Abstract

We have recently shown that 14α-demethylation-deficient cells of Candida albicans are subject to growth arrest by 0.24 M acetate in a yeast extract-peptone-glucose medium and that the minimum concentration of an azole antifungal agent required for total inhibition of sterol 14α-demethylation (MDIC for minimum demethylation-inhibitory concentration) is practically identical to its MIC determined in the acetate-supplemented medium (O. Shimokawa and H. Nakayama, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:100–105, 1999). In the present study we estimated the MDICs of three different azoles (fluconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole) for strains of various Candida species using this method and compared them with the MICs determined in the corresponding acetate-free medium. The results demonstrated that the test strains were divided into two classes. One class of strains was characterized by tolerance to 14α-demethylation deficiency (MIC > MDIC) and consisted of strains of C. albicans, C. guilliermondii, C. kefyr, and C. tropicalis. The other class was intolerant to 14α-demethylation deficiency (MIC ≈ MDIC) and comprised strains of C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. parapsilosis. We also showed that replacement of the yeast extract-peptone-glucose medium with RPMI 1640 medium did not affect the results substantially. Furthermore, the 80% inhibitory concentration (IC80) in RPMI 1640 medium, recommended as a substitute for the conventional MIC in susceptibility testing, was found to be close to the MDIC.

Azole antifungal agents inhibit sterol 14α-demethylation (referred to as 14-dMe) in ergosterol biosynthesis, thus causing the accumulation of 14α-methylated sterols in the fungal membranes. Notably, however, the effect of 14-dMe inhibition on cell growth is not simple. While cells of some fungi cannot grow in the presence of 14-dMe deficiency (i.e., they are intolerant to 14-dMe deficiency), those of other fungi can (i.e., they are tolerant to 14-dMe deficiency). Thus far, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been thought to belong to the former class (3), whereas Candida albicans has been thought to belong to the latter class (2, 3, 7, 9, 10). On the other hand, it is generally assumed that 14-dMe inhibition constitutes the basis of the therapeutic efficacies of azole antifungal agents. In effect, there is evidence that C. albicans cells grown under conditions of 14-dMe deficiency show increased susceptibility to the fungicidal mechanisms of phagocytes (8, 11), suggesting that the clinical efficacies of this class of drugs are brought about by cooperation of 14-dMe inhibition and host defense mechanisms.

In fungi intolerant to 14-dMe deficiency, the minimum concentration of an azole drug required for a complete inhibition of 14-dMe (MDIC [12] for minimum demethylation-inhibitory concentration) is expected to be equal or at least close to its MIC. However, for fungi tolerant to 14-dMe deficiency, for which the MDIC is lower than the MIC by definition, the MIC gives no information about the MDIC, which should be important in clinical settings. Previously, we have described a simple method for estimation of the MDIC of an azole for C. albicans (12). That method uses growth inhibition by acetate in 14-dMe-deficient cells and determines the MIC in an acetate-containing yeast extract-peptone-glucose (YEPG) medium. In the present study, we found, by using this method, that some species of the genus Candida were tolerant to 14-dMe deficiency, like C. albicans, while others were not. Furthermore, we also showed that measurement of the 80% inhibitory concentration (IC80) in a special medium, now widely used as a routine medium for azole susceptibility testing, gave results fairly close to the MDIC estimate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

The fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Candida strains used in the study

| Species and strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | ||

| KD14 | Serotype A; Lys− but otherwise wild type | 9 |

| ATCC 10231 | Serotype A; wild type | From R. D. Cannon |

| ATCC 10261 | Serotype A; wild type | From R. D. Cannon |

| CAI4 | Serotype A; Ura− but otherwise wild type | 4 |

| B59630 | Serotype A; Cdr1-overexpressing clinical isolate | From F. C. Odds; 1, 6 |

| MEN | Serotype B; wild type | 14 |

| C. glabrata CBS138 | Wild type | From R. D. Cannon |

| C. guilliermondii IFO0454 | Wild type | From M. Niimi |

| C. krusei | ||

| B2399 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| IFO0011 | Wild type | From R. D. Cannon |

| C. parapsilosis | ||

| 90111 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| 90454 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| MCC499 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| C. kefyr B2455 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| C. tropicalis 820567 | Clinical isolate | From R. D. Cannon |

| S. cerevisiae YPH499 | MATa Ade− Leu− Trp− Ura− Lys− His− | 13 |

Culture media.

YEPG medium and acetate (0.24 M)-supplemented YEPG (YEPG-Ac) medium were described previously (12). YEPG and YEPG-Ac were solidified with 2% (wt/vol) agar to give YEPG agar and YEPG-Ac agar, respectively. The RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI) was as described previously (5), and it was supplemented with 0.24 M sodium acetate to give RPMI-Ac. Azole drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and were added to sterile media, with the final concentration of the solvent being adjusted to 1% (vol/vol).

Agar plate assays of azole susceptibility.

Assays with YEPG or YEPG-Ac agar plates containing a concentration gradient of an azole were done as described previously (12).

MIC measurement and estimation of MDIC by dilution assay.

A test cell suspension (107 CFU/ml) was prepared by washing and suspending in distilled water cells grown in YEPG at 35°C overnight with shaking. The conventional MIC of an azole was measured as follows. Twofold dilutions (0.1 ml each) of the test drug made in YEPG or RPMI were mixed in plastic microplate wells with 0.1-ml aliquots of a 100-fold dilution of the cell suspension made in the same medium (containing 104 CFU), and the plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 days without agitation. The lowest drug concentration that gave a visibly clear culture was taken to represent the MIC. It should be noted that the MIC thus obtained is not equivalent to the IC80 (see below) determined by the routine standardized by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (5) even when RPMI is used. The MDIC of an azole was estimated by measuring the MIC in YEPG-Ac or RPMI-Ac (signified by MICAc) in a way similar to that described above.

Determination of IC80 of the azole.

Determination of the IC80 of the azole was carried out in RPMI by the method standardized by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (5). Thus, dilution assays were done with RPMI as described above, and the drug concentration that caused 80% growth inhibition was determined by turbidimetry, followed by interpolation when appropriate.

Sterol analysis.

Extraction of cellular lipids and thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates (Merck) were carried out as described previously (9). Identification of sterols was achieved by comparing the Rfs with the reference values obtained in our previous work (9).

Chemicals.

Fluconazole (FLCZ) was donated by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (Tokyo, Japan); ketoconazole (KCZ) and itraconazole (ITZ) were gifts from the Janssen Research Foundation (Beerse, Belgium).

RESULTS

Relationship between 14-dMe deficiency and acetate-mediated growth inhibition in Candida species.

We have previously shown that azole-treated C. albicans cells are subject to growth inhibition in YEPG-Ac and that the extent of this inhibition increases as the degree of 14-dMe (the level of cellular ergosterol) diminishes, finally becoming complete when the azole concentration is high enough to make the ergosterol undetectable (12). (In a previous study [12], some cell growth can be seen in YEPG-Ac even in the virtual absence of 14-dMe [Fig. 5A therein], giving the impression that the MICAc is higher than the MDIC. However, this is due to the high initial cell density (≈5 × 105 CFU/ml; A540 ≈ 0.04) needed for sterol analysis, combined with gradual growth cessation intrinsic to azole-treated cells [see Fig. 4A of reference 12]. In MIC assays, an initial cell density of ≈5 × 104 CFU/ml is used [see Materials and Methods], with which the residual growth alone barely yields visible turbidity. Hence, the MICAc roughly coincides with MDIC.) On the basis of these observations, we have proposed that the MDICs of azoles can be estimated by determining the MICAc, i.e., the MIC measured in YEPG-Ac (12).

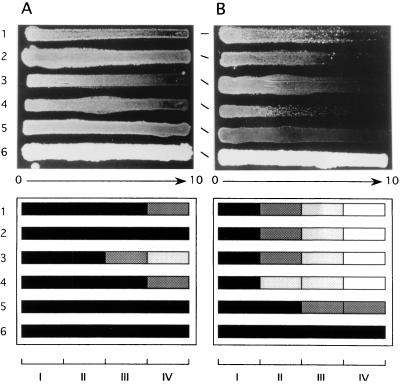

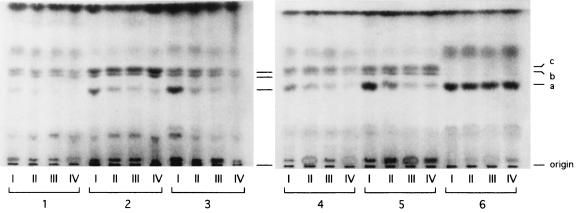

To probe the possibility of generalization of this finding, we subjected strains of different Candida species other than C. albicans to the same analysis used in the previous study (12). Briefly, cells were grown on YEPG agar along a concentration gradient of FLCZ, and the sterol profiles for cells from different parts of the gradient were monitored and were compared with the growth pattern on YEPG-Ac agar that contained the same gradient. The results obtained were consistent with the above-mentioned correlation previously demonstrated for C. albicans strains (Fig. 1 and 2). In essence, when growth on YEPG-Ac agar with an FLCZ gradient was diminished or undetectable, the ergosterol content of the cells from the corresponding position of YEPG agar with an FLCZ gradient was likewise diminished or undetectable. Judging from these findings, we considered that YEPG-Ac should be useful for estimation of the MDIC for Candida species other than C. albicans as well.

FIG. 1.

Growth of Candida strains on a concentration gradient of FLCZ. (A) YEPG agar; (B) YEPG-Ac agar. Top, photographic images; bottom, schematic representations with gradations depicting growth. FLCZ concentrations, 0 to 10 μg/ml from left to right (I to IV). Rows: 1, C. tropicalis 820567; 2, C. kefyr B2455; 3, C. parapsilosis MCC499; 4, C. guilliermondii IFO0454; 5, C. glabrata CBS138; 6, C. krusei B2399.

FIG. 2.

Thin-layer chromatography analysis of sterols from cells grown on a YEPG agar plate containing the FLCZ concentration gradient (plate A in Fig. 1). Lanes: 1, C. tropicalis 820567; 2, C. kefyr B2455; 3, C. parapsilosis MCC499; 4, C. guilliermondii IFO0454; 5, C. glabrata CBS138; 6, C. krusei B2399; I to IV, sampling zones (see Fig. 1). Identification of sterols: a, ergosterol; b, 4,14-methylated sterols; c, 4,4′,14-methylated sterols.

Relationship between MIC and MICAc (MDIC) of the azole.

On the basis of the results presented above, we went on to determine the MICAc and MIC using YEPG-Ac and YEPG, respectively, with three different azoles and a wider array of strains of the genus Candida (Table 2). A strain of S. cerevisiae was included as a reference. It has been reported that cells of S. cerevisiae are incapable of growth in the absence of 14-dMe (3). In accordance with this notion, the MICAc and MIC of each of the azoles used were shown to be identical for the test strain of this yeast. On the other hand, for all C. albicans strains except B59630 the MICAc was much lower than the MIC. Strain B59630 is an azole-resistant mutant (6) which overexpresses the drug efflux pump Cdr1 (1). While the MIC did not distinguish B59630 from the other C. albicans test strains, the MICAc did: compared with the other strains, the MICs of all three azoles for strain B59630 were elevated, with the increase being most marked with FLCZ. Notably, however, this strain was found to be similar to the others in terms of the relationship between the MICAc and the MIC: the MICAc and MIC were sharply different from each other for KCZ and ITZ, although they were fairly close to each other for FLCZ due to the marked increase in the MICAc. The test strains of C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. parapsilosis were similar to S. cerevisiae in this respect; differences between the MICAc and the MIC were absent or only slight, with the factor being not more than 2. The behaviors of the strains of C. guilliermondii, C. kefyr, and C. tropicalis were similar to those of the C. albicans strains, with the MICAc being lower than the MIC at least by an order of magnitude.

TABLE 2.

YEPG-based MICs and MICAcs of azoles for various Candida strainsa

| Species and strain | FLCZ

|

KCZ

|

ITZ

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) | MICAc (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MICAc (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MICAc (μg/ml) | |

| C. albicans | ||||||

| KD14 | >320 | 1.3 | 10 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.02 |

| ATCC 10231 | >320 | 1.3 | 10 | 0.005 | 10 | 0.01 |

| ATCC 10261 | >320 | 1.3 | 10 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.02 |

| CAI4 | >320 | 0.63 | NDb | ND | ND | ND |

| MEN | >320 | 1.3 | 10 | 0.005 | 10 | 0.01 |

| B59630 | >320 | 160 | 10 | 0.31 | 10 | 0.16 |

| C. glabrata CBS138 | 160 | 80 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 |

| C. guilliermondii IFO0454 | 160 | 1.3 | 5.0 | 0.005 | 10 | 0.01 |

| C. krusei | ||||||

| B2399 | 160 | 160 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 |

| IFO0011 | 160 | 160 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 |

| C. parapsilosis | ||||||

| 90111 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 90454 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| MCC499 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| C. kefyr B2455 | >320 | 5.0 | 10 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.02 |

| C. tropicalis 820567 | >320 | 5.0 | 10 | 0.005 | 10 | 0.02 |

| S. cerevisiae YPH499 | 80 | 80 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 10 | 10 |

The MICs were determined in YEPG, while the MICAcs were determined in YEPG-Ac. The MICAc is considered equivalent to the MDIC (see text).

ND, not determined.

Comparison of YEPG and RPMI.

As a routine of the clinical laboratory, azole susceptibility testing is done by measuring the IC80 in RPMI by the standard procedure (5). For this reason, we wanted to see what would happen if YEPG was replaced by RPMI in our assay. We found that the RPMI-based MICAc and MIC of FLCZ were similar, if not identical, to the YEPG-based counterparts (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of RPMI and YEPG as media for determination of inhibitory concentrations of FLCZa

| Species and strain | MIC (μg/ml) in RPMI (YEPG) | MICAc (μg/ml) in RPMI-Ac (YEPG-Ac) | IC80 (μg/ml) in RPMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | |||

| KD14 | >320 (>320) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| ATCC 10231 | 160 (>320) | 0.63 (1.3) | 0.32 |

| ATCC 10261 | >320 (>320) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| CAI4 | 80 (>320) | 0.32 (0.63) | 0.32 |

| MEN | 320 (>320) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| B59630 | 320 (>320) | 80 (160) | 80 |

| C. glabrata CBS138 | 80 (160) | 40 (80) | 20 |

| C. guilliermondii IFO0454 | 80 (160) | 0.63 (1.3) | 0.63 |

| C. krusei | |||

| B2399 | 80 (160) | 40 (160) | 40 |

| IFO0011 | 80 (160) | 40 (160) | 40 |

| C. parapsilosis | |||

| 90111 | 2.5 (2.5) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| 90454 | 2.5 (2.5) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| MCC499 | 2.5 (2.5) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 |

| C. kefyr B2455 | 320 (>320) | 2.5 (5.0) | 2.5 |

| C. tropicalis 820567 | 320 (>320) | 5.0 (5.0) | 2.5 |

The data for YEPG and YEPG-Ac are from Table 2.

Coincidence between IC80 and MICAc (MDIC).

We also compared the MICAc and the MIC with the IC80 and found that the IC80 was close to the MICAc, the estimated MDIC, for FLCZ (Table 3). It is this feature of IC80 that probably made possible the identification of the FLCZ-specific azole resistance in B59630 (6).

DISCUSSION

The utility of acetate-mediated growth inhibition for estimation of the MDICs of azoles has previously been demonstrated with strains of C. albicans (12). In the present study, it was extended to other Candida species (Fig. 1 and 2), which justified comparison of the MDIC, as estimated from the MICAc, and the MIC with a larger set of strains of the genus Candida (Table 2). We found that the test strains were clearly divided into two distinct classes irrespective of the azole used. For one class, the MDICs and MICs were practically identical, indicating that cells were intolerant to 14-dMe deficiency; for the other class, the MDICs were much lower than MICs, indicating that the cells were tolerant to 14-dMe deficiency. It is unclear whether the tolerance or intolerance to 14-dMe deficiency is a species-dependent phenotype. While C. albicans may possibly be homogeneous with respect to this trait, there is no reason to believe that other species may also be so. More strains must be tested before a conclusion can be drawn.

The dichotomy between tolerance and intolerance to 14-dMe deficiency has two practical aspects that are worth mentioning. First, it has nothing to do with the MICAc-based estimation of the MDIC, the information that should be needed for clinical purposes (8, 11), and hence will cause no problem in the use of MICAc as the key parameter in azole susceptibility testing. Second, the possibility exists that azoles might be clinically more effective against fungi intolerant to 14-dMe deficiency than those tolerant to 14-dMe deficiency. This is because fungal cells of the latter class are still capable of growth under 14-dMe-deficient conditions and their control within the human body is perhaps more dependent on the host's defense mechanisms.

The test results with RPMI are also of note. First, the MICAc (as well as the MIC) measured by use of RPMI and YEPG were practically equivalent. Since RPMI is nutritionally much poorer than YEPG for Candida yeasts, this finding seems to suggest that the choice of the basal medium is not of critical importance in the determination of the MICAc (and, hence, in the estimation of the MDIC). Second, the finding that the IC80 (RPMI-based) is in effect close to the MDIC should be significant because it gives some basis to the totally empirical parameter IC80. However, as a tool for estimation of the MDIC, the YEPG-based MICAc has the obvious advantage of being theoretically well based, simple to measure, accurate, and inexpensive.

The underlying mechanism(s) for the dichotomy with regard to the effect of 14-dMe deficiency on cell growth is an interesting question that remains to be answered. We consider the isolation of mutants with alterations in this trait to be the approach of choice. Studies along this line are under way in the authors' laboratory. Also worth study is the applicability of the present method to azole susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. This possibility is intriguing in view of the lack of a convenient procedure suitable for this purpose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. C. Odds of the Janssen Research Foundation and R. D. Cannon and M. Niimi, both of the University of Otago, for providing us with fungus strains. The gifts of azole drugs from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research Foundation are gratefully acknowledged. Thanks are also due to K. Sakai for general supportive services in the laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson G D, Niimi M, Cannon R D, Jenkinson H F. Multiple efflux mechanisms are involved in Candida albicans fluconazole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2835–2841. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bard M, Lees N D, Barbuch R J, Sanglard D. Characterization of a cytochrome P450 deficient mutant of Candida albicans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;147:794–800. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bard M, Lees N D, Turi T, Craft D, Cofrin L, Barbuch R, Koegel C, Loper J C. Sterol synthesis and viability of erg11 (cytochrome P450 lanosterol demethylase) mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Lipids. 1993;28:963–967. doi: 10.1007/BF02537115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast. Proposed standard M27-P. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odds F C. Antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp. by relative growth measurement at single concentrations of antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1727–1737. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce A M, Pierce H D, Unrau A M, Oehlschlager A. Lipid composition and polyene antibiotic resistance of Candida albicans mutants. Can J Biochem. 1978;56:135–142. doi: 10.1139/o78-023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigematsu M L, Uno J, Arai T. Correlative studies on in vivo and in vitro effectiveness of ketoconazole against Candida albicans infection. Jpn J Med Mycol. 1981;22:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimokawa O, Kato Y, Nakayama H. Accumulation of 14-methyl sterols and defective hyphal growth in Candida albicans. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:327–336. doi: 10.1080/02681218680000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimokawa O, Kato Y, Kawano K, Nakayama H. Accumulation of 14α-methylergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β,6α-diol in 14α-demethylation mutant of Candida albicans: genetic evidence for the involvement of 5-desaturase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1003:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimokawa O, Nakayama H. Increased sensitivity of Candida albicans cells accumulating 14α-methylated sterols to active oxygen: possible relevance to in vivo efficacies of azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1626–1629. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimokawa O, Nakayama H. Acetate-mediated growth inhibition in sterol 14α-demethylation-deficient cells of Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:100–105. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelan W L, Magee P T. Natural heterozygosity in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:896–903. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.896-903.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]