Abstract

Aims

There is an emerging interest in elucidating the natural history and prognosis for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in whom left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) subsequently improves. The characteristics and outcomes were compared between heart failure with recovered ejection fraction (HFrecEF) and persistent HFrEF.

Methods and results

This is a retrospective study of adults who underwent at least two echocardiograms 3 months apart between 1 November 2015 and 31 October 2019 with an initial diagnosis of HFrEF. The subjects were divided into HFrecEF group (second LVEF > 40%, ≥10% absolute improvement in LVEF) and persistent HFrEF group (<10% absolute improvement in LVEF) according to the second LVEF. To further study the characteristics of HFrecEF patients, the cohort was further divided into LVEF improvement of 10–20% and >20% subgroups. The primary outcomes were all‐cause mortality and rehospitalization. A total of 1160 HFrEF patients were included [70.2% male, mean (standard deviation) age: 62 ± 13 years]. On the second echocardiogram, 284 patients (24.5%) showed HFrecEF and 876 patients (75.5%) showed persistent HFrEF. All‐cause mortality was identified in 23 (8.10%) HFrecEF and 165 (18.84%) persistent HFrEF, whilst 76 (26.76%) and 426 (48.63%) showed rehospitalizations, respectively. Survival analysis showed that the persistent HFrEF subgroup experienced a significantly higher mortality at 12 and 24 months and a higher hospitalization at 12, 24, 48, and more than 48 months following discharge. Multivariate Cox regression showed that persistent HFrEF had a higher risk of all‐cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 2.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.49–3.56, P = 0.000] and rehospitalization (HR 1.85, 95% CI 1.45–2.36, P = 0.000) than the HFrecEF group. Subgroup analysis showed that the LVEF ≥ 20% improvement subgroup had lower rates of adverse outcomes compared with those with less improvement of 10–20%.

Conclusions

Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction is a distinct HF phenotype with better clinical outcomes compared with those with persistent HFrEF. HFrecEF patients have a relatively better short‐term mortality at 24 months but not thereafter.

Keywords: Heart failure, Prognosis, Echocardiography, Left ventricular ejection fraction

Introduction

The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the most assessed parameter used for risk stratification and determination of treatment options. However, it is not static and can change dynamically, worsening with disease progression or improving with appropriate heart failure (HF) treatment or correction of the underlying pathology. 1 , 2 The latest expert consensus recommended the diagnostic criteria for heart failure with recovered ejection fraction (HFrecEF) 1 : (i) documentation of an LVEF < 40% at baseline; (ii) ≥10% absolute improvement in LVEF; and (iii) a second measurement of LVEF > 40%. To identify HFrecEF, LVEF must be reassessed at least 3 to 6 months after the baseline measurement. This timeframe is proposed to avoid shorter‐term changes due to alterations in heart rate or myocardial load. 1 , 3 However, even for those with HFrecEF, LVEF can be affected by different variables, such as the nature and degree of myocardial injury, left ventricular remodelling, and type of pharmacological or intervention therapy. 4 Recovery of ejection fraction does not indicate freedom from HF indefinitely, and medical and device treatment with cardiac rehabilitation should continue. 1 , 5

The clinical course between HFrecEF and persistent heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may differ, yet few studies have specifically examined such differences 3 , 6 even though there is some evidence of better prognosis in the HFrecEF cohort. 6 Consequently, in this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics, as well as short‐term and long‐term prognosis in HFrecEF and persistent HFrEF.

Methods

Study population

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University. The requirement of informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective and observational nature of the study. The medical records of adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) who underwent echocardiography between 1 November 2015 and 31 October 2019 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University were obtained. The inclusion criteria were baseline LVEF < 40%. The exclusion criteria were patients with fewer than two echocardiograms available for comparison, or an absence of two echocardiograms at least 3 months apart. Echocardiography was performed when patients had treated HF in stable conditions before discharge by experienced cardiologists. Other parameters such as clinical characteristics, comorbidities, drug therapy, laboratory values, and echocardiography findings of the subjects were collected and recorded from Yidu Cloud. Yidu Cloud is one of the largest databases in China, being derived from nearly 100 hospitals. It integrates data from both ambulatory and inpatient settings and covers diagnosis and procedure codes, laboratory results, clinical observations, and medications. No personally identifiable data were included in the database extracted for this study.

Classification of heart failure cases

Patients were divided into (i) HFrecEF, which was defined as current LVEF > 40% but any previously documented LVEF < 40%, ≥10% absolute improvement in LVEF, and (ii) persistent HFrEF, which was defined as previous LVEF < 40%, <10% absolute improvement in LVEF. HFrecEF patients were further divided into LVEF improvement of 10–20% and >20% subgroups. If three or more echocardiograms were available, the one after the 3 month time interval was used for classification of LVEF improvement.

Endpoints

Clinical events were ascertained using information in the Yidu Cloud and were based on review of the primary diagnoses documented on each discharge summary during the follow‐up period. The events included in this analysis were all‐cause death and all‐cause rehospitalization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistical Software, Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Characteristics were summarized with continuous variables expressed as means ± standard deviation and categorical variables presented as frequencies and percentages. Measurement data with a non‐normal distribution were expressed as the median [interquartile range (IQR)]. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for multi‐group comparisons. Characteristics were compared across HF groups using analysis of variance or χ 2 tests, as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to describe the cumulative incidence of adverse events, and the log‐rank test was used to compare differences. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were performed to explore the association between risk factors and endpoints. Variables selected for multivariate Cox analysis included those with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis, or those that have previously been shown to be important in determining prognosis. All values were two‐tailed, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

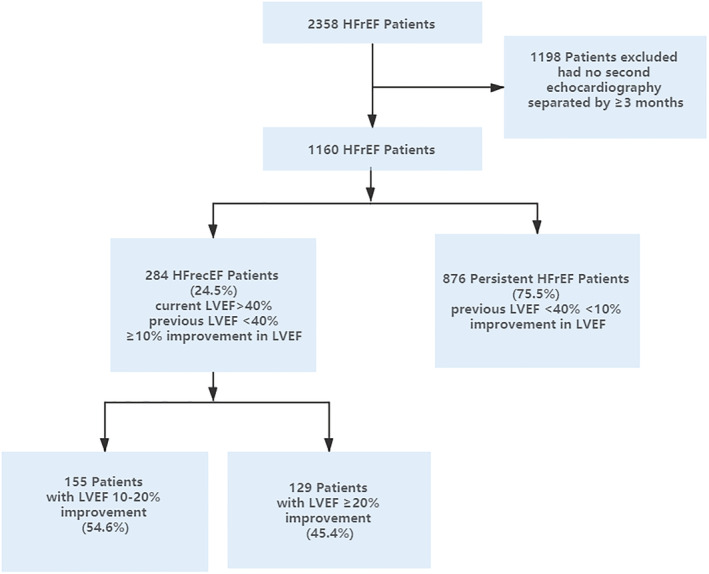

A total of 2358 patients received a diagnosis of HFrEF at our institution between 1 November 2015 and 31 October 2019 with 1198 patients excluded due to the lack of a second echocardiogram separated by >3 months apart for comparison (Figure 1 ). The remaining 1160 patients were included as the study cohort. Of these, 814 (70.2%) were male, and the mean (standard deviation) age was 62 ± 13 years. A total of 284 patients (24.5%) showed HFrecEF, and 876 patients (75.5%) represented persistent HFrEF. Their baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1 . Overall, patients with HFrecEF (i) were younger, had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and had faster heart rate; (ii) more likely to suffer from hypertension but less likely to have coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, or cerebrovascular disease; (iii) were more likely to be on guideline‐directed medical therapy for their diagnosis, including angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and beta‐blocker, but there is no statistical difference, less likely to be dispensed medications including aspirin, spironolactone, loop diuretics, nitrates, and statins; (iv) were more likely to receive a pacemaker, less likely to have other device therapy [0.70% had implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD); 2.11% had cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)]; (v) had lower level of BNP and higher level of haemoglobin, but haemoglobin did not show statistical differences between the two groups; and (vi) showed higher right ventricular diameter, interventricular septal thickness, and lower left ventricular diameter.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient identification, exclusion, and classification. HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients at the time of first echocardiogram

| Characteristics | All patients | HFrecEF | Persistent HFrEF | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1160 | 284 | 876 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.99 ± 13.29 | 59.37 ± 15.14 | 62.84 ± 12.52 | 0.0001 |

| Male | 814 (70.17%) | 209 (73.59%) | 559 (69.06%) | 0.1473 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | ||||

| Systolic | 132.9 ± 23.02 | 137.2 ± 23.60 | 131.5 ± 22.67 | 0.0003 |

| Diastolic | 80.89 ± 14.55 | 83.50 ± 16.52 | 80.04 ± 13.75 | 0.0005 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 87.24 ± 22.50 | 92.65 ± 24.75 | 85.50 ± 21.46 | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class III to IV | 277 (23.88%) | 71 (25.00%) | 206 (23.52%) | 0.6102 |

| History, no. (%) | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 478 (41.21%) | 86 (30.28%) | 382 (43.61%) | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 309 (26.64%) | 82 (28.87%) | 227 (25.91%) | 0.3268 |

| Cancer | 55 (4.74%) | 16 (5.63%) | 39 (4.45%) | 0.4155 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 141 (12.16%) | 25 (8.80%) | 116 (13.24%) | 0.0466 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 387 (33.36%) | 77 (27.11%) | 310 (35.39%) | 0.0102 |

| Hypertension | 718 (61.90%) | 196 (69.01%) | 522 (59.59%) | 0.0045 |

| Therapy, no. (%) | ||||

| ACEI/ARB | 882 (76.03%) | 233 (82.04%) | 671 (76.60%) | 0.0545 |

| Aspirin | 502 (43.28%) | 87 (30.63%) | 415 (47.37%) | <0.0001 |

| Beta‐blockers | 1091 (94.05%) | 273 (96.13%) | 830 (94.75%) | 0.3505 |

| Digoxin | 320 (27.59%) | 80 (28.17%) | 240 (27.40%) | 0.8004 |

| Loop diuretics | 519 (44.74%) | 92 (32.39%) | 387 (48.74%) | <0.0001 |

| Nitrates | 397 (34.22%) | 64 (22.54%) | 333 (38.01%) | <0.0001 |

| Spironolactone | 761 (65.60%) | 160 (56.34%) | 626 (71.46%) | <0.0001 |

| Statins | 625 (53.88%) | 115 (40.49%) | 510 (58.22%) | <0.0001 |

| Warfarin | 349 (30.09%) | 92 (32.39%) | 225 (29.34%) | 0.3291 |

| Pacemaker | 59 (5.09%) | 21 (7.45%) | 38 (4.34%) | 0.0389 |

| ICD | 21 (1.81%) | 2 (0.70%) | 19 (2.17%) | 0.1076 |

| CRT | 51 (4.40%) | 6 (2.11%) | 45 (5.14%) | 0.0307 |

| Laboratory values, median (IQR) | ||||

| White blood cell, ×109/L | 7.596 ± 3.099 | 7.601 ± 3.328 | 7.595 ± 3.023 | 0.9760 |

| Haemoglobin level, g/L | 138.9 ± 19.40 | 140.3 ± 20.95 | 138.4 ± 18.86 | 0.1404 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 204.8 ± 66.81 | 210.7 ± 80.64 | 202.9 ± 61.58 | 0.0863 |

| Cr, μmol/L | 92.45 ± 66.13 | 90.26 ± 52.15 | 93.13 ± 69.92 | 0.5548 |

| UA, μmol/L | 460.0 ± 160.9 | 456.4 ± 148.8 | 461.1 ± 164.5 | 0.6935 |

| Na+, μmol/L | 141.7 ± 3.370 | 141.8 ± 3.283 | 141.7 ± 3.399 | 0.6981 |

| Glu, μmol/L | 6.253 ± 2.520 | 5.986 ± 2.220 | 6.336 ± 2.602 | 0.0586 |

| Dimer, μmol/L | 530.0 (250.0, 1183) | 480.0 (250.0, 1130) | 540.0 (250.0, 1220) | 0.1452 |

| BNP level, ng/L | 637.4 (270.0, 1425) | 428.6 (176.6, 1042) | 675.9 (278.8, 1442) | 0.1461 |

| Echocardiography findings, median (IQR), no. (%) | ||||

| Left ventricular diameter, mm | 60.75 ± 8.413 | 58.70 ± 8.130 | 61.40 ± 8.402 | <0.0001 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 44.72 ± 6.380 | 45.20 ± 6.649 | 44.57 ± 6.289 | 0.1656 |

| Interventricular septal thickness, mm | 10.28 ± 1.943 | 10.72 ± 1.723 | 10.14 ± 1.988 | <0.0001 |

| E/e′ | 15.07 ± 6.366 | 14.26 ± 6.791 | 15.32 ± 6.219 | 0.0625 |

| Right ventricular diameter, mm | 19.09 ± 3.138 | 19.53 ± 3.701 | 18.94 ± 2.921 | 0.0074 |

| Pulmonary artery diameter, mm | 23.88 ± 2.872 | 24.05 ± 2.991 | 23.83 ± 2.833 | 0.2640 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 696 (60.00%) | 173 (60.92%) | 523 (59.70%) | 0.7280 |

ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; Cr, creatinine; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; E/e′, mitral Doppler early velocity/mitral annular early velocity; Glu, glucose; HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation; UA, uric acid.

Clinical outcomes

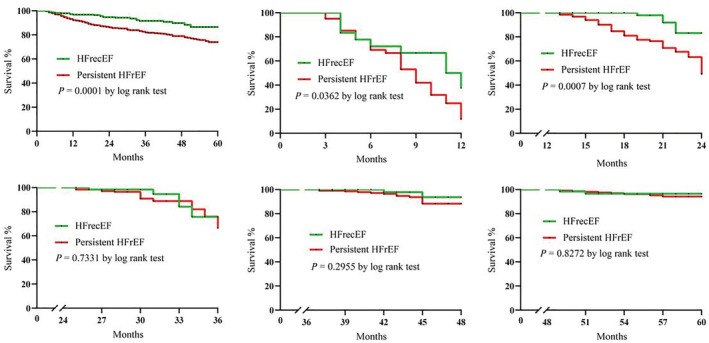

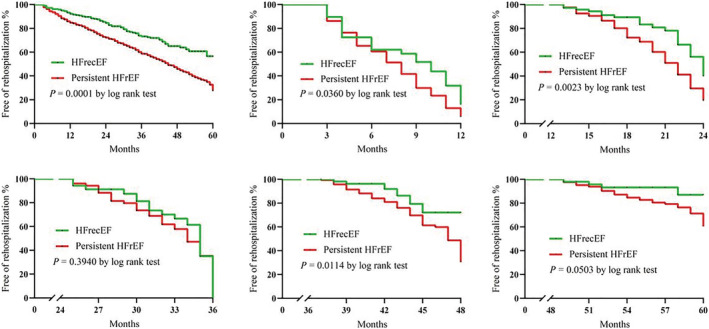

Over a median follow‐up of 36 months (IQR: 21–48 months), 188 patients died (HFrecEF: n = 23, 8.10%; persistent HFrEF: n = 165, 18.84%) and 502 patients were rehospitalized (HFrecEF: n = 76, 26.76%; persistent HFrEF: n = 426, 48.63%). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for all‐cause mortality and all‐cause rehospitalization are shown in the top and bottom panels of Figures 2 and 3 , respectively (significant differences by the log‐rank test: P = 0.0001). The mortality rate significantly differed at 12 and 24 months but not at later time points after discharge. However, for rehospitalization, significant differences were observed at 12, 24, and 48 months after discharge.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for all‐cause mortality between the two groups at 12, 24, 36, 48, and more than 48 months. HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for all‐cause rehospitalization between the two groups at 12, 24, 36, 48, and more than 48 months. HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that age [hazard ratio (HR) 1.026, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.013–1.040, P < 0.000], creatinine (HR 1.002, 95% CI 1.001–1.003, P = 0.001), and glucose (HR 1.058, 95% CI 1.002–1.117, P = 0.043) were significant predictors of higher all‐cause mortality (Table 2 ). The following protective factors were identified: systolic blood pressure (HR 0.973, 95% CI 0.967–0.979, P < 0.000), New York Heart Association class III to IV (HR 0.618, 95% CI 0.411–0.929, P = 0.021), use of ACEI/ARB (HR 0.677, 95% CI 0.478–0.959, P = 0.028), and haemoglobin (HR 0.990, 95% CI 0.982–0.997, P = 0.005). In addition, the persistent HFrEF group had at least a two‐fold increased risk of all‐cause mortality compared with the HFrecEF group both before (HR 2.304, 95% CI 1.489–3.564, P < 0.000) and after multivariable adjustment (HR 1.973, 95% CI 1.206–3.226, P = 0.007).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard regression for all‐cause mortality

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.031 | 1.019–1.044 | 0.000 | 1.026 | 1.013–1.040 | 0.000 |

| Male | 0.813 | 0.600–1.102 | 0.183 | 0.980 | 0.677–1.420 | 0.916 |

| Blood pressure, systolic | 0.974 | 0.968–0.980 | 0.000 | 0.973 | 0.967–0.979 | 0.000 |

| Blood pressure, diastolic | 0.987 | 0.977–0.997 | 0.013 | 0.991 | 0.980–1.002 | 0.120 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.420 | 1.067–1.890 | 0.016 | 1.087 | 0.789–1.497 | 0.609 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.729 | 1.198–2.497 | 0.003 | 1.393 | 0.932–2.081 | 0.106 |

| NYHA class III to IV | 0.657 | 0.451–0.957 | 0.029 | 0.618 | 0.411–0.929 | 0.021 |

| Beta‐blockers | 0.590 | 0.342–1.017 | 0.057 | 0.806 | 0.438–1.484 | 0.489 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.595 | 0.432–0.820 | 0.002 | 0.677 | 0.478–0.959 | 0.028 |

| Haemoglobin | 0.987 | 0.980–0.993 | 0.000 | 0.990 | 0.982–0.997 | 0.005 |

| BNP | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.085 |

| Cr | 1.002 | 1.001–1.003 | 0.000 | 1.002 | 1.001–1.004 | 0.001 |

| Glu | 1.060 | 1.007–1.116 | 0.026 | 1.058 | 1.002–1.117 | 0.043 |

| Groups | ||||||

| Persistent HFrEF vs. HFrecEF | 2.304 | 1.489–3.564 | 0.000 | 1.973 | 1.206–3.226 | 0.007 |

ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; CI, confidence interval; Cr, creatinine; Glu, glucose; HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis found age (HR 1.009, 95% CI 1.002–1.017, P = 0.018), creatinine (HR 1.002, 95% CI 1.001–1.003, P = 0.000), uric acid (HR 1.001, 95% CI 1.000–1.001, P = 0.005), and glucose levels (HR 1.047, 95% CI 1.009–1.086, P = 0.015) as significant predictors of higher readmission risk (Table 3 ). The identified protective factors were as follows: use of CRT (HR 0.556, 95% CI 0.318–0.972, P = 0.040), ACEI/ARB (HR 0.635, 95% CI 0.506–0.797, P = 0.000), spironolactone (HR 0.603, 95% CI 0.491–0.741, P = 0.000), systolic blood pressure (HR 0.995, 95% CI 0.992–0.999, P = 0.015), haemoglobin (HR 0.989, 95% CI 0.985–0.994, P = 0.000), and serum sodium (HR 0.958, 95% CI 0.933–0.983, P = 0.001). As with all‐cause mortality, the persistent HFrEF group experienced an approximately two‐fold increase in the risk of all‐cause rehospitalization than HFrecEF group both before (HR 1.852, 95% CI 1.451–2.364, P = 0.000) and after multivariable adjustment (HR 1.740, 95% CI 1.336–2.267, P = 0.000).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard regression for all‐cause rehospitalization

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.013 | 1.006–1.020 | 0.000 | 1.009 | 1.002–1.017 | 0.018 |

| Male | 0.815 | 0.675–0.984 | 0.033 | 0.851 | 0.679–1.067 | 0.162 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.293 | 1.085–1.541 | 0.004 | 1.113 | 0.914–1.356 | 0.286 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.247 | 1.042–1.493 | 0.016 | 0.981 | 0.789–1.221 | 0.866 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.379 | 1.081–1.757 | 0.010 | 1.159 | 0.891–1.507 | 0.273 |

| CRT | 0.527 | 0.315–0.882 | 0.015 | 0.556 | 0.318–0.972 | 0.040 |

| Beta‐blockers | 0.684 | 0.473–0.989 | 0.044 | 0.970 | 0.649–1.451 | 0.883 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.545 | 0.444–0.668 | 0.000 | 0.635 | 0.506–0.797 | 0.000 |

| Spironolactone | 0.598 | 0.499–0.718 | 0.000 | 0.603 | 0.491–0.741 | 0.000 |

| Loop diuretics | 0.752 | 0.629–0.898 | 0.002 | 1.096 | 0.869–1.382 | 0.437 |

| Blood pressure, systolic | 0.993 | 0.990–0.996 | 0.000 | 0.995 | 0.992–0.999 | 0.015 |

| Haemoglobin | 0.988 | 0.983–0.992 | 0.000 | 0.989 | 0.985–0.994 | 0.000 |

| BNP | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.585 |

| Cr | 1.002 | 1.002–1.003 | 0.000 | 1.002 | 1.001–1.003 | 0.000 |

| UA | 1.001 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.030 | 1.001 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.005 |

| Na+ | 0.957 | 0.933–0.980 | 0.000 | 0.958 | 0.933–0.983 | 0.001 |

| Glu | 1.044 | 1.009–1.081 | 0.015 | 1.047 | 1.009–1.086 | 0.015 |

| Groups | ||||||

| Persistent HFrEF vs. HFrecEF | 1.852 | 1.451–2.364 | 0.000 | 1.740 | 1.336–2.267 | 0.000 |

ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; CI, confidence interval; Cr, creatinine; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; Glu, glucose; HFrecEF, heart failure with recovered ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; UA, uric acid.

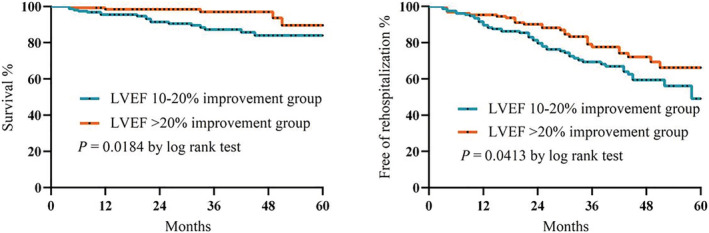

Further, exploratory analysis based on the improvement in LVEF was performed for the HFrecEF patients. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that all‐cause mortality and all‐cause hospitalization were lower in the LVEF ≥ 20% improvement subgroup compared with the 10–20% improvement subgroup (Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for all‐cause mortality and rehospitalization between the LVEF ≥ 20% and LVEF 10–20% improvement subgroups. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that the characteristics and clinical course of patients with HFrecEF and persistent HFrEF were different. Reverse left ventricular remodelling and recovery of LVEF are associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with HFrEF. Compared with persistent HFrEF patients, HFrecEF patients have a relatively better prognosis in the short term, but not in the long term. The higher risk of adverse outcomes experienced by patients in the persistent HFrEF group emphasizes the need for careful follow‐up of this group and for therapeutic strategies that improve outcomes in this population.

Classification of HF into those with reduced, midrange, and preserved ejection fraction is important, 7 and risk stratification strategies depend partly on the behaviour of LVEF 8 , 9 and require a multi‐parametric approach. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 LVEF may recover, remain stable, or decline owing to a complex interaction between comorbidities, frailty status, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 medical or device treatment, 20 and disease progression. Our results are consistent with the results of other studies; compared with persistent HFrEF, subjects with HFrecEF are younger, with a higher prevalence of hypertension, lower prevalence of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus, 3 , 21 and had higher interventricular septal thickness, lower left ventricular diameter, and a better biomarker indicator. Regarding the risk factors associated with death, age, creatinine, and glucose were found to significantly increase the risk of death. The results of echocardiography findings and history of hypertension show that most patients with HFrecEF are those with hypertensive HF; early intervention on patients with HFrecEF can reverse ventricular remodelling, so they have a better prognosis. This relatively low prevalence of coronary artery disease also might have influenced outcomes, as a history of coronary artery disease has been associated with a higher risk of mortality. For example, in the large Improve Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (IMPROVE HF) registry, patients without prior myocardial infarction and non‐ischaemic HF aetiology were both associated with a greater than 10% improvement in LVEF. 22 Although the short‐term prognosis for HFrecEF is favourable, more studies are needed to determine the longer‐term prognosis. Kalogeropoulos et al. also reported that age‐adjusted and sex‐adjusted mortality was lower in HFrecEF patients (4.8%) than in HF with preserved ejection fraction (13.2%) or persistent HFrEF (16.3%) at 3 years of follow‐up. 21 Basuray et al. reported that, by 8 years, nearly 20% of patients with HFrecEF had died or required heart transplantation or the use of a ventricular assist device. 6 Lupón et al. recently reported that the greatest changes in LVEF were seen in the first year after initial diagnosis but 10–15 years after the diagnosis that LVEF exhibited an inverted U shape with declines in LVEF again in those who initially improved. 23 The substantial differences in the number of patients who had died or were rehospitalized during the period of observation in the persistent HFrEF group underscore their high risk of future events. Notwithstanding the differences between these groups, the combination of these data suggests that patients with HFrecEF should be distinguished from those with persistent HFrEF. Moreover, to further explore the characteristics of HFrecEF patients, we conducted a subgroup analysis of patients in the HFrecEF group and found that those with LVEF improvement of more than 20% had better outcomes than those with LVEF improvement of 10–20%.

In contrast to other reports, 6 due to the traditional HF therapies, we found that the use of ACEI/ARB and beta‐blockers was relatively high in the HFrecEF group, agents known to improve LVEF and survival in HFrecEF, but no significant statistical differences across the two groups were observed. During the follow‐up period, it is possible that the more favourable outcomes in the HFrecEF group may be explained by the higher proportion of guideline‐directed medical therapy in this group. Use of beta‐blockers, medications targeting the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis, and pacemaker therapy led to improvement in LVEF in a considerable number of patients with HFrEF. 22 , 24 The latest study shows a performance improvement programme aimed at improving the use of guideline‐directed medical therapy for HF outpatients, the mean LVEF among approximately 4000 patients increased from 25.8% at baseline to 32.3% at 24 months, and 28.6% of patients had a greater than 10% LVEF improvement. 22

Although the prognosis of patients with HFrecEF has improved, they still have the risk of death and hospitalization. Patients with HFrecEF are not truly cured from their HF. 6 , 21 Based on clinical practice experience for patients with HFrecEF, experts have proposed the following assessment, surveillance, and treatment plans: (i) clinical examination, assessment of symptoms, and electrocardiogram 25 , 26 ; (ii) identification of family history of dilated cardiomyopathy and underlying genetic risk 27 ; (iii) measurements of different biomarkers 28 , 29 ; (iv) two‐dimensional echocardiography 30 , 31 ; and (v) cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. 32 It is recommended that LVEF be temporarily retained as part of the assessment of HF, as a rough evaluation of a patient's sensitivity to neurohormonal inhibitors, and during a transition phase to incorporate current evidence‐based medicine into a more personalized evidence‐based HF management plan. This is our future direction for monitoring and testing patients with recovery HF.

Limitations

Considering also the single‐centre nature of our study, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings, such as HF with preserved or midrange ejection fraction. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 We cannot exclude possible survival bias or lead‐time bias, given that an eligible patient must have two echocardiograms ≥3 months apart and the first echocardiogram obtained may not be the first test conducted at HF diagnosis. Additionally, it was difficult to ascertain the duration of HF before enrolment, as diagnosis could have been made at other hospitals, whose records are not linked to ours. The use of beta‐blockers, renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, and spironolactone may have changed during follow‐up, and future studies are needed to examine the effects of medication cross‐over. Moreover, the combination of a neprilysin inhibitor and an angiotensin II receptor blocker, sacubitril/valsartan, has been shown to produce superior benefits on mortality and hospitalization, 38 and future studies should examine whether this medication produces better clinical outcomes in HFrecEF patients. Hospitalizations were ascertained from the Yidu Cloud. Therefore, hospitalization rates may have been underestimated because hospitalizations to hospitals other than our own may have occurred. Although salt and alcohol intake, smoking, medication adherence, and weight can all influence the trajectory of LVEF recovery, we did not have information on these variables in the Yidu Cloud databases. Therefore, a large prospective cohort or a randomized‐controlled study is necessary to understand the characteristics and evaluate the effects of drugs in HF population.

Conclusions

Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction patients tended to be younger and had a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus. Moreover, most patients with HFrecEF are those with hypertension, in whom early intervention can reverse ventricular remodelling and improve clinical outcomes. HFrecEF is a distinct HF phenotype with better clinical outcomes compared with those with persistent HFrEF. HFrecEF patients have a relatively better short‐term mortality at 24 months but not thereafter.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1908209, No. 81700301 and No. 82170385).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the staff for their outstanding efforts in this work, especially those responsible for follow‐up and statistics. The authors would like to thank Yidu Cloud (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd for their assistance in data searching, extraction, and processing.

Zhang, X. , Sun, Y. , Zhang, Y. , Chen, F. , Dai, M. , Si, J. , Yang, J. , Li, X. , Li, J. , Xia, Y. , Tse, G. , and Liu, Y. (2021) Characteristics and outcomes of heart failure with recovered left ventricular ejection fraction. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 5383–5391. 10.1002/ehf2.13630.

Contributor Information

Gary Tse, Email: garytse86@gmail.com.

Ying Liu, Email: yingliu.med@gmail.com.

References

- 1. Wilcox JE, Fang JC, Margulies KB, Mann DL. Heart Failure With Recovered Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76: 719–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2016; 69: 1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Punnoose LR, Givertz MM, Lewis EF, Pratibhu P, Stevenson LW, Desai AS. Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity. J Card Fail. 2011; 17: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. da Silva R, Borges ASR, Silva NP, Resende ES, Tse G, Liu T, Roever L, Biondi‐Zoccai G. How Heart Rate Should Be Controlled in Patients with Atherosclerosis and Heart Failure. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2018; 20: 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gomes‐Neto M, Duraes AR, Conceicao LSR, Roever L, Liu T, Tse G, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Goes ALB, Alves IGN, Ellingsen Ø, Carvalho VO. Effect of Aerobic Exercise on Peak Oxygen Consumption, VE/VCO2 Slope, and Health‐Related Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: a Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2019; 21: 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Basuray A, French B, Ky B, Vorovich E, Olt C, Sweitzer NK, Cappola TP, Fang JC. Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction: clinical description, biomarkers, and outcomes. Circulation. 2014; 129: 2380–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lakhani I, Leung KSK, Tse G, Lee APW. Novel Mechanisms in Heart Failure With Preserved, Midrange, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Front Physiol. 2019; 10: 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Magri D, Gallo G, Parati G, Cicoira M, Senni M. Risk stratification in heart failure with mild reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020; 27: 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stawiarski K, Ramakrishna H. Heart Failure Risk Stratification and the Evolution of the INTERMACS System. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019; 33: 2861–2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corra U, Magini A, Paolillo S, Frigerio M. Comparison among different multiparametric scores for risk stratification in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020; 27: 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tse G, Zhou J, Woo SWD, Ko CH, Lai RWC, Liu T, Liu Y, Leung KSK, Li A, Lee S, Li KHC, Lakhani I, Zhang Q. Multi‐modality machine learning approach for risk stratification in heart failure with left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 45. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 3716–3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tse G, Zhou J, Lee S, Liu Y, Leung KSK, Lai RWC, Burtman A, Wilson C, Liu T, Li KHC, Lakhani I, Zhang Q. Multi‐parametric system for risk stratification in mitral regurgitation: A multi‐task Gaussian prediction approach. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020; 50: e13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scardovi AB, De Maria R, Coletta C, Aspromonte N, Perna S, Cacciatore G, de Maria R, Coletta C, Aspromonte N, Perna S, Cacciatore G, Parolini M, Ricci R, Ceci V. Multiparametric risk stratification in patients with mild to moderate chronic heart failure. J Cardiac Fail 2007; 13: 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Yuan M, Gong M, Tse G, Li G, Liu T. Frailty and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018; 19: 1003–8 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tse G, Gong M, Nunez J, Sanchis J, Li G, Ali‐Hasan‐Al‐Saegh S, Wong WT, Wong SH, Wu WKK, Bazoukis G, Yan GX, Lampropoulos K, Baranchuk AM, Tse LA, Xia Y, Liu T, Woo J, International Health Informatics Study (IHIS) Network . Frailty and Mortality Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017; 18: 1097.e1–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Yuan M, Gong M, Li G, Liu T, Tse G. Associations Between Prefrailty or Frailty Components and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure: A Follow‐up Meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019; 20: 509–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tse G, Gong M, Wong SH, Wu WKK, Bazoukis G, Lampropoulos K, Wong WT, Xia Y, Wong MCS, Liu T, Woo J, International Health Informatics Study (IHIS) Network . Frailty and Clinical Outcomes in Advanced Heart Failure Patients Undergoing Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018; 19: 255–61 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Warraich HJ, Kitzman DW, Whellan DJ, Duncan PW, Mentz RJ, Pastva AM, Nelson MB, Upadhya B, Reeves GR. Physical Function, Frailty, Cognition, Depression, and Quality of Life in Hospitalized Adults ≥60 Years With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure With Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation Heart failure. 2018; 11: e005254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinugasa Y, Yamamoto K. The challenge of frailty and sarcopenia in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart. 2017; 103: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bazoukis G, Tse G, Korantzopoulos P, Liu T, Letsas KP, Stavrakis S, Naka KK. Impact of Implantable Cardioverter‐Defibrillator Interventions on All‐Cause Mortality in Heart Failure Patients: A Meta‐Analysis. Cardiol Rev. 2019; 27: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalogeropoulos AP, Fonarow GC, Georgiopoulou V, Burkman G, Siwamogsatham S, Patel A, Li S, Papadimitriou L. Butler J Characteristics and Outcomes of Adult Outpatients With Heart Failure and Improved or Recovered Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2016; 1: 510–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilcox JE, Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Heywood JT, Inge PJ, McBride ML, Mehra MR, O'Connor CM, Reynolds D, Walsh MN, Gheorghiade M. Factors associated with improvement in ejection fraction in clinical practice among patients with heart failure: findings from IMPROVE HF. Am Heart J. 2012; 163: 49–56 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lupon J, Gavidia‐Bovadilla G, Ferrer E, de Antonio M, Perera‐Lluna A, Lopez‐Ayerbe J, Lupón J, Gavidia‐Bovadilla G, Ferrer E, de Antonio M, Perera‐Lluna A, López‐Ayerbe J, Domingo M, Núñez J, Zamora E, Moliner P, Díaz‐Ruata P, Santesmases J, Bayés‐Genís A. Dynamic Trajectories of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Groote P, Fertin M, Duva Pentiah A, Goeminne C, Lamblin N, Bauters C. Long‐term functional and clinical follow‐up of patients with heart failure with recovered left ventricular ejection fraction after beta‐blocker therapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2014; 7: 434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sze E, Samad Z, Dunning A, Campbell KB, Loring Z, Atwater BD, Chiswell K, Kisslo JA, Velazquez EJ, Daubert JP. Impaired Recovery of Left Ventricular Function in Patients With Cardiomyopathy and Left Bundle Branch Block. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71: 306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prenner SB, Swat SA, Ng J, Baldridge A, Wilcox JE. Parameters of repolarization heterogeneity are associated with myocardial recovery in acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2020; 301: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hershberger RE, Givertz MM, Ho CY, Judge DP, Kantor PF, McBride KL, Morales A, Taylor MRG, Vatta M, Ware SM, ACMG Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee . Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy: a clinical practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2018; 20: 899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aimo A, Gaggin HK, Barison A, Emdin M, Januzzi JL Jr. Imaging, Biomarker, and Clinical Predictors of Cardiac Remodeling in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019; 7: 782–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daubert MA, Adams K, Yow E, Barnhart HX, Douglas PS, Rimmer S, Norris C, Cooper L, Leifer E, Desvigne‐Nickens P, Anstrom K, Fiuzat M, Ezekowitz J, Mark DB, O'Connor CM, Januzzi J, Felker GM. NT‐proBNP Goal Achievement Is Associated With Significant Reverse Remodeling and Improved Clinical Outcomes in HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. 2019; 7: 158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tayal U, Prasad SK. Myocardial remodelling and recovery in dilated cardiomyopathy. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2017; 6: 2048004017734476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adamo L, Perry A, Novak E, Makan M, Lindman BR, Mann DL. Abnormal Global Longitudinal Strain Predicts Future Deterioration of Left Ventricular Function in Heart Failure Patients With a Recovered Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2017; 10: e003788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Youn JC, Hong YJ, Lee HJ, Han K, Shim CY, Hong GR, Suh YJ, Hur J, Kim YJ, Choi BW, Kang SM. Contrast‐enhanced T1 mapping‐based extracellular volume fraction independently predicts clinical outcome in patients with non‐ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: a prospective cohort study. Eur Radiol. 2017; 27: 3924–3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun Y, Wang N, Li X, Zhang Y, Yang J, Tse G, Liu Y. Predictive value of H2 FPEF score in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail 2021; 8: 1244–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goto K, Schauer A, Augstein A, Methawasin M, Granzier H, Halle M, Craenenbroeck EMV, Rolim N, Gielen S, Pieske B, Winzer EB, Linke A, Adams V. Muscular changes in animal models of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: what comes closest to the patient? ESC Heart Fail 2020; 8: 139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scheffer M, Driessen‐Waaijer A, Hamdani N, Landzaat JWD, Jonkman NH, Paulus WJ, van Heerebeek L. Stratified Treatment of Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction: rationale and design of the STADIA‐HFpEF trial. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 4478–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santas E, de la Espriella R, Palau P, Minana G, Amiguet M, Sanchis J, Lupón J, Bayes‐Genís A, Chorro FJ, Núñez VJ. Rehospitalization burden and morbidity risk in patients with heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020; 7: 1007–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lakhani I, Wong MV, Hung JKF, Gong M, Waleed KB, Xia Y, Lee S, Roever L, Liu T, Tse G, Leung KSK, Li KHC. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serum C‐reactive protein in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2020; 26: 1141–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pathadka S, Yan VKC, Li X, Tse G, Wan EYF, Lau H, Lau WCY, Siu DCW, Chan EW, Wong ICK. Hospitalization and mortality in patients with heart failure treated with Sacubitril/Valsartan vs. Enalapril: A Real‐World, Population‐Based Study. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021; 7: 602363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]