Abstract

To evaluate the probiotic characteristics and safety of Enterococcus durans isolate A8-1 from a fecal sample of a healthy Chinese infant, we determined the tolerance to low pH, survival in bile salts and NaCl, adhesion ability, biofilm formation, antimicrobial activity, toxin gene distribution, hemolysis, gelatinase activity, antibiotic resistance, and virulence to Galleria mellonella and interpreted the characters by genome resequencing. Phenotypically, E. durans A8-1 survived at pH 5.0 in 7.0% NaCl and 3% bile salt under aerobic and anaerobic condition. The bacterium had higher adhesion ability toward mucin, collagen, and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in vitro and showed high hydrophobicity (79.2% in chloroform, 49.2% in xylene), auto-aggregation activity (51.7%), and could co-aggregate (66.2%) with Salmonella typhimurium. It had adhesion capability to intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells (38.74%) with moderate biofilm production and antimicrobial activity against several Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria. A8-1 can antagonize the adhesion of S. typhimurium ATCC14028 on Caco-2 cells to protect the integrity of the cell membrane by detection of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and AKP activities. A8-1 also helps the cell relieve the inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide by reducing the expression of cytokine IL-8 (P = 0.002) and TNF-α (P > 0.05), and increasing the IL-10 (P < 0.001). For the safety evaluation, A8-1 showed no hemolytic activity, no gelatinase activity, and had only asa1 positive in the seven detected virulence genes in polymerase chain reaction (PCR), whereas it was not predicted in the genome sequence. It was susceptible to benzylpenicillin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, tigecycline, nitrofurantoin, linezolid, vancomycin, erythromycin, and quinupristin/dalofopine except clindamycin, which was verified by the predicted lasA, lmrB, lmrC, and lmrD genes contributing to the clindamycin resistance. The virulence test of G. mellonella showed that it had toxicity lower than 10% at 1 × 107 CFU. According to the results of these evaluated attributes, E. durans strain A8-1 could be a promising probiotic candidate for applications.

Keywords: Enterococcus durans, stress tolerance, probiotic characters, safety evaluation, whole-genome sequencing

Introduction

Gut microbiota contributes a lot to human health and the occurrence of diseases. It is called the “invisible endocrine organ,” which is the place where the body digests food and absorbs nutrients (Scarpellini et al., 2010). Enterococcus, as one of the indigenous bacteria in the intestine, belongs to the class of facultative anaerobic lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Enterococcus spp. is distributed widely and can be separated from the environment, food, and human and animal gastrointestinal tract and has strong resistance to harsh stress and can survive at different conditions (Starke et al., 2015; Cirrincione et al., 2019).

Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms which consumes in sufficient amounts, affect beneficially the health of the host [sic].” Enterococci have biological properties of probiotics; some strains usually show high resistance to acids and bile salts (Gu et al., 2008), antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity, improve host immunity by intestinal adhesion and localization (Starke et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018), and enhance apoptosis of human cancer cells (Nami et al., 2014); at the same time, some strains have antibacterial activity and anti-inflammatory effects (Popović et al., 2019). With the continuous discovery and exploration of the probiotic characteristics of Enterococcus, many strains have proven to be effective and safe and developed into applications, such as the commercial microecological probiotics in human (Medilac-Vita®, live Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium) and veterinary medicine (Bonvital®, E. faecium DSM 7134) (Li et al., 2020), and the food industry (Cernivet®, E. faecium SF68®; Symbioflor®, E. faecalis) (Strompfová et al., 2004).

At the same time, Enterococcus has both probiotic character and potential pathogenicity, and some strains can cause important infections and diseases, such as endocarditis; bacteremia; and urinary, intra-abdominal, pelvic infections, and central nervous system infections (O’Driscoll and Crank, 2015). It is generally known that antibiotic resistance and virulence are the main factors for enterococci pathogenicity. The main concern for the safety evaluation of enterococci is focused on the potential infectivity and transferable drug-resistant genes (Yang et al., 2015). Pathogenic enterococci may cause concerns about the safety using of probiotics, so to screen the potential probiotic enterococci, assessing and evaluating the safety is necessary and a priority.

Enterococcus is one of the most controversial LAB (Martino et al., 2018). The development of new enterococcal probiotics needs a strict assessment with regard to safety aspects for selecting the truly harmless strains for safe applications. The potential probiotic enterococci isolates can be applied to biotechnology development, and a broader application can be obtained by strain improvement. The aim of this study was to evaluate the probiotic characteristics and safety of E. durans A8-1 isolated from a fecal sample of a healthy Chinese infant and its potential in future probiotic development and application.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Cell Culture

Enterococcus durans A8-1 were isolated from a fecal sample by the microbiology lab of the Nutrition and Food Safety Engineering Research Center of Shaanxi province, Xi’an, China. Fecal samples were taken from a healthy infant born 1–7 days earlier at the Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Bin County of Shaanxi province, China. There was no history of being treated with antibiotics after birth. The fecal sample was collected after the informed consent form was signed by the guardian. This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Health Science Center, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China (No. 2016114).

Enterococcus durans A8-1, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG BL379, and Bifidobacterium infantis CICC6069 were inoculated into de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) medium (CM187, Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and incubated aerobically with constant temperature shaker at 37°C for 18–24 h. About the streak-plating growth, A8-1 and BL379 were cultured on MRS agar using MRS broth with 15 g/L agar for 18 h. For the anaerobic culture, the bacterial cells were inoculated on the same medium and incubated in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, United States) with a modified atmosphere of 82% N2, 15% CO2, and 3% H2 without shaking. For the growth of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, P. aeruginosa ATCC27853, Enterococcus hormaechei ATCC700323, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC14028, and Escherichia coli ATCC35218, nutrient broth was used (CP142, Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Caco-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM, Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) without antibody. The cells were kept at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Isolation and Identification of A8-1

One gram of stool sample was mixed with 0.9% sterile saline solution to a final volume of 10 mL, and 0.1 mL of this dilution was spread on the MRS agar plate (MRS broth with 15 g/L agar) and cultured anaerobically at 37°C for 48 h. After incubation, colonies were randomly selected from each sample and subcultured on MRS plates for further analysis. Single colonies were picked out for Gram staining and microscopic observation and catalase, oxidase production, and nitrate reduction tests (Mansour et al., 2014).

For further confirmation, the 16S rRNA gene sequence (1.4 kb) was amplified, and sequenced by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. Primers used were 16S-27F: 5′ AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG 3′, 16S-1492R: 5′ GGT ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT 3′. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 60 s, and a final elongation step of 5 min at 72°C. Multiple alignments with sequences of closest similarity were analyzed using CLUSTAL W, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining method.

Acid, NaCl, and Bile Salt Tolerance

A8-1 was inoculated into MRS broth at 37°C overnight in an aerobic incubator and anaerobic chamber separately. The overnight culture was centrifuged, and the collected cells were washed twice by sterile phosphate buffered solution (PBS) and resuspended in OD600 = 0.1 at fresh MRS with different pH 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0; bile salts (0.5, 1, 2, and 3%) and NaCl (1.75, 3.5, and 7%). The negative control was MRS blank medium at pH 6.5. Three replicates were set for each medium. Growth was monitored by optical density at 600 nm every 30 min at 37°C for 21 h in a microtiter plate reader (PolarStar, BMG Labtech, Germany) (Banwo et al., 2013; Li et al., 2020). Maximal growth, the lag phase duration, and the increment in OD values were considered by using the Gompertz growth analysis mode of non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism 7 (Wang et al., 2020).

Antibacterial Ability

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method was used to determine the antibacterial activity of A8-1. The indicator bacteria were as follows: E. faecalis ATCC29212, S. aureus ATCC25923, P. aeruginosa PA01, P. aeruginosa ATCC27853, E. hormaechei ATCC700323, S. typhimurium ATCC14028, and E. coli ATCC35218. A8-1 was inoculated into MRS broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The cells were removed by centrifugation at 9,710 × g for 2 min at 4°C. The supernatants were filter sterilized and added to 96-well plates at 0, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μL, made up to 200 μL with fresh medium. Finally, each test indicator bacteria was added to the well at the concentration of OD600 = 0.1. Growth of test indicator bacteria was monitored every 30 min by optical density at 600 nm with an automatic microplate reader for 12 h at 37°C (Wang et al., 2020).

In vitro Hydrophobicity, Auto-Aggregation, and Co-aggregation

The hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, and co-aggregation assays were performed according to Fonseca et al. (2021). The cell surface hydrophobicity of each strain was assessed by measuring microbial affinity to xylene and chloroform. The A8-1 was incubated overnight and washed in PBS twice, and then resuspended in PBS with OD600 of 0.8 (A0). Then, 1 mL xylene and 1 mL chloroform were added separately to 3 mL of A8-1 cell suspension and mixed thoroughly. Then, the water and xylene phases were separated for 30 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase was removed, and the new OD600 was measured (A1). The cell surface hydrophobicity (%) was calculated using the following formula: Hydrophobicity (%) = [(A0−A1)/A0] × 100%. The strain was classified into low (0–29%), moderate (30–59%), and high hydrophobicity (60–100%).

For auto-aggregation, A8-1 was incubated overnight and washed in PBS twice and then resuspended in PBS with OD600 about 0.6 (A0). Bacterial cell suspensions were vortexed for 10 s and subsequently incubated at room temperature for 5 h, and the new OD600 was measured (At). The auto-aggregation percentage was determined using the following equation:

For co-aggregation, E. durans A8-1 and S. typhimurium ATCC14028 were incubated overnight separately and washed in PBS twice and then resuspended in PBS with OD600 about 0.8. Equal volumes (2 mL) of A8-1 and S. typhimurium ATCC14028 were mixed and incubated at room temperature without agitation for 5 h. Control tubes contained 2 mL of the suspension of each bacterial cells. The OD600 of the mixtures and controls were measured after incubation. The percentage of co-aggregation was calculated using the following formula: Co−aggregation (%) = [(Ax + Ay)/2−A(x + y)]/(Ax + Ay) × 100%, where Ax and Ay refer to the OD600 of the A8-1 and S. typhimurium ATCC14028 cell suspension, respectively, Ax + y represents the absorbance of the mixed bacterial suspension tested after 5 h.

In vitro Binding to Bovine Serum Albumi, Mucin, and Collagen

Strain binding to different substrates was evaluated as reported previously (Muñoz-Provencio et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2020). Mucin (500 μg/mL, porcine stomach, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), Bovine Serum Albumi (BSA) (500 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), and collagen (50 μg/mL, type I, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were added separately to the 96-well microplates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Then, wells were washed three times with PBS and dried at room temperature. Two milliliters of A8-1 were labeled by 20 μL cFDA [5-(6-)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States] to the plate wells. After mixing, the cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and kept away from light. The strain labeled by cFDA was added to the plate wells and separately incubated with immobilization at 4°C overnight and kept away from light. After incubation, each well was washed three times by PBS and dried at room temperature. The 100 μL cFDA-labeled A8-1 cells were added into wells with no immobilization and set as control. Fluorescence intensity of the well plate was measured by a microplate reader, and the adhesion rate of A8-1 cells to mucin, collagen, and BSA was calculated according to the following formula. L. rhamnosus GG BL379 was used as a positive control; its adhesion rate was set as 100%, and the relative adhesion of A8-1 cell to BL379 was calculated.

Adhesion (%) = (fluorescence intensity of A8-1)/(the free cFDA-labeled BL379) × 100.

Adhesion Ability to Caco-2 Cells

The A8-1 was incubated overnight and washed in PBS twice and then resuspended in 1 mL DMEM medium (without antibiotic) with a final concentration of 107 CFU/mL. Caco-2 cells cultured by high-glucose DMEM were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C. The 200 μL of A8-1 suspension was added to each well containing Caco-2 cells and then incubated for 2 h. Caco-2 cells with DMEM was set as control. The Caco-2 cells were collected and washed three times by PBS to remove the unadhered A8-1. Then, trypsin was added to Caco-2 cells to lyse the adherent A8-1. Finally, the mixture of each well was cultured on an MRS solid plate to count the adhered bacteria (Nami et al., 2014; Popović et al., 2019).

The adhesion (%) = [(CFU/mL) adhered bacteria/(CFU/mL) added bacteria] × 100.

Antibiotic Susceptibility

VITEK 2 Compact with AST-GP67 (REF 22226, bioMererieux, France) was used to access the antimicrobial susceptibility of the A8-1 to 15 clinical antibiotics, which included penicillin (PEN, 0.125–64 μg/mL), ampicillin (AMP, 0.5–32 μg/mL), high-level gentamicin (synergistic) (HLG, 500 μg/mL; GEN, 8–64 μg/mL), high-level streptomycin (HLS, 1,000 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 1–4 μg/mL), levofloxacin (LVX, 0.25–8 μg/mL), moxifloxacin (MXF, 0.25–8 μg/mL), erythromycin (ERY, 0.25–2 μg/mL), clindamycin (CLI, 0.15–2 μg/mL), quinupristin/dalofopine (QDA, 0.25–2 μg/mL), linezolid (LZD, 0.15–2 μg/mL), vancomycin (VAN, 1–16 μg/mL), tetracycline (TET, 0.15–2 μg/mL), tigecycline (TGC, 0.25–1 μg/mL), and nitrofurantoin (NIT, 16–64 μg/mL). According to the MIC obtained, the results were judged according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute criteria (CLSI M100 S28) (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) for assessment of bacterial resistance to antimicrobials (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed [FEEDAP], 2012).

Hemolysis and Gelatinase Activity

Hemolytic activity of A8-1 was evaluated as described previously (Maturana et al., 2017). A8-1 was inoculated on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% (v/v) sheep blood and cultured at 37°C for 48 h. The hemolysis of single colonies on the plate was observed. Hemolytic activity can be divided into α-hemolysis, β-hemolysis, and γ-hemolysis.

Overnight cultured A8-1 was inoculated into gelatin medium (120 g/L gelatin, 5 g/L peptone, and 3 g/L beef extract, pH 6.8 ± 0.2) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Then, the tube was placed at 4°C for 1 h and it was observed whether there is liquefaction immediately. If the bacteria could produce gelatinase, there was liquid in the tube.

Quantitative Assessment of Biofilm Formation

Quantitative assessment of biofilm formation was evaluated as shown previously (Zhang et al., 2016). Overnight bacterial cultures were washed with PBS twice and adjusted to OD600 = 1.0. The 50 μL of bacterial suspension was added to 150 μL of fresh MRS broth and incubated in 96-well plates at 37°C for 24 h. Also, 200 μL of MRS broth without bacteria was set as negative control. After 24 h, the culture medium was poured out. The wells were washed with sterile PBS three times to remove free-floating planktonic bacteria and then dried at room temperature. The biofilm was then fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet. The control hole was rinsed with sterile water three times until it turned colorless. Then, 200 μL ethanol was added into each well, and optical density of stained adherent cells was measured at 595 nm by microplate reader. According to the cutoff OD (ODC), the biofilm-producing ability was determined as follows: OD ≤ ODC set as non-biofilm-producer (0), ODC < OD ≤ 2ODC set as weak biofilm producer (+), 2ODC < OD ≤ 4ODC set as moderate biofilm producer (++), and OD > 4ODC set as strong biofilm producer (+++).

Virulence Gene and Virulence Activity Assay

The presence of virulence genes of A8-1 were detected by PCR, which included gelE (gelatinase), cylA (cytolysin), hyl (hyaluronidase), asa1/agg (aggregation substance), esp (enterococcal surface protein), efaA (endocarditis antigen), and ace/acm (collagen adhesion) (Wang et al., 2020). The primers and PCR conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

For the virulence activity assay, tests in wax moth (Galleria mellonella) larvae were arranged (Martino et al., 2018). The G. mellonella larvae weighing about 300 mg (purchased from Tianjin Huiyude Biotech Company, Tianjin, China) were maintained on woodchips in the dark at 15°C until being used. The overnight cultures of E. durans A8-1, E. faecalis ATCC29212, and B. infantis CICC6069 suspension were adjusted with concentrations of 1 × 106, 1 × 107, and 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Ten randomly selected larvae were used in each group. Each larva was inoculated the bacterial suspension via the rear left proleg using a 10 μL Hamilton animal syringe. The MRS medium was injected into the larvae and set as negative control. The treated G. mellonella larvae incubated at 37°C for 3 days, and the survival rate of the G. mellonella were recorded every 12 h.

Impact of A8-1 on the Caco-2 Cell Membrane Integrity

Caco-2 cells were seeded into 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) and cultivated to a single layer. For the treatment, there were three treatment groups, S-A8-1 (competition group), A8-1 + S (exclusion group), and S + A8-1 (replacement group). S-A8-1, 1 × 107 CFU/mL S. typhimurium ATCC14028 and 1 × 107 CFU/mL A8-1 culture were added into the cell wells at the same time and incubated for 2 h; A8-1 + S, 1 × 107 CFU/mL A8-1 culture were added into the cell wells and incubated for 2 h and then 1 × 107 CFU/mL S. typhimurium ATCC14028 was added and incubated for another 2 h; S + A8-1, 1 × 107 CFU/mL S. typhimurium ATCC14028 culture was added into the cell wells and incubated for 2 h and then 1 × 107 CFU/mL A8-1 added and incubated for another 2 h. Finally, 1 × 107 CFU/mL S. typhimurium ATCC14028 incubating solely with Caco-2 cells for 2 h was set as control. After incubation, the cell wells were washed three times by PBS to remove the unadhered S. typhimurium ATCC14028 cells. The amount of adhered S. typhimurium ATCC14028 to the Caco-2 cells were counted by bismuth sulfite agar plate (Popović et al., 2018; Kouhi et al., 2021). The inhibition rate of S. typhimurium adhesion to Caco-2 was calculated as:

Inhibition rate (%) = the counted adhered S. typhimurium ATCC14028 in treatment group (CFU/mL)/the counted adhered S. typhimurium ATCC14028 in control (CFU/mL).

Caco-2 cells were cultured and treated as mentioned into four treatment groups (S. typhimurium ATCC14028, A8-1, A8-1 + S, S + A8-1) and one control. After incubation, the supernatant of cell culture was collected after centrifuging at 1,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The activity of extracellular alkaline phosphatase (AKPase) was assayed in the collected supernatant using a kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) as described (Lv et al., 2020). The AKPase unit was defined as 1 mg of phenol produced by 100 mL of cell culture supernatant reacted with the substrate at 37°C for 15 min. Cells treated with the same amount of sterile water were used as negative control. The release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium through damaged membranes was measured spectrophotometrically using a LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit Nanjing Jiancheng Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (García-Cayuela et al., 2014).

Anti-inflammation Study Using Caco-2 Cells

Measurement of Cell Viability by 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide

It was carried out as described previously by Carasi et al. (2017). An 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay was used to monitor cell viability. Briefly, Caco-2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well). After treatment, cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 5 mg/mL MTT working solution for 4 h at 37°C. Then, the supernatant was removed, and the culture was resuspended in 150 μL of DMSO to dissolve MTT formazan crystals, followed by mixing on a shaker for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. The effect of A8-1 culture and Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) on cell viability was assessed as the percentage of viable cells in each treatment group relative to untreated control cells, which were arbitrarily assigned a viability of 100%.

Measurement of Cell Cytokines by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay and q-PCR

Quantification of cytokine levels in cell culture supernatants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Mansour et al., 2014). Caco-2 cells were added into a 24-well cell culture plate according to 1 × 105 cell/well and incubated until the cells grew to monolayer. There were two treatment groups, A8-1 + LPS and LPS + A8-1. For the A8-1 + LPS group, 2.5 × 106 CFU A8-1 cells were added into Caco-2 cells and incubated for 6 h; the wells were washed three times by PBS, and 1 mL fresh DMEM was supplied and then 10 μg LPS was added and incubated for another 6 h. For the LPS + A8-1 group, 10 μg LPS was added into Caco-2 cells and incubated for 6 h; the wells were washed three times by PBS, and 1 mL fresh DMEM was supplied and then 2.5 × 106 CFU A8-1 cells were added and incubated for another 6 h. The different treated Caco-2 cells and cell culture supernatant were collected at 6 and 12 h, separately. The contents of IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α in the supernatant were detected by an ELISA kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell RNA extraction and relative mRNA expression of IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α were determined according to the instructions of corresponding kits (Sigma-Aldrich). GAPDH was selected as the internal reference gene, and the relative mRNA expression levels of IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α were calculated according to the 2–Δ Δ CT method. The untreated Caco-2 cells were used as control, and all tests were performed in triplicate.

Whole-Genome Sequence of A8-1

Whole-genome DNA of A8-1 was extracted by a kit (Applied Biosystems® 4413021). The DNA concentration and purity was quantified with the NanoDrop2000. It was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq™2000 platform at Gene de novo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The reads were de novo assembled by SOAPdenovo version 2.04, Li et al. (2009) and the genome sequence was improved by GapCloser. For the analysis of specific gene sequences, such as virulence genes, heavy metal resistance genes, antibiotic resistance genes, and efflux gene sequences in the bacterial genome, the genomes were analyzed and retrieved in the BIGSdb.1 The predicted genes of E. durans A8-1 were compared with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD)2 (McArthur et al., 2013) and virulence factors database (VFDB)3 (Chen et al., 2016) for identifying antibiotic resistance and virulence factors. Furthermore, the ResFinder 3.04 (Zankari et al., 2012) and PathogenFinder 1.15 (Cosentino et al., 2013) were used for identifying the acquired antibiotic resistance genes and pathogenicity factors, respectively. Clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and prophage sequences were identified by CRISPR Finder6 (Grissa et al., 2007). The genome sequences have been submitted to antiSMASH bacterial version7 to search for the secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters.

Statistical Analysis

The test and analysis of variance (ANOVA), STAMP10, GraphPad Prism 7, and SPSS V20.0 (IBM Inc., IL, United States) were used to perform statistical analyses. Data were presented as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered significant differences.

Results

Isolation and Identification of A8-1

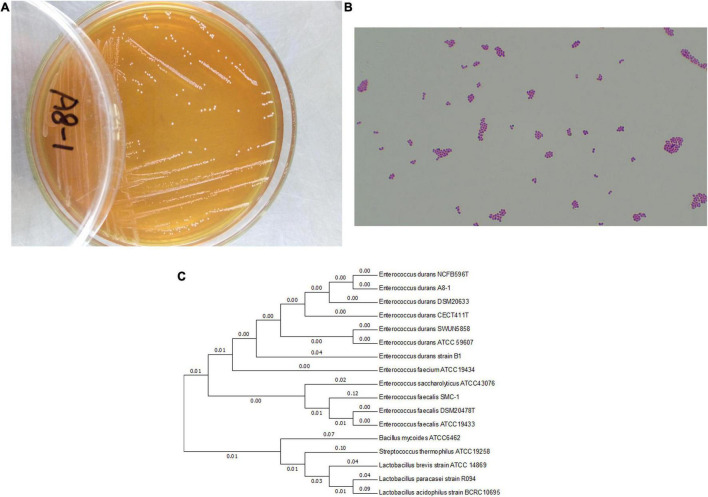

The Gram-positive and cocci-shaped bacteria were selected from a fecal sample of healthy infants. The colony morphology had a sticky, translucent white and mucoid appearance on MRS agar. Except cell morphology, Gram staining (G+), catalase (negative) and oxidase production (negative), nitrate reduction test (negative), a final strain of A8-1 was confirmed by 16S rRNA sequence analysis (Figures 1A–C). The 16S rRNA was submitted to NCBI with the accession number of MH385353.

FIGURE 1.

The growth of Enterococcus durans A8-1 on MRS plate (A); the Gram staining observation at microscope (B) (Olympus CX23, 40×); and phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences (C), which was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method and conducted in MEGA7.

Analysis of Probiotic Characteristics of Enterococcus durans A8-1

Acid and Bile Salt Tolerance Under Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditions

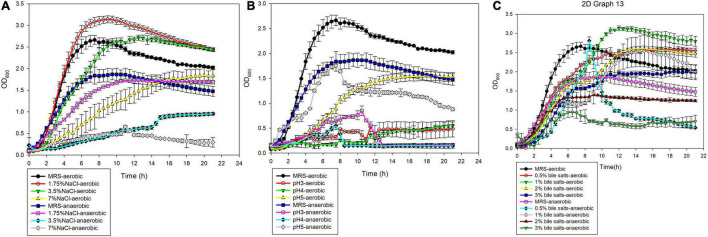

A8-1 had different tolerance in different environments in our experiment. Under aerobic conditions, A8-1 could survive at pH 5.0 in MRS medium, and the maximum cell density reached about 50% of the density in normal MRS under aerobic conditions (Figure 2). A8-1 showed great tolerance to bile salt and NaCl. It was found that the growth of A8-1 in 1.75 and 3.5% NaCl was better than that in MRS (ODmax: 2.841 vs. 2.322, P < 0.05; 2.619 vs. 2.322, P < 0.05). The maximum biomass of A8-1 in a 0.5, 1, and 2% bile salt environment were higher than that of the control group (Figure 2A). Under anaerobic conditions, the maximum OD600 of A8-1 was close to the control at pH 5.0 (Figure 2B), and the strain could grow well under 1% bile salt (ODmax: 2.497 vs. 1.713, P < 0.01) and 1.75% NaCl (ODmax: 1.739 vs. 1.713, P > 0.05) (Figure 2C). Under aerobic conditions, compared with the MRS control group, the lag phase of A8-1 was the shortest at 2% bile salts and 7% NaCl, was delayed under pH 5. Under anaerobic conditions, compared with MRS control, the lag phase of A8-1 was the shortest at 1% bile salt, and the lag phase of A8-1 was shortened with NaCl added (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

In vitro tolerance of Enterococcus durans A8-1 under aerobic and anaerobic conditions with (A) 1.75, 3.5, and 7% NaCl; (B) pH 3, 4, and 5; (C) 0.5, 1, 2, and 3% bile salts.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of acid, NaCl, and bile salt tolerance of Enterococcus durans A8-1 cultured at aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

| Medium | Aerobic |

Anaerobic |

||||

| ODmax | LSD (h) | R 2 | ODmax | LSD (h) | R 2 | |

| MRS | 2.322 | 1.5944 | 0.9266 | 1.713 | 0.6206 | 0.9375 |

| 1.75% NaCl | 2.841 | 1.6536 | 0.948 | 1.739 | 0.3693 | 0.9947 |

| 3.5% NaCl | 2.619 | 1.5034 | 0.9889 | 0.396 | 0.5392 | 0.7078 |

| 7% NaCl | 1.974 | 1.1152 | 0.9982 | 1.418 | 0.2969 | 0.9764 |

| pH 3 | 0.476 | NA* | NA | 0.5662 | NA | NA |

| pH 4 | 1.513 | 1.1036 | 0.9363 | 0.209 | NA | NA |

| pH 5 | 1.585 | 2.1805 | 0.9927 | 1.234 | 0.933 | 0.5311 |

| 0.5% Bile salts | 2.539 | 1.0611 | 0.9956 | 1.104 | NA | NA |

| 1% Bile salts | 3.018 | 1.496 | 0.9735 | 2.497 | 0.1764 | 0.9209 |

| 2% Bile salts | 2.595 | 0.7329 | 0.9825 | 1.288 | 0.8741 | 0.9382 |

| 3% Bile salts | 1.97 | 1.5058 | 0.9946 | 0.704 | NA | NA |

*NA, not fit for the Gompertz growth curve analysis.

In vitro Adherence Assay

Compared with L. rhamnosus GG BL379 (positive control), A8-1 showed higher adhesion to mucin (P < 0.01), BSA (P < 0.01), and collagen. The adhesion ability of A8-1 to mucin, collagen, and BSA was 5.2, 1.6, and 5.6 times higher than L. rhamnosus GG BL379. For the adhesion to Caco-2 cells, the adhesion of A8-1 was 38.47%, which is higher than L. rhamnosus GG BL379 (38.47 vs. 11.7%, P < 0.05) determined in our study.

For the surface adhesion ability, A8-1 showed a high hydrophobicity of 79.2 ± 3.1% in chloroform and moderate hydrophobicity of 49.2 ± 4.4% in xylene; it had 51.7 ± 4.5% for the auto-aggregation after 5 h of incubation and was able to co-aggregate with S. typhimurium with a co-aggregation percentage of 66.2 ± 2.9%.

Antibacterial Activity Analysis

The fermentation supernatant of A8-1 showed different antibacterial activity against the indicator strains for P. aeruginosa PA01 and E. coli ATCC35218, the MIC was 25 μL supernatant, and for the S. aureus ATCC25923, P. aeruginosa ATCC27853, E. hormaechei ATCC700323, S. typhimurium ATCC14028, the MIC was 50 μL supernatant.

Protect Effect to the Caco-2 Cell

Protection Effect of A8-1 to the Caco-2 Cell Membrane Integrity

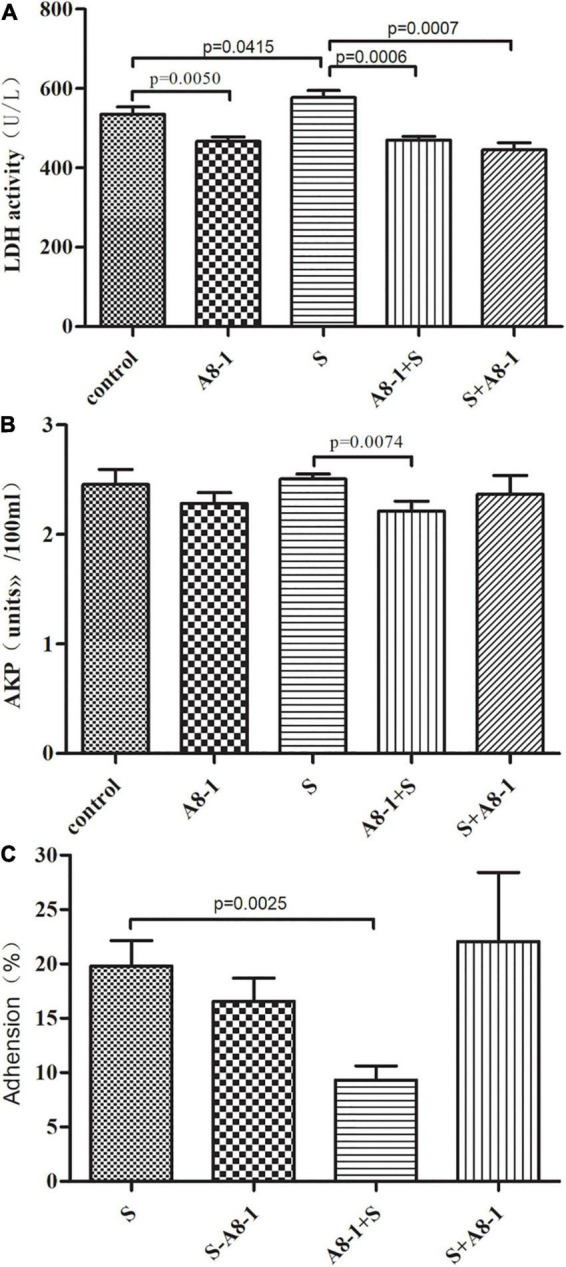

The enzyme activities of LDH and AKP in the supernatant of cell culture were selected as indicators for the integrity of the Caco-2 cell membrane (Figures 3A,B). Compared with the control group, it was found that the LDH activity in the A8-1 group was significantly reduced compared with the control group (467.20 vs. 535.58, P = 0.005) and was increased in the S. typhimurium ATCC14028 group (577.92 vs. 535.58, P = 0.042), whereas AKP activity was changed with a similar trend to LDH but no statistical difference. In the A8-1 + S group, activities of LDH and AKP in the Caco-2 cell supernatant were all significantly decreased compared with that of the Salmonella group (470.46 vs. 577.92, P < 0.001; 2.21 vs. 2.51, P = 0.007). Even in the S + A8-1 group, LDH activity was still significantly lower than that of the Salmonella group (445.61 vs. 577.92, P < 0.001). Those results show that strain A8-1 could protect the integrity of the Caco-2 cell membrane in pretreatment and inhibit the damage of Salmonella to Caco-2 cells.

FIGURE 3.

Protective effect of Enterococcus durans A8-1 to the Caco-2 cell membrane integrity by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (A) and AKP (B) activity assay and the adhesion rate of A8-1 to the Caco-2 cell (C).

A8-1 Competitively Inhibited the Adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to Caco-2 Cell

The plate counting method was used to explore the antagonism of A8-1 against the adhesion of S. typhimurium ATCC14028 to Caco-2 cells. It is found that, in S-A8-1 (competition group), A8-1 can reduce the adhesion of S. typhimurium to cells without statistical difference (19.8 vs. 16.5%, P > 0.05). In A8-1 + S (exclusion group), the adhesion of S. typhimurium to Caco-2 cells was significantly reduced (19.8 vs. 10.5%, P = 0.002) possibly because A8-1 could inhibit the growth of S. typhimurium and occupied the binding sites on the surface of the Caco-2 cells. However, there was no statistical difference for the adhesion to Caco-2 cells between S + A8-1 (replacement group) and the S. typhimurium group (19.8 vs. 22.1%, P = 0.592) (Figure 3C). Those results showed that A8-1 competitively inhibited the adhesion of S. typhimurium to Caco-2 cell.

A8-1 Reduced IL-8 and Increased IL-10, TNF-α Secretion in Response to LPS Stimulation in Caco-2 Cells

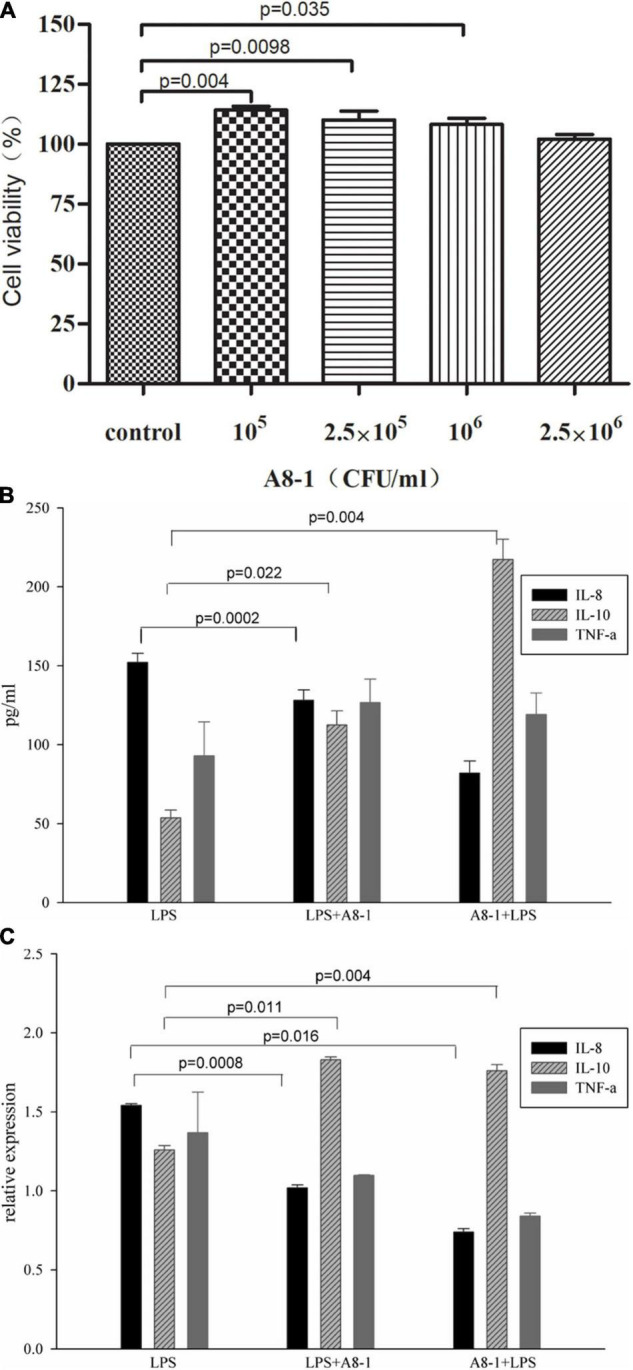

Results of cell viability treated by A8-1 are shown in Figure 4A. Different concentrations of A8-1 cells with 1 × 105, 2.5 × 105, and 1 × 106 CFU/mL could all significantly increase the Caco-2 cell viability (114.18 vs. 100%, P = 0.004; 110.04 vs. 100%, P = 0.0098; 108.14 vs. 100%, P = 0.035) except the 2.5 × 106 CFU/mL group (102.10 vs. 100%, P = 0.140). So 2.5 × 106 CFU/mL of A8-1 cells was selected for the following assays.

FIGURE 4.

The Caco-2 cell viability with incubation of 105, 2.5 × 105, 106, and 2.5 × 106CFU/mL of A8-1 (A). Then, 10 μg/mL LPS was added to the medium to induce the inflammation of Caco-2 cells, the anti-inflammation ability of 2.5 × 106CFU/mL A8-1 was detected by IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α through ELISA (B) and qPCR (C).

The 10 μg/mL LPS was added to the medium and induced the inflammation of Caco-2 cells, and the anti-inflammation ability of A8-1 was detected by IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α through ELISA and qPCR (Figures 4B,C). Compared with the LPS treatment cells, IL-8 were decreased in both A8-1 + LPS and LPS + A8-1 groups and showed significant difference between LPS + A8-1 and LPS groups (82.11 vs. 152.23 pg/mL, P = 0.002); the IL-10 were significantly increased in both A8-1 + LPS and LPS + A8-1 groups (217.3 vs. 53.7 pg/mL, P = 0.004; 112.5 vs. 53.7 pg/mL, P = 0.022). TNF-α increased in both intervention groups, but there was no significant difference compared with LPS group (126.7 vs. 93.0 pg/mL, P = 0.265; 119.1 vs. 93.0 pg/mL, P = 0.362). For the relative expression of mRNA, the IL-8 in A8-1 + LPS and LPS + A8-1 groups were significantly decreased (1.54 vs. 1.02, P = 0.0016; 1.54 vs. 0.74, P = 0.0008); IL-10 were significantly increased in both A8-1 + LPS and LPS + A8-1 groups (1.83 vs. 1.26, P = 0.004; 1.76 vs. 1.26, P = 0.011). TNF-α expression was decreased in both groups without statistical difference (1.36 vs. 1.09, P = 0.4059; 1.36 vs. 0.84, P = 0.1784). Those results showed that A8-1 could reduce the secretion of IL-8 and increase the secretion of IL-10 and TNF-α in response to LPS stimulation in Caco-2 cells.

Safety Evaluation of A8-1

Susceptibility of E. durans A8-1 to antibiotics was determined by measuring MICs, and the results were compared to the cutoff values for Enterococcus species as defined by EFSA and CLSI. E. durans A8-1 was found to be resistant only to clindamycin but was susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, high-level gentamicin (synergistic), high-level streptomycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, quinupristin/dalofopine, linezolid, vancomycin, tetracycline, tigecycline, and nitrofurantoin (Table 2). A8-1 showed no hemolytic activity (Supplementary Figure 1A) and no gelatin hydrolysis activity (Supplementary Figure 1B). It was identified as a weak biofilm producer (++). In the nine tested virulence related genes, there showed only asa1 gene positive in A8-1.

TABLE 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of Enterococcus durans A8-1 against 15 antimicrobials, and the antimicrobial susceptibility was evaluated by CLSI-2018 and FEEDAP-EFSA-2012.

| Antimicrobials | MIC | Cutoff values |

Antimicrobial susceptibility |

|

| CLSI | FEEDAP-EFSA | |||

| Penicillin | 2 | 8 | 4 | S |

| Ampicillin | ≤2 | 8 | 4 | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5 | 1 | 4 | S |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 2 | NA | S |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | NA | S |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | 4 | S |

| Clindamycin | ≥8 | 8 | 8 | R* |

| Quinupristin/dalofopine | 1 | 4 | NA | S |

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | NA | S |

| Vancomycin | ≤0.5 | 4 | 4 | S |

| Tetracycline | ≤1 | 4 | 2 | S |

| Tigecycline | ≤0.12 | 0.2 | NA | S |

| Nitrofurantoin | 32 | 64 | NA | S |

| high-level gentamicin (synergistic) | SYN-S | |||

| high-level streptomycin | SYN-S | |||

*For Enterococcus spp., clindamycin may appear active in vitro but is not effective clinically and should not be reported as susceptible as described in CLSI.

NA, Not available

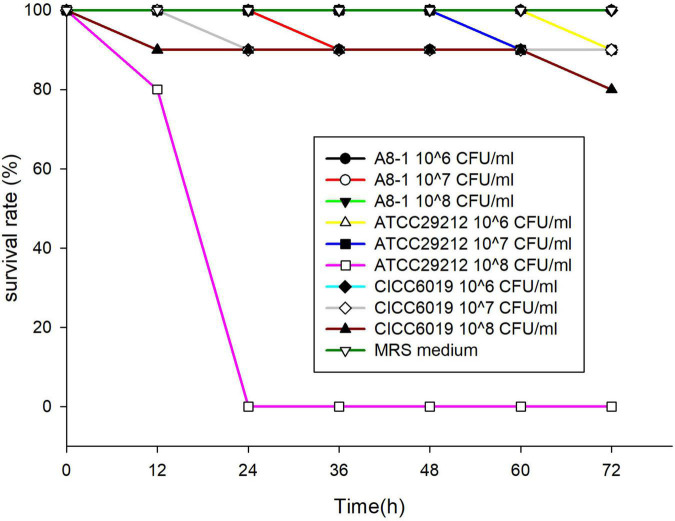

For the virulence assay with G. mellonella larvae, after 72 h injection, except the 108CFU/mL group of E. faecalis ATCC29212, all larvae had a 90% survival rate in both the 107 and 108CFU/mL groups. All larvae survived in the control and the 106CFU/mL groups. The survival curves were analyzed statistically using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, and there were no statistical differences in E. durans A8-1 and B. infantis CICC6096 within 107 and 108CFU/mL groups (P > 0.05). Apparently, A8-1 could be considered safe (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Survival curves of Galleria mellonella larvae were recorded for 72 h after injection with 10 μL of Enterococcus durans A8-1, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212, and Bifidobacterium infantis CICC6096 at concentrations of 1 × 106, 1 × 107, and 1 × 108 CFU/mL, respectively, and the 10 μL of MRS medium was used as negative controls.

Whole-Genome Sequence of A8-1

The circular chromosome of E. durans A8-1 contains 2,877,218 bp, 37.92% GC-content, and 56 tRNA genes (Table 3). Genome annotation at the RAST server showed that the C-1 genome encodes 2,752 proteins, and the corresponding functional categorization by COG annotation is in Supplementary Table 2. The sequence data of the E. durans A8-1 genome were deposited into NCBI and can be accessed via accession number PRJNA769572. The GO function annotation map of genome is shown in Supplementary Table 3. There were 1,123 genes related to biological process (BP), 590 genes related to cell composition (CC), and 757 genes related to molecular function (MF). Among the genes involved in BP, there were two bio-adhesion–related genes (A8-1_0276, Zinc-binding lipoprotein adcA; A8-1_2290, Metal ABC transporter substrate-binding lipoprotein), 85 cell colonization–related genes, 268 binding ability genes, and four antioxidant genes (A8-1_0078, Glutathione peroxidase; A8-1_2302, Manganese catalase; A8-1_2334, carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase; A8-1_2613, peroxiredoxin).

TABLE 3.

Genomic analysis of A8-1.

| Characteristic | Number | Characteristic | Number |

| Genome size (bp) | 2,877,218 | CRISPR | 2 |

| Scaffolds | 102 | tRNA | 56 |

| GC content (%) | 37.92 | Transposon PSI | 17 |

| Code genes | 2,752 | GIs | 15 |

The probiotic-related genes in the genome were also analyzed. The cholylglycine hydrolase (EC 3.5.1.24) gene responsible for bile salt hydrolysis action was identified in one copy within the A8-1 genome (A8-1_2053). Fibronectin/fibrinogen-binding protein (A8-1_2247) and collagen-binding protein (A8-1_0314) were found in the genome allowing them to bind the GI tract, suggesting an important role in adhesion and colonization in intestinal mucosal surfaces. Also, the resistance to hydrogen peroxide is imparted by genes alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahp, A8-1_2612, A8-1_2613) and NADH peroxidase (npr, A8-1_1888, A8-1_2186, and A8-1_2466) that were found in the genome. For the polysaccharide biosynthesis–related genes, there were eight genes located in the genome, including A8-1_ 0155 (polysaccharide biosynthesis glycosyltransferase), A8-1_0235 (polysaccharide core biosynthesis protein RfaS), A8-1_0854 (polysaccharide transport system ATP-binding protein), A8-1_1612 (sugar transferase), A8-1_1617 (polysaccharide cholinephosphotransferase), A8-1_1621 (polysaccharide core biosynthesis protein RfaS), A8-1_1639 (polysaccharide chain length determining protein CapA), and A8-1_1764 (polysaccharide biosynthesis protein). In addition, based on the previous studies, we also screened for a set of genes involved in imparting important probiotic functions as described in Table 3.

The drug-resistance and virulence genes were annotated by database of CARD and VFDB. Two aminoglycoside resistance–related genes AAC (6′)-IIH and AAC (6′)-IID; three β-lactam resistance genes mecC, mecB, and mecA; and one fluoroquinolone resistance gene mfd were predicted in CARD. Regarding the possibility of acquired resistance by horizontal gene transfer (HGT), there was no detection of any acquired antibiotic resistance genes. In addition, efaA/scbA was found in virulence gene prediction (A8-1_2290, endocarditis specific antigen); however, the similarity score was only 50.1%. Meanwhile, the asa1 gene detected by PCR was not found in the genome sequencing results, which may explain the non-toxic activity to the G. mellonella larvae. In addition to the above genes, there predicated some genes responsible for the secondary metabolites, such as bsh (A8-1_2053, bile salt hydrolase), which may be related to the bile salt tolerance and survival in the intestinal tract for A8-1; cap8E (A8-1_1630, capsular polysaccharide synthesis enzyme), cap8E (A8-1_1631, capsular polysaccharide synthesis enzyme), cas4J (A8-1_1631, capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein) genes related to capsular polysaccharide synthesis were also found in the genome, which may contribute to protect bacteria itself and resist the phagocytosis of host cells; fliN (A8-1_1957, flagella motor switch protein), which is involved in synthesis of flagellin, which could be recognized by Toll like receptor TLR5, and activate innate immunity, upregulate the expression of tight junction protein Occludin and mucin and protect the intestinal barrier.

Discussion

Probiotics, the microorganisms referred to are non-pathogenic bacteria and are considered “friendly germs” due to the benefits they offer to the gastrointestinal tract and immune system. Probiotic Enterococcus spp. are mainly from the gut of human and animal and can be detected in fecal samples, which are more competitive than isolates from other environments and deserve more attention for probiotic screening (Rodríguez et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015). Except the origin host, in the screening for new probiotic strains, probiotic characteristics of the isolates should be analyzed, including stress tolerance, adhesion, antibacterial ability, anti-inflammatory ability, antibiotic resistance, and toxicity (AlKalbani et al., 2019). Our study aimed to assess the potential probiotic properties and safety of an E. durans strain A8-1 isolated from feces of a healthy Chinese infant.

In our results, A8-1 grew faster and showed higher antistress ability. By simulating the gastrointestinal environment, it was found that, under the aerobic conditions of pH 5.0, 3% bile salt, and 7% NaCl, the growth of E. durans A8-1 could reach more than 50% of the control group, and this indicated that A8-1 has the potential to pass through the intestinal contents and reach the intestinal colonization site. Bile salt tolerance has generally been considered more important during probiotic selection than that of other properties, such as gastric and pancreatic tolerance (Masco et al., 2007). The growth of the strain was stimulated under bile salt and NaCl, which suggested that we can optimize the fermentation conditions to promote better growth and faster enrichment of bacteria cells. In the genome of A8-1, the bile salt hydrolase–related gene bsh was found, and the presence of bile salt hydrolase in probiotics renders them more tolerant to bile salts (Hussein et al., 2020), which may interpret the better tolerance of A8-1 to higher concentration of bile salt.

The first step for good probiotics to exert probiotics in the host is to adhere to the cell surface, which is also the basis for probiotics to show the barrier protection function. Also, for probiotic enterococci, it is an important factor in colonization and competitive exclusion of enteropathogens (Nueno-Palop and Narbad, 2011). The stronger the adhesion ability of the bacteria, the higher the probability of colonization and survival in the intestinal tract. Compared with L. rhamnosus BL379, A8-1 had higher adhesion ability to the tested proteins of mucin, BSA, and collagen. The human intestinal epithelial-like Caco-2 cell line is often used as an intestinal epithelial cell model (Jose et al., 2017). The adhesion rate of A8-1 to Caco-2 cells was 30%, and this result showed that the adhesion performance of the A8-1 to various proteins and cells was different. Also, the considerably high level of hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, and co-aggregation of A8-1 could enable the bacterial cell to adhere to host epithelial cells and allow the formation of a barrier to prevent the colonization of pathogens on surfaces of the mucosa (Nami et al., 2020; Fonseca et al., 2021). Similarly, whether the strain has the same adhesion ability in vivo and in vitro also needs to be considered (Banwo et al., 2013). Metabolites produced by probiotics have antibacterial activities, such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocin (İspirli et al., 2015). A8-1 has a better antibacterial effect on G– than G+, which may be related to the similar bacterial structure of A8-1 (G+) and two G + indicator bacteria (E. faecalis ATCC 29212 and S. aureus ATCC 5923). Moreover, bacteriocin showed a narrow antibacterial spectrum against the same related strains. In this study, the growth of the indicator bacteria was used to determine the antibacterial ability of Enterococcus isolates, but the specific types and production of antibacterial active substances were not discussed. To further analyze the bacteriostatic mechanism of A8-1, the eight specific polysaccharide biosynthesis–related genes, which were annotated in the genome sequence of A8-1, deserve more attention.

Lipopolysaccharide is often used as a substance to induce an inflammatory reaction, which can make cells produce inflammation and stimulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines (Drakes et al., 2004). Our results show that the inflammatory response induced by LPS could be alleviated and IL-8 mRNA could be reduced after being pretreated with A8-1. The expression of TNF-α mRNA was decreased, but there was no significant change in the supernatant of each treatment group (P > 0.05). A8-1 may have the potential to inhibit inflammatory response. When inflammation occurs, A8-1 can reduce the expression of cytoinflammatory factors to reduce the inflammatory response of cells to LPS. It is worth noting that probiotics have highly diverse effects on the level of immune regulatory cytokines, mainly related to the specificity of strains and cell lines (Kook et al., 2019).

Enterococcus, as the original symbiotic bacteria in the intestine, has dual characteristics of probiotic function and potential pathogenicity. Therefore, it is necessary to compare and analyze the functional characteristics and safety at the strain level (Klimko et al., 2020). To evaluate the safety of A8-1, susceptibility to antibiotics, hemolytic activity, gelatin hydrolysis activity, virulence-related genes, and the virulence assay were all carried out. In the antibiotic susceptibility test, A8-1 was only resistant to clindamycin, which may be related to the inherent resistance of enterococci, which was verified in E. durans KLDS 6.0930 (Li et al., 2018). Antibiotics linezolid and vancomycin are often used as the last resort for G+ pathogen infection. β-lactams (penicillin, ampicillin), and aminoglycoside antibiotics are generally the preferred drugs for the treatment of enterococci infection, which may make the strains more resistant to such antibiotics (Tsai et al., 2012). A8-1 was sensitive to the above antibiotics. Bacterial toxicity should be evaluated by phenotype and genotype. The esp gene may be involved in the formation of biofilm, but it is not the only factor determining the producing of biofilm (Fallah et al., 2017; Kook et al., 2019). No esp gene was detected in A8-1. The ability of producing biofilm was considerate lower, which may be related to the lack of esp gene. A8-1 was gleE gene negative with no gelatin hydrolase (Popović et al., 2018). Furthermore, there were no obvious pathogenicity or virulence genes found in A8-1. This correlates with the observed phenotype in the G. mellonella model due to the low mortality rates that were obtained, which is similar behavior to the larvae inoculated with L. lactis strains reported by Martino (Martino et al., 2018).

The whole-genome sequencing of bacteria is a convenient way to determine antibiotic-resistant genotypes and predict the corresponding resistance phenotypes, and the phenotype does not always completely reflect the genotype. Through comparative analysis of ARDB, it predicted aminoglycosides, β-lactam antibiotics, and fluoroquinolone-related genes in A8-1, but A8-1 had no corresponding resistance phenotype. It may be because the expression of the drug-resistant gene was silenced or the transcription process was not completed, resulting in the absence of resistance phenotype. A8-1 is resistant to clindamycin, which is usually an inherent antibiotic resistant to Enterococcus, and the predicted lasA, lmrB, lmrC, and lmrD genes contributed to the clindamycin-resistance through the efflux pump function (Hollenbeck and Rice, 2012). However, antibiotic resistance may have a positive effect on probiotics. For some antibiotic-resistant enterococci, it can effectively maintain the natural balance of intestinal flora in the process treatment (Strompfová et al., 2004).

In the current research, we only explored the impact of potential probiotic A8-1 on intestinal epithelial cell membranes and the regulation of cell inflammation. In the follow-up experiments, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) should be measured, and the cell tight junction protein can be further detected to explain the effect of A8-1 on the maintenance of gut permeability and intestinal barrier function and interpret the mechanism of inflammation suppression through the inflammatory response-related signal pathways. Furthermore, animal models will be established to evaluate the safety and functionality of E. durans A8-1 before potential use in applications.

Conclusion

In summary, we have identified a strain of E. durans that is able to tolerate and survive the simulated gastric and intestinal juices and has the potential to colonize the intestinal epithelial cells. Furthermore, we also showed that it contains no obvious pathogenicity or virulence genes. Taken together, our findings suggest the efficacy of probiotic E. durans A8-1 in exerting an adherence to the cell surface to show the barrier protection function and competitive exclusion of enteropathogens with reductions in the levels of inflammatory cytokines. According to the results of these evaluated attributes, E. durans strain A8-1 could be a promising probiotic candidate for applications.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

BH and YC: conceptualization and writing—review and editing. YZ, JW, and LS: main experiments. LL and JY: genome analysis. RD: data and bacterial curation. BH and YZ: writing—original draft preparation. BH: supervision. BH and RD: funding acquisition. All authors agreed to be accountable for the content of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81673199 and 82173526) and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province, China (No. 2019JM-445).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.799173/full#supplementary-material

References

- AlKalbani N. S., Turner M. S., Ayyash M. M. (2019). Isolation, identification, and potential probiotic characterization of isolated lactic acid bacteria and in vitro investigation of the cytotoxicity, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activities in fermented sausage. Microb. Cell Fact. 18:188. 10.1186/s12934-019-1239-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banwo K., Sanni A., Tan H. (2013). Technological properties and probiotic potential of Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from cow milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114 229–241. 10.1111/jam.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carasi P., Racedo S. M., Jacquot C., Elie A. M., Serradell M. L., Urdaci M. C. (2017). Enterococcus durans EP1 a promising anti-inflammatory probiotic able to stimulate sIgA and to increase Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abundance. Front. Immunol. 8:88. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zheng D., Liu B., Yang J., Jin Q. (2016). VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis–10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D694–D697. 10.1093/nar/gkv1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrincione S., Neumann B., Zühlke D., Riedel K., Pessione E. (2019). Detailed soluble proteome analyses of a sairy-isolated Enterococcus faecalis: a possible approach to assess food safety and potential probiotic value. Front. Nutr. 6:71. 10.3389/fnut.2019.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2018). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 27th Informational Supplement. M100-S28. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S., Voldby Larsen M., Møller Aarestrup F., Lund O. (2013). PathogenFinder–distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One 8:e77302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakes M., Blanchard T., Czinn S. (2004). Bacterial probiotic modulation of dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 72 3299–3309. 10.1128/iai.72.6.3299-3309.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed [FEEDAP] (2012). Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 10:2740. 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2740 29606757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah F., Yousefi M., Pourmand M. R., Hashemi A., Nazari Alam A., Afshar D. (2017). Phenotypic and genotypic study of biofilm formation in Enterococci isolated from urinary tract infections. Microb. Pathog. 108 85–90. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca H. C., de Sousa M. D., Ramos C. L., Dias D. R., Schwan R. F. (2021). Probiotic properties of Lactobacilli and their ability to inhibit theadhesion of enteropathogenic bacteria to Caco-2 and HT-29 cells. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 13 102–112. 10.1007/s12602-020-09659-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cayuela T., Korany A. M., Bustos I., Cadiñanos L. P. G. D., Requena T., Peláez C., et al. (2014). Adhesion abilities of dairy Lactobacillus plantarum strains showing an aggregation phenotype. Food Res. Intern. 57 44–50. 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. (2007). CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 W52–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkm360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R. X., Yang Z. Q., Li Z. H., Chen S. L., Luo Z. L. (2008). Probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from stool samples of longevous people in regions of Hotan, Xinjiang and Bama, Guangxi, China. Anaerobe 14 313–317. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbeck B. L., Rice L. B. (2012). Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in enterococcus. Virulence 3, 421–433. 10.4161/viru.21282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein W. E., Abdelhamid A. G., Rocha-Mendoza D., García-Cano I., Yousef A. E. (2020). Assessment of safety and probiotic traits of Enterococcus durans OSY-EGY, isolated from Egyptian artisanal cheese, using comparative genomics and phenotypic analyses. Front. Microbiol. 11:608314. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.608314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- İspirli H., Demirbaş F., Dertli E. (2015). Characterization of functional properties of Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from human gut. Can. J. Microbiol. 61 861–870. 10.1139/cjm-2015-0446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose N. M., Bunt C. R., McDowell A., Chiu J. Z. S., Hussain M. A. (2017). Short communication: a study of Lactobacillus isolates’ adherence to and influence on membrane integrity of human Caco-2 cells. J. Dairy Sci. 100 7891–7896. 10.3168/jds.2017-12912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimko A. I., Cherdyntseva T. A., Brioukhanov A. L., Netrusov A. I. (2020). In vitro evaluation of probiotic potential of selected lactic acid bacteria strains. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 12 1139–1148. 10.1007/s12602-019-09599-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook S. Y., Chung E. C., Lee Y., Lee D. W., Kim S. (2019). Isolation and characterization of five novel probiotic strains from Korean infant and children faeces. PLoS One 14:e0223913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouhi F., Mirzaei H., Nami Y., Khandaghi J., Javadi A. (2021). Potential probiotic and safety characterisation of Enterococcus bacteria isolated from indigenous fermented Motal cheese. Int. Dairy J. 126:105247. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2021.105247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Zhan M., Evivie S. E., Jin D., Zhao L., Chowdhury S., et al. (2018). Evaluating the safety of potential probiotic Enterococcus durans KLDS6.0930 using whole genome sequencing and oral toxicity study. Front. Microbiol. 9:1943. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang Y., Cui H., Li Y., Sun Y., Qiu H. J. (2020). Characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of a wild boar as potential probiotics. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:49. 10.3389/fvets.2020.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Yu C., Li Y., Lam T. W., Yiu S. M., Kristiansen K., et al. (2009). SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25 1966–1967. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Da R., Cheng Y., Tuo X., Wei J., Jiang K., et al. (2020). Mechanism of antibacterial activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens C-1 lipopeptide toward anaerobic Clostridium difficile. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020:3104613. 10.1155/2020/3104613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour N. M., Heine H., Abdou S. M., Shenana M. E., Zakaria M. K., El-Diwany A. (2014). Isolation of Enterococcus faecium NM113, Enterococcus faecium NM213 and Lactobacillus casei NM512 as novel probiotics with immunomodulatory properties. Microbiol. Immunol. 58 559–569. 10.1111/1348-0421.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino G. P., Espariz M., Gallina Nizo G., Esteban L., Blancato V. S., Magni C. (2018). Safety assessment and functional properties of four Enterococci strains isolated from regional Argentinean cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 277 1–9. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masco L., Crockaert C., Van Hoorde K., Swings J., Huys G. (2007). In vitro assessment of the gastrointestinal transit tolerance of taxonomic reference strains from human origin and probiotic product isolates of Bifidobacterium. J. Dairy Sci. 90, 3572–3578. 10.3168/jds.2006-548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maturana P., Martinez M., Noguera M. E., Santos N. C., Disalvo E. A., Semorile L., et al. (2017). Lipid selectivity in novel antimicrobial peptides: implication on antimicrobial and hemolytic activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerf. 153 152–159. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur A. G., Waglechner N., Nizam F., Yan A., Azad M. A., Baylay A. J., et al. (2013). The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 3348–3357. 10.1128/aac.00419-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Provencio D., Llopis M., Antolín M., de Torres I., Guarner F., Pérez-Martínez G., et al. (2009). Adhesion properties of Lactobacillus casei strains to resected intestinal fragments and components of the extracellular matrix. Arch. Microbiol. 191 153–161. 10.1007/s00203-008-0436-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nami Y., Abdullah N., Haghshenas B., Radiah D., Rosli R., Yari Khosroushahi A. (2014). A newly isolated probiotic Enterococcus faecalis strain from vagina microbiota enhances apoptosis of human cancer cells. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117 498–508. 10.1111/jam.12531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nami Y., Panahi B., Jalaly H. M., Bakhshayesh R. V., Hejazi M. A. (2020). Application of unsupervised clustering algorithm and heat-map analysis for selection of lactic acid bacteria isolated from dairy samples based on desired probiotic properties. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 118:108839. 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nueno-Palop C., Narbad A. (2011). Probiotic assessment of Enterococcus faecalis CP58 isolated from human gut. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 145 390–394. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll T., Crank C. W. (2015). Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and optimal management. Infect. Drug Resist. 8 217–230. 10.2147/idr.S54125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popović N., Dinič M., Tolinaèki M., Mihajlović S., Terzić-Vidojević A., Bojić S., et al. (2018). New insight into biofilm formation ability, the presence of virulence genes and probiotic potential of Enterococcus sp. dairy isolates. Front. Microbiol. 9:78. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popović N., Djokić J., Brdarić E., Dinić M., Terzić-Vidojević A., Golić N., et al. (2019). The influence of heat-killed Enterococcus faecium BGPAS1-3 on the tight junction protein expression and immune function in differentiated Caco-2 cells infected with Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19111. Front. Microbiol. 10:412. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez J. M., Murphy K., Stanton C., Ross R. P., Kober O. I., Juge N., et al. (2015). The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 26:26050. 10.3402/mehd.v26.26050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpellini E., Campanale M., Leone D., Purchiaroni F., Vitale G., Lauritano E. C., et al. (2010). Gut microbiota and obesity. Intern. Emerg. Med. 5 (Suppl. 1) S53–S56. 10.1007/s11739-010-0450-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke I. C., Zentek J., Vahjen W. (2015). Effects of the probiotic Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 on selected lactic acid bacteria and enterobacteria in co-culture. Benef. Microb. 6 345–352. 10.3920/bm2014.0052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strompfová V., Lauková A., Ouwehand A. C. (2004). Selection of Enterococci for potential canine probiotic additives. Vet. Microbiol. 100 107–114. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. Y., Liao C. H., Chen Y. H., Lu P. L., Huang C. H., Lu C. T., et al. (2012). Trends in susceptibility of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium to tigecycline, daptomycin, and linezolid and molecular epidemiology of the isolates: results from the Tigecycline In vitro surveillance in Taiwan (TIST) study, 2006 to 2010. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 3402–3405. 10.1128/aac.00533-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Da R., Tuo X., Cheng Y., Wei J., Jiang K., et al. (2020). Probiotic and safety properties screening of Enterococcus faecalis from healthy Chinese infants. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 12 1115–1125. 10.1007/s12602-019-09625-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. X., Li T., Ning Y. Z., Shao D. H., Liu J., Wang S. Q., et al. (2015). Molecular characterization of resistance, virulence and clonality in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis: a hospital-based study in Beijing, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 33 253–260. 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Jiang M., Wan C., Chen X., Chen X., Tao X., et al. (2016). Screening probiotic strains for safety: evaluation of virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Enterococci from healthy Chinese infants. J. Dairy Sci. 99 4282–4290. 10.3168/jds.2015-10690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., Zhang Y., Lu H. M., Li D. T., Zhang Z. L., Tang Z. X., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial activity and safety evaluation of Enterococcus faecium KQ 2.6 isolated from peacock feces. BMC Biotechnol. 15:30. 10.1186/s12896-015-0151-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.