Abstract

Background:

Identifying men living with HIV in sub-Saharan (SSA) Africa is critical to end the epidemic. We describe the underlying factors of unawareness among men 15–59 years of age who ever tested for HIV in 13 SSA countries.

Methods:

Using pooled data from nationally representative Population-based HIV Impact Assessments, we fit a log-binomial regression model to identify characteristics related to HIV positivity among HIV+ unaware and HIV negative men ever tested for HIV.

Results:

A total of 114,776 men interviewed and tested for HIV; 4.4% were HIV+. Of those, 33.7% were unaware of their HIV+ status, (range: 20.2%−58.7%, in Rwanda and Cote d’Ivoire respectively). Most unaware men reported they had ever received an HIV test (63.0%). Age, region, marital status, and education were significantly associated with HIV positivity. Men who had positive sexual partners (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 5.73; confidence interval [95% CI]: 4.13–7.95) or sexual partners with unknown HIV status (aPR: 2.32; 95% CI:1.89–2.84) were more likely to be HIV + unaware, as were men who tested more than 12 months compared to HIV negative men who tested within 12 months prior to the interview (aPR: 1.58; 95% CI:1.31–1.91). Tuberculosis diagnosis and not being circumcised were also associated with HIV positivity.

Conclusion:

Targeting subgroups of men at risk for infection who once tested negative could improve yield of testing programs. Interventions include, improving partner testing, frequency of testing, outreach and educational strategies, and availability of HIV testing where men are accessing routine health services.

Keywords: PHIA, HIV household survey, HIV unawareness, HIV positivity, MLHIV, HIV testing, JAIDS, PHIA Special Issue

Introduction

Inadequate testing and treatment coverage among men living with HIV (MLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has slowed progress toward the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) goal of reaching HIV epidemic control by 2030.1 In particular, men contribute disproportionately to the gap in achieving the global target of 95% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) knowing their status.1,2 As of 2019, there were approximately 9.8 million MLHIV in SSA. Although progress in treatment coverage has increased in the region, reductions in new infections and deaths due to AIDS-related illness have been slower among men than women.2,3 In 2019, men accounted for a lower proportion (only 38%) of PLHIV compared to women, but men contributed 57% to the burden of AIDS-related deaths.1,2

When compared to women, men test less frequently for HIV, less frequently know their status, less regularly access HIV services, and more commonly present with advanced disease.4–9 MLHIV who are undiagnosed are at risk for poor health outcomes, including co-infection with tuberculosis (TB), other disease comorbidities, and increased AIDS-related mortality.9,10 In 2019, treatment coverage was 12% and viral load suppression was 10% higher among women than men living with HIV globally.8 This treatment gap among MLHIV contributes to further transmission and a higher number of new HIV infections among their partners.3,4 Once diagnosed and on treatment, decreased viral load will result in reduced transmission. The Population-based HIV Impact Assessments (PHIAs) have shown that adult men who knew their HIV status had high rates of ART use (90.2%) and viral suppression (85.0%).10

Access to and acceptability of testing is the first critical step in ensuring MLHIV are diagnosed and treated. Recent efforts have intensified to find and test high-risk men to initiate them on HIV treatment. The U.S President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and other agencies supporting the HIV response have heavily invested in HIV testing strategies focused on men in SSA.10,11 Typical approaches have included provider-initiated counseling and testing (PITC) in health facilities and voluntary counseling and testing (VCT).12 Partner-initiated and index testing have emerged to reach a high volume and yield of new cases among men.12,13 Self-testing has helped in increasing testing uptake as part of community based testing.14,15 In addition, men lack universal entry points for HIV testing compared to women who utilize reproductive or family health services more readily.4 To address this, other approaches to reach men include differentiated service delivery models, mobile testing sites in places where men work and frequent, and male centered clinics offering comprehensive outpatient services for all men regardless of HIV status.16,17

To improve testing coverage for men, it is useful to examine testing behaviors among men. Characteristics of men that have never been tested have been previously described. A study using Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data from six African countries found that although a higher proportion of men than women had never tested for HIV, most men accepted a test when offered.18 Factors associated with never having tested for HIV included never being married, not having children, and lower education, after adjusting for age.18 With resources dedicated to reach young men who haven’t tested before,10 additional strategies are needed to identify those men who once tested negative but remain at risk for infection and may need more frequent testing. Identifying those who have previously tested by characterizing subgroups of men at risk for infection could improve yield of testing programs. In addition, men who ever tested are generally older and more sexually active, thus, their risk of being positive may be higher than those who never received an HIV test.19

The PHIAs are nationally representative household-based surveys to measure key indicators of progress in controlling the HIV epidemic. With the availability of self-reported testing behavior and HIV biomarker status, which includes laboratory detection of antiretrovirals (ARVs), the PHIAs provide a unique opportunity to examine factors associated with undetected HIV infection among men.

This analysis used pooled PHIA data from 13 countries in SSA to describe men aged 15–59 years who were unaware of their HIV+ status and to describe risk factors among unaware MLHIV who ever tested. The goal of the findings is to develop targeted interventions to optimize testing strategies to reach MLHIV who are unaware of their HIV+ status.

Methods

For the analysis, we pooled PHIA data from Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Countries were grouped together using standard UN regional definitions.20 Data collection started for the first survey in October 2015, and completion of fieldwork for the last survey was in March 2019.

Data Collection Procedures

The PHIAs utilized a two-stage cluster sampling design in order to obtain nationally representative samples of households in each country, stratified by designated geographical zones.21 The design and implementation of the PHIA surveys have been described elsewhere.22,23 Face-to-face interviews were conducted to capture demographic, behavioral, and clinical information, including self-reported knowledge of HIV status and testing history. Individuals were eligible to participate if they slept in the household the night before the interview and were at least 15 years old. This analysis was restricted to 15–59 years, as this age group was shared across all 13 countries.

The surveys included home-based HIV testing and counseling, return of results, community active linkage-to-care where possible, and laboratory-based confirmation of HIV positive and indeterminate results by each national testing algorithm. In addition to HIV diagnostic testing, most countries provided CD4 and HIV viral load testing. Testing for coinfections such as syphilis and hepatitis B/C varied depending on the country. Participants testing positive at the household received a point-of-care CD4 count in the household, lab-based HIV viral load, and were screened for ARV drugs indicative of the first- and second-line HIV treatment regimens in each country. HIV viral load results were returned to participants through health facilities of their choice. Viral load suppression (VLS) was defined as <1,000 HIV RNA copies per milliliter.

Definition of variables

Final HIV status classification in the PHIA was determined by the result of the rapid test result at the household, followed by laboratory confirmation. Unawareness and awareness of HIV+ status was determined based on responses provided in the survey questionnaire, final HIV classification status in the survey, and detection of ARVs. Participants who tested positive for HIV during the survey were considered aware if they reported in the interview being HIV positive or ARVs were detected in their blood. Participants who tested positive for HIV during the survey were considered unaware if they reported having a negative or unknown HIV status and ARVs were not detected in their blood. The outcomes of interest used in this analysis were unawareness of HIV+ status and HIV positivity. HIV positivity was defined as receiving an HIV+ result among HIV+ unaware and HIV negative men who ever tested. Ever tested was categorized as those who reported yes to ever testing for HIV.

The wealth category of “upper 60%” included the top three wealth quintiles and “lower 40%” included the bottom two wealth quintiles, with wealth relative to others in their country. Partner status was defined for sexual partnerships in the past 12 months and includes four categories assigned sequentially: no partners in that time period; positive if think, told, or tested together as positive for one or more of their partners; unknown status for one or more of their partners; and negative for think, told, or tested together as negative for all of their partners. Hazardous drinking was determined by the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test score over 4 based on points assigned to three alcohol use questions.24 Medical circumcision was defined if the male participant reported being circumcised by a health care provider such as a doctor, nurse, or midwife and traditional circumcision was defined as being circumcised by a traditional practitioner, religious leader, or relative/friend. Tested in the last 12 months was defined as those participants who reported testing for HIV in the last 12 months and receiving results.

Statistical Analysis

Data were weighted to account for sample selection probabilities and to adjust for nonresponse and noncoverage. Normalized weights in Rwanda and Kenya were re-scaled to population weights for consistency with the remainder of the countries, by multiplying the weights by a factor of the total estimated population size over the number of interview respondents. All estimates were weighted, and we used Taylor series expansion to obtain robust variance estimators for the complex survey data. Weighted chi-squared and t-test analyses were conducted to identify associations between unawareness of HIV+ status and sociodemographic, risk and testing behaviors among HIV+ men and HIV negative men who had ever tested.

We fit a log-binomial regression model to identify associations between HIV positivity among HIV+ unaware and HIV negative men who ever tested. Covariates included in the adjusted model were based on previous literature, plausible hypotheses, bivariate analyses, and if shared across all countries. Number of sexual partners were not included due to collinearity and was not found to contribute to model fit. We calculated weighted crude and adjusted-prevalence ratios examining the potential predictors of interest and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI). Level of significance was set to α = 0.05 in the fitted models. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 and SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 11.0.3.

Implementation and Ethics

The PHIAs were funded by PEPFAR with technical assistance through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of the cooperative agreement #U2GGH001226. The surveys were implemented by cooperative agreement grantees/federal entities, including country Ministries of Health, ICAP at Columbia University, and the University of California San Francisco. Each survey was approved by human subjects and institutional review boards of each country, cooperative agreement grantees/federal entities implementing the survey, and CDC.

Results

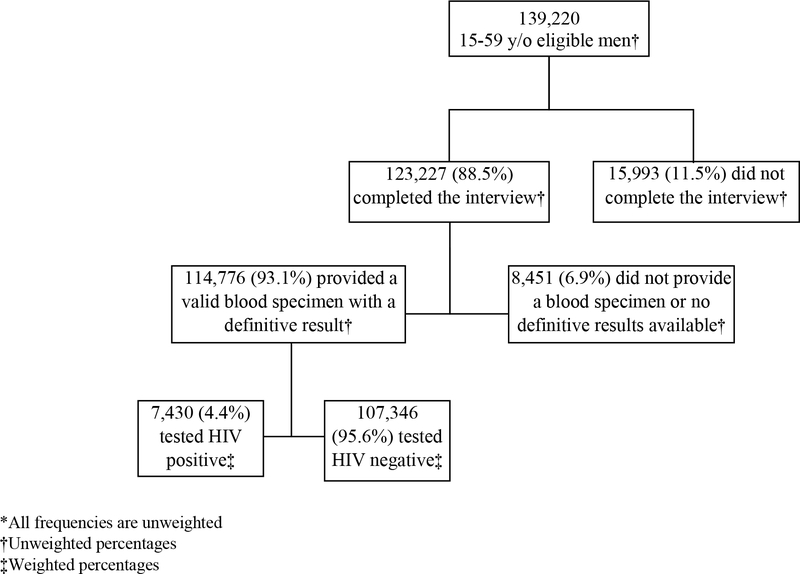

There were 409,855 eligible respondents in the pooled sample from the 13 countries in SSA, of whom 139,220 were men aged 15–59 years. The household response rate was 90.8% and 123,227 (88.5%) of the eligible men age 15–59 years were interviewed. Of those interviewed, 114,776 (93.1%) provided a valid blood specimen with a definitive HIV testing result, for an overall response rate of 74.8%. Among those with definitive results, 7,430 (4.4%) tested HIV+ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of interview completion and blood sampling among men aged 15–59 years in 13 sub-Saharan countries, 2015–2019*

HIV prevalence and the proportion of unawareness of HIV+ status among MLHIV are presented in Table 1. Overall, Southern African countries had the highest prevalence, followed by Southeastern, Eastern, and Western African countries. Higher unawareness was found in Western African compared to Southern, Southeastern, and Eastern Africa countries, except Tanzania, where 46.8% of men were unaware of their HIV+ status.

Table 1.

HIV prevalence and unawareness by country of HIV positive status among men aged 15–59 years, in 13 sub-Saharan countries, 2015–2019

| Region* | Country | HIV+ | HIV+ Unaware | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N‡ | LCL | UCL | % | N‡ | LCL | UCL | ||

| Western | Cameroon 2017–2018† |

2.3 | 11,332 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 49.8 | 267 | 45.7 | 54.0 |

| Cote d'Ivoire 2017–2018 |

1.6 | 8,580 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 58.7 | 124 | 51.6 | 65.9 | |

| Eastern | Ethiopia 2017–2018 |

1.9 | 7,314 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 30.5 | 146 | 25.9 | 35.1 |

| Kenya 2018 |

3.1 | 11,185 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 28.5 | 394 | 25.2 | 31.7 | |

| Rwanda 2018–2019 |

2.2 | 13,277 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 20.2 | 285 | 17.4 | 23.0 | |

| Tanzania 2016–2017 |

3.5 | 12,271 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 46.8 | 517 | 42.3 | 51.2 | |

| Uganda 2016–2017 |

4.7 | 11,903 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 33.3 | 542 | 29.8 | 36.8 | |

| Southeastern | Malawi 2015–2016 |

8.4 | 6,956 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 28.8 | 679 | 25.6 | 31.9 |

| Zambia 2016 |

9.3 | 8,142 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 30.3 | 779 | 27.0 | 33.5 | |

| Zimbabwe 2015–2016 |

11.8 | 8,006 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 28.6 | 1,084 | 25.7 | 31.5 | |

| Southern | Eswatini 2016–2017 |

20.4 | 4,023 | 18.6 | 22.1 | 20.8 | 871 | 18.2 | 23.5 |

| Lesotho 2016–2017 |

20.8 | 4,762 | 19.6 | 22.0 | 23.4 | 1,019 | 21.2 | 25.6 | |

| Namibia 2017 |

9.2 | 7,025 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 21.1 | 720 | 17.9 | 24.3 | |

| Total | 4.4 | 11,4776 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 33.7 | 7,427 | 32.5 | 34.9 | |

LCL: Lower Confidence Limits; UCL: Upper Confidence Limits

Countries grouped by region using standard regional definitions: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

Survey Year

All frequencies are unweighted

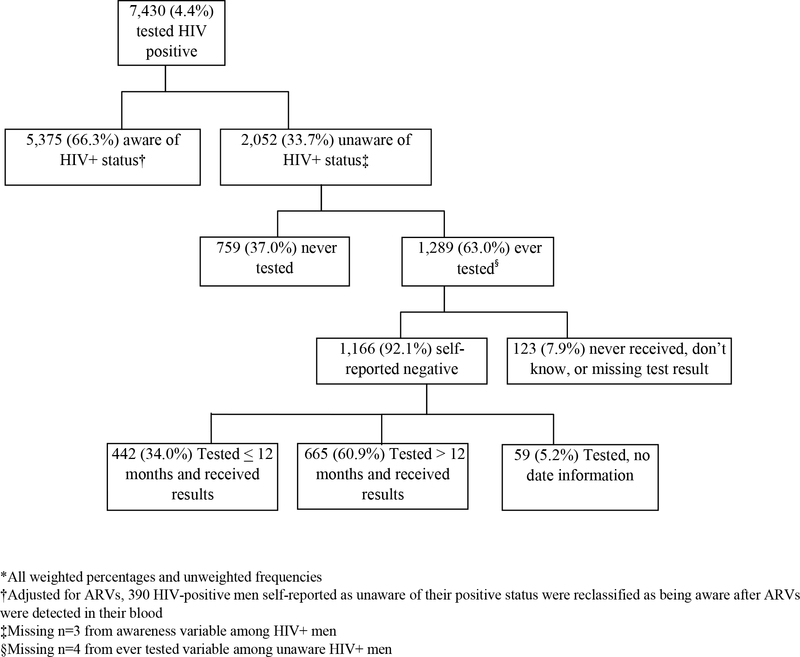

Figure 2 shows men’s HIV status unawareness with regard to their testing behavior. Of the 7,430 HIV+ men, 33.7% were unaware of their HIV+ status, based on self-report and/or laboratory detection of ARVs. Fourteen percent (n=390) of HIV+ men who reported being as unaware of their positive status were reclassified as being aware after ARVs were detected in their blood. Most of the unaware HIV+ men reported they had ever had an HIV test, 63.0% (n=1,289). Of the unaware men who ever tested, 92.1% (n=1,166) reported they were HIV negative and 7.9% (n=123) reported that they never received their results, didn’t know the results, or results were missing. Of the unaware HIV+ men that reported being HIV negative, 60.9% (n=665) reported testing and receiving their HIV results more than 12 months prior to the date of the interview. Most unaware HIV+ men were not virally suppressed (n=1,860, 91.1%); 47.7% had a CD4 count less than 350 cells/uL (n=912) and 17.9% (n=351) had a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/uL (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of awareness/unawareness status and testing characteristics among HIV positive men aged 15–59 years, in 13 sub-Saharan countries, 2015–2019*

Most unaware HIV+ men ever tested were 25–34 years (36.7%), were in the upper 60% wealth category (62.8%) and employed in the last 12 months (65.8%). Seventy percent of unaware men ever tested reported not using a condom at last sex in the last 12 months, and 37.1% reported one or more sexual partner of unknown status in the last 12 months. More than half (59.8%) of unaware men ever tested engaged in hazardous drinking and were uncircumcised (46.2%). Most men, regardless of awareness status, reported receiving their last HIV test at a health clinic or facility, but more unaware men (13.6% vs. 4.3%) reported their last HIV test at a mobile VCT site compared to HIV+ men who were aware of their status. More unaware HIV+ men than HIV negative men had a STD diagnosis and STI symptoms in the last 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of selected characteristics among ever tested unaware/aware HIV+ men and HIV negative men aged 15–59 years, in 13 sub-Saharan countries, 2015–2019

| Characteristics | Unaware HIV+ men |

Aware HIV+ men |

p-value* | HIV negative men |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age | |||||

| Median age (Q1, Q3) | 34 (28, 42) | 41 (34, 47) | <0.0001 | 30 (23, 38) | <0.0001 |

| Age Group | |||||

| 15–24 years | 11.8 | 5.6 | <0.0001 | 28.9 | <0.0001 |

| 25–34 years | 36.7 | 18.3 | 34.4 | ||

| 35–44 years | 30.0 | 38.0 | 21.6 | ||

| 45–59 years | 21.5 | 38.1 | 15.0 | ||

| Residence ‡ | |||||

| Urban | 39.1 | 38.6 | 0.7311 | 42.0 | 0.1583 |

| Rural | 60.9 | 61.4 | 58.0 | ||

| Region | |||||

| Western Africa | 9.9 | 5.1 | <0.0001 | 12.8 | <0.0001 |

| Eastern Africa | 53.2 | 46.1 | 69.0 | ||

| Southeastern Africa | 31.1 | 39.5 | 15.9 | ||

| Southern Africa | 5.8 | 9.3 | 2.3 | ||

| Education | |||||

| None | 16.8 | 14.2 | 0.0405 | 13.6 | 0.0042 |

| Primary | 44.2 | 46.6 | 40.9 | ||

| Post primary | 39.0 | 39.2 | 45.5 | ||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Never married | 14.3 | 10.8 | <0.0001 | 33.3 | <0.0001 |

| Married or living together | 71.3 | 73.7 | 60.3 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 12.5 | 10.8 | 5.8 | ||

| Widowed | 1.8 | 4.7 | 0.5 | ||

| Wealth Category | |||||

| Lowest 40% | 37.2 | 36.0 | 0.4051 | 35.6 | 0.4114 |

| Upper 60% | 62.8 | 64.0 | 64.4 | ||

| Employed in the last 12 months | |||||

| Employed | 65.8 | 60.0 | 0.0002 | 63.2 | 0.1772 |

| Not Employed | 34.2 | 40.0 | 36.8 | ||

| Sexual Partners in last 12 months | |||||

| No sexual partners | 15.3 | 19.0 | <0.0001 | 21.0 | <0.0001 |

| One sexual partner | 55.7 | 59.5 | 56.8 | ||

| Two or more sexual partners | 29.0 | 21.4 | 22.2 | ||

| Reported partner status in last 12 months | |||||

| All negative partners | 53.8 | 23.7 | <0.0001 | 74.7 | <0.0001 |

| At least one positive partner | 9.1 | 62.3 | 1.6 | ||

| At least one unknown partner | 37.1 | 14.0 | 23.7 | ||

| Condom Use at last Sex in last 12 months | |||||

| No sex in the last 12 months | 13.7 | 16.1 | <0.0001 | 13.9 | 0.6823 |

| Used condom | 16.5 | 37.7 | 17.9 | ||

| Did not use condom | 69.8 | 46.2 | 68.2 | ||

| Paid for sexual intercourse in the last 12 months § | |||||

| Paid sex | 12.0 | 9.7 | 0.1695 | 8.5 | 0.0608 |

| Did not pay for sex | 88.0 | 90.3 | 91.5 | ||

| Alcohol use ¶ | |||||

| Hazardous drinking | 59.8 | 51.9 | 0.0015 | 52.4 | 0.0275 |

| Non-hazardous drinking | 40.2 | 48.1 | 47.6 | ||

| STD diagnosis in the last 12 months ** | |||||

| STD diagnosis | 4.5 | 6.9 | 0.0527 | 2.4 | 0.0111 |

| No STD diagnosis | 95.5 | 93.1 | 97.6 | ||

| STI symptoms# in the last 12 months** | |||||

| STI symptoms | 20.8 | 22.2 | 0.4529 | 13.9 | 0.0003 |

| No STI symptoms | 79.2 | 77.8 | 86.1 | ||

| TB diagnosis | |||||

| TB diagnosis at TB clinic | 4.5 | 20.1 | <0.0001 | 2.3 | <0.0001 |

| No TB diagnosis at TB clinic | 6.8 | 18.5 | 4.1 | ||

| Not visited a TB clinic | 88.7 | 61.4 | 93.5 | ||

| Circumcision | |||||

| Medical circumcision | 31.5 | 22.0 | <0.0001 | 42.6 | <0.0001 |

| Traditional circumcision | 22.3 | 18.7 | 29.0 | ||

| Uncircumcised | 46.2 | 59.3 | 28.4 | ||

| Tested and received results | |||||

| Tested ≤12 months | 36.5 | 39.8 | 0.0618 | 49.4 | <0.0001 |

| Tested >12 months | 63.5 | 60.2 | 50.6 | ||

| Time since last HIV test | |||||

| Median months (IQR) | 18 (7,46) | 21 (5,65) | <0.0001 | 12 (4,32) | <0.0001 |

| Location of last HIV test | |||||

| Health clinic/facility | 45.7 | 58.7 | <0.0001 | 45.5 | 0.1182 |

| Hospital outpatient clinic | 13.6 | 13.1 | 11.1 | ||

| VCT facility | 12.4 | 11.8 | 13.1 | ||

| Mobile VCT | 13.6 | 4.3 | 13.9 | ||

| Outreach | 5.5 | 3.9 | 4.4 | ||

| Hospital inpatient wards | 3.0 | 4.2 | 2.5 | ||

| ANC clinic | 2.4 | 0.9 | 3.9 | ||

| At home | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.8 | ||

| Other | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.8 | ||

|

| |||||

| Total N | 1289 | 5271 | 67500 | ||

p-value from weighted chi-square and t-test to test differences among unaware and aware HIV+ men

p-value from weighted chi-square and t-test to test differences among HIV+ unaware and HIV negative men

Ethiopia: small urban area defined as rural and large urban areas defined as urban; Lesotho: peri-urban and urban are defined as urban

Excluding Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe

Hazardous drinking was determined by an AUDIT score over 4 based on points assigned to three alcohol use questions; excluding Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Rwanda, Uganda

Penile discharge, painful urination, or ulcer/sore

Excluding Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda

Prevalence ratios of HIV positivity among ever tested men are presented in Table 3. After adjustment, compared to HIV negative men 15–24 years there was an increased risk of receiving a HIV+ result and being unaware associated with age of 25–34 years [adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR): 1.84; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.29–2.63], 35–44 years (aPR: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.44–2.99), and 45–59 years (aPR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.18–2.56). Compared to HIV negative men in Eastern Africa, living in a sampled country in Southeastern Africa (aPR: 2.23; 95% CI: 1.81–2.75), and Southern Africa (aPR: 3.60; 95% CI: 2.91–4.44) was associated with increased risk. The risk of receiving a HIV+ result and being unaware was about two times as likely in those with no education (aPR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.09–2.05), compared to those with post primary education. Compared to those never married, married men or those living together with a partner (aPR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.55–3.00), divorced/separated (aPR: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.20–4.85), and widowed men (aPR: 4.13; 95% CI: 2.09–8.18) had a greater likelihood of being HIV positive and unaware than HIV negative. Effects for all other socio-demographic covariates (urban versus rural residence, wealth, and employment status) were not significant. Men who had one or more HIV-positive sexual partners (aPR: 5.73; 95% CI: 4.13–7.95), or sexual partners with unknown HIV status (aPR: 2.32; 95% CI:1.89–2.84), had higher risk of receiving a HIV+ result and being unaware compared to HIV negative men with all HIV negative sexual partners. Men who had a TB diagnosis were also more likely to be HIV positive and unaware compared to negative men who had not visited a TB clinic (aPR: 1.67; 95% CI:1.08–2.59), as were uncircumcised men compared to HIV negative men who had undergone medical circumcision (aPR: 1.35; 95% CI:1.04–1.74); and men who tested more than 12 months from the interview compared to HIV negative men who tested within the 12 months prior to the interview (aPR: 1.58; 95% CI:1.31–1.91).

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios of HIV positivity by selected characteristics, among ever tested HIV+ unaware and HIV negative men aged 15–59 years, in 13 sub-Saharan countries, 2015–2019

| Characteristics | HIV+ unaware* | HIV negative | N | cPR | LCL | UCL | aPR | LCL | UCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Age Group | |||||||||

| 15–24 years | 0.6 | 99.4 | 20089 | REF | REF | ||||

| 25–34 years | 1.6 | 98.4 | 22323 | 2.60 | 1.97 | 3.43 | 1.84 | 1.29 | 2.63 |

| 35–44 years | 2.1 | 97.9 | 15223 | 3.36 | 2.53 | 4.47 | 2.07 | 1.44 | 2.99 |

| 45–59 years | 2.1 | 97.8 | 11436 | 3.45 | 2.58 | 4.61 | 1.74 | 1.18 | 2.56 |

| Residence † | |||||||||

| Urban | 1.4 | 98.6 | 28237 | REF | REF | ||||

| Rural | 1.6 | 98.4 | 42834 | 1.27 | 1.07 | 1.50 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 1.21 |

| Region | |||||||||

| Western Africa | 1.2 | 98.8 | 7876 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 1.36 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.67 |

| Eastern Africa | 1.2 | 98.8 | 37630 | REF | REF | ||||

| Southeastern Africa | 3.0 | 97.0 | 13562 | 2.49 | 2.10 | 2.95 | 2.23 | 1.81 | 2.75 |

| Southern Africa | 3.8 | 96.2 | 10003 | 3.17 | 2.67 | 3.76 | 3.60 | 2.91 | 4.44 |

| Education | |||||||||

| None | 2.0 | 98.0 | 7084 | 1.44 | 1.10 | 1.87 | 1.49 | 1.09 | 2.05 |

| Primary | 1.7 | 98.2 | 27481 | 1.26 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 1.13 | 0.91 | 1.41 |

| Post primary | 1.4 | 98.6 | 33099 | REF | REF | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Never married | 0.7 | 99.3 | 24675 | REF | REF | ||||

| Married or living together | 1.8 | 98.2 | 40012 | 2.71 | 2.17 | 3.39 | 2.15 | 1.55 | 3.00 |

| Divorced/separated | 3.2 | 96.8 | 3753 | 4.85 | 3.55 | 6.62 | 3.27 | 2.20 | 4.85 |

| Widowed | 4.9 | 95.1 | 452 | 7.34 | 4.43 | 12.16 | 4.13 | 2.09 | 8.18 |

| Wealth Category | |||||||||

| Lowest 40% | 1.6 | 98.4 | 26400 | 1.07 | 0.91 | 1.26 | - | - | - |

| Upper 60% | 1.5 | 98.5 | 42629 | REF | |||||

| Employed in the last 12 months | |||||||||

| Employed | 1.6 | 98.4 | 40922 | 1.12 | 0.95 | 1.32 | - | - | - |

| Not employed | 1.4 | 98.6 | 28121 | REF | REF | ||||

| Status of Sexual Partners in last 12 months | |||||||||

| No sexual partners | 1.5 | 98.5 | 13966 | 1.30 | 0.96 | 1.76 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 2.36 |

| All negative partners | 1.1 | 98.9 | 34274 | REF | REF | ||||

| One or more positive partners | 8.3 | 91.7 | 1100 | 7.44 | 5.52 | 10.03 | 5.73 | 4.13 | 7.95 |

| One or more unknown partners | 2.4 | 97.6 | 12569 | 2.14 | 1.78 | 2.58 | 2.32 | 1.89 | 2.84 |

| TB diagnosis | |||||||||

| TB diagnosis at TB clinic | 2.9 | 97.1 | 1712 | 3.27 | 2.21 | 4.84 | 1.67 | 1.08 | 2.59 |

| No TB diagnosis at TB clinic | 2.5 | 97.5 | 3311 | 2.89 | 1.96 | 4.25 | 1.30 | 0.93 | 1.83 |

| Not visited a TB clinic | 1.5 | 98.5 | 63850 | REF | REF | ||||

| Circumcision | |||||||||

| Medical circumcision | 1.1 | 98.9 | 25391 | REF | REF | ||||

| Traditional circumcision | 1.2 | 98.8 | 15116 | 1.04 | 0.81 | 1.34 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 1.16 |

| Uncircumcised | 2.5 | 97.5 | 26431 | 2.17 | 1.77 | 2.65 | 1.35 | 1.04 | 1.74 |

| Tested and received results | |||||||||

| Tested ≤12 months | 1.1 | 98.9 | 32031 | REF | REF | ||||

| Tested >12 months | 1.8 | 98.2 | 32378 | 1.69 | 1.63 | 2.02 | 1.58 | 1.31 | 1.91 |

cPR: crude Prevalence Ratio; aPR: adjusted Prevalence Ratio; LCL: Lower Confidence Limits; UCL: Upper Confidence Limits

n=1289

Ethiopia: small urban area defined as rural and large urban areas defined as urban; Lesotho: peri-urban and urban are defined as urban

Discussion

We examined unawareness of HIV+ status among men aged 15–59 years in 13 countries in SSA with a focus on men who had ever tested for HIV. At the population level in the 13 countries, this represents an estimated 3,138,000 MLHIV aged 15–59 years, 948,000 of whom were undiagnosed for HIV. We found most MLHIV unaware of their HIV+ status were virally unsuppressed, nearly half of whom had a CD4 count less than 350 cells/uL. In addition, a large percentage of HIV+ unaware men reported testing more than 12 months before the interview. MLHIV who present late to the clinic with a low CD4 count have an increased probability of poor health outcomes and HIV-related mortality.4–7 By knowing their status and commencing treatment, MLHIV will be able to lead longer, healthier lives as well as prevent further onward transmission of HIV to their sexual partners.

Though recent emphasis in high burden countries has been on identifying younger men (15–24 years) for testing, this analysis suggests that there is a larger burden of infected and undiagnosed men aged 25 years and older. Studies have found that most HIV+ men not engaged in HIV prevention and treatment services are over 35 years of age, which aligns with the age at the highest prevalence.11,18,25 Our findings of low education level as a risk factor for HIV positivity in unaware men reinforce the need for focused health education strategies targeting men at risk of HIV infection. Other research in the sub-Saharan region has previously described limited health literacy, especially among those with lower education levels among men.11,17,26 Importantly, a review that described barriers of HIV testing uptake in men found most men had knowledge of where to access HIV services but lacked an understanding of ongoing risks of HIV transmission.26 Results suggest the need to improve messaging to underscore that a previously negative test does not necessarily mean a current negative status for those at risk of infection and to thus increase the acceptability and frequency of testing for men in this target group.

HIV testing more than 12 months prior to the survey was predictive of HIV positivity among men in our study. This provides evidence for the need to increase the frequency and access to HIV testing for men with an ongoing risk of HIV infection and to retest annually or more frequently depending on risk. In addition, these findings of the increased risk of being HIV+ and unaware among those diagnosed with TB and those uncircumcised demonstrates the need to increase availability of HIV testing at all service delivery points, such as outpatient departments, voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) clinics, and as part of screening for TB and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These findings also demonstrate a missed opportunity for HIV testing for the unaware HIV+ men who accessed health services, if these services were sought after onset of infection.

Tailoring available service delivery points with innovative approaches may be effective to reach men who otherwise would be less prone to access facility-based services unless presenting with advanced stage of disease.26 Differentiation delivery of services has included male-friendly services, use of clinics for men to improve confidentiality/privacy, ensure shorter wait times, and provide extended service delivery hours, which have been met with success in increasing testing uptake in some countries.11,13,27–30 Use of community-based mobile HIV-testing was commonly reported among HIV+ unaware men and could be utilized in combination with other options, such as self-testing, which is being scaled up in certain SSA countries.31 Though few men reported testing at home, scale-up of self-testing occurred after most of the PHIA surveys used for this analysis were conducted.

The strong association found in partners reported as HIV-positive or of unknown status further strengthens partner testing and contact tracing as effective strategies to identify men who do not know their HIV+ status.9,11 Given that most unaware men were unsuppressed and reported not using a condom in the last 12 months, their partners are at risk of getting infected. These findings also highlight that men are at risk of acquiring infection by not using a condom while knowing their partner(s) is/are HIV-positive or of unknown status. This underscores the importance of basic prevention measures, including the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and condoms in HIV-discordant couples.1

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this analysis is the population representative data across 13 countries with biomarkers linked to demographic and behavioral data. A limitation is that some of the data are based on surveys that started in 2015 and may not reflect the current environment. Our findings use self-report of testing and behavioral factors, which participants may not have disclosed due to social desirability bias. Though ARV testing was used to correct for those on treatment, it is likely that some previously diagnosed participants who were not on treatment did not want to disclose their HIV+ status, potentially overestimating the true proportion of men’s unawareness. Certain variables of interest were not available across all countries and the application of some of these findings may not apply due to contextual/programmatic differences between countries. Caution should also be used when generalizing findings to the western African region as data from only two countries were included in this study’s regional analysis.

Examining characteristics associated with HIV positivity was shown to be a useful approach and such analyses have been used to develop risk screening tools as part of universal PITC and counseling in facilities across high burden countries, where the goal is to identify undiagnosed PLHIV and optimize testing yield.32 Once validated, these tools can be adapted by region and selected demographics. However, if the risk screening tools are shown to be an effective method to reach unaware MLHIV earlier and linking them to care in different contexts, then further evaluation of the tools’ predictive value is critical.11

Conclusion

The results from this large sample suggest that many men in sub-Saharan Africa are likely unaware of their HIV+ status due to the compounding effects of sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical influences, albeit with context-specific drivers in each country that are outside the scope of this analysis. Our results found that men who were unaware of their HIV+ status were at increased risk of poor health outcomes and need earlier engagement of HIV services. When taken together with prior literature, our findings demonstrate that attaining the 95–95-95 UNAIDS goal among MLHIV by 2030 is challenging. Targeted scale-up of both facility- and community-based approaches will help ensure that MLHIV are health literate, equitably reached, know their status, and are linked to HIV treatment services soon after infection. With the increased availability of standard and new approaches for testing men, more men are being reached for testing, but those at risk still need to test more often. Increased access to and frequency of HIV testing is needed to identify undetected infection in men including in settings where they are accessing services for TB and VMMC. Our findings also support prior evidence that partner/couples testing and tracing partners’ contacts through index testing may help identify HIV+ men unaware of their status.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Blind spot: Reaching out to men and boys. Addressing a blind spot in the response to HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2017. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/blind_spot_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update, 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/unaids-data.

- 3.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update, 2018. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf

- 4.Auld AF, Shiraishi RW, Mbofonah F, et al. Lower Levels of Antiretroviral Therapy Enrollment Among Men with HIV Compared with Women—12 Countries, 2002–2013.MMWR. November 27, 2015 / 64(46);1281–1286. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6446a2.htm?s_cid=mm6446a2_w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson LF. Access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa, 2004–2011. S Afr J HIV Med. 2012;13(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osler M, Cornell M, Ford N, et al. Population-wide differentials in HIV service access and outcomes in the Western Cape for men as compared to women, South Africa: 2008 to 2018: a cohort analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(S2):e25530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma M, Barnabas RV, Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men’s engagement in the HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14:e1002262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. Women living with HIV are more likely to access HIV testing and treatment. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/october/20201005_women-hiv-testing-treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maman D, Farhat JB, Chilima B, et al. , Factors associated with HIV status awareness and linkage to care following home based testing in rural Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2016. November;21(11):1442–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PEPFAR. 2019. Annual Report to Congress. U.S. Department of State. Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy. https://www.state.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2019/09/PEPFAR2019ARC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimsrud A, Ameyan W, Ayieko J, et al. Shifting the narrative: from the missing men to we are missing the men. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(S2):e25526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drammeh B, Medley A, Dale H et al. , Sex Differences in HIV Testing—20 PEPFAR-Supported Sub-Saharan African Countries, 2019. MMWR 69(48):1801–1806. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6948a1.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mwango LK, Stafford KA, Blanco NC, et al. Index, and targeted community-based testing to optimize HIV case finding and ART linkage among men in Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(S2):e25520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Indravudh PP, Choko AT, Corbett EL, Scaling up HIV self-testing in sub-saharan Africa: a review of technology, policy and evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018; 31(1): 14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Napierala S, Bair EF, Maruc N, et al. Male partner testing and sexual behaviour following provision of multiple HIV self-tests to Kenyan women at higher risk of HIV infection in a cluster randomized trial; J Int AIDS Soc. 2020, 23(S2):e25515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stender SC, Rozario A. Khotla Bophelong Bo Botle: a gathering of men for health. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(S2):e25511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dovel K, Dworkin SL, Cornell M, et al. Gendered health institutions: examining the organization of health services and men’s use of HIV testing in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(S2):e25517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn C, Kadengye DT, Johnson CC, et al. , Who are the missing men? Characterising the men who never tested for HIV from population-based surveys in six sub-Saharan African countries. J Int AIDS Soc.. 2019;22:e25398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makusha T, Mabaso M, Richter L, et al. , Trends in HIV testing and associated factors among men in South Africa: evidence from 2005, 2008 and 2012 national population-based household surveys, Public Health, 2017,143:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Methodology. Standard country or area codes for statistical use. United Nations. Statistics Division. 2020. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown K, Williams DB, Kinchen S, et al. Status of HIV Epidemic control among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years – seven African countries, 2015–2017. MMWR 2018. 67(10: 29–32. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6701a6.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (PHIA) Data Use Manual. New York, NY. July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radin E, Sachathep K, Hladik W, et al. Population-based HIV Impact Assessments (PHIA) Survey Methods, Response, and Quality in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia. [Publication pending]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.World Health Organization. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/audit-the-alcohol-use-disorders-identification-test-guidelines-for-use-in-primary-health-care.

- 25.Gottert A, Pulerwiltz J, Heck CJ, et al. Creating HIV risk profiles for men in South Africa: a latent class approach using cross-sectional survey data. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(S2):e25518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlongwa M, Mashamba-Thompson T, Makhunga S, et al. Barriers to HIV testing uptake among men in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. African Journal of AIDS Research 2020;19(1):13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treves-Kagan S, El Ayadi AM, Pettifor A, et al. Gender, HIV Testing, and Stigma: The association of HIV testing behaviors and community-level and individual-level stigma in rural South Africa differ for men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2017; 21:2579–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan MC, Rosen AO, Allen A, et al. Falling short of the First 90: HIV Stigma and HIV Testing in the 90–90-90 Era. AIDS Behav. 2020. 24: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards JK, Arimi P, Ssengooba F, et al. Improving HIV outreach testing yield at cross-border venues in East Africa. AIDS. 2020;34(6):923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramphalla P Men’s clinics bring health services closer to men in Lesotho. 2018. Elizabeth Glazer Pediatric AIDS Foundation; (Accessed on Jan 13, 2021) https://www.pedaids.org/2018/09/05/mens-clinics-bring-health-services-closer-to-men-in-the-mountainous-kingdom-of-lesotho/. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro AE, van Heerden A, Krows M, et al. An implementation study of oral and blood-based HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men in rural and peri-urban KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 3(S2):e25514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PEPFAR. PEPFAR 2020 country operational plan guidance for all PEPFAR countries. Washington, DC: US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; 2020. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/COP20-Guidance_Final-1-15-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]