Abstract

Maladaptation of the sympathetic nervous system contributes to the progression of cardiovascular disease and risk for sudden cardiac death, the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Axonal modulation therapy (AMT) directed at the paravertebral chain blocks sympathetic efferent outflow to the heart and maybe a promising strategy to mitigate excess disease-associated sympathoexcitation. The present work evaluates AMT, directed at the sympathetic chain, in blocking sympathoexcitation using a porcine model. In anesthetized porcine (n = 14), we applied AMT to the right T1-T2 paravertebral chain and performed electrical stimulation of the distal portion of the right sympathetic chain (RSS). RSS-evoked changes in heart rate, contractility, ventricular activation recovery interval (ARI), and norepinephrine release were examined with and without kilohertz frequency alternating current block (KHFAC). To evaluate efficacy of AMT in the setting of sympathectomy, evaluations were performed in the intact state and repeated after left and bilateral sympathectomy. We found strong correlations between AMT intensity and block of sympathetic stimulation-evoked changes in cardiac electrical and mechanical indices (r = 0.83–0.96, effect size d = 1.9–5.7), as well as evidence of sustainability and memory. AMT significantly reduced RSS-evoked left ventricular interstitial norepinephrine release, as well as coronary sinus norepinephrine levels. Moreover, AMT remained efficacious following removal of the left sympathetic chain, with similar mitigation of evoked cardiac changes and reduction of catecholamine release. With growth of neuromodulation, an on-demand or reactionary system for reversible AMT may have therapeutic potential for cardiovascular disease-associated sympathoexcitation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Autonomic imbalance and excess sympathetic activity have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and are targets for existing medical therapy. Neuromodulation may allow for control of sympathetic projections to the heart in an on-demand and reversible manner. This study provides proof-of-concept evidence that axonal modulation therapy (AMT) blocks sympathoexcitation by defining scalability, sustainability, and memory properties of AMT. Moreover, AMT directly reduces release of myocardial norepinephrine, a mediator of arrhythmias and heart failure.

Keywords: autonomic nervous system, nerve block, neurocardiology, neuromodulation, kilohertz frequency alternating current

INTRODUCTION

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), the leading cause of mortality in the United States, is linked to elevated sympathetic activity acting on abnormal cardiac substrates, leading to increased potential for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (1, 2). Maladaptation of the autonomic nervous system has been implicated in various cardiovascular disorders including SCD, congestive heart failure (CHF), and hypertension (3, 4). In both humans and animal models of disease, remodeling of the sympathetic nervous system, including changes in sympathetic nerve density, excitability of the ventricular myocardium, and changes in peripheral ganglia have been described (5–8). Current medical practice to treat cardiovascular diseases focuses on treating the symptoms associated with the disease process, often with pharmacological agents targeted to end effectors, device therapy (e.g., pacemakers), surgery, or focal ablations (9). Although effective in most cases, some pathologies such as refractory ventricular tachycardia, rely on reactive implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices to sustain the patients, treating the symptom, not a root cause of the disease process (3, 9). A number of neuromodulatory approaches have shown efficacy in the management of refractory ventricular tachycardia (VT), although each bears significant limitations (10, 11). Although surgical sympathectomy is efficacious, sympathetic denervation is permanent and associated with several side effects including hyperhidrosis and hyperalgesia (12). Moreover, bilateral therapy, rather than left-sided alone, is commonly necessary for improved freedom from ICD shocks, heart transplantation, or death (11). Sympathetic blockade using thoracic epidural anesthesia or stellate ganglia block has also been used in the management of VT storm with minimal morbidity, but it is temporary and often a bridge to more definitive therapy (13, 14). Targeted bioelectric neuromodulation allows for an alternative path for control of sympathetic projections to the heart that is available on-demand and reversible.

Electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves has been a growing avenue to target maladaptive operation of the nervous system, offering nonpharmacological, scalable, reversible, on-demand therapeutic alternatives facilitated by advances in low-power, smart, and miniaturized bioelectronic implants (4, 15). Although the use of electrical stimulation is well recognized and has multiple clinical applications, the use of bioelectronic approaches to selectively block the conduction of action potentials is a more recent discovery (16–19). This blocking mechanism can be achieved with charge-balanced kilohertz frequency alternating current (KHFAC) with zero net charge delivery, charge-balanced direct current carousel (CBDCC), or a hybrid waveform involving both (20, 21). Mechanistically, conduction block mediated through such axonal modulation therapy (AMT) occurs by producing a region whereby action potentials cannot pass, with several studies suggesting a memory effect whereby nerve conduction is depressed for a period of time after current delivery (19, 22, 23). In porcine models, we have previously demonstrated short-term efficacy of KHFAC in reducing evoked cardiac sympathetic responses when applied to the paravertebral chain (24). Importantly, using CBDCC in swine with chronic myocardial infarction, we found that transient nerve block resulted in reduced ventricular arrhythmia inducibility by programmed ventricular stimulation (25). We and others have further identified critical components of the paravertebral chain as primary inputs for afferent and efferent neurotransmission to the heart, including the stellate and proximal thoracic paravertebral ganglia (26, 27).

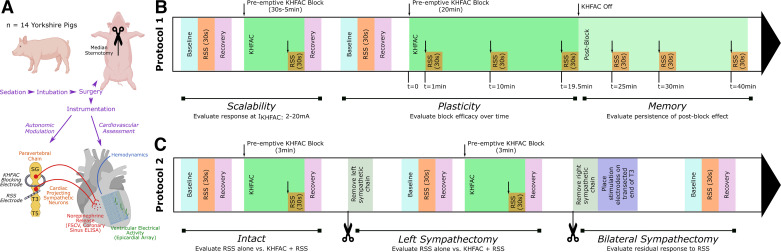

In the current work, we aimed to characterize KHFAC block and evaluate its efficacy in two sets of mechanistic experiments (Fig. 1). First, we studied several features of KHFAC block such as scalability (i.e., relationship between amplitude and block), sustainability/plasticity, and memory (Fig. 1B, protocol 1). We anticipated the presence of a reproducible, dose-response relationship between amplitude and block and the persistence of a partial KHFAC block following cessation of current delivery. Given the increasing clinical relevance of neuromodulation of the bilateral sympathetic chain, in the second set of experiments, we evaluated the efficacy of KHFAC block in the setting of unilateral sympathectomy, and its impact on sympathetic nerve stimulation-induced myocardial neurotransmitter release (Fig. 1C, protocol 2). The primary hypothesis is that KHFAC mitigates sympathoexcitation in a scalable fashion and that KHFAC AMT continues to mitigate sympathoexcitation in the setting of unilateral sympathectomy.

Figure 1.

Study design and methods. A: schematic of autonomic modulation using KHFAC targeted at the right paravertebral chain. KHFAC was applied at the right proximal paravertebral chain to block activation of cardiac-projecting sympathetic neurons, and the right sympathetic chain was stimulated distally using bipolar stimulating electrodes. Cardiac mechanical function, regional cardiac electrical activity, and catecholamine release were evaluated in response to activation of the sympathetic chain using the stimulating electrode, and, subsequently, during combined KHFAC block and sympathetic chain stimulation. B: protocol 1 evaluated scalability of KHFAC by applying KHFAC at varying currents (2–20 mA) during a short KHFAC block. Subsequently, plasticity and memory were evaluated using a 20-min KHFAC block with intermittent RSS. C: protocol 2 evaluated the impact of KHFAC in the intact state and following left and bilateral sympathectomy. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FSCV, fast-scanning cyclic voltammetry; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation; SG, stellate ganglia; T3 and T5, third and fifth sympathetic chain ganglia. Created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

METHODS

Study Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of California, Los Angeles, and is in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. At the end of experiments, animals were euthanized in concordance with IACUC guidelines.

Surgical Preparation

A total of 14 Yorkshire pigs (Sus scrofa, S&S Farms, California) of both sexes (9 males and 5 females), aged 3 ± 1 mo, weighing 36 ± 3 kg, were used for these studies (Fig. 1A).

Yorkshire pigs were sedated with tiletamine-zolazepam (5–6 mg/kg im) and isoflurane (3%–5%, inhaled). Following endotracheal intubation, animals were mechanically ventilated (tidal volume = 300–450 mL, rate = 10–12 breaths per minute), and anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (1%–4%, inhaled). Fentanyl (20–30 µg/kg) was administered for analgesia during surgical preparation. The femoral arteries and veins were cannulated using the modified Seldinger technique, and carotid artery cannulated directly through surgical cutdown, and vascular access sheaths placed. Systemic arterial blood pressure was monitored through the side port of a sheath in the femoral artery, and normal saline (4–6 mL/kg/h) was infused through the femoral vein to replenish insensible fluid losses. Temperature was monitored (rectal or esophageal), and maintained through forced-air warming blankets. Three-lead electrocardiogram and end-tidal carbon dioxide were used to ensure acceptable physiological status for experiments. Arterial blood gas contents were assessed on an hourly basis and adjustments to tidal volume, rate, fraction of inspired oxygen, or administration of sodium bicarbonate were performed as appropriate to maintain physiological levels.

A median sternotomy was performed and the bilateral pleural cavities were entered. The parietal pleura was divided posteriorly, and the right and left paravertebral chain from the stellate (cervicothoracic) ganglia to T3 ganglia were exposed. The pericardium was opened and pericardial cradle was created to support the heart. For studies examining catecholamine release, a catheter was advanced into the coronary sinus via the right external jugular vein for blood sampling. Following completion of surgical preparation, anesthesia was transitioned from isoflurane to α-chloralose (50 mg/kg over 1 h, followed by 25–50 mg/kg/h iv) to minimize the cardiodepressive effects of inhaled anesthetics. For protocol 1, pretreatment with atropine (1 mg/kg iv) or bilateral vagus nerve transection was performed to remove competing effects of parasympathetic efferent responses.

Hemodynamic and Electrophysiological Measurements

A solid-state pressure catheter (Mikro-Tip Model SPR-350, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was guided to the left ventricle through the femoral or carotid artery, and used to continuously measure left ventricular pressure, rate of change of left ventricular pressure (LV dP/dt), and heart rate (HR). These data, as well as a lead II electrocardiogram, were acquired through a Cambridge Electronics Design (Cambridge, UK) acquisition system and computed using Cambridge Electronics Design Spike2 Data Acquisition & Analysis Package (Cambridge, UK).

For the first set of experiments (Fig. 1B, protocol 1), electrophysiological data were acquired using a custom 56-electrode epicardial sock placed over the right and left ventricles. Unipolar local electrograms were recorded at 1,000 Hz using a Prucka CardioLab Acquisition System (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT). For the second set of experiments (Fig. 1C, protocol 2), high-density electrophysiological recordings were acquired using a custom 128-electrode epicardial array (NeuroNexus, Ann Arbor, MI) placed over the anterior left ventricle, with sampling rate at 1,360 Hz through an AlphaLab SnR acquisition system (Alpha Omega, Alpharetta, GA). For both approaches, data were analyzed using ScalDyn 5 (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). Activation recovery intervals (ARI) were calculated on a beat-by-beat basis by subtracting activation time (the time of minimum dV/dt during depolarization) from recovery time (the time of maximum dV/dt during repolarization) as previously described (24, 25). ARI serves as a strong surrogate of ventricular action potential duration at 90% repolarization (28).

Assessment of Myocardial and Systemic Catecholamine Levels

Myocardial interstitial catecholamine levels were assessed using fast-scanning cyclic voltammetry (FSCV), an electrochemical approach that leverages detection of oxidation and reduction of norepinephrine (NE) through a small-diameter platinum electrode under voltage clamp, as previously described (29). Briefly, perfluoroalkoxy-coated platinum wires were prepared by soldering a ∼5-mm portion of the bare wire to a gold-plated pin connector. Following completion of surgical preparation, six to eight probes were placed directly into the anterior left ventricular myocardium through 23-G needles. Ground and reference electrodes were placed into the intercostal muscle. Probes were connected to a custom amplifier (NPI Electronics, Tamm, Germany); data were acquired and analyzed for mean relative myocardial NE levels using Igor Pro 7.08 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) as previously described (29).

Blood from the coronary sinus and femoral artery were collected before nerve stimulation and at peak-nerve stimulation effect to measure plasma NE concentrations in the intact state. Blood samples were collected in EDTA collection tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ), followed by centrifugation for 15 min at 1,500 g for separation of plasma. Plasma was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to assay plasma NE levels following the manufacturer’s instructions (Rocky Mountain Diagnostics, Colorado Springs, CO).

Instrumentation and Implementation of KHFAC Block

Separate platinum bipolar electrodes were placed around the right T1-T2 paravertebral chain and right T2-T3 paravertebral chain. When this configuration was not anatomically possible (n = 6, protocol 1), one set of electrodes was placed above the right stellate ganglia (a fusion of the inferior cervical ganglia and T1) and the second at T1-T2. The proximal electrode was connected to a voltage-controlled, constant-current waveform function generator (Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, California) with a capacitor (2.2 µF) in series to prevent the application of direct current and used for KHFAC block. For protocol 1, KHFAC block was performed at varying frequency and current (15–30 kHz, 2–20 mA peak-to-peak) and for protocol 2 at fixed parameters: 15 kHz and 15 mA peak-to-peak. The distal set of electrodes was used for right sympathetic stimulation (RSS) using a Grass S88 stimulator, interfaced through a PSIU6 constant current photoelectric stimulus isolation unit (Grass Instruments, Warwick, Rhode Island). RSS was selected as it would also allow for completion of left sympathectomy for protocol 2 without disruption of electrodes. RSS was performed using 4 ms square pulse waves at 4 Hz, as these settings produce moderate increases in cardiac indices. For protocol 1, current was titrated to identify a stimulus threshold that resulted in a 20% increase in heart rate, and subsequent stimulations were performed at two times threshold for 30-s periods. For protocol 2, threshold was set at a 10% increase in heart rate, with subsequent stimulations performed at 1.5 times the threshold for 30-s periods.

Study Protocols

Protocol 1 (Fig. 1B) included assessment of scalability, plasticity, and memory. For scalability studies, KHFAC was applied at a variety of currents (2–20 mA, randomized sweep) at a fixed frequency for each animal (15–30 kHz) dependent on the electrode-nerve interface. The initial frequency tested for each animal was 30 kHz. If 30 kHz did not produce a reduction in RSS-evoked responses, 20 kHz was assessed, followed by 15 kHz. To allow for return of hemodynamic and electrophysiological parameters to baseline, there was a minimum waiting period of 5 min between assessments. For plasticity assessments, KHFAC was applied for 20 min at the previously identified optimal blocking frequency and current amplitude for each animal. RSS was performed before KHFAC and repeated at 1 min, 10 min, and 20 min after initiation of KHFAC. For memory assessments, RSS was repeated at 5, 10, and 20 min after cessation of KHFAC, or until baseline RSS-evoked response returned. For each stimulation, comparisons were made between RSS-evoked changes with application of KHFAC, relative to RSS-evoked changes in the absence of KHFAC, to calculate a percentage block in terms of cardiac indices HR, LV dP/dtmax, and ARI. Onset response duration and amplitude were simultaneously evaluated with scalability studies and similarly quantified as duration and percentage evoked change in cardiac indices.

Protocol 2 (Fig. 1C) used a fixed KHFAC frequency (15 kHz) across all animals to evaluate KHFAC in the setting of an intact cardiac neuraxis and after sympathectomy. RSS was performed in the absence of KHFAC, followed by application of KHFAC to produce a stable block, and 30 s of RSS to evaluate evoked changes in the presence of KHFAC. To confirm restoration of RSS-evoked changes, RSS was repeated after cessation of KHFAC. Assessments were spaced by a minimum of 10 min to allow cardiac indices and catecholamines to return to baseline. Following assessment of KHFAC in the intact state, the left paravertebral chain was excised (stellate to T3 ganglia) and assessment was repeated. The right paravertebral chain was subsequently excised (stellate to T3 ganglia), stimulating electrodes placed directly caudal to the excised T3 ganglia on the paravertebral chain, and assessment repeated.

Statistics

For both sets of studies, HR, LVP, LV dP/dtmax, and global ventricular ARI were assessed at baseline, during RSS in the absence of KHFAC, and during RSS with KHFAC applied. Percent block of sympathetic response was calculated by dividing the difference of RSS-evoked changes without KHFAC and RSS-evoked changes with KHFAC, by RSS-evoked changes with KHFAC, multiplied by 100. Normalization was performed due to variation in physiological parameters across animals and during the course of an experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, one-way repeated analysis of variance and Fisher’s least significant difference test were used to compare evoked changes in cardiac indices with and without KHFAC block. For non-normally distributed data, Friedman test and Dunn’s test were used. Data are presented as means ± SE. Effect size was assessed using Cohen’s d, with d > 0.8, d > 0.5, and d > 0.2 suggesting strong, moderate, and weak effect sizes, respectively (30). Pearson correlation coefficients, r, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to examine correlation between block parameters and evoked changes in cardiac indices. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

KHFAC Block Reduces Sympathetic Stimulation-Evoked Hemodynamic Changes

To characterize the effect of preemptive KHFAC block on evoked sympathetic responses, we performed RSS at baseline, and with a preemptive KHFAC block. A representative set of stimulations in the presence and absence of KHFAC is depicted in Fig. 2A. Isolated RSS resulted in an increase in HR, LV dP/dtmax, and left ventricular systolic pressure. With application of preemptive KHFAC block, RSS-evoked increases in HR, LV dP/dtmax, and left ventricular systolic pressure was mitigated, corresponding to an 89% block for HR and 75% block for LV dP/dtmax. Notably, within 5 min of cessation of block, RSS-evoked changes were restored similar to baseline. Axonal block induced by KHFAC application was evident across all animals at varying current levels (Fig. 3A). Comparison of RSS-evoked hemodynamic responses before KHFAC block and following cessation of block demonstrated no significant difference in evoked changes in heart rate or dP/dtmax in both the intact state and following left sympathectomy, indicating restored nerve conduction and lack of physiological injury (Fig. 2, B and C).

Figure 2.

Fully reversible KHFAC block reduces sympathetic stimulation-evoked hemodynamic changes. A: the first stimulation demonstrates baseline responses to RSS, with significant increases in HR, LV dP/dtmax (contractility), and LVP. The second stimulation demonstrates mitigation of these sympathetically induced responses with low-intensity preemptive KHFAC block. Note that these responses were readily reversible following cessation of KHFAC block and repeat RSS. B and C: in both the intact state and following left sympathectomy, no significant difference was observed between evoked responses before and following cessation of KHFAC, indicating restored conduction; n = 5 animals; HR and LV dP/dtmax were evaluated using one-way repeated analysis of variance and Fisher’s least significant difference test. HR, heart rate; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; L Sym., left sympathectomy; LV dP/dt, rate of change of left ventricular pressure; LV dP/dtmax, maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure; LVP, left ventricular pressure; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation.

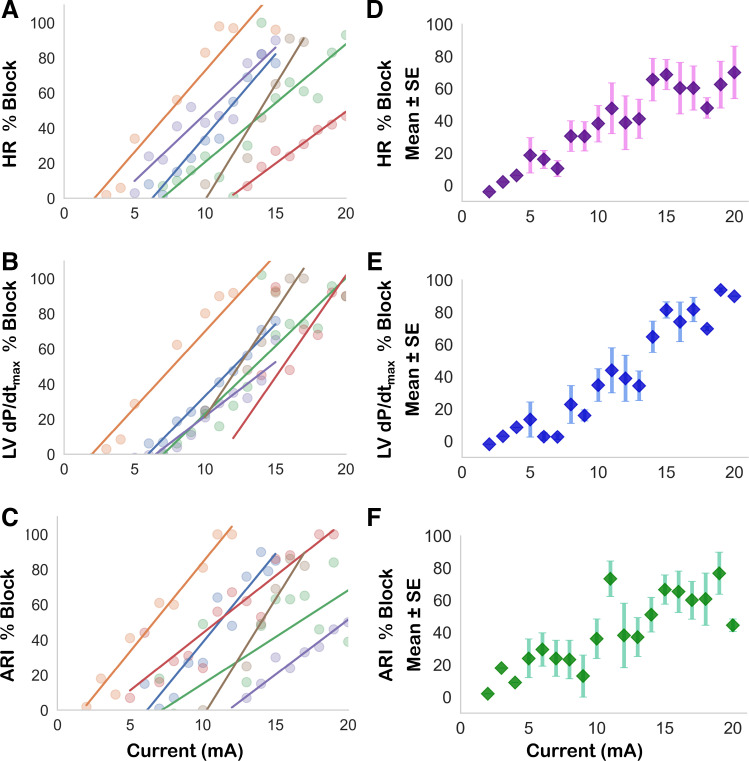

Figure 3.

Scalability and efficacy of KHFAC block. KHFAC mitigated RSS induced increases in HR, LV dP/dtmax, and shortening of ARI. A–C, on the left, demonstrate current-block relationships plotted for each animal in a separate color, and are summarized on the right (D–F) as mean and standard error of the mean of n = 6 animals. For each cardiac index, a clear, positive correlation between current amplitude and block efficacy was evident. ARI, activation recovery interval; HR, heart rate; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; LV dP/dtmax, maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure; LVP, left ventricular pressure; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation.

KHFAC Is Scalable across Cardiac Mechanical and Electrical Indices

Across a total of six animals, KHFAC current amplitude was varied from 2 mA to 20 mA at a set frequency to study the relationship between block amplitude and efficacy. For each animal studied, increasing KHFAC current resulted in a greater block of RSS-induced increases in HR (Fig. 3A) and LV dP/dtmax (Fig. 3B). Likewise, mitigation of RSS-induced shortening of ventricular activation recovery intervals (ARI, a surrogate for action potential duration) was more pronounced at greater KHFAC currents (Fig. 3C). We found strong correlation between current amplitude and mean block efficacy for HR (r = 0.94, 95% CI 0.84–0.98, P < 0.001), LV dP/dtmax (0.96, 95% CI 0.89–0.98, P < 0.001), and ventricular ARI (0.83, 95% CI 0.60–0.93, P < 0.001). When examined at the animal level, which accounts for the unique electrode-nerve interface for each subject, strong correlations between block of cardiac indices and current amplitude were also evident (Supplemental Table S1, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16826440).

With most block parameters, KHFAC resulted in a self-limited onset response for both HR and LV dP/dtmax. Onset responses were of low magnitude (28.0% for HR and 34.4% for LV dP/dtmax) and lasted for 32.0 ± 5.0 s and 71.3 ± 6.6 s for HR and LV dP/dtmax, respectively (Supplemental Table S2), although variability was observed.

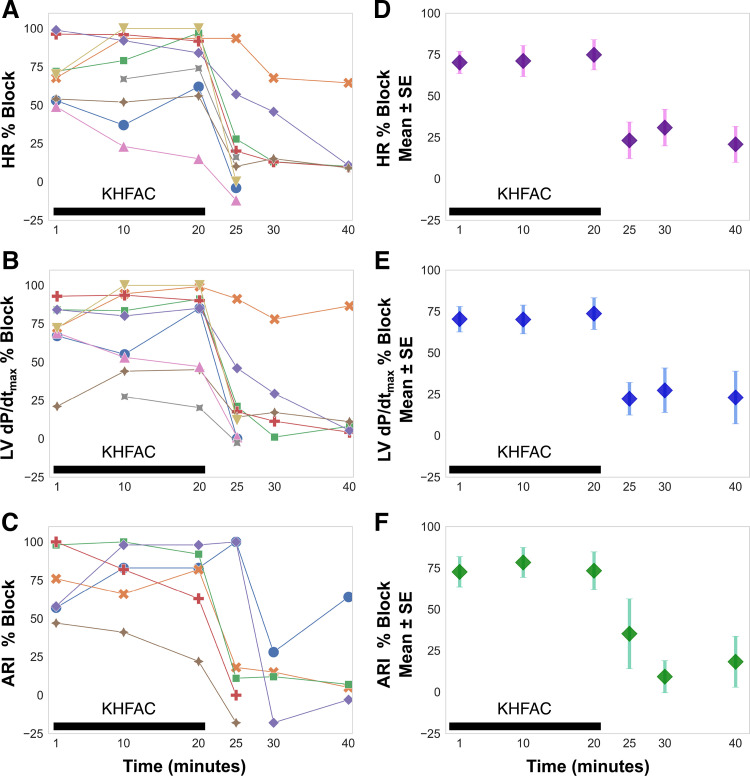

KHFAC Is Efficacious Over Time with a Short and Limited Memory Period

We examined the plasticity of KHFAC in mitigating RSS-evoked changes by applying a long-term (20 min) block and superimposing RSS stimulation at fixed periods (1, 10, and 20 min). Most animals displayed similar block efficacy at each time point studied, although the block efficacy ranged for each animal (Fig. 4). We found a similar temporal relationship for block efficacy across the three studied cardiac indices: HR, LV dP/dtmax, and ARI. We further examined whether a memory response persisted following KHFAC block by applying intermittent RSS at fixed periods after cessation of block. The majority of animals had restored evoked changes within 5 min of cessation of block, whereas a residual block was evident in a limited number (three) of animals for 20 min after block (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of plasticity and memory properties. KHFAC mitigation of changes in HR, LV dP/dtmax, and ventricular ARI were studied at six time points. A–C, on the left, report responses for each animal, which are summarized on the right (D–F) as mean and standard error of the mean. RSS was performed at 1, 10, and 20 min of KHFAC block and block efficacy for HR, LV dp/dtmax, and ARI were assessed, whereby a block efficacy of 100% indicates complete block and 0% indicates an ineffective block. Block efficacy was comparable at 1, 10, and 20 min of KHFAC block. For some animals, RSS following cessation of KHFAC produced a brief memory effect at 5, 10, and 20 min post block, whereby sympathetic stimulation-induced changes were temporarily blunted. Note that for the majority of animals, responses were restored to near baseline evoked changes within 10 min of cessation of block. n = 9 animals for HR and LV dP/dtmax, n = 6 animals for ARI. ARI, activation recovery interval; HR, heart rate; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; LV dP/dtmax, maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure; LVP, left ventricular pressure; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation.

KHFAC Block Reduces Sympathoactivation in Setting of Unilateral Sympathectomy (Stellate to T3 Ganglia)

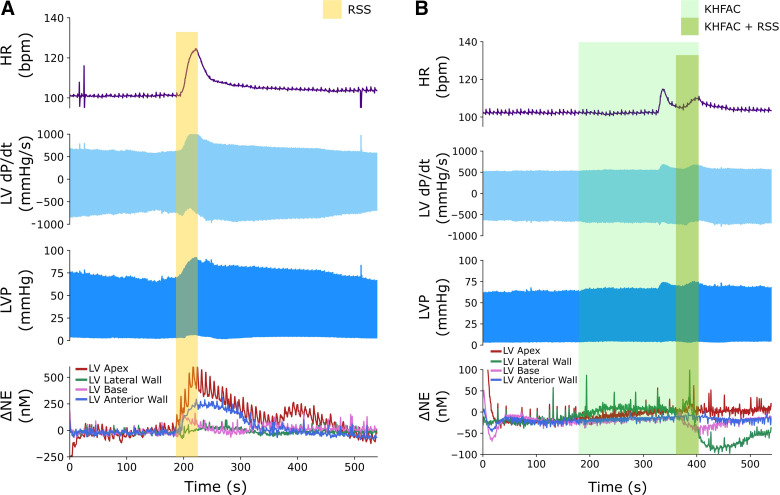

To study the utility of KHFAC in the setting of graded sympathectomy, RSS was performed with and without KHFAC block, before left sympathectomy, following left sympathectomy, and following bilateral sympathectomy. Sympathectomy was performed targeting the primary cardiac input to the heart, with excision from the stellate ganglia to the T3 ganglia, and placement of stimulating electrodes directly below the excised T3 ganglia on the right paravertebral chain (26). Given the relevance of NE as a mediator of sympathoexcitation and its role in SCD, we also measured interstitial catecholamines using FSCV and transcardiac NE release profiles using concurrent coronary sinus and systemic arterial blood sampling. Figure 5 illustrates representative changes in hemodynamics and continuous myocardial catecholamines during RSS without (Fig. 5A) and with (Fig. 5B) preemptive KHFAC block. At these parameters, a minimal onset response was evident, with subsequent reduction in evoked changes in heart rate and contractility, and with a corresponding KHFAC mitigation of NE release during RSS.

Figure 5.

KHFAC blocks catecholamine release in the myocardium. In the intact state, substantial increases in cardiovascular indices in response to 30 s of RSS were evident, with significant increases in norepinephrine levels detected by fast-scanning cyclic voltammetry (A). These responses were reduced with preemptive application of KHFAC block before RSS (B); a delayed onset response was noted with this stimulation. HR, heart rate; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; LV, left ventricle; LV dP/dt, rate of change of left ventricular pressure; LVP, left ventricular pressure; NE, norepinephrine; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation.

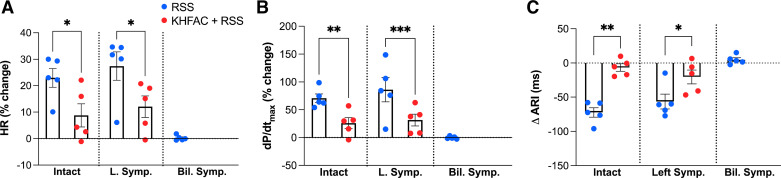

Figures 6 and 7 summarize changes in cardiac indices and corresponding NE release profiles to RSS as mitigated by preemptive KHFAC in intact versus decentralized states across five animals. In the intact state, RSS resulted in a 22.9 ± 3.6% increase in HR, which was reduced by preemptive KHFAC block (8.7 ± 4.4%, P = 0.046, d = 1.9, strong effect size, Fig. 6A). Following left sympathectomy, RSS similarly increased HR (27.4 ± 5.4%), which was mitigated by preemptive application of KHFAC block (12.0 ± 4.1%, P = 0.0455, d = 1.9, strong effect size). Similarly, KHFAC block mitigated RSS-evoked increases in dP/dtmax from 70.7 ± 7.7 to 26.0 ± 10.5% (P = 0.004, d = 2.7, strong effect size, Fig. 6B) in the intact state and following left sympathectomy (86.1 ± 21.8 vs. 26.0 ± 9.9%, P < 0.001, d = 0.5, moderate effect size). Following bilateral sympathectomy, T3 stimulation had no significant impact on dP/dtmax (−0.1 ± 1.0%). Non-normalized and absolute changes are also presented in Supplemental Table S3 with consistent findings.

Figure 6.

KHFAC mitigates sympathetic stimulation-induced changes in hemodynamic and electrophysiological parameters. RSS produced significant increases in HR (A) and LV dP/dtmax (B) with shortening of ventricular ARI (C) when applied in the intact state. These changes were significantly reduced with application of preemptive KHFAC before RSS. Similar findings were noted following left sympathectomy (middle). Notably, after bilateral sympathectomy and stimulation of distal end of T3, no significant changes in HR, LV dP/dtmax, or ARI from baseline were noted. n = 5 animals; HR was evaluated using Friedman and Dunn’s tests, and LV dP/dtmax and ARI using one-way repeated analysis of variance and Fisher’s least significant difference test. LV dP/dtmax, maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure; L Symp, left sympathectomy; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

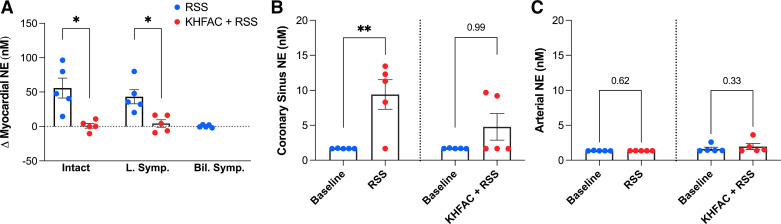

Figure 7.

KHFAC mitigates sympathetic stimulation-induced increases in myocardial NE. A: RSS produced significant increases in intramyocardial NE release in the intact state and following left sympathectomy. With application of KHFAC, RSS-evoked increases in NE were significantly reduced. Note that following bilateral sympathectomy, stimulation of the distal end of T3 produced minimal changes in NE. Coronary sinus NE content (B) increased during RSS from baseline but was unchanged with preemptive KHFAC. Note that systemic (arterial) NE levels remained unchanged during RSS (C), indicating cardiac projecting neurons as the primary source of NE. Baseline samples were at the lower limit of detection of the assay for CS and arterial plasma evaluations. n = 5 animals; arterial and CS NE were evaluated using Friedman and Dunn’s tests, and myocardial NE using one-way repeated analysis of variance and Fisher’s least significant difference test. Bil Symp, bilateral sympathectomy; KHFAC, kilohertz frequency alternating current; L Symp, left sympathectomy; NE, norepinephrine; RSS, right sympathetic chain stimulation. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Consistent with hemodynamic findings, RSS shortened ventricular ARI by 72.3 ± 7.0 ms, which was mitigated by preemptive KHFAC block (−6.6 ± 5.5 ms, P = 0.001, d = 5.7, strong effect size, Fig. 6C). Following left sympathectomy, RSS continued to shorten ventricular ARI, which was similarly mitigated by application of KHFAC (−69.1 ± 3.9 vs. −20.4 ± 10.2 ms, P = 0.039, d = 1.9, strong effect size). After bilateral sympathectomy, T3 stimulation resulted in no significant change in ventricular ARI (ΔARI 4.8 ± 2.9 ms).

Local myocardial catecholamine levels in the left ventricle, assessed using FSCV, increased by 55.8 ± 14.6 nM from baseline with RSS, which was reduced by preemptive KHFAC block (1.0 ± 3.8 nM, P = 0.030, d = 2.8, strong effect size, Fig. 7A). Similar findings were evident following left sympathectomy (43.2 ± 10.2 vs. 4.3 ± 5.4 nM, P = 0.016, d = 2.6, strong effect size), suggesting efficacy of KHFAC following left sympathectomy. After removal of bilateral sympathetic chains, T3 stimulation led to no significant change in myocardial NE compared with baseline (ΔNE = 0.3 ± 0.9 nM), consistent with hemodynamic and electrophysiological findings. Consistent with changes in hemodynamics and ARI, KHFAC induced transient, low-level release of myocardial NE in the intact state and following left sympathectomy, which was lower in magnitude compared with RSS alone (Supplemental Table S4). Coronary sinus NE content increased from baseline with RSS (d = 2.8, strong effect size), but was unchanged from baseline when preemptive KHFAC was applied (Fig. 7B), whereas systemic NE levels were unchanged (arterial NE, d = 0.2, weak effect size, Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we build upon prior proof-of-concept work and assessed several important properties of KHFAC block when applied to the paravertebral chain (24, 25). We found that KHFAC can reproducibly induce high degrees of sympathetic efferent block following a scalable dose response. Intermediate-duration KHFAC produced a short-lived memory effect, whereby conduction block persisted for a brief period following cessation of block. Importantly, KHFAC remained efficacious in the setting of unilateral sympathectomy and directly reduced myocardial catecholamine levels and their end effect on the heart.

Prior studies have examined KHFAC in the vagus nerve, peripheral nerves, and spinal cord to generate a reproducible conduction block (22, 31–33). Notably, a recent study demonstrated the feasibility of KHFAC in blocking chemoafferent-mediated signals through the carotid sinus nerve in a porcine model (34). Our prior work demonstrated proof-of-concept of KHFAC in the paravertebral chain, with reduction of sympathetic stimulation-evoked changes with KHFAC (24). In the present work, we provide data supporting the short-term scalability of KHFAC at a fixed frequency with increasing current. Although animal-to-animal variability between electrode and cardioneural interface was evident, a linear relationship between current and efficacy was present. We further found evidence of short-term memory in a subset of animals, such that reduction of efferent-evoked responses persisted beyond termination of KHFAC, consistent with studies in peripheral nerves (35). These findings suggest that a transient period of block may induce reorganization and adaptation within the nervous system, perhaps by altering neuronal recruitment within a network, leading to memory. This mirrors evidence from spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in the setting of myocardial ischemia, whereby SCS-mediated suppression of intrinsic cardiac neuronal activity lasted for a period of at least 20 min after cessation of transient SCS and coronary artery occlusion (36). Although KHFAC was effective in mitigating sympathoexcitation, transient onset responses to KHFAC were present. These may be mitigated by application of a combined direct current and KHFAC block, which has been efficacious in motor neurons (21). Importantly, as this study focused on short-term evaluation of KHFAC under anesthesia, studies examining the effects of KHFAC in healthy animals and models of chronic disease are necessary to define therapeutic potential, the presence of tolerance, and the presence of long-term memory. In a rat model of early type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic KHFAC targeted at the carotid sinus nerve improved insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance over a 9-wk period compared with sham, suggesting feasibility of chronic nerve block technology in the conscious state (37). Nonetheless, further preclinical studies of KHFAC block properties, as well as an improved understanding of the cardiac neuraxis, are necessary to augment the translation of bioelectric therapies.

Although mechanisms of KHFAC are incompletely understood, their effects have been attributed to a regional block of conduction (19, 22). Consistent with this notion, we found significant reductions in RSS-induced changes in various cardiac indices after application of KHFAC as compared with the basal state. These findings are best explained by block of efferent sympathetic fibers. As the heart has significant overlap between innervation patterns derived from the right and left paravertebral chain, evidenced through functional and histological studies (3, 38, 39), we further evaluated the efficacy of KHFAC after partial cardiac denervation. These innervation patterns are clinically relevant as left and bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation, a form of permanent neuromodulation, has been increasingly adopted for refractory VT (9). After removal of clinically relevant portions of the left paravertebral chain, we found persistent RSS-induced chronotropic and inotropic effects, which were mitigated by KHFAC, simulating a transient and reversible state of bilateral sympathectomy. Importantly, we found that these physiological changes at the end-organ level are mirrored by reductions in local catecholamine release, confirming that at least one putative mechanism of KHFAC results in blunted neurotransmitter release at the end organ.

This study has several limitations inherent to its design, as experiments were performed under general anesthesia in the absence of structural heart disease. For the first set of studies, atropine was administered to mitigate competing for autonomic input and allow for focused study of efferent activity. The second set of studies was conducted without denervation or pharmacological blockade with complementary findings, demonstrating the feasibility of KHFAC in a mixed neural population. Further study of KHFAC onset properties and approaches to mitigate onset responses will facilitate more effective nerve block and clinical translation. Moreover, due to the anesthetized preparation, studies were limited to relatively short-term assessments of KHFAC, and data regarding memory beyond 10 min were limited to less than 50% of the sample. A sham KHFAC group was not included in the present study, and it is possible that spontaneous responses to nerve stimulation decreased over time. In the absence of structural heart disease and presence of general anesthesia, our animals had low sympathetic tone and low baseline levels of catecholamines; as such, we tested sympathetic block in response to electrical stimulation of the sympathetic chain, rather than spontaneous sympathoexcitation. Further work to evaluate KHFAC, and other nerve block technologies, in response to spontaneous sympathoexcitation, is warranted. As one potential application of KHFAC is a reactionary mode in response to a perceived cardioneural stressor, future efforts will focus on a closed-loop system, whereby KHFAC is applied in response to a sensed stressor. In addition, studies in ambulatory healthy and chronic heart failure or myocardial infarction models using implantable devices will shed light on optimal parameters and long-term effects of KHFAC, particularly plasticity and memory. This study serves as a logical first step before application of KHFAC in disease models and will guide further iterative work.

Autonomic neuromodulation for cardiovascular disease is a rapidly evolving field with substantial growth in the past decade. Restoration of parasympathetic function in disease states has been emphasized through several trials evaluating cervical vagal nerve stimulation, using implantable pulse generators, for congestive heart failure, demonstrating an improvement in ventricular function, and quality of life (40–42). Excess sympathoexcitation in the setting of myocardial infarction and refractory ventricular arrythmias has been clinically treated using reversible and irreversible approaches targeting the paravertebral chain, as well as with catheter-based approaches to renal denervation (9, 10). Cardiac sympathetic denervation, a procedure that entails resection of the lower third of the stellate (cervicothoracic) ganglia through T4 of the paravertebral chain, has been increasingly used for the management of VT (10, 11). Although initial studies focused on left-sided cardiac sympathetic denervation, recent retrospective data suggest greater shock-free survival with bilateral denervation for those with refractory VT or VT storm (11, 43). An alternative, bioelectronic-based approach that may produce similar changes to sympathectomy is blockade of axonal conduction using KHFAC or alternate technologies. These approaches may function in a closed-loop system whereby a biological parameter would be detected, and therapy delivered using an implantable pulse generator, or in an open-loop system using intermittent block with duty cycles as is performed with chronic vagus nerve stimulation in humans. Such an approach may complement existing therapies, including left sympathectomy, for which proof-of-concept is demonstrated in this study. With further maturation of the field of neuromodulation, an on-demand, reactionary system that provides reversible axonal modulation may be an avenue for therapeutic development.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1–S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16826440.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U01 EB025138 (to J.L.A., K.S., and C.S.), R01 EB024860 (to N.B.), R01 HL150136 (to T.L.V.), and F32 HL160163 (to J.H.) and American Heart Association Grant 836169 (to J.H.).

DISCLOSURES

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) has patents developed by J.L.A. and K.S. relating to cardiac neural diagnostics and therapeutics. J.L.A. and K.S. are co-founders of NeuCures, Inc. Case Western Reserve University has patents developed by N.B. and T.L.V. in the field of electrical nerve block. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.H., U.B., N.B., T.L.V., C.S., K.S., and J.L.A. conceived and designed research; J.H., U.B., C.A.C., M.A.S., J.D.H., C.S., and J.L.A. performed experiments; J.H., U.B., N.Z.G., C.A.C., M.A.S., J.D.H., C.S., K.S., and J.L.A. analyzed data; J.H., U.B., N.Z.G., C.A.C., M.A.S., N.B., T.L.V., J.D.H., C.S., K.S., and J.L.A. interpreted results of experiments; J.H., U.B., N.Z.G., C.A.C., and J.L.A. prepared figures; J.H. and U.B. drafted manuscript; J.H., U.B., N.Z.G., C.A.C., M.A.S., N.B., T.L.V., J.D.H.C.S., K.S., and J.L.A. edited and revised manuscript; J.H., U.B., N.Z.G., C.A.C., M.A.S., N.B., T.L.V., J.D.H., C.S., K.S., and J.L.A. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Shyue-An Chan for assistance with implementation of FSCV and Dr. Yogi Patel for assistance with implementation of KHFAC block and initial electrode design and fabrication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics- 2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 137: e67–e492, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda K, Kanazawa H, Aizawa Y, Ardell JL, Shivkumar K. Cardiac innervation and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 116: 2005–2019, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardell JL, Andresen MC, Armour JA, Billman GE, Chen PS, Foreman RD, Herring N, O'Leary DS, Sabbah HN, Schultz HD, Sunagawa K, Zucker IH. Translational neurocardiology: preclinical models and cardioneural integrative aspects. J Physiol 594: 3877–3909, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadaya J, Ardell JL. Autonomic modulation for cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol 11: 617459, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.617459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajijola OA, Hoover DB, Simerly TM, Brown TC, Yanagawa J, Biniwale RM, Lee JM, Sadeghi A, Khanlou N, Ardell JL, Shivkumar K. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and glial cell activation characterize stellate ganglia from humans with electrical storm. JCI Insight 2: e94715, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.94715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajijola OA, Wisco JJ, Lambert HW, Mahajan A, Stark E, Fishbein MC, Shivkumar K. Extracardiac neural remodeling in humans with cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 5: 1010–1116, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.972836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Terentyeva R, Ho HT, Gyorke I, Bonilla IM, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Györke S. Shortened Ca2+ signaling refractoriness underlies cellular arrhythmogenesis in a postinfarction model of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 110: 569–577, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billman GE. Cardiac autonomic neural remodeling and susceptibility to sudden cardiac death: effect of endurance exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1171–H1193, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00534.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shivkumar K, Ajijola OA, Anand I, Armour JA, Chen PS, Esler M, De Ferrari GM, Fishbein MC, Goldberger JJ, Harper RM, Joyner MJ, Khalsa SS, Kumar R, Lane R, Mahajan A, Po S, Schwartz PJ, Somers VK, Valderrabano M, Vaseghi M, Zipes DP. Clinical neurocardiology defining the value of neuroscience-based cardiovascular therapeutics. J Physiol 594: 3911–3954, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, Sankhla V, Shah M, Swapna N, Boyle NG, Mahajan A, Narasimhan C, Lokhandwala Y, Shivkumar K. Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation 121: 2255–2262, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.929703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaseghi M, Barwad P, Malavassi Corrales FJ, Tandri H, Mathuria N, Shah R, Sorg JM, Gima J, Mandal K, Sàenz Morales LC, Lokhandwala Y, Shivkumar K. Cardiac sympathetic denervation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 3070–3080, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossot D, Kabiri H, Caliandro R, Debrosse D, Girard P, Grunenwald D. Early complications of thoracic endoscopic sympathectomy: a prospective study of 940 procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 71: 1116–1119, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahajan A, Moore J, Cesario DA, Shivkumar K. Use of thoracic epidural anesthesia for management of electrical storm: a case report. Heart Rhythm 2: 1359–1362, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do DH, Bradfield J, Ajijola OA, Vaseghi M, Le J, Rahman S, Mahajan A, Nogami A, Boyle NG, Shivkumar K. Thoracic epidural anesthesia can be effective for the short-term management of ventricular tachycardia storm. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e007080, 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goroszeniuk T, Pang D. Peripheral neuromodulation: a review. Curr Pain Headache Rep 18: 412, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuellar JM, Alataris K, Walker A, Yeomans DC, Antognini JF. Effect of high-frequency alternating current on spinal afferent nociceptive transmission. Neuromodulation 16: 318–327, 2013. doi: 10.1111/ner.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilgore KL, Bhadra N. Reversible nerve conduction block using kilohertz frequency alternating current. Neuromodulation 17: 242–254, 2014. doi: 10.1111/ner.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vrabec T, Bhadra N, Acker G, Bhadra N, Kilgore K. Continuous direct current nerve block using multi contact high capacitance electrodes. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 25: 517–529, 2016. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2016.2589541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waataja JJ, Tweden KS, Honda CN. Effects of high-frequency alternating current on axonal conduction through the vagus nerve. J Neural Eng 8: 056013, 2011. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/5/056013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackermann DM Jr, Bhadra N, Foldes EL, Kilgore KL. Conduction block of whole nerve without onset firing using combined high frequency and direct current. Med Biol Eng Comput 49: 241–251, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0679-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franke M, Vrabec T, Wainright J, Bhadra N, Bhadra N, Kilgore K. Combined KHFAC + DC nerve block without onset or reduced nerve conductivity after block. J Neural Eng 11: 056012, 2014. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/11/5/056012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhadra N, Kilgore KL. Direct current electrical conduction block of peripheral nerve. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 12: 313–324, 2004. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2004.834205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhadra N, Kilgore KL. Chapter 10 - Fundamentals of kilohertz frequency alternating current nerve conduction block of the peripheral nervous system. In: Neuromodulation (2nd ed.), edited by Krames ES, Peckham PH, Rezai AR.. London: Academic Press, 2018, p. 111–120. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-805353-9.00010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckley U, Chui RW, Rajendran PS, Vrabec T, Shivkumar K, Ardell JL. Bioelectronic neuromodulation of the paravertebral cardiac efferent sympathetic outflow and its effect on ventricular electrical indices. Heart Rhythm 14: 1063–1070, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chui RW, Buckley U, Rajendran PS, Vrabec T, Shivkumar K, Ardell JL. Bioelectronic block of paravertebral sympathetic nerves mitigates post-myocardial infarction ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 14: 1665–1672, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buckley U, Yamakawa K, Takamiya T, Andrew Armour J, Shivkumar K, Ardell JL. Targeted stellate decentralization: implications for sympathetic control of ventricular electrophysiology. Heart Rhythm 13: 282–288, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris JE, Foreman RD, Wurster RK. Responses of the canine heart to stimulation of the first five ventral thoracic roots. Am J Physiol 227: 9–12, 1974. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millar CK, Kralios FA, Lux RL. Correlation between refractory periods and activation-recovery intervals from electrograms: effects of rate and adrenergic interventions. Circulation 72: 1372–1379, 1985. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.6.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan SA, Vaseghi M, Kluge N, Shivkumar K, Ardell JL, Smith C. Fast in vivo detection of myocardial norepinephrine levels in the beating porcine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318: H1091–H1099, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00574.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox RR, Tian TS. Measuring effect size: a robust heteroscedastic approach for two or more groups. J Appl Stat 38: 1359–1368, 2011. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2010.498507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel YA, Saxena T, Bellamkonda RV, Butera RJ. Kilohertz frequency nerve block enhances anti-inflammatory effects of vagus nerve stimulation. Sci Rep 7: 39810, 2017. [Erratum in Sci Rep 7: 46848, 2017]. doi: 10.1038/srep39810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shechter R, Yang F, Xu Q, Cheong YK, He SQ, Sdrulla A, Carteret AF, Wacnik PW, Dong X, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Guan Y. Conventional and kilohertz-frequency spinal cord stimulation produces intensity- and frequency-dependent inhibition of mechanical hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology 119: 422–432, 2013. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829bd9e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanner JA. Reversible blocking of nerve conduction by alternating-current excitation. Nature 195: 712–713, 1962. doi: 10.1038/195712b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fjordbakk CT, Miranda JA, Sokal D, Donegà M, Viscasillas J, Stathopoulou TR, Chew DJ, Perkins JD. Feasibility of kilohertz frequency alternating current neuromodulation of carotid sinus nerve activity in the pig. Sci Rep 9: 18136, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53566-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhadra N, Foldes E, Vrabec T, Kilgore K, Bhadra N. Temporary persistence of conduction block after prolonged kilohertz frequency alternating current on rat sciatic nerve. J Neural Eng 15: 016012, 2018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aa89a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armour JA, Linderoth B, Arora RC, DeJongste MJ, Ardell JL, Kingma JG Jr, Hill M, Foreman RD. Long-term modulation of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system by spinal cord neurons in normal and ischaemic hearts. Auton Neurosci 95: 71–79, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacramento JF, Chew DJ, Melo BF, Donegà M, Dopson W, Guarino MP, Robinson A, Prieto-Lloret J, Patel S, Holinski BJ, Ramnarain N, Pikov V, Famm K, Conde SV. Bioelectronic modulation of carotid sinus nerve activity in the rat: a potential therapeutic approach for type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 61: 700–710, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4533-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaseghi M, Zhou W, Shi J, Ajijola OA, Hadaya J, Shivkumar K, Mahajan A. Sympathetic innervation of the anterior left ventricular wall by the right and left stellate ganglia. Heart Rhythm 9: 1303–1309, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanowitz F, Preston JB, Abildskov JA. Functional distribution of right and left stellate innervation to the ventricles. Production of neurogenic electrocardiographic changes by unilateral alteration of sympathetic tone. Circ Res 18: 416–428, 1966. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anand IS, Konstam MA, Klein HU, Mann DL, Ardell JL, Gregory DD, Massaro JM, Libbus I, DiCarlo LA, Udelson JJE, Butler J, Parker JD, Teerlink JR. Comparison of symptomatic and functional responses to vagus nerve stimulation in ANTHEM-HF. INOVATE-HF, and NECTAR-HF. ESC Heart Fail 7: 75–83, 2020. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz PJ, De Ferrari GM, Sanzo A, Landolina M, Rordorf R, Raineri C, Campana C, Revera M, Ajmone-Marsan N, Tavazzi L, Odero A. Long term vagal stimulation in patients with advanced heart failure: first experience in man. Eur J Heart Fail 10: 884–891, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma K, Premchand RK, Mittal S, Monteiro R, Libbus I, DiCarlo LA, Ardell Jl, Amurthur B, KenKnight BH, Anand IS. Long-term follow-up of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection receiving autonomic regulation therapy in the ANTHEM-HF pilot study. Int J Cardiol 323: 175–178, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Assis FR, Sharma A, Shah R, Akhtar T, Adari S, Calkins H, Ha JS, Mandal K, Tandri H. Long-term outcomes of bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation for refractory ventricular tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 7: 463–470, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables S1–S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16826440.