Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a muscle wasting disease caused by dystrophin deficiency. Vascular dysfunction has been suggested as an underlying pathogenic mechanism in DMD. However, this has not been thoroughly studied in a large animal model. Here we investigated structural and functional changes in the vascular smooth muscle and endothelium of the canine DMD model. The expression of dystrophin and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), neuronal NOS (nNOS), and the structure and function of the femoral artery from 15 normal and 16 affected adult dogs were evaluated. Full-length dystrophin was detected in the endothelium and smooth muscle in normal but not affected dog arteries. Normal arteries lacked nNOS but expressed eNOS in the endothelium. NOS activity and eNOS expression were reduced in the endothelium of dystrophic dogs. Dystrophin deficiency resulted in structural remodeling of the artery. In affected dogs, the maximum tension induced by vasoconstrictor phenylephrine and endothelin-1 was significantly reduced. In addition, acetylcholine-mediated vasorelaxation was significantly impaired, while exogenous nitric oxide induced vasorelaxation was significantly enhanced. Our results suggest that dystrophin plays a crucial role in maintaining the structure and function of vascular endothelium and smooth muscle in large mammals. Vascular defects may contribute to DMD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, canine model, vasculature, dystrophin, eNOS, nNOS, vasoconstriction, vasorelaxation

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe muscle wasting disease caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene [1,2]. Despite the discovery of the dystrophin gene and protein in 1987 [3,4], the pathogenic mechanisms of DMD remain not fully understood. In striated muscle, dystrophin links the extracellular matrix with the cytoskeleton. This interaction helps maintain sarcolemma stability during contraction. Dystrophin deficiency compromises the ability of the sarcolemma to sustain contraction-induced mechanical stress.

In addition to mechanical weakening of the sarcolemma, reduced blood supply has also been suggested as a putative disease mechanism in DMD [5,6]. To counteract sympathetic vasoconstriction during exercise, sarcolemma-associated neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) produces and releases nitric oxide (NO) to the surrounding vasculature to facilitate blood flow [7]. Dystrophin is responsible for anchoring nNOS to the sarcolemma [8,9]. In the absence of dystrophin, nNOS delocalizes from the sarcolemma, resulting in inadequate perfusion during muscle contraction and subsequent ischemic damage [8,10,11].

Mouse studies suggest that besides nNOS delocalization-associated functional ischemia, nNOS-independent vascular dysfunction may also contribute to DMD pathogenesis. It has been shown that microvascular defects contribute to DMD pathogenesis [12]. Increasing microvascular density ameliorated muscle disease in the mouse DMD model [13–15]. In contrast, studies performed in large-size arteries found dystrophin expression in vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells in normal mice, but not mdx mice [16–18]. Interestingly, one study suggested that dystrophin was complexed with endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in vascular endothelial cells [18]. Importantly, studies performed in large-size arteries suggest that flow (sheer stress)-induced, but not acetylcholine-induced, endothelium-dependent vasodilation was impaired in the absence of dystrophin [16,17,19–22]. Intriguingly, no functional abnormality was observed in the smooth muscle of large-size arteries in dystrophin-null mice [16,17,19,22]. Nonetheless, the dystrophic phenotype in the mouse DMD model was attenuated by smooth muscle-specific expression of dystrophin [23].

While results from the murine DMD model have revealed the importance of dystrophin in regulating vascular function, the implication to human disease is limited because dystrophin-null mice do not show characteristic symptoms of muscular dystrophy. Dystrophin-deficient dogs (referred to as DMD dogs in this manuscript) display a severe phenotype that parallels the clinical course in human patients, and hence are regarded as a better preclinical DMD model to study disease mechanisms and test therapeutic strategies [24–26]. To better understand the consequence of dystrophin deficiency in large vessels of the canine DMD model, here we characterized the structure and function of the femoral artery in normal and dystrophic dogs. We found that dystrophin expression was abolished and eNOS expression was reduced. Further, we observed significant structural remodeling in the femoral artery of dystrophic dogs. In physiological assays, we found that the maximum tension induced by vasoconstrictor was significantly decreased and acetylcholine-induced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation was significantly attenuated in the canine DMD model. Interestingly, exogenous nitric oxide (NO)-induced vasorelaxation was significantly enhanced in affected dogs. Our findings not only shine new light on the role dystrophin plays in the vasculature but also deepen our understanding of a vascular contribution to muscle disease in DMD.

Materials and methods

All chemical, biochemical and molecular biology reagents are available through commercial sources except for dystrophin R17 antibody Manex 44A and the utrophin antibody Mancho11 which were a kind gift from Dr. Glenn Morris at the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital (Oswestry, UK) [27].

Experimental animals.

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri and were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Femoral arteries from 15 normal and 16 DMD adult dogs were studied (Table 1). The sample size for all experiments is shown in supplementary material, Table S1 Both male and female dogs were used in the study. All experimental dogs were on a mixed genetic background of golden retriever, Labrador retriever, beagle, and Welsh corgi and were generated in house by artificial insemination. All DMD dogs carried null mutations in the dystrophin gene. The genotype was determined by PCR according to published protocols and confirmed by the significantly elevated serum creatine kinase level [28,29]. All affected dogs showed characteristic dystrophic histopathology and clinical presentation as we published before [25,26,28–36].

Table 1.

Experimental animals

| Normal | DMD | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 15 | 16 |

| Age (months) | 16.79 ± 1.92 | 12.76 ± 1.69 |

| Body weight (kg) | 19.84 ± 1.09 | 14.12 ± 1.12* |

Mean ± SEM;

Significantly different from the normal group.

All experimental dogs were housed in a specific-pathogen-free animal care facility and kept under a 12-h light/12-hdark cycle. DMD dogs were housed in a raised platform kennel while normal dogs were housed in a regular floor kennel. Depending on the age and size, two or more dogs were housed together to promote socialization. Normal dogs were fed dry Purina Lab Diet 5006 while DMD dogs were fed wet Purina Proplan Puppy food. All had ad libitum access to clean drinking water. Toys were allowed in the kennel with dogs for enrichment. Dogs were monitored daily by the caregivers for overall health condition and activity. A full physical examination was performed by the veterinarian from the Office of Animal Research at the University of Missouri for any unusual changes in behavior, activity, food and water consumption, or when clinical symptoms were noticed. The body weights of the dogs were measured periodically to monitor growth. Anesthetized experimental subjects were euthanized according to the 2013 AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals.

Drugs and solutions.

All drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The concentration of stock solutions is shown in supplementary material, Table S2 and the composition of the physiological salt solution and the Krebs buffer in supplementary material, Table S3.

Femoral artery ring preparation and set up.

A region of the femoral artery was collected from the same anatomical location in every dog at necropsy. Specifically, we collected the artery samples from within the femoral triangle and as close to the inguinal ligament as possible. The collected artery sample was immediately placed in cold (4 °C) physiological salt solution (PSS). Fat and connective tissues were carefully trimmed away under an Olympus SZ60 dissection microscope (Olympus America Inc. 3500 Corporate Parkway Center Valley, PA, USA) in cold PSS. The harvested artery was then segmented into artery rings and stored in cold PSS to preserve smooth muscle and endothelial function. Four adjacent rings (each ring about ~3.5 mm long) were obtained from each femoral artery. Three anatomical properties of the femoral artery ring were measured including the outer diameter (OD), inner diameter, and axial length (supplementary material, Figure S1). An image of each artery ring was acquired using an Olympus SZ60 dissection microscope and Spot Insight camera (Model 3.2.0; Diagnostic Instruments Inc. 6540 Burroughs Sterling Heights, MI, USA), and NIH ImageJ software was calibrated and used to obtain accurate measurements.

Physiological assays were conducted using an EZ-bath multi-channel isolated tissue organ bath system (GlobalTown Microtech Inc, Sarasota, FL, USA). The femoral artery ring was mounted on two stainless steel wires (supplementary material, Figure S2). One wire was connected to a force transducer to measure the developed tension while the other wire was connected to a microdrive for stretching the vessel by known increments in micrometers (supplementary material, Figure S2). Arterial rings were stretched to a passive tension of 2–3 grams for 1 h while they equilibrated in the oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Krebs buffer at 37 °C. Isometric tension (in grams) was continuously recorded using the LabChart physiological data acquisition and analysis software (AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia).

A length-tension curve was generated for each arterial ring. Specifically, the femoral artery ring was progressively stretched. The OD of the unstretched artery ring (Lo) was defined as 100%. Stretching was performed in two phases. In the first phase, the artery ring was stretched by an increment of 20% until the OD reached 160%. In the second phase, the artery ring was stretched by an increment of 10% until the OD reached 200%. After each stretch, 200 μl of stock KCl (3 M) was added to the bath to the final concentration of 30 mM (bath volume, 20 ml) to induce tension development. After three minutes, the bath contents were replaced with fresh Krebs buffer, and the next stretch was performed. The optimal length for a given artery ring (Lmax) was defined as the length at which contractile force evoked by KCl failed to increase by >5% of the previous measurement. In both normal and affected dogs, the Lmax was achieved at 190% Lo (supplementary material, Figure S3). After determination of the Lmax, the arterial ring was washed with the Krebs buffer until it returned to the resting tension. Arterial rings that did not develop tension in response to KCl when stretched up to 200% Lo were discarded. Subsequent experiments were all performed at the Lmax.

For anatomical measurements and baseline vascular reactivity to phenylephrine, acetylcholine, and SNP, 1 to 4 rings from each dog were studied (supplementary material, Table S1). For anatomical measurements and baseline vascular reactivity to endothelin-1, one ring from each dog were studied (supplementary material, Table S1). When more than one ring was studied in a dog, values from all studied rings were averaged and the mean value was used. In a subset of dogs (6 normal and 6 DMD), four rings were studied from each dog. In this set of the studies, the value from each individual ring was separately presented because every ring was treated differently. Ring 1 was the untreated control. Ring 2 was denuded to study endothelium-independent vascular responses. The endothelium was mechanically removed by gentle rubbing of the luminal surface with a pair of fine-tipped forceps. Ring 3 was pre-treated with nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NAME (300 mM) for 20 minutes before the start of each vascular reactivity protocol. Ring 4 was pre-treated with L-NAME (300 mM) and indomethacin (5 mM) for 20 minutes before the start of each vascular reactivity assay. Indomethacin is a cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor. COX is the enzyme responsible for prostaglandin production.

Vascular reactivity assay protocols.

Vasoconstriction was studied by evaluating the log-dose response to cumulative addition of phenylephrine (10−9 to 10−4 M) or endothelin-1 (10−10 to 10−7 M) to the vessel bath. Response to the contractile agonist was expressed as the developed tension (in grams; change from the resting tension) and specific tension (developed tension/area of the vessel). The arterial ring was then washed with the Krebs buffer until it returned to its resting tension.

To study vasodilation, the artery ring was first treated with 10−6 M phenylephrine to induce vasoconstriction. The phenylephrine concentration was experimentally determined using the above phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction protocol. At this concentration, normal and DMD dog arteries yielded similar levels of developed and specific tension. After 10 mins of stable developed tension, endothelium-dependent relaxation was determined by evaluating the log-dose response to cumulative addition of acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−4 M) or SNP (10−10 to 10−4 M) to the vessel bath. Percent relaxation for each dose of the vasodilator was determined as percent reduction in phenylephrine-induced tension. The arterial ring was then washed with the Krebs buffer until it returned to its resting tension.

Morphology studies.

Freshly collected femoral artery rings were embedded in Tissue-Tek Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and snap-frozen in 2-methylbutane with liquid nitrogen. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was used to study general histology. Fibrosis and calcification were evaluated by Masson’s trichrome staining and alizarin red staining, respectively, according to our published protocols [37,38]. Immune cell infiltration was evaluated by immunohistochemical staining using the ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to our published protocols [29]. Canine specific neutrophil, macrophage, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:8000, 1:2000, 1:1000 and 1:200, respectively (AbD Serotec). Histochemical evaluation of in situ NOS activity was performed according to a published protocol [39]. Positive NOS activity staining appeared as blue color under bright field microscopy.

To quantify the thickness of the tunica media and the tunica adventitia, tissue sections were stained with an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) without adding the primary antibody. The tunica adventitia was defined as the layer that was composed of collagen and elastic fibers. The loose connective tissue at the periphery of the vessel was eliminated from quantification due to its variable and inconsistent nature. The tunica media was the smooth muscle layer, and it was defined as the layer between the internal elastic lamina and the tunica adventitia.

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out according to previously published protocols [40]. Dystrophin expression was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of dystrophin (1:200 dilution; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Catalog # RB-9024-P0) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against dystrophin spectrin-like repeat 17 (Manex 44A) (1:500 dilution; a gift of Dr. Glenn Morris) [32]. eNOS expression was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of eNOS (1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; Catalog # ab5589). nNOS expression was evaluated using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of nNOS (1:2000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich; Catalog # N7280) [11]. Specificity of the staining was confirmed with secondary antibody-only controls (no primary antibody added during immunostaining).

Western blotting.

Freshly collected femoral artery segments were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. On the day of protein lysate preparation, femoral artery segments were cut longitudinally and pinned to expose the lumen. Endothelial cells were then collected into the ice-cold cell lysis buffer containing 10% Triton X-100, 10% NP-40, 3M NaCl, 0.5M EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5M EGTA (pH 8.0), 1M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), and 2% protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Specifically, the ice-cold cell lysis buffer was applied on the endothelial surface. The endothelial layer was then gently scraped using a blade to obtain an endothelial enriched sample according to a published protocol [41,42]. Cells were lysed in ice-cold cell lysis buffer on ice for 20 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm (Sorvall Legend Micro 21R centrifuge, Thermo Scientific) at 4 °C for 50 min. The supernatant was then collected into new microcentrifuge tubes and protein concertation was determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Remaining femoral artery segments were then rinsed in PBS and homogenized in tissue homogenization buffer (10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 5 mM EDTA, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) and 2% protease inhibito. The homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm (Sorvall Legend Micro 21R centrifuge) for 3 min. The supernatant was collected into new microcentrifuge tubes and protein concentration measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit. Western blotting of endothelial and smooth muscle cell fractions were carried out as described [40]. The purity of the endothelial cell fraction and smooth muscle fraction was confirmed by probing the blots with antibodies to CD31 (endothelial marker) and α-smooth muscle actin (smooth muscle marker). The following primary antibodies were used : a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of dystrophin (ThermoFisher Scientific; Catalog # RB-9024-P0; 1:100 dilution), a mouse monoclonal antibody against utrophin (Mancho11) (1:200 dilution, gift of Dr. Glenn Morris), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of nNOS (Sigma-Aldrich; Catalog # N7280; 1:2,000 dilution), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminus of eNOS (Abcam; Catalog # ab5589; 1:500 dilution), a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD31 (1:200 dilution; LSBio; Catalog # LS-B10502), a mouse monoclonal antibody against α-smooth muscle actin (1:1000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich; Catalog # A2547), and a mouse monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich; Catalog # T5168; 1:3,000 dilution). Densitometry quantification was performed using the Li-COR Image Studio version 5.0.21 software (https://www.licor.com). The relative intensity of the protein was normalized to the corresponding α-tubulin band in the same blot.

Data analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Sample size refers to the number of dogs used in the study (not the number of rings used in the study). Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad PRISM software version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data distributions were checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. To compare the statistical significance between normal and affected dogs (two group comparison), unpaired Student’s t-tests were used for parametric data, and the Mann–Whitney test for non-parametric data. One-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey post hoc or Holm–Sidak post hoc analysis was used to compare vascular responses (developed tension, specific tension, and % relaxation) to different concentrations of phenylephrine, endothelin-1, acetylcholine and SNP under each condition (control, denuded, L-NAME treated, or L-NAME/indomethacin co-treated), within the same group (normal or affected). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare vascular responses to different concentrations of phenylephrine, endothelin-1, acetylcholine and SNP under all conditions (control, denuded, L-NAME treated, and L-NAME/indomethacin co-treated), within the same group (normal or affected; developed tension, specific tension, or % relaxation). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Dystrophin expression was abolished in the vascular endothelium and smooth muscle in DMD dogs.

Femoral arteries from 15 normal dogs (mean age, 16.79 ± 1.92 months; age range, 8.4 to 34.4 months) and 16 DMD dogs (mean age, 12.76 ± 1.69 months; age range, 5.8 to 24.2 months) were evaluated (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in the age between normal and DMD dogs. As we reported previously, the body weight of DMD dogs was significantly decreased (Table 1) [11].

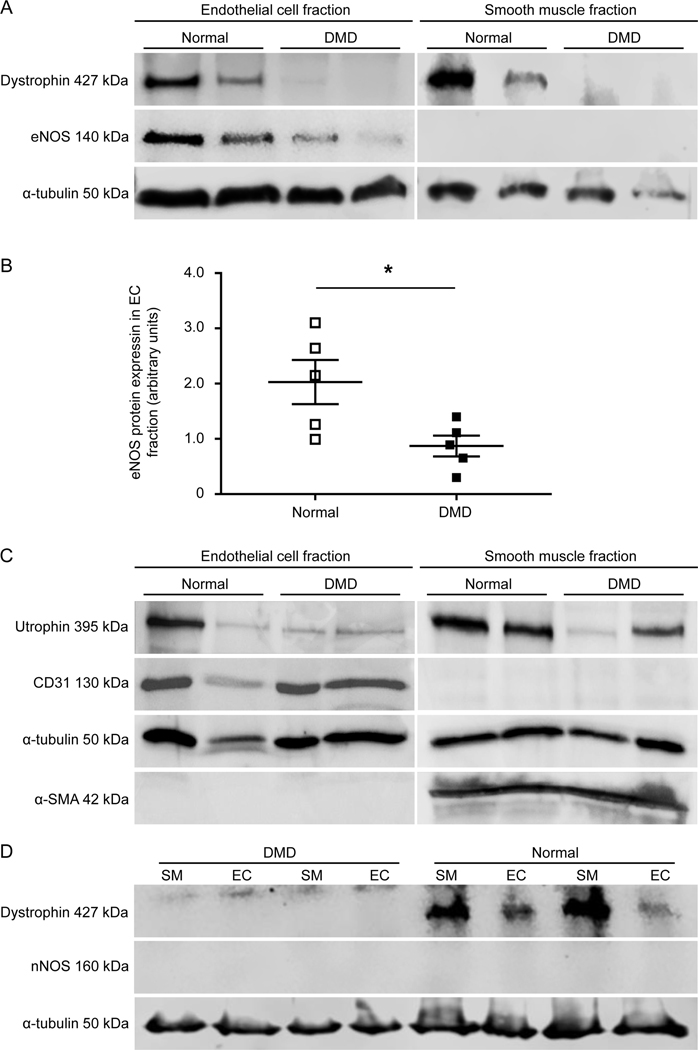

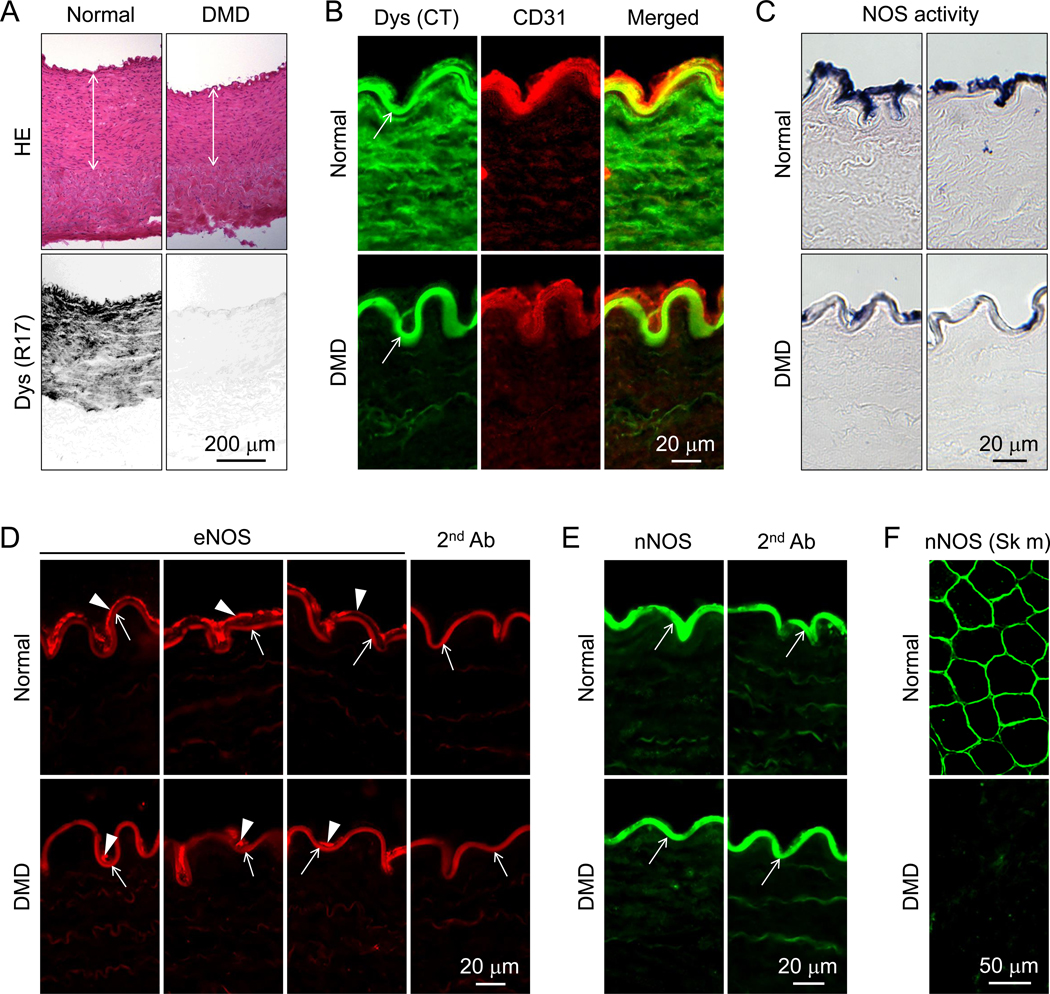

Dystrophin expression was examined by immunofluorescence staining and western blot (Figures 1 and 2, supplementary material, Figures S4 and S5). Robust dystrophin expression was detected in smooth muscle and endothelial cells in the femoral artery of normal dogs (Figure 1A,B, Figure 2A,D, supplementary material, Figures S4 and S5). DMD dogs showed no dystrophin expression. Utrophin, a paralogue of dystrophin, was detected in smooth muscle and endothelial cells in both normal and DMD dogs by western blot (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure S5). Next, we examined dystrophin expression in the vena cava by immunofluorescence staining. Consistent with what we saw in the femoral artery (Figure 1, supplementary material, Figures S4A,B), dystrophin was detected in both smooth muscle and endothelial cells in the vena cava of normal, but not DMD, dogs (supplementary material, Figure S4C).

Figure 1. Histological evaluation of dystrophin, eNOS and nNOS expression and NOS activity in normal and DMD dog femoral arteries.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of HE staining (top panels) and dystrophin immunostaining (bottom panels). Double arrowhead marks the location of the tunica media. Dys (R17), Immunostaining was performed using an antibody that recognizes dystrophin spectrin-like repeat 17. (B) Representative photomicrographs of dystrophin and CD31 immunostaining. Arrow, non-specific fluorescence signal at the internal elastic lamina; Dys (CT), Immunostaining was performed using an antibody that recognizes the C-terminal domain of dystrophin; CD31, Immunostaining was performed using an antibody that recognizes CD31, an endothelial marker. (C) Representative photomicrographs of in situ NOS activity staining. NOS activity is revealed by intense dark blue staining. (D) Representative photomicrographs of eNOS immunostaining. Arrowhead, eNOS expression in the tunica intima; Arrow, non-specific fluorescence signal at the internal elastic lamina; 2nd Ab, Staining was performed in the absence of the primary antibody. (E) Representative photomicrographs of nNOS immunostaining. Arrow, non-specific fluorescence signal at the internal elastic lamina; 2nd Ab, Staining was performed in the absence of the primary antibody. (F) Representative nNOS immunostaining photomicrographs of normal and DMD skeletal muscle. Scale bar applies to all the images in the same panel.

Figure 2. Biochemical evaluation of dystrophin, eNOS and nNOS expression in normal and DMD dog femoral arteries.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of the cropped dystrophin, eNOS, and α-tubulin western blots from endothelial and smooth muscle fractions. α-tubulin was used as the loading control. Raw data are shown in supplementary material, Figure S5. (B) Densitometry quantification of eNOS expression in endothelial cells of normal (n=5) and DMD (n=5) dogs. Asterisk, significantly different between normal and DMD. (C) Representative photomicrographs of the cropped utrophin, CD31, α-tubulin, and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) from endothelial and smooth muscle fractions. (D) Representative photomicrographs of the cropped dystrophin, nNOS, and α-tubulin western blots from endothelial and smooth muscle fractions. α-tubulin was used as the loading control. Uncropped blots are shown in supplementary material, Figure S5.

eNOS expression and NOS activity were reduced in DMD dogs.

On immunofluorescence staining and enzymatic activity staining, eNOS and NOS activity were observed, respectively, in the endothelium of both normal and DMD dogs; however, staining was substantially decreased in DMD dogs (Figure 1C,D). To quantify eNOS expression, we harvested the endothelium fraction and smooth muscle fraction and performed western blot (Figure 2A,B and supplementary material, Figure S5). Consistent with the staining results, eNOS was not detected in smooth muscle in either normal or DMD dogs. Though eNOS was present in the endothelium in both normal and DMD dogs, quantification revealed a significant reduction of the eNOS level in DMD dogs (Figure 2C). Similarly, eNOS expression was detected in the endothelium of the vena cava in normal, but not DMD, dogs by immunofluorescence staining (supplementary material, Figure S4C).

nNOS was not expressed in the dog femoral artery.

To evaluate nNOS expression, we used an nNOS antibody that has been validated in our previous studies [11]. On immunostaining, we only detected a strong non-specific autofluorescence signal at the internal elastic lamina. The non-specific signal was detected even in the absence of the nNOS antibody (Figure 1E). [Note, similar non-specific fluorescence signal was detected at the internal elastic lamina in Figure 1B and D]. To exclude potential technical errors in the staining procedure, we performed side-by-side immunostaining using the same protocol and the same antibody in dog skeletal muscle. Sarcolemmal localized nNOS was readily observed in normal but not DMD dog muscle (Figure 1F). To confirm immunostaining results, we performed western blot using lysates extracted from both the endothelium fraction and smooth muscle fraction. No band was detected at the expected size (Figure 2D and supplementary material, Figure S5).

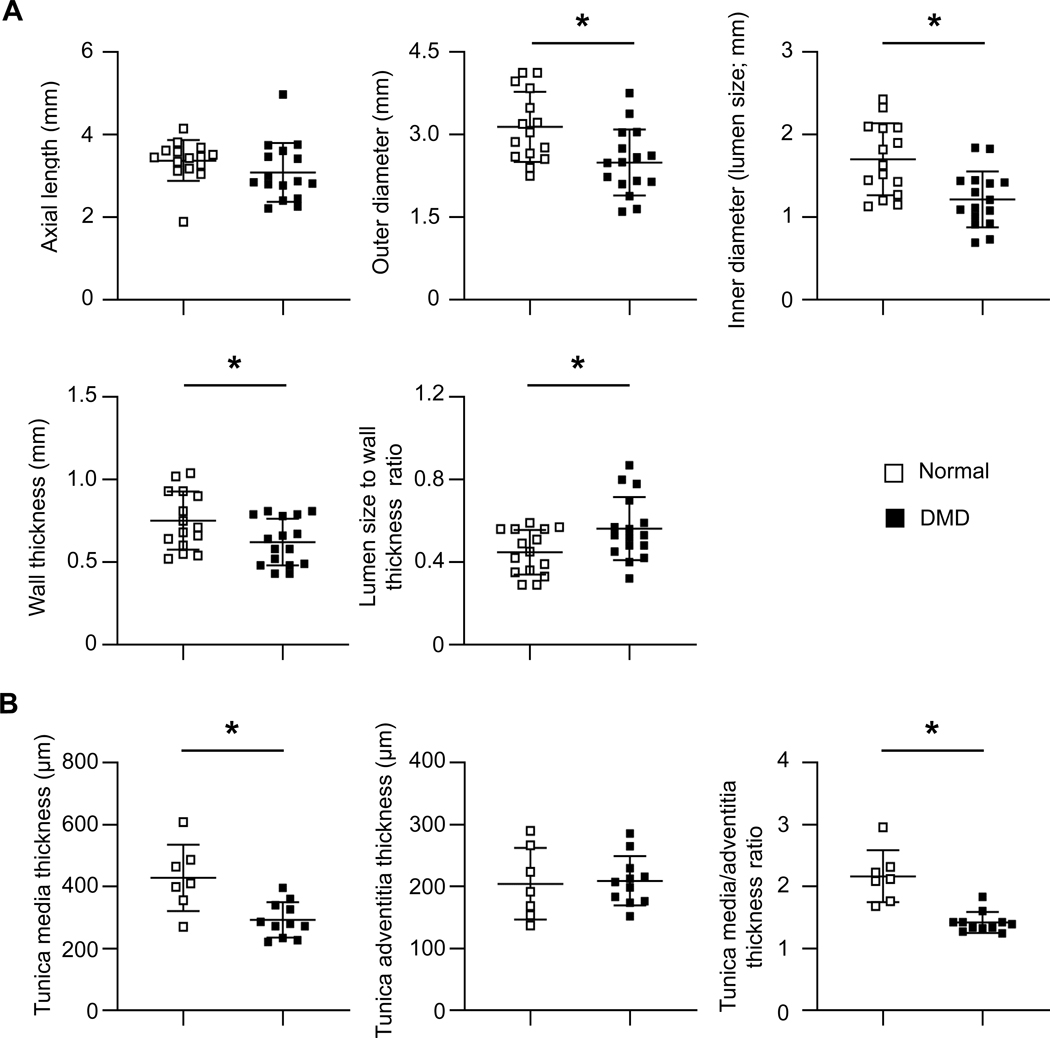

Dystrophin deficiency resulted in vascular remodeling.

On anatomical measurement (Figure 3A and supplementary material, Figure S1A), the axial length was similar between normal and DMD dogs (Figure 3A). However, the OD, lumen size (inner diameter), and wall thickness of DMD dog femoral arteries were significantly smaller than those of normal dogs (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Quantitative characterization of normal and DMD dog femoral arteries by anatomic and histological measurements.

(A) Anatomic quantification of the axial length, outer diameter, inner diameter, wall thickness, and lumen size to wall thickness ration of normal (n=15) and DMD (n=16) dog femoral artery rings. (B) Histological quantification of the thickness of the tunica media and tunica adventitia, and the ratio of the tunica media thickness to tunica adventitia thickness of normal (n=7) and DMD (n=11) dog femoral arteries. Asterisk, significantly different between normal and DMD.

On histological examination (Figure 3B, supplementary material, Figure S1B), both normal and DMD dog vessels maintained all three layers of the vessel (tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia). No apparent differences were seen in the constituents of each layer (Figure 1A, supplementary material, Figure S1B). However, the thickness of the tunica media and the ratio of tunica media to tunica adventitia were significantly decreased in DMD dogs (Figure 3B). Fibrosis, calcification and infiltration of inflammatory cells (neutrophils, macrophages, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) were examined by Masson-trichrome staining, alizarin red staining, and immunohistochemical staining, respectively. Fibrotic tissue was mainly detected in the tunica adventitia and there was no apparent difference in this layer between normal and DMD dogs (supplementary material, Figure S6). Calcium deposits were readily spotted in the tunica media in DMD dogs but not in normal dogs (supplementary material, Figure S6). Both normal and DMD dog vessels showed nominal inflammatory cell infiltration (supplementary material, Figure S6).

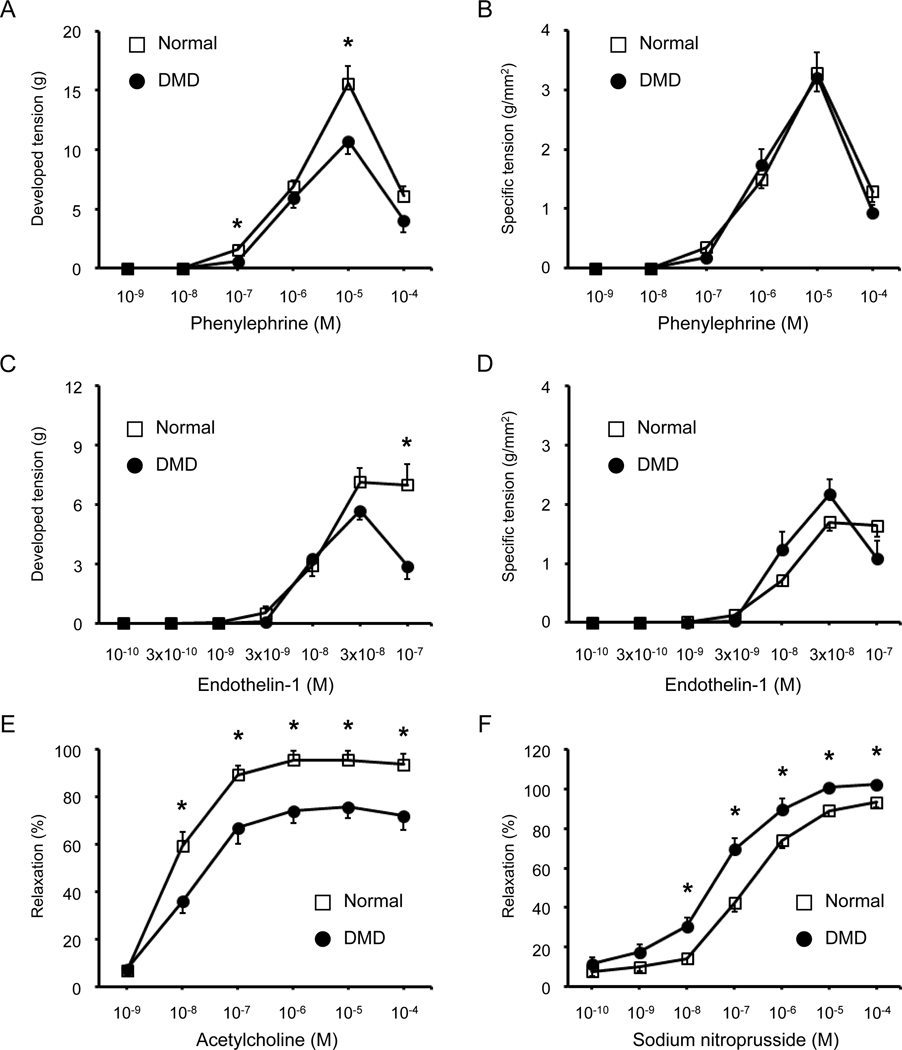

Vasoconstriction was partially compromised in DMD dogs.

We first examined the length-tension curve following passive stretch (supplementary material, Figure S3A). Similar patterns were detected in normal and DMD dogs. In both normal and DMD dogs, the optimal length of the artery ring (Lmax) was achieved when the OD was stretched to the 190% of Lo (supplementary material, Figure S3A). The resting tension at Lmax and the specific resting tension at Lmax showed no significant difference between normal and DMD dogs (supplementary material, Figure S3).

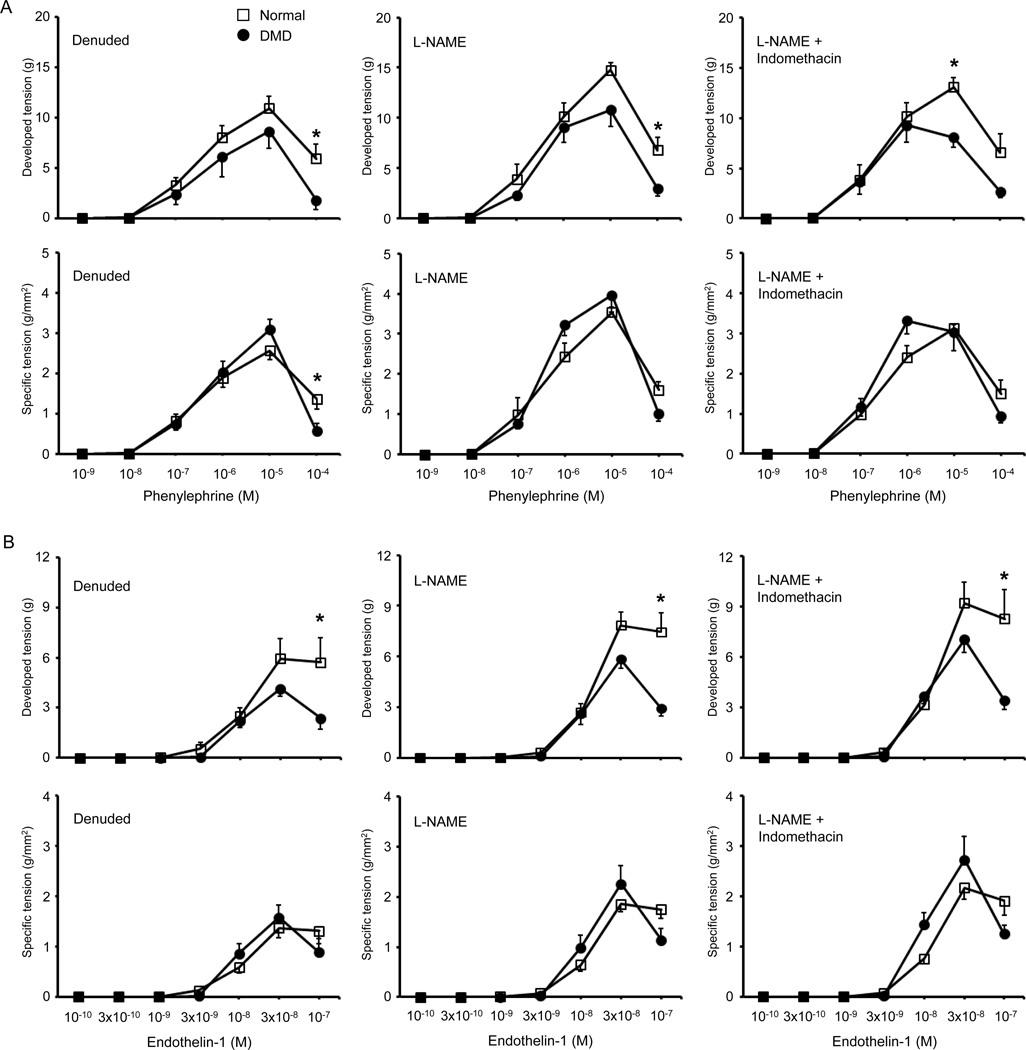

Vasoconstriction responses to phenylephrine and endothelin-1 were studied under four experimental conditions including intact, denuded, L-NAME treated, and combined L-NAME and indomethacin treated (Figures 4A–D, 5, Tables 2 and 3, supplementary material, Figure S7 and S8). Vasoconstriction became detectable at the phenylephrine concentration of 10−7 M. At 10−6 M, normal and DMD dog arteries showed similar developed and specific tensions. Peak tension was achieved at 10−5 M in both normal and DMD dogs under almost all conditions (Figure 4A,B, Figure 5A, supplementary material, Figure S7). The only exception was in DMD dogs treated with both L-NAME and indomethacin. Here, the peak developed and specific tensions were shifted to 10−6 M (Figure 5A, supplementary material, Figure S7C,D). The phenylephrine concentration that induced the half-maximal response (EC50) was calculated according to the derivation of the best-fit line. No significant difference was observed in EC50 between normal and DMD dogs (Table 2). At the phenylephrine concentrations of 10−5 M and 10−4 M, normal dogs consistently yielded a higher developed tension (Figure 4A, Figure 5A). However, statistical significance was reached only at the phenylephrine concentration of 10−5 M in intact and L-NAME/indomethacin treated arteries, and at the phenylephrine concentration of 10−4 M in denuded and L-NAME treated arteries (Figure 4A, Figure 5A, Table 2). When the developed tension was normalized against the area of the artery ring, normal and DMD dogs showed no statistically significant difference except at the phenylephrine concentration of 10−4 M in denuded femoral arteries (Figure 4B, Figure 5A, Table 2).

Figure 4. Dystrophin deficiency altered vasoconstriction and vasodilation responses in the intact dog femoral artery ring.

Vasoconstriction was evaluated by the developed and specific tension following stimulation with different doses of phenylephrine or endothelin-1. Vasodilation was evaluated by the percentage of vasorelaxation following stimulation with different doses of acetylcholine or sodium nitroprusside. (A) Quantification of the developed tension induced by different doses of phenylephrine. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=15 normal and n=16 DMD dog artery rings. (B) Quantification of the specific tension induced by different doses of phenylephrine. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=15 normal and n=16 DMD dog artery rings. (C) Quantification of the developed tension induced by different doses of endothelin-1. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=6 normal and n=6 DMD dog artery rings. (D) Quantification of the specific tension induced by different doses of endothelin-1. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=6 normal and n=6 DMD dog artery rings. (E) Quantification of the percentage of vasorelaxation induced by different doses of acetylcholine. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=15 normal and n=13 to 16 DMD dog artery rings. (F) Quantification of the percentage of vasorelaxation induced by different doses of sodium nitroprusside. Each data point shows the mean ± SEM of n=15 normal and n=14 to 16 DMD dog artery rings. Asterisk, significantly different between normal and DMD at the same drug concentration. Note, results shown in panels A, B, E and F are not identical to the results shown in the control groups in supplementary material, Figures S7, S9, and S10. This is due to sample size difference. Only a subset of dogs (6 normal and 6 DMD) samples used in Figure 4 underwent denudation, L-NAME treatment, and L-NAME/Indomethacin co-treatment. The control group data shown in supplementary material, Figure S7 are from the same dogs that were also evaluated under denuded, L-NAME treated, and L-NAME/Indomethacin co-treated conditions.

Figure 5. Impact of endothelial removal, L-NAME treatment, and combined L-NAME/indomethacin treatment on phenylephrine-induced or endothelin-1 induced vasoconstriction in normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings.

(A) Phenylephrine-induced developed tension (top panels) and specific tension (bottom panels) of the femoral artery rings after mechanical removal of the endothelium (denuded, left panels), in the presence of L-NAME (middle panels), and in the presence of both L-NAME and indomethacin (right panels). (B) Endothelin-1 induced developed tension (top panels) and specific tension (bottom panels) of the femoral artery rings after mechanical removal of the endothelium (denuded, left panels), in the presence of L-NAME (middle panels), and in the presence of both L-NAME and indomethacin (right panels). n = 6 for both normal and DMD. Asterisk, significantly different between normal and DMD at the same concentration of the vasoconstrictor (phenylephrine or endothelin-1).

Table 2.

Characterization of phenylephrine (PE) induced vasoconstriction

| Normal | DMD | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (normal=15, DMD=16) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 15.6 ± 1.46 | 10.71 ± 1.05* |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 3.29 ± 0.32 | 3.21 ± 0.42 |

| Tension at the maximum PE concentration, g | 6.09 ± 0.83 | 4.03 ± 0.99 |

| Specific tension at the maximum PE concentration, g/mm2 | 1.29 ± 0.17 | 0.94 ± 0.13 |

| EC50, Log M | −5.85 ± 0.12 | −5.68 ± 0.19 |

| Denuded (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 10.92 ± 1.24 | 8.65 ± 1.71 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 2.56 ± 0.22 | 3.09 ± 0.26 |

| Tension at the maximum PE concentration, g | 5.91 ± 1.46 | 1.80 ± 0.96* |

| Specific tension at the maximum PE concentration, g/mm2 | 1.36 ± 0.25 | 0.56 ± 0.20* |

| EC50, Log M | −6.44 ± 0.24α | −5.78 ± 0.50 |

| L-NAME ((normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 14.75 ± 0.74 | 10.79 ± 1.66 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 3.54 ± 0.13 | 3.96 ± 0.41 |

| Tension at the maximum PE concentration, g | 6.80 ± 1.22 | 2.97 ± 0.72* |

| Specific tension at the maximum PE concentration, g/mm2 | 1.60 ± 0.21 | 1.01 ± 0.19 |

| EC50, Log M | −6.46 ± 0.22 | −6.10 ± 0.42 |

| L-NAME + Indomethacin (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 13.1 ± 0.96 | 9.27 ± 1.67 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 3.13 ± 0.09 | 3.31 ± 0.33 |

| Tension at the maximum PE concentration, g | 6.58 ± 1.88 | 2.69 ± 0.63 |

| Specific tension at the maximum PE concentration, g/mm2 | 1.50 ± 0.34 | 0.93 ± 0.16 |

| EC50, Log M | −6.69 ± 0.19α | −6.89 ± 0.09α |

Mean ± SEM

EC50, Half-maximal effective concentration.

L-NAME, Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

Significantly different from the normal group in the same row.

Significantly different from the control in the same column.

Table 3.

Characterization of endothelin-1 (ET-1) induced vasoconstriction

| Normal | DMD | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 7.14 ± 0.71 | 5.69 ± 0.47 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 1.70 ± 0.15 | 2.17 ± 0.25 |

| Tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g | 6.98 ± 1.05 | 2.89 ± 0.66* |

| Specific tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g/mm2 | 1.64 ± 0.18 | 1.09 ± 0.29 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.98 ± 0.06 | −7.85 ± 0.18 |

| Denuded (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 5.93 ± 1.18 | 4.15 ± 0.44α |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 1.37 ± 0.20α | 1.58 ± 0.25 |

| Tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g | 5.71 ± 1.45 | 2.37 ± 0.63 |

| Specific tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g/mm2 | 1.31 ± 0.25 | 0.89 ± 0.26 |

| EC50, Log M | −8.02 ± 0.08 | −7.96 ± 0.12 |

| L-NAME (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 7.85 ± 0.80 | 5.83 ± 0.53 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 1.86 ± 0.16 | 2.26 ± 0.36 |

| Tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g | 7.46 ± 1.10 | 2.94 ± 0.47* |

| Specific tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g/mm2 | 1.75 ± 0.18 | 1.14 ± 0.23 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.98 ± 0.07 | −7.81 ± 0.18 |

| L-NAME + Indomethacin (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum tension, g | 9.21 ± 1.24 | 7.06 ± 0.77 |

| Maximum specific tension, g/mm2 | 2.17 ± 0.22 | 2.73 ± 0.47 |

| Tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g | 8.27 ± 1.76 | 3.42 ± 0.53* |

| Specific tension at the maximum ET-1 concentration, g/mm2 | 1.91 ± 0.29 | 1.25 ± 0.18 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.97 ± 0.05 | −7.87 ± 0.13 |

Mean ± SEM

EC50, Half-maximal effective concentration

L-NAME, Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

Significantly different from the normal group in the same row.

Significantly different from the L-NAME/Indomethacin group in the same column.

Vasoconstriction became detectable at the endothelin-1 concentration of 3 × 10−9 M and reached the peak at the endothelin-1 concentration of 3 × 10−8 M in both normal and DMD dogs under all experimental conditions (Figure 4C,D, Figure 5B, supplementary material, Figure S8). DMD dogs showed a lower maximal developed tension but a higher maximal specific tension (Figure 4C,D, Table 3). However, these differences did not reach statistical significance. No significant difference was detected in EC50 between normal and DMD dogs (Table 3). As the endothelin-1 concentration was increased from 3 × 10−8 M to 1 × 10−7 M, the developed and specific tension remained stable in normal arteries. Interestingly, the developed and specific tension went down in DMD dog arteries (Figure 4C,D, Figure 5B, supplementary material, Figure S8). At the endothelin-1 concentration of 1 × 10−7 M, the developed tension in DMD arteries became significantly lower than that of normal arteries in control, L-NAME treated, and L-NAME/Indomethacin treated conditions (Figure 4C and Figure 5B, Table 3). In both normal and DMD dogs, removal of the endothelium dampened endothelin-1 induced vasoconstriction while combined L-NAME/indomethacin treatment enhanced endothelin-1 induced vasoconstriction (Table 3, supplementary material, Figure S8).

Absence of dystrophin significantly impaired acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation.

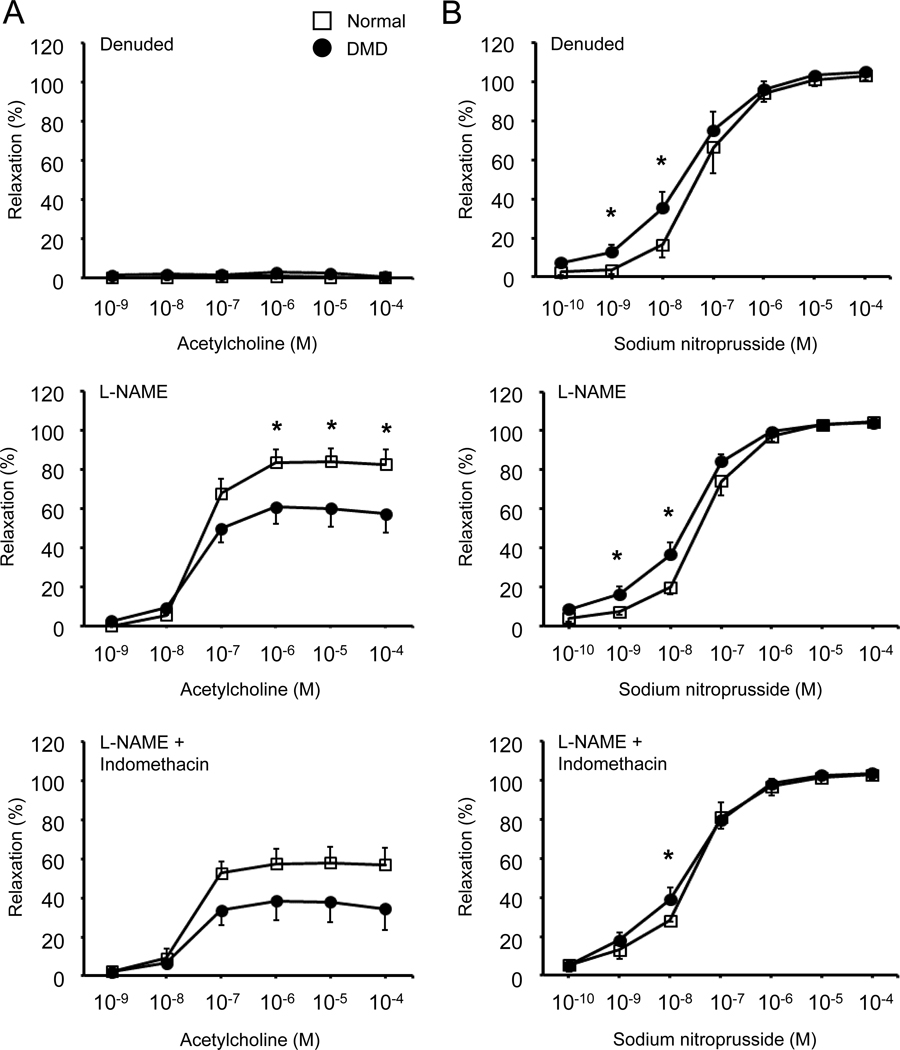

To study endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation, we first treated the femoral artery ring with 10−6 M phenylephrine to induce vasoconstriction. We then evaluated the vasodilation response to cumulative addition of acetylcholine under intact, denuded, L-NAME treated, and L-NAME/indomethacin co-treated conditions (Figure 4E, Figure 6A, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9). Acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation was detected at the acetylcholine concentration of 10−8 M and reached the plateau at the acetylcholine concentration of 10−6 M in both normal and DMD dog arteries in the intact, L-NAME, and L-NAME/indomethacin treated femoral arteries (Figure 4E, Figure 6A, supplementary material, Figure S9). Acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation was completely lost in the denuded femoral artery (Figure 6A, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9). In both normal and DMD dog arteries, L-NAME treatment reduced acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation (Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9). Addition of indomethacin resulted in further reduction of acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation (Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9).

Figure 6. Impact of endothelial removal, L-NAME treatment, and combined L-NAME/indomethacin treatment on acetylcholine-induced or sodium nitroprusside-induced vasorelaxation in normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings.

(A) Acetylcholine-induced (left panels) relaxation of the femoral artery rings after mechanical removal of the endothelium (denuded, top panel), in the presence of L-NAME (middle panel), and in the presence of both L-NAME and indomethacin (bottom panel). (B) Sodium nitroprusside-induced (right panels) relaxation of the femoral artery rings after mechanical removal of the endothelium (denuded, top panel), in the presence of L-NAME (middle panel), and in the presence of both L-NAME and indomethacin (bottom panel). n = 6 for both normal and DMD. Asterisk, significantly different between normal and DMD at the same concentration of the vasodilator (acetylcholine or sodium nitroprusside).

Table 4.

Characterization of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside induced vasorelaxation

| Normal | DMD | |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholine | ||

| Control (normal=15, DMD=16) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 95.59 ± 3.75α | 75.84 ± 4.89* |

| EC50, Log M | −8.01 ± 0.06 | −7.69 ± 0.15 |

| Denuded (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 4.06 ± 2.99α | 2.59 ± 0.96^ |

| EC50, Log M | NA | NA |

| L-NAME (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 80.79 ± 3.39α | 57.84 ± 6.52* |

| EC50, Log M | −7.30 ± 0.07# | −7.51 ± 0.13 |

| L-NAME + Indomethacin (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 49.91 ± 5.66α | 35.02 ± 7.28# |

| EC50, Log M | −7.41 ± 0.10# | −7.67 ± 0.12 |

| Sodium nitroprusside | ||

| Control (normal=15, DMD=14 for maximum relaxation, DMD=16 for EC50) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 93.29 ± 2.49β | 102.28 ± 1.56* |

| EC50, Log M | −6.69 ± 0.09β | −7.28 ± 0.14* |

| Denuded (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 103.93 ± 2.28 | 105.18 ± 2.11 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.18 ± 0.11 | −7.46 ± 0.20 |

| L-NAME (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 104.73 ± 1.09 | 104.16 ± 1.07 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.27 ± 0.07 | −7.63 ± 0.10* |

| L-NAME + Indomethacin (normal=6, DMD=6) | ||

| Maximum relaxation, % | 103.57 ± 1.62 | 103.47 ± 1.31 |

| EC50, Log M | −7.45 ± 0.07 | −7.66 ± 0.20 |

Mean ± SEM

EC50, Half-maximal effective concentration

L-NAME, Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

Significantly different from the normal group in the same row.

For acetylcholine study, significantly different from other three groups in the same column.

For acetylcholine study, significantly different from the control group in the same column.

For acetylcholine study, significantly different from each other in the same column.

For sodium nitroprusside study, significantly different from other three groups in the same column.

In the intact arteries, the most striking difference between normal and DMD dogs was the significantly dampened response to acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation in DMD dog arteries throughout a broad range of acetylcholine concentrations (from 10−8 M to 10−4 M) (Figure 4E). The dampened response was also reflected by a significant reduction of the percent of maximum relaxation in DMD dog arteries (Table 4). In addition, statistically significant dampening was observed in DMD dog arteries at the acetylcholine concentration of 10−6 M to 10−4 M following L-NAME treatment (Figure 6A). Combined L-NAME/indomethacin treatment resulted in a similar trend but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 6A). The maximum relaxation was significantly reduced in DMD dog arteries following L-NAME treatment (Table 4). The maximum relaxation in DMD dog arteries was reduced compared to that of normal dog arteries following combined L-NAME/indomethacin treatment (Table 4). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

SNP-induced vasorelaxation was enhanced in the DMD dog femoral artery.

SNP is a potent NO donor and endothelium-independent vasodilator [43]. SNP-induced vasorelaxation became detectable at the SNP concentration of 10−9 M and reached the plateau at the SNP concentration of 10−5 M in both normal and DMD dog arteries (Figure 4F, Figure 6B, supplementary material, Figure S10). SNP resulted in more pronounced vasorelaxation in the DMD dog artery compared to that of the normal artery (Figure 4F). The difference was statistically significant at the SNP concentration between 10−8 M and 10−4 M (Figure 4F). Consistently, the percent of maximum relaxation and the absolute EC50 value were significantly increased in intact DMD dog arteries (Table 4).

Removal of the endothelium, treatment with L-NAME alone or both L-NAME and indomethacin resulted in a leftward shift of the response curve in normal dog arteries but did not alter the response in DMD dog arteries (supplementary material, Figure S10). As a result, the difference between normal dogs and DMD dogs was lost at higher SNP concentrations (≥ 10−7 M) in denuded, L-NAME treated, and combined L-NAME/indomethacin treated arteries (Figure 6B, Table 4). However, at the lower SNP concentrations (10−9 M and 10−8 M), SNP still induced more pronounced vasorelaxation in DMD dogs compared to that of normal dogs (Figure 4F, Figure 6B). The absolute EC50 values of DMD dogs were consistently higher than those of normal dogs in all experiment conditions, statistical significance was reached in control arteries and L-NAME treated arteries (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study we evaluated dystrophin expression, eNOS and nNOS expression, NOS activity, anatomical and histological properties, and vascular constriction/relaxation responses of the femoral artery in a large cohort of normal and DMD dogs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate structure and function of a muscular artery in normal and dystrophic canines. We found that nNOS was not expressed in the dog femoral artery, eNOS expression and NOS activity were greatly reduced in the DMD dog artery. Importantly, we found that dystrophin deficiency resulted in significant structural remodeling and functional deficiency in the dog femoral artery.

Consistent with what has been reported in mice [16–18], we found robust expression of full-length dystrophin in smooth muscle and endothelial cells in normal dog femoral arteries (Figure 1A,B, Figure 2A,D, supplementary material, Figure S4 and S5). As expected, dystrophin was completely absent in DMD dog arteries (Figure 1A,B, Figure 2A,B, supplementary material, Figure S4 and S5). Similarly, dystrophin expression in smooth muscle of the vena cava was lost in DMD dogs (supplementary material, Figure S4C). In contrast to dystrophin, eNOS was selectively expressed in endothelial cells only (Figure 1D, Figure 2A,B, supplementary material, Figure S5). Previous studies suggest that eNOS expression and NOS activity are reduced in the artery of murine and canine DMD models [18,19,44]. Similarly, we found the endothelial eNOS level was significantly decreased and NOS activity greatly diminished in the DMD dog femoral artery (Figure 1C,D, Figure 2A,B). Palladino et al reported that dystrophin formed a complex with eNOS in vascular endothelial cells, suggesting dystrophin may play a role in stabilizing eNOS expression in the endothelium [18]. The reduction of the eNOS level and NOS activity seen in DMD dog arteries in our studies were consistent with the hypothesis that the eNOS level is, at least in part, regulated by dystrophin in the endothelium.

We have previously demonstrated that dystrophin recruits nNOS to the sarcolemma in murine and canine skeletal muscle [8,11,45]. Loss of dystrophin led to reduced nNOS expression in skeletal muscle and functional ischemia. It is currently unclear whether dystrophin can also recruit nNOS to the endothelium and smooth muscle of the vessel. Loufrani et al stated that they detected nNOS expression in the carotid artery and mesenteric artery in normal mice by western blot but did not show data in the paper [17]. Dabire et al found nNOS expression in the dog coronary artery by western blot [44]. However, the authors did not validate the nNOS antibody used in the study. Using a nNOS antibody verified in canine skeletal muscle (Figure 1E) [11], we did not find nNOS expression in the dog femoral artery (Figure 1F, Figure 2D, supplementary material, Figure S5). Our results are in line with that of Sato et al in which the authors also failed to detect nNOS expression in the mouse arterioles using a skeletal muscle validated nNOS antibody [21]. Taken together, our data and that of Sato et al suggest that nNOS is not expressed in the artery.

Structural changes (such as muscle wasting, fibrosis, inflammation, and calcification) are salient features of dystrophin-deficient striated muscles. However, it has been controversial whether dystrophin deficiency alters vessel structure in mice [16,17,20–22]. Inconsistent results have been reported in the mdx mouse model of DMD from even the same laboratory for the same artery using the same age same sex mice [17,20]. To conclusively address this issue, we combined anatomical measurement and histological quantification (Figure 3, supplementary material, Figure S1). We found the femoral artery of the affected dog was significantly smaller and the artery wall thinner than that of normal dogs (Figure 3A). We further showed that wall thickness reduction was mainly due to the atrophy of the smooth muscle layer (Figure 3B). Detection of medial layer calcification provided additional support to structural remodeling (supplementary material, Figure S6) [46]. Vascular remodeling has been shown to occur in response to altered blood flow [47]. Specifically, increased blood flow can cause vessel enlargement (positive/outward remodeling), and reduced blood flow can lead to vessel reduction (negative/inward remodeling) [47]. Although we did not examine the femoral artery mean blood flow in this study, we previously reported a 50% reduction in the brachial artery mean blood flow in anesthetized DMD dogs, compared to that of normal dogs [11]. It is thus conceivable that chronically reduced arterial blood flow may have at least in part contributed to the structural changes in DMD dog vessels observed in our study.

A patient study suggests that the absence of dystrophin may impair vasoconstriction response [48]. To study vasoconstriction, we treated the femoral artery ring with two potent vasoconstrictors, phenylephrine and endothelin-1. Phenylephrine selectively binds the α1-adrenoceptor in smooth muscle to induce vessel contraction. The maximum developed tension of the DMD dog femoral artery was significantly reduced compared to that of the normal dog femoral artery (Figure 4A, Table 2). This is consistent with smooth muscle atrophy seen in morphometric analysis (Figure 3). The phenylephrine-induced specific tension (vessel area normalized tension) and the EC50 of phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction were not altered by the absence of dystrophin in mice [16,17,19]. Norepinephrine-induced specific tension was not compromised in the brachial artery of DMD dogs [11]. Consistent with these reports, we did not see a significant change of the specific tension and EC50 in the femoral artery of DMD dogs (Figures 4B, Table 2). Together these results suggest that vascular smooth muscle reactivity to adrenoceptor activation is likely not altered by the loss of dystrophin.

The overall trend of phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction was largely unaffected by the removal of the endothelium, inhibition of NOS by L-NAME, and combined inhibition of NOS and COX by L-NAME and indomethacin (Figure 5A, Table 2, supplementary material, Figure S7). Interestingly, combined administration of NOS inhibitor L-NAME and COX inhibitor indomethacin resulted in a leftward shift of the maximal developed tension and maximal specific tension in DMD dog arteries (Figure 5A, supplementary material, Figure S7C,D). In other words, when the synthesis of NO and prostaglandins was blocked, DMD dog arteries became more sensitive to phenylephrine, they now reached their peak tension at 10−6 M instead of 10−5 M. Future studies are needed to clarify the underlying mechanism(s) and physiological implication(s) of this intriguing DMD dog-specific peak tension shift.

Endothelin-1 is secreted by vascular endothelial cells. It mediates vasoconstrictive effect via ETA and ETB receptors located in vascular smooth muscle cells. Normal and DMD arteries showed similar EC50 and specific tensions (Figure 4D, Table 3). Developed tensions were also comparable between normal and DMD arteries at the endothelin-1 concentration of ≤ 1 × 10−8 M. However, when the endothelin-1 concentration reached 3 × 10−8 M and above, normal arteries developed a higher tension. The difference reached statistical significance at the concentration of 1 × 10−7 M (Figure 4C, Table 3). Removal of the endothelium, inhibition of NOS by L-NAME, and combined inhibition of NOS and COX by L-NAME and indomethacin did not alter the overall trend of endothelin-1induced vasoconstriction (Figure 5B, supplementary material, Figure S8). However, compared to that of the control arteries, the maximum developed tension appeared enhanced when both NOS and COX pathways were inhibited, but not when only NOS pathway was inhibited (Table 3, supplementary material, Figure S8). This suggests that endogenous prostaglandins may counteract endothelin-1induced vasoconstriction in canine arteries [49]. Blocking their production by indomethacin strengthens endothelin-1induced vasoconstriction (Table 3, supplementary material, Figure S8).

A striking drop of the tension was observed in DMD dog arteries at the endothelin-1 concentration of 1 × 10−7 M (Figures 4C,D, supplementary material, Figure S8C,D). We currently do not have an explanation for this paradoxical DMD dog specific tension drop. It has been shown that endothelin-1 can bind to the ETB receptor in endothelial cells to induce vasodilation through production of vasorelaxant NO and COX metabolites [50]. However, removing the endothelium, blocking the NOS pathway, or blocking both NOS and COX pathways had no impact on the tension drop in the DMD dog artery (Figure 5B, supplementary material, Figure S8C,D). Future studies are needed to understand these unexpected findings.

To accurately compare the vasorelaxation response between normal and DMD femoral arteries, we pre-treated the artery rings with 10−6 M phenylephrine. Under this condition, normal and DMD femoral arteries produced similar levels of the developed and specific tension (Figure 4A,B). The vasorelaxation response was then studied by treating pre-constricted femoral artery rings with either acetylcholine or SNP (Figure 4E,F, Figure 6, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9 and S10). Acetylcholine induces vasodilation mainly through the endothelial muscarinic receptors M3 and M5 [51]. Specifically, binding of acetylcholine to the muscarinic receptors activates eNOS and COX to produce NO and prostaglandins, respectively. NO and prostaglandins then elicit vasodilation through cGMP and cAMP production, respectively, in vascular smooth muscle [52]. SNP, on the other hand, is an exogenous NO donor. It induces vasodilation through endothelium-independent mechanisms.

Acetylcholine-induced vasodilation was significantly blunted in DMD dog arteries (Figure 4E, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9). This is in line with the observation that eNOS expression and NOS activity were reduced in DMD dog arteries (Figure 1C,D, Figure 2A,B). In other words, the endothelium of dystrophic dogs produces less NO, and therefore, less vasorelaxation when treated with the same amount of acetylcholine. Our findings support those of Dabire et al who also observed a significant reduction of acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation in the isolated coronary artery of affected dogs [44]. Complete absence of eNOS abolishes acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation [53–55]. eNOS expression and NOS activity are reduced in mdx mouse arteries [18,19]. Surprisingly, Loufrani et al found that acetylcholine-induced vasodilation was not compromised in mdx mice [16,17,20]. It is unclear why acetylcholine-induced vasodilation is preserved in mdx mice.

To better understand acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in canine arteries, we examined the vasorelaxation response in denuded artery rings as well as following NOS inhibition and NOS/COX co-inhibition (Figure 6A, Table 3, supplementary material, Figure S9). Removal of the endothelium (denudation) completely abolished acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation (Figure 6A, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9), suggesting that the endothelium was solely responsible for acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation. Treatment with NOS inhibitor L-NAME dampened vasorelaxation, and addition of COX inhibitor indomethacin further dampened vasorelaxation (Figure 6A, Table 3, supplementary material, Figure S9). Together, these data suggest that NO (produced by eNOS) and prostaglandins (synthesized by COX) are important mediators for acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in canine arteries.

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the blunted endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in DMD arteries, we compared the extent of inhibition on acetylcholine-induced vasodilation by L-NAME and L-NAME/Indomethacin (supplementary material, Table S4). Normal and DMD dog arteries were similarly impacted. There is no statistically significant difference between two groups (supplementary material, Table S4). Hence, the machinery responsible for acetylcholine-induced vasodilation remains intact in DMD dog arteries. Reduced eNOS expression is thus the primary factor, if not the only factor, causing the blunted vasodilation response in DMD dog arteries.

SNP is the other vasodilator evaluated in our studies. Unlike acetylcholine, SNP releases NO when it breaks down in circulation. NO can directly activate cGMP in vascular smooth muscle to induce vasorelaxation. Hence, SNP-induced vasodilation is not dependent on the endothelium. In sharp contrast to what we observed with acetylcholine-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation, SNP induced a significantly more potent vasodilation in DMD dog arteries than in normal dog arteries (Figure 4F, Table 4). There are several possible explanations including (1) increased sensitivity to exogenous NO in the vascular smooth muscle of DMD dogs, (2) decreased sensitivity to exogenous NO in the vascular smooth muscle of normal dogs, and (3) existence of inhibitory factor(s) in the normal dog artery that counteract exogenous NO induced vasodilation. To tease apart the underlying mechanism, we evaluated the SNP response in the absence of endothelium (denudation), following NOS pathway inhibition (with L-NAME), and following co-inhibition of both NOS and COX pathways (by L-NAME and indomethacin) (Figure 6B, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S10). None of these treatments altered the SNP response curve in DMD dog arteries (supplementary material, Figure S10B), suggesting the enhanced SNP response in DMD dog arteries is not dependent on endothelium, endogenous NO (generated by endothelial eNOS), or prostaglandins (synthesized by COX). Interestingly, removal of the endothelium or application of L-NAME significantly potentiated SNP-induced vasorelaxation in normal dog arteries (Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S10A). In fact, under the condition of denudation or NOS inhibition, the normal dog response curve became indistinguishable from the DMD dog response curve at the SNP concentration from 10−7 M to 10−4 M (Figure 6B). This suggests that the endothelium, more specifically endothelial eNOS, is responsible for the blunted SNP response in normal dog arteries. On the other hand, addition of COX pathway blockade by indomethacin did not further enhance L-NAME induced potentiation of SNP vasorelaxation in normal dog arteries, suggesting endothelial prostaglandins are likely not important. In summary, under basal conditions, the normal artery is always exposed to NO (due to basal NO release from eNOS and flow-induced NO release). This endogenous NO desensitizes the normal artery to NO. In the DMD artery, basal NO release and flow-induced NO release are chronically reduced. This makes the smooth muscle of the DMD artery more sensitive to NO.

In our study on acetylcholine-induced vasodilation, we showed that eNOS expression facilitated vasorelaxation in normal dog arteries and eNOS reduction was responsible for the dampened vasorelaxation response in DMD dog arteries (Figure 4E, Figure 6A, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S9). However, in our study on SNP-induced vasodilation, we found that eNOS expression compromised vasorelaxation in normal dog arteries while eNOS reduction underlay enhanced vasorelaxation in DMD dog arteries (Figure 4F, Figure 6B, Table 4, supplementary material, Figure S10). These seemingly counterintuitive results suggest that NO-mediated vasodilation is complex and context-dependent. In fact, endogenous NO produced by eNOS not only mediates acetylcholine-induced basal vasodilation but also desensitizes soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) to NO activation by exogenous NO donor [56]. On the other hand, chronic lack of endothelium-derived NO compromises acetylcholine-induced basal vasodilation. Deficiency in basal acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation sensitizes soluble guanylyl cyclase to exogenous nitrovasodilators [56]. Our results align perfectly with what has been reported in normal animals and eNOS knockout mice [53–60].

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that (i) full-length dystrophin is expressed in the endothelium and smooth muscle of the muscular artery in canines, (ii) dystrophin deficiency down-regulates endothelial eNOS in the dog artery, and (iii) the absence of dystrophin compromises the structure and function of the muscular artery in the canine DMD model. These results suggest that vascular defects may represent an important aspect of DMD pathology in large mammals. Restoration of vascular dystrophin expression should be considered in DMD gene therapy.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Markers used in morphometric quantification

Figure S2. Equipment setup for studying canine femoral artery function

Figure S3. Quantitative evaluation of basic physiological properties of the femoral arterial rings from normal and DMD dogs

Figure S4. Photomicrographs of staining patterns in normal and affected DMD dog vessels

Figure S5. Western blot evaluation of dystrophin, utrophin, eNOS and nNOS expression in the endothelial and smooth muscle fraction of the normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings

Figure S6. Characterization of fibrosis, calcification, inflammation, and T-cell infiltration in normal and DMD dog femoral arteries

Figure S7. Vasoconstriction responses to phenylephrine in intact, denuded, L-NAME, and L-NAME/indomethacin treated normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings

Figure S8. Vasoconstriction responses to endothelin-1 in intact, denuded, L-NAME, and L-NAME/indomethacin treated normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings

Figure S9. Vasorelaxation responses to acetylcholine in intact, denuded, L-NAME, and L-NAME/indomethacin treated normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings.

Figure S10. Vasorelaxation responses to sodium nitroprusside in intact, denuded, L-NAME, and L-NAME/indomethacin treated normal and DMD dog femoral artery rings

Table S1. Sample size

Table S2. Concentrations of stock solutions

Table S3. Composition of the buffers used in physiological assays

Table S4. Impact of NOS inhibition and NOS/COX co-inhibition on acetylcholine-induced vasodilation

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Duan lab for helpful discussion. We thank Dr. Nalinda Wasala for the help with statistical analysis. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NS-90634 (DD), AR-70517 (DD), Jackson Freel DMD Research Fund (DD), and Jesse’s Journey: The Foundation for Gene and Cell Therapy (DD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: DD is a member of the scientific advisory board for Solid Biosciences and an equity holder of Solid Biosciences. DD is an inventor on a patent licensed to Solid Biosciences. The Duan lab has received research support from Solid Biosciences and Edgewise Therapeutics unrelated to this project in past three years. No other conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available to qualified investigators upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Kunkel LM. 2004 William Allan award address. cloning of the DMD gene. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophin. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021; 7: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig M, Hoffman EP, Bertelson CJ, et al. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell 1987; 50: 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Jr., Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 1987; 51: 919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenichel GM. On the pathogenesis of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1975; 17: 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrof BJ. Molecular pathophysiology of myofiber injury in deficiencies of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 81: S162–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas GD. Functional muscle ischemia in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Frontiers in physiology 2013; 4: 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai Y, Thomas GD, Yue Y, et al. Dystrophins carrying spectrin-like repeats 16 and 17 anchor nNOS to the sarcolemma and enhance exercise performance in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai Y, Zhao J, Yue Y, et al. alpha2 and alpha3 helices of dystrophin R16 and R17 frame a microdomain in the alpha1 helix of dystrophin R17 for neuronal NOS binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110: 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas GD, Sander M, Lau KS, et al. Impaired metabolic modulation of alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 15090–15095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodippili K, Hakim CH, Yang HT, et al. Nitric oxide dependent attenuation of norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction is impaired in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Physiol 2018; 596: 5199–5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Latroche C, Matot B, Martins-Bach A, et al. Structural and Functional Alterations of Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature in Dystrophin-Deficient mdx Mice. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 2482–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma M, Asakura Y, Hirai H, et al. Flt-1 haploinsufficiency ameliorates muscular dystrophy phenotype by developmentally increased vasculature in mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19: 4145–4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma M, Shimizu-Motohashi Y, Asakura Y, et al. Inhibition of FLT1 ameliorates muscular dystrophy phenotype by increased vasculature in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS Genet 2019; 15: e1008468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsakas A, Yadav V, Lorca S, et al. Muscle ERRgamma mitigates Duchenne muscular dystrophy via metabolic and angiogenic reprogramming. FASEB J 2013; 27: 4004–4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loufrani L, Matrougui K, Gorny D, et al. Flow (shear stress)-induced endothelium-dependent dilation is altered in mice lacking the gene encoding for dystrophin. Circulation 2001; 103: 864–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loufrani L, Dubroca C, You D, et al. Absence of dystrophin in mice reduces NO-dependent vascular function and vascular density: total recovery after a treatment with the aminoglycoside gentamicin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24: 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palladino M, Gatto I, Neri V, et al. Angiogenic impairment of the vascular endothelium: a novel mechanism and potential therapeutic target in muscular dystrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33: 2867–2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loufrani L, Levy BI, Henrion D. Defect in microvascular adaptation to chronic changes in blood flow in mice lacking the gene encoding for dystrophin. Circ Res 2002; 91: 1183–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loufrani L, Henrion D. Vasodilator treatment with hydralazine increases blood flow in mdx mice resistance arteries without vascular wall remodelling or endothelium function improvement. J Hypertens 2005; 23: 1855–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato K, Yokota T, Ichioka S, et al. Vasodilation of intramuscular arterioles under shear stress in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle is impaired through decreased nNOS expression. Acta Myol 2008; 27: 30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagher P, Duan D, Segal SS. Evidence for impaired neurovascular transmission in a murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of applied physiology 2011; 110: 601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito K, Kimura S, Ozasa S, et al. Smooth muscle-specific dystrophin expression improves aberrant vasoregulation in mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet 2006; 15: 2266–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan D. Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy: lost in translation? Res Rep Biol 2011; 2: 31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan D. Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy in the canine model. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2015; 26: 57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGreevy JW, Hakim CH, McIntosh MA, et al. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Dis Model Mech 2015; 8: 195–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris GE, Man NT, Sewry CA. Monitoring Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy with epitope-specific monoclonal antibodies. Methods Mol Biol 2011; 709: 39–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fine DM, Shin J-H, Yue Y, et al. Age-matched comparison reveals early electrocardiography and echocardiography changes in dystrophin-deficient dogs. Neuromuscul Disord 2011; 21: 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith BF, Yue Y, Woods PR, et al. An intronic LINE-1 element insertion in the dystrophin gene aborts dystrophin expression and results in Duchenne-like muscular dystrophy in the corgi breed. Lab Invest 2011; 91: 216–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin J-H, Pan X, Hakim CH, et al. Microdystrophin ameliorates muscular dystrophy in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther 2013; 21: 750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue Y, Pan X, Hakim CH, et al. Safe and bodywide muscle transduction in young adult Duchenne muscular dystrophy dogs with adeno-associated virus. Hum Mol Genet 2015; 24: 5880–5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kodippili K, Hakim CH, Pan X, et al. Dual AAV gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy with a 7-kb mini-dystrophin gene in the canine model. Hum Gene Ther 2018; 29: 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin J-H, Greer B, Hakim CH, et al. Quantitative phenotyping of Duchenne muscular dystrophy dogs by comprehensive gait analysis and overnight activity monitoring. PLoS One 2013; 8: e59875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang HT, Shin J-H, Hakim CH, et al. Dystrophin deficiency compromises force production of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e44438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakim CH, Peters AA, Feng F, et al. Night activity reduction is a signature physiological biomarker for Duchenne muscular dystroophy dogs. J Neuromuscul Dis 2015; 2: 397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakim CH, Mijailovic A, Lessa TB, et al. Non-invasive evaluation of muscle disease in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy by electrical impedance myography. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0173557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasala NB, Bostick B, Yue Y, et al. Exclusive skeletal muscle correction does not modulate dystrophic heart disease in the aged mdx model of Duchenne cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet 2013; 22: 2634–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakim CH, Wasala NB, Pan X, et al. A five-repeat micro-dystrophin gene ameliorated dystrophic phenotype in the severe DBA/2J-mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Molecular therapy Methods & clinical development 2017; 6: 216–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai Y, Zhao J, Yue Y, et al. Partial restoration of cardiac function with ΔPDZ nNOS in aged mdx model of Duchenne cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet 2014; 23: 3189–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodippili K, Vince L, Shin JH, et al. Characterization of 65 epitope-specific dystrophin monoclonal antibodies in canine and murine models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy by immunostaining and western blot. PLoS One 2014; 9: e88280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newcomer SC, Taylor JC, Bowles DK, et al. Endothelium-dependent and -independent relaxation in the forelimb and hindlimb vasculatures of swine. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2007; 148: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bunker AK, Arce-Esquivel AA, Rector RS, et al. Physical activity maintains aortic endothelium-dependent relaxation in the obese type 2 diabetic OLETF rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010; 298: H1889–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holme MR, Sharman T. Sodium Nitroprusside. In: StatPearls.: Treasure Island (FL), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dabire H, Barthelemy I, Blanchard-Gutton N, et al. Vascular endothelial dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy is restored by bradykinin through upregulation of eNOS and nNOS. Basic Research in Cardiology 2012; 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li D, Yue Y, Lai Y, et al. Nitrosative stress elicited by nNOSmu delocalization inhibits muscle force in dystrophin-null mice. J Pathol 2011; 223: 88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.London GM. Arterial calcification: cardiovascular function and clinical outcome. Nefrologia 2011; 31: 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward MR, Pasterkamp G, Yeung AC, et al. Arterial remodeling. Mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation 2000; 102: 1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noordeen MH, Haddad FS, Muntoni F, et al. Blood loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: vascular smooth muscle dysfunction? J Pediatr Orthop B 1999; 8: 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baretella O, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-Dependent Contractions: Prostacyclin and Endothelin-1, Partners in Crime? Adv Pharmacol 2016; 77: 177–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider MP, Boesen EI, Pollock DM. Contrasting actions of endothelin ET(A) and ET(B) receptors in cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007; 47: 731–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harvey RD. Muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists: effects on cardiovascular function. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012: 299–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellogg DL Jr., Zhao JL, Coey U, et al. Acetylcholine-induced vasodilation is mediated by nitric oxide and prostaglandins in human skin. Journal of applied physiology 2005; 98: 629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldron GJ, Ding H, Lovren F, et al. Acetylcholine-induced relaxation of peripheral arteries isolated from mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol 1999; 128: 653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chataigneau T, Feletou M, Huang PL, et al. Acetylcholine-induced relaxation in blood vessels from endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. Br J Pharmacol 1999; 126: 219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, et al. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature 1995; 377: 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moncada S, Rees DD, Schulz R, et al. Development and mechanism of a specific supersensitivity to nitrovasodilators after inhibition of vascular nitric oxide synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88: 2166–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shirasaki Y, Su C. Endothelium removal augments vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside and sodium nitrite. Eur J Pharmacol 1985; 114: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luscher TF, Richard V, Yang ZH. Interaction between endothelium-derived nitric oxide and SIN-1 in human and porcine blood vessels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1989; 14 Suppl 11: S76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nangle MR, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. An in vitro investigation of aorta and corpus cavernosum from eNOS and nNOS gene-deficient mice. Pflugers Arch 2004; 448: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brandes RP, Kim D, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, et al. Increased nitrovasodilator sensitivity in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice: role of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Hypertension 2000; 35: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Markers used in morphometric quantification

Figure S2. Equipment setup for studying canine femoral artery function

Figure S3. Quantitative evaluation of basic physiological properties of the femoral arterial rings from normal and DMD dogs

Figure S4. Photomicrographs of staining patterns in normal and affected DMD dog vessels