ABSTRACT

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between the Rehabilitation Activity Time score (RATs)—a score based on the level and duration of rehabilitation activities—of ventilated patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) and activities of daily living (ADL) dependence at discharge.

Methods:

This retrospective, single-center study evaluated patients aged >18 years who underwent mechanical ventilation in the ICU for at least 48 h. The patients were categorized into the low- and high-dose rehabilitation groups based on the median RATs. The primary outcome was the rate of ADL dependence at discharge, defined as a Barthel index of <70. The association between low or high doses of rehabilitation and the primary outcome was assessed using multiple logistic regression analysis adjusted by baseline factors.

Results:

The rate of ADL dependence at discharge was significantly lower in the high-dose rehabilitation group (low dose 81% vs. high dose 22%, P<0.001). Multivariate analysis showed a significantly lower ADL dependence at discharge among those who received high-dose rehabilitation (P<0.001). Increased RATs during the entire ICU admission period and during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability was significantly associated with lower ADL dependence at discharge (P<0.001). Moreover, a higher RATs from low-level activity before meeting the criteria for physiological stability also showed a significant association with lower ADL dependence at discharge (P=0.047).

Conclusions:

ADL dependence was significantly lower among those who underwent high-dose rehabilitation. The RATs was consistently associated with ADL dependence at discharge.

Keywords: activity daily living, Barthel index, mobilization, protocol

INTRODUCTION

Advances in lifesaving and perioperative management techniques for critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) have significantly increased the survival rate of such patients.1) In mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU, critical illness, use of drugs such as sedatives, bed rest, and physical inactivity can cause serious physical dysfunctions such as ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW).2) This physical dysfunction adversely affects the duration of mechanical ventilation, lengths of ICU and hospital stay, and reacquisition of physical function and activities of daily living (ADL) and worsens the prognosis in terms of survival and physical function.3,4,5)

The ABCDE bundle, which optimizes patient outcomes in the ICU, is recommended to prevent the persistence of physical impairment after ICU discharge, and one of its components, early rehabilitation, has been drawing international attention.6) The effects of early rehabilitation have been widely reported, including for the prevention of delirium,7) shortening of the mechanical ventilation period,7,8) improvement of physical function,9) shortening of ICU length of stay,9) and reduction of medical costs.10) However, in Japan, early rehabilitation programs vary depending on the situation in each hospital and the experience of therapists, and many hospitals cannot create or follow evidence-based protocols.11)

Previous clinical trials have quantified the maximum rehabilitation level achieved (e.g., range of motion, sitting, standing, and walking), but not the activity time of rehabilitation.11) Furthermore, we previously reported the relationship between rehabilitation activity time and ICU-AW; however, we have not been able to examine the relationship between ICU-AW and the rehabilitation dose based on activity level and activity time.8) In a previous study, Scheffenbichler et al. created a new tool for assessing the mobilization dose based on the level and duration of rehabilitation (the mobilization quantification score; MQS).12) The MQS was developed based on expert opinion and has been validated for reproducibility in multiple health centers.12) However, although previous studies have reported an association between the MQS in surgical ICUs and ADL dependence at discharge, they have not explored the association between the timing of the targeted increase in MQS and the ADL dependence. Against this background, we developed an evaluation scale that rationalizes the setting of 1 unit of activity time and rehabilitation level and simplifies the method of dose calculation so that it can be assessed at multiple hospitals even by staff who have not received special training.

There are few reports on the dose of physical activity during the ICU stay, and it is not clear whether it is better to increase the dose of physical activity from the early phase of admission in the ICU or to wait until the patient’s general condition has stabilized.13) Physical activity in the ICU depends on the patient’s level of consciousness, circulation, and respiratory factors and is a balance between early mobilization increasing the risk of worsening the patient’s condition and very late mobilization leading to muscle weakness and poor quality of life.14) Providing evidence on when to initiate rehabilitation of appropriate intensity for early recovery may help to avoid increased ADL dependence at discharge in mechanically ventilated patients. Therefore, a scoring system was developed by the authors [the Rehabilitation Activity Time score (RATs)], and this study investigated the relationship between ADL dependence at discharge and high-dose rehabilitation, as measured by this assessment method. As an additional verification, we investigated the reliability and validity of RATs as a physical activity assessment method in the ICU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Study Participants

This single-center, retrospective, cohort study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagoya Medical Center (2021012). We followed the STROBE guidelines.15) Consecutive patients who stayed in the ICU between April 2019 and March 2020 and were dependent on mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h were eligible for enrollment.

Patients younger than 18 years of age, those with a Barthel index (BI) <70 before admission, those with neurological complications or the lack of communication skills due to pre-existing mental diseases, and those in a terminal state were excluded. Coronavirus disease 2019 patients were not included in this study. We also excluded patients who died and those who did not complete the assessment during their ICU stay, as well as those who never met the criteria for physiological stability (Table 1) while in the ICU. As in previous studies, ADL dependence was defined as a BI <70 points,7) and mobilization was defined as being able to sit on the edge of the bed or a higher level of mobility.14,16)

Table 1. Criteria for physiological stability.

| Physiological stability variable | Variable range |

| Medical stability | |

| Bleeding tendency | May not get worse on mobilization |

| Fever | 38.5°C or less |

| Immediately after surgery | From the day after surgery |

| Bed rest order | When the attending physician determines that the condition requires rest |

| Cardiovascular stability | |

| Heart rate | 50–120 beats/min |

| Mean arterial blood pressure | 65–110 mmHg |

| Vasoactive medication infusions | No increase in vasoactive medications within 24 h |

| Respiratory stability | |

| Fraction of inspired oxygen | 0.6 or less |

| Positive end expiratory pressure | 10 cmH2O or less |

| Respiratory rate | 30 breaths/min or less |

| Pulse oximetry oxygen saturations | 90% or greater |

| Neurological stability | |

| Richmond Agitation–Sedation Score | –2 to 1 |

| Delirium | M6 (able to follow commands) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | M6 (able to follow commands) |

ICU Rehabilitation Protocol

Early goal-directed protocols for rehabilitation are used in our day-to-day procedures at the hospital, and safety verification data have already been reported.9,10,17,18) In the current study, we sought to mobilize all patients equally every day according to our hospital protocol, which has five rehabilitation levels based on the patient’s medical condition: level 1, passive range of motion and respiratory physical therapy; level 2, active range of motion; level 3, sitting exercise; level 4, standing exercise; and level 5, walking exercise. To increase the intensity of the rehabilitation above level 3, it was necessary for the patient to meet the stability criteria listed in Table 1.

In our study, while referring to the protocol, ICU physicians made the final decision regarding the rehabilitation level based on the patient’s condition. On weekdays, all patients were scheduled to receive at least one 20-min rehabilitation session per day. Regarding other ICU care strategies, our hospital followed the 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines6) and the clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome.19)

After discharge from the ICU, all patients underwent a rehabilitation program, including muscle strengthening, balancing, walking, and stair exercises, for more than 20 min/day on weekdays. The rehabilitation sessions were conducted by physical or occupational therapists according to the rehabilitation policy of the general ward of each hospital without any specific protocol.

Primary and Secondary Exposure Variable: RATs

Based on previous studies, and after discussions with two intensivists, two ICU physiotherapists, and two ICU nurses, the RATs system was created to quantify the intensity and activity time of rehabilitation (i.e., the activity “dose”).8,12,14,20,21) Rehabilitation levels were quantified based on the ICU rehabilitation protocol (i.e., levels 1–5). To calculate the dose of rehabilitation (intensity × activity time), each rehabilitation level was assigned a duration to define 1 unit of RATs (Table 2). The RATs was calculated according to each of the 5 levels and the rehabilitation activity time (level 1, 20 min=1 unit, 1 × units; level 2, 15 min=1 unit, 2 × units; level 3, 5 min=1 unit, 3 × units; level 4, 3 min=1 unit, 4 × units; and level 5, 1 min=1 unit, 5 × units). In Japan, the rehabilitation-related healthcare fee per unit is calculated in 20-min increments, and the RATs system was created in consideration of the medical situation in Japan (Table 3). Table 3 shows the details of how to calculate the RATs.

Table 2. Rehabilitation Activity Time score.

| ICU rehabilitation protocol level |

Unit | level of activity time × units | Rehabilitation intensity |

| 1 | 20 min=1 unit | 1 × units | Passive range of motion Examples: passive cycle ergometer, respiratory assistance techniques, electrical muscular stimulation |

| 2 | 15 min=1 unit | 2 × units | Active exercise in bed or exercise in chair or passively to chair Examples: Active or assistance range of motion, rolling, bridging, cycle ergometer, respiratory strength training and sputum discharge assistance |

| 3 | 5 min=1 unit | 3 × units | Sitting on edge of bed Includes all exercise from active sitting to less than standing |

| 4 | 3 min=1 unit | 4 × units | Standing of any kind or active stand-step/shuffle transfer to chair or step in place ≥4 steps or walk <15 feet (5 m) Includes all standing exercises less than 15 feet from the standing position with or without assistance or the use of assistive devices |

| 5 | 1 min=1 unit | 5 × units | Walk exercise ≥15 feet (5 m) Includes all walking exercises over 15 feet, with or without assistance or the use of assistive devices |

The Rehabilitation Activity Time scores were used to quantify the rehabilitation dose. For each rehabilitation session, activity time was noted for each rehabilitation level and multiplied by the corresponding number of units to calculate the rehabilitation dose.

Table 3. Details of Rehabilitation Activity Time score.

| Feature | Our study |

| How to calculate the Rehabilitation Activity Time |

The definition of the Rehabilitation Activity Time includes all activities aimed at mobilizing patients. All rehabilitation sessions that take place during the day are considered in calculating the total RATs for that duration. The duration (from start to finish) of each actually performed rehabilitation activity was measured to the nearest second using a stopwatch. The time needed to prepare for rehabilitation and rest periods during exercise, assessment, and measurement were excluded from the activity time. Therefore, only the duration of the exercises actually performed was recorded. |

| Calculation of the daily RATs | In one session, each rehabilitation level achieved will be multiplied by the corresponding exercise unit. The activity time of each rehabilitation session is rounded up. Some examples: ▪ Patients with 10 min of passive range of motion per session, three times a day: 1 × 3 (activity time is rounded up to 20 min per session). ▪ Patients spent 30 min preparing; nevertheless, they performed the active muscle training in bed for only 20 min (activity time was rounded up to 15 min × 2 units). |

To quantify the amount of rehabilitation activity performed in the ICU, we measured the average daily activity time for each rehabilitation protocol level. This measure was calculated by adding the durations of all activities actually performed in the ICU and dividing by the duration of ICU stay (days); the duration (from start to finish) of each rehabilitation protocol activity actually performed was measured in seconds using a stopwatch. The time needed to prepare for rehabilitation as well as the durations of the rest period, assessment, and measurement were excluded from the activity time. Therefore, the duration of the actual physical activity only was recorded. Even if the activity time was less than the specified time for 1 unit of that level, the calculation was performed by rounding up the activity time to 1 unit.12)

Data regarding rehabilitation provided by nurses or physiotherapists were obtained using billing information or electronic medical records. The primary exposure of interest was the average daily RATs. The daily RATs obtained from nursing and physiotherapy data was totaled throughout the ICU stay and then divided by the duration of ICU stay to obtain the average daily RATs (average daily RATs=total RATs while in the ICU / ICU length of stay). In addition, the mean RATs was bisected to determine the cutoff points for high/low-dose rehabilitation as the exposure variable. The median served as the cutoff for high/low-dose rehabilitation recruitment as a binary variable. For secondary exposure, the RATs after meeting the physiological stability criteria in the ICU and the RATs from low-intensity exercise (ICU rehabilitation protocol levels 1–2 only) in the ICU were used. Meeting the physiological stability criteria was defined as satisfying all the stability criteria listed in Table 1.

To investigate interobserver agreement between assessors, the role of assessor was performed by two physiotherapists (SW [main assessor], 10 years’ experience working in the ICU and KK, 5 years’ experience working in the ICU) and one nurse (MO, 7 years’ experience working in the ICU) at the National Hospital Organization, Nagoya Medical Center. The validity of the RATs was assessed by calculating the MQSs in parallel and analyzing their correlations.

Data Collection

Baseline characteristics were collected at the time of ICU admission and during the ICU stay; these included age, sex, body mass index, Charlson comorbidity index,22) BI before hospitalization, ICU admission diagnosis, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, and use of mechanical ventilation, continuous vasopressors, continuous analgesia, continuous sedation, steroids, neuromuscular blocking agents, and dialysis. The BI before hospitalization was calculated at the time of ICU admission based on the information provided by the family or by the patients if they were conscious.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ADL dependence at discharge, which was defined as a BI of 70 or lower.7) The secondary outcomes included medical costs, the duration of mechanical ventilation, the lengths of ICU and hospital stay, the rate of discharge to home and hospital survival, the incidence of delirium during ICU stay, and the incidence of ICU-AW at ICU discharge. To assess delirium, the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist23) was used. ICU-AW was defined as a Medical Research Council sum score (evaluated by a physical therapist) of less than 48 at the time of ICU discharge.24) Medical costs were calculated based on the diagnosis procedure combination/per diem payment system,25) and Japanese yen were converted to US dollars at an exchange rate of 108 yen/dollar.

Data regarding rehabilitation in the ICU and ward included the time to first rehabilitation and the time needed to meet the criteria for mobilization, time to first out-of-bed mobilization from ICU admission, highest ICU mobility scale26) during the ICU stay, mobilization within 7 days from ICU admission, and the number of daily rehabilitation sessions per person during ward care.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges or as numbers with percentages. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for nominal variables, as appropriate.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the relationship between the primary outcome and RATs, with age and APACHE II score as covariates. These factors have been shown to be related to the primary outcome in previous reports.27,28) To analyze secondary and other outcomes, post-hoc analysis and multiple linear and logistic regression analyses were performed for log-transformed continuous and categorical variables, respectively, using the same covariates as in the analysis of the primary outcome.

As post-hoc analysis, logistic regression analysis was performed with ADL independence at discharge as the objective variable and the RATs during the entire ICU admission period or the RATs during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability as the explanatory variable. Furthermore, logistic regression analysis was performed using the same procedure, with low-intensity rehabilitation (ICU rehabilitation protocol level 1–2) and the number of daily rehabilitation sessions per person during ward care as explanatory variables.

Reliability between assessors was verified by calculating the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (2.1) for the mean RATs. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between the MQS and RATs during the entire ICU admission period or only after meeting the criteria for physiological stability. All analyses were performed using JMP (version 13.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P <0.05.

Ethics and Consent

The study was conducted after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Nagoya Medical Center Hospital (IRB approval number 12). All data were de-identified to protect the confidentiality of the personal information. The study qualified for exempt status according to the IRB because the data were collected from existing patient records. Therefore, the need for patient consent was waived.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

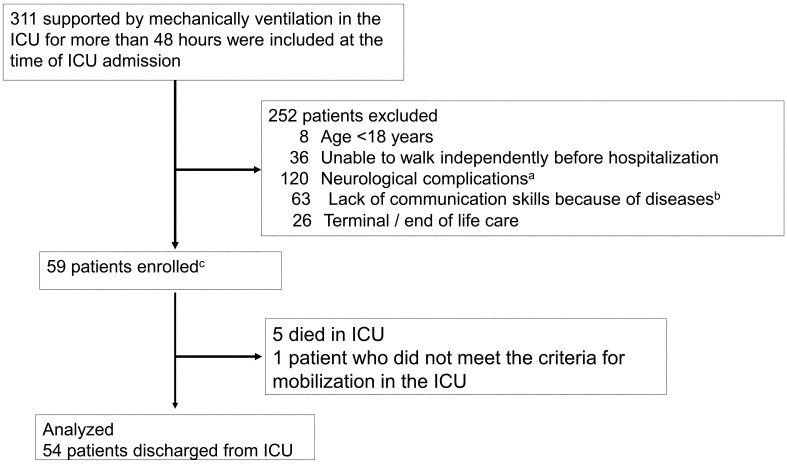

Of the 311 patients screened, 59 were enrolled (Fig. 1), and finally 54 patients were included in the analysis, after excluding those who died or did not meet the criteria for physiological stability. The median of the daily mean RATs during the entire ICU admission period in this study was 3.6 (interquartile range 1.4–9.6). Based on the median, the patients were divided into a high-dose rehabilitation group (n=27) and a low-dose rehabilitation group (n=27). There were no differences in the measured baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the patient selection process. aNeurological complications included cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, acute subdural hematoma, acute epidural hematoma, traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, and encephalitis. If neurological complications were suspected based on the imaging, we did not exclude asymptomatic patients. bDiseases included depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, dementia, cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and alcoholism.

Table 4. Baseline characteristics at the time of intensive care unit admission.

| Variables | All patients, n= 54 |

Low dose of rehabilitation (mean RATs <3.6), n=27 | High dose of rehabilitation (mean RATs >3.6), n=27 | P |

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 69 [60–73] | 69 [57–78] | 69 [63–70] | 0.544 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 36 (67) | 18 (67) | 18 (67) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median [IQR] | 20 [17–23] | 19 [16–23] | 21 [18–23] | 0.307 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median [IQR] | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–4] | 0.393 |

| Barthel index before hospitalization, median [IQR] a | 95 [90–100] | 95 [85–100] | 95 [90–100] | 0.549 |

| Admission source, n (%) | ||||

| Emergency department | 36 (67) | 21 (78) | 15 (56) | 0.099 |

| General ward in hospital | 12 (22) | 6 (22) | 6 (22) | |

| Planned post-operation b | 6 (11) | 0 (4) | 6 (22) | |

| ICU admission diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Acute respiratory failure (including pneumonia) | 10 (18) | 5 (19) | 5 (19) | 0.221 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 4 (15) | |

| Gastric or colonic surgery | 18 (33) | 10 (37) | 8 (30) | |

| Sepsis, non-pulmonary | 8 (15) | 5 (19) | 3 (11) | |

| Other diagnoses | 13 (25) | 6 (22) | 7 (26) | |

| APACHE II score, median [IQR] | 22 [15–26] | 22 [15–24] | 24 [15–30] | 0.253 |

| SOFA at ICU admission, median [IQR] | 8 [6–9] | 7 [6–9] | 8 [6–9] | 0.525 |

| The use of continuous vasopressor during ICU stay, n (%) | 43 (80) | 22 (81) | 21 (78) | 1.000 |

| The use of continuous analgesia during ICU stay, n (%) | 51 (94) | 27 (100) | 24 (89) | 0.236 |

| The use of continuous sedation during ICU stay, n (%) | 53 (98) | 27 (100) | 26 (96) | 1.000 |

| The use of steroids during ICU stay, n (%) | 20 (37) | 12 (44) | 8 (30) | 0.398 |

| The use of neuromuscular blocking agent during ICU stay, n (%) | 12 (22) | 4 (15) | 8 (30) | 0.327 |

| The use of dialysis during ICU stay, n (%) | 17 (31) | 12 (44) | 5 (19) | 0.077 |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or number (%).

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

a Barthel index before hospitalization was scored at the time of ICU admission based on the information from the family or the patients if they were conscious.

b Breakdown of planned post-operation: heart bypass surgery, 1 (17%); valvular surgery, 1 (17%); gastrointestinal surgery, 4 (66%).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The rate of ADL dependence at discharge was significantly lower in the high-dose rehabilitation group than in the low-dose rehabilitation group (81% vs. 22%, adjusted P <0.001) (Table 5). The incidence of ICU-AW at ICU discharge was also significantly lower in the high-dose rehabilitation group than in the low-dose rehabilitation group (70% vs. 37%, adjusted P=0.016).

Table 5. Comparison of clinical and economic primary outcomes.

| Outcomes | Low dose of rehabilitation (mean rats <3.6), n=27 | High dose of rehabilitation (mean rats >3.6), n=27 | P-value | Adjusted P-value |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| ADL dependence at discharge, n (%) | 22 (81) | 6 (22) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Clinical outcomes and physical assessment | ||||

| Total medical costs (US dollars), median [IQR] | 26335 [19726–39603] | 28042 [16935–40410] | 0.993 | 0.976 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days), median [IQR] | 6 [5–9] | 4 [2–6] | 0.007 | 0.076 |

| ICU length of stay (days), median [IQR] | 8 [6–9] | 7 [6–11] | 0.931 | 0.905 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), median [IQR] | 33 [27–43] | 28 [22–56] | 0.539 | 0.658 |

| Discharge to home, n (%) | 15 (56) | 18 (67) | 0.402 | 0.299 |

| Hospital survival, n (%) | 27 (100) | 24 (89) | 0.236 | 0.999 |

| ICU-AW at ICU discharge, n (%) | 19 (70) | 10 (37) | 0.028 | 0.016 |

| Delirium during ICU stay, n (%) | 8 (30) | 4 (15) | 0.327 | 0.130 |

| Rehabilitation in ICU and Ward | ||||

| Time to first rehabilitation from the ICU admission (days) | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | 0.473 | 0.529 |

| Time to first meet the criteria for mobilization from the ICU admission (days) | 6 [5–7] | 4 [3–6] | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Time to first out of bed mobilization from the ICU admission (days) | 8 [5–9] | 4 [3–7] | 0.014 | 0.058 |

| The highest ICU mobility scale during ICU stay (score) | 1 [1–3] | 7 [5–10] | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Achieved mobilization within 7 days from the ICU admission | 10 (37) | 21 (78) | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| Number of daily rehabilitation sessions per person during ward care | 1 [1–1] | 1 [1–1] | 0.256 | 0.298 |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or number (%).

ICU-AW, intensive care unit acquired weakness.

The high-dose rehabilitation group required a significantly shorter time to meet the criteria for mobilization than the low-dose rehabilitation group. Furthermore, the high-dose rehabilitation group achieved a significantly higher rate of mobilization within 7 days of ICU admission and higher ICU mobility during the ICU stay.

Post-hoc Sensitivity Analysis

Logistic regression analysis using the RATs at discharge from the ICU as the explanatory variable showed a significant association between increased RATs and decreased ADL dependence at discharge (odds ratio [OR]: 0.67, confidence interval [CI]: 0.53–0.83, adjusted P <0.001). The RATs during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability also showed a significant association with decreased ADL dependence at discharge (OR: 0.77, CI: 0.67–0.89; adjusted P <0.001) (Table 6). Logistic regression analysis using low activity level (ICU rehabilitation protocol level 1–2) RATs on discharge from the ICU as the explanatory variable showed a non-significant association between increased RATs and decreased ADL dependence at discharge (OR: 0.59, CI: 0.24–1.26, adjusted P=0.165). However, the low activity level RATs during ICU admission before meeting the criteria for physiological stability showed a significant association with decreased ADL dependence at discharge (OR: 0.25, CI: 0.05–0.98, adjusted P=0.047). The number of daily rehabilitation sessions per person during ward care showed no significant association with decreased ADL dependence at discharge (OR: 0.17, CI: 0.01–6.81, adjusted P=0.246) (Table 6).

Table 6. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis of RATs in different conditions as a factor for dependence of activities of daily living .

| Variable | Univariate | Model 1 adjusted for age and APACHE II |

||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| RATs during the entire ICU admission period | 0.69 | 0.57 − 0.85 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.53 − 0.83 | <0.001 |

| RATs during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability | 0.78 | 0.68 − 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.77 | 0.67 − 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Low-intensity (ICU rehabilitation protocol 1–2) RATs during the entire ICU admission period | 0.57 | 0.18 − 1.21 | 0.125 | 0.59 | 0.24 − 1.26 | 0.165 |

| Low-intensity (ICU rehabilitation protocol 1–2) RATs during ICU admission before meeting the criteria for physiological stability | 0.23 | 0.06 − 0.95 | 0.036 | 0.25 | 0.05 − 0.98 | 0.047 |

| Number of daily rehabilitations per person during ward | 0.21 | 0.01 − 7.27 | 0.301 | 0.17 | 0.01 − 6.81 | 0.246 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Model 1: multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the primary outcome with age and APACHE II score as covariates. These two covariates have been considered as factors related to the primary outcome in previous reports.

Inter-assessor Reliability

The three assessors were able to measure the RATs in 54 subjects. The ICC (2.1) for the mean RATs during ICU admission was 0.98 (0.96–0.99) for two physiotherapists and 0.91 (0.85–0.96) for a physiotherapist and nurse (Table 7).

Table 7. Inter-assessor reliability of RATs score.

| Physiotherapist and physiotherapist ICC (95% CI) |

Physiotherapist and nurse ICC (95% CI) |

|

| RATs during the entire ICU admission period | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.91 (0.85–0.96) |

ICC, interclass correlation coefficient.

Validity

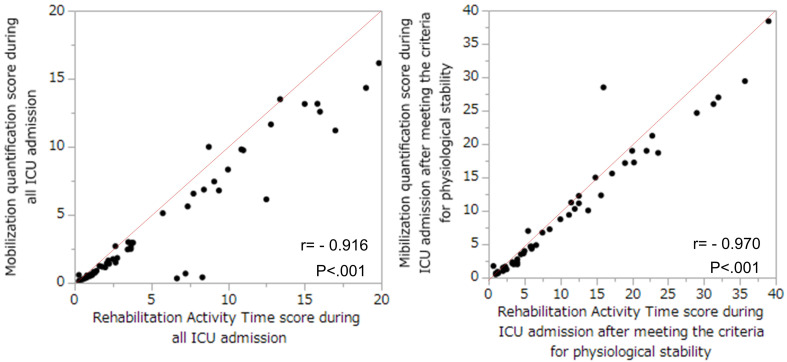

The RATs showed a linear correlation with the MQS during ICU admission (r=0.916, P <0.001) and with the MQS during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability (r=0.970, P <0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlations between the Rehabilitation Activity Time score (RATs) and the mobilization quantification score (MQS). (Left) The correlation between RATs and MQS during the entire ICU admission period (r= −0.916, P<0.001). (Right) The correlation between RATs and MQS during the ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability (r= −0.970, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

We created an assessment scale (the RATs) for physical activity in the ICU based on the medical situation in Japan and applied it to a mixed population of patients who underwent mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Furthermore, the RATs correlated significantly with the MQS both during the entire ICU admission period and during ICU admission after meeting the criteria for physiological stability. In the present study, the rate of ADL dependence at discharge was significantly lower in the high-dose rehabilitation group, and multivariate analysis showed that the high-dose rehabilitation group had significantly decreased ADL dependence at discharge. Increased RATs, both during the entire ICU admission period and after meeting the criteria for physiological stability, was significantly associated with decreased ADL dependence at discharge. Moreover, an increase in low-level (ICU rehabilitation protocol levels 1–2) RATs before meeting the criteria for physiological stability was significantly associated with a decrease in ADL dependence at discharge. However, the number of daily rehabilitation sessions per person during ward care showed no significant association with ADL dependence at discharge. The RATs was assessed by ICU staff with excellent inter-observer reliability. Reliability was excellent both in physiotherapist-to-physiotherapist and in physiotherapist-to-nurse comparisons.

In a previous study using MQS, high-dose rehabilitation in surgical ICUs was also an independent predictor of ADL dependence after discharge.13) In the current study, as in the previous study, the rehabilitation dose, which considered not only the mobilization level but also the actual activity time, was associated with ADL dependence in mechanically ventilated patients. The timing of early rehabilitation differs across studies.7,20) However, recent studies have shown that initiation of rehabilitation within 48–72 h of ICU admission may be optimal.29) Our previous study, which focused on the level of early rehabilitation, showed that achieving a level of mobilization higher than that of sitting on the edge of the bed within 1 week of admission to the general ICU predicts independent walking at discharge.14) Other previous studies have described the effects of sitting on the edge of the bed as beneficial not only for physical function but also for respiratory and cognitive function and level of consciousness.30) High-dose rehabilitation is an independent predictor of ADL dependence at discharge.13) The association between the dose of rehabilitation and ADL dependence is affected by the duration of the rehabilitation sessions and not just on the maximum rehabilitation level achieved. Our current results emphasize the need to quantify the activity time of rehabilitation when investigating the effects of early rehabilitation on mechanically ventilated patients. Therefore, our study is in line with previous studies reporting the need to investigate not only the intensity and timing of early rehabilitation but also the activity time. In the future, daily rehabilitation dose goals related to disease severity and disease-specific rehabilitation should be considered to improve the rehabilitation protocol. However, in the current study, unlike in previous studies, there were no significant differences in total medical costs, ICU and hospital lengths of stay, the duration of mechanical ventilation, the rate of discharge to home, or the incidence of delirium.7,8,9,10) Since each median, other than total medical cost, tended to improve in the high-dose rehabilitation group, future multicenter studies using larger samples of patients should be carried out to strengthen these findings. Furthermore, the long-term medical costs after acute discharge or transfer should be investigated in future studies.

In this study, the RATs for both the entire ICU admission period and the period after meeting the criteria for physiological stability were significantly associated with ADL dependence at discharge. In our previous study, there were barriers to mobilization (circulation, respiratory, consciousness, symptoms, and medical staff-related factors), and medical staff-related factors and consciousness levels were particularly associated with walking independence at discharge.14) In the current study, patients were probably hemodynamically unstable and required vasopressor support, given that the vasopressor usage rate on admission to the ICU was 80%. Most patients in this study may not have been able to tolerate mobilization, consistent with the expert consensus that it is difficult for patients to get out of bed or achieve mobilization during catecholamine therapy.11) In the presence of circulatory instability, the mobilization rates are usually low, and passive exercise,31) cycle ergometer exercise,32) and neuromuscular electrical stimulation33) may be used. Determination of the optimal rehabilitation level and duration before the patient achieves physiological stability should be the focus of future studies.

The main limitations of our research are the lack of complete data, the small sample size, and the single-center approach. Only 17% of ICU patients were included during the study period, which is an important source of selection bias, and this fact may limit the generalizability of the findings to other ICUs. Furthermore, except for age and the APACHE II score, other factors assumed to be associated with ADL decline during the ICU stay were not adjusted for in this study. Addressing these issues requires multicenter collaborations with larger sample sizes. In addition, only ADL dependence at discharge and medical costs during hospitalization were evaluated as outcomes. However, the prevention of physical dysfunction has become a new challenge in the fields of emergency and intensive care, with an emphasis on long-term quality of life and functional outcomes after discharge.34,35) Additionally, the low-dose rehabilitation group required a significantly longer time to meet the criteria for physiological stability than did the high-dose rehabilitation group. Because of the lack of relevant data and the small sample size, the potential factors preventing increased activity time in low-dose rehabilitation groups and their impact could not be addressed. However, to address these factors as much as possible, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with age and disease severity as covariates. Future studies are needed to investigate the impact of factors that prevent increased activity time in low-dose rehabilitation groups. Furthermore, the intensity of rehabilitation therapy provided after ICU discharge and the quality of nurse rehabilitation performed while in the ICU were not investigated. In this study, we converted the RATs, which is a continuous variable, to a binary variable based on the median value. For RATs above the median, selection bias can occur when all patients are included in the high-dose mobilization group with high variability. As in previous studies, it is difficult to integrate the duration of mobilization across different categories of mobilization into a single score that optimizes their relative contributions to rehabilitation. Different definitions of rehabilitation duration may have influenced the associations with the rehabilitation dose. Because of the nature of the current study, the data obtained inevitably introduced observer and subject biases. Furthermore, unmeasured confounders may have influenced the observed associations of rehabilitation with dependent ADL at discharge, length of hospital stay, and medical costs in this study. For example, data regarding medications, sedation dose, pain, infections, ventilator settings, and weaning were not collected but might have influenced the findings.6,10,33,36) Finally, we did not conduct a detailed assessment of the subjects’ physical function, and the assessment of dysfunction was limited to that for ADL dependence at discharge. Consequently, further prospective studies are needed to investigate the influence of these factors. A multicenter, prospective study is needed to address the unanswered questions of this study and to explore correlations with other factors.

CONCLUSIONS

High-dose rehabilitation in the ICU (assessed using RATs, which quantifies intensity × activity time) was significantly associated with decreased ADL dependence at discharge. Moreover, the application of low-intensity exercise before the acquisition of physiological stability was also positively associated with ADL dependence at discharge. The association between the dose of rehabilitation and ADL dependence depends on the duration of the rehabilitation sessions and not simply on the maximum mobilization level achieved. Early rehabilitation in the ICU, not only in terms of timing and level but also of activity duration, may be important for maximizing the beneficial effects of exercise in terms of patient outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study coordinators Hajime Katsukawa and Akiko Kada. The authors also thank the entire ICU staff at Nagoya Medical Center Hospital.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pandharipande PP,Girard TD,Jackson JC,Morandi A,Thompson JL,Pun BT,Brummel NE,Hughes CG,Vasilevskis EE,Shintani AK,Moons KG,Geevarghese SK,Canonico A,Hopkins RO,Bernard GR,Dittus RS,Ely EW, BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators: Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1306–1316. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schefold JC,Bierbrauer J,Weber-Carstens S: Intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW) and muscle wasting in critically ill patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010;1:147–157. , 10.1007/s13539-010-0010-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Brahmbhatt N,Murugan R,Milbrandt EB: Early mobilization improves functional outcomes in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2010;14:321. 10.1186/cc9262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens RD,Marshall SA,Cornblath DR,Hoke A,Needham DM,de Jonghe B,Ali NA,Sharshar T: A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med 2009;37(Suppl):S299–S308. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe S,Kotani T,Taito S,Ota K,Ishii K,Ono M,Katsukawa H,Kozu R,Morita Y,Arakawa R,Suzuki S: Determinants of gait independence after mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a Japanese multicenter retrospective exploratory cohort study. J Intensive Care 2019;7:53. 10.1186/s40560-019-0404-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devlin JW,Skrobik Y,Gélinas C,Needham DM,Slooter AJ,Pandharipande PP,Watson PL,Weinhouse GL,Nunnally ME,Rochwerg B,Balas MC,van den Boogaard M,Bosma KJ,Brummel NE,Chanques G,Denehy L,Drouot X,Fraser GL,Harris JE,Joffe AM,Kho ME,Kress JP,Lanphere JA,McKinley S,Neufeld KJ,Pisani MA,Payen JF,Pun BT,Puntillo KA,Riker RR,Robinson BR,Shehabi Y,Szumita PM,Winkelman C,Centofanti JE,Price C,Nikayin S,Misak CJ,Flood PD,Kiedrowski K,Alhazzani W: Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018;46:e825–e873. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweickert WD,Pohlman MC,Pohlman AS,Nigos C,Pawlik AJ,Esbrook CL,Spears L,Miller M,Franczyk M,Deprizio D,Schmidt GA,Bowman A,Barr R,McCallister KE,Hall JB,Kress JP: Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1874–1882. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe S,Iida Y,Ito T,Mizutani M,Morita Y,Suzuki S,Nishida O: Effect of early rehabilitation activity time on critically ill patients with intensive care unit-acquired weakness: a Japanese retrospective multicenter study. Prog Rehabil Med 2018;3:n/a. 10.2490/prm.20180003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe S,Morita Y,Suzuki S,Someya F: Association between early rehabilitation for mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients and oral ingestion. Prog Rehabil Med 2018;3:n/a. 10.2490/prm.20180009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K,Ogura T,Takahashi K,Nakamura M,Ohtake H,Fujiduka K,Abe E,Oosaki H,Miyazaki D,Suzuki H,Nishikimi M,Komatsu M,Lefor AK,Mato T: A progressive early mobilization program is significantly associated with clinical and economic improvement: a single-center quality comparison study. Crit Care Med 2019;47:e744–e752. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ad Hoc Committee for Early Rehabilitation, The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine: Evidence based expert consensus for early rehabilitation in the intensive care unit [in Japanese]. Jpn J Int Care Med 2017;24:255–303. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheffenbichler FT,Teja B,Wongtangman K,Mazwi N,Waak K,Schaller SJ,Xu X,Barbieri S,Fagoni N,Cassavaugh J,Blobner M,Hodgson CL,Latronico N,Eikermann M: Effects of the level and duration of mobilization therapy in the surgical ICU on the loss of the ability to live independently: an international prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 2021;49:e247–e257. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu K,Ogura T,Takahashi K,Nakamura M,Ohtake H,Fujiduka K,Abe E,Oosaki H,Miyazaki D,Suzuki H,Nishikimi M,Lefor AK,Mato T: The safety of a novel early mobilization protocol conducted by ICU physicians: a prospective observational study. J Intensive Care 2018;6:10. 10.1186/s40560-018-0281-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe S,Liu K,Morita Y,Kanaya T,Naito Y,Suzuki S,Katsukawa H,Kotani T,Hasegawa Y: A survey of daily differences in the barriers and implementation status of early mobilization in intensive care unit: a single center retrospective observational cohort study. J Nagoya Med Sci 2021;83:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandenbroucke JP,von Elm E,Altman DG,Gøtzsche PC,Mulrow CD,Pocock SJ,Poole C,Schlesselman JJ,Egger M, STROBE Initiative: Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007;18:805–835. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrold ME,Salisbury LG,Webb SA,Allison GT, Australia and Scotland ICU Physiotherapy Collaboration: Early mobilisation in intensive care units in Australia and Scotland: a prospective, observational cohort study examining mobilisation practises and barriers. Crit Care 2015;19:336. 10.1186/s13054-015-1033-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe S,Morita Y,Suzuki S,Someya F: Association between early rehabilitation for mechanically ventilated ICU patients and their walking independence: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Phy Med Rehab 2017;1:106. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsukawa H,Ota K,Liu K,Morita Y,Watanabe S,Sato K,Ishii K,Yasumura D,Takahashi Y,Tani T,Oosaki H,Nanba T,Kozu R,Kotani T: Risk factors of patient-related safety events during active mobilization for intubated patients in intensive care units – a multi-center retrospective observational study. J Clin Med 2021;10:2607. 10.3390/jcm10122607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto S,Sanui M,Egi M,Ohshimo S,Shiotsuka J,Seo R,Tanaka R,Tanaka Y,Norisue Y,Hayashi Y,Nango E, ARDS Clinical Practice Guideline Committee from the Japanese Society of Respiratory Care Medicine and the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine: The clinical practice guideline for the management of ARDS in Japan. J Intensive Care 2017;5:50. 10.1186/s40560-017-0222-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris PE,Goad A,Thompson C,Taylor K,Harry B,Passmore L,Ross A,Anderson L,Baker S,Sanchez M,Penley L,Howard A,Dixon L,Leach S,Small R,Hite RD,Haponik E: Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2238–2243. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainsworth B,Haskell WL,Herrmann SD,Meckes N,Bassett DR Jr,Tudor-Locke C,Greer JL,Vezina J,Whitt-Glover MC,Leon AS: 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1575–1581. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME,Pompei P,Ales KL,MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergeron N,Dubois MJ,Dumont M,Dial S,Skrobik Y: Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:859–864. 10.1007/s001340100909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel BK,Pohlman AS,Hall JB,Kress JP: Impact of early mobilization on glycemic control and ICU-acquired weakness in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest 2014;146:583–589. 10.1378/chest.13-2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakagawa Y,Takemura T,Yoshihara H,Nakagawa Y: A new accounting system for financial balance based on personnel cost after the introduction of a DPC/DRG system. J Med Syst 2011;35:251–264. 10.1007/s10916-009-9361-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodgson C,Needham D,Haines K,Bailey M,Ward A,Harrold M,Young P,Zanni J,Buhr H,Higgins A,Presneill J,Berney S: Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung 2014;43:19–24. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim RY,Murphy TE,Doyle M,Pulaski C,Singh M,Tsang S,Wicker D,Pisani MA,Connors GR,Ferrante LE: Factors associated with discharge home among medical ICU patients in an early mobilization program. Crit Care Explor 2019;1:e0060. 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito M,Hori K,Okamura D,Sakamoto J,Suzuki S,Nakazawa M,Watanabe N,Kozawa T: Determinants of activities of daily living at discharge in elderly heart failure patients [In Japanese]. Jpn J Jpn Phys Ther Assoc 2015;42:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn KF,Schaller SJ: Comment on early versus delayed mobilization for in-hospital mortality and health-related quality of life among critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Okada et al., Journal of Intensive Care 2019). J Intensive Care 2020;8:21. 10.1186/s40560-020-0436-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okubo N: Effectiveness of the sitting position without back support. Australas J Neurosci 2015;25:31–39. 10.21307/ajon-2017-111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iida Y,Sakuma K: Skeletal muscle dysfunction in critical illness. Intech 2017;69051:142–168. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burtin C,Clerckx B,Robbeets C,Ferdinande P,Langer D,Troosters T,Hermans G,Decramer M,Gosselink R: Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2499–2505. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Routsi C,Gerovasili V,Vasileiadis I,Karatzanos E,Pitsolis T,Tripodaki ES,Markaki V,Zervakis D,Nanas S: Electrical muscle stimulation prevents critical illness polyneuromyopathy: a randomized parallel intervention trial. Crit Care 2010;14:R74. 10.1186/cc8987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters BD,Eberlein M,Leung J,Needham DM,Pronovost PJ,Sevransky JE: Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1276–1283. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Needham DM,Davidson J,Cohen H,Hopkins RO,Weinert C,Wunsch H,Zawistowski C,Bemis-Dougherty A,Berney SC,Bienvenu OJ,Brady SL,Brodsky MB,Denehy L,Elliott D,Flatley C,Harabin AL,Jones C,Louis D,Meltzer W,Muldoon SR,Palmer JB,Perme C,Robinson M,Schmidt DM,Scruth E,Spill GR,Storey CP,Render M,Votto J,Harvey MA: Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502–509. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leditschke AI,Green M,Irvine J,Bissett B,Mitchell IA: What are the barriers to mobilizing intensive care patients? Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2012;23:26–29. 10.1097/01823246-201223010-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]