Abstract

Precis

Patients with early-onset pancreatic cancer receive more oncologic therapy compared to older patients, however treatment underutilization remains substantial for all age groups. Efforts to improve access and treatment utilization may improve survival.

Background

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is uncommon in patients <50 years, although incidence is increasing. This study characterizes treatment utilization for early-onset (EOPC) vs average-age-onset PC (AOPC) and identifies factors associated with failure to receive treatment.

Methods

NCDB was queried for patients with EOPC (age<50) and AOPC (age≥50) from 2004-2016. Multinomial regression was used to compare utilization (single-modality vs multimodal+/−surgery vs no treatment) between EOPC vs AOPC. Kaplan-Meier methods estimate overall survival (OS).

Results

Of 248,634 patients, 15,710 (6.3%) had EOPC. There were more male (56 vs 50%), non-White, uninsured/privately insured (61 vs 30%) EOPC patients vs AOPC, without notable differences in clinical stage distribution. EOPC patients received more chemotherapy (38 vs 29%), surgery (9 vs 6.9%), chemoradiation (12 vs 9.2%) and multimodal treatment (21 vs 15%). The odds of receiving multimodal curative therapy was significantly higher for EOPC vs AOPC, after adjusting for confounders ((OR 3.89, 95%CI:3.66-4.15), p<0.001). Compared to 39% of AOPC patients, 19% with EOPC received no treatment. AOPC patients more frequently declined chemotherapy (15 vs 9.5%). One-year OS was higher for EOPC vs AOPC across each stage (0/I/II:72% (95%CI:71-74) vs 53% (95%CI:53-54); III:48% (95%CI:45-50) vs 38% (95%CI:37-38); IV:25% (95%CI:24-26) vs 15% (95%CI:15-15)) and treated patients (0/I/II:75% (95%CI:74-77) vs 64% (95%CI:63-64); III:51% (95%CI:49-54) vs 47% (95%CI:47-48); IV:29% (95%CI:28-31) vs 23% (95%CI:23-24)).

Conclusions

EOPC patients receive more oncologic therapy compared to AOPC, although the intensity, type and duration of chemotherapy is not available in NCDB; however, 19% and 39% received no therapy, respectively. Underutilization may explain suboptimal oncologic outcomes. Efforts to improve access and treatment utilization in all age groups are warranted.

Keywords: Pancreatic neoplasms, young onset, treatment, utilization, survival

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, estimated to result in 47,050 deaths in 2020 alone.1 While PC is classically considered a ‘disease of the elderly’, early-onset pancreatic cancer (EOPC), defined as diagnosis before 45-55 years of age, has been increasing relative to older onset disease.2-4 While the risk factors for EOPC are similar to average-age-onset PC (AOPC), including obesity, smoking, and alcohol use, studies suggest that EOPC patients may present with distinctive clinical, pathologic, and genomic features, which may affect prognosis.4-11

In recent years, increased attention has focused on defining clinicopathologic features and oncologic outcomes for patients with EOPC. Owing to small sample sizes from single-institution series, reported outcomes for patients with EOPC are heterogenous.12,13 While some studies have suggested that EOPC patients tend to present with more advanced stage and worse prognosis, others have observed improved survival in younger patients, due to improved performance and functional status in this group, and possibly more therapy.4,13-15 Studies have further suggested a different demographic for patients with EOPC, with significantly more males in the EOPC cohort compared to AOPC patients.9,16

Little is known about the relationship between age at diagnosis and current treatment patterns and how treatment utilization affects oncologic outcomes. For EOPC patients, efforts to improve survival may be amplified given the potential number of life years lost in this population.9,16 Further, due to better functional reserve, these patients may also be candidates for more aggressive treatment in the absence of significant comorbidities. Historically, low treatment utilization for all patients with PC has been attributed to cynicism regarding therapeutic efficacy, given the poor overall prognosis.17 It has been suggested, however, that patients with EOPC may be more likely to receive and benefit from surgery, radiation and chemotherapy compared to AOPC patients.4,5,14

Characterizing current treatment patterns for patients with EOPC can highlight potential areas of over- or under-utilization which can be addressed to improve outcomes for all patients with PC. To assess contemporary patterns of care for PC and determine whether differences in utilization correlate with differences in oncologic outcomes, we utilized the National Cancer Database (NCBD), which provides hospital registry data from over 1,500 Commission on Cancer (CoC) accredited programs. The objectives of this study were 1) to assess differences in treatment utilization between EOPC and AOPC patients; 2) to understand the characteristics of patients who do not receive treatment for PC; 3) to evaluate changes in treatment over time for patients with EOPC and AOPC; and 4) to determine how differences in utilization may affect survival in patients with PC.

Methods

Data Source and Patient Selection

The NCDB is a program of the CoC of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. This hospital-based cancer registry captures approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases in the United States. Data obtained from the NCDB are de-identified and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant. This project was approved, and waiver of consent was granted by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review and Privacy Board.

We identified patients greater than 18 years of age with PC diagnosed between 2004-2016, using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Revision histology codes: 800, 801, 802, 803, 804, 805, 807, 814, 821, 823, 825, 826, 831, 832, 843, 844, 845, 847, 848, 849, 850, 851, 852, 855, 856, 857. Patients with invasive pancreatic tumors and a single malignant primary were included. The selected cohort was divided into two groups based on age at PC diagnosis: EOPC was defined as age < 50 years and AOPC was defined as age ≥ 50 years.

Patient and Treatment Variables

Patient demographic variables including age, race, insurance status, and Charlson-Deyo score were extracted from the NCDB database. Clinical tumor stage, nodal stage and overall stage were based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging guidelines. No information on somatic or germline mutations was available in the NCDB. Chemotherapy was categorized as single-agent, multi-agent or not otherwise specified (NOS). Surgery was categorized based on the NCDB site-specific surgical codes. These included local excision of tumor; partial pancreatectomy; local or partial pancreatectomy and duodenectomy; total pancreatectomy; total pancreatectomy and subtotal gastrectomy; extended pancreatoduodenectomy; pancreatectomy NOS; or surgery NOS, which includes ‘surgical procedures to the primary site, but no information on the type of surgical procedure provided’.18 Receipt of radiation therapy was categorized as a binary variable. Single modality was defined as receipt of any one of the following three treatment modalities at any time point: chemotherapy, surgery and radiation therapy. Multimodal therapy was defined in this study as receipt of more than one of the following three treatment modalities: chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic, disease and treatment characteristics were summarized between EOPC and AOPC using frequency and percentages for categorical variables, median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous factors. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from date of disease diagnosis until date of death or last contact. OS was estimated by Kaplan-Meier methods and compared between groups using log-rank test. The nominal outcome of treatments was grouped in the following categories: no treatment, any single modality (chemotherapy only, surgery only, or radiation only), multimodal without surgery (chemotherapy and radiation), and multimodal with surgery (chemotherapy and surgery, radiation and surgery, or chemoradiation and surgery). Although use of radiation therapy has decreased over the study period, we elected to include this modality in our models as there remains clinical equipoise on its role in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. To examine the association between EOPC versus AOPC on the dependent nominal outcomes from the whole cohort, a multinomial logistic regression model was applied and the no treatment was used as a reference category.19 Given the small number (<5%) of patients with unknown treatment, patients with unknown or no treatment were grouped in the multivariable analyses. Patients with stage 0 disease were excluded from these models, as this was a very small number of patients, with uniquely defined treatment patterns. The multivariable multinomial logistic model was constructed by adjusting known confounders including Charlson-Deyo score (None vs 1 vs 2 or more), race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic vs Black, non-Hispanic vs other), stage at diagnosis (I/II, vs III vs IV), and year of diagnosis. Finally, multivariable multinomial models were applied in subgroup analyses within each stage. Odds ratio (OR) along with 95% confidence interval (CI) from the multivariable models were presented as forest plots. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, INC., Cary, NC, USA) or R Version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria), All P-values were two-sided with P-values of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 248,634 patients with PC between 2004-2016. A total of 15,710 patients (6.3%) were defined as EOPC and 232,924 patients (93.6%) had AOPC. While the proportion of EOPC patients did not significantly change by year (range: 7.0-8.0%), the annual percentage of newly diagnosed AOPC patients did increase from 2004-2016 from 5.6% to 9.4%. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were more males compared to females in the EOPC cohort (56 versus 44%, p < 0.001). There were more non-white patients in the EOPC cohort compared to the AOPC cohort (36 versus 26%, p < 0.001). AOPC patients were more likely to have co-morbidities compared to EOPC (36 versus 21%, p < 0.001). Insurance status was notably different between the two cohorts, with a higher percentage of EOPC patients having Medicaid (18 versus 5%), no insurance (10 versus 2.9%), or private insurance (61 versus 30%) (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics according to Age Group

| Characteristic1 | Overall N = 248634 |

EOPC N = 15710 |

AOPC N = 232924 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 123920 (50%) | 6836 (44%) | 117084 (50%) |

| Male | 124714 (50%) | 8874 (56%) | 115840 (50%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 182169 (73%) | 10000 (64%) | 172169 (74%) |

| Black | 29927 (12%) | 2583 (16%) | 27344 (12%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6654 (2.7%) | 489 (3.1%) | 6165 (2.6%) |

| Hispanic | 27225 (11%) | 2394 (15%) | 24831 (11%) |

| Unknown | 935 (0.4%) | 59 (0.4%) | 876 (0.4%) |

| Others | 1724 (0.7%) | 185 (1.2%) | 1539 (0.7%) |

| Insurance Status | |||

| Private Insurance/Managed Care | 78926 (32%) | 9649 (61%) | 69277 (30%) |

| Medicaid | 14570 (5.9%) | 2829 (18%) | 11741 (5.0%) |

| Medicare | 138532 (56%) | 952 (6.1%) | 137580 (59%) |

| Other Government | 2688 (1.1%) | 202 (1.3%) | 2486 (1.1%) |

| Not Insured | 8281 (3.3%) | 1566 (10.0%) | 6715 (2.9%) |

| Insurance Status Unknown | 5637 (2.3%) | 512 (3.3%) | 5125 (2.2%) |

| Lymph Node Status * | |||

| Positive | 39212 (16%) | 3036 (19%) | 36176 (16%) |

| Negative | 23756 (9.6%) | 2219 (14%) | 21537 (9.2%) |

| Unknown | 6921 (2.8%) | 473 (3.0%) | 6448 (2.8%) |

| No Node Examined | 178745 (72%) | 9982 (64%) | 168763 (72%) |

| Stage | |||

| Stage 0 | 353 (0.1%) | 18 (0.1%) | 335 (0.1%) |

| Stage I | 19411 (7.8%) | 1259 (8.0%) | 18152 (7.8%) |

| Stage II | 64865 (26%) | 3989 (25%) | 60876 (26%) |

| Stage III | 26630 (11%) | 1776 (11%) | 24854 (11%) |

| Stage IV | 114575 (46%) | 7716 (49%) | 106859 (46%) |

| Unknown/NA | 22800 (9.2%) | 952 (6.1%) | 21848 (9.4%) |

| Total Charlson-Deyo Score | |||

| 0 | 162375 (65%) | 12451 (79%) | 149924 (64%) |

| 1 | 61178 (25%) | 2564 (16%) | 58614 (25%) |

| 2 | 25081 (10%) | 695 (4.4%) | 24386 (10%) |

| Distance between the patient's residence and the hospital that reported the case | |||

| 0-12.5 miles | 135380 (55%) | 7623 (49%) | 127757 (55%) |

| 12.5-50 miles | 74842 (30%) | 5186 (33%) | 69656 (30%) |

| 50+ miles | 37500 (15%) | 2827 (18%) | 34673 (15%) |

| Unknown | 912 | 74 | 838 |

| Community types | |||

| Metropolitan areas | 203516 (84%) | 12882 (84%) | 190634 (84%) |

| Urban | 34175 (14%) | 2158 (14%) | 32017 (14%) |

| Rural | 4499 (1.9%) | 254 (1.7%) | 4245 (1.9%) |

| Unknown | 6444 | 416 | 6028 |

Statistics presented: n (%)

Lymph node status based on pathology information only. Only available in surgical patients.

Treatment Utilization

When evaluating receipt of any treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation among 248,281 stage I to IV PC patients, EOPC patients were more likely to have received any treatment, compared to AOPC (81% versus 61%). Rates of all treatment modalities including chemotherapy only, surgery only, chemoradiation, and surgery with chemoradiation were higher in patients with EOPC. Notably rates of single modality radiation therapy were similar between EOPC and AOPC (1.2 versus 1.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics for Patients with Stage I-IV Disease

| Characteristic | Overall N = 248281 |

EOPC N = 156921 |

AOPC N = 2325891 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) | |||

| No/Unknown | 93882 (38%) | 2928 (19%) | 90954 (39%) |

| Yes | 154399 (62%) | 12764 (81%) | 141635 (61%) |

| Any surgery | |||

| No/Unknown | 193331 (78%) | 11013 (70%) | 182318 (78%) |

| Yes | 54950 (22%) | 4679 (30%) | 50271 (22%) |

| Any chemotherapy | |||

| No/Unknown | 115958 (47%) | 4594 (29%) | 111364 (48%) |

| Yes | 132323 (53%) | 11098 (71%) | 121225 (52%) |

| Any radiation | |||

| No/Unknown | 201891 (81%) | 11794 (75%) | 190097 (82%) |

| Yes | 46390 (19%) | 3898 (25%) | 42492 (18%) |

| Treatment utilization | |||

| No treatment | 93882 (38%) | 2928 (19%) | 90954 (39%) |

| Single chemotherapy | 72330 (29%) | 6002 (38%) | 66328 (29%) |

| Single radiation therapy | 3908 (1.6%) | 190 (1.2%) | 3718 (1.6%) |

| Single surgery | 17499 (7.0%) | 1417 (9.0%) | 16082 (6.9%) |

| No surgery, chemotherapy or radiation | 23211 (9.3%) | 1893 (12%) | 21318 (9.2%) |

| Surgery with chemotherapy +/− radiation | 37451 (15%) | 3262 (21%) | 34189 (15%) |

Statistics presented: n (%)

When evaluating treatment by stage, for patients with stage 1, 43% of EOPC patients received surgery alone compared to 15% of AOPC patients; 33% of EOPC patients received surgery and chemoradiation compared to 21% of AOPC patients; and 9.9% of EOPC patients received no treatment compared to 40% of AOPC patients. For stage 2, the rates of surgery alone were similar between EOPC and AOPC (16 vs 18%); however, EOPC patients were more likely to receive multimodal surgical treatment with chemotherapy or radiation (58 vs 44%). Notably, only 6.2% of EOPC patients received no treatment compared to 17% of AOPC patients for management of stage 2 disease. For stage 3, a similar proportion of EOPC and AOPC patients received chemotherapy alone (29 vs 28%), however, more EOPC patients received chemoradiation compared to AOPC patients (43 vs 33%). Again, rates of no treatment for stage 3 disease were higher for patients with AOPC, with 14% of EOPC patients receiving no treatment compared to 29% of AOPC patients. For stage 4, 62% of EOPC patients received chemotherapy alone compared to 45% of AOPC patients. 25% of EOPC patients received no treatment compared to 48% of AOPC patients.

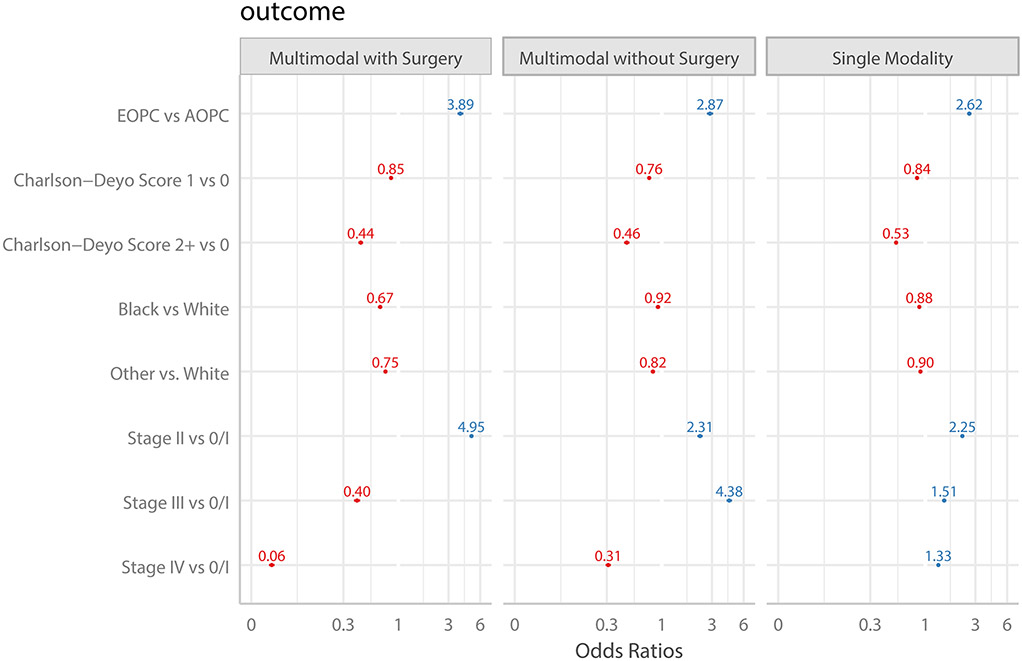

Multivariable analysis, adjusting for race, Charlson-Deyo score, year of diagnosis and stage, demonstrated that age < 50 years was associated with an approximately 3-4-fold increased odds of receiving treatment. For all stages, EOPC was independently associated with receipt of single modality, multimodal chemotherapeutic and multimodal surgical care. Across all stages, patients with comorbidities and non-white race were less likely to receive treatment. Patients with stage 2 or 3 disease were more likely to receive treatment compared to patients with stage 1 or 4 disease. (Figure 1) We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients receiving surgery with radiation therapy alone from the multinomial regression analysis, as this treatment grouping is not guideline supported. Among 225,481 stage I to IV patients, only 639 patients received surgery with radiation only (no chemotherapy). After excluding these patients, the odds ratio comparing surgery with chemotherapy only vs no treatment for EOPC versus AOPC was similar at 3.91 (95%CI: 3.66-4.16) to analysis with the entire cohort.

Figure 1. Forest Plot demonstrating Treatment Utilization compared to No Treatment.

Plot represents multivariable multinomial model adjusting for race/ethnicity, year of diagnosis, stage, and co-morbidity, specifically the adjusted odds of receiving the particular therapy versus no treatment. No treatment was used as reference category for all comparisons. Abbreviations include EOPC: Early-onset Pancreatic Cancer. AOPC: Average-age-onset Pancreatic Cancer.

Failure to Receive Treatment

Next, we characterized patients who did not receive any treatment for management of PC and compared these patients to those who had received treatment (Table 3). Patients with stage 0 disease were excluded from these comparative analyses. A total of 93,882 patients were identified who had not received any treatment for PC. The majority of untreated patients were female (53%), had a median age of 75 (range: 65-83), and had stage 4 (67%) disease at time of diagnosis. Most untreated patients were white (72%), although there was a statistically higher proportion of non-White patients in the no-treatment group compared to the treated cohort (p < 0.001). Medicare (69%) was the most common insurance in the untreated cohort, followed by private insurance (21%) and Medicaid (5.8%). A higher proportion of treated patients had private insurance compared to the untreated group (40 vs 21%, p < 0.001). In the untreated cohort, 60% of patients had a Charlson-Deyo score of 0 compared to 68% of patients in the treated cohort. Similarly, in the untreated cohort, 40% of patients had a Charlson-Deyo score 1 or greater, compared to only 31.8% of patients in the treated cohort (p < 0.001). Most untreated patients lived within 12.5 miles of the hospital (61%) and were evaluated in metropolitan areas (84%). In contrast, a higher proportion of treated patients lived between 12.5-50 miles (33 vs 26%) or farther than 50 miles (17 vs 13%) from the reporting hospital (p < 0.001). Notably, patients who received no treatment were more likely to have an income less than $40,227, compared to treated patients (22 vs 18%, p <0.001) and live in areas of lower educational attainment (21 vs 16%, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic Differences between Treated and Untreated Patients

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 248281 | No Treatment N = 938821 |

Treated N = 1543991 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68 (60, 77) | 75 (65, 83) | 65 (58, 73) | <0.001 |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 123746 (50%) | 49822 (53%) | 73924 (48%) | |

| Male | 124535 (50%) | 44060 (47%) | 80475 (52%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 181910 (74%) | 67008 (72%) | 114902 (75%) | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 29881 (12%) | 12165 (13%) | 17716 (12%) | |

| Hispanic | 27187 (11%) | 11075 (12%) | 16112 (10%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6647 (2.7%) | 2609 (2.8%) | 4038 (2.6%) | |

| Others | 1722 (0.7%) | 630 (0.7%) | 1092 (0.7%) | |

| Unknown | 934 | 395 | 539 | |

| Insurance Status | <0.001 | |||

| Private Insurance | 78813 (32%) | 18969 (21%) | 59844 (40%) | |

| Medicare | 138337 (57%) | 63337 (69%) | 75000 (50%) | |

| Medicaid | 14547 (6.0%) | 5376 (5.8%) | 9171 (6.1%) | |

| Not Insured | 8270 (3.4%) | 3465 (3.8%) | 4805 (3.2%) | |

| Other Government | 2687 (1.1%) | 937 (1.0%) | 1750 (1.2%) | |

| Unknown | 5627 | 1798 | 3829 | |

| Stage | <0.001 | |||

| Stage I | 19411 (8.6%) | 7454 (9.5%) | 11957 (8.1%) | |

| Stage II | 64865 (29%) | 10772 (14%) | 54093 (37%) | |

| Stage III | 26630 (12%) | 7373 (9.4%) | 19257 (13%) | |

| Stage IV | 114575 (51%) | 52803 (67%) | 61772 (42%) | |

| Unknown | 22800 | 15480 | 7320 | |

| Charlson-Deyo Score | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 162143 (65%) | 56638 (60%) | 105505 (68%) | |

| 1 | 61089 (25%) | 24178 (26%) | 36911 (24%) | |

| 2+ | 25049 (10%) | 13066 (14%) | 11983 (7.8%) | |

| Distance from Home to Hospital (miles) | <0.001 | |||

| 0-12.5 | 135226 (55%) | 57377 (61%) | 77849 (51%) | |

| 12.5-50 | 74717 (30%) | 24433 (26%) | 50284 (33%) | |

| 50+ | 37428 (15%) | 11723 (13%) | 25705 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 910 | 349 | 561 | |

| Income | <0.001 | |||

| Less than $40,227 | 48278 (20%) | 20739 (22%) | 27539 (18%) | |

| $40,227 - $50,353 | 54752 (22%) | 21477 (23%) | 33275 (22%) | |

| $50,354 - $63,332 | 56779 (23%) | 21278 (23%) | 35501 (23%) | |

| $63,333+ | 84610 (35%) | 28918 (31%) | 55692 (37%) | |

| Unknown | 3862 | 1470 | 2392 | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| 17.6%+ | 44482 (18%) | 19193 (21%) | 25289 (16%) | |

| 10.9%-17.5% | 64887 (26%) | 25719 (28%) | 39168 (25%) | |

| 6.3%-10.8% | 80333 (32%) | 29532 (32%) | 50801 (33%) | |

| Less than 6.3% | 57547 (23%) | 19054 (20%) | 38493 (25%) | |

| Unknown | 1032 | 384 | 648 |

Statistics presented: median (IQR); n (%)

Statistical tests performed: Wilcoxon rank-sum test; chi-square test of independence

We hypothesized that lack of treatment may be in part related to patient refusal of treatment. To assess patient preferences, we evaluated differences in treatment refusal between EOPC and AOPC patients. Across all stages, chemotherapy was recommended but refused by a patient, family member or guardian in 15% of AOPC patients, compared to 9.5% of EOPC patients. This difference remained significant when stratified by stage 0-2 (7.7 EOPC vs 14% AOPC) and stage 3-4 (11 EOPC vs 16% AOPC).

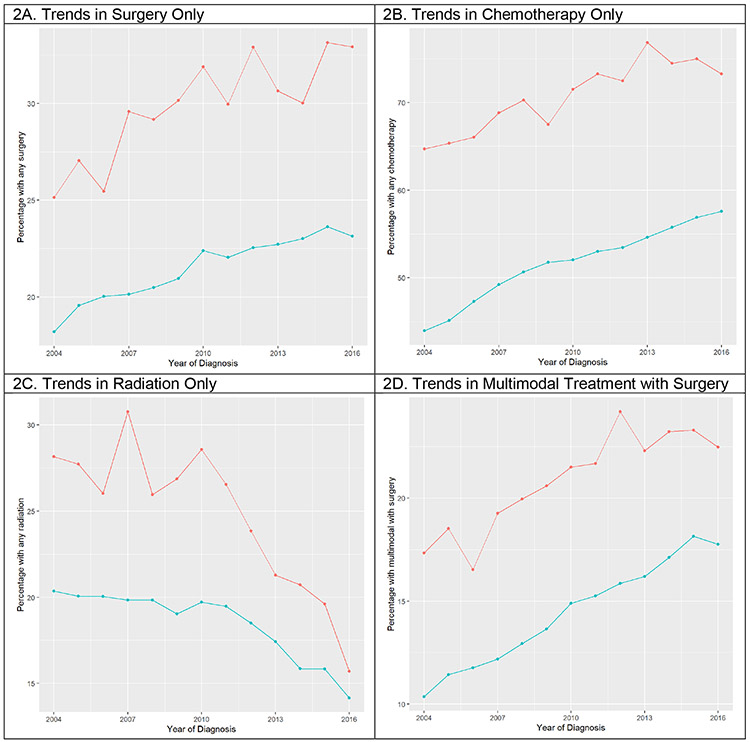

Trends in Treatment Utilization over Time

When assessing trends in treatment utilization over time, use of surgery and chemotherapy have increased for both EOPC and AOPC patients over the 12-year period, while use of radiation has markedly decreased. While use of multimodal therapy with surgery has significantly increased, use of multimodal therapy without surgery has decreased over time. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Treatment Utilization over Time.

Red lines represent EOPC patients and blue lines represent AOPC.

Impact on Survival

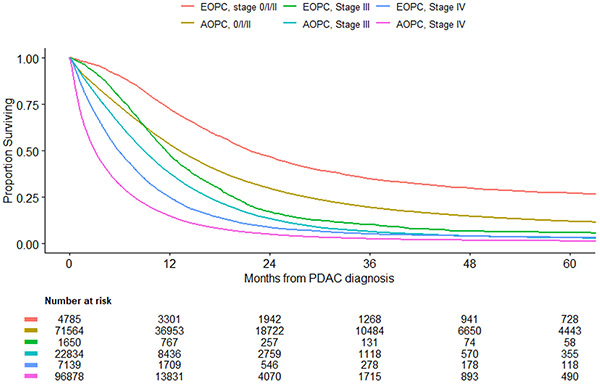

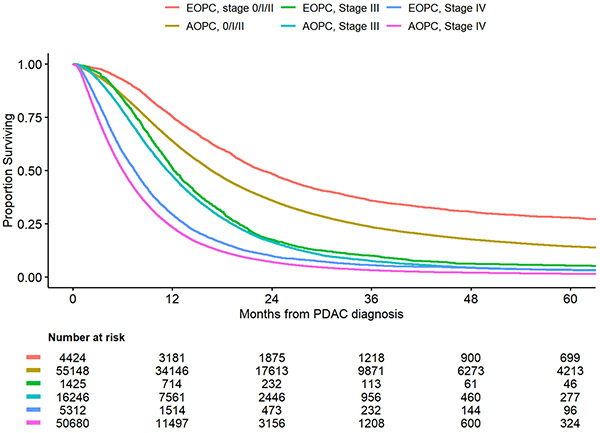

The median follow-up among survivors was about 30.2 months. For both treated and untreated patients, OS for patients with EOPC was better compared to AOPC across all stages of disease. (Figure 3a) For patients with stage 0-2 disease, 1-year overall survival for patients with EOPC was 72.4% (95%CI: 71.2%-73,7%) compared to 53.3% (95%CI: 52.9%-53.7%) for patients with AOPC. Similarly, for patients with stage 3 and 4 disease, 1-year overall survival was higher in the EOPC cohort compared to the AOPC cohort, 47.6 (95%CI: 45.1%-50.0%) vs 37.8% (95%CI: 37.1%-38.4%) and 24.8% (95%CI: 23.8%-25.8%) vs 14.8% (95%CI: 14.5%-14.9%), respectively. A sensitivity analysis, including only patients who received treatment, similarly demonstrated improved survival for patients with EOPC compared to AOPC, although the differences in survival were smaller in this subgroup. (Figure 3b)

Figure 3A.

Overall Survival by Age and Disease Stage for All Patients

Figure 3B.

Overall Survival by Age and Disease Stage for Treated Patients

Overall survival was further stratified by time period to determine if the availability and increased use of multiagent cytotoxic regimens after 2011 were associated with improved outcomes. One-year OS was higher for patients treated in 2012-2016, compared to those treated before 2012 (38 vs 30%), p < 0.0001, although the survival curves approached each other by 48 months. For patients who received any chemotherapy, the proportion of patients who received multiagent chemotherapy was higher in 2012-2016, compared to 2004-2011 (38575/59407, 64.9% vs 25602/67039, 38.9%). Similarly, the proportion of patients who received surgery and chemoradiation was higher in 2012-2016, compared to 2004-2011 (18234/59407, 30.6% vs 17755/67039, 26.4%).

Discussion

Treatment utilization has been associated with improved oncologic outcomes for patients with PC.17 This study sought to better characterize differences in treatment utilization for patients with EOPC compared to AOPC, to describe survival outcomes and to identify potential areas for improvement in treatment access and delivery. In this large, national cohort, we identified 248,634 patients with PC, of which 6.3% were EOPC patients. While there were notable differences in patient characteristics between EOPC and AOPC, including gender, race, and insurance coverage, after controlling for clinical variables, patients with EOPC received more multimodal treatment, across all stages, compared to AOPC. Notably, however, in both cohorts, a large minority of patients received no treatment, 19% and 39% for EOPC and AOPC, respectively. This finding suggests that while patients with EOPC may be more likely to receive standard-of-care, PC treatment compared to AOPC patients, there is significant room for improvement for access, delivery and utilization of best practice care for patients with PC at all ages.

The prevalence of EOPC ranges from 4.4 to 18% in the literature.5,8,12,16,20,21 In this series, 6.3% of patients were found to have EOPC, which is consistent with data from the SEER registry.14 Similar to prior reports, we found a higher proportion of males and fewer comorbidities in the EOPC cohort.5,12,14 Differences in gender and race between the two cohorts, with higher rates of Black and Hispanic patients in the EOPC group, may reflect differences in tumor biology or exposure to risk factors for PC, such as smoking, and have been previously reported. While some prior studies have suggested higher stage disease in the EOPC cohort, in our series, there was no difference in stage of disease between EOPC and AOPC.14 Screening strategies for unselected patients have not proven effective for PC,22 and thus most patients present late after development of symptoms; as such, it is feasible that there may be no major differences in clinical stage at diagnosis between younger and older patients with PC. Despite this, the slightly higher rate of positive lymph nodes in patients with EOPC may be in keeping with other work that hypothesizes that EOPC displays more aggressive tumor phenotype.6,23 Prior reports of differential germline alterations and higher rates of SMAD4 and PI3KCA mutations in EOPC patients, compared to AOPC, may further suggest a unique genetic landscape in these patients.6,11 Notably, KRAS mutations have been shown to be significantly less frequent in the EOPC compared to the AOPC cohort.6 Validation of these findings is not possible in the current study, due to limitations of the NCDB; however, as these factors may impact outcomes, further study regarding the role of germline and somatic testing for patients with PC is warranted.

In this series, differences in utilization, based on age, remained significant after adjustment for co-morbidities, stage and race, suggesting that age alone may play a significant role in referral and/or treatment patterns in current clinical practice. As current evidence-informed care recommends multimodality treatment with surgery and chemotherapy even for early-stage disease, this study illustrates that the treatment for PC remains underutilized. Patients with AOPC and early-stage disease are not receiving surgery. Chemotherapy is similarly not being utilized for higher stage disease for many AOPC patients as well as a large percentage of patients with EOPC.24

The variability in utilization based on age is likely multifactorial. First, younger patients may be more willing to pursue, tolerate, and receive therapy compared to older patients. Differences in insurance coverage may also impact treatment access. As patients with EOPC have more private insurance compared to AOPC patients, they may have improved access to high-quality cancer care. Similarly, physicians may consider more aggressive treatment options for younger patients, given a higher potential number of life years lost in this population. As EOPC patients have fewer co-morbidities, they may be fitter for higher intensity treatment with multi-agent cytotoxic regimens or major surgery, which may be contraindicated in older, more frail patients. Patients with EOPC may be more inclined to travel farther distances for care, as evidenced by the differences in distance between the patient’s residence and the reporting hospital between EOPC and AOPC patients in our study. Patients who travel to high-volume, highly specialized centers have improved access to complex multimodality cancer care and access to disease-specific expertise and clinical trials evaluating novel therapeutics. Finally, data from our institution suggest that EOPC may have a unique genomic profile, enriched for RAS wild-type tumors with targetable alterations (manuscript under review). These genomic differences between EOPC and AOPC may further lead to unique treatment recommendations, such as targeted therapy, and modulate outcomes, independent of the aforementioned factors.

While EOPC patients were more likely to receive treatment compared to AOPC, a striking number of patients in both groups received no treatment at all for management of PC. AOPC patients were more likely to receive no treatment; but surprisingly, nearly one fifth of EOPC patients also received no therapy. Such a finding reaffirms an ongoing failure to provide accessible care for patients with PC, which was first described in a study assessing surgical management of PC using the NCDB between 1995-2004.17 Explanations for failure to receive treatment are manifold. First, we observed that older patients were more likely to refuse recommended chemotherapy compared to younger patients, which may in part explain the higher rates of no treatment in the older PC group. When assessing additional characteristics of patients who did not receive treatment, there were a higher number of females, non-White patients, and fewer number of patients with private insurance, high income, or higher education. These patient characteristics may suggest socioeconomic or access barriers which prevent referral or patient presentation for evaluation. For EOPC patients, other factors such as lack of a flexible work schedule, childcare or household needs, or competing financial obligations may prevent prompt treatment. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment has been previously described, including substantial non-medical costs such as travel expenses or parking fees at treatment centers.25 To increase treatment receipt, attention to these non-medical costs and the associated economic and personal distress is critical. Prior literature has also suggested that Black patients were more likely to refuse surgery for PC compared to White patients.17,26 Notably, distance did not appear to be a significant factor, as most untreated patients lived within 12 miles of the hospital. Taken together, these findings suggest a multifactorial etiology for treatment refusal for both EOPC and AOPC patients, with significant room for improvement across all ages to maximize survival. Future studies are required to understand the contributing factors which lead to patient’s treatment refusal.

The observed utilization differences and patterns of treatment refusal between EOPC and AOPC patients are notable as they likely influence oncologic outcomes. A recent study, published by Ordonez et al. using the NCDB data from 2004-2013, observed that patients with EOPC have improved survival compared to AOPC patients.4 This study further explored predictors of survival for patients with EOPC, AOPC and a subgroup of patients who underwent resection, and concluded that receipt of any treatment was associated with improved survival. We similarly observed a clear survival benefit in the EOPC cohort for early stage (0-2) disease. When assessing only patients who received treatment, the convergence of survival curves between EOPC and AOPC in stage III and IV disease is not unexpected, given the high lethality of pancreatic cancer. Despite best treatments for high stage disease, outcomes remain dismal.

Unlike the Ordonez et al. manuscript and other studies that focus on survival, however, the current study focuses on the differences and trends in treatment patterns for patients with EOPC and AOPC and explores predictors of treatment receipt. While previously published studies have suggested that treatment is associated with improved survival, these studies fail to explore factors which may prevent receipt of or access to care. As survival is likely related to tumor biology, treatment efficacy, and availability of high-quality care, this study provides deeper investigation into the factors associated with survival in this cohort and provides a call-to-action for providers to address these disparities in care access. While the “ideal” treatment utilization for management of PC has not yet been characterized, this study provides evidence to suggest that patients with PC are likely being undertreated across all age ranges. Our results further introduce other modifiable factors, independent of age, which can be addressed by providers and healthcare systems to improve outcomes. It is imperative that the medical community appropriately identify patients for whom treatment is indicated, disseminate guideline endorsed practices, and improve care delivery and access to clinical trials.

With ongoing clinical research and the development of novel treatment modalities, the management of PC has changed over the last decade. Understanding how treatment utilization has evolved during this time can help identify trends in management and further highlight differences between EOPC and AOPC. In this series, rates of surgery alone and chemotherapy alone have increased over the 12-year study period for both EOPC and AOPC patients, while rates of radiation therapy have significantly decreased, which is in line with best practice recommendations. Notably, rates of multimodal therapy without surgery have decreased while surgical multimodal therapy has increased, suggesting more aggressive surgical interventions for patients with PC. Despite improvements in treatment delivery over time, however, there is persistent underutilization of treatment for patients with PC across all ages.

Our study has several critical limitations. First, this is an observational study using a large national retrospective cancer registry. As these data are episodic, granular evaluation of an individual patient’s treatment course and details regarding unique chemotherapy regimens are not available. Longitudinal data is also not provided in this dataset, particularly with respect to the change in use of neoadjuvant therapy over time. There also exists the potential for selection and other biases in treatment recommendations, which cannot be elicited. Use of a cancer registry further permits the possibility of under-reporting or missing values, which may confound trends identified. This missingness may include treatment, patient, or other characteristics. As the NCDB does not include genetic information, we cannot comment on how germline or somatic information affected treatment choice of therapy or overall management. As patients with EOPC appear to have a unique genetic profile, consideration of somatic and germline mutational data is key in prognostication and treatment selection. Further, data on performance status, frailty or physiologic age are not available in the NCDB. Finally, the duration and activity of chemotherapeutic treatment are not provided in the NCDB. This limits ability to comment of the efficacy of individual treatments.

Differing age cutoffs have been used in the literature to define EOPC. In part due to these variable definitions of EOPC, reported outcomes are heterogenous and difficult to compare. The justification for the age cutoff of 50 in this study was two-fold. First, based on prior literature on EOPC, this appears to be within the range of ages used to define EOPC versus AOPC. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the relationship between treatment and age (results not shown). For all four modeled outcomes, including no treatment, multimodal treatment with and without surgery, and single modality treatment, we observed an inflection point around 50 years of age. Together, these findings support our utilization of age 50 as a cutoff for EOPC and AOPC in this study. To improve comparability between studies evaluating EOPC, consideration of standardization of the definition to EOPC as age < 50 years and AOPC as age ≥ 50 years is warranted.

The association between treatment utilization and quality of care has been well established. Understanding utilization patterns in order to identify gaps in care is a critical first step to guide quality improvement strategies. We report that patients with EOPC are more likely to receive standard of care, multimodal treatment, while patients with AOPC appear to be undertreated for PC. Cancer-directed treatment for PC patients of all age groups is underutilized. Thus, there remains a major opportunity to advance outcomes in PC by improving access and delivery of high-quality evidence-informed care for all patients, irrespective of age.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization with any financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript.

Disclosure: The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The CoC's NCDB and the hospitals participating in the CoC NCDB are the source of the de-identified data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

References

- 1.Key Statistics for Pancreatic Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Updated 3/10/2020. Accessed.

- 2.Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(3):e137–e147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muniraj T, Jamidar PA, Aslanian HR. Pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive review and update. Dis Mon. 2013;59(11):368–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ordonez JE, Hester CA, Zhu H, et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Outcomes of Early-Onset Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(6):1997–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ntala C, Debernardi S, Feakins RM, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T. Demographic, clinical, and pathological features of early onset pancreatic cancer patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Aharon I, Elkabets M, Pelossof R, et al. Genomic Landscape of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in Younger versus Older Patients: Does Age Matter? Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(7):2185–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McWilliams RR, Maisonneuve P, Bamlet WR, et al. Risk Factors for Early-Onset and Very-Early-Onset Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (PanC4) Analysis. Pancreas. 2016;45(2):311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piciucchi M, Capurso G, Valente R, et al. Early onset pancreatic cancer: risk factors, presentation and outcome. Pancreatology. 2015;15(2):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lohr JM, Lowenfels AB. Early onset pancreatic cancer: evidence of a major role for smoking and genetic factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(9):1894–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campa D, Gentiluomo M, Obazee O, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies an early onset pancreatic cancer risk locus. Int J Cancer. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varghese Aea. Abstract 774: Young-onset pancreas cancer (PC) in patients less than or equal to 50 years old at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK): Descriptors, genomics, and outcomes. In: Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy A, Capanu M, Allen P, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a young patient population--12-year experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(1):8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, Edil BH, Cameron JL, et al. Young patients undergoing resection of pancreatic cancer fare better than their older counterparts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(2):339–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansari D, Althini C, Ohlsson H, Andersson R. Early-onset pancreatic cancer: a population-based study using the SEER registry. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404(5):565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James TA, Sheldon DG, Rajput A, et al. Risk factors associated with earlier age of onset in familial pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2722–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tingstedt B, Weitkamper C, Andersson R. Early onset pancreatic cancer: a controlled trial. Ann Gastroenterol. 2011;24(3):206–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246(2):173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Data Base Participant User File (PUF) Data Dictionary. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/puf_data_dictionary.ashx. Accessed2020.

- 19.Ripley WNVBD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4 ed: Springer-Verlag New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin JC, Chan DC, Chen PJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of early onset pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a medical center experience and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2011;40(4):638–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raissouni S, Rais G, Mrabti H, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in young adults in a moroccan population. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43(4):607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Force USPST, Owens DK, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for Pancreatic Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322(5):438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergmann F, Aulmann S, Wente MN, et al. Molecular characterisation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in patients under 40. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(6):580–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (Version 1.2020). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee A, Shah K, Chino F. Assessment of Parking Fees at National Cancer Institute-Designated Cancer Treatment Centers. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(8):1295–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eloubeidi MA, Desmond RA, Wilcox CM, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. Am J Surg. 2006;192(3):322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]