Abstract

Despite cardiovascular disease (CVD) being the leading cause of death of women globally, research on CVD over the past several decades has focused primarily on men. CVD research has led to progress in diagnosis and treatment, medical education, and public awareness; however, few of these advances have applied specifically to women’s cardiovascular health. There is a paucity of sex- and gender-specific educational material regarding CVD in clinical training programs for physicians. The irregularity in integrated curricula across medical schools in Canada may be a factor in persistent disparities in clinical care and outcomes experienced by women, compared with men. In response to this gap, the Training and Education Working Group of the Canadian Women’s Heart Health

Alliance undertook the planning, development, and dissemination of a Canadian Women's Heart Health Education Course. The development of the course was guided by a 6-step approach for curriculum development for medical education, which included conducting a needs assessment, determining and prioritizing content, setting goals and objectives, selecting educational strategies, implementation, and evaluation.

Résumé

Bien que les maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) soient la principale cause de décès chez les femmes dans le monde, la recherche sur les MCV au cours des dernières décennies a été centrée principalement sur les hommes. La recherche sur les MCV a permis de faire des progrès en matière de diagnostic et de traitement, de formation médicale et de sensibilisation du public; toutefois, peu de ces progrès touchaient spécifiquement la santé cardiovasculaire des femmes. Les programmes de formation clinique des médecins ne comportent que peu de matériel éducatif sur les MCV propre à chaque sexe et à chaque genre. Il est possible que l’irrégularité des programmes de formation intégrés des écoles de médecine au Canada contribue aux disparités persistantes dans les soins prodigués aux femmes et les résultats cliniques obtenus chez celles-ci, comparativement aux hommes. Pour combler cette lacune, le Groupe de travail sur la formation et l’éducation de l’Alliance canadienne de santé cardiaque pour les femmes a entrepris la planification, la préparation et la diffusion de l’Initiative nationale de sensibilisation à la santé cardiaque des femmes. La conception de l’Initiative a été guidée par une approche en six volets axée sur l’élaboration d’un programme de formation médicale, qui comprenait une évaluation des besoins, la détermination et la hiérarchisation du contenu, la formulation des buts et des objectifs, la sélection des stratégies de formation, ainsi que la mise en œuvre et les modalités d’évaluation.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of hospitalization and preventable death among women in Canada.1 The focus of cardiovascular research over the past several decades has been primarily on men, the results of which have shaped advances in diagnosis and treatment, medical education, and public awareness campaigns regarding CVD. But these advances have not been specific to women.2 We now recognize that care for women has gaps that contribute to women’s morbidity and mortality from CVD. Patient-specific approaches to assessment and care that recognize both the sex and gender of a patient are increasingly recognized as an important objective in contemporary cardiac care.3 Addressing patients’ unique needs, as well as their social determinants of health, must be a priority as health care is transformed in the future. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of sex- and gender-specific educational material regarding CVD diagnosis and management in clinical training programs for physicians. The results of an unpublished 2011 survey—Sex- and Gender-Based Medicine Faculty Survey, as described by Miller and colleagues—administered to 159 medical schools in Canada and the US, show that 70% of respondents indicated having received no formal sex- and/or gender-based curriculum.4 Existing curricular interventions may vary, as presented in Miller and colleagues’ paper, with the most common approach being incorporation of material into specific didactic courses but with limited opportunity for clinical application.4 Contemporary Canadian data are limited, although a recent deductive and summative content analysis of women’s health topics in publicly available programs and course descriptions of Canadian medical schools suggests limited depth and breadth of coverage.5 This gap and inconsistency in integrated curricula across medical schools in Canada may be a factor in persistent disparities in clinical care.

The Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance (the Alliance; www.cwhha.ca) is a volunteer organization comprising health professionals and women living with CVD, whose mission is “to support patients, clinicians, scientists, and decision-makers to implement evidence, transform clinical practices, and impact public policy related to women’s cardiovascular health.” Resulting from the Alliance’s Call to Action meeting in Ottawa in April 2018, sixteen priority initiatives were identified, including the need for an accredited physician education program addressing women and heart disease. The Training and Education Working Group (TEWG) of the Alliance undertook the planning, development, and dissemination of a Canadian Women's Heart Health Education Course in response to this priority, beginning in September 2018. This paper describes the approach taken for this initiative and future evaluation plans.

Methods

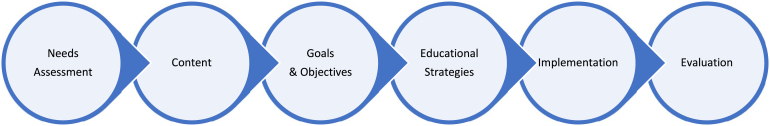

Development of the Canadian Women's Heart Health Education Course was guided by a 6-step approach for curriculum development for medical education, outlined by Thomas et al.6 and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The 6-step approach for curriculum development for medical education: (i) conducting a needs assessment and creating a rationale statement; (ii) determining and prioritizing content; (iii) setting goals and objectives; (iv) selecting teaching/educational strategies; (v) implementation; and (vi) evaluating and summarizing lessons learned.

Needs assessment and rationale statement

Findings from a 2017 cross-sectional national survey of a random sample of 504 physicians (59.9% primary care, 20.2% cardiology, 19.8% obstetrics and gynecology) demonstrated a general lack of awareness of CVD prevalence, identification, risk assessment, and management in women.2 Only 26% of primary care providers and cardiologists surveyed believed they were able to effectively support their female patients in understanding their risk of CVD, and even fewer felt they were effective in providing advice to women on preventing and managing CVD risk factors (eg, blood pressure, ≤ 24%; physical inactivity, ≤ 10%; smoking cessation, ≤ 14%). Most of the physicians surveyed reported not knowing or being unsure of whether standard methods for predicting CVD risk were equally effective in men and women (60%), or whether current cardiac diagnostic tests were more accurate in men, compared with women (53%). However, half indicated a willingness to seek additional training to permit optimal delivery of preventive, heart health interactions with their female patients.

Using as a baseline the previous needs assessment2 that identified knowledge gaps, in December 2018, the TEWG completed an informal pan-Canadian environmental scan of key stakeholders (physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, educators, policymakers, and women living with CVD) within the Alliance to identify perceived gaps in training, education, and dissemination related to sex and gender in cardiovascular health, and preferred strategies to address these issues. The need for disease-based education to help healthcare providers recognize the complex interactions required to understand and treat women's heart health was identified as a priority and thus became the rationale statement for this initiative. Practicing physicians and trainees were the initial primary target audience, with those practicing internal medicine, cardiology, and emergency department specialties identified as priority specialty groups.

Determining and prioritizing content

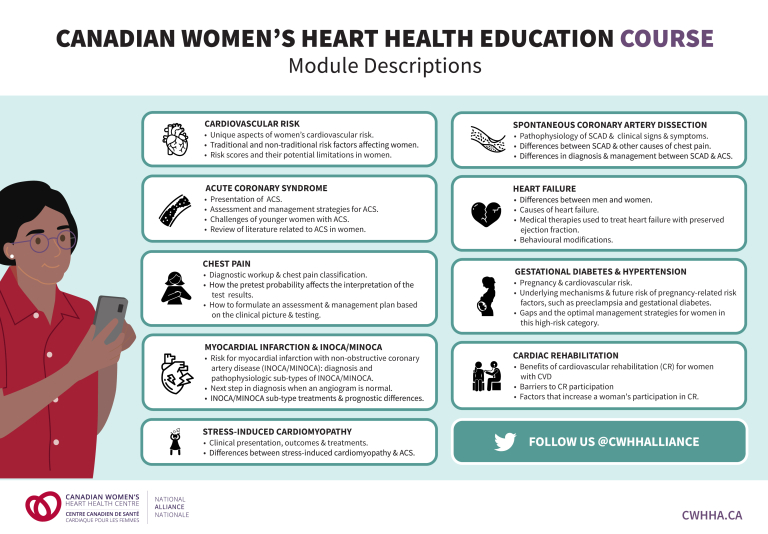

Fourteen members of the TEWG created a work plan for the development and implementation of the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Education Course. The project members included the following: 4 physicians (specialists in cardiology [2], internal medicine [1], emergency medicine [1]); 2 nurse clinician–scientists; 3 medical trainees; 2 cardiac rehabilitation specialists; and 3 women with lived experience. Using the national survey and environmental scan findings, and through a consensus-building process, the TEWG members determined 9 overarching topics to guide the development of the women’s heart health curriculum (Table 1; Fig. 2). A significant determination was that each section would begin with a case outlining a real story related to each topic area presented by a woman with lived experience.

Table 1.

Description of Canadian Women’s Heart Health Education Course modules and learning objectives

| Module title | Learning objectives |

|---|---|

| 1: Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Women—The Role of Risk Factors and Scores |

|

| 2: Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) in Women |

|

| 3: Approaches to Chest Pain—A Sex & Gender Focus |

|

| 4: Myocardial Infarction With Non-obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (MINOCA) |

|

| 5: Stress-Induced Cardiomyopathy (SIC) |

|

| 6: Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) |

|

| 7: Contemporary Management of Women With Heart Failure |

|

| 8: Cardiovascular Risk in Women With Gestational Diabetes & Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy |

|

| 9: Recovery and Cardiac Rehabilitation for Women |

|

Figure 2.

Summary of the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Education Course. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

Writing goals and objectives

A standard structure for the modules was established, and drafts were rigorously peer-reviewed. Members of the TEWG were assigned to write on the topic that best matched their area of expertise. Nine modules were written and peer-reviewed within the TEWG, and subsequently by other members of the Alliance. Table 1 summarizes the learning objectives of each module. Women with lived experience were involved in the development of each module, which added a unique and valuable perspective to these learning tools. The women with lived experience were involved in all aspects of content creation, aligning with the core values for the practice of public participation of the International Association of Public Participation.7 This involved the following aspects: providing patient partners with information needed to be able to participate in a meaningful way; consulting with patient partners for feedback and to aid in decision-making; involving patient partners in content development, editing, and testing; and collaborating with patient partners in the development, presentation, and delivery of the content.

In August 2020, once all modules were drafted, a call was sent out seeking volunteer beta testers to review each module. A total of 51 individuals participated as beta testers, including clinicians/clinician–scientists (n = 20), medical trainees (n = 10), program administrators (n = 3), and women with lived experience (n = 18). Among the clinician evaluators, 17 were from the primary target audience specialties (7 emergency medicine, 6 general internal medicine, 4 cardiology). Evaluators provided direct feedback on content (accuracy, relevance), structure (pace, duration), knowledge (understanding, capacity, and interest), and satisfaction. Modifications to each module were then made based on the beta-testing feedback.

Selecting teaching and educational strategies

In step 4 of the 6-step approach for curriculum development—the selection of teaching and educational strategies—the goal was to disseminate the content to the identified target audiences through a variety of accredited delivery-format options. A web-based, asynchronous, interactive method, using case-based modules, was chosen, to allow flexibility in access and delivery. This strategy promotes student-centreed learning and removes time and space constraints typical of traditional curricula, thus allowing us to reach a heterogenous target audience of healthcare professionals.8 Concurrent with our planning has been the transformation of medical education, due to the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, spurring increasing interest in virtual and online learning strategies. In fact, there has been a recent push for a lecture-free curriculum in health science education, focusing on learning sessions that incorporate retrieval-based practice, elaborative interrogation, self-explanation, and metacognition.9 Accordingly, we have incorporated some of these recommended strategies into the creation of our learning modules. For example, the use of frequent low-stakes test questions within the modules allows learners to better understand their knowledge gaps. Retrieval exercises and spaced repetition of content through these interspersed low-stakes test questions, which are reviewed and answered at the end of the module, further enhance learning. This curriculum will be either self-directed or taught by stakeholders with expertise and interest in the course. Access will be via a virtual course, as well as a teaching toolkit for those with the opportunity to meet face-to-face with their learners.

Implementation of the curriculum

Our implementation plan aims to reach targeted audiences across Canada, in a 2-phased approach. Phase 1 of the rollout will target trainees in general internal medicine, cardiology, and emergency medicine. Phase 2 will target physicians in primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency medicine, general internal medicine, and cardiology, as well as nurses and allied health professionals. Promotion of the course will be accomplished primarily through program directors across the various medical schools in Canada, as well as local champions at each centre. The modules were designed to be delivered flexibly, either as a full program or independently on a modular basis, to adapt to different needs, goals, and environments. In other words, both synchronous and asynchronous delivery options are available. The curriculum is intended to be included in Grand Rounds and other routine teaching opportunities that are already available to residents. Should trainees wish to pursue an asynchronous option, they can opt to complete the modules via prerecorded sessions on their own time or during research blocks. The program has been accredited as a Group Learning Activity (Section 1) as defined by the Maintenance of Certification Program of the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada and has also been approved by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society. The Alliance education course is now available online at CWHHA.ca.

Future evaluation

The Canadian Women’s Heart Health Education Course evaluation plan includes a short-term evaluation of training effectiveness (immediately following completion of any module, and within 1-2 months of training rollout) and a longer-term evaluation (within 3-6 months of training rollout), based on the Kirkpatrick Model of training evaluation.10 The short-term evaluation will measure learner reaction, knowledge, and satisfaction using embedded post-session questionnaires for each module (for sample questionnaire, see Supplemental Appendix S1). We acknowledge that resultant changes in learner behaviour and long-term outcomes such as improved patient care are more difficult to measure; however, these will be assessed through a delayed questionnaire (3-6 months after module participation) on self-reported practice changes made by learners and their perception of the impact of this educational module on patient care.

Conclusion

We have described the development of unique sex- and gender-specific training courses for CVD, in response to an identified gap in medical education, that were based on a review of the latest evidence and the experiences of cardiovascular specialists and women living with CVD. With educational interventions making an important contribution to closing care gaps, our process could be replicated in the development of health professional education for other diseases or conditions. Changes in clinical training and continuing education programs are needed, so that physicians acquire the up-to-date knowledge about sex and gender differences relevant to the prevention and management of CVD in women. Changing physicians’ knowledge and behaviour is a necessary step if we are to improve standards of cardiac care in women. Improved education of physicians, dissemination of appropriately developed guidelines, development of novel protocols for identifying those at risk, and application of clinical decision support tools are necessary if we are to enhance the cardiovascular health of Canadian women.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the course module authors—Dr Carolyn Baer, Nadia Lappa, Dr Judy Luu, Helen Robert, Dr Michele Turek, Dr Anita Pozgay, Helena Van Ryn, Dr Stephanie Poon—and thank Kelly Tucker, Nicole Nickerson, Marie Del Rosario, and all the other women with lived experience who contributed their stories to this project. We thank the following staff and members of the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance: Melissa Core-Gunn (webinar recording, editing); Manu Sandhu (graphic design); Anice Wong (reviewing, website content); and the beta testers who provided time and thoughtful editing of the course content.

Funding Sources

This project was supported through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Planning and Dissemination grant (PCS 164947) and through funding from the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Centre (University of Ottawa Heart Institute Foundation).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: The research reported has adhered to all ethical guidelines.

See page S191 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2021.09.020.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Jaffer S., Foulds H.J.A., Parry M., et al. The Canadian Women's Heart Health Alliance ATLAS on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiovascular disease in women; Chapter 2: scope of the problem. CJC Open. 2021;3:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonnell L.A., Turek M., Coutinho T., et al. Women’s heart health: knowledge, beliefs, and practices of Canadian physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:72–82. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris C.M., Yip C.Y.Y., Nerenberg K.A., et al. State of the science in women's cardiovascular disease: a Canadian perspective on the influence of sex and gender. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller V.M., Rice M., Schiebinger L., et al. Embedding concepts of sex and gender health differences into medical curricula. J Women's Health. 2013:194–202. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson N.N., Gagliardi A.R. Medical student exposure to women’s health concepts and practices: a content analysis of curriculum at Canadian medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:435. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02873-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas P.A., Kern D.E., Hughes M.T., Chen B.Y. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Association for Public Participation Core Values for the Practice of Public Participation. https://www.iap2.org/page/corevalues Available at:

- 8.Lawn S., Zhi X., Morello A. An integrative review of e-learning in the delivery of self-management support training for health professionals. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:183. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmelee D., Roman B., Overman I., Alizadeh M. The lecture-free curriculum: setting the stage for life-long learning: AMEE Guide No. 135. Med Teach. 2020;42:962–969. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1789083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick J.D., Kayser Kirkpatrick W. ATD Press; Alexandria, VA: 2016. Four Levels of Training Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.