Significance

Reaction centers (RCs) are critical to photosynthetic energy conversion. RCs in all characterized photosynthetic organisms contain two symmetrically arranged branches of chromophores and enable light-induced electron transfer with high yield. We fine-tune the properties of a key bacterial RC symmetry-breaking tyrosine via its replacement with noncanonical tyrosine analogs and determine kinetic outcomes. Results are interpreted through energetic characterization made possible by resonance Stark spectroscopy. Analysis indicates this tyrosine modulates the mechanism of the initial light-induced electron transfer, affording an alternative functional pathway that maintains the RC’s robust electron transfer. Modern molecular biology, ultrafast spectroscopy, crystallography, and energetic characterization enable the mechanistic model we describe. Our results deepen understanding of RC function and may have implications for other photocatalysts and enzymes.

Keywords: reaction center, noncanonical amino acid, ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy, Stark spectroscopy, superexchange

Abstract

Photosynthetic reaction centers (RCs) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides were engineered to vary the electronic properties of a key tyrosine (M210) close to an essential electron transfer component via its replacement with site-specific, genetically encoded noncanonical amino acid tyrosine analogs. High fidelity of noncanonical amino acid incorporation was verified with mass spectrometry and X-ray crystallography and demonstrated that RC variants exhibit no significant structural alterations relative to wild type (WT). Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy indicates the excited primary electron donor, P*, decays via a ∼4-ps and a ∼20-ps population to produce the charge-separated state P+HA− in all variants. Global analysis indicates that in the ∼4-ps population, P+HA− forms through a two-step process, P*→ P+BA−→ P+HA−, while in the ∼20-ps population, it forms via a one-step P* → P+HA− superexchange mechanism. The percentage of the P* population that decays via the superexchange route varies from ∼25 to ∼45% among variants, while in WT, this percentage is ∼15%. Increases in the P* population that decays via superexchange correlate with increases in the free energy of the P+BA− intermediate caused by a given M210 tyrosine analog. This was experimentally estimated through resonance Stark spectroscopy, redox titrations, and near-infrared absorption measurements. As the most energetically perturbative variant, 3-nitrotyrosine at M210 creates an ∼110-meV increase in the free energy of P+BA− along with a dramatic diminution of the 1,030-nm transient absorption band indicative of P+BA– formation. Collectively, this work indicates the tyrosine at M210 tunes the mechanism of primary electron transfer in the RC.

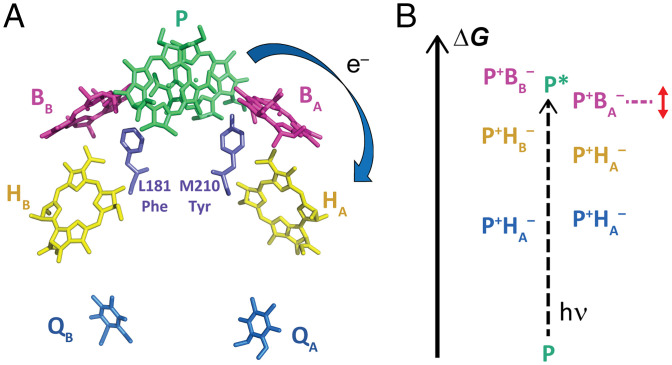

Photosynthetic reaction centers (RCs) are the integral membrane protein assemblies responsible for nearly all the solar energy conversion maintaining our biosphere. In this study, we focus on the initial electron transfer (ET) steps in bacterial RCs from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a three-subunit (H, L, and M) ∼100-kDa integral membrane protein complex. RCs in R. sphaeroides possess two branches of chromophores, the A and B (or L and M) branches (Fig. 1A), and each possesses nearly identical chromophore composition, orientation, and distances. The protein secondary structure is pseudo-C2 symmetric, and the symmetry-related amino acids that differ are often structurally similar (Fig. 1A) (1). Despite this high structural symmetry, ET proceeds rapidly down only the A branch of chromophores with near-unity quantum yield (2, 3). Additionally, RC ET is remarkably robust, as few structurally verified single mutations that maintain RC chromophore composition and positioning significantly impact ET kinetics or yield (1, 4–11).

Fig. 1.

RC chromophore arrangement and energetics. (A) Chromophore arrangement in WT RCs (PDB ID: 2J8C; accessory carotenoid, chromophore phytyl tails, and quinone isoprenoid tails are removed here for clarity). Tyr at M210, the target in this work, and its symmetry-related residue Phe at L181 are shown in purple. The blue arrow indicates unidirectionality of ET down the A branch. (B) Schematic free-energy diagram of different charge-separated states in WT RCs, where P* is 1.40 eV above ground state and P+HA– is 0.25 eV below P*. The dashed magenta line and double-headed arrow next to P+BA– indicates the expected major effect of ncAA incorporation at M210 on the free energy of this state.

To understand RC ET asymmetry or unidirectionality and factors underlying its robust nature, a thorough understanding of the mechanism of ET is required. In the model largely accepted in the current literature (1, 12–14), ET is initiated by excitation of the excitonically coupled bacteriochlorophyll pair P. The lowest singlet excited state P* transfers an electron to the bacteriochlorophyll BA with a time constant of ∼3 ps to form P+BA–. BA– subsequently transfers an electron to the bacteriopheophytin HA with a time constant of 1 ps, thus forming P+HA– in a two-step primary ET process, P* → P+BA– → P+HA– (1, 12, 13). An alternative model for ET has been proposed in which P* transfers an electron to HA directly through a superexchange mechanism, as defined by Parson et al. (1). Here, the BA chromophore mediates the electronic coupling between P* and HA, and experimental evidence for superexchange ET must be inferred spectroscopically from the absence of P+BA– formation during transient absorption (TA) measurements and generally slower ET. In wild-type (WT) RCs, evidence favors two-step ET at room temperature (1, 12, 13, 15, 16). It has been previously proposed that minor degrees of superexchange occur in WT RCs, likely arising from or enhanced by the inherent distribution in the energies of P*, P+BA–, and P+HA– caused by protein populations with slight variations in amino acid nuclear coordinates around chromophores (5, 17–19), but this has been difficult to study experimentally (1, 12).

The ET mechanisms in RCs likely have their origins in the different energies of the various charge-separated states for the two branches relative to P* and each other (Fig. 1B) (20–22), but it is difficult to determine these energetics either experimentally or theoretically (1, 23). Contributions of individual symmetry-breaking amino acid have been thoroughly studied (1, 15, 24–28), and while the importance of certain amino acids has been ascertained, the roles of local protein–chromophore interactions are not always fully understood (8, 24, 25). One highly examined residue has been the tyrosine at site M210 (RC residue numbers are preceded by the protein subunit designation: H, L, or M) because it is a clear deviation in symmetry between A and B branches (Fig. 1A), it is close to BA, and it is the only one of 27 tyrosines that lacks a hydrogen bond acceptor. Theoretical studies indicate that the magnitude and orientation of the hydroxyl dipole of tyrosine M210 may play an important role in energetically stabilizing P+BA– (29, 30). Indeed, previous efforts to change the orientation of this tyrosine’s hydroxyl dipole significantly slowed ET (31). It is difficult, however, to subtly vary the electrostatic nature of this tyrosine using canonical mutagenesis without entirely removing the phenolic hydroxyl.

To perturb the effects of the tyrosine at M210 in WT protein, we used amber stop codon suppression (32–34) to site-specifically replace it with five noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs), each a tyrosine with a single electron-donating or electron-withdrawing meta-substituent (at the 3 position). We will refer to RC protein variants by acronyms for the amino acid incorporated at M210: 3-methyltyrosine (MeY), 3-nitrotyrosine (NO2Y), 3-chlorotyrosine (ClY), 3-bromotyrosine (BrY), and 3-iodotyrosine (IY) (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). In this way, we engineered a series of RC variants with more systematic electrostatic ET perturbation at this important tyrosine while minimally affecting other RC features.

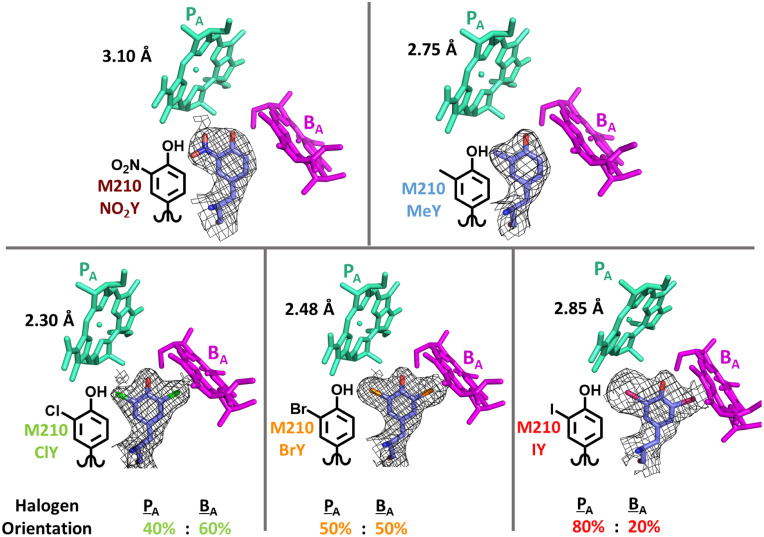

Fig. 2.

RC variants made and structurally characterized in this study, in which truncated PA and BA chromophores are depicted for each variant (in teal and magenta, respectively) and electron density maps from solved X-ray structures are shown (2Fo-Fc contoured at 1 σ) for tyrosine analogs at M210. Halogen variants required two different tyrosine ring conformers to model halogen substituent orientations with the contribution of each indicated, one with the halogen oriented toward P (only PA depicted above) and the other with halogen toward BA. The resolution for each crystal structure is denoted in black next to the PA of each RC variant (PDB IDs for NO2Y, MeY, ClY, BrY, and IY RCs are 7MH9, 7MH8, 7MH3, 7MH4, and 7MH5, respectively; SI Appendix, Table S2).

Results

Verification of ncAA Incorporation and Minimal Structural Perturbation.

In previous work, we took an amber suppression system developed for halotyrosine (ClY, BrY, and IY) incorporation in Escherichia coli (35) and transferred this system from E. coli to R. sphaeroides gene control, optimizing it for RC expression (36). Here, incorporation of MeY (37) is also performed using this previously created system (SI Appendix, sections S1.1 and S1.3–S1.4). We apply the same strategy used earlier (36) to a recently created amber suppression system (38) and genetically encode NO2Y incorporation in R. sphaeroides (SI Appendix, sections S1.1–S1.4). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) was used to verify ncAA incorporation for NO2Y and MeY RCs (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). The mass shifts of the M-subunit peak correspond to the respective mass of the incorporated ncAAs (within a mass accuracy of ±1 Da for a 30-kDa subunit) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), while the H and L subunits remained identical to their WT mass as shown in previous work (36). This shows the general adaptability of our previous methods for genetic code expansion in R. sphaeroides.

X-ray crystal structures of all variants were obtained at room temperature with resolutions comparable to those from previous room-temperature structures (39). These X-ray crystal structures (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S6 and Table S2) also verify ncAA incorporation at only site M210. All crystal structures possess additional electron density in the M210 tyrosine meta-position (Fig. 2), which corresponds to the relevant ncAA incorporated with a phenolic position for the tyrosine side chain similar to WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). MeY and NO2Y RCs have respective methyl- and nitro-substituents solely oriented toward PA, while halotyrosine RCs display electron density (i.e., occupancy) that required modeling of two different halogen conformations, one oriented toward PA and the other toward the Mg2+ of BA (Fig. 2). While the halogen-substituted tyrosines likely have comparable electrostatic properties given their similar Hammett parameters (40), pKa values (41), and because they have been noted to affect processes involving charge transfer similarly (42), differences in their size may have led to the change in population oriented toward PA as opposed to BA, since larger substituents are poorly accommodated by the smaller cavity next to BA (Fig. 2). For the BA-oriented substituent, this leads to halogen–Mg2+ distances of 3.4 Å (ClY), 3.4 Å (BrY), and 2.9 Å (IY). Dual halogen conformations for halotyrosine-containing proteins have been noted previously (37, 42, 43). Importantly, incorporation of all ncAAs at M210 in this study also proved to be minimally perturbative with respect to the remaining protein structure and chromophore positions and orientations; we found nearly identical interchromophoric distances and relative orientations to those present in the WT structure (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry numbers: 2J8C and 1K6L; SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S6 and Table S3). Rmsd is 0.229 to 0.261 Å for alignments to a room-temperature WT structure (1K6L) and is 0.333 to 0.367 Å for alignment to a 77-K WT structure (2J8C).

ET Kinetics.

ET dynamics of the M210 variants were determined by TA through a combination of 1) the assessment of raw real-time spectra (SI Appendix, Figs. S13–S18) and single-wavelength kinetic fits (SI Appendix, Figs. S7–S38), 2) model-independent global analysis (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Figs. S39–S55), and 3) model-dependent global analysis (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S56–S73). Results are summarized in SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5. TA kinetics at 924 nm and at 542 nm demonstrate that there is biexponential P* decay and P+HA– formation for all variants (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 and S20). The biexponential P* stimulated emission decay at 924 nm for WT and all variants reflects one P* population that decays with a lifetime of ∼3 ps and a second P* population that decays with a lifetime of ∼20 ps (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 and Table S4). P+HA– formation detected at 542 nm has similar kinetics (SI Appendix, Fig. S20 and Table S4). This biexponential P* decay and P+HA– formation has been noted previously in the literature for WT RCs (6, 10, 15, 18, 19, 44, 45).

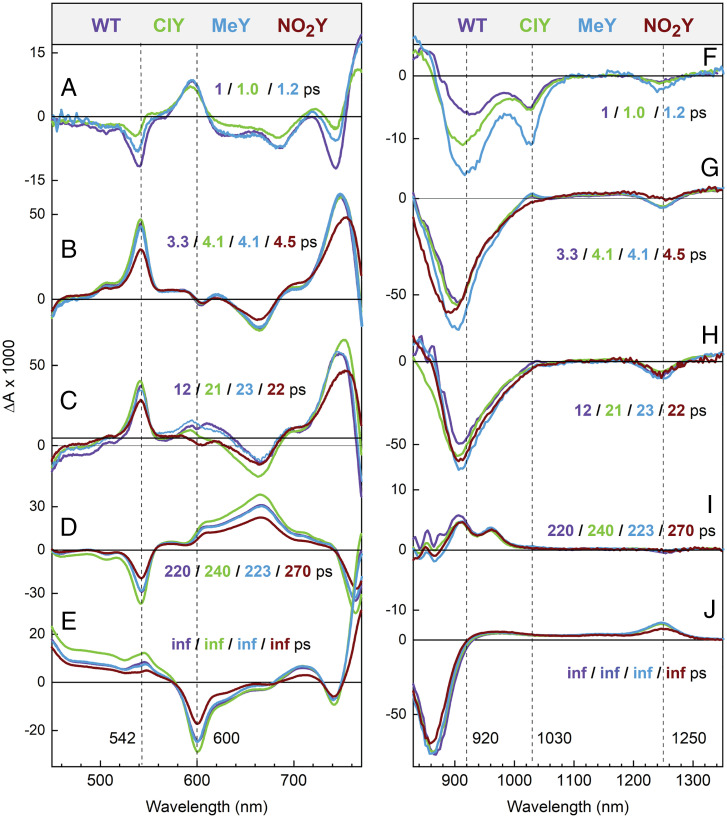

Fig. 3.

Comparison of visible (A–E) and near-infrared (F–J) DADS for WT, ClY, MeY, and NO2Y. DADS for BrY and IY are very similar to that of ClY and are given in SI Appendix, Figs. S39–S43. Here “inf” refers to a component with an effectively infinite lifetime (∼108 ps) to model charge-transfer states that do not decay over the duration of the experiment (104 ps).

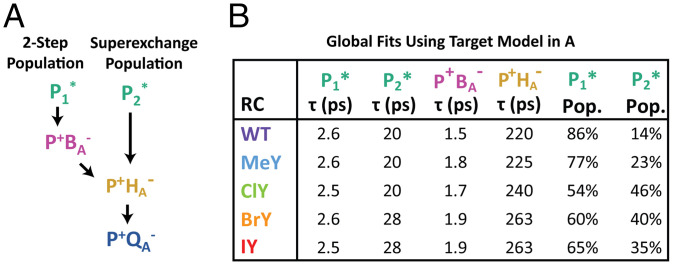

Fig. 4.

Target analysis model and fits. (A) Kinetic model implemented for target analysis for WT and all variants except NO2Y (SI Appendix, Fig. S56). (B) Species decay lifetimes and RC population (Pop.) decaying through a two-step (P1*) or superexchange (P2*) ET pathway. While slight differences exist among RC variants for P1* and P2* decay time constants, data fit with a target analysis model with the same P* decay lifetimes for all RC variants result in similar satisfactory SADS.

Global analysis of the TA data also supports biexponential P* decay and P+HA– formation (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Table S4). A model-independent global fit returns decay-associated difference spectra (DADS), which are spectra composed of the preexponential coefficients at every wavelength for a given lifetime component in the fit. A DADS reflects the change in absorbance associated with a given lifetime (46, 47). While no DADS corresponds directly to one ET intermediate, it contains features indicative of the associated ET species. DADS spectral features and lifetimes guide a target model for global analysis that returns species-associated decay spectra (SADS) (refer to SI Appendix, section S3.2 for further discussion of SADS and DADS). DADS for all variants are remarkably similar; the same number of lifetimes are required to fit every variant except for NO2Y (Fig. 3), which did not require a ∼1-ps component for a global fit. Spectral features for each time component were also very similar among variants. The ∼4-ps and ∼1-ps DADS (for all variants but NO2Y) show features consistent with a two-step ET model for P* → P+BA– → P+HA–. These features include those for P+ (1,250 nm), BA– (1,030 nm), BA and P bleaching (600 nm), and HA bleaching (542 nm), all appropriately signed. In comparison, the 12- to 20-ps DADS showed features consistent with a superexchange ET model (P* → P+HA–), where P+ and HA– features are present but the 1,030-nm feature (associated with the BA– anion absorption) is absent or significantly diminished, as noted previously (15). A greater proportion of the P* population that decays with the ∼20-ps lifetime is present in all the variants than in WT (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Table S4). The ∼4-ps DADS for the NO2Y variant does not possess a clear 1,030-nm feature that would indicate BA– production. Further DADS comparisons are given in SI Appendix, Figs. S39–S55.

Based on the DADS features and single-wavelength kinetics discussed in the previous two paragraphs, two P* populations are present, which give rise to P+HA– via different mechanisms as opposed to simply reflecting the same process with differing rates (refer to SI Appendix, section S3.2 for details). For all the variants, except NO2Y, data were fit globally using a minimal target analysis model with one P* population decaying via a two-step ET process and the other via one-step superexchange ET (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S56A). Using this target model, we can reproduce differences in kinetics for each variant primarily by varying the relative amounts of the two P* populations. As was seen from the DADS, the SADS also show a larger portion of the ∼20-ps P* population in the variants relative to WT (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Table S4). Additional effects include relatively small increases in P+HA– lifetimes, similar to the effects of other mutations, which are closer to BA than HA and also assumed nonperturbative on HA (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Table S4) (48). Not needed in our target analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S56) is a 100- to 200-ps component for P* internal conversion to the ground state (27, 49), consistent with all variants having a high quantum yield of P+HA– formation similar to WT. Raw TA spectra also support this high quantum yield. At probe times at which P+HA– is the dominant species present (∼25 ps) (SI Appendix, Figs. S63, S65, S67, S69, S71, and S73) and in the P+HA– SADS (SI Appendix, Fig. S60), the bleaching magnitudes at 542 nm (HA–) and 600 nm (P*/P+) are roughly equal, consistent with the similar extinction coefficients of these two HA and P features in the chromophore basis spectra (50, 51). The 600-nm bleach at ∼25 ps is also similar in magnitude to the 600 nm bleach for P* at 0.5 ps (SI Appendix, Figs. S13A–S18A), again indicating high (essentially unity) conversion of P* → P+HA– in both populations.

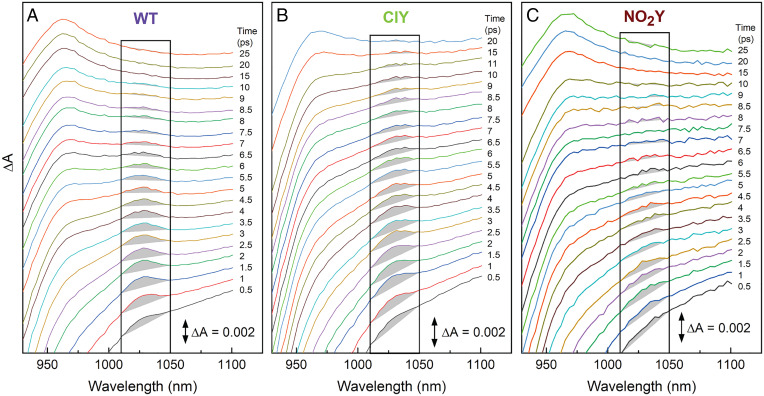

Except for the NO2Y variant, the TA data clearly support a model in which two-step and one-step superexchange ET both occur. This is less certain in the NO2Y variant, for which the 1,030-nm BA anion feature in the raw TA spectra (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Figs. S18, S36–S38) and in DADS/SADS (SI Appendix, Figs. S39, S54, S55, S57, and S72) is absent or substantially diminished. In the time evolution of the raw TA spectra in the 930- to 1,100-nm window (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Figs. S21–S38), WT and ClY/BrY/IY/MeY variants display BA anion band formation centered at 1,030 nm. NO2Y RCs, however, show little to no integrated area for the 1,030-nm transient feature above the baseline, which changes due to the background of P* decay and growth of the HA– band at ∼960 nm (Fig. 5). In overlays for NO2Y RCs in which baselining has not been performed (SI Appendix, Fig. S36), it is difficult to distinguish any 1,030-nm feature visually. It must also be noted that NO2Y RCs have 90% fidelity for replacement of tyrosine with NO2Y (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), and the 10% WT present would contribute a signal at 1,030 nm, further diminishing any 1,030-nm feature that might be attributed to NO2Y BA–. The simplest explanation for the absent or significantly diminished 1,030-nm band in the NO2Y variant is that P* decays directly to P+HA– via one-step superexchange, without formation of P+BA– as a discrete intermediate, in both P* populations. Though the presence of a P* population that undergoes fast ∼5-ps superexchange ET alongside the previously identified ∼12- to 20-ps superexchange population (15, 19, 52), has not been reported, we know of no reliable estimates that limit the rate of P* → P+HA– superexchange ET in RCs. Alternatively, it is possible that P+BA– builds up to a much lesser extent in NO2Y RCs (compared to WT and the other variants) because the P+BA– lifetime is much shorter. To account for the two possibilities, we modeled both scenarios for the NO2Y variant (SI Appendix, Figs. S54, S56, S72, and S73). Whichever model of ET is used, it is clear that primary ET in the NO2Y variant is affected more than primary ET in any other variant. Further mechanistic insight into ET in NO2Y and other RCs’ ET requires information on how these RC variants change the free energy of P+BA–, as described in the following section (Energetic Characterization).

Fig. 5.

Spectral evolution of the 930- to 1,130-nm TA spectrum at early times for (A) WT, (B) ClY, and (C) NO2Y RCs (BrY/IY/MeY variants shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S29, S32, and S35). The spectra are vertically offset from one another to best display the integrated area highlighted in gray (1,010 to 1,050 nm) of the 1,030-nm band of P+BA− (SI Appendix, section S3.6). The gray integrated area for the 1,030-nm feature was separated from P* and P+HA– background via an applied linear baseline.

To be rigorous, it is important to note that superexchange ET involves a small degree of mixing of the P+BA– virtual intermediate with the P* reactant and P+HA– product states when treated with first-order perturbation theory (53). This mixing would imply that some minor degree of BA– character could be manifest in spectral features, though significantly less than if P+BA– were an actual intermediate. Computational insights into spectral contributions (e.g., at 1,030 nm) of a P+BA– virtual intermediate in superexchange ET would be desirable.

As suggested by Niedringhaus et al. and others (14, 54), it is possible that the two-step versus superexchange mechanism dichotomy is too simplistic (55, 56). The difference in rates in the two P* populations in NO2Y, which may both involve some form of superexchange ET, also suggests that the usual formulation of the superexchange mechanism itself may be too simplistic. Electronic interactions exist not just between the pair of bacteriochlorophylls in P but also involve the other RC chromophores. Thus, the true mechanism may be an admixture of two-step (i.e., sequential) ET and superexchange ET mechanisms, with the initial charge delocalized to varying extents over the BA and HA chromophores in the first ET intermediate depending on their relative energetics as discussed by Sumi et al. (55, 56). While we use limiting two-step versus superexchange models for tractability, further computational characterization of these more complex scenarios (55) and the limiting rates of superexchange ET in RCs are required to refine our analysis.

Energetic Characterization.

To characterize the energetic perturbation of the tyrosine variants, we estimated the shift in P*/P+ potential using P near-infrared absorption and P/P+ redox titrations and estimated the energetics of charge-separated intermediates using resonance Stark spectroscopy (Fig. 6). The room-temperature NIR Qy absorbance maxima of P shifted, at most, 15 nm (IY, 179 cm−1 or 22 meV) compared to WT (SI Appendix, Figs. S74 and S76). Redox titrations show P redox potentials shift by, at most, 26 mV (IY, SI Appendix, Figs. S75 and S76). When changes in both P absorption and P redox potential are combined as performed previously (10) (SI Appendix, Fig. S76), RC variants at most disfavor P* oxidation by 18 ± 5 meV (MeY) relative to WT (Fig. 7 and SI Appendix, Fig. S76B). These P* oxidation energetic changes are minimal when compared to the ∼100- to 300-meV free-energy changes seen in certain mutants, which target P directly (10) and, given the proximity of residue M210 to P, are a surprising result, especially in the case of the NO2Y RC (Fig. 2).

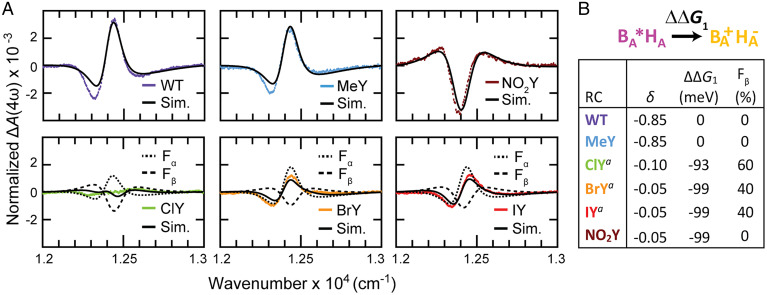

Fig. 6.

Resonance Stark spectra for BA and extracted energetics. (A) Resonance Stark spectra ΔA determined for RC variants at the fourth harmonic (4ω) of the external electric field modulation frequency ω (refer to SI Appendix, sections S5.1–S5.4 for description and the corresponding 6ω spectra). Stark spectra are normalized to a field of 1 MV/cm (SI Appendix, section S5.3). (B) The values for the parameter, δ, are extracted from the ΔA(4ω) and ΔA(6ω) Stark spectra in A and SI Appendix, section S5.4, respectively, and the change in ΔG1 relative to WT () is determined from δ for the various RCs. Error in ΔΔG1 is ∼2 meV and is due to fitting error. The energetic process associated with is depicted and labeled above the extracted Stark parameters. The superscript a next to ClY, BrY, and IY is used to note that halotyrosine Stark spectral fits require two fractions, which sum to 1; only ΔΔG1 for the β-fraction (Fβ) is shown for halotyrosine RCs. The α-fraction (Fα) for halotyrosine RCs is comparable to WT in energetics.

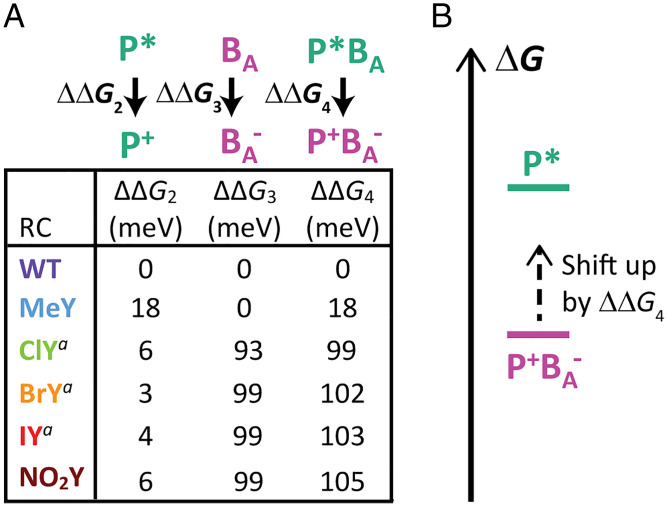

Fig. 7.

(A) Relative change in energetics from WT for P* oxidation () and BA reduction () from WT (refer to SI Appendix, Fig. S76 for determination from NIR absorption and redox titration). We take ΔΔG2 + ΔΔG3 = ΔΔG4 (where positive ΔΔG4 values are destabilizing). Energetic processes are depicted and labeled above each column. The superscript a next to ClY, BrY, and IY is used to note that energetics for halotyrosine variants are shown only for the resonance Stark population (β-fraction) with non-WT BA redox energetics. (B) Diagram depicting the impact of ΔΔG4, where the free energy of P+BA– is raised by ΔΔG4.

There is no direct way to obtain information on the BA/BA– reduction potential in situ. It is, however, possible to obtain information on the relative oxidation potentials of BA in these variants using resonance Stark effect (RSE) spectroscopy. BA* is coupled to BA+HA– whose energy is very sensitive to an applied electric field. We have described the RSE in detail in a series of papers (57–60) (SI Appendix, sections S5.1–S5.3 and Figs. S78–S80), discovered over the course of measurements of higher-order Stark effects for the RC and related pigments (61). Electronic Stark spectra (ΔA; field-on minus field-off absorbance) are typically obtained using lock-in detection at the second harmonic of the applied electric field modulation frequency, ω, giving ΔA(2ω). For an isotropic immobilized sample, ΔA(2ω) is typically the second derivative of the absorption spectrum when the change in dipole moment between the ground and electronically excited states dominates the electrooptic parameters, as is the case for all the photosynthetic pigments in isolation (61). Data can also be extracted at higher even harmonics of the field modulation frequency (i.e., 4ω, 6ω, etc.); ΔA(4ω) is typically the fourth derivative of the absorption [or second derivative of ΔA(2ω)], ΔA(6ω) is the sixth derivative, and so on. Surprisingly, when this experiment is performed for BA* in the RC (but not for an isolated bacteriochlorophyll), a very different line shape dominates the higher-order spectra (57, 62), as the conventional derivatives become very small. Through a series of experiments, this effect has been linked to the driving force for the BA*HA → BA+HA– reaction (ΔG1), and a comprehensive theory describing the unusual but expected line shapes of these RSEs has been developed (57–60). Since the Y(M210)F mutation dramatically affects the observed line shape and amplitude (60), we expected other changes in the vicinity of BA could affect the RSE spectra and provide information on the energetics of this process. We then use information on changes in the BA/BA+ potential to estimate effects on BA/BA–, as described in detail in the following two paragraphs.

As shown in Fig. 6A, it is immediately evident from the Stark spectra detected at the fourth harmonic of the modulation frequency, ΔA(4ω), that MeY is quite similar to WT, that the halotyrosines show significantly reduced intensities compared to WT but are similar to each other, and that NO2Y has a very different line shape [refer to SI Appendix, Figs. S83–S89 for the sixth harmonic counterparts, ΔA(6ω)]. We seek to extract the change in driving force of an RC variant relative to WT, ΔΔG1, encoded in the change in δ (refer to Eq. S22 in SI Appendix, section S5.3 for definition), from these line shapes (Fig. 6B). As performed previously (60), this energetic determination assumes that WT and all RC variants have the same homogeneous and inhomogeneous line widths for BA (and for BB) and identical reorganization energies for the pertinent charge-transfer process (SI Appendix, section S5.3). This is based on previous work showing that the choice of homogeneous and inhomogeneous line width does not appreciably affect fitting and derived parameters (59, 60); the combined effects from these parameters simply recapitulate the line shape of B without an applied external field. Only one set of physically reasonable ET parameters (i.e., single fractional component fits) is required to reproduce the line shapes and magnitudes of the Stark spectra for WT, MeY, and NO2Y. As expected, the introduction of the weakly electron-donating methyl group barely perturbs ΔG1, while the strongly electron-withdrawing nitro group lowers the energetics of BA*HA → BA+HA– by ∼100 meV (Fig. 6B). The halotyrosine variants fail to conform to the one-fraction fit strategy; they give rise to unsatisfactory fits and/or require unphysically small charge-transfer distances* inferred from the diminished magnitude in Stark spectra (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Figs. S86–S89) and inconsistent with the invariant interchromophoric distances between BA and HA observed in the X-ray structures across all variants (SI Appendix, Table S3). Instead, a second fraction with a second set of ET parameters is required. One reasonable origin for these two fractions in halotyrosine RCs is the two halogen orientations modeled in the crystal structures (Fig. 2); only one orientation is observed for WT, MeY, and NO2Y, and a single-fraction fit to Stark spectra is sufficient for these samples. To deconvolve the underlying two fractions from the Stark spectra of halogenated RCs, we assume that the fraction that corresponds to the crystallographic population with the halogen atom pointing away from BA possesses WT-like energetics (α-fraction). This is justified by the fact that halogens typically do not substantially perturb the electronic properties of aromatic rings even when directly attached to the π-system being spectroscopically probed (37, 42) and because MeY, which is similarly weakly perturbative, leaves ΔG1 intact (Fig. 6B). By initializing fits with relative fractions from halogen occupancies in crystal structures, we reveal another fraction (β fraction; Fβ in Fig. 6B) that showed energetics more similar to those in the NO2Y counterpart (ΔΔG1 ∼ −100 meV; Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Figs. S83–S89). The Stark features of the underlying populations (see WT and NO2Y as the limiting cases) tend to cancel, leading to diminished magnitudes in ΔA(4ω) for halogenated species. In ClY, a larger β-fraction contribution leads to near-complete Stark feature cancellation (Fig. 6A, green), while BrY and IY have a smaller contribution from the β-fraction and, consequently, less cancellation between Stark features from these two underlying fractions (Fig. 6A, orange and red). This degree of cancellation is largely consistent with the relative contributions of the two tyrosine rotamers as determined from crystal structures (Fig. 2). Refer to SI Appendix, section S5.4 for a detailed analysis of the modeling of these spectra.

The resonance Stark data indicate tyrosine perturbation has a significant impact on G1. Since tyrosine modification is significantly farther from the HA chromophore than it is to BA or P (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) and no structural changes are observed around HA (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), we approximate the magnitude of to be due primarily to an impact on the energetics of BA oxidation. To better understand the origin of the observed TA kinetics, we require information on BA reduction. We argue that should be roughly equal to the G for BA → BA– () under the two following approximations: 1) The BA* energy, HA reduction potential, and interchromophore coulombic interactions are not affected by tyrosine variant incorporation, as evidenced by the absence of structural changes and the insignificant energetic shifts in BA absorbance maxima (SI Appendix, Figs. S74 and S76). 2) A general environmental effect of the mutations on the electronic structure of BA would impact the propensities for BA+ and BA– formation in an equal and opposite fashion (i.e., any electronic polarization effect can be neglected). In this regard, since the Qy band of bacteriochlorins is dominated by the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) free energy gap (63), the HOMO and LUMO of BA appear to be shifted similarly by the tyrosine variants because the Qy band of BA (and BB) at 800 nm is shifted at most ∼3 nm (∼4 meV) among the RC variants (SI Appendix, Fig. S74). While these approximations may not be appropriate to characterize absolute energetics, they are reasonable to estimate changes in energetics relative to WT (refer to SI Appendix, section S4.4 for further discussion of these approximations).

When we combine the changes in energetics of P* oxidation and BA reduction, it is clear that the energetics of P* → P+BA– are significantly impacted in NO2Y and in one fraction (Fβ) of the halotyrosine variants, increasing the energetics of P+BA– formation by over 100 meV relative to WT ( in Fig. 7). This is a significant change when considering P+BA– is estimated to be ∼70 meV below P* in energy in WT (Fig. 1B) (15, 19, 64, 65). In fact, in a recently published study performed at a high level of theory, Tamura et al. (22) indicate that P+BA– is above P* in energy in WT RCs, which, if correct, would mean 1) that the P* → P+BA– → P+HA– two-step process would not occur, and 2) that an ∼100-meV energetic increase would be even more significant. Comparing WT → MeY → halotyrosine RCs, as the energetics of P+BA– formation ( increases (Fig. 7), so too does the amount of ∼20-ps superexchange population observed in TA global analysis (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Table S4). This would match the smaller energetic dependence of the rate constant for P+BA– formation in the superexchange mechanism compared to the rate constant in the two-step pathway (53), as the former mechanism is less disfavored than the latter by the increased P+BA– energy. For both models used for NO2Y ET (SI Appendix, Fig. S56), there is also an increase in the ∼20-ps P2* population relative to WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S72 and Tables S4 and S5), similar to the other RC variants (SI Appendix, Table S4).

As stated earlier, the 1,030-nm BA– feature is absent or significantly diminished for NO2Y RCs (Fig. 5). In the following, we reevaluate whether two-step or superexchange ET is occurring in the context of resonance Stark spectroscopy data and other kinetic and structural characterization. The NO2Y X-ray structure shows that the nitro group is significantly closer to P and BA, so it is unlikely that the HA/HA– reduction potential is significantly affected (Figs. 1A and 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Past studies indicate P+BA– decay is already energetically barrierless in WT (5, 66), so raising the free energy of P+BA– while minimally affecting P+HA– free energy would decrease the rate of P+BA– decay in a two-step mechanism. NO2Y RCs are like WT and other variants with regard to interchromophoric distances and other environmental features (SI Appendix, Table S3), but resonance Stark spectroscopy on BA indicates that the coupling between BA* and BA+HA– is smaller for NO2Y RCs (and every RC variant) relative to WT (SI Appendix, Table S7). This would suggest that if electronic coupling between P+BA– and P+HA– is changing, it also decreases (the electron transfers between the same set of molecular orbitals), which would further decrease the rate of P+BA– decay. Because the P* decay rate (i.e., P+BA– formation rate) is unambiguous at 924 nm and only decreases modestly from a 3-ps lifetime in WT to 4.5 ps in NO2Y RCs (SI Appendix, Table S5), a decrease in P+BA– decay rate would lead to increased P+BA– buildup at 1,030 nm as opposed to the absent/diminished signal we observe (Fig. 5). Given the large increase in the free energy of P+BA– in NO2Y RCs, in the context of barrierless ET, decreased electronic coupling, and the absent/diminished 1,030-nm feature (made smaller by the 10% WT contribution, which must be discounted), it does not appear that two-step ET is occurring in NO2Y RCs, and, instead, the population normally undergoing two-step ET is more likely a superexchange pathway. The P* population with a ∼5-ps superexchange ET alongside the ∼20-ps population more commonly identified as a superexchange population may reflect the relative energy denominators for electronic mixing in superexchange that depend on the relative energies for P+BA–, P+HA– and P*. The absence of this change in mechanism (the predominant loss of a two-step process) in halotyrosine RCs may be due to either or both of the following two effects: 1) only one fraction of halotyrosine RCs experience this large increase in energetics as evidenced by the two fractions observed from Stark spectroscopy; and 2) the RC fraction in which energetics are perturbed (Figs. 6 and 7) appears correlated with the fraction with the halogen <3.5 Å from the Mg2+ (Fig. 2). Resonance Stark data for BA indicates that, as in NO2Y RCs, the coupling between P+BA– and P+HA– has likely decreased in halotyrosine RCs (SI Appendix, Table S7), and it is possible that other interchromophoric interactions in halotyrosine RCs are changing that we cannot experimentally assess. It is important to note that while we attempt to rationalize all experimental observations, ultimately, our models (and models of others in the field) are likely incomplete. For this reason, we have presented extensive documentation for all aspects of the data to encourage more sophisticated analyses.

Discussion

In this study, we have made a series of membrane protein complexes with site-specifically incorporated ncAAs. Within this series of pseudo-C2 symmetric proteins, we systematically vary one structural feature of an important symmetry-breaking amino acid, Tyr M210. In each tyrosine analog, the tyrosine’s electrostatic nature is altered with different electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents at the meta-position, which modulates the tyrosine hydroxyl’s interaction (29, 30, 67) with the BA chromophore via induction. We then utilize three distinct techniques, X-ray crystallography, TA spectroscopy, and resonance Stark spectroscopy, to determine structural information, ET kinetics, and the energetics relevant to primary ET. The collective information from these three distinct techniques helps to rationalize the consequences of our tyrosine analog incorporation.

Structural analysis indicates none of these tyrosine variants caused measurable structural perturbation (i.e., nuclear displacement) of other protein residues, cofactors, or electron donors and acceptors (SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S6 and Table S3). Consequently, interchromophoric interactions and chromophore molecular orbital overlap(s) should be relatively unaffected by tyrosine perturbation. This said, resonance Stark spectroscopy suggests electronic coupling(s) at least between P+BA– and P+HA– decreases for all RC variants, perhaps highlighting the importance of local interactions and small distance changes, which we cannot experimentally resolve.

Stark spectroscopy indicates the energetics of ET involving BA are impacted significantly in halotyrosine (β-fraction) and NO2Y RCs (∼100 meV, Figs. 6 and 7), while redox titrations and absorbance spectra indicate the effects on P* oxidation are relatively minor (≤18 meV, Fig. 7). Only halotyrosine RCs require two conformers in crystallography and two energetic fractions for resonance Stark spectroscopy, but all RCs require two P* populations to fit kinetic data; because of this observation, we only directly relate the resonance Stark fractions and the crystallographic conformations of halotyrosine RCs. Unlike in past studies (4, 10, 19, 48, 68), our energetic approach is a purely experimental estimate for the environmentally tuned energetics of P+BA– formation. These estimations are at least qualitative and are treated in this study as semiquantitative values. For discussion regarding potential structural origins of P+BA– destabilization in MeY, NO2Y, and halotyrosine RCs, refer to SI Appendix, section S4.5.

As these RC variants exhibit increasingly disfavored P+BA– formation energetically (Fig. 7), an increased proportion of the P* population appears to decay by ET directly to HA via a ∼20-ps superexchange mechanism (e.g., no P+BA– intermediate) (Fig. 4) based on DADS/SADS and an ET competition model proposed previously (19). With our introduction of amber suppression into R. sphaeroides, we hope to site-specifically introduce ncAAs containing nitrile vibrational probes (36, 69–71), which can act as true ET spectators whose response will not be obfuscated by interchromophoric electronic coupling or electronic absorption shifts from the formation and decay of charged intermediates.

Despite the significant energetic impact of some ncAAs and the impact on electronic coupling, no tyrosine modification made an order of magnitude impact on the overall rate (5, 10, 31, 72) or yield (27) of ET, highlighting the robust nature of the RC’s protein design (1, 4–11). This small overall effect may be a consequence of this dual-mechanism model, in which the superexchange mechanism is acting as an alternative functional pathway for ET as previously proposed in the literature (19) through a lowered sensitivity to energetic changes of the P+BA– intermediate. Without this additional pathway for ET, ET yield would likely decrease significantly following NO2Y introduction at M210 due to the increased amount of RC population possessing a P+BA– state higher in free energy than P* and due to the decreased electronic coupling between P+BA– and P+HA–. Clearly, the tyrosine at M210 is not the only stabilizing factor for A branch ET. Multiple protein features contribute to overall RC function (20) and disfavor B-branch ET (15, 26, 27, 73). That said, the tyrosine at M210 is important for tuning the mechanism to be one of two-step ET in WT. This is highlighted by the NO2Y RC, in which the increase in a slow P* population relative to WT is accompanied by the (near) absence of a 1,030-nm feature associated with BA anion formation (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Figs. S21–S38) indicating a change in ET mechanism. Given the specificity and efficiency of two-step ET in bacterial RCs, a tyrosine or phenol, which interacts with an electron donor and acceptor, as does the tyrosine at M210, may be helpful to encourage charge transfer and develop or improve other synthetic catalysts (74–76) and enzymes (77, 78). Further research on this model for photoinduced charge transfer with tools such as amber stop codon suppression will likely continue to enhance our understanding of how specific protein interactions are relevant to obtaining specific ET products, a key tenet of any catalysis and crucial to understanding ultrafast ET in the RC.

Materials and Methods

For a full description of methods utilized in this work, refer to SI Appendix. Briefly, RC variants were prepared via introduction of amber suppression machinery (with modifications) into R. sphaeroides (35, 36, 38), and protein expression was performed as described previously (SI Appendix, sections S1.1–S1.4) (36, 79). Fidelity of ncAA incorporation was assessed via LC–MS (36) (SI Appendix, section S2.1). RC crystals were obtained via the hanging drop method, and room-temperature crystal structures were obtained using the Russi et al. procedure (SI Appendix, sections S2.1–S2.3) (80). TA measurements were acquired with a 1-KHz amplified Ti:Sapphire laser (Spectra Physics) coupled to Helios and EOS detection spectrometers (Ultrafast Systems) following previous methodology (15) (SI Appendix, section S3.1). Single-wavelength fits were performed using OriginLab, and global analysis was performed with CarpetView (Light Conversion) or SurfaceXplorer (Ultrafast Systems) (SI Appendix, sections S3.2–S3.11). Redox titrations were done utilizing a potassium ferrocyanide/ferricyanide redox couple (SI Appendix, sections S4.2) (31). All resonance Stark spectroscopy was performed at 77K (37, 60) with the Stark signal ΔI (4ω) and ΔI (6ω) detected at the fourth (4ω) and sixth harmonic (6ω), respectively, of the applied alternating current (AC) field (SI Appendix, sections S5.2), and the analysis was discussed extensively throughout SI Appendix, sections S5.1–S5.5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.B.W. was supported by a Stanford Center for Molecular Analysis and Design Fellowship. C.-Y.L. was supported by a Kenneth and Nina Tai Stanford Graduate Fellowship and the Taiwanese Ministry of Education. This work was supported by a grant from the NSF Biophysics Program to S.G.B. (MCB-1915727). K.M.F, D.H., and C.K. were supported by a grant from the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (DE-CD0002036). We thank Prof. Thomas Beatty and Dr. Daniel Jun at the University of British Columbia for their generous contribution of the RC plasmid vector (pIND4-RC) and sequence information. We thank Prof. Ryan Mehl and Dr. Joseph Porter for providing amber suppression (F4 and A7) gene sequences (SI Appendix, sections S1.1 and S1.2) as well as helpful discussion regarding NO2Y incorporation in a new bacterial host. We thank the Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University Mass Spectrometry, and particularly Theresa Laughlin for their support in performing the LC–MS in this study. We also thank Tom Carver of the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities for depositing nickel on Stark windows.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2116439118/-/DCSupplemental.

*Short distances ranged from 7.0 Å/f to 8.2 Å/f as opposed to the 9.5-Å/f to 13.1-Å/f distances determined for RCs previously. Here, f is a local field factor, which arises because the applied electric field is different from the field experienced by the chromophore, and distances that are determined via resonance Stark spectroscopy contain this factor. The factor f is greater than 1 and considered constant for different RCs (refer to SI Appendix, sections S5.2–S5.4 for further discussion).

Data Availability

X-ray crystal structures have been deposited in the PDB [7MH9 (81), 7MH8 (82), 7MH3 (83), 7MH4 (84), and 7MH5 (85)]. All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Parson W., Warshel A., “Mechanism of charge separation in purple bacterial reaction centers” in The Purple Phototrophic Bacteria, Hunter C. N., Daldal F., Thurnauer M. C., Beatty J. T., Eds. (Springer, 2009), pp. 356–377. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wraight C. A., Clayton R. K., The absolute quantum efficiency of bacteriochlorophyll photooxidation in reaction centres of Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 333, 246–260 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton R. K., Yamamoto T., Photochemical quantum efficiency and absorption spectra of reaction centers from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides at low temperature. Photochem. Photobiol. 24, 67–70 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beekman L. M. P., et al. , Primary electron transfer in membrane-bound reaction centers with mutations at the M210 position. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 7256–7268 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagarajan V., Parson W. W., Davis D., Schenck C. C., Kinetics and free energy gaps of electron-transfer reactions in Rhodobacter sphaeroides reaction centers. Biochemistry 32, 12324–12336 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkele U., Lauterwasser C., Zinth W., Gray K. A., Oesterhelt D., Role of tyrosine M210 in the initial charge separation of reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 29, 8517–8521 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagarajan V., Parson W. W., Gaul D., Schenck C., Effect of specific mutations of tyrosine-(M)210 on the primary photosynthetic electron-transfer process in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7888–7892 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson E. T., et al. , Effects of ionizable residues on the absorption spectrum and initial electron-transfer kinetics in the photosynthetic reaction center of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 42, 13673–13683 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams J. C., et al. , Effects of mutations near the bacteriochlorophylls in reaction centers from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 31, 11029–11037 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffa A. L. M., et al. , The dependence of the initial electron-transfer rate on driving force in Rhodobacter sphaeroides reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 7376–7384 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schenkl S., et al. , Selective perturbation of the second electron transfer step in mutant bacterial reaction centers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1554, 36–47 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinth W., Wachtveitl J., The first picoseconds in bacterial photosynthesis--Ultrafast electron transfer for the efficient conversion of light energy. ChemPhysChem 6, 871–880 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakitani Y., Hou A., Miyasako Y., Koyama Y., Nagae H., Rates of the initial two steps of electron transfer in reaction centers from Rhodobacter sphaeroides as determined by singular-value decomposition followed by global fitting. Chem. Phys. Lett. 492, 142–149 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niedringhaus A., et al. , Primary processes in the bacterial reaction center probed by two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 3563–3568 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laible P. D., et al. , Switching sides-reengineered primary charge separation in the bacterial photosynthetic reaction center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 865–871 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yakovlev A. G., Shkuropatov A. Y., Shuvalov V. A., Nuclear wave packet motion between P* and P+BA- potential surfaces with a subsequent electron transfer to H(A) in bacterial reaction centers at 90 K. Electron transfer pathway. Biochemistry 41, 14019–14027 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirmaier C., Holten D., Evidence that a distribution of bacterial reaction centers underlies the temperature and detection-wavelength dependence of the rates of the primary electron-transfer reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 3552–3556 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia Y., et al. , Primary charge separation in mutant reaction centers of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 13180–13191 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bixon M., Jortner J., Michel-Beyerle M. E., A kinetic analysis of the primary charge separation in bacterial photosynthesis. Energy gaps and static heterogeneity. Chem. Phys. 197, 389–404 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunner M. R., Nicholls A., Honig B., Electrostatic potentials in Rhodopseudomonas viridis reaction centers: Implications for the driving force and directionality of electron transfer. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 4277–4291 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parson W. W., Chu Z. T., Warshel A., Electrostatic control of charge separation in bacterial photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1017, 251–272 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura H., Saito K., Ishikita H., Acquirement of water-splitting ability and alteration of the charge-separation mechanism in photosynthetic reaction centers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 16373–16382 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter M., Fingerhut B. P., Coupled excitation energy and charge transfer dynamics in reaction centre inspired model systems. Faraday Discuss. 216, 72–93 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saggu M., Fried S. D., Boxer S. G., Local and global electric field asymmetry in photosynthetic reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 1527–1536 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robles S. J., Breton J., Youvan D. C., Partial symmetrization of the photosynthetic reaction center. Science 248, 1402–1405 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dylla N. P., et al. , Species differences in unlocking B-side electron transfer in bacterial reaction centers. FEBS Lett. 590, 2515–2526 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang J. I., Boxer S. G., Holten D., Kirmaier C., High yield of M-side electron transfer in mutants of Rhodobacter capsulatus reaction centers lacking the L-side bacteriopheophytin. Biochemistry 45, 3845–3851 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bylina E. J., Kirmaier C., McDowell L., Holten D., Youvan D. C., Influence of an amino-acid residue on the optical properties and electron transfer dynamics of a photosynthetic reaction centre complex. Nature 336, 182–184 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alden R., Parson W., Chu Z., Warshel A., Orientation of the OH dipole of tyrosine (M)210 and its effect on electrostatic energies in photosynthetic bacterial reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 16761–16770 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawashima K., Ishikita H., Energetic insights into two electron transfer pathways in light-driven energy-converting enzymes. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 9, 4083–4092 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saggu M., et al. , Putative hydrogen bond to tyrosine M208 in photosynthetic reaction centers from Rhodobacter capsulatus significantly slows primary charge separation. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 6721–6732 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dumas A., Lercher L., Spicer C. D., Davis B. G., Designing logical codon reassignment - Expanding the chemistry in biology. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 6, 50–69 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drienovská I., Roelfes G., Expanding the enzyme universe with genetically encoded unnatural amino acids. Nat. Catal. 3, 193–202 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young D. D., Schultz P. G., Playing with the molecules of life. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 854–870 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang H. S., et al. , Efficient site-specific prokaryotic and eukaryotic incorporation of halotyrosine amino acids into proteins. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 562–574 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver J. B., Boxer S. G., Genetic code expansion in rhodobacter sphaeroides to incorporate noncanonical amino acids into photosynthetic reaction centers. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 1618–1628 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin C.-Y., Romei M. G., Oltrogge L. M., Mathews I. I., Boxer S. G., Unified model for photophysical and electro-optical properties of green fluorescent proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15250–15265 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter J. J., et al. , Genetically encoded protein tyrosine nitration in mammalian cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1328–1336 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pokkuluri P. R., et al. , The structure of a mutant photosynthetic reaction center shows unexpected changes in main chain orientations and quinone position. Biochemistry 41, 5998–6007 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammett L. P., The effect of structure upon the reactions of organic compounds. Benzene derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 59, 96–103 (1937). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jover J., Bosque R., Sales J., Neural network based QSPR study for predicting pKa of phenols in different solvents. QSAR Comb. Sci. 26, 385–397 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romei M. G., Lin C.-Y., Mathews I. I., Boxer S. G., Electrostatic control of photoisomerization pathways in proteins. Science 367, 76–79 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y., Fried S. D., Boxer S. G., Dissecting proton delocalization in an enzyme’s hydrogen bond network with unnatural amino acids. Biochemistry 54, 7110–7119 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamm P., et al. , Subpicosecond emission studies of bacterial reaction centers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1142, 99–105 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu J., van Stokkum I. H. M., Paparelli L., Jones M. R., Groot M. L., Early bacteriopheophytin reduction in charge separation in reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biophys. J. 104, 2493–2502 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Stokkum I. H. M., Larsen D. S., van Grondelle R., Global and target analysis of time-resolved spectra. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1657, 82–104 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faries K. M., et al. , Manipulating the energetics and rates of electron transfer in Rhodobacter capsulatus reaction centers with asymmetric pigment content. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 6989–7004 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huppman P., et al. , Kinetics, energetics, and electronic coupling of the primary electron transfer reactions in mutated reaction centers of Blastochloris viridis. Biophys. J. 82, 3186–3197 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirmaier C., et al. , Comparison of M-side electron transfer in Rb. sphaeroides and Rb. capsulatus reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 1799–1808 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fajer J., Borg D. C., Forman A., Dolphin D., Felton R. H., Anion radical of bacteriochlorophyll. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 2739–2741 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fajer J., Brune D. C., Davis M. S., Forman A., Spaulding L. D., Primary charge separation in bacterial photosynthesis: Oxidized chlorophylls and reduced pheophytin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 4956–4960 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zabelin A. A., Khristin A. M., Shkuropatova V. A., Khatypov R. A., Shkuropatov A. Y., Primary electron transfer in Rhodobacter sphaeroides R-26 reaction centers under dehydration conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1861, 148238 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulson B. P., Miller J. R., Gan W.-X., Closs G., Superexchange and sequential mechanisms in charge transfer with a mediating state between the donor and acceptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4860–4868 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kondo T., et al. , Cryogenic single-molecule spectroscopy of the primary electron acceptor in the photosynthetic reaction center. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 3980–3986 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sumi H., Kakitani T., Unified theory on rates for electron transfer mediated by a midway molecule, bridging between superexchange and sequential processes. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 9603–9622 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saito K., Sumi H., Unified expression for the rate constant of the bridged electron transfer derived by renormalization. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 134101 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou H., Boxer S. G., Probing excited-state electron transfer by resonance stark spectroscopy. 1. Experimental results for photosynthetic reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 9139–9147 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou H., Boxer S. G., Probing excited-state electron transfer by resonance stark spectroscopy. 2. Theory and application. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 9148–9160 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Treynor T. P., Boxer S. G., Probing excited-state electron transfer by resonance stark spectroscopy: 3. Theoretical foundations and practical applications. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 13513–13522 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treynor T. P., Yoshina-Ishii C., Boxer S. G., Probing excited-state electron transfer by resonance stark spectroscopy: 4. Mutations near BL in photosynthetic reaction centers perturb multiple factors that affect BL*→BL+HL–. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 13523–13535 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lao K., Moore L. J., Zhou H., Boxer S. G., Higher-order stark spectroscopy: Polarizability of photosynthetic pigments. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 496–500 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boxer S. G., Stark realities. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 2972–2983 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gouterman M., “Optical spectra and electronic structure of porphyrins and related rings” in The Porphyrins, Dolphin D., Ed. (Academic Press, 1978), pp. 1–165. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Warshel A., Sharma P., Kato M., Parson W., Modeling electrostatic effects in proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1764, 1647–1676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schmidt S., et al. , Primary electron-transfer dynamics in modified bacterial reaction centers containing pheophytin-a instead of bacteriopheophytin-a. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 51, 1565–1578 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lauterwasser C., Finkele U., Scheer H., Zinth W., Temperature dependence of the primary electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Chem. Phys. Lett. 183, 471–477 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saggu M., Levinson N. M., Boxer S. G., Experimental quantification of electrostatics in X-H···π hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18986–18997 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughes J. M., Hutter M. C., Reimers J. R., Hush N. S., Modeling the bacterial photosynthetic reaction center. 4. The structural, electrochemical, and hydrogen-bonding properties of 22 mutants of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8550–8563 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tharp J. M., Wang Y. S., Lee Y. J., Yang Y., Liu W. R., Genetic incorporation of seven ortho-substituted phenylalanine derivatives. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 884–890 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jha S. K., Ji M., Gaffney K. J., Boxer S. G., Direct measurement of the protein response to an electrostatic perturbation that mimics the catalytic cycle in ketosteroid isomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16612–16617 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blankenburg L., et al. , Following local light-induced structure changes and dynamics of the photoreceptor PYP with the thiocyanate IR label. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 6622–6634 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allen J. P., Williams J. C., Relationship between the oxidation potential of the bacteriochlorophyll dimer and electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 27, 275–283 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coleman W. J., Bylina E. J., Youvan D. C., “Reconstitution of photochemical activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus reaction centers containing mutations at tryptophan M-250 in the primary quinone binding site” in Current Research in Photosynthesis: Proceedings of the VIIIth International Conference on Photosynthesis, Stockholm, Sweden, August 6–11, 1989, Baltscheffsky M., Ed. (Springer Netherlands, 1990), pp. 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J., Ding T., Wu K., Coulomb barrier for sequential two-electron transfer in a nano-engineered photocatalyst.J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13934–13940 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crisenza G. E. M., Mazzarella D., Melchiorre P., Synthetic methods driven by the photoactivity of electron donor-acceptor complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5461–5476 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Proppe A. H., et al. , Bioinspiration in light harvesting and catalysis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 828–846 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biegasiewicz K. F., et al. , Photoexcitation of flavoenzymes enables a stereoselective radical cyclization. Science 364, 1166–1169 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heyes D. J., et al. , Photochemical mechanism of light-driven fatty acid photodecarboxylase. ACS Catal. 10, 6691–6696 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jun D., Saer R. G., Madden J. D., Beatty J. T., Use of new strains of Rhodobacter sphaeroides and a modified simple culture medium to increase yield and facilitate purification of the reaction centre. Photosynth. Res. 120, 197–205 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Russi S., et al. , Inducing phase changes in crystals of macromolecules: Status and perspectives for controlled crystal dehydration. J. Struct. Biol. 175, 236–243 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.I. I. Mathews, J. Weaver, S. G. Boxer, Crystal structure of R. sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Center variant; Y(M210)3-nitrotyrosine. The Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7MH9. Deposited 14 April 2021.

- 82.I. I. Mathews, J. Weaver, S. G. Boxer, Crystal structure of R. sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Center variant; Y(M210)3-methyltyrosine. The Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7MH8. Deposited 14 April 2021.

- 83.I. I. Mathews, J. Weaver, S. G. Boxer, Crystal structure of R. sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Center variant; Y(M210)3-chlorotyrosine. The Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7MH3. Deposited 14 April 2021.

- 84.I. I. Mathews, J. Weaver, S. G. Boxer, Crystal structure of R. sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Center variant; Y(M210)3-bromotyrosine. The Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7MH4. Deposited 14 April 2021.

- 85.I. I. Mathews, J. Weaver, S. G. Boxer, Crystal structure of R. sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Center variant; Y(M210)3-iodotyrosine. The Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7MH5. Deposited 14 April 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

X-ray crystal structures have been deposited in the PDB [7MH9 (81), 7MH8 (82), 7MH3 (83), 7MH4 (84), and 7MH5 (85)]. All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.