Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to estimate the annual mortality risk and its determinants in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy.

Methods and results

We conducted a systematic search in MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collection, Embase, Cochrane Library, and LILACS. Longitudinal studies published between 1 January 1946 and 24 October 2018 were included. A random‐effects meta‐analysis using the death rate over the mean follow‐up period in years was used to obtain pooled estimated annual mortality rates. Main outcomes were defined as all‐cause mortality, including cardiovascular, non‐cardiovascular, heart failure, stroke, and sudden cardiac deaths. A total of 5005 studies were screened for eligibility. A total of 52 longitudinal studies for chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy including 9569 patients and 2250 deaths were selected. The meta‐analysis revealed an annual all‐cause mortality rate of 7.9% [95% confidence interval (CI): 6.3–10.1; I 2 = 97.74%; T 2 = 0.70] among patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. The pooled estimated annual cardiovascular death rate was 6.3% (95% CI: 4.9–8.0; I 2 = 96.32%; T 2 = 0.52). The annual mortality rates for heart failure, sudden death, and stroke were 3.5%, 2.6%, and 0.4%, respectively. Meta‐regression showed that low left ventricular ejection fraction (coefficient = −0.04; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.02; P = 0.001) was associated with an increased mortality risk. Subgroup analysis based on American Heart Association (AHA) classification revealed pooled estimate rates of 4.8%, 8.7%, 13.9%, and 22.4% (P < 0.001) for B1/B2, B2/C, C, and C/D stages of cardiomyopathy, respectively.

Conclusions

The annual mortality risk in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy is substantial and primarily attributable to cardiovascular causes. This risk significantly increases in patients with low left ventricular ejection fraction and those classified as AHA stages C and C/D.

Keywords: Chagas, Cardiomyopathy, Mortality

Introduction

Chagas disease, otherwise known as American Trypanosomiasis, is a protozoal infection caused by the haemoflagellate, Trypanosoma cruzi. The creation of four regional surveillance and control initiatives with support from the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization has had a major impact on the disease prevalence in Latin America by reducing the number of infected people from 30 million in the 1990s to approximately 6–8 million in recent years. 1 Increasing migration of infected individuals from Chagas endemic regions to non‐endemic countries has reshaped Chagas disease into a global public health problem. Although likely an underestimation, T. cruzi affects nearly 300 000 individuals in the USA, over 100 000 immigrants in Europe, and several thousand cases dispersed in Canada, Australia, and Japan. 2 , 3 The transmission mode is predominantly vector‐borne or oral through consumption of food products contaminated with faeces of reduviid bugs. Less frequently, the infection may occur vertically from mother to child, via transfusion of blood products or organ transplantation. Although there have been important achievements in the understanding and control of the disease, many challenges related to epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics, barriers to care, vector ecology, prevention, and treatment need to be urgently addressed.

Chagas disease evolves through acute and chronic phases. Patients with acute or indeterminate infection progress to chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) at a rate of 4.6% and 1.9% annually, respectively. 4 Chronic cardiac disease is divisible into five stages per the last adapted American Heart Association (AHA) classification—A (indeterminate), B1 [structural changes with normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)], B2 (structural changes with abnormal LVEF), C [ventricular dysfunction with heart failure (HF) symptoms], and D (refractory HF). 5 Categories B1–D have evidence of structural cardiac damage by standard clinical evaluation. Structural changes are usually detected by electrocardiography and echocardiography and include ventricular arrhythmias, sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular and intraventricular blocks, segmental and global wall motion abnormalities, and ventricular aneurysms. Additional complications arising from CCC include congestive heart failure (CHF), thromboembolism (mainly stroke), and death. 6 Patients with additional comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease are at increased risk of these cardiovascular (CV) complications.

Appraisal of clinical outcomes and mortality risk in CCC has proven to be challenging due to the heterogeneity of studies with inclusion of patients at differing disease stages, variations in independent prognostic factors and risk calculators, studies with different follow‐up periods, patient populations with various comorbidities, and studies lacking statistical power. A previous meta‐analysis by Cucunubá et al. 7 compared mortality rates between populations with and without Chagas disease. Patients with Chagas disease had a significantly higher annual mortality rate (AMR) (18% vs. 10%), which was preserved regardless of the stage of the disease: severe (43% vs. 29%), moderate (16% vs. 8%), and asymptomatic (2% vs. 1%). However, the authors included only studies with a control group for comparison, and causes of death and prognostic factors were not an issue. Our systematic review and meta‐analysis is the first one to assess pooled estimated AMRs (all‐cause and by specific modes) in the overall population and in distinct subgroups of patients with CCC, as well as the determinants of death.

Methods

Search strategy

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for systematic reviews and meta‐analysis with a three‐phase search strategy was utilized. 8 This review considered longitudinal studies, prospective and retrospective cohorts, case series, and randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Studies exploring rates of progression, prognostic factors, and relevant clinical outcomes in CCC were included.

An initial comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE was conducted in October 2018 by a medical librarian. Relevant publications were identified by screening titles and abstracts and searching for a combination of indexing terms (when applicable, specific to each database) and keywords for Chagas disease and disease progression concepts. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Ovid MEDLINE® and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions®, 1946 to present), MEDLINE (via PubMed, 1946 to present), Web of Science Core Collection (via Clarivate Analytics, including Science Citation Index Expanded 1974 to present, and Social Sciences Citation Index 1974 to present), Embase (via Elsevier, Embase.com, 1947 to present), Cochrane Library (via Wiley, including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, via BV Salud, 1982 to present).

The reference list of all studies selected for critical appraisal was screened for additional studies, and other important articles in the field were manually added. There were no restrictions or limits on the date of publication or age of subjects. The language was restricted to English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Articles written in Spanish or Portuguese were reviewed by the authors (A. H. M., C. F. P., A. R., and A. M.) who are fluent in both languages. Filters were used to limit results to human studies.

Study selection

After the search, all identified studies were uploaded and de‐duplicated in EndNote VX8 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA). Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) was used for screening and full‐text review. See eMethods (Supporting Information) for a list of Ovid and PubMed MEDLINE search strategy. Through Covidence, a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was generated with the number of results found, number excluded during title/abstract screening, and number excluded during full‐text assessments and methodological appraisals, along with reasons for exclusion. Other sources searched included ClinicalTrials.gov (United States National Library of Medicine) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP, <http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/>).

Additional details on the systematic review protocol are already published (https://journals.lww.com/jbisrir/Fulltext/2019/10000/Duration_and_determinants_of_Chagas_latency__an.9.aspx). Systematic review registration number: PROSPERO CRD42019118019.

Inclusion criteria

Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy is confirmed with two positive serological tests based on different antigens and/or techniques and structural cardiomyopathy, evidenced by typical electrocardiographic or echocardiographic changes with or without global ventricular dysfunction and HF symptoms. All ages, genders, and ethnicities with a longitudinal observation and established diagnosis of a chronic determinate form of the disease until the development of the outcome of interest were included. Studies were excluded if they did not state enough or pertinent outcome data or were determined not to have an acceptable quality methodologic assessment.

Data analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Colorado Denver. Extracted data included type of study, country of origin, number of participants, length of follow‐up, population demographics, stages of cardiomyopathy, study methods, interventions (diagnostic and therapeutic), and outcomes of significance. The following outcomes were extracted: (i) overall all‐cause mortality and (ii) specific mortality for CV, HF, sudden cardiac death (SCD), stroke and noncardiac outcomes. CV mortality was a composite of SCD, HF, and stroke deaths.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers with expertise in Chagas disease (A. H. M. and A. R.) independently revised the selected studies for methodological quality, performing quality critical standard measures from JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI; Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide, Australia). A third reviewer was asked to reconcile disagreements between the two reviewers. Critical appraisals were performed utilizing the JBI Reviewer's Manual checklists for longitudinal studies. All studies with greater than 60% of ‘yes’ answers to the critical appraisal questions were subject to data extraction and synthesis.

Statistical analysis

Event rates were extracted by calculating the total number of deaths over the number of cases divided by the mean follow‐up in years. The extracted ratio was log‐transformed, and standard errors were obtained from the cumulative percentage of deaths, the number of participants, and the duration of the study. Log transformation of the estimated rates reduced the skew of their distributions.

A random‐effects meta‐analysis was then performed to combine the estimated log rates from the different studies into a single estimated log rate, which was back‐transformed for interpretation. Between‐study heterogeneity was estimated using the I 2 statistic. New York Heart Association (NYHA) extraction was recorded as the percentage of I/II or III/IV classes of participants in each study. The studies were classified as AHA stages B1, B1/B2, B1/B2/C, B2/C, C, and C/D based on the analysis of the clinical characteristics of the majority of subjects included in each study. In addition, by analysing the titles of the manuscripts and the population characteristics in each study, we were able to group them into eight major categories: asymptomatic CCC or without left ventricular dysfunction, ambulatory cohorts of patients with CCC, arrhythmic CCC cohort without an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD), symptomatic CCC or with left ventricular dysfunction, CCC with an ICD, CCC with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), CCC with stable HF, and CCC with CHF. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine other determinants of mortality and sources of heterogeneity; these analyses included the AHA stages, NYHA class, population characteristics, and ejection fraction. Participant's mean age, the percentages of men vs. women, ejection fraction, and percentage of NYHA class I/II were included in our meta‐regression. Cumulative survival curves were estimated by applying the exponential survival method. Contour‐enhanced funnel plots were constructed to assess publication bias. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software, Version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). We also performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate changes in the pooled effect after excluding one of each study from the analysis.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

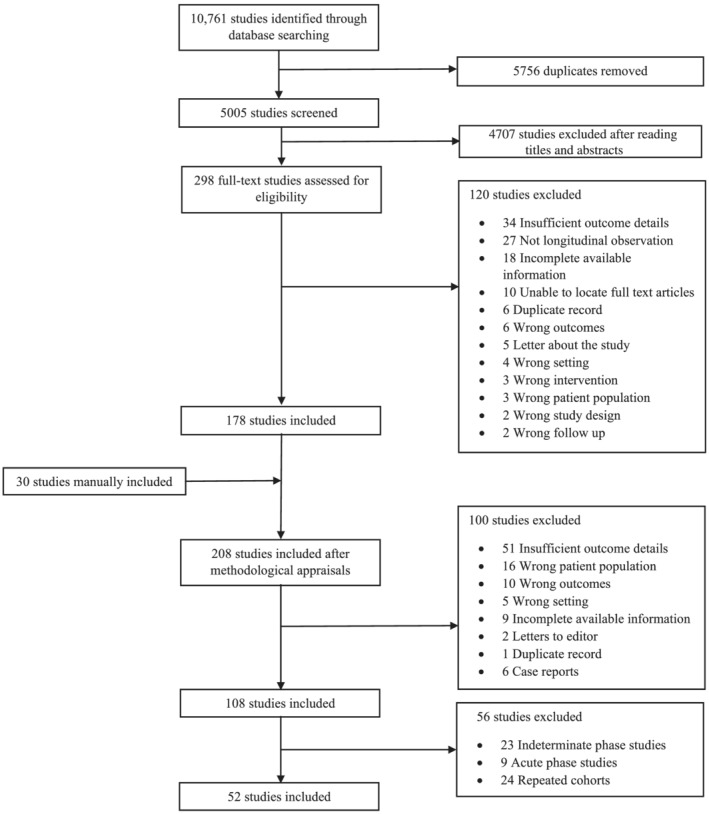

An initial 10 761 studies were identified through database searches. Upon deduplication, 5005 studies were screened for eligibility based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 298 full‐text articles were assessed, and 178 studies were considered for inclusion in the quantitative synthesis (Figure 1 ). After manually adding 30 articles, 208 studies were reviewed. A hundred and eight studies passed the initial methodological appraisal. In the final round of exclusions, 24 studies were removed because they originated from identical cohorts, and 32 studies because they included patients with a diagnosis of acute or indeterminate Chagas disease. A total of 52 longitudinal observational studies composed of 9569 patients diagnosed with CCC at the onset of observation and 2250 deaths during follow‐up were utilized for the meta‐analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy

Fifty‐two studies had longitudinal observation outcomes for patients with CCC. Most of these were prospective cohorts that originated in Brazil and enrolled patients between 1973 and 2015. Sample sizes varied from 15 to 2854 cases, with a mean of 184 participants per study. Gender distribution had a slight male predominance at 58% (50 studies). Mean ages ranged between 37.3 and 63.4 years, with an overall mean of 53.4 years (50 studies). Mean LVEFs ranged between 18.6% and 61.0% (41 studies), with an overall mean of 38.4%. A few studies had missing data for age and gender distribution, and 11 studies did not report the mean ejection fraction. The mean follow‐up duration of patients was 4.9 years, with a range of 0.74 to 10.1 years (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcome measures in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy

| Source | Study design | Country | Stage a | Cases | Males % | Age | EF (%) | NYHA I/II (%) | NYHA III/IV (%) | Population characteristics | Study duration (years) | All‐cause mortality (%) | Cardiac deaths (%) | Heart failure deaths (%) | Stroke deaths (%) | Sudden deaths (%) | Rate estimate b | 95% CI | % Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morillo et al. (2015) c , 9 | RCT | Multicentre d | B1/B2 | 2854 | 49 | 55.3 | 54.5 | 97.5 | 2.5 | Benznidazole vs. placebo | 5.4 | 503 (17.6) | 397 (13.9) | NA | NA | NA | 3.3 | 3.0–3.5 | 2.07 |

| Costa et al. (2019) 10 | Prospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 75 | 61 | 48.4 | 41 | 92 | 8 | Ability to perform ET | 3.4 | 12 (16.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.7 | 2.8–7.9 | 1.89 |

| Pedrosa et al. (2011) 11 | Prospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 130 | 41 | 50.7 | NA | NA | NA | Submitted to a cardiopulmonary ET | 9.9 | 38 (29.2) | 33 (25.4) | NA | NA | NA | 2.9 | 2.3–3.9 | 2.02 |

| Santos et al. (2012) 12 | RCT | Brazil | C/D | 183 | 69 | 52.4 | 26.1 | NA | NA | Steam cell therapy vs. placebo | 1 | 35 (19.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 19.1 | 14.2–25.8 | 2.01 |

| Nadruz et al. (2018) 13 | Prospective | Brazil | C | 159 | 61 | 55.8 | 31.8 | NA | NA | HF patients with EF ≤ 50% | 2 | 55 (34.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17.3 | 14.0–21.4 | 2.04 |

| Guajardo et al. (1984) 14 | Prospective | Chile | C | 54 | 43 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Symptomatic ambulatorial CCC cohort | 3 | 14 (25.9) | 11 (20.4) | 7 (13.0) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.6) | 8.6 | 5.5–13.6 | 1.93 |

| Duarte et al. (2011) 15 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 56 | 50 | 56 | 30 | 87 | 13 | CCC with EF < 45% | 1.8 | 11 (19.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.9 | 6.4–18.5 | 1.88 |

| Sarabanda et al. (2011) 16 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 56 | 55 | 55 | 42 | 98.2 | 1.8 | NSVT and VT not on ICD | 3.2 | 16 (28.6) | 16 (28.6) | 5 (8.9) | 0 | 11 (19.6) | 8.9 | 5.9–13.5 | 1.95 |

| Petti et al. (2008) 17 | Prospective | Argentina | B1/B2 | 95 | 61 | 54.7 | 44 | NA | NA | Asymptomatic LV dysfunction | 5.3 | 13 (13.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.6 | 1.6–4.3 | 1.9 |

| Peixoto et al. (2018) 18 | Prospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 396 | 36 | 62.5 | 49 | 94.9 | 5.1 | Pacemaker | 1.9 | 65 (16.4) | 46 (11.6) | 21 (5.3) | 2 (0.5) | 22 (5.6) | 8.6 | 6.9–10.8 | 2.04 |

| Theodoropoulos et al. (2008) 19 | Prospective | Brazil | C/D | 127 | 69 | 54 | 33 | NA | NA | CHF | 2.1 | 63 (49.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 23.6 | 19.8–28.1 | 2.05 |

| DiToro et al. (2011) 20 | Prospective | Multicentre e | B2/C | 148 | 73 | 60.1 | 40.1 | 77.7 | 22.3 | ICD placement | 1 | 15 (10.1) | 10 (6.8) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.7) | 10.1 | 6.3–16.4 | 1.91 |

| Silva et al. (2000) 21 | Prospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 78 | 58 | 46.4 | 47 | 84.6 | 15.4 | NSVT + EPS | 4.6 | 22 (28.2) | 20 (25.6) | NA | 1 (1.3) | 16 (20.5) | 6.1 | 4.3–8.7 | 1.98 |

| Ayub‐Ferreira et al. (2013) 22 | RCT | Brazil | C/D | 55 | 56 | 49 | 34 | 56.5 | 43.5 | Chronic HF | 3.5 | 31 (56.4) | 26 (47.3) | 15 (27.3) | 2 (3.6) | 8 (14.5) | 16.1 | 12.8–20.3 | 2.04 |

| Garcia et al. (2008) 23 | Prospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 612 | 45 | 48 | 56 | NA | NA | Ambulatorial CCC cohort | 5.6 | 91 (14.9) | 76 (12.4) | 21 (3.4) | 5 (0.8) | 50 (8.2) | 2.7 | 2.2–3.2 | 2.05 |

| Muratore et al. (2009) 24 | Prospective | Multicentre f | B1/B2/C | 89 | 88 | 59 | 40 | 71.9 | 28.1 | ICD placement | 1 | 6 (6.7) | 4 (4.5) | 3 (3.4) | NA | 1 (1.1) | 6.7 | 3.1–14.6 | 1.7 |

| Dietrich et al. (2013) 25 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 34 | 68 | 52.5 | 34.5 | 88.2 | 11.8 | Refractory SVT and catheter ablation | 1 | 3 (8.8) | 3 (8.8) | 3 (8.8) | 0 | 0 | 8.8 | 3.0–26 | 1.45 |

| Pereira et al. (2014) 26 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 65 | 68 | 56.7 | NA | 58.5 | 41.5 | ICD placement | 3.3 | 13 (20.6) | 10 (15.9) | 7 (11.1) | NA | 0 | 6.2 | 3.7–9.9 | 1.91 |

| Pavao et al. (2018) 27 | Retrospective | Brazil | B2/C | 111 | 68 | 60.4 | 41 | 81.4 | 18.6 | ICD placement | 5.3 | 50 (45.0) | 26 (23.4) | 21 (18.9) | NA | 5 (4.5) | 8.5 | 6.9–10.4 | 2.05 |

| Pimenta et al. (1999) 28 | Prospective | Brazil | B1 | 55 | 60 | 45.8 | NA | NA | 0 | Asymptomatic BBB + EPS | 10.1 | 20 (36.4) | 17 (30.9) | 6 (10.9) | 1 (1.8) | 10 (18.2) | 3.6 | 2.5–5.1 | 1.99 |

| Acquatella et al. (1987) 29 | Prospective | Venezuela | B2/C | 159 | NA | 56.3 | NA | NA | NA | Symptomatic CCC cohort | 2.3 | 45 (28.3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12.3 | 9.6–15.8 | 2.03 |

| Gali et al. (2014) g , 30 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 104 | 64 | 55.5 | 40 | 94.2 | 5.8 | SVT treated with ICD or amiodarone | 2.8 | 19 (18.3) | 15 (14.4) | 7 (6.7) | 0 | 8 (7.7) | 6.5 | 4.3–9.8 | 1.96 |

| Nunes et al. (2012) 31 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 232 | 62 | 48 | 35.7 | 74.6 | 25.4 | Chronic HF | 3.4 | 96 (41.4) | 96 (41.4) | NA | NA | NA | 12.2 | 10.4–14.2 | 2.06 |

| Rassi et al. (2006) 32 | Retrospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 424 | 58 | 47 | NA | 89.6 | 10.4 | Ambulatorial CCC cohort | 7.9 | 130 (30.7) | 113 (26.7) | 20 (4.7) | 12 (2.8) | 81 (19.1) | 3.9 | 3.4–4.5 | 2.06 |

| Barbosa et al. (2011) 33 | Retrospective | Brazil | C/D | 246 | 65 | 55 | 35.2 | 68.3 | 31.7 | Chronic HF | 2.3 | 119 (48.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21.0 | 18.5–23.9 | 2.06 |

| Martinelli Filho et al. (2018) 34 | Retrospective | Brazil | C/D | 115 | 65 | 56.7 | 25.5 | 15.7 | 84.3 | CHF + CRT | 2.4 | 70 (60.9) | 59 (51.3) | 51 (44.3) | NA | 2 (1.7) | 25.4 | 21.9–29.4 | 2.06 |

| Leite et al. (2003) 35 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 115 | 60 | 52.3 | 49 | 83.5 | 16.5 | Symptomatic spontaneous or inducible SVT + AA | 4.3 | 45 (39.1) | 38 (33.0) | NA | NA | 27 (23.5) | 9.1 | 7.2–11.4 | 2.04 |

| Hagar et al. (1991) 36 | Retrospective | USA | B1/B2/C | 25 | 28 | 53 | NA | NA | NA | CCC cohort in the USA | 4.4 | 8 (32.0) | 8 (32.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 | 6 (24.0) | 7.3 | 4.1–12.9 | 1.85 |

| Araujo et al. (2014) 37 | Retrospective | Brazil | C | 72 | NA | NA | 27.3 | 0 | 100 | CHF + CRT | 3.9 | 25 (34.7) | 19 (26.4) | 15 (20.8) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 8.9 | 6.5–12.2 | 2 |

| Menezes Jr. et al. (2018) 38 | Retrospective | Brazil | C | 50 | 56 | 63.4 | 29 | 18 | 82 | CHF + CRT | 5.1 | 25 (50.0) | 18 (36.0) | NA | NA | NA | 9.8 | 7.4–12.9 | 2.02 |

| Benchimol‐Barbosa (2007) h , 39 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 36 | 28 | 50.7 | NA | NA | NA | CCC + LV dysfunction | 7 | 9 (25.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.6 | 2.0–6.3 | 1.86 |

| Bocchi et al. (2018) i , 40 | RCT | Multicentre j | C | 38 | 68 | 60 | 27.5 | 78.9 | 21.1 | Chronic stable HF: ivabradine vs. placebo | 1.1 | 16 (42.1) | 14 (36.8) | 9 (23.7) | NA | 3 (7.9) | 38.3 | 26.4–55.6 | 1.98 |

| Cardinalli‐Neto et al. (2007) 41 | Retrospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 90 | 68 | 59 | 47 | NA | NA | ICD placement | 2.1 | 31 (34.4) | 31 (34.4) | 24 (26.7) | NA | 2 (2.2) | 16.4 | 12.3–21.8 | 2.02 |

| Cardinalli‐Neto et al. (2011) 42 | Retrospective | Brazil | B2/C | 19 | 63 | 57 | 18.6 | 100 | 0 | ICD placement + CHF | 0.8 | 2 (10.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13.1 | 3.5–48.8 | 1.27 |

| Cardoso et al. (2010) 43 | Prospective | Brazil | C/D | 33 | 55 | 52.9 | 20.8 | 0 | 100 | Decompensated HF ‐ NYHA IV | 2.1 | 22 (66.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31.8 | 24.9–40.4 | 2.03 |

| Carrasco et al. (1994) k , 44 | Prospective | Venezuela | B2/C | 289 | 60 | 56.5 | NA | NA | NA | CCC cohort | 4.4 | 104 (36.0) | 97 (33.6) | 58 (20.1) | 13 (4.5) | 26 (9.0) | 8.2 | 7.0–9.5 | 2.06 |

| Da Fonseca et al. (2006) 45 | Retrospective | Brazil | Unknown | 18 | 33 | 37.3 | NA | NA | NA | ICD placement | 3.3 | 4 (22.2) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 6.7 | 2.8–16 | 1.63 |

| De Souza et al. (2015) 46 | Retrospective | Brazil | B1/B2 | 373 | 44 | 47 | 61 | NA | NA | Ambulatorial CCC cohort | 5.5 | 72 (19.3) | 61 (16.4) | 15 (4) | 3 (0.8) | 43 (11.5) | 3.5 | 2.9–4.3 | 2.04 |

| Flores‐Ocampo et al. (2009) 47 | Retrospective | Mexico | B2/C | 21 | 62 | 61 | 30 | 66.7 | 33.3 | ICD placement | 2.4 | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 9.9 | 4.6–21.3 | 1.71 |

| Garillo et al. (2004) 48 | Prospective | Multicentre l | B2/C | 230 | 58 | 63.4 | 37.4 | 81.2 | 18.8 | ICD placement | 2.5 | 43 (18.7) | 29 (12.6) | NA | 0 | 17 (7.4) | 7.5 | 5.7–9.8 | 2.02 |

| Heringer‐Walther et al. (2006) 49 | Prospective | Brazil | C | 32 | 41 | 50.7 | 31.3 | 56.3 | 43.7 | Chronic HF | 2.6 | 8 (25.0) | 8 (25.0) | 8 (25.0) | 0 | 0 | 9.6 | 5.3–17.5 | 1.83 |

| Mady et al. (1994) 50 | Prospective | Brazil | C | 104 | 100 | 40.3 | 37.4 | 29.8 | 70.2 | Chronic HF | 2.5 | 50 (48.1) | 50 (48.1) | 18 (17.3) | 0 | 32 (30.8) | 19.2 | 15.8–23.5 | 2.05 |

| Mendoza et al. (1986) 51 | Prospective | Venezuela | B1/B2 | 15 | 67 | 47.9 | 56 | 93.3 | 6.7 | SVT + EPS | 1.8 | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | NA | NA | 2 (13.3) | 11.1 | 4.0–30.6 | 1.5 |

| Nunes et al. (2008) 52 | Prospective | Brazil | B2/C | 158 | 63 | 48.5 | 36.9 | 79.1 | 20.9 | Tertiary centre CCC cohort | 2.8 | 44 (27.8) | 43 (27.2) | 24 (15.2) | 3 (1.9) | 16 (10.1) | 9.9 | 7.7–12.8 | 2.03 |

| Senra et al. (2018) 53 | Retrospective | Brazil | B1/B2/C | 130 | 46 | 53.6 | 43.3 | 89.2 | 10.8 | CCC cohort + CMR | 5.4 | 45 (34.6) | 28 (21.5) | 23 (17.7) | NA | 1 (0.8) | 6.4 | 5.1–8.1 | 2.04 |

| Shen et al. (2017) 54 | Prospective | Multicentre m | C | 195 | 66 | 59.6 | 28.5 | 93.3 | 6.7 | Chronic HF PARADIGM‐HF/ATMOSPHERE | 2.2 | 57 (29.2) | 46 (23.6) | 16 (8.2) | NA | 14 (7.2) | 13.3 | 10.7–16.5 | 2.04 |

| Silva et al. (2015) 55 | Prospective | Brazil | B1 | 165 | 38 | 44.8 | NA | NA | NA | CCC with normal LV function | 8.2 | 7 (4.2) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 0.5 | 0.3–1.1 | 1.74 |

| De Melo et al. (2019) 56 | Retrospective | Brazil | B2/C | 52 | 62 | 59.2 | 34.1 | 75 | 25 | ICD placement + HF | 1.3 | 11 (21.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16.3 | 9.6–27.5 | 1.88 |

| Viotti et al. (2004) n , 57 | Prospective | Argentina | B1 | 344 | NA | 48.6 | 60 | NA | NA | CCC without HF | 10 | 16 (4.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.5 | 0.3–0.8 | 1.91 |

| Femenia et al. (2012) 58 | Retrospective | Argentina | B2/C | 72 | 63 | 53.3 | 41.1 | 70.9 | 29.1 | ICD placement | 4.2 | 4 (5.6) | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1.3 | 0.5–3.4 | 1.55 |

| Martinelli Filho et al. (2012) 59 | Retrospective | Brazil | B2/C | 116 | 63 | 54 | 42.4 | 82.8 | 17.2 | ICD placement | 3.8 | 31 (26.7) | 14 (12.1) | 14 (12.1) | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 5.2–9.5 | 2.01 |

| Barbosa et al. (2013) 60 | Retrospective | Brazil | B2/C | 65 | 70 | 59 | 37 | 76.9 | 23.1 | ICD placement | 0.74 | 8 (12.3) | 4 (6.2) | 2 (3.1) | 0 | 2 (3.1) | 16.6 | 8.7–31.8 | 1.8 |

AA, antiarrhythmics; ATMOSPHERE, Aliskiren Trial to Minimize Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure; BBB, bundle branch block; CCC, chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy; CHF, congestive heart failure; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; EF, ejection fraction; EPS, electrophysiologic study; ET, exercise testing; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; NA, not available; NSVT, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PARADIGM‐HF, Prospective Comparison of ARNI [Angiotensin Receptor–Neprilysin Inhibitor] with ACEI [Angiotensin‐Converting–Enzyme Inhibitor] to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SVT, sustained ventricular tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Predominant or exclusive stage based on severity of involvement according to American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines. 5

Estimated rate calculated by per cent all‐cause mortality divided by the study duration.

Dual arm study: (i) Benznidazole (1431 patients)—726 males, 246 all‐cause mortality, and 194 cardiac deaths; (ii) placebo (1423 patients)—682 males, 257 all‐cause mortality, and 203 cardiac deaths.

Centres included El Salvador, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Colombia.

Centres included Mexico, South America, Puerto Rico, and Caribbean.

Centres included South America, Caribbean, Mexico, and Puerto Rico.

Dual arm study: (i) ICD (76 patients)—48 males, 33 months of follow‐up, 10 all‐cause mortality, 1 sudden death, 5 heart failure deaths, and 3 noncardiac deaths (2 pneumonias and 1 abdominal sepsis); (ii) controls (28 patients)—18 males, 35 months of follow‐up, 9 all‐cause mortality, 7 sudden deaths, and 2 heart failure deaths.

Dual arm study: (i) Los Andes class II (24 patients)—5 males and 1 all‐cause mortality; (ii) Los Andes class III (12 patients)—5 males and 8 all‐cause mortality.

Dual arm study: (i) Ivabradine (20 patients)—13 males, 7 all‐cause mortality, 4 heart failure deaths, 2 sudden deaths, and 1 noncardiac death; (ii) placebo (18 patients)—13 males, 9 all‐cause mortality, 5 heart failure deaths, 1 sudden death, 2 other cardiac deaths, and 1 noncardiac death.

Centres included Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.

Dual arm study: (i) Los Andes class II (185 patients)—105 males, 77 months of follow‐up, 36 all‐cause mortality, 12 sudden deaths, 12 stroke deaths, 6 heart failure deaths, 3 pulmonary thromboembolism deaths, and 3 noncardiac deaths; (ii) Los Andes class III (104 patients)—67 males, 28 months of follow‐up, 68 all‐cause mortality, 52 heart failure deaths, 14 sudden deaths, 1 stroke death, and 1 noncardiac death.

Centres included Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela, Chile, and Cuba.

Centres included Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia.

Dual arm study: (i) Kuschnir class 1 (257 patients)—10.7 years of follow‐up, 4 all‐cause mortality; (ii) Kuschnir class 2 (87 patients)—9.4 years of follow‐up, 12 all‐cause mortality.

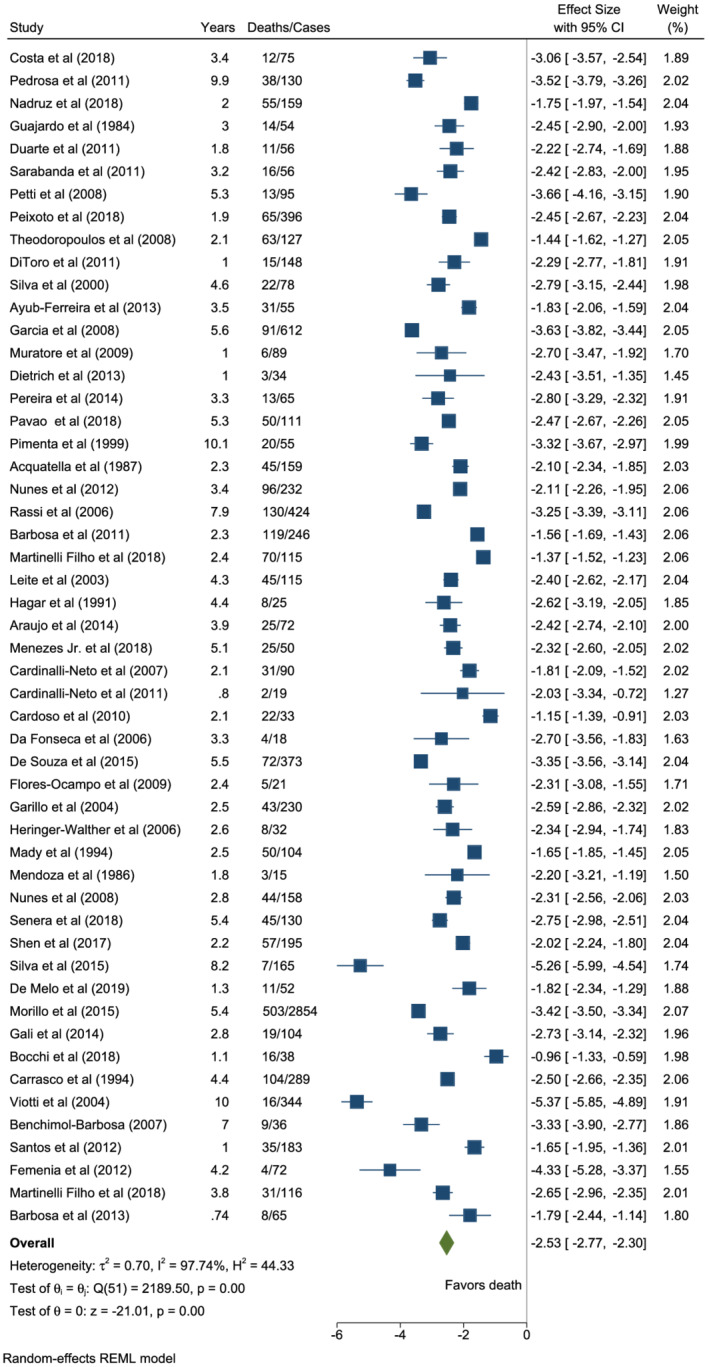

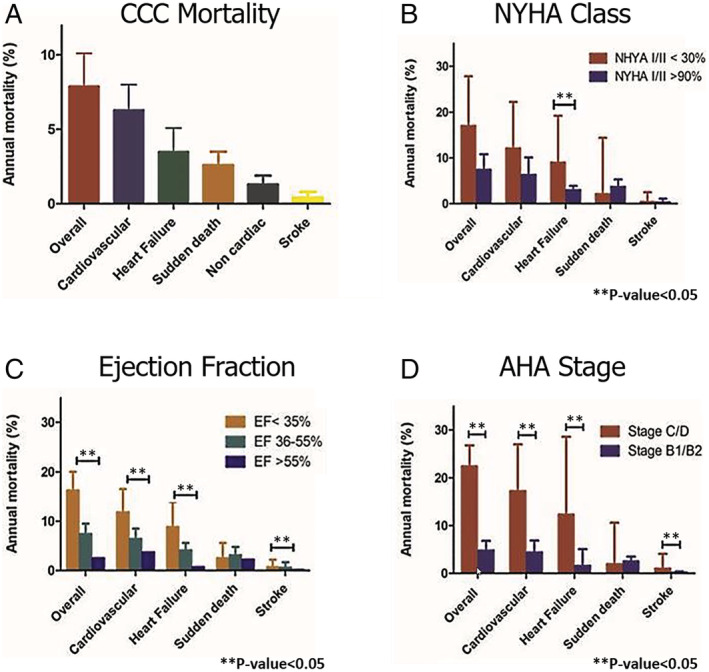

All‐cause mortality

Fifty‐two studies had observational outcomes for all‐cause mortality among patients with CCC. The pooled estimated annual all‐cause mortality rate was 7.9% [95% confidence interval (CI): 6.3–10.1; I 2 = 97.74%; T 2 = 0.70] [Figures 2 and 3 (A) ]. The I 2 variable suggested significant heterogeneity among these studies, lower among studies reporting stroke deaths (I 2 = 97.74% vs. 63.84%) (Figure 2 , Supporting Information, Figure S5 ). Cumulative death probability was approximately 37% at 5 years, 59% at 10 years, and 75% at 15 years (Supporting Information, Figure S1 ).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of all‐cause mortality in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of mortality in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy bar graph. [Correction added on 05 November 2021, after first online publication: The panel labels of Figure 3 have been added in this version.]

Meta‐regression analysis showed low LVEF (coefficient = −0.04; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.02; P = 0.001) to be associated with an increase in mortality risk (Supporting Information, Table S1 ). Subgroup analysis indicated no statistical mortality difference among studies with less than 30% of patients staged as NYHA I/II compared with those with greater than 90% (17% vs. 7.4%, P = 0.069) [Figure 3 (B) ]. CCC staged as C/D had a notably higher mortality risk than stage B1/B2 (22.4% vs. 4.8%, P = 0.0001) [Figure 3 (D) ]. Pooled estimated annual rates revealed an incremental progression of 1%, 4.8%, 6.5%, 8.7%, 13.9%, and 22.4% for AHA stages B1, B1/B2, B1/B2/C, B2/C, C, and C/D (Supporting Information, Table S2 ). These high mortality rates among severely ill patients with advanced disease progression were further supported by the observed increased mortality based on the global ventricular dysfunction by the ejection fraction < 35% vs. >55% (16.2% vs. 2.5%; P = 0.0001) [Figure 3 (C) , Supporting Information, Table S2 ]. Of note, studies of patients with CCC with either congestive or stable HF presented with significant all‐cause AMRs (27.1% and 17.1%) compared with studies with an ambulatory pool of patients or asymptomatic cohorts/without left ventricular dysfunction (3.3% and 1.8%; P = 0.0001) (Supporting Information, Figure S2 and Table S2 ).

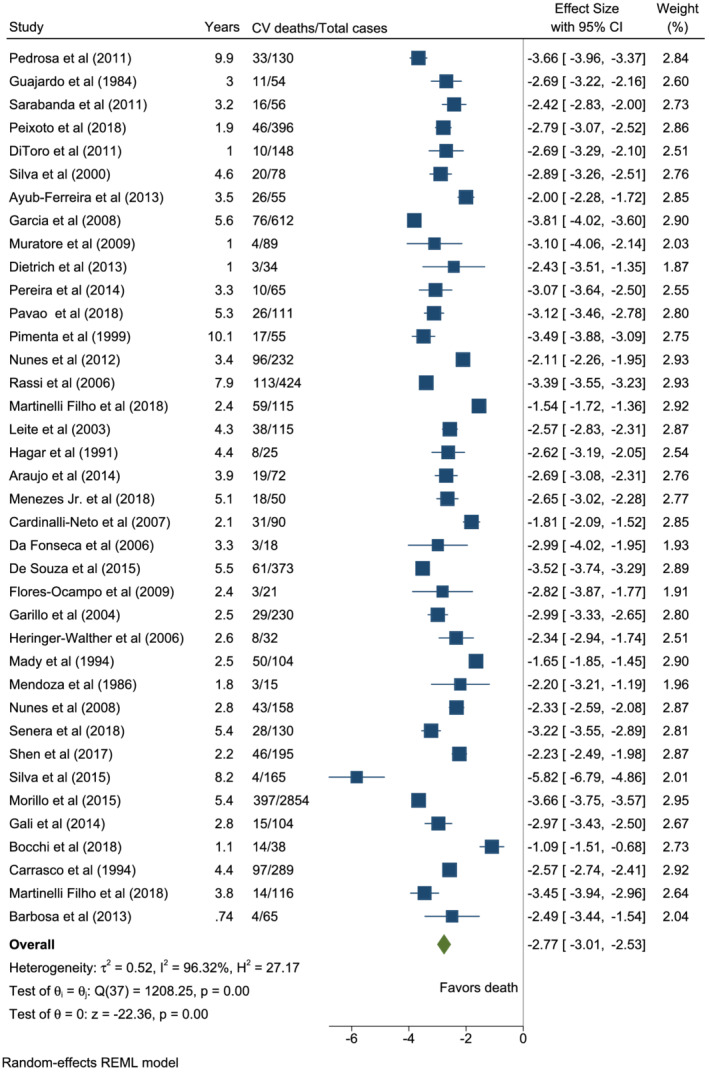

Cardiovascular mortality

Thirty‐eight studies had observational outcomes for CV‐related deaths among patients with CCC. The pooled estimated annual CV mortality rate was 6.3% (95% CI: 4.9–8.0; I 2 = 96.32%; T 2 = 0.52) [Figures 3 (A) and 4 ]. Further breakdown of CV deaths revealed that HF deaths held a 3.5% annual risk (95% CI: 2.4–5.1; I 2 = 94.10%; T 2 = 0.93; 30 studies), SCDs carried a 2.6% risk (95% CI: 1.9–3.5; I 2 = 89.72%; T 2 = 0.53; 28 studies), and stroke deaths constituted a 0.4% annual risk (95% CI: 0.3–0.8; I 2 = 63.84%; T 2 = 0.49; 12 studies) [Figure 3 (A) , Supporting Information, Figures S3 – S5 ]. The cumulative probability of CV mortality was approximately 32% at 5 years, 55% at 10 years, and 70% at 15 years (Supporting Information, Figure S6 ).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy.

Meta‐regression findings of CV deaths coincided with those of all‐cause mortality and showed low LVEF (coefficient = −0.05; 95% CI: −0.08, −0.02; P < 0.001) associated with an increase in mortality risk. Age appeared to also inversely correlate with CV mortality (coefficient = −0.03; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.002; P = 0.04), indicating that younger patients exhibited more CV mortality when adjusted by gender, ejection fraction, and proportion of NYHA I/II class (Supporting Information, Table S1 ).

Patients staged C/D had a considerably higher CV and HF mortality risk than those staged B1/B2 (17.2% vs. 4.4%; and 12.3% vs. 1.6%) [Figure 3 (D) , Supporting Information, Table S2 ]. Studies with CCC and HF or CRT exhibited the highest annual CV and HF mortality rates (Supporting Information, Figure S2 and Table S2 ). Pooled estimated annual rates of 4.4%, 4.9%, 6.7%, 11.3%, and 17.2% (P < 0.01) were noted for stages B1/B2, B1/B2/C, B2/C, C, and C/D, respectively (Supporting Information, Table S2 ). Patients with LVEF < 35% also had a greater risk than those with normal ejection fraction (>55%) (11.8% vs. 3.7%, P = 0.004) [Figure 3 (C) , Supporting Information, Table S2 ]. The estimated annual CV death rate decreases as the ejection fraction increases (Bubble plot, Supporting Information, Figure S7 ). Regarding the mode of death (annual rate of SCD vs. the annual rate of HF death), the first was higher in asymptomatic CCC or without left ventricular dysfunction (0.6% vs. 0.4%), ambulatory cohorts of patients with CCC (2.0% vs. 0.6%), and arrhythmic CCC cohort without an ICD (5.3% vs. 4.7%). In comparison, there was a higher annual rate of HF deaths in symptomatic CCC or with left ventricular dysfunction (4.3% vs. 1.9%), CCC with an ICD (4.4% vs. 2.0%), CCC with a CRT (10.1% vs. 0.7%), and CCC with stable HF (8.2% vs. 6.0%) (Supporting Information, Figure S2 and Table S2 ).

Noncardiac mortality

Nineteen studies had observational outcomes for noncardiac mortality among patients with CCC. The pooled estimated annual noncardiac mortality rate was 1.3% (95% CI: 0.9–1.9; I 2 = 75.06%; T 2 = 0.45) [Figure 3 (A) , Supporting Information, Figure S8 ].

Sensitivity analysis of the overall and CV mortality, excluding each study, did not significantly change the overall annual rates. The recalculated overall mortality rate range was 7.7–8.4% and 6.0–6.5% for the CV rate. There was also no significant change in heterogeneity. Furthermore, overall and CV mortality mean effect sizes did not change after decreasing the variance to 0.25. The rates also remained the same, assuming an I 2 of 10%. A funnel plot for publication bias indicated missing studies in the bottom left‐hand and right‐hand side of the plot, suggesting asymmetry among smaller studies (Supporting Information, Figure S9 ).

Discussion

Cardiac morbidity and mortality due to Chagas disease remain substantial in Latin America. Compared with cardiomyopathy of other causes, this largely neglected tropical disease continues to account for a staggering record high AMR of 7.9%. We found a yearly CV mortality rate of 6.3% and a yearly non‐CV mortality rate of 1.3%. We also found that the annual HF death rate was 3.5%, the SCD rate was 2.6%, and strokes carried a 0.4% yearly mortality risk. Although CV deaths are the principal cause of death in CCC, the predominant mode of death (HF or SCD) is still debated. Our review showed that the mode of death is conditioned by the characteristics of the studied populations. While the sudden annual death rates were higher than the HF rates in studies that included (i) ambulatory asymptomatic patients, (ii) patients without ventricular dysfunction, (iii) patients predominantly in NYHA class I/II, and (iv) patients with documented ventricular arrhythmias, not treated with an ICD, the contrary was observed in cohorts of patients (i) with symptomatic CCC, (ii) with left ventricular dysfunction or HF, and (iii) with an implanted ICD or CRT.

There was a proportional increase in mortality with increasing severity of the disease. The analysis revealed worse prognosis and higher mortality rates among studies with patients with advanced cardiomyopathy—staged as C/D and/or NYHA class III/IV—and patients with lower LVEF.

Assessing CCC clinical outcomes has been challenging due to the heterogeneity in studies related to study design, sample size, stage of the disease being studied, and characteristics of the population. We sought to alleviate some of the differences by adjusting mortality rates based on causality and staging. Our findings help explain the results of prior studies and reviews.

Several RCTs in the past decade, including the BENEFIT (2854 patients with CCC), a subanalysis of the PARADIGM/ATMOSPHERE, and SHIFT trials (very few patients with CCC), reported an all‐cause AMR of 3.3%, 13.3%, and 38.3%, respectively. 9 , 40 , 54 The pooled PARADIGM/ATMOSPHERE trial demonstrated a CV AMR of 10.7% compared with 2.6% in the BENEFIT trial. The lower rates seen may directly result from the patient's disease severity. The BENEFIT trial classified three‐quarters of patients as NYHA class I and had a mean LVEF ~ 54.5%. This meta‐analysis consisted mainly of patients staged B2/C or higher, with an ICD, or stable HF with LVEF ≤ 45% (mean ~ 38%). In contrast, the high AMR demonstrated in the SHIFT trial may be accounted for by the small cohort comprised only of NYHA class II/III patients with severely depressed LVEF ~ 27.5%.

Despite the wide fluctuance of AMRs, cardiomyopathy in advanced stages and low LVEF are consistently associated with increased mortality. For example, cohorts described by Benchimol‐Barbosa, Araujo et al., and Martinelli Filho et al. revealed a broad range of all‐cause AMRs of 3.6%, 9.1%, and 25.4%, respectively. 34 , 37 , 39 Similar to the RCTs, these studies had differences in NYHA functional classification and LVEF, accounting for variations in mortality rates.

The mortality attributable to Chagas cardiomyopathy surpasses that of other common forms of cardiomyopathy in South America. Shen et al. reported an annual all‐cause and CV mortality rate of 10.3% and 8.1% among the ischaemic cardiomyopathy pool vs. 13.3% and 10.7% for patients with CCC. 54 In another seminal study, Martinelli Filho et al. showed annual all‐cause death rates of 10.4%, 11.3%, and 25.4% among dilated, ischaemic, and Chagas cardiomyopathy patient pools who underwent CRT. 34 The biological basis for these differences in outcome remains poorly understood and potentially driven by repetitive cardiac insults from re‐infections, cumulative effects of autonomic nervous system derangements and microvascular disturbances, as well as an increased frequency of ventricular arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, right ventricular dysfunction, and thromboembolic events. In addition, patients with CCC face significant socio‐economic barriers to care that limit early diagnosis and access to medical treatment and specialized cardiac interventions. Compared with other major drivers of worldwide mortality, CCC annual mortality is higher than those for AIDS and similar to leukaemia. 61

We found higher annual rates of HF deaths among patients with more advanced cardiomyopathy. In contrast, the annual rates of SCD were non‐statistically significant among some subgroups, that is, regardless of the AHA stage, LVEF, or NYHA class. Of note, there was a trend to higher SCD AMRs among patients with cardiomyopathy in the early stages. In some registries, ICDs have been shown to be an effective prevention tool against life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with CCC. 24 The higher SCD mortality rate in this patient population may be related to the underappreciation of CCC in early stages as a highly arrhythmogenic condition or to limited access to specialized cardiac treatment interventions such as placement of an ICD. In our meta‐analysis, the all‐cause AMR for patients treated with an ICD was 8.7%, while for those treated with CRT was 13.2%. However, longitudinal studies are not the best tools to study the impact of treatments. Advanced therapies for CCC are usually associated with a worse prognosis because they are applied to patients with more severe diseases. The role of ICD and other therapies should be evaluated in an RCT.

The mortality risk substantially increases with worsening progression to more severe cardiomyopathy. The BENEFIT trial investigators also demonstrated that antiparasitic treatment did not halt cardiac progression, although the generalizability of the findings is controversial. 9 The risk of cardiomyopathy development is 1.9% every year among patients with the chronic indeterminate form and 4.6% among those diagnosed with acute infection. 4 Although antiparasitic treatment efficacy on Chagas cardiomyopathy progression has shown mixed results and lacks more validated RCT data, more recent observational studies showed benznidazole decreases the risk of progression. 62 However, the effectiveness of antiparasitic treatment in CCC is not clear. Physicians must therefore remain cognizant of the potential consequences of deferring early treatment during the indeterminate chronic form or early cardiomyopathy. Public health policies should be redirected to the development and implementation of novel integrated preventive measures in endemic regions and increase awareness of this treatable condition in non‐endemic regions.

Limitations

Potential limitations of this study may be attributed to the large number of longitudinal observational studies utilized. These studies varied in sample size, study design, epidemiologic settings, population characteristics, disease stages, and follow‐up durations, translating to high heterogeneity. Not all studies consistently reported data on some important variables such as gender, mean age, mean LVEF, and NYHA functional class. Although information about total mortality was a prerequisite for inclusion in this meta‐analysis, the studies grouped to estimate annual rates of the specific modes of deaths were not the same due to missing information in some studies. Progression to mortality was also non‐linear, as we assumed for this type of analysis. The classification of CCC into the predominant stages (B1, B2, C, and D, or a combination of them) was reported in only one study. In the others, we used the characteristics of the population to extrapolate this information, which might have introduced information bias into our results. The same was true for the eight clinical subgroups of patients with CCC we have chosen to meta‐analyse studies of similar characteristics. Many of the studies were performed in Brazil and other Latin American countries where access to advanced care is not similar to those of the USA or Western Europe. However, this is the most complete review, including all manuscripts in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. The funnel plot for publication bias is often more liberal and gives more weightage to smaller studies. Some causes may be plausible contributors to low methodological quality among these studies resulting in asymmetry. 63

Conclusions

The findings from this study highlight the insurmountable disease burden of many patients living with Chagas disease in the endemic regions. The management of established Chagas cardiomyopathy requires advanced medical tools and, for selected patients, cost‐prohibitive interventions, procedures, and devices. As this neglected tropical disease affects the most disadvantaged populations, many potential life‐saving interventions at later disease stages are out of reach. Public health policies and advocacy should centre on disease prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Dr. Sillau reported receiving grants from the Alzheimer's Association, the Benign Essential Blepharospasm Research Foundation, the Colorado Department of Public Health, the Davis Phinney Foundation, the Hewitt Family Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the Rocky Mountain Alzheimer's Disease Center outside the submitted work. Dr. Henao‐Martínez reported being the recipient of a K12‐clinical trial award as a co‐principal investigator for the Expanded Access IND Program (EAP) to provide the Yellow Fever vaccine (Stamaril) to Persons in the United States outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Cumulative Risk of All‐Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S2. Subgroup Analysis of Population Characteristics in Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy Bar Graph.

Figure S3. Forest Plot of Heart Failure Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S4. Forest Plot of Sudden Death Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S5. Forest Plot of Stroke Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S6. Cumulative Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S7. Bubble Plot of Cardiovascular Mortality in Relation to Ejection Fraction.

Figure S8. Forest Plot of Non‐cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S9. Funnel Plot for Publication Bias.

Table S1. Meta‐regression Analysis of Mortality of Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Table S2. Subgroup Analysis of Mortality and Population Characteristics in Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgements

No funding agencies had any role in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

Chadalawada, S. , Rassi, A. Jr , Samara, O. , Monzon, A. , Gudapati, D. , Vargas Barahona, L. , Hyson, P. , Sillau, S. , Mestroni, L. , Taylor, M. , da Consolação Vieira Moreira, M. , DeSanto, K. , Agudelo Higuita, N. I. , Franco‐Paredes, C. , and Henao‐Martínez, A. F. (2021) Mortality risk in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 5466–5481. 10.1002/ehf2.13648.

References

- 1. PAHO . Strategy and Plan of Action for Chagas Disease Prevention, Control and Care. 2010. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/cd5016‐strategy‐and‐plan‐action‐chagas‐disease‐prevention‐control‐and‐care‐2010

- 2. Manne‐Goehler J, Umeh CA, Montgomery SP, Wirtz VJ. Estimating the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10: e0005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strasen J, Williams T, Ertl G, Zoller T, Stich A, Ritter O. Epidemiology of Chagas disease in Europe: many calculations, little knowledge. Clin Res Cardiol 2014; 103: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chadalawada S, Sillau S, Archuleta S, Mundo W, Bandali M, Parra‐Henao G, Rodriguez‐Morales AJ, Villamil‐Gomez WE, Suárez JA, Shapiro L, Hotez PJ, Woc‐Colburn L, DeSanto K, Rassi A Jr, Franco‐Paredes C, Henao‐Martínez AF. Risk of chronic cardiomyopathy among patients with the acute phase or indeterminate form of Chagas disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Network Open 2020; 3: e2015072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nunes MCP, Beaton A, Acquatella H, Bern C, Bolger AF, Echeverría LE, Dutra WO, Gascon J, Morillo CA, Oliveira‐Filho J, Ribeiro ALP, Marin‐Neto JA. Chagas cardiomyopathy: an update of current clinical knowledge and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 138: e169–e209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin‐Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet 2010; 375: 1388–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cucunubá ZM, Okuwoga O, Basáñez M‐G, Nouvellet P. Increased mortality attributed to Chagas disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aromataris E MZ. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Joanna+Briggs+Institute+Reviewer%27s+Manual

- 9. Morillo CA, Marin‐Neto JA, Avezum A, Sosa‐Estani S, Rassi A Jr, Rosas F, Villena E, Quiroz R, Bonilla R, Britto C, Guhl F, Velazquez E, Bonilla L, Meeks B, Rao‐Melacini P, Pogue J, Mattos A, Lazdins J, Rassi A, Connolly SJ, Yusuf S, Benefit I. Randomized trial of benznidazole for chronic Chagas' cardiomyopathy. New Eng J Med 2015; 373: 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costa HS, Lima MMO, Figueiredo PHS, Chaves AT, Nunes MCP, da Costa Rocha MO. The prognostic value of health‐related quality of life in patients with Chagas heart disease. Qual Life Res 2019; 28: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pedrosa RC, Salles JHG, Magnanini MMF, Bezerra DC, Bloch KV. Prognostic value of exercise‐induced ventricular arrhythmia in Chagas' heart disease. PACE ‐ Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34: 1492–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ribeiro Dos Santos R, Rassi S, Feitosa G, Grecco OT, Rassi A Jr, da Cunha AB, de Carvalho VB, Guarita‐Souza LC, de Oliveira W Jr, Tura BR, Soares MB, Campos de Carvalho AC. Cell therapy in Chagas cardiomyopathy (Chagas arm of the multicenter randomized trial of cell therapy in cardiopathies study): a multicenter randomized trial. Circulation 2012; 125: 2454–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nadruz W, Gioli‐Pereira L, Bernardez‐Pereira S, Marcondes‐Braga FG, Fernandes‐Silva MM, Silvestre OM, Sposito AC, Ribeiro AL, Bacal F, Fernandes F, Krieger JE, Mansur AJ, Pereira AC. Temporal trends in the contribution of Chagas cardiomyopathy to mortality among patients with heart failure. Heart 2018; 104:1522–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guajardo U, Beroiza AM, Saavedra C. Survival and clinical characteristics of Chagas' cardiopathy. Follow‐up of 54 cases. Rev Med Chile 1984; 112: 1119–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duarte Jde O, Magalhaes LP, Santana OO, Silva LB, Simoes M, Azevedo DO, Barbosa Junior OA, Fagundes AA, Reis FJ, Correia LC. Prevalence and prognostic value of ventricular dyssynchrony in Chagas cardiomyopathy. Arq Bras Cardiol 2011; 96: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sarabanda AV, Marin‐Neto JA. Predictors of mortality in patients with Chagas' cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia not treated with implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petti MA, Viotti R, Armenti A, Bertocchi G, Lococo B, Alvarez MG, Vigliano C. Predictors of heart failure in chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Rev Esp Cardiol 2008; 61: 116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peixoto GL, Martinelli Filho M, Siqueira SF, Nishioka SAD, Pedrosa AAA, Teixeira RA, Costa R, Kalil Filho R, Ramires JAF. Predictors of death in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy patients with pacemaker. Int J Cardiol 2018; 250: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Theodoropoulos TAD, Bestetti RB, Otaviano AP, Cordeiro JA, Rodrigues VC, Silva AC. Predictors of all‐cause mortality in chronic Chagas' heart disease in the current era of heart failure therapy. Int J Cardiol 2008; 128: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. di Toro D, Muratore C, Aguinaga L, Batista L, Malan A, Greco O, Benchetrit C, Duque M, Baranchuk A, Maloney J. Predictors of all‐cause 1‐year mortality in implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients with chronic Chagas' cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34: 1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silva RM, Tavora MZ, Gondim FA, Metha N, Hara VM, Paola AA. Predictive value of clinical and electrophysiological variables in patients with chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Arq Bras Cardiol 2000; 75: 33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ayub‐Ferreira SM, Mangini S, Issa VS, Cruz FD, Bacal F, Guimaraes GV, Chizzola PR, Conceicao‐Souza GE, Marcondes‐Braga FG, Bocchi EA. Mode of death on Chagas heart disease: comparison with other etiologies. A subanalysis of the REMADHE prospective trial. PLoS Neglected Tropical Dis [electronic resource] 2013; 7: e2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garcia MI, Sousa AS, Holanda MT, Haffner PMA, PEAAd B, Hasslocher‐Moreno A, Xavier SS. O valor prognóstico da largura do QRS nos pacientes com cardiopatias chagásica crônica. Rev SOCERJ 2008; 21: 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muratore CA, Batista Sa LA, Chiale PA, Eloy R, Tentori MC, Escudero J, Lima AM, Medina LE, Garillo R, Maloney J. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators and Chagas' disease: results of the ICD Registry Latin America. Europace 2009; 11: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dietrich CO, Henz BD, Dalegrave C, Backes LM, Costa GDF, Cirenza C, Paola AAV. Mapeamento endocárdico e epicárdico para a ablação do substrato arritmogênico de pacientes com cardiomiopatia chagásica e taquicardia ventricular refratária ao tratamento farmacológico. RELAMPA, Rev Lat‐Am Marcapasso Arritm 2013; 26: 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pereira FT, Rocha EA, Monteiro Mde P, Neto AC, Daher Ede F, Sobrinho CR, Pires Neto RDJ. Long‐term follow‐up of patients with chronic Chagas disease and implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37: 751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pavão MLRC, Arfelli E, Scorzoni‐Filho A, Rassi A, Pazin‐Filho A, Pavão RB, Marin‐Neto JA, Schmidt A. Long‐term follow‐up of Chagas heart disease patients receiving an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator for secondary prevention. PACE ‐ Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018; 41: 583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pimenta J, Valente N, Miranda M. Long‐term follow up of asymptomatic chagasic individuals with intraventricular conduction disturbances, correlating with non‐chagasic patients. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 1999; 32: 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Acquatella H, Catalioti F, Gomez‐Mancebo JR, Davalos V, Villalobos L. Long‐term control of Chagas disease in Venezuela: effects on serologic findings, electrocardiographic abnormalities, and clinical outcome. Circulation 1987; 76: 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gali WL, Sarabanda AV, Baggio JM, Ferreira LG, Gomes GG, Marin‐Neto JA, Junqueira LF. Implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators for treatment of sustained ventricular arrhythmias in patients with Chagas' heart disease: comparison with a control group treated with amiodarone alone. Europace 2014; 16: 674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nunes MP, Colosimo EA, Reis RC, Barbosa MM, da Silva JL, Barbosa F, Botoni FA, Ribeiro AL, Rocha MO. Different prognostic impact of the tissue Doppler‐derived E/e' ratio on mortality in Chagas cardiomyopathy patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012; 31: 634–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Little WC, Xavier SS, Rassi SG, Rassi AG, Rassi GG, Hasslocher‐Moreno A, Sousa AS, Scanavacca MI. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting death in Chagas' heart disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barbosa AP, Cardinalli‐Neto A, Otaviano AP, da Rocha BF, Bestetti RB. Comparison of outcome between Chagas cardiomyopathy and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Arq Bras Cardiol 2011; 97: 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martinelli Filho M, de Lima PG, de Siqueira SF, Martins SAM, Nishioka SAD, Pedrosa AAA, Teixeira RA, Dos Santos JX, Costa R, Kalil Filho R, Ramires JAF. A cohort study of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. Europace 2018; 20: 1813–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leite LR, Fenelon G, Simoes A Jr, Silva GG, Friedman PA, de Paola AA. Clinical usefulness of electrophysiologic testing in patients with ventricular tachycardia and chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy treated with amiodarone or sotalol. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003; 14: 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hagar JM, Rahimtoola SH. Chagas' heart disease in the United States. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Araujo EF, Chamlian EG, Peroni AP, Pereira WL, Gandra SM, Rivetti LA. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: long‐term follow up. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2014; 29: 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Menezes Junior ADS, Lopes CC, Cavalcante PF, Martins E. Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy patients and resynchronization therapy: a survival analysis. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2018; 33: 82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benchimol‐Barbosa PR. Noninvasive prognostic markers for cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmia in long‐term follow‐up of subjects with chronic Chagas' disease. Braz J Med Biol Res 2007; 40: 167–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bocchi EA, Rassi S, Guimarães GV, Argentina C, Brazil SI. Safety profile and efficacy of ivabradine in heart failure due to Chagas heart disease: a post hoc analysis of the SHIFT trial. ESC Heart Failure 2018; 5: 249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cardinalli‐Neto A, Bestetti RB, Cordeiro JA, Rodrigues VC. Predictors of all‐cause mortality for patients with chronic Chagas' heart disease receiving implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007; 18: 1236–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cardinalli‐Neto A, Nakazone MA, Grassi LV, Tavares BG, Bestetti RB. Implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator therapy for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with severe Chagas cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2011; 150: 94–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cardoso J, Novaes M, Ochiai M, Regina K, Morgado P, Munhoz R, Brancalhão E, Lima M, Barretto ACP. Chagas cardiomyopathy: prognosis in clinical and hemodynamic profile C. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010; 95: 518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carrasco HA, Parada H, Guerrero L, Duque M, Durán D, Molina C. Prognostic implications of clinical, electrocardiographic and hemodynamic findings in chronic Chagas' disease. Int J Cardiol 1994; 43: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. da Fonseca SMS, Belo LG, Carvalho H, Araújo N, Munhoz C, Siqueira L, Maciel W, Andréa E, Atié J. Clinical follow‐up of patients with implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator. Arq Bras Cardiol 2006; 88: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Souza ACJ, Salles G, Hasslocher‐Moreno AM, de Sousa AS, Alvarenga Americano do Brasil PE, Saraiva RM, Xavier SS. Development of a risk score to predict sudden death in patients with Chaga's heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2015; 187: 700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Flores‐Ocampo J, Nava S, Márquez MF, Gómez‐Flores J, Colín L, López A, Celaya M, Treviño E, González‐Hermosillo JA, Iturralde P. Clinical predictors of ventricular arrhythmia storms in Chagas cardiomyopathy patients with implantable defibrillators. Arch Cardiol Mex 2009; 79: 263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garillo R, Greco OT, Oseroff O, Lucchese F, Fuganti C, Montenegro JL, Arocha AF, Medina JCB, Sirena JJ. Cardiodesfibrilador Implantable como Prevención Secundaria en la Enfermedad de Chagas. Los Resultados del Estudio Latinoamericano ICD‐LABOR. Reblampa 2004; 17: 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heringer‐Walther S, Moreira MCV, Wessel N, Wang Y, Ventura TM, Schultheiss H‐P, Walther T. Does the C‐type natriuretic peptide have prognostic value in Chagas disease and other dilated cardiomyopathies? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006; 48: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mady C, Cardoso RH, Barretto AC, da Luz PL, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. Survival and predictors of survival in patients with congestive heart failure due to Chagas' cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1994; 90: 3098–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mendoza I, Camardo J, Moleiro F, Castellanos A, Medina V, Gomez J, Acquatella H, Casal H, Tortoledo F, Puigbo J. Sustained ventricular tachycardia in chronic chagasic myocarditis: electrophysiologic and pharmacologic characteristics. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57: 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nunes MCP, Rocha MOC, Ribeiro ALP, Colosimo EA, Rezende RA, Carmo GAA, Barbosa MM. Right ventricular dysfunction is an independent predictor of survival in patients with dilated chronic Chagas' cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2008; 127: 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Senra T, Ianni BM, Costa ACP, Mady C, Martinelli‐Filho M, Kalil‐Filho R, Rochitte CE. Long‐term prognostic value of myocardial fibrosis in patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 2577–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shen L, Ramires F, Martinez F, Bodanese LC, Echeverría LE, Gómez EA, Abraham WT, Dickstein K, Køber L, Packer M, Rouleau JL, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Jhund PS, Gimpelewicz CR, McMurray JJV, Paradigm HF , Investigators A, Committees . Contemporary characteristics and outcomes in Chagasic heart failure compared with other nonischemic and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2017; 10: e004361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Silva SA, Gontijo ED, Dias JCP, Andrade CGS, Amaral CFS. Predictive factors for the progression of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy in patients without left ventricular dysfunction. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2015; 57: 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vieira de Melo RM, de Azevedo DFC, Lira YM, Cardoso de Oliveira NF, Passos LCS. Chagas disease is associated with a worse prognosis at 1‐year follow‐up after implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator for secondary prevention in heart failure patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019; 30: 2448–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Viotti RJ, Vigliano C, Laucella S, Lococo B, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Ruiz Vera B, Armenti H. Value of echocardiography for diagnosis and prognosis of chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy without heart failure. Heart 2004; 90: 655–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Femenía F, Arce M, Arrieta M, McIntyre W, Baranchuk A. ICD implant without defibrillation threshold testing: patients with Chagas disease versus patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag 2012; 3: 662–667. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martinelli M, de Siqueira SF, Sternick EB, Rassi A Jr, Costa R, Ramires JA, Kalil FR. Long‐term follow‐up of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator for secondary prevention in Chagas' heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110: 1040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barbosa MP, da Costa Rocha MO, de Oliveira AB, Lombardi F, Ribeiro AL. Efficacy and safety of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators in patients with Chagas disease. Europace 2013; 15: 957–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Maron BJ. Clinical course and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 655–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hasslocher‐Moreno AM, Saraiva RM, Sangenis LHC, Xavier SS, de Sousa AS, Costa AR, de Holanda MT, Veloso HH, Mendes F, Costa FAC, Boia MN, Brasil P, Carneiro FM, da Silva GMS, Mediano MFF. Benznidazole decreases the risk of chronic Chagas disease progression and cardiovascular events: a long‐term follow up study. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 31: 100694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rücker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JPT. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Cumulative Risk of All‐Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S2. Subgroup Analysis of Population Characteristics in Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy Bar Graph.

Figure S3. Forest Plot of Heart Failure Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S4. Forest Plot of Sudden Death Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S5. Forest Plot of Stroke Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S6. Cumulative Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S7. Bubble Plot of Cardiovascular Mortality in Relation to Ejection Fraction.

Figure S8. Forest Plot of Non‐cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Figure S9. Funnel Plot for Publication Bias.

Table S1. Meta‐regression Analysis of Mortality of Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.

Table S2. Subgroup Analysis of Mortality and Population Characteristics in Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy.