Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common and fatal cancers worldwide, and it is also a typical inflammatory cancer. The function of macrophages is very important in the tissue immune microenvironment during inflammatory and carcinogenic transformation. Here, we evaluated the function and mechanism of macrophages in intestinal physiology and in different pathological stages. Furthermore, the role of macrophages in the immune microenvironment of CRC and the influence of the intestinal population and hypoxic environment on macrophage function are summarized. In addition, in the era of tumor immunotherapy, CRC currently has a limited response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors, and we summarize potential therapeutic strategies for targeting tumor-associated macrophages.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Macrophages, Inflammatory transformation, Tumor microenvironment

Core Tip: In this review, we provide a comprehensive review of the research progress of macrophages in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. It is of great significance to discuss the intestinal macrophages under steady-state and inflammatory conditions and tumor-associated macrophages in the immune microenvironment. With the research on macrophages in intestinal inflammation and tumor diseases, targeted macrophage therapy will benefit patients with intestinal inflammation or colorectal cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common malignant tumor. Changes in bowel habits and stool characteristics, abdominal discomfort, thigh lumps, intestinal obstruction, anemia, and other systemic symptoms can be related to disease progression, but no obvious clinical manifestations are present in the early stage[1]. According to the latest statistics by the American Cancer Society, the incidence and mortality of CRC rank third among all malignant tumors[2]. The latest statistics on cancer from China show that CRC has become the third most common cancer in terms of incidence, with the fifth highest mortality rate[1]. Most patients are already in a moderate or advanced stage when they are diagnosed, which imposes a great burden on their family and society. Therefore, early detection and screening, correct diagnosis of CRC, and early intervention and treatment to slow down the progression of the disease are particularly important. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have shown that macrophages play an important role in the occurrence and development of CRC. This article will review the research status of intestinal macrophages, the role and regulatory factors of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and the research progress related to targeted TAM therapy to provide new ideas for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and CRC.

INTESTINAL MACROPHAGES

Macrophages play an important role in intestinal inflammatory immunity, injury repair, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and tumor development. Traditionally, macrophages differentiate from monocytes and play an immunomodulatory role[3]. Further study found that there are two main sources of intestinal macrophages: Gut-resident macrophages (gMacs) and monocytes (monocyte-derived macrophages). Resident tissue macrophages (RTMs) are derived from embryonic precursors, which accumulate in tissues before birth and are maintained by renewal in adulthood[4]. In contrast to the self-renewal and self-maintenance of Kupffer cells and microglia, whether the gMac population is maintained by contributions from mononuclear macrophages is not clear. Although traditional studies have concluded that embryonic macrophages in the intestinal tract are replaced by bone marrow-derived Ly6Chi monocytes in a microorganism-dependent manner, an experiment evaluating intestinal macrophage heterogeneity determined that the self-sustaining population of macrophages is produced by embryonic precursors and adult bone marrow-derived monocytes, which persist throughout adulthood, and that these cells settle in specific niches, including the vascular system, submucosa, muscular plexus, sites of Pan’s cells, and Peyer’s patches. Single-cell analysis has shown that gMacs have a unique transcriptional profile, which supports the vascular structure and permeability in the lamina propria (LP) and also regulates neuronal function and intestinal peristalsis in the LP and muscularis externa[5].

Origin and differentiation of intestinal macrophages

The gene expression profiles of macrophages in tissues and sites vary[6]. Although no study has shown that the origin changes the macrophage life span or biological functions[7], recent studies have shown that macrophage origin influences the gene expression profile[8,9]. After treatment with chlorophosphate liposomes, mice with a monocyte-derived Kupffer cell population reacted more acutely to excessive paracetamol than mice with an intact embryonic Kupffer cell population. However, this functional difference might also be attributed to tissues because the difference disappeared after monocyte-derived Kupffer cells were placed in the liver for 60 d without an overdose of acetaminophen[10]. Epigenetic analyses show that macrophages of different cell origins are relatively similar and are mainly influenced by living tissues. There are some epigenetic differences among macrophages derived from different precursors, which may be related to the changes in the local tissue environment caused by whole body irradiation[8]. To date, it is necessary to explore the differences in epigenetics and function, not only origin, among different macrophages in detail.

Surface markers of intestinal macrophages

The unique transcriptome of tissue macrophages endows different functions to these cells and allows them to play specific biological functions in the microenvironment[11-13].

Some of the main challenges in this field are to identify intestinal macrophages and their subgroup markers and determine how to regulate these cells to meet the biological functional requirements of their living environment. In mice, F4/80 is the best and most commonly used marker to identify macrophages[14]. However, conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) and eosinophils can also express F4/80[15,16]. Intestinal macrophages highly express CD11C and MHCII, which can identify cDCs and are related to the polarization of M1 macrophages[17]. However, intestinal macrophages also express CD206 and CD163 but do not express arginine[18]. Therefore, intestinal macrophages are not suitable for M1 and M2 typing. The identification of intestinal macrophages requires a multiparameter method.

gMacs and cDCs can be distinguished by CX3CR1 and CD64 in combination with CD11C and MHCII. Compared with cDCs, gMacs highly express the chemokine receptor CX3CR1[18,19], which is mainly located in the LP of the intestine, connective tissue under the skin, intestinal wall, submucosa, and muscle[19-22]. CX3CR1 is a key regulator of macrophage function in the inflammatory state[23,24], while the CX3CR1+ myeloid cell-Treg axis plays a central role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis[25]. CX3CR1+ macrophages resident in the mucosa can recruit and activate antigen-presenting cells displaying epitopes to CD4+ T cells and B cells at an invasion site[26], effectively inhibiting the production of IL-17 by CD4+ T cells by promoting Treg activity dependent on IFN-β[27]. Although there are reports that IFN-β can inhibit the production of IL-17 in mouse and human CD4+ T cells, the mechanism is not clear[28,29]. The expression of CD11c differs among gMacs at different sites; CD11c+ gMacs are enriched in the LP, while CD11c-/loCX3CR1hi gMacs are enriched in the muscle[29,30]. LP gMacs actively participate in host defense, maintain the integrity of the barrier, have high phagocytic activity, promote the constitutive secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10), maintain FoxP3+ T cells, and protect mucous membranes[31]. The development and survival of CD64+ mononuclear phagocytes are highly dependent on colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1), while CD64-CD11c+ MHC II+ mononuclear phagocytes, which are highly dependent on the CDC-specific growth factor FLT3[32], migrate to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and participate in the initiation of T cell responses in a CCR7-dependent manner[33,34]. An experiment evaluating Tim-4- and CD4-labeled gMacs also provided evidence for the development and heterogeneity of intestinal macrophages[35]. However, the function of these cells is not clear. Tracking CD64+ gMacs with YFP in hybrid offspring from Cx3cr1CreERT2 mice and Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice successfully identified self-sustaining gMac subsets[5].

Intestinal macrophages under steady-state and inflammatory conditions

Intestinal macrophages are the main participants in establishing and maintaining intestinal homeostasis. gMacs produce a variety of cytokines and mediators (PGE2, BMP2, WNT ligand, etc.) to maintain the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells and the physiology of intestinal neurons and endothelial cells[36]. gMacs also promote the expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells by producing IL-10, prevent inflammatory reactions in the microbial environment, and support intestinal tolerance[37]. Intrinsic receptors (including LPS (CD14), fcα (CD89), fcγ (CD64, CD32, and CD16), Cr3 (CD11b/CD18), and Cr4 (CD11c/CD18)) are not expressed in gMacs[38]. gMacs also lack trigger receptors expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1)[39], which is a cell-surface molecule expressed on neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in the peripheral blood. The activation reaction mediated by TREM-1 can increase the expression of proinflammatory mediators (such as TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6) and upregulate the levels of cell-surface molecules (CD40, CD86, and CD32)[40], leading to oxidative stress. Therefore, when intestinal macrophages play an effective scavenging role, they usually do not induce inflammation or damage intestinal homeostasis.

Monocytes and macrophages can induce cytotoxicity and proinflammatory mediators, eliminate apoptotic and damaged cells, and promote tumor progression when tissue is damaged[41,42]. The CCL2-CCR2 axis plays an important role in the migration of monocytes from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood. CCR2-deficient and CCR2-positive mice have been widely used in the study of monocytes and monocyte-derived cells in the development of tissue damage and elimination of pathogens[43,44]. During inflammation, the transportation of CCR2-/- monocytes to the small intestine is obviously decreased, but interestingly, the recruitment of circulating monocytes to other tissues, such as the liver and spleen, is not affected by CCR2 deficiency[45]. Silencing CCR2 also significantly reduces repaglinide tolerance, which may be related to the stability of β-catenin regulated by AKT/GSK3[46]. Recent studies have shown that the exogenous antiaging factor Klotho can inhibit the progression of CRC by inhibiting the expression of CCL2[47]. The chemokines CCL2 and CXCL12 synergistically induce M2 macrophage polarization[19]. Targeting CCL2/CCR2 without affecting transport to other tissues provides new hope for the treatment of CRC.

Under steady-state conditions, monocytes gradually differentiate into CX3CR1hi macrophages that express genes related to the function of tolerant macrophages. According to the expression of Ly6C and MHCII, monocytes and macrophages in the small intestine can be divided into three subgroups: Ly6C+ MHCII-, Ly6C+ MHCII+, and Ly6C-MHCII+. Based on the expression of CX3CR1, Ly6C-MHCII+ cells can be divided into CX3CR1int and CX3CR1hi cells, which can reflect the different stages of monocyte differentiation in the small intestine and colon[18,48,49]. Transcriptomic analysis also shows significant differences in gene expression among different stages. In addition to CX3CR1, the expression of CD64, CD11c, and CD206 increases with the development of Ly6C+ MHCII monocytes into small intestinal Ly6C-MHCII+ CX3CR1hi macrophages. In contrast, monocytes immediately adapt to different expression patterns in a TREM-1-dependent manner after they enter the intestine in an inflammatory state. Inflammation fundamentally changes the kinetics and mode of monocyte differentiation in tissues[45]. In contrast to intestinal homeostasis, inflammatory injury results in the accumulation of Ly6C+ monocytes in large numbers. In a study, the expression of CD64 was high, while that of CX3CR1 was always low. On the third day of inflammation, CD64+ Ly6C−MHCIIint monocytes were divided into two subsets: MHCIIhiCX3CR1int (seen in the inflamed colon)[50]) and MHCII. In the Ly6C−MHCIIint population, the CX3CR1 expression level was slightly higher than that in the Ly6C+MHCII− and Ly6C+MHCIIint populations but lower than that in Ly6C−MHCIIhi macrophages. These cells may represent the intermediate stage of monocyte differentiation in intestinal inflammation. However, there was no differential expression of genes with enhanced expression during homeostasis in the inflammatory intestinal environment. The levels of some inflammation-related genes gradually decreased, while that of CD169 increased significantly.

Studies have shown that macrophages play a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD and that these cells are present throughout the occurrence, progression, and recovery of intestinal inflammation in both humans[18,51] and mice[52,53]. Macrophages regulate the progression of colitis by producing proinflammatory factors, such as TNF, IL-1β, IL-23, IL-6, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and NO[50]. Intestinal macrophages release IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, and TGF-β and mediate the Th17 immune response, which plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD[54].

Intestinal flora and intestinal macrophages

The intestinal flora maintains the integrity of the epithelial barrier, shapes the mucosal system, and balances host defense through metabolites, its own components, and adhesion to host cells. The metabolites and bacterial components of intestinal microorganisms can send signals to immune cells and regulate intestinal immunity.

Dietary fiber can directly enter the cecum and colon, where it can be fermented and metabolized by microorganisms to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)[55]. SCFAs are the energy source of colon cells and regulate the physiological functions of intestinal epithelial cells and intestinal immune cells. SCFA-mediated histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition has anti-inflammatory effects. Butyrate inhibits the differentiation of dendritic cells and proinflammatory macrophage effectors from bone marrow stem cells in the LP through HDACs and reduces the immune system response to beneficial symbionts[56]. In addition, macrophages and dendritic cells develop anti-inflammatory properties under the stimulation of butyrate-mediated GPR109A signaling. Foxp3+ Tregs and CD4+ T cells accumulate in the colon, activating immunosuppressive mechanisms and maintaining intestinal homeostasis[57].

CX3CR1hi mononuclear phagocytes do not migrate during intestinal homeostasis[58]. Symbiotic bacteria and pathogenic bacteria can regulate the host immune response by activating TLR pathways in the intestine. TLR/MyD88 signal transduction limits the transport of CX3CR1hi monocytic phagocytes from the LP to the MLNs[59]. MyD88 deficiency and malnutrition lead to the migration of CX3CR1hi mononuclear phagocytes to the MLNs, enhance the Th1 response to noninvasive pathogens in the MLNs, and increase IgA. TLR signaling mediated by the intestinal microbiota can regulate IL-10 production by intestinal macrophages[60]. The probiotic Clostridium butyricum promotes the accumulation of F4/80+ CD11b+ CD11c macrophages in the inflamed intestinal mucosa through the TLR2/MyD88 signaling pathway and the production of IL-10 and prevents colitis in mice[52]. It has also been shown that the LPS/TLR4 pathway can trigger CCL2 and promote the accumulation of monocyte-like macrophages (MLMs)[61], which can produce IL-1β, promote Th17 cell expansion, aggravate malnutrition and inflammation, and lead to tumor progression tumor formation[62].

TUMOR-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGES

Peripheral mononuclear cells or RTMs infiltrate near tumor masses or into tumor tissue to form TAMs, which are the main inflammatory cells in the tumor matrix[63].

Recent studies have shown that TAMs originate from RTMs and newly recruited monocytes[64]. The evolution of cells was inferred by the RNA velocity of single cells, and it was confirmed that FCN1+ monocyte-like cells with tumor enrichment may be the precursors of TAMs and have a tumor-promoting transcriptional program. Transcriptional tracking of macrophages[65,66] indicated that FCN1+ monocyte-like cells produce C1QC+ TAMs and SPP1+ TAMs from different RTMs. C1QC+ TAMs may develop through IL1B+ RTMs and express genes involved in phagocytosis and antigen presentation. SPP1+ TAMs are linked to NLRP3+ RTMs, which are rich in angiogenesis-regulating factors and have specific enrichment of rectal adenocarcinoma and metastatic liver cancer pathways, suggesting that SPP1+ TAMs can promote tumor development and metastasis[67]. However, these subsets do not conform to the M1 and M2 classification of TAMs[68].

Dual role of tumor-associated macrophages

The plasticity of macrophages determines the polarization state, and the function of macrophages varies with the macrophage phenotype and tumor type[69,70]. The phenotype of polarized TAMs depends on the stage of tumor progression: In the early stage of cancer, that is, the stage of tumor elimination with local chronic inflammation in the tumor, cytokines and chemokines induce TAM polarization to the M1 type[71], which can induce an inflammatory response and phagocytosis[72]. Subsequently, M2 polarization occurs, and these cells secrete cytokines or chemokines and inhibit the antitumor immune response with changes in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and external stimuli as the tumor progresses[73].

In most human cancers, a large number of TAMs are significantly related to a poor disease prognosis, and basic research also shows that macrophages have a tumor-promoting function[74,75]. A study of 120 CRC patients with liver metastasis showed that M1 macrophages were negatively correlated with tumor metastasis, while M2 macrophages were positively correlated with lymph node and liver metastasis and the degree of tumor differentiation. M2 macrophages and the M2/M1 ratio can be used as accurate predictors of liver metastasis in CRC patients[76]. Based on an analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from 360 CRC patients at the European Oncology Center, polarized circulating mononuclear cells can be used as biomarkers for CRC diagnosis and may be useful for follow-up and treatment evaluation[77].

M1 macrophages have high expression of major histocompatibility complex-II (MHC-II), exhibiting an effective antigen-presenting ability, and secrete proinflammatory factors and immunostimulatory cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-23, CXCL9, and CXCL10; thus, these cells function to kill bacteria and viruses, promote TH1 cell polarization and recruitment, and enhance the type 1 immune response[78]. M2 macrophages express a large number of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10), immune mediators (TGF-β), prostaglandins, indoleamines, growth factors (VEGF), chemokines (CCL2, CCL17, and CCL22), and matrix metallopeptidases; thus, M2 macrophages participate in anti-inflammatory activity, tissue remodeling, wound healing, angiogenesis, and tumor development[79]. Prior research and a meta-analysis showed that M1 macrophages prevent the occurrence and development of tumors, while M2 macrophages promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion, enhance angiogenesis, and accelerate tumor growth and metastasis[80,81]. However, CRC exhibits a paradox in the function of specific groups of immune cells. A study of 205 CRC patients showed that there were a large number of infiltrating CD163+ macrophages in the CRC patients with less lymphatic metastasis and a lower tumor grade, and the patients with more CD163+ macrophages exhibited a survival benefit. Unexpectedly, iNOS+ macrophages did not show any advantage[82]. In CRC stage III patients, high TAM levels are related to a better prognosis in patients who receive chemotherapy but not to the prognosis of patients who do not receive chemotherapy[83].

The type 1 immune response can inhibit the progression of CRC[84]. However, the molecular mechanism regulating antitumor activity and promoting tumor inflammation in CRC is still unclear. NF-κB is a key regulator of inflammation, and its activation and inhibition are controlled at a variety of regulatory levels, which can regulate the function of macrophages[85]. NF-κB p50 promotes the transcriptional program of M2 macrophages[86]. In a model of colitis-associated cancer (CAC) induced by AOM combined with DSS[87], the number of tumor lesions was significantly decreased in p50-/- mice, accompanied by increases in Th1/M1 inflammatory genes (Il12b, Il27, Ebi3, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Nos2, and Ifng) and gene products (TNF-α, IL12, and iNOS). An analysis of CRC stage II/III patients showed that nuclear accumulation of p50 in TAMs inhibited Th1 cell/M1 macrophage-dependent antitumor reactions, which was related to the expression of M2 macrophage-related genes (IL10, TGF-β, Ccl17, and Ccl22) and increases in tumor-promoting genes (TNF-α and IL23). The expression of NF-κB p50 plays important roles in the development of colitis and CAC, but negative regulators (including p50) that only block inflammatory reactions also cause adverse reactions[88]. Type 1 proinflammatory factors (IL-12 and CXCL-10) can offset adverse reactions and restore antitumor immunity, which still needs to be evaluated in large-scale clinical studies.

Tumor microenvironment and tumor-related macrophages

The TME is composed of cellular components and noncellular components. The cellular components include cancer cells, mesenchymal cells, infiltrating immune cells, and tumor-related fibroblasts, while the noncellular components are composed of cytokines and chemokines[89]. The TME can regulate the infiltration of macrophages and promote the development of CRC through the synergistic effects of cytokines and cells.

Chemotactic factors

The chemokine family includes important signaling molecules in the TME. CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL8, and CCL22 are highly expressed in various tumors and participate in the action of TAMs[90]. Recent studies have shown that CCL5 plays an important role in the development of CRC and that CD8+ T cell infiltration is significantly increased in the primary colorectal tumor site of CCL5-/- mice[91]. In vivo and in vitro experiments show that CCL5 secreted by macrophages mediates the formation of the p65/STAT3 complex, induces upregulation of PD-L1, inhibits the CD8+ T cell response, and promotes immune escape and CRC development in cancer cells. Macrophage infiltration decreases significantly after anti-CCL5 and C-15 treatment[92]. Inhibition of the CCL5-CCR5 axis is expected to be a new cancer treatment strategy[93].

CCL2 plays an important role in regulating the TME[94]. CCL22 secreted by tumor cells plays a pivotal role in immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment by binding with Foxp3+ Tregs, which highly express CCR4[95]. CCL22 was recently identified to have potential as a molecular biomarker for evaluating chemotherapy and tumor progression. Moreover, M2 macrophages transfer CCL22 to cancer cells and contribute to the development of 5-FU resistance and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program in CRC cells[96]. CCL22 and its receptor CCR4 can also promote the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells[97], and M2 macrophage-derived CCL22 can enhance the migration of tumor cells in patients with liver cancer[98].

Hypoxia

Hypoxia in the TME can lead to angiogenesis, EMT, TGF-β signal transduction, and increases in tumor cell migration and metastasis[99,100]. Tissue hypoxia affects TAMs in two ways: Hypoxia can induce tumor cells and the stroma to produce monocyte-recruiting factors (CCL2, CCL5, CXCL12, CSF1, and VEGF). After monocytes are recruited into hypoxic areas, the expression of cytokine receptors is downregulated, and TAMs are trapped in the hypoxic microenvironment[101]. Furthermore, macrophages capture oxygen through hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs), and decreased expression of ARG1 and immunosuppressive activity occur in vitro in the absence of HIF1α[102]. HIF2α deficiency weakens macrophage infiltration and cytokine production[103]. TAMs secrete “vascular factors” (VEGF, Sema3A, MMP2, and MMP9)[104]. TAMs in NrpL/L mice fail to enter the hypoxic tumor area, resulting in decreased angiogenesis and a weakened immunosuppressive ability, which leads to decreased vascular branches and a Th1 cell/CTL-mediated antitumor immune response[105]. Th1 cells release TAMs recruited by IFN-γ and other cytokines, initiating feed-forward circulation and enhancing antitumor immunity[106]. Reduced angiogenesis and tumor perfusion also trigger feed-forward circulation, resulting in hypoxia and recruitment of more TAMs[107]. However, when Nrp1 is absent, these TAMs will not enter the hypoxic area and thus maintain the antitumor phenotype, which may explain observations made with clinical tumor biopsies: A higher number of TAMs are not necessarily related to a poor prognosis, and the clinical correlations between TAMs in different locations and the prognosis and survival of tumor patients are different[108].

Cluster analysis showed that the degree of M2 macrophage infiltration increased obviously under hypoxia but that the degree of M1 macrophage infiltration did not increase. The levels of CD163+ and CD206+ macrophages in the hypoxic subgroup were much higher than those in the normoxic subgroup. Hypoxia activates the RAS signaling pathway independently of KRAS mutation and activates the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway by increasing the infiltration of M2 macrophages, thus regulating the progression of CRC[109]. The effect of lactic acid on macrophages under normoxic conditions is weak, but the combination of hypoxia and lactic acid can significantly promote the M2 polarization of macrophages through HIF-1, Hedgehog, and mTOR pathways[110].

Metabolism of tumor-related macrophages

Tumor metabolism plays important roles in promoting tumor growth and metastasis[111,112]. Amino acids and fatty acids provide substrates for tumor cells to produce metabolites and energy to meet the metabolic needs for proliferation and TME development. M1 macrophages mainly produce ATP through glycolysis, while M2 macrophages preferentially obtain energy through the oxidative TCA cycle coupled with oxidative phosphorylation. Compared with M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages have opposing arginine metabolism[113]. Increasing evidence shows that the lipid metabolism of immune cells, especially that of TAMs, plays important roles in the occurrence and development of tumors. In recent years, research on the process of lipid metabolism in TAMs has focused on the regulatory mechanisms of lipid metabolism-related enzymes.

In vitro and in vivo mouse experiments have shown that[114] the level of the lipolytic coactivator ABHD5 in CRC-associated macrophages is increased significantly, while that of monoacylcerolipase (MGLL) is decreased. ABHD5 can promote the growth of CRC by inhibiting the production of spermidine, which depends on SRM in TAMs. MGLL deficiency may lead to an increase in fatty acid glycerides[115]. The upregulation of ABHD5 may lead to a decrease in triglycerides and an increase in diglyceride[116]. A transplanted tumor model including mouse myeloid cells overexpressing ABHD5 showed that TAM ABHD5 could inhibit peritoneal and pulmonary metastasis of tumor cells (MC-38 and B-16 cells) and that macrophage ABHD5 regulated the migration and metastasis of tumor cells through the IL-1β/NF-κB/MMP pathway. The MMTV-PyMT mouse model of spontaneous breast cancer also verified that macrophage ABHD5 could inhibit lung metastasis of spontaneous breast cancer[114].

Phospholipid metabolism can affect the TME by regulating tumor-related immune cells[117-119]. The lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase β-AGPT4 is highly expressed in CRC patients, and the survival rate of CRC patients is reduced with high expression of AGPT4. Agpat4 knockdown can increase the expression of the proinflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α by increasing the LPA content, inducing polarization of M1 macrophages and enhancing antitumor effects[124]. An animal experiment performed with mice treated with ethoxymethane and sodium dextran sulfate showed that[120] Lipin-1, a phospholipid acid phosphatase, could promote the infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages by participating in the production of CXCL1/2 (the infiltration of other immune cells, such as T cells, was not changed), upregulating the level of Nos2/iNOS and promoting dysplasia-cancer metastasis in colorectal tumors.

Targeting tumor-related macrophages

A large number of studies have proven the role of the CSF1-CSF1R axis in TAM recruitment, and inhibition of CSF1-CSF1R signaling leads to apoptosis and death in most TAMs[121]. CSF1-CSF1R blockers can improve the efficacy of various immunotherapeutic methods, including administration of CD40 agonists or PD1 or cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) antagonists and adoptive T cell therapy[122-124]. Anti-CSF1R treatment can specifically deplete C1QC+ TAMs but cannot deplete the entire SPP1+ macrophage population, which can promote tumor growth. This finding may explain why anti-CSFR1 antibodies are not effective as monotherapies in tumor patients[67]. CSF1R inhibition combined with radiotherapy or chemotherapy can improve the T cell response and enhance the therapeutic effect in a large number of animal models[125-127].

CXCR4-CXCL12 is an important signal transduction axis involved in TAM recruitment, which can promote tumor invasion and regeneration[128]. Monocytes secrete the chemokine CXCL12 and express the receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7, which lead to autocrine/paracrine loops; promote the differentiation of different types of macrophages; enhance the expression of CD4, CD14, and CD163; and decrease the ability to stimulate antigen-specific T lymphocyte responses[129]. The CXCR4 antagonist peptide R (PEP R) can reduce the growth of HCT116 cells and improve the therapeutic effect of conventional chemotherapy (CT) or chemoradiotherapy (RT-CT). This effect depends on the decreases in cell growth and mesenchymal stem cell transformation induced by CT/RT-CT[130]. PEPR can also target CXCR4+ stromal cells and further decrease EMT and chemoresistance[131]. Combined administration of PEP R and the CXCL12 antagonist noxa-012 can improve the function of anti-PD1 antibodies in mice with CRC[132].

Macrophages in different functional states maintain cell activity through different metabolic pathways and metabolites[133]. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling via mTORC1 and mTORC2 plays a central role in tracking nutrition, oxygen, and metabolites to guide the metabolic processes of macrophages[134]. Rapamycin (an mTORC1 inhibitor) can stimulate M1 macrophages and cause them to have an antitumor effect[135]. mTORC1 inhibitors can reduce immunosuppressive inflammation and tumor occurrence. Rad001 (a rapamycin derivative) ameliorates CRC induced by AOM/DSS in mice by limiting inflammation[136]. Signaling molecules (such as PI3Kγ, Akt, and PTEN) upstream of mTOR also participate in the polarization and remodeling of TAMs, making the mTOR pathway a potential anticancer target[137]. The expression of a PI3Kγ inhibitor (PTEN) or silencing of AKT1 can also promote the polarization of antitumor M1 macrophages[138].

Iron participates in the interaction between tumor cells and their environment[139]. Unlike M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages express iron transporters and downregulate ferritin and heme oxygenase, all of which promote iron release[140]. In addition, conditioned medium from M2 macrophages can promote the proliferation of tumor cells, while iron chelation can inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells[141]. Recent studies have shown that iron chelation can reverse the iron-processing function of M2 macrophages, switching from iron release to chelation, and block the tumor-promoting effect of M2 macrophages[142].

CONCLUSION

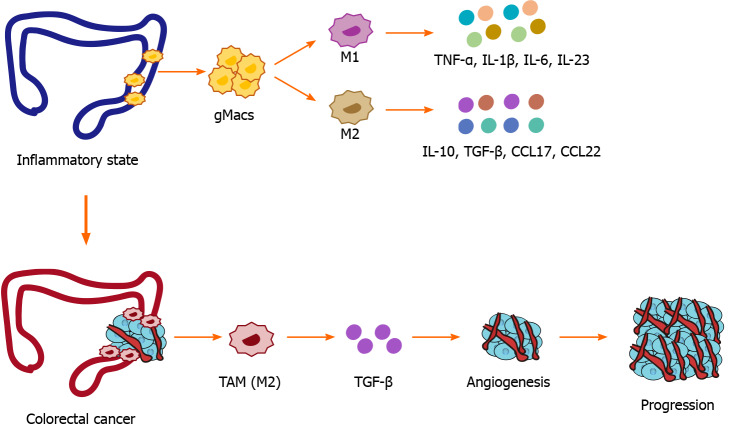

Macrophages play a crucial role in the occurrence and development of CRC. As the disease progresses, macrophages tend to differentiate into different subsets that play different biological functions. The dual functions of TAMs and the regulatory effects of the TME on TAMs are worthy of further study. Subsets of macrophages cannot be simply classified according to the traditional M1 and M2 phenotypes. Single-cell technology will benefit the phenotypic classification of macrophages and provide further insights into their function (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Etiology of macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. gMacs: Gut-resident macrophages; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor; IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-23: Interleukin-23; IL-10: Interleukin-10; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-beta; CCL17: C-C motif chemokine 22; CCL22: C-C motif chemokine 22.

The complexity of tumors highlights the advantages of combined therapeutic approaches. The clinical application of immune checkpoint inhibitors such as PD-1 and PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies provide additional evidence for tumor immunotherapy, and studies have shown that targeting tumor-associated macrophages can significantly improve the efficacy of existing immunotherapy. Future research needs to have a clear understanding of drug mechanisms of action and drug resistance mechanisms to design effective combined therapies. In addition, more clinical data are needed to clarify the relationships between macrophage infiltration or phenotype and the prognosis of patients and to guide whether TAM antagonists can be used in patients to overcome immunotherapy resistance. Despite these challenges, the use of macrophages to improve the prognosis of cancer patients still has great potential.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors who contributed their efforts in this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review started: May 17, 2021

First decision: July 14, 2021

Article in press: August 25, 2021

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lieto E S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Lu Lu, Institute of Digestive Diseases, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200032, China.

Yu-Jing Liu, Institute of Digestive Diseases, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200032, China.

Pei-Qiu Cheng, Institute of Digestive Diseases, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200032, China.

Dan Hu, Shanghai Pudong New Area Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200120, China.

Han-Chen Xu, Institute of Digestive Diseases, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200032, China; Shanghai Pudong New Area Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200120, China.

Guang Ji, Institute of Digestive Diseases, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200032, China. jiliver@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain CC, Mowat AM. Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2014;260:102–117. doi: 10.1111/imr.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume DA, Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, Jung S. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Schepper S, Verheijden S, Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Viola MF, Boesmans W, Stakenborg N, Voytyuk I, Schmidt I, Boeckx B, Dierckx de Casterlé I, Baekelandt V, Gonzalez Dominguez E, Mack M, Depoortere I, De Strooper B, Sprangers B, Himmelreich U, Soenen S, Guilliams M, Vanden Berghe P, Jones E, Lambrechts D, Boeckxstaens G. Self-Maintaining Gut Macrophages Are Essential for Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell. 2018;175:400–415.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guilliams M, Scott CL. Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages? Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:451–460. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perdiguero EG, Geissmann F. The development and maintenance of resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:2–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott CL, Zheng F, De Baetselier P, Martens L, Saeys Y, De Prijck S, Lippens S, Abels C, Schoonooghe S, Raes G, Devoogdt N, Lambrecht BN, Beschin A, Guilliams M. Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beattie L, Sawtell A, Mann J, Frame TCM, Teal B, de Labastida Rivera F, Brown N, Walwyn-Brown K, Moore JWJ, MacDonald S, Lim EK, Dalton JE, Engwerda CR, MacDonald KP, Kaye PM. Bone marrow-derived and resident liver macrophages display unique transcriptomic signatures but similar biological functions. J Hepatol. 2016;65:758–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David BA, Rezende RM, Antunes MM, Santos MM, Freitas Lopes MA, Diniz AB, Sousa Pereira RV, Marchesi SC, Alvarenga DM, Nakagaki BN, Araújo AM, Dos Reis DS, Rocha RM, Marques PE, Lee WY, Deniset J, Liew PX, Rubino S, Cox L, Pinho V, Cunha TM, Fernandes GR, Oliveira AG, Teixeira MM, Kubes P, Menezes GB. Combination of Mass Cytometry and Imaging Analysis Reveals Origin, Location, and Functional Repopulation of Liver Myeloid Cells in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:1176–1191. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto D, Miller J, Merad M. Dendritic cell and macrophage heterogeneity in vivo. Immunity. 2011;35:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, Chow A, Elpek KG, Gordonov S, Mazloom AR, Ma'ayan A, Chua WJ, Hansen TH, Turley SJ, Merad M, Randolph GJ Immunological Genome Consortium. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hume DA, Perry VH, Gordon S. The mononuclear phagocyte system of the mouse defined by immunohistochemical localisation of antigen F4/80: macrophages associated with epithelia. Anat Rec. 1984;210:503–512. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGarry MP, Stewart CC. Murine eosinophil granulocytes bind the murine macrophage-monocyte specific monoclonal antibody F4/80. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:471–478. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pabst O, Bernhardt G. The puzzle of intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells and macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2107–2111. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, Gudjonsson S, Jansson O, Grip O, Guilliams M, Malissen B, Agace WW, Mowat AM. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:498–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabanyi I, Muller PA, Feighery L, Oliveira TY, Costa-Pinto FA, Mucida D. Neuro-immune Interactions Drive Tissue Programming in Intestinal Macrophages. Cell. 2016;164:378–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Hardt WD, Shakhar G, Jung S. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, Liu K, Jakubzick C, Ingersoll MA, Leboeuf M, Stanley ER, Nussenzweig M, Lira SA, Randolph GJ, Merad M. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortha A, Chudnovskiy A, Hashimoto D, Bogunovic M, Spencer SP, Belkaid Y, Merad M. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimura S, Oka T, Sugaya M, Sato S. CX3CR1 deficiency attenuates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation with decreased M1 macrophages. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;82:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnelly DJ, Longbrake EE, Shawler TM, Kigerl KA, Lai W, Tovar CA, Ransohoff RM, Popovich PG. Deficient CX3CR1 signaling promotes recovery after mouse spinal cord injury by limiting the recruitment and activation of Ly6Clo/iNOS+ macrophages. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9910–9922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2114-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity. 2009;31:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koscsó B, Kurapati S, Rodrigues RR, Nedjic J, Gowda K, Shin C, Soni C, Ashraf AZ, Purushothaman I, Palisoc M, Xu S, Sun H, Chodisetti SB, Lin E, Mack M, Kawasawa YI, He P, Rahman ZSM, Aifantis I, Shulzhenko N, Morgun A, Bogunovic M. Gut-resident CX3CR1hi macrophages induce tertiary lymphoid structures and IgA response in situ. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu T, Li Q, Egilmez NK. IFNβ-producing CX3CR1+ macrophages promote T-regulatory cell expansion and tumor growth in the APCmin/+ / Bacteroides fragilis colon cancer model. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1665975. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1665975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Yuan S, Cheng G, Guo B. Type I IFN promotes IL-10 production from T cells to suppress Th17 cells and Th17-associated autoimmune inflammation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao Y, Zhang X, Chopra M, Kim MJ, Buch KR, Kong D, Jin J, Tang Y, Zhu H, Jewells V, Markovic-Plese S. The role of endogenous IFN-β in the regulation of Th17 responses in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2014;192:5610–5617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller PA, Koscsó B, Rajani GM, Stevanovic K, Berres ML, Hashimoto D, Mortha A, Leboeuf M, Li XM, Mucida D, Stanley ER, Dahan S, Margolis KG, Gershon MD, Merad M, Bogunovic M. Crosstalk between muscularis macrophages and enteric neurons regulates gastrointestinal motility. Cell. 2014;158:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zigmond E, Bernshtein B, Friedlander G, Walker CR, Yona S, Kim KW, Brenner O, Krauthgamer R, Varol C, Müller W, Jung S. Macrophage-restricted interleukin-10 receptor deficiency, but not IL-10 deficiency, causes severe spontaneous colitis. Immunity. 2014;40:720–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott CL, Bain CC, Wright PB, Sichien D, Kotarsky K, Persson EK, Luda K, Guilliams M, Lambrecht BN, Agace WW, Milling SW, Mowat AM. CCR2(+)CD103(-) intestinal dendritic cells develop from DC-committed precursors and induce interleukin-17 production by T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:327–339. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerovic V, Houston SA, Scott CL, Aumeunier A, Yrlid U, Mowat AM, Milling SW. Intestinal CD103(-) dendritic cells migrate in lymph and prime effector T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:104–113. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw TN, Houston SA, Wemyss K, Bridgeman HM, Barbera TA, Zangerle-Murray T, Strangward P, Ridley AJL, Wang P, Tamoutounour S, Allen JE, Konkel JE, Grainger JR. Tissue-resident macrophages in the intestine are long lived and defined by Tim-4 and CD4 expression. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1507–1518. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai Y, Jia X, Huang F, Zhang R, Dong L, Liu L, Zhang M. Structural elucidation, anti-inflammatory activity and intestinal barrier protection of longan pulp polysaccharide LPIIa. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;246:116532. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mowat AM. To respond or not to respond - a personal perspective of intestinal tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:405–415. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, Smith PD. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schenk M, Bouchon A, Birrer S, Colonna M, Mueller C. Macrophages expressing triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 are underrepresented in the human intestine. J Immunol. 2005;174:517–524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F, Liu S, Wu S, Zhu Q, Ou G, Liu C, Wang Y, Liao Y, Sun Z. Blocking TREM-1 signaling prolongs survival of mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced sepsis. Cell Immunol. 2012;272:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskin DL, Sunil VR, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Macrophages and tissue injury: agents of defense or destruction? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon S, Plüddemann A, Martinez Estrada F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol Rev. 2014;262:36–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiong H, Carter RA, Leiner IM, Tang YW, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Pamer EG. Distinct Contributions of Neutrophils and CCR2+ Monocytes to Pulmonary Clearance of Different Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains. Infect Immun. 2015;83:3418–3427. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00678-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coates BM, Staricha KL, Koch CM, Cheng Y, Shumaker DK, Budinger GRS, Perlman H, Misharin AV, Ridge KM. Inflammatory Monocytes Drive Influenza A Virus-Mediated Lung Injury in Juvenile Mice. J Immunol. 2018;200:2391–2404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desalegn G, Pabst O. Inflammation triggers immediate rather than progressive changes in monocyte differentiation in the small intestine. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3229. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11148-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ou B, Cheng X, Xu Z, Chen C, Shen X, Zhao J, Lu A. A positive feedback loop of β-catenin/CCR2 axis promotes regorafenib resistance in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:643. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1906-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Pan J, Pan X, Wu L, Bian J, Lin Z, Xue M, Su T, Lai S, Chen F, Ge Q, Chen L, Ye S, Zhu Y, Chen S, Wang L. Klotho-mediated targeting of CCL2 suppresses the induction of colorectal cancer progression by stromal cell senescent microenvironments. Mol Oncol. 2019;13:2460–2475. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamoutounour S, Henri S, Lelouard H, de Bovis B, de Haar C, van der Woude CJ, Woltman AM, Reyal Y, Bonnet D, Sichien D, Bain CC, Mowat AM, Reis e Sousa C, Poulin LF, Malissen B, Guilliams M. CD64 distinguishes macrophages from dendritic cells in the gut and reveals the Th1-inducing role of mesenteric lymph node macrophages during colitis. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:3150–3166. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schridde A, Bain CC, Mayer JU, Montgomery J, Pollet E, Denecke B, Milling SWF, Jenkins SJ, Dalod M, Henri S, Malissen B, Pabst O, Mcl Mowat A. Tissue-specific differentiation of colonic macrophages requires TGFβ receptor-mediated signaling. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1387–1399. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, Shpigel N, Boneca IG, Murphy KM, Shakhar G, Halpern Z, Jung S. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sperber K, Ogata S, Sylvester C, Aisenberg J, Chen A, Mayer L, Itzkowitz S. A novel human macrophage-derived intestinal mucin secretagogue: implications for the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1302–1309. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90338-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashi A, Sato T, Kamada N, Mikami Y, Matsuoka K, Hisamatsu T, Hibi T, Roers A, Yagita H, Ohteki T, Yoshimura A, Kanai T. A single strain of Clostridium butyricum induces intestinal IL-10-producing macrophages to suppress acute experimental colitis in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson P, Souza-Moreira L, Morell M, Caro M, O'Valle F, Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado M. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells induce immunomodulatory macrophages which protect from experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2013;62:1131–1141. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maloy KJ, Kullberg MC. IL-23 and Th17 cytokines in intestinal homeostasis. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:339–349. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Bäckhed F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2247–2252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322269111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, Manicassamy S, Munn DH, Lee JR, Offermanns S, Ganapathy V. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varol C, Zigmond E, Jung S. Securing the immune tightrope: mononuclear phagocytes in the intestinal lamina propria. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:415–426. doi: 10.1038/nri2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diehl GE, Longman RS, Zhang JX, Breart B, Galan C, Cuesta A, Schwab SR, Littman DR. Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX(3)CR1(hi) cells. Nature. 2013;494:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueda Y, Kayama H, Jeon SG, Kusu T, Isaka Y, Rakugi H, Yamamoto M, Takeda K. Commensal microbiota induce LPS hyporesponsiveness in colonic macrophages via the production of IL-10. Int Immunol. 2010;22:953–962. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y, Li L, Xu C, Wang Y, Wang Z, Chen M, Jiang Z, Pan J, Yang C, Li X, Song K, Yan J, Xie W, Wu X, Chen Z, Yuan Y, Zheng S, Huang J, Qiu F. Cross-talk between the gut microbiota and monocyte-like macrophages mediates an inflammatory response to promote colitis-associated tumourigenesis. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:690–704. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gubin MM, Esaulova E, Ward JP, Malkova ON, Runci D, Wong P, Noguchi T, Arthur CD, Meng W, Alspach E, Medrano RFV, Fronick C, Fehlings M, Newell EW, Fulton RS, Sheehan KCF, Oh ST, Schreiber RD, Artyomov MN. High-Dimensional Analysis Delineates Myeloid and Lymphoid Compartment Remodeling during Successful Immune-Checkpoint Cancer Therapy. Cell. 2018;175:1014–1030.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Farrell JA, Wang Y, Riesenfeld SJ, Shekhar K, Regev A, Schier AF. Single-cell reconstruction of developmental trajectories during zebrafish embryogenesis. Science. 2018;360 doi: 10.1126/science.aar3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf FA, Angerer P, Theis FJ. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 2018;19:15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, Li Z, Skrzypczynska KM, Fang Q, Zhang W, O'Brien SA, He Y, Wang L, Zhang Q, Kim A, Gao R, Orf J, Wang T, Sawant D, Kang J, Bhatt D, Lu D, Li CM, Rapaport AS, Perez K, Ye Y, Wang S, Hu X, Ren X, Ouyang W, Shen Z, Egen JG, Zhang Z, Yu X. Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted Therapies in Colon Cancer. Cell. 2020;181:442–459.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE, Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, Nainys J, Wu K, Kiseliovas V, Setty M, Choi K, Fromme RM, Dao P, McKenney PT, Wasti RC, Kadaveru K, Mazutis L, Rudensky AY, Pe'er D. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308.e36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li S, Xu F, Zhang J, Wang L, Zheng Y, Wu X, Wang J, Huang Q, Lai M. Tumor-associated macrophages remodeling EMT and predicting survival in colorectal carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1380765. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1380765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sørensen MD, Dahlrot RH, Boldt HB, Hansen S, Kristensen BW. Tumour-associated microglia/macrophages predict poor prognosis in high-grade gliomas and correlate with an aggressive tumour subtype. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2018;44:185–206. doi: 10.1111/nan.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gambardella V, Castillo J, Tarazona N, Gimeno-Valiente F, Martínez-Ciarpaglini C, Cabeza-Segura M, Roselló S, Roda D, Huerta M, Cervantes A, Fleitas T. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer development and their potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;86:102015. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salmaninejad A, Valilou SF, Soltani A, Ahmadi S, Abarghan YJ, Rosengren RJ, Sahebkar A. Tumor-associated macrophages: role in cancer development and therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2019;42:591–608. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li R, Zhou R, Wang H, Li W, Pan M, Yao X, Zhan W, Yang S, Xu L, Ding Y, Zhao L. Gut microbiota-stimulated cathepsin K secretion mediates TLR4-dependent M2 macrophage polarization and promotes tumor metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:2447–2463. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0312-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254–265. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cui YL, Li HK, Zhou HY, Zhang T, Li Q. Correlations of tumor-associated macrophage subtypes with liver metastases of colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1003–1007. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.2.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hamm A, Prenen H, Van Delm W, Di Matteo M, Wenes M, Delamarre E, Schmidt T, Weitz J, Sarmiento R, Dezi A, Gasparini G, Rothé F, Schmitz R, D'Hoore A, Iserentant H, Hendlisz A, Mazzone M. Tumour-educated circulating monocytes are powerful candidate biomarkers for diagnosis and disease follow-up of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2016;65:990–1000. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim Y, Wen X, Bae JM, Kim JH, Cho NY, Kang GH. The distribution of intratumoral macrophages correlates with molecular phenotypes and impacts prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2018;73:663–671. doi: 10.1111/his.13674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawachi A, Yoshida H, Kitano S, Ino Y, Kato T, Hiraoka N. Tumor-associated CD204+ M2 macrophages are unfavorable prognostic indicators in uterine cervical adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:863–870. doi: 10.1111/cas.13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Koelzer VH, Canonica K, Dawson H, Sokol L, Karamitopoulou-Diamantis E, Lugli A, Zlobec I. Phenotyping of tumor-associated macrophages in colorectal cancer: Impact on single cell invasion (tumor budding) and clinicopathological outcome. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1106677. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1106677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Malesci A, Bianchi P, Celesti G, Basso G, Marchesi F, Grizzi F, Di Caro G, Cavalleri T, Rimassa L, Palmqvist R, Lugli A, Koelzer VH, Roncalli M, Mantovani A, Ogino S, Laghi L. Tumor-associated macrophages and response to 5-fluorouracil adjuvant therapy in stage III colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1342918. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1342918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoué F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pagès F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Porta C, Rimoldi M, Raes G, Brys L, Ghezzi P, Di Liberto D, Dieli F, Ghisletti S, Natoli G, De Baetselier P, Mantovani A, Sica A. Tolerance and M2 (alternative) macrophage polarization are related processes orchestrated by p50 nuclear factor kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14978–14983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809784106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saccani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, Biswas SK, Nebuloni M, Vago L, Bottazzi B, Colombo MP, Mantovani A, Sica A. p50 nuclear factor-kappaB overexpression in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits M1 inflammatory responses and antitumor resistance. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11432–11440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Porta C, Ippolito A, Consonni FM, Carraro L, Celesti G, Correale C, Grizzi F, Pasqualini F, Tartari S, Rinaldi M, Bianchi P, Balzac F, Vetrano S, Turco E, Hirsch E, Laghi L, Sica A. Protumor Steering of Cancer Inflammation by p50 NF-κB Enhances Colorectal Cancer Progression. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:578–593. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fliegauf M, Grimbacher B. Nuclear factor κB mutations in human subjects: The devil is in the details. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hao NB, Lü MH, Fan YH, Cao YL, Zhang ZR, Yang SM. Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:948098. doi: 10.1155/2012/948098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang S, Zhong M, Wang C, Xu Y, Gao WQ, Zhang Y. CCL5-deficiency enhances intratumoral infiltration of CD8+ T cells in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:766. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0796-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu C, Yao Z, Wang J, Zhang W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Qu X, Zhu Y, Zou J, Peng S, Zhao Y, Zhao S, He B, Mi Q, Liu X, Zhang X, Du Q. Macrophage-derived CCL5 facilitates immune escape of colorectal cancer cells via the p65/STAT3-CSN5-PD-L1 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1765–1781. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang X, Lang M, Zhao T, Feng X, Zheng C, Huang C, Hao J, Dong J, Luo L, Li X, Lan C, Yu W, Yu M, Yang S, Ren H. Cancer-FOXP3 directly activated CCL5 to recruit FOXP3+ Treg cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36:3048–3058. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu S, He H, Liu H, Cao Y, Li R, Zhang H, Li H, Shen Z, Qin J, Xu J. C-C motif chemokine 22 predicts postoperative prognosis and adjuvant chemotherapeutic benefits in patients with stage II/III gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1433517. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1433517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kumai T, Nagato T, Kobayashi H, Komabayashi Y, Ueda S, Kishibe K, Ohkuri T, Takahara M, Celis E, Harabuchi Y. CCL17 and CCL22/CCR4 signaling is a strong candidate for novel targeted therapy against nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:697–705. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1675-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wei C, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Zhang C, Lin X, Xiong B. M2 macrophages confer resistance to 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer through the activation of CCL22/PI3K/AKT signaling. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:3051–3063. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S198126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cao L, Hu X, Zhang J, Huang G, Zhang Y. The role of the CCL22-CCR4 axis in the metastasis of gastric cancer cells into omental milky spots. J Transl Med. 2014;12:267. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0267-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yeung OW, Lo CM, Ling CC, Qi X, Geng W, Li CX, Ng KT, Forbes SJ, Guan XY, Poon RT, Fan ST, Man K. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophages promote tumour growth and invasiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gilkes DM, Semenza GL, Wirtz D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:430–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spill F, Reynolds DS, Kamm RD, Zaman MH. Impact of the physical microenvironment on tumor progression and metastasis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;40:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Henze AT, Mazzone M. The impact of hypoxia on tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3672–3679. doi: 10.1172/JCI84427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Doedens AL, Stockmann C, Rubinstein MP, Liao D, Zhang N, DeNardo DG, Coussens LM, Karin M, Goldrath AW, Johnson RS. Macrophage expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha suppresses T-cell function and promotes tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7465–7475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Imtiyaz HZ, Williams EP, Hickey MM, Patel SA, Durham AC, Yuan LJ, Hammond R, Gimotty PA, Keith B, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha regulates macrophage function in mouse models of acute and tumor inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2699–2714. doi: 10.1172/JCI39506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stangé G, Van den Bossche J, Mack M, Pipeleers D, In't Veld P, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Casazza A, Laoui D, Wenes M, Rizzolio S, Bassani N, Mambretti M, Deschoemaeker S, Van Ginderachter JA, Tamagnone L, Mazzone M. Impeding macrophage entry into hypoxic tumor areas by Sema3A/Nrp1 signaling blockade inhibits angiogenesis and restores antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Coussens LM, Zitvogel L, Palucka AK. Neutralizing tumor-promoting chronic inflammation: a magic bullet? Science. 2013;339:286–291. doi: 10.1126/science.1232227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Qi L, Chen J, Yang Y, Hu W. Hypoxia Correlates With Poor Survival and M2 Macrophage Infiltration in Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:566430. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.566430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhao Y, Zhao B, Wang X, Guan G, Xin Y, Sun YD, Wang JH, Guo Y, Zang YJ. Macrophage transcriptome modification induced by hypoxia and lactate. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:4811–4819. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang Y, Yang H, Zhao J, Wan P, Hu Y, Lv K, Yang X, Ma M. Activation of MAT2A-RIP1 signaling axis reprograms monocytes in gastric cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kondo H, Ratcliffe CDH, Hooper S, Ellis J, MacRae JI, Hennequart M, Dunsby CW, Anderson KI, Sahai E. Single-cell resolved imaging reveals intra-tumor heterogeneity in glycolysis, transitions between metabolic states, and their regulatory mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108750. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Geeraerts X, Bolli E, Fendt SM, Van Ginderachter JA. Macrophage Metabolism As Therapeutic Target for Cancer, Atherosclerosis, and Obesity. Front Immunol. 2017;8:289. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Miao H, Ou J, Peng Y, Zhang X, Chen Y, Hao L, Xie G, Wang Z, Pang X, Ruan Z, Li J, Yu L, Xue B, Shi H, Shi C, Liang H. Macrophage ABHD5 promotes colorectal cancer growth by suppressing spermidine production by SRM. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11716. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ghafouri N, Tiger G, Razdan RK, Mahadevan A, Pertwee RG, Martin BR, Fowler CJ. Inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase and fatty acid amide hydrolase by analogues of 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:774–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lass A, Zimmermann R, Haemmerle G, Riederer M, Schoiswohl G, Schweiger M, Kienesberger P, Strauss JG, Gorkiewicz G, Zechner R. Adipose triglyceride lipase-mediated lipolysis of cellular fat stores is activated by CGI-58 and defective in Chanarin-Dorfman Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2006;3:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meana C, García-Rostán G, Peña L, Lordén G, Cubero Á, Orduña A, Győrffy B, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. The phosphatidic acid phosphatase lipin-1 facilitates inflammation-driven colon carcinogenesis. JCI Insight. 2018;3 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kofuji S, Kimura H, Nakanishi H, Nanjo H, Takasuga S, Liu H, Eguchi S, Nakamura R, Itoh R, Ueno N, Asanuma K, Huang M, Koizumi A, Habuchi T, Yamazaki M, Suzuki A, Sasaki J, Sasaki T. INPP4B Is a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 Phosphatase That Can Act as a Tumor Suppressor. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:730–739. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang X, Zhang L, Lin B, Chai X, Li R, Liao Y, Deng X, Liu Q, Yang W, Cai Y, Zhou W, Lin Z, Huang W, Zhong M, Lei F, Wu J, Yu S, Li X, Li S, Li Y, Zeng J, Long W, Ren D, Huang Y. Phospholipid Phosphatase 4 promotes proliferation and tumorigenesis, and activates Ca2+-permeable Cationic Channel in lung carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:147. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0717-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang D, Shi R, Xiang W, Kang X, Tang B, Li C, Gao L, Zhang X, Zhang L, Dai R, Miao H. The Agpat4/LPA axis in colorectal cancer cells regulates antitumor responses via p38/p65 signaling in macrophages. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:24. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0117-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pyonteck SM, Akkari L, Schuhmacher AJ, Bowman RL, Sevenich L, Quail DF, Olson OC, Quick ML, Huse JT, Teijeiro V, Setty M, Leslie CS, Oei Y, Pedraza A, Zhang J, Brennan CW, Sutton JC, Holland EC, Daniel D, Joyce JA. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med. 2013;19:1264–1272. doi: 10.1038/nm.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Komohara Y, Jinushi M, Takeya M. Clinical significance of macrophage heterogeneity in human malignant tumors. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1–8. doi: 10.1111/cas.12314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Peranzoni E, Lemoine J, Vimeux L, Feuillet V, Barrin S, Kantari-Mimoun C, Bercovici N, Guérin M, Biton J, Ouakrim H, Régnier F, Lupo A, Alifano M, Damotte D, Donnadieu E. Macrophages impede CD8 T cells from reaching tumor cells and limit the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E4041–E4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720948115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Neubert NJ, Schmittnaegel M, Bordry N, Nassiri S, Wald N, Martignier C, Tillé L, Homicsko K, Damsky W, Maby-El Hajjami H, Klaman I, Danenberg E, Ioannidou K, Kandalaft L, Coukos G, Hoves S, Ries CH, Fuertes Marraco SA, Foukas PG, De Palma M, Speiser DE. T cell-induced CSF1 promotes melanoma resistance to PD1 blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mitchem JB, Brennan DJ, Knolhoff BL, Belt BA, Zhu Y, Sanford DE, Belaygorod L, Carpenter D, Collins L, Piwnica-Worms D, Hewitt S, Udupi GM, Gallagher WM, Wegner C, West BL, Wang-Gillam A, Goedegebuure P, Linehan DC, DeNardo DG. Targeting tumor-infiltrating macrophages decreases tumor-initiating cells, relieves immunosuppression, and improves chemotherapeutic responses. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1128–1141. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Seifert L, Werba G, Tiwari S, Giao Ly NN, Nguy S, Alothman S, Alqunaibit D, Avanzi A, Daley D, Barilla R, Tippens D, Torres-Hernandez A, Hundeyin M, Mani VR, Hajdu C, Pellicciotta I, Oh P, Du K, Miller G. Radiation Therapy Induces Macrophages to Suppress T-Cell Responses Against Pancreatic Tumors in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1659–1672.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ruffell B, Chang-Strachan D, Chan V, Rosenbusch A, Ho CM, Pryer N, Daniel D, Hwang ES, Rugo HS, Coussens LM. Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:623–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hughes R, Qian BZ, Rowan C, Muthana M, Keklikoglou I, Olson OC, Tazzyman S, Danson S, Addison C, Clemons M, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Joyce JA, De Palma M, Pollard JW, Lewis CE. Perivascular M2 Macrophages Stimulate Tumor Relapse after Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3479–3491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sánchez-Martín L, Estecha A, Samaniego R, Sánchez-Ramón S, Vega MÁ, Sánchez-Mateos P. The chemokine CXCL12 regulates monocyte-macrophage differentiation and RUNX3 expression. Blood. 2011;117:88–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kang KA, Ryu YS, Piao MJ, Shilnikova K, Kang HK, Yi JM, Boulanger M, Paolillo R, Bossis G, Yoon SY, Kim SB, Hyun JW. DUOX2-mediated production of reactive oxygen species induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in 5-fluorouracil resistant human colon cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2018;17:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.D'Alterio C, Zannetti A, Trotta AM, Ieranò C, Napolitano M, Rea G, Greco A, Maiolino P, Albanese S, Scognamiglio G, Tatangelo F, Tafuto S, Portella L, Santagata S, Nasti G, Ottaiano A, Pacelli R, Delrio P, Botti G, Scala S. New CXCR4 Antagonist Peptide R (Pep R) Improves Standard Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12071952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zboralski D, Hoehlig K, Eulberg D, Frömming A, Vater A. Increasing Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells through Inhibition of CXCL12 with NOX-A12 Synergizes with PD-1 Blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:950–956. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ghesquière B, Wong BW, Kuchnio A, Carmeliet P. Metabolism of stromal and immune cells in health and disease. Nature. 2014;511:167–176. doi: 10.1038/nature13312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Weichhart T, Hengstschläger M, Linke M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:599–614. doi: 10.1038/nri3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Okaniwa M, Yao Z, Novotny CJ, McWhirter C, Banaji A, Won H, Wong W, Berger M, de Stanchina E, Barratt DG, Cosulich S, Klinowska T, Rosen N, Shokat KM. Overcoming mTOR resistance mutations with a new-generation mTOR inhibitor. Nature. 2016;534:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature17963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Thiem S, Pierce TP, Palmieri M, Putoczki TL, Buchert M, Preaudet A, Farid RO, Love C, Catimel B, Lei Z, Rozen S, Gopalakrishnan V, Schaper F, Hallek M, Boussioutas A, Tan P, Jarnicki A, Ernst M. mTORC1 inhibition restricts inflammation-associated gastrointestinal tumorigenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:767–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI65086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kaneda MM, Messer KS, Ralainirina N, Li H, Leem CJ, Gorjestani S, Woo G, Nguyen AV, Figueiredo CC, Foubert P, Schmid MC, Pink M, Winkler DG, Rausch M, Palombella VJ, Kutok J, McGovern K, Frazer KA, Wu X, Karin M, Sasik R, Cohen EE, Varner JA. PI3Kγ is a molecular switch that controls immune suppression. Nature. 2016;539:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nature19834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sahin E, Haubenwallner S, Kuttke M, Kollmann I, Halfmann A, Dohnal AM, Chen L, Cheng P, Hoesel B, Einwallner E, Brunner J, Kral JB, Schrottmaier WC, Thell K, Saferding V, Blüml S, Schabbauer G. Macrophage PTEN regulates expression and secretion of arginase I modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2014;193:1717–1727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]