Abstract

In this study, the glycopeptide resistance element, Tn1546, in 124 VanA Enterococcus faecium clinical isolates from 13 Michigan hospitals was evaluated using PCR fragment length polymorphism. There were 26 pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) types, which consisted of epidemiologically related and unrelated isolates from separate patients (1992 to 1996). Previously published oligonucleotides specific for regions in the vanA gene cluster of Tn1546 were used to amplify vanRS, vanSH, vanHAX, vanXY, and vanYZ. The glycopeptide resistance element, Tn1546, of E. faecium 228 was used as the basis of comparison for all the isolates in this study. Five PCR fragment length patterns were found, as follows. (i) PCR amplicons were the same size as those of EF228 for all genes in the vanA cluster in 19.4% of isolates. (ii) The PCR amplicon for vanSH was larger than that of EF228 (3.7 versus 2.3 kb) due to an insertion between the vanS and vanH genes (79.2% of isolates). (iii) One isolate in a unique PFGE group had a vanSH amplicon larger than that of EF228 (5.7 versus 2.3 kb) due to an insertion in the vanS gene and an insertion between the vanS and vanH genes. (iv) One isolate did not produce a vanSH amplicon, but when vanS and vanH were amplified separately, both amplicons were the same size as those as EF228. (v) One isolate had a vanYZ PCR product larger than that of EF228 (2.8 versus 1.6 kb). This study shows that in a majority of the VanA E. faecium isolates, Tn1546 is altered compared to that of EF228. A total of 79.2% of the study isolates had the same-size insertion between the vanS and vanH genes. The results of this study show dissemination of an altered Tn1546 in heterologous VanA E. faecium in Michigan hospitals.

In the 1990s, enterococci became the third most common bloodstream infection pathogens among hospitalized patients, with Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis being the predominant species (7, 10, 15, 22, 29). Recent data indicate that up to 50% of E. faecium isolates are resistant to vancomycin (7). Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) present a considerable therapeutic challenge, since E. faecium is also resistant to several key antibiotics, in addition to vancomycin.

Earlier studies have indicated that clonal dissemination is an important mechanism for the spread of vancomycin resistance (5, 6, 8, 13, 17, 20, 23, 29), but there is also a considerable amount of heterogeneity among vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (VREF) strains, even in epidemiologically related isolates (9, 21, 23). There is limited information on the epidemiology of VanA E. faecium in these isolates. The vanA resistance gene cluster, which consists of seven genes, vanS, vanR, vanH, vanA, vanX, vanY, and vanZ, is known to be carried on a 10.8-kb transposon, Tn1546, which was originally described by Arthur and colleagues (2, 3). Several recent studies that compared VanA E. faecium isolates have used restriction and PCR fragment length polymorphism and sequencing of the vanA gene cluster, based on the published sequence of Tn1546, in addition to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) strain typing (1, 13, 16, 18, 19, 24, 26, 28). Researchers in Europe and the United States have found that although the vanA resistance elements of VREF show considerable homology with Tn1546, several alterations have occurred, including insertions (IS1216V [11, 16, 24, 26], IS1251 [14, 16, 18, 26], IS1476 [18], and IS1542 [28]), deletions (in ORF1 and vanZ [26]), and point mutations (vanX, vanY, and vanA [16, 24, 26; L. B. Jensen, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2463–2464, 1998] and ORF1 [26]). The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the epidemiology of VanA E. faecium in Michigan hospitals by using PCR fragment length polymorphism analysis of the vanA gene cluster in 124 VREF strains isolated from 1992 to 1996.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The 124 VanA E. faecium isolates in this study were a subset of a larger group of previously reported VREF strains isolated from separate patients in 13 Michigan hospitals from 1992 to 1996 (23). Ninety-five (76.6%) of these isolates were from the same large community hospital in Southeastern Michigan. There were 26 groups of PFGE strain types, and 6 of these groups contained multiple isolates. All 13 hospitals were represented in one or more of the 3 largest PFGE groups, and the remaining PFGE groups (including 20 unique groups) consisted of isolates from 1 hospital. The number of VanA E. faecium isolates increased steadily over the years of the study, with 1 isolate in 1992, 6 in 1993, 24 in 1994, 34 in 1995, and 59 in 1996. E. faecium 228, which carries the vancomycin resistance element, Tn1546, on plasmid pHKK100 (12), was used as a positive control in PCR experiments. SF12583, a vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium strain, was used as a negative control in PCR experiments.

DNA preparation.

Genomic DNA for PCR was prepared by the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method, which has been described previously (4), and 0.1 μg of genomic DNA was used as a template in PCR experiments.

PCR.

PCR experiments were performed using the PCR Reagent System (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Reactions were carried out on a Perkin-Elmer 480 thermal cycler at a volume of 50 μl with the following components: 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer, 1 μg of each primer, and 0.1 μg of template DNA. PCR was performed for 35 cycles under the following conditions: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. Primers specific for regions of Tn1546 flanking vanRS, vanSH, vanHAX, vanXY, and vanYZ (18) were used to amplify these areas and are shown in Table 1. The PCR products of the 124 study isolates were compared to those of the control strain, EF228, on a 0.7% agarose gel.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used to amplify vanA genes in PCR experimentsa

| Primer | Amplicon | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon size of EF228 (kb) | % of isolates with amplicon the same size as EF228 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vanR1 | vanRS | ATGAGCGATAAAATACITT | 1.8 | 99.2 |

| vanS2 | TTAGGACCTCCTTTTATC | |||

| vanS1 | vanSH | TTGGTTATAAAATTGAAAATT | 2.3 | 20 |

| vanH2 | CTATTCATGCTCCTGTCT | |||

| vanH1 | vanHAX | ATGAATAACATCGGCATTAC | 2.6 | 100 |

| vanX2 | TTATTTAACGGGGAAATC | |||

| vanX1 | vanXY | ATGGAAATAGGATTTACTTT | 1.9 | 100 |

| vanY2 | TTACCTCCTTGAATTAGTAT | |||

| vanY1 | vanYZ | ATGAAGAAGTTGTTTTTTTTA | 1.6 | 99.2 |

| vanZ2 | CTTACACGTAATTTATTC |

RESULTS

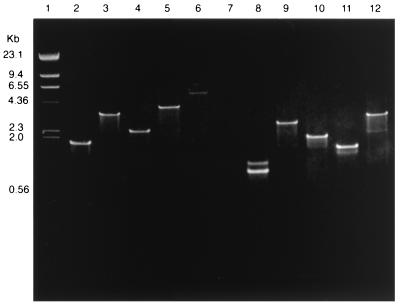

Among the 124 VanA E. faecium isolates in this study, we found five different types of Tn1546 (Table 2), as follows. (i) Twenty-four (19.4%) had a VanA gene cluster indistinguishable from that of EF228. (ii) Ninety-seven (78.2%) had a vanSH amplicon that was approximately 1.4 kb larger than that of EF228 (3.7 versus 2.3 kb). When the individual genes vanS and vanH were amplified, they were both the same size as those of EF228 (1,200 and 800 bp, respectively), indicating an insertion in the intergenic region of vanSH. (iii) One isolate had a vanSH amplicon that was approximately 3.4 kb larger than that of EF228 (5.7 versus 2.3 kb). When vanS and vanH were amplified separately, the vanS amplicon was about 1.3 kb larger (2.5 versus 1.2 kb) and the vanH gene was the same size as that of EF228. The vanRS amplicon of this isolate was also 1.3 kb larger (3.1 versus 1.8 kb) than that of EF228, which is consistent with an insertion in the vanS gene. The remaining 2.1 kb of DNA is in the intergenic region of vanSH. (iv) One isolate was negative for a vanSH amplicon but positive for all the other genes and had individual vanS and vanH amplicons the same sizes as those of EF228. (v) One isolate had a vanYZ amplicon larger than that of EF228 (2.8 versus 1.6 kb). vanY was amplified separately and found to be the same size as vanY in EF228. It is not known whether the insertion is in vanZ or in the intergenic region of vanYZ. Representative amplicons of vanRS, vanSH, vanHAX, vanXY, and vanYZ are shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Tn1546 type by PFGE strain type

| Tn1546 type | PFGE strain type (no. of isolates)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 43) | 4 (n = 23) | 3 (n = 18) | 10 (n = 14) | 11 (n = 4) | 6 (n = 2) | Unique (n = 20) | Total (n = 124) | |

| Like control strain EF228 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 24 |

| vanSH (3.7 kb) | 41 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 17 | 97 |

| vanSH (5.7 kb) and vanRS (3.1 kb) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| No vanSH product | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| vanYZ (2.8 kb) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified vanA genes of EF228 and VanA E. faecium isolates with altered Tn1546. Lanes: 1, HindIII-digested lambda phage DNA; 2, EF228 vanRS (1.8 kb); 3, EF13231 vanRS (3.1 kb); 4, EF228 vanSH (2.3 kb); 5, EF13180 vanSH (3.7 kb); 6, EF13231 vanSH (5.7 kb); 7, EF11456 (vanSH negative); 8, EF11456 vanS and vanH (amplified separately and run in the same lane); 9, EF228 vanHAX (2.6 kb); 10, EF228 vanXY (1.9 kb); 11, EF228 vanYZ (1.6 kb); 12, EF13566 vanYZ (2.8 kb).

The earliest isolate in this study (the only isolate from 1992) was a unique strain and had a vanA resistance element like that of EF228. In 1993, there were six isolates, all from the largest PFGE group (group 1), and each of these had a vanA resistance element with the 1.4-kb insertion between vanS and vanH (Table 2). In the remaining years of the study, however (1994 to 1996), we found both altered vanA elements and those which were indistinguishable from that of EF228. Although isolates with the original Tn1546-like element were a minority or nonexistent in certain PFGE groups, they made up a significant percentage of isolates in the second-largest PFGE group (group 4; 52% [Table 2]) and the third-largest PFGE group (group 3; 44% [Table 2]).

DISCUSSION

In analyzing VRE outbreaks, two important questions must be addressed. First, is the outbreak due to a specific isolate? Second, is the outbreak the result of dissemination of a specific genetic element among heterologous isolates? Our earlier studies indicated that clonal dissemination was responsible for much of the glycopeptide resistance seen in Michigan hospitals (23). Clonal dissemination is considered to be the major mechanism for the spread of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci, with a limited number of strains being responsible for much of the resistance (5, 13, 17, 20, 23). The reason for this is not known, but it could be due to an undetermined virulence factor in these strains. Among isolates with different PFGE types, less is known about epidemiology. Among 124 VanA E. faecium isolates in this study, there were 26 different PFGE strain groups, but only 6 of these groups contained more than 1 isolate, and in fact, 79% of all isolates were contained in only 4 groups (Table 2). In this study, 20 unique strains were found. This gave us the opportunity to determine whether different strains in our study had similar vanA genes. Horizontal transmission of the vanA gene is a possible explanation in cases where epidemiologically related vanA isolates do not share the same PFGE pattern (14, 16, 24, 26, 28; Jensen, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2463–2464, 1998).

The results of this study show that there is not only horizontal transmission of “epidemic” strains of VRE but also transmission of resistance genes from organism to organism. We found that 95% of the isolates in the largest PFGE group (group 1 [Table 2]) had the 1.4-kb insertion in the intergenic region of vanSH, which fits the description of IS1251 originally given by Handwerger and coworkers (14). IS1251 has been found in VREF isolates from humans in the United States (14, 16, 18, 26). It has not been found in humans or animals in Europe. There were two other isolates in this group; one had a vanSH amplicon like that of EF228, and the other did not produce a vanSH amplicon but produced individual amplicons for vanS and vanH. There may have been an insertion in the intergenic region of vanS and vanH so large that an amplicon could not be produced by standard PCR methods. We also found that the second- and third-largest groups (groups 4 and 3, respectively) were divided as to whether they possessed the 1.4-kb insertion between vanS and vanH (Table 2). PFGE group 3 strains were isolated from 1994 to 1996. Four out of five from 1994 had the 1.4-kb insertion; six out of seven isolated in 1995 had a vanSH amplicon like that of EF228; then, in 1996, five out of six isolates had the 1.4-kb insertion. In PFGE group 4, strains were isolated from 1995 to 1996. In 1995, two isolates had a vanSH amplicon like that of EF228 and two possessed the 1.4-kb insertion between vanS and vanH. In 1996, 11 out of 19 isolates (58%) had a vanSH amplicon like that of EF228 and 8 (42%) had the 1.4-kb insertion between vanS and vanH. Therefore, these different Tn1546 types coexist even within PFGE strain types and occur throughout the study period. This 1.4-kb insertion in the intergenic region of vanSH also occurs in 17 of the 20 (85%) PFGE strain types seen only once in the study period.

Of the five types of Tn1546 found in our study isolates (Table 2), both the original Tn1546 and the Tn1546 with an approximately 1.4-kb insertion in the intergenic region of vanSH have been described for VREF from hospitals in the United States (14, 16, 18, 26). Tn1546 was originally found in E. faecium BM4147 (3) and has been found in both human and animal VREF isolates in Europe in its original form (27).

Many studies have been carried out in Europe in an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of vanA dissemination in human and animal strains of VREF and to determine its epidemiology. Vancomycin resistance of E. faecium in the animal population is a particular problem in Europe, where glycopeptides have been used for growth promotion in animals. One study in The Netherlands found that 46% of 305 poultry products examined were contaminated with VanA E. faecium (24). It is a concern that these VREF strains can be passed to humans when the poultry is consumed or that the vanA resistance element will be acquired by E. faecium resident in the human gut. Dutch poultry and human strains of VREF did not share the same PFGE patterns. Although a considerable amount of diversity in PFGE was seen, two epidemic strains were found in poultry products throughout the country. Transposon types were indistinguishable from Tn1546 in human strains, but in poultry, 42% had IS1216V in the intergenic region of vanXY, including two PFGE strains which were epidemic in Dutch poultry (24).

One study in the United Kingdom found 24 types of vanA resistance elements when 106 VREF strains from human and animal sources were evaluated by PCR fragment length polymorphism analysis (28). The investigators found that the Tn1546 genes in humans and animals were usually different and that there was greater diversity of Tn1546 in human VREF. The most common group in human enterococci had a novel insertion sequence, IS1542, between ORF2 and vanR. The investigators later found a blood culture isolate of E. faecium with IS1216V inserted in the vanS gene (11). Previously, IS1216V had been found between vanX and vanY (16, 24, 26). One isolate in this study had an insertion in the vanS gene as well, but it is not known if it is IS1216V (Table 2).

A study of 38 human and animal isolates of VanA E. faecium from Denmark, the United Kingdom, and the United States used PCR fragment length polymorphism, sequencing, and DNA hybridization techniques to analyze the vanA resistance element (16). Thirteen types were found, including human and animal strains with unaltered vanA resistance elements, strains with insertion sequences, different hybridization patterns, and those with a point mutation in the vanX gene. The investigators concluded that there is probably horizontal transfer of the vanA resistance element between humans and animals, since different strains shared the same transposon type. It was later found in a more extensive study that the point mutation in the vanX gene was never found in poultry but was found in all but one pig isolate and 36% of human isolates (Jensen, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2463–2464, 1998). These studies suggested that human VREF shared common transposon types with both pigs and poultry but that pig and poultry VREF did not share a common transposon type. Horizontal transfer of the vanA resistance element could be especially important between animals and humans, since they do not often share the same PFGE strain type of E. faecium.

The results of this study show both clonal dissemination and dissemination of an altered Tn1546 in heterologous VanA E. faecium in Michigan hospitals. The increasing rate of spread of VREF in U.S. hospitals indicates the urgent need for more effective control measures. Measures to control the horizontal transmission of isolates should be considered even when strain types differ by PFGE. The transmission of resistance genes is likely contributed to by selection pressure from the use of vancomycin. Control of VRE will, therefore, require a multifaceted, universal approach that includes patients and environmental reservoirs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant H50/CCH513220-01 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We thank Rosalind Smith for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup F M, Ahrens P, Madsen M, Pallesen L V, Poulsen R L, Westh H. Glycopeptide susceptibility among Danish Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis isolates of animal and human origin and PCR identification of genes within the vanA cluster. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1938–1940. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur M, Courvalin P. Genetics and mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1563–1571. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur M, Molinas C, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, et al., editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. vol. 1, unit 2.4. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischoff W E, Reynolds T M, Hall G O, Wenzel R P, Edmond M B. Molecular epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a large urban hospital over a 5-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3912–3916. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3912-3916.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce J M, Opal S M, Chow J W, Zervos M J, Potter-Bynoe G, Sherman C B, Romulo R L C, Medeiros A A. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium with transferable vanB class vancomycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1148-1153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National nosocomial infection surveillance system report. May 1997. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow J W, Kuritza A, Shlaes D M, Green M, Sahm D F, Zervos M J. Clonal spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium between patients in three hospitals in two states. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1609–1611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1609-1611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark N C, Cooksey R C, Hill B C, Swenson J M, Tenover F C. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coque T M, Arduino R C, Murray B E. High-level resistance to aminoglycosides: comparison of community and nosocomial fecal isolates of enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1048–1051. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darini A L, Palepou M F, James D, Woodford N. Disruption of vanS by IS1216V in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium with VanA glycopeptide resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:995–996. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handwerger S, Pucci M, Kolokathis A. Vancomycin resistance is encoded on a pheromone response plasmid in Enterococcus faecium 228. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:358–360. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handwerger S, Raucher B, Altarac D, et al. Nosocomial outbreak due to Enterococcus faecium highly resistant to vancomycin, penicillin, and gentamicin. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:750–755. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.6.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handwerger S, Skoble J, Discotto L F, Pucci M. Heterogeneity of the vanA gene cluster in clinical isolates of enterococci from the Northeastern United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:362–368. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis W R, Marton W J. Predominant pathogens in hospital infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;29(Suppl. A):19–24. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.suppl_a.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen L B, Ahrens P, Dons L, Jones R N, Hammerum A M, Aarestrup F M. Molecular analysis of Tn1546 in Enterococcus faecium isolated from animals and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:437–442. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.437-442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim W J, Weinstein R A, Hayden M K. The changing molecular epidemiology and establishment of endemicity of vancomycin resistance in enterococci at one hospital over a 6-year period. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:163–171. doi: 10.1086/314564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKinnon M G, Drebot M A, Tyrrell G J. Identification and characterization of IS1476, an insertion sequence-like element that disrupts vanY function in a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1805–1807. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miele A, Bandera M, Goldstein B P. Use of primers selective for vancomycin resistance genes to determine van genotype in enterococci and to study gene organization in VanA isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1772–1778. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pegues D A, Pegues C F, Hibberd P L, Ford D S, Hooper D C. Emergence and dissemination of a highly vancomycin-resistant VanA strain of Enterococcus faecium at a large teaching hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1565–1570. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1565-1570.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sader H S, Tenover M A, Hollis F C, Jones R J, Jones R N. Evaluation and characterization of multiresistant Enterococcus faecium from 12 U.S. medical centers. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2840–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2840-2842.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaberg D R. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infection. Am J Med. 1991;91(Suppl. 3B):72S–75S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thal L A, Donabedian S, Robinson-Dunn B, Chow J W, Dembry L, Clewell D B, Alshab D, Zervos M J. Molecular analysis of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates collected from Michigan hospitals over a 6-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3303–3308. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3303-3308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Braak N, van Belkum A, van Keulen M, Vliegenthart J, Verbraugh H A, Endtz H P. Molecular characterization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from hospitalized patients and poultry products in The Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1927–1932. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1927-1932.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Auwera P, Pensart N, Korten V, Murray B E, Leclercq R. Influence of oral glycopeptides in the fecal flora of human volunteers: selection of highly glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willems R J L, Top J, van den Braak N, van Belkum A, Mevius D J, Hendriks G, van Santen-Verheuvel M, van Embden J D A. Molecular diversity and evolutionary relationships of Tn1546-like elements in enterococci from humans and animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:483–491. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witte W, Klare I. Glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium outside hospitals: a commentary. Microbiol Drug Resist. 1995;3:259–263. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodford N, Adebiyi A-M A, Palepou M-F I, Cookson B D. Diversity of VanA glycopeptide resistance elements in enterococci from humans and nonhuman sources. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:502–508. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zervos M J, Kauffman C A, Therasse P M, Bergman A G, Mikesell T S, Schaberg D R. Nosocomial infection by gentamicin-resistant Streptococcus faecalis: an epidemiologic study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:687–691. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-5-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]