1.17 | 0.65–2.11 | 0.603 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 2.66 | 1.80–3.93 | < 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.53–1.55 | 0.725 |

| cStage III (vs. II) | 1.29 | 0.90–1.84 | 0.168 | |||

| ypT | ||||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 2 | 1.64 | 0.63–4.22 | 0.308 | 1.48 | 0.51–4.31 | 0.473 |

| 3 | 2.54 | 1.14–5.65 | 0.022 | 1.87 | 0.75–4.69 | 0.179 |

| 4 | 6.4 | 2.91–14.06 | < 0.001 | 3.87 | 1.45–10.32 | 0.007 |

| 0 | 0.43 | 0.09–2.08 | 0.296 | 0.42 | 0.05–3.70 | 0.438 |

| ypN | ||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1 | 2.12 | 1.14–3.94 | 0.018 | 2.18 | 1.03–4.60 | 0.041 |

| 2 | 4.36 | 2.47–7.73 | < 0.001 | 4.64 | 2.34–9.22 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 14.18 | 8.41–23.90 | < 0.001 | 11.84 | 5.92–23.67 | < 0.001 |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 0.66 | 0.16–2.67 | 0.561 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.12 | 0.78–1.60 | 0.544 | |||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 2.66 | 1.52–4.66 | 0.001 | 1.14 | 0.61–2.15 | 0.679 |

| Pathological response, % | ||||||

| 0–10 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 11–75 | 0.93 | 0.62–1.39 | 0.725 | 1.34 | 0.87–2.06 | 0.188 |

| 76–100 | 0.38 | 0.21–0.67 | 0.001 | 1.49 | 0.67–3.33 | 0.332 |

Patterns and timing of recurrence

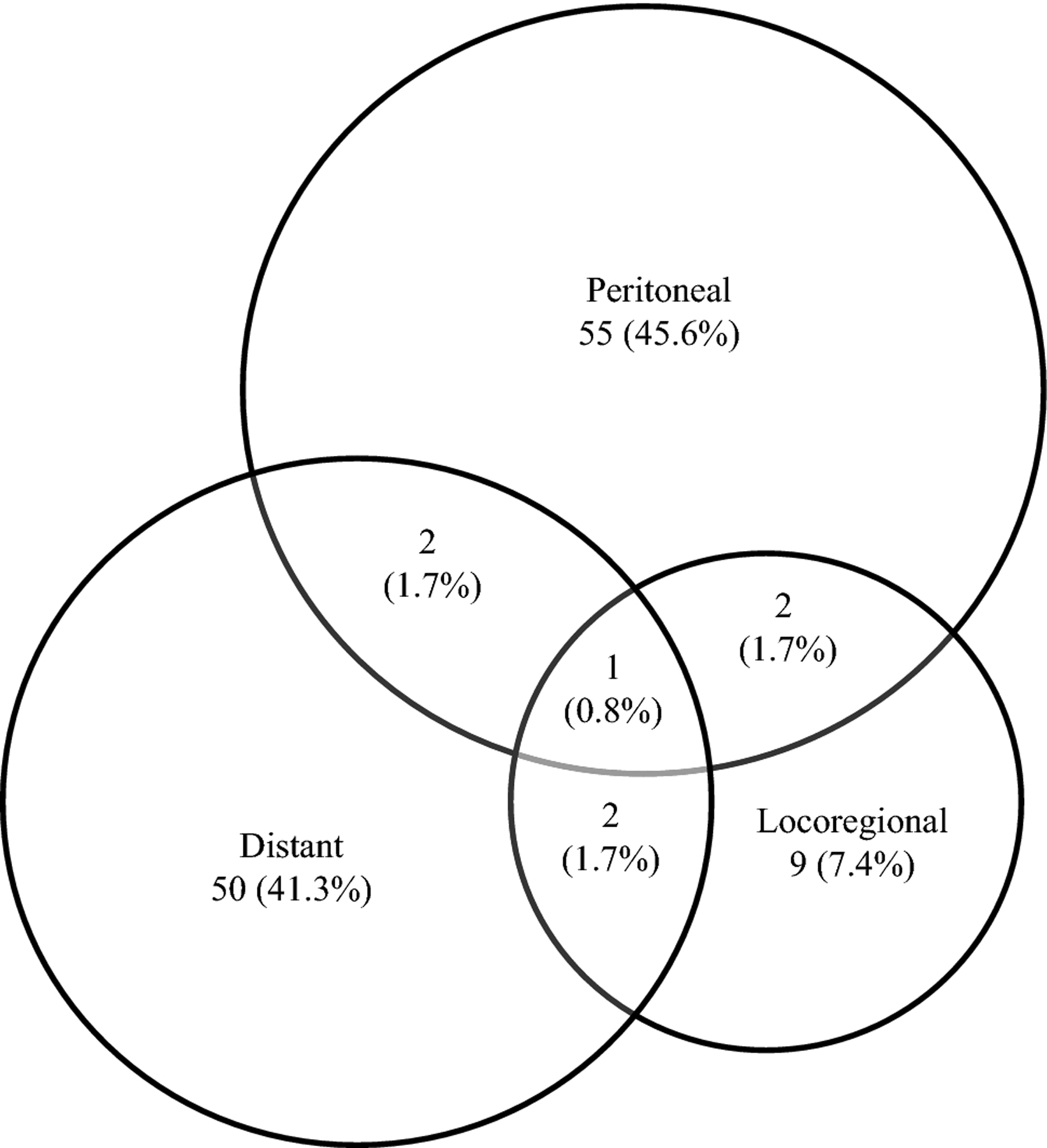

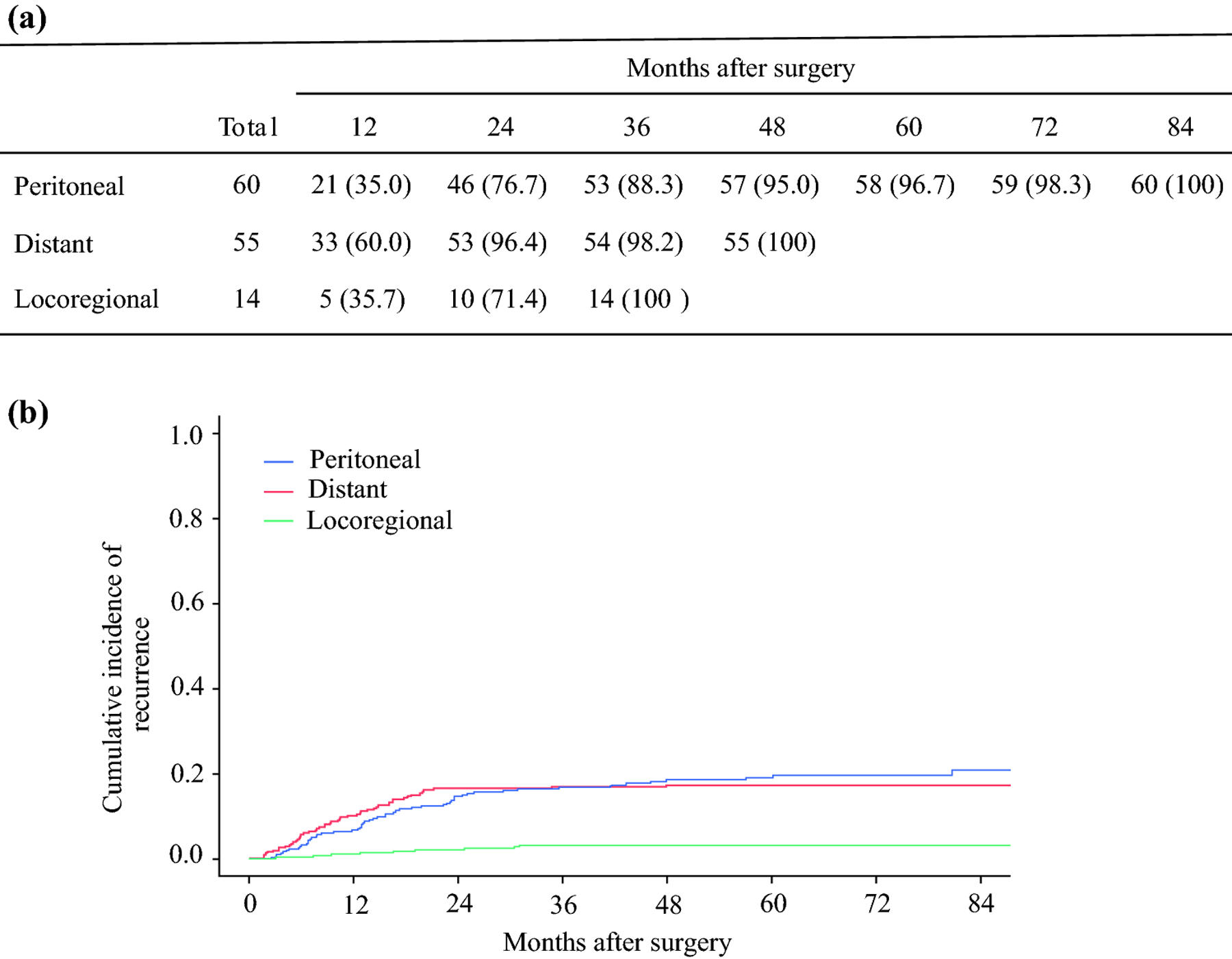

The first recurrence was detected in only one site in 114 (94.2%) patients, including 55 (45.4%) with peritoneal metastasis, 50 (41.3%) with distant metastasis, and 9 (7.4%) with locoregional recurrence. Seven (5.8%) patients had recurrences resulting from 2 or more sites at first detection (Figure 2). Including patients with multiple recurrence site categories, 60 (49.6%), 55 (45.5%), and 14 (11.6%) patients had peritoneal, distant, and locoregional recurrence, respectively (Figure 2). Fifty-six (46.3%), 102 (84.3%), 113 (93.4%), and 119 (98.3%) patients experienced recurrence within 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after surgery, respectively. Median time from surgical resection to recurrence was 14.5 (IQR 7.1–23.6), 9.3 (IQR 5.5–15.5), and 14.8 (IQR 7.4–24.8) months among patients with peritoneal, distant, and locoregional metastasis, respectively. Recurrence was more likely to occur early among those with distant metastasis, as 53 (96.4%) of these patients experienced recurrence within 2 years, compared with 46 (76.7%) patients with peritoneal metastasis (Figure 3a), although this difference was not significant (p = 0.14) (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Site of the first recurrence among the 121 patients who experienced recurrence.

Figure 3.

Cumulative recurrence by location of metastasis. (a) Recurrence rates. Data are given as n (%). (b) Cumulative incidence of recurrence.

Predictors of recurrence within 1 year

We investigated factors associated with early recurrence, defined as within 1 year after surgery, given that 46.3% of patients experienced recurrence within this period. Distant and peritoneal metastasis was found in 58.9% and 37.5% of 56 patients who recurred early, respectively. Multivariable analysis revealed that ypT4 was the only significant predictor for early recurrence (OR 2.58 [95% CI 1.10–6.08], p = 0.030). ypN positive status was not significant predictor for early recurrence (p = 0.494) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Uni- and multivariable analysis for early (< 1 year) recurrence. Categorical data are given as n (%).

| Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (56) | Late (65) | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Female sex | 20 (35.7) | 34 (52.3) | 0.067 | 0.53 | 0.24–1.19 | 0.122 |

| Year of surgery, 2011–2015 | 23 (41.1) | 32 (49.2) | 0.369 | |||

| Tumor location in the middle or lower third | 35 (62.5) | 48 (73.8) | 0.180 | |||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | 0.186 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 33 (58.9) | 30 (46.2) | 0.161 | |||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 9 (16.1) | 5 (7.7) | 0.151 | |||

| Distal gastrectomy | 22 (39.3) | 33 (50.8) | 0.206 | |||

| > 25 dissected nodes | 27 (48.2) | 24 (36.9) | 0.210 | |||

| ypT4 | 34 (60.7) | 24 (36.9) | 0.009 | 2.58 | 1.10–6.08 | 0.030 |

| ypN positive | 50 (89.3) | 50 (76.9) | 0.073 | 1.52 | 0.46–5.01 | 0.494 |

| Pathologic response ≤ 75% | 6 (10.9) | 10 (16.1) | 0.412 | |||

| Tumor Size > 4 cm | 33 (60.0) | 26 (41.3) | 0.042 | 1.85 | 0.77–4.48 | 0.170 |

| Intestinal Lauren type | 18 (32.1) | 21 (32.8) | 0.938 | |||

| Well or moderate differentiation | 14 (25.0) | 12 (19.0) | 0.433 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 43 (76.8) | 41 (64.1) | 0.129 | |||

| Peritoneal metastasis | 21 (37.5) | 39 (60.0) | 0.014 | 0.44 | 0.11–1.79 | 0.250 |

| Distant metastasis | 33 (58.9) | 22 (33.8) | 0.006 | 1.33 | 0.34–5.12 | 0.680 |

| Locoregional recurrence | 5 (8.9) | 9 (13.8) | 0.399 | |||

Survival from recurrence

Among the 121 patients with recurrence, median overall survival (OS) from recurrence was 8.8 (IQR 4.2–17.1) months. During follow-up, 110 (90.9%) patients died of gastric cancer. The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates after recurrence were 36.7% and 17.5%, respectively. There was no difference in OS following recurrence between patients with only peritoneal metastasis vs. those with only distant metastasis (p = 0.297). Median OS after recurrence was relatively longer in patients with recurrence after ≥ 1 year (10.7 (IQR 6.4–20.0) vs. 6.7 (IQR 2.4–12.4) months), although this difference was not significant (p = 0.145).

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first long-term analysis of patterns and predictors of recurrence specifically among patients with locally advanced clinical stage II/III gastric cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and curative-intent resection. Among patients treated at a tertiary referral cancer center, the majority of recurrences in this patient population occurred within 2 years. We also identified pathological T stage as useful risk predictor for early recurrence.

Our results demonstrate that ypT4 and ypN positive status, i.e. pathological poor response, were negative predictors for RFS and this finding is consistent with prior reports of predictors of survival in Western gastric cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy7,8,22. A retrospective single-institution study including 488 patients, of whom 292 received neoadjuvant chemo- or chemoradiotherapy, also identified ypT3/4 and ypN positive status as independently negative predictors for RFS, though the majority of patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy underwent chemoradiation 8. More recently, a multi-institutional retrospective study of 408 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the Netherlands similarly found that ypN positive status was the strongest predictor of worse RFS 7. In addition, the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) trial reported that only ypN status was an independent predictor for OS 22. Thus, our results are part of a strong body of evidence supporting ypN status as a robust predictor for survival for gastric cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The other significant predictor of RFS in our multivariable analysis was total or proximal gastrectomy, which was associated with worse RFS compared with distal gastrectomy. Tumor location, however, was not a significant predictor for RFS (HR 0.82, p = 0.316). This differs from several previous studies reporting worse survival after curative resection in proximal gastric cancer patients compared with those with distal gastric cancer 23,24, and a report of worse response to chemotherapy in patients with proximal vs. distal gastric cancer 25. Type of gastrectomy likely represents a surrogate for tumor location as a survival predictor among patients with locally advanced gastric cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In addition, total rather than distal gastrectomy may also be selected on the basis of larger tumor size or more aggressive pathology such as extensive linitis plastica.

The rates of peritoneal and distant metastasis we observed, approximately 50% and 46%, respectively, were within previously reported ranges, while that for locoregional recurrence, 12%, is the lowest yet observed 7,8,10,12,14,16,18,19,26. This difference is even more pronounced in comparison with the study of patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment, in which Mokadem et al. reported locoregional recurrence in 38% of patients 7. The lower rate of locoregional recurrence in our study likely results from the fact that all patients had R0 resections, whereas 30 of 150 patients in the Mokadem et al. study had a R1/2 resection 7.

The present study revealed that 84% of recurrences were found within 2 years after surgery, a greater proportion than in past studies 8,10,12,16,18,19. The reason for this difference might be that our study included only patients with clinically advanced disease. We also observed that distant metastases were more commonly observed early compared to peritoneal metastasis, which may reflect late diagnosis of occult metastatic disease in the peritoneum. Our findings support relatively longer follow-up to detect peritoneal metastasis. This is especially justified given the risk of rapid onset of severe clinical symptoms in this setting, which may exclude patients from experimental studies or even preclude them from receiving palliative therapy.

In patients with recurrence, ypT4 stage was the only independent predictor we identified for early (< 1 year) recurrence (OR 2.58 [95% CI 1.10–6.08], p = 0.030). This finding contrasts with previous studies, which reported pathological nodal status as a predictor for early recurrence 15,17,18, but these did not include patients with preoperative treatment. This study focusing on only patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed that distant metastasis predominated in early recurrence. We also found that progressively higher ypT status is associated with poorer outcomes, and particularly ypT4 patients are at higher risk of early recurrence.

Our results, in combination with those of other studies, have implications for follow-up after resection. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network practice guidelines for gastric cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy recommend a history and physical examination every 3–6 months for 1–2 years, every 6–12 months for 3–5 years, and then annually, accompanied by CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 6–12 months for 1–2 years and then annually up to 5 years and blood tests and endoscopy as clinically indicated 27. A more aggressive follow-up schedule such as that recommended by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, which includes blood tests, radiologic imaging, and endoscopy every 6 months for 1–3 years, then annually 28, may detect recurrences earlier. However, early diagnosis of recurrence failed to improve survival 29, and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical recommendations state that there is no evidence that regular intensive follow-up improves patient outcomes 30. Nonetheless, early detection of recurrence may improve quality of life by enabling earlier initiation of palliative treatment, and it may also identify more patients for appropriate clinical trials. The results of this study provide better understanding of recurrence patterns following neoadjuvant treatment that may be useful for providing more accurate prognostic information to patients.

There are several limitations to this study. Selection bias is inherent in any retrospective study design. Also, patients received a number of neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens because recommendations changed during the 15-year study period, which might have influenced the results. In addition, clinical follow-up varied by surgeon and patient to patient.

In conclusion, ypT4 stage, ypN positive status, and total or proximal gastrectomy were the strongest predictors of tumor recurrence for clinical stage II or III gastric cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Peritoneal and distant metastasis accounted for most recurrences. Most recurrences were identified within 2 years after surgery, earlier than reported by previous studies including gastric cancer patients who did not receive treatment. The most important predictor for early recurrence (< 1 year) was ypT stage. Longer follow-up is needed to find peritoneal metastasis compared with distant metastasis. This analysis may inform future guidelines for surveillance and help identify patients likely to experience recurrence sooner so that they may be considered for relevant clinical trials.

Synopsis.

In this retrospective single-center study, we sought to characterize outcomes among patients with locally advanced gastric cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is now standard treatment in the West. We found that most recurrences occurred within 2 years and ypT4 is the only independent predictor for recurrence within 1 year after surgery. Pathologic T stage appears to stratify risk for early recurrence.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. The authors acknowledge Jessica Moore, MS, staff editor at MSK, for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: YYJ has received research funding provided to the institution from Rgenix, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Genentech/Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Merck and served on advisory boards for Rgenix, Merck Serono, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Bayer, Imugene, Merck, Daiichi-Sankyo, and AstraZeneca. GYK has received honoraria and research funding from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pieris, and research funding from AstraZeneca, Zymeworks, and Daiichi Sankyo. DHI has received research funding from and served on advisory boards for Astellas, Eli Lilly, Pieris, and Taiho, and served on advisory boards for Astra-Zeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Roche. SBM has received research funding from Genentech and travel expenses from Merck and Bayer. All other authors declare that they have no financial relationships to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Ajani JA, Mansfield PF, Janjan N, et al. Multi-institutional trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with potentially resectable gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(14):2774–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Zhao L, Liu H, et al. A phase II study of a modified FOLFOX6 regimen as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2016;114(12):1326–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;393(10184):1948–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coccolini F, Nardi M, Montori G, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced gastric and esophago-gastric cancer. Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Surg 2018;51:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao ZF, Liu XY, Wang ZN, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2018;18(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokadem I, Dijksterhuis WPM, van Putten M, et al. Recurrence after preoperative chemotherapy and surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study. Gastric Cancer 2019;22(6):1263–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikoma N, Chen HC, Wang X, et al. Patterns of Initial Recurrence in Gastric Adenocarcinoma in the Era of Preoperative Therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24(9):2679–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seyfried F, von Rahden BH, Miras AD, et al. Incidence, time course and independent risk factors for metachronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin--a longitudinal experience from a prospectively collected database of 1108 patients. BMC Cancer 2015;15:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu CW, Lo SS, Shen KH, et al. Incidence and factors associated with recurrence patterns after intended curative surgery for gastric cancer. World J Surg 2003;27(2):153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spolverato G, Ejaz A, Kim Y, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence after curative intent resection for gastric cancer: a United States multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2014;219(4):664–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2004;240(5):808–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou HH, Kuo CJ, Hsu JT, et al. Clinicopathologic study of node-negative advanced gastric cancer and analysis of factors predicting its recurrence and prognosis. Am J Surg 2013;205(6):623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng J, Liang H, Wang D, Sun D, Pan Y, Liu Y. Investigation of the recurrence patterns of gastric cancer following a curative resection. Surg Today 2011;41(2):210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eom BW, Yoon H, Ryu KW, et al. Predictors of timing and patterns of recurrence after curative resection for gastric cancer. Dig Surg 2010;27(6):481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu D, Lu M, Li J, et al. The patterns and timing of recurrence after curative resection for gastric cancer in China. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14(1):305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakar B, Karagol H, Gumus M, et al. Timing of death from tumor recurrence after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2004;27(2):205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg 2000;87(2):236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Chang KK, Yoon C, Tang LH, Strong VE, Yoon SS. Lauren Histologic Type Is the Most Important Factor Associated With Pattern of Recurrence Following Resection of Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2018;267(1):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67(2):93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappell R Competing risk analyses: how are they different and why should you care? Clin Cancer Res 2012;18(8):2127–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth EC, Fassan M, Cunningham D, et al. Effect of Pathologic Tumor Response and Nodal Status on Survival in the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(23):2721–2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison LE, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Proximal gastric cancers resected via a transabdominal-only approach. Results and comparisons to distal adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Ann Surg 1997;225(6):678–683; discussion 683–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piso P, Werner U, Lang H, Mirena P, Klempnauer J. Proximal versus distal gastric carcinoma--what are the differences? Ann Surg Oncol 2000;7(7):520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higuchi K, Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Saigenji K, Ajani JA. Chemotherapy is more active against proximal than distal gastric carcinoma. Oncology 2004;66(4):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz RE, Zagala-Nevarez K. Recurrence patterns after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: prognostic factors and implications for postoperative adjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9(4):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajani JA, D’Amico TA. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Gastric Cancer v 2.2020 2020; https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf.

- 28.Japanese Gastric Cancer A Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer 2017;20(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aurello P, Petrucciani N, Antolino L, Giulitti D, D’Angelo F, Ramacciato G. Follow-up after curative resection for gastric cancer: Is it time to tailor it? World J Gastroenterol 2017;23(19):3379–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson C, Cunningham D, Oliveira J, Group EGW. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009;20 Suppl 4:34–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]