ABSTRACT

Background:

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) and periodontal diseases (PDs) have shown a bidirectional and vice versa relationship. Hence, this study aimed to identify the extent and magnitude between MetS and PDs in females.

Materials and Methods:

A published literature was explored by considering case–control, cross-sectional, and cohort studies that involved patients with measurements of MetS and PD. Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and Cochrane Library databases were used for the search. This study examined the relationship between the MetS and PD among females.

Results:

Of the initial 4150 titles screened, a total of 37 reported papers were eligible for quantitative review. A gender-wise analysis of the findings revealed a crude odds ratio (OR) of 1.385 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.043–1.839, I2 = 94.61%, P < 0.001] for the females relative to the average OR of 1.54 (95% CI: 1.39–1.71, I2 = 90.95%, P < 0.001). Further subgroup analysis for directionality in females revealed the crude ORs of 1.28 (95% CI: 0.91–1.79, I2 = 96.44%, P < 0.001) for the relationship between PD and MetS, whereas an OR of 2.12 (95% CI: 0.78–5.73, I2 = 88.31%, P < 0.001) was found between MetS and PDs.

Conclusion:

This study lacks convincing proof of a link between MetS and PDs in females when compared with an overall association between MetS and PDs. Directionality indicated higher odds of linking between MetS and PD than PD and MetS among females. Further longitudinal and treatment trials are needed to confirm the association among females.

KEYWORDS: Females, metabolic syndrome, periodontal diseases, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a group of health conditions involving belly fat, increased blood sugar, hypertension, raised triglycerides, and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. The root causes of MetS include increased weight and obesity, insulin tolerance, hereditary conditions, inappropriate eating, lack of physical activity, and aging. The worldwide prevalence of MetS in the adult population increases with an approximate prevalence of 20–25%.[1] Adults suffering with Mets have a five times more severe chance of having type 2 diabetes and are thrice at risk of heart attack or stroke than those without MetS.[1,2,3] In this backdrop, MetS is deemed a public health problem worldwide.[4,5] Periodontal disease (PD) is a group of conditions affecting the tooth’s supporting tissues including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. It most frequently develops as a response to chronic infection and inflammation, usually resulting from the presence of pathogenic bacteria.[6]

Cumulative evidence over the years suggests that PDs are associated with glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure (BP), and a low-grade systemic inflammation,[7,8,9,10,11] along with other systemic diseases and conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity.[12,13] The supposed link may be attributed to the various common risk factors,[14] the release of inflammatory cytokines,[15] abdominal obesity,[16] oxidative stress,[17] proatherogenic lipoproteins,[18] and cross-reactivity and molecular mimicry,[19] which could a play role in these associations.

In females, the association between PDs and MetS and vice versa has not been fully reported. Hence, this systematic review aims to identify the extent and a possible bidirectional association between PDs and the presence of MetS in females. Furthermore, the extent and directionality of the associations were compared with the overall findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed in this study. The broad research question included is: “is there any bi-directional association between PDs and MetS among females?” The review strategy adhered to the PECO format.

STUDY SELECTION

The observational studies of case–control, cross-sectional, cohort studies, and population surveys involving female subjects with measures of MetS and PDs and/or controls were included in the review.

SEARCH STRATEGY

The literature search was carried out using the electronic databases MedLine, EMBASE, LILACS, and Cochrane library. The unpublished databases were complemented by a search through reference lists. Only English Language articles were included in the search. Peer-reviewed studies, reports, book chapters, conference abstracts, and theses were screened among published literatures. Narrative reviews on the topic were searched in order to identify suitable papers. Ahead-of-print publications were sought by contacting editors of the journals with the impact on our search (dental, metabolic, cardiovascular). The search was updated on December 31, 2019.

The search strategy included the following search words: MeSH terms in all trees/subheadings: “periodontal diseases” and “insulin resistance.” Keywords for PD are: “tooth loss,” “alveolar bone loss,” “periodont*,” and “gingiva*.” Similarly, keywords for MetS included “metabolic syndrome,” “syndrome X,” “obesity,” “hypertension,” “diabetes mellitus,” “insulin resistance,” “hypertriglyceridemia,” “hyperlipidemia,” “hypercholesterolemia,” “dyslipidemia,” “hyperglycemia,” and “hyperinsulinism.”

A study selection involved first stage of initial screening of potentially suitable titles and abstracts based on inclusion criteria. The second stage consisted of screening of the full papers that were identified as possibly relevant in the initial screening. In the third stage, a full database was built after careful analysis listing of selected studies.

DEFINITIONS OF PDS AND METS

Due to the lack of similar diagnostic criteria of PD and MetS in various published articles, the following criteria have been applied.

1. Diagnosis of periodontitis

-

a.

Periodontitis included a minimum of two areas of different teeth having clinical attachment level (CAL): at least two sites on different teeth with CAL ≥ 6 mm and at least one site with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥ 4 mm[20] or minimum two areas of non-adjacent teeth proximal attachment loss ≥ 3 mm,[21] or community periodontal index (CPI) score of 4 in at least one quadrant.[22] However, in situations with no reported CAL or PPD, a radiographic alveolar bone loss was ≥ 30% of root length or ≥ 5 mm in at least two teeth.

2. Diagnosis of gingivitis

Gingivitis included a minimum of 30% of sites with bleeding on probing or mean bleeding index = 1[23] or at least 15 bleeding sites.[24] In some cases, gingivitis referred to unspecified gingival inflammation.

3. Diagnosis of MetS

-

a.

MetS refers to the condition when any three of the five risk factors were recorded: increased waist circumference (≥88 cm in women), increased fasting triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL or on drug treatment for elevated triglycerides), decreased HDL cholesterol (<50 mg/dL in women or on drug treatment for reduced HDL cholesterol), increased BP (systolic BP ≥130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥85 mmHg, or on antihypertensive drug treatment in patients with history of hypertension), and increased fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dL or on drug treatment for elevated glucose).[25]

DATA EXTRACTION

Descriptive information including the study outcomes and odds ratios (ORs) were extracted from each study, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of studies included in the review

| Author (year) | Directionality | Study design | Sample size | Female sample (%) | Mean age (years) | Criteria for PD | % With PD | Criteria for MetS | % With MetS | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shimazaki et al.[26] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 584 females | 100 | 55.7 | Average CAL ≥ 3 mm | 6.3 | NCEP-ATP III | 16.8 | 3.3 (1.2–8.8) |

| 2 | D’Aiuto et al.[11] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 13,994 | 38 | 40.7 | Page and Eke[20] | 14.0 (moderate to severe) | IDF 2005 | 37 | Severe periodontitis and MetS assoc. 1.74 (1.10–2.76) (P < 0.05) if age >44 years |

| 3 | Khader et al.[27] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 156 | 64.1 | 47.2 | No categorical definition applied | Not reported | NCEP-ATP III | 50 | PD (P <0.0005), CAL (P <0.0005) |

| 4 | Kushiyama et al.[28] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 1070 | 73.3 | 63.3 | CPI code 4 | 29.5 | NCEP-ATP III | 5 | Association between MetS and PD: OR 2.13 (1.22–3.70) |

| 5 | Li et al.[29] | PD to MetS | Case–control | 208 | 43.3 | 60.9 | Greater than 33% sites, ≥ 3 mm CAL | 72.4 | IDF 2005 | 72.9 | Association between MS and PD: OR for % CAL ≥3 and MS tertiles: 0–33 OR 6.91 (1.07–44.77), 33–67 OR 9.89 (1.50–65.24), 67–100 OR 15.60 (2.20–110.43) |

| 6 | Morita et al.[30] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 2478 (450 females, 2028 males) | 18.2 | 43.3 | CPI code 3–4 | 25.9 | Modified (Japanese) IDF 2005 | 8.2 | 2.4 (1.7–2.7), P <0.01 |

| 7 | Andriankaja et al.[16] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 7431 | 52.7 | 40.4 | Mean PD ≥2.5 mm | 5.8 | NCEP-ATP III | 19.7 | 4.7 (2.0–11.2) (P< 0.001), only in females |

| 8 | Benguigui et al.[31] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 255 | 45.1 | 57.9 | Page and Eke[20] | 78.8 | ATP III | 28.6 | Association between MS and PD: moderate: OR 1.54 (0.59–4.01), severe: OR 1.97 (0.74–5.23) |

| 9 | Han et al.[32] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 1046 (589 females, 457 males) | 56.3 | 42.3 | CPI code 3-4 | 34 | IDF 2009 | 22.4 | No. of positive components of MetS and periodontitis (CPI 3–4) OR 1.7 (1.22–2.37), P = 0.002 |

| 10 | Morita et al.[12] | PD to MetS | Longitudinal | 1023 | 29 | 37.3 | CPI code 3-4 | 20 | Modified (Japanese) IDF 2005 | 0% at baseline | If two or more positive components, 2.2 (1.1–1.4), P < 0.05 |

| 11 | Nesbitt et al.[33] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional data of longitudinal | 200 | 39 | 56.8 | Distance between CEJ and crest of alveolar bone measured on panoramic radiograph. None or slight bone loss: 1–2 mm, moderate: 3–4 mm, or severe ≥ 5 mm | 21.5 | Modified ATP III | 17.5 | Moderate-to-severe bone loss assoc. 2.61 (1.1–6.1) (P < 0.05) |

| 12 | Timonen et al.[34] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 2050 | 60.8 | 46 | No categorical definition applied | Not reported | EGIR | 16.4 | Association between MS and PD: RR of 1.19 (1.01–1.42) for PPD ≥ 4; RR of 1.5 (0.96–2.36) for PPD ≥ 6 |

| 13 | Bensley et al.[35] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 672 | 51 | 48 | Self-reported | 42 | AHA 2009 | 64 | No P-value |

| 14 | Chen et al.[36] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 253 subjects undergoing hemodialysis | 53.8 | 58.8 | PI (Silness and Loe), GI (Loe and Silness), Ramfjord Periodontal Disease Index, gingival inflammation designated: no inflammation (PDI 0), mild gingivitis (PDI 1), moderate gingivitis (PDI 2), and advanced gingivitis (PDI 3). Attachment loss 0–2 mm (PDI 4), 3–6 mm (PDI 5), and >6 mm (PDI 6) | 80 | NCEP-ATP III | 57.3 | If moderate-to-severe periodontitis OR 2.73 (1.29–5.79) (P = 0.008) |

| 15 | Kwon et al.[13] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 7178 | 62.5 | 45.6 | CPI code 3-4 | 45.7 | NCEP-ATP III | 28.3 | Association between PD and MS: OR 1.55 (1.32–1.83) |

| 16 | Fukui et al.[37] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 6421 Japanese (1477 females, 4944 males) | 23.1 | 43.4 | PD and CAL measured at MB sites: none/mild if ≤3 mm, moderate if 4–5 mm, severe if ≥6 mm | 42.6 | NCEP-ATP III | 14.9 | Severe periodontitis associated with MetS 1.35 (1.03–1.77) (P < 0.05) |

| 17 | Han et al.[15] | PD to MetS | Case–control | 332 | 43.3 | 42.2 | CPI code 3-4 | 41.8 | Joint/unified classification, except that the fasting plasma glucose level cutoff >110 mg/dL rather than 100 mg/dL | 50 | 1.76 (1.06–2.973) (P = 0.029) in overall subjects |

| 18 | Furuta et al.[38] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 2370 (1330 females, 1040 males, from Hisayama Health Examination 2007) | 56.1 | 59.5 | MB and MdB sites; CAL, PD, % sites with BOP. Subjects with at least 10 teeth | 64 | Joint/unified classification (waist circumferences ≥90 cm in male, ≥80 cm in female) | 35 | Mean PD ≥3 or 3.5 mm , then MetS associated in females (P < 0.05), but not in males |

| 19 | Sora et al.[39] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 283 | 76 | 55.3 | Extent of severe periodontitis, defined as total tooth-sites per person measuring 6+ mm for CAL and 5+ mm for PPD, evaluated separately | 70.6 | NCEP-ATP III | 85.8 | Association between MS and PD: Sites with PPD ≥5 mm: RR 2.18 (0.98–4.87) Sites with CAL ≥ 6 mm: RR 2.77 (1.11–6.93) |

| 20 | Tu et al.[40] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 33,740 Taiwanese | 54.7 | 50 | Periodontal disease defined as combination of the following: tooth mobility, gingival inflammation, periodontal pocketing (no specific values were given) | 30 | NCEP-ATP III | 23 | MetS assoc. with periodontitis in females: 1.52 (1.41–1.63) (P < 0.001), males: 1.04 (0.96–1.12) (P = 0.317) non-significant |

| 21 | LaMonte et al.[41] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 657 females | 100 | 65.5 | Page and Eke[20] | 77 | NCEP-ATP III | 25.6 | 1.08 (0.67–1.74) (P <0.05 each) |

| 22 | Lee et al.[42] | MetS to PD | Longitudinal | 399 | 57.1 | 72.3 | CPI code 3-4 | 26.2 | Combination of different classifications: BMI ≥25, BP ≥140/90 mmHg, FGL ≥126 mg/dL, HC ≥240 mg/dL | 22.3 | If two or more MetS components, more likely to have periodontal disease (P < 0.05), 10.53 (4.98–22.28) |

| 23 | Thanakun et al.[43] | MetS to PD | Case–control | 125 | 57.6 | 47 | AAP | 72 | IDF 2009 | 64.8 | 3.60 (1.34–9.65) |

| 24 | Alhabashneh et al.[44] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 280 | 49.3 | 53.8 | Periodontitis was defined as presence of four or more teeth with highest reading of PPD ≥3 mm and CAL ≥3 mm | 39.6 | IDF 2005 | 83.2 | Association between MS and PD: OR 3.28 (1.30–8.30) |

| 25 | Iwasaki et al.[45] | PD to MetS | Data part of longitudinal study | 125 | 56 | 75 | Full-mouth CAL was recorded, six sites around each tooth | Not reported | Modified NCEP-ATP III | 27.6 | Relative risk = 2.58, 95% confidence interval = 1.17–5.67 |

| 26 | Han et al.[46] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 941 | 37.3 | 15 | CPI code = 1 was clearly classified into gingivitis group | 23.1 (gingivitis) | NCEP-ATP III | 3.5 (at risk of MetS) | Correlation of MetS with gingivitis 3.29 (95% CI: 1.24–8.71) |

| 27 | Minagawa et al.[47] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 234 (123 females, 111 males) | 52.5 | 80 | (i) Severe periodontitis: having six or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 6 mm and three or more interproximal sites with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥ 5 mm (not on the same tooth), (ii) moderate periodontitis: having six or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 4 mm or six or more interproximal sites with PPD ≥ 5 mm (not on the same tooth), and (iii) no or mild periodontitis: neither “moderate” nor “severe” periodontitis | 77.3 | Modified (Japanese) IDF 2005 | 24.4 | Crude odds ratio = 2.24, 95% confidence interval = 1.14–4.41 |

| 28 | Gomes-Filho et al.[48] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 419 | 61.8 | 59 | Page and Eke[20] | 55 | IDF 2005 | 61 | Association between PD and MS: diagnosis of periodontitis: 0.98 (0.62–1.53). Severe periodontitis: 2.11 (1.01–4.40) |

| 29 | Kumar et al.[49] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 259 | 47.1 | 38.7 | AAP | 50.1 | NCEP-ATP III | 22 | OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.36–5.18, and P < 0.003 |

| 30 | Jaramillo et al.[50] | MetS to PD | Case–control | 651 | 63.9 | 55.5 | Page and Eke[20] | 66.2 | AACE 2003 | 9.8 | Association between PD and MS: OR 2.72 (1.09–6.79) |

| 31 | Kikui et al.[51] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 1780 | 58.2 | 66.5 | CPI code 3-4 | 50.1 | Modified (Japanese) IDF 2009 | 26.6 | Association between PD and MS components: three components: OR 1.42 (1.03–1.96), four components: OR 1.89 (1.31–2.73) |

| 32 | Musskopf et al.[52] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 363 | 63.9 | 58.5 | Page and Eke[20] | 26.9 | IDF 2009 | 54.8 | Association between MS and severe PD: PR 1.62 (1.13–2.34) |

| 33 | Shin[53] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 13,066 | 55.9 | ≥ 20 years | CPI code 3-4 | 29.1 | IDF 2009 | 27.3 | AOR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.04–1.36 for 20–27 teeth, AOR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.12–1.67 for 0–19 teeth |

| 34 | Doğan et al.[54] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 176 females | 100 | 50 | Full-mouth periodontal examinations conducted at six sites around each tooth were examined. Pocket depth and CAL were recorded. | Not reported | NCEP-ATP III | 27.8 | Not reported |

| 35 | Kim et al.[55] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 5078 | 58.3 | 72 | AAP | 16.1 | IDF 2009 | 48.7 | Men: 1.43 (1.17–1.73), women: 1.08 (0.98–1.20), 95% confidence interval |

| 36 | Koo and Hong[56] | MetS to PD | Case–control | 13,196 | 47.9 | 57.3 | CPI code 3-4 | 29 | NCEP-ATP III | 32.9 | OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.01–1.24 |

| 37 | Pham[57] | PD to MetS | Case–control | 412 | 72.3 | 57.8 ± 5.7 years | Page and Eke[20] | 28.5 | NCEP-ATP III | 50 | OR = 4.06 (95% CI: 2.11–7.84) (P < 0.001). |

| 38 | Shearer et al.[58] | PD to MetS | Data part of longitudinal study | 952 | 49.2 | 38 | Periodontal examinations were conducted with full-mouth examinations and third molars and implants were excluded. Three sites (mesiobuccal, buccal, and distolingual) per tooth were examined. Gingival recession and pocket depth and CAL were recorded. | 34.7 | NCEP-ATP III | 16.9 | OR (95% CI) 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| 39 | Tanaka et al.[59] | PD to MetS | Retrospective | 3722 | 22.2 | 44.5 ± 8.2 years | Periodontal status was assessed in terms of the PD and CAL at the mesio-buccal and mid-buccal sites for all teeth except for the third molars. | 32.7 | IDF 2009 | 11.1 | OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.16–1.77 |

| 40 | Abdalla-Aslan et al.[60] | MetS to PD | Cross-sectional | 470 | 54.2 | 55.8 | AAP | 75.3 | NCEP-ATP III | 37.4 | OR= 14.28, 95% CI: 6.66–31.25 |

| 41 | Kim et al.[61] | PD to MetS | Cross-sectional | 8314 | 53.5 | 57 | CPI code 3 -4 | 37 | NCEP-ATP III | 32.2 | OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.26–1.61 |

| 42 | Nascimento et al.[62] | MetS to PD | Data part of longitudinal study | 539 | 50 | 31 | AAP/CDC | 37.3 | NCEP-ATP III | 13.3 | Results from the final SEM revealed that MetS is positively associated with “advanced” [coef. 0.11; P-value 0.01; comparative fit index (CFI): 0.99; Tucker Lewis index (TLI): 0.99; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA): 0.01 (95% CI: 0.00–0.02)] |

| 43 | Ruiz[63] | Bi-directional | Cross-sectional | 1761 | 51.1 | ≥ 30 years | AAP/CDC | 49.27 | IDF 2009 | 42.8 | OR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.60–1.28 |

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

A random-effects model was used to determine the pooled prevalence and 95% CI. The general effect size was obtained using the reported OR for the PD to MetS and MetS to PD. The heterogeneity of the study results was assessed using I2 test. Significant heterogeneity was considered for P < 0.10 and I2 > 50%. A subgroup analysis considered the directionality (MetS to PD and PD to MetS), gender, and study design. Statistical analysis was performed by the use of the Open Meta Analyst (version 3.13).

RESULTS

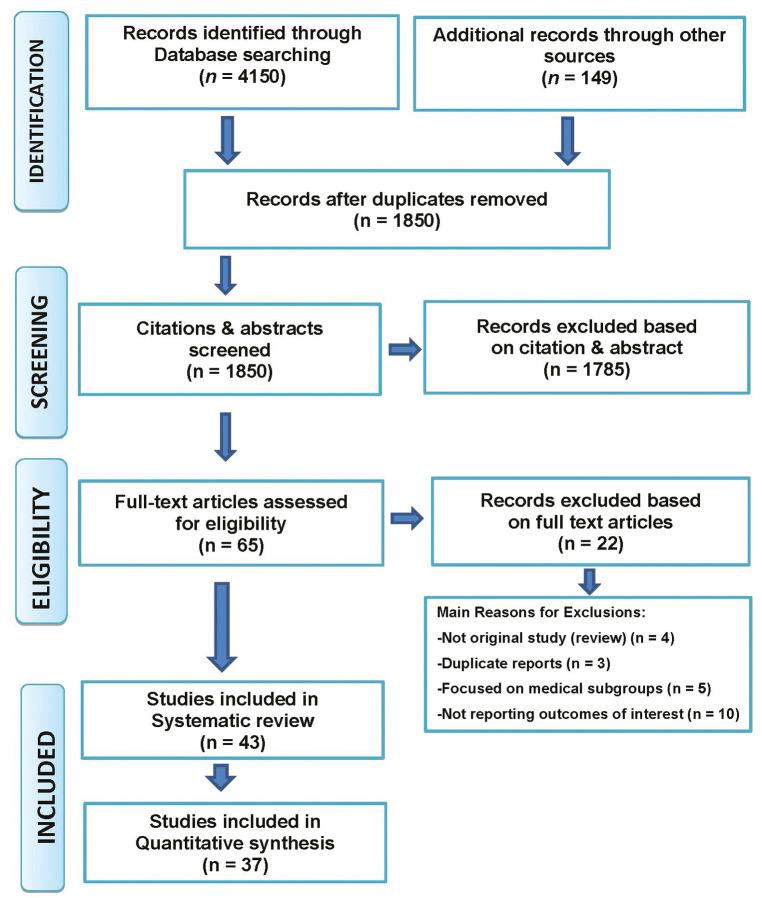

Of the 4150 titles, 65 were considered suitable after initial screening. After the full-text reading, 22 papers were excluded due to: (1) not reporting outcomes of interest (n = 10); (2) duplicate reports (n = 3); (3) reviews (n = 4); and (4) focussed on medical subgroups (n = 5) [Figure 1]. Hence, a total of 43 studies were included in the qualitative analysis and 37 papers considered in the quantitative analysis. These studies were published in various countries of the world. The study participants ranged from 125 patients in a study by Thanakun et al.[43] and Iwasaki et al.[45] to 33,740 in the Taiwanese population by Tu et al.[40] (median number of subjects 941). Six studies included data as part of longitudinal studies: Morita et al.[12]; Nesbitt et al.[33]; Lee et al.[42]; Iwasaki et al.[45]; Nascimento et al.[62]; and Shearer et al.[64] Six studies were case–control studies: Li[29]; Han[46]; Thanakun et al.[43]; Jaramillo et al.[50]; Koo and Hong[56]; and Pham,[57] and the remaining 31 studies were cross-sectional.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search studies for systematic review

Only one study was carried out in adolescents in whom gingivitis was assessed.[65] The criteria of periodontitis ranged from radiographically as mentioned by Nesbitt et al.[33] to clinically reported by Page and Eke.[20] In some instances, arbitrary criteria of PPD or CAL were considered in this study. The periodontitis ranged from 6.3% to 80% among various studies. However, the percentage of subjects classified as having MetS across the included studies varied from 5.0% to 85%.

QUALITY ASSESSMENT

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was utilized to evaluate the quality of the studies. The quality of the study was judged using the star system of rating adhering to the criteria based on the selection of the study groups, the comparability, and exposure or the outcome of interest. The results varied across the selected studies, which are shown in Table 2. The scale ranged from 0 to 9 stars for each article. More stars indicated a higher quality of the study.

Table 2.

The Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale

| Study (author, year, ref.) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shimazaki et al., 2007[26] | ** | ** | ** |

| D'Aiuto et al., 2008[11] | **** | ** | ** |

| Khader et al., 2008[27] | *** | * | ** |

| LI et al., 2009[29] | ** | * | ** |

| Morita et al., 2009[30] | ** | * | ** |

| Kushiyama et al., 2009[28] | * | ** | ** |

| Andriankaja et al., 2010[16] | *** | ** | ** |

| Nesbitt et al., 2010[33] | ** | * | * |

| Benguigui et al., 2010[31] | **** | ** | ** |

| Han et al., 2010[32] | *** | ** | ** |

| Timonen et al., 2010[34] | *** | * | * |

| Bensley et al., 2011[35] | ** | * | ** |

| Kwon et al., 2011[13] | ** | ** | ** |

| Chen et al., 2011[36] | ** | ** | * |

| Han, 2012[46] | ** | ** | ** |

| Fukui et al., 2012[37] | *** | ** | *** |

| Tu et al., 2013[40] | ** | * | * |

| Sora et al., 2013[39] | *** | ** | *** |

| Furuta et al., 2013[38] | **** | * | ** |

| Lamonte et al., 2014[41] | **** | ** | ** |

| Thanakun et al., 2014[43] | ** | * | * |

| Alhabashneh et al., 2015[44] | *** | ** | *** |

| Minagawa et al., 2015[47] | *** | ** | ** |

| Iwasaki et al., 2015[45] | ** | ** | ** |

| Jaramillo et al., 2017[50] | *** | ** | ** |

| Kumar et al., 2016[49] | *** | ** | *** |

| Gomes-Filho et al., 2016[48] | *** | ** | *** |

| Musskopf et al., 2017[52] | *** | ** | ** |

| Kikui et al., 2017[51] | *** | ** | ** |

| Kim et al., 2018[55] | *** | ** | ** |

| Pham, 2018[57] | *** | ** | ** |

| Koo and Hong, 2018[56] | ** | ** | ** |

| Nascimento et al., 2018[62] | *** | ** | *** |

| Abdalla-Aslan et al., 2019[60] | *** | ** | *** |

| Kim et al., 2019[61] | *** | ** | ** |

SUBGROUP ANALYSIS

Many studies did not report data gender-wise, but studies that reported data based on gender showed a higher prevalence of females’ MetS. So we performed a subgroup analysis based on the gender of the study participants.

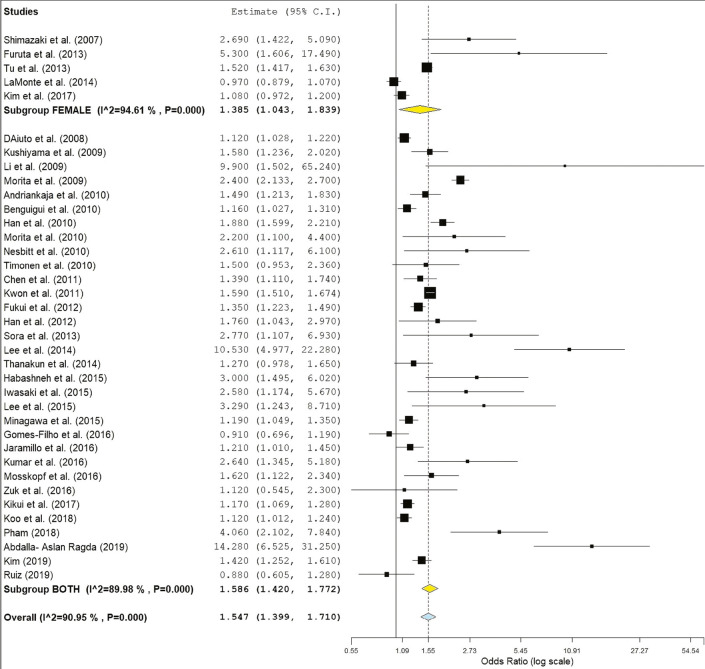

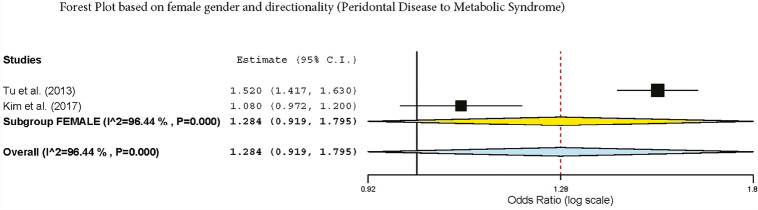

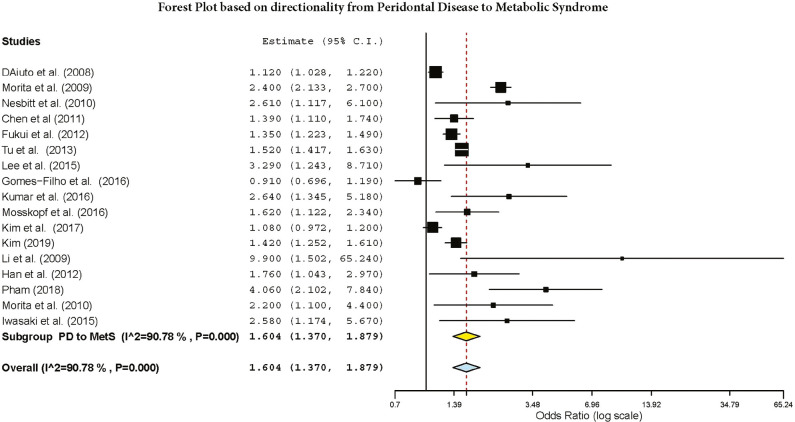

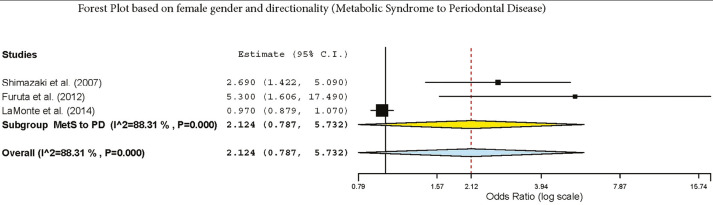

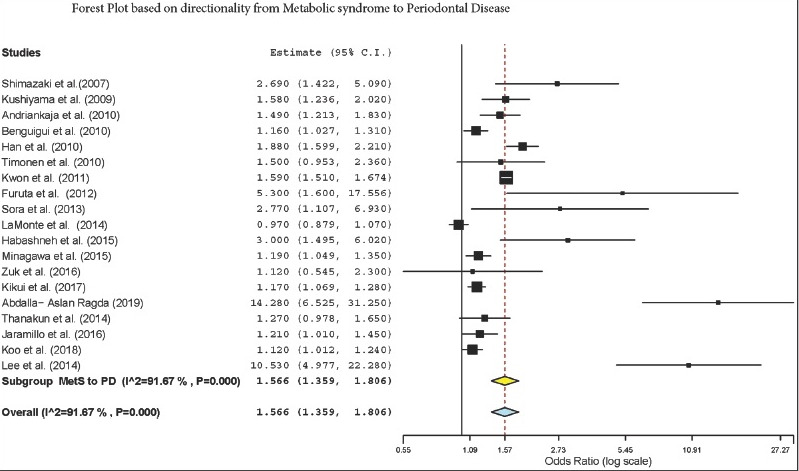

The subgroup analysis by gender demonstrated a crude OR of 1.385 (95%: 1.043–1.839, I2 = 94.61%, P < 0.001) in females and 1.58 (95% CI: 1.42–1.77, I2 = 89.9%, P < 0.001) for both genders [Figure 2]. The subgroup analysis by directionality showed crude ORs of 1.28 (95% CI: 0.91–1.79, I2 = 96.44%, P = 0.000) for PD to MetS for females [Figure 3] and 1.60 (95% CI: 1.37–1.87, I2 = 90.87%, P = 0.000) for overall PD to MetS for both genders [Figure 4]. The subgroup analysis by directionality showed crude ORs of 2.12 (95% CI: 0.78–5.73, I2 = 88.31%, P < 0.001) for MetS to PD for females [Figure 5] and 1.56 (95% CI: 1.35–1.80, I2 = 91.67%, P < 0.001) for MetS to PD for both genders [Figure 6].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of gender and MetS

Figure 3.

Forest plot of PD to MetS in females

Figure 4.

Forest plot of overall PD to MetS

Figure 5.

Forest plot of MetS to PD in females

Figure 6.

Forest plot of overall MetS to PD

DISCUSSION

In this study, relevant publications that described the prevalence of MetS and PDs and vice versa were selected regardless of the criteria used for defining periodontitis and MetS. Random-effects meta-analysis was used to pool the prevalence. Heterogeneity was explored using formal and subgroup analyses based on gender (females alone vs. both genders), directionality (overall PD to MetS vs. overall MetS to PD), and directionality among females (female PD to MetS vs. female MetS to PD). Study quality and publication bias were also explored.

The study findings revealed no clear association between MetS and PD in females. However, gender predisposition can depend on multiple factors such as hormones, genetics, behavior, stress, to name a few. The changes in hormone levels occurring during puberty, pregnancy, menstruation, and menopause, and those that occur with the use of hormonal supplements, have long been associated with the development of gingivitis. One research carried out in Korea by Lee et al. in 2015[65] concluded that the probability of gingivitis is increased among those with three or more positive markers of the MetS, and HDL cholesterol levels are a significant risk factor.

To date, there has been no unified concept of MetS that can be extended to adolescents, and current adult-based meanings of MetS might not be sufficient to solve the issue in this age group; thus, the word “high risk of MetS” has been used instead of MetS. There were no indicators of any hormonal influences at the moment.

Three studies were conducted in females with the directionality of MetS to PD (Shimazaki et al.,[26] Furuta et al.,[38] and LaMonte et al.[41]). Shimazaki concluded that if participants have more components of MetS, PD’s likelihood increased depending on their components. However, it was reported that the MetS components were not consistently associated with periodontal measures in older post-menopausal women.[41]

Estrogen insufficiency could affect oral soft and hard tissues. Women in their post-menopausal are likely to have osteoporosis, thereby increasing the risk of periodontal destruction.[66] Likewise, postmenopausal women have demonstrated altered lipid metabolism and increased risk for cardiovascular diseases.[67,68,69,70]

Tu et al.[40] explored the directionality of PD to MetS. A small but statistically significant association was found between MetS and PD among Taiwanese females, and a weaker association in Taiwanese males was observed. It could be due to relatively weaker influence of periodontal infection on MetS than stronger genetic and environmental risk factors. Moreover, the periodontal infections “compete” with these factors in their independent effects on MetS. These competing effects phenomenon may be larger in men than in women as men tend to have a less healthy lifestyle; hence, smaller ORs were reported in men.[40]

Six longitudinal studies were included in this review. According to a 4-year longitudinal study by Morita in 2010, the presence of periodontal pockets was associated with increased risk of MetS components. Similarly, another longitudinal study observed that individuals with a more significant number of MetS components were more likely to have PD.[42] A 3-year follow-up study by Iwasaki et al.[45] reported that the participants with MetS had a significantly increased risk of PD, with a higher positive correlation in females. As the reported longitudinal trials are very minimal and inconclusive, further interventional studies on periodontal therapy-induced changes in the condition of MetS in patients with PD and MetS could be required to establish the causal relationship between PD and MetS.

In this review, 31 studies were cross-sectional, with the reported 24% prevalence of MetS. Although several studies investigated the relationship between MetS and PD, none has reviewed this relationship exclusively among females. The influence of gender on pathophysiology and clinical expression of MetS is of great significance, given the alarming increase in the prevalence of MetS among females.

This review found 14 studies that reported a higher prevalence of association between PD and Mets in females, and 11 studies reported it to be higher in males. On the contrary, Thanakun et al.[43] reported no gender difference in the association between periodontitis and MetS.

The variability in results may be due to selection bias, differences in diagnostic criteria for PD and MetS, or the improper control of confounding factors. Moreover, high heterogeneity has been observed across reported studies. One of the likely causes of heterogeneity is the study area (urban/rural) from where study subjects were considered for examination. Moreover, MetS differed between males and females, with higher prevalence in females than that identified by the subgroup analysis. Within the male and female subgroups, a high between-study heterogeneity on the prevalence of MetS was observed. The quality evaluation review indicates that many studies do not meet the “adequate sample size” criteria. Another issue was that data collection was carried out in certain studies without sufficient coverage of the identified sample.

STRENGTH AND LIMITATIONS

This review’s strength is the comprehensiveness of the method, which involved looking for various databases, well-defined requirements for inclusion/exclusion, and thorough usage of reference lists. However, there are drawbacks to our systematic review and meta-analysis. This study did not consider non-English publications and local-level journals that are not accessible via large academic databases. In addition, there were difficulties in having a universally accepted clinical case definition of periodontitis. The definitions of MetS, age ranges, waist circumference, and research settings were not similar, resulting in a lack of homogeneity in the assessment of MetS. Moreover, longitudinal, cross-sectional, and case–control studies were taken together, which may have caused outcome bias. Hence, the outcome of this review is affected by many factors.

CONCLUSION

This study lacks convincing proof of a link between MetS and periodontitis in females when compared with an overall association between MetS and PD. Directionality indicated higher odds of having MetS and PD than PD and MetS among females. Further longitudinal and treatment trials are needed to confirm these associations among females.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Not applicable.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

Not applicable.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation, the IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. Available from: https://www.idf.org/e-library/consensusstatements/60-idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolicsyndrome. accessed August 10, 2017.

- 2.Ranasinghe P, Mathangasinghe Y, Jayawardena R, Hills AP, Misra A. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the Asia-Pacific region: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Bilbeisi AH, Shab-Bidar S, Jackson D, Djafarian K. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related factors among adults in Palestine: A meta-analysis. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27:77–84. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildrum B, Mykletun A, Hole T, Midthjell K, Dahl AA. Age-specific prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program: The Norwegian HUNT 2 study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Könönen E, Müller HP. Microbiology of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2014;65:46–78. doi: 10.1111/prd.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nibali L, D’Aiuto F, Griffiths G, Patel K, Suvan J, Tonetti MS. Severe periodontitis is associated with systemic inflammation and a dysmetabolic status: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:931–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsakos G, Sabbah W, Hingorani AD, Netuveli G, Donos N, Watt RG, et al. Is periodontal inflammation associated with raised blood pressure? Evidence from a national US survey. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2386–93. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833e0fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kebschull M, Demmer RT, Papapanou PN. “Gum bug, leave my heart alone!”—Epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:879–902. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suvan J, D’Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults. A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e381–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Aiuto F, Sabbah W, Netuveli G, Donos N, Hingorani AD, Deanfield J, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with severe periodontitis in a large U.S. population-based survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3989–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita T, Yamazaki Y, Mita A, Takada K, Seto M, Nishinoue N, et al. A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2010;81:512–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon YE, Ha JE, Paik DI, Jin BH, Bae KH. The relationship between periodontitis and metabolic syndrome among a Korean nationally representative sample of adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:781–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P. Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:401–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han W, Ji T, Wang L, Yan L, Wang H, Luo Z, et al. Abnormalities in periodontal and salivary tissues in conditional presenilin 1 and presenilin 2 double knockout mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;347:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andriankaja OM, Sreenivasa S, Dunford R, DeNardin E. Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi T, Bandow K, Kakimoto K, Machigashira M, Matsuyama T, Matsuguchi T. Oxidative stress causes alveolar bone loss in metabolic syndrome model mice with type 2 diabetes. J Periodont Res. 2009;44:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzo M, Cappello F, Marfil R, Nibali L, Marino Gammazza A, Rappa F, et al. Heat-shock protein 60kDa and atherogenic dyslipidemia in patients with untreated mild periodontitis: A pilot study. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2012;17:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0315-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Nagasawa T, Chen Y, Ushida Y, Kobayashi H, Takeuchi Y, et al. Molecular mimicry of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans with beta2 glycoprotein I. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23:401–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1387–99. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonetti MS, Claffey N. European Workshop in Periodontology Group C. Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. Group C Consensus Report of the 5th European Workshop in Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl. 6):210–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. . Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. pp. 6–39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biesbrock AR, Bartizek RD, Gerlach RW, Terézhalmy GT. Oral hygiene regimens, plaque control, and gingival health: A two-month clinical trial with antimicrobial agents. J Clin Dent. 2007;18:101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimazaki Y, Saito T, Yonemoto K, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Yamashita Y. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to periodontal disease in Japanese women: The Hisayama study. J Dent Res. 2007;86:271–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khader Y, Khassawneh B, Obeidat B, Hammad M, El-Salem K, Bawadi H, et al. Periodontal status of patients with metabolic syndrome compared to those without metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2048–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kushiyama M, Shimazaki Y, Yamashita Y. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li P, He L, Sha YQ, Luan QX. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:541–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita T, Ogawa Y, Takada K, Nishinoue N, Sasaki Y, Motohashi M, et al. Association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:248–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benguigui C, Bongard V, Ruidavets JB, Chamontin B, Sixou M, Ferrières J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and periodontitis: A cross-sectional study in a middle-aged French population. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:601–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han DH, Lim SY, Sun BC, Paek D, Kim HD. The association of metabolic syndrome with periodontal disease is confounded by age and smoking in a Korean population: The Shiwha-Banwol Environmental Health Study. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:609–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesbitt MJ, Reynolds MA, Shiau H, Choe K, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. Association of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:238–42. doi: 10.1007/bf03324802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timonen P, Niskanen M, Suominen-Taipale L, Jula A, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P. Metabolic syndrome, periodontal infection, and dental caries. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1068–73. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bensley L, VanEenwyk J, Ossiander EM. Associations of self-reported periodontal disease with metabolic syndrome and number of self-reported chronic conditions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen LP, Hsu SP, Peng YS, Chiang CK, Hung KY. Periodontal disease is associated with metabolic syndrome in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:4068–73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukui N, Shimazaki Y, Shinagawa T, Yamashita Y. Periodontal status and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged Japanese. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1363–71. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furuta M, Shimazaki Y, Takeshita T, Shibata Y, Akifusa S, Eshima N, et al. Gender differences in the association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease: The Hisayama study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:743–52. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sora ND, Marlow NM, Bandyopadhyay D, Leite RS, Slate EH, Fernandes JK. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis in Gullah African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:599–606. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu YK, D’Aiuto F, Lin HJ, Chen YW, Chien KL. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and diagnoses of periodontal diseases among participants in a large Taiwanese cohort. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:994–1000. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaMonte MJ, Williams AM, Genco RJ, Andrews CA, Hovey KM, Millen AE, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease measures in postmenopausal women: The Buffalo OsteoPerio study. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1489–501. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee KS, Kim EK, Kim JW, Choi YH, Mechant AT, Song KB, et al. The relationship between metabolic conditions and prevalence of periodontal disease in rural Korean elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thanakun S, Watanabe H, Thaweboon S, Izumi Y. Association of untreated metabolic syndrome with moderate to severe periodontitis in Thai population. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1502–14. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alhabashneh R, Khader Y, Herra Z, Asa’ad F, Assad F. The association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome among outpatients with diabetes in Jordan. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:67. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwasaki M, Sato M, Minagawa K, Manz MC, Yoshihara A, Miyazaki H. Longitudinal relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease among Japanese adults aged ≥70 years: The Niigata study. J Periodontol. 2015;86:491–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han DH, Lim S, Paek D, Kim HD. Periodontitis could be related factors on metabolic syndrome among Koreans: A case–control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:30–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minagawa K, Iwasaki M, Ogawa H, Yoshihara A, Miyazaki H. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis in 80-year-old Japanese subjects. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:173–9. doi: 10.1111/jre.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomes-Filho IS, das Mercês MC, de Santana Passos-Soares J, Seixas da Cruz S, Teixeira Ladeia AM, Trindade SC, et al. Severity of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome: Is there an association? J Periodontol. 2016;87:357–66. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar N, Bhardwaj A, Negi PC, Jhingta PK, Sharma D, Bhardwaj VK. Association of chronic periodontitis with metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20:324–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.183096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaramillo A, Contreras A, Lafaurie GI, Duque A, Ardila CM, Duarte S, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and chronic periodontitis in Colombians. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:1537–44. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1942-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kikui M, Ono T, Kokubo Y, Kida M, Kosaka T, Yamamoto M. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and objective masticatory performance in a Japanese general population: The Suita study. J Dent. 2017;56:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Musskopf ML, Daudt LD, Weidlich P, Gerchman F, Gross JL, Oppermann RV. Metabolic syndrome as a risk indicator for periodontal disease and tooth loss. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:675–83. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin HS. The number of teeth is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome: A Korean nationwide population-based study. J Periodontol. 2017;88:830–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2017.170089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doğan ES, Kırzıoğlu FY, Doğan B, Fentoğlu Ö, Kale B, Çarsancaklı SA, et al. The role of menopause on the relationship between metabolic risk factors and periodontal disease via salivary oxidative parameters. J Periodontol. 2018;89:331–40. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim OS, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Lee YH, Kim OJ, Kim YJ, et al. The severity of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in Korean population: The Dong-gu study. J Periodontal Res. 2018;53:362–8. doi: 10.1111/jre.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koo HS, Hong SM. Prevalence and risk factors for periodontitis among patients with metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2018;16:375–81. doi: 10.1089/met.2018.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pham T. The association between periodontal disease severity and metabolic syndrome in Vietnamese patients. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018;16:484–91. doi: 10.1111/idh.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shearer DM, Thomson WM, Cameron CM, Ramrakha S, Wilson G, Wong TY, et al. Periodontitis and multiple markers of cardiometabolic risk in the fourth decade: A cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:615–23. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanaka A, Takeuchi K, Furuta M, Takeshita T, Suma S, Shinagawa T, et al. Relationship of toothbrushing to metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:538–47. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdalla-Aslan R, Findler M, Levin L, Zini A, Shay B, Twig G, et al. Where periodontitis meets metabolic syndrome—The role of common health-related risk factors. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46:647–56. doi: 10.1111/joor.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JS, Kim SY, Byon M-J, Lee J-H, Jeong S-H, Kim JB. Association between periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in a Korean nationally representative sample of adults aged 35–79 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:E2930. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16162930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nascimento GG, Leite FRM, Peres KG, Demarco FF, Corrêa MB, Peres MA. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: A structural equation modeling approach. J Periodontol. 2019;90:655–62. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruiz B. The association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome among Unites States adults: Analysis of NHANES 2013–2014. Georgia State University; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shearer D, Thomson W, Cameron C, Ramrakha S, Wilson G, Wong TY, et al. Periodontitis and multiple markers of cardiometabolic risk in the fourth decade: A cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:615–23. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee KS, Lee SG, Kim EK, Jin HJ, Im SU, Lee HK, et al. Metabolic syndrome parameters in adolescents may be determinants for the future periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:105–12. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Otomo-Corgel J. Dental management of the female patient. Periodontol 2000. 2013;61:219–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gohlke-Bärwolf C. Coronary artery disease—Is menopause a risk factor? Basic Res Cardiol. 2000;95(Suppl. 1):I77–83. doi: 10.1007/s003950070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zimmet P, Magliano D, Matsuzawa Y, Alberti G, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome: A global public health problem and a new definition. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12:295–300. doi: 10.5551/jat.12.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han K, Park JB. Age threshold for moderate and severe periodontitis among Korean adults without diabetes mellitus, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and/or obesity. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7835. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zuk A, Quiñonez C, Lebenbaum M, Rosella LC. The association between undiagnosed glycaemic abnormalities and cardiometabolic risk factors with periodontitis: Results from 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:132–41. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.