Abstract

DNA polymerase μ is a Family X member that participates in repair of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) by non-homologous end joining. Its role is to fill short gaps arising as intermediates in the process of V(D)J recombination and during processing of accidental double strand breaks. Pol μ is the only known template-dependent polymerase that can repair non-complementary DSBs with unpaired 3´primer termini. Here we review the unique properties of Pol μ that allow it to productively engage such a highly unstable substrate to generate a nick that can be sealed by DNA Ligase IV.

Keywords: DNA polymerase μ, Family X DNA polymerases, nonhomologous end-joining, DNA double strand break repair

Introduction

Genomic DNA is constantly subjected to damage by products of cellular metabolism and by environmental factors that threaten the integrity of the genetic information. The most cytotoxic forms of DNA damage are DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). DNA DSBs are formed during programmed cellular events such as V(D)J recombination for assembly of T-cell receptor- and immunoglobulin antigen receptor genes and during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. In addition, DSBs may arise as a consequence of ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutics, reactive oxygen species or inadvertent processing by DNA metabolizing enzymes. Failure to repair DSBs has deleterious consequences, resulting in loss of genetic information, chromosomal translocations, and predisposition to cancer and other diseases [1]. Among pathways for repair of DSBs, the predominant one is nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) (Figure 1A) [2].

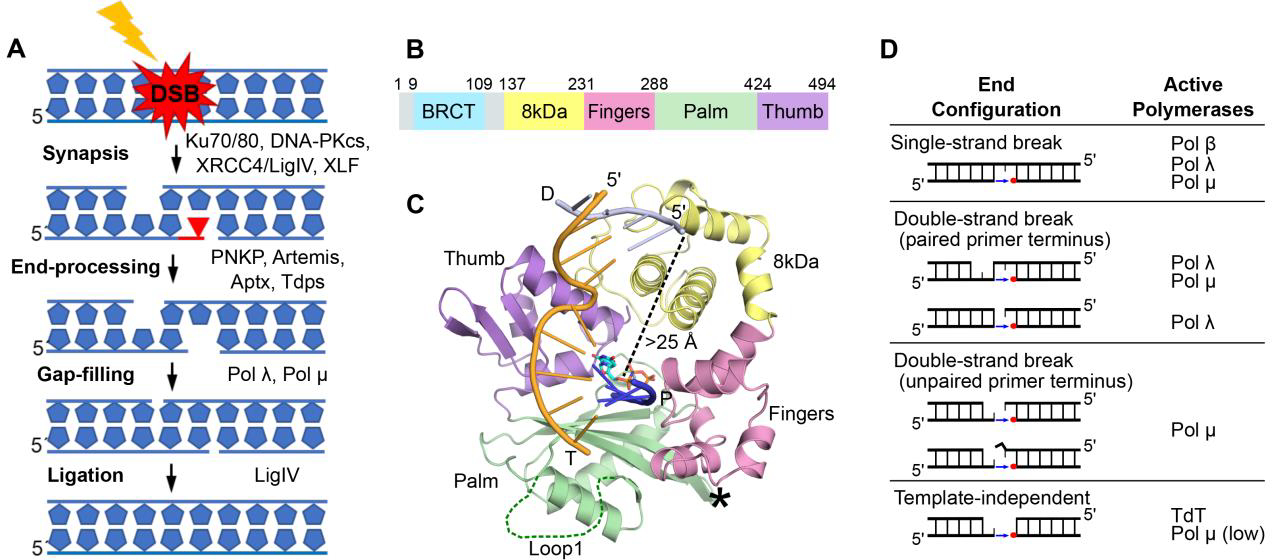

Figure 1:

Involvement of Pol μ in NHEJ. A. Schematic of DSB synapsis, DNA end-processing, and religation in the NHEJ pathway; DNA-PKcs, catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase; LigIV, ligase IV; PNKP, polynucleotide kinase phosphate; Aptx, aprataxin; Tdps, tyrosine phosphodiesterases. B. Pol μ subdomain architecture. C. Crystal structure of the Pol μ catalytic domain (hPolμΔ2 Loop2 deletion variant with improved crystallizability) bound to a 1nt-gapped DNA substrate (PDB ID code 4M04[4], template strand T in orange; upstream primer P in blue, downstream primer D in gray). Disordered Loop1 and deleted Loop2 are marked by a dark green dashed line and a black asterisk, respectively. Subdomains are labeled and colored as in B. The pol μ structures discussed in this review are all of the hPolμΔ2’s catalytic domain. D. Family X polymerases exhibit different substrate specificities in DNA repair, based on DNA end configuration[10].

Unlike repair by homologous recombination (HR), which relies on an intact sister chromatid and is limited to the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, NHEJ functions throughout the cell cycle and is achieved by directly rejoining broken DNA ends with minimal or no homology [2]. The critical step in NHEJ is bringing into proximity and stabilizing the DNA ends to form a synapsis that allows ligation. This is accomplished by the core proteins of the NHEJ complex, including the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, XRCC4/LigIV, XRCC4-like factor (XLF) and DNA-PKcs [2, 3]. Broken DNA ends are often damaged or have structural modifications that must be processed to allow ligation. The multiprotein NHEJ machinery has the flexibility to process different DNA-end configurations by recruiting additional end-cleaning factors. Among the different end-processing enzymes are nucleases and DNA polymerases that can process the DNA ends and/or fill short gaps, respectively [2]. The vital task of mending a DSB often is accomplished at the expense of compromised fidelity that results in lost or mismatched nucleotides.

Gap-filling during NHEJ is primarily conducted by Family X DNA polymerases. A characteristic structural feature for Family X members is the presence of the 8 kDa domain, which facilitates gap-filling by binding to the 5énd of the DNA break, allowing the polymerase (pol) to bridge both ends of the gap (Figure 1B–C)[4]. Four Family X members, pols β, λ, μ and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) are present in human cells, but only pols λ, μ and TdT have been implicated in mammalian NHEJ. All three have an N-terminal BRCT domain through which they interact with the Ku/DNA-PKcs and XRCC4/LigIV complexes (Figure 1B). Pol β’s primary role is in base-excision repair (BER). TdT is expressed in developing T and B lymphocytes and its primary role is to generate immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor sequence diversity during V(D)J recombination [3]. This is in contrast to pols λ and μ, which are ubiquitously expressed and function both in V(D)J recombination and general NHEJ. Pol λ is also involved in repair of SSBs during BER.

The reliance of classical NHEJ on two different family X polymerases is necessitated by their distinct DNA substrate preferences (Figure 1D) [5]. Pols μ and λ show some substrate-use overlap: both can fill 1-nt gaps in the context of a single strand break (SSB) in vitro, and pol μ can repair a complementary DSB (containing at least one base pair of microhomology), though the majority of synthesis on such substrates is conducted by pol λ [5]. However, pol λ is unable to use a noncomplementary DSB substrate with an unpaired primer terminus. Pol μ is the only known polymerase that can use such a substrate, extending the 3óverhang of one DNA end while using as template the 3óverhang of the opposing DNA end. To extend a 3óverhang, Pol μ must be able to stabilize an unpaired primer terminus. The following structural determinants of synthesis from an unpaired primer terminus have been identified.(i) Residues that ensure proper alignment of the primer terminus for catalysis (Figure 2A). This includes Arg416, which links the primer terminus to the protein, and His329, which bridges the primer terminal phosphate and the γ-phosphate of the incoming nucleotide [4, 6, 7]. (ii) Residues Gly174 and Arg175 in the 8 kDa domain, which facilitate binding and stabilization of the 5´-phosphate end of the gap (Figure 2B). Mutations of these residues have been associated with human cancer [8]. (iii) Loop1, a structural element that is present in all Family X siblings but varies in sequence and length. This loop is believed to act as a surrogate for an absent or discontinuous template strand [9, 10]. In pol μ and TdT, which do not rely on the template strand to stabilize the primer terminus, Loop1 is longer and likely has a greater range of motion. Without Loop1, pol μ cannot repair noncomplementary DSBs, and both pol μ and TdT lose template-independent synthesis activity. Loop1 is shorter in pol λ, which when the primer terminus is paired can repair noncomplementary DSBs containing a blunt end. In pol β, the corresponding region to Loop 1 is merely a turn between β-strands 3 and 4 [9, 10].

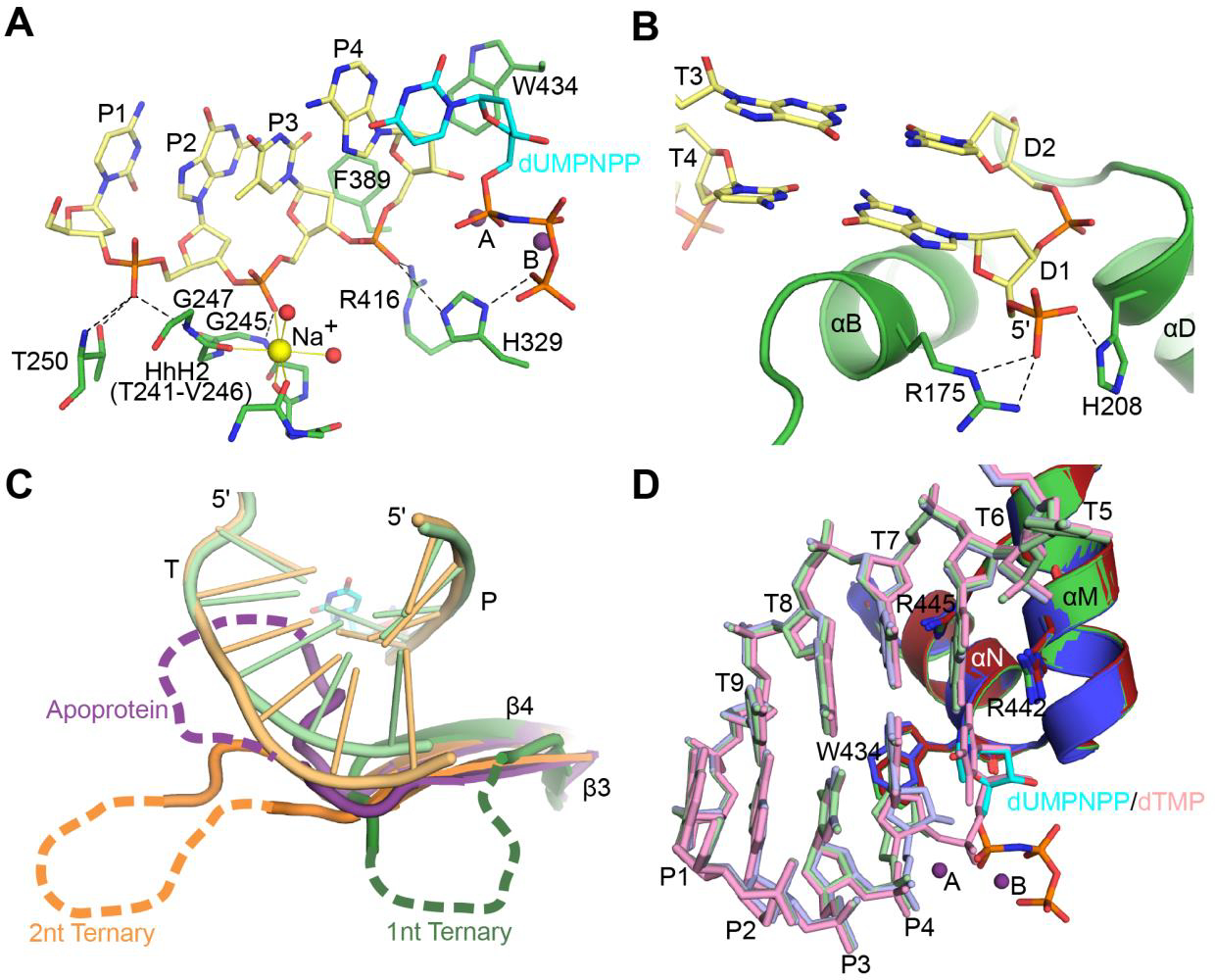

Figure 2:

Pol μ provides a rigid scaffold for binding broken ends. A. Interaction of Pol μ catalytic domain (green) with the upstream primer strand (khaki) of a 1nt-gapped SSB substrate (PDB ID code 4M04[4], template and downstream primer strands not shown). Hydrogen bonding interactions and ionic interactions with Na+ ion (yellow sphere) in the Helix-hairpin-Helix2 (HhH2) site are indicated by black dashed and solid yellow lines, respectively. B. Interaction of Pol μ 8kDa subdomain (green) with the 5′-phosphorylated downstream primer (khaki). C. Comparison of the trajectories of disordered Loop1 in crystal structures of Pol μ. The hPolμΔ2 catalytic domain apoprotein structure (PDB ID code 4LZD[4], purple) was superimposed with those bound to either a 1nt- (PDB ID code 4M04[4], green) or a 2nt-gapped SSB substrate (PDB ID code 4YD1[12], orange). Loop1 is largely disordered in each structure, but clearly shows varying trajectories for its position. Because the loop occupies the DNA binding cleft in the apoprotein structure, rearrangement must occur before the substrate can bind. Loop1 then likely assumes a conformation that will support and stabilize the conformation of the DNA template strand. D. Pol μ remains largely rigid throughout its catalytic cycle, with no large-scale movements of protein subdomains, DNA substrate, or active site sidechains. Crystal structures of the hPolμΔ2 catalytic domain bound to a 1nt-gapped SSB substrate in binary complex (PDB ID code 4LZG[4], blue and DNA in light blue), pre-catalytic ternary complex (PDB ID code 4M04[4], green; DNA in light green; incoming nonhydrolyzable nucleotide dUMPNPP (cyan); active site Mg2+ ions (purple spheres), and post-catalytic nicked complex (PDB ID code 4M0A[4], red and DNA in pink) were superimposed.

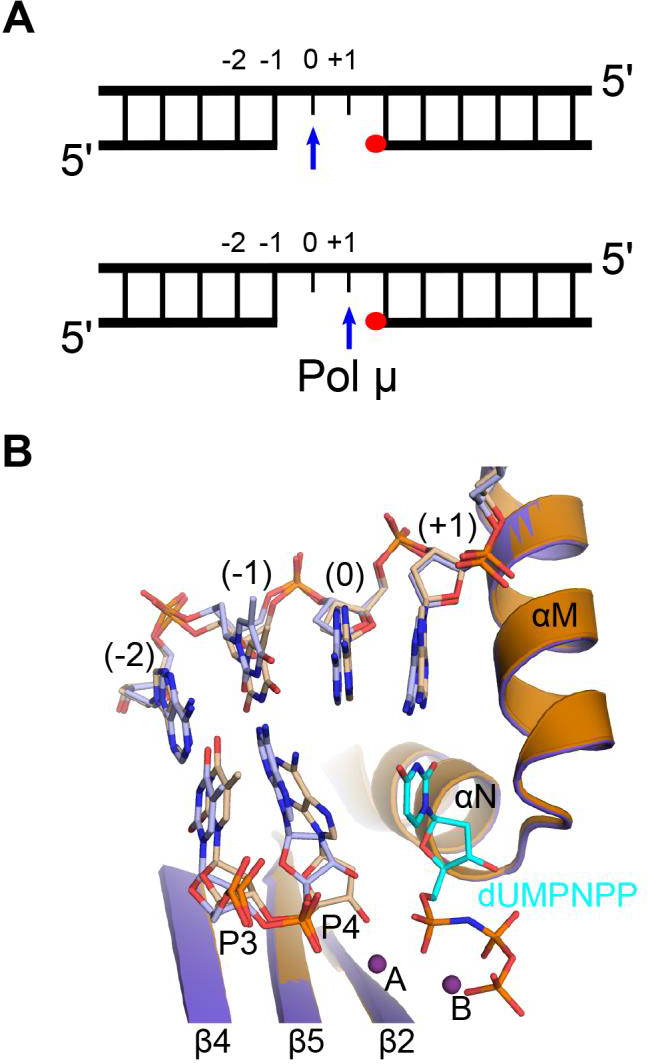

X-ray crystal structures of pol μ that correspond to distinct steps of the enzyme’s catalytic cycle reveal that Loop1 must reposition to allow binding of the DNA duplex (Figure 2C) [4]. Loop1 repositioning is the only major conformational change and occurs early in the pol μ catalytic cycle. No other large-scale conformational changes of the protein subdomains occur in the DNA or in active site side chains (Figure 2D). This contrasts with many studies of other DNA polymerases from different families over the last 30 years, which highlight the important role of dNTP-induced conformational changes for template-dependent synthesis and fidelity. In most polymerases, the “open-to-close” subdomain transition, induced by dNTP binding, is critical for the proper assembly of the polymerase active site and thus, for synthesis fidelity. Even in pol λ, which does not undergo large protein subdomain motion and remains “closed” throughout the catalytic cycle like pol μ, active site assembly requires dNTP-induced Loop1 relocation to allow correct placement of the templating base, and repositioning of active site side chains [11]. Therefore, it is remarkable that in pol μ dNTP binding has little structural effect on active site assembly and catalysis. Upon Loop1 repositioning and binding of the DNA duplex (Figure 2C), pol μ remains rigid throughout subsequent stages of the catalytic cycle (Figure 2D). This inherent rigidity allows pol μ to function as a stable structural platform for highly unstable substrates, like those with unpaired primer termini (Figure 1D), and is critical to how the enzyme engages its DNA substrates. Thus, unlike pols β and λ, pol μ does not require dNTP-induced conformational transition to correctly position the templating nucleotide. Pol μ interacts with single- or double-strand break substrates following a “1-nt gap rule” (Figure 3A). In contrast to all known template-dependent polymerases, pol μ binds the DNA substrate such that the template nucleotide adjacent to the 5énd of the gap is positioned in the nascent base pair binding site, directing the incorporation of the incoming nucleotide. Even if there are template nucleotides upstream, pol μ will “skip ahead” to use as a template the nucleotide closest to the 5énd of the gap (Figure 3B) [12].

Figure 3:

Pol μ ‘skips ahead’ to the 5′-end of gapped DNA substrate. A. Unlike most polymerases, which address the 3′-end of the gap (top), since that is where the next nucleotide will be added (blue arrow), Pol μ directs the templating base closest to the 5′-phosphate (red circle) into the nascent base pair binding side (bottom). B. Superimposed crystal structures of the hPolμΔ2 catalytic domain bound in binary (PDB ID code 4YCX[12], blue and DNA in light blue) and pre-catalytic ternary (PDB ID code 4YD1[12], burnt orange; DNA in khaki, dUMPNPP in cyan, Mg2+ ions as purple spheres). Alignment of the 5′-end templating base (+1) into the nascent base pair binding site is not nucleotide-dependent. The 3′-end templating base (0) is unpaired and is stabilized within the helix by base stacking interactions.

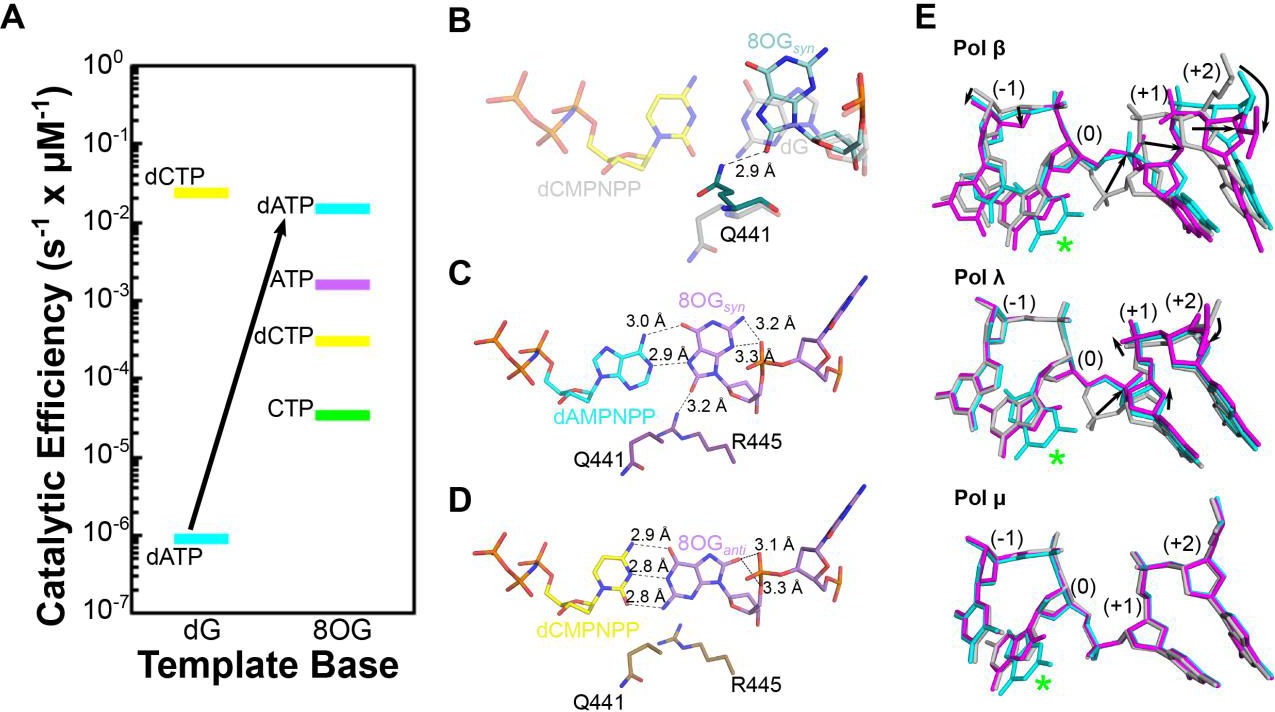

Another unexpected property of pol μ is its behavior opposite a template 8-oxoG, a common oxidative damage found in genomic DNA. 8-oxoG is highly mutagenic due to its dual coding potential. In the anti conformation, 8-oxoG correctly base pairs with C, while in the syn conformation it mispairs with A. Pol μ can incorporate both dCTP and dATP opposite 8-oxoG. However, in contrast to its family siblings pols β and λ, which incorporate dCTP and dATP opposite template 8-oxoG with similar efficiencies, pol μ misincorporates dATP with a 50-fold higher efficiency than dCTP (Figure 4A) [13]. X-ray crystal structures of pol μ complexes with DNA substrates containing 8-oxoG in the templating position indicate that two residues in helix N of the thumb subdomain, Gln441 and Arg445, may contribute to pol μ’s bias for dATP misincorporation. In the structure of the pol μ binary complex bound to a 1-nucleotide gap in DNA, Gln441 assumes a novel conformation that is within hydrogen bonding distance of the 8-oxoG O8 oxygen atom. In all other structures of binary or ternary pre-catalytic pol μ complexes obtained to date, Gln441 rotates away from the DNA and the nucleotide binding pocket to avoid a steric clash with the incoming dNTP (Figure 4B). The putative hydrogen bond between Gln441 and the O8 atom of 8-oxoG may stabilize the syn conformation, predisposing the enzyme to efficient binding of incoming adenine nucleotides. In the pre-catalytic ternary complex of pol μ with an incoming nonhydrolyzable dATP nucleotide analog opposite template 8-oxoG in syn, Arg445 is in position to hydrogen bond with the O8 atom of the template 8-oxoG. Interactions of Arg445 with the N3 and O2 atoms (of purine and pyrimidines, respectively,) in the minor groove are considered fidelity checkpoints. Here, the Arg445 interaction has been “hijacked”, stabilizing a potentially mutagenic intermediate (Figure 4C–D). Together, the structures of pol μ bound to DNA substrates containing a template 8-oxoG reveal that this enzyme accommodates the damaged nucleotide at the active site without any of the DNA substrate distortions observed for its Family X siblings pols β and λ (Figure 4E).

Figure 4:

Pol μ accommodates template 8OG in the nascent base pair site, bypassing it with unique preference for mutagenic adenine nucleotide insertion. A. The catalytic efficiency of Pol Pol μ for insertion of A (dATP in cyan, ATP in purple) and C (dCTP in yellow, CTP in green) nucleotides opposite undamaged (dG, left) or damaged 8OG (right). B. A putative hydrogen bond (dashed black line) between Gln441 (teal) and the syn conformation of the template 8OG (aqua) in a binary complex with 8OG-containing 1nt-gapped DNA substrate (PDB ID code 6P1M[13]) may predispose the Pol μ active for binding of mutagenic adenine nucleotides. Structure of the correctly paired pre-catalytic ternary complex (PDB ID code 6P1V[13], dCMPNPP in transparent yellow opposite undamaged template dG, transparent gray) was superimposed for reference. Mutagenic insertion of adenine nucleotides (C, PDB ID code 6P1N[13], cyan and protein in purple) rather than correct insertion of cytidine (D, PDB ID code 6P1P[13], yellow and protein in brown) opposite a template 8OG (syn conformation, lavender) by Pol μ may be stabilized by an interaction with Arg445. E. Pol μ accommodates the template 8OG without any distortion in the template phosphodiester backbone (bottom), in contrast to the other Family X polymerases (Pol β, top or Pol λ, middle). Pre-catalytic ternary complexes of correctly paired reference structures for Pols β, λ, μ (PDB ID codes 1BPY[21], 2PFO[22], and 6PIV[13], respectively, gray) were superimposed with those of an incoming nonhydrolyzable adenine nucleotide (PDB ID codes 3RJF[23], 5III[24], and 6P1N[13], respectively, cyan) or an incoming nonhydrolyzable cytidine nucleotide (PDB ID codes 4RJI[23], 5IIJ[24], and 6P1P[13], respectively, magenta) opposite a template 8OG (green asterisk). Distortions in the template backbone surrounding the 8OG are indicated by black arrows.

Pol μ selects its nucleotide substrates with the same flexibility it displays for use of unstable or damaged DNA substrates. It incorporates ribonucleotides almost as efficiently as dNTPs into a 1-nucleotide DNA gap[14, 15], and it is believed to primarily use rNTPs during DSB repair in cells [16]. In contrast, the majority of DNA polymerases, including Family X siblings pols β and λ, effectively discriminate against ribonucleotides (Figure 5A). In most polymerases, aromatic residue guard against ribonucleotide incorporation by steric exclusion of the 2´-OH on the rNTP (Figure 5B). While there is no single, bulky side chain functioning as a “steric gate” in Family X polymerases, two aromatic residues, tyrosine and phenylalanine in pol β and λ have been implicated in ribonucleotide discrimination (Figure 5A, inset). However, structural studies suggest that an interaction mediated by the backbone carbonyl of this motif plays a more critical role in ribonucleotide exclusion than the side chains (Figure 5C) [17, 18]. The tyrosine and phenylalanine are not conserved in pols μ or TdT; in their place are glycine and tryptophan residues (Gly433 and Trp434 in pol μ) (Figure 5A, inset). Replacement of Gly433 with a tyrosine increases rNTP discrimination by pol μ while markedly decreaseing its catalytic efficiency [19]. Structural characterization of the catalytic cycle for ribonucleotide incorporation by pol μ reveals that it binds and incorporates a correctly paired ribonucleotide without distorting the DNA or active site geometry (Figure 5C) [14]. These structures together with a mutational analysis of several residues, including Gly433, indicate that the accommodation of the ribonucleotide involves synergistic interactions with multiple active site residues. The accommodation of the rNTP at the active site appears to be facilitated by the backbone flexibility of Gly433 as well as by interactions mediated by residues Trp434 and His329 that stabilize the primer terminus.

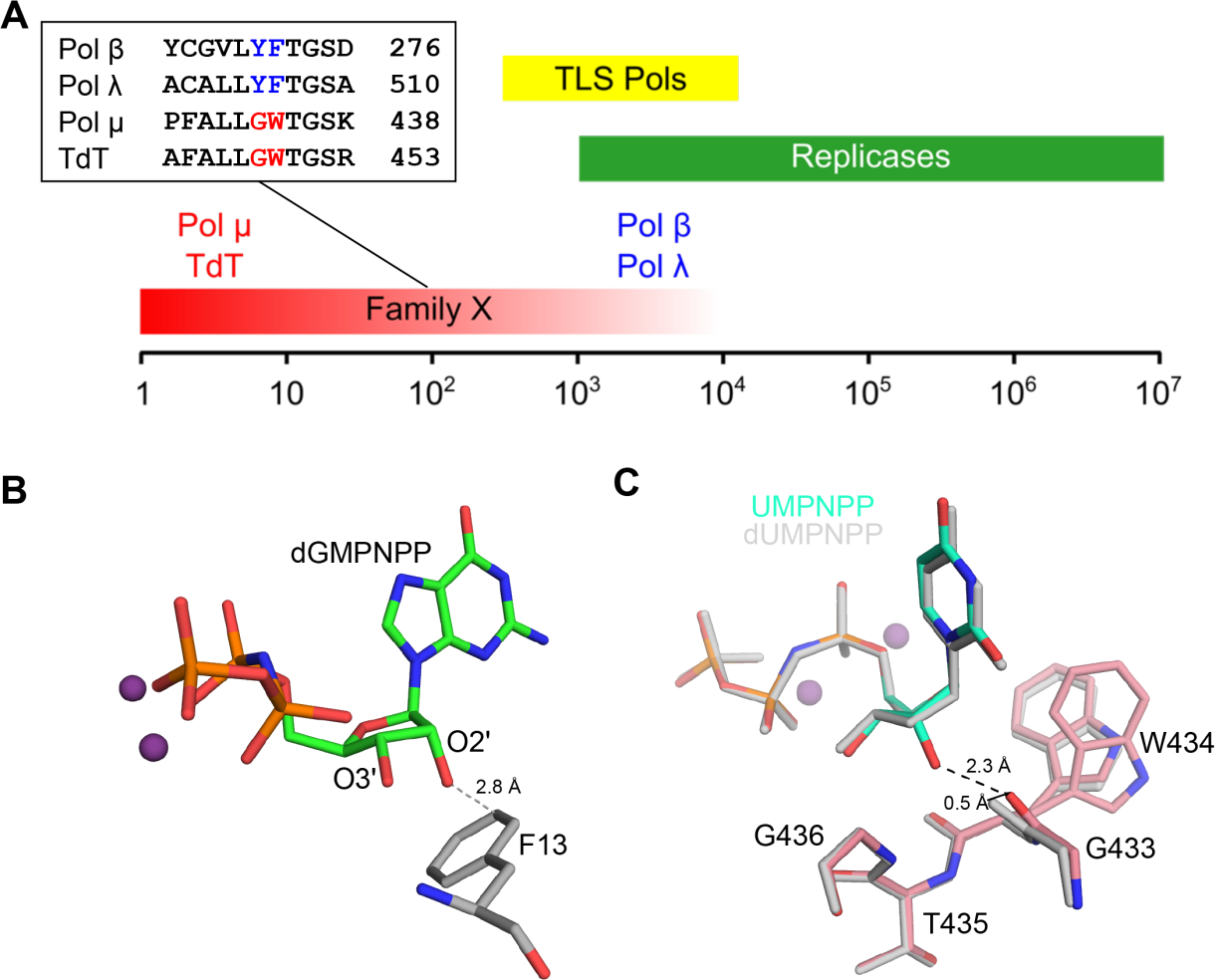

Figure 5:

Pol μ exhibits weak ribonucleotide discrimination. A. Comparison of robusticity of ribonucleotide discrimination (ratio of catalytic efficiencies for dNTP/rNTP) by replicative (green), translesion synthesis (TLS) repair (yellow), and Family X (red) DNA polymerases. The Family X polymerases exhibit a broad range of sugar selectivities, with Pols β and λ excluding rNTPs far more effectively than Pol μ or TdT. An active site motif within the Family X polymerases has been correlated with ribonucleotide discrimination and is highlighted in the inset sequence alignment. B. Most polymerases that exclude binding and incorporation of rNTPs do so through steric exclusion of the rNTP’s 2′-OH by a nearby large, aromatic side chain (E. coli PolIV, PDB ID code 4IR9[25], protein in gray, dGMPNPP in green, Mg2+ ions in purple) c. Pol μ accommodates incoming ribonucleotides with no active site distortion. Superposition of the pre-catalytic ternary complexes of hPolμΔ2 bound to identical 1nt-gapped SSB substrates, with either an incoming dUMPNPP (PDB ID code 4M04[4], gray) or UMPNPP (PDB ID code 5TWP[14], protein in pink, UMPNPP in aqua, Mg2+ ions in purple) show that the 2′-OH on the incoming UMPNPP makes a putatively high-energy, short-range hydrogen bond (black dashed line) with the backbone carbonyl of Gly433. In order to accommodate the UMPNPP without a clash, this carbonyl moves approximately 0.5 Å from its position in the dUMPNPP-bound structure (indicated by a black arrow). Conformational heterogeneity of the Trp434 sidechain (modeled with two alternate conformations) is also observed.

Pol μ readily incorporates ribonucleotides opposite template 8-oxoG, showing a similar preference for incorporation of ATP over CTP that is observed for incorporation of dNTPs. DNA ligase IV, which is known to have higher activity on substrates with a 3′-terminal ribonucleotide [15], can also ligate a nick with a 3ÁMP opposite 8-oxoG [20]. Thus, pol μ’s penchant for incorporating ribonucleotides in order to quickly and efficiently reduce a DSB to a SSB, combined with the fact that intracellular concentrations of ribonucleotides, especially ATP, are considerably higher than deoxynucleotides, support the hypothesis that using ribonucleotides for gap-filling synthesis by pol μ during repair of DSBs, is advantageous for the repair process. The inherent rigidity of Pol μ and its relaxed sugar selectivity are essential properties that allow pol μ to effectively fulfill its in vivo function of generating the optimal DNA substrates for ligation during NHEJ.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported in part by Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health Grants Z01 ES065070 (to T.A.K.) and 1ZIA ES102645 (to L.C.P).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Jackson SP, Bartek J, The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease, Nature, 461 (2009) 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pannunzio NR, Watanabe G, Lieber MR, Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks, J Biol Chem, 293 (2018) 10512–10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Waters CA, Strande NT, Wyatt DW, Pryor JM, Ramsden DA, Nonhomologous end joining: a good solution for bad ends, DNA Repair (Amst), 17 (2014) 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Moon AF, Pryor JM, Ramsden DA, Kunkel TA, Bebenek K, Pedersen LC, Sustained active site rigidity during synthesis by human DNA polymerase mu, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 21 (2014) 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pryor JM, Waters CA, Aza A, Asagoshi K, Strom C, Mieczkowski PA, Blanco L, Ramsden DA, Essential role for polymerase specialization in cellular nonhomologous end joining, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112 (2015) E4537–4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Andrade P, Martin MJ, Juarez R, Lopez de Saro F, Blanco L, Limited terminal transferase in human DNA polymerase mu defines the required balance between accuracy and efficiency in NHEJ, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106 (2009) 16203–16208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Martin MJ, Juarez R, Blanco L, DNA-binding determinants promoting NHEJ by human Polmu, Nucleic Acids Res, 40 (2012) 11389–11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sastre-Moreno G, Pryor JM, Diaz-Talavera A, Ruiz JF, Ramsden DA, Blanco L, Polmu tumor variants decrease the efficiency and accuracy of NHEJ, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 10018–10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Juarez R, Ruiz JF, Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden D, Blanco L, A specific loop in human DNA polymerase mu allows switching between creative and DNA-instructed synthesis, Nucleic Acids Res, 34 (2006) 4572–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nick McElhinny SA, Havener JM, Garcia-Diaz M, Juarez R, Bebenek K, Kee BL, Blanco L, Kunkel TA, Ramsden DA, A gradient of template dependence defines distinct biological roles for family X polymerases in nonhomologous end joining, Mol Cell, 19 (2005) 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Krahn JM, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC, A closed conformation for the Pol lambda catalytic cycle, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 12 (2005) 97–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moon AF, Gosavi RA, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC, Bebenek K, Creative template-dependent synthesis by human polymerase mu, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112 (2015) E4530–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaminski AM, Chiruvella KK, Ramsden DA, Kunkel TA, Bebenek K, Pedersen LC, Unexpected behavior of DNA polymerase Mu opposite template 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-guanosine, Nucleic Acids Res, 47 (2019) 9410–9422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moon AF, Pryor JM, Ramsden DA, Kunkel TA, Bebenek K, Pedersen LC, Structural accommodation of ribonucleotide incorporation by the DNA repair enzyme polymerase Mu, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 9138–9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden DA, Polymerase mu is a DNA-directed DNA/RNA polymerase, Mol Cell Biol, 23 (2003) 2309–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pryor JM, Conlin MP, Carvajal-Garcia J, Luedeman ME, Luthman AJ, Small GW, Ramsden DA, Ribonucleotide incorporation enables repair of chromosome breaks by nonhomologous end joining, Science, 361 (2018) 1126–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cavanaugh NA, Beard WA, Batra VK, Perera L, Pedersen LG, Wilson SH, Molecular insights into DNA polymerase deterrents for ribonucleotide insertion, J Biol Chem, 286 (2011) 31650–31660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gosavi RA, Moon AF, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC, Bebenek K, The catalytic cycle for ribonucleotide incorporation by human DNA Pol lambda, Nucleic Acids Res, 40 (2012) 7518–7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ruiz JF, Juarez R, Garcia-Diaz M, Terrados G, Picher AJ, Gonzalez-Barrera S, Fernandez de Henestrosa AR, Blanco L, Lack of sugar discrimination by human Pol mu requires a single glycine residue, Nucleic Acids Res, 31 (2003) 4441–4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Caglayan M, Pol mu ribonucleotide insertion opposite 8-oxodG facilitates the ligation of premutagenic DNA repair intermediate, Scientific reports, 10 (2020) 940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sawaya MR, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Kraut J, Pelletier H, Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: evidence for an induced fit mechanism, Biochemistry, 36 (1997) 11205–11215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Krahn JM, Pedersen LC, Kunkel TA, Role of the catalytic metal during polymerization by DNA polymerase lambda, DNA Repair (Amst), 6 (2007) 1333–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Batra VK, Shock DD, Beard WA, McKenna CE, Wilson SH, Binary complex crystal structure of DNA polymerase beta reveals multiple conformations of the templating 8-oxoguanine lesion, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109 (2012) 113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Burak MJ, Guja KE, Hambardjieva E, Derkunt B, Garcia-Diaz M, A fidelity mechanism in DNA polymerase lambda promotes error-free bypass of 8-oxo-dG, EMBO J, 35 (2016) 2045–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sharma A, Kottur J, Narayanan N, Nair DT, A strategically located serine residue is critical for the mutator activity of DNA polymerase IV from Escherichia coli, Nucleic Acids Res, 41 (2013) 5104–5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]