Abstract

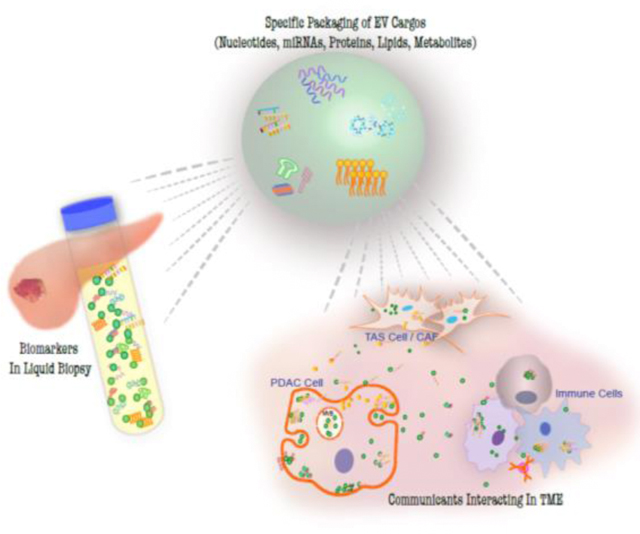

Virtually all cells release various types of vesicles into the extracellular environment. These extracellular vesicles (EVs) transport molecular cargoes, performing as communicants for information exchange both within the tumor microenvironment (TME) and to distant organs. Thus, understanding the selective packaging of EV cargoes and the mechanistic impact of those cargoes - including metabolites, lipids, proteins, and/or nucleic acids - offers an opportunity to increase our knowledge of cancer biology and identify EV cargoes that might serve as cancer biomarkers in blood, saliva, or urine samples. In this review, we collect and organize recent advances in this field with an emphasis on pancreatic cancer (pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PDAC) and the concept that cells selectively package cargo into EVs. These studies demonstrate PDAC EV cargoe signals to reprogram and remodel the TME and impact distant organs. EV cargoes identified as potential PDAC diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers are summarized.

Keywords: pancreatic adenocarcinoma, extracellular vesicles, tumor microenvironment, early detection, paracrine signaling, biomarkers

Graphical Abstract

1. The pathophysiology of PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is lethal with a 5-year survival of 8%, and is predicted to become the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality by the year 2030[1]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) constitutes approximally 95% of pancreatic cancer. It is characterized by an extensive desmoplastic reaction to the transformed ductal cells. This desmoplasia represents the expansion and infiltration of various cell lineages, the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), and collectively is defined as tumor associated stroma (TAS); this host reaction can represent up to 80% of the overall tumor volume.

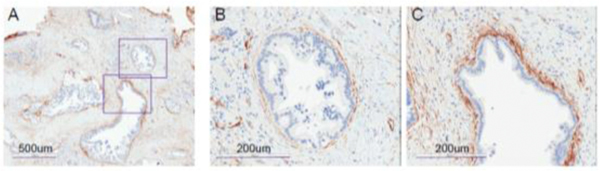

Within this PDAC tumor microevironment (TME), quiescent pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are activated into cancer associated fibrobolasts (CAF), characterized by α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression. Strongly positive α-SMA stromal cells are immediately adjacent to the transformed epithelial cells (figure 1), while other CAFs that stain low in α-SMA but high in IL-6 are distributed diffusely throughout the TME and are pro-inflammatory. These pro-inflammatory CAFs promote tumor growth while the strongly α-SMA positive CAFs likely restrict growth[2].

Figure 1. In PDAC microenvironment where tumors are encircled by SMA+ stromal cells.

Images are immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of a typical PDAC tissue section for α-SMA expression. (A) With 5x objective. The two square areas are enlarged with 20x objective and shown in (B) and (C).

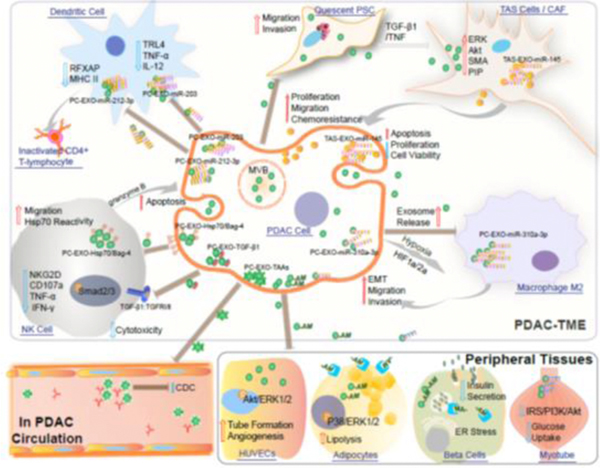

The PDAC TME is also composed of extracellular matrix (ECM), endothelial cells, and immune cells. A number of immune cells infiltrate the TME fostering tolerance[3]. These include myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. The macrophages predominantly exhibit a M2, immunosuppressive, phenotype[4]. Further, there are relatively low numbers of infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells[5]. Finally, the PDAC TME also demonstrates paucity of dendritic (DC) and natural killer (NK) cells, [6, 7]. This review focuses on the present understanding of EV cargos as cell-to-cell communicants, their ability to influence biology in remote organs evidenced by their presence in the circulation (further discussed in section 3 of this review and depicted in figure 2), and their potential value as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers.

Figure 2. Incorporation of EVs in cell-cell communication in PDAC TME and beyond.

EVs released from PDAC and TAS cells effecting PDAC biology via delivering molecular cargos to neighbor cells in TME and in circulation, as well as to peripheral tissues.

2. Incorporation of EVs in cell-cell communication in PDAC TME

As above, PDAC is characterized by an extensive desmoplastic reaction to the tumor. The active stroma surrounding pancreatic cancer cells consists predominantly of myofibroblast-like cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), (which in our previously published work were termed ‘tumor-associated stromal cells’, TAS), as well as other mesenchyma-derived cells including altered immune surveillance. Figure 2 depicts the EV involvement and interactions occurring in the PDAC TME, both locally and in circulation.

2.1. PDAC exosomes activate pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs)

CAFs are largely recognized as activated PSCs, which are characterized by the loss of vitamin A-rich inclusion droplets and gain of α-SMA expression. The leading hypothesis concerning this transition is that PDAC cells drive quiescent pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) activation, provoking profibrogenic activities[8]. While the mechanisms driving stromal formation are likely complex, PDAC-derived exosomes likely contribute; PDAC-derived exosome treatment of primary cultures of human PSCs stimulated their proliferation and migration, as well as up-regulation of ERK, Akt, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA, and fibrosis-related genes including procollagen type I C-peptide. Transcriptome analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis further suggested that induction of PSCs by PDAC-derived exosomes may be under the regulation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF- β1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)[9].

2.2. The contrasting effects of stroma-derived exosomes

While human, pancreas-derived primary CAF cultures remain a challenge in terms of preserving the in vivo stromal characteristics, as well as population purity[8, 10], there is a large body of evidence regarding the impact of CAFs on PDAC cells in vitro. These cells appear to be dynamic players in intercellular communication in the PDAC TME, and this communication fosters PDAC progression. With respect to EV-mediated communication within the TME, EVs derived from CAF cells appear to serve a pro-tumorigenesis role by inducing cancer cell proliferation, migration, chemokine gene expression and chemoresistance[11–13]. In addition, metabolites such as amino acids, lipids and TCA cycle intermediates contained in CAF-derived exosomes can be utilized by cancer cells for central carbon metabolism, as a mechanism to cope with nutrient deprivation [14]. In contrast, in vivo stromal depletion strategies paradoxically led to accelerated progression of PDAC in murine models[15], and clinical trials of stromal disruption have led to similar concerns [16]. CAF-derived exosomes cargo a number of miRNAs with putative tumor suppressive functions previously described in pancreatic or other solid tumors. Our group identified increased levels of tumor suppressive miR-145 and miR-199 family in CAF-derived exosomes and when these exosomes were applied to PDAC cells in culture, they were capable of inducing PDAC cell apoptosis[17, 18]. Thus, CAF-derived exosomes can also mediate a tumor suppressive effect.

2.3. PDAC-derived exosomes influence tumor tolerance

Tumor-derived exosomes also play a role in intracellular communication with the immune system, both in the TME and in circulation. Tumor-derived exosomes contain miRNAs capable of inducing immune tolerance via transfer of regulatory molecules to antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DC). Zhou et al. reported PDAC exosomal miR-203 contributed to dysfunction of DCs by downregulating the expression of TLR4 and downstream cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-12 (IL-12) in DCs[19]. Ding et al. reported that PDAC exosomes transfer miR-212–3p into DC, suppressing the expression of regulatory factor X-associated protein (RFXAP), an important transcription factor for MHC II[20].

Recently, Capello et al. provided novel insights into a possible immune escape mechanism mediated through PADC-derived exosomes that mitigated antibody-modulated immune responses. A significant enrichment of exosomes bound to immunoglobulin (Ig) was found in the circulation of PDAC patients compared to matched controls, suggesting the possibility that intact exosomes from PDAC patients may be bound to Ig in circulation. Using LC-MS/MS analysis, a significant enrichment of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) was observed in exosomes from PDAC. Thus, PADC exosomes, by exposing B-cell epitopes, may exert a decoy function and induced a dose-dependent inhibition of PDAC serum-mediated, complement-dependent cytotoxicity directed at cancer cells[21].

PDAC-derived exosomes have also been reported to disrupt natural killer (NK) cell functions. Zhao et al. showed that PDAC-EVs deliver TGF-β1 to the surface of NK cells upon binding to the TGFβ receptors (TGFβRl/ll). Activation of TGFβRl/ll by TGF-β1 induced the phosphorylation of serine/threonine residues and triggered phosphorylation of Smad2/3. Phosphorylated-Smad2/3 then translocated to the nucleus and regulated gene transcription by down-regulation of NKG2D, CD107a, TNF, INF, CD71, and CD98 in NK cells, and impaired ability to uptake glucose, finally resulting in attenuated NK cell cytotoxicity against PDAC stem cells[22].

In contrast to these studies, Gastpar et al. reported an example of cancer exosome initiated apoptosis in tumors through activation of NK cells. The authors describe a subline of human PDAC cells that present heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70)/Bag-4 on their plasma membranes and secrete Hsp70/Bag-4 surface-positive exosomes. By incubating these exosomes with NK cells in culture, they found that Hsp70/Bag-4 positive exosomes are highly efficient in stimulating migration and eliciting Hsp70 reactivity in NK cells. Hsp70/Bag-4 positive exosomes were also able to induce the release of granzyme B, thus initiating apoptosis in tumors[23].

Finally, exosomes may be potential candidates as tumor vaccines because of their expression of abundant immune-regulating proteins. Que et al. depleted miRNAs from PDAC-derived exosome lysates, but retained all the proteins including attractin, complement proteins C3, C4 and C5, integrin, and actotransferrin. These proteins are known to play roles in lymphocyte activation, cell adhesion, immune regulation, or tumor inhibition. Furthermore, miRNA-depleted exosome proteins more effectively activated dendritic cell / cytokine-induced killer cells (DC/CIKs), leading to a higher killing rate of PDAC cells[24].

2.4. PDAC-derived exosome in hypoxia and angiogenesis, and metabolism

The TME of PDAC is a hypoxic environment, and hypoxia may impact PDAC cell exosome secretion[25]. A recent study demonstrated that iR-301a-3p is highly-expressed in exosomes derived from PDAC cells maintained in hypoxic conditions. This exosome cargo polarized macrophages to the M2 phenotype in a HIF1a or HIF2a–dependent manner. These M2 macrophages subsequently facilitate the migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of PDAC cells.

Second, higher rates of angiogenesis in PDAC specimens have been associated with a poor prognosis [26]. PDAC-derived exosomes can be taken up by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in a dynamin-dependent manner. This uptake alters gene expression in the HUVECs and promotes phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and dynamin-dependent endocytosis [27].

FInally, PDAC-derived exosomes can impact metabolism. Sagar et al. reported exosomes from patient-derived cell lines and from the plasma of PDAC patients contained adrenomedullin. When exposed to human adipocytes, these exosomes induced lipolysis via activated p38 and extracellular signal-regulated ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases[28]. PDAC-derived exosomes have also been observed to deliver adrenomedullin to beta cells, leading to the inhibition of insulin secretion[29]. In murine in vitro experiments, Wang et al. demonstrated that PDAC-derived exosomes readily entered C2C12myotubes, induced insulin resistance, and PI3K/Akt signalling, thus triggering lipidosis and glucose intolerance of C2C12 cells[30].

3. Discovery of EV cargos as biomarkers – clinical tools for PDAC management

3.1. Challenge of PDAC early detection

Despite recent improvements in response rates to new chemotherapy regimens, the overall 5-year survival rate for PDAC, inclusive of all stages, remains a dismal 8%. However, the 5-year survival is 34% for the 15% of patients diagnosed with local disease that are surgical candidates. In contrast, the 5-year survival rate is only 3% for PDAC patients who are diagnosed with synchronous metastasis[31]. Thus, earlier diagnosis of PDAC is critical to efforts to improve outcomes. Coupled with the attraction of noninvasive, “liquid” biopsies and the presence of tumor-derived EVs in those samples, the race for discovery of clinically valuable, EV-based biomarkers found in body fluids is on.

One recently discovered, promising exosome cargo is Glypican-1 (GPC1), a cell surface proteoglycan, that was detected in GPC1+ circulating exosomes (crExos) from the serum of patients with PDAC. Thre presence of GPC1+cr Exos unambiguously distinguished healthy subjects and patients with a benign pancreatic disease from patients with early- stage pancreatic cancer, with absolute specificity and sensitivity [32]. Following this observation, GPC1 expression in PDAC exosomes was confirmed, thus highlighting its potential value in early PDAC diagnosis[33]. However, in other studies [34, 35], the presence of crGPC1-containing exosomes were unable to distinguish PDAC patients from benign pancreatic disease using crExos GPC1 levels. Yang et al. recently reported significantly improved sensitivity and specificity when using a panel of five markers (EGFR, EPCAM, MUC1, GPC1 and WNT2) for PDAC detection[36].

3.2. Sample sources for biomarker discovery

Biofluids are rich sources of EV and offer the potential for noninvasive liquid biopsies. EVs have been successfully isolated from several biofluids including serum / plasma, urine, bile, saliva, synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, peritoneal lavage fluid, semen, and amniotic fluid[37–47]; there has been a significant focus on EVs in serum and plasma[48–51]. Biomarkers in saliva may also possess discriminatory power for the early detection of PDAC [52], and miR-1246 and miR-4644 in salivary exosomes have been identified as candidate biomarkers in the broader sense of pancreatobiliary cancers[53]. Fecal miRNAs may differentiate PDAC patients from healthy controls[54], but there is limited data regarding EV isolation from stool samples[55]. Osteikoetxea, et al. recently detected mucin-family rich EVs from PDAC pancreatic fluid [56]. Given the direct contact with the tumor and its microenvironment, pancreatic ductal fluid has the inherent advantage of potential enrichment of proteins from both epithelia and stroma. However, enzymatic degradation of biomarkers by endogenous pancreatic enzymes and the requirement for invasive, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography negatively impact enthusiasm for this source of biomarkers[57].

3.3. Innovation for PDAC-derived EV isolation

One major technical challenge for the clinical application of EV biology relies on improved EV isolation methods. Current techniques have not met practical diagnostic requirements in terms of affordability, rapidity, and robustness. As an example of new technologies aimed to overcome these limitations, Lewis et al. designed an alternating current electrokinetic microarray chip device to capture and concentrate extracellular vesicles directly from small samples of whole blood, plasma, or serum (30–50 μL) within 15 min. With subsequent on-chip immunofluorescence analysis, the authors further demonstrated elevated exosomal levels of GPC1 and CD63 in PDAC patients compared to controls[50].

Li et al. designed a multiplexed plasmonic immune-capture assay in combination with Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) nano-tag technology. This chip, coupled with MIF-, GPC1-, and EGFR-antibodies, demonstrated the ability to detect PDAC-specific exosomes from as little as 2 μL of a clinical sample of serum[58]. The use of SERS for exosome isolation and detection is on the rise; Pang et al. used a modified dual-SERS biosensor to successfully detect higher levels of miR-10b in plasma exosomes from PDAC patients, as compared to controls[59]. Carmicheal et al. applied label-free SERS followed by principal component differential function analysis to characterize serum exosomes as originating from PDAC patients or healthy individuals with up to 90% accuracy[60]. Despite the promising of these new technologies, the rigor and reproducibility of these assays require further validation prior to routine clinical /use.

3.4. PDAC EV Cargoes

Multiple types of EV cargoes such as DNA, RNA, miRNA, protein, lipid and metabolites all have been reported associated with the disease of PDAC. In Table 1, we summarize the hitherto reported EV cargoes related in PDAC diagnostic and prognostic studies.

Table 1.

EV cargos discovered as biomarkers for PDAC

| Cargo Types | Gene ID | Sample Types | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | KRAS | Plasma | Digital PCR | KRASG12D (39.6% vs 2.6%) in comparing 48 PDAC patients to 114 healthy controls[62]. Mutant KRAS identified in 7.4%, 66.7%, 80%, and 85% of agematched controls, localized, locally advanced, and metastatic PDAC patients respectively. In the validation cohort, mutant KRAS detected in 43.6% of early-stage PDAC patients and 20% of healthy[63]. |

| p53 | Plasma | TP53R273H (4.2% vs 0%) in comparing 48 PDAC patients to 114 healthy controls[62]. | ||

| RNA | GPC1 | Serum | IG-TEM PCR |

KRAS mutation of exo-mRNA detected in all 15 GPC1+ crExos, identical to tumor; Wild-type KRAS mRNA found both in GPC1+ and GPC1- crExos[32]. |

| microRNA | miR-21 | Serum | RT-PCR | Higher in PDAC than in the normal and groups, not significantly correlated with PDAC differentiation and tumor stage[49]. miR-21 was identified as a candidate prognostic factor for OS and chemo-resistance[67]. |

| miR-191 miR-451 |

Serum | Next-generation sequencing analysis | Up-regulated in patients with PDAC and IPMN compared to controls[67]. | |

| miR-17–5p | Serum | RT-PCR | High levels of miR-17–5p were significantly correlated with metastasis and advanced stage of PDAC[49]. | |

| miR-222 | Plasma | RT-PCR | High and significantly correlated to tumor size and TNM stage, an independent risk factor for PDAC patient survival[68]. | |

| miR-23b-3p | Serum | RT-PCR | Higher in serum samples from PDAC patients as compared to those from healthy controls and CP patients[69]. | |

| miR-451a | Plasma | Microarray expression profiling; TaqMan miRNA validation |

Upregulated in the stage II patients who showed recurrence after surgery, associated with tumor size and stage, OS and DFS[70]. | |

| miR-10b | Plasma | Dual-SERS biosensor | Levels in PDAC samples about 59-fold higher than normal, 6fold higher than samples of CP patients (n=5 for each group)[59]. | |

| miR-1246 miR-4644 miR-3976 miR-4306 |

Serum | Sucrose-gradient centrifugation/qRT-PCR | Significantly upregulated in 83% of PDAC but rarely in control groups, with sensitivity of 0.81 and specificity of 0.94[48]. | |

| miR-1246 miR-4644 |

Saliva | Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (Invitrogen)/ RT-qPCR | The relative expression ratios significantly higher in the pancreatobiliary tract cancer group (n=12) than control group (n=13)[53]. | |

| Protein | ZIP4 | Serum | ELISA | Higher in the malignant group than in the benign and normal groups [71]. |

| CD63 GPC1 |

Whole blood, Plasma, Serum | AC electro-kinetic microarray chip | From Plasma of PDAC (N = 20), BPD (N = 7), healthy (N = 11). GPC1 in both PDAC and BPD elevated compared to healthy. No statistically difference between BPD and PDAC. CD63 in PDAC elevated compared to healthy controls, but not significantly different to BPD. No differences in either protein between stage N0 and N1 PDAC samples. Bivariate analysis of GPC1/CD63 for predicting PDAC vs healthy is 98.9% and vs BPD is 81.2%[50]. | |

| GPC1 | Serum | Flow analysis | GPC1 crExos correlate with tumor burden and the survival of pre- and post-surgical patients. Comparing patients with stage I– IV pancreatic cancer to healthy donors and patients with BPD, sensitivity and specificity of 100%, and with a positive and negative predictive value of 100%[32]. | |

| MIF | Plasma | ELISA Antibody-based SERS immunoassay |

POD (progression of disease) patients expressed significantly higher levels compared with NED (with no evidence of disease 5 years post-diagnosis) patients and healthy control subjects[72]. Using 2 μL serum, it discriminated PDAC (n = 71) from healthy (n = 32); and the sensitivity of 95.7% for early-stage (P1– 2) versus P3 stage[58]. | |

| CLDN4 EpCAM CD151 LGALS3BP HIST2H2BE HIST2H2BF |

Plasma | Designed immune-capture assay | By comparing to total exosomes (w/o capture enrichment), the mutant KRAS exoDNA detection increased from 32.7% (17/52), 50% (15/30), and 51.8% (28/54) to 70.6% (12/17), 71.4% (5/7), and 76.9% (10/13) in resectable, locally advanced, and metastatic disease, respectively[51]. | |

| CEACAMs TNC MMP7 LAMB3/C3 |

Pancreatic duct fluid | Ultracentrifugation/ mass spectrometry | Higher among patients with PDAC (n = 13) compared to IPMN (n = 8) and BPD (n = 5)[73]. | |

| Mucins HSP90 alpha CFTR MDR1 Septin-2 Matrilysin |

Pancreatic juice | Mass spectrometry Flow cytometry | 41.8%, 48.4% and 50.1% of the identified proteins were unique to the different size-based EV fractions of patients with CP, PHAC and A-AC, respectively. Mucin and several proteins detected exclusively in pancreatic juice EVs of PH-AC[56]. | |

| Lipid | LysoPC 22:0 PC (P-14:0/22:2) PE (16:0/18:1) |

Serum | LC-MRM-MS untargeted lipidomic analysis screening; LC-MRM-MS targeted lipid quantification validation | Associated with tumor stage, CA19–9, CA242 and tumor diameter; PE also associated with OS[80]. |

OS (overall survival); DFS (disease-free survival rates); CP (chronic pancreatitis); BPD (benign pancreatic disease); IPMN (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm); crExos (circulating exosomes); LC-MRM-MS (liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometric).

DNA:

DNA cargo in exosomes lacks of unified stature with limited reports. Kahlert et al. reported that exosomes contain >10-kb fragments of double-stranded genomic DNA. The authors claimed detected mutations in KRAS and p53 in exosomes derived from PDAC cell lines and serum from patients with PDAC[61]. Circulating exosomal DNA carrying mutations in KRAS and p53 were also confirmed in serum samples from PDAC patients[62] and mutant KRAS in exoDNA from PDAC plasma including early stage patients has been detected. While these data suggest the potential of determine genomic DNA mutations for PDAC detection, it must be noted that exosomal KRAS mutation is also present in a substantial minority of healthy samples (~7.4%)[63].

Within the context of refining EV subtypes, Jeppesen et al. provided evidence that extracellular dsDNA and DNA-binding histones are not present in exosomes or any other types of small EV (sEV), but co-localize with CD63- and LC3B-positive amphisomes, proposing a model of active secretion of cytoplasmic DNA and histones through an autophagy- and MVE-dependent, but exosome-independent mechanism(s)[64]. Additional studies are needed to determine whether this discrepancy is due to cell type specificity, as differences in exoDNA packaging among different cancer cells has been observed[65].

RNA and miRNA:

All types of RNA, including messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), and long intergenic non-protein coding RNA (lincRNA) have been documented in Exocarta (http://www.exocarta.org). In PDAC, Mole et al. reported that in GPC1+ crExos from 15 PDAC patients’ serum, mutant oncogenic KRAS was identified in all samples detected by quantitative PCR, and their mutations corresponded to those detected in primary PDAC tumor samples, while as wild-type KRAS mRNA were found both in GPC1+ and GPC1-crExos[32].

miRNA appears to be an important molecular cargo, and its functional role in the regulation of the tumor microenvironment has been increasingly studied. Abundant, mature miRNAs detected in exosomes, when engulfed by recipient cells, provide an efficient mechanism for immediate posttranscriptional gene expression without the need for further processing. Exosomes derived from cancer cells or from the sera of breast cancer patients also contain the RISC loading complex proteins, Dicer, TRBP, and AGO2, for processing pre-miRNAs into mature miRNAs. This capacity for cell-independent miRNA biogenesis is thought to be cancer specific and not a property of normal-cell-derived exosomes[66]. Potential miRNAs identified as biomarkers for PDAC diagnosis and prognosis include miR-21, miR-191, miR-451, miR-17–5p, miR-222, miR-23b-3p, miR-451a, miR-10b, miR-1246, miR-4644, miR-3976, and miR-4306. These miRNAs have been identified in sera or plasma[49, 67–70], and miR-1246 and miR-4644 have been detected in saliva samples[53] (Table 1).

Proteins and post-translational modification:

Over forty-thousand entries report a total of 9769 exosome proteins in the Exocarta database. Protein extraction from EVs has been used successfully for immune-based analysis, including immunoblotting, flow cytometry and proteomic profiling analyses. LC/MS/MS has been successful for biomarker discovery, followed by ELISA or flow cytometry analysis for validation. Potential biomarkers for PDAC include ZIP4, CD63, GPC1, MIF, CLDN4, EpCAM, CD151, LGALS3BP, and HIST2H2BE/F from serum or plasma[51, 71, 72], and CEACAMs, TNC, MMP7 and LAMB3/C3 from pancreatic duct fluid, as well as Mucins, HSP90 alpha, CFTR, MDR1, Septin-2, Matrilysin from pancreatic extracts[56, 73].

Surface protein patterns on exosomes reflect that of the tumor cells from which they originate. EV surface molecules are critical for interactions in the TME, as well as biomarker candidacy (reviewed in [74]). Using protein profiling to identify the specific EV “surfaceome”, coupled with in silico analysis could increase our knowledge of interaction of exosomes within the TME and possibly identify cancer-associated EV cargos useful for diagnostic purposes[51, 58, 75]. Both studies from Li et al. and Castillo et al. demonstrated promising, antibody-based, PDAC specific exosomes using MIF and a panel of six surface proteins (CLDN4 / EPCAM / CD151 / LGALS3BP / HIST2H2BE / HIST2H2BF) respectively[51, 58].

Post-translational modification of proteins such as phosphorylation plays an important role in protein function and alters cellular signaling pathways. It is known that protein phosphorylation states are associated with the phenotypes of cancer initiation and progression. Thus, defining the EV phosphoproteome could also lead to novel biomarker discovery. Using neutral loss scanning with high-stringency target-decoy analysis, Gonzales et al. identified 19 phosphorylation sites corresponding to 14 phosphoproteins in human urinary exosomes, including some novel discovered phosphorylation sites[76]. Inhibition of oncogenic forms of EGFR enhanced release of EVs, as did phosphorylation of EV-contained proteins purified from mice bearing human xenografts [77]. With in vitro experimentation, overexpression of EGFRvIII induces widespread changes in the EV phosphoproteome, including increased P-EGFR. Differential phosphorylation of exosomal proteins were also found between isogenic non-invasive and highly-invasive cholangiocarcinoma cells[78].

Lipids and metabolites:

These cargos in EVs are the least studied. The lipid composition of EVs from the PDAC cell line SOJ-6 has been reported as abundant in cholesterol and sphingomyelin, but depleted in phosphatidylserine[79]. Tao et al. reported dysregulated lipid composition between the serum exosomes of PDAC patients and healthy controls; LysoPC (Lysophosphatidylcholine), PC (Phosphatidylcholine) and PE (Phosphatidyl-ethanolamine) were associated with tumor stage, CA19–9, CA242 and tumor diameter. In addition, PE was also found to be significantly correlated with overall survival[80].

4. Final remarks and future directions

The last decade has seen a rapid expansion of interest in EVs studies, especially in cancer research. In this review, using both fundamental and clinical studies of pancreatic cancer, we have demonstrated that: 1) EV cargo packaging is a selective process, and different cell types specifically chose their own “missioner” cargos and package them into different types of EVs; 2) the tumor microenvironment provides a battlefield for EV cargos from different types of cells to perform unique roles, fostering a dynamic pro-tumor / anti-tumor conflict; and 3) EV components, shed into the TME and into the circulation are a rich source for biomarker discovery.

Rigorous, reproducible isolation of EVs is fundamental to move clinical applications forward and this technology remains a major challenge. With the increased awareness of the complexity of EV subtypes, all current protocols for exosome purification actually co-purify different subtypes of EVs[64]. While ultracentrifugation is still the most common and acceptable technique to separate size and density based EVs, it has limited use for the handling of small volume clinical samples. Immune-capture based techniques require the identification of membrane proteins that effectively distinguish cancer EVs from normal. Zaborowski, et al. set an example of in silico membrane protein identification in the practice of ovarian tumors [75]. The success of such strategies is subject to the choice and quality of the antibody, as well as the affinity to the epitopes for successful isolation.

Mechanisms driving how EV cargos are selected and packaged remain unclear. Quantitative measurement of enhanced or enriched EV cargos is another remaining challenge, due to the lack of normalization standards. Most studies report proteins present within the EVs without comparing concentration / abundancy to the source cells from which they were derived. In our recent work, we applied the analytic model of ANalysis of Composition Of Microbiomes (ANCOM) to quantitatively compare protein levels of exosomes to their parental cells. We successfully identified 34 proteins that were specifically associated with pancreatic cancer, as predicted by IPA including GPC1 and ANXA1[33]. This unbiased analytic method fits the scenario for quantitiative exosome cargo comparisons. Additional studies are needed to validate the ANCOM model as a method to quantify EVs from different cell subtypes and lineage.

Finally, TME released EVs from the stroma may be as important for tumor biology as those released by tumor cells. As noted, both tumor and stromal cells secrete / release EVs into the local microenvironment and into the circulation[73], as detected in pancreatic duct fluid. Stromal-derived EVs as a source for cancer biomarker discovery is yet underdeveloped. Defining EVs from tissue samples was first reported on brain tissue, and recently applied to study the TME of colorectal cancers and adjacent normal mucosa[64]. In short, the potential for EVs and their cargos as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers remains in its infancy, but their potential role in cancer therapeutics is undeniable.

Highlights:

EV cargo packaging is not a random process, but is selectively controlled.

In the tumor microenvironment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, EV released by both cancer cells and cancer-associated non-cancer cells (mainly CAFs) transport their cargos as communicants and thus impact cancer biology.

EV cargos, including DNA, mRNA, miRNA, proteins, and lipids are potential biomarkers residing in liquid biopsies from plasma / serum, saliva and pancreatic tissue extracts.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported (SJH), in part, by NIH 1UO1DK108320.

Abbreviations:

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- EV

extracellular vesicles

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- MVs

microvesicles

- TAS

tumor associated stroma

- PSC

pancreatic stellate cell

- CAF

cancer associated fibroblast

Biographies

Song Han earned her Ph.D. in Microbiology and Immunology from Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (China), and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Cardiff University College of Medicine (U.K). She is currently a Research Scientist in the Department of Surgery at the University of Florida. Her research interests focus on the roles of extracellular vesicles in pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment, as well as developing novel, effective biomarkers for early diagnosis.

Patrick Underwood is a general surgery resident in the Department of Surgery at the University of Florida. He graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School. He is currently completing a post-doctoral fellowship. His interests include the pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment, cancer-induced cachexia, and effective therapies for pancreatic cancer.

Steven J. Hughes is the Edward M. Copeland, III Professor of Surgery at the University of Florida. He serves as Chief, Division of Surgical Oncology and Vice-Chair, General Surgery. After graduating from Mayo Medical School, He completed a general surgery residency, a surgical critical care residency, and a NIH-Surgical Oncology research fellowship at the University of Michigan. His clinical expertise is minimally invasive approaches to hepato-pancreato-biliary diseases including the performance of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure). Dr. Hughes’ NIH-funded research focuses on the translation of pancreatic cancer biology into clinical practice. His current research focus is the role of the tumor microenvironment in modulating innate and adaptive immunity, cachexia, and the response of pancreatic cancer to anti-tumor therapies. He has authored over 100 peer-reviewed manuscripts and edited a major hepato-pancreato-biliary surgical text. He holds three US/European patents and previously served on the scientific advisory board of a publicly held, molecular diagnostics company.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer Statistics, 2017, CA Cancer J Clin 67(1) (2017) 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ohlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, Corbo V, Oni TE, Hearn SA, Lee EJ, Chio II, Hwang CI, Tiriac H, Baker LA, Engle DD, Feig C, Kultti A, Egeblad M, Fearon DT, Crawford JM, Clevers H, Park Y, Tuveson DA, Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer, J Exp Med 214(3) (2017) 579–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Delitto D, Wallet SM, Hughes SJ, Targeting tumor tolerance: A new hope for pancreatic cancer therapy?, Pharmacol Ther 166 (2016) 9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang AB, Qian YG, Ye Z, Chen HY, Xie HY, Zhou L, Shen Y, Zheng SS, Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote M2 polarization of macrophages in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer Medicine 6(2) (2017) 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, Iwasaki M, Kosuge T, Kanai Y, Hiraoka N, Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer, British Journal of Cancer 108(4) (2013) 914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dallal RM, Christakos P, Lee K, Egawa S, Son YI, Lotze MT, Paucity of dendritic cells in pancreatic cancer, Surgery 131(2) (2002) 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Van Audenaerde JRM, Roeyen G, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Peeters M, Smits ELJ, Natural killer cells and their therapeutic role in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review, Pharmacology & Therapeutics 189 (2018) 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Erkan M, Adler G, Apte MV, Bachem MG, Buchholz M, Detlefsen S, Esposito I, Friess H, Gress TM, Habisch HJ, Hwang RF, Jaster R, Kleeff J, Kloppel G, Kordes C, Logsdon CD, Masamune A, Michalski CW, Oh J, Phillips PA, Pinzani M, Reiser-Erkan C, Tsukamoto H, Wilson J, StellaTUM: current consensus and discussion on pancreatic stellate cell research, Gut 61(2) (2012) 172–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Masamune A, Yoshida N, Hamada S, Takikawa T, Nabeshima T, Shimosegawa T, Exosomes derived from pancreatic cancer cells induce activation and profibrogenic activities in pancreatic stellate cells, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 495(1) (2018) 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Han S, Delitto D, Zhang DY, Sorenson HL, Sarosi GA, Thomas RM, Behrns KE, Wallet SM, Trevino JG, Hughes SJ, Primary outgrowth cultures are a reliable source of human pancreatic stellate cells, Laboratory Investigation 95(11) (2015) 1331–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Takikawa T, Masamune A, Yoshida N, Hamada S, Kogure T, Shimosegawa T, Exosomes Derived From Pancreatic Stellate Cells: MicroRNA Signature and Effects on Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Pancreas 46(1) (2017) 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Richards KE, Zeleniak AE, Fishel ML, Wu J, Littlepage LE, Hill R, Cancer-associated fibroblast exosomes regulate survival and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells, Oncogene 36(13) (2017) 1770–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Y.Z. Fang W; Rong Y; Kuang T; Xu X; Wu W; Wang D; Lou W, Exosomal miRNA-106b from cancer-associated fibroblast promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer, Experimental Cell Research (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhao H, Yang L, Baddour J, Achreja A, Bernard V, Moss T, Marini JC, Tudawe T, Seviour EG, San Lucas FA, Alvarez H, Gupta S, Maiti SN, Cooper L, Peehl D, Ram PT, Maitra A, Nagrath D, Tumor microenvironment derived exosomes pleiotropically modulate cancer cell metabolism, Elife 5 (2016) e10250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, Mirek ET, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, Dekleva EN, Saunders T, Becerra CP, Tattersall IW, Westphalen CB, Kitajewski J, Fernandez-Barrena MG, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Olive KP, Stanger BZ, Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer Cell 25(6) (2014) 735–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ramanathan RK, McDonough S, Philip PA, Hingorani SR, Lacy J, Kortmansky JS, Thumar J, Chiorean EG, Shields AF, Behl D, Mehan PT, Gaur R, Seery T, Guthrie K, Hochster HS, Phase IB/II Randomized Study of FOLFIRINOX Plus Pegylated Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase Versus FOLFIRINOX Alone in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: SWOG S1313, Journal of Clinical Oncology 37(13) (2019) 1062-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Han S, Gonzalo DH, Feely M, Delitto D, Behrns KE, Beveridge M, Zhang D, Thomas R, Trevino JG, Schmittgen TD, Hughes SJ, The pancreatic tumor microenvironment drives changes in miRNA expression that promote cytokine production and inhibit migration by the tumor associated stroma, Oncotarget 8(33) (2017) 54054–54067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Han S, Gonzalo DH, Feely M, Rinaldi C, Belsare S, Zhai H, Kalra K, Gerber MH, Forsmark CE, Hughes SJ, Stroma-derived extracellular vesicles deliver tumor-suppressive miRNAs to pancreatic cancer cells, Oncotarget 9(5) (2018) 5764–5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhou M, Chen J, Zhou L, Chen W, Ding G, Cao L, Pancreatic cancer derived exosomes regulate the expression of TLR4 in dendritic cells via miR-203, Cell Immunol 292(1–2) (2014) 65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ding G, Zhou L, Qian Y, Fu M, Chen J, Chen J, Xiang J, Wu Z, Jiang G, Cao L, Pancreatic cancer-derived exosomes transfer miRNAs to dendritic cells and inhibit RFXAP expression via miR-212–3p, Oncotarget 6(30) (2015) 29877–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Capello M, Vykoukal JV, Katayama H, Bantis LE, Wang H, Kundnani DL, Aguilar-Bonavides C, Aguilar M, Tripathi SC, Dhillon DS, Momin AA, Peters H, Katz MH, Alvarez H, Bernard V, Ferri-Borgogno S, Brand R, Adler DG, Firpo MA, Mulvihill SJ, Molldrem JJ, Feng Z, Taguchi A, Maitra A, Hanash SM, Exosomes harbor B cell targets in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and exert decoy function against complement-mediated cytotoxicity, Nat Commun 10(1) (2019) 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhao J, Schlosser HA, Wang Z, Qin J, Li J, Popp F, Popp MC, Alakus H, Chon SH, Hansen HP, Neiss WF, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ, Zhao Y, Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Natural Killer Cell Function in Pancreatic Cancer, Cancers (Basel) 11(6) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gastpar R, Gehrmann M, Bausero MA, Asea A, Gross C, Schroeder JA, Multhoff G, Heat shock protein 70 surface-positive tumor exosomes stimulate migratory and cytolytic activity of natural killer cells, Cancer Res 65(12) (2005) 5238–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Que RS, Lin C, Ding GP, Wu ZR, Cao LP, Increasing the immune activity of exosomes: the effect of miRNA-depleted exosome proteins on activating dendritic cell/cytokine-induced killer cells against pancreatic cancer, J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 17(5) (2016) 352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang X, Luo G, Zhang K, Cao J, Huang C, Jiang T, Liu B, Su L, Qiu Z, Hypoxic Tumor-Derived Exosomal miR-301a Mediates M2 Macrophage Polarization via PTEN/PI3Kgamma to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis, Cancer Res 78(16) (2018) 4586–4598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Garcea G, Doucas H, Steward WP, Dennison AR, Berry DP, Hypoxia and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer, ANZ J Surg 76(9) (2006) 830–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chiba M, Kubota S, Sato K, Monzen S, Exosomes released from pancreatic cancer cells enhance angiogenic activities via dynamin-dependent endocytosis in endothelial cells in vitro, Sci Rep 8(1) (2018) 11972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sagar G, Sah RP, Javeed N, Dutta SK, Smyrk TC, Lau JS, Giorgadze N, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Chari ST, Mukhopadhyay D, Pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer exosome-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue, Gut 65(7) (2016) 1165–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Javeed N, Sagar G, Dutta SK, Smyrk TC, Lau JS, Bhattacharya S, Truty M, Petersen GM, Kaufman RJ, Chari ST, Mukhopadhyay D, Pancreatic Cancer-Derived Exosomes Cause Paraneoplastic beta-cell Dysfunction, Clin Cancer Res 21(7) (2015) 1722–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang LT, Zhang B, Zheng W, Kang MX, Chen Q, Qin WJ, Li C, Zhang YF, Shao YK, Wu YL, Exosomes derived from pancreatic cancer cells induce insulin resistance in C2C12 myotube cells through the PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 pathway, Scientific Reports 7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Society AC, Cancer Facts & Figures 2019., Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2019. (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, Fernandez AF, Gammon ST, Kaye J, LeBleu VS, Mittendorf EA, Weitz J, Rahbari N, Reissfelder C, Pilarsky C, Fraga MF, Piwnica-Worms D, Kalluri R, Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer, Nature 523(7559) (2015) 177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Han S, Huo Z, Nguyen K, Zhu F, Underwood PW, Basso KBG, George TJ, Hughes SJ, The Proteome of Pancreatic Cancer-Derived Exosomes Reveals Signatures Rich in Key Signaling Pathways, Proteomics 19(13) (2019) e1800394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Frampton AE, Prado MM, Lopez-Jimenez E, Fajardo-Puerta AB, Jawad ZAR, Lawton P, Giovannetti E, Habib NA, Castellano L, Stebbing J, Krell J, Jiao LR, Glypican-1 is enriched in circulating-exosomes in pancreatic cancer and correlates with tumor burden, Oncotarget 9(27) (2018) 19006–19013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lai X, Wang M, McElyea SD, Sherman S, House M, Korc M, A microRNA signature in circulating exosomes is superior to exosomal glypican-1 levels for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, Cancer Lett 393 (2017) 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yang KS, Im H, Hong S, Pergolini I, del Castillo AF, Wang R, Clardy S, Huang CH, Pille C, Ferrone S, Yang R, Castro CM, Lee H, del Castillo CF, Weissleder R, Multiparametric plasma EV profiling facilitates diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy, Science Translational Medicine 9(391) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Barcelo M, Mata A, Bassas L, Larriba S, Exosomal microRNAs in seminal plasma are markers of the origin of azoospermia and can predict the presence of sperm in testicular tissue, Human Reproduction 33(6) (2018) 1087–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Helwa I, Cai JW, Drewry MD, Zimmerman A, Dinkins MB, Khaled ML, Seremwe M, Dismuke WM, Bieberich E, Stamer WD, Hamrick MW, Liu YT, A Comparative Study of Serum Exosome Isolation Using Differential Ultracentrifugation and Three Commercial Reagents, Plos One 12(1) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hong CS, Funk S, Whiteside TL, Isolation of Biologically Active Exosomes from Plasma of Patients with Cancer, Methods Mol Biol 1633 (2017) 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Street JM, Koritzinsky EH, Glispie DM, Yuen PST, Urine Exosome Isolation and Characterization, Methods Mol Biol 1641 (2017) 413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li L, Masica D, Ishida M, Tomuleasa C, Umegaki S, Kalloo AN, Georgiades C, Singh VK, Khashab M, Amateau S, Li ZP, Okolo P, Lennon AM, Saxena P, Geschwind JF, Schlachter T, Hong K, Pawlik TM, Canto M, Law J, Sharaiha R, Weiss CR, Thuluvath P, Goggins M, Shin EJ, Peng HR, Kumbhari V, Hutfless S, Zhou LY, Mezey E, Meltzer SJ, Karchin R, Selaru FM, Human Bile Contains MicroRNA-Laden Extracellular Vesicles That Can Be Used for Cholangiocarcinoma Diagnosis, Hepatology 60(3) (2014) 896–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Palanisamy V, Sharma S, Deshpande A, Zhou H, Gimzewski J, Wong DT, Nanostructural and Transcriptomic Analyses of Human Saliva Derived Exosome, Plos One 5(1) (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lasser C, Alikhani VS, Ekstrom K, Eldh M, Paredes PT, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Gabrielsson S, Lotvall J, Valadi H, Human saliva, plasma and breast milk exosomes contain RNA: uptake by macrophages, J Transl Med 9 (2011) 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Foers AD, Chatfield S, Dagley LF, Scicluna BJ, Webb AI, Cheng L, Hill AF, Wicks IP, Pang KC, Enrichment of extracellular vesicles from human synovial fluid using size exclusion chromatography, J Extracell Vesicles 7(1) (2018) 1490145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Akers JC, Ramakrishnan V, Kim R, Phillips S, Kaimal V, Mao Y, Hua W, Yang I, Fu CC, Nolan J, Nakano I, Yang Y, Beaulieu M, Carter BS, Chen CC, miRNA contents of cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles in glioblastoma patients, J Neurooncol 123(2) (2015) 205–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tokuhisa M, Ichikawa Y, Kosaka N, Ochiya T, Yashiro M, Hirakawa K, Kosaka T, Makino H, Akiyama H, Kunisaki C, Endo I, Exosomal miRNAs from Peritoneum Lavage Fluid as Potential Prognostic Biomarkers of Peritoneal Metastasis in Gastric Cancer, Plos One 10(7) (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dixon CL, Sheller-Miller S, Saade GR, Fortunato SJ, Lai A, Palma C, Guanzon D, Salomon C, Menon R, Amniotic Fluid Exosome Proteomic Profile Exhibits Unique Pathways of Term and Preterm Labor, Endocrinology 159(5) (2018) 2229–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Madhavan B, Yue SJ, Galli U, Rana S, Gross W, Muller M, Giese NA, Kalthoff H, Becker T, Buchler MW, Zoller M, Combined evaluation of a panel of protein and miRNA serum-exosome biomarkers for pancreatic cancer diagnosis increases sensitivity and specificity, International Journal of Cancer 136(11) (2015) 2616–2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Que RS, Ding GP, Chen JH, Cao LP, Analysis of serum exosomal microRNAs and clinicopathologic features of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, World Journal of Surgical Oncology 11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lewis JM, Vyas AD, Qiu Y, Messer KS, White R, Heller MJ, Integrated Analysis of Exosomal Protein Biomarkers on Alternating Current Electrokinetic Chips Enables Rapid Detection of Pancreatic Cancer in Patient Blood, ACS Nano 12(4) (2018) 3311–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Castillo J, Bernard V, San Lucas FA, Allenson K, Capello M, Kim DU, Gascoyne P, Mulu FC, Stephens BM, Huang J, Wang H, Momin AA, Jacamo RO, Katz M, Wolff R, Javle M, Varadhachary G, Wistuba II, Hanash S, Maitra A, Alvarez H, Surfaceome profiling enables isolation of cancer-specific exosomal cargo in liquid biopsies from pancreatic cancer patients, Ann Oncol 29(1) (2018) 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhang L, Farrell JJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Akin D, Park NH, Chia D, Wong DT, Salivary transcriptomic biomarkers for detection of resectable pancreatic cancer, Gastroenterology 138(3) (2010) 949–57 e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Machida T, Tomofuji T, Maruyama T, Yoneda T, Ekuni D, Azuma T, Miyai H, Mizuno H, Kato H, Tsutsumi K, Uchida D, Takaki A, Okada H, Morita M, miR-1246 and miR-4644 in salivary exosome as potential biomarkers for pancreatobiliary tract cancer, Oncology Reports 36(4) (2016) 2375–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yang JY, Sun YW, Liu DJ, Zhang JF, Li J, Hua R, MicroRNAs in stool samples as potential screening biomarkers for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cancer, American Journal of Cancer Research 4(6) (2014) 663–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Y.Y. Koga M; Moriya Y;Akasu T; Fujita S; Yamamoto S; Matsumura Y, Exosome can prevent RNase from degrading microRNA in feces, Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 2(4) (2011) 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Osteikoetxea X, Benke M, Rodriguez M, Paloczi K, Sodar BW, Szvicsek Z, Szabo-Taylor K, Vukman KV, Kittel A, Wiener Z, Vekey K, Harsanyi L, Szucs A, Turiak L, Buzas EI, Detection and proteomic characterization of extracellular vesicles in human pancreatic juice, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 499(1) (2018) 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ohtsuka T OF, Tanaka M, Diagnostic Investigation Using Pancreatic Juice, Springer, Tokyo: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Li TD, Zhang R, Chen H, Huang ZP, Ye X, Wang H, Deng AM, Kong JL, An ultrasensitive polydopamine bi-functionalized SERS immunoassay for exosome-based diagnosis and classification of pancreatic cancer, Chem Sci 9(24) (2018) 5372–5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pang Y, Wang C, Lu L, Wang C, Sun Z, Xiao R, Dual-SERS biosensor for one-step detection of microRNAs in exosome and residual plasma of blood samples for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, Biosens Bioelectron 130 (2019) 204–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Carmicheal J, Hayashi C, Huang X, Liu L, Lu Y, Krasnoslobodtsev A, Lushnikov A, Kshirsagar PG, Patel A, Jain M, Lyubchenko YL, Lu YF, Batra SK, Kaur S, Label-free characterization of exosome via surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy for the early detection of pancreatic cancer, Nanomedicine-Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine 16 (2019) 88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kahlert C, Melo SA, Protopopov A, Tang J, Seth S, Koch M, Zhang J, Weitz J, Chin L, Futreal A, Kalluri R, Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer, J Biol Chem 289(7) (2014) 3869–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yang S, Che SP, Kurywchak P, Tavormina JL, Gansmo LB, Correa de Sampaio P, Tachezy M, Bockhorn M, Gebauer F, Haltom AR, Melo SA, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R, Detection of mutant KRAS and TP53 DNA in circulating exosomes from healthy individuals and patients with pancreatic cancer, Cancer Biol Ther 18(3) (2017) 158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Allenson K, Castillo J, San Lucas FAS, Scelo G, Kim DU, Bernard V, Davis G, Kumar T, Katz M, Overman MJ, Foretova L, Fabianova E, Holcatova I, Janout V, Meric-Bernstam F, Gascoyne P, Wistuba I, Varadhachary G, Brennan P, Hanash S, Li D, Maitra A, Alvarez H, High prevalence of mutant KRAS in circulating exosome-derived DNA from early-stage pancreatic cancer patients, Annals of Oncology 28(4) (2017) 741–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, Liebler DC, Ping J, Liu Q, Evans R, Fissell WH, Patton JG, Rome LH, Burnette DT, Coffey RJ, Reassessment of Exosome Composition, Cell 177(2) (2019) 428–445 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Thakur BK, Zhang H, Becker A, Matei I, Huang Y, Costa-Silva B, Zheng Y, Hoshino A, Brazier H, Xiang J, Williams C, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Silva JM, Zhang W, Hearn S, Elemento O, Paknejad N, Manova-Todorova K, Welte K, Bromberg J, Peinado H, Lyden D, Double-stranded DNA in exosomes: a novel biomarker in cancer detection, Cell Res 24(6) (2014) 766–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Melo SA, Sugimoto H, O’Connell JT, Kato N, Villanueva A, Vidal A, Qiu L, Vitkin E, Perelman LT, Melo CA, Lucci A, Ivan C, Calin GA, Kalluri R, Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis, Cancer Cell 26(5) (2014) 707–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Goto T, Fujiya M, Konishi H, Sasajima J, Fujibayashi S, Hayashi A, Utsumi T, Sato H, Iwama T, Ijiri M, Sakatani A, Tanaka K, Nomura Y, Ueno N, Kashima S, Moriichi K, Mizukami Y, Kohgo Y, Okumura T, An elevated expression of serum exosomal microRNA-191,−21,−451a of pancreatic neoplasm is considered to be efficient diagnostic marker, Bmc Cancer 18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Li ZH, Tao Y, Wang XY, Jiang P, Li J, Peng MJ, Zhang X, Chen K, Liu H, Zhen P, Zhu J, Liu XD, Li XW, Tumor-Secreted Exosomal miR-222 Promotes Tumor Progression via Regulating P27 Expression and Re-Localization in Pancreatic Cancer, Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 51(2) (2018) 610–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chen DY, Wu XB, Xia M, Wu F, Ding JL, Jiao Y, Zhan Q, An FM, Upregulated exosomic miR-23b-3p plays regulatory roles in the progression of pancreatic cancer, Oncology Reports 38(4) (2017) 2182–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Takahasi K, Iinuma H, Wada K, Minezaki S, Kawamura S, Kainuma M, Ikeda Y, Shibuya M, Miura F, Sano K, Usefulness of exosome-encapsulated microRNA-451a as a minimally invasive biomarker for prediction of recurrence and prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences 25(2) (2018) 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Jin HY, Liu P, Wu YH, Meng XL, Wu MW, Han JH, Tan XD, Exosomal zinc transporter ZIP4 promotes cancer growth and is a novel diagnostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer, Cancer Science 109(9) (2018) 2946–2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, Singh S, Zhang HY, Thakur BK, Becker A, Hoshino A, Mark MT, Molina H, Xiang J, Zhang T, Theilen TM, Garcia-Santos G, Williams C, Ararso Y, Huang YJ, Rodrigues G, Shen TL, Labori KJ, Lothe IMB, Kure EH, Hernandez J, Doussot A, Ebbesen SH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz RE, Matei I, Peinado H, Stanger BZ, Bromberg J, Lyden D, Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver, Nature Cell Biology 17(6) (2015) 816-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zheng J, Hernandez JM, Doussot A, Bojmar L, Zambirinis CP, Costa-Silva B, van Beek EJAH, Mark MT, Molina H, Askan G, Basturk O, Gonen M, Kingham TP, Allen PJ, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Lyden D, Jarnagin WR, Extracellular matrix proteins and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules characterize pancreatic duct fluid exosomes in patients with pancreatic cancer, Hpb 20(7) (2018) 597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Buzas EI, Toth EA, Sodar BW, Szabo-Taylor KE, Molecular interactions at the surface of extracellular vesicles, Seminars in Immunopathology 40(5) (2018) 453–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Zaborowski MP, Lee K, Na YJ, Sammarco A, Zhang X, Iwanicki M, Cheah PS, Lin HY, Zinter M, Chou CY, Fulci G, Tannous BA, Lai CP, Birrer MJ, Weissleder R, Lee H, Breakefield XO, Methods for Systematic Identification of Membrane Proteins for Specific Capture of Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles, Cell Rep 27(1) (2019) 255–268 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Gonzales PA, Pisitkun T, Hoffert JD, Tchapyjnikov D, Star RA, Kleta R, Wang NS, Knepper MA, Large-Scale Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics of Urinary Exosomes, Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 20(2) (2009) 363–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Montermini L, Meehan B, Garnier D, Lee WJ, Lee TH, Guha A, Al-Nedawi K, Rak J, Inhibition of oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor kinase triggers release of exosome-like extracellular vesicles and impacts their phosphoprotein and DNA content, J Biol Chem 290(40) (2015) 24534–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Weeraphan C, Phongdara A, Chaiyawat P, Diskul-Na-Ayudthaya P, Chokchaichamnankit D, Verathamjamras C, Netsirisawan P, Yingchutrakul Y, Roytrakul S, Champattanachai V, Svasti J, Srisomsap C, Phosphoproteome Profiling of Isogenic Cancer Cell-Derived Exosome Reveals HSP90 as a Potential Marker for Human Cholangiocarcinoma, Proteomics 19(12) (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ristorcelli E, Beraud E, Verrando P, Villard C, Lafitte D, Sbarra V, Lombardo D, Verine A, Human tumor nanoparticles induce apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells, FASEB J 22(9) (2008) 3358–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Tao L, Zhou J, Yuan C, Zhang L, Li D, Si D, Xiu D, Zhong L, Metabolomics identifies serum and exosomes metabolite markers of pancreatic cancer, Metabolomics 15(6) (2019) 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]