Abstract

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for 6 months is a global public health goal, but measuring its achievement as a marker of population breastmilk feeding practices is insufficient. Additional measures are needed to understand variation in non‐EBF practices and inform intervention priorities. We collected infant feeding data prospectively at seven time points to 6 months post‐partum from a cohort of vulnerable women (n = 151) registered at two Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program sites in Toronto, Canada. Four categories of breastmilk feeding intensity were defined. Descriptive analyses included the (i) proportion of participants in each feeding category by time point, (ii) use of formula and non‐formula supplements to breastmilk, (iii) proportion of participants practising EBF continuously for at least 3 months; and (iv) frequency of transitions between feeding categories. All participants initiated breastmilk feeding with 70% continuing for 6 months. Only 18% practised EBF for 6 months, but 48% did so for at least 3 continuous months. The proportion in the EBF category was highest from 2 to 4 months post‐partum. Supplemental formula use was highest in the first 3 months; early introduction of solids and non‐formula fluids further compromised EBF at 5 and 6 months post‐partum. Most participants (75%) transitioned between categories of breastmilk feeding intensity, with 35% making two or more transitions. Our data show high levels of breastmilk provision despite a low rate of EBF for 6 months. Inclusion of similar analyses in future prospective studies is recommended to provide more nuanced reporting of breastmilk feeding practices and guide intervention designs.

Keywords: breastfeeding, breastmilk, exclusive breastfeeding, infant and child nutrition, infant feeding, infant formula, post‐partum

Key Messages.

Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months post‐partum is a global public health goal, but more nuanced indicators are needed to assess population level breastmilk feeding practices and guide targeted preventive interventions.

In our cohort of vulnerable women, classification of prospective infant feeding data by breastmilk feeding intensity revealed high levels of breastmilk feeding despite only 18% exclusively breastfeeding for 6 months.

Transitions occur both ways between exclusive and non‐exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding was highest from 2 to 4 months post‐partum. Among breastfeeding participants, formula supplementation was highest in the first 3 months and then stabilized, whereas introduction of solids further compromised exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months post‐partum.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastmilk provides infants with a unique package of nutrients, immunological factors and other bioactive components tailored to support human health and development within local ecosystems (Bode et al., 2020; Victora et al., 2016). Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is therefore recommended for the first 6 months of life for all infants (WHO & UNICEF, 2003), but challenges persist in the achievement of this goal. Barriers to EBF operate at individual, family, community and societal levels, ranging from difficulties with breastfeeding technique to mothers' need to return to work and widespread promotion of breastmilk substitutes (Balogun et al., 2015; Rollins et al., 2016). Globally, cross‐sectional surveys show that only 44% of infants age 1–5 months receive EBF based on 24‐h recall data (UNICEF, 2020) and a much smaller proportion would receive EBF continuously for 6 months (Greiner, 2014). National Canadian data show that although 90% of women initiate breastfeeding, only 32% breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months (PHAC, 2019). Figures such as these highlight the need for renewed efforts to promote and support EBF, but do not adequately communicate the extent of breastmilk intake by all infants or the nature of feeding practices that interfere with EBF. These feeding practices are likely to vary widely, leading to a lack of evidence regarding the magnitude and nature of the gaps between recommended and actual breastfeeding practices in specific settings (Chetwynd et al., 2019; Thulier, 2010). The strong emphasis on EBF for 6 months may also discourage women who are unable to achieve this, rather than encouraging as much breastmilk feeding as possible (Brown, 2016).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines EBF as providing only breastmilk and essential vitamins, minerals and medicines (WHO, 2008). This leads to exclusion from the EBF designation the first time any other fluids or foods are provided, no matter how minimal the amount or infrequent the occurrence. Many studies report the duration of EBF on the assumption that it is a continuous behaviour from birth until a time point at which other substances are introduced and then continually provided. In reality, women often move between EBF and other degrees of breastmilk feeding in the first 6 months post‐partum, sometimes making more than one transition in either direction (Bodnarchuk et al., 2006; Chetwynd et al., 2019). However, when reporting against the WHO definition, these variations are levelled out to a single designation of non‐EBF. There is a need to analyse and report breastmilk feeding practices in a more nuanced way, including assessment at various time points as well as continuously from birth, and incorporating measures of breastmilk feeding intensity (Chetwynd et al., 2019).

Breastmilk feeding intensity refers to the proportion of daily feeds which are breastmilk. Intensity may range from 0% to 100% and is therefore typically divided into categories for analysis. Boundaries of these categories vary between studies, and some include only milk feeds in the assessment of intensity, whereas others include solids and/or non‐milk fluids as well (Bonuck et al., 2005, 2014; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2014; Stuebe et al., 2016; Whipps et al., 2019). Overall, this approach has not been widely used in breastfeeding research, perhaps because many studies are retrospective, but it warrants greater utilization prospectively as a means to enhance understanding of breastmilk feeding practices over time. This is particularly important for population groups known to have lower breastfeeding rates, in order to inform the design of tailored interventions targeting priority non‐EBF practices in a context‐specific manner. More nuanced assessment would also allow for increased precision in investigations of the relationships between early life feeding practices and later health outcomes, informing intervention priorities (Thulier, 2010).

In this paper, we report breastmilk feeding practices at seven time points over the first 6 months post‐partum in a cohort of vulnerable women recruited from two Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP) sites in Toronto, Canada. We defined four categories of breastmilk feeding intensity using criteria encompassing both milk and non‐milk feeds. Our objectives were to assess the (i) proportion of participants in each category of breastmilk feeding intensity at each time point, (ii) use of formula and non‐formula supplements to breastmilk, (iii) proportion of participants practising EBF continuously for at least 3 months within the first 6 months post‐partum and (iv) frequency of transitions between categories of breastmilk feeding intensity.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study setting and participants

This study utilized infant feeding data collected in a pre/post‐intervention study designed to examine the effectiveness of delivering postnatal lactation support through the CPNP. The CPNP is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and implemented through community agencies across the country with the aim of improving birth outcomes and breastfeeding among socially and/or economically vulnerable families, such as those who are experiencing poverty, isolation or substance use (PHAC, 2020). Core services include nutrition and health education, provision of food and/or grocery vouchers, individual supports and referrals to other community services.

The study methods have been reported in detail elsewhere (Mildon et al., 2021). Briefly, we recruited pregnant women who registered in the CPNP at two sites in Toronto, Canada, and who intended to try breastfeeding and to continue living in Toronto with their infant. Both CPNP sites primarily serve low‐income women and newcomers to Canada and operate as weekly drop‐in programmes providing both group education workshops and individual services. Clients of the two sites who gave birth during the intervention phase of our study had access to in‐home visits by International Board Certified Lactation Consultants, and those meeting specific criteria also received double electric breast pumps.

Recruitment, intervention delivery and the community CPNP programs were all suspended in March 2020 due to the COVID‐19 pandemic; however, data collection continued virtually as planned. At the point of suspension, recruitment of the post‐intervention group was incomplete, and only 14 participants had full exposure to the intervention. Thus, infant feeding data from all participants were pooled for the current analyses.

2.2. Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Office of Research Ethics of the University of Toronto and the Research Ethics Board of Toronto Public Health. All participants provided written informed consent to participate.

2.3. Data collection

All data collection was conducted by the first author or a Mandarin‐speaking research assistant, and occurred in person at the two participating CPNP sites or by telephone. Professional interpreter services were used for participants who did not speak English or Mandarin (n = 24).

Maternal socio‐demographic characteristics were collected prenatally via interview‐administered questionnaires. Household food insecurity during the first 6 months post‐partum was assessed using the Canadian Community Health Survey Household Food Security Survey Module and classified as marginal, moderate, severe or none (food secure) based on the number of affirmative responses (Health Canada, 2020). Household income adequacy and receipt of federal Employment Insurance maternity benefits (yes/no) were assessed at 6 months post‐partum using validated questions from Statistics Canada's Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (Statistics Canada, 2018).

Breastmilk feeding intentions were assessed prenatally using the validated Infant Feeding Intentions scale (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey, 2009). Post‐discharge infant feeding data were collected prospectively at 2 weeks post‐partum and monthly to 6 months using a standardized and validated questionnaire used previously with CPNP clients (Francis et al., 2021; O'Connor et al., 2008). At each time point, participants reported the average daily number of breastmilk and formula feeds provided to their infant, including formula provision as a top‐up after feeding at the breast. Provision of non‐milk fluids and the date of introduction of solids, if applicable, were also recorded. Participants who stopped breastfeeding were asked to recall the last date they provided any breastmilk to their infant and the main reasons for cessation.

2.4. Breastmilk feeding categories

We adapted the FeedCat Tool developed and validated by Noel‐Weiss et al. (2014) to classify breastmilk feeding intensity into four categories (Exclusive, Predominant, Partial and None) for each participant at each data collection time point (Noel‐Weiss et al., 2014) (Table 1). We used the term ‘breastmilk’ feeding as we did not differentiate between modes of feeding (i.e. at the breast or expressed breastmilk) for this analysis. We defined ranges of breastmilk provision for each category as a proportion of total milk feeds (Exclusive: 100%; Predominant: ≥75%; Partial: <75%; None) with additional criteria related to the provision of non‐milk fluids and solid foods. Occasional (less than daily frequency) feeds of water or herbal teas were allowed within the EBF category, but no other foods or fluids. It is recommended to introduce solids ‘around 6 months’ based on developmental readiness (Health Canada, 2015; WHO & UNICEF, 2003), so we defined early introduction as starting solids at least 14 days prior to 6 months. At the 6‐month time point, the EBF category therefore included participants who had introduced solids within 14 days but otherwise provided only breastmilk.

Table 1.

Breastmilk feeding intensity categories

| Category | Definition | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive | 100% milk feeds as breastmilk with no additional fluids or foods except vitamins/minerals, medicines and minimal water‐based liquids |

• 100% milk feeds as breastmilk AND • no formula top‐ups, juice or cow's milk AND • no regular water/herbal tea (< one time per day) AND • no solids prior to 1–5 months or >14 days prior to 6 months |

| Predominant | ≥75% milk feeds as breastmilk |

• ≥75% milk feeds as breastmilk; may include formula top‐ups and any other fluids/foods OR • 100% milk feeds as breastmilk + formula top‐ups; may include any other non‐formula fluids/foods OR • 100% milk feeds as breastmilk + solids (if introduced prior to 1–5 months or >14 days prior to 6 months) |

| Partial | <75% milk feeds as breastmilk |

• <75% milk feeds as breastmilk; may include formula top‐ups and any other fluids/foods OR • no breastmilk feeds < 7 days |

| None | No breastmilk feeds | • no breastmilk feeds ≥7 days |

2.5. Supplements to breastmilk

In order to assess the use of supplements to breastmilk, participants providing breastmilk but not in the EBF category (i.e. classified as Predominant or Partial) at each time point were divided into three hierarchical groups based on provision of (i) formula, with or without solids or other fluids; (ii) solids, with or without non‐formula fluids; and (iii) non‐formula fluids only.

Continuous breastmilk feeding without formula use was determined by the proportion of participants reporting 100% of milk feeds as breastmilk at 2 weeks post‐partum and subsequent time points, until the first time point at which breastmilk feeding intensity dropped below 100% or could not be assessed.

2.6. Continuous exclusive breastmilk feeding

The duration of EBF was first assessed as the proportion of participants in the EBF category at 2 weeks post‐partum who continued in this category at each subsequent time point. Participants were excluded from the continuous EBF group at the first time point at which their breastmilk feeding category changed from EBF or could not be classified due to missing data. We also assessed the prevalence of EBF with a duration of 3 months or more (i.e. at least half the recommended EBF duration) starting from post‐partum Month 1, 2 or 3 after an initial period of formula supplementation or missing data.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all indicators. Infant feeding intentions scores were grouped into ranges shown in previous research to correspond with breastmilk feeding practices (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey, 2009). Frequencies were used to determine the proportion of participants in each of our four breastmilk feeding categories and three breastmilk supplement groups at each time point. The frequency of transitions between breastmilk feeding categories (0, 1, ≥2) during the 6‐month post‐partum period was also assessed.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study participants

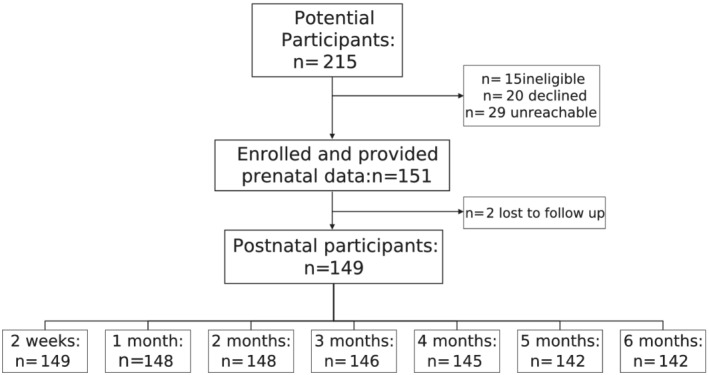

Recruitment was conducted from November 2018 until March 2020. During this period, 215 clients with due dates within the study timeframe registered at the two CPNP sites and consented to be contacted about the study (Figure 1). Of these, 15 were ineligible due to pregnancy loss, preterm birth (<34 weeks' gestation) or moving out of Toronto; 20 declined to participate, and 29 were unreachable, resulting in a total of 151 enrolled participants. All participants provided prenatal socio‐demographic data, but two were lost to follow‐up prior to providing any post‐partum data. A further seven were lost to follow‐up during the post‐partum period, and 142 completed the study. Complete breastfeeding category data were available for three participants who were lost to follow‐up as they had already reported breastfeeding cessation.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram

All study participants were at least 20 years old, and the mean age was 31 years (Table 2). Half (51%) were primiparous, and 70% had post‐secondary education. Only 10% were born in Canada, and nearly half (48%) had lived in Canada for less than 3 years. The three primary countries of origin were China (29%), Brazil (17%) and Mexico (11%), with smaller numbers from 23 other countries around the world (data not shown). Nearly one‐third of participants (31%) reported household food insecurity, 44% reported that their household income was adequate to meet all regular expenses, and only 29% received Employment Insurance maternity benefits during the first 6 months post‐partum (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics (n = 151)

| Category | Indicator | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Parity | Primiparous | 77 (51.0) |

| Multiparous | 74 (49.0) | |

| Age | Mean age (SD) | 31.3 years (4.4) |

| 20–25 years | 11 (7.3) | |

| 26–34 years | 108 (71.5) | |

| ≥35 years | 32 (21.2) | |

| Education | Below high school | 3 (2.0) |

| High school | 43 (28.5) | |

| Post‐secondary | 105 (69.5) | |

| Newcomer status | <1 year in Canada | 30 (19.9) |

| 1–<3 years in Canada | 43 (28.5) | |

| ≥3 years in Canada | 63 (41.7) | |

| Born in Canada | 15 (9.9) | |

| Household food insecurity (n = 140) | None (secure) | 97 (69.3) |

| Marginal | 7 (5.0) | |

| Moderate | 20 (14.3) | |

| Severe | 16 (11.4) | |

| Proportion of regular expenses met by household income a (n = 140) | All | 62 (44.3) |

| Most | 38 (27.1) | |

| Some | 25 (17.9) | |

| Very little | 10 (7.1) | |

| None | 1 (0.7) | |

| Do not know/prefer not to answer | 4 (2.9) | |

| Maternity benefits b (n = 140) | Received | 40 (28.6) |

| Did not receive | 99 (70.7) | |

| Do not know/prefer not to answer | 1 (0.7) |

Categorical variable from Statistics Canada Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (Statistics Canada, 2018) used to assess household income adequacy to meet regular expenses during the first 6 months post‐partum.

Categorical variable used to assess receipt of maternity benefits through the federal Employment Insurance program, which has eligibility criteria based on prior employment.

Prenatal commitment to exclusive breastmilk feeding was very high in our sample. Three‐quarters of participants (77%) scored 12 or higher on the Infant Feeding Intentions scale, indicating strong or very strong desire to provide breastmilk without use of formula or other milks during the first 6 months (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey, 2009).

3.2. Breastmilk feeding practices

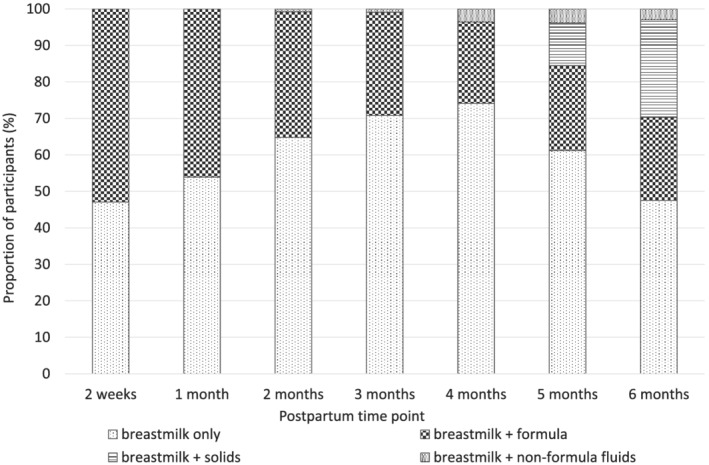

All study participants initiated breastmilk feeding, and 70% continued throughout the 6‐month follow‐up period (Table S1). Among those who discontinued breastmilk feeding, the median infant age at cessation was 66 days (interquartile range: 28, 128), and the main reasons given were insufficient milk supply (59%) and breastfeeding difficulties (25%), primarily infant dissatisfaction or refusal (data not shown). Despite the increased number of participants ceasing breastfeeding and transitioning to exclusive formula feeding over the study period, the use of any formula in the sample overall was highest at 2 weeks post‐partum (54%), declined to 40% at 4 months and increased again to 46% at 6 months (Table S1). Among participants providing any breastmilk, formula use declined to a low of 22% at 4 months post‐partum and remained around this level to 6 months (Figure 2). Solids were introduced within the study period by 75% of participants, with 39% introducing solids before 6 months post‐partum but none prior to 4 months.

Figure 2.

Feeding practices of participants providing any breastmilk at seven post‐partum time points.Note: Breastmilk + formula may include non‐formula fluids and/or solids; breastmilk + solids may include non‐formula fluids. Sample sizes: 2 weeks n = 136; 1 month n = 130; 2 months n = 125; 3 months n = 113; 4 months n = 112; 5 months n = 103; 6 months n = 10

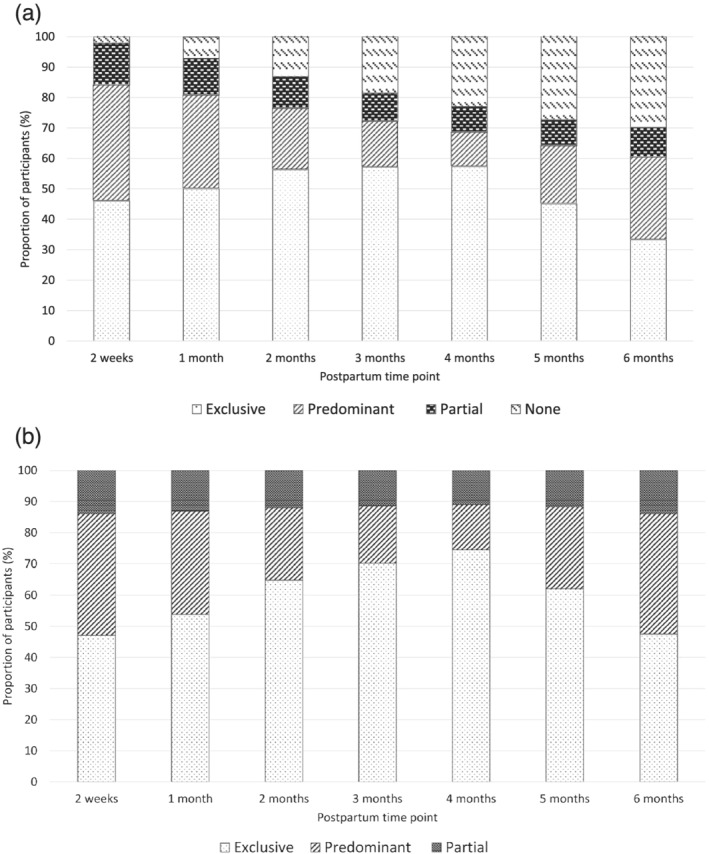

The distribution of participants across the four categories of breastmilk feeding intensity is shown in Figure 3 for both the total sample and those who were providing any breastmilk at each post‐partum time point. The proportion in the EBF category was highest from post‐partum Months 2 to 4 in the total sample (56%–57%), and declined to 33% at 6 months (Figure 3a). At least 60% of participants were in either the EBF or Predominant categories at all time points, with 84% classified in one of these two categories at 2 weeks post‐partum. Among participants providing any breastmilk, the proportion in the EBF category was equivalent at 2 weeks and 6 months post‐partum (47%) but rose to a high of 75% at 4 months (Figure 3b). At least 86% were in either the EBF or Predominant categories at all time points.

Figure 3.

Breastmilk feeding intensity classification. (a) Total sample. Sample sizes: 2 weeks n = 139; 1 month n = 140; 2 months n = 144; 3 months n = 140; 4 months n = 143; 5 months n = 142; 6 months n = 144. (b) Participants providing any breastmilk. Sample sizes: 2 weeks n = 136; 1 month n = 130; 2 months n = 125; 3 months n = 114; 4 months n = 110; 5 months n = 102; 6 months n = 101. Note: Categories defined by proportion of milk feeds as breastmilk (Exclusive: 100%; Predominant > 75%; Partial < 75%; None) with additional criteria related to solids and non‐formula fluids

Complete data were available to assess transitions between categories of breastmilk feeding intensity for 126 participants. Of 32 (25%) who remained in the same category throughout the 6‐month follow‐up period, 26 practised continuous EBF, and three stopped breastfeeding before the first data collection point. A further 51 participants (40%) experienced only one transition, including 13 (10%) who started in the Predominant group and transitioned to EBF by 2 months post‐partum, and 16 who were EBF to 4 or 5 months then transitioned to the Predominant group. The remaining 35% of participants reported two or more transitions between categories, with wide variation in direction and timing (data not shown).

Only 18% of the total sample practised continuous EBF from 2 weeks to 6 months post‐partum, but 29% never provided formula (Figure S1). Among participants providing any breastmilk, the proportion also providing formula dropped from 53% at 2 weeks to 22% at 4 months and remained at this level to 6 months post‐partum (Figure 2). However, EBF was further compromised from four to 6 months by the introduction of solids and other liquids.

Continuous EBF from 2 weeks to at least 3 months was practised by 33% of participants and an additional 21 (14%) practised EBF for a duration of at least 3 months but starting after 2 weeks post‐partum (Table S2). Inclusion of these participants increased the proportion practising EBF for at least 3 months from 33% to 48%.

4. DISCUSSION

In this prospective study, we assessed breastmilk feeding practices at seven time points over the first 6 months post‐partum in a cohort of vulnerable women in Toronto, Canada. We found high levels of breastmilk feeding at all time points despite only 18% practising continuous EBF for 6 months. The proportion in the EBF category at discrete time points was greatest from 2 to 4 months post‐partum, and at least 60% of the total sample was in either the EBF or Predominant category at all time points. These findings demonstrate the need for nuanced assessment of breastmilk feeding practices in order to assess progress towards the global EBF goal and to design targeted interventions to improve EBF in specific contexts.

Transitions between categories of breastmilk feeding intensity were common in our cohort; these varied widely in timing and direction, reflecting the dynamic nature of infant feeding practices. Other prospective studies have reported transitions to and from EBF, challenging the common assumption that movement from EBF to non‐EBF is one‐directional and permanent (Bodnarchuk et al., 2006; Dennis et al., 2019). In our study, inclusion of those who transitioned to EBF after 2 weeks post‐partum increased the proportion practising EBF continuously for at least 3 months from 33% to 48%.

Our findings have implications for both the measurement of EBF and the design of interventions to support EBF. Many studies focus on the indicator of EBF for 6 months, in support of the global recommendation, but this single indicator does not accurately reflect the extent of breastmilk feeding and needs to be complemented with additional measures to provide a more nuanced picture (Chetwynd et al., 2019). This has been illustrated by previous prospective studies, including the Infant Feeding Practices Study II in the United States. In this study, EBF rates declined consistently over time in the sample overall, but breastfeeding cessation rates were also high, with only 50% of participants providing any breastmilk at 6 months post‐partum (Grummer‐Strawn et al., 2008). Among those who continued breastfeeding, around 60% practised EBF from post‐partum Months 1 to 3, but only 8% were EBF at 6 months (Shealy et al., 2008). However, formula use by these participants declined in the first 3 months post‐partum and then remained around 35% to 6 months post‐partum; early introduction of solids was the major contributor to non‐EBF among infants receiving any breastmilk after 4 months post‐partum (Shealy et al., 2008). Our findings similarly show a need to take breastfeeding cessation rates into account when assessing EBF practices and to differentiate between formula and non‐formula supplements to breastmilk. All supplements displace breastmilk and are therefore not recommended during the first 6 months post‐partum, but relative harms vary depending on the nature, timing and context of supplement use. Introduction of solids before 4 months is associated with early cessation of breastfeeding (Lessa et al., 2020). Between 4 and 6 months post‐partum, introduction of solids does not confer health benefits, but in hygienic settings where nutrient‐rich complementary foods are available it has not been associated with health risks beyond displacement of breastmilk (Azad et al., 2018; Fewtrell et al., 2017). In contrast, formula use at any stage of infancy is a concern due to its association with early breastfeeding cessation, rapid infant weight gain and alterations to the infant gut microbiome, all of which have implications for lifelong health (Azad et al., 2018; Flaherman et al., 2019; Perrine et al., 2012; Stuebe, 2009; Thulier, 2010).

Analysis of non‐EBF practices is also needed to guide intervention planning in support of the goal of universal EBF. Our data suggest that breastfeeding interventions at the two CPNP sites should focus on reducing formula supplementation from birth and supporting clients to continue breastfeeding. These goals align with the strong breastmilk feeding intention expressed by study participants and could be addressed through a combination of strengthened prenatal preparation for breastfeeding and access to skilled lactation support beginning at birth and continuing in the community post‐hospital discharge (Brown, 2016; Feldman‐Winter, 2013; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2019). We did not examine associations between infant feeding intentions and classification of breastmilk feeding intensity, but we observed that among those who stopped breastfeeding, two‐thirds had reported strong prenatal intentions to provide only breastmilk for the first 6 months. Most participants (59%) who stopped breastfeeding reported low milk supply as the primary reason, which is consistent with other studies in Canada and around the world (Balogun et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2014; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2019; PHAC, 2019). Concerns about milk supply are also the likely reason for the high rates of early formula supplementation among participants who did continue breastmilk feeding, although this was not assessed. Self‐reported insufficient milk supply often reflects inadequate understanding of the normal process of establishing lactation, low breastfeeding self‐efficacy and limited access to skilled lactation support in the early post‐partum period (Dennis, 1999; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2019). Formula supplementation in the early post‐partum period is a common strategy employed by new parents anxious about milk supply but is strongly associated with decreased breastmilk supply and early breastmilk feeding cessation (Kent et al., 2020; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2019). However, a recent study found that this risk is attenuated with provision of formula volumes below 4 fl. oz per day, which may explain why many of our participants successfully transitioned to EBF after an initial period of formula supplementation (Flaherman et al., 2019).

Our study was originally designed to test a lactation support intervention, and these data suggest that increased access to skilled lactation support could assist women to achieve their breastmilk feeding goals. Based on our findings, support is needed from birth to mitigate early formula supplementation, build maternal self‐efficacy and support the establishment of lactation. Follow‐up between 3 and 4 months post‐partum may also assist in supporting continued and exclusive breastmilk feeding. We identified 4 months post‐partum as a transition point following which participants who were previously practising EBF began to provide solids and non‐formula liquids in addition to breastmilk. Research at another CPNP site in Toronto that implements a lactation support programme offering in‐home post‐partum visits by International Board Certified Lactation Consultants found very high rates of continued breastfeeding at 6 months post‐partum (84%) as well as high uptake of the lactation services, with 75% of study participants (n = 199) having received at least one lactation support visit (Francis et al., 2021). There is a need for further testing of delivery models for integrating post‐partum lactation support with the CPNP and other community perinatal services targeting vulnerable women.

In terms of limitations, all infant feeding data in this study were provided by maternal report, which is subject to recall and social desirability biases. Recall bias was minimized by the use of prospective data collection at multiple time points in the first 6 months post‐partum, which increases the accuracy of EBF reporting (Li et al., 2005). Short time intervals of data collection are also needed to capture transitions in breastmilk feeding intensity (Bodnarchuk et al., 2006). We reduced social desirability bias by emphasizing our interest in understanding all infant feeding practices, and the high rate of reporting formula use suggests participants were comfortable disclosing non‐breastmilk feeding practices. Our results may not be generalizable beyond the specific CPNP sites studied, but we have proposed methods that could be applied in other prospective infant feeding studies. However, we did not collect data on quantities of formula, water‐based liquids or solid foods provided. Breastmilk feeding intensity was defined first by the proportion of milk feeds as breastmilk, consistent with previous studies (Li et al., 2008; Whipps et al., 2019), but relative quantities of formula may not have been evenly distributed between the categories, particularly when individual feedings included both breastmilk and formula top‐ups. The use of formula top‐ups following breastmilk feeding has not been widely reported in the literature, but was commonly reported by study participants. Future studies should consider collecting data on this practice and on formula volumes in order to allow more precise categorization of breastmilk feeding intensity.

In adapting the FeedCat Tool for this analysis, we focused on the intensity of breastmilk feeding from any source and did not differentiate between feeding at the breast and expressed breastmilk. This sub‐classification is suggested for future research in order to examine patterns of exclusivity and other outcomes in relation to the intensity of expressed breastmilk use. Future studies may also consider subdividing the Partial breastmilk feeding category to include a ‘Minimal’ category, depending on the distribution of breastmilk feeding intensity levels in the dataset. In our cohort, very few participants were classified as Partial, so further subdivision of this category was not conducted.

In addition to the use of a prospective design with frequent and detailed data collection, strengths of this study include the high recruitment and retention rates. Research with vulnerable populations often suffers from high attrition rates, and strategies to maximize contact and trust building between research staff and participants have been recommended to address this (Barnett et al., 2012). We applied this guidance in our study through its integration within two CPNP sites. These community programmes provide multiple services and supports with strong staff investment in interpersonal connections with participants, creating a framework of trust that was transferred to this embedded research. Key research personnel attended both programmes weekly to facilitate rapport building, recruitment and data collection, and CPNP staff were often able to help with contacting participants who were difficult to reach. We also utilized professional interpreters to facilitate the inclusion of non‐English‐speaking participants.

5. CONCLUSION

In our cohort of vulnerable women with strong breastmilk feeding intention, continuous EBF for 6 months was low, but other measures revealed high rates of breastmilk provision. This study highlights the need for greater understanding and more nuanced reporting of non‐EBF practices. We recommend assessment of (i) breastmilk feeding intensity, (ii) intervals of continuous EBF within the first 6 months post‐partum and (iii) use of formula versus non‐formula supplements to breastmilk. These measures will provide insights regarding the extent and nature of exclusive and non‐exclusive breastmilk feeding, serve as markers of intermediate progress towards the goal of universal EBF and help inform intervention priorities.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

AM, JF, DLO and DWS designed the study with input from EDR and CLD. SS, BU, YN and CR facilitated the integration of research activities into the community programs. Data collection and primary analysis were conducted by AM with support from JF, DLO and DWS. AM drafted the manuscript for critical review by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Infant feeding practices

Table S2. Exclusive breastfeeding for three months or longer

Figure S1. Continuous exclusive breastmilk feeding and formula avoidance

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all study participants, and Yiqin Mao and Stephanie Zhang for their assistance with recruitment and data collection. This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Doctoral Research Award (GSD‐157928) to AM and by The Sprott Foundation and the Joannah and Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition. The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, interpretation or drafting of the manuscript.

Mildon, A. , Francis, J. , Stewart, S. , Underhill, B. , Ng, Y. M. , Rousseau, C. , Di Ruggiero, E. , Dennis, C.‐L. , O'Connor, D. L. , & Sellen, D. W. (2021). High levels of breastmilk feeding despite a low rate of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months in a cohort of vulnerable women in Toronto, Canada. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18:e13260. 10.1111/mcn.13260

Deborah L. O'Connor, PhD, and Daniel W. Sellen, PhD, are co‐senior authors.

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT03589963.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available in order to protect participant anonymity and confidentiality.

REFERENCES

- Azad, M. B. , Vehling, L. , Chan, D. , Klopp, A. , Nickel, N. C. , McGavock, J. M. , Becker, A. B. , Mandhane, P. J. , Turvey, S. E. , Moraes, T. J. , Taylor, M. S. , Lefebvre, D. L. , Sears, M. R. , & Subbarao, P. (2018). Infant feeding and weight gain: separating breast milk from breastfeeding and formula from food. Pediatrics, 142, e20181092. 10.1542/peds.2018-1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, O. O. , Dagvadorj, A. , Anigo, K. M. , Ota, E. , & Sasaki, S. (2015). Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: A quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11, 433–451. 10.1111/mcn.12180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J. , Aguilar, S. , Brittner, M. , & Bonuck, K. (2012). Recruiting and retaining low‐income, multi‐ethnic women into randomized controlled trials: Successful strategies and staffing. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33, 925–932. 10.1016/j.cct.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode, L. , Raman, A. S. , Murch, S. H. , Rollins, N. C. , & Gordon, J. L. (2020). Understanding the mother‐breastmilk‐infant “triad”. Science, 367, 1070–1072. 10.1126/science.aaw6147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnarchuk, J. L. , Eaton, W. O. , & Martens, P. J. (2006). Transitions in breastfeeding: Daily parent diaries provide evidence of behavior over time. Journal of Human Lactation, 22, 166–174. 10.1177/0890334406286992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck, K. , Stuebe, A. , Barnett, J. , Labbok, M. H. , Fletcher, J. , & Bernstein, P. S. (2014). Effect of primary care intervention on breastfeeding duration and intensity. American Journal of Public Health, 104, S119–S127. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck, K. A. , Trombley, M. , Freeman, K. , & McKee, D. (2005). Randomized, controlled trial of a prenatal and postnatal lactation consultant intervention on duration and intensity of breastfeeding up to 12 months. Pediatrics, 116, 1413–1426. 10.1542/peds.2005-0435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. (2016). What do women really want? Lessons for breastfeeding promotion and education. Breastfeeding Medicine, 11, 102–110. 10.1089/bfm.2015.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. R. L. , Dodds, L. , Legge, A. , Bryanton, J. , & Semenic, S. (2014). Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Public Health. Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 105, e179–e185. 10.17269/cjph.105.4244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetwynd, E. M. , Wasser, H. M. , & Poole, C. (2019). Breastfeeding support interventions by International Board Certified Lactation Consultants: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Human Lactation, 35, 424–440. 10.1177/0890334419851482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. (1999). Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: a self‐efficacy framework. Journal of Human Lactation, 15, 195–201. 10.1177/089033449901500303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. , Brown, H. K. , Chung‐Lee, L. , Abbass‐Dick, J. , Shorey, S. , Marini, F. , & Brennenstuhl, S. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among immigrant and Canadian‐born Chinese women. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15, e12687. 10.1111/mcn.12687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman‐Winter, L. (2013). Evidence‐based interventions to support breastfeeding. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 60, 169–187. 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell, M. , Bronsky, J. , Campoy, C. , Domellof, M. , Embleton, N. , Mis, N. F. , Hojsak, I. , Hulst, J. M. , Indrio, F. , Lapillonne, A. , & Molgaard, C. (2017). Complementary feeding: A position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 64, 119–132. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherman, V. J. , McKean, M. , Braunreuther, E. , Kair, L. R. , & Cabana, M. D. (2019). Minimizing the relationship between early formula use and breastfeeding cessation by limiting formula volume. Breastfeeding Medicine, 14, 533–537. 10.1089/bfm.2019.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J. , Mildon, A. , Stewart, S. , Underhill, B. , Ismail, S. , Di Ruggiero, E. , Tarasuk, V. , Sellen, D. W. , & O'Connor, D. L. (2021). Breastfeeding rates are high in a prenatal community support program targeting vulnerable women and offering enhanced postnatal lactation support: A prospective cohort study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20, 71. 10.1186/s12939-021-01386-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, T. (2014). Exclusive breastfeeding: Measurement and indicators. International Breastfeeding Journal, 9, 18. 10.1186/1746-4358-9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , Scanlon, K. S. , & Fein, S. B. (2008). Infant feeding and feeding transitions during the first year of life. Pediatrics, 122(Suppl 2), S36–S42. 10.1542/peds.2008-1315d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada . (2015). Nutrition for healthy term infants: recommendations from birth to six months. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/infant-feeding/nutrition-healthy-term-infants-recommendations-birth-six-months.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- Health Canada . (2020). Determining food security status. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview/determining-food-security-status-food-nutrition-surveillance-health-canada.html

- Kent, J. C. , Ashton, E. , Hardwick, C. M. , Rea, A. , Murray, K. , & Geddes, D. T. (2020). Causes of perception of insufficient milk supply in Western Australian mothers. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 17, e13080. 10.1111/mcn.13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessa, A. , Garcia, A. L. , Emmett, P. , Crozier, S. , Robinson, S. , Godfrey, K. M. , & Wright, C. M. (2020). Does early introduction of solid feeding lead to early cessation of breastfeeding? Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16, e12944. 10.1111/mcn.12944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. , Fein, S. B. , & Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. (2008). Association of breastfeeding intensity and bottle‐emptying behaviors at early infancy with infants' risk for excess weight at late infancy. Pediatrics, 122(Suppl 2), S77–S84. 10.1542/peds.2008-1315j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. , Scanlon, K. S. , & Serdula, M. K. (2005). The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutrition Reviews, 63, 103–110. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildon, A. , Francis, J. , Stewart, S. , Underhill, B. , Ng, Y. M. , Richards, E. , Rousseau, C. , Di Ruggiero, E. , Dennis, C.‐L. , O’Connor, D. L. , & Sellen, D. W. (2021). Effect on breastfeeding practices of providing in‐home lactation support to vulnerable women through the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program: Protocol for a pre/post intervention study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 16(49). 10.1186/s13006-021-00396-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel‐Weiss, J. , Taljaard, M. , & Kujawa‐Myles, S. (2014). Breastfeeding and lactation research: Exploring a tool to measure infant feeding patterns. International Breastfeeding Journal, 9, 5. 10.1186/1746-4358-9-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nommsen‐Rivers, L. A. , & Dewey, K. G. (2009). Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 334–342. 10.1007/s10995-008-0356-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, D. L. , Khan, S. , Weishuhn, K. , Vaughan, J. , Jefferies, A. , Campbell, D. M. , Asztalos, E. , Feldman, M. , Rovet, J. , Westall, C. , & Whyte, H. (2008). Growth and nutrient intakes of human milk‐fed preterm infants provided with extra energy and nutrients after hospital discharge. Pediatrics, 121, 766–776. 10.1542/peds.2007-0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Buccini, G. S. , Segura‐Pérez, S. , & Piwoz, E. (2019). Perspective: Should exclusive breastfeeding still be recommended for 6 months? Advances in Nutrition, 10, 931–943. 10.1093/advances/nmz039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine, C. G. , Scanlon, K. S. , Li, R. , Odom, E. , & Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. (2012). Baby‐friendly hospital practices and meeting exclusive breastfeeding intention. Pediatrics, 130, 54–60. 10.1542/peds.2011-3633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHAC . (2019). Breastfeeding. In Family‐centred maternity and newborn care: National guidelines. Public Health Agency of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- PHAC . (2020). Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/canada-prenatal-nutrition-program-cpnp.html

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , Piwoz, E. G. , Richter, L. M. , & Victora, C. G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387, 491–504. 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shealy, K. R. , Scanlon, K. S. , Labiner‐Wolfe, J. , Fein, S. B. , & Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. (2008). Characteristics of breastfeeding practices among US mothers. Pediatrics, 122(Suppl 2), S50–S55. 10.1542/peds.2008-1315f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . (2018). Employment insurance coverage survey ‐ 2018. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&lang=en&Item_Id=494316#qb367084

- Stuebe, A. (2009). The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2, 222–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe, A. M. , Bonuck, K. , Adatorwovor, R. , Schwartz, T. A. , & Berry, D. C. (2016). A cluster randomized trial of tailored breastfeeding support for women with gestational diabetes. Breastfeeding Medicine, 11, 504–513. 10.1089/bfm.2016.0069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulier, D. (2010). A call for clarity in infant breast and bottle‐feeding definitions for research. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 39, 627–634. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (2020). Percent of infants 0–5 months of age exclusively breastfed, by country and UNICEF region, 2019. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , Murch, S. , Sankar, M. J. , Walker, N. , & Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387, 475–490. 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps, M. D. M. , Yoshikawa, H. , & Demirci, J. R. (2019). Latent trajectories of infant breast milk consumption in the United States. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15, e12655. 10.1111/mcn.12655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2008). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Part 1: Definitions: Conclusion of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, D.C., USA. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO & UNICEF . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/gs_infant_feeding_text_eng.pdf [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Infant feeding practices

Table S2. Exclusive breastfeeding for three months or longer

Figure S1. Continuous exclusive breastmilk feeding and formula avoidance

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available in order to protect participant anonymity and confidentiality.