Abstract

Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many medical providers have turned to telemedicine as an alternative method to provide ambulatory patient care. Perspectives of endocrine surgery patients regarding this mode of healthcare delivery remains unclear. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the opinions and perspectives of endocrine surgery patients regarding telemedicine.

Methods

The first 100 adult patients who had their initial telemedicine appointment with two endocrine surgeons were contacted at the conclusion of their visit. The survey administered assessed satisfaction with telemedicine, the provider, and whether attire or video background played a role in their perception of the quality of care received using a 5-point Likert scale. Differences in responses between new and returning patients were also evaluated.

Results

Telemedicine endocrine surgery patients stated excellent satisfaction with their visit (4.89 out of 5) and their provider (4.96 out of 5). Although there was less consensus that telemedicine was equivalent to in-person or face-to-face clinic visits (4.15 out of 5), patients would recommend a telemedicine visit to others and most agreed that this modality made it easier to obtain healthcare (4.7 out of 5). Attire of the provider and video background did not influence patient opinion in regard to the quality of care they received. Returning patients were more likely to be satisfied with this modality (4.94 versus 4.73, P = 0.02) compared to new patients.

Conclusions

This study shows that telemedicine does not compromise patient satisfaction or healthcare delivery for patients and is a viable clinic option for endocrine surgery.

Keywords: COVID-19, Endocrine surgery, Patient satisfaction, Telemedicine

Introduction

With advances in telecommunications and information technology, telemedicine has gained traction and popularity in the recent decades. Telemedicine allows for healthcare delivery via live interactive video/audio conferencing. This allows the physician to interpret medical data and discuss treatment plans with the patients remotely, eliminating the need for commute and reducing healthcare and operational costs.1 , 2 The COVID-19 pandemic created challenges for patient access to healthcare. The uncertainty surrounding disease transmission limited patients’ ability to attend healthcare visits, especially in elective medical specialties. Adoption of remote virtual healthcare provided an alternative access to patient care, which made this modality particularly useful during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 , 4

Although other medical disciplines have embraced telemedicine for some time, endocrine surgery practices and surgical specialties in general have only recently began adopting this modality in the clinical practice.5 A previous study demonstrated that using telemedicine for postoperative visits was safe and effective for parathyroid surgery patients.6 Other studies have also demonstrated that telemedicine does not compromise safety and allows for similar patient satisfaction scores in certain patient populations.7 However, the use of telemedicine for general follow-up visits and new patient consultations in endocrine surgery has not been studied.

The COVID-19 pandemic created the necessity for patients to have continued access to care and therefore led to the immediate implementation of telemedicine. An important aspect of adoption of new technology in medicine is the assessment of patient satisfaction. Understanding how patients perceive the care they obtain through telemedicine and their satisfaction is necessary prior to widespread adoption of this technology. Additionally, other factors that may affect patient satisfaction including clinician attire and video background have not been studied in a telemedicine setting. Prior studies have shown that attire could affect patients’ perception of the care they receive.8 , 9 Attire or video background during a telemedicine visit may therefore play a role in patient satisfaction. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate whether patients perceive telemedicine in an endocrine surgery practice similar in quality to in-person visits as well as understand various patient opinions and perspectives regarding telemedicine including attire of the provider and video background.

Materials and Methods

As part of a patient satisfaction initiative, the first 100 patients aged 18 and older attending their initial video “Telemedicine Endocrine Surgery” clinic appointment were contacted at the conclusion of their visit. Patients were enrolled in the study between April and August 2020. Initially, telemedicine option was mandatory due to COVID restrictions. However, as restrictions were eased, patients were queried by office staff regarding their preferred visit type. The background and purpose of the survey as well as the patient’s rights as a participant was described to the patients. The patient was asked if they wished to participate, with only those voluntarily agreeing to participate included. Signed written consent was waived as per Institutional Review Board approval. Instead, informed consent was obtained verbally. Patients were emailed prior to their visit detailing instructions on gaining electronic access for their telemedicine encounter. Patients were expected to be logged in 15 min prior to their scheduled appointment and following completion of the clinic encounter were then contacted via phone to complete the survey. The encounter was carried out in the providers’ clinic office and the providers routinely dressed in scrubs as they would for an in-person visit. The survey comprised of a series of questions addressing patient experience, perception of the treating provider, and overall telehealth satisfaction (Supplement Table 1). A modified version of the Utah Telehealth Network’s patient satisfaction survey was used for the telemedicine questions to evaluate patient perceptions of telehealth compared to in-person visits as well as patient satisfaction with the provider.10 Additionally, questions modified from Edwards et al. addressing attire were used in our questionnaire. Patients had five answer choices for each question: (V) strongly agree, (IV) agree, (III) neutral, (II) disagree, and (I) strongly disagree. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to conduct this study.

Statistics

All statistics were performed on Microsoft Excel Version 16.46 (Microsoft Inc, Redmond, WA). Mean and standard deviation was obtained for each survey item. Mean values between groups were compared with the unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. The median and interquartile ranges for each survey item is provided in Supplement Table 2. Mann-Whitney U-test was utilized to compare the mean ranks and overall distribution between new patients and returning patients (Supplement Table 3).

Results

A total of 100 patient responses were analyzed. Patient demographics and survey responses can be seen in Table 1 . The average age was 54 (range 19-90), the majority were women (80 versus 20 men), and most were returning patients already established in the practice (78 follow-up encounters versus 22 new patient initial encounters). The breakdown of the patient visits by disorder was as follows: 74 for thyroid disorders, 24 patients with parathyroid disease, and 2 were evaluated for adrenal disease.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and survey questions with mean score.

| Combined population (n = 100) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 54 ± 13.7 |

| Gender distribution (M:F) | 20:80 |

| Number of new patients | 22 |

| Number of returning patients |

78 |

| Responses to survey questions |

Mean ± SD |

| Overall experience | |

| I had no difficulty gaining access to the telehealth encounter | 4.71 ± 0.81 |

| I was able to communicate adequately with the provider today | 4.83 ± 0.64 |

| The provider was on time for the appointment | 4.87 ± 0.51 |

| The picture quality was good | 4.71 ± 0.67 |

| The sound quality was good | 4.74 ± 0.71 |

| My privacy and confidentiality were respected and protected during the consultation | 4.89 ± 0.45 |

| I was comfortable with the evaluation that was done | 4.89 ± 0.37 |

| The provider spent an appropriate amount of time with me during this visit | 4.91 ± 0.35 |

| Telehealth made it easier to get healthcare today | 4.70 ± 0.75 |

| The telehealth visit was equivalent to an “in person” provider visit | 4.15 ± 1.25 |

| You would recommend this telehealth experience to others | 4.70 ± 0.72 |

| Provider | |

| The friendliness of my provider was very good | 4.96 ± 0.20 |

| Explanations the care provider gave you about your problem or condition were very good | 4.92 ± 0.31 |

| The provider showed ample concern over your questions or worries | 4.94 ± 0.24 |

| The provider included you in decisions about your treatment | 4.85 ± 0.46 |

| The provider gave ample information about any medications (if any) | 4.78 ± 0.58 |

| The provider gave appropriate follow-up instructions (if any) | 4.88 ± 0.41 |

| The provider used language you could understand | 4.95 ± 0.22 |

| You are very confident in this provider’s course of action | 4.91 ± 0.35 |

| You would recommend this provider to others | 4.93 ± 0.33 |

| Provider’s attire | |

| I felt the provider’s attire was appropriate for this encounter | 4.86 ± 0.45 |

| I felt the provider presented him/herself appropriately during this encounter | 4.93 ± 0.29 |

| I feel as though it is appropriate for providers to wear casual medical attire (surgical scrubs) during the telehealth visit | 4.77 ± 0.68 |

| I feel as though it is appropriate for providers to wear casual attire (t-shirt) during the telehealth visit | 3.63 ± 1.47 |

| I feel as though providers must dress professionally (ex. Shirt/tie and white coat) regardless of the type of encounter | 3.78 ± 1.26 |

| I feel as though providers should wear a white lab coat during the telehealth visit | 3.56 ± 1.19 |

| I have no preference/did not notice the attire the provider wore during the telehealth encounter | 4.18 ± 1.26 |

| What my surgeon was wearing influences my opinion of the care that I receive during the telehealth visit | 3.27 ± 1.50 |

| Video background | |

| I feel as though the background of the video should be an office setting during the telehealth visit | 3.52 ± 1.21 |

| I feel as though the background of the video should be a branded UHealth setting during the telehealth visit | 3.13 ± 1.16 |

| I have no preference/did not notice background of the video during the telehealth encounter | 3.93 ± 1.20 |

| The background of the video during the telehealth visit influences my opinion of the care that I receive during the visit. | 3.00 ± 1.41 |

F = female; M = male; SD = standard deviation.

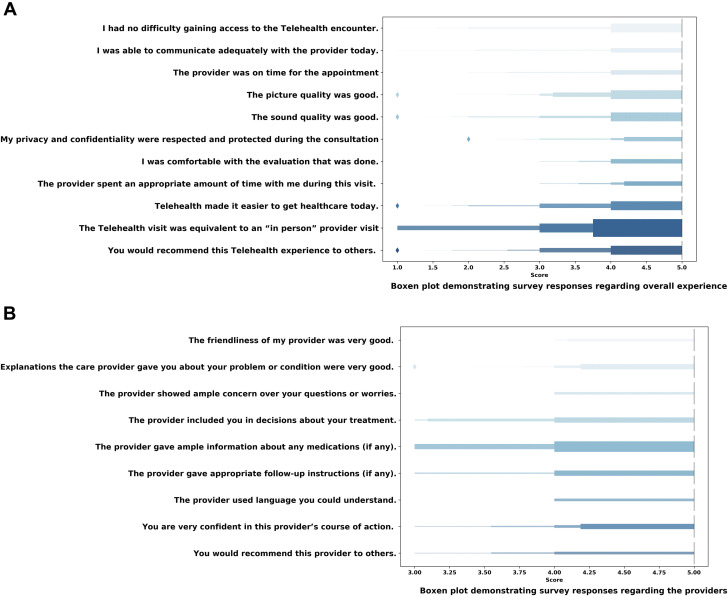

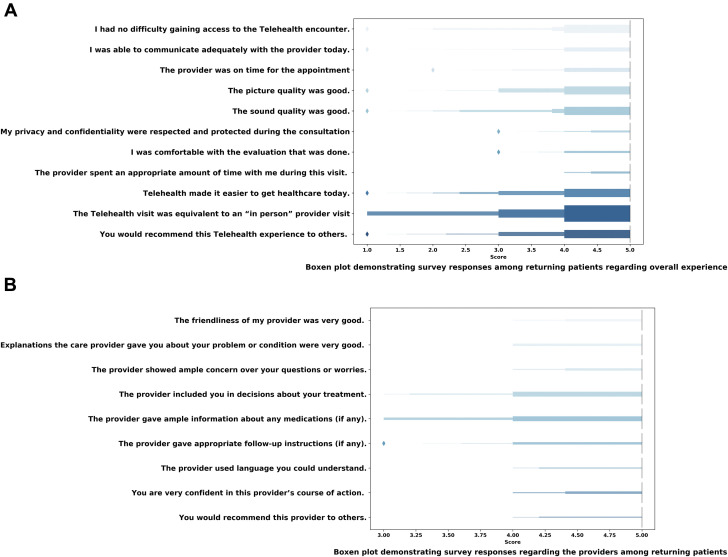

Overall, the general consensus among patients was that they were satisfied with their provider as well as the telehealth modality of healthcare delivery. Patients reported minimal technologic complications obtaining access to the telehealth encounter (4.71 ± 0.81). Additionally, patients reported that the picture and sound quality was appropriate. Patients displayed excellent satisfaction with their provider and comfort utilizing the telehealth modality with a mean Likert score of 4.89 ± 0.37. Patients strongly agreed that telehealth allowed for improved healthcare access (4.7 ± 0.75), often citing elimination of transportation as the valued benefit. The mean Likert score of patients’ perceptions that telemedicine is equivalent to in-person, face-to-face clinic visits was 4.15 ± 1.25 displaying a slightly lower overall consensus. However, the mean Likert score of patients who would still recommend a telemedicine visit to others was still higher (4.70 ± 0.72) and patients generally agreed that this modality facilitated healthcare access (4.70 ± 0.75). With respect to physician attire, patients felt that their providers presented themselves appropriately (4.93 ± 0.29) and felt the attire did not influence their perception of the standard of care received during the telehealth visit (3.27 ± 1.50). Similarly, patients did not have any preference for the video background, and it did not influence their perception of the care received (3.93 ± 1.2). Figure 1 A-D summarizes the distribution of responses of each survey item among the entire cohort.

Fig. 1.

(A) Box plot demonstrating survey responses regarding overall experience. (B) Box plot demonstrating survey responses regarding the providers. (C) Box plot demonstrating survey responses regarding the providers’ attire. (D) Box plot demonstrating survey responses regarding the video background. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Table 2 compares survey responses between new and returning patients, demonstrating an overall positive response independent of the type of patient encounter. Although some survey items showed statistical significance between new and returning patients, the overall perception between these two groups remained clinically equivalent. With regards to the patients’ comfort with their evaluation, returning patients had a higher mean Likert score compared to new patients (4.94 ± 0.29 versus 4.73 ± 0.55, P = 0.02). Additionally, returning patients had a higher mean Liker score with respect to their perception an appropriate amount of time was spent with the provider (4.96 ± 0.19 versus 4.73 ± 0.63, P = 0.01). Both groups equally perceived that a telehealth visit was equivalent to an in-person visit and would recommend this experience to others. Compared to new patients, established patients had a higher mean Likert score with respect to recommending their providers to others (4.97 ± 0.16 versus 4.77 ± 0.61 P < 0.01). New patients had a lower mean Likert score in their opinion of scrubs as appropriate clinic attire (4.50 ± 1.01 versus 4.85 ± 0.54, P = 0.03); nevertheless, they still felt their providers were dressed appropriately with no difference between the groups (4.86 ± 0.35 versus 4.95 ± 0.27, P = 0.23). Responses between patient groups were similar with respect to the video background, with both groups not having a preference.

Table 2.

Survey responses comparing returning patients and new patients.

| Survey question | Returning patients Mean score (±SD) | New patients Mean score (±SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall experience | |||

| I had no difficulty gaining access to the telehealth encounter | 4.69 (0.79) | 4.77 (0.87) | 0.68 |

| I was able to communicate adequately with the provider today | 4.83 (0.57) | 4.82 (0.85) | 0.92 |

| The provider was on time for the appointment | 4.88 (0.46) | 4.82 (0.66) | 0.59 |

| The picture quality was good | 4.72 (0.7) | 4.68 (0.57) | 0.82 |

| The sound quality was good | 4.74 (0.75) | 4.73 (0.55) | 0.92 |

| My privacy and confidentiality were respected and protected during the consultation | 4.95 (0.27) | 4.68 (0.78) | 0.01 |

| I was comfortable with the evaluation that was done | 4.94 (0.29) | 4.73 (0.55) | 0.02 |

| The provider spent an appropriate amount of time with me during this visit | 4.96 (0.19) | 4.73 (0.63) | 0.01 |

| Telehealth made it easier to get healthcare today | 4.65 (0.80) | 4.86 (0.47) | 0.25 |

| The telehealth visit was equivalent to an “in person” provider visit | 4.17 (1.21) | 4.09 (1.41) | 0.80 |

| You would recommend this telehealth experience to others | 4.69 (0.74) | 4.73 (0.63) | 0.84 |

| Provider | |||

| The friendliness of my provider was very good | 4.96 (0.19) | 4.95 (0.21) | 0.88 |

| Explanations the care provider gave you about your problem or condition were very good | 4.95 (0.22) | 4.82 (0.50) | 0.08 |

| The provider showed ample concern over your questions or worries | 4.96 (0.19) | 4.86 (0.35) | 0.09 |

| The provider included you in decisions about your treatment | 4.90 (0.38) | 4.68 (0.65) | 0.05 |

| The provider gave ample information about any medications (if any) | 4.83 (0.49) | 4.59 (0.80) | 0.08 |

| The provider gave appropriate follow-up instructions (if any) | 4.94 (0.29) | 4.68 (0.65) | 0.01 |

| The provider used language you could understand | 4.97 (0.16) | 4.86 (0.35) | 0.04 |

| You are very confident in this provider’s course of action | 4.96 (0.19) | 4.73 (0.63) | 0.01 |

| You would recommend this provider to others | 4.97 (0.16) | 4.77 (0.61) | 0.01 |

| Provider’s attire | |||

| I felt the provider’s attire was appropriate for this encounter | 4.87 (0.44) | 4.82 (0.50) | 0.62 |

| I felt the provider presented him/herself appropriately during this encounter | 4.95 (0.27) | 4.86 (0.35) | 0.23 |

| I feel as though it is appropriate for providers to wear casual medical attire (surgical scrubs) during the telehealth visit | 4.85 (0.54) | 4.50 (1.01) | 0.03 |

| I feel as though it is appropriate for providers to wear casual attire (t-shirt) during the telehealth visit | 3.59 (1.52) | 3.77 (1.31) | 0.61 |

| I feel as though providers must dress professionally (ex. Shirt/tie and white coat) regardless of the type of encounter | 3.82 (1.22) | 3.64 (1.40) | 0.55 |

| I feel as though providers should wear a white lab coat during the telehealth visit | 3.65 (1.16) | 3.23 (1.27) | 0.14 |

| I have no preference/did not notice the attire the provider wore during the telehealth encounter | 4.10 (1.31) | 4.45 (1.06) | 0.25 |

| What my surgeon was wearing influences my opinion of the care that I receive during the telehealth visit | 3.26 (1.52) | 3.32 (1.43) | 0.87 |

| Video background | |||

| I feel as though the background of the video should be an office setting during the telehealth visit | 3.47 (1.21) | 3.68 (1.21) | 0.48 |

| I feel as though the background of the video should be a branded UHealth setting during the telehealth visit | 3.09 (1.13) | 3.27 (1.28) | 0.52 |

| I have no preference/did not notice background of the video during the telehealth encounter | 3.86 (1.20) | 4.18 (1.18) | 0.27 |

| The background of the video during the telehealth visit influences my opinion of the care that I receive during the visit | 2.91 (1.45) | 3.32 (1.25) | 0.23 |

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

SD = standard deviation.

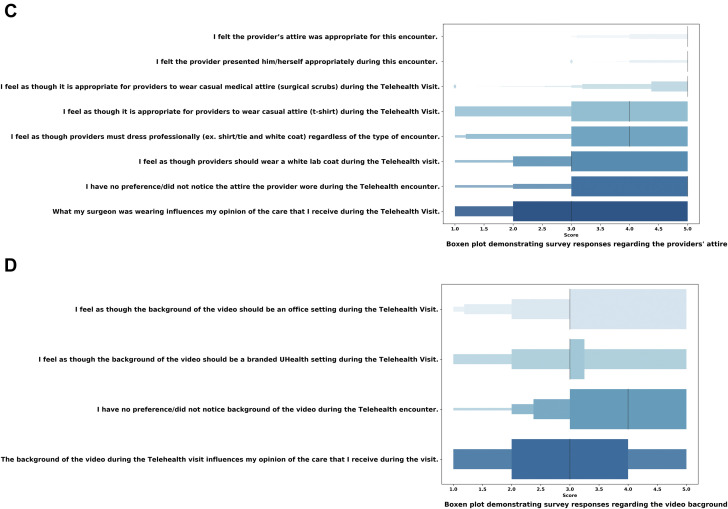

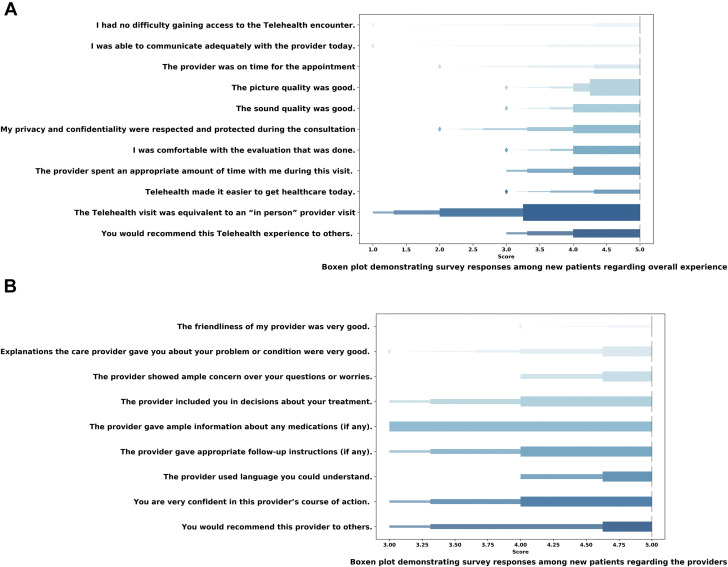

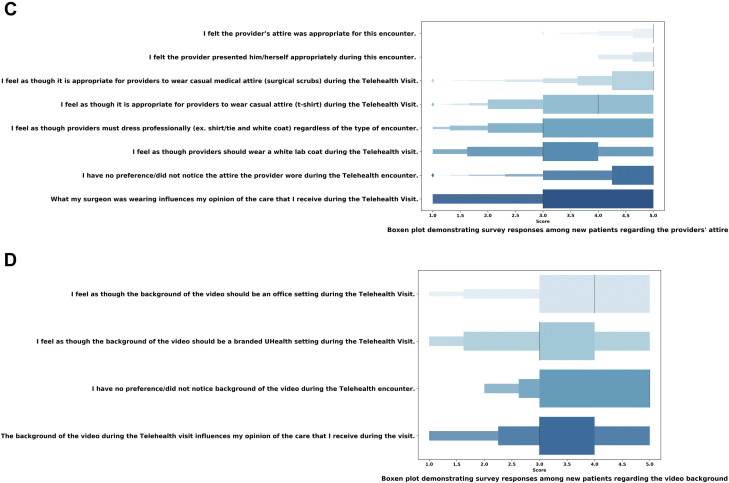

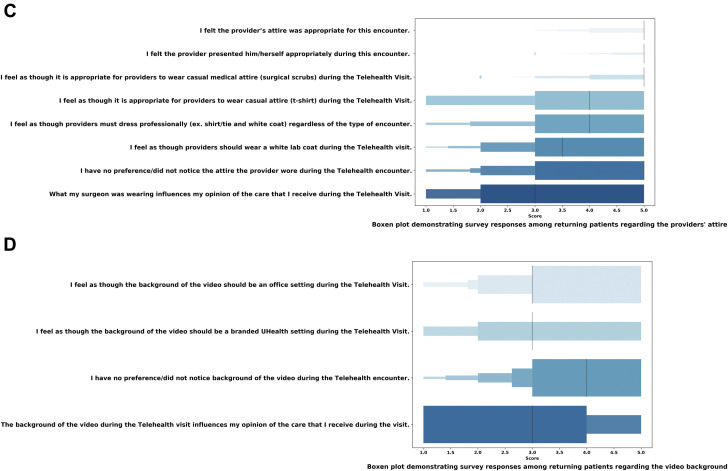

Figure 2A-D visualizes the distribution of responses among new patients, and Figure 3A-D visualizes the distribution of responses among returning patients. Regarding the overall experience, Figures 2A and 3A demonstrate that both groups had a similar distribution of responses and the same median score in that category of the survey. Figures 2B and 3B show that there were more variability in the distribution of responses regarding the provider among new patients compared to returning patients. The responses were also similar in regards to the patients’ perception toward the provider’s attire between both groups, as the distribution of responses in Figures 2C and 3C is similar. However in assessing the responses toward the video background, Figures 2D and 3D show greater variability in the responses between both groups, especially that there were more returning patients who agreed that the video background did not influence their opinion regarding the healthcare they are receiving.

Fig. 2.

(A) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among new patients regarding overall experience. (B) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among new patients regarding the providers. (C) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among new patients regarding the providers’ attire. (D) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among new patients regarding the video background. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Fig. 3.

(A) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among returning patients regarding overall experience. (B) Box plot demonstrating survey responses regarding the providers among returning patients. (C) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among returning patients regarding the providers’ attire. (D) Box plot demonstrating survey responses among returning patients regarding the video background. (Color version of figure is available online.)

A separate analysis was made utilizing median scores, shown in Supplement Tables 2 and 3. Among the entire cohort, the median score to each survey item remained similar to the mean scores described above. Likewise, interquartile ranges demonstrated a similar variability to the calculated standard deviations. When comparing the new patients to the returning patients, Mann-Whitney U-test was used to calculate the P-values in this analysis. The survey items that were found to be statistically significant using the t-test were also found to be statistically significant in the nonparametric analysis.

Discussion

Telehealth has rapidly gained attention as an alternative route to delivering healthcare, especially when patients are unable to attend in-person visits such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the potential economic advantages and patient outreach for telehealth appointments in endocrine surgery has been previously discussed, this study represents the first report that evaluates patient satisfaction and perception after Endocrine Surgery Telehealth visits. The present study demonstrated that the overall patient response to Endocrine Surgery Telehealth was predominately positive. Patients were very satisfied with the outcomes of their visits, would strongly recommend this modality to others, and the perception of their providers was overwhelmingly positive. Additionally, returning and new endocrine surgery patients equally perceived that telehealth was similar to in-person visits.

Returning and new patients alike responded generally in a positive fashion; however, there was a slight discrepancy between these groups. Returning patients predominantly were more satisfied across the survey questions when compared to new patients. This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that returning patients are more comfortable with the providers given that they had an existing prior relationship. Greif et al. 10 demonstrated similar findings among orthopedic patients. The implications of these findings therefore suggest that new patients may require additional time during their telemedicine visit to establish a strong rapport with the provider, or that new patients might be better served with an initial in-person visit with future follow-ups to be conducted by telemedicine. Therefore, perhaps telehealth should be limited to only established patient encounters such as postoperative or follow-up appointments with the index visit being an in-patient visit.6 New patients typically require a full physical examination and preoperative adjuncts often requiring in-person appointments. However, even in this population subset there remains a role for telemedicine as it may provide an introduction and opportunity to establish rapport with the patient thus fostering the patient-doctor relationship, which could later be followed up in person if necessary. Furthermore, telemedicine visits as the initial encounter could also identify lapses in patient workup or clearance required prior to their in-person visit, thus optimizing both provider and patient time. Moreover, the type of disease being evaluated might also play a role in choosing which patients could be better served with a telemedicine visit or in-person visit. New patients with thyroid or parathyroid issues who may need additional imaging in the office for assessment are likely not suitable for a telemedicine visit. Conversely, postoperative and follow-up patients with thyroid and parathyroid disorders may have a telemedicine visit without compromising their healthcare delivery or requiring a subsequent in-person visit, especially if the purpose of the visit is to discuss results. On the other hand, adrenal patients might be better served with a telemedicine visit initially to ensure all the workups have been performed, which would determine if they would need further treatment and a subsequent in person evaluation. Provider review of records in advance of the patient’s visit is an important part of identifying appropriate telemedicine candidates.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was gaining popularity across many medical specialties. Economically speaking, telemedicine decreases operational costs as less infrastructure, ancillary staff, and supplies are required.1 , 2 , 11 , 12 Productivity and efficiency are further optimized with telehealth as physicians can readily conduct these visits anytime and anywhere. The inevitable operative emergencies, transportation delays, or traditional distractions that historically would have caused significant delays or cancellations disrupting the in-person clinic schedule are not an issue when using telemedicine. Both patients and providers are more apt to still complete a clinic visit no matter the obstacles; they can even be accessed using a smart phone. Although a single missed clinic visit is seemingly benign, some estimate the cumulative annual effect of missed healthcare appointments to account for nearly $150 billion healthcare dollars.13 The widespread implementation of telemedicine has the potential of not only decreasing healthcare costs overall, but also decreasing costs associated with missed healthcare appointments.

Additionally, telemedicine removes traditional geographic constraints affording patient access to any provider no matter the physical location, dually benefitting the patient and provider. Through the use of telemedicine, providers can project healthcare services beyond the traditional means and likewise increase access to care for patients. Via telemedicine, patients with rare diseases can seek out national or international experts, and patients in rural settings can receive the same care as their metropolitan counterparts. Additionally, telehealth may retain patients who previously would have been lost to follow-up, exacerbating lapses in clinical care, and potentially resulting in avoidable progression of disease.

From an epidemiology standpoint, telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic has translated into significant infection control benefits. Namely, patients and providers can reduce their risk of disease transmission by decreasing the number of in-person visits and amount of time spent in these visits appropriately. Vilendrer et al. 14 demonstrated such benefits across three hospital systems significantly reducing expended personal protective equipment and reducing infection rates following implementation of telehealth modalities. Similar findings have been replicated in multiple studies, particularly with respect to observed decreases in the rates of disease transmission following employment of telemedicine capabilities.15 , 16 In fact, the centre for disease control themselves advocated for the utilization of telemedicine when possible to reduce transmission.17 Thus, with the support from governmental bodies and reported benefits of decreased disease transmission using telemedicine, our findings of favorable patient perception of telehealth during the current COVID pandemic are not entirely surprising.

The present study also looked at the role of the provider’s attire and video background on the patient’s perception of the quality of care they are receiving. Both returning and new patients did not have a preference with respect to the provider’s attire or video background. Patients did not perceive that it was necessary for the provider to be in formal attire, and that casual wear and scrubs were equally appropriate. This directly contradicts multiple studies that previously reported patient preference for formal attire.9 , 18 , 19 In fact, Jennings et al. 18 in an image-based survey found the images with physicians in white coats to elicit the highest and strongest ratings in patient confidence, intelligence, surgical skill, trust, safety, and comfort. Interestingly, the same perceptions were not exactly observed in the present study. This discrepancy in part could be explained by the virtual format of telehealth where the formalities of inpatient appointments are no longer applicable. Similarly, secondary to quarantines and city-wide curfews much of our patient population was confined to their personal homes at the time of their telehealth appointment. Therefore, while our provider setting was standardized, the informality on the patient’s side may have lessened patient expectations for traditional formal attire thus further explaining the discrepancy of our results with previous reports. Finally, as previously noted our study population consisted of more returning patients, therefore these patients likely had previously seen their provider in formal attire with white coats on multiple previous occasions; thus, scrub attire in the virtual format did not influence their established perception of the provider. In terms of the provider’s virtual background during the telehealth visit, a relative indifference of preference was noted. A surprising finding given the plethora of reports emphasizing specific designs and patient preference for everything from room color to wattage of the light bulbs.20, 21, 22 Our findings contradicting these previous studies however are encouraging particularly for telehealth-naïve providers who may have been intimidated or overwhelmed by these previous reports precluding initiation of telehealth services.

This study is not without limitations. The survey used for this study has not been validated before in this specific patient population. Additionally, this survey was not used for the study population prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Surveys given to patients prior to the pandemic for in-person visits showed similar results in regard to patient satisfaction of their provider. However, since the two surveys are different, we cannot make accurate comparisons. The survey is also subject to response bias, as it is a qualitative assessment of the patient’s experience and subjective in nature, therefore responses may not be reproducible on subsequent evaluations even in the same subject. Additionally, the reported results stem from a single practice in a single state, therefore the results may not be generalizable to all healthcare systems and practices. The distribution of patients between new patients and established patients was also uneven. This could be explained due to the fact that we surveyed the first 100 patients consecutively at the start of the COVID pandemic, therefore there was a greater proportion of follow-up patients compared to our usual prepandemic visit breakdown.

Moreover, this study is prone to a type 2 error given the limited number of participants in this study. Additionally, the study included more returning patients than new patients, which could skew the results thus underpowering the analysis between the two cohorts. An additional limitation relates to the COVID-19 pandemic which could bias patient’s view of telemedicine in a more favorable light. Without the ongoing pandemic, patients might have a less favorable view of telemedicine overall. Another limitation perhaps introducing bias to our results is that only patients with access to telehealth compatible technology could participate in virtual appointments, thus underrepresenting the perceptions of patients of low socioeconomic classes without access to such devices. Finally, as patients were scheduled by office staff, we did not have data regarding the number of patients who refused telemedicine. This could have resulted in a selection bias, as only patients who are enthusiastic about telemedicine may have agreed for this type of encounter and thereby had favorable opinions regarding this modality. Nevertheless, our reported findings remain significant, expanding our understanding of endocrine surgery patient’s opinions of telehealth.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that telemedicine does not compromise patient satisfaction or healthcare delivery for patients and therefore is a viable clinic option for an endocrine surgery practice. Patients who have seen providers in-person previously are more likely to be satisfied with their provider than new patients. However, the majority of patients were satisfied with their experience and this modality. Moreover, surgeon attire and video background did not influence patients’ opinion regarding the care they received. Further studies are needed to validate these findings and identify patients best suited for this modality, but preliminary analysis demonstrated overwhelmingly positive results and supports the implementation of telemedicine in the endocrine surgery practice.

Author Contributions

DK and JF contributed to the study conception and design. MJ and DK conducted the survey. MJ analyzed the data. MJ, MM, DK and JF prepared the manuscript. MJ, MM, DK, JIL and JF reviewed the manuscript.

Meeting Presentation

Presented at the Virtual 16th Annual Academic Surgical Congress, February 2nd to 4th, 2021.

Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.12.014.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Zheng F., Park K.W., Thi W.J., et al. Financial implications of telemedicine visits in an academic endocrine surgery program. Surgery. 2019;165:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennett P.A., Affleck Hall L., Hailey D., et al. The socio-economic impact of telehealth: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9:311–320. doi: 10.1258/135763303771005207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khairat S., Meng C., Xu Y., Edson B., Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and virtual care trends: cohort study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e18811. doi: 10.2196/18811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asiri A., AlBishi S., AlMadani W., ElMetwally A., Househ M. The use of telemedicine in surgical care: a systematic review. Acta Inform Med. 2018;26:201–206. doi: 10.5455/aim.2018.26.201-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urquhart A.C., Antoniotti N.M., Berg R.L. Telemedicine–an efficient and cost-effective approach in parathyroid surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1422–1425. doi: 10.1002/lary.21812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha Z., Schapira R.M., Laud P.W., McNutt G., Roter D.L. Patient satisfaction with physician-patient communication during telemedicine. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15:830–839. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards R.D., Saladyga A.T., Schriver J.P., Davis K.G. Patient attitudes to surgeons' attire in an outpatient clinic setting: substance over style. Am J Surg. 2012;204:663–665. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrilli C.M., Mack M., Petrilli J.J., et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature–targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006578. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greif D.N., Shallop B.J., Rizzo M.G., et al. Telehealth in an orthopedic sports medicine clinic: the first 100 patients. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:1275–1281. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha N., Cornell M., Wheatley B., Munley N., Seeley M. Looking through a different lens: patient satisfaction with telemedicine in delivering pediatric fracture care. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2019;3:e100. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koutras C., Bitsaki M., Koutras G., Nikolaou C., Heep H. Socioeconomic impact of e-Health services in major joint replacement: a scoping review. Technol Health Care. 2015;23:809–817. doi: 10.3233/THC-151036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Missed appointments cost the U.S. healthcare system $150B each year. Healthcare Innovation Group. 2021. https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/clinical-it/article/13008175/missed-appointments-cost-the-us-healthcare-system-150b-each-year Available at: Accessed October 02, 2021.

- 14.Vilendrer S., Patel B., Chadwick W., et al. Rapid deployment of inpatient telemedicine in response to COVID-19 across three health systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves J.J., Hollandsworth H.M., Torriani F.J., et al. Rapid response to COVID-19: health informatics support for outbreak management in an academic health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:853–859. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhai Y., Wang Y., Zhang M., et al. From isolation to coordination: how can telemedicine help combat the COVID-19 outbreak? medRxiv. 2021. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.20.20025957v1 Available at: Accessed October 02, 2021.

- 17.Interim guidance for healthcare facilities: preparing for community transmission of COVID-19 in the United States. CDC. 2021. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/85502 Available at: Accessed October 02, 2021.

- 18.Jennings J.D., Ciaravino S.G., Ramsey F.V., Haydel C. Physicians' attire influences patients' perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908–1918. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4855-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamata K., Kuriyama A., Chopra V., et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204–210. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krupinski E.A. Telemedicine workplace environments: designing for success. Healthcare (Basel) 2014;2:115–122. doi: 10.3390/healthcare2010115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Major J. Telemedicine room design. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11:10–14. doi: 10.1177/1357633X0501100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krupinski E.A. Medical grade vs off-the-shelf color displays: influence on observer performance and visual search. J Digit Imaging. 2009;22:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s10278-008-9156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.