Significance

Exquisite lipid-binding specificity for phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) is hardwired into the structure of the KRAS C-terminal plasma membrane (PM) anchor. This renders KRAS–PM localization and hence biological function potentially vulnerable to perturbations of PM PtdSer content. Here, we show that all components of the recently described lipid transport machinery that maintain PM PtdSer content are indeed required to support KRAS oncogenic function. In this context, we demonstrate that the enzyme, PI4KIIIα, in particular has merit as a druggable target for inhibiting KRAS-dependent tumors. More generally, we provide insight into how PM phospholipids can regulate oncogene signaling and how PM lipid composition may be successfully targeted to exploit tumor vulnerabilities.

Keywords: KRAS, PI4KA, ORP5, ORP8, phosphatidylserine

Abstract

KRAS is mutated in 90% of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs). To function, KRAS must localize to the plasma membrane (PM) via a C-terminal membrane anchor that specifically engages phosphatidylserine (PtdSer). This anchor-binding specificity renders KRAS–PM localization and signaling capacity critically dependent on PM PtdSer content. We now show that the PtdSer lipid transport proteins, ORP5 and ORP8, which are essential for maintaining PM PtdSer levels and hence KRAS PM localization, are required for KRAS oncogenesis. Knockdown of either protein, separately or simultaneously, abrogated growth of KRAS-mutant but not KRAS–wild-type pancreatic cancer cell xenografts. ORP5 or ORP8 knockout also abrogated tumor growth in an immune-competent orthotopic pancreatic cancer mouse model. Analysis of human datasets revealed that all components of this PtdSer transport mechanism, including the PM-localized EFR3A-PI4KIIIα complex that generates phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P), and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–localized SAC1 phosphatase that hydrolyzes counter transported PI4P, are significantly up-regulated in pancreatic tumors compared to normal tissue. Taken together, these results support targeting PI4KIIIα in KRAS-mutant cancers to deplete the PM-to-ER PI4P gradient, reducing PM PtdSer content. We therefore repurposed the US Food and Drug Administration–approved hepatitis C antiviral agent, simeprevir, as a PI4KIIIα inhibitor In a PDAC setting. Simeprevir potently mislocalized KRAS from the PM, reduced the clonogenic potential of pancreatic cancer cell lines in vitro, and abrogated the growth of KRAS-dependent tumors in vivo with enhanced efficacy when combined with MAPK and PI3K inhibitors. We conclude that the cellular ER-to-PM PtdSer transport mechanism is essential for KRAS PM localization and oncogenesis and is accessible to therapeutic intervention.

RAS proteins are small GTPases that switch between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states, regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. RAS is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors that promote GDP–GTP exchange, thereby activating RAS, and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which stimulate intrinsic RAS GTPase activity to return it to its inactive state. Approximately 20% of human cancers express oncogenic RAS with mutations at residues 12, 13, or 61 (1), which prevent RASGAPs from stimulating GTP hydrolysis, rendering RAS constitutively active. The RAS isoforms, HRAS, NRAS, KRAS4A, and KRAS4B (hereafter referred to as KRAS), have near-identical G-domains, which are implicated in guanine nucleotide binding and effector interaction. However, they have different C termini and membrane anchors, which contribute to their differential signaling outputs (2). KRAS is the most-frequently mutated isoform in cancer and hence represents the major clinical concern, especially in pancreatic, colon, and non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) in which mutant KRAS is expressed in ∼90%, ∼50%, and ∼25% of cases, respectively (3).

RAS proteins must localize to the plasma membrane (PM) and organize into nanoclusters for biological activity (4–8), whereby RAS.GTP recruits its effectors to PM nanoclusters, leading to downstream pathway activation. KRAS interacts with the PM via its C-terminal membrane anchor that comprises a farnesyl-cysteine-methyl-ester and a polybasic domain (PBD) of six contiguous lysines (9–11). Together, the KRAS PBD sequence and prenyl group define a combinatorial code for lipid binding, resulting in a membrane anchor that specifically interacts with asymmetric species of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) that contain one saturated and one desaturated acyl chain (8, 12–14). Since PtdSer binding specificity is hardwired into its anchor structure, KRAS–PM interactions are PtdSer dependent. KRAS that partitions into the cytosol following endocytosis is captured by PDEδ, which, upon interacting with ARL2, is released to the recycling endosome (RE) for forward transport back to the PM (15). Capture of KRAS by the RE is again PtdSer dependent; therefore, abrogating PtdSer delivery to the PM will reduce PM and RE PtdSer content, abrogating both KRAS PM binding and KRAS recycling back to the PM. In sum, KRAS–PM localization, nanoclustering, and signaling capacity are all exquisitely dependent on PM PtdSer levels.

Previous attempts at preventing KRAS–PM localization to inhibit its function include the development of farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs), which inhibit the first posttranslational processing step that generates the KRAS membrane anchor. FTIs were clinically unsuccessful since KRAS can alternatively be geranylgeranylated by geranylgeranyl transferase1 when cells are treated with FTIs, allowing for continued PM localization (2, 16, 17). We recently leveraged the dependence of KRAS on PM PtdSer to inhibit KRAS signaling by targeting the cellular machinery that actively maintains PM PtdSer levels (18). Genetic knockdown (KD) of ORP5 or ORP8, two lipid transporters that function at endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–PM membrane contact sites to transport PtdSer to the PM (Fig. 1), mislocalized KRAS from the PM and reduced nanoclustering of any remaining KRAS. Consequently, ORP5/8 KD decreased proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of multiple KRAS-dependent pancreatic cancer cell lines. In this study, we examine the effects of ORP5/8 genetic KD and knockout (KO) on tumor growth in vivo and provide compelling evidence that these proteins are essential for tumor maintenance in KRAS-dependent pancreatic cancer. ORP5/8 function by exchanging phosphoinositide-4-phosphate (PI4P) synthesized on the PM by PI4KIIIα for PtdSer synthesized in the ER (19, 20). We demonstrate both in vitro and in vivo that PI4KIIIα inhibitors can potently inhibit oncogenic KRAS function. One such inhibitor is simeprevir, a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved antiviral agent used for the treatment of hepatitis C, that may have potential for repurposing as a therapeutic for mutant KRAS-driven cancers.

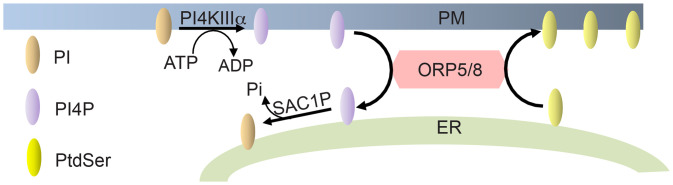

Fig. 1.

ORP5 and ORP8 transport PtdSer to the PM. ORP5 and ORP8 exchange ER PtdSer with PM PI4P. This is driven by a PI4P concentration gradient whereby PM PI4P levels are kept high by PI4KIIIα and low at the ER by SAC1P, which hydrolyzes PI4P. ORP, oxysterol-binding protein-related protein; PI4KIIIα, class III PI4 kinase alpha; and SAC1P, SAC1-like phosphatidylinositide phosphatase.

Results

ORP5 or ORP8 KD Inhibits KRAS-Mutant Tumor Growth in a Xenograft Mouse Model.

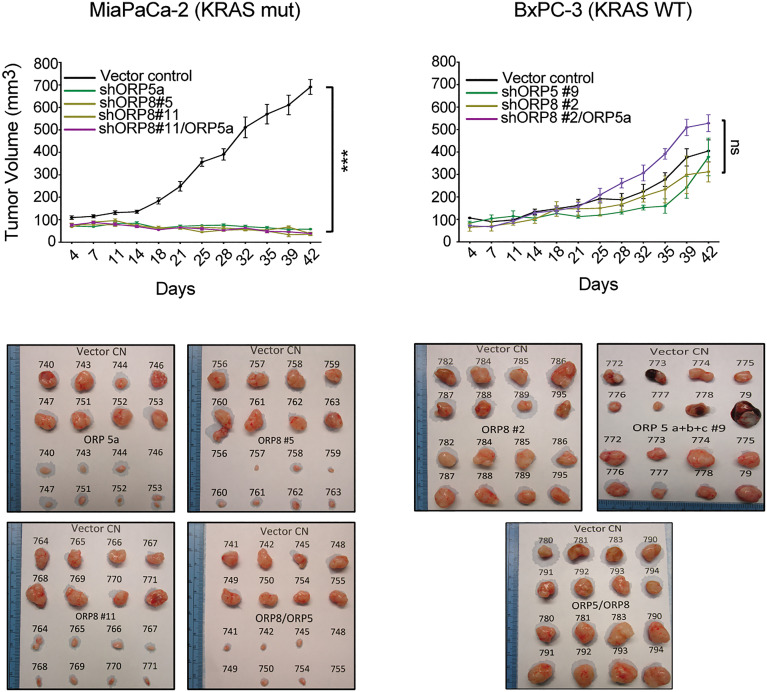

We performed shRNA (short hairpin RNA) KD of ORP5 and ORP8 alone or in combination in a panel of KRAS wild-type (WT) (BxPC-3) and mutant (MiaPaCa-2, MOH, and PANC-1) pancreatic cancer cells followed by puromycin selection to obtain multiple stable monoclonal cell lines as previously described (18). To establish the effect of ORP5 and ORP8 KD on tumor initiation and growth in vivo, parental (containing an empty plasmid), single clonal ORP5, ORP8, or double ORP5/ORP8 KD MiaPaCa-2 or BxPC-3 cells were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks, respectively, of nu/nu-immunosuppressed mice, allowing each mouse to act as its own control. Tumors were measured twice a week for 6 wk. KD of either ORP protein consistently and significantly impaired tumor growth of MiaPaCa-2 cells, while having no effect on BxPC3 cells (Fig. 2). Single KD of ORP5 or OPR8 had as strong an effect as double KD in abrogating tumor growth, with no difference between which ORP protein was knocked down. We conclude that ORP5 and ORP8 are both essential for KRAS-mutant tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 2.

ORP5 and/or ORP8 KD inhibits tumor growth of KRAS-mutant PDAC in vivo. Monoclonal shORP5, shORP8, and shORP5/8 KD MiaPaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cells were injected subcutaneously in the left flanks of nu/nu-immunosuppressed mice. Monoclonal empty vector controls (CN) were injected in the right flanks to serve as internal controls. Tumors were harvested after 6 to 8 wk (one-way ANOVA, ***P < 0.005; n = 8 per group). ns, nonsignificant.

CRISPR/Cas9 KO of ORP5 or ORP8 Decreases Anchorage-Independent Growth In Vitro and Inhibits Tumor Growth in an Immune-Competent Syngeneic Mouse Model.

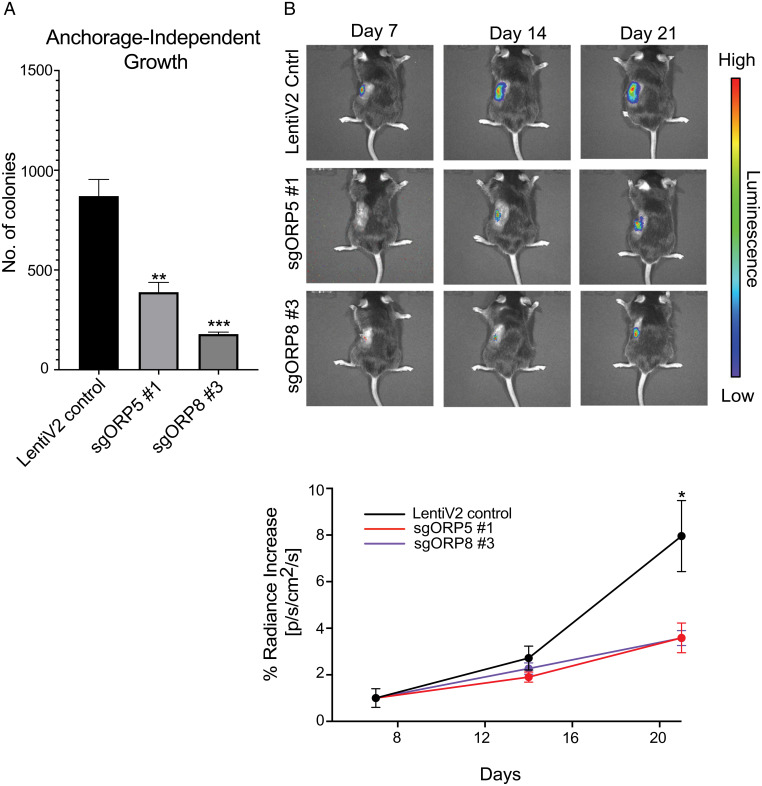

To more closely recapitulate in vivo pancreatic cancer, we assessed the importance of ORP5 and ORP8 in orthotopic tumor initiation and maintenance in an immune-competent syngeneic mouse model. To that end, we used a KPC (Pdx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D/+, and LSL-Trp53R172H/+) mouse pancreatic cancer cell line (21). First, we engineered these cells to constitutively express luciferase. Single cells were expanded to produce monoclonal lines and the line with the strongest luciferase signal was chosen. We next used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate monoclonal ORP5 and OPR8 KO cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Cells containing an empty plasmid backbone were used as controls. As shown in Fig. 3A, knockout of ORP5 or ORP8 significantly impaired the anchorage-independent growth of KPC cells in soft agar, with ORP8 KO cells exhibiting a more-severe phenotype. KPC cells were then orthotopically injected into the pancreas of immune-competent C57/BL6 mice, followed by weekly IVIS (in vivo imaging system) imaging to track tumor progression. Concordant with the in vitro results, KO of either ORP protein markedly inhibited tumor growth in this setting, with ORP8 KO having a more profound effect (Fig. 3B). Thus, as in the xenograft model, ORP5 and ORP8 are essential for KRAS oncogenesis in an immune-competent mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs).

Fig. 3.

ORP5 or ORP8 KO reduces PDAC tumor growth in an immune-competent syngeneic mouse model. (A) Monoclonal empty vector, sgORP5, or sgORP8 KO KPC cells were seeded in soft agar with a base layer of 1% agar–media mixture and a top layer of a 0.6% agar-cell suspension mix in six-well plates. After 2 to 3 wk, colonies were stained with 0.01% crystal violet and counted using ImageJ. Significant differences were evaluated using Student’s t tests (±SEM, n = 3) (**P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001). (B) The same cells in A were injected orthotopically into the pancreases of C57/BL6 mice which were imaged using an in vivo imaging system two to three times per week for 3 wk. Student’s t test was used at each time point (n = 8 per group, *P < 0.05).

All Components of the PtdSer Transport Machinery Are Up-Regulated in Pancreatic Cancer.

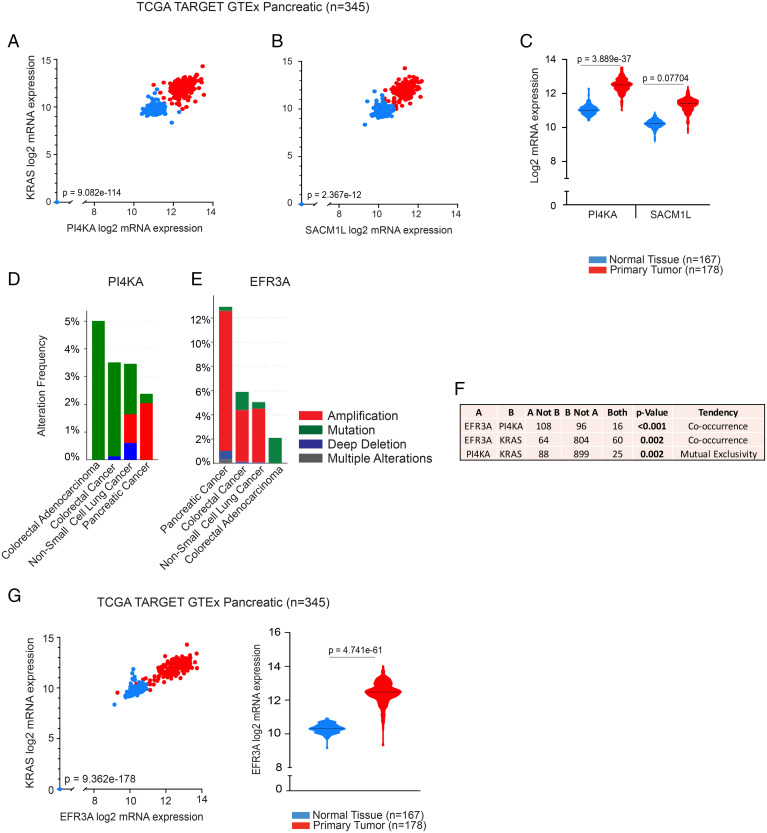

We recently showed that high expression levels of OSBPL5 or OSBPL8 (encoding ORP5 and ORP8, respectively) in PDAC and lung cancer are associated with poor overall survival in patients. Moreover, OSBPL5 expression in 33 different cancer types was significantly increased in KRAS-mutant compared to KRAS-WT tumors (18). Here, we focus on PDAC, notorious for a low survival rate and in which ∼90% of cases are driven by oncogenic KRAS. ORP5 and ORP8 comprise the core of the PtdSer/PI4P exchange mechanism; however, the driving force behind this is a concentration gradient of PI4P kept high at the PM by PI4KIIIα and low in the ER by SAC1 phosphatase (SAC1P) (encoded by PI4KA and SACM1L, respectively). PI4KIIIα-generated PI4P is transported to the ER by ORP5/8 in exchange for PtdSer where it is hydrolyzed to PI by SAC1P. To determine whether PI4KA and SACM1L correlate with adverse outcomes in PDAC, we analyzed pancreatic RNA-sequencing data from the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) TARGET GTEx study, which encompasses expression profiles of TCGA solid-tumor samples and GTEx samples derived from normal tissues of healthy individuals. The analysis showed significant and positive correlation between PI4KA and KRAS (Fig. 4A) and between SACM1L and KRAS (Fig. 4B) messenger RNA (mRNA) levels in both normal and tumor pancreatic tissue, with significant up-regulation of PI4KA and SACM1L expression in tumor tissue (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of PI4KA, SACM1L, and EFR3A expression levels in PDAC. Scatter plots indicating positive correlation of mRNA expression levels of KRAS with PI4KA (Pearson’s rho = 0.8817) (A) and SACM1L (Pearson’s rho = 0.3657) (B), in normal and primary tumor human pancreatic tissue samples (TCGA TARGET GTEx, n = 345). Violin plots indicating medians of PI4KA and SAC1ML (C) mRNA expression levels in the same cohort. Bar graphs showing the extent and nature of genetic alterations occurring in PI4KA (D) and EFR3A (E) in pancreatic, lung, and CRC cohorts and how their genetic states relate to one another (F). Bar graphs and statistical analyses were generated in cBioPortal (n = 3176). (G) Scatter plot indicating positive correlation of mRNA expression levels of KRAS with EFR3A (Pearson's rho = 0.9518), and a violin plot indicating median mRNA expression level of EFR3A in the same cohort as in A. Statistical significance was analyzed with Welch’s t test for violin plots generated using the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Xena Browser.

PI4KIIIα is recruited to the PM by a protein adaptor complex that includes EFR3A, a protein that anchors to the PM via its palmitoylated N terminus (22, 23). To evaluate the possible interplay between PI4KIIIα and EFR3A in KRAS cancers, we analyzed genetic alterations and their frequency of occurrence in pancreatic cancer (PDAC), NSCLC, and colorectal cancer (CRC) cohorts in cBioPortal. The vast majority of PI4KA genetic alterations were “mutations of unknown significance” in CRC, while NSCLC tumor samples harbored these and some deep deletions (Fig. 4D). In PDAC, however, the major alteration was gene amplification although it only occurred in ∼2% of PDAC. We therefore conclude that the increased expression of PI4KA mRNA observed in PDAC is due to up-regulated gene transcription rather than gene amplification. EFR3A is frequently amplified in PDAC (∼12%) but less commonly in NSCLC and CRC (∼5%) (Fig. 4E). Genetic alterations of PI4KA significantly co-occur with those of EFR3A but are mutually exclusive with those of KRAS (Fig. 4F). Consistent with gene amplification, EFR3A mRNA expression was significantly increased in pancreatic tumors compared to normal tissue and significantly and positively correlated with KRAS mRNA expression levels (Fig. 4G). Taken together, these data further link all components of the PtdSer/PI4P PM–ER exchange mechanism to oncogenic KRAS function.

Simeprevir Mislocalizes PtdSer and KRAS from the PM.

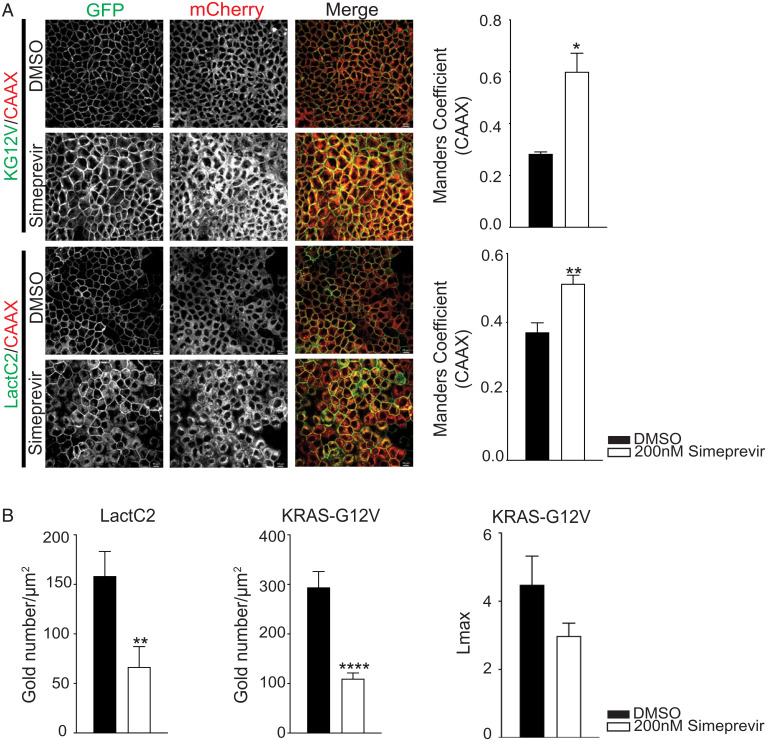

The elevated PI4KA expression in KRAS-mutant tumors highlights a potential druggable vulnerability. Moreover, we showed previously that a selective PI4KIIIα inhibitor tool compound, C7, potently mislocalized PtdSer and KRAS in a dose-dependent manner, with significant mislocalization seen at 30 µM (18). Here, we examined another PI4KIIIα inhibitor, simeprevir, an FDA-approved antiviral agent used for the treatment of hepatitis C. We first examined the efficacy of this compound in KRAS and PtdSer mislocalization assays. Madin–Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells stably expressing GFP-tagged oncogenic KRASG12V (GFP-KRASG12V) or a GFP-tagged PtdSer probe (GFP-LactC2) together with mCherry-CAAX, a general endomembrane marker, were treated with simeprevir for 72 h and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Manders coefficient was used to quantify the extent of overlap between GFP and mCherry signals to evaluate the extent of colocalization between KRASG12V or LactC2 with endomembranes, in which higher Manders coefficient values correlate with greater mislocalization of KRASG12V or LactC2 from the PM. Simeprevir at a concentration of 200 nM, which is close to the previously calculated half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for PI4KIIIα kinase activity (24), was sufficient to significantly mislocalize both LactC2 and KRASG12V from the PM compared to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated controls (Fig. 5A). To more accurately quantify the amount of PM-localized GFP-KRASG12V and GFP-LactC2 in these cells, intact basal PM sheets were prepared 48 h after treatment with 200 nM of simeprevir, labeled with gold-conjugated anti-GFP antibodies, and analyzed by electron microscopy (EM) (25). Treatment with simeprevir caused significant loss of both KRASG12V and LactC2 from the PM, as evidenced by the decrease in anti-GFP immunogold labeling. Spatial-mapping analysis further showed that the extent of clustering (Lmax) of any KRASG12V remaining on the PM was strongly decreased in simeprevir-treated cells (Fig. 5B). Since KRAS is the only RAS isoform that requires PtdSer for PM localization, only the KRAS isoform should be sensitive to PI4KIIIα inhibition. To formally verify this prediction, we next treated MDCK cells stably expressing HRASG12V, NRASG12V, or KRASG12V with C7 or simeprevir. Both PI4KIIIα pharmacologic inhibitors significantly abrogated KRASG12V PM localization but had no effect on HRASG12V PM localization and modestly enhanced NRASG12V PM localization (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Taken together, these results show that PI4KIIIα inhibitors selectively inhibit KRAS PM mislocalization, with simeprevir exhibiting greater potency than C7.

Fig. 5.

Simeprevir mislocalizes KRAS and PtdSer from PM in the nanomolar range. (A) MDCK cells expressing GFP-KG12V and mCherry-CAAX or GFP-LactC2 and mCherry-CAAX were treated with DMSO or simeprevir for 72 h at varying concentrations then imaged with confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. The extent of KRAS and LactC2 mislocalization was quantified using Manders coefficient (±SEM, n ≥ 5). (Scale bar, 20 μm.) (B) Basal PM sheets from cells in A treated with 200 nM simeprevir for 48 h were prepared and labeled with 4.5 nm gold-conjugated anti-GFP antibodies and visualized by EM. The amount of PM KRASG12V and LactC2 was measured as gold particle labeling per micrometer2. Significant differences were quantified using Student’s t tests. KRAS clustering was quantified by univariate spatial analysis, summarized as Lmax values, and significant differences were assessed using bootstrap tests (±SEM, n ≥ 17) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.001). KG12V, KRASG12V; LactC2, PtdSer probe.

PI4KIIIα Inhibition Reduces Cancer Cell Tumorigenicity In Vitro.

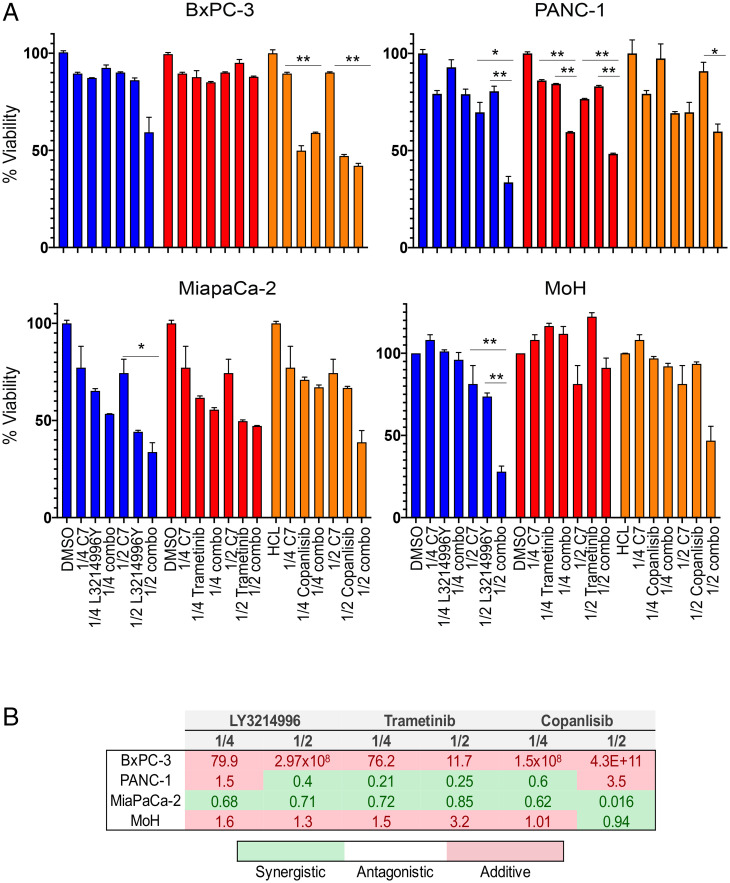

We next evaluated the capacity of C7 and simeprevir as inhibitors of PtdSer transport to the PM to pharmacologically recapitulate the effects of ORP5/8 KD on cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. We showed previously that C7 selectively inhibits the growth of KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer cells (18). However, since up-regulation of KRAS downstream effectors is a common occurrence upon KRAS inhibition, we examined whether increased efficacy could be achieved in combination with inhibitors of MEK (trametinib), ERK (LY3214996), and PI3K (copanlisib) on KRAS WT (BxPC-3) and mutant (MiaPaCa-2, G12C; MOH, G12R; and PANC-1, G12D) cell lines (Fig. 6A). Cells were treated with DMSO control, C7 alone, and each of the inhibitors alone and in combination with C7 at 0.5× and 0.25× the calculated IC50 doses of each inhibitor (SI Appendix, Table S1). The number of viable cells normalized to control after 72 h was the experimental end point (Fig. 6A). The degree of synergy was determined by calculating the combination index (CI) using the Chou–Talalay method, whereby the effect is additive, synergistic, or antagonistic if the CI is more than, less than, or equals 1, respectively (26). As seen in Fig. 6B, combining C7 treatment with each of the inhibitors had additive or synergistic effects in all KRAS-mutant cell lines, but not in the KRAS-WT BxPC-3 cell line.

Fig. 6.

C7 inhibits proliferation of KRAS-mutant cells with increased efficacy when combined with MAPK or PI3K inhibitors. (A) BxPC-3, MiaPaCa-2, PANC-1, and MOH cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, fresh growth medium was added supplemented with 1% DMSO and 1/4 or 1/2 of the calculated IC50 of each indicated drug as single or combination treatment. Cells were counted 72 h later (mean ± SEM, n = 3) (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). (B) The CI of each combination treatment was calculated using the Chou–Talalay method (CI = 1, antagonistic; CI < 1, synergistic; and CI > 1, additive).

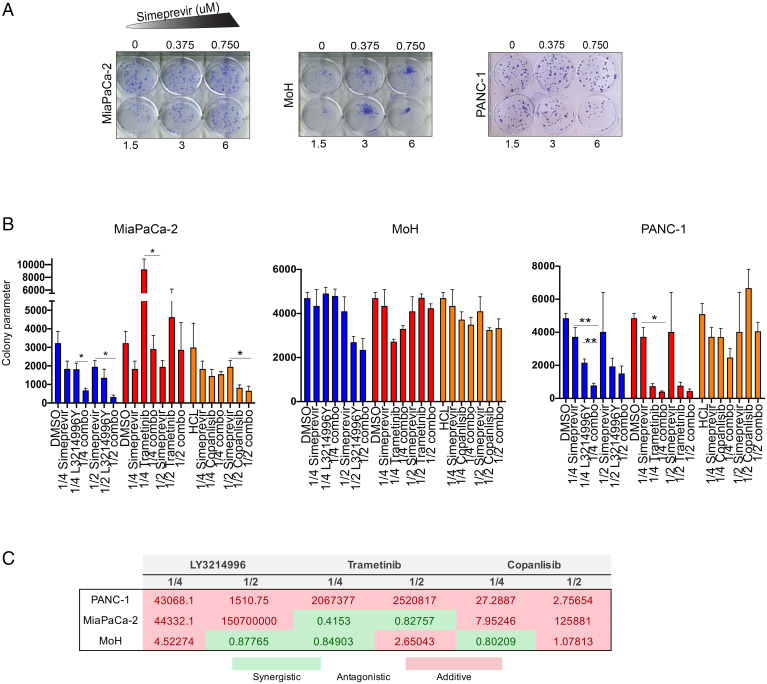

Since simeprevir treatment alone did not significantly decrease proliferation of the above-mentioned cell lines, we evaluated its effects in clonogenic assays, which introduce more stringent growth requirements, uncovering vulnerabilities undetected by simple two-dimensional proliferation on plastic. This is similar to previous observations whereby ORP5 and ORP8 KD elicited a much-stronger phenotype in soft-agar assays than in proliferation assays (18). Cells were seeded at low densities and treated with increasing doses of simeprevir for 2 wk, followed by crystal violet staining and colony quantification. Simeprevir reduced the colony formation potential of KRAS-mutant cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A), with increased efficacy when combined with trametinib, LY3214996, or copanlisib (Fig. 7 B and C). We conclude that KRAS-mutant cells are sensitive to combination treatments of simeprevir or C7 with MAPK or PI3K inhibitors and that such combination treatments generally produce more potent responses than monotherapy.

Fig. 7.

Simeprevir decreases anchorage-independent growth and clonogenic capability of KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer cells. (A) PANC-1, MiaPaCa-2, and MOH cells were seeded at low densities in a six-well plate, and fresh growth medium supplemented with 1% DMSO or increasing simeprevir concentrations were added 24 h later. After 2 wk, cells were fixed with 0.01% crystal violet. (B) The same cells were seeded as in A. After 48 h, fresh growth medium supplemented with 1% DMSO and 1/4 or 1/2 of the calculated IC50 of each indicated drug as single or combination treatment was added. After 2 wk, cells were stained with 0.01% crystal violet and counted using ImageJ. The colony counter plugin (55) measured the percentage area (area%) of each well covered by colonies. Data were plotted as (area%)*(number of colonies) to obtain “colony parameter” (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Significant differences were evaluated using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). (C) The CI of each combination treatment in B was calculated using the Chou–Talalay method (CI = 1, antagonistic; CI < 1, synergistic; and CI > 1, additive).

Simeprevir Inhibits KRAS Signaling and Tumor Growth In Vivo and Has Synergistic Effects with MEK and PI3K Inhibitors.

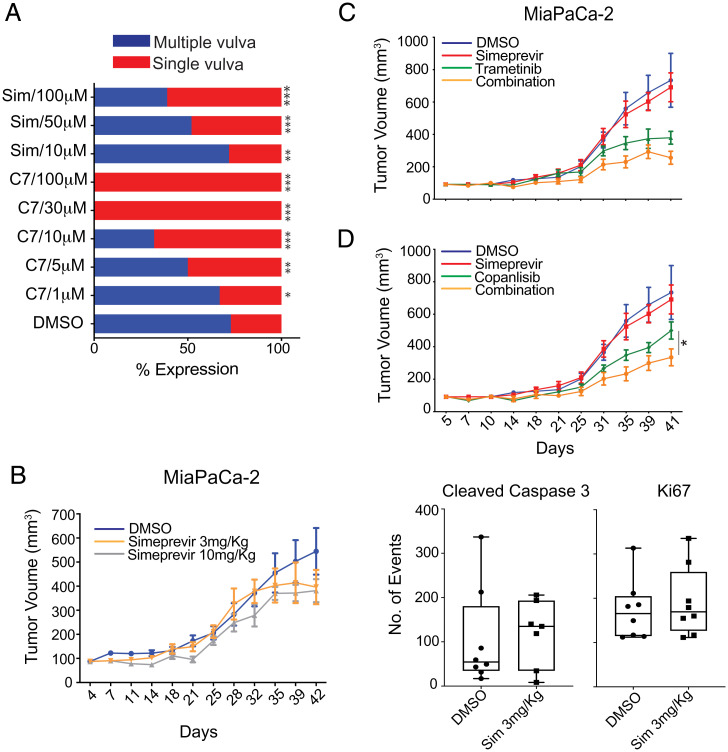

We evaluated the efficacy of simeprevir and C7 as inhibitors of KRAS signaling in vivo in a Caenorhabditis elegans model expressing a mutationally activated G13D let-60 allele (n1046). Let-60 is the ortholog of KRAS4B and the only RAS gene in this organism. Mutant let-60 signaling results in the formation of multiple vulvas (Muv phenotype), which reverts to a single-vulva WT phenotype upon successful inhibition of let-60 signal output. C7 and simeprevir both suppressed the Muv phenotype in let-60 (n1046) worms in a dose-dependent manner with C7 being more potent (Fig. 8A). No changes in development or viability were observed in the presence of either drug compared to DMSO-treated worms, suggesting that C7 and simeprevir do not show any overt toxicity to the organism under these experimental conditions.

Fig. 8.

PI4KIIIα inhibitors suppress KRAS signaling in vivo and attenuate PDAC tumor growth. (A) A total of 2 mL of drug or vehicle control and ∼100 L1 larvae (C. elegans strain MT2124) were added per well in a 12-well plate and tested in duplicate. The presence of the multivulva phenotype was scored using DIC/Nomarski (differential interference contrast/Nomarski) microscopy (n = 125 worms per treatment) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001). (B) Mice subcutaneously injected with MiaPaCa-2 cells were treated with 3 or 10 mg/kg of simeprevir for 6 wk. Quantification of immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of harvested tumors show decreased cleaved caspase-3 staining. (C and D) Mice were inoculated as in B and treated with DMSO, single, or combination treatment as indicated for 6 to 8 wk. Student’s t test was used to determine significance between tumor sizes of different groups at each time point (*P < 0.05, n = 8 per group).

To further evaluate the in vivo efficacy of simeprevir, nu/nu-immunosuppressed mice were subcutaneously injected with MiaPaCa-2 cells and treated five times per week with DMSO and 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg of simeprevir for 6 wk. We observed a dose-dependent response in inhibiting tumor growth (Fig. 8B); however, 10 mg/kgs proved to be too toxic. Though not statistically significant (P = 0.08), we observed a ∼28% reduction in tumor size in the 3 mg/kg group compared to DMSO-treated control group by day 42. Immunohistochemistry staining of sectioned tumor samples with anti-cleaved caspase-3 showed a significant increase in treated tumors, indicative of increased apoptosis (Fig. 8B).

Since combining simeprevir with MAPK and PI3K inhibitors yielded stronger inhibitory effects in vitro, we evaluated these combination treatments in vivo. Mice were treated with DMSO control, simeprevir, trametinib, copanlisib, or a combination of simeprevir with either drug. Combination treatments produced more prominent tumor growth inhibition than single-agent treatment (Fig. 8 C and D), with a ∼33% reduction in tumor size. In sum, the dose-dependent response to simeprevir observed in vitro was recapitulated in vivo in worms and xenograft mouse models, as was the increased potency of combination treatments seen in vitro.

Discussion

We show here that maintenance of PM PtdSer levels is absolutely required for KRAS–PM localization and hence oncogenic function. Therefore, disrupting any component of the ORP5/8 ER-to-PM PtdSer transport process abrogates KRAS function. First, KD of ORP5 or ORP8 separately or in combination completely inhibited tumor growth of KRAS-mutant but not KRAS-WT cells in xenograft mouse models. Importantly, clonal variation and differences between single versus double KD were not seen here, indicating nonredundant functions of ORP5 and ORP8 that are in turn both required for KRAS function. Second, identical results were observed in an immune-competent, syngeneic orthotopic mouse model of pancreatic cancer, in which again KO of ORP5 or ORP8 abrogated tumor growth. Third, we found that all components of the PtdSer/PI4P exchange mechanism are transcriptionally up-regulated in human pancreatic cancer and their expression levels positively correlate with KRAS expression. This increased expression extends to EFR3A, which is an essential component of the molecular complex that anchors PI4KIIIα to the PM. We speculate that these results may reflect selection for cell mechanisms that increase KRAS signal output as part of oncogenic transformation by enhancing KRAS–PM localization. For example, PI4KIIIα overexpression has been reported to increase ORP5/8 localization to PM–ER membrane contact sites, while PI4KIIIα inhibition decreases ORP5– and ORP8–PM localization (19) and causes dissociation of these sites (27). Concordantly, EFR3A KO significantly depleted PM PtdSer content and hence KRAS–PM localization and nanoclustering (28). Fourth, we show that PtdSer/PI4P exchange mechanism is pharmacologically accessible and highly selective for KRAS–PM localization over HRAS or NRAS–PM localization.

The PI4KIIIα inhibitors, C7 and simeprevir, both of which significantly mislocalize PtdSer and KRAS from the PM, reduce the fitness of KRAS-mutant cell lines in a dose-dependent manner in vitro. In vivo, both compounds dose-dependently inhibited signaling of the KRAS ortholog let-60 in C. elegans without any observable toxicity and importantly showed efficacy against KRAS-mutant pancreatic xenografts in nude mice. These results are echoed by studies showing that KO of either EFR3 isoform or PI4KA decreased cell proliferation, colony formation, and anchorage-independent growth in a panel of pancreatic cancer cell lines (28). It is worth noting that PI4KIIIα has been independently identified as a viable drug target in pancreatic cancer because of a role in promoting invasion and metastasis and gemcitabine resistance (29, 30). Several other lines of evidence indicate that inhibiting PI4KIIIα has the capacity to inhibit the MAPK and PI3K pathways, which is an attractive trait for a drug candidate since 93% of PIK3CA mutations in PDAC co-occur with KRAS mutations (31–36). PI4KIIIα activity contributes to the maintenance of both PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) and PI(4,5,3)P3 (PIP3) PM levels; C7 treatment significantly mislocalizes PM KRAS and PtdSer at concentrations that decrease levels of these phosphoinositides (18, 37), and simeprevir treatment decreases PIP3 levels in breast cancer cell lines leading to decreased pAKT (38).

PI4KIIIα inhibitors also synergized, or had additive effects, with classical MAPK and PI3K inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. MOH cells were consistently the most sensitive to MEK, ERK, or PI3K inhibition and to all perturbations of PtdSer transport, including ORP5 or ORP8 KD (18). This may relate to the KRAS-G12R mutation that prevents binding to the PI3K p110α subunit and hence activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, rendering KRAS-G12R mutant cells more vulnerable to MAPK inhibitors than KRASG12V or KRASG12D-mutant cells (39). Thus, whereas most KRAS mutant cell lines may compensate for the loss of MAPK pathway activation by increasing KRAS-dependent activation of PI3K/AKT, KRASG12R mutant cells cannot. Collectively, these observations may justify the use of a KRASG12R mutation as a marker for enhanced sensitivity toward PI4KIIIα inhibition.

The viability of PI4KIIIα inhibition in the context of hepatitis C treatment has been questioned due to toxicity concerns (27), in large part because of results in transgenic mice. Homozygous PI4KA conditional KO mice showed distended abdomens and gastrointestinal abnormalities and had to be euthanized within a week of induction, whereas heterozygous PI4KA conditional KO mice were healthy (40). The difference seen between the two conditions may be considered representative of high versus low doses of PI4KIIIα inhibitors. Subsequently, however, simeprevir was FDA approved for the treatment of hepatitis C alone and in combination with other antiviral agents. We saw no negative effects on viability in C. elegans treated with C7 or simeprevir or in mice treated with simeprevir. Similarly, in other studies examining the utility of simeprevir to enhance the radiosensitivity of diverse cancer cell lines in vitro and in immune-competent and nude mouse models of breast and brain cancer, no overt animal toxicity was observed (38).

It is worth noting that simeprevir has a therapeutic window on infected cells, because the hepatitis C virus highly up-regulates PI4KIIIα activity (41). Following this rationale, we hypothesize that simeprevir will more potently target mutant-KRAS–expressing cancer cells as they also significantly up-regulate PI4KA expression. The drug repurposing resource DepMap (https://depmap.org/repurposing), which surveyed the growth-inhibitory activity of 4,518 drugs in 578 human cancer cell lines, provides additional evidence that simeprevir likely has increased potency in KRAS-driven tumors (42). Analyzing this repository revealed that 21 of 34 pancreatic, 18 of 34 colorectal, and 52 of 88 NSCLC cancer lines, derived from tumors with a high prevalence of KRAS mutation, were deemed sensitive to simeprevir. Moreover, a recent prospective study that evaluated the incidence of nonhepatic cancers in patients with chronic hepatitis C found that triple-therapy treatments, which included simeprevir, decreased the risk of developing PDAC and NSCLC by 45% and 25%, respectively, but had no significant effect on other cancers (43). Taken together, these results support the use of PI4KIIIα inhibitors and repurposing simeprevir for KRAS-mutant cancers.

Mechanistically, whether PI4P and PIP2 are equally important for PtdSer PM transport is not fully resolved, but it is clear that elevated PIP2 levels increase PtdSer exchange either by increasing ORP8 PM recruitment, by acting as a substrate for OPR8-mediated PtdSer exchange, or a combination of both mechanisms (44–48). Targeting PI4KIIIα, however, will functionally inhibit ORP5 and ORP8 by depleting both PM PI4P and PIP2. In this context, an analysis of genes associated with PIP2 metabolism showed that all kinase and phosphatase pairs that maintain PM PIP2 levels are up-regulated in tumor tissue compared to normal pancreatic tissue (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) but not to the same magnitude as PI4KA and SACM1L (Fig. 4); PTEN expression was, however, substantially elevated, despite its tumor suppressor status. PIKFYVE (which generates PI5P from PI) had the least expression level difference between tumor and normal tissue (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), possibly signifying that PI4P and PIP2 generated from PI4P are the most important PI species on the PM for KRAS-mutant PDAC. Further interrogation of all PDAC cohorts deposited in cBioPortal (n = 776) revealed that only 0.9% of profiled samples had a PTEN alteration, most of which were deep deletions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C). One consequence of increased PTEN expression suggested by this combined analysis would be to further elevate PM PIP2 levels and enhance ORP8-mediated PtdSer transport to the PM, which would increase KRAS nanoclustering and MAPK activation at the expense of PI3K/AKT activation. Other data are concordant with this broader inference that in the context of KRAS oncogenesis, MAPK is more important than PI3K/AKT signaling: KRAS-WT pancreatic PDACs harbor BRAF mutations rather than PI3K/AKT pathway mutations (49–51), whereas PIK3CA and KRAS mutations co-occur, indicating that KRAS is not a potent activator of the PI3K/AKT pathway (52), and RASless MEFs regain oncogenic growth upon ectopic expression of activated RAF or MEK but not PI3K/AKT (53).

In conclusion, we demonstrate the critical importance of the PtdSer/PI4P exchange mechanism for KRAS–PM localization and signaling capacity in cell lines, worms, and mice. Together, our data provide an important proof of principle that all components of the PtdSer/PI4P ER–PM transport machinery are putative targets for anti-KRAS drug development. We speculate that inhibiting RAS localization and nanoclustering by dysregulating PM lipid composition could be extrapolated to other RAS isoforms that have anchors that engage different sets of PM lipids. More generally, we provide some insight into how phospholipids can regulate oncogene signaling and how they and their respective regulators can be targeted to exploit tumor vulnerabilities.

Materials and Methods

ORP5/8 KO cell lines were established via lentiviral transfection and validated by Sanger sequencing. Immuno-EM imaging and data analysis was performed as previously described (54). A detailed description of materials and methods for cloning, cell culture, microscopy, worm and mouse experiments, and data analysis can be found in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Grant RP200047 to J.F.H. W.E.K. is supported by the Andrew Sowell–Wade Huggins Fellowship/Professorship in Cancer Research and the Dr. John J. Kopchick Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2114126118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Cox A. D., Fesik S. W., Kimmelman A. C., Luo J., Der C. J., Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 828–851 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock J. F., Ras proteins: Different signals from different locations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 373–384 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prior I. A., Lewis P. D., Mattos C., A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 72, 2457–2467 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancock J. F., Parton R. G., Ras plasma membrane signalling platforms. Biochem. J. 389, 1–11 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakoshi H., et al. , Single-molecule imaging analysis of Ras activation in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7317–7322 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plowman S. J., Muncke C., Parton R. G., Hancock J. F., H-ras, K-ras, and inner plasma membrane raft proteins operate in nanoclusters with differential dependence on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15500–15505 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian T., et al. , Plasma membrane nanoswitches generate high-fidelity Ras signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 905–914 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y., Hancock J. F., Ras nanoclusters: Versatile lipid-based signaling platforms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 841–849 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancock J. F., Cadwallader K., Marshall C. J., Methylation and proteolysis are essential for efficient membrane binding of prenylated p21K-ras(B). EMBO J. 10, 641–646 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock J. F., Cadwallader K., Paterson H., Marshall C. J., A CAAX or a CAAL motif and a second signal are sufficient for plasma membrane targeting of ras proteins. EMBO J. 10, 4033–4039 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock J. F., Paterson H., Marshall C. J., A polybasic domain or palmitoylation is required in addition to the CAAX motif to localize p21ras to the plasma membrane. Cell 63, 133–139 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., et al. , Signal integration by lipid-mediated spatial cross talk between Ras nanoclusters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 862–876 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y., Prakash P., Gorfe A. A., Hancock J. F., Ras and the plasma membrane: A complicated relationship. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 8, a031831 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y., et al. , Lipid-sorting specificity encoded in K-Ras membrane anchor regulates signal output. Cell 168, 239–251.e216 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmick M., et al. , KRas localizes to the plasma membrane by spatial cycles of solubilization, trapping and vesicular transport. Cell 157, 459–471 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowinsky E. K., Lately, it occurs to me what a long, strange trip it’s been for the farnesyltransferase inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 2981–2984 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sebti S. M., Der C. J., Opinion: Searching for the elusive targets of farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 945–951 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kattan W. E., et al. , Targeting plasma membrane phosphatidylserine content to inhibit oncogenic KRAS function. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201900431 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohn M., et al. , Lenz-Majewski mutations in PTDSS1 affect phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate metabolism at ER-PM and ER-Golgi junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 4314–4319 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser von Filseck J., et al. , Intracellular transport. Phosphatidylserine transport by ORP/Osh proteins is driven by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate. Science 349, 432–436 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., et al. , Immune cell production of interleukin 17 induces stem cell features of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia cells. Gastroenterology 155, 210–223.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baskin J. M., et al. , The leukodystrophy protein FAM126A (hyccin) regulates PtdIns(4)P synthesis at the plasma membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 132–138 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bojjireddy N., Guzman-Hernandez M. L., Reinhard N. R., Jovic M., Balla T., EFR3s are palmitoylated plasma membrane proteins that control responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Cell Sci. 128, 118–128 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon J., et al. , Targeting phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIα for radiosensitization: A potential model of drug repositioning using an anti-hepatitis C viral agent. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 96, 867–876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hancock J. F., Prior I. A., Electron microscopic imaging of Ras signaling domains. Methods 37, 165–172 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou T.-C., Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 70, 440–446 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bojjireddy N., et al. , Pharmacological and genetic targeting of the PI4KA enzyme reveals its important role in maintaining plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 6120–6132 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhikari H., et al. , Oncogenic KRAS is dependent upon an EFR3A-PI4KA signaling axis for potent tumorigenic activity. Nat. Commun. 12, 5248 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giroux V., Iovanna J., Dagorn J. C., Probing the human kinome for kinases involved in pancreatic cancer cell survival and gemcitabine resistance. FASEB J. 20, 1982–1991 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa S., et al. , The role of oxysterol binding protein-related protein 5 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 101, 898–905 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters A. M., Der C. J., KRAS: The critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8, a031435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biankin A. V., et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 491, 399–405 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones S., et al. , Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 321, 1801–1806 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sausen M., et al. , Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 6, 7686 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waddell N., et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 518, 495–501 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witkiewicz A. K., et al. , Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat. Commun. 6, 6744 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waring M. J., et al. , Potent, selective small molecule inhibitors of type III phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase α- but not β-inhibit the phosphatidylinositol signaling cascade and cancer cell proliferation. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 50, 5388–5390 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park Y., Park J. M., Kim D. H., Kwon J., Kim I. A., Inhibition of PI4K IIIα radiosensitizes in human tumor xenograft and immune-competent syngeneic murine tumor model. Oncotarget 8, 110392–110405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hobbs G. A., et al. , Atypical KRASG12R mutant is impaired in PI3K signaling and macropinocytosis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 10, 104–123 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaillancourt F. H., et al. , Evaluation of phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIα as a hepatitis C virus drug target. J. Virol. 86, 11595–11607 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindenbach B. D., Understanding how hepatitis C virus builds its unctuous home. Cell Host Microbe 9, 1–2 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corsello S. M., et al. , Discovering the anti-cancer potential of non-oncology drugs by systematic viability profiling. Nat. Can. 1, 235–248 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W., et al. , Impact of hepatitis C virus treatment on the risk of non-hepatic cancers among hepatitis C virus-infected patients in the US. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 52, 1592–1602 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung J., et al. , Intracellular transport. PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5- and ORP8-mediated ER-plasma membrane contacts. Science 349, 428–432 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Saint-Jean M., et al. , Osh4p exchanges sterols for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate between lipid bilayers. J. Cell Biol. 195, 965–978 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tong J., Yang H., Yang H., Eom S. H., Im Y. J., Structure of Osh3 reveals a conserved mode of phosphoinositide binding in oxysterol-binding proteins. Structure 21, 1203–1213 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghai R., et al. , ORP5 and ORP8 bind phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-biphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P 2) and regulate its level at the plasma membrane. Nat. Commun. 8, 757 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sohn M., et al. , PI(4,5)P2 controls plasma membrane PI4P and PS levels via ORP5/8 recruitment to ER-PM contact sites. J. Cell Biol. 217, 1797–1813 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witkiewicz A. K., et al. , Integrated patient-derived models delineate individualized therapeutic vulnerabilities of pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep. 16, 2017–2031 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster S. A., et al. , Activation mechanism of oncogenic deletion mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and HER2. Cancer Cell 29, 477–493 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen S. H., et al. , Oncogenic BRAF deletions that function as homodimers and are sensitive to inhibition by RAF dimer inhibitor LY3009120. Cancer Discov. 6, 300–315 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papke B., Der C. J., Drugging RAS: Know the enemy. Science 355, 1158–1163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerra C., Barbacid M., Genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 7, 232–247 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prior I. A., Muncke C., Parton R. G., Hancock J. F., Direct visualization of Ras proteins in spatially distinct cell surface microdomains. J. Cell Biol. 160, 165–170 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guzmán C., Bagga M., Kaur A., Westermarck J., Abankwa D., ColonyArea: An ImageJ plugin to automatically quantify colony formation in clonogenic assays. PLoS One 9, e92444 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.