Abstract

The corona pandemic has changed the lives of human beings in almost every corner of the globe. Our study sought to explore how Israeli children aged 3-6 experienced the corona period, through semi-structured interviews conducted with a playing cards method. The study is based on the context-informed perspective theory (Nadan and Roer-Strier, 2020) which examines the different contexts in the lives of children growing up in different families, while striving to make children's voices heard as agents/experts of their lives (Corsaro, 1997; Mayall, 2002). The interviews with the children revealed that the Corona period was indeed a challenging and complex period for them. At the same time, following the intensive stay at home, these children showed mental resilience and took responsibility in three main areas: (1) sibling relationships (2) supporting their parents (3) staying alone. Through taking responsibility for these roles, the children have become partners in coping with the challenges that the Corona and the frequent lockdowns have brought to their family’ s lives.

Keywords: COVID 19, Early childhood, Agency, Children roles, Context informed perspective, Children perspective

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Children's roles in the family have changed over time (Ariès, 1962; Hart, 1991). These roles are shaped by culture, time, class, and place (Alaimo, 2002; Plumb, 1972). One of the recent changes in the role of the child in the family has been the liberal approach that sees the value in preserving the rights of children, with the right to education playing a major role. As a result, the children made the transition from home education to studying in educational government institutions (Freeman, 1998). Consequently, most children in the West are accustomed to spending most of their awareness hours in their institutions rather than with their families.

The past year has been characterized by the outbreak of the coronavirus which spread to every corner of the world and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. On February 27, 2020, the first Israeli coronavirus patient was discovered. From that moment on, the health systems in Israel worked with full force. On March13, 2020, a decision was made to close kindergartens in Israel. It was also the last day of normal kindergarten routine. For many children, this was the first time they heard about the coronavirus. The next day, the lives of the children in Israel changed noticeably, suddenly and without preparation. Almost all children in Israel were forced into isolation and to stay with their families regardless of the family structure, the number of siblings, its financial situation, its relationships, the characteristics of the child. There was also a reduction in the manpower of the Ministry of Education during this period. As a result, support for families and children declined significantly (Alter and Keller, 2020). In addition, it is important to note that Israel was the country that shut down its education systems during the Corona period for the longest periods of time of all the OECD countries throughout 2020 (Abulof et al., 2021).

Thus, the coronavirus period is marked by the children's return to spending much more time in the family unit (Russell and Stenning, 2020; de Souza et al., 2020; Mantovani et al., 2021). Yet, the pandemic changed the way of life and routine of the modern family (Brown and Greenfield, 2021; Alter and Keller, 2020). The children and parents had to adapt to a new reality, wherein there is an external threat to their survival. However, the daily routine must continue, which led to changes in the employment structure. For instance, many parents worked from home, a situation that sometimes referred to as being present-absent.

Moreover, the survival threat posed by the coronavirus drove humans to remain within their nuclear families (Evers et al., 2021). Israel is a small country with a traditional family structure, thus, members of the extended family, such as uncles, cousins, and grandparents, play an integral role in the lives of the nuclear family and its children (Even-Zohar, 2015; Lavee and Katz, 2003). The extended stay at home was accompanied not only by an increased fear of the pandemic, but also by the stress caused by the separation from family members, peers, and increased financial strains, all of which have had an impact on the children's life's (de Souza et al, 2020; Malta Campos and Fraga Vieira, 2021). Moreover, while adults had social media to preserve the contact with the outside world (Brown and Greenfield, 2021), young children were exclusively dependent on their nuclear family members to make up the bulk of their social life during this period.

Several studies have examined the effects of the coronavirus on family relationships and the mental state of preschool children (Bray et al., 2021; Ghosh et al., 2020; Mantovani et al., 2021). Most of the studies sought to understand children's experiences and feelings through the perspective of the adults around them, rather than through the children's own perceptions (Bray et al., 2021). This approach is prevalent not only in the academic world but also in public life and institutional decisions. Thus, the voice of the children, the individual differences between them, and the different contexts that affect them were marginalized. A review of electronic databases reveals hundreds of studies published in the past year with respect to preschool children during the coronavirus period. The articles discussed infection, transmission of the disease, mental and physiological condition, relationships with family members, distance learning and the like. Only a scant number of articles sought to hear the voice of children directly (Bray et al., 2021; Ghosh et al., 2020; Mantovani et al., 2021). In Israel, Ben Asher et al. (2020), sampled 654 children aged 10–16 who were asked about their lives and well-being in the shadow of the coronavirus outbreak. The study revealed that although 99% of the children have heard of the coronavirus, only half strongly agreed that they have knowledge about the coronavirus and about half of the children wanted to know more about it. In addition, about 63% of the children reported that the adults around them included them in conversations about coronavirus, meaning that almost 40% of the children did not participate in such conversations. The study also revealed that about 45% of the children would have liked to be heard and consulted regarding the coronavirus.

Conducting research with children as participants may have its own methodological and ethical barriers. It may seem that adults are more accessible, and perhaps this may explain why many studies about children do not sample children. Although children's auto-learning is widely propagated in educational theories seeing the child as an agent who can be engaged, is responsible and enterprising, and mostly, capable of influencing his or her world (Karp,1986), there is also an implicit assumption that knowledge acquisition and learning occurs through observing adult models (Wong and Monaghan, 2020). As a consequence, children's behavior is regarded as mainly reactive, passive, and mimical of adults' behavior and perspectives.

The current study sought to learn about the experience of children aged 3-6 after the third lockdown. Our goal was to identify how children aged 3-6 experienced the coronavirus period in Israel, particularly, how they perceived their role and responsibility within their household during the lockdown. We will examine children's experiences through their own words to explore and observe the children's agency through their perspectives.

2. Methodology

This qualitative interview study was performed in March 2021, right after the end of the third lockdown, which was a significant period in several respects. On the one hand, the third lockdown presented challenging issues to the Israeli society related to the economic stress as well as the social effects of the coronavirus. On the other hand, this period marks the beginning of the vaccination campaign which brought great hope for the future. The current study sample consists of 50 children aged 3-6 (the average age of the interviewees 4.9 years), 28 are boys (56%) and 22 are girls (44%). The participants come from families of medium to high socio-economic status, live in Israel and attend Jewish- Israeli kindergartens. Twenty-nine of the children live in Jerusalem (58%), 13 come from Tel- Aviv (26%) and 8 children live in small community settlements in southern Israel (16 %). Forty-eight of the children are Jewish (96%) and 2 are Muslim (4%). The ethnic backgrounds of the children are comprised of 4 children from Russian families (8%), 1 from an American family, 1 from an Arab- Palestinian family and 1 from a German- Palestinian family. Forty-one of the children come from Jewish-Israeli secular families (82%), 7 from Jewish-Israeli religious families (14%) and 2 children from Muslim secular families. The data were collected using the snowball method, that is, each family introducing another family. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's School of Social Work and conducted in accordance with its guidelines: (1) Obtaining signed informed consent forms from both parents and their children; (2) Guaranteeing confidentiality and discretion throughout the various stages of the study; (3) Guaranteeing the parents and their children that they can terminate the interview at any time without any implications.

Open-ended interviews were created based on the literature related to children’ s perspectives and the psychological impact of quarantine. The questions aimed to explore the experience of children and psychological reactions during the coronavirus period. Prior to each interview, the author coordinated with the children’ s parents by phone the time and location of the interview. During these phone conversations, the parents received information about the nature of the interview and the interviewer as well as the aforementioned assurance that the participants could terminate the interview at any time. In addition, the author asked the parents to obtain their children's consent for the interview. In three events, it was clear that the children were not aware of the interview, although their parents pressured them, they showed no desire to attend. consequently, the author left without conducting the interviews.

Before conducting the interviews with the study participants, a pilot study with five children (three boys and two girls) was conducted to test the interview design. While these interviews were enjoyable for the children, they also provided a great deal of information for the author. All of the research interviews were conducted by the author of this study. The duration of each interview was 10 to 20 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

An effort was made by the author to provide the participants with a secure setting and familiar surroundings to create a relaxed and informal atmosphere. In the beginning of each interview, the author obtained the children’ s consent and assured them that they can terminate the interview at any time they would feel uncomfortable without any consequences (Smith, 2011). The interviews took place at either the children's home or a nearby playground. Prior to each interview, the author met the children and their parents. After the parents signed a consent form, the author explained the process of the interview and the importance he applies to listening to the children's voices. The parents were not present during the interviews, though the children were assured that they can have their parents present at any time.

The interview was conducted using semi-structured in-depth interviews in the form of a game of cards. The cards held questions and prizes about the coronavirus period. Some of the cards had questions and some prizes. After explaining the principles of the game to the interviewees, each child was asked to sign a consent form. The cards held five open-ended questions which sought to investigate how children experienced the coronavirus period: (1) Tell me a story about the coronavirus period; (2) how did you feel during the coronavirus period? (3) What were your parents' feelings during the coronavirus period? (4) What were your decisions within your family? (5) If you were to "meet the coronavirus", what would you say to "her"? The author added more questions based on the children's answers.

2.1. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted thematically according to the six-stage thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) approach which inductively identifies and codes patterns or themes within and across the interview data (Braun et al., 2017). This approach involved: (1) transcribing all data from the open-ended question; (2) re-reading transcripts to gain familiarity with the dataset as a whole; (3) identifying codes; (4) generating emerging themes; (5) organizing and reviewing the themes using the thematic mapping; (6) naming and defining themes and supporting them with powerful examples from the dataset.

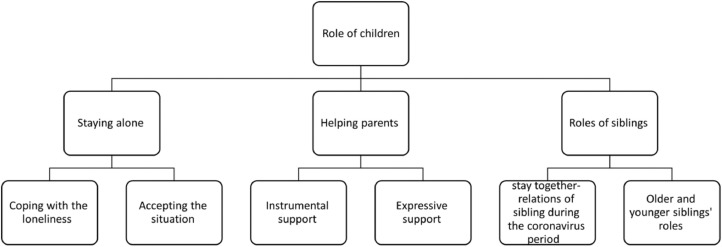

Upon collecting all the data, the interviews were transcribed and read carefully and in depth, with the researcher taking notes of initial ideas that emerged from the text, concerning family relationships, information related to the spread and dangers of the coronavirus, the children and parents' feelings during the coronavirus period, and such. In the second stage of the analysis, the researcher coded units of interest in the body of the findings and reached several key themes regarding the child's roles in the family during the coronavirus period. The data were coded and divided into different sub-categories. In the end of the process, the three main categories that emerged are: (1) Sibling relationships: How the sibling relationships were characterized during the coronavirus period and what was the effect of age on the family role; (2) helping the parents: The help provided by the children to their parents during the coronavirus period was characterized by both the level of instrumental help and the level of expressive help; (3) the ability to be alone: In spite of the joint stay at home during the coronavirus period, the children were left alone for long periods of time to allow for home office work and a proper conduct of the family routine.

3. Results

This chapter presents the experience and roles of children aged 3-6 as they were manifested during the corona period. The findings show that the experience of staying at home during the corona period is complex, ambivalent, and multi-faceted. Staying at home with the family, as it emerges from the interviews, consists of many tasks, and involves significant roles that the children have taken on in light of the reality imposed on the family unit during the Corona period. The children demonstrated awareness in regard to these roles and in relation to the change that has taken place in the new lifestyle. In addition, the children recognized the complexity involved in this period and the roles they have taken on and understand that along with the enjoyment of responsibility given to them, there are also severe feelings of loneliness, frustration, and sadness that they must learn to live with, for their sake and for their family's sake. This chapter presents the roles that the children have been assigned to through three main themes:

-

(1)

Roles of siblings - the children had to spend a long time with their siblings, and these were in fact a substitute for their kindergarten friends. As a result, the children were compelled to maintain the relationship and the time they shared with their siblings. In addition, older and younger siblings experienced the corona period differently from the very division of roles within the family unit and the parents' expectations of each of them, when the family had to cope with the experience of lockdown.

-

(2)

Helping their parents - different children presented different help strategies in relation to their parents. Alongside children who helped a lot in the daily household chores (cleaning, cooking, tidying, etc.), there were children who felt they had to support their parents' mental state and provide them with emotional support.

-

(3)

Staying alone - Although the children and their parents have been together at home for long periods of time, the children stated that one of their main roles was to be alone and occupy themselves both at the request of the parents and in light of the lifestyle the corona brought.

3.1. The role: maintaining relationship with the siblings

About 50 children participated in the study, of whom 43 are siblings (86%) and seven (14%) are single children without siblings. Of the siblings, 20 (40%) children were the oldest siblings in the family, 18 (36%) children were the youngest siblings and two children were twins. 64% of the interviews included reference to sibling relationships during the corona period. If we reduce the interviews with seven children, who are single child then it is 74.4%. According to the children, the relationship with their siblings can be divided into two sub-categories: 1) relationship with the siblings; 2) role differences between older and younger siblings.

3.1.1. Relationships with the siblings

When the children were asked about how they felt during the corona period, their responses showed that almost half (44.3%) enjoyed this period and about a quarter of the respondents experienced the period in a complex way (26%) so that along with the fun they also experienced some difficulties: "I feel pretty fun and not fun. Because the pools won't open but what's fun is that there is no school and we are all at home." (Rani, 6, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Divorced parents). A small group of children experienced the corona only negatively (17.6%) mainly due to the fact that they missed their friends: "It was boring in the corona because it is so impossible to play with friends and go out, and play with my sister is less fun..." (Ziv, 5, Girl Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "I was very upset about the corona, because I'm bored at home... because it's impossible to go to friends..."(Reut, 6.5, Girl, Jewish, Religious, Married parents). It is evident that this group had difficulties due to lack of interaction with the peer group. However, about 22% of the children said they do not miss their friends at all: "I have fun at home. I love it, even though I don't leave the house sometimes, I still have fun at home, and I don't need any friends" (Natalie, 5, Girl, Jewish, Religious, Married parents). Only 12% of the children did not relate to their feelings at all during this period.

One of the main causes of pleasure or displeasure experienced by the children during the corona period is related to their siblings who were with them at home. The corona led to families being compelled to stay together in the same space and avoid meeting other people as much as possible. As a result, all the family members stayed together for a long time and while the parents continued their work remotely, the siblings had to stay with each other and often, as a substitute for friends from kindergarten or the neighborhood: "just so you know I had so much fun in the Corona" (Ravid, 5.5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "To me it felt fun in the corona because I could watch TV and play catch with my sister" (Nathan, 5.5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). About 51.1% of the children with siblings indicated that the time with the siblings was "fun". The main pastimes described in the interviews are play (60.4%), watching TV (34.8%): "I like staying home with David (big brother) because then we both play and watch TV" (Max, 4, Boy, Jewish, Religious, Married parents). Compared to the children who enjoyed with their siblings, about 30.2% stated that the stay with the siblings was not enjoyable and often included quarrels, jealousy, harassment and disturbances: "She (his sister) complains to mom why Rani got ice cream and I didn't" (Rani, 6 Boy, Jewish, Secular, Divorced parents), "I don't have fun at home... because Rani (her brother) and mom fight. I wish Rani could live in a different house, then I would not have heard so many quarrels" (Noa, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Divorced parents). Sometimes there were no quarrels, but it was obvious that there was a feeling of loneliness due to the distance from the friends: "Ella (his sister) is older and she doesn't play the games I play with my friends that are not allowed to come" (Amir, 5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). The other children did not refer to friends or their reference was ambivalent.

3.1.2. Older and younger siblings

As the old proverb suggests, "Friends can be chosen, siblings, not..." Although siblings grow up in a similar physical environment, to the same parents and often to the same values and culture, the way they experience similar situations is often quite different (Daniels and Plomin, 1985). The experience in these cases is influenced not only by the similarities but also by the differences between the siblings that can be related to gender, age, personality traits and relationships with the parents. In our study the most prominent feature that is reflected from the interviews, is the position in the family. According to the children, the fact that the child was an older or a younger sibling, had a great significance for the roles and responsibilities they had in the family unit during the corona period, regardless of the age of the child. The findings show that age is a relative matter, and the role is determined by the position of the child in the family.

Of the older siblings, 75% referred to the roles they have in the home and included the relationship with their younger siblings. The older siblings discussed the great responsibility they felt they had regarding the family unit in general and their younger siblings in particular. This responsibility is manifested in two main manners: (1) responsibility for their younger siblings (2) keeping the younger siblings occupied, so that the parents can devote themselves to their jobs and tasks.

The responsibility to the younger siblings is expressed first and foremost in caring for the siblings' physical state and watching them: "There are things I don't allow my sister Anat to do so that she will not be hurt" (Nathan, 5.5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). In fact, from the children's words we can learn that their attitude towards their younger siblings is a substitute-parental attitude: "I was actually maybe a quarter of her father..." (Andrei, 6, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "When mom went for a walk with the dog, I stayed and he (brother) didn't notice at all that mom left, because I was there" (Adi, 5.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Single mother)," I was responsible for taking care of my little sister because she was afraid the cats would attack her" (Maya, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). This responsibility was not only enjoyable but also empowering: "My little sister thanked me for watching her" (Maya, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents).

The sense of responsibility and authority is reflected in 55% of the interviews. Another responsibility that the older siblings had and was less expressed in the interviews, was the concern for the mental condition of the younger siblings: "It seems to me that he (brother) went to his friend - the baby, and he didn't know if he had corona and then his friend coughed and he contracted corona. When my little brother was sick, I was a little worried and I cried..." (Tammy, 6.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents).

As for the attitude of the little siblings toward the older siblings, the picture is different. Few (33.3%) referred to the responsibility they have in the family. Those who did refer to the relationship (83.3%), did it due to the fun they had with their older siblings: "With Yael it's a lot more fun to play than the with my friends in kindergarten" (Samuel, 4.5, Boy, Jewish, Religious, Married parents), "My brother was in charge of me, and he was tickling me and having fun with me and taking care of my screens (for Zoom)" (Dana, 3.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). The perception of responsibility of the younger siblings mirrors the family hierarchy: "I was in charge of tidying up, but not on my parents, and Andre was in charge of me, and he and mom and dad helped me wash occasionally"(Galit, 5, Girl, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "I was only in charge of the art-works. That's it "(Dana, 3.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). 11% of younger siblings criticized their older siblings: "Because my sister has to do things for school, I have to sort out all the mess my sister made" (Hassan, 6.5, Boy, German – Palestinian, Muslim, Secular, Married parents1 ), "They (the older siblings) messed up their room and broke things in their room all day. Then they felt sad, and they told Mom we're sorry we broke all the things in the room" (Mor, 4.5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents).

3.2. The role: helping the parents

The corona plague has created a situation of uncertainty among human society. Recurring lockdowns, the atmosphere of sickness and the threat of death, unlike anything that human society coped with in the modern age. All that with the additional uncertainty born from ambiguous guidelines that have changed everyone's reality (de Souza et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2020; Mantovani et al., 2021). Various studies have shown that most children were aware of corona, its spread, and characteristics and in addition, they were aware that it poses a major threat to the elderly population (Alter, 2021 in press; Bray et al., 2021). Our findings show that in the new reality, in the shadow of the pandemic, the children have shown initiative, responsibility and activity of various kinds to help and support their parents. Seven children (14%) did not describe any support or assistance they provided to the family during the Corona period. Three other children (6%) claimed they had not decided on anything and had no specific roles at home. The other children's answers can be divided into two main categories: (1) Instrumental support; (2) expressive support.

3.2.1. Instrumental support

Instrumental support addresses the needs that are based on physical aspects and their purpose is to continue the proper existence of the family unit and its routine by providing tangible and practical help and support. Of the 40 children in the study who indicated that they provided help and support to their parents, 45% referred to instrumental help. The instrumental help the children provided for their parents, can be divided into two main ways in which the instrumental help was manifested: Tidying up the house (66.6%) and watching the younger siblings so the parents would be free to work and perform their tasks (44.4%). Some children did both.

The context‐informed perspective (Roer-Strier, 2016) differentiated between different families and different needs. Our findings show the different help provided by the children in their families: "My responsibility was to go downstairs and bring the things my mother wanted from the backyard because dad lived in Ramallah" (Hassan, 6.5, Boy, German – Palestinian, Muslim, Married parents), "When mom and dad went to the hospital to give birth to Gaia, I stayed with grandma and grandpa, and I kept tidying up their house" (Yael, 6.5, Girl, Jewish, Religious, Married parents). "When I'm at mom's I had to tidy up the mess I've made, and that's it but with dad it's a little different because I have to help him with his eyesight and help him understand where I am and where everything is" (Naama, 5.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Divorced parents, Blind father). The help the children provided was mainly due to the sense of responsibility they felt that they bear, and although they are young in age, in terms of their language, they see their help with mature eyes: "I take mom for walks and to watch movies and sometimes dad comes to put me to sleep and sometimes we clean dad's house together"(Noa, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Divorced parents).

Watching their younger siblings is the second major way in which siblings have described the instrumental help they provide to their parents. Watching their younger siblings has been described, throughout the interviews as a chore that aims to allow the parents to rest or go to work, in order to maintain a daily routine. This is also the reason why watching the younger the siblings went into the instrumental theme and not the expressive one: "I had to watch my brother when mom and dad went out to throw the garbage and also so that mom could be zooming on the computer" (Zlil, 6.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "I have responsibilities sometimes [...] so that my sister won't nag my mom because she works from home, so I turn on the TV for her" (Yaron, 6, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents)

Watching the siblings turned out to be far from a simple matter for the older siblings who felt it was their responsibility so that their parents could continue with the routine of life and work: "it is a pretty hard responsibility because she (sister) goes there (to her mom's room) every second and I have to stop her and take her back" (Yaron, 6, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). But all the siblings who addressed the issue explained that they were happy to help and felt it was a great responsibility that they were happy to bear.

3.2.2. Expressive support

Expressive needs relate to the expressive and emotional aspects that the children sought to provide for their parents. These needs aim to observe the other's emotional difficulties and answers them in the form of emotional help, acceptance, attention, or physical gesture such as a hug or a kiss. About 29 children (72.5%) who indicated that they provided help or support to their parents, described expressive support. The support was expressed in three different ways: (1) responsibility for the family's time together; (2) emotional support for the parents; (3) concern for the physical health of the parents.

Of the 40 children who spoke about the importance of helping their parents, 65% noted the great significance that the shared time has on the mental state of the parents and of the children themselves. According to the children, the time shared expressed in a joint stay at home (84.6%), playing a game (38.4%) going on trips (19.2%) and the like. The shared time is not perceived by the children as beneficial only for them, but they sense that it has a mutual benefit for both parties - parents and children: "Because they (the parents) usually don't like to play and in Corona they did like to play, because we can't go to kindergarten and they can't go to work, then everyone can play" (Andrei, 6, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents)," I went for a walk with mom and we were looking for mysteries on the street [...] and mom kept telling everyone about all the things we found" (Luke, 5.5, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents). Unlike the daily routine of life, and particularly during the corona period, the children felt that their parents enjoyed playing with them: "Because she (mother) was very excited and had a lot of fun!" (Luke, 5.5, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents). "They (the parents) liked to play with me in helicopters and cars" (Benny, 3.5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents).

About 37.5% of the children described the emotional support they provided for their parents during the corona period. This support required the children both to recognize the difficulty the parents were in and also to identify how to respond to their needs at a given moment: “It's really important that there is no corona because you can do sports, celebrations, surprise parties at home and mom and dad can go back and do what they do, and not just stay home all the time and take care of their children" (Natalie, 5, Girl, Jewish, Religious, Married parents), "Mom was sad because she thought maybe she would die so I cheered her up and gave her a hug"(Adi, 5.5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Single mother). One of the strongest expressions heard in the expressive support, is to be a "good boy" - the help was expressed in that they behaved as their parents would have liked them to behave: "I don't like to eat the food but in the corona, they (parents) had so much fun to see me finish the whole plate and all the food they made" (Daniela, 5, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "in the corona I started peeing alone and also flush the toilet, and then I poop alone and I overcome the fear from the bathroom and they are really happy because they can stay in the living room with the TV" (Benny, 3.5, Boy Jewish, Secular, Married parents). For the children, the very fact that they are doing what is incumbent upon them, they are helping their parents. By not imposing on their parents the need to discipline them and exercise authority, they feel that they have been helpful.

The last expressive support that the children described in the interviews is the support for their parents' health. Of the children who spoke about parental support, only eight children (20%) described the importance of ensuring that their parents would not get infected with corona and not get sick: "I give only my mother a kiss because that way strangers will not infect me and I will not infect her" (Liron, 4, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Single mother). "I just wanted them (parents) to play with me at home and not go out because that way they don't get infected" (Amar, 6.5, Boy, Palestinian - Muslim, Secular, Married family), "My job was to get them to be fit in the corona... because they need muscles after the corona, they might need to use more muscle and that's how they stay healthy" (Rani, 6, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Divorced family), "I made my parents dance and sing because that way they would be happy and healthy" (Sharon, 3, Boy, American - Jewish, Secular, Married parents). The children were active in the actions they took to take care of their parents and viewed the maintaining of their parents' health as one of their responsibilities.

Additionally, six children out of the seven single children indicated that they had helped their parents. The analysis finds that these children stated that this was an expressive form of help. One example of this is Liron (4): “I drew so that she wouldn't be sad. It gave her a lot of fun because I draw beautiful drawings and it made her very happy." (Liron, 4, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Single mother)

3.3. The role: to be alone

Over the past year more, almost two billion, children worldwide have been in quarantine or lockdown for long periods of time (Russell and Stenning, 2020). Most of the education systems have been shut down and the children have stayed in their home environment together with the nuclear family for long periods of time (de Souza et al., 2020; Mantovani et al., 2021). Allegedly, the long stay should lead to a sense of "togetherness" in the family unit, however it appears from the interviews, that one of the main roles the children faced during the corona period was to be alone. Twenty-four children (48%) noted that they had to stay alone during the corona period, whereas 14 children (28%) claimed they didn't feel alone at any stage and five children (10%) claimed they were part-time alone and part-time with their parents. The main reason the children had to be alone was to allow their parents to keep up with their work. Of the children who felt alone all the time or part of the time, 65.5% indicated that they had been alone while their parents worked via zoom or drove to work: "All the time dad and mom worked and we were not allowed to see programs and things we wanted... they let us play, but it was boring..." (Eitan, 5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). On the other hand, Eitan described how his parents noticed that he was alone and also tried to help him occupy himself so that they could work: "They felt that they could not work because we were bored, so they let us watch TV, then they went to work" (Eitan, 5, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). Staying alone, made the children want to go back to their kindergarten: "In the kindergarten we have a lot more time and also a lot of friends. Here at home, it's just us and mom and dad who can hardly play with us" (Andrei, 6, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents). The parent's jobs were not the only reason the children had to be alone. "It was a bit boring, but okay. When dad rested I made artwork and I needed help with the beads but then I saw I could manage when I was alone" (Noa, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Divorced family), "When they (parents) are in the hot tub I need to keep myself busy... so I play on the tablet because in corona they allow me to play more because there is more time" (Yaron, 6, Boy, Jewish, Secular, Married parents). It is clear that most of the children accepted the fact that staying home alone is a necessity of reality and understood the circumstances that led to that situation. The children explained that the parents had to work thus, they could not stay with them all the time: "They (the parents) prefer to be with me. My mom always says that she prefers to be with me, but she has to work. But then Ran (the mother's boss) he has to decide on all the work, he will be angry with her" (Maya, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Married parents), "It's more important because they have to work, that's how they get paid. They could buy things for the house." (Noa, 6, Girl, Jewish, Secular, Divorced family). The children's descriptions are without resentment since they accept that there is a gap between their parents' will and what happens in reality and they understand that their parents' work involves responsibility, and understand that in fact, there is a direct connection between their parents' work and their personal well-being. Thus, they also sacrifice the feeling of boredom and loneliness, as part of the joint family effort.

The findings showed that the answers which can be considered as 'an exception to the rule' were those of single children. Out of the seven single children interviewed in the study, only two indicated that they sometimes felt alone. As Luke explained: "I was responsible for keeping myself busy because my parents have jobs and I played alone when they worked." (Luke, 5.5, Boy, Russian - Jewish, Secular, Married parents) The other single children prominently noted the fact that their parents spent a lot of time with them.

Except for the single children, the findings indicate that many children felt that even though they stayed with their parents in the same space for long periods of time they still felt alone. The experience of loneliness, alone or with their siblings, was perceived by them as part of their role at home during the corona period in helping their parents continue to run the household. Even though the time that they were alone involved some negative feelings, the findings show that a majority of the children were able to address being alone as a task to be met and therefore, in the bottom line, they enjoyed the corona period.

4. Discussion

The children's voices indicated that the situation in the past year, in which entire families were compelled to remain indoors for long periods of time, created a reality where they transformed to become partners in their family's lives, and took on significant roles to help other family members maintain their daily routine. The findings show that the three main roles that the children took on were: (1) responsibility for the relationship with their siblings (2) instrumental and expressive support for their parents (3) the ability to be alone.

4.1. To be brothers and sisters

43 of the 50 children in the study have siblings. 64% of all children discussed their relationship with their siblings and noted their importance during the Corona period, for better or worse. Sibling relationships in humans are unique relationships and often constitute the longest and most diverse relationship in an individual's life (Abramovich, 2016). The complexity of sibling relationships stems from the fact that though the individual was not privy to choosing them, and on the other hand it is an intense relationship that is influenced by emotional, material, and physical aspects, and is significant to the individual's personal development (White, 2001).

Studies in the field of the family showed that individual differences in the quality of the relationship with birth siblings are related to the social, moral, and cognitive development of the children as well as to their mental health. Many studies tend to see parents in general and the mother in particular, as the primary caregiver of the child in the first years of their lives (Keller, 2003), ignoring the fact that there is another factor in the child's primary environment that influences and takes part in caring for the infant - the older siblings (Buhrmester and Furman, 1990).

Although siblings grow up in a similar physical environment, to the same parents and often with the same values and culture, the way they experience similar situations is often utterly different (Daniels and Plomin, 1985). The context‐informed perspective theory emphasized the notion that even within a similar environment (home, educational setting, extended family, etc.), different contexts create a different experience among siblings. The theory emphasizes other aspects of complexity, hybridity, intersections of locations and power relations (Nadan and Roer-Strier, 2020) and the premise of this approach is that different components in the experience of emotion - social, cognitive, and even physiological - may vary across culture and time. Thus, the individual ought to be addressed and his voice heard, and not just seen as part of a group (Roer-Strier, 2016). Despite the cohabitation, having the same family, and the long time they spend together, different siblings talked about different experiences during this period. The findings indicate that the experiences of siblings who encountered coronavirus together in the same family were influenced by the siblings' relationship, the sibling's age and the parent's attitude towards the younger and older siblings, their longing for friends and educational frameworks, and the time that parents spent with the children. These findings are also consistent with data from previous studies which were not conducted during the coronavirus period, they did however discuss sibling relationships (Ruffman et al., 1998; Buhrmester and Furman, 1990).

Laboratory observations examined the attachment relationship of two-year-old children toward older siblings. The findings indicated that the attachment between siblings is not symmetrical but exists mainly in the younger sibling towards the older sibling, and it is mainly accompanied by the ability of the older sibling to provide attachment for the younger (Ruffman et al., 1998). The place of the child in the birth order is considered to be one of the most significant background variables in the conduct and behavior of siblings in the family and greatly influences the way they experience family life and their role in the family unit (Buhrmester and Furman, 1990).

According to older psychoanalytical approaches, especially Adler (1959), the place of the child in the order of birth dictates a basic position of inferiority or superiority, and as such, determines personal characteristics and influences throughout the life cycle of the individual (Adler, 1959). The author contended that different siblings have different roles in the integration, particularly the eldest and the youngest, and these roles are generally, complementary roles. The older sibling functions as a giver and a nurturer from a position of authority, while the younger sibling functions are to receive and be nurtured. Other studies showed that from the age of three, older siblings began to act rapidly as teachers and as comforting and sensitive colleagues to their younger siblings (Chess, 1986; Dunn, 1983). The findings of the present study support these views.

Sibling relationships during the corona period were significant among the interviewees. In addition, similar to the research of Ruffman et al. (1998), it seems that the older siblings took the main role in the relationship. More than once, the older siblings assumed the parental role for their younger siblings. Concerns for the needs of the younger siblings were reflected, both in the physical level where they helped them with daily chores and cared for basic needs such as showering, eating, drinking, sleeping, and watching them as part of helping their parents, and on the emotional level, reflected in initiating games with their younger siblings, helping them cope with their fears and watching their health.

At the same time, it is worth noting that sibling relationships are not only a source of comfort and confidence in coping with the world but also an object of comparison and rivalry (Schachter, 1982). Notwithstanding the complexity of the coronavirus situation, the difficulties in sibling relationships were rarely expressed in our study. Difficulties usually arose due to the fact that while the older siblings were busy, they also had to undertake the household chores. Such difficulties originated probably from the fact that while the older siblings kept with their school studying online, their young siblings often did not have an organized activity for most of the day. Few young and older siblings claimed to have missed their friends and argued that their siblings were not a substitute for them.

The parental behavior constituted a difficulty in the sibling relationship as well. Some of the older siblings in the study claimed that their parents were mostly busy with their younger siblings and didn't devote sufficient time for them. Previous studies also found that parental attitudes toward siblings have an impact on sibling roles and relationships. Shebloski et al. (2005) examined the various effects of parental attitudes in adolescence found that birth order had a particularly pronounced effect on self-esteem and perception of parental attitudes, that is, there was a strong correlation between older siblings' perception of their parents' attitude towards them and their self-esteem compared to younger siblings.

4.2. Helping the parents

In our study, 80% of the children claimed that their responsibility was to help their parents with various chores and provide emotional support. Along with the desire to make the children's voices heard and seen as partners, there has been an attempt to change the romantic perception that children are pure and innocent and that they must be protected from the dangers that lurk in the world (Farson, 1974). Various authors have begun to discuss the way a childhood is treated as a "utopian prison" and argued that children should be set free so that they be able to claim their rights and be real partners in decision-making processes (Farson, 1974; Holt, 1974). The corona period has shown that even at this time, adults still lookout for their children and do not share with them what is happening in the world in times of crisis (Mantovani et al., 2021). The comparative study by Bray et al. (2021) that followed parents and their children's perceptions of the corona in six different countries around the world (UK, Sweden, Australia, Canada, Brazil, and Spain) showed that many parents, in fear of exposing their children to information about the corona. The same parents feared that their children would meet concepts that might hurt them, the most prominent of which is "death" (Bray et al., 2021). One parent explained that he shares information with his daughter that is "tailored and logical" for her (Bray et al., 2021, p.8). Contrary to such parents' knowledge, a study during the corona that investigated young children in the perception of death found that not only are girls and boys not afraid to talk about death, the subject intrigues and fascinates them and does not necessarily evoke feelings of anxiety (Alter and Keller, 2021).

Contrary to the opinion of various authors who stressed the importance of involving children in decisions at the macro level (Wintersberger, 1999; Ben Arieh and Boyar, 2002), and although no research has been conducted yet on the subject, it seems that children were not involved in making decisions that affected their lives during the corona period at the macro level and were often the last to know about the pandemic's progress and entering a lockdown period (Alter, 2021). On the other hand, the corona also drove parents and children to spend long periods of time together, which created a need to change and adapt the family relationship to the new situation within the family unit. It so happened that alongside a significant increase in child abuse and neglect in Israel and around the world during the Corona period (Arazi and Sabag, 2020; Bhatia et al., 2020), there is evidence in the current study that in normative families, there was in fact a change in parent-child relationships so that children received greater partnership at home.

Some studies contended that helping with household chores contributes a lot to children´s well being. In addition to the skills the children acquire, they also develop responsibility and organization skills, their self-confidence grows, and the family unit is being empowered since each member of the household feels helpful and contributing (Dunn, 2004; Dunn et al., 2009). In addition, a study conducted in the US found that a consistent routine of tasks for children is one of the best predictors that the child will become a happy, healthy, and satisfied adult (Rossman, 2002). It was evident in our study that the children had a sense of responsibility and 66.6% of the children helped their parents with various household chores including watching their younger siblings. These data indicate that helping their parents stemmed from the children's ability to identify the needs of their environment and act accordingly. Contrary to Goodnow's (1996) study which argued that young children cared first and foremost about their personal environment. Our study shows that the children cared about the shared environment just as much as they cared about their personal environment.

Kosher et al. (2016) found a difference between children's reports and their parents' reports concerning the degree of autonomy that children experience in the family and their degree of participation. Although, our study did not examine parental perspectives, it is evident from the interviews, that the children experienced themselves as full and responsible partners to their parents and siblings in the maintenance of the family unit during the corona crisis. Previous studies described the significant contribution of a child's participation in family processes to their development in personal, social, and cognitive domains (Lamborn et al., 1996; Dornbusch et al., 1990). In our study, the children described not only the degree of participation, but also described how they were the ones who took the initiative and assumed responsibility and helped and supported their parents both at the instrumental and expressive level.

Bales and Parsons (2014) contended that the family is "neo-local" - living in its own home, separated from the couple's parents – and is an independent economic unit where the distribution of roles is based on gender and age with a clear hierarchy. In contrast to Parsons' argument, our study found that from the children's perspective the distribution of roles in their home, they may can carry out different roles that are not necessarily related to their chronological age. In addition, the study did not find any evidence that gender affects the type of roles the children held at home during the corona period.

4.3. To stay alone

During the corona period, families were driven to stay together in their home space for long periods of time (Bray et al., 2021, Mantovani et al., 2021). Despite the intense cohabitation, life had to go on. There are no studies on this subject regarding the corona period, however, some experts pointed out that there are significant differences between the first and third lockdown periods, both in the level of the fear, which decreased significantly, and in the level of the population attitude to the lockdown, which is characterized by adults who are now ready and used to work from home and the employers' expectations in that regard. Our findings show that children felt that one of the significant roles they had, was to remain at home alone, while their parents worked. It is of little wonder then, that 48% of the children in our study reported a feeling of loneliness during the lockdown and 38% of all children reported that there was a connection between that feeling and their parents working habits.

Some studies discussed the subject of the feelings, both during the periods of lockdown and pre-coronavirus era. The experience of loneliness is one of the salient feelings that emerged in all studies and among all populations regardless of age or gender (Brooks et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020). A study conducted during the corona period among 15 children aged 6–13 from Iraq and Kurdistan found that children experienced feelings of loneliness and fear of the corona that led to stress, anxiety, and a change in behavior toward other family members (Abdulah et al., 2020). A study conducted in London among parents and caregivers of children aged 5–11 found that 73.8% of caring figures in children's lives reported that children experienced feelings of boredom and 64.5% described an experience of loneliness among children. According to the adults, these feelings led to increased anger, frustration and feelings of anxiety and unease among the children (Morgül et al., 2020).

Contrary to findings found in previous studies, the children in our study did not associate the experience of loneliness with strong feelings such as depression, frustration, and anger. However, 24% in our study associated loneliness with boredom. It is noted that 62% of the children who felt alone, described acceptance, and understanding of the current situation. The same children explained that their ability to be alone is part of the help they give their parents so that they can continue to run their daily routine. These data correspond with previous studies that demonstrate the children's abilities to present creative, complex, and flexible thinking, far beyond what might have been expected in light of conventional educational theories (Nadan and Roer-Strier, 2020). This ability to adjust to crisis situations demonstrate the resilience of the children who participated in the study. Place et al. (2002) argued that resilience is a dynamic condition, it is about the child's ability to meet difficulty and use it for growth. Resilience is based on both the child's personality and the family support he or she receives. The ability of parents and families to provide consistency, stability, support, and guidance in the face of risk factors, creates personal resilience among children (Smith and Carlson, 1997). Experiences of feeling alone were scarce among the single children in the study. It is evident that due to the fact that children were in fact removed from their social circles and away from their friends and peers, their parents applied greater importance to spending time with them Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Shows the main themes.

It should be noted that the children in the present study came from families of medium-high socio-economic status which in general, allowed them to experience economic stability during the corona crisis Table 1 .

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic characteristics.

| N = 50 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 28 | 56 |

| Female | 22 | 44 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 3 | 10 | 20 |

| 4 | 13 | 26 |

| 5 | 17 | 34 |

| 5 | 10 | 20 |

| sibling position | ||

| Oldest | 20 | 40 |

| Middle | 3 | 6 |

| Twin | 2 | 4 |

| Youngest | 18 | 36 |

| Without siblings | 7 | 14 |

| Family type | ||

| Nuclear Family | 45 | 90 |

| Single Parent Family | 2 | 4 |

| Divorced Family | 3 | 6 |

5. Conclusion

The present study demonstrated how children have adapted to the new family life that the lockdowns have brought with them as a result of the corona pandemic. The findings show that the children expressed resilience, took responsibility, and participated in running the household out of a desire to help their parents and their siblings. Most of the children's help focused on three main areas: (1) sibling relationships; (2) instrumental and expressive support of the parents (3) staying alone. The children were alert and described the difficulties that arose during the corona period such as boredom, quarrels with their siblings and being away from their parents. However, they realized that these difficulties are an opportunity for them to take responsibility for themselves and their environment. The study clarifies the importance of involving children in making decisions and listening to their voices both in daily life and in times of crisis. The study suggests that it is worthwhile to bring the children out of the "utopian prison" in which they are and allow them to recognize the reality as it is, so that they can be full partners and gain their rights.

6. Limitations

The current study has some limitations. The children interviewed came from households of medium and high socio-economic status and thus, the findings reflect this more privileged group within Israeli society. The study was conducted during the coronavirus period. Therefore, there was no possibility to compare the roles and responsibilities that children took on during this period to the way the family functioned before . Furthermore, it is not clear to what extent the children took on these roles out of awareness and to what extent this was done out of parental expectation or demand. There are some references to this in the interviews, however, there is room for further studies to expand on this topic. In addition, due to the small sample size, the study is limited in finding meaningful patterns emerging in families from different cultural and religious backgrounds, different family structures and living areas.

Another limitation is the timing of the study. It was conducted against the backdrop of the end of the third lockdown and right before the vaccination campaign. Hence, the findings of the study may reflect this specific period in time when the effects of the coronavirus were relatively new and people responded with more urgency. Even nowadays, the coronavirus in Israel has become embedded in everyday life outside of the context of lockdowns. Longitudinal and historical studies in the future may help to better understand the long-term effects of the coronavirus crisis on family dynamics and children's development, and how these intersect with different cultural contexts and family structures.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Or Perah Midbar Alter reports administrative support was provided by The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Or Perah Midbar Alter reports a relationship with The Hebrew University of Jerusalem that includes:. Academic supervision by Prof. Heidi Keller

Footnotes

Even though the parents are married they live separately. The mother lives in Jerusalem and the father in Ramallah. Hassan lives with his mother.

References

- Abdulah D.M., Abdulla B.M.O., Liamputtong P. Psychological response of children to home confinement during COVID-19: A qualitative arts-based research. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020972439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramovitch H. Resiling; (Hebrew): 2016. Brothers and Sisters: Myth and Reality. [Google Scholar]

- Abulof U., Penne S.L., Pu B. The pandemic politics of existential anxiety: between steadfast resistance and flexible resilience. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2021;42(3):350–366. doi: 10.1177/01925121211002098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. Premier Books; 1959. Understanding Human Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo K., Alaimo K., Klug B. Children as Equals: Exploring the Rights of the Child. University Press of America; 2002. Historical roots of children's rights in Europe and the United States; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alter O., Keller H. Children as actors: How young children experience the pandemic. Betrifft Kinder. 2020;9(10):6–11. (German) [Google Scholar]

- Alter, O., Keller, H., 2021. Children talk about death. Betrifft Kinder, 5 (6), (in German).

- Alter, O. (2021) Children talk about the corona: the corona period through the perspective of girls and boys ages 3–6. In O. Koret & D. Gibon (Eds.), Corona Days: Preschool Children in Times of Crisis. (In press)

- Ariès P. Knopf; 1962. Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life. (Translated from French by R. Baldick) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arazi T., Sabag Y. Effects of the corona crisis on children and adolescents at risk. Haruv institute press. Meet. Point. 2020;20 . 15-10. (Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bales R.F., Parsons T. Routledge; 2014. Family: Socialization and Interaction Process. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh A., Boyar J. The little citizen in Israel: citizenship and childhood - affinity and influence. Soc. Secur. 2002;63:263–270. (Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben- Arieh A., Brook S, Farkash H. Haruv Institute; 2020. Perceptions and Feelings of Children and Adolescents in Israel Regarding the Corona Virus and Their Personal Lives.https://haruv.org.il/wp-content/uploads (Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia A., Fabbri C., Cerna-Turoff I., Tanton C., Knight L., Turner E., …, Devries K. COVID-19 response measures and violence against children. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020;98(9):583. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.263467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Gray D. Cambridge University Press; 2017. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Bray L, Carter B, Blake L, Saron H, Kirton JA, Robichaud F, et al. People play it down and tell me it can't kill people, but I know people are dying each day”: Children's health literacy relating to a global pandemic (COVID-19); an international cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet N. Am. Ed. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G., Greenfield P.M. Staying connected during stay-at-home: communication with family and friends and its association with well-being. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021;3(1):147–156. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D., Furman W. Age differences in perceptions of sibling relationships in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 1990;61:1387–7389. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess S. Siblings: love, envy and understanding. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1986;174(3):183–184. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro W.A. Sage Publications; 1997. The Sociology of Childhood. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D., Plomin R. Differential experience of siblings in the same family. Dev. Psychol. 1985;21(5):747–760. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.5.747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza J.B., Potrich T., de Brum C.N., Heidemann I.T.S.B., Zuge S.S., Lago A.L. Repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic from the childrens’ perspective. Aquichan. 2020;20(4):1–11. doi: 10.5294/aqui.2020.20.4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch S.M., Ritter P.L., Mont-Reynaud R., Chen Z. Family decision making and academic performance in a diverse high school population. J. Adolesc. Res. 1990;5:142–160. doi: 10.1177/074355489052003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Sibling relationships in early childhood. Child Dev. 1983:787–811. doi: 10.2307/1129886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L. Validation of the CHORES: a measure of school-aged children's participation in household tasks. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2004;11(4):179–190. doi: 10.1080/11038120410003673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn Wendy J.Coster, Cohn Ellen S., Orsmond Gael I. Factors associated with participation of children with and without ADHD in household tasks. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2009;29(3):274–294. doi: 10.1080/01942630903008327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Even-Zohar A. Grandparent-grandchild relationships in Israel: a comparison between different Jewish religious groups. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2015;13(1):75–88. doi: 10.1080/15350770.2015.992876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evers N.F., Greenfield P.M., Evers G.W. COVID-19 shifts mortality salience, activities, and values in the United States: big data analysis of online adaptation. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021;3(1):107–126. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farson R. Macmillan; 1974. Birthrights. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.D. Vol. 14. Multilingual Matters; 1998. (Bilingual education and Social Change). [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Dubey M.J., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. Impact of COVID-19 on children: special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatr. 2020;72(3):226–235. doi: 10.23736/s0026-4946.20.05887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow J.J., Harkness S., Super C.M. Parents' Cultural Belief Systems: Their Origins, Expressions, and Consequences. The Guilford Press; 1996. From household practices to parent's ideas about work and interpersonal relationships; pp. 313–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hart S.N., Pavlovic Z. Children's rights in education: an historical perspective. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 1991;20:345–358. doi: 10.1080/02796015.1991.12085558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt J.C. EP Dutton; 1974. Escape from Childhood. [Google Scholar]

- Karp I. Wiley; 1986. Agency and Social Theory: A Review of Anthony Giddens. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H. Socialization for competence: cultural models of infancy. Hum. Dev. 2003;46(5):288–311. doi: 10.1159/000071937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kosher H., Ben-Arieh A., Hendelsman Y. Springer; 2016. Children's Rights and Social Work. [Google Scholar]

- Lamborn S.D., Dornbusch S.M., Steinberg L. Ethnicity and community context as moderators of the relations between family decision making and adolescent adjustment. Child Dev. 1996;67:283–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01734.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavee Y., Katz R. The family in Israel: Between tradition and modernity. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2003;35(1-2):193–217. doi: 10.1300/J002v35n01_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loades M.E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., Reynolds S., Shafran R., Brigden A., …, Crawley E. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malta Campos M., Vieira L.F. COVID-19 and early childhood in Brazil: impacts on children's well-being, education and care. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani S., Bove C., Ferri P., Manzoni P., Cesa Bianchi A., Picca M. Children ‘under lockdown’: voices, experiences, and resources during and after the COVID-19 emergency. Insights from a survey with children and families in the Lombardy region of Italy. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2021;29(1):35–50. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayall B. Open University Press; 2002. Towards a Sociology for Childhood: Thinking from Children's Lives. [Google Scholar]

- Morgül E., Kallitsoglou A., Essau C.A.E. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on children and families in the UK. Rev. Psicol. Clín. Niños Adolesc. 2020;7(3):42–48. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadan Y., Roer-Strier D. A context-informed perspective of child risk and protection: deconstructing myths in the risk discourse. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2020;12(4):464–477. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Place M., Reynolds J., Cousins A., O'Neill S. Developing a resilience package for vulnerable children. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2002;7(4):162–167. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb J.H., Plumb J.H. In the Light of History. Allen Lane; 1972. Children, the victims of time; pp. 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Roar-Strier D. Social work academic training informed-context with families: insights and challenges. Soc. Welf. 2016;36(4-3) (Hebrew) 462-439. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman M. University of Minnesota, Mimeo; 2002. Involving Children in Household Tasks: Is it Worth the Effort. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffman T., Perner J., Naito M., Parkin L., Clements W.A. Older (but not younger) siblings facilitate false belief understanding. Dev. Psychol. 1998;34(1):161–174. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell W., Stenning A. Beyond active travel: children, play and community on streets during and after the coronavirus lockdown. Cities Health. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1795386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter F.F. In: Sibling Relationships: their Nature and Significance Across the Lifespan (1st ed.). Psychology Press. Lamb M.E., Sutton-Smith B., editors. 1982. Sibling deidentification and split-parent identification: a family tetrad; pp. 123–151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shebloski B., Conger K.J., Widaman K.F. Reciprocal links among differential parenting, perceived partiality, and self-worth: a three-wave longitudinal study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005;19(4):633–642. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.B., Harcourt D., Perry B., Waller T. Researching Young Children's Perspectives: Debating the Ethics and Dilemmas of Educational Research With Children. Taylor & Francis; 2011. Respecting children's rights and agency: Theoretical insights into ethical research procedures; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C., Carlson B.E. Stress, coping, and resilience in children and youth. Soc. Serv. Rev. 1997;71(2):231–256. [Google Scholar]

- White L. Sibling relationships over the life course: a panel analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 2001;63(2):555–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00555.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wintersberger H., Riepl B., Wintersberger H. Political Participation of Youth Below Voting Age. European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research; 1999. Developments in international law and European policies; pp. 14–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wong C., Monaghan M., Klonoff D.C., Kerr D., Mulvaney S.A. Diabetes Digital Health. Elsevier; 2020. Behavior change techniques for diabetes technologies; pp. 65–75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]