Abstract

Studies with live cells demonstrate that agonist and antagonist rapidly (within minutes) modulate the subnuclear dynamics of estrogen receptor α (ER) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1). A functional cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-tagged lac repressor-ER chimera (CFP-LacER) was used in live cells to discretely immobilize ER on stably integrated lac operator arrays to study recruitment of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-steroid receptor coactivators (YFP–SRC-1 and YFP-CREB binding protein [CBP]). In the absence of ligand, YFP–SRC-1 is found dispersed throughout the nucleoplasm, with a surprisingly high accumulation on the CFP-LacER arrays. Agonist addition results in the rapid (within minutes) recruitment of nucleoplasmic YFP–SRC-1, while antagonist additions diminish YFP–SRC-1–CFP-LacER associations. Less ligand-independent colocalization is observed with CFP-LacER and YFP-CBP, but agonist-induced recruitment occurs within minutes. The agonist-induced recruitment of coactivators requires helix 12 and critical residues in the ER–SRC-1 interaction surface, but not the F, AF-1, or DNA binding domains. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching indicates that YFP–SRC-1, YFP-CBP, and CFP-LacER complexes undergo rapid (within seconds) molecular exchange even in the presence of an agonist. Taken together, these data suggest a dynamic view of receptor-coregulator interactions that is now amenable to real-time study in living cells.

Estrogen receptor α (ER) is a member of the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily and regulates transcription of specific target genes in response to ligand binding and phosphorylation (2, 19, 36). Functional domains involved in ER transcription function have been mapped and include a centrally located DNA binding domain (DBD); in addition, two activation function domains (AFs) have also been identified, including an N-terminal domain, AF-1, and a C-terminal domain, AF-2, containing the ligand binding domain (LBD) (14, 15, 35).

ER functionally interacts with a large group of proteins referred to as steroid receptor coregulators, including both coactivators and corepressors (reviewed in reference 20). Coactivators such as steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) and CREB-binding protein (CBP/p300) interact with ER in an agonist-dependent manner to increase transcription function (5, 12, 13, 24), in part due to intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity (23, 30). SRC-1 and CBP act synergistically to enhance steroid receptor-based transcription (28), suggesting that they are in the same molecular complex with steroid receptors. In the presence of agonist only, SRC-1 redistributes to ER foci bound to insoluble nuclear structures (33). The molecular mechanisms underlying interactions between ER and coactivators involve structural rearrangements in the LBD that occur upon hormone binding (4, 27). These structural changes involve the repositioning of helix 12 (amino acids [aa] 538 to 546) of the ER LBD, allowing for coactivator interactions in the presence of agonist. In vitro experiments have shown that helix 12 and key amino acids found in the coactivator binding pocket are essential for transcriptional activity and coactivator interactions (7, 10, 18).

Many assays used to analyze interactions between steroid receptors and coregulators are performed in vitro or with yeast two-hybrid systems; both of which fail to recapitulate the elegant organization of the mammalian nucleus (22). Furthermore, experiments to characterize transactivator function often involve the use of transient transfection assays and exogenous templates that only partially reflect the complex organization of steroid receptors in the context of nuclear architecture (29). Recently, a functional green fluorescent protein-ER fusion protein (GFP-ER) was shown to undergo ligand-dependent intranuclear reorganization (11, 33). Furthermore, this reorganization correlates with nuclear matrix (NM) association (33), suggesting that the NM plays a role in the subnuclear organization of ER and agonist-dependent SRC-1 binding. In contrast to a report showing high mobility of several intranuclear proteins (25), our recent photobleaching and biochemical data demonstrate that ligand and, surprisingly, proteasome activity regulate the intranuclear mobility-NM association between ER and SRC-1 (34). This work supports the notion that a highly organized and dynamic subnuclear environment provides a framework for receptor function (1, 6, 31, 32).

Integrated DNA segments containing multiple binding sites for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (21) have been utilized to show that fluorescent transcription factors can undergo rapid exchange with their DNA binding sites in living cells. In a different system, amplified chromosomal regions containing large numbers of lac operator sites were used to analyze the effects of transcription factor binding on chromatin structure (3, 26). Chimeric proteins consisting of GFP-Lac repressor bound to VP16 activation function domain (37) or ER (A. C. Nye, R. R. Rajendran, D. L. Stenoien, M. A. Mancini, B. S. Katzenellenbogen, and A.S. Belmont, submitted for publication) result in an expansion of the chromosomal region containing the lac operators due to changes in chromatin structure.

To obtain additional insight into the mechanisms of intranuclear ER and coactivator dynamics, we have utilized the integrated lac operator arrays to localize fluorescent lac repressors linked to wild-type and mutant ERs. Real-time in vivo recruitment assays were performed to demonstrate that helix 12 and critical residues in the ER–SRC-1 interaction surface of AF-2 are required for rapid (within minutes), agonist-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)–SRC-1 recruitment. AF-1, DNA binding, and C-terminal F domains are expendable for agonist-induced recruitment. Additionally, recruitment of YFP-CBP to CFP-LacER is agonist dependent and rapid (within minutes) and requires the same molecular domains. Finally, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was used to analyze the dynamics of array-bound ER and SRC-1 or CBP in living cells. Intriguingly, although agonist stabilizes these interactions, ER–SRC-1 and ER-CBP complexes remain highly dynamic in terms of exchange half-life (within seconds).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and labeling.

A03_1 and RRE_B1 cells were cultured as described previously (16). Twenty-four hours prior to transfection, cells were plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips in 35-mm-diameter wells at a concentration of 105 cells/well in phenol red-free medium containing 10% charcoal-stripped serum. Transient expression of CFP-LacER and SRC-1 vectors in A03_1 and RRE_B1 cells was performed with FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics, Inc.) Twelve hours after transfection, cells were shocked with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and allowed to recover for 6 h in stripped medium prior to addition of hormone. Vehicle (ethanol), 10 nM 17β -estradiol (E2; Sigma), 10 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT; a gift from D. Salin-Drouin, Laboratoires Besins Iscovesco, Paris, France), or 10 nM ICI 182,780 (a gift from Alan Wakeling, Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Macclesfield, United Kingdom) was added for the times indicated.

Vectors.

CFP-ER and YFP–SRC-1 constructs were made as described previously (33). ER deletion constructs were generated by PCR to place a stop codon followed by a BamHI site at the appropriate amino acid to be used in subcloning. PCR products were ligated into the original CFP-ER vector, and the resulting vectors were sequenced to verify that no mutations were present. The V376D mutant was generated by site-directed mutagenesis to recapitulate the previously described mutant (18). The CFP-LacER vectors were made from GFP-LacER (Nye et al., submitted for publication) by a swap involving placement of the lac repressor (BamHI site) and a portion of the ER (SacII site) into the CFP-ER vectors. YFP-SRC780-LXXAA was made from a vector in which all of the LXXLL amino acids were mutated to LXXAA (a kind gift from M. G. Parker) by swapping the HindIII-BamHI fragment containing the three LXXLL repeats located between aa 570 and 780.

Fluorescent and deconvolution microscopy.

Deconvolution microscopy was performed with a Zeiss AxioVert S100 TV microscope and a DeltaVision Restoration Microscopy System (Applied Precision, Inc.). A Z-series of focal planes were digitally imaged and deconvolved with the DeltaVision constrained iterative algorithm to generate high-resolution images. All image files were digitally processed for presentation with Adobe Photoshop and printed at 300 dpi with a Codonics NP 1600 dye diffusion printer.

Live microscopy.

Following transfection, cells were transferred to a live-cell, closed chamber (Bioptechs, Inc., Butler, Pa.) and maintained in medium with 10% stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C. This medium was recirculated with a peristaltic pump to which ligand was added following the zero-time-point exposure. In order to minimize photo damage, cells were imaged with neutral-density filters to allow only 30% of the total light and 1-s exposure times. FRAP was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. A single Z section was imaged before and at different time intervals following the 2-s bleach. The bleach was performed with the laser set at 458 nm and at maximum power for 50 iterations of a box representing a portion of each array. For dual-FRAP experiments, both CFP-LacER and YFP-SRC780 or YFP-CBP were bleached with the same laser setting and simultaneous images corresponding to the CFP and YFP fluorescence were obtained by using the multitracking function of the microscope. Fluorescent intensities of regions of interest were obtained with LSM software, and data analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel. LSM images were exported as TIF files, and final figures were generated with Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

RESULTS

CFP-LacER chimeras bind to lac operator repeats.

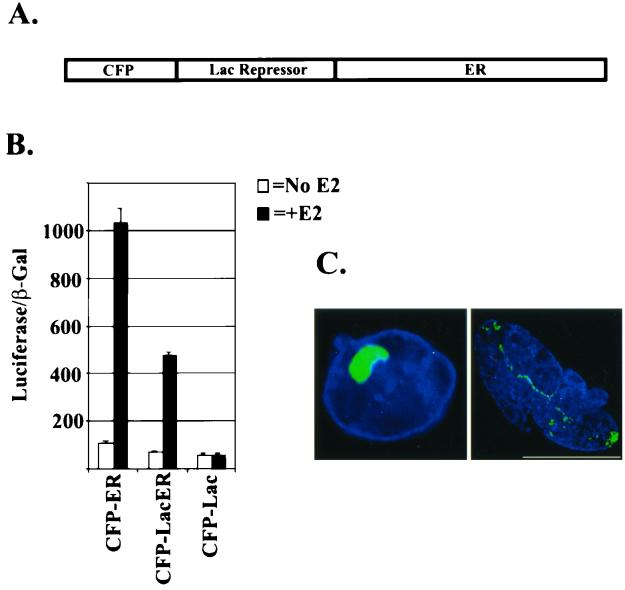

Stable cell lines containing integrated arrays comprised of multiple copies of the lac operator have been used to analyze the effects of transcription factors on chromatin structure (3, 37). Recently, a chimera containing GFP-LacER was shown to bind with high affinity to these arrays and to influence chromatin structure (Nye et al., submitted). Here, we used this system to evaluate real-time protein-protein interactions in the nuclei of living cells. Toward this end, we generated CFP-Lac repressor fusions with full-length ER (CFP-LacER) (Fig. 1A). CFP-LacER retains the ability to activate transcription in an agonist-dependent manner, although it is less active (∼50%) than untagged ER (Fig. 1B). We next transfected this plasmid into two stable cell lines containing integrated lac operator arrays. The A03_1 cell line (16) contains heterochromatic arrays arranged in a globular structure useful for studying changes in chromatin, while the RRE_B1 cell line contains euchromatic arrays, which are more extended and linear (J. Zhao and A. S. Belmont, unpublished data). When either of these cell lines is transfected with CFP-LacER, most of the fluorescent protein is associated with the compact A03_1 arrays or more linear RRE_B1 arrays (Fig. 1C). Other CFP-lac fusions with ER mutations also target to the array (see below), since binding occurs via the lac repressor domain.

FIG. 1.

CFP-LacER binds to lac operators. (A) Schematic diagram of the CFP-LacER chimera shows the N-terminal CFP followed by the lac repressor with ER at its C terminus. (B) The activity of the CFP-LacER was tested on an estrogen response element-containing promoter driving luciferase expression in the presence and absence of 10 nM E2. Clear agonist-induced activity (∼50% of wild type) with CFP-LacER, but not CFP-Lac alone, is evident. Shown is the luciferase activity divided by β-galactosidase activity, which served as an internal control (n = 3). (C) A03_1 (left) or RRE_B1 (right) cells were transfected with CFP-LacER. After fixation, nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue), and then deconvolution-based fluorescence microscopy was performed. CFP-LacER binds to globular arrays in A03_1 cells and extended arrays in RRE_B1 cells. Bar = 10 μm.

Targeting of SRC-1 to LacER on lac operators.

We have previously reported a clear agonist-dependent interaction between bulk wild-type ER and SRC-1 in distinct intranuclear foci (33). However, analysis of interactions between ER deletion constructs and SRC-1 is complicated in cases in which both proteins have diffuse intranuclear distributions. To overcome this problem, we utilized the integrated lac operators to localize lac repressor-ER fusion proteins, thus allowing us to evaluate protein-protein interactions in living cells. ER–SRC-1 interactions were first analyzed in A03_1 cells cotransfected with CFP-LacER and YFP–SRC-1. When YFP–SRC-1 is transfected alone, it has a similar intranuclear distribution, as observed previously in HeLa cells, with no detectable accumulation on the arrays in the presence or absence of added hormone (data not shown). In cells cotransfected with CFP-LacER and YFP–SRC-1, addition of agonist results in the rapid recruitment to the array of the nucleoplasmic YFP–SRC-1 within 5 min (Fig. 2A). In some cases, most of the YFP–SRC-1 pool was recruited to the array in as little as 2 min after hormone addition, indicating that SRC-1 recruitment is a rapid process. In most cells, an accumulation of YFP–SRC-1 can be observed in the absence of hormone, which may be due to the very high concentration of CFP-LacER in these globular arrays and weak hormone-independent interactions between ER and SRC-1 (17; B. M. Jaber and C. L. Smith, personal communication). When RRE_B1 cells containing the more extended, euchromatic arrays (and therefore less concentrated CFP-LacER) are analyzed, fewer hormone-independent interactions between CFP-LacER and YFP–SRC-1 are visible, which is likely due in part to the lower signal at the arrays versus the significant levels of YFP–SRC-1 throughout the nucleus (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

CFP-LacER recruits YFP–SRC-1. (A) A03_1 cells were cotransfected with CFP-LacER (top row) and YFP–SRC-1 (bottom row) and subjected to live microscopy during hormone addition. Before hormone addition (left column), CFP-LacER is found associated with the array, but much of the YFP–SRC-1 remains nucleoplasmic. Addition of E2 (10 nM, 5 min) results in the rapid recruitment of YFP–SRC-1 to CFP-LacER (bottom). (B) When the same experiment is performed with RRE_B1 cells, much less YFP–SRC-1 (bottom left) is evident on an extended, euchromatic array containing CFP-LacER (top left) in the absence of hormone. Addition of E2 (10 nM, 5 min) results in the rapid recruitment of YFP–SRC-1 (bottom right) to the CFP-LacER (top right). Images are deconvolved and represent a single Z-section. Bar = 10 μm.

We have previously shown that a small segment of SRC-1 spanning aa 570 to 780 (YFP-SRC570–780) containing three LXXLL motifs required for NR binding (8) is sufficient for colocalization with bulk nucleoplasmic ER (33). E2 addition results in YFP-SRC570–780 recruitment to CFP-LacER on the A03_1 arrays as well (data not shown). A disadvantage of using YFP-SRC570–780 is that it is distributed throughout the cell, since it lacks the amino-terminal nuclear localization signal of SRC-1 and must rely upon diffusion through nuclear pores to enter the nucleus. A longer construct spanning the amino-terminal region of SRC-1 (YFP-SRC780) is localized in the nucleus and is recruited to the arrays (Fig. 3A and B), similar to full-length YFP–SRC-1. This construct is much easier to express than full-length SRC-1, which has a tendency to form large cytoplasmic aggregates once a very low threshold of expression is reached. For this reason, the following experiments were performed with YFP-SRC780.

FIG. 3.

YFP-SRC780 recruitment to CFP-LacER in A03_1 cells. (A) In the absence of hormone, YFP-SRC780 (right column) is present in the nucleoplasm and also accumulates on the CFP-lacER (left column) bound to the lac operator arrays. (B) Following E2 addition (10 nM, 30 min), most of the YFP-SRC780 is found associated with CFP-LacER. (C) Pretreatment with 4HT (10 nM, 30 min) leads to less YFP-SRC780 on the array. (D) Pretreatment with ICI 182,780 (10 nM, 30 min) also diminishes the amount of YFP-SRC780 on the array. (E) Mutation of the LXXLL motifs to LXXAA results in no SRC-1 accumulation on the array even in the presence of agonist. Bar = 10 μm.

The observed accumulation of YFP–SRC-1 on the lac operator arrays in A03_1 cells suggests that ER–SRC-1 interactions occur in the absence of hormone. To test whether antagonists prevent YFP–SRC-1 binding to CFP-LacER, cells were pretreated with vehicle (Fig. 3A), 10 nM E2 (Fig. 3B), 10 nM 4HT (Fig. 3C), or 10 nM ICI 182,780 (Fig. 3D) for 30 min prior to microscopic analysis. Treatment with either 4HT or ICI 182,780 resulted in a uniform distribution of YFP–SRC-1 throughout the nucleoplasm, with much less pronounced accumulations on the array compared to no ligand and E2. Recruitment of SRC-1 is dependent upon the LXXLL motifs, because mutation of the three LXXLL motifs present in YFP-SRC780 to LXXAA results in no colocalization following E2 addition (Fig. 3E).

To determine if this experimental paradigm could be applied to other types of coactivator molecules, functional YFP-CBP and CFP-LacER were cotransfected in A03_1 cells. In the absence of hormone, we observe negligible accumulation of YFP-CBP on the array (Fig. 4A) in most cells, in contrast to the substantial amount of YFP–SRC-1 found on the array in the absence of hormone. Addition of 10 nM E2 results in the recruitment of YFP-CBP to CFP-LacER (Fig. 4B); however, this recruitment is qualitatively less complete than that observed for YFP–SRC-1. YFP-CBP recruitment also occurs within minutes of adding E2. In the presence of 10 nM 4HT (Fig. 4C) or 10 nM ICI 182,780 (Fig. 4D), YFP-CBP does not accumulate on the array.

FIG. 4.

YFP-CBP recruitment to CFP-LacER in A03 1 cells. (A) In the absence of hormone, YFP-CBP (right column) is present in the nucleoplasm with little accumulation on the CFP-LacER (right column) bound to the lac operator arrays. (B) Following E2 addition (10 nM, 30 min), most of the YFP-CBP is found associated with CFP-LacER. (C) Pretreatment with 4HT (10 nM, 30 min) leads to no YFP-CBP on the array. (D) Pretreatment with ICI 182,780 (10 nM, 30 min) also prevents YFP-CBP from going to the array. Bar = 10 μm.

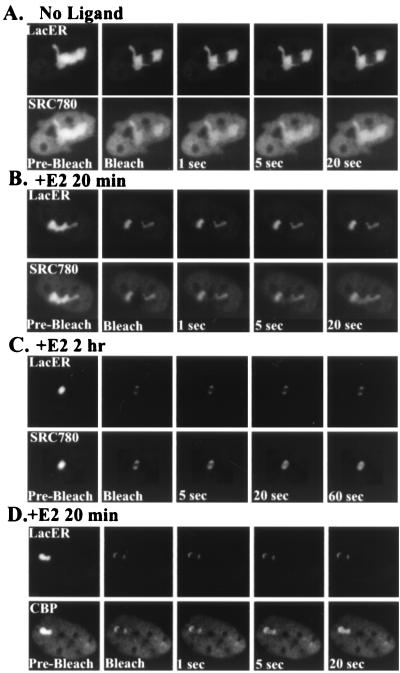

FRAP was next used to analyze the stability of ER–SRC-1 interactions in A03_1 cells. Following a short bleaching with a high-intensity laser, little recovery of CFP-LacER fluorescence is observed for 30 s (Fig. 5A and B; lower panels) or for over 20 min (data not shown), indicating that this chimeric receptor is essentially immobilized on the array due to its high-affinity binding (26). In contrast, the YFP-SRC780 present on the array in the absence of hormone (Fig. 5A) recovers very rapidly, reaching its steady-state distribution within seconds, with a recovery half-life (t1/2) of 2.1 ± 0.8 s (n = 10 cells). Following treatment with E2 for 20 min or less, photobleaching results in a clearly defined YFP-SRC780 bleach zone that shows complete recovery within a t1/2 of 8.0 ± 2.5 s (n = 10). Treatment with E2 for longer periods of time (>1 h) (Fig. 5C) results in slower recovery of the YFP–SRC-1 (t1/2 = 30.2 ± 15.1 s), suggesting that ER–SRC-1 complexes may become more stable over time. There is much more heterogeneity in these cells, with half-lives ranging between ∼15 and 45 s, which accounts for the large deviation. We next tested the stability of the CFP-LacER–YFP-CBP complexes by using this FRAP procedure. Following treatment with 10 nM E2, YFP-CBP recovered rapidly, with a t1/2 of 4.2 ± 1.1 s (Fig. 5D). In the case of YFP-CBP, no stabilization of the complex was observed following longer hormone treatments (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Dual FRAP of CFP-LacER and coregulators. Simultaneous FRAP was performed on A03_1 cotransfected with both CFP-LacER and YFP-SRC780 or YFP-CBP to analyze the molecular dynamics of ER-coregulator complexes. In the absence of ligand, bleaching of CFP-LacER (A, top row) results in a dark zone that exhibits little recovery during 20 s or for up to 20 min (data not shown). In contrast, YFP-SRC780 reequilibrates to its steady-state distribution within seconds (A, bottom row; t1/2 = 2.1 ± 0.8 s, n = 10 cells). With brief exposure to agonist (20 min, [B, bottom row]), SRC780 becomes more stably bound to the CFP-LacER; however, complete recovery is observed within 20 to 40 s (t1/2 = 7.5 ± 1.2 s, n = 10 cells). With longer agonist exposure (2 h [C, bottom row]), YFP-SRC780 recovers more slowly (t1/2 = 30.2 ± 15.1 [bottom row]), indicating that ER-SRC complexes stabilize over time. FRAP was also performed on cells cotransfected with CFP-LacER and YFP-CBP (D). Following treatment with E2, YFP-CBP recovers within 20 s with a t1/2 of 4.2 ± 1.1 (n = 10). Stabilization of ER-CBP complexes was not observed with longer E2 treatments (data not shown).

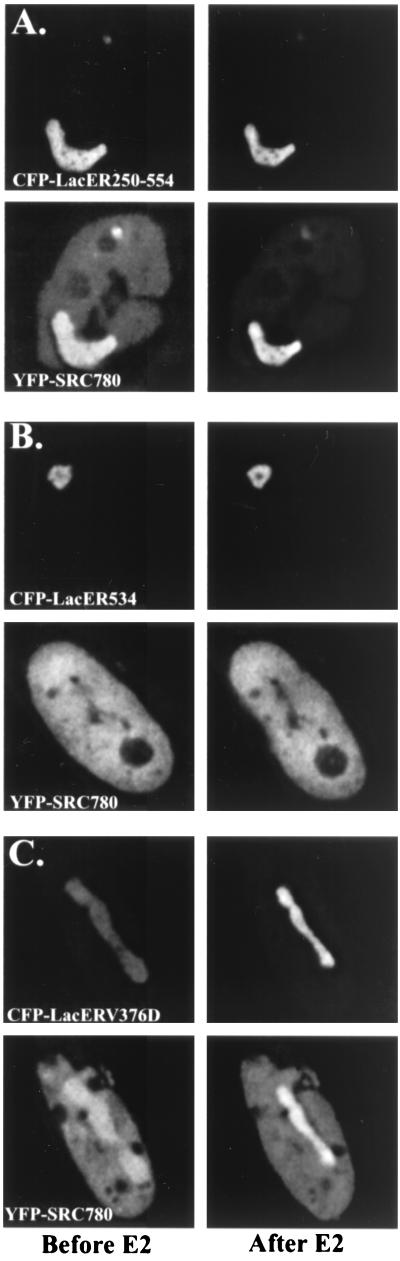

To test ER domains responsible for SRC-1 interactions in vivo, CFP-LacER deletion and mutation constructs were generated. When CFP-LacER554 (lacking the F domain; data not shown) or CFP-LacER250–554 (lacking F, AF-1, and the DBD) (Fig. 6A) was cotransfected with YFP-SRC780, agonist addition resulted in the rapid recruitment of the coactivator to the array as observed for full-length CFP-LacER (Fig. 2). We next tested the effects of deletion of helix 12 on YFP-SRC780 recruitment. Shown in Fig. 6B are A03_1 cells cotransfected with CFP-LacER534 and YFP-SRC780. In these cells, no recruitment of YFP–SRC780 is observed in the presence of hormone, suggesting that helix 12 is required. Also, negligible ligand-independent accumulation of YFP-SRC780 is observed. Finally, we tested an inactive point mutant, CFP-LacERV376D, for coactivator interactions in vivo. This mutation results in an inactive ER that does not show appreciable binding to SRC-1 in glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down experiments (18). Interestingly, this mutation does not appear to affect ligand-independent interactions, but prevents the recruitment of the nucleoplasmic YFP-SRC780 following agonist addition (Fig. 6C). The array itself becomes noticeably brighter, primarily due to the condensation and concentration of the agonist-recruited fluorescent molecules, with little or no loss of the nucleoplasmic YFP-SRC780 fluorescence.

FIG. 6.

Critical regions required for YFP–SRC-1 recruitment. A03_1 cells were cotransfected with YFP-SRC780 (bottom row) and either CFP-LacER250–554 (A, top row), CFP-LacER534 (B, top row), or CFP-LacERV376D (C, top row). Cells were imaged before (left column) and after 20 min of 10 nM E2 (right column). CFP-LacER250–554 retains all of the critical residues required for agonist-induced YFP-SRC780 recruitment (A). Deletion of helix 12 (CFP-LacER534 [B]) prevents ligand-enhanced recruitment and eliminates most of the ligand-independent interactions. Mutation of the ER–SRC-1 interface (CFP-LacERV376D [C]) inhibits agonist-induced SRC-1 recruitment, but does not eliminate the ligand-independent interactions. The brighter signal is primarily due to contraction of the chromosomal region (Nye et al., submitted).

ER domains necessary for YFP-CBP recruitment were next tested in the A03_1 cells. As with full-length CFP-LacER (Fig. 2B), an F domain deletion, CFP-LacER554, rapidly recruits YFP-CBP to the arrays (data not shown). Moreover, deletion of the AF-1, DBD, and F domains (e.g., CFP-LacER250–554) results in a protein that retains the ability to recruit YFP-CBP (Fig. 7A). Again, we see no recruitment following deletion of helix 12 (CFP-LacER534; Fig. 7B). Finally, the CFP-LacERV376D point mutant was analyzed and showed little agonist-dependent recruitment of YFP-CBP to the arrays (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that the LBD is sufficient for agonist-induced recruitment of YFP-CBP as well and that helix 12 and residues comprising the ER–SRC-1 interaction interface are required for recruitment of both YFP-SRC and YFP-CBP.

FIG. 7.

Critical regions required for YFP-CBP recruitment. A03_1 cells were cotransfected with YFP-CBP (bottom rows) and either CFP-LacER250–554 (A, top row), CFP-LacER534 (B, top row), or CFP-LacERV376D (C, top row). Cells were imaged before (left column) and after 20 min of 10 nM E2 (right column). CFP-LacER250–554 retains all of the critical residues for agonist-induced YFP-CBP recruitment (A). Deletion of helix 12 (CFP-LacER534 [B]) prevents ligand-enhanced recruitment of YFP-CBP. Mutation of the ER–SRC-1 interface (CFP-LacERV376D [C]) inhibits agonist-dependent CBP recruitment.

DISCUSSION

Targeting of ER to discrete subnuclear regions via interactions between the lac repressor and large chromatin domains containing lac operons allowed us to analyze interactions between ER and coactivators in a live-cell setting. YFP–SRC-1, but not YFP-CBP, accumulates with CFP-LacER even in the absence of hormone. FRAP studies demonstrate that these ligand-independent interactions between YFP–SRC-1 and CFP-LacER are transient. Addition of agonist results in the rapid recruitment of both YFP–SRC-1 and YFP-CBP (within minutes) and stabilization of the receptor-coactivator complexes as measured by FRAP. Interestingly, these complexes are highly dynamic, with exchange of subunits occurring within seconds. Domain-mapping experiments reveal that a region (aa 535 to 554) that contains helix 12 (aa 538 to 546) in the crystal structure of the ER LBD (4, 27) is required for SRC-1 and CBP recruitment, while N-terminal regions that include AF-1 and DBDs are dispensable.

Ligand binding is known to induce conformational changes that reveal interaction surfaces required for the SRC-1 binding presented here. Structural studies provide insight into the importance of helix 12 for coactivator interactions. The E2-bound ER LBD exists in a different conformation from the raloxifene-bound LBD due to a repositioning of helix 12 (4). In the E2-bound LBD complex, helix 12 forms a surface that is important for AF-2 activity. In contrast, helix 12 in the raloxifene-bound LBD is buried in a hydrophobic groove that limits access to critical residues required for AF-2 function. Recently, the structure of the ER LBD bound to agonist and an NR box peptide (containing the LXXLL motif) from the SRC-1-related GRIP1 protein was determined. Interestingly, the coactivator NR box lies in the groove formed by the agonist-induced repositioning of helix 12 (27). The structure of the ER LBD bound to tamoxifen was also determined and showed that helix 12 was in a position to occlude coactivator binding by mimicking interactions formed by the NR box with the LBD. These studies provide a structural mechanism for the differential effects of agonists and antagonists observed here and point out that rearrangements involving helix 12 are very important for ER activity and interactions with coactivators. Point mutagenesis of conserved residues in this region of the mouse ER and GR significantly reduces ligand-dependent transcriptional activation without affecting either ligand or DNA binding (7). Also, deletion experiments demonstrate that helix 12 is critical for ER's intranuclear reorganization, also pointing to the importance of this region for ER function (D. L. Stenoien and M. A. Mancini, unpublished data).

Our live-cell data, particularly with the A03_1 cell line, indicate that SRC-1 can interact with the ligand-free receptor. Several other pieces of data support our observations. First, coactivation assays show that SRC-1 increases basal activity levels of ER in the absence of hormone (34). Furthermore, recent fluorescence energy transfer (FRET) data obtained with fluorescently tagged ER LBD and SRC-1 peptides indicate that some ligand-independent interactions do occur (17). Ligand-independent interactions in a mammalian two-hybrid assay show basal interactions between ER and SRC-1 in HeLa cells (Jaber and Smith, personal communication). Taken together with our photobleaching studies, which indicate rapid (t1/2 = 2 s) complex exchange, these interactions are likely to be more transient than those induced by an agonist that result in most of the SRC-1 being bound to the receptor. While agonist reduces the exchange rate, the E2-induced ER–SRC-1 complexes remain highly dynamic (t1/2 ∼8 s) immediately following hormone treatment. There appears to be a stabilization of the ER–SRC-1 complexes over time, because the recovery half-life increases to approximately 30 s after 1 h of hormone exposure. Collectively, these data address an increasingly appreciated component of nuclear receptor function, i.e., dynamics (21).

The lac operator system used here has unique advantages in that it allows ER-coactivator interactions to be analyzed in a living mammalian nucleus as opposed to more conventional assays, such as in vitro binding or yeast two-hybrid experiments. There are several problems inherent in each of these systems. In vitro experiments are often performed with bacterially expressed proteins, which may lack proper posttranslational modifications and proper folding. Furthermore, these experiments do not take into account that steroid receptors are components of larger complexes containing either heat shock proteins or coregulator molecules, depending on the ligand-bound state of the receptor. Many of the same problems also exist in yeast two-hybrid assays, which may lack necessary mammalian components. The use of our lac operator binding system provides a complementary way to analyze protein-protein interactions in vivo. Furthermore, live-cell FRAP analysis of these interactions in real time provides new insight into complex formation and the surprisingly high degree of molecular exchange.

The differences in the exchange rates between SRC-1 and CBP suggest that SRC-1 is more tightly bound to ER than CBP. These results confirm those of a FRET-based assay that showed SRC-1 has a higher affinity for ER (38). Interestingly, in this previous study, no increase in FRET was observed between ER and CBP following ligand addition. Our live recruiting assays clearly show agonist-dependent colocalization of ER and CBP. A possible explanation for the discrepancy between the two results is that the molecular distance between the fluorescent probes on CBP and ER is greater than the minimal distance required for FRET (20 to 100 Å) (9). This could occur if the orientation of the fluorescent molecules prevented energy transfer or if the association between ER and CBP is via a third protein that is part of this complex.

Taken together, these studies approach multiple attributes of ER function within a nuclear context. These direct, live studies provide a novel system for studying the dynamic behavior of ER and coregulators. The ability to monitor two proteins simultaneously provides an unambiguous assessment of the early events that occur after hormone addition. Coactivator recruitment is rapid, occurring within minutes of hormone addition. Helix 12 and the agonist-induced conformational changes that expose regions necessary for intranuclear ER function are critical for coactivator interactions, yet the AF-1 and DBD are dispensable in our system. Surprisingly, once formed, the steroid receptor-coactivator complexes remain highly dynamic. These results suggest not only do transcription complexes undergo rapid exchange with DNA target sites in vivo (21), but the individual components of these complexes also undergo rapid exchange. Exciting avenues for future investigation will be to apply these tools to analyze interactions between other receptors and coregulators and to test novel, clinically relevant compounds for their effects on these interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Cooney, D. Moore, Z. D. Sharp, and J. Wong for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to M. A. Mancini (R01-DK55622), A. Belmont (R01-GM58460 and R01-GM42516), and C. L. Smith (RO1 DK53002); a National American Heart Association Scientist Development Award and funds from the Department of Cell Biology, Baylor College of Medicine to M. A. Mancini; an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (1F32DK09787) to D. L. Stenoien; and an NIH Cell and Molecular Biology traineeship (T32-GM07283) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute predoctoral fellowship to A. Nye.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrack E R. Steroid hormone receptor localization in the nuclear matrix: interaction with acceptor sites. J Steroid Biochem. 1987;27:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(87)90302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beato M, Chavez S, Truss M. Transcriptional regulation by steroid hormones. Steroids. 1996;61:240–251. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(96)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belmont A S, Li G, Sudlow G, Robinett C. Visualization of large-scale chromatin structure and dynamics using the lac operator/lac repressor reporter. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;58:203–222. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61957-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brzozowski A M, Pike A C, Dauter Z, Hubbard R E, Bon T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene G L, Gustafsson J A, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakravarti D, LaMorte V J, Nelson M C, Nakajima T, Schulman I G, Juguilon H, Montminy M, Evans RM. Role of CBP/P300 in nuclear receptor signaling. Nature. 1996;383:99–103. doi: 10.1038/383099a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook P R. The organization of replication and transcription. Science. 1999;284:1790–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danielian P S, White R, Lees J A, Parker M G. Identification of a conserved region required for hormone dependent transcriptional activation by steroid hormone receptors. EMBO J. 1992;11:1025–1033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heery D M, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker M G. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–736. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heim R, Tsien R Y. Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr Biol. 1996;6:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henttu P M A, Kalkhoven E, Parker M G. AF-2 activity and recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator 1 to the estrogen receptor depend on a lysine residue conserved in nuclear receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1832–1839. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Htun H, Holth L T, Walker D, Davie J R, Hager G L. Direct visualization of the human estrogen receptor alpha reveals a role for ligand in the nuclear distribution of the receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:471–486. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenster G, Spencer T E, Burcin M M, Tsai S Y, Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. Steroid receptor induction of gene transcription: a two-step model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7879–7884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin S C, Heyman R A, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar V, Green S, Stack G, Berry M, Jin J R, Chambon P. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell. 1987;51:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees J A, Fawell S E, Parker M G. Identification of two transactivation domains in the mouse oestrogen receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5477–5488. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li G, Sudlow G, Belmont A S. Interphase cell cycle dynamics of a late-replicating, heterochromatic homogeneously staining region: precise choreography of condensation/decondensation and nuclear positioning. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:975–989. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llopis J, Westin S, Ricote M, Wang J, Cho C Y, Kurokawa R, Mullen T M, Rose D W, Rosenfeld M G, Tsien R Y, Glass C K. Ligand-dependent interactions of coactivators steroid receptor coactivator-1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding protein with nuclear hormone receptors can be imaged in live cells and are required for transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4363–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mak H Y, Hoare S, Henttu P M, Parker M G. Molecular determinants of the estrogen receptor-coactivator interface. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangelsdorf D J, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenna N J, Lanz R B, O'Malley B W. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNally J G, Muller W G, Walker D, Wolford R, Hager G L. The glucocorticoid receptor: rapid exchange with regulatory sites in living cells. Science. 2000;287:1262–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nickerson J A, Blencowe B J, Penman S. The architectural organization of nuclear metabolism. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;162A:67–123. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogryzko V V, Schiltz R L, Russanova V, Howard B H, Nakatani Y. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87:953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onate S A, Tsai S Y, Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phair R D, Mistelli T. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature. 2000;404:604–609. doi: 10.1038/35007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinett C C, Straight A, Li G, Willhelm C, Sudlow G, Murray A, Belmont A S. In vivo localization of DNA sequences and visualization of large-scale chromatin organization using lac operator/repressor recognition. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1685–1700. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiau A K, Barstad D, Loria P M, Cheng L, Kushner P J, Agard D A, Greene G L. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith C L, Onate S A, Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. CREB binding protein acts synergistically with steroid receptor coactivator-1 to enhance steroid receptor-dependent transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8884–8888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith C L, Hager G L. Transcriptional regulation of mammalian genes in vivo. A tale of two templates. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27493–27496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spencer T E, Jenster G, Burcin M M, Allis C D, Zhou J, Mizzen C A, McKenna N J, Onate S A, Tsai S Y, Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature. 1997;389:194–198. doi: 10.1038/38304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein G S, van Wijnen A J, Stein J L, Lian J B, Pockwinse S, McNeil S. Interrelationships of nuclear structure and transcriptional control: functional consequences of being in the right place at the right time. J Cell Biochem. 1998;70:200–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenoien D, Sharp Z D, Smith C L, Mancini M A. Functional subnuclear partitioning of transcription factors. J Cell Biochem. 1998;70:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stenoien D L, Mancini M G, Patel K, Allegretto E, Smith C L, Mancini M A. Subnuclear trafficking of estrogen receptor-α and steroid receptor coactivator-1. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:518–534. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.4.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenoien D L, Patel K, Mancini M G, Dutertre M, Smith C L, O'Malley B W, Mancini M A. FRAP reveals estrogen receptor-α mobility is ligand- and proteasome-dependent. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:15–23. doi: 10.1038/35050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tora L, White J, Brou C, Tasset D, Webster N, Scheer E, Chambon P. The human estrogen receptor has two independent nonacidic transcriptional activation functions. Cell. 1989;59:477–487. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai M J, O'Malley B W. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tumbar T, Sudlow G, Belmont A S. Large-scale chromatin unfolding and remodeling induced by VP16 acidic activation domain. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1341–1354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou G, Cummings R, Li Y, Mitra S, Wilkinson H A, Elbrecht A, Hermes J D, Schaeffer J M, Smith R G, Moller D E. Nuclear receptors have distinct affinities for coactivators: characterization by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1594–1604. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.10.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]