Abstract

Background

Teachers are central to school-associated transmission networks, but little is known about their behavioral patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 700 North Carolina public school teachers in 4 districts open to in-person learning in November-December 2020 (pre-COVID-19 vaccines). We assessed indoor and outdoor time spent, numbers of people encountered at <6 feet (“close contacts”), and mask use by teachers and those around them at specific locations on the most recent weekday and weekend day.

Results

Nearly all respondents reported indoor time at home (98%) and school (94%) on the most recent weekday, while 62% reported indoor time at stores, 18% at someone else's home, and 17% at bars/restaurants. Responses were similar for the most recent weekend day, excepting school (where 5% reported indoor time). Most teachers (>94%) reported wearing masks inside school, stores, and salons; intermediate percentages (∼50%-85%) inside places of worship, bars/restaurants, and recreational settings; and few (<25%) in their or others’ homes. Approximately half reported daily close contact with students.

Conclusions

As schools reopened in the COVID-19 pandemic, potential transmission opportunities arose through close contacts within and outside of school, along with suboptimal mask use by teachers and/or those around them. Our granular estimates underscore the importance of multilayered mitigation strategies and can inform interventions and mathematical models addressing school-associated transmission.

Key Words: Transmission, Mixing, SARS-CoV-2, Modeling, Coronavirus, Behavior

BACKGROUND

Primary and secondary schools perform essential functions in the United States (US), providing educational, social, nutritional, and mental health services to millions of children.1, 2, 3 The importance of these services, coupled with childcare challenges and internet connectivity issues associated with remote learning,4 , 5 have made extended school closures amidst the COVID-19 pandemic a matter of great concern.4 , 6 Reopening schools has carried its own challenges: schools bring large numbers of people into confined spaces for prolonged periods, providing ample opportunity for propagation of respiratory infections. And while young children appear to be minimally susceptible to severe disease caused by SARS-CoV-2,7 , 8 the virus has posed a considerable threat to adult teachers, staff, and administrators,9 particularly as schools reopened in the absence of vaccines.

Tensions between the benefits and dangers of in-person instruction have led to intense scientific and public debate,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 widespread consternation for families,4 , 16 and excruciating decisions for policy makers and administrators.17 Central to these challenges have been uncertainties around the contribution of in-person learning to SARS-CoV-2 transmission, which is a complex function of contact patterns, mitigation measures, and biological determinants of infectiousness and susceptibility. While many scientific efforts have been devoted to the biological aspects of SARS-CoV-2 transmission,18, 19, 20 detailed information on school-related behavioral patterns has been sparse and largely limited to settings outside of the US.21, 22, 23 In particular, little is known about contact patterns and mask use among teachers, despite their importance to school-associated transmission networks. Without detailed information on teachers’ interactions with others, it is difficult to identify optimal intervention approaches, and mathematical models seeking to quantify schools’ transmission contributions will be limited in their ability to generate accurate predictions for informing sound policy.

We sought to address this gap with an in-depth web survey of North Carolina (NC) public school teachers whose districts had opened to in-person learning in the fall of 2020, prior to vaccine availability. We assessed multiple dimensions of teachers’ pandemic-related experiences; here we focus on describing mask use and contact patterns – that is, where and with whom teachers spent time – within and outside of school.

METHODS

Study context: NC COVID policies

At the start of the academic year in August 2020, NC public schools were permitted to deliver instruction to children in prekindergarten through grade 12 in 1 of 2 modes: fully remote learning or a “moderate social distancing” approach that limited density to ≤50% of maximum occupancy and required distancing of 6 feet in school facilities and vehicles.24 , 25 Decisions about which mode to adopt were at the discretion of individual school districts. Beginning October 5, 2020, allowable options expanded to include a “minimal social distancing” approach that lifted density restrictions for students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

In the broader community, a statewide mandate in place at the start of school required that face coverings be worn in all indoor and outdoor settings when distancing was not possible; as of November 25, 2020, this mandate was strengthened to require face coverings in all indoor settings, regardless of distancing.26 In school settings, face coverings were required both indoors and outdoors (regardless of distancing) as of October 8, 2020.

Survey recruitment

In October-November 2020, we introduced our teacher survey to NC public school superintendents attending health and safety videoconferences hosted by the ABC Science Collaborative.27 Districts delivering any in-person instruction by mid-October (76/115 total districts, not all of which were represented at ABC meetings) were eligible for survey participation. In the 4 eligible districts where superintendents granted permission for teacher recruitment before the end of the survey launch window (November 23 - December 7, 2020), we sent individual recruitment emails to all kindergarten through grade 12 (K-12) teachers to invite participation. The UNC-Chapel Hill IRB exempted this study from oversight.

Data collection

Our web-based survey covered 6 domains: (1) socio-demographics, household characteristics, and conditions associated with high risk for severe COVID-19; (2) teaching settings and schedules; (3) contact patterns and mask use within and outside of school; (4) preparation for returning to school; (5) school-based mitigation measures; and (6) COVID-19 testing and exposures. In this report, we focus on the first 3 domains, the questions from which are provided as supplemental material. Participants were asked to complete the 1-time survey by December 14, 2020. All participants provided informed consent, and those completing the survey were offered a $50 prepaid debit card.

Socio-demographic items were participant age, gender, race, Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, highest degree, years of teaching, and current employment beyond teaching. Household characteristics included the number of bedrooms in the primary residence, number of other household members, primary residence type, and whether any household members (including the participant) had regular contact with persons living or working in setting types associated with COVID-19 outbreaks (specifically, nursing homes or long-term care facilities, correctional facilities, or meat-packing plants). We also listed the specific conditions identified by CDC as being associated with high risk for severe COVID-19,28 and we asked participants whether they or (separately) a household member were ≥65 years old or currently had any of the high-risk conditions.

In the “teaching settings and schedules” domain, we first asked participants whether they were teaching any in-person classes. Those affirming were then asked how often they were within 6 feet of a staff member or (separately) student for >15 minutes throughout the day (never, approximately once per month, approximately once per week, a few times per week, approximately once per day, or multiple times per day). We also asked about the numbers of in-person hours and students they were teaching, as well as questions about any in-person extracurricular activities they were leading.

In the “contact patterns and mask use” domain, we asked teachers how much time (to the nearest quarter-hour) they had spent indoors and (separately) outdoors on the most recent weekday and (separately) weekend day at each of the following locations: their home, someone else's home, a school, store, place of worship, bar or restaurant, recreational setting, salon, or “other” setting. For each location where they reported spending ≥15 minutes on a given day, we asked participants to report (separately for indoors vs outdoors) the percentage of time they wore a mask and the percentage of those around them who wore a mask. We also asked how many people in specific age ranges (0-10, 11-17, 18-49, 50-64, and ≥65 years) they encountered at <6 feet for each location where they reported spending ≥15 minutes on a given day.

Statistical analyses

We first conducted descriptive analyses of participant and household characteristics, as well as participants’ teaching settings and schedules, both overall and by school level (elementary, middle, high school). We then described 3 main facets of teacher behavioral patterns: time spent at different locations, mask use by teachers and surrounding persons, and mixing with people of different ages. For the first 2 facets (time spent and mask use), we analyzed responses according to day type (weekday vs weekend), location (home, other home, school, store, place of worship, bar/restaurant, recreational setting, salon, other), and indoor vs outdoor setting. For the third facet (mixing), we analyzed responses according only to day type and location, as questions about age mixing did not differentiate between indoor and outdoor settings.

To determine whether demographic or household features were associated with indoor time and mask use at locations other than home and school (ie, more “discretionary” settings), we used linear regression to calculate differences in 2 outcomes at 6 specific locations (someone else's home, store, place of worship, bar/restaurant, recreational setting, salon) according to teacher characteristics. The first outcome of interest was total indoor time spent at a given location on the most recent weekday and weekend day, calculated as the sum across days. The second was the percentage of time wearing a mask while indoors at a given location on the most recent weekday and/or weekend day, taken as the single reported mask-use value if a teacher reported spending time at a given location on only 1 day, or the mean across days if a teacher reported indoor time at a given location on both days. The characteristics we assessed were age (≥median of 41 years vs <median), race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic vs Hispanic and/or non-White), gender (female vs male), education (highest degree >bachelor's vs bachelor's), living situation (lives alone vs with others), high-risk condition in the teacher (yes/no), and high-risk condition in another household member (yes/no).

RESULTS

The 4 participating districts were located across the 3 main NC regions, with Districts “A” and “D” in the Piedmont (central) region, District “C” in the Coastal (eastern) region, and District “B” in the Western region. Student population size and demographics varied across districts (Supplemental Table S1), with <1,000 students in District C and >20,000 in District A.

Of the 2,414 total K-12 teachers in the 4 districts, 700 completed the survey before the closing date: 407 in District A, 56 in District B, 31 in District C, and 206 in District D (response rate = 29% overall, 25%-36% across districts). Most participants were White (90%) and female (80%) (Table 1 ); participant race and gender aligned closely with aggregate data for the full teaching populations in each district (cf. Supplemental Tables S2 and S3). Median age was 41 years, median teaching experience was 12 years, and most participants listed a bachelor's (57%) or master's (41%) degree as their highest education level. Nearly 20% reported outside employment, and 47% indicated having a condition associated with severe COVID-19 risk. Participant demographics were largely similar across school levels, although high school teachers were slightly older than elementary school teachers, the proportion of male teachers increased sharply with school level, the proportion of White teachers was lowest among high school teachers, and elementary school teachers were less likely than both middle and high school teachers to report outside employment.

Table 1.

Participant socio-demographics and household characteristics, overall and by school level

| Characteristic | Overall N = 700 | Elementary N = 288 | Middle N = 181 | High N = 230 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics* | ||||

| Median (IQR) age | 41 (33, 50) | 40 (32, 49)‡ | 41 (32, 50) | 44 (34, 52) |

| Median (IQR) years of teaching | 12 (6, 20) | 12 (6, 20) | 12 (6, 20) | 12 (7, 20) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Male | 138 (19.7%) | 15 (5.2%)†,‡ | 36 (19.9%)§ | 87 (37.8%) |

| Female | 559 (79.9%) | 273 (94.8%) | 145 (80.1%) | 140 (60.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 633 (90.4%) | 268 (93.1%)‡ | 169 (93.4%)§ | 195 (84.8%) |

| Black | 33 (4.7%) | 10 (3.5%) | 6 (3.3%) | 17 (7.4%) |

| American Indian / Alaskan Native | 5 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Asian | 4 (0.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Other or multiple | 25 (3.6%) | 6 (2.1%) | 5 (2.8%) | 14 (6.1%) |

| Hispanic or Latino/Latina/Latinx | ||||

| Yes | 19 (2.7%) | 8 (2.8%) | 4 (2.2%) | 7 (3.1%) |

| No | 676 (96.7%) | 280 (97.2%) | 176 (97.2%) | 219 (95.6%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Highest degree | ||||

| Bachelor's | 396 (56.6%) | 164 (56.9%) | 100 (55.3%) | 131 (57.0%) |

| Master's | 290 (41.4%) | 124 (43.1%) | 80 (44.2%) | 86 (37.4%) |

| Doctorate | 8 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%)‡ | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (3.0%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (2.6%) |

| Employment outside of teaching | ||||

| Yes | 124 (17.7%) | 32 (11.1%)†,‡ | 33 (18.2%) | 58 (25.3%) |

| No | 565 (80.8%) | 254 (88.2%) | 145 (80.1%) | 166 (72.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 11 (1.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | 3 (1.7%) | 5 (2.2%) |

| High-risk condition¶ | ||||

| Yes | 326 (46.6%) | 126 (43.8%) | 89 (49.2%) | 110 (47.8%) |

| No | 361 (51.6%) | 156 (54.2%) | 88 (48.6%) | 117 (50.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 13 (1.9%) | 6 (2.1%) | 4 (2.2%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Household characteristics* | ||||

| Median (IQR) bedrooms in primary residence | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3,4) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) |

| Number of other household members║ | ||||

| 0 | 45 (6.4%) | 17 (5.9%) | 15 (8.3%) | 13 (5.7%) |

| 1 | 191 (27.3%) | 65 (22.6%) | 54 (29.8%) | 72 (31.3%) |

| 2 | 147 (21.0%) | 64 (22.2%) | 34 (18.8%) | 49 (21.3%) |

| 3 | 194 (27.7%) | 87 (30.2%) | 49 (27.1%) | 57 (24.8%) |

| 4 | 83 (11.9%) | 40 (13.9%) | 15 (8.3%) | 28 (12.2%) |

| ≥5 | 29 (4.1%) | 11 (3.8%) | 10 (5.5%) | 8 (3.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 11 (1.6%) | 4 (1.4%) | 4 (2.2%) | 3 (1.3%) |

| Primary residence type | ||||

| Single-family home | 587 (83.9%) | 243 (84.4%) | 143 (79.0%) | 200 (87.0%) |

| Apartment or condominium | 57 (8.1%) | 26 (9.0%) | 16 (8.8%) | 15 (6.5%) |

| Mobile or manufactured home | 38 (5.4%) | 14 (4.9%) | 16 (8.8%) | 8 (3.5%) |

| Two-family house/duplex | 10 (1.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 4 (2.2%) | 4 (1.7%) |

| Other | 5 (0.7%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (0.9%) |

| Regular contact with persons living or working in: | ||||

| Nursing home/long-term care facility | 22 (3.1%) | 13 (4.5%) | 3 (1.7%) | 6 (2.6%) |

| Correctional facility | 10 (1.4%) | 1 (0.4%)‡ | 2 (1.1%) | 7 (3.0%) |

| Meat-packing plant | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (0.9%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (0.9%) |

| Household member with high-risk condition¶ | ||||

| Yes | 296 (42.3%) | 122 (42.4%) | 71 (39.2%) | 102 (44.4%) |

| No (includes teachers living alone) | 378 (54.0%) | 155 (53.8%) | 100 (55.3%) | 123 (53.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 26 (3.7%) | 11 (3.8%) | 10 (5.5%) | 5 (2.2%) |

Medians compared by Wilcoxon rank sum test; comparison of dichotomous variables by Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

IQR, interquartile range.

Presented as n (%) except where otherwise indicated.

P < .05 for elementary vs middle.

P < .05 for elementary vs high.

P < .05 for middle vs high.

P < .05 for elementary vs middle and for elementary vs high for having ≥2 vs 0 or 1 other household members.

Specified in survey as any of the following: cancer; chronic kidney disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; heart conditions, such as heart failure, coronary artery disease, or cardiomyopathies; immunocompromised state from solid organ transplant, blood or bone marrow transplant, immune deficiencies, HIV, or use of corticosteriods or other immune weakening medicines; obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2); sickle cell disease; smoking; diabetes mellitus; moderate to severe asthma; cerebrovascular disease; cystic fibrosis; hypertension; neurological conditions, such as dementia; liver disease; overweight (25<BMI<30 kg/m2); pulmonary fibrosis; pregnancy; or thalassemia.

Most participants (84%) reported residing in a single-family home, the median number of bedrooms was 3, and most respondents reported sharing households with 1 (27%), 2 (21%), or 3 (28%) other people; only 6% reported living alone (Table 1). Few participants (<5%) reported that they or another household member had regular contact with persons living or working in setting types associated with COVID-19 outbreaks, and 42% reported that a household member had a condition associated with severe COVID-19 risk. An elevated proportion (74%) of District C participants reported a household member at high risk of severe disease (Supplemental Table S3), but most other household characteristics were similar across districts and school levels.

Teaching settings and schedules

Most teachers (87%) reported that they were teaching in person (Table 2 ). Of the 13% not teaching in person, 64% reported that they were assigned to remote teaching, 12% reported that they opted to teach remotely, and 24% reported other reasons (eg, maternity or medical leave) for not teaching in person. Middle school teachers were slightly more likely (95%) than elementary (84%) or high school (84%) teachers to be teaching in person. Of those teaching in person, ∼60% reported being within 6 feet of another staff member for >15 minutes at least once a week; 23% reported such contact multiple times a day. Nearly half (45%) reported being within 6 feet of a student for >15 minutes multiple times a day. Numbers of students seen per day and per week varied by school level (Table 2) and district (Supplemental Table S4). Nine percent reported in-person engagement in extracurriculars; this percentage increased from 3% in elementary teachers to 18% in high school teachers.

Table 2.

Participant teaching patterns, overall and by school level

| Characteristic* | Overall N = 700 | Elementary N = 288 | Middle N = 181 | High N = 230 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching in person | ||||

| Yes | 609 (87.0%) | 242 (84.0%)† | 172 (95.0%)§ | 194 (84.4%) |

| No | 86 (12.3%) | 45 (15.6%) | 9 (5.0%) | 32 (13.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.7%) |

| Within 6 feet of staff member >15 min/d#,‖ | ||||

| Never | 205 (33.7%) | 78 (32.2%) | 53 (30.8%) | 73 (37.6%) |

| Approximately once a month | 29 (4.8%) | 11 (4.6%) | 6 (3.5%) | 12 (6.2%) |

| Approximately once a week | 64 (10.5%) | 16 (6.6%) | 23 (13.4%) | 25 (12.9%) |

| A few times a week | 82 (13.5%) | 29 (12.0%) | 24 (14.0%) | 29 (15.0%) |

| Approximately once a day | 78 (12.8%) | 38 (15.7%) | 19 (11.1%) | 21 (10.8%) |

| Multiple times a day | 140 (23.0%) | 67 (27.7%) | 41 (23.8%) | 32 (16.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 11 (1.8%) | 3 (1.2%) | 6 (3.5%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Within 6 feet of student >15 min/d#,¶ | ||||

| Never | 164 (26.9%) | 49 (20.3%) | 55 (32.0%) | 59 (30.4%) |

| Approximately once a month | 16 (2.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | 4 (2.3%) | 8 (4.1%) |

| Approximately once a week | 35 (5.8%) | 8 (3.3%) | 9 (5.2%) | 18 (9.3%) |

| A few times a week | 73 (12.0%) | 12 (5.0%) | 22 (12.8%) | 39 (20.1%) |

| Approximately once a day | 38 (6.2%) | 14 (5.8%) | 14 (8.1%) | 10 (5.2%) |

| Multiple times a day | 273 (44.8%) | 150 (62.0%) | 65 (37.8%) | 58 (29.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 10 (1.6%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (1.7%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| In-person coaching or extracurriculars | ||||

| Yes | 63 (9.0%) | 8 (2.8%)†,‡ | 13 (7.2%)§ | 42 (18.3%) |

| No | 636 (90.9%) | 280 (97.2%) | 168 (92.8%) | 187 (81.3%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| In-person h/wk, averaged over last 4 wk# | 21 (10, 30) | 28 (14, 34)†,‡ | 24 (12, 30)§ | 16 (6, 26) |

| Maximum students in room at once# | 15 (12, 17) | 16 (12, 19)†,‡ | 15 (13, 16)§ | 13 (10, 15) |

| Maximum students seen per day# | 24 (15, 40) | 18 (14, 30)† | 43 (30, 55)§ | 21 (13, 31) |

| Individual students seen per week# | 38 (18, 75) | 18 (15, 37)†,‡ | 80 (60, 105)§ | 30 (18, 50) |

Comparison of medians by Wilcoxon rank sum test; comparison of dichotomous variables by Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

P < .05 for elementary vs middle.

P < .05 for elementary vs high.

P < .05 for middle vs high.

P < .05 for elementary vs high for having at least daily contact with another staff member at ≤6 feet for >15 minutes.

P < .05 for elementary vs middle, elementary vs high, and middle vs high for having at least daily contact with a student at ≤6 feet for >15 minutes.

Among participants teaching in person.

Weekday and weekend locations and time spent

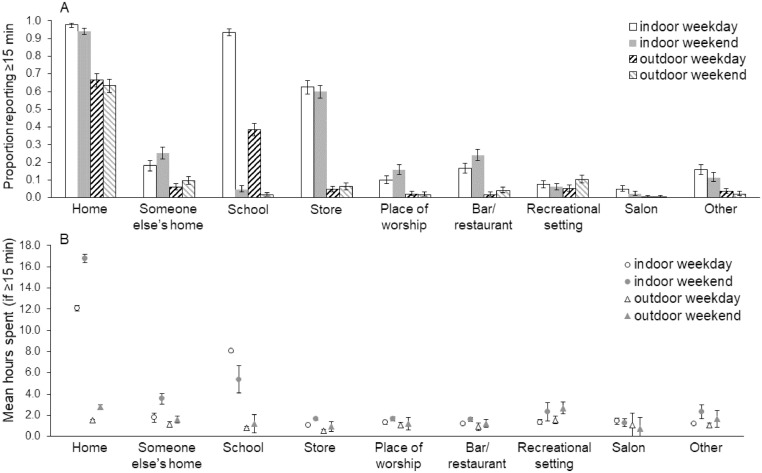

Nearly all teachers reported spending ≥15 minutes indoors at home (98%) and at school (94%) on the most recent weekday (Fig 1 A); a similar proportion reported indoor time at home (but not school) on the most recent weekend day. More than half reported ≥15 minutes indoors at a store on the most recent weekday and weekend day. Approximately 1-quarter reported spending ≥15 minutes indoors at someone else's home and/or at a bar or restaurant on the most recent weekend day, with slightly fewer (∼20%) reporting indoor time in these settings on the most recent weekday. Fewer than 20% reported ≥15 minutes indoors or outdoors at places of worship, recreational settings, salons, or “other” settings (most commonly a car) on both days.

Fig 1.

Teacher time spent by location, day type, and indoor vs outdoor setting. (A) Proportion of teachers reporting ≥15 minutes at specified locations, stratified by day type (most recent weekend day vs most recent weekday) and indoor vs outdoor setting; (B) Among teachers reporting ≥15 minutes at a given location for a specific setting (indoor/outdoor) and day type (weekday/weekend), mean number of hours spent at that location and setting on that day.

Of those spending ≥15 minutes in a given setting on a given day, participants reported the longest indoor durations at home (weekday mean: 12 hours; weekend mean: 17 hours) and at school (weekday mean: 8 hours; weekend mean 5 hours), with considerably less indoor and outdoor time spent (<4 hours) on any given day at all other locations (Fig 1B). Supplemental Figure S1 summarizes time spent by location in the full study population, including participants reporting no time at a given location on a given day. As detailed in Supplemental Table S5, time spent by setting was broadly similar across school levels and districts.

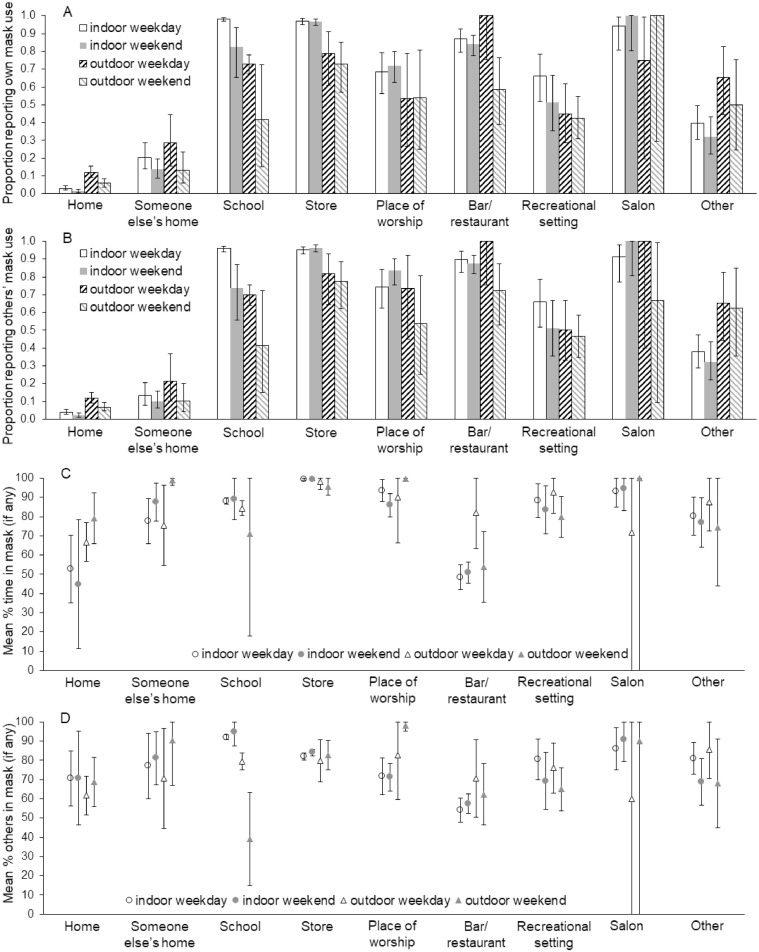

Mask use by teachers and those around them

Among teachers spending ≥15 minutes inside a given location on a given day, >90% reported wearing masks at stores and salons on both the most recent weekday and weekend day, and at school on the most recent weekday (Fig 2 A). Percentages reporting indoor mask use were somewhat lower (∼50%-85%) in bars/restaurants, places of worship, and recreational settings, and much lower in teachers’ (1%-3%) or others’ (14%-20%) homes. Outdoor mask use also varied across settings, with low percentages reporting outdoor mask use at their or others’ homes, and intermediate percentages (∼40%-85%) reporting outdoor mask use at school, stores, places of worship, recreational settings, and “other” settings on both the most recent weekday and weekend day. For most settings, percentages of teachers reporting any mask use by those around them (Fig 2B) were broadly similar to the percentages self-reporting mask use (Fig 2A).

Fig 2.

Mask use by teachers and others by location, day type, and indoor vs outdoor setting. Among teachers reporting ≥15 minutes at a given location for a specific setting (indoor/outdoor) and day type (weekday/weekend), the proportion: (A) self-reporting wearing a mask at that location and setting on that day, and (B) reporting any mask use by others at that location and setting on that day. (C) Among teachers self-reporting any mask use for a given location/day/setting, the reported percentage of time spent in a mask at that location and setting on that day. (D) Among teachers reporting any mask use by others for a given location/day/setting, the reported percentage of others in a mask at that location and setting on that day.

Among those who reported wearing masks inside a given location on a given day, the mean reported percentage of time in a mask was >85% for school, stores, places of worship, and salons on both the most recent weekday and weekend day (Fig 2C), with lower percentages (45%-84%) of indoor time with masks for all other locations on at least 1 day. The mean reported percentage of surrounding people wearing masks indoors was also >85% for school and salons, but only 72% for places of worship (Fig 2D). Both the percentage of time wearing masks and the percentage of surrounding people wearing masks inside bars or restaurants was <60% on the most recent weekday and weekend day.

Supplemental Figures S2-S3 summarize mask use percentages among all those reporting any indoor/outdoor time at a given location on a given day (including those reporting no mask use by themselves or others, respectively, for a given location/setting/day). Supplemental Tables S6-S7 provide mask-related results by school level and district, but sparse data in many strata hinder comparisons. To facilitate use of our survey results in future mathematical modeling efforts, we also provide a downloadable file with numerical values related to time spent and mask use as a supplement to this paper. Additional estimates customized to the needs of specific modeling efforts are available upon request.

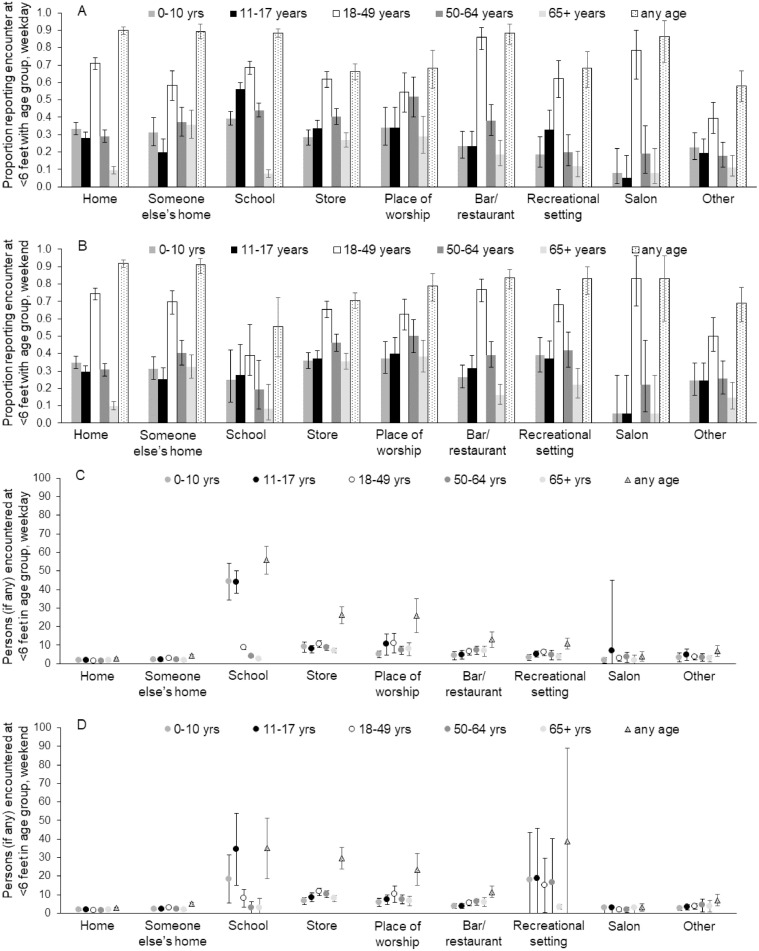

Mixing by age

Proportions of teachers encountering others at <6 feet varied by location and contact age. Among those spending ≥15 minutes at a given location on the most recent weekday, >50% reported encountering at least 1 person ages 18-49 at all but “other” locations (Fig. 3 A). Fewer than 50% reported weekday encounters at <6 feet with persons in younger (0-10, 11-17) and older (50-64, 65+) groups across all locations, with the exception of adults aged 50-64 at a place of worship and children aged 11-17 at school. Findings were broadly similar on weekends for most locations (Fig 3B).

Fig. 3.

Teacher mixing patterns by location, day, and contact age group. Among teachers spending ≥15 minutes at a given location on a given day, the proportion reporting any contact at <6 feet with someone in a specified age group on the most recent: (A) weekday, and (B) weekend day. Among those reporting any contact at <6 feet for a given location/day/age, the number of persons contacted on the most recent: (C) weekday, and (D) weekend day.

Among those reporting weekday contact with any others at a given location, the mean number of total persons contacted was 2-5 for salons and teachers’ or others’ homes; 6-15 for bars/restaurants, recreational settings, and “other” settings; and 25-56 for school, stores, and places of worship (Fig 3C). While the numbers of persons encountered at a given location on a given day were relatively similar across age groups for most locations, teachers reported greater numbers of contacts with persons aged <18 vs ≥18 years in school settings. Results were broadly similar for the most recent weekend day (Fig 3D), although fewer weekend (vs weekday) contacts occurred at school, more weekend (vs weekday) contacts occurred at recreational settings, and estimates were less precise.

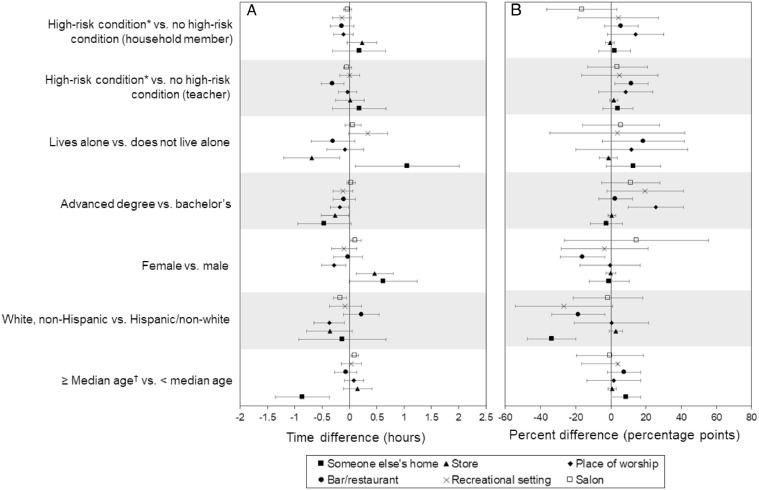

Associations of teacher characteristics with indoor time and mask use

Teacher characteristics varied in their relationships with indoor time and mask use across locations, with most characteristics having only modest (if any) associations with these outcomes at most locations (Fig 4 ). Of note, however, teachers with vs without a high-risk condition spent (on average) less indoor time at bars/restaurants (time difference [TD] = -0.3 hour; 95% confidence interval [CI] = [-0.5, -0.1]) and a greater percentage of that time wearing a mask (absolute percentage difference [PD] = 12 percentage points; 95% CI = [2, 21]). Additionally, teachers living alone spent less indoor time at stores (TD = -0.7 hour; 95% CI = [-1.2, -0.2]) and more at someone else's home (TD = 1.1 hour; 95 CI = [0.1, 2.0]) than did those living with at least 1 other person. Teachers with vs without an advanced degree spent less indoor time at places of worship, stores, and others’ homes, and they reported wearing a mask for a greater percentage of their time inside places of worship (PD = 26 percentage points; 95% CI = [10, 41]). Female vs male teachers spent less indoor time at places of worship (TD = -0.3 hour; 95% CI = [-0.5, -0.1]), but more time at salons (TD = 0.1 hour; 95% CI = [0.02, 0.2]), stores (TD = 0.5 hour; 95% CI = [0.1, 0.8]), and others’ homes (TD = 0.6 hour; 95% CI = [0.0, 1.2]). While there was no difference by gender in indoor time spent in bars/restaurants, females reported wearing a mask for a smaller percentage of their indoor time in these settings (PD = -16 percentage points; 95% CI = [-29, -3]). White, non-Hispanic teachers spent less indoor time at several locations (especially salons, places of worship, and stores) than did Hispanic/non-White teachers, but they reported spending considerably less of their indoor time wearing masks in recreational settings, bars/restaurants, and others’ homes. Finally, teachers at or above the median age of 41 years spent less time than did younger teachers at others’ homes (TD = -0.9 hour; 95% CI = [-1.4, -0.4]), and they reported spending more of their indoor time at these homes in masks (PD = 9 percentage points; 95% CI = [0.2, 17]).

Fig 4.

Relationships between demographic/household characteristics and teacher behaviors. Differences according to selected teacher characteristics in: (A) total indoor hours spent at a given location across the most recent weekday and weekend day, and (B) percentage of indoor time at a given location that the teacher work a mask on the most recent weekday and/or weekend day. *See list of conditions below Table 1. †Median age of survey participants was 41 years.

DISCUSSION

Little systematic attention has been paid to understanding the pandemic-related experiences of public school teachers, despite their centrality to school-related contact networks and mitigation efforts. In this study of 700 K-12 public school teachers in 4 diverse districts across NC, we found that although reported adherence to mask mandates was generally high and teachers’ interactions were largely limited to home and school locations, numerous transmission opportunities may have arisen through regular, close contact with students and other staff, as well as suboptimal mask use by teachers and/or surrounding persons in homes, stores, restaurants/bars, places of worship, and recreational settings. We found that teachers at elevated risk of infection and/or severe disease according to demographic characteristics (eg, older age, Hispanic/non-White ethnicity/race, and comorbidities) adopted some protective behaviors (decreased indoor time and increased mask use at certain locations), and that campaigns to support greater mask-wearing among other groups (eg, White, non-Hispanic teachers) could be beneficial. Taken together, our findings underscore the importance of multilayered mitigation strategies (eg, ventilation, masks, vaccination, isolation, quarantine) within and outside of school settings to reduce the impact of lapses (eg, suboptimal mask adherence) in any single intervention.

In addition to these overall findings, we provide detailed information about teachers’ households, their time spent indoors and outdoors across numerous locations on both the most recent weekday and weekend day, their mask use and observations of others’ mask use, and the numbers of people of various ages encountered across settings. Prior surveys – both before and during the current pandemic – have estimated these types of parameters in broad populations,21, 22, 23 , 29 , 30 providing important stand-alone findings and key inputs for mathematical models. Such models are the main scientific tools for analyzing transmission dynamics, estimating the contributions of hypothesized transmission drivers, and predicting future epidemic trajectories under a range of potential conditions. Several models have focused specifically on school reopenings’ contributions to in-school and community SARS-CoV-2 transmission.31, 32, 33 While the mathematical underpinnings of many such models have been impeccable, little empirical information has been available to closely parameterize teacher contact patterns within them. Our study was designed to address this information gap in one of the most important populations involved in school-associated SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

We note that our cross-sectional survey was conducted at a particular moment in a rapidly evolving pandemic. Reported contact patterns and mask behaviors pertain to a period when SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was unavailable, case rates were increasing, and statewide mandates restricted gatherings and required mask use. Generalizability is further limited by our inclusion of teachers from a small number of school districts in a single state, as well as incomplete participation among eligible teachers. While participants’ demographic characteristics were similar to those of the full NC public teacher workforce, and although our study provides important insights about behavioral patterns during a critical pandemic phase, additional estimates from other locations and time periods will be useful for triangulation and comparison as the pandemic continues to unfold. We also note that survey responses may be subject to social desirability bias, and that some estimates, particularly those relating to outdoor behaviors, were imprecise due to small numbers of participants reporting time at some locations. Finally, as the intent of the current analysis was fully descriptive, we leave multivariable analyses and causal inference around drivers of behavior for subsequent manuscripts.

Despite these limitations, we provide a unique, in-depth description of US teachers’ behavioral patterns at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. We supply detailed quantitative information about teachers’ households, contact rates, mixing patterns, and mask use across locations, reporting the types of estimates that are necessary for developing public health interventions and parameterizing dynamic transmission models. Our results can inform ongoing intervention development and modeling analyses in the current pandemic, as well as future models analyzing schools’ roles in outbreaks of other infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the teachers who participated in our survey, the superintendents who granted us permission to invite teacher participation, the 4 districts’ data and IT managers who facilitated sending of teacher invitation emails, and Dr. Danny Benjamin and the ABC Science Collaborative for facilitating engagement with superintendents. We further thank Tom Leggett and James Peak for quickly and carefully programming the web survey, and Spencer Gee for IT support. We appreciate the exceptional administrative support provided by Lena Hudock and Vicki Moore, as well as Sarah Wackerhagen and Cristina Luna.

Footnotes

Funding/support: This project was supported by the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory (Contract Agreement Number 23-01) with funding from the North Carolina Coronavirus Relief Fund established and appropriated by the North Carolina General Assembly. PT receives research funding from the NIH (NIAID K08AI148607).

Study sponsors had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing of the report, or decision to submit the report for publication.

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.12.020.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.National Center for Education Statistics. Fast facts: back to school statistics. Accessed June 9, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372.

- 2.Love HE, Schlitt J, Soleimanpour S, Panchal N, Behr C. Twenty years of school-based health care growth and expansion. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:755–764. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Department of Agriculture. National School Lunch Program (NSLP) fact sheet. Accessed June 9, 2021. https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp/nslp-fact-sheet.

- 4.Verlenden JV, Pampati S, Rasberry CN, et al. Association of children's mode of school instruction with child and parent experiences and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic – COVID Experiences Survey, United States, October 8 – November 13, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:369–376. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7011a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DigialBridgeK-12. The connectivity challenges schools face with implementing distance learning during COVID-19. Accessed June 9, 2021. https://digitalbridgek12.org/toolkit/the-challenge/school-connectivity-challenges/.

- 6.Levinson M, Cevik M, Lipsitch M. Reopening primary schools during the pandemic. New Engl J Med. 2020;383:981–985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2024920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cevik M, Bamford CGG, Ho A. COVID-19 pandemic – a focused review for clinicians. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 in Children and Teens. Accessed June 10, 2021.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/children/symptoms.html.

- 9.National Education Association. All hands on deck: guidance reopening school buildings. Accessed June 10, 2021. https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/27383%20All%20Hands%20On%20Deck%20Reopening%20Guidance%20Update_Final%2009.2020.pdf.

- 10.Wen LS. Opinion: both sides of the school reopening debate have it wrong. The Washington Post. 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/02/24/both-sides-school-reopening-debate-have-it-wrong/ (Accessed June 10, 2021).

- 11.Esposito S, Principi N. School closure during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an effective intervention at the global level? JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:921–922. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cristakis DA. School reopening – the pandemic issue that is not getting its due. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:928. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Ping I, Chen Y-C. Debates around the role of school closures in the coronavirus 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:107. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng SO, Liu A. Debates around the role of school closures in the coronavirus 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:106. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verd S, López-García M. Debates around the role of school closures in the coronavirus 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:106–107. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Tilburg MAL, Edlynn E, Maddaloni M, van Kempen K, Díaz-González de Ferris M, Thomas J. High levels of stress due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic among parents of children with and without chronic conditions across the USA. Children (Basel) 2020;7:193. doi: 10.3390/children7100193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adolph C, Amano K, Bang-Jensen B, Fullman N, Wilkerson J. Pandemic politics: timing state-level social distancing responses to COVID-19. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2021;46:211–213. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8802162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee LYW, Rozmanowski S, Pang M, Charlett A, Anderson C, Hugest GJ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infectivity by viral load, S gene variants and demographic factors and the utility of lateral flow devices to prevent transmisison. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:407–415. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan D, Zhang X, Chen C, et al. Characteristics of viral shedding time in SARS-CoV-2 infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.652842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madera S, Crawford D, Langelier C, et al. Nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in young children do not differ significantly from those in older children and adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3044. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81934-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sparks RSJ, Aspinall WP, Brooks-Pollock EB, et al. A novel approach for evaluating contact patterns and risk mitigation strategies for COVID-19 in English primary schools with application of structured expert judgment. R Soc Open Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.1098/rsos.201566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Litvinova M, Liang Y, et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368:1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latsuzbaia A, Herold M, Bertemes J-P, Mossong J. Evolving social contact patterns during the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North Carolina Office of the Governor. North Carolina K-12 public schools to require key safety measures to allow in-person instruction. 2020 press release. Accessed June 11, 2021.https://governor.nc.gov/news/north-carolina-k-12-public-schools-require-key-safety-measures-allow-person-instruction

- 25.North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. StrongSchoolsNC Public Health Toolkit (K-12). Interim Guidance as of June 8, 2020.

- 26.North Carolina Office of the Governor. With cases rising rapidly, North Carolina tightens existing mask requirements and enforcement. 2020 press release. Accessed June 11, 2021.https://governor.nc.gov/news/cases-rising-rapidly-north-carolina-tightens-existing-mask-requirements-and-enforcement.

- 27.The ABC Science Collaborative. Accessed August 31, 2021. https://abcsciencecollaborative.org/

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with certain medical conditions. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html.

- 29.Kleynhans J, Tempia S, McMorrow ML, et al. A cross-sectional study measuring contact patterns using diaries in an urban and rural community in South Africa, 2018. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1055. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11136-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mossong J, Hens N, Jit M, et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilinski A, Salomon JA, Giardina J, Ciaranello A, Fitzpatrick MC. Passing the test: a model-based analysis of safe school-reopening strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1090–1100. doi: 10.7326/M21-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Head JR, Andrejko KL, Cheng Q, et al. School closures reduced social mixing of children during COVID-19 with implications for transmission risk and school reopening policies. J R Soc Interface. 2021;18 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2020.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGee RS, Homburger JR, Williams HE, Bergstrom CT, Zhou AY. Model-driven mitigation measures for reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2108909118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.