Abstract

Background

Multinodular goitre is common in women. Treatments for non‐toxic multinodular goitre include surgery, levothyroxine suppressive therapy, and radioiodine. Radioiodine therapy is the only non‐surgical alternative for non‐toxic multinodular goitre. However, a high amount of radioiodine is needed to enable the thyroid nodules to adequately take up the radioiodine, because the multinodular goitre takes up a low amount of iodine. Recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH) has been used to increase radioiodine uptake and reduce thyroid volume of the multinodular goitre. Whether the improved reduction of the goitre resulting from rhTSH‐stimulated radioiodine therapy is beneficial to the person remains controversial.

Objectives

To assess the effects of recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre.

Search methods

We searched the CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Scopus as well as ICTRP Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. The date of the last search of all databases was 18 December 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) comparing the effects of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment compared with radioiodine alone for non‐toxic multinodular goitre, with at least 12 months of follow‐up.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance. Screening for inclusion, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were carried out by one review author and checked by a second. Our main outcomes were health‐related quality of life (QoL), hypothyroidism, adverse events, thyroid volume, all‐cause mortality, and costs. We used a random‐effects model to perform meta‐analyses, and calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes, using 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for effect estimates. We evaluated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included six RCTs. A total of 197 participants were allocated to rhTSh‐aided radioiodine therapy, and 124 participants were allocated to radioiodine. A single dose of radioiodine was administered 24 hours after the intramuscular injection of a single dose of rhTSH. The duration of follow‐up ranged between 12 and 36 months.

Low‐certainty evidence from one study, with 85 participants, showed uncertain effects for QoL for either intervention. RhTSH‐aided radioiodine increased hypothyroidism compared with radioiodine alone (64/197 participants (32.5%) in the rhTSH‐aided radioiodine group versus 15/124 participants (12.1%) in the radioiodine alone group; RR 2.53, 95% CI 1.52 to 4.20; 6 studies, 321 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence in favour of radioiodine alone). A total of 118/197 participants (59.9%) in the rhTSH‐aided radioiodine group compared with 60/124 participants (48.4%) in the radioiodine alone group experienced adverse events (random‐effects RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.63; 6 studies, 321 participants; fixed‐effect RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.49 in favour of radioiodine only; low‐certainty evidence).

RhTSH‐aided radioiodine reduced thyroid volume with a MD of 11.9% (95% CI 4.4 to 19.4; 6 studies, 268 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). One study with 28 participants reported one death in the radioiodine alone group (very‐low certainty evidence). No study reported on costs.

Authors' conclusions

RhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre, compared to radioiodine alone, probably increased the risk of hypothyroidism but probably led to a greater reduction in thyroid volume. Data on QoL and costs were sparse or missing.

Plain language summary

Recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Background

Goitre is an enlargement of the thyroid gland that can be classified as simple, diffuse goitre or multinodular goitre. Nodules (lumps) within the thyroid gland are common and usually benign. They are more frequent in women, the elderly, and in people who live in iodine‐deficient areas. Thyroid nodules may occur as a single nodule or as multiple nodules (multinodular). Multinodular goitre can be 'toxic' (producing too much thyroid hormone), or non‐toxic (normal thyroid function). Treatments for non‐toxic multinodular goitre include surgery, thyroid hormone suppressive therapy, and radioiodine therapy. Usually, higher amounts of radioiodine are needed to enable an appropriate radioiodine uptake in the thyroid nodules. Genetically engineered recombinant human thyroid‐stimulating hormone (rhTSH) has been used to increase radioiodine uptake.

We wanted to find out whether rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment is better for people with non‐toxic multinodular goitre compared with radioiodine treatment alone. The outcomes we were specifically interested in were health‐related quality of life, underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism), side effects, reduction in thyroid volume, death from any cause, and costs.

What did we look for?

We searched medical databases for studies that: — were randomised controlled trials (medical studies where participants are put randomly into one of the treatment groups); — included people with non‐toxic multinodular goitre; — compared rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment with radioiodine treatment alone; — tracked participants (follow‐up) for at least one year.

What did we find?

We found six studies that included a total of 321 participants. A single dose of radioiodine was administered 24 hours after the intramuscular injection of a single dose of rhTSH. Participants were followed up for 12 to 36 months.

Key results

One study with 85 participants showed there was not a clear beneficial or harmful effect on health‐related quality of life for either intervention. Fewer people (53 to 377 of 1000 treated) receiving radioiodine alone experienced hypothyroidism compared with rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy. It is possible that radioiodine alone resulted in fewer side effects, like discomfort and neck pain, than rhTSH‐aided radioiodine, but we need more studies to confirm this finding. On the other hand, rhTSH‐aided radioiodine reduced thyroid volume by, on average, 12% more than radioiodine treatment alone. One study, with 28 participants, reported one death in the radioiodine alone group. No study reported on costs.

Certainty of the evidence

We are moderately confident about the results for hypothyroidism and reduction of thyroid volume, mainly because there were only six studies with 268 to 321 participants. We are very uncertain about the results for health‐related quality of life and death from any cause, because there was just one study, with 85 participants that reported these outcomes. We are uncertain about the results for adverse events, mainly because there were not enough studies or participants to reliably evaluate this outcome.

How up to date is this review? This evidence is up to date to 18 December 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine compared with radioiodine for non‐toxic multinodular goitre.

| Recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine compared with radioiodine for non‐toxic multinodular goitre | ||||||

|

Patient: people with non‐toxic multinodular goitre Settings: outpatients (5 studies); in hospital (1 study) Intervention: recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH)‐aided radioiodine Comparison: radioiodine only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with radioiodine only | Risk with rhTSH aided radioiodine | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Health‐related quality of life Assessed with thyroid disease‐specific questionnaire ThyPRO Follow‐up: 36 months |

See comment | 85 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

There were no clear differences in symptom improvement in the 17 goitre‐specific questions and overall quality of life question among the treatment groups at 6 and 36 months | ||

|

Hypothyroidism Follow‐up: 12 to 36 months |

131 per 1000 | 306 per 1000 (184 to 508) | RR 2.53 (1.52 to 4.20) | 321 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | |

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 to 36 months |

484 per 1000 | 600 per 1000 (455 to 789) | RR 1.24 (0.94 to 1.63) | 321 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc | The fixed‐effect model showed a RR of 1.23, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.49 in favour of radioiodine only |

|

Thyroid volume Follow‐up: 12 to 36 months |

The mean reduction in thyroid volume ranged across control groups from 12.7% to 46.1% | The mean reduction in thyroid volume in the intervention groups was 11.9% higher (4.4% higher to 19.4% higher) | — | 268 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | |

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 24 months |

See comment | 28 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd | Only 1 study reported deaths: 1/10 participants in the radioiodine only group died compared with 0/18 participants in the rhTSH aided radioiodine group | ||

| Costs | Not reported | |||||

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; rhTSH: recombinant human thyrotropin ; RR: risk ratio; ThyPRO: thyroid‐related patient‐reported outcomes. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by three levels because of very serious imprecision (low median sample size, only 1 study reporting outcome) bDowngraded by one level because of imprecision (low median sample size) cDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (low median sample size, CI consistent with benefit and harm) dDowngraded by three levels because of very serious imprecision (one study only with small number of participants, very low number of events)

Background

Description of the condition

Multinodular goitre

Goitre is an enlargement of the thyroid gland that can be classified as simple diffuse goitre, or multinodular goitre. Multinodular goitre is a clinically recognisable enlargement of the thyroid gland, characterised by excessive growth of more than one nodule (Medeiros‐Neto 2012). Multinodular goitre can be divided into toxic (hyperthyroid), and non‐toxic (euthyroid) multinodular goitre based on the thyroid function.

Epidemiology and pathogenesis of non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Multinodular goitre is more common in women, with a female to male ratio of 4.5 to 1. The incidence of multinodular goitre in an adult UK population was about 15.5% (Tunbridge 1977). In the US Framingham study, where iodine intake was high (urinary iodine 246 mg/L), investigators detected multinodular goitre by palpation in only 1% of the examined adults (Vander 1954).

The major cause for multinodular goitre is iodine deficiency, and the incidence of multinodular goitre is increased in individuals with a history of chronic iodine deficiency (Medeiros‐Neto 2012). It is estimated that about 6% of elderly people in a given population, previously suspected to have iodine deficiency, may have visible multinodular goitre (Berghout 1990). Other risk factors may relate to smoking (Laurberg 2004), natural goitrogens (e.g. cassava, millet, babassu coconut, vegetables from the genus Brassica, and soybean (Doerge 2002; Schröder‐van der Elst 2003)), autoimmune disorders (e.g. Grave's disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis (Pedersen 2001)), certain iodine‐rich drugs (e.g. amiodarone (Vagenakis 1975)), and environmental agents (e.g. environmental chemicals, coal‐derived pollutants, perchlorate (Braverman 2007; Lindsay 1992)). People with multinodular goitre often have a family history of goitre and surgical removal of nodules (Bayer 2004).

Clinical manifestations of non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Most people with non‐toxic multinodular goitre have few or no symptoms, except for those with large goitre. Many people are referred to hospital for cosmetic reasons or airway compression symptoms. Compression symptoms are more often seen in people with intrathoracic extensions of the multinodular goitre. Airway compression results in dyspnoea, stridor, cough, and a sensation of shock (Medeiros‐Neto 2012). A few people may have a sudden transient pain, with enlargement of a side of the multinodular goitre, secondary to haemorrhage.

Diagnosis of non‐toxic multinodular goitre

In people with large goitre, determination of thyroid hormones and imaging techniques are useful to establish the non‐toxic nature of the multinodular goitre. The thyroid hormones free thyroxine (f)T4)), free triiodothyronine (f)T3)), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and antithyroid peroxidase (anti‐TPO) antibodies are frequently measured during the initial evaluation. Neck palpation is imprecise for both the assessment of thyroid morphology, and size (weight) determination (Medeiros‐Neto 2012). Sonography provides an accurate estimate of the goitre and nodule volume, identifies thyroid nodules and cysts, detects microcalcification, and specifies the degree of echogenicity of the nodule. Diagnosis of non‐toxic multinodular goitre is established by clinical signs, normal TSH (euthyroid state), and more than one nodule by sonography. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful for assessing a multinodular goitre that extends to the upper mediastinum, and to evaluate the degree of tracheal compression.

Description of the intervention

Treatments for non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Treatments for non‐toxic multinodular goitre include surgery, levothyroxine suppression therapy, and radioiodine. Surgery efficiently reduces the goitre size, but carries a risk of both surgical and anaesthetic complications. Small multinodular goitres were preferentially treated with levothyroxine suppression therapy. However, levothyroxine suppression therapy seems to be on the wane, due to its low efficacy and adverse effects (Diehl 2005). This leaves radioiodine therapy as the only non‐surgical alternative. Treatments vary in different countries. In the United States, surgery is the preferred treatment for people with large multinodular goitres (Bonnema 2000; Bonnema 2002). Radioiodine treatment of non‐toxic multinodular goitre was introduced in some European countries about 25 years ago, and thyroidologists in Europe have tended to treat multinodular goitre with radioiodine as an alternative to surgery (Bonnema 2009; Hegedüs 1988).

Radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Radioactive iodine (131I) is a β‐γ emitting radionuclide with a physical half‐life of 8.1 days, a principal γ−ray of 364 KeV, a principal β‐particle with a maximum energy of 0.61 MeV, an average energy of 0.192 MeV, and a range in tissue of 0.8 mm. Radioiodine is a good choice for those who decline, or are not fit for surgery. Fine‐needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) should be performed in multinodular goitres, to rule out thyroid malignancy before radioiodine therapy. If a nodule within a multinodular goitre has a cytologic diagnosis of papillary cancer, surgery should be performed. Radioiodine therapy for non‐toxic multinodular goitre results in a mean thyroid volume reduction of approximately 40% to 50%, one year after treatment (Huysmans 2000; Le Moli 1999; Nygaard 1993; Wesche 2001). However, the individual response to radioiodine is variable, mostly because of low iodine uptake by the multinodular goitre. For large multinodular goitres, a high radioiodine dose is needed to achieve an adequate radioiodine accumulation in the thyroid nodules. Therefore, large activities of radioiodine are usually required. For this reason, people treated with radioiodine are often subject to hospitalisation, greater exposure to radiation, and higher treatment costs.

Recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre

Recombinant TSH is produced by recombinant DNA technology, which is a laboratory method to bring together genetic material from multiple sources. Thyroglobulin levels and radioiodine imaging stimulated by rhTSH were initially used in the diagnosis of metastatic disease of differentiated thyroid cancer, instead of thyroid hormone withdrawal. Later, it was found that rhTSH‐aided iodine‐131 thyroid remnant ablation, which is as effective as thyroid hormone withdrawal for people with differentiated thyroid cancer after surgery (Ma 2010). It was suggested that rhTSH might be used to increase radioiodine uptake in the various nodules of the multinodular goitre. RhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy for multinodular goitre improves goitre volume reduction, reduces compression, and eliminates areas of thyroid autonomy (Ceccarelli 2010). It is easier to perform in an outpatient setting, with reduced costs to the public health system, particularly in countries with limited resources and a lack of high‐volume thyroid surgeons.

Adverse effects of the intervention

Acute adverse effects include local tenderness, airway compression, and cardiac symptoms (rapid heart beat), which is caused by the surge of thyroid hormones in the blood, and an increase in the goitre volume (in the first 48 hours of radioiodine therapy). Glucocorticoids and β‐blockers are used to minimise these acute adverse effects (Fast 2009). A number of studies suggested that these adverse effects are probably dose‐dependent, and are negligible with lower rhTSH doses (Ceccarelli 2010; Ceccarelli 2011; Cubas 2009; Fast 2010; Fast 2011) .

The most common long‐term adverse effect of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy for non‐toxic multinodular goitre is permanent hypothyroidism (one third of people). In three reported randomised controlled studies, permanent hypothyroidism at one year was reported in 21%, 63%, and 65% of rhTSH‐treated participants (Bonnema 2007; Hegedüs 1988; Silva 2004).

How the intervention might work

Radioactive iodine uptake by thyroid cells is mediated by a glycoprotein located on the cell membrane: the sodium/iodine (Na+/I‐)symporter (NIS). NIS expression, as well as thyroglobulin production, is TSH‐dependent. RhTSH is a heterodimeric glycoprotein, produced by recombinant DNA technology. It is obtained following transfection of a microorganism with genes encoding human TSH α and β subunits; rhTSH is then purified. The amino acid sequence of rhTSH is identical to that of human pituitary TSH, and shares its biochemical properties. It has been shown to stimulate thyroglobulin production and thyroid cell proliferation, as well as radioactive iodine uptake by thyroid cells.

RhTSH not only increases radioiodine uptake (Huysmans 2000; Nieuwlaat 2001), but also leads to a more homogeneous distribution of radioiodine in the gland, and to the thyroid cell activation that makes them more radiosensitive (Ceccarelli 2010). These properties may reduce the radioiodine activity required for the treatment of non‐toxic multinodular goitre. RhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy for non‐toxic multinodular goitre reduces goitre size by 35% to 55%, compared with radioiodine alone. RhTSH might be particularly useful in people with very large goitres, and in those with a low baseline thyroid radioiodine uptake.

Why it is important to do this review

Narrative reviews about rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre suggested that radioiodine therapy was effective for large non‐toxic goitre in elderly people. Authors also stated that radioiodine therapy for multinodular goitres should be used in people with comorbidities or high operative risk, and in people with special professions (singers, teachers, speakers), or those who wish a non‐invasive treatment modality (Dietlein 2006). Another review reported that rhTSH‐stimulated radioiodine therapy of benign non‐toxic multinodular goitre is significantly more effective than radioiodine alone, but is still an off‐label use (Bonnema 2009).

Recombinant TSH can augment the reduction of a nodular goitre size after radioiodine therapy. However, hypothyroidism is a common complication, and acute airway compression may be a life‐threatening complication. Whether the benefits outweigh the risks is controversial. Therefore, we will evaluate the effects of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment to help people make informed decisions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Participants with non‐toxic multinodular goitre, undergoing recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH)‐aided radioiodine treatment.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnosis of non‐toxic multinodular goitre was based on enlargement of the thyroid, normal TSH (within the normal references), and nodules (≥ 2 nodules) identified with imaging techniques, including sonography, CT or MRI.

Types of interventions

We planned to investigate rhTSH plus radioiodine treatment compared with radioiodine alone.

Concomitant interventions had to be the same in both the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

If a trial included multiple arms, we included any arm that met the review inclusion criteria.

Minimum duration of follow‐up

Minimal duration of follow‐up was one year.

We defined any follow‐up period that extended beyond the original time frame for the primary outcome measure as specified in the power calculation of the trial's protocol, as an extended follow‐up period, also called 'open‐label extension study' (Buch 2011; Megan 2012).

Summary of specific exclusion criteria

We excluded studies of the following category of participants or study design.

Case‐control studies

Studies with follow‐up less than one year

Participants with toxic goitre

Types of outcome measures

We planned to exclude a study if it did not report at least one of our primary or secondary outcome measures. We extracted the following outcomes using the methods and time points specified below.

Primary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life

Hypothyroidism

Adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Thyroid volume

All‐cause mortality

Costs

Method of outcome measurement

Health‐related quality of life: measured by a validated instrument

Hypothyroidism: defined as low serum‐free thyroxine, a high TSH, or both

Adverse events: e.g. number of participants with cervical discomfort, localised pain, or cardiac problems

Thyroid volume: measured by CT, or MRI, or ultrasonography

All‐cause mortality: defined as death from any cause

Costs: based on costs for inpatient clinics, and the number of visits to the outpatient clinics for each group, plus additional costs for services, such as surgery.

Timing of outcome measurement

The follow‐up of radioiodine therapy for non‐toxic multinodular goitre had to be at least one year for all outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Cochrane Register of Studies Online (searched 21 December 2020)

MEDLINE Ovid (MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, and Daily; 1946 to December 18, 2020; searched 21 December 2020)

Scopus (searched 21 December 2020)

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 21 December 2020)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/trialsearch/; searched 21 December 2020)

For detailed search strategies, see Appendix 1. We placed no restrictions on the language of publication when searching the electronic databases, or reviewing reference lists of included studies.

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of included studies, systematic reviews, meta‐analyses, and health technology assessment reports. In addition, we planned to contact authors of included studies to identify any additional information on the retrieved studies, and establish whether we may have missed further studies.

We did not use abstracts or conference proceedings for data extraction, unless full data were available from study authors, because this information source does not fulfil the CONSORT requirements, which consist of "an evidence‐based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomised trials" (Moher 2010). We planned to present information on abstracts or conference proceedings in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. We defined grey literature as records detected in ClinicalTrials.gov or WHO ICTRP.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

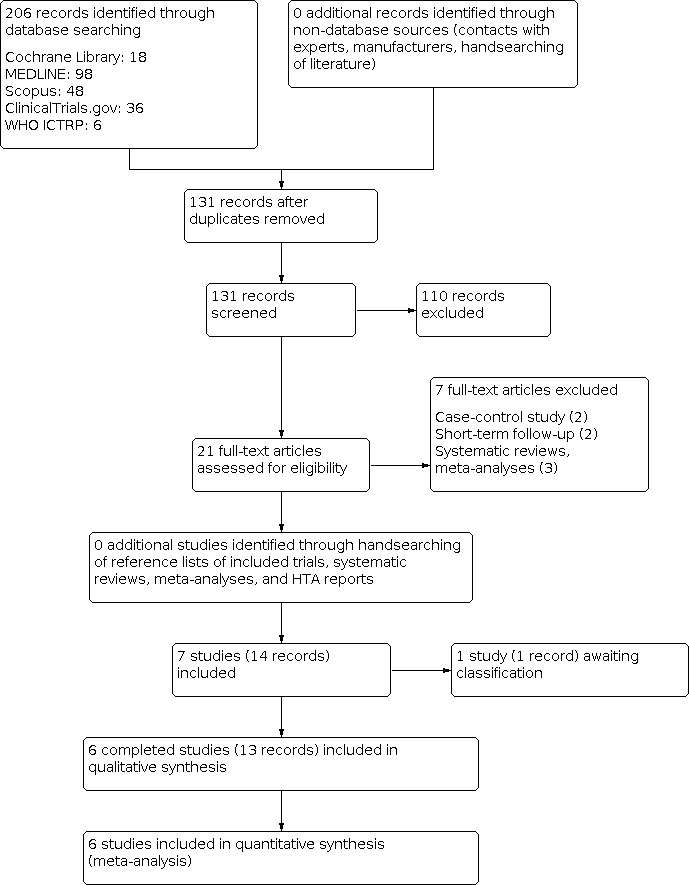

Three review authors (CM, JX, HYL) independently screened the abstracts and titles of every record retrieved by the literature searches, to determine which records we should assess further. We obtained the full‐text of all potentially relevant records. In the case of disagreement, we consulted the remainder of the review team, and made a judgment based on consensus. If we could not resolve a disagreement, we planned to categorise the trial as a 'study awaiting classification', and contact the study authors for clarification. We presented an adapted PRISMA flow diagram to show the process of study selection (Moher 2010). We listed all articles excluded after full‐text assessment in a Characteristics of excluded studies table and provided the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, two review authors (CM, SC) independently abstracted relevant population and intervention characteristics, using standard data extraction templates (for details see Characteristics of included studies; Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13; Appendix 14). In the case of disagreement, we consulted the remainder of the review team, and made a judgment based on consensus. We reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events, using standardised data extraction sheets from the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group Group.

1. Overview of study populations.

| Trial ID (trial design) | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Description of power and sample size calculation | Screened/eligible (N) | Randomised (N) | Analysed (primary outcome) (N) | Finished study (N) | Randomised finished study (%) | Follow‐up |

|

Albino 2010 (parallel RCT) |

I1: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | — | — | 8 | 8 | 8 | 100 | 12 months |

| I2: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 100 | ||||

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 22 | 22 | 22 | 100 | ||||

|

Bonnema 2007 (parallel RCT) |

I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | "Accepting a type I error of 5%, a type II error of 10%, and assuming a SD of 20% on the percent goiter volume reduction, at least 13 patients in each randomization group were required to detect a difference of 25%" | — | 14 | 14 | 14 | 100 | 12 months |

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 29 | 29 | 29 | 100 | ||||

|

Cubas 2009 (parallel RCT) |

I1: 0.005 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | — | — | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100 | 24 months |

| I2: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100 | ||||

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 10 | 10 | 9 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 28 | 28 | 27 | 96 | ||||

|

Fast 2010a (parallel RCT) |

I: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (50 Gy) | — | 594/282 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 100 | 12 months |

| C: placebo + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 30 | 30 | 30 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 90 | 90 | 90 | 100 | ||||

|

Fast 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | "Using a two‐sided t‐test, this study required 29 patients per arm to have an 80% power for the detection of the group difference at a 0.05 significance level" | 141/95 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 36 monthsb |

| I2: 0.03 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 33 | 33 | 33 | 100 | ||||

| C: sodium carboxymethylcellulose + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 95 | 95 | 95 | 100 | ||||

|

Nielsen 2006 (parallel RCT) |

I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake, and 131I half‐life) | "Accepting a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 10% and assuming an SD of 20% on the percentage of goiter volume reduction, at least 21 patients in each randomization group were required to detect a difference of 20%" | — | 28 | 28 | 28 | 100 | 12 months |

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake, and 131I half‐life) | 29 | 29 | 29 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 57 | 57 | 57 | 100 | ||||

| Total | All interventions | 197 | 197 | |||||

| All comparators | 124 | 123 | ||||||

| All interventions and comparators | 321 | 320 | ||||||

— denotes not reported

aPlacebo group: N = 30; rhTSH group combined: N = 60 (rhTSH 24 hr before radioiodine: N = 20; rhTSH 48 hr before radioiodine: N = 20; rhTSH 72 hr before radioiodine: N = 20) bExtension phase of the original study lasting 6 months (10 participants withdrew during the extension phase)

131I: radioactive iodine; C: comparator; GBq: gigabecquerel; Gy: Gray; I: intervention; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation

We provided information about potentially relevant ongoing trials, including the trial identifiers, in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table, and in Appendix 9, a Matrix of trial endpoints (publications and trial documents). We tried to find the protocol for each included trial, and we compared primary, secondary, and other outcomes with the data in publications.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents, or multiple reports of a primary study, we maximised the information yield by collating all available data, and we used the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. We listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a primary study, and trial documents of included studies (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the included study. We also listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a study, and trial documents of excluded studies (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the excluded study.

Data from clinical trials registers

If data from included trials were available as study results in clinical trials registers, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, or similar sources, we made full use of this information and extracted the data. If there was also a full publication of the study, we collated and critically appraised all available data. If an included study was marked as a completed study in a clinical trial register but no additional information (study results, publication or both) was available, we added this study to the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (HW, SQ, HYL) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included trial. In the case of disagreement, we consulted the remainder of the review team, and made a judgment based on consensus. If adequate information was unavailable from the publications, trial protocols, or other sources, we planned to contact the study authors for more detail for risk of bias items.

We used the Cochrane RoB 1 assessment tool, and assigned assessments of low, high, or unclear risk of bias (Corbett 2014; Higgins 2017); for details see Appendix 2; Appendix 3. We evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, according to the criteria and associated categorisations contained therein (Higgins 2017).

Summary assessment of risk of bias

We presented a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias summary figure.

We distinguished between self‐reported and investigator‐assessed, and adjudicated outcome measures.

We considered the following to be self‐reported outcomes.

Health‐related quality of life

Adverse events

We considered the following outcomes to be investigator‐assessed.

Hypothyroidism

Thyroid volume

All‐cause mortality

Costs

Risk of bias for a studies across outcomes

Some risk of bias domains, such as selection bias (sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment), affect the risk of bias across all outcome measures in a study. In cases of high risk of selection bias, we marked all endpoints investigated in the associated study as being at high risk. Otherwise, we did not perform a summary assessment of the risk of bias across all outcomes for a study.

Risk of bias for an outcome within a study and across domains

We assessed the risk of bias for an outcome measure by including all entries relevant to that outcome (i.e. both study‐level entries and outcome‐specific entries). We considered low risk of bias to denote a low risk of bias for all key domains, unclear risk to denote an unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains, and high risk to denote a high risk of bias for one or more key domains.

Risk of bias for an outcome across studies and across domains

These are the main summary assessments that we incorporated into our judgments about the certainty of the evidence in the summary of findings tables. We defined outcomes at low risk of bias when most information came from studies at low risk of bias, unclear risk when most information came from studies at low or unclear risk of bias, and high risk when a sufficient proportion of information came from studies at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least two included studies were available for a comparison and a given outcome, we expressed dichotomous data as a risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes measured on the same scale (e.g. thyroid volume in mL), we estimated the intervention effect using the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes that measured the same underlying concept (e.g. health‐related quality of life) but used different measurement scales, we planned to calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD). We planned to express time‐to‐event data as a hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over studies, cluster‐randomised studies, and multiple observations for the same outcome. If more than one comparison from the same study was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we either combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison, or appropriately reduced the sample size so that the same participants did not contribute data to the meta‐analysis more than once (splitting the 'shared' group into two or more groups). While the latter approach offers some solution to adjusting the precision of the comparison, it does not account for correlation arising from the same set of participants being in multiple comparisons.

We planned to attempt to re‐analyse cluster‐RCTs that did not appropriately adjusted for potential clustering of participants within clusters in their analyses. The variance of the intervention effects was to be inflated by a design effect. Calculation of a design effect involves estimation of an intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). We planned to obtain estimates of ICCs by contacting study authors, or imputing the ICC values by using either estimates from other included studies that reported ICCs, or external estimates from empirical research (e.g. Bell 2013). We planned to examine the impact of clustering using sensitivity analyses.

Dealing with missing data

If possible, we obtained missing data from the authors of the included studies. We carefully evaluated important numerical data, such as screened, randomly assigned participants, as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated, and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up, withdrawals), and we critically appraised issues concerning missing data and use of imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward).

In studies where the standard deviation (SD) of the outcome was not available at follow‐up, or we could not recreate it, we planned to standardise by the mean of the pooled baseline SD from those studies that reported this information.

Where included studies did not report means and SDs for outcomes, and we did not receive the necessary information from study authors, we planned to impute these values by estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of the sample (Hozo 2005).

We planned to investigate the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by performing sensitivity analyses, and we planned to report which studies had imputed SDs, for every outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report study results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis. We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) by visually inspecting the forest plots, and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of α = 0.1 (Deeks 2017). In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies, to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). When we found heterogeneity, we planned to attempt to determine possible reasons for this, by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more studies that investigated a particular outcome, we planned to use funnel plots to assess small‐study effects. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to study size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small studies), and publication bias (Sterne 2017). Therefore, we wanted to interpret the results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to undertake a meta‐analysis only if we judged participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes to be sufficiently similar to ensure an answer that was clinically meaningful. Unless good evidence showed homogeneous effects across trials of different methodological quality, we primarily summarised low risk of bias data using a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration for the whole distribution of effects, and planned to present a prediction interval (Borenstein 2017a; Borenstein 2017b; Higgins 2009). A prediction interval requires 10 studies to be calculated, and specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual trial (Riley 2011).

For rare events, such as event rates below 1%, we planned to use the Peto odds ratio method, provided there was no substantial imbalance between intervention and comparator group sizes, and intervention effects were not exceptionally large. We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and we planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses, including investigation of interactions (Altman 2003).

Age (depending on data)

Dose of rhTSH

Dose of radioiodine

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors (when applicable) on effect sizes, by restricting analysis to the following.

Published studies

Effect of risk of bias, as specified in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section

Very long, or large studies to establish the extent to which they dominate the results

Use of the following filters: diagnostic criteria, imputation, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), or country

We planned to test the robustness of results by repeating analyses using different measures of effect size (i.e. RR, OR, etc.), and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome specified below, according to the GRADE approach, which takes into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), and external validity, such as directness of results. Two review authors (JX, SC) independently rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome. We resolved differences in assessment by discussion, or by consultation with a third review author (CM).

We included a checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments (Appendix 14), to help with standardisation of the summary of findings tables (Meader 2014). Alternatively, we planned to present evidence profile tables, created with GRADEpro GDT, as an appendix (GRADEpro GDT). We presented results for outcomes as described in the Types of outcome measures section. If a meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented the results in a narrative format in the summary of findings table. We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of the evidence by using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the Cochrane Review when necessary.

The summary of findings table provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of effect, in relative terms and as absolute differences, for each comparison of alternative management strategies, numbers of participants and studies that addressed each important outcome, and a rating of overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the summary of findings table using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2017), Review Manager 5 table editor (Review Manager 2020), and GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT).

Interventions presented in the summary of findings table were recombinant TSH plus radioiodine, compared to radioiodine alone.

We reported the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

Health‐related quality of life

Hypothyroidism

Adverse events

All‐cause mortality

Thyroid volume

Costs

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of studies, see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

Our search identified a total of 206 records. We excluded most of the references on the basis of their titles and abstracts because they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. We included six studies, published in 13 records (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Cubas 2009; Fast 2014; Nielsen 2006; Fast 2010), one study is awaiting assessment (NCT00454220; Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

Included studies

A detailed description of the characteristics of included studies is presented elsewhere (see Characteristics of included studies and appendices). The following is a succinct overview.

Source of data

We obtained all data from the published literature.

Comparisons

The included studies compared recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH)‐aided radioiodine therapy with radioiodine therapy alone (plus placebo, usually isotonic saline).

Overview of study populations

Six studies included a total of 321 participants; 197 participants were randomised to rhTSH‐aided radioiodine, and 124 participants to radioiodine alone. With the exception of one study, all randomised participants finished the studies as planned (Cubas 2009). The individual sample size ranged from 22 to 95.

Study design

All included studies adopted a parallel‐group superiority design, and used a placebo control.

Five trials were conducted in single centre (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Cubas 2009; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006); one study was conducted in 13 centres from six countries (Fast 2014).

Four studies were double‐blinded for participants and personnel (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006), one study was single‐blinded for participants (Fast 2014), and one study did not report blinding conditions (Cubas 2009). Outcome assessors were blinded in four studies (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006).

The studies were conducted between 2002 and 2014. The duration of follow‐up ranged from 12 to 36 months. No study had a run‐in period. No study was terminated early.

Settings

Two of the six studies were conducted in Brasil (Albino 2010; Cubas 2009); three were completed in Denmark (Bonnema 2007; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006); one multicentre study was conducted in Denmark, Italy, Brazil, Germany, France, and Canada (Fast 2014).

Five studies were conducted in an outpatient setting (Albino 2010; Cubas 2009; Fast 2010; Fast 2014; Nielsen 2006); one in a hospital (Bonnema 2007).

Participants

Ethnic groups were not mentioned in five studies (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Cubas 2009; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006). The duration of the multinodular goitre was not reported. Women represented the majority of participants in all studies (71% to 100%). The mean age of participants in the studies ranged from 32 to 87 years. Three studies provided limited data on co‐medications, co‐interventions, or comorbidities (Albino 2010; Cubas 2009; Nielsen 2006).

Diagnosis

Participants were diagnosed with non‐toxic multinodular goitre based on thyroid function tests and fine needle aspiration biopsy (Albino 2010), or thyroid function tests with thyroid scintigraphy and ultrasonography (Bonnema 2007; Cubas 2009; Fast 2010; Fast 2014; Nielsen 2006)

Interventions

Two studies reported treatment before the start of the study, which included the methimazole until euthyroidism was achieved (Fast 2010; Cubas 2009). No study had a titration period. Recombinant human thyrotropin was administered intramuscularly, in a single dose. The dose of rhTSH varied between 0.005 mg and 0.3 mg, with an average dose of 0.106 mg. The six studies used a matching placebo as the control intervention.

Outcomes

The six studies explicitly stated a primary endpoint and secondary endpoints.

One study evaluated health‐related quality of life using a specific questionnaire (Fast 2014). Hypothyroidism and thyroid volume reduction were measured in all studies. All studies reported on adverse events. One study reported on deaths (Cubas 2009). No study investigated costs. For details see Appendix 10.

Excluded studies

We excluded seven studies after careful evaluation of the full publications. For further details, see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on risk of bias of included studies see Characteristics of included studies.

For an overview of review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for individual studies and across all studies see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

We investigated performance bias, detection bias, and attrition bias separately for objective and subjective outcome measures. We defined all‐cause mortality, thyroid volume, hypothyroidism, and costs as objective outcome measures, and adverse events (e.g. local tenderness, tracheal compression, cardiac symptoms), and health‐related quality of life as subjective outcomes.

Allocation

Randomisation sequence generation was unclear in all studies except one (Bonnema 2007). Allocation concealment was unclear in all studies.

Blinding

Four studies explicitly stated that blinding of the participants and personnel was undertaken, and we judged them as low risk of bias (Albino 2010; Bonnema 2007; Fast 2010; Nielsen 2006). Fast 2014 had a single‐blind design with masking of the participants. Cubas 2009 did not report blinding conditions.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies described the number of study withdrawals, and study authors reported that they performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Overall, we judged attrition bias as low for all studies.

Selective reporting

We did not identify reporting bias for any of the included studies.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other bias for our included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Baseline characteristics

For details of baseline characteristics, see Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

Recombinant human thyrotropin‐aided radioiodine compared with radioiodine alone

Primary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life

There were no clear differences in symptom improvement in the 17 goitre‐specific questions and overall quality of life question among the treatment groups at 6 and 36 months (1 study, 85 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

More than 50% of the participants reported no baseline symptoms for 9 of the 17 goitre‐specific questionnaire items. Considering only participants who reported symptoms at baseline, the majority reported an improvement in symptoms after treatment for almost all goitre‐specific items and in all treatment groups.

Hypothyroidism

A total of 64/197 participants (32.5%) in the rhTSH‐aided radioiodine group and 15/124 participants (12.1%) in the radioiodine only group experienced hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism increased following rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment (risk ratio (RR) 2.53, 95% CI 1.52 to 4.20; P < 0.001; 6 studies, 321 participants; Analysis 1.1; moderate‐certainty evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: rhTSH‐aided radioiodine versus radioiodine only, Outcome 1: Hypothyroidism

Adverse effects

A total of 118/197 participants (59.9%) in the rhTSH‐aided radioiodine group and 60/124 participants (48.4%) in the radioiodine only group experienced adverse events, such as mild cervical discomfort or localised pain (for details, see Appendix 13).

The random‐effects model did not show evidence of a difference for adverse events (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.63; P = 0.13; 6 studies, 321 participants; Analysis 1.2; low‐certainty evidence). The fixed‐effect model showed a RR of 1.23, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.49; P = 0.03 in favour of radioiodine only.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: rhTSH‐aided radioiodine versus radioiodine only, Outcome 2: Adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Thyroid volume

RhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment reduced thyroid volume more than radioiodine only (mean difference (MD) 11.91%, 95% CI 4.43 to 19.40; P = 0.002; 6 studies, 268 participants; Analysis 1.3; moderate‐certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: rhTSH‐aided radioiodine versus radioiodine only, Outcome 3: % of thyroid volume reduction

All‐cause mortality

Only one study reported deaths (Cubas 2009): one out of 10 participants in the radioiodine alone group died, compared with none out of 18 participants in the rhTSH‐aided radioiodine group (very low‐certainty evidence).

Costs

No study reported on this outcome measure.

Subgroup analyses

We did not perform subgroups analyses because there were not enough studies to estimate effects in various subgroups.

Sensitivity analyses

With the exception for the outcome adverse events we did not perform sensitivity analyses due to lack of data.

Assessment of reporting bias

We did not draw funnel plots due to limited number of studies.

Awaiting classification

We identified one single‐blind study, planning to enrol approximately 96 participants, investigating 0.01 mg rhTSH or 0.03 mg rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy versus radioiodine alone (NCT00454220). Study completion date was reported in ClinicalTrials.gov as July 2011; no publication was available.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Only limited data were available from six studies that compared rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy with radioiodine alone for non‐toxic multinodular goitre (Table 1). rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy reduced thyroid volume over radioiodine therapy alone, but it also increased hypothyroidism. Using a random‐effects model, the findings were inconclusive between groups regarding the risk of experiencing adverse events, which included mild cervical discomfort, localised pain, and cardiac problems. When we used a fixed‐effect model, we got a similar estimate of risk, but the confidence interval shifted to the right, suggesting that rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy might result in more adverse events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included studies differed in terms of diagnosis of non‐toxic multinodular goitre, and in medication used before enrolment, to ensure euthyroidism before therapy. Health‐related quality of life was measured with a validated questionnaire in one study only (Fast 2010). Thyroid volume was measured in different ways, e.g. by ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging, limiting the comparability of intervention effects. Information on co‐medications, co‐interventions, and comorbidities was limited.

Quality of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence was moderate for hypothyroidism and reduction of thyroid volume, due to imprecision. We are very uncertain about the certainty of the evidence for health‐related quality of life and all‐cause mortality, due to very serious imprecision. The certainty of the evidence was low for adverse events due to serious imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

Our body of evidence was limited because only six RCTs with follow‐up of at least one year or longer were available. We could have identified more studies had we included shorter follow‐up periods, however, the development of hypothyroidism and reduction of thyroid volume need time in non‐toxic multinodular goitre. One study awaiting assessment, with long‐term follow‐up, could potentially contribute to the findings of our review, but it was never published. We did not have adequate information for a judgement of selection bias, because no publication provided enough details. We are uncertain about adverse effects, because our findings were not robust using different statistical models. Additional studies could provide a better picture of the risk‐benefit ratio of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment compared with radioiodine alone.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our review agrees with the findings of a recently published systematic review (Xu 2020): the authors of this review also reported a higher incidence of hypothyroidism following rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy and a reduction in goitre volume especially after a higher dose of rhTSH.

A greater reduction in thyroid volume seems to be the most important effect of rhTSH administered before radioiodine (Giusti 2006). The dose of rhTSH for thyroid residual ablation was reported in a study as 0.45 mg per day, for two consecutive days, in people with differentiated thyroid cancer after thyroidectomy (Ma 2010). A flat dose‐response curve existed over the range of rhTSH doses tested, with an approximate doubling of thyroid radioiodine uptake (Braverman 2008). The dose of rhTSH varied in the studies, ranging from 0.005 mg to 0.3 mg. We could not analyse the therapeutic effects of rhTSH doses, due to the limited number of included studies. A very low dose of 0.005 mg rhTSH was equally safe and effective as 0.1 mg rhTSH, followed by a fixed radiation dose of 1.11 GBq (Cubas 2009). A 0.3 mg rhTSH dose seemed to be as efficacious as a 0.9 mg dose in people with multinodular goitre (Duick 2003). In people with symptomatic toxic or nontoxic multinodular goitre, 0.1 mg and 0.3 mg of rhTSH were equally efficacious at inducing a quadrupling of the low, or low‐normal baseline radioiodine values, at 72 hours after injection (Azorín 2017; Duick 2004). A recent RCT reported that a single dose of 0.03 mg rhTSH was well tolerated, and increased the radioiodine uptake in people with euthyroid, and subclinical hyperthyroid goitre (Mojsak 2016). A long‐term controlled study demonstrated that 0.2 mg of rhTSH, on two consecutive days, increased the efficacy of ambulatory radioiodine dosages in treating non‐toxic multinodular goitre in elderly people. However, high doses of rhTSH should be cautiously recommended for people with non‐toxic multinodular goitre, who are elderly and sick.

RhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapy for non‐toxic multinodular goitre led to more adverse events, including cervical discomfort, localised pain, cardiac problems, and hypothyroidism, which were usually mild, transient, and readily treatable. These effects are probably dose‐dependent. Acute adverse effects are due to the surge of the thyroid hormone in the blood, and to the increase in goitre volume, which cause cardiac symptoms and tracheal compression. In healthy individuals, rhTSH‐induced thyroid swelling and hyperthyroidism is rapid and dose‐dependent. For people with goitre, results suggested that these adverse effects are unlikely to be of clinical significance, following doses of rhTSH of 0.1 mg or less (Fast 2010). Theoretically, the rise in thyroid hormone levels and adverse effects after rhTSH doses of 0.1 mg or higher, might not be well tolerated in older or sicker people, and appear unjustified, given the lack of a increased rise in radioiodine uptake compared with the 0.03 mg dose (Duick 2004). Neither compression of the trachea, nor deterioration of the pulmonary function was observed in the acute phase, after rhTSH‐augmented radioiodine therapy. In the long term, tracheal compression may diminish, and the inspiratory capacity improve, compared with radioiodine therapy alone (Bonnema 2008). RhTSH‐stimulated radioiodine treatment of non‐toxic multinodular goitre did not affect the structural and functional parameters of the heart, despite transient high serum levels of thyroid hormones (Barca 2007). The dose of rhTSH to achieve the most therapeutic effects and least adverse effects should be investigated in future studies.

No study reported long‐term adverse effects (e.g. radiation‐induced malignancy) of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine treatment for non‐toxic multinodular goitre. RhTSH not only increases the thyroid radioiodine uptake (Ceccarelli 2011), but per se potentiates the effect of radioiodine therapy, allowing a major reduction of the radioiodine activity without compromising efficacy. This approach is intriguing in terms of minimising the long‐term risk of radiation‐induced malignancy, and in reducing the costs and inconvenience of inpatient treatment (Fast 2010). The use of lower radioiodine activities reduces the radiation burden to the body, and the time of social life restriction. Moreover, depending on the radiation regulations of the different countries, radioiodine therapy could be carried out either as outpatients, or in a shorter hospitalisation period, implying a decrease of costs (Ceccarelli 2010).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Moderate‐certainty evidence from six randomised controlled clinical trials, in 321 participants, suggested that recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH) radioiodine for nontoxic multinodular goitre reduces thyroid volume more than radioiodine alone. However, moderate‐certainty evidence also showed radioiodine alone led to a lower risk of hypothyroidism.

Implications for research.

Future randomised controlled trials (RCTs) should investigate the incidence of secondary malignancies following different radiation doses, as well as long‐term health‐related quality of life. RCTs should also try to identify the best rhTSH dose, and costs of rhTSH‐aided radioiodine therapies for non‐toxic multinodular goitre.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 6, 2013

Notes

We based parts of the Methods, Appendix 1, Appendix 5, and Appendix 6 of the Cochrane Protocol on a standard template established by the CMED group.

Acknowledgements

The search strategies for the English language databases and trials registers were designed by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group's (CMED) Information Specialist, Maria‐Inti Metzendorf.

The review authors and the CMED editorial base are grateful to the peer reviewer Bianca Hemmingsen, Denmark for her time and comments.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane Register of Studies Online) |

| 1. MESH DESCRIPTOR Goiter, Nodular 2. MESH DESCRIPTOR Thyroid Nodule 3. (thyroid ADJ3 nodule*):TI,AB,KY 4. ((goiter* OR goitre*) ADJ6 (nodular OR multinodular OR multi‐nodular OR nontoxic OR non‐toxic)):TI,AB,KY 5. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 6. MESH DESCRIPTOR Iodine Radioisotopes 7. MESH DESCRIPTOR Radiopharmaceuticals 8. (radioiodine* or radioactive iodine*):TI,AB,KY 9. (131J OR J131 OR I131 OR 131I):TI,AB,KY 10. #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 11. MESH DESCRIPTOR Thyrotropin alfa 12. (thyrotropin alfa):TI,AB,KY 13. rhTSH*:TI,AB,KY 14. (recombinant ADJ6 ("human TSH" OR thyrotropin*)):TI,AB,KY 15. #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 16. #5 AND #10 AND #15 |

| MEDLINE Ovid |

| 1. Goiter, Nodular/ 2. Thyroid Nodule/ 3. (thyroid adj3 nodule?).tw. 4. (goiter? adj6 (nodular or multinodular or multi‐nodular or nontoxic or non‐toxic)).tw. 5. (goitre? adj6 (nodular or multinodular or multi‐nodular or nontoxic or non‐toxic)).tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. Iodine Radioisotopes/ 8. Radiopharmaceuticals/ 9. (radioiodine* or radioactive iodine*).tw. 10. (131J or J131 or I131 or 131I).tw. 11. or/7‐10 12. Thyrotropin Alfa/ 13. thyrotropin alfa.tw. 14. rhTSH?.tw. 15. (recombinant adj6 (human TSH or thyrotropin*)).tw. 16. or/12‐15 17. 6 and 11 and 16 |

| Scopus |

| 1. TITLE‐ABS("thyroid nodule*" OR ((goiter* OR goitre*) W/6 (nodular OR multinodular OR multi‐nodular OR nontoxic OR non‐toxic))) 2. TITLE‐ABS(radioiodine* OR "radioactive iodine*" OR 131J OR J131 OR I131 OR 131I OR 131) 3. TITLE‐ABS("thyrotropin alfa" OR rhTSH* OR (recombinant W/6 ("human TSH" OR thyrotropin*))) 4. #1 AND #2 AND #3 5. TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(random* OR "clinical trial*" OR "double blind*" OR placebo*) 6. #4 AND #5 |

| WHO ICTRP Search Portal (standard search) |

| goiter* AND thyrotropin* OR goiter* AND recombinant OR goiter* AND rhTSH OR goitre* AND thyrotropin* OR goitre* AND recombinant OR goitre* AND rhTSH OR nodule* AND thyrotropin* OR nodule* AND recombinant OR nodule* AND rhTSH |

| ClinicalTrials.gov (expert search) |

| (goiter OR goitre OR goiters OR goitres OR "thyroid nodule" OR "thyroid nodules") AND (thyrotropin OR rhTSH OR recombinant) |

Appendix 2. Selection bias decisions

| Selection bias decisions for studies that reported unadjusted analyses: comparison of results obtained using method details alone versus results obtained using method details and study baseline informationa | |||

| Reported randomisation and allocation concealment methods | Risk of bias judgement using methods reporting | Information gained from study characteristics data | Risk of bias using baseline information and methods reporting |

| Unclear methods | Unclear risk | Baseline imbalances present for important prognostic variable(s) | High risk |

| Groups appear similar at baseline for all important prognostic variables | Low risk | ||

| Limited or no baseline details | Unclear risk | ||

| Would generate a truly random sample, with robust allocation concealment | Low risk | Baseline imbalances present for important prognostic variable(s) | Unclear riskb |

| Groups appear similar at baseline for all important prognostic variables | Low risk | ||

| Limited baseline details, showing balance in some important prognostic variablesc | Low risk | ||

| No baseline details | Unclear risk | ||

| Sequence is not truly randomised or allocation concealment is inadequate | High risk | Baseline imbalances present for important prognostic variable(s) | High risk |

| Groups appear similar at baseline for all important prognostic variables | Low risk | ||

| Limited baseline details, showing balance in some important prognostic variablesc | Unclear risk | ||

| No baseline details | High risk | ||

| aTaken from Corbett 2014; judgements highlighted in bold indicate situations in which the addition of baseline assessments would change the judgement about risk of selection bias compared with using methods reporting alone. bImbalance was identified that appears likely to be due to chance. cDetails for the remaining important prognostic variables are not reported. | |||

Appendix 3. Risk of bias assessment

| Risk of bias domains |

|

Random sequence generation (selection bias due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence) For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

Allocation concealment (selection bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation prior to assignment) For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment, and we assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We also evaluated study baseline data to incorporate assessment of baseline imbalance into the risk of bias judgement for selection bias (Corbett 2014). Chance imbalances may also affect judgements on the risk of attrition bias. In the case of unadjusted analyses, we distinguished between studies that we rated as being at low risk of bias on the basis of both randomisation methods and baseline similarity, and studies that we judged as being at low risk of bias on the basis of baseline similarity alone (Corbett 2014). We reclassified judgements of unclear, low, or high risk of selection bias as specified in Appendix 3. Blinding of participants and study personnel (performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study) We evaluated the risk of detection bias separately for each outcome. We noted whether endpoints were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed, or adjudicated outcome measures (see below).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessment) We evaluated the risk of detection bias separately for each outcome. We noted whether endpoints were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed, or adjudicated outcome measures (see below).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias due to quantity, nature, or handling of incomplete outcome data) For each included study, or each outcome, or both, we described the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analyses. We stated whether the study reported attrition and exclusions, and we reported the number of participants included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the number of randomised participants per intervention/comparator groups). We also noted if the study reported the reasons for attrition or exclusion, and whether missing data were balanced across groups, or were related to outcomes. We considered the implications of missing outcome data per outcome, such as high dropout rates (e.g. above 15%), or disparate attrition rates (e.g. difference of 10% or more between study arms).

Selective reporting (reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting) We assessed outcome reporting bias by evaluating the results of the appendix 'Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents).'

Other bias

|

Appendix 4. Descriptions of participants

| Study ID | Criteria | Description |

| Albino 2010 | Inclusion criteria | Participants with euthyroid benign goitres |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants with below normal TSH levels | |

| Diagnostic criteria | Participants with normal TSH levels, multinodular goitre and excluded malignancy (fine needle aspiration biopsy of the dominant and/or suspect nodules and by cytology studies) | |

| Bonnema 2007 | Inclusion criteria | Participants with euthyroid benign goitres |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants with a history of cardiac failure or ventricular arrhythmias, previous malignant disease, or physical or psychiatric disabilities suggestive of difficulties in adherence to the protocol | |

| Diagnostic criteria | The diagnosis was based on clinical examination, 99mTc scintigraphy, and ultrasonography | |

| Cubas 2009 | Inclusion criteria | Participants with euthyroid benign goitres |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants with previous surgery, TSH‐suppressive therapy with T4, or radioactive iodine treatment, serious medical conditions | |

| Diagnostic criteria | The diagnostic setup included clinical examination, 131I thyroid scintigraphy, and ultrasonography | |

| Fast 2010 | Inclusion criteria | Non‐pregnant, non‐lactating participants older than 18 yr, with a nontoxic nodular goitre (i.e. thyroid volume above 28 mL and two or more nodules larger than 1 cm), the presence of goitre‐related symptoms (i.e. pressure, cosmetic complaints, or both), subclinical hyperthyroidism (i.e. serum TSH < 0.30 mU/L and normal serum T4 and T3 levels), or subclinical hyperthyroidism alone |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants with subclinical hyperthyroidism were required to have hyperthyroid symptoms that did not necessitate the use of antithyroid drugs or ‐blockers | |

| Diagnostic criteria | The diagnostic setup included clinical examination, thyroid function tests, 99mTc scintigraphy, and ultrasonography | |

| Fast 2014 | Inclusion criteria | Participants with euthyroid benign goitres |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants with previous partial or near total thyroidectomy, a history of 131I therapy, or a history of therapy alone | |

| Diagnostic criteria | The diagnostic setup included clinical examination, thyroid function tests, and ultrasonography | |

| Nielsen 2006 | Inclusion criteria | Participants with euthyroid or subclinical hyperthyroid benign goitres |

| Exclusion criteria | Participants who were averse to any treatment, were younger than 18 years, had intrathoracic goitre > 100 mL, had previous 131I therapy, were unable to complete follow‐up, had a 24‐hour thyroid 131I uptake < 20% | |

| Diagnostic criteria | The diagnostic setup included clinical examination, thyroid function tests, 99mTc scintigraphy, and ultrasonography | |

| T3: triiodothyronine;T4: thyroxine;99mTc: Technetium‐99m; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone | ||

Appendix 5. Description of interventions

| Study ID | Intervention(s) | Comparator |

| Albino 2010 | I1: a 1.1 mg vial of rhTSH was diluted with 1.2 mL sterile water for injection, resulting in a 1 mL drawable solution of rhTSH concentrated at 0.9 ng/mL. A 1.0 mL aliquot of this solution was then diluted with 9 mL sterile water for injection, which resulted in a 0.1 mg/mL solution, which was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to radioiodine treatment | 1.0 mL isotonic saline was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to radioiodine treatment |

| I2: in order to obtain the 0.01 mg/mL solution of rhTSH, 1 mL of the 0.1 mg solution was diluted with 9 mL sterile water, which was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to radioiodine treatment | ||

| Bonnema 2007 | 1.0 mL of the solution (0.3 mg rhTSH) was intramuscularly injected in the gluteal region 24 hours before 131I therapy | 1.0 mL isotonic saline was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to the 131I therapy |

| Cubas 2009 | I1: a single dose of 1.0 ml (0.1 mg) of rhTSH, which was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to radioiodine treatment | 1.0 mL isotonic saline was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to the 131I therapy |

| I2: a single dose of 1.0 mL (0.005 mg) of rhTSH, which was intramuscularly injected 24 hours prior to radioiodine treatment | ||

| Fast 2010 | A vial containing 0.9 mg rhTSH was reconstituted to a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL (administered in the gluteal region), followed by a thyroid dose of 50 Gy. RhTSH was given 24 hours, 48 hours, or 72 hours before radioiodine | 1 mL isotonic saline, followed by a thyroid dose of 100 Gy. Placebo was given 24 hours, 48 hours or 72 hours before radioiodine |

| Fast 2014 | I1: 0.01 mg rhTSH was administered by intramuscular injection in the gluteal region 24 hours before 131I therapy | The placebo injection was 0.5 mL of the same concentration of sodium carboxymethylcellulose |

| I2: 0.03 mg rhTSH was administered by intramuscular injection in the gluteal region 24 hr before 131I therapy | ||

| Nielsen 2006 | 0.3 mg of rhTSH was injected intramuscularly into the gluteal region 24 hours prior to 131I therapy | The placebo injection constituted 1 mL isotonic saline in the gluteal region 24 hours prior to 131I therapy |

| GBq: giga Becquerel; Gy: Gray; I: intervention; rhTSH: recombinant human thyrotropin. | ||

Appendix 6. Baseline characteristics (I)

| Study ID | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Duration of follow‐up | Participants | Study period | Country | Setting | Ethnic groups (%) | Duration of goitre |

| Albino 2010 | I1: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 12 months | participants with multinodular goitre | — | Brazil | outpatients | — | — |

| I2: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | ||||||||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | ||||||||

| Bonnema 2007 | I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | 12 months | participants with euthyroid benign goitres | 2002 to 2005 | Denmark | inpatients | — | — |

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | ||||||||

| Cubas 2009 | I1: 0.005 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 24 months | participants with euthyroid benign goitres | — | Brazil | outpatients | — | — |

| I2: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | ||||||||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | ||||||||

| Fast 2010 | I: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (50 Gy) | 12 months | participants with nontoxic nodular goitre with 2 or more nodules larger than 1 cm, and the presence of goitre‐related symptoms (pressure or cosmetic complaints, or both), subclinical hyperthyroidism, or subclinical hyperthyroidism alone | 2006 to 2008 | Denmark | outpatients | — | — |

| C: placebo + radioiodine (100 Gy) | ||||||||

| Fast 2014 | I1: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 36 months | participants with euthyroid benign goitres | — | Denmark, Italy, Brazil, Germany, France, Canada | outpatients | Black (9), white (88), mixed (3) | — |

| I2: 0.03 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | ||||||||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (100 Gy) | ||||||||

| Nielsen 2006 | I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake and 131I half‐life) | 12 months | participants with euthyroid benign goitres | 2002 to 2004 | Denmark | outpatients | — | — |

| C: placebo + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake and 131I half‐life) | ||||||||

| —: denotes not reported 131I: radioactive iodine; C: comparator; GBq: giga Becquerel; Gy: Gray; I: intervention; rhTSH: recombinant human thyrotropin | ||||||||

Appendix 7. Baseline characteristics (II)

| Study ID | Intervention and comparator | % women | Age (mean/range years (SD)) | Comedications / Cointerventions / Comorbidities |

| Albino 2010 | I1: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 88 | 62 (44 to 74) | All participants were advised to follow a low‐iodine diet, starting 2 weeks prior to the administration of the diagnostic and therapeutic activities of radioiodine |

| I2: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 100 | 61 (52 to 72) | ||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 88 | 60 (33 to 72) | ||

| Bonnema 2007 | I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | 71 | 57 (42 to 84) | — |

| C: isotonic saline + radioiodine (aiming at a thyroid dose of 100 Gy) | 80 | 65 (37 to 87) | ||

| Cubas 2009 | I1: 0.005 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 100 | 60 (48 to 73) | None of the participants had serious medical conditions and all of them had subclinical hyperthyroidism (which was treated with methimazole), or were euthyroid |

| I2: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 100 | 61 (49 to 73) | ||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (1.11 GBq) | 80 | 62 (45 to 86) | ||

| Fast 2010 | I: 0.1 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (50 Gy) | 83 | 52 (22 to 83) | — |

| C: placebo + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 93 | 55 (27 to 78) | — | |

| Fast 2014 | I1: 0.01 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 97 | 57.3 (10.2) | — |

| I2: 0.03 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (100 Gy) | 76 | 56.9 ± 10.3 | ||

| C: placebo and radioiodine (100 Gy) | 84 | 57.5 (8.7) | ||

| Nielsen 2006 | I: 0.3 mg rhTSH + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake, and 131I half‐life) | 86 | 52 (32 to 68) | 6% of participants had previous thyroidectomy |

| C: placebo + radioiodine (calculated based on thyroid size, thyroid 131I uptake, and 131I half‐life) | 93 | 52 (26 to 77) | 5% of participants had previous thyroidectomy | |