Significance

Understanding the atomic-scale mechanism of crystallization is a fundamental issue in statistical mechanics and the basis for the synthesis of novel materials. We investigated the structures of single xenon nanoparticles at the early stage of formation by exploiting the femtosecond single-shot X-ray diffraction approach. We found the coexistence of a highly stacking-disordered structure and a stable face-centered cubic structure in the same single nanoparticles, suggesting that crystallization proceeds via an intermediate stacking-disordered phase. The results shine light on the early stages of condensed matter nucleation and demonstrate the effectiveness of the single-shot diffraction method for elucidating fast structural dynamics in atomic aggregates, feeding unique experimental information to nucleation and growth theory as well as to research and applications.

Keywords: crystallization kinetics, XFEL, X-ray diffraction

Abstract

Crystallization is a fundamental natural phenomenon and the ubiquitous physical process in materials science for the design of new materials. So far, experimental observations of the structural dynamics in crystallization have been mostly restricted to slow dynamics. We present here an exclusive way to explore the dynamics of crystallization in highly controlled conditions (i.e., in the absence of impurities acting as seeds of the crystallites) as it occurs in vacuum. We have measured the early formation stage of solid Xe nanoparticles nucleated in an expanding supercooled Xe jet by means of an X-ray diffraction experiment with 10-fs X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) pulses. We found that the structure of Xe nanoparticles is not pure face-centered cubic (fcc), the expected stable phase, but a mixture of fcc and randomly stacked hexagonal close-packed (rhcp) structures. Furthermore, we identified the instantaneous coexistence of the comparably sized fcc and rhcp domains in single Xe nanoparticles. The observations are explained by the scenario of structural aging, in which the nanoparticles initially crystallize in the highly stacking-disordered rhcp phase and the structure later forms the stable fcc phase. The results are reminiscent of analogous observations in hard-sphere systems, indicating the universal role of the stacking-disordered phase in nucleation.

Crystallization is one of the most ubiquitous physical phenomena in nature, yet its microscopic and mesoscopic mechanisms are not fully understood. Crystallization is generally assumed to start from nucleation, a nanometer-sized nucleus formation, which is followed by the nucleus growth. The initially grown phase structure has been a long-standing subject of controversy. Classical nucleation theory (CNT) (1, 2) assumes that nucleation occurs at a spherical crystallite having the stable lattice structure of the bulk. More than a century ago, Ostwald (3) pointed out the role of metastable phases in nucleation and advocated his step rule, which states that a metastable phase is initially formed and that it may change to the stable phase later. Alexander and McTague (4) argued that the initial phase would be body-centered cubic regardless of the stable phase structure. Meanwhile, a recent numerical simulation of ice nucleation (5) suggests that ice nucleation occurs in a stacking-disordered phase, thereby increasing the nucleation rate by several orders of magnitude as compared with the CNT prediction. Understanding the structural dynamics upon crystallization is crucial for the creation of various new materials, as the structures and properties of the final product are crucially influenced by the kinetic pathway of the phase transition. To date, the nonequilibrium dynamics upon crystallization have been extensively studied numerically, whereas experimental observations have been mostly restricted to slow dynamics, such as crystallization of colloids (6) and proteins (7), or more recently, to the crystallization of supercooled liquids (8).

The crystallization dynamics in atomic systems is challenging to investigate experimentally. First, sufficiently high temporal resolution and atomic spatial resolutions are required to resolve transient structures emerging upon crystallization. Second, orientation and ensemble averaging of the structural information can lead to significant structural detail loss in individual crystallites; nevertheless, the averaged information is helpful in identifying the phase in the early stages of crystallization. Third, growth in the presence of a substrate would influence the nucleation and growth process, potentially causing disagreement with theories. Recently, ultrashort and intense X-ray pulses from X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) (9, 10) became available, providing novel opportunities for the structural determination of fragile samples, such as aerosol particles (11), superfluid nanodroplets (12), and live biospecimens (13). In single-shot diffraction experiments using XFELs, instantaneous structures of single free-flying nanoparticles can be captured with snapshot exposures of femtosecond X-ray pulses. Therefore, single-shot diffraction has the potential to overcome the above-mentioned technical challenges. Although the structural determination of single small nuclei at the critical stage (typically consisting of several hundred atoms) is not achievable with the current fluence of XFEL beams, the structure of the initially grown phase can be inferred by examining larger crystals immediately after the growth.

In this study, we demonstrate the uniqueness of the single-shot diffraction to conclusively elucidate the structural dynamics upon crystallization. We investigate the structure of Xe nanoparticles crystallized in a supercooled Xe gas jet by single-shot and single-particle diffraction using XFEL pulses. Rare-gas systems are suitable atomic model systems for investigating the structural dynamics upon crystallization as the atomic interactions are well approximated by the simple Lennard–Jones interaction. In addition, the absence of interaction between the sample and a supporting substrate provided us with an ideal experimental environment for the investigation of the homogeneous nucleation process. The comparison of the experimental diffraction data with numerical simulation results revealed the coexistence of the face-centered cubic (fcc) and randomly stacked hexagonal close-packed (rhcp) phases in single Xe nanoparticles. Based on our observations, we discuss the crystallization kinetics of rare-gas nanoparticles in connection with the literature on crystallization of other systems, such as hard-sphere systems and water.

1. Experiment

Xe nanoparticles were nucleated and grown in a Xe gas jet cooled by adiabatic expansion through a conical nozzle (14). Single Xe nanoparticles were irradiated by XFEL pulses with a wavelength of 0.113 nm, and the wide-angle X-ray scattering signals were recorded on a shot-to-shot basis with a two-dimensional (2D) X-ray detector. The measurement satisfied an ideal single-particle diffraction condition, in which the average number of cluster hits per XFEL shot is 1. All the experimental details are described in Materials and Methods.

2. Results

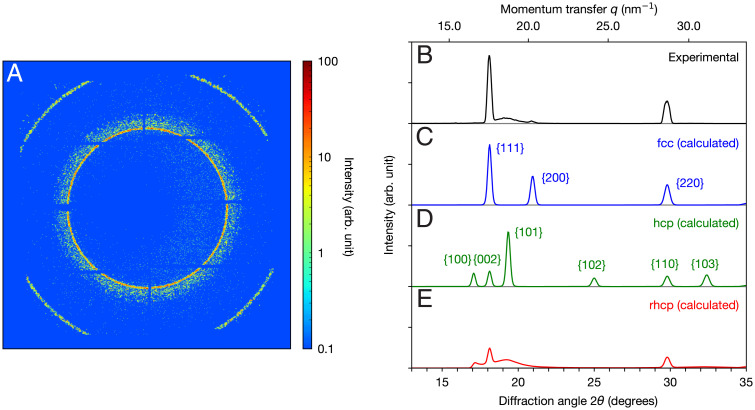

First, we investigate ensemble-averaged diffraction data to acquire the averaged structural information of the Xe nanoparticles. Fig. 1 A and B shows the 2D diffraction pattern and the angle-averaged powder diffraction pattern of the Xe nanoparticles accumulated over ∼ 1,500,000 X-ray shots, respectively (Materials and Methods). For comparison, calculated powder diffraction patterns for fcc (the stable phase in the bulk) and hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structures are displayed in Fig. 1 C and D (Materials and Methods). Basically, the fcc and hcp structures only differ in the stacking sequence of 2D hexagonal close-packed layers; fcc has an ABC stacking sequence, and hcp exhibits an ABAB stacking sequence. A comparison between the experimental and calculated patterns reveals that the broad peak at the diffraction angle in the experimental pattern cannot be explained by either fcc or hcp phases. In fact, the broad peak can be attributed to a structure consisting of hexagonal close-packed layers that randomly adopt either the fcc or hcp stacking sequence, the so-called rhcp (cf Fig. 2B). Fig. 1E shows the calculated powder diffraction pattern for the rhcp structure. The experimental powder pattern (Fig. 1B) is qualitatively explained by a sum of the fcc and rhcp phases. In particular, the slight 200 peak at is a signature of the fcc phase. Note that the relative peak intensities of the experimental powder pattern are not accurate owing to an incompleteness in the integration procedure of the diffraction intensities (Materials and Methods). Here, we would also like to point out that the data exhibit two disjoint sets of stacking orders, nearly faultless fcc and highly stacking-disordered rhcp structures, rather than a continuous distribution between these two extreme cases. As we will discuss later, the stacking order discreteness is presumably related to the crystallization kinetics of the Xe nanoparticles.

Fig. 1.

Experimental and simulated diffraction patterns of Xe nanoparticles. (A) A 2D diffraction pattern recorded on the detector. (B) An experimental powder diffraction pattern calculated by angle averaging (A). (C–E) Simulated powder diffraction patterns for the fcc, hcp, and rhcp structures with a particle diameter of 70 nm, respectively. The peaks in the experimental powder patterns are explained by either or both the fcc and rhcp structures. The peak broadening in the experimental diffraction pattern reflects the spatial distribution of the nanoparticles in the interaction region. The peak broadening effect is taken into account in the simulation and fitted to the experimental pattern (Materials and Methods).

Fig. 2.

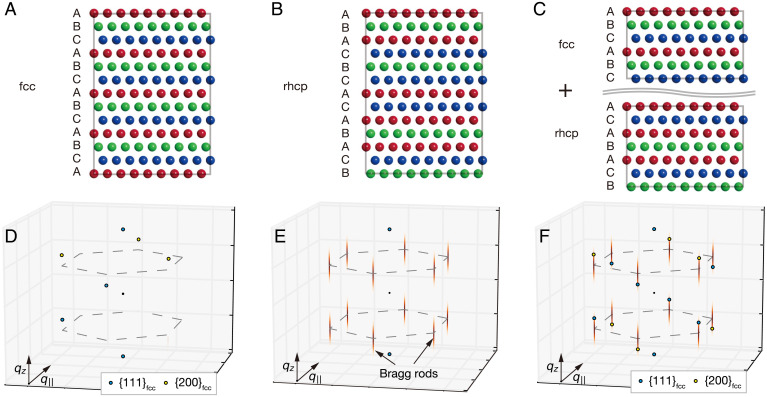

Crystal structures with different stacking orders and the corresponding 3D structure factors in the reciprocal space. (A) fcc with ABC stacking, (B) rhcp with fully random stacking, and (C) a joint structure of fcc and rhcp crystals. (D–F) Ensemble-averaged 3D structure factors in reciprocal space corresponding to the structures displayed in A–C, respectively.

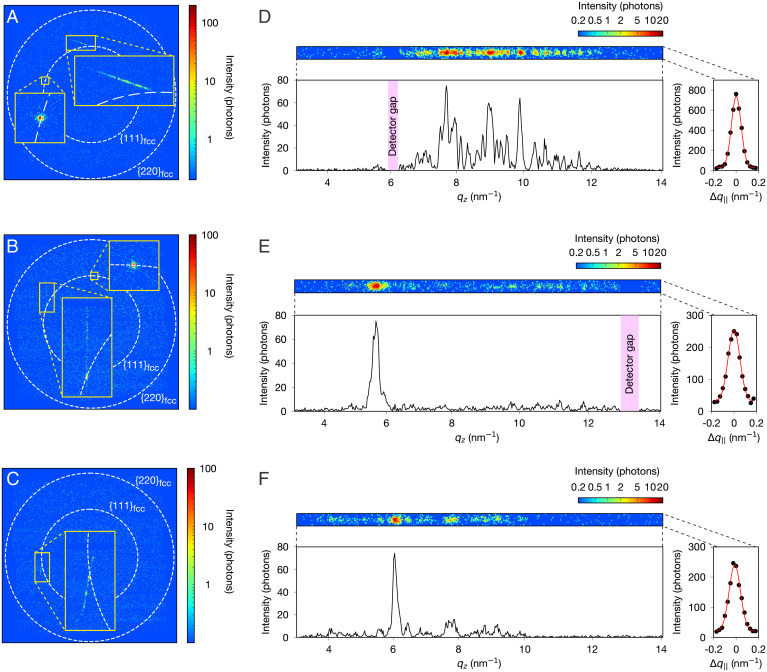

Next, we investigate the diffraction patterns in single-shot images to gain particle by particle structural information. Fig. 3 A–C displays representative examples of the single-shot diffraction patterns. Most of the diffraction patterns contain one Bragg spot at most, with a nearly circular intensity profile; however, we also obtained a small fraction of diffraction patterns with streak intensities. The streak patterns can be understood by considering the three-dimensional (3D) structure factor of the rhcp structure. Fig. 2 shows crystal structures with different stacking orders and the corresponding 3D structure factors in the reciprocal space. In the case of rhcp (Fig. 2 B and E), the structure factor exhibits sharp peaks on lines satisfying (h and k are Miller indices in the hexagonal basis, and n is an integer) and diffuse rod-like intensity distributions called Bragg scattering rods along lines with (15). The Bragg rods correspond to the streak intensities in the diffraction patterns. The streak patterns are observed accidentally depending on the crystal orientation when one of the Bragg rods is nearly tangential to the surface of the Ewald sphere. The 2D intensity profiles of the streak patterns and their vertical and horizontal projections are shown in Fig. 3 D–F. Each streak pattern exhibits a speckle pattern owing to the spatial coherence of the incident XFEL beam, reflecting the distribution of defects in the nanoparticles. The intensity distribution along the streak pattern is sensitive to the individual stacking sequence within the close-packed crystal (16), whereas the width perpendicular to the streak is inversely proportional to the length dimension of the stacking layers. From the horizontal projections of the streak patterns, the diameters of the crystals were evaluated to be (Fig. 3D) nm, (Fig. 3E) nm, and (Fig. 3F) nm, respectively (Materials and Methods). Note that, although the diffraction peak width is often used to evaluate the crystalline size in powder diffraction measurements, the crystal diameters estimated from the single-shot diffraction images may not be as accurate owing to the possible geometrical mismatch between the Bragg rods and the Ewald sphere. Also, the estimated diameters can be undervalued owing to other factors than the crystalline size contributing to the peak broadening (e.g., strain in the crystals and instrumental resolution).

Fig. 3.

Single-particle diffraction patterns of Xe nanoparticles. (A–C) Diffraction patterns on the 2D X-ray detector exhibit streak intensities. The streak patterns in B and C accompany sharp Bragg spots located on the ring. (D–F) Zoomed images of the streak patterns in A–C and their vertical and horizontal projections of the diffraction intensities. qz is the wave vector along the [111] direction, and is the perpendicular displacement of the wave vector from the rod (cf Fig. 2). The streak patterns show characteristic speckle patterns corresponding to the distribution of defects in individual particles.

Interestingly, the diffraction patterns displayed in Fig. 3 B and C exhibit streak intensities accompanying sharp Bragg spots located on the 111 Debye–Scherrer ring. Note that the slight relative shift of the sharp peaks in Fig. 3 E and F is presumably due to the shift of the sample position along the X-ray beam owing to the spatial distribution of the sample density in the interaction region. The streaked intensities originate from the rhcp structure, and the sharp fcc Bragg spots on the streaks only originate from a nearly perfect fcc structure. The only plausible explanation for these diffraction patterns (15) is that a nearly perfect fcc crystal and an rhcp crystal coexist in single Xe nanoparticles with the (111) plane of the fcc crystal jointed to the hexagonal plane of the rhcp crystal (as visualized in Fig. 2 C and F).

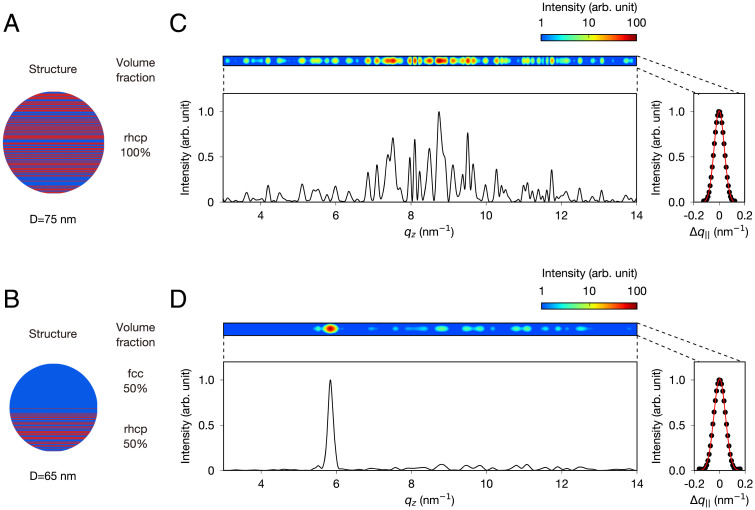

To verify the above-presented arguments, we carried out a numerical simulation of the streak patterns. Although the simulation does not allow unique structure determination from the experimental data, it provides quantitative information, specifically the approximate volume fraction of the fcc and rhcp crystals. We assumed a model structure in which a spherical particle is composed of rhcp or fcc crystalline domains stacked along one axis. The model is consistent with the recent results of imaging experiments of large Xe nanoparticles (17, 18) and with the nearly spherical profiles of Bragg spots that coincidentally appeared in the diffraction patterns. Fig. 4 shows the simulated streak patterns and the corresponding crystal structures. In the case of a pure rhcp crystal (Fig. 4A), the simulated pattern exhibits a characteristic speckle pattern along the streak (Fig. 4C), similar to the experimental pattern shown in Fig. 3D. Instead, when the particle is composed of uniaxially jointed fcc and rhcp crystals (Fig. 4B), we obtained streak patterns accompanying sharp fcc peaks (Fig. 4D). We varied the volume fraction between the fcc and rhcp crystals and obtained a semiquantitative agreement with the experimental patterns (specifically of the relative intensities between the streak and spot) (Fig. 3 E and F) when a structure with comparably sized fcc and rhcp crystals was assumed (SI Appendix, Fig. 1). Therefore, we conclude that some of the Xe nanoparticles consist of comparably sized rhcp and fcc crystals. Note that the speckle pattern varies depending on the stacking sequence in the rhcp crystal. For reference, the streak patterns simulated with different stacking sequences in the rhcp crystal are given in SI Appendix, Fig. 2.

Fig. 4.

Simulation results for the streak patterns. (A and B) Schematic of the structure used in the simulation: a spherical rhcp crystal (A) and a spherical hybrid structure consisting of 50% fcc and 50% rhcp domains (B). (C and D) Simulated diffraction patterns corresponding to the structures of A and B as well as their vertical and horizontal projections of the diffraction intensities. Details of the simulation are in Materials and Methods.

3. Discussions

The single-particle structural information on the Xe nanoparticles poses a puzzling question about the origin of the structure. To date, the structure of rare-gas nanoparticles has been discussed mainly in the context of a size-dependent structural transition (19–23). However, the size-dependent scenario does not seem to explain the coexistence of the rhcp and fcc structures in single nanoparticles. In addition, the particle size of the present Xe nanoparticles is significantly larger than the size region where the size-dependent structural transition is expected to occur (i.e., the stable phase of the present large Xe nanoparticles is likely to be fcc). In a separate analysis of the present dataset (24), we found no signature of icosahedral structures with multiply twinned domains, which is the stable structure for small clusters (19, 20). Although the possibility of the rhcp structure has been once suggested in Ar nanoparticles in a smaller-sized region (22), it is surprising that the rhcp structure persists in the present larger Xe nanoparticles. The present observations indicate that the kinetics of crystallization, rather than thermodynamic stability, plays an important role in determining the structure of the Xe nanoparticles. Here, we would like to emphasize that detailed insights into the crystallization kinetics are only accessible with the single-shot and single-particle approach, which can capture the snapshots of single nanoparticles upon crystallization.

Next, we would like to understand the two-phase coexistence in single Xe nanoparticles. We have found a possible solution to the question in the analogy between the rare-gas system and the colloidal hard-sphere system. Here, we summarize the results of existing studies on the hard-sphere system to clarify the analogy. Hard-sphere colloids suspended in a solvent have been widely studied as a simple model for various phenomena in condensed matter physics, such as crystallization and glass transition (25). Basically, the hard-sphere system is closely related to the rare-gas system, as it can be regarded as a model system for the short-range repulsive interaction of rare-gas atoms, which plays a central role in crystallization. Theories have shown that the most stable structure of the hard-sphere crystal is fcc (26). However, an early experiment by Pusey et al. (27) reported that the structure of colloidal hard-sphere crystals is purely rhcp when the sample is crystallized fast. Further studies (28–30) confirmed that the rhcp phase changes to the more stable fcc phase. The structural aging from the metastable rhcp to the stable fcc can be interpreted as a manifestation of Ostwald’s step rule (3), which states that phase transition proceeds via intermediate metastable phases.

The present experimental results are fully consistent with the scenario of structural aging observed in the colloidal hard-sphere system. First, the most stable phase is fcc in the rare-gas and hard-sphere systems in the bulk limit. As we will see later, the stable phase of the present large Xe nanoparticles () is expected to be fcc. Second, the powder diffraction pattern of the Xe nanoparticles exhibits the features of both fcc and rhcp structures. In fact, the hard-sphere colloidal crystals exhibit qualitatively the same powder patterns (28–30). More importantly, some single-particle diffraction patterns of the Xe nanoparticles show streak patterns accompanying sharp fcc peaks, indicating the coexistence of the rhcp and fcc phases along the stacking axis in single nanoparticles. Similar diffraction patterns have also been obtained from colloidal hard-sphere crystals in a single-crystal diffraction experiment (15), and the joint structure of rhcp and fcc was interpreted as a signature of the structural aging from rhcp to fcc. Considering the consistency, it is plausible to assume that the scenario of structural aging also applies to the present rare-gas nanoparticles.

Furthermore, our experimental results provide insights into the possible mechanisms of the rhcp–fcc transformation. There have been several mechanisms proposed to explain solid-to-solid transition between close-packed structures, such as phase transformation via an intermediate solid phase (23) and martensitic shear transformation (31–33). However, these mechanisms may give rise to an intermediate phase (23) or to intermediate stacking order (31–33) (i.e., moderately stacking-disordered phase in the rhcp–fcc transformation), in contrast to the present observations in Figs. 1B and 3 E and F. As an alternative scenario, the discreteness of the stacking order in the rhcp-to-fcc transformation of hard-sphere colloids was interpreted by a recrystallization mechanism via melting (15), where the fcc crystal grows at the (111) grain boundary at the expense of the rhcp crystal. In the present case, the recrystallization mechanism via fluid (melt or vapor) provides a simple and consistent explanation for the discreteness of the stacking order. It is of great concern to what extent other transformation mechanisms play a role, depending on the experimental conditions.

If the scenario of structural aging also applies to the rare-gas nanoparticles, what is the timescale of the structural aging in the rare-gas system? In colloidal hard-sphere crystals, the timescale is on the order of several months (15, 28, 34). However, in the case of atomic crystals, the timescale should be shortened by many orders of magnitude because of faster atom diffusion than that of considerably larger colloidal particles. We attempted to estimate the timescale based on the Wilson–Frenkel model employed in colloidal hard-sphere crystals (28, 34). Details of the calculation are given in Materials and Methods. The model gives a velocity of the crystal front of m/s, suggesting a timescale of s to grow a crystal with a 100-nm diameter. In the present experimental setup, the flight time of the Xe nanoparticles from the particle aggregation region (gas expansion nozzle) to the interaction region is estimated to be several hundred microseconds. Therefore, the calculation suggests that structural aging may proceed during the time elapsed between the initial growth and the observation. The estimation may indicate that a common physical phenomenon proceeds on more than 10 orders of magnitude different timescales in the rare-gas system and in the colloidal hard-sphere system.

The consideration above implies that the initial growth of the Xe nanoparticles occurs in the rhcp phase. This argument is confirmed in the hard-sphere system both theoretically (35) and experimentally (6). The emergence of the stacking-disordered phase at the first step of crystallization is generally explained by entropic stabilization of the stacking-disordered phase for small crystallites (5, 34, 35). The crystalline size dependence of the free energy difference between the rhcp and fcc crystallites is evaluated by (5, 34)

| [1] |

where is the volumetric term arising from the bulk free energy difference between the fcc and hcp phases is the contribution from the difference in interfacial energy of the fcc and hcp crystals, and ( is the number of layers in the crystallite) is the contribution from the entropy of mixing fcc and hcp layers. and are proportional to the cubic and the square of the linear dimension of the crystallite, respectively, and the favorable entropic term scales with . The different scaling behavior results in the relative stability of the stacking-disordered phase for small crystallites, promoting the nucleation in the stacking-disordered phase. For large Xe nanoparticles (), considering the bulk free energy difference (31), the one-dimensional (1D) stacking model gives a value of < 0.05 for the ratio of the favorable linear term to the unfavorable cubic term, indicating the overall stability of the fcc phase. Therefore, the persistence of the rhcp phase in the present large nanoparticles should be attributed to the kinetics of crystallization.

The above-mentioned consideration on the free energy landscape is general and therefore, may be applicable to the crystallization kinetics of any materials that can be stacking disordered. The formation of the stacking-disordered phases has been experimentally implied in the crystallization of parahydrogen (36) and also suggested in a numerical study on ice nucleation (5). The emergence of stacking-disordered phases at the initial step of crystallization is possibly a ubiquitous phenomenon in a wide variety of materials. Here, we note that, for a thorough understanding of the experimental and simulation results for the nucleation process, additional effects may have to be taken into account. For instance, a slight preference for the cubic stacking over the hexagonal stacking has been suggested in ice nucleation (5, 37), which was previously attributed to the larger number of planes on which stacking can occur. As another example, an experiment on the crystallization of block copolymer micelles (32) suggested the formation of the least hcp phase, which was speculated to originate from the Laplace pressure acting on the crystalline domains.

In conclusion, using single-shot and single-particle diffraction with an XFEL, we investigated the structures of single Xe nanoparticles crystallized in a supercooled gas jet. The present approach overcomes the issues of temporal and ensemble averaging of the structural information and the presence of interaction between the sample and a substrate. Through an analysis of single-particle diffraction patterns, we revealed the coexistence of the fcc and rhcp phases in single Xe nanoparticles. These observations are surprisingly analogous to those in hard-sphere colloidal crystals, in which the particles initially crystallize in the metastable rhcp phase, and the structure later transforms into the stable fcc phase. The observations offer fundamental insights into the kinetics of crystallization, specifically the role of the stacking-disordered phase at the initial step of crystallization. Contributing to a large body of research on the crystallization of colloidal model systems, the present study opens up exciting opportunities for real-time observations of crystallization dynamics in atomic systems. The next step of the research would involve real-time observation of the structural aging and the structure determination of small growing crystallites. Furthermore, the present findings demonstrate the feasibility of the direct real-time investigation of various nonequilibrium dynamics in atomic systems, including melting and glass transitions.

4. Materials and Methods

A. Experimental Details

The experiments were carried out at beamline 3 (38) of the SPring-8 Angstrom Compact Free-Electron Laser (SACLA) (10). The experimental geometry has been described in detail elsewhere (39, 40). The SACLA provided X-ray pulses with a wavelength of 0.113 nm (corresponding to a photon energy of 11.0 keV) at a repetition rate of 30 Hz. The averaged peak fluence at the reaction point was estimated to be photons per micrometer squared. The scattered X-rays were recorded on a shot by shot basis with a multiport charge-coupled device (MPCCD) sensor detector (41) located mm downstream from the interaction point.

Xe nanoparticles were nucleated and grown in pulsed Xe gas jets cooled by adiabatic expansion through a nozzle with a 200-m diameter and a 4 half-opening angle. The stagnation pressure and temperature were 3 MPa and K, respectively. The maximum cooling rate is estimated to be in the order of 107 K/s. According to the scaling law (14), the average number of atoms in the grown nanoparticles is estimated to be , corresponding to nm in diameter. The nanoparticle beam passed through two small skimmers with diameters of 0.4 and 2 mm and a slit before reaching the interaction point. The nanoparticle beam was diagnosed with an ion time-of-flight spectrometer (39) by measuring fragment ions ejected from the XFEL-irradiated Xe nanoparticles.

B. Data Analysis

The diffraction data of the Xe nanoparticles were recorded in the same beamtime as the previously reported time-resolved diffraction experiments of Xe nanoparticles (40). In the time-resolved experiments, structural damage in Xe nanoparticles irradiated by intense near-infrared (NIR) laser pulses was examined with delayed XFEL pulses in the same experimental geometry as in the present experiment. To avoid the influence of the NIR laser irradiation, we excluded the laser-pumped diffraction dataset, where a significant decrease in the diffraction intensities was observed after NIR irradiations (40). The data presented consist of 1) an unpumped dataset and 2) a dataset using the laser where we did not observe a drastic decrease in the diffraction intensities after laser irradiation, possibly due to the insufficient spatial overlap between the NIR laser and the XFEL beam. We confirmed that there is no significant difference between the powder diffraction patterns in datasets 1 and 2 (SI Appendix, Fig. 3), which contradicts the fact that the laser irradiation influenced the structures of the Xe nanoparticles. The number of analyzed images was in total.

The experimental powder diffraction pattern in Fig. 1A was calculated by the following procedure. First, an averaged dark image was subtracted from the MPCCD images. Thereafter, we filtered images with diffraction signals from the Xe nanoparticles by detecting blobs (connected areas with intensities higher than a threshold) in the images using a blob detection algorithm (42). The ratio of the number of images with diffraction signals to the total number of images was < 7%. The intensities of the detected blobs were integrated over all the recorded diffraction images. Finally, the accumulated 2D image was angle averaged and corrected for the detection area of the MPCCD detector and for the varying distance between the 2D flat detector and the sample (43). Here, we should note that the integration of diffraction intensities is not complete (i.e., the procedure cuts off diffuse scattering signals in the diffraction images) (SI Appendix, Fig. 4). The incompleteness in the integration procedure results in an underestimation of the diffraction intensities. The effect is more prominent for peaks originating from weak scattering intensities in the reciprocal space (e.g., the broad peak around originating from the rhcp phase). The effect is at least partially responsible for the mismatch in the relative peak intensities in the experimental and simulated powder patterns in Fig. 1 B–E. In particular, it is responsible for the disappearance of the prepeak from rhcp at , which originates from the large area of the intersection in the reciprocal space and not from peaks in the structure factor (27).

The streak patterns in Fig. 3 D–F were derived from the 2D diffraction images in Fig. 3 A–C by the following procedure. First, the diffraction image was rotated around the center of the Debye–Scherrer rings so that the streak is aligned horizontally (along the x axis). The xy coordinates of the rotated image are related to the 3D momentum transfer vector via

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

Here, L is the fixed camera length. The origin of the xy coordinate was taken as the center of the Debye–Scherrer rings.

qz and were calculated from by assuming a complete intersection of a Bragg rod and a locally flat surface of the Ewald sphere. qz is calculated by Pythagorean theorem:

| [5] |

where is the y coordinate corresponding to the peak of the horizontal projection of the streak and nm--1 is the momentum transfer of the reflections. is calculated via

| [6] |

where represents averaging over the xy coordinates within the streak image.

C. Simulation

Here, we present the procedure to calculate the streak patterns displayed in Fig. 4 C and D. We assumed spherical crystals consisting of one-dimensionally stacked close-packed layers. In the model, we ignored defects other than stacking faults (e.g., point defects and line defects) as well as the attenuation of the diffraction intensities by the thermal motion of atoms. We also neglected the photon bandwidth of the incident XFEL beam and assumed the X-ray beam monochromaticity. The lattice constant used in the simulation was derived from the experimental powder diffraction pattern. The stacking sequence in the rhcp crystal was determined by random numbers. The scattering intensity in the vicinity of the line was simulated based on the kinematical theory of diffraction (16). The detailed formulation is provided in SI Appendix .

The powder diffraction patterns in Fig. 1 C–E were computed by angle-averaged simulated 3D structure factors. First, we simulated the scattering intensity in the vicinity of the rods in a similar manner to the calculation of the streak patterns. In the case of the rhcp structure, the scattering intensity was averaged over 500 random stacking sequences. Considering the duplicity of equivalent rods, the scattering intensity was angle integrated and corrected with respect to the Lorentz and polarization factor. Finally, peak broadening in the diffraction patterns owing to the particle distribution along the XFEL beam was taken into account. From the experimental powder diffraction pattern, the sample thickness was estimated to be mm full width at half-maximum (FWHM), which is in reasonable agreement with the experimental geometry.

D. Evaluation of the Nanoparticle Diameter

In the case of the spherical 1D stacking model, particle diameter D is inversely proportional to the perpendicular width of the streak patterns (in FWHM):

| [7] |

where K is a constant of the order of unity. We performed a simulation of streak patterns from nanoparticles with different diameters and obtained K = 1.09. Note that the relation holds regardless of the stacking sequence in the crystal (fcc, rhcp, or joint structure of fcc and rhcp). The particle diameters were evaluated via Eq. 7 using the fitting results displayed in Fig. 3 D–F.

E. Estimation of the Timescale of Structural Aging

The timescale of the structural aging was estimated by the Wilson–Frenkel model employed in studies on colloidal hard-sphere crystals (28, 34). In the estimation, restacking in bulk and shear-induced restacking are ignored, and a crystal growth at the (111) grain boundary from a liquid is assumed. These assumptions are consistent with the joint structure of the fcc and rhcp crystals shown in Fig. 4B. The velocity of the fcc crystal front is calculated via

| [8] |

where is the free energy difference per atom between the liquid and fcc phases. D is the self-diffusion constant of the liquid, Λ is a characteristic length at which an atom should diffuse to be incorporated in the fcc crystal, and is a constant of order unity. We used Eq. 8 to estimate the velocity of the fcc crystal front using as the driving force, instead of , the tiny free energy difference between the fcc and rhcp phases . We approximated the free energy difference as half of the free energy difference between the fcc and hcp phases in a bulk solid: (31). The self-diffusion constant D of liquid Xe is in the order of m2/s (44). We adopted m (the distance between two atoms in a close-packed crystal) and .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the late Makoto Yao for his invaluable contributions to the present work. The experiments were performed at SACLA with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute and the program review committee (nos. 2016A8057 and 2016B8077). This study was supported by the X-Ray Free Electron Laser Utilization Research Project and the X-Ray Free Electron Laser Priority Strategy Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; by the Proposal Program of SACLA Experimental Instruments of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (Japan); by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants JP15K17487, JP16K05016, and JP21K20538; by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows JP19J14969; by CNR under the Japan–Italy Research Cooperative Program; and by the IMRAM Project. A.N. and T.N.H. acknowledge support from the Research Program for Next Generation Young Scientists of “Dynamic Alliance for Open Innovation Bridging Human, Environment and Materials” in the “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices.” Y.K., M.B., and C.B. acknowledge support from the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division. H.F. and K.U. acknowledge support from the Dynamic Alliance for Open Innovation Bridging Human, Environment and Materials. D.Y. acknowledges support from the Grant-in-Aid of Tohoku University Institute for Promoting Graduate Degree Programs Division for Interdisciplinary Advanced Research and Education. G.R., D.E.G., T.P., and A.C. acknowledge support from the NOXSS PRIN contract of MIUR, Italy. K.N. acknowledges support from the Research Program of “Dynamic Alliance for Open Innovation Bridging Human, Environment and Materials” in the “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices.” C.B. acknowledges the Swiss National Science Foundation, National Center of Competence in Research-Molecular Ultrafast Science and Technology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. B.O. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2111747118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The X-ray diffraction image data and the code used for the simulation are available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5581210) (45).

References

- 1.Volmer M., Weber A., Keimbildung in übersättigten Gebilden. Z. Phys. Chem. 119, 277–301 (1926). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker R., Döring W., Kinetische Behandlung der Keimbildung in übersättigten Dämpfen. Ann. Phys. 416, 719–752 (1935). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostwald W., Studien über die Bildung und Umwandlung fester Körper. Z. Phys. Chem. 22, 289–330 (1897). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander S., McTague J., Should all crystals be bcc? Landau theory of solidification and crystal nucleation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 702–705 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupi L., et al., Role of stacking disorder in ice nucleation. Nature 551, 218–222 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasser U., Weeks E. R., Schofield A., Pusey P. N., Weitz D. A., Real-space imaging of nucleation and growth in colloidal crystallization. Science 292, 258–262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yau S. T., Vekilov P. G., Quasi-planar nucleus structure in apoferritin crystallization. Nature 406, 494–497 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schottelius A., et al., Crystal growth rates in supercooled atomic liquid mixtures. Nat. Mater. 19, 512–516 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emma P., et al., First lasing and operation of an ångstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photonics 4, 641–647 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa T., et al., A compact X-ray free-electron laser emitting in the sub-ångström region. Nat. Photonics 6, 540–544 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loh N. D., et al., Fractal morphology, imaging and mass spectrometry of single aerosol particles in flight. Nature 486, 513–517 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez L. F., et al., Shapes and vorticities of superfluid helium nanodroplets. Science 345, 906–909 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Schot G., et al., Imaging single cells in a beam of live cyanobacteria with an X-ray laser. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagena O. F., Nucleation and growth of clusters in expanding nozzle flows. Surf. Sci. 106, 101–116 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolbnya I. P., Petukhov A. V., Aarts D. G. A. L., Vroege G. J., Lekkerkerker H. N. W., Coexistence of rhcp and fcc phases in hard-sphere colloidal crystals. Eur. Lett. 72, 962–968 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davtyan A., Biermanns A., Loffeld O., Pietsch U., Determination of the stacking fault density in highly defective single GaAs nanowires by means of coherent diffraction imaging. New J. Phys. 18, 063021 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rupp D., et al., Identification of twinned gas phase clusters by single-shot scattering with intense soft x-ray pulses. New J. Phys. 14, 055016 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishiyama T., et al., Refinement for single-nanoparticle structure determination from low-quality single-shot coherent diffraction data. IUCrJ 7, 10–17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farges J., de Feraudy M. F., Raoult B., Torchet G., Noncrystalline structure of argon clusters. I. Polyicosahedral structure of ArN clusters, . J. Chem. Phys. 78, 5067–5080 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farges J., de Feraudy M. F., Raoult B., G.. Torchet, Noncrystalline structure of argon clusters. II. Multilayer icosahedral structure of ArN clusters . J. Chem. Phys. 84, 3491–3501 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Waal B. W., Icosahedral, decahedral, fcc, and defect-fcc structural models for ArN clusters, : How plausible are they? J. Chem. Phys. 98, 4909–4919 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Waal B., Torchet G., M. F.. de Feraudy, Structure of large argon clusters ArN, : Experiments and simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 331, 57–63 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krainyukova N. V., et al., Observation of the fcc-to-hcp transition in ensembles of argon nanoclusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 245505 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niozu A., et al., Characterizing crystalline defects in single nanoparticles from angular correlations of single-shot diffracted X-rays. IUCrJ 7, 276–286 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson V. J., Lekkerkerker H. N. W., Insights into phase transition kinetics from colloid science. Nature 416, 811–815 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruce A. D., Wilding N. B., Ackland A. J., Free energy of crystalline solids: A lattice-switch Monte Carlo method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3002–3005 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pusey P. N., et al., Structure of crystals of hard colloidal spheres. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 2753–2756 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martelozzo V. C., Schofield A. B., Poon W. C. K., Pusey P. N., Structural aging of crystals of hard-sphere colloids. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 66, 021408 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kegel W. K., Dhont J. K. G., “Aging” of the structure of crystals of hard colloidal spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 3431–3436 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Z., Chaikin P. M., Zhu J., Russel W. B., Meyer W. V., Crystallization kinetics of hard spheres in microgravity in the coexistence regime: Interactions between growing crystallites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 015501 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y., Ree T., Ree F. H., Crystal stability of heavy-rare-gas solids on the melting line. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 48, 2988–2991 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L., Lee H. S., Lee S., Close-packed block copolymer micelles induced by temperature quenching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 7218–7223 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L., Lee H. S., Zhernenkov M., Lee S., Martensitic transformation of close-packed polytypes of block copolymer micelles. Macromolecules 52, 6649–6661 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pronk S., Frenkel D., Can stacking faults in hard-sphere crystals anneal out spontaneously? J. Chem. Phys. 110, 4589–4592 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auer S., Frenkel D., Prediction of absolute crystal-nucleation rate in hard-sphere colloids. Nature 409, 1020–1023 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kühnel M., et al., Time-resolved study of crystallization in deeply cooled liquid parahydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 2–5 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore E. B., Molinero V., Is it cubic? Ice crystallization from deeply supercooled water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 20008–20016 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yabashi M., Tanaka H., Tono K., Ishikawa T., Status of the SACLA Facility. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 7, 604 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuzawa H., Nagaya K., Ueda K., Advances in instrumentation for gas-phase spectroscopy and diffraction with short-wavelength free electron lasers. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys Res. A 907, 116–131 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishiyama T., et al., Ultrafast structural dynamics of nanoparticles in intense laser fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 123201 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kameshima T., et al., Development of an X-ray pixel detector with multi-port charge-coupled device for X-ray free-electron laser experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 033110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradski G., The OpenCV Library. Dr Dobbs J. Softw. Tools 25, 120–125 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norby P., Synchrotron powder diffraction using imaging plates: Crystal structure determination and Rietveld refinement. J. Appl. Cryst. 30, 21–30 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naghizadeh J., Rice S. A., Kinetic theory of dense fluids. X. Measurement and interpretation of self-diffusion in liquid Ar, Kr, Xe, and CH 4. J. Chem. Phys. 36, 2710–2720 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niozu A., et al., Data and materials for “Crystallization kinetics of atomic crystals revealed by a single-shot and single-particle X-ray diffraction experiment.” Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.5581210. Deposited 2 December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray diffraction image data and the code used for the simulation are available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5581210) (45).