Abstract

Background

It has been claimed that functional somatic syndromes share a common etiology. This prospective population-based study assessed whether the same variables predict new onsets of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM).

Methods

The study included 152 180 adults in the Dutch Lifelines study who reported the presence/absence of relevant syndromes at baseline and follow-up. They were screened at baseline for physical and psychological disorders, socio-demographic, psycho-social and behavioral variables. At follow-up (mean 2.4 years) new onsets of each syndrome were identified by self-report. We performed separate analyses for the three syndromes including participants free of the relevant syndrome or its key symptom at baseline. LASSO logistic regressions were applied to identify which of the 102 baseline variables predicted new onsets of each syndrome.

Results

There were 1595 (1.2%), 296 (0.2%) and 692 (0.5%) new onsets of IBS, CFS, and FM, respectively. LASSO logistic regression selected 26, 7 and 19 predictors for IBS, CFS and FM, respectively. Four predictors were shared by all three syndromes, four predicted IBS and FM and two predicted IBS and CFS but 28 predictors were specific to a single syndrome. CFS was more distinct from IBS and FM, which predicted each other.

Conclusions

Syndrome-specific predictors were more common than shared ones and these predictors might form a better starting point to unravel the heterogeneous etiologies of these syndromes than the current approach based on symptom patterns. The close relationship between IBS and FM is striking and requires further research.

Key words: Chronic fatigue syndrome, epidemiology, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, risk factors

Introduction

The functional somatic syndromes (FSS) comprise clusters of persistent somatic (bodily) symptoms, which may cause considerable impairment and are associated with increased mortality, but whose etiology is not fully understood, (Hanlon et al., 2018; Joustra, Janssens, Bültmann, & Rosmalen, 2015; Macfarlane, Barnish, & Jones, 2017; Roberts, Wessely, Chalder, Chang, & Hotopf, 2016; The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018). Common examples are irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM). The etiology of these syndromes is not entirely clear but they are associated with multiple biological, psychological and social factors (Enck et al., 2016; Häuser & Fitzcharles, 2018; Holgate, Komaroff, Mangan, & Wessely, 2011). It has been suggested that IBS, CFS and FM share a similar etiology because of similarity of symptoms, overlap of case definitions and associations with female sex, anxiety, depression and childhood abuse (Wessely, Nimnuan, & Sharpe, 1999). Others have argued that syndrome-specific mechanisms must be involved as no single pathophysiological mechanism could underlie the different key symptoms of IBS, CFS and FM and there is evidence of specificity of triggering infections (Moss-Morris & Spence, 2006). Little progress has been made in resolving these conflicting views over the last 20 years because of the lack of prospective, population-based studies assessing more than one syndrome.

Previous prospective population-based studies have shown that female sex, anxiety/depression, general medical disorders and frequent medical consultations have emerged as risk factors for each of the three syndromes (IBS, CFS and FM); sleep and pain disorders were risk factors for IBS and FM (Table 1) (Chang et al., 2015; Creed, 2019; Creed, 2020; Donnachie, Schneider, Mehring, & Enck, 2018; Sibelli et al., 2016). On the other hand, younger age predicts IBS while older age predicts FM. Infection is more clearly established as a causal factor in IBS and CFS than in FM; the latter is predicted by pre-existing severe regional or chronic pain (Chang et al., 2015; Creed, 2019; Creed, 2020; Donnachie et al., 2018; Hulme, Hudson, Rojczyk, Little, & Moss-Morris, 2017). Smoking and raised body mass index are risk factors for FM but the evidence is conflicting with regard to IBS and CFS (Creed, 2019, 2020). This mixed picture suggests there may be both shared and syndrome-specific etiological pathways into these disorders. Previous relevant studies have used different diagnostic criteria, a limited number of potential risk factors and rarely included more than one functional somatic syndrome making comparisons difficult. The conflicting views on shared v. syndrome-specific etiological risk factors can only be resolved when consistent measures of all possibly relevant predictor variables are applied to all three syndromes within the same sample.

Table 1.

Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia shown by the number of times each has been reported in previous studies, with most frequent at the top (Creed, 2019, 2020)

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Chronic fatigue syndrome | Fibromyalgia/Chronic widespread pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 19 | Female | 7 | Female | 12 |

| Anxiety & depression | 16 | Mid-life/Older | 8 | Other medical disorders | 20 |

| G-I disorders | 13 | Anxiety/depression | 8 | Older age | 11 |

| Gastroenteritis | 12 | Other medical disorders | 10 | Prior pain/ musculo-skeletal disorders | 13 |

| Younger age | 11 | Glandular fever | 4 | Anxiety/depression | 11 |

| Non-GI disorders | 10 | Fatigue | 4 | Sleep disorder | 13 |

| Older age | 9 | Gastroenteritis | 3 | Raised BMI | 7 |

| Pain disorders | 9 | Frequent consultations | 3 | Smoking | 8 |

| Frequent consultations | 9 | High SES | 2 | Illness behavior | 5 |

| Life events/stress | 6 | Negative health perception | 2 | ||

| Sleep disorders. | 5 |

The current study is the first that aimed to identify the shared and syndrome-specific predictors for new onsets of IBS, CFS and FM in a single prospective population-based study that includes a wide range of predictor variables measured prior to the onset of the syndrome.

Methods

Study design and participants

The data used in this study came from the LifeLines. Lifelines is a multi-disciplinary prospective population-based cohort study examining in a unique three-generation design the health and health-related behaviors of 167 729 persons living in the North of The Netherlands. It employs a broad range of investigative procedures in assessing the biomedical, socio-demographic, behavioral, physical and psychological factors which contribute to the health and disease of the general population, with a special focus on multi-morbidity and complex genetics. A brief summary of the study design is provided below and details can be found elsewhere (Scholtens et al., 2015). The participants were recruited between 2006 and 2013. Two-thirds (562/812) of the general practitioners in this area invited their registered patients between age 25 and 50 years to join the project. In addition, family members of the participants were recruited and additional participants were recruited via online self-registration. In total, 53% of the participants were enrolled via their general practitioner, 32% were family members and 14% registered online (Scholtens et al., 2015). Persons with severe psychiatric or physical illness, those unable to visit their general practitioner and/or not fluent in the Dutch language were excluded from the study. The sample population of the Lifelines study is broadly representative of the total Dutch population (Klijs et al., 2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen.

After participants signed informed consent, they received a baseline questionnaire and were invited to a health assessment at the Lifelines research site. The baseline questionnaire which included demographics, previous and current specified diseases (including IBS, CFS, FM), medication use, healthcare use, health-related quality of life (Hays & Morales, 2001) and somatization (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974). At the Lifelines research site, a trained research nurse performed a physical examination and administered the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998). Two follow-up questionnaires, which included many of the baseline items, were administered subsequently to all participants at about 17 months and 29 months after the baseline. The data analyzed in this project all came from the questionnaire except BMI and psychiatric diagnoses from the MINI.

The present study included respondents who were 18 years and older at the baseline measurement (N = 152 180) and the first and the second follow-up questionnaires were used to identify the self-reported new onsets of IBS, CFS and FM since baseline. Because we were interested in incident cases, we excluded respondents who reported at baseline that they had ever had a diagnosis of IBS, FM or CFS or who currently reported any of the key symptoms of these syndromes. The latter group was excluded because previous studies have identified the key symptoms as the strongest predictors of FSS, suggesting that early or undiagnosed cases are responsible for these associations (Hamilton, Gallagher, Thomas, & White, 2009). To avoid this problem, we excluded from the IBS analysis participants who, at baseline, reported on the Symptom Check List-90 SOM questionnaire (Derogatis et al., 1974) that they experienced nausea or upset stomach ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much.’ Those feeling tired ‘most or all of the time’ during the past 4 weeks [RAND item (Hays & Morales, 2001)] were excluded from the CFS analysis and those reporting painful muscles ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ [SCL-90 item (Derogatis et al., 1974)] were excluded from the FM analysis. The resulting numbers included in each analysis are shown in Table 2(A). Each of the resulting samples was randomly divided into a training set (80% of the sample) and a test set (20% of the sample) (Table 2 (B)).

Table 2.

Derivation of the samples of new onset IBS, CFS and FM

| (A) | IBS | CFS | FM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size of Lifelines (age ⩾18) | 152 180 | 152 180 | 152 180 |

| Lifetime diagnosis of the syndrome at baselinea | 14 365 | 1983 | 4710 |

| Participants with missing data on lifetime diagnosis at baseline | 175 | 175 | 175 |

| Participants without lifetime diagnosis of the syndrome but with marked key | 1778 | 10 123 | 7387 |

| Symptom at baseline | |||

| Sample included in the analysis | 135 862 | 139 899 | 139 908 |

| Female (%) | 55 | 57 | 57 |

| Mean baseline age (s.d.) | 44.8 (13.1) | 44.9 (13.2) | 44.5 (13.2) |

| Number of new onsets | 1595 | 296 | 692 |

| Female % in new onset group | 77 | 56 | 89 |

| Mean baseline age in the onset group (s.d.) | 44.1 (13.9) | 48.0 (13.0) | 46.3 (11.7) |

Subjects who reported lifetime diagnosis of the corresponding disorder.

Measures

Predictors

The candidate baseline predictors for new onset of the relevant syndromes were chosen from those associated with IBS, CFS and/or FM in the existing literature; these have been thoroughly reviewed and the results are shown in Table 1 (Creed, 2019, 2020). In total, 102 variables were chosen from the Lifelines questionnaire as candidate predictors, which are grouped in the online Supplementary Table S1 as follows: socio-demographic variables, general medical conditions, over the counter and prescribed medications (using ATC code), healthcare use, health behaviors and related variables, psychosocial variables and psychiatric disorders. The complete list of included candidate predictors is provided in online Supplementary Table S1.

The Lifelines questionnaire asks participants whether they have had each of 42 medical disorders. For the purpose of analysis, these were reduced to 20 (online Supplementary Table S1). Participants were also asked about any (prescription) medication they used at baseline. While the onset of the syndromes was assessed at the follow-up assessments, the medication use was assessed at the baseline. Only drug use recorded at baseline was used in the analysis. The ATC codes and generic names of these medications were recorded, and medications were grouped using the ATC code 3rd level resulting in 27 clusters that were used in the analyses. Healthcare use and health behaviors were recorded using the questions on the Lifelines database (https://catalogue.lifelines.nl/). Personality variables were measured using the NEO personality questionnaire (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Current health status was assessed using the RAND 36-Item Health Survey General Health scale (Hays & Morales, 2001) and the somatization scale of the Symptom Check List-90 SOM questionnaire (Derogatis et al., 1974).

Life events were measured using the Long-term Difficulties Inventory (LDI) and the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) (Brugha & Cragg, 1990; Rosmalen, Bos, & De Jonge, 2012). The events and difficulties were split into events involving illness-related and non-illness-related experiences, as we wished to assess separately the experience of recent illness and stress arising from non-illness life events and chronic (social) difficulties. Psychiatric disorders were measured using the MINI interview (Sheehan et al., 1998).

Outcomes

Each analysis used the onset of one syndrome (IBS, CFS or FM) during the follow-up period as an outcome. For each syndrome, a new onset was considered present if a participant reported the development of the syndrome at one or both of the two follow-up assessments.

Missing data handling

Missing values occurred in 2.4% of the data and were imputed 20 times, using the Amelia II R-package (Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2011) running in RStudio version 1.1.383. If missing values were present on aggregate sum scores (e.g. questionnaire scores), the data were imputed on the disaggregated item data to achieve imputed values of optimal quality (Eekhout et al., 2014).

Statistical analyses

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) logistic regression was applied to identify the most important predictors for each of the syndromes. LASSO is a statistical technique that has specifically been developed to select predictors from a large set of variables while effectively improving the predictive accuracy and interpretability of the selected set of predictors (Tibshirani, 1996). Importantly, the method allows for the estimation of prediction models based on large numbers of candidate predictors, while avoiding overfitting to the study data by applying a penalization/shrinkage process (Tibshirani, 1996). This process consists of constraining the sum of the absolute values of the regression coefficients, which forces the coefficients of unimportant predictors to zero while coefficients of important predictors are regularized upward. LASSO was chosen in favor of other penalizing/shrinkage methods since it can handle highly correlated predictors and will yield a parsimonious model including only the most important predictors for an outcome, which is important for interpretability and potential generalizability.

In the current study, we implemented LASSO for logistic regression, using the ‘glmnet’ R-package (Friedman, Hastie, & Tibshirani, 2010) for each of the imputed training sets. The 102 predictors were included in each of the LASSO logistic regression analyses to predict the onset of IBS, FM and CFS, respectively. Standardized predictors were used to enable comparison between different predictors' effects. During model estimation, the optimal LASSO model was selected based on the lowest prediction error (squared error deviance) in 10-fold cross-validation.

After estimation of the penalized beta-coefficients for a given outcome in the training set, the model's predictive performance was evaluated in the test set to check replicability and potential model overfitting. Because the numbers of new onset cases for each syndrome were extremely low (<2%) compared to the non-onset cases, the area under the recall-precision curve was used as a measure of prediction accuracy. This method was more suitable than a traditional area under the receiver operator curve, which tends to be biased in the case of data with low incidence outcomes (Davis & Goadrich, 2006). For this, the ‘PRROC’ R-package (Grau, Grosse, & Keilwagen, 2015) was used.

The mean and standard deviations of the estimated coefficients were calculated to verify the frequencies of the coefficients receiving non-zero values and the stability of the estimated coefficients across 20 imputed datasets. In this study, we selected penalized beta coefficients that received non-zero coefficients in more than 17/20 (85%) of the imputed datasets to retain the most stable predictors.

Results

Descriptive information

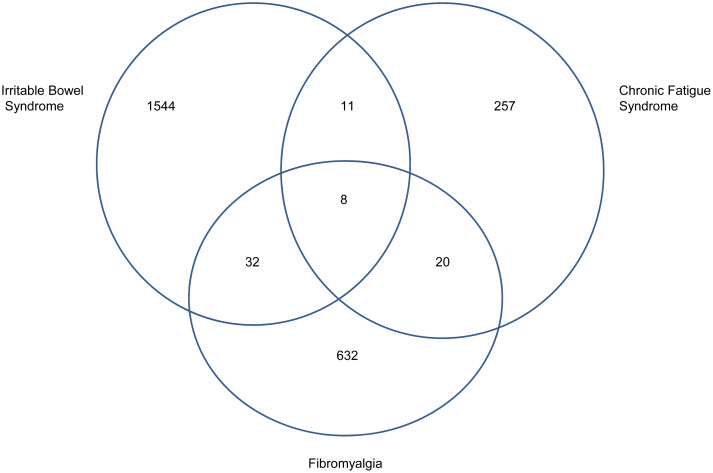

Table 2(A) shows the numbers of participants excluded because they already had a prior diagnosis of the relevant syndrome, or they had missing data on baseline diagnosis, or they reported marked symptoms of that syndrome. Since this was different for each syndrome, Table 2(B) shows the size of each of the datasets used in the analyses; they were comparable in terms of sex ratio and baseline age. The numbers of new onsets are shown in Table 2(A); these translate into the following incidence rates: 48.9, 8.8 and 20.6 per 10 000 person years for IBS, CFS and FM, respectively. Few participants developed more than one syndrome during the 2.4 years follow up (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram to show overlap of new onset of multiple syndromes.

Predictors of IBS, CFS and FM onset

We identified 26, 7 and 19 stable predictors for the onset of IBS, CFS and FM, respectively. All estimated coefficients are presented in the online Supplementary Table S1, and the penalized coefficients with nonzero values in more than 17/20 (85%) imputed datasets are presented in Table 3. Standard deviations of the coefficients across the 20 imputed datasets were smaller than 0.25, indicating high stability of the estimates across 20 imputed datasets. The mean AUC of the recall-precision curve across 20 imputed datasets for IBS, CFS and FM were 0.03, 0.01 and 0.02, respectively, indicating low predictive accuracy for all syndromes, reflecting either the low incidence rates in this large population or the complexity of the onset mechanisms.

Table 3.

Odds ratios of predictors of IBS, CFS and FM obtained from a LASSO penalized logistic regression analysis

| Predictors | IBS | CFS | FM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(β) | %a | OR(β) | %a | OR(β) | %a | |

| General information predictors | ||||||

| Sex (female) | 1.88 | 100 | 3.16 | 100 | ||

| Work status (student)b | 1.12 | 95 | ||||

| Work status (paid work)b | 0.90 | 100 | ||||

| Health predictors | ||||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome | 1.77 | 100 | ||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of fibromyalgia | 1.49 | 100 | ||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of gastrointestinal disordersc | 1.23 | 100 | 1.15 | 95 | ||

| Lifetime diagnosis of kidney diseasesd | 1.17 | 100 | ||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorderse | 1.75 | 100 | ||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disordersf | 1.11 | 100 | ||||

| Lifetime diagnosis of high cholesterol | 1.19 | 85 | ||||

| Having allergyg | 1.28 | 100 | 1.06 | 85 | ||

| Body mass index | 0.98 | 100 | 1.01 | 95 | ||

| Medication use (ATC code) | ||||||

| Drugs for peptic ulcer and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (A02B) | 1.95 | 95 | ||||

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders (A03A) | 5.21 | 100 | ||||

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders/propulsives (A03F) | 1.34 | 90 | ||||

| Alimentary tract and metabolism; drugs for constipation (A06A) | 2.92 | 100 | ||||

| Genito urinary system and sex hormones/sex hormones and modulators of the genital system/ hormonal contraceptives for systemic use (G03A) | 0.77 | 85 | ||||

| Genito urinary system and sex hormones/sex hormones and modulators of the genital system/Antiandrogens (G03H) | 1.67 | 100 | ||||

| Systemic hormonal preparations, excl. sex hormones and insulins, thyroid therapy, thyroid preparations (H03A) | 1.15 | 90 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal system/anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products, non-steroids (M01A) | 1.09 | 90 | ||||

| Respiratory system/nasal preparations/decongestants and other nasal preparations for topical use (R01A) | 1.30 | 90 | ||||

| Respiratory system/drugs for obstructive airway diseases/adrenergics, inhalants (R03A) | 1.19 | 100 | ||||

| Sensory organs/Ophthalmologicals/other ophthalmologicals (S01X) | 1.36 | 100 | ||||

| Healthcare use | ||||||

| No contact with GP nor specialists in the past 5 years | 1.16 | 85 | ||||

| Contact with GP more than 4 times per year in the past 5 years | 1.35 | 100 | ||||

| I have/had contact with several specialists in the past 5 years | 1.13 | 85 | ||||

| Lifestyle and environment variables | ||||||

| Smoke now or in the past month? | 0.91 | 95 | ||||

| Sleep disturbance | 1.04 | 100 | 1.14 | 100 | 1.08 | 100 |

| Low alcohol consumption | 1.05 | 95 | 1.12 | 95 | ||

| Psychosocial parameters | ||||||

| Serious illness, injury or assault to subject in the last past year according to the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) | 0.76 | 90 | ||||

| Serious life-events in the past year according to the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) | 1.03 | 95 | 1.03 | 90 | ||

| Experience difficulties and stress related to your health (e.g. regularly ill, long-term disorders) in the past year according to the Long-term Difficulties Inventory (LDI) | 1.21 | 100 | 1.35 | 100 | 1.13 | 100 |

| Long-term difficulties in the past year according to the Long-term Difficulties Inventory (LDI) | 1.01 | 90 | ||||

| Self-discipline (NEO) | 1.02 | 90 | ||||

| Somatization scale sum score (SCL-90) | 1.03 | 100 | 1.02 | 100 | 1.04 | 100 |

| Health-related quality of life scale scores (RAND) | ||||||

| Bodily pain | 0.99 | 100 | ||||

| General Healthh | 0.99 | 100 | 0.99 | 100 | 0.99 | 85 |

| Vitality | 0.98 | 100 | ||||

Frequency of the predictor being estimated with non-zero β across 20 imputed datasets.

Not working as a reference.

Including Stomach ulcer, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, celiac disease, gallstones.

Including kidney stones, chronic cystitis, incontinence.

Including osteoarthritis, joint inflammation, osteoporosis, back or neck hernia, RSI, hip fracture, fractures other than a hip fracture.

Including burnout, depression, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar, schizophrenia, eating disorder, obsessive/compulsive, ADHD, dizziness with falling.

Including dust, animals, pollen, foods, medication, contact allergy and insects.

Measured using the items of the RAND −36 General Health scale.

Shared predictors of IBS, CFS and FM onset

Four predictors were shared by all three syndromes. Disturbed sleep (PSQI score), greater stress related to chronic ill health, higher somatization score (SCL-90 SOM) and poor perception of general health (RAND scale) were associated with an increased probability of syndrome onset. However, with the exception of stress related to chronic ill health, the coefficients for these predictors were rather small. Four predictors were shared by the IBS and FM onset groups: female sex, allergy, gastrointestinal disorders and low alcohol consumption. BMI also predicted both IBS and FM onset, but the effects were in the opposite direction, with higher BMI predicting lower onset probability for IBS and higher onset probability for FM. One predictor was shared by CFS and IBS: high negative life events score (not involving serious illness, injury or assault to the participant) in the year prior to baseline.

Syndrome-specific predictors of IBS, CFS and FM onset

For IBS onset, 16 syndrome-specific predictors were observed, including a lifetime diagnosis of FM, taking medications for gastrointestinal problems, antiandrogens and frequent contact with the GP. Additional smaller positive associations were medication for obstructive airway diseases, and lifetime diagnoses of kidney disease and psychiatric disorders. Use of hormonal contraceptives predicted a lower risk of the onset of IBS.

For CFS onset, there were only two syndrome-specific predictors: high cholesterol showed the largest effect and reduced vitality (RAND) showed a small association. For FM onset, syndrome-specific predictors with the strongest association were prior IBS, prior musculoskeletal disorders and taking medication for peptic ulcer or gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Additional predictors were the use of ophthalmological treatments (artificial tears), nasal decongestants and thyroid therapy. Having had no contacts with a GP or specialist for 5 years predicted FM onset whereas a serious illness, injury or assault in the year prior to baseline was associated with decreased onset probability of FM.

Discussion

Two important findings emerged from this first population-based study identifying the predictors of new onsets of IBS, CFS and FM. First, we found that three-quarters of predictors were syndrome-specific and only a quarter was shared by two or more syndromes. Second, we found that baseline IBS predicts new onset FM and vice versa but CFS was not predicted by either and was not itself a predictor of IBS or FM onset.

This study has strengths and limitations that must be recognized. The strengths include the large size of the population-based cohort followed over 2.4 years. We included three functional somatic syndromes, a much wider range of relevant potential predictors than any comparable study, and we excluded participants who might have had an early or undiagnosed syndrome at baseline. Furthermore, we used a sophisticated statistical analysis to avoid over fitting and this enabled us to handle strongly interdependent data. We enhanced the models' predictive performance by estimating the coefficients in training sets and estimating predictive accuracy in test sets.

The main limitation was the reliance on self-report for our main outcome. We cannot be certain that our new onset cases did not include people whose symptoms were caused by an unrecognized general medical disorder or participants who did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria. Unfortunately, no gold standard exists for the FSS diagnoses and self-reported diagnoses may be unreliable. For example in a population-based study, most participants reporting a clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria (Walitt, Katz, Bergman, & Wolfe, 2016). Asking whether a doctor had made the diagnosis may not improve validity as self-report of physician diagnosis does not appear to identify most people with CFS, FM and IBS (Warren & Clauw, 2012). Even clinician-based fibromyalgia diagnoses in a university clinic did not correspond to diagnosis according to the criteria in one study (Wolfe et al., 2019). For CFS, many different diagnostic criteria exist and there is little consensus on which is preferred (Haney et al., 2015). Another limitation is that, for the sake of interpretability and comparability, we have used broader categories as predictors, rather than specific medication use or disorders.

As this project was based on the large Lifelines database, we had to rely on the way these diagnoses had been recorded on the Lifelines questionnaire. It would have been preferable to use standardized diagnostic criteria of IBS, CFS and Fibromyalgia but this was not possible since these were not included in the LifeLines follow-up questionnaires available to us; we did not have access to GP records. This disadvantage has to be balanced against the advantages of much more extensive medical data, including medication, than most population-based questionnaire studies and we were able to use the widest range of predictors of any study of this type. Self-report diagnosis of all three syndromes has been used in previous studies, notably birth cohort studies; they have shown moderate agreement with medical records (Creed, 2019, 2020; Ehlin, Montgomery, Ekbom, Pounder, & Wakefield, 2003; Marrie et al., 2012). In addition, this limitation applies across all three disorders, and the main aim of this paper was to compare predictors between disorders, which is potentially less influenced by this limitation. The low number of new onsets made it difficult to achieve accurate prediction for the three syndromes, especially CFS; a younger sample might have been preferable as the first onset of CFS is usually early in adult life (Bakken et al., 2014). We had no measure of childhood adversities or psychological trauma which has been mentioned in previous reports as a possible predictor. The Lifelines database has very few emotional, cognitive and behavioral items, which might be regarded as specifically relevant to these syndromes so this project cannot compare the cognitive-behavioral model of FSS.

The interpretation of the results is complex. We performed a LASSO regression as we wished to include many potentially highly correlated predictors in one model, which would have led to multicollinearity and thus a violation of the assumptions of classical regression analyses. In LASSO regression, if a variable does not contribute to the predictive value of the model, it is forced (penalized) to zero. On the other hand, variables that have predictive value are inflated. This aspect of LASSO allowed us to include many predictors in a model and still obtain interpretable results in terms of comparing predictors across diseases. Since all predictors were tested in exactly the same way we would have expected far greater similarity of predictors across the three syndromes if they were all driven by the same underlying illness process(es). The method is not well suited to interpreting the association between individual variables and a particular syndrome and this is a limitation of our method.

Incidence rates were comparable to those recorded in the systematic reviews, which showed median incidence rates of physician-diagnosed IBS, CFS and FM as 38.5, 2.5 and 24 per 10 000 person-years, respectively. Our higher rate for CFS may reflect the use of self-reported syndromes rather than physician diagnosis but the difference could also reflect the great variability in CFS diagnostic criteria (Haney et al., 2015; Jason et al., 1999). We found the predictors of IBS mirrored those in the literature (see Table 1); this was largely so for FM but not for CFS.

There are several reasons why we found so few predictors of CFS; the low number of participants with new onset CFS may be the main reason but, in addition, the lack of appropriate emotional, cognitive and behavioral measures relevant to CFS is important. Risk factors for CFS have been shown to differ when there is a concurrent psychiatric disorder and it is possible that by excluding participants with marked fatigue at baseline, we may have excluded participants with a psychiatric disorder, a common cause of fatigue (Harvey, Wessely, Kuh, & Hotopf, 2009). We needed to exclude participants with fatigue at baseline, however, to exclude early or undiagnosed CFS from our sample of new onsets. Others have found that the strongest predictors of CFS and IBS are fatigue and abdominal pain, respectively but this suggests that early or undiagnosed cases may have been included in their sample (Hamilton et al., 2009).

The shared predictors of IBS and FM are remarkable since the diagnostic criteria of these syndromes do not overlap, unlike those of FM and CFS. These shared predictors have not been demonstrated in previous population-based studies. Not only were IBS and FM mutual risk factors for each other, unlike CFS, but gastrointestinal diseases and their treatment were predictors of both IBS and FM. The mechanisms underlying this finding are not clear, but these two syndromes shared a cluster of predictors related to allergy (including having an allergy for both IBS and FM, medication for obstructive airway diseases for IBS, and nasal decongestants for FM). This is interesting, given recent findings suggesting local mast cell activation in IBS (Boeckxstaens, 2018). In addition, IBS and FM often co-occur in prevalent cases and the number of tender points is strongly associated with the severity of IBS but not the type (diarrhea- or constipation-predominant), suggesting a common abnormality of pain perception (Lubrano et al., 2001; Slim, Calandre, & Rico-Villademoros, 2015). Studies of prevalent cases have suggested that alterations in the gut microbiota (dysbiosis or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, including long term use of proton pump inhibitors) may explain this change in the gut-brain axis but, to our knowledge, these changes in the gut have not previously been shown to precede the onset of IBS (Slim et al., 2015).

Three of the four predictors shared by all three syndromes (somatic symptoms, disturbed sleep and negative health perception) had relatively low coefficients and are unlikely to reflect specific etiological pathways into new onsets of IBS, CFS and FM. Rather, they may be regarded as aspects of general ill health, which may be a predisposing factor for all syndromes. The fourth shared predictor, concerning stress related to chronic ill health, highlights one of the novel aspects of this study. In line with our systematic reviews, we found that many medical disorders and their relevant medications were important predictors of IBS and FM. Such disorders have been studied previously only as single disorders or as covariates so their overall importance has not been recognized. It seems that the inclusion of previous medical disorders and an extensive list of medications has led to psychological and social predictors becoming less prominent predictors. The high rate of medical comorbidity explains, in part, the high mortality of FM (Macfarlane et al., 2017).

The suggestion that IBS, CFS and FM have a shared etiology was based on their frequent coexistence, the similarity of their symptoms, the overlap of case definitions and similar correlates of prevalent cases (female sex, high prevalence of the emotional disorder, reported sexual abuse) (Wessely et al., 1999). Our study suggests that research should now move beyond mere descriptions of the syndromes and focus on risk factors and etiological pathways that are syndrome-specific or shared. For example, we need to be more specific about the medical disorders and medications that are predictors of the functional somatic syndromes and identify the syndrome-specific and shared etiological pathways into FM and IBS. We need to understand why is it so difficult to identify predictors of CFS. Further analysis of the Lifelines and similar data may answer some of these questions and generate more specific hypotheses that can be tested in clinical and laboratory studies. Such studies can be designed in the knowledge that there are probably a variety of different etiological pathways into each syndrome, a few of which may be shared between two or more syndromes.

In conclusion, our results indicate that syndrome-specific predictors are more relevant than shared predictors and do not support the notion of shared etiology among IBS, CFS and FM. These specific predictors might form a better starting point to unravel the heterogeneous etiologies of these syndromes than the current approach based on symptom patterns. The close relationship between IBS and FM is striking and warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The Lifelines Biobank initiative has been made possible by subsidy from the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG the Netherlands), University of Groningen and the Northern Provinces of the Netherlands. The authors wish to acknowledge the services of the Lifelines Cohort Study, the contributing research delivering data to Lifelines and all the study participants.

Author contributions

JGMR and FHC conceived and designed the study. FHC did the literature search. RM and KJW designed and executed the data analysis. FHC and RM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final draft for submission.

Ethical standards

Approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001774.

click here to view supplementary material

Conflict of interest

We declare no conflicting interests.

References

- Bakken, I. J., Tveito, K., Gunnes, N., Ghaderi, S., Stoltenberg, C., Trogstad, L., … Magnus, P. (2014). Two age peaks in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A population-based registry study from Norway 2008–2012. BMC Medicine, 12, 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckxstaens, G. (2018). The emerging role of mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 14, 250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha, T. S., & Cragg, D. (1990). The list of threatening experiences: The reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 82, 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M. H., Hsu, J. W., Huang, K. L., Su, T. P., Bai, Y. M., Li, C. T., … Chen, M. H. (2015). Bidirectional association between depression and fibromyalgia syndrome: A nationwide longitudinal study. Journal of Pain, 16, 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Creed, F. (2019). Review article: The incidence and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome in population-based studies. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 50, 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed, F. (2020) A review of the incidence and risk factors for fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain in population-based studies. Pain, 161(6), 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J., & Goadrich, M. (2006). The relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC curves. In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning University of Wisconsin Madison.

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnachie, E., Schneider, A., Mehring, M., & Enck, P. (2018). Incidence of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue following GI infection: A population-level study using routinely collected claims data. Gut, 67, 1078–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eekhout, I., De Vet, H. C. W., Twisk, J. W. R., Brand, J. P. L., De Boer, M. R., & Heymans, M. W. (2014). Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlin, A. G. C., Montgomery, S. M., Ekbom, A., Pounder, R. E., & Wakefield, A. J. (2003). Prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases in two British national birth cohorts. Gut, 52, 1117–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck, P., Aziz, Q., Barbara, G., Farmer, A. D., Fukudo, S., Mayer, E. A., … Spiller, R. C. (2016). Irritable bowel syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R.. (2010). Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descen. Journal of statistical software, 33(1), 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau, J., Grosse, I., & Keilwagen, J. (2015). PRROC: Computing and visualizing precision-recall and receiver operating characteristic curves in R. Bioinformatics, 31, 2595–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W. T., Gallagher, A. M., Thomas, J. M., & White, P. D. (2009). Risk markers for both chronic fatigue and irritable bowel syndromes: A prospective case-control study in primary care. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1913–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney, E., Smith, M. E. B., McDonagh, M., Pappas, M., Daeges, M., Wasson, N., & Nelson, H. D. (2015). Diagnostic methods for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162, 834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon, P., Nicholl, B. I., Jani, B. D., Lee, D., McQueenie, R., & Mair, F. S. (2018). Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: A prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. The Lancet Public Health, 3, e323–e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. B., Wessely, S., Kuh, D., & Hotopf, M. (2009). The relationship between fatigue and psychiatric disorders: Evidence for the concept of neurasthenia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66, 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häuser, W., & Fitzcharles, M.-A. (2018) Facts and myths pertaining to fibromyalgia. Les Laboratoires Servier. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 20, 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R. D., & Morales, L. S. (2001). The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of Medicine, 33, 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgate, S., Komaroff, A., Mangan, D., & Wessely, S. (2011). Chronic fatigue syndrome: Understanding a complex illness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12, 539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, K., Hudson, J. L., Rojczyk, P., Little, P., & Moss-Morris, R. (2017). Biopsychosocial risk factors of persistent fatigue after acute infection: A systematic review to inform interventions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 99, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason, L. A., Richman, J. A., Rademaker, A. W., Jordan, K. M., Plioplys A, V., Taylor, R. R., … Plioplys, S. (1999). A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159, 2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joustra, M. L., Janssens, K. A. M., Bültmann, U., & Rosmalen, J. G. M. (2015). Functional limitations in functional somatic syndromes and well-defined medical diseases. Results from the general population cohort LifeLines. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klijs, B., Scholtens, S., Mandemakers, J., Snieder, H., Stolk, R., & Smidt, N. (2015). Representativeness of the LifeLines Cohort Study. ed. Ali R. I.. PLos One, 10, e0137203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2018). Unmet needs of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3, 587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubrano, E., Iovino, P., Tremolaterra, F., Parsons, W. J., Ciacci, C., & Mazzacca, G. (2001). Fibromyalgia in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. An association with the severity of the intestinal disorder. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 16, 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, G. J., Barnish, M. S., & Jones, G. T. (2017). Persons with chronic widespread pain experience excess mortality: Longitudinal results from UK Biobank and meta-analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 76, 1815–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrie, R. A., Yu, B. N., Leung, S., Elliott, L., Warren, S., Wolfson, C., … Fisk, J. D. (2012). The incidence and prevalence of fibromyalgia are higher in multiple sclerosis than the general population: A population-based study. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 1, 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Morris, R., & Spence, M. (2006). To ‘lump’ or to ‘split’ the functional somatic syndromes: Can infectious and emotional risk factors differentiate between the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome? Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, E., Wessely, S., Chalder, T., Chang, C.-K., & Hotopf, M. (2016). Mortality of people with chronic fatigue syndrome: A retrospective cohort study in England and Wales from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Biomedical Research Centre (SLaM BRC) Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) register. The Lancet, 387, 1638–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmalen, J. G. M., Bos, E. H., & De Jonge, P. (2012). Validation of the long-term difficulties inventory (LDI) and the list of threatening experiences (LTE) as measures of stress in epidemiological population-based cohort studies. Psychological Medicine, 42, 2599–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens, S., Smidt, N., Swertz, M., Bakker, S., Dotinga, A., Vonk, J., … Stolk, R. (2015). Cohort Profile: LifeLines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44, 1172–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., … Dunbar, G. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 2), 22–33, quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibelli, A., Chalder, T., Everitt, H., Workman, P., Windgassen, S., & Moss-Morris, R. (2016). A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychological Medicine, 46, 3065–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slim, M., Calandre, E. P., & Rico-Villademoros, F. (2015). An insight into the gastrointestinal component of fibromyalgia: Clinical manifestations and potential underlying mechanisms. Rheumatology International, 35, 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Walitt, B., Katz, R. S., Bergman, M. J., & Wolfe, F. (2016). Three-quarters of persons in the US population reporting a clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia do not satisfy fibromyalgia criteria: The 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PLoS ONE, 11 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J. W., & Clauw, D. J. (2012). Functional somatic syndromes: Sensitivities and specificities of self-reports of physician diagnosis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74, 891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely, S., Nimnuan, C., & Sharpe, M. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes: One or many? The Lancet, 354, 936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F., Schmukler, J., Jamal, S., Castrejon, I., Gibson, K. A., Srinivasan, S., … Pincus, T. (2019). Diagnosis of fibromyalgia: Disagreement between fibromyalgia criteria and clinician-based fibromyalgia diagnosis in a university clinic. John Wiley and Sons Inc. Arthritis Care and Research, 71, 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001774.

click here to view supplementary material