Abstract

Objective:

Genetic variants spanning the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L3 (UBE2L3) gene are associated with increased expression of the UBE2L3-encoded E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, UbcH7, that facilitates activation of proinflammatory NF-κB signaling, and susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. This study aims to delineate how genetic variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype function to drive hypermorphic UBE2L3 expression.

Methods:

We used bioinformatic analyses, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and luciferase reporter assays to identify and functionally characterize allele-specific effects of risk variants positioned in chromatin accessible regions of immune cells. Chromatin conformation capture (3C)-qPCR, ChIP-qPCR, and siRNA knockdown assays were performed on patient-derived EBV-transformed B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype to determine if the risk haplotype increases UBE2L3 expression by altering the regulatory chromatin architecture in the region.

Results:

Five of the seven prioritized variants demonstrated allele-specific increases in nuclear protein binding affinity and regulatory activity. HiChIP and 3C-qPCR uncovered a long-range interaction between the UBE2L3 promoter (rs140490, rs140491, rs11089620) and downstream YDJC promoter (rs3747093) that was strengthened in the presence of the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype, and correlated with the loss of CTCF binding and gain of YY1 binding at the risk alleles. Depleting YY1 by siRNA disrupted the long-range interaction between the two promoters and reduced UBE2L3 expression.

Conclusion:

The UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype increases UBE2L3 expression through strengthening a YY1-mediated interaction between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters.

Introduction

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L3 (UBE2L3), located on 22q11.21, encodes an E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UbcH7. UbcH7 is a functional subunit of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), a crucial regulator of the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway (1-4). In the LUBAC, UbcH7 facilitates formation of linear polyubiquitin chains that are conjugated to the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO). Ubiquitinated NEMO dissociates from the Inhibitor of NF-κB kinase complex (IKK), allowing activated IKK to degrade the inhibitory subunit, IκB. Activated NF-κB then translocates to the nucleus to initiate transcription of proinflammatory mediators (2-4). In human primary B cells and monocytes, increased UbcH7 expression enhanced LUBAC-mediated NF-κB activation, as well as the proliferation of plasmablasts and plasma cells (5,6), thus implicating UBE2L3/UbcH7 as a critical regulator of pro-inflammatory responses in immune cells.

UBE2L3 is a prominent genetic susceptibility locus for several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (5-13), rheumatoid arthritis (5,13-15), celiac disease (5,16), Crohn’s disease (5,17,18), inflammatory bowel disease (5,19), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (5,20), and psoriasis (5,21). Transracial mapping of European, Asian, and African American SLE populations identified a single 67 kb autoimmune disease-associated risk haplotype that spans the UBE2L3 gene body and extends to the nearby YdjC Chitooligosaccharide Deacetylase homology (YDJC) gene (10). Although it has been established that this risk haplotype is correlated with increased UBE2L3 mRNA and UbcH7 protein expression (5,6,10), the genetic regulatory mechanisms driving increased expression in the context of the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype remain poorly understood.

In this study, we prioritized seven risk variants spanning the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype positioned in regions of high chromatin accessibility. We discovered that four of the seven risk variants co-bound the transcription factors, Yin Yang 1 (YY1) and CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF). The risk alleles at each variant demonstrated increased binding affinity for YY1 at the expense of CTCF, and strengthened the long-range interactions between the promoters of UBE2L3 and YDJC. Our findings delineate a novel mechanism that explains how the risk haplotype likely drives elevated UBE2L3 expression in autoimmune disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and Reagents

Jurkat and THP-1 cells were procured from ATCC. Epstein Barr Virus (EBV)-transformed B cell lines were obtained from the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR) housed by the Oklahoma Rheumatic Disease Research Cores Center (ORDRCC) at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) with IRB approval (22). Sanger sequencing was used to verify the genotype of EBV B cell lines carrying the risk (A) or non-risk (C) allele of the index SNP, rs140490. Jurkat, THP-1, and EBV B cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1X penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture (Atlanta Biologicals, Inc.), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza). THP-1 cell medium was also supplemented with 50 μM ß-mercaptoethanol. Where indicated, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin (P/I; 50 ng/mL, 500 ng/mL) for 2 h prior to harvest. For the siRNA knockdown of CTCF or YY1, EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype were transiently transfected with 10 nM siRNA using 4D Amaxa Nucleofector Unit for EBV B cells (Lonza; Nucleofector SF kit, #V4XC-2032). The ON-TARGETplus human CTCF siRNA SMARTPool (#L-020165-00-0005), human YY1 siRNA SMARTPool (#L-011796-00-0005), and non-targeting scramble siRNA pool (#D-001810-10-05) were purchased from Dharmacon. All stock laboratory chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich or ThermoFischer.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

Complementary pairs of 41 bp non-risk and risk probes of individual variants were chemically synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Supplemental Table 1), annealed and end-labeled with (γ-32P) adenosine triphosphate (Perkin Elmer) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs (NEB); #M0201S). Nuclear proteins were extracted from Jurkat, EBV B, and THP1 cells with or without P/I stimulation for 2 h. Ten micrograms of nuclear protein were incubated with labelled 50,000 cpm non-risk or risk probes in binding buffer (1 μg poly dI-dC, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 0.5 mM EDTA) for 30 min at room temperature. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a non-denaturing 5% acrylamide gel in 0.5X Tris borate/EDTA. Gels were dried and exposed overnight on a phosphor screen. DNA-protein complexes were visualized on a phosphor-imager (Bio-Rad; GS-360) and quantified using Bio-Rad Quantity 1D Analysis software. For competition assays, 10, 50, and 100-fold excess of unlabeled non-risk or risk probes were added to the EMSA binding reactions.

Dual Luciferase Reporter assay

We cloned approximately 350 bp of the DNA sequences surrounding the non-risk or risk alleles of selected UBE2L3 or YDJC variants (Supplemental Table 2) into the promoter-less firefly luciferase plasmid, pGL4.14, or the minimal promoter firefly luciferase plasmid, pGL4.23 (Promega). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to separate the physically close risk variants, rs140491 and rs11089620 or rs12484550, rs5998599 and rs9621715 (Supplemental Table 2). The empty vector, non-risk clone, or risk clone was transiently co-transfected with the transfection control renilla luciferase plasmid, pRL-TK, into homozygous non-risk EBV B cells using 4D Amaxa Nucleofector Unit for EBV B cells (Lonza; Nucleofector SF kit, #V4XC-2032). Twenty-four hours post transfection, cells were treated with or without P/I for 2 h. Promoter or enhancer activity was determined according to the Promega Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay manufacturer instructions (Promega). Relative luciferase units (RLU) for each sample were determined by normalizing the firefly luciferase activity to the renilla luciferase activity. RLU was further normalized to the vector only control and reported as normalized RLU.

HiChIP

H3K27ac- and CTCF-mediated chromatin interactions were measured for the whole genome of EBV B cells as part of a previously published study [NCBI GEO: GSE116193](23). HiChIP raw reads (fastq files) were aligned to the hg19 human reference genome using HiC-Pro (24). Aligned data were processed and analyzed through the hichipper pipeline (25). MACS2 was used for anchor calling based on ChIP-enriched regions (26). Loops were derived from the linked paired-end reads that overlapped with anchors. DNAlandscapeR was used to visualize the long-range interactions in two dimensions.

Chromatin Conformation Capture with Quantitative PCR (3C-qPCR)

3C-qPCR was performed as previously described with minor modifications (27). Ten million cells from EBV B cell lines homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype were used per 3C library preparation. For 3C analysis of YY1 knockdown, EBV B cells transfected with YY1-targeted or scramble siRNA were harvested after 24h and 3 million cells were used per 3C library preparation. Cells were crosslinked with 2% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, then quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were lysed, then the nuclei were pelleted and resuspended in 1.25X CutSmart Buffer (NEB, #B7204S). Nuclei were treated with 0.3% SDS at 37 °C for 1 h, then 2% Triton X-100 for 1 h. Chromatin was digested overnight at 37 °C using 200U BssSI-v2 (NEB, #R0680L). Ligation was performed overnight at 16°C or on ice using T4 DNA ligase (NEB, #M0202M), with similar results. Chromatin was then de-crosslinked by adding Proteinase K and incubating overnight at 65°C. RNase A treatment was used to remove RNA contamination from the chromatin. 3C DNA template was then purified by phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extractions; repeated twice. 3C-qPCR primers were designed to anneal in close proximity to BssSI-v2 cutting sites and amplify 9 fragments spanning the UBE2L3-YDJC 3C locus (Figure 3A; Supplemental Table 3). Primer efficiency was validated and normalized using template DNA from BAC clone, CTD3095B9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #96012), digested with BssSI-v2. All qPCR assays were performed using LightCycler480 SYBR Green probe according to manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics). The relative interaction frequency (RIF) was calculated by normalizing the interaction frequencies to the interaction frequency of the random ligation control (Fragment 2). Interactions were considered positive if the RIF was greater than the interactions between the anchor and random ligation control (Fragment 2) (28,29).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and Quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR)

ChIP assays were performed using the TruChIP chromatin shearing reagent kit (Covaris; #520154) to test CTCF and YY1 binding at the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter regions. In brief, 1.5x107 EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. Nuclei were isolated and sonicated in 1 mL of shearing buffer with a Covaris S1 sonicator (#E220). Sheared chromatin was precleared using Magna ChIP Protein A+G magnetic beads (Millipore; #16-663) blocked in PBS with bovine serum albumin (BSA), protease inhibitor cocktail (EMD Millipore; #539132), and Halt phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #1862495). Chromatin-protein complexes were then immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C by mild agitation with blocked and pre-cleared Magna Protein A+G magnetic beads and antibodies specific for CTCF (anti-CTCF; #D31H2; Cell Signaling Technology), YY1 (anti-YY1; #sc-7341X; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or respective normal IgG isotype controls (normal rabbit IgG (#2729S) or normal mouse IgG (#5415S); Cell Signaling Technology). DNA was eluted from the immunoprecipitated chromatin complexes, reverse-crosslinked, purified by Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), and subjected to real-time qPCR analysis using LightCycler480 SYBR Green (Roche Diagnostics) and primers flanking the UBE2L3 or YDJC risk variants (Supplemental Table 4). All primer pairs were validated using input DNA prior to performing ChIP-qPCR.

Western blotting

EBV B cells were harvested 24h, 48h, or 72h post-transfection with target or scramble siRNA, pelleted, washed in cold PBS and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology; #9806S) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (EMD Millipore; #539132). Cell lysates were collected and protein concentrations were determined by Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #Q33212). Proteins were denatured in 4X SDS loading buffer at 95°C for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad; #1620177), blocked with 5% non-fat dairy milk, and analyzed by western blotting as indicated using antibodies against UBE2L3/UbcH7 (anti-UBE2L3/UbcH7; #3848S; Cell Signaling Technology), YY1 (anti-YY1; #sc-7341; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); CTCF (anti-CTCF; #D31H2; Cell Signaling Technology), and Beta Actin (anti-Beta Actin; #4967S; loading control; Cell Signaling Technology). Blots were developed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad; #1705060) and visualized using a ChemiDocMP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

RNA extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from EBV B cells carrying the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed using QuantiTect reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Gene expression was measured by real-time PCR analysis using Light Cycler480 SYBR Green (Roche Diagnostics). Gene expression primers for human UBE2L3, human YDJC, human SDF2L1, and human PPIL2 were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Supplemental Table 5); human GAPDH (#PPH00150F) was from Qiagen.

Results

Prioritization of candidate variants spanning the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype.

We hypothesized that candidate variants positioned in regions of open chromatin would have an increased potential to modulate transcription factor binding and UBE2L3 expression (30,31). We identified seven variants that co-localized with ATAC-seq peaks from publicly available Assay for Transposase Accessible Chromatin Sequencing (ATAC-seq) data from primary B cells, T cells, and monocytes using the UCSC Genome Browser [NCBI GEO: GSE74912, GSE74310] (32) (Supplemental Figures 1, 2A-C). One variant, rs140490, located in the UBE2L3 promoter, has been the most frequently reported index SNP marking the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype (Supplemental Figure 1) (5,10). Of the remaining six variants, two are located in the UBE2L3 promoter region (rs140491, rs11089620), three in the UBE2L3 first intron (rs12484550, rs5998599, rs9621715), and one in the YDJC promoter region (rs3747093). These variants also co-localized with areas enriched for Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE)-reported chromatin marks of functional regulatory elements, including: 1) the epigenetic marker of active enhancers, acetylation at lysine 27 of Histone H3 (H3K27ac; Supplemental Figure 2D); 2) the epigenetic marker of promoters, tri-methylation at lysine 4 of Histone H3 (H3K4Me3; Supplemental Figure 2E); 3) genomic regions enriched with cytosine-guanine dinucleotide repeats (CpG islands) that are DNA methylation regions in promoters (Supplemental Figure 2F); and 4) ChIP-seq clusters of transcription factor binding sites (Supplemental Figure 2G).

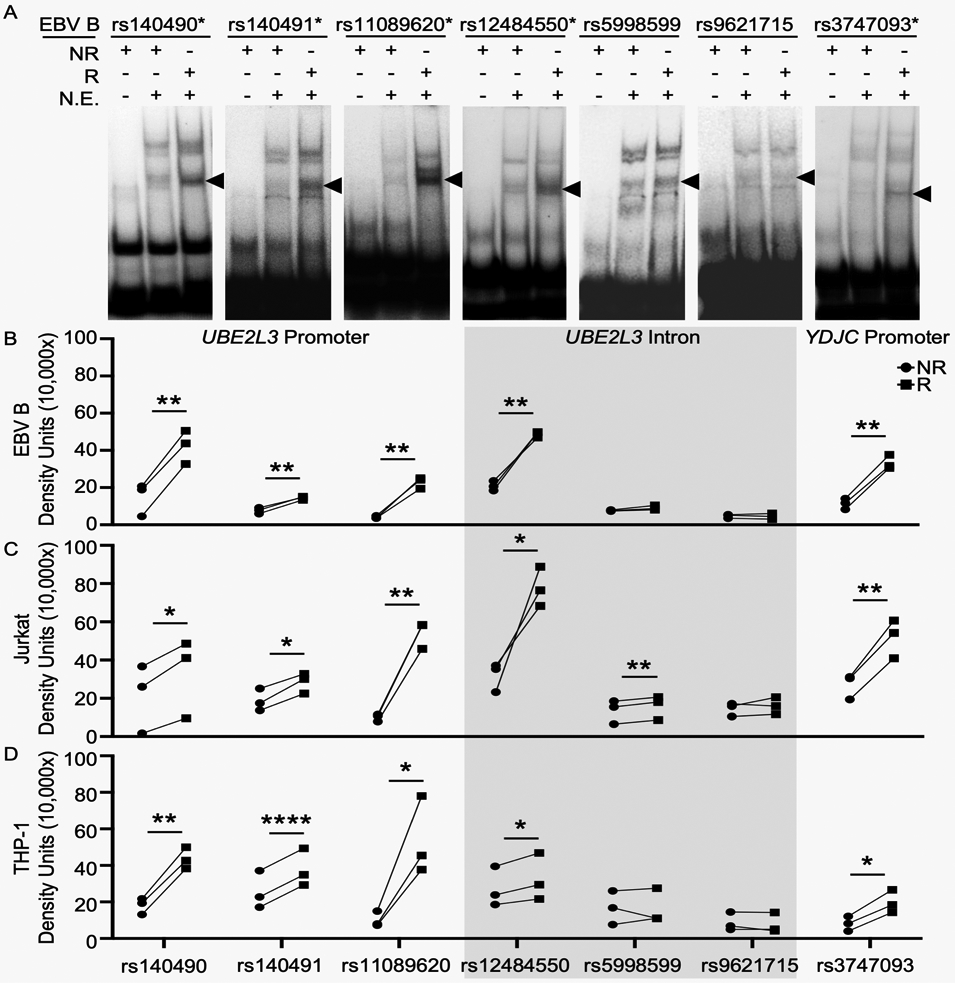

Risk alleles on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype increase nuclear protein complex binding.

To assess the functional potential of the prioritized variants, we performed EMSAs using radiolabeled oligonucleotides carrying the risk or non-risk alleles of each variant, and nuclear proteins extracted from three immune-relevant human immortalized cell lines stimulated with or without P/I for 2 h: EBV B, Jurkat, and THP-1 cell lines representing B cell, T cell, and monocytoid lineages, respectively. For the three UBE2L3 promoter variants (rs140490, rs140491, rs11089620), one UBE2L3 intronic variant (rs12484550), and the YJDC promoter variant (rs3747093), we observed significant increases in the nuclear protein binding to the risk alleles compared to the non-risk alleles, in all three cell lines at rest and after P/I stimulation (Figure 1; Supplemental Figures 3, 4). In unstimulated Jurkat cells only, the UBE2L3 intronic variant, rs5998599, showed a modest increase in binding to the risk allele, compared to non-risk allele (Figure 1C; Supplemental Figure 3B), that was lost after P/I stimulation (Supplemental Figure 3B, 4B). The UBE2L3 intronic variant, rs9621715, was the only tested variant that did not exhibit allele-specific binding in any of the three cell lines (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 3, 4). The specificity of our EMSA probes were confirmed by competition binding with unlabeled probes using EBV B cell nuclear extracts (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 1. Risk alleles on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype increase the binding affinities of nuclear protein complexes.

EMSAs were performed using radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing the non-risk (NR) or risk (R) alleles of the indicated risk variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune haplotype. Nuclear extracts (N.E.) were isolated from EBV B (A,B, Supplemental Figure 3A), Jurkat (C, Supplemental Figure 3B), or THP-1 cells (D, Supplemental Figure 3C) at rest. (A) Images are representative of n=3. *indicates variants that exhibit allele-specific mobility shift. Black arrow indicates the allele-specific mobility shift that was quantified in (B-D) for each indicated nuclear protein-bound probe. (B-D) Quantitative densitometry of the nuclear protein-bound oligonucleotides shown in (A) and Supplemental Figures 3B-C. Statistical significance was determined using a paired t-test, n=3; * indicates p<0.05; ** indicates p<0.01; ****indicates p<0.0001.

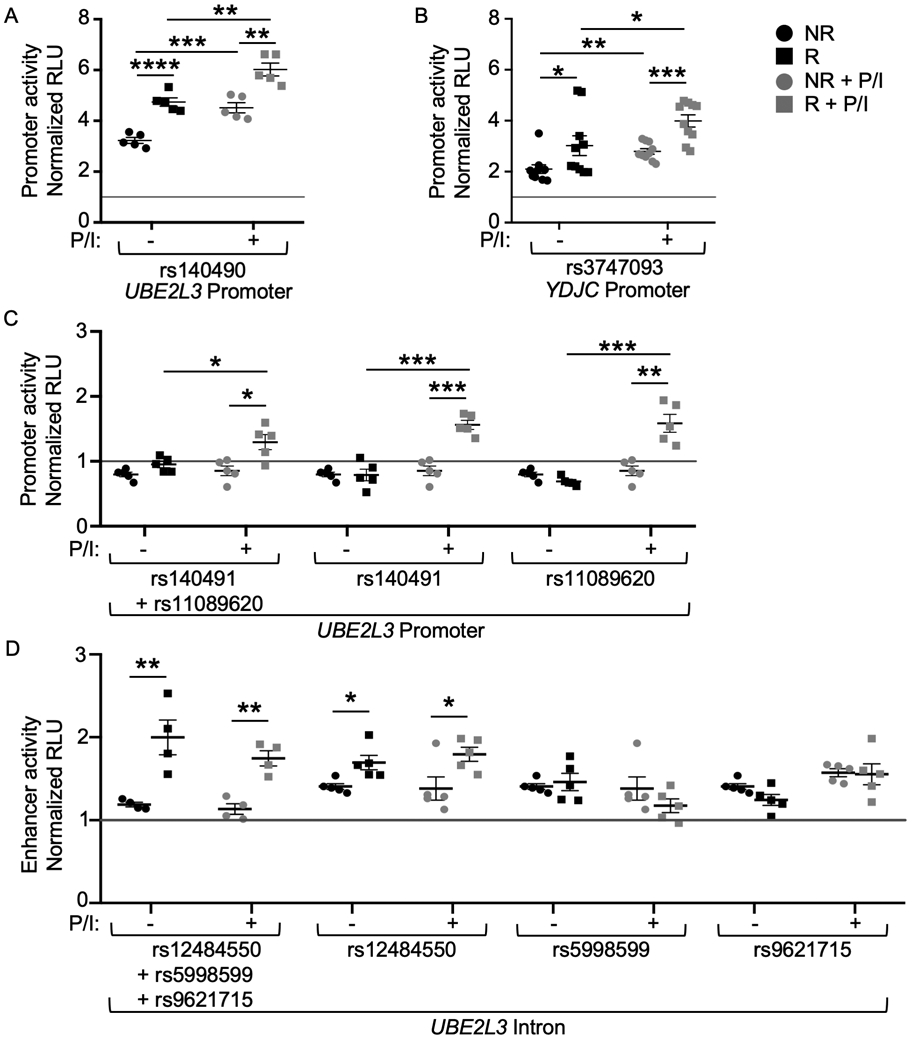

Risk variants on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype exhibit allele-specific increases in reporter gene expression.

Using a promoter-less luciferase reporter construct, we observed that the risk alleles of the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter region variants, rs140490 and rs3747093, exhibited significant increases in reporter gene expression, which was further increased following P/I stimulation (Figure 2A, 2B). In contrast, the risk alleles of the UBE2L3 promoter region variants, rs140491 and rs11089620, cloned in combination (due to close positional proximity) or separately, demonstrated significant allele-specific promoter activity only after P/I stimulation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Risk variants on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype exhibit allele-specific increases in reporter gene expression.

(A-D) Sequences carrying the non-risk (NR) or risk (R) alleles of the indicated variants were cloned into a promoter-less vector (pGL4.14; A-C) or minimal promoter vector (pGL4.23; D). See Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 for NR and R sequences. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to dissect physically close variants that were originally cloned together (C, D). Luciferase activity was measured after transient transfection of EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk haplotype at rest (black shapes) or after 2h stimulation with P/I (gray shapes). Luciferase activity was normalized to renilla transfection control, then the vector-only control (gray line), and reported as the mean ± SEM of normalized relative fluorescence units (RLU). Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, n ≥ 4; * indicates p<0.05; ** indicates p<0.01; ***indicates p<0.001; ****indicates p<0.0001; NS indicates not significant.

We then tested the UBE2L3 intronic region variants, rs12484550, rs5998599, and rs9621715, using a minimal-promoter luciferase construct that measures enhancer-like function. We found that the risk alleles of these variants demonstrated enhancer activity when tested in combination (due to positional proximity) independent of stimulation (Figure 2D). When tested individually, each variant demonstrated enhancer-like function, however the allele-specific effect was only observed for the rs12484550 risk allele (Figure 2D). Together, the increases in nuclear protein binding in the EMSA and increased expression of the luciferase reporter gene in the context of the risk alleles, is concordant with the elevated expression of UBE2L3 observed in previously published studies (5,6,10).

The UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype strengthens long-range looping between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter regions.

Since changes in transcription activity are often accompanied by changes in chromatin conformation, we leveraged a H3K27ac and CTCF HiChIP dataset from EBV B cell lines [NCBI GEO: GSE116193] to assess chromatin organization in the region of UBE2L3-YDJC (23). A robust H3K27ac loop was observed between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter elements, while a weaker interaction was seen with both promoters and the UBE2L3 intronic enhancer (Supplemental Figure 6). In addition, the YDJC promoter element was positioned in a CTCF loop anchor that interacts with the 3’UTR of UBE2L3. Thus, the UBE2L3-YDJC haplotype risk alleles may alter the regulatory function of the UBE2L3 and YDJC promotors, as well as the UBE2L3 intronic enhancer, by modulating long-distance DNA interactions.

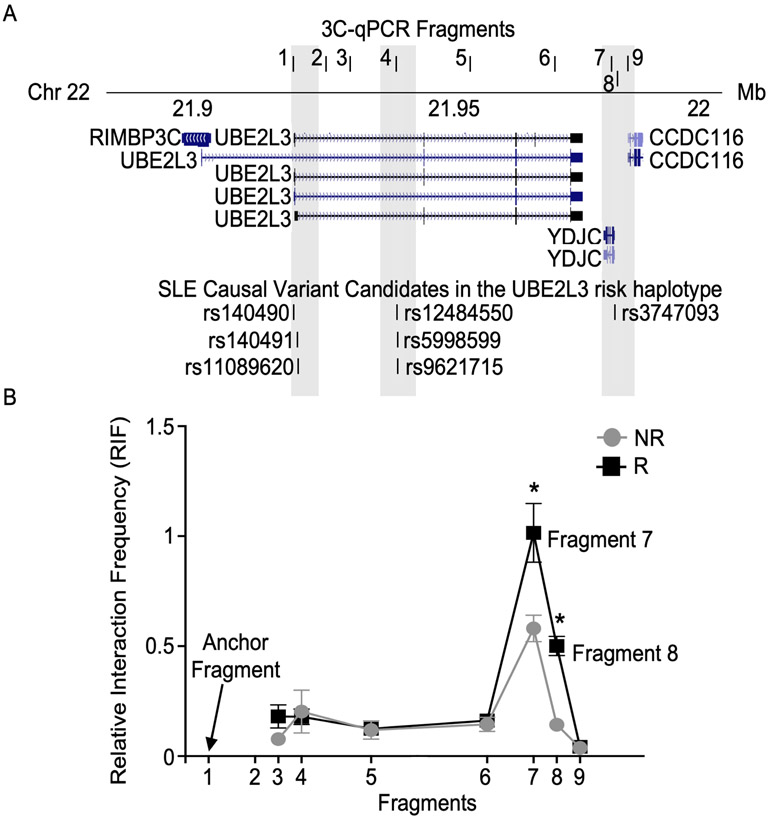

To confirm the HiChIP results and determine the effect of the risk haplotype on chromatin organization, we performed 3C-qPCR in EBV B cell lines homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype. Long-range interactions between the UBE2L3 promoter region (anchor fragment 1, upstream of rs140490), and other potential contact points across the UBE2L3-YDJC locus (Fragments 2 to 9) (Figure 3A) were measured. Consistent with the HiChIP data, we observed a long-range interaction between the UBE2L3 promoter (anchor fragment 1) and the YDJC promoter (fragments 7 and 8) in EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk haplotype (Figure 3B). Moreover, we observed evidence of significantly increased long-range interactions between the same fragments in EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype. In contrast to the HiChIP data, we did not detect an interaction between either promoter element and the UBE2L3 intronic enhancer (Fragment 4) using 3C-qPCR (Figure 3B). Overall, these results suggest that the risk alleles of the selected variants in the promoter regions of UBE2L3 and YDJC strengthen long-range physical interactions between the two promoters.

Figure 3. Risk variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype strengthen long-range interactions between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters.

(A) Schematic depiction of the 3C-qPCR primers relative to the UBE2L3-YDJC locus and indicated risk variants in UCSC Genome Browser. (B) 3C-qPCR was performed in quiescent EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk (NR) or risk (R) haplotype using the anchor fragment (1) and test fragments shown in A (see Supplemental Table 3). Relative interaction frequency (RIF) between the anchor fragment and each test fragment was normalized to the UBE2L3 BAC clone, then to the random ligation control and plotted according to the interaction fragment number from the anchor as mean ± SEM, n=3. Significance was determined using Student’s t-test; * indicates p<0.05.

Risk variants on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype alter CTCF and YY1 transcription factor binding.

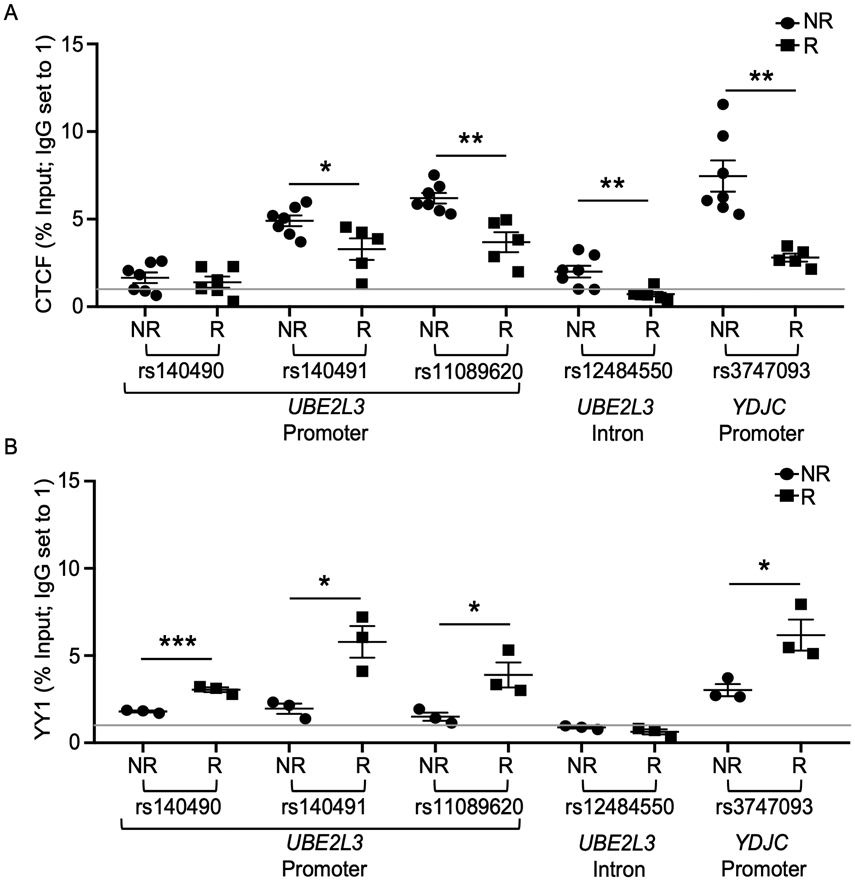

CTCF and YY1 are ubiquitously expressed proteins that function to regulate mammalian gene expression through their influence on three dimensional chromatin organization (33-38). In addition, co-binding of CTCF and YY1 has been shown to regulate gene transcription for a large number of mammalian promoters, with YY1 playing a dominant role in promoting transcription (35). Analysis of transcription factor ChIP-seq clusters from ENCODE revealed CTCF and YY1 binding motifs in the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter regions (Supplemental Figure 7A, C), but not in the UBE2L3 intronic region (Supplemental Figure 7B). Further, UBE2L3 promoter variants, rs140491 and rs11089620, are positioned in the ENCODE reported YY1 binding site (Supplemental Figure 7A) and the YDJC promoter variant, rs3747093, is positioned in an overlapping CTCF and YY1 binding site (Supplemental Figure 7C). Therefore, we hypothesized that the binding of CTCF and/or YY1 might be altered in the presence of the risk alleles. To test this hypothesis, we performed ChIP-qPCR for each variant and observed significantly lower CTCF binding to the risk alleles of rs140491, rs11089620, rs12484550, and rs3747093, relative to the respective non-risk alleles (Figure 4A). CTCF binding to rs140490 was near baseline and exhibited no allele-specific differences. In contrast, we observed significant increases in YY1 binding in the presence of the UBE2L3 (rs140490, rs140491, rs11089620) and YDJC (rs3747093) promoter variant risk alleles compared to the non-risk alleles (Figure 4B). YY1 enrichment was not observed with the UBE2L3 intronic variant, rs12484550. These results suggest that the autoimmune risk alleles exert their effect on UBE2L3 transcription by preferentially binding YY1, at the expense of CTCF, at the promoters of both UBE2L3 and YDJC.

Figure 4. Risk variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype exhibit allele specific binding to CTCF and YY1 transcription factors.

(A-B) ChIP-qPCR was performed in EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk (NR) or risk (R) haplotype using antibodies against (A) CTCF or (B) YY1. Primers were designed to flank indicated variants (see Supplemental Table 4). Rabbit or mouse IgG was used as an isotype control. Data represented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; n = 9 (CTCF) or n = 3 (YY1); * indicates p<0.05; ** indicates p<0.01; ***indicates p<0.001.

Knockdown of YY1 disrupts the UBE2L3-YDJC regulatory network and subsequent UBE2L3 expression.

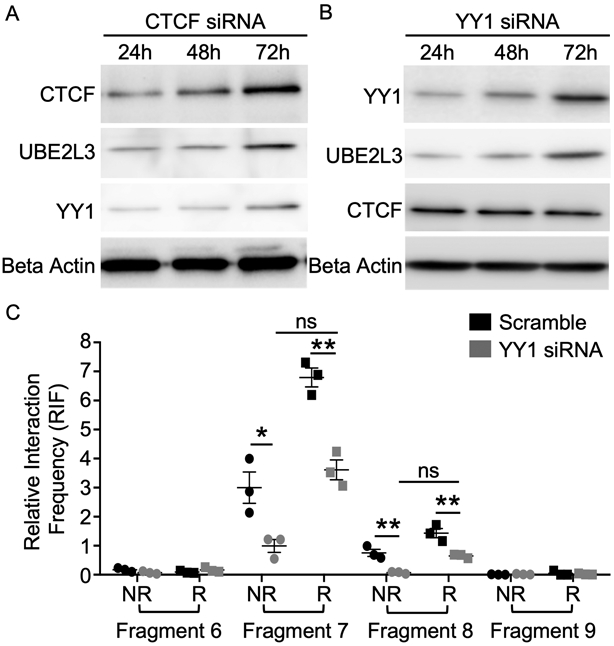

We hypothesized that, if a gain in YY1 binding was responsible for increased interactions between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoter regions and increased UBE2L3 transcription, then loss of YY1 expression would attenuate these interactions. To test this, we transfected EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk haplotype with YY1 or CTCF siRNA, then measured CTCF, YY1 and UBE2L3/UbcH7 protein levels at 24h, 48h and 72h post-transfection. CTCF (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figures 8A, 8B) and YY1 (Figure 5B, Supplemental Figures 8C, 8D) knockdown reached ~80% at 24h, relative to the scrambled control. Interestingly, the transient knockdown of YY1 reduced UBE2L3/UbcH7 expression (Figure 5B, Supplemental Figure 8C, 8D), while CTCF knockdown resulted in the loss of both UBE2L3/UbcH7 and YY1 protein expression (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure 8A, 8B), suggesting that CTCF might be an upstream regulator of YY1 expression. Further, UBE2L3/UbcH7 protein levels paralleled the recovery of both CTCF and YY1 protein expression 72h post-transfection.

Figure 5. YY1 knockdown reduces UBE2L3 expression and impairs the long-range DNA looping between the UBE2L3-YDJC promoters.

(A-B) Western blotting was performed to analyze YY1, UBE2L3, CTCF, and Beta Actin expression at 24h, 48h, and 72h post-transient transfection of CTCF siRNA (A) or YY1 siRNA (B) in EBV B cells with homozygous non-risk UBE2L3-YDJC haplotype. Image is representative of n=3. Expression in scrambled siRNA transfected EBV B cells shown in Supplementary Figure 8A, C. Quantitative densitometry normalized to Beta Actin shown in Supplementary Figure 8B, D. (C) 3C-qPCR performed with scramble (black) or YY1 (gray) siRNA-transfected EBV B cells carrying the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk (NR; circle) or risk (R; square) haplotype. Relative Interaction Frequency (RIF) was normalized to the UBE2L3 BAC clone, then to the random ligation control and plotted as mean ± SEM, n=3. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; * indicates p<0.05; ** indicates p<0.01; ns indicates not significant.

The reduction in UBE2L3/UbcH7 protein expression after YY1 knockdown, despite sustained CTCF protein levels (Figure 5A, 5B), suggests that YY1 binding at the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters likely modulates UBE2L3 expression by promoting long-range interactions. To further assess the effect of YY1 knockdown in mediating the long-range interaction between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters, we performed 3C-qPCR after siRNA-mediated knockdown of YY1 in EBV B cells homozygous for the UBE2L3-YDJC non-risk or risk haplotype. YY1 knockdown significantly decreased the interaction frequency between the UBE2L3 promoter and YDJC promoter (fragments 7 and 8) proportionally in both risk and non-risk EBV B cell lines relative to scramble siRNA transfection (Figure 5C). Although our YY1 knockdown was not allele specific, the experiments do support a mechanism whereby increased binding of YY1 at the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters in the presence of the risk alleles strengthens the interaction between the two promoters and increases expression of UBE2L3.

Genes that share long-range DNA contacts with the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters also demonstrate increased expression in the context of the risk haplotype.

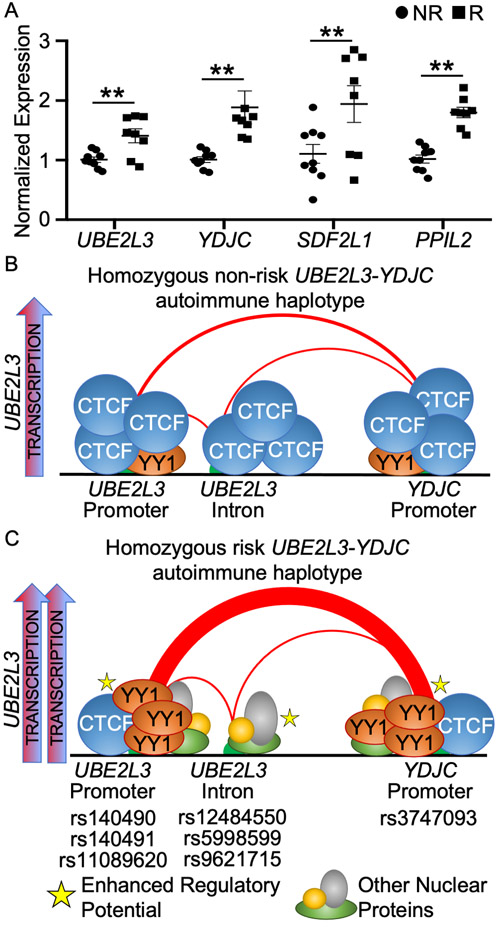

We noticed that our HiChIP analysis also revealed several additional H3K27ac-mediated long-range interactions between anchors in the UBE2L3 locus and genes downstream: YDJC, CCDC116, SDF2L1, PPIL2 (Supplemental Figure 6). Of these, only YDJC, SDF2L1, and PPIL2 demonstrated expression in EBV B cell lines (Supplemental Figure 9), thus we limited our qRT-PCR studies to these three genes and UBE2L3 in EBV B cells homozygous for the risk or non-risk haplotype. We observed the expected increase in UBE2L3 transcript expression, but also found significantly increased expression of YDJC, SDF2L1 and PPIL2 in cells homozygous for the risk haplotype compared with the non-risk haplotype (Figure 6A). These results suggest that the mechanisms defined herein, which result in increased UBE2L3 expression from the autoimmune risk haplotype, extend to a larger chromatin network that includes YDJC, SDF2L1 and PPIL2.

Figure 6. The UBE2L3-YDJC haplotype functions by differentially binding CTCF and YY1 to strengthen interactions between UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters to increase UBE2L3 expression.

(A) qRT-PCR was used to measure the expression of the indicated genes in quiescent EBV B cells homozygous for the non-risk (NR; circle) or risk (R; square) UBE2L3-YDJC haplotype. Expression was normalized to GAPDH in non-risk EBV B cells. Results are the mean ± SEM, n ≥ 8. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test; ** indicates p<0.01. (B, C) Schematic depiction of how risk alleles carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune risk haplotype increase YY1 binding affinity, at the expense of CTCF binding. Increased YY1 binding strengthens a long-distance interaction between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters that facilitates both UBE2L3 and YDJC expression, relative to the non-risk haplotype.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to develop a mechanistic understanding for how functional risk variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC autoimmune disease risk haplotype drive hypermorphic UBE2L3 expression implicated in autoimmune disease pathogenesis. We used a combination of in vitro assays designed to measure the allele-specific regulatory effects of seven risk variants, positioned in regions of high chromatin accessibility in several immune cell types. We discovered that three variants in the UBE2L3 promoter (rs140490, rs140491, rs11089620) and one in the YDJC promoter (rs3747093) likely facilitate the hypermorphic expression effect of the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype by (1) increasing the binding of YY1 over CTCF, (2) strengthening a long-range DNA interaction between the two promoters, and (3) increasing the transcriptional activity of the regulatory network (Figure 6B, C).

YY1 and CTCF are both implicated in transcriptional regulation and stabilization of long-range DNA interactions and chromatin regulatory networks. In primate lymphoblastoid cells, co-bound YY1 and CTCF were shown to be enriched in transcriptionally active regions across the genome, and function to stabilize and modulate transcription within chromatin regulatory networks (35). Further, YY1 was shown to mediate interactions between enhancer and promoter elements to promote global transcription in murine embryonic stem cells (33). In this model, loss of YY1 significantly reduced global gene expression, supporting a role of YY1 as a global regulator of transcription and stability of long-range interactions. Consistently, we observed a loss of UBE2L3 expression in EBV B cells after YY1 siRNA knockdown. Loss of UBE2L3 expression coalesced with reduced long-range interaction frequencies between the UBE2L3 and YDJC promoters in YY1-depleted EBV B cells. Interestingly, we discovered that risk alleles of variants carried on the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype increased YY1 binding and strengthened the long-range interaction between the two promoters. Similar allele-specific changes in the binding affinity of YY1, and subsequent disruptions in enhancer-promoter interactions were reported for several risk variants associated with type I diabetes (37). To our knowledge this is the first report implicating co-bound YY1 and CTCF in the regulation of UBE2L3. Further, given that YY1 is ubiquitously expressed and exhibits global regulation in other cell models, it is tempting to speculate that altered affinity for YY1 may affect gene expression in the context of other autoimmune disease risk haplotypes.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of the following caveats. First, we utilized immortalized cell lines from three different immune cell subtypes to perform in vitro assays to independently assess the allele-specific binding affinity and regulatory function of each selected risk variant, and immortalized cell lines do not precisely replicate the transcriptional regulation of primary immune cells. Second, the in vitro assays precluded our ability to determine how allele-specific effects of each variant function within the context of the native chromatin architecture. However, our observed increase in nuclear protein binding and enhanced regulatory activity for five of the seven risk alleles across all cell types are consistent with the established hypermorphic effect of the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype. Further, these results were internally consistent with 3C-qPCR analyses performed in EBV B cells that demonstrated strengthened DNA looping in the context of the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype. While EBV B cells do not precisely replicate the genomic architecture of primary B cells, they represent an important resource for evaluating allele-specific effects of genetic variants in the context of native chromatin architecture (23,39-41). Lastly, we acknowledge that the bioinformatic approach we used to prioritize candidate variants based on positioning in chromatin accessible regions potentially omitted other functional variants.

Despite these caveats, we successfully characterized five functional variants carried on the largely uncharacterized UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype, and delineated a novel mechanism that explains how the risk haplotype likely drives hypermorphic UBE2L3 expression in autoimmune disease pathogenesis. Further, analysis of available HiChIP data and our qRT-PCR studies suggest the presence of additional, higher order chromatin interactions that may extend the effect of the UBE2L3-YDJC risk haplotype to other genes within the shared 3D chromatin network, including SDF2L1 and PPIL2. Future targeted gene-editing strategies in an isogenic cell line will be important to further elucidate the effects of differential CTCF/YY1 binding on UBE2L3 expression and downstream cellular signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Kiely Grundahl from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Genes and Human Disease Research Program for her technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: R01AR063124, R01AR073606, R01AR056360, P30GM110766, U19AI082714; as well as the Presbyterian Health Foundation. The ORDRCC (source of EBV B cell lines) is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants U54GM104938, P30AR073750 and UM1AI144292. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing interests.

Web Resources

OMIM: http://www.omim.org

UCSC Genome Browser: https://genome.ucsc.edu/

NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/

HiC-Pro: http://github.com/nservant/HiC-Pro

Hichipper: https://github.com/aryeelab/hichipper

DNAlandscaper: https://github.com/aryeelab/DNAlandscapeR

References

- 1.Rittinger K, Ikeda F. Linear ubiquitin chains: Enzymes, mechanisms and biology. Open Biol 2017;7:170026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwai K Linear polyubiquitin chains: A new modifier involved in NFκB activation and chronic inflammation including dermatitis. Cell Cycle 2011;10:3095–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokunaga F, Sakata SI, Saeki Y, Satomi Y, Kirisako T, Kamei K, et al. Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-κB activation. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita H, Rahighi S, Akita M, Kato R, Sasaki Y, Wakatsuki S, et al. Mechanism Underlying IkB Kinase Activation Mediated by the Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex. Mol Cell Biol 2014;34:1322–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis MJ, Vyse S, Shields AM, Boeltz S, Gordon PA, Spector TD, et al. UBE2L3 polymorphism amplifies NF-κB activation and promotes plasma cell development, linking linear ubiquitination to multiple autoimmune diseases. Am J Hum Genet 2015;96:221–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis M, Vyse S, Shields A, Boeltz S, Gordon P, Spector T, et al. Effect of UBE2L3 genotype on regulation of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet 2015;385:S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Genetics (SLEGEN), Harley JB, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet 2008;40:204–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor KE, Chung SA, Graham RR, Ortmann WA, Lee AT, Langefeld CD, et al. Risk alleles for systemic lupus erythematosus in a large case-control collection and associations with clinical subphenotypes. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1001311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentham J, Morris DL, Cunninghame Graham DS, Pinder CL, Tombleson P, Behrens TW, et al. Genetic association analyses implicate aberrant regulation of innate and adaptive immunity genes in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet 2015;47:1457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Adrianto I, Wiley GB, Lessard CJ, Kelly JA, Adler AJ, et al. A functional haplotype of UBE2L3 confers risk for systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun 2012;13:380–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agik S, Franek BS, Kumar AA, Kumabe M, Utset TO, Mikolaitis RA, et al. The autoimmune disease risk allele of UBE2L3 in African American patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A recessive effect upon subphenotypes. J Rheumatol 2012;39:73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun C, Molineros JE, Looger LL, Zhou XJ, Kim K, Okada Y, et al. High-density genotyping of immune-related loci identifies new SLE risk variants in individuals with Asian ancestry. Nat Genet 2016;48:323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orozco G, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Morgan AW, Wilson AG, et al. Study of the common genetic background for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Xie G, Eyre S, Thomson BP, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet 2010;42:508–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature 2014;506:376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubois PCA, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, et al. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet 2010;42:295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fransen K, Visschedijk MC, van Sommeren S, Fu JY, Franke L, Festen EAM, et al. Analysis of SNPs with an effect on gene expression identifies UBE2L3 and BCL3 as potential new risk genes for Crohn’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:3482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franke A, McGovern DPB, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 2010;42:1118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2012;491:119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinks A, Cobb J, Marion MC, Prahalad S, Sudman M, Bowes J, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies 14 new susceptibility loci for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Genet 2013;45:664–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, Ellinghaus E, Stuart PE, Capon F, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet 2012;44:1341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen A, Sevier S, Kelly JA, Glenn SB, Aberle T, Cooney CM, et al. The lupus family registry and repository. Rheumatology 2011;50:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelikan RC, Kelly JA, Fu Y, Lareau CA, Tessneer KL, Wiley GB, et al. Enhancer histone-QTLs are enriched on autoimmune risk haplotypes and influence gene expression within chromatin networks. Nat Commun 2018;9:2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Servant N, Varoquaux N, Lajoie BR, Viara E, Chen CJ, Vert JP, et al. HiC-Pro: An optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol 2015;16:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lareau CA, Aryee MJ. hichipper: a preprocessing pipeline for calling DNA loops from HiChIP data. Nat Methods 2018;15:155–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 2008;9:R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagege H, Klous P, Braem C, Splinter E, Dekker J, Cathala G, et al. Quantitative analysis of chromosome conformation capture assays (3c-qpcr). Nat Protoc 2007;2:1722–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science (80- ) 2002;295:1306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naumova N, Smith EM, Zhan Y, Dekker J. Analysis of long-range chromatin interactions using Chromosome Conformation Capture. Methods 2012;58:192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. ATAC-seq: A method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2015;109:21.29.1–21.29.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klemm SL, Shipony Z, Greenleaf WJ. Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Rev Genet 2019;20:207–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corces MR, Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Greenside PG, Chan SM, Koenig JL, et al. Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nat Genet 2016;48:1193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub AS, Li CH, Zamudio A V., Sigova AA, Hannett NM, Day DS, et al. YY1 Is a Structural Regulator of Enhancer-Promoter Loops. Cell 2017;171:1573–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beagan JA, Duong MT, Titus KR, Zhou L, Cao Z, Ma J, et al. YY1 and CTCF orchestrate a 3D chromatin looping switch during early neural lineage commitment. Genome Res 2017;27:1139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwalie PC, Ward MC, Cain CE, Faure AJ, Gilad Y, Odom DT, et al. Co-binding by YY1 identifies the transcriptionally active, highly conserved set of CTCF-bound regions in primate genomes. Genome Biol 2013;14:R148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pentland I, Campos-León K, Cotic M, Davies KJ, Wood CD, Groves IJ, et al. Disruption of CTCF-YY1–dependent looping of the human papillomavirus genome activates differentiation-induced viral oncogene transcription. PLoS Biol 2018;doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao P, Uzun Y, He B, Salamati SE, Coffey JKM, Tsalikian E, et al. Risk variants disrupting enhancers of TH1 and TREG cells in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:7581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stik G, Vidal E, Barrero M, Cuartero S, Vila-Casadesús M, Mendieta-Esteban J, et al. CTCF is dispensable for immune cell transdifferentiation but facilitates an acute inflammatory response. Nat Genet 2020;52:655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernando H, Shannon-Lowe C, Islam AB, Al-Shahrour F, Rodríguez-Ubreva Javier, Rodríguez-Cortez Virginia C, et al. The B cell transcription program mediates hypomethylation and overexpression of key genes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated proliferative conversion. Genome Biol 2013;doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernando H, Islam ABMMK, Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Forné I, Ciudad L, Imhof A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated transformation of B cells induces global chromatin changes independent to the acquisition of proliferation. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:249–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Çalişkan M, Cusanovich DA, Ober C, Gilad Y. The effects of EBV transformation on gene expression levels and methylation profiles. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:1643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.