Abstract

Little information has been compiled across studies about existing interventions to mitigate issues of medical financial hardship, despite growing interest in health care delivery. The purpose of this qualitative systematic scoping review was to examine content and outcomes of interventions to address medical financial hardship. PRISMA guidelines were applied to present results using PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL, published between January 1980 and August 2020. Additional studies were identified through reference lists of selected papers. Included studies focused on mitigating medical financial hardship from out-of-pocket (OOP) health care expenses as an intervention strategy with at least 1 evaluation component. Screening 2412 articles identified 339 articles for full-text review, 12 of which met inclusion criteria. Variation was found regarding targets and outcome measurement of intervention. Primary outcomes were in the following categories: financial outcomes (eg, OOP expenses), behavioral outcomes, psychosocial, health care utilization, and health status. No included studies reported significant reduction in OOP expenses, perceptions of financial burden/toxicity, or health status. However, changes were observed for behavioral outcomes (adherence to treatment, patient needs addressed), some psychosocial outcomes (mental health symptoms, perceived support, patient satisfaction), and care utilization such as routine health care. No patterns were observed in the achievement of outcomes across studies based on intensity of intervention. Few rigorous studies exist in this emerging field, and studies have not shown consistent positive effects. Future research should focus on conceptual clarity of the intervention, align outcome measurement and achieve consensus around outcomes, and employ rigorous study designs, measurement, and outcome follow-up.

Keywords: medical financial hardship, financial toxicity, health care, interventions

Introduction

Patients' affordability challenges with health care in the United States predate the Great Depression, with policy reforms thereafter attempting to address this pressing issue.1,2 The problem has only grown since. Currently, 1 in 4 American families are experiencing financial burden related to medical care.3 Affordability challenges are among the top 4 reasons patients across health conditions and disease types do not follow through with therapeutic recommendations.4,5

Researchers use several terms to describe the financial hardship experienced by the patients/families as they navigate health care: financial toxicity,6,7 economic/financial burden of disease,8 cost-related nonadherence9/cost-related prescription delay,10 medical financial hardship,11 and financial stress/strain/distress.12 These terms describe concepts that include how one feels about one's financial resources, and/or what one is doing in terms of a behavioral response as a result of one's economic circumstances.13 Terms such as financial toxicity and medical financial hardship often encompass multiple domains of objective hardship, stress, and behavior.

As an example, among people with diabetes, 40% of families report medical financial hardship, resulting in high levels of distress, food insecurity, cost-related treatment nonadherence, and forgone/delayed care.14,15 Cancer, as another example, is one of the most expensive conditions to treat in the United States because of parallel trends of increasing cost of cancer therapies, evolving treatment patterns, greater prevalence of high-deductible health plans, cost sharing, and underinsurance, and progressively increasing survival related to new therapies.7 Families often make substantial financial and behavioral adjustments to their budget and expenses following a cancer diagnosis, which can have a negative impact on both the patient and other family members.16 Financial distress from mounting financial obligations and debt and the erosion of wealth may interfere with the patient's ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment, thereby adversely affecting health outcomes and potentially creating a vicious cycle of mounting expense. Failure to prevent and address this financial toxicity leads to poor treatment optimization, reduced quality of life, high symptom burden, and earlier mortality.17,18 Similar investigations of hardship have been done for other diseases and treatment contexts as well, including Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease, surgery, Crohn's disease, respiratory disease, and stroke.19–27

A growing number of interventions are being developed and tested in health care delivery to mitigate issues of medical financial hardship for patients. The need for such interventions is exacerbated by limited policy changes to address the rising costs of health care. The causes and effects of medical financial hardship are established, especially in oncology,6,7,28–32 but strategies to reduce its burden are less frequently discussed in the literature and systematically studied. There is currently a lack of knowledge about known effective or optimal targets or mechanisms for improving medical financial hardship. Despite increasing calls to intervene on medical financial hardship,7,33 no systematic review of interventions has been published across studies about the types and impacts of existing interventions. The first step in establishing recommendations for strategies to reduce medical financial hardship requires understanding the current state of science on interventions. The purpose of this qualitative systematic scoping review was to examine the existing peer-reviewed literature on content and outcomes of interventions to address medical financial hardship. For this review, medical financial hardship is defined as encompassing either material, psychosocial, or behavioral domains.

Methods

Study design

This review utilized the 5-step scoping review method and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework for reporting standards. PRISMA steps were followed, including (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting results. Study findings from the scoping review were used to establish recommendations for interventions to address current gaps. This study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board.

Literature search strategies

A systematic search of the literature between January 1, 1980, and August 2020 was performed using several databases including PubMed, Scopus, and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search strategy included search queries with a Boolean combination of Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms (eg, medical financial burden, financial hardship, patient, intervention) customized for each literature database. Only English-language, full-text articles were selected for further review. The literature search was performed by trained research assistants in consultation with health sciences librarians, who together refined search queries, screened titles, and retrieved abstracts for potentially eligible studies. Additional studies were identified from reference lists of selected papers. Search results were imported into Mendeley Reference Manager (Mendeley Ltd, London, UK) for initial title and abstract assessment.

Eligibility criteria

Included publications tested interventions mitigating material, psychosocial, or adverse behavioral domains of medical financial hardship. Included studies had at least 1 evaluation component, including process or outcomes evaluation. Pilot studies were included, as well as studies with outcome evaluation without a control group or assignment to more than 1 treatment condition. Studies also had to be published between January 1, 1980, and August 2020, conducted in the United States and published in an English-language journal. Studies were excluded if they were literature reviews, non-empirical recommendation pieces such as an opinion or perspective, or if the full-text article was not available for review.

Data extraction and analysis

First, titles were reviewed for study eligibility to ensure that they described an intervention addressing medical financial hardship. When a title was insufficient to determine study eligibility, the abstracts were reviewed. Two authors (DB and NI) independently reviewed each article included to determine if it met all inclusion criteria. A protocol was used to resolve discrepancies or uncertainty about study inclusion. During the title and abstract screening, the independent reviewers erred toward inclusion. Data were extracted using a form that captured study design, sample and setting, intervention description, and outcomes.

Results

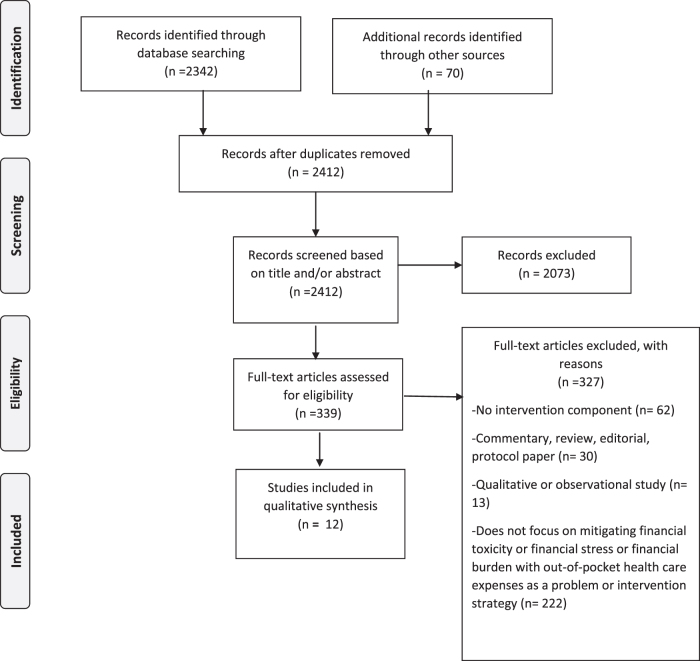

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram describing the literature search and screening processes. Of the 2412 articles that resulted from the literature search, 339 were considered relevant based on the title and/or abstract. These articles were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion criteria. Of the 339 full articles reviewed, 12 articles representing 12 unique studies met the inclusion criteria.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study designs

Five studies used a randomized controlled trial design to evaluate outcomes,34–38 while 1 study used a quasi-experimental design.39 The majority of studies utilized a pre–post evaluation design without a control group to examine changes in outcomes from their intervention.40–45

Program characteristics

Intervention models

Intervention approaches to address medical financial hardship varied by types of support and intensity (Table 1). Three studies tested out-of-pocket (OOP) payment elimination for treatment and/or health care services.34,39,40 One study examined an intensive strategy of care management that included nurses and social workers who managed the care of patients with high health care costs.36 Two studies provided information about assistance as their intervention. One study screened for medical financial hardship and unmet social risk factors in a sample with diabetes and provided resource options to meet each need.41 Another study provided informational decision support for living donor kidney transplant recipients, supplemented with information about donor financial assistance for both medical and nonmedical expenses.38 Four studies used patient and or/financial navigation as an intervention, where ongoing support sessions with trained personnel emphasized identifying and addressing barriers to treatment, including treatment costs and nonmedical social and economic needs.35,42,44,45 Three studies used financial education as an intervention.37,42,45 One study used a program for teaching financial management skills to parents of pediatric patients.37 Two studies coupled financial skills training with financial counseling and financial navigation support.42,45

Table 1.

Included Studies

| Study | Research design | Objective | Participants | Disease | Setting | Intervention(s) | Low-touch/high-touch intervention | Target of medical financial hardship | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ansah, 2009, Ghana34 | Randomized controlled trial | Test the impact of free health care on health outcomes | 2194 households with 2592 children younger than age 5 years | Anemia | Community - non-clinic | Intervention: free health care (study paid health care fees) Control: paid user fees for health care |

Low touch | Co-payments for health care services | Primary outcome: Moderate anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dl) Secondary outcomes: Health care utilization, severe anemia, mortality Removing out-of-pocket payments increased use of primary care but not on the health outcomes measured. |

| Banegas, 2019, United States35 | Randomized controlled trial | To evaluate a Financial Navigator pilot addressing patients' concerns/needs regarding medical care costs in an integrated health care system | 136 adults, aged ≥18 years, enrolled in Kaiser Permanente Northwest health care system | NA | Large integrated health care system | Intervention: Financial Navigator pilot program - received support from trained patient navigators; ability to address patients' needs and concerns surrounding medical care costs. Control: standard patient navigation support |

High touch | Medical care expenses | Primary outcome: satisfaction with medical care, satisfaction with cost concerns/needs assistance, and satisfaction with navigation services (intervention only). Intervention participants reported higher satisfaction with care and higher satisfaction with cost concerns assistance vs. comparison participants at 30-day follow-up, controlling for baseline responses. |

| Bell, 2015, United States36 | Randomized controlled trial | To evaluate outcomes of a registered nurse–led care management intervention for disabled Medicaid beneficiaries with high health care costs | 1120 disabled Medicaid beneficiaries with mental health and/or substance abuse problems and comorbid physical conditions | Mental health, substance abuse, chronic disease | Community - non-clinic | Intervention: intensive strategy of care management from a team comprising 3 full-time RNs, 2 social workers (MSWs) with drug/alcohol treatment training, and a bachelor's–level chemical dependency counselor. Control: Medicaid-covered care as usual |

High touch | Medical care expenses | Primary outcome: costs and use of health services The intervention group had higher odds of outpatient mental health service use and higher prescription drug costs than controls in the post period. Findings indicated no health care cost savings for disabled Medicaid beneficiaries randomized to intensive care management. |

| Elliott, 2013, United States40 | Pre–post | Patient outcomes that eliminate co-pays | 242 patients completed registration; 211 enrolled in program | Diabetes | Community medical center | Intervention: Co-payment elimination program | Low touch | Co-payments | Primary outcome: medication adherence, cost-related nonadherence, health status, out-of-pocket health care costs Results: significant reduction in monthly out-of-pocket costs, reduction in cost-related nonadherence, increased medication adherence, and high satisfaction. No changes in glycemic control. Process outcomes: helped take better care of diabetes, high satisfaction. |

| Nipp, 2019, United States39 | Quasi-expermental | Assess the impact of an equity intervention on clinical trial patients' financial burden | 260 patients already participating in a therapeutic cancer clinical trial at Massachusetts General Hospital, ages ≥18 years | Cancer | Academic medical center | Intervention: financial assistance from nonprofit for expenses incurred for clinical trial participation | Low touch | Travel and lodging expenses related to participation in a clinical trial | Primary outcome: assessed financial burden at baseline, day 45, and day 90. Results: intervention patients experienced greater improvements in their travel- and lodging-related cost concerns. Overall financial burden did not improve. |

| Patel, 2018, United States41 | Pre–post | Examined a financial burden resource tool's acceptability and the preliminary effects on patient-centered outcomes among adults with diabetes or prediabetes seen in a clinical setting | 104 adult patients with diabetes | Diabetes | Academic medical center | Intervention: financial burden resource tool, which provided tailored, low-cost resource options for diabetes management and other social needs | Low touch | Medical care expenses, nonmedical social needs | Primary outcome: cost-related nonadherence; perceived financial stress, financial management skills. Results: significant improvements between baseline and 2-month follow-up were observed for skipping doses of medicines because of cost, and financial management skills. There were no significant changes in perception of financial burden. Process outcomes: highly acceptable: learned a lot, topics relevant, applicable to their lives, liked information. |

| Shankaran, 2018, United States42 | Pre–post | To assess the feasibility and impact of a financial navigation program | 34 patients with cancer | Cancer | Academic medical center | Intervention: financial education course followed by monthly contact with a financial counselor and a case manager for 6 months | High touch | Financial literacy, medical care expenses, nonmedical social needs | Primary outcome: self-reported financial burden and anxiety. Results: anxiety about costs decreased over time in 33% of patients, whereas self-reported financial burden did not substantially change. |

| Worley, 1991, United States37 | Randomized controlled trial | To determine whether teaching families about financial management is helpful | 115 families | Children with chronic disabilities (spina bifida) | Academic medical center | Teaching financial management skills to parents | High touch | Financial literacy | Primary outcome: financial management skills. Results: improvements in financial management skills and behaviors. |

| Sadigh, 2019, United States43 | Pre–post | Assess the feasibility of providing a financial navigation program to brain cancer patients | 12 participants -18 years or older -new diagnosis of either primary malignant brain cancer or brain metastasis -received or plan to receive surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy | Brain cancer | Academic medical center | Intervention: financial navigation program for 6 months. | High touch | Medical care expenses, nonmedical social needs | Primary outcome: financial toxicity. Results: no significant differences in financial toxicity. |

| Boulware, 2018, United States38 | Randomized clinical trial | Examine the effects of delivering informational decision support and donor financial assistance on African American patients receiving hemodialysis | 92 participants -self-identified as African American -initiated hemodialysis within 2 years of the screening -18 years or older | African American adults receiving hemodialysis | Community clinics | Interventions: either educational materials about kidney replacement treatment options or educational materials about kidney replacement options paired with a living donor financial assistance program Control: Usual hemodialysis care |

Low touch | Medical and nonmedical expenses | Primary outcome: patients' actions to pursue living donor kidney transplants. Results: no significant improvements in living donor kidney transplant actions, and no participants used living donor financial assistance benefit. |

| Madore, 2014, United States44 | Pre–post | Examine changes in common barriers faced by underserved breast cancer patients before and after a patient navigation and telephone counseling intervention | 20 participants -medically and economically underserved women - recent diagnosis of breast cancer -receiving care at medical center where they were recruited | Breast cancer | Community medical center | Intervention: 7 to 9 phone counseling sessions and 3 to 5 on-site navigation sessions to address treatment barriers | High touch | Medical and nonmedical expenses and logistics | Primary outcome: depression, cancer-related distress, social support, and financial barriers. Results: decrease in depression and cancer-related distress and an increase in social support; participation in program resulted in help overcoming financial barriers, transportation problems, and communication barriers with staff. |

| Watabayashi, 2020, United States45 | Pre–post | Assess feasibility of enrolling patient-caregiver dyads in a program providing financial counseling, insurance navigation, and assistance with medical and cost of living expenses | 30 participants-dyads -18 years or older -any-stage solid tumor diagnosis -actively receiving systemic therapy or received systemic therapy in past 6 months - caregiver providing unpaid support to patient undergoing cancer treatment | Cancer (solid tumor) and caregivers | Academic medical center | Intervention: financial education video, had monthly contact with a consumer education case manager, and were eligible to receive help with unpaid cost of living bills | High touch | Financial literacy, medical care expenses, nonmedical social needs | Primary outcome: patient financial hardship and caregiver strain. Results: patient financial hardship and caregiver strain did not improve. |

MSW, master of social work; NA, not applicable; RN, registered nurse.

Five studies tested low-touch interventions,34,38–41 and 7 studies tested high-touch interventions.35–37,42–45

Setting and target populations

Half of the studies included were conducted in academic medical centers,39,37,41–43,45 while 1 study was conducted in an integrated health system.35 Three studies were conducted in community clinical settings,38,40,44 and 2 studies were in nonclinical community settings.34,36 Studies primarily focused on adults as the primary target of intervention, while 2 studies focused on the family/household.34,37 Six studies focused on individuals with cancer,39,42–45 while other studies focused on populations with diabetes,40,41 mental health,36 anemia,34 kidney disease,38 chronic disability,37 and general chronic care populations.35,36

Target of medical financial hardship

Eleven out of 12 studies targeted OOP expenses related to patients' medical care as part of the intervention strategy.34–36,38–45 One study focused exclusively on financial literacy.37 Four studies focused on addressing OOP expenses related to direct treatment and co-payments only,34–36,40 while 7 studies targeted not only medical expenses, but also nonmedical needs such as transportation costs; support with utilities and food, among other items; logistics or expenses.38–39,41–45 Two studies targeted financial literacy, medical care expenses, and nonmedical social needs.42–45

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes measured in included studies were classified into the following categories: financial, behavioral, psychosocial, health care utilization, and health status (Table 2). Two studies measured financial outcomes, specifically OOP expenses of patients.36,40 Three studies measured behavioral outcomes. One study measured adherence behaviors to the treatment plan,41 1 study measured uptake of offered assistance,38 and 2 studies measured financial management skills.37–41 The majority of studies addressed psychosocial outcomes. Six studies measured financial stress of participants,39,41–45 1 study measured mental health and social support,44 1 study measured patient satisfaction,35 and 1 study measured caregiver strain.45 Finally, 2 studies measured disease outcomes,34,40 and health care utilization.34,36

Table 2.

Outcomes Measured Across Included Studies

| Financial | Behavioral | Psychosocial | Health care utilization | Health status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-pocket expenses36,40 | Adherence to treatment41 | Patient satisfaction35 | Outpatient mental health service use36 | Disease markers34,40 |

| Uptake of offered assistance38 | Mental health symptoms44 | Use of primary care34 | ||

| Financial management skills37–41 | Perceived social support44 | |||

| Caregiver strain45 | ||||

| Financial stress39,41–45 |

Study findings

No patterns were observed in the achievement of desired outcomes between studies testing low-touch and high-touch interventions.

Financial outcomes

No included studies showed reduction in OOP expenses after the intervention.36,40

Behavioral outcomes

There were consistent positive findings across studies demonstrating improvement in behavioral outcomes after intervention, specifically for adherence to the treatment regimen,40,41 having their needs addressed or uptake of offered assistance,39,44 and financial skills/management behavior.37,41

Psychosocial outcomes

After intervention, included studies showed improvements in perceived social support,44 improved patient satisfaction,35 and improved mental health symptoms.42,44 There were consistent findings across studies showing no changes in perceptions of financial burden/toxicity,39,41–43,45 and no change in caregiver strain45 after the intervention.

Health care utilization outcomes

Findings were consistent across studies around health care utilization. Both studies that measured health care utilization as a primary outcome showed increased use of desired forms of health care, specifically primary care use, and outpatient mental health service use after the intervention.34,36

Health status outcomes

No included studies showed changes in health status after the intervention.34,40

Discussion

This qualitative systematic scoping review is the first to the authors' knowledge to report on the content and outcomes of interventions to mitigate medical financial hardship. This review was undertaken in order to inform future interventions and research to reduce medical financial hardship. A total of 339 articles were assessed, which yielded only 12 articles that evaluated an intervention to address medical financial hardship, identifying little consensus on effective, evidence-based approaches. Not all included an appropriate control condition, further diminishing current knowledge.

Variation was found across studies regarding both strategy and intervention targets and outcome measurement. Included interventions were designed to reduce medical care expenses and co-payments, and improve financial literacy, nonmedical social needs, and care logistics – either exclusively or in combination. This variation reflects conceptual heterogeneity around what encompasses medical financial hardship. Within some frameworks, and at the health policy level, medical financial hardship is often discussed in the context of health insurance, objective OOP expenses, and income loss constituting burden.28 Tucker-Seeley and Thorpe have proposed a material-psychosocial-behavioral model of medical financial hardship that considers a broader definition of hardship encompassing nonmedical social needs, as well as financial literacy in the “material” domain, and financial stress in the psychosocial domain.13 No included studies were guided by a theoretical or conceptual framework specific to medical financial hardship, complicating how intervention targets lead to improvement in chosen outcomes, and thus limiting their impact.

No included studies reported significant reduction in OOP expenses, perceptions of financial burden/toxicity, or health status. However, changes were observed in behavioral outcomes (adherence to treatment regimen, perception that patient needs were addressed), some psychosocial outcomes (mental health symptoms, perceived support, patient satisfaction), and health care utilization such as greater use of desired forms of routine health care. Although included studies demonstrated a mix of low-touch and high-touch interventions to address medical financial hardship, no patterns were observed in the achievement of outcomes across studies based on intensity of intervention. All included studies lacked conceptual clarity regarding hypothesized mechanisms to outcomes. No included studies had long-term follow-up in assessing outcomes. Long-term follow-up may be needed to demonstrate significant changes in objective financial burden, such as OOP expenses from a medical financial hardship intervention. Poor measurement validity also may explain consistent null findings with changes in perception of financial burden/toxicity. There are few measures for financial toxicity or perceptions of medical financial hardship, and existing measures have not been widely validated across different populations.46,47 Notably, some studies did demonstrate significant changes when measuring mental health symptoms with validated instruments specific to mental health. Finally, perhaps intervening on OOP expenses and perceptions of financial burden/toxicity (eg, subjective experience) requires a stronger theoretical approach than evident in included studies.

Certain limitations to this review should be noted. Studies published between the initial search and publication of this article will not be included. Efforts to implement and evaluate medical financial hardship interventions and to identify best practices are not limited to academic institutions and may be undertaken by health care and nonprofit organizations without peer-reviewed publication; these may be underrepresented in the academic published literature. Finally, studies examining medical financial hardship interventions were excluded if they did not describe any evaluation components of the intervention. These intervention studies may nonetheless provide more indirect insights about addressing medical financial hardship and should be considered alongside the findings from this review.

Despite these limitations, this scoping review provides useful insights into future directions.

Overall, research on mitigating medical financial hardship requires conceptual clarity and greater use of behavior change theory to inform interventions.48 There are various definitions of medical financial hardship and financial toxicity, each of which have several potential mechanistic pathways that could be targeted with interventions. This level of ambiguity makes studies that clearly conceptualize a mechanistic model, and test those mechanisms directly, key to moving knowledge forward. Along these lines, consensus on appropriate outcomes also will be critical to move knowledge forward.

Future research should focus on (1) conceptual clarity of the intervention, (2) align outcome measurement and achieve consensus around outcomes, (3) employ rigorous study designs, measurement, and outcome follow-up, and (4) attention to implementation of evidence-based approaches.

Lastly, intervention focus on multiple conceptual components of medical financial hardship (material, psychosocial, behavioral) versus a singular focus may lead to more robust changes in desired outcomes.

Conclusion

This review synthesizes the peer-reviewed literature on content and outcomes of interventions to address medical financial hardship. To date, very few rigorous studies have been generated in this emerging field. This review found variation across studies regarding targets and outcome measurement of intervention, and the studies yielded mixed findings. Future research should focus on conceptual clarity of the intervention, align outcome measurement, and employ more rigorous study designs, measurement, and outcome follow-up.

Authors' Contributions

Dr. Patel: conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Jagsi: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Resnicow: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Smith: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Hammel: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Su: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Griggs: drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Ms. Buchanan: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Ms. Isaacson: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Ms. Torby: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Jagsi has no relevant conflicts. Outside the submitted work, Dr. Jagsi has stock options as compensation for her advisory board role in Equity Quotient, a company that evaluates culture in health care companies; she has received personal fees from Amgen and Vizient and grants for unrelated work from the National Institutes of Health, the Doris Duke Foundation, the Greenwall Foundation, the Komen Foundation, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for the Michigan Radiation Oncology Quality Consortium. She has a contract with Genentech to investigate financial toxicity experiences of breast cancer patients. She has served as an expert witness for Sherinian and Hasso and Dressman Benzinger LaVelle. She is an uncompensated founding member of TIME'S UP Healthcare and a member of the Board of Directors of ASCO.

The coauthors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This work was supported by 5R01DK116715-03-Patel and the Michigan Center for Diabetes and Translational Research (P30DK092926) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the Rogel Cancer Center (P30CA046592) from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1. Starr P. Transformation of defeat: the changing objectives of national health insurance, 1915–1980. Am J Public Health 1982;72:78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA 2016;316:525–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen RA, Kirzinger WK. Financial burden of medical care: a family perspective. NCHS Data Brief 2014;142:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathes T, Jaschinski T, Pieper D. Adherence influencing factors—a systematic review of systematic reviews. Arch Public Health 2014;72:37.. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McHorney CA, Spain CV. Frequency of and reasons for medication non-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008. Health Expect 2011;14:307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108:24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Black CM, Fillit H, Xie L, et al. Economic burden, mortality, and institutionalization in patients newly diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Dis 2018;61:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: a review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:864–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parikh TJ, Helfrich CD, Quinones AR, et al. Cost-related delay in filling prescriptions and health care ratings among Medicare advantage recipients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer 2019;125:1737–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanratty B, Holland P, Jacoby A, Whitehead M. Financial stress and strain associated with terminal cancer—a review of the evidence. Palliat Med 2007;21:595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tucker-Seeley RD, Thorpe RJ. Material-psychosocial-behavioral aspects of financial hardship: a conceptual model for cancer prevention. Gerontologist 2019;59(Suppl 1):S88–S93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caraballo C, Valero-Elizondo J, Khera R, et al. Burden and consequences of financial hardship from medical bills among nonelderly adults with diabetes mellitus in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel MR, Piette JD, Resnicow K, Kowalski-Dobson T, Heisler M. Social determinants of health, cost-related nonadherence, and cost-reducing behaviors among adults with diabetes: findings from the national health interview survey. Med Care 2016;54:796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu Z, Xing W, Zhang X, Hu Y, So WKW. Cancer survivors' experiences with financial toxicity: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Psychooncology 2020;29:945–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barton MK. Bankruptcy linked to early mortality in patients with cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:267–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016 20;34:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deb A, Thornton JD, Sambamoorthi U, Innes K. Direct and indirect cost of managing alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2017;17:189–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Nasir K. Financial toxicity in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States: current state and future directions. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e017793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warraich HJ, Ali HJR, Nasir K. Financial toxicity with cardiovascular disease management: a balancing act for patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e007449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mertz K, Eppler SL, Thomas K, et al. The association of financial distress with disability in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019;27:e522–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Voit A, Cross RK, Bellavance E, Bafford AC. Financial toxicity in Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53:e438–e443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murphy PB, Severance S, Savage S, Obeng-Gyasi S, Timsina LR, Zarzaur BL. Financial toxicity is associated with worse physical and emotional long-term outcomes after traumatic injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019;87:1189–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patel MR, Brown RW, Clark NM. Perceived parent financial burden and asthma outcomes in low-income, urban children. J Urban Health 2013;90:329–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel MR, Caldwell CH, Song PX, Wheeler JR. Patient perceptions of asthma-related financial burden: public vs. private health insurance in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;113:398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Uivarosan D, Bungau S, Tit DM, et al. Financial burden of stroke reflected in a pilot center for the implementation of thrombolysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Witte J, Mehlis B, Surmann B, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desai A, Gyawali B. Financial toxicity of cancer treatment: Moving the discussion from acknowledgement of the problem to identifying solutions. EClinicalMedicine 2020;20:100269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Resnicow K, Patel MR, McLeod MC, Katz SJ, Jagsi R. Physician attitudes about cost consciousness for breast cancer treatment: differences by cancer sub-specialty. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;173:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, et al. Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 2018;124:3668–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108:djv410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Asiamah S, et al. Effect of removing direct payment for health care on utilisation and health outcomes in Ghanaian children: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Friedman NL, et al. Evaluation of a novel financial navigator pilot to address patient concerns about medical care costs. Perm J 2019;23:18-084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bell JF, Krupski A, Joesch JM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intensive care management for disabled Medicaid beneficiaries with high health care costs. Health Serv Res 2015;50:663–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Worley G, Rosenfeld LR, Lipscomb J. Financial counseling for families of children with chronic disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol 1991;33:679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boulware LE, Ephraim PL, Ameling J, et al. Effectiveness of informational decision aids and a live donor financial assistance program on pursuit of live kidney transplants in African American hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 2018;19:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nipp RD, Lee H, Gorton E, et al. Addressing the financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation: longitudinal effects of an equity intervention. Oncologist 2019;24:1048–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Elliott DJ, Robinson EJ, Anthony KB, Stillman PL. Patient-centered outcomes of a value-based insurance design program for patients with diabetes. Popul Health Manag 2013;16:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel MR, Resnicow K, Lang I, Kraus K, Heisler M. Solutions to address diabetes-related financial burden and cost-related nonadherence: results from a pilot study. Health Educ Behav 2018;45:101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract 2018;14:e122–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sadigh G, Gallagher K, Obenchain J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program in brain cancer patients. J Am Coll Radiol 2019;16:1420–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Madore S, Kilbourn K, Valverde P, Borrayo E, Raich P. Feasibility of a psychosocial and patient navigation intervention to improve access to treatment among underserved breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:2085–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watabayashi K, Steelquist J, Overstreet KA, et al. A pilot study of a comprehensive financial navigation program in patients with cancer and caregivers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:1366–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer 2014;120:3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith GL, Volk RJ, Lowenstein LM, et al. ENRICH: Validating a multidimensional patient-reported financial toxicity measure. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:153–153.30457921 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hamel LM, Thompson HS, Albrecht TL, Harper FW. Designing and testing apps to support patients with cancer: looking to behavioral science to lead the way. JMIR Cancer 2019;5:e12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]