Objective

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in high-income countries, and most cases arise from a precursor lesion, endometrial hyperplasia. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many professional bodies advised a suspension in gynecologic services, except for urgent care,1 , 2 to reduce COVID-19 transmission and optimize limited human and physical resources. In the United Kingdom, remote management of abnormal uterine bleeding, the major presenting symptom of endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia, was recommended, with referral to secondary care only in urgent cases.2 This contradicted the established Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ guidelines, which advised hysteroscopy and/or endometrial biopsy within 4 weeks for diagnosis of suspected endometrial hyperplasia or cancer.3 We described the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pathologic diagnoses of endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia within population-based databases in Northern Ireland.

Study Design

The Northern Ireland Cancer Registry is a population-based register covering 1.9 million inhabitants.4 Electronic pathology reports were used to identify unique patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer or endometrial hyperplasia between March 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020 (the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic when “lockdown” was introduced at various times). Data were compared with the average number of histopathologically confirmed cases during the same months between 2017 and 2019. Further information is available in the Supplemental Methods.

Results

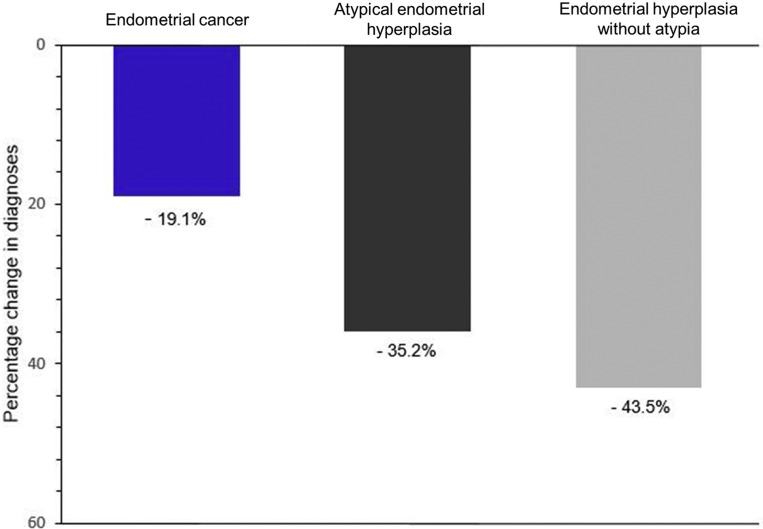

The number of endometrial cancer diagnoses declined by 19.1% between March 2020 and December 2020 compared with the equivalent months from 2017 to 2019 (Figure ). There was some evidence of recovery in winter months, with diagnoses in October and November returning to expected levels (Supplemental Figure). Overall, 70 fewer endometrial cancer cases than expected were diagnosed from March 2020 to December 2020.

Figure.

Percentage change in the diagnoses of endometrial cancer, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial hyperplasia without atypia

The figure shows the percentage decline in endometrial cancer, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial hyperplasia without atypia diagnoses for the period of March 2020 to December 2020 compared with the 3-year average during the same months between 2017 and 2019.

Wylie. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnoses of endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

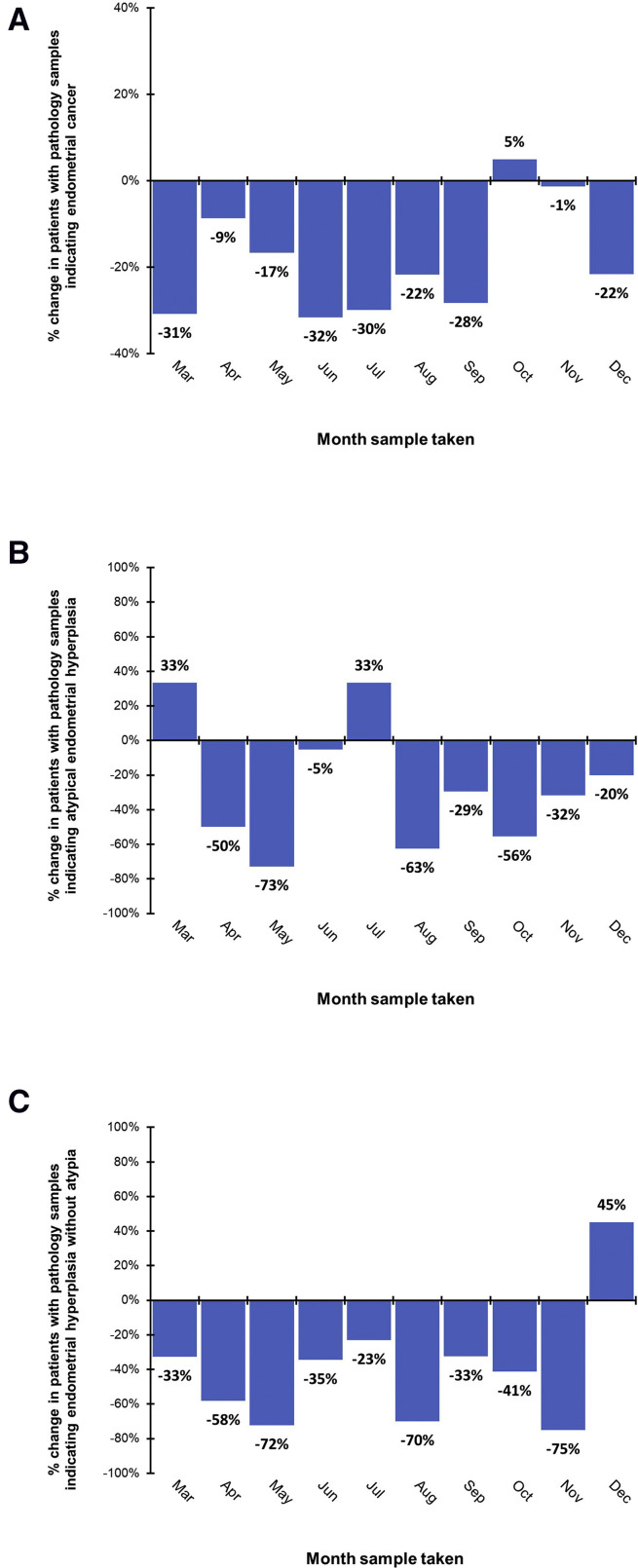

Supplemental Figure.

Percentage change in the monthly diagnoses of endometrial cancer, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial hyperplasia without atypia

The figures show the percentage decline in (A) endometrial cancer, (B) atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and (C) endometrial hyperplasia without atypia diagnoses per month in 2020 compared with the monthly average in 2017–2019.

Wylie. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnoses of endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

The number of atypical hyperplasia and hyperplasia without atypia diagnoses declined by 35.2% and 43.5%, respectively, compared with the data from 2017 to 2019 (Figure). Data were limited to indicate recovery in winter months (Supplemental Figure). There were 40 and 20 fewer cases of hyperplasia without atypia and atypical hyperplasia, respectively, than expected between March 2020 and December 2020.

Conclusion

We demonstrated a marked reduction in pathologic diagnoses of endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia during the first 10 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although endometrial cancer diagnoses showed signs of recovery, endometrial hyperplasia diagnosis continued to lag behind expected rates, likely because of the reprioritization of gynecologic services.3

Similar to our study, a Northern California investigation observed a 35% reduction in pathologic diagnoses of endometrial cancer during the first 12 weeks of the pandemic compared with 2019 levels.5 To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to quantify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population-based pathologic endometrial hyperplasia diagnoses. However, some caution is required on identification of unique patients and data stability because of the use of pathologic Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine code diagnoses. Therefore, we may be underestimating absolute case numbers; however, the proportional decline in diagnoses likely remains the same.

With the transitions in the COVID-19 pandemic, innovative organization of gynecologic investigative and surgical services is necessary to ensure timely diagnoses of cancer and premalignant conditions. This will be especially relevant in future potential “lockdowns.”

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This research has been conducted using data from the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry (NICR), which is funded by the Public Health Agency, Northern Ireland. However, the interpretation and conclusions of the data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the contribution of the NICR staff in the production of the NICR data. Similar to all cancer registries, our work used data provided by patients and collected by the health service as part of their care and support.

U.C.M. is supported by a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship (grant number MR/T019859/1). H.G.C. is supported by Cancer Research UK (grant number C37703/A25820).

Supplemental Methods

The Northern Ireland Cancer Registry

The Northern Ireland Cancer Registry (NICR) is a population-based register covering approximately 1.9 million inhabitants and is the officially recognized provider of cancer statistics for Northern Ireland. The NICR has demonstrated robust validity against key performance indicators of high-quality cancer registration.1 The NICR has collected information on all patients diagnosed with cancer and certain premalignant conditions in Northern Ireland since 1993. Ethical approval for the NICR databases, including the waiving of requirement for individual patient consent, was granted by the Office for Research Ethics Committees of Northern Ireland (reference number 20/NI/0132).

Endometrial cancer diagnoses

Electronic pathology reports were received by the NICR and used to identify all unique patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer (corresponding to International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision, codes C54 and C55) and histopathologically confirmed between March 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, in Northern Ireland. These data were compared with the 3-year average number of patients with a pathologic diagnosis of endometrial cancer during the same period between 2017 and 2019.

Endometrial hyperplasia diagnoses

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine codes were used to identify patients with endometrial hyperplasia diagnoses in Northern Ireland between March 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, and the same period for the years 2017–2019. Location codes T83000 (uterus, not otherwise specified [NOS]), T83200 (cervix uteri, NOS), T83240 (endocervix), T83400 (endometrium), and T83600 (myometrium) were used in combination with morphology codes M72000 (hyperplasia, NOS) and M72005 (atypical hyperplasia, NOS), as advised by an expert gynecologic histopathologist (W.G.M.). Endometrial hyperplasia was classified as either hyperplasia without atypia or atypical hyperplasia according to the 2014 World Health Organization classification of endometrial hyperplasia based on the criteria suggested by Kurman and Norris.2

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions over time) were presented for the number of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer, atypical hyperplasia, and hyperplasia without atypia in Northern Ireland between March 2020 and December 2020, respectively. Comparisons were made to the same monthly range for 2017–2019, for which a 3-year average was estimated.

References

- 1.Thomas V., Maillard C., Barnard A., et al. International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE) guidelines and recommendations on gynecological endoscopy during the evolutionary phases of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy, British Gynaecological Cancer Society Joint RCOG, BSGE and BGCS guidance for the management of abnormal uterine bleeding in the evolving coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2020. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-05-21-joint-rcog-bsge-bgcs-guidance-for-management-of-abnormal-uterine-bleeding-aub-in-the-evolving-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-updated-final-180520.pdf Available at: Accessed September 16, 2021.

- 3.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Restoration and recovery: priorities for obstetrics and gynaecology. A prioritisation framework for care in response to COVID-19. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2021. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2021-04-20-restoration-and-recovery---priorities-for-obstetrics-and-gynaecology.pdf Available at: Accessed September 16, 2021.

- 4.Kearney T.M., Donnelly C., Kelly J.M., O’Callaghan E.P., Fox C.R., Gavin A.T. Validation of the completeness and accuracy of the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh-Burgmann E.J., Alavi M., Schmittdiel J. Endometrial cancer detection during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:842–843. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplemental References

- 1.Kearney T.M., Donnelly C., Kelly J.M., O’Callaghan E.P., Fox C.R., Gavin A.T. Validation of the completeness and accuracy of the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurman R.J., Norris H.J. Evaluation of criteria for distinguishing atypical endometrial hyperplasia from well-differentiated carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;49:2547–2559. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820615)49:12<2547::aid-cncr2820491224>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]