Abstract

Background:

Limited prior research has examined the rates or predictors of re-perpetration of child maltreatment. Yet, perpetrators may have multiple victims, and perpetrators, rather than their victims, are often the primary focus of child welfare services.

Objective:

We examine rates of child maltreatment re-perpetration of repeat and new victims, and test perpetrator demographics and maltreatment index incident case characteristics as predictors of re-perpetration.

Participants and Setting:

We use a sample of 285,245 first-time perpetrators of a substantiated maltreatment incident in 2010 from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System.

Methods:

We use linear probability models with full information maximum likelihood to test new victim and same victim perpetration by the end of FY 2018.

Results:

Fifteen percent of perpetrators re-maltreated one or more of their original victims (“same victim re-perpetration”); 12% maltreated a new victim. Overall, re-perpetration was more common among younger, female, and White perpetrators. Perpetrators who were the biological or adoptive parent of their initial victim(s) had higher rates of same victim re-perpetration; new victim re-perpetration was more common among perpetrators who initially victimized an adoptive or stepchild. Same victim re-perpetration was less common among perpetrators of physical abuse than other types of maltreatment, and new victim re-perpetration was more common among perpetrators of sexual abuse and neglect than physical abuse.

Conclusions:

Child welfare agencies should track re-perpetration in addition to revictimization as part of agency evaluations and risk assessments.

Keywords: child maltreatment, perpetrators, re-perpetration, revictimization

An estimated 28-37 percent of U.S. children are investigated (Kim et al., 2017; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2021), and 12 percent are substantiated (Wildeman et al., 2014), as victims of child maltreatment by Child Protective Services (CPS) prior to age 18. Child maltreatment involves abuse (sexual abuse and infliction of physical or psychological injury), or neglect, wherein a caretaker does not meet a child’s physical, emotional, or supervision needs. Abuse and neglect, both substantiated and suspected, are associated with numerous deleterious outcomes for children over time (Currie & Tekin, 2012; Drake & Jonson-Reid, 2000; Font & Berger, 2015; Romano et al., 2015; Zielinski, 2009), especially when maltreatment is repeated or prolonged (Solomon & Åsberg, 2012). Although a substantial body of literature has investigated the characteristics of individuals who perpetrate child maltreatment or has investigated risk factors for children experiencing re-victimization, few studies examine predictors of re-perpetrating maltreatment. Although re-victimization is tracked because CPS interventions are focused on child safety, it is typically the perpetrators who receive the majority of services (Berger & Font, 2015). Thus, re-perpetration is a key metric for understanding CPS efficacy. Using data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), the present study (1) estimates rates of re-perpetration by end of fiscal year 2018 for a cohort of perpetrators with a first-time substantiated offense in 2010, differentiating between re-perpetration against new victims and a new incident involving the original (same) victim; and (2) examines how perpetrator demographics and index incident characteristics are associated with re-perpetration. Index incident refers to the first substantiated case of maltreatment during the calendar year 2010.

In this paper, we define the index incident and re-perpetration based on substantiated reports of maltreatment.1 This means that we are not addressing instances of maltreatment that are either unreported or unsubstantiated. Crucially, CPS substantiation is a highly imperfect proxy for measuring child maltreatment. About 20 percent of CPS investigations are substantiated (with many states substantiating fewer than 10 percent) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020); and substantiation is a poor indicator of future risk of maltreatment (Kohl et al., 2009) or child outcomes (Font et al., 2020; Hussey et al., 2005). Rather than serving as an objective measure of maltreatment occurrence, substantiation patterns vary across caseworkers, agencies, and states and may be subject to implicit or conscious biases. Substantiated re-perpetration thus captures both the maltreatment behavior and the labeling of that behavior by CPS. Notwithstanding those limitations, official rates of re-perpetration are important because substantiated cases are those for which the governmental agency acknowledges a responsibility to mitigate risk of harm. Further, differentiating between re-perpetration with a new victim versus a same victim speaks to perpetrators’ continued access to children and effectiveness of the initial CPS response.

Child Maltreatment Recurrence

Estimates of maltreatment recurrence in CPS focus largely on re-victimization (e.g., Connell et al., 2007; Hindley, 2006; Kahn & Schwalbe, 2010; Kim & Drake, 2019), as preventing recurrent harm to victims is a primary metric of CPS effectiveness (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018a). Approximately 28 percent of children found to be victims will have a second substantiated case of maltreatment by age 12 (Kim & Drake, 2019). To our knowledge, available estimates do not consider whether children were re-victimized by the same or different perpetrators.

Studies of re-victimization generally show that factors associated with initial maltreatment onset also predict recurrence, including family structure, poverty, and parental mental health and substance abuse (White et al., 2015). Further, children are more likely to be re-victimized when the initial maltreatment involved multiple victims or forms of maltreatment (White et al., 2015). There is also some evidence that patterns of maltreatment re-victimization differ by perpetrator race and sex. Research using NCANDS data found that sexual abuse re-victimization was less common among Hispanic than non-Hispanic children (Palusci & Ilardi, 2020; Sinanan, 2011). However, findings on recurrence rates for Black and other minority perpetrators are inconsistent (Bae et al., 2009; White et al., 2015). Additionally, using state administrative data, Jonson-Reid et al. (2003) found that male perpetrators were more likely to commit sexual abuse multiple times, whereas female perpetrators were more likely to re-perpetrate neglect.

Further, maltreatment recurrence appears to be more common when perpetrators are parents (Drake et al., 2003) and sexual abuse recurrence is higher when perpetrators are in any caregiver role (Sinanan, 2011). This may reflect that, due to social and legal emphasis on family preservation, parents are more likely than others to continue post-maltreatment access to their original victim. However, some studies indicate that recurrence of serious maltreatment is more common when children are in homes without either biological parent (Miyamoto et al., 2017) and that male child molesters are most likely to re-perpetrate against acquaintances, followed by step-children and then biological children (Greenberg et al., 2000).

In contrast, there has been comparatively little attention to re-perpetration specifically, and much of the previous literature used small convenience samples of abusive parents (Bader et al., 2010; Ferleger et al., 1988) or non-U.S. samples (Greenberg et al., 2000). These findings may not translate to a broad U.S. context due to variation in CPS policy and practice. We build specifically on research conducted by Jonson-Reid et al. (2010), which used data from a Midwestern state to identify factors associated with maltreatment of both a repeat and new victim. They found that re-perpetration was less common when perpetrators received services (e.g. cash assistance), but more common when female perpetrators received mental health or substance abuse treatment. They also found that nearly half of perpetrators who were re-reported had allegedly maltreated a new victim. We examine both same victim and new victim re-perpetration using a large, national sample of substantiated perpetrators.

Contextualizing Re-Perpetration

Previous research indicates that women are overrepresented in child maltreatment cases, particularly neglect (Damashek et al., 2013; DiLauro, 2004; Dufour et al., 2008; Pittman & Buckley, 2006; Schnitzer & Ewigman, 2005; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020a), despite lower rates of crime and violence overall (Morgan & Truman, 2019). Higher rates of re-perpetration among women, and particularly mothers, likely reflect greater caregiving responsibilities, as women are far more likely than men to be the sole or primary caregiver of a child (Yavorsky et al., 2015). In addition, cultural expectations that place higher parenting expectations on women (Moon & Hoffman, 2008) may also result in a higher probability of substantiation for maltreatment –all else equal –among mothers. At the same time, father-perpetrated neglect (with or without a co-perpetrator) may be more likely to result in criminal charges than mother-perpetrated neglect (Kobulsky & Wildfeuer, 2019) and male convictions for child maltreatment are more likely to result in incarceration (Hanrath & Font, 2020; Kobulsky et al., 2021). Consequently, male perpetrators may be more likely to be separated from their victims (due to incarceration, custody order, or other means), thus resulting in a lower likelihood of re-perpetration, especially of same victims. This sex difference in re-perpetration may also be more pronounced for parents than for perpetrators in other roles.

Black children tend to have lower rates of maltreatment recurrence compared to White children (Kim & Drake, 2019) and some evidence suggests that they are more likely to be removed from the home following substantiated abuse (Knott & Donovan, 2010). It is possible that changes in access to the child caused by removal from the home may result in lower rates of re-perpetration with the same victim. Moreover, research on the criminal justice system suggests – net of differences in criminal activity – differential treatment within the system that favors Whites (Kutateladze et al., 2014). Although the evidence of such biases in the CPS system is far more equivocal (Drake et al., 2009, 2011; Kobulsky et al., 2021; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2013) and little of this research has focused on perpetrators, racial stereotypes that associate non-White groups with criminality or dangerousness (Dixon & Maddox, 2005) may result in disparate rates of substantiation. In addition, if maltreatment by non-White perpetrators is disproportionately likely to result in separation from the victim (through incarceration of the perpetrator, removal of the child, or other means), non-White perpetrators may re-perpetrate at lower rates. Indeed, studies have found that both court-appointed attorneys (Harris & Hackett, 2008) and judges (O’Donnell et al., 2005) view and treat Black men more negatively than White men in CPS cases.

The intersection of race and sex may also be important, as it has been reported that men, in general, are viewed more harshly in CPS cases than women (O’Donnell et al., 2005), such that Black men may be perceived as posing a greater threat of harm relative to both White men and women and Black women. In sum, if the threshold for substantiation (and criminal justice or CPS intervention) is higher for White perpetrators than others, then the initial pool of White perpetrators should be higher risk (have perpetrated more serious harm) than perpetrators of other races, and their harms would be less likely to be addressed through intensive interventions (e.g., child removal or criminal charges against the perpetrator). If so, Whites may have higher rates of re-perpetration – reflecting continued access to their initial victim as well as potentially greater access to other children. Alternatively, higher thresholds for substantiation may result in (artificially) lower rates of re-perpetration for Whites because their initial or subsequent perpetration was not accurately identified (i.e., was unsubstantiated).

Current Study

There are important gaps in our knowledge of maltreatment re-perpetration. Only a few studies of maltreatment recurrence have focused specifically on perpetrator characteristics (Bader et al., 2010; Jonson-Reid et al., 2003, 2010; Way et al., 2001) and studies that include perpetrator characteristics tend to focus exclusively on perpetrators who are parents or caregivers and who are at risk of repeat maltreatment of the same child or children. Additionally, much of the existing work draws from older data or small, geographically limited samples. Focusing on offenders who had their first substantiated maltreatment offense in 2010, the objectives of the current study are to: (1) assess rates and predictors of two forms of child maltreatment re-perpetration (new victim and same victim) over a 10-year period, and (2) test whether predictors of re-perpetration differ by perpetrator sex. We use a large, recent sample of perpetrators from across the United States.

Data and Methods

We use the most recent 10 years of data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018b), federal fiscal years 2009-2018. The NCANDS Child File compiles data on investigated reports of child maltreatment to CPS agencies in each state. NCANDS data represent a census of children and perpetrators reported for maltreatment in the relevant time period, but characteristics are not reported for individuals who were alleged but not confirmed as perpetrators.

Sample

Our sample comprises all identified perpetrators with a first substantiated case of maltreatment during the calendar year 2010 (index incident). We exclude all cases from states that did not consistently track child IDs over time (such that we could not distinguish same victims from new victims; Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Puerto Rico) and five states with unreliable data2 (Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Oregon, and Washington). Within the remaining 37 states and the District of Columbia, we exclude perpetrators with suspiciously high incident or victim counts (more than 10; n=49 perpetrators, < 0.02% of perpetrator IDs). Our final sample includes 285,245 perpetrators.

Measures

Dependent variables.

We created two measures of maltreatment re-perpetration3. Same victim re-perpetration is an indicator of whether a perpetrator had a new substantiated incident of child maltreatment following the 2010 index incident with a child who was a victim in that index incident (1=yes, 0=no). New victim re-perpetration is an indicator of whether a perpetrator maltreated a new child following the 2010 index incident (1=yes, 0=no). Both are binary variables comparing the identified group to all other perpetrators with a first-time substantiated case in 2010. The measures are not mutually exclusive (a perpetrator may have both forms of re-perpetration).

Independent Variables.

Our primary predictors are characteristics of the perpetrator and index incident. Perpetrator characteristics included sex (1=male, 0=female), race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other race or multiple races), and 2010 age in years (range 18-704). Index incident characteristics included co-perpetration (1=>1 perpetrator; 0 otherwise), the number of victims (range 1-10), the age of the youngest victim at the time of the maltreatment report (range 0-18), and type of maltreatment committed (physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, other abuse5, and multiple types of abuse). Perpetrator relationship to index incident victims has seven categories: biological parent, adoptive parent or legal guardian, step-parent or parent’s unmarried partner, foster parent, other relative, other non-relative, and multiple relationships. Lastly, we include state fixed effects to account for stable differences between states in both population characteristics and CPS practice.

Analytic Plan

We first test a linear probability model using all independent variables as predictors of same victim re-perpetration and new victim re-perpetration. We then repeat this main model including four interactions: perpetrator sex and race, perpetrator sex and co-perpetration, perpetrator sex and relationship to victim(s), and perpetrator sex and maltreatment type. Finally, in order to rule out altered patterns of re-perpetration due to children turning eighteen and leaving the pool of potential victims during the study period, we test a supplementary model predicting same victim re-perpetration among perpetrators with at least one child under the age of eight at the index incident.

Due to the large sample, we identify statistical significance at the .01 level rather than the traditional .05 level. Linear probability coefficients are interpreted as percentage point changes in the probability of the outcome – a measure of absolute difference, rather than relative difference. Thus, we also describe our results with relative risk ratios to provide a sense of degree of difference across levels/categories of the independent variables.

We use full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data. Missingness is generally low, with less than two percent missing for all variables except perpetrator relationship to victim (8.1 percent missing). To improve our modeling of missing values, we include auxiliary variables measuring average victim age, an indicator of whether the perpetrator is a parent to the victim or victims, victim sex, and victim race in all models.

Results

Sample Description

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for first-time perpetrators who did not re-perpetrate, perpetrators with a same victim, and perpetrators with a new victim. We calculate that 42,618 out of 285,245 perpetrators re-perpetrated against one or more previous victims, for a re-perpetration rate of 15 percent; 34,011 perpetrators maltreated a new victim, for a re-perpetration rate of 12 percent.6

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Outcome

| No Re-Perpetration | Same Victim | New Victim | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | 227,900 | 42,618 | 34,011 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Mean/Prop | SD | Mean/Prop | SD | Mean/Prop | SD | |

| Perpetrator Characteristics | ||||||

| Male | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.47 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.20 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | |||

| Other or multiple races | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.09 | |||

| Age | 33.46 | 11.05 | 30.51 | 9.17 | 28.30 | 8.38 |

| Index Incident Characteristics | ||||||

| Any co-perpetrator | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Number of victims | 1.56 | 0.96 | 1.80 | 1.12 | 1.54 | 0.96 |

| Age of youngest victim | 6.18 | 5.45 | 3.97 | 4.39 | 3.74 | 4.62 |

| Relationship to victim | ||||||

| Biological parent | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.83 | |||

| Adoptive parent or legal guardian | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Step-parent or parent’s partner | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |||

| Foster parent | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Relative | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |||

| Other | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||

| Multiple relationships | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||

| Maltreatment type | ||||||

| Physical abuse | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| Sexual abuse | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |||

| Neglect | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.61 | |||

| Other maltreatment | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |||

| Multiple types of maltreatment | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.29 | |||

Prop: Proportion

SD: Standard Deviation

Both forms of re-perpetration were more common among females and non-Hispanic Whites than males or other racial groups. Those with no re-perpetration were the oldest at their index perpetration (M = 33.5, versus M = 30.5 for same victim perpetration and M = 28.3 for new victim perpetration). Re-perpetration of a same victim was more common among perpetrators with a co-perpetrator in the index incident and among perpetrators with more victims in the index incident. On average, repeat perpetrators had younger victims, were more likely to be biological parents, less likely to be step-parents or others, more likely to commit neglect, and less likely to have committed physical abuse than single incident perpetrators.

Regression Results

Main Models.

Models predicting same victim and new victim re-perpetration are shown in Table 2. Male perpetrators had a 5.3 percentage point (PP) lower probability – equating to a 30% lower relative risk— of same victim re-perpetration and 4.9 PP lower probability (33% lower relative risk) of new victim re-perpetration compared to female perpetrators. Compared to non-Hispanic White perpetrators, the probability of same victim re-perpetration was 3PP lower for Black and Hispanic perpetrators (relative difference of 18%), whereas differences in new victim re-perpetration were small in magnitude (and statistically non-significant for Black perpetrators). In contrast, perpetrators of other or multiple races had 6.6 PP lower probability of same victim re-perpetration (38% lower relative risk) and 4 PP lower probability of new victim re-perpetration (31% lower relative risk risk) than non-Hispanic White perpetrators. An additional year of perpetrator age at the index incident predicted 0.1 PP lower probability of same victim re-perpetration (1% lower relative risk), and 0.3 PP lower probability of new victim re-perpetration (2% lower relative risk).

Table 2.

Main Models

| Same Victim | New Victim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b(SE) | RRR | b(SE) | RRR | |

| Perpetrator Characteristics | ||||

| Male | −0.053 (0.001)*** | 0.7 | −0.049 (0.001)*** | 0.67 |

|

Race/ethnicity (reference=Non-Hispanic White) |

||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.031 (0.002)*** | 0.82 | −0.002 (0.002) | 0.99 |

| Hispanic | −0.031 (0.002)*** | 0.82 | −0.005 (0.002)*** | 0.96 |

| Other or multiple races | −0.066 (0.002)*** | 0.62 | −0.040 (0.002)*** | 0.69 |

| Age | −0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.99 | −0.003 (0.000)*** | 0.98 |

| Index incident characteristics | ||||

| Any co-perpetrator | −0.000 (0.001) | 1 | −0.004 (0.001)** | 0.97 |

| Number of victims | 0.022 (0.001)*** | 1.16 | −0.014 (0.001)*** | 0.89 |

| Age of youngest victim | −0.006 (0.000)*** | 0.97 | −0.005 (0.000)*** | 0.96 |

|

Relationship to victim (reference=biological parent) |

||||

| Adoptive parent or legal guardian | −0.013 (0.007) | 0.93 | 0.019 (0.006)** | 1.15 |

| Step-parent or parent’s partner | −0.034 (0.003)*** | 0.8 | 0.009 (0.002)*** | 1.07 |

| Foster parent | −0.119 (0.010)*** | 0.29 | −0.023 (0.009)** | 0.81 |

| Relative | −0.078 (0.003)*** | 0.53 | −0.027 (0.002)*** | 0.78 |

| Other | −0.071 (0.003)*** | 0.58 | −0.016 (0.003)*** | 0.87 |

| Multiple relationships | −0.021 (0.004)*** | 0.87 | −0.004 (0.003) | 0.97 |

|

Maltreatment type (reference=physical abuse) |

||||

| Sexual abuse | 0.029 (0.005)*** | 1.22 | 0.024 (0.004)*** | 1.22 |

| Neglect | 0.026 (0.004)*** | 1.2 | 0.014 (0.004)*** | 1.13 |

| Other maltreatment | 0.028 (0.005)*** | 1.22 | 0.008 (0.005) | 1.07 |

| Multiple types of maltreatment | 0.018 (0.004)*** | 1.14 | 0.014 (0.004)*** | 1.12 |

| Constant | 0.226 (0.005)*** | 0.292 (0.005)*** | ||

Notes: N=285,245. Linear probability coefficients. Standard errors (SE) in parentheses;

p<0.01

p<0.001;

RRR = Relative Risk Ratio

State fixed effects included (not shown)

Co-perpetration in the index incident was not associated with same victim re-perpetration but was associated with 0.4 PP lower probability (3% lower relative risk) of new victim re-perpetration. Each additional victim involved in the index incident was associated with 2.2 PP higher probability of same victim re-perpetration (16% higher relative risk), but 1.4 PP lower probability of new victim re-perpetration (11% lower relative risk). An additional year of age for the youngest victim in the index incident was associated with approximately 0.6 PP lower probability of same victim re-perpetration (3% lower relative risk) and 0.5 PP lower probability of new victim re-perpetration (4% lower relative risk).

Overall, biological parents, who comprise the vast majority of first-time perpetrators, were also the majority of re-perpetrators. However, perpetrators who were the adoptive or legal guardian of their victim in the index incident were equally likely to re-perpetrate against their original victim and had a 1.9 PP higher probability of new victim re-perpetration (15% higher relative risk). Similarly, those who were the victim’s parent’s partner or the victim’s stepparent in the index incident had lower probability of same victim re-perpetration (20% lower relative risk), but higher probability of new victim re-perpetration (7% higher relative risk). Those who were the foster parent, relative, other, or had multiple roles with their victim in the index incident had significantly lower probabilities of same victim re-perpetration and those who were foster parents, relatives, or other individuals had significantly lower probabilities of new victim re-perpetration. However, whereas differences in same victim re-perpetration were quite large, differences in rates of new victim re-perpetration were relatively small in magnitude. Again, because perpetrators with these latter relationship roles comprise a small proportion of the total sample, they have little influence on overall rates of re-perpetration.

Compared to perpetrators with an index substantiation for physical abuse, perpetrators of all other maltreatment types had higher rates of same victim re-perpetration, with sexual abuse, neglect, and other maltreatment each associated with a 2.6PP – 2.9PP increase in probability, equating to a 20-22% increased relative risk. Index perpetration of multiple forms of maltreatment was associated with a 1.8PP higher probability of same victim re-perpetration (13% higher relative risk). For new victim re-perpetration, sexual abuse was associated with a 2.4PP higher probability (21% higher relative risk), whereas neglect and multiple forms of maltreatment were associated with 1 1.4 PP higher probabilities (12% higher relative risk).

Interaction Models.

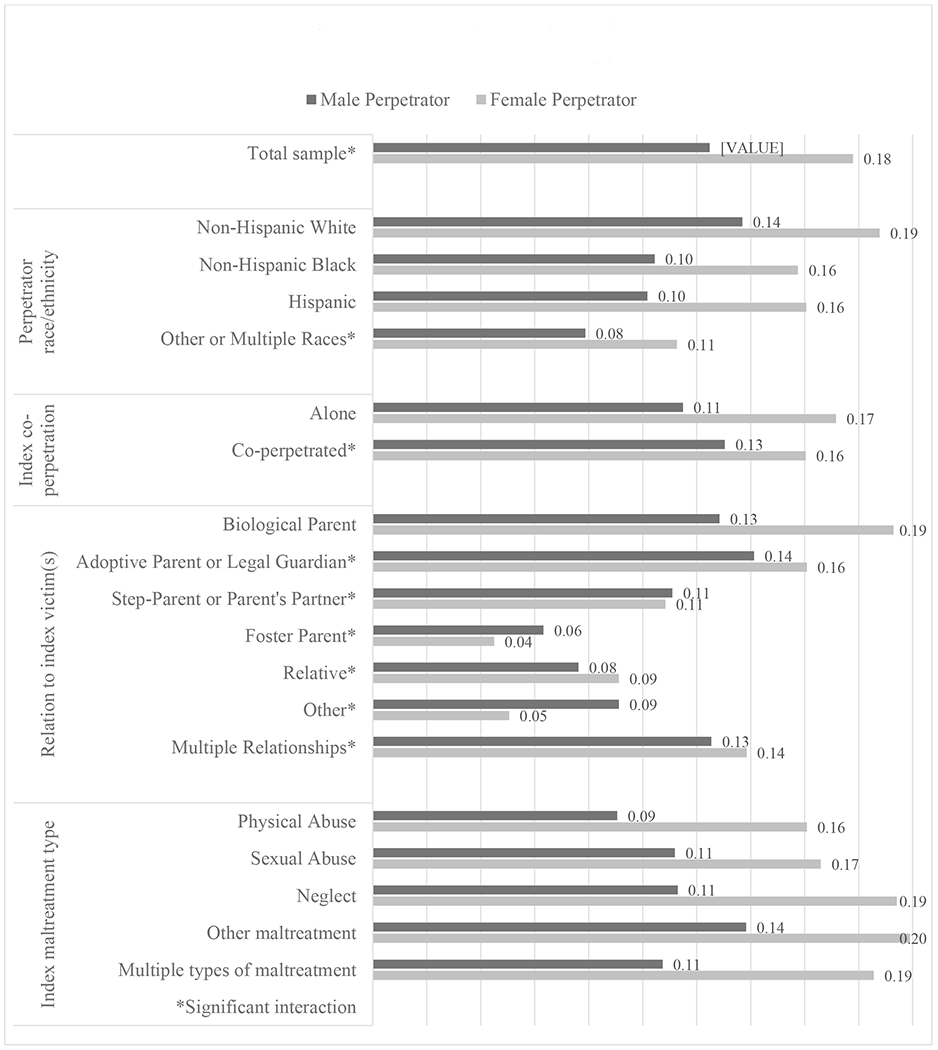

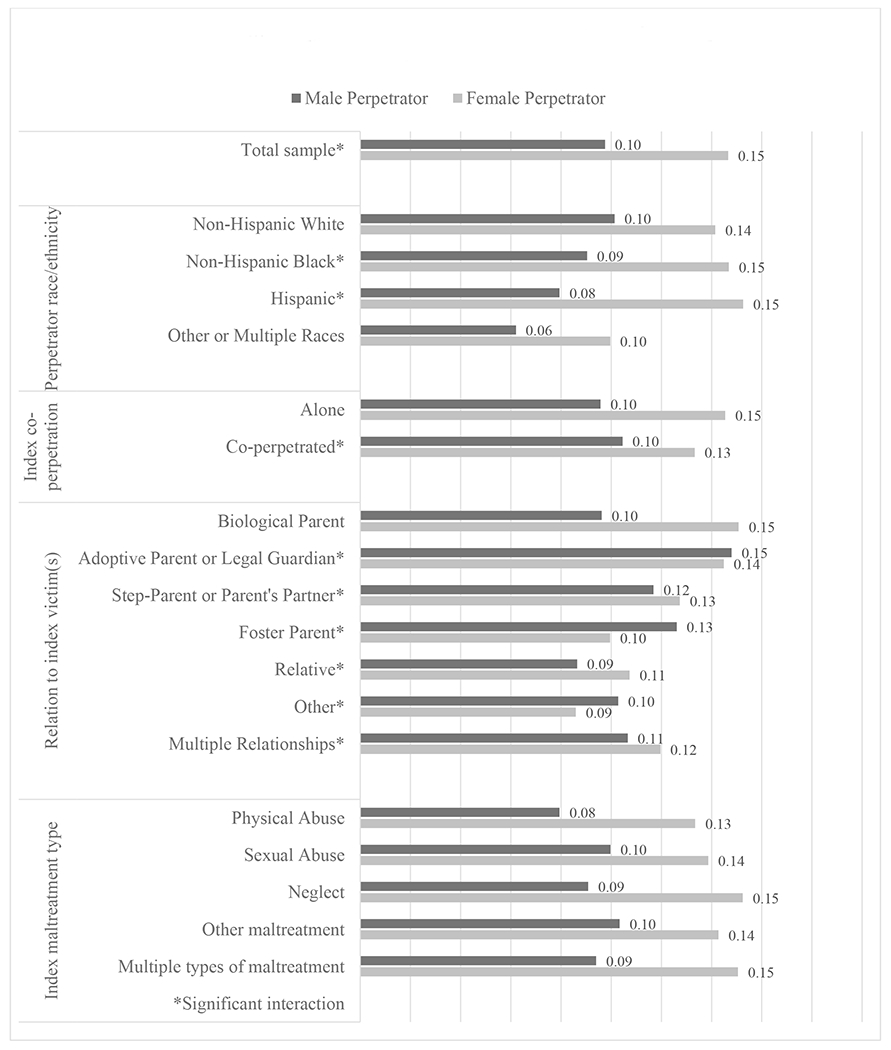

In the interaction models, displayed in Table 3, we examine how perpetrator race, co-perpetration, index perpetrator role, and maltreatment type vary by perpetrator sex for same victim re-perpetration and new victim re-perpetration. These models seek to assess whether sex differences in re-perpetration are explained by race, co-perpetration, and index maltreatment patterns, or whether sex differences persist within subgroups, requiring additional explanations. In Table 3, the main coefficients (unhighlighted) reflect the associations between the independent variables and re-perpetration rates for female perpetrators. Associations for male perpetrators are calculated by adding the main coefficient for each variable to the corresponding interaction coefficient (highlighted in gray). For ease of comparison, we have included predicted probabilities of re-perpetration by group and sex in Figure 1 (same victim re-perpetration) and Figure 2 (new victim re-perpetration). We focus on these predicted probabilities in the results.

Table 3.

Interaction Models

| Same Victim | New Victim | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Perpetrator Characteristics | ||

| Male | −0.070 (0.008)*** | −0.054 (0.008)*** |

|

Race/ethnicity (reference=Non-Hispanic White) |

||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.030 (0.002)*** | 0.005 (0.002) |

| Hispanic | −0.027 (0.002)*** | 0.011 (0.002)*** |

| Other or multiple races | −0.075 (0.003)*** | −0.042 (0.003)*** |

| Non-Hispanic Black X Male | −0.002 (0.004) | −0.016 (0.003)*** |

| Hispanic X Male | −0.008 (0.003) | −0.033 (0.003)*** |

| Other or Multiple races X Male | 0.017 (0.004)*** | 0.002 (0.004) |

| Index incident characteristics | ||

| Any co-perpetrator | −0.011 (0.002)*** | −0.012 (0.002)*** |

| Any co-perpetrator X Male | 0.027 (0.003)*** | 0.021 (0.003)*** |

|

Relationship to victim (reference=biological parent) |

||

| Adoptive parent or legal guardian | −0.032 (0.008)*** | −0.006 (0.008) |

| Step-parent or parent’s partner | −0.084 (0.007)*** | −0.023 (0.006)*** |

| Foster parent | −0.148 (0.012)*** | −0.051 (0.011)*** |

| Relative | −0.102 (0.004)*** | −0.043 (0.004)*** |

| Other | −0.142 (0.006)*** | −0.065 (0.005)*** |

| Multiple relationships | −0.054 (0.007)*** | −0.031 (0.006)*** |

| Adoptive parent or legal guardian X Male | 0.045 (0.013)*** | 0.058 (0.012)*** |

| Step-parent or parent’s partner X Male | 0.067 (0.008)*** | 0.044 (0.007)*** |

| Foster parent X Male | 0.081 (0.022)*** | 0.081 (0.020)*** |

| Relative X Male | 0.049 (0.005)*** | 0.034 (0.005)*** |

| Other X Male | 0.105 (0.007)*** | 0.071 (0.006)*** |

| Multiple relationships X Male | 0.051 (0.008)*** | 0.042 (0.007)*** |

|

Maltreatment type (reference=physical abuse) |

||

| Sexual abuse | 0.005 (0.011) | 0.005 (0.010) |

| Neglect | 0.033 (0.006)*** | 0.019 (0.006)*** |

| Other maltreatment | 0.038 (0.008)*** | 0.009 (0.007) |

| Multiple types of maltreatment | 0.025 (0.006)*** | 0.017 (0.006)** |

| Sexual abuse X Male | 0.016 (0.012) | 0.015 (0.011) |

| Neglect X Male | −0.011 (0.008) | −0.008 (0.007) |

| Other maltreatment X Male | −0.013 (0.010) | 0.003 (0.009) |

| Multiple types of maltreatment X Male | −0.008 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.008) |

| Constant | 0.224 (0.007)*** | 0.288 (0.006)*** |

Notes: N=285,245. Linear probability coefficients. Standard errors (SE) in parentheses;

p<0.01

p<0.001;

State fixed effects and additive coefficients, including perpetrator age, number of victims, and age of youngest victim included (not shown). The interaction coefficients are highlighted in gray, the main coefficients are unhighlighted.

Figure 1.

Differences in Predicted Probabilities of Same Victim Re-Perpetration by Perpetrator Sex

Figure 2.

Differences in Predicted Probabilities of New Victim Re-Perpetration by Perpetrator Sex

On the whole, rates of re-perpetration remained lower for males than females in nearly all subgroups, with a similar pattern in direction and magnitude. For same victim re-perpetration, sex differences in probabilities of re-perpetration were largely similar across race/ethnic groups (3-6PP lower for males). Males with an index co-perpetrator were slightly more likely to re-perpetrate with the same victim than solo male perpetrators (.11 versus .13 predicted probability), whereas females with an index co-perpetrator were modestly less likely (.17 versus .16); thus, the male-female gap in same victim re-perpetration was −6 PP for solo perpetrators, versus −3 PP for co-perpetrators. Additionally, while the sex difference in same victim re-perpetration was large for those who were the biological parent of the victim in the index incident (−6PP), the sex difference was smaller (1-2PP higher probability), among those who were the adoptive parent or legal guardian, relative, or had multiple roles in the index incident, both favoring females. There were minimal sex differences in same victim re-perpetration for those who were the stepparent, parent’s partner, or foster parent in the index incident, despite significant interactions. Lastly, sex differences were fairly consistent (6-8PP) across maltreatment types.

For new victim re-perpetration, sex differences were slightly larger among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic perpetrators than for non-Hispanic White perpetrators, whereas patterns for index co-perpetration and relationship to victim were very similar to the same victim re-perpetration results (i.e., larger gap for index biological parents, smaller gap when a coperpetrator was involved). Sex differences in predicted probabilities of new victim re-perpetration were between 4 and 6 percentage points across maltreatment types.

Supplementary Models.

In Table A1, we display results predicting same victim re-perpetration among perpetrators with at least one victim under age eight at the index incident. While some coefficients differ slightly from our main models, the substantive story is very similar, suggesting that our results are not driven by children aging out of risk of child maltreatment.

Discussion

This study examined the rates and predictors of two forms of child maltreatment re-perpetration – victimization of the same child(ren) and victimization of a new child – among those with a first-time substantiated maltreatment offense in 2010. Over the 10-year period analyzed, we found substantial rates of both types of re-perpetration: 15 percent of first-time perpetrators re-maltreated their original victim(s) and 12 percent maltreated a new victim. Again, we caution that, because we can only track new maltreatment perpetration that is substantiated, this is undoubtedly a considerable underestimate.

Female perpetrators had consistently and meaningfully higher rates of both same victim and new victim re-perpetration. Lower overall risk of re-perpetration among males may reflect differential criminal justice system responses. When men commit maltreatment, they are more likely than women to face criminal charges (Kobulsky et al., 2021) and, if convicted, to be incarcerated (Hanrath & Font, 2020). Incarceration will, for the length of sentence, eliminate opportunities to re-perpetrate. In addition, for biological parents, criminal conviction and especially incarceration (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013) may increase the probability of permanent custody loss of both current and future children, thus reducing same victim and new victim re-perpetration opportunities. Because female-perpetrated violence is not taken as seriously as male-perpetrated violence (Carlyle et al., 2014; Espinoza & Warner, 2016; Hanrath & Font, 2020; Scarduzio et al., 2017), female perpetrators may be less likely to be convicted or incarcerated and thus maintain greater access to children than male perpetrators.

Furthermore, sex differences in re-perpetration largely reflect differences between biological mothers and fathers. Female perpetrators were more likely to be the biological parent of their initial victim(s) than male perpetrators. Moreover, biological mothers were at higher risk of re-perpetration than females in other caregiver roles, whereas biological fathers were at lower risk than males in other caregiver roles. This is consistent with the fact that biological mothers remain the most common primary caregiver of children (DiLauro, 2004; Moon & Hoffman, 2008; Yavorsky et al., 2015), and – because single parenthood is a risk factor for maltreatment (Stith et al., 2009), households led by single biological mothers are particularly overrepresented in the population of maltreatment perpetrators. Thus, biological mothers are the most common primary caregivers of their children even after a maltreatment event, including of any children born after the event. This is still the case, even though mother-perpetrated physical abuse may be associated with disproportionately higher risk of removal than father-perpetrated maltreatment (both physical abuse and neglect) (Crawford & Bradley, 2016).

In contrast, the relationship to initial victim(s) did not clearly differentiate re-perpetration risk for males, meaning that unlike females, males were not considerably more likely to be the biological parent of their initial victim(s). This likely reflects that access to or co-residence with children is not as closely tied to biological parenthood among males. That is, males, and especially the disadvantaged males at highest risk for child maltreatment, frequently co-reside with unrelated children to whom they have substantial access (Berger & Bzostek, 2014).

Females with a co-perpetrator at their index case were less likely to re-perpetrate than female perpetrators who initially acted alone. Co-perpetration and father-perpetrated maltreatment are frequently associated with intimate partner-violence (Dixon et al., 2007; Kobulsky et al., 2020), so some female-perpetrated maltreatment may occur because women have been coerced by a male partner or have failed to protect children from the maltreatment of an abusive partner. If CPS intervention results in the dissolution of the abusive relationship with their co-perpetrator (e.g., as a condition of maintaining custody of the children), this subset of female perpetrators may be unlikely to engage in additional maltreatment. Both the sex disparities in re-perpetration as well as sex-specific patterns for co-perpetration point to the need for data collection on details of safety plans, including sole custody granted to the non-maltreating caregiver, orders of protection against the perpetrator, or incarceration of the perpetrator.

Beyond sex differences in re-perpetration, we found modestly lower rates of same victim re-perpetration among Black, Hispanic, and other race perpetrators, and lower rates of new victim re-perpetration among Hispanic and other race perpetrators, compared with non-Hispanic White perpetrators. Covariates included in our models were unable to account for the majority of racial differences in re-perpetration, indicating an area in need of further research. There are numerous possible explanations for this difference that are beyond the scope of this study. First, a lower threshold for substantiation among non-White perpetrators could result in a comparatively low-risk pool of first-time non-White perpetrators relative to White perpetrators. However, there is relatively little evidence of racial or ethnic bias in substantiation rates conditional on risk (Drake et al., 2011; Font et al., 2012). Second, it is possible that services or interventions are more effective in modifying risk of re-perpetration among non-White perpetrators. This seems unlikely to play a major role, however, given the lack of effectiveness evidence for most in-home interventions provided through CPS (Jonson-Reid et al., 2017). Third, the nature of maltreatment brought to the attention of CPS may vary across groups in ways not observable in this study (e.g., different manifestations of neglect). Lastly, and perhaps most likely, there may be higher rates of parent-child separation following perpetration by non-Whites – this separation may occur through formal foster care (child removal), informal (voluntary) kinship care, incarceration of a parent, a custody order, or informal gatekeeping by the custodial parent. Although (in recent years) disparities in rates of formal foster care entry, conditional on substantiated maltreatment, are quite small (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020a, 2020b), less is known about disparities in voluntary kinship arrangements (Gupta-Kagan, 2020), custody decisions, or parental gatekeeping behaviors. Disparities in incarceration are large overall (Wildeman, 2009), though perhaps less so in the context of the heavily-disadvantaged CPS-involved population. Nevertheless, disparate rates of parent-child separation (beyond foster care placement) following CPS involvement is an area ripe for future research.

Finally, we found that same victim re-perpetration maltreatment is more common among perpetrators of neglect and sexual abuse than perpetrators of physical abuse, and that perpetrators who commit multiple types of abuse are also more likely to re-perpetrate than those who only commit one type of abuse. We also confirmed previous findings that perpetrators with multiple victims are more likely to re-victimize the same children (White et al., 2015) than those with only one victim at the index incident, and that compared to other victim-perpetrator relationships, biological parents are the most common repeat perpetrators (Black et al., 2001; Brown et al., 1998; Connelly & Straus, 1992; Damashek et al., 2013; Hawkins & Duncan, 1985). Consistent with age patterns in overall maltreatment rates (Stith et al., 2009; Yi et al., 2020), same victim re-perpetration declines with both the age of the perpetrator and the age of the victims, though the coefficient for perpetrator age was quite small and of little clinical relevance. Decreases associated with victim age may reflect both an inverse association between victim age and the propensity for CPS to substantiate an allegation (Font & Maguire-Jack, 2019), as well older children being comparatively less dependent on caregivers for basic care.

Limitations

Our results advance knowledge of child maltreatment re-perpetration in several areas. However, we note important limitations of this study. First, a number of states do not provide reliable or complete data to NCANDS on key elements. Specifically, the quality of NCANDS identifiers has improved over time, but some states nevertheless needed to be excluded due to an inability to reliably count unique perpetrators or differentiate new and same victims. Thus, our sample is not representative of the entire nation. Similarly, due to unreliable or missing data on various risk factors that may inform re-perpetration risk, such as the presence of domestic violence, we cannot address the various explanations for sex, race, or other sociodemographic differences in re-perpetration. Of particular note, we could not measure the severity of the maltreatment in the index incident, subsequent criminal justice involvement of the perpetrators, or the family structure at the index incident or following incidents. We also could not effectively address the extent to which differences in levels, quality, or effectiveness of post-investigative services might explain the results we found. Third, identifiers for children and perpetrators are not stable across states, so these data underestimate rates of re-perpetration overall. Fourth, our sample focused exclusively on substantiated cases of child maltreatment, which is a flawed measure of maltreatment occurrence, and may be adversely associated with re-perpetration (Way et al., 2001); as such, our calculations underestimate the rate of recidivism. Fifth, because the risk of child maltreatment ends when a victim turns 18, we are limited in our examination of same victim re-perpetration among perpetrators with older victims. We nevertheless included perpetrators with victims of all ages in our analysis in order to maintain a more representative sample, as patterns of maltreatment differ for young children (Font & Maguire-Jack, 2019). Lastly, although we found many significant predictors of re-perpetration, which may be due to our large sample, most coefficients are not substantively large, and therefore the factors associated with maltreatment re-perpetration merit continuing research.

Implications and Conclusions

Our study suggests similar rates of new victim re-perpetration and same victim re-perpetration – 12% versus 15%. Although CPS agencies have the capacity to track perpetrator histories through central registries and internal case record systems, prior perpetration information is primarily used for two purposes. First, a common use of perpetration records is to screen individuals who are being considered as prospective guardians, foster parents, or adoptive parents, or as applicants for jobs in child-serving roles (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014). This is a mechanism to reduce risk of maltreatment for children living apart from their biological parents and for children receiving daycare, schooling, or other services outside the home. Second, the decision to provide services following a substantiated investigation is often based on the ongoing risk of harm to a specific victim by the perpetrator; thus, the perpetrators’ prior acts, particularly if egregious, may inform the nature and scope of intervention (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2012). Yet, CPS often mitigates risk to an individual child without addressing the risk posed by the perpetrator to children more generally, including future biological children and other members of the community (e.g., where the perpetrator is removed from the child’s household, but receives no treatment or services). But, given that perpetrators are almost equally likely to maltreat a new victim, evaluation and redress of perpetrators’ ongoing risk to children other than their original victim(s) is needed. Such efforts could take the form of voluntary services to perpetrators, as well as advancing technologies such as birth match (Shaw et al., 2013) to identify when new children are born to persons who may pose an ongoing risk of harm.

Our results further suggest a need to revisit evaluation measures, particularly in the Child and Family Services Reviews, that only capture re-victimization. Given that the perpetrators are commonly the target of intervention services (particularly in in-home maltreatment cases), re-perpetration rates should be reported in federal annual reports and semi-annual evaluations (e.g., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018a, 2021). Of great concern, this study had to omit several states that appeared not to consistently track perpetrators, raising questions about their capacity to use prior perpetration in case-level decisions. Furthermore, there are no unique identifiers for alleged perpetrators, despite reporting unique identifiers for alleged victims. Moreover, our results suggest higher rates of re-perpetration for women and non-Hispanic Whites. It is possible that this reflects greater intervention by the criminal justice system for male and non-White perpetrators (e.g., an incapacitation effect reflecting higher rates of incarceration) but lack of integration between CPS and criminal justice system data inhibit exploration of this possibility (Font & Kennedy, 2022). The quality of data available for studying perpetrator characteristics and patterns is highly limited and warrants greater focus as states move toward Comprehensive Child Welfare Information Systems (CCWIS) (Federal Register, 2016).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge assistance provided by the Population Research Institute at Penn State University, which is supported by an infrastructure grant by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025). Data used within this analysis were provided through a data license with the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN). Neither the collector of the original data, funding agency, nor the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Appendix

Table A1.

Model with Victims 8 and Younger

| Same Victim b(SE) |

|

|---|---|

| Perpetrator Characteristics | |

| Male | −0.063 (0.002)*** |

|

Race/ethnicity (reference=Non-Hispanic White) |

|

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.038 (0.002)*** |

| Hispanic | −0.039 (0.002)*** |

| Other or multiple races | −0.080 (0.003)*** |

| Age | −0.002 (0.000) *** |

| Index incident characteristics | |

| Any co-perpetrator | 0.005 (0.002) |

| Number of victims | 0.023 (0.001)*** |

| Age of youngest victim | −0.004 (0.000)*** |

|

Relationship to victim (reference=biological parent) |

|

| Adoptive parent or legal guardian | −0.030 (0.015) |

| Step-parent or parent’s partner | −0.038 (0.004)*** |

| Foster parent | −0.150 (0.015)*** |

| Relative | −0.100 (0.004)*** |

| Other | −0.094 (0.005)*** |

| Multiple relationships | −0.023 (0.004)*** |

|

Maltreatment type (reference=physical abuse) |

|

| Sexual abuse | 0.025 (0.007)*** |

| Neglect | 0.032 (0.005)*** |

| Other maltreatment | 0.041 (0.007)*** |

| Multiple types of maltreatment | 0.025 (0.005)*** |

| Constant | 0.236 (0.007)*** |

Notes: N=188,301. Linear probability coefficients. Standard errors (SE) in parentheses;

p<0.01

p<0.001;

RRR = Relative Risk Ratio

State fixed effects included (not shown)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The NCANDS dataset only tracks substantiated cases of maltreatment, so we were limited to substantiated cases only given our dataset.

Connecticut and Washington did not specify the type of parent perpetrators were to victims and Louisiana identified few perpetrator-victim relationships. Oregon and Georgia did not report data in fiscal year 2010

It is important to note that this paper discusses substantiated re-perpetration exclusively, meaning that it does not capture all potential revictimization of a child.

NCANDS bottom-codes perpetrator age at 18 and top-codes it at 70, so our sample likely contains some younger and older perpetrators.

Other abuse includes both emotional maltreatment, imminent risk of harm, and other state-specific categories of maltreatment.

Twenty percent of perpetrators re-perpetrated a victim in at least one category and seven percent of perpetrators maltreated both a new and a same victim, but these outcomes are not handled separately in our analyses.

References

- Bader SM, Welsh R, & Scalora MJ (2010). Recidivism Among Female Child Molesters. Violence and Victims, 25(3), 349–362. 10.1891/0886-6708.25.3.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Solomon PL, & Gelles RJ (2009). Multiple child maltreatment recurrence relative to single recurrence and no recurrence. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(6), 617–624. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, & Bzostek SH (2014). Young adults’ roles as partners and parents in the context of family complexity. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654( 1), 87–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, & Font SA (2015). The role of the family and family-centered programs and policies. Future of Children, 25(1), 155–176. 10.1353/foc.2015.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DA, Heyman RE, & Smith Slep AM (2001). Risk factors for child physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(2), 121–188. 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00021-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, & Salzinger S (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11), 1065–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, Scarduzio JA, & Slater MD (2014). Media portrayals of female perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(13), 2394–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Rhee S, & Berthold SM (2008). Child abuse and neglect in Cambodian refugee families: Characteristics and implications for practice. Child Welfare, 87(1), 141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2012). Reasonable efforts to preserve or reunify families and achieve permanency for children (State Statutes). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2013). Grounds for involuntary termination of parental rights. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/statutes/groundtermin.cfm [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2014). Establishment and maintenance of central registries for child abuse reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/statutes/centreg.cfm [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Bergeron N, Katz KH, Saunders L, & Tebes JK (2007). Re-referral to child protective services: The influence of child, family, and case characteristics on risk status. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(5), 573–588. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CD, & Straus MA (1992). Mother’s age and risk for physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16(5), 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford B, & Bradley MS (2016). Parent gender and child removal in physical abuse and neglect cases. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, & Tekin E (2012). Understanding the cycle childhood maltreatment and future crime. Journal of Human Resources, 47(2), 509–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damashek A, Nelson MM, & Bonner BL (2013). Fatal child maltreatment: Characteristics of deaths from physical abuse versus neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(10), 735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLauro MD (2004). Psychosocial factors associated with types of child maltreatment. Child Welfare, 83(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Browne K, & Ostapuik E (2007). The co-occurrence of child and intimate partner maltreatment in the family: Characteristics of the violent perpetrators. Journal of Family Violence, 22(8), 675–689. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon TL, & Maddox KB (2005). Skin Tone, Crime News, and Social Reality Judgments: Priming the Stereotype of the Dark and Dangerous Black Criminal1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(8), 1555–1570. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02184.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, & Jonson-Reid M (2011). Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics, 127(3), 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, & Jonson-Reid M (2000). Substantiation, risk assessment and involuntary versus voluntary services. Child Maltreatment, 5(3), 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, & Chung S (2003). Substantiation and Recidivism. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 248–260. 10.1177/1077559503258930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Lee SM, & Jonson-Reid M (2009). Race and child maltreatment reporting: Are Blacks overrepresented? Children and Youth Services Review, 31(3), 309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour S, Lavergne C, Larrivée M-C, & Trocmé N (2008). Who are these parents involved in child neglect? A differential analysis by parent gender and family structure. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(2), 141–156. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza RC, & Warner D (2016). Where do we go from here?: Examining intimate partner violence by bringing male victims, female perpetrators, and psychological sciences into the fold. Journal of Family Violence, 31(8), 959–966. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. (2016). Comprehensive child welfare information system (Vol. 81, No. 106). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-06-02/pdf/2016-12509.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferleger N, Glenwick DS, Gaines RRW, & Green AH (1988). Identifying correlates of reabuse in maltreating parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72(1), 41–49. 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluke JD, Yuan Y-YT, Hedderson J, & Curtis PA (2003). Disproportionate representation of race and ethnicity in child maltreatment: Investigation and victimization. Children and Youth Services Review. [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, & Berger LM (2015). Child maltreatment and children’s developmental trajectories in early to middle childhood. Child Development, 86(2), 536–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, Berger LM, & Slack KS (2012). Examining racial disproportionality in child protective services case decisions. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(11), 2188–2200. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, & Kennedy R (2022). The Centrality of Child Maltreatment to Criminology. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), null, 10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-120220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, & Maguire-Jack K (2019). The organizational context of substantiation in child protective services cases. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, in press. 10.1177/0886260519834996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, Maguire-Jack K, & Dillard R (2020). The decision to substantiate allegations of child maltreatment. In Decision Making and Judgement in Child Welfare and Protection: Theory, Research, and Practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Bradford J, Firestone P, & Curry S (2000). Recidivism of child molesters: A study of victim relationship with the perpetrator. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(11), 1485–1494. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00197-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta-Kagan J (2020). America’s Hidden Foster Care System. Stanford Law Review, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Lee Y, Lee SJ, Waldfogel J, & Rathouz PJ (2009). Fathers and Maternal Risk for Physical Child Abuse. Child Maltreatment, 14(2), 277–290. 10.1177/1077559509337893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrath L, & Font S (2020). Gender Disparity in Pennsylvania Child Abuse and Neglect Sentencing Outcomes. Crime & Delinquency, 66(12), 1703–1728. 10.1177/0011128720930670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, & Hackett W (2008). Decision points in child welfare: An action research model to address disproportionality. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(2), 199–215. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins WE, & Duncan DF (1985). Perpetrator and Family Characteristics Related to Child Abuse and Neglect: Comparison of Substantiated and Unsubstantiated Reports. Psychological Reports, 56(2), 407–410. 10.2466/pr0.1985.56.2.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays S (1996). The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, & Weis JG (1979). Correlates of Delinquency: The Illusion of Discrepancy between Self-Report and Official Measures. American Sociological Review, 44(6), 995–1014. JSTOR. 10.2307/2094722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hindley N (2006). Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91(9), 744–752. 10.1136/adc.2005.085639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, & Kotch JB (2005). Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 479–492. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Chung S, Way I, & Jolley J (2010). Understanding service use and victim patterns associated with re-reports of alleged maltreatment perpetrators. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(6), 790–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Chung S, & Way I (2003). Cross-type recidivism among child maltreatment victims and perpetrators. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(8), 899–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Kohl P, Guo S, Brown D, McBride T, Kim H, & Lewis E (2017). What do we really know about usual care child protective services? Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JM, & Schwalbe C (2010). The timing to and risk factors associated with child welfare system recidivism at two decision-making points. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(1), 1035–1044. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Drake B (2019). Cumulative Prevalence of Onset and Recurrence of Child Maltreatment Reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(12), 1175–1183. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 274–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott T, & Donovan K (2010). Disproportionate representation of African-American children in foster care: Secondary analysis of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, 2005. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(5), 679–684. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobulsky JM, & Wildfeuer R (2019). Child Protective Services-Investigated Maltreatment by Fathers: Distinguishing Characteristics and Disparate Outcomes. 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobulsky JM, Wildfeuer R, Yoon S, & Cage J (2021). Distinguishing Characteristics and Disparities in Child Protective Services-Investigated Maltreatment by Fathers. Child Maltreatment, 26(2), 182–194. 10.1177/1077559520950828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2009). Time to Leave Substantiation Behind: Findings From A National Probability Study. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 17–26. 10.1177/1077559508326030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutateladze BL, Andiloro NR, Johnson BD, & Spohn CC (2014). Cumulative Disadvantage: Examining Racial and Ethnic Disparity in Prosecution and Sentencing. Criminology, 52(3), 514–551. 10.1111/1745-9125.12047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ (2013).Paternal and Household Characteristics Associated With Child Neglect and Child Protective Services Involvement. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(2), 171–187. 10.1080/01488376.2012.744618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Guterman NB, & Lee Y (2008). Risk factors for paternal physical child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(9), 846–858. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Romano PS, Putnam-Hornstein E, Thurston H, Dharmar M, & Joseph JG (2017). Risk factors for fatal and non-fatal child maltreatment in families previously investigated by CPS: A case-control study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 222–232. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon M, & Hoffman CD (2008). Mothers’ and Fathers’ Differential Expectancies and Behaviors: Parent × Child Gender Effects. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 164(3), 261–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RE, & Truman JL (2019). Criminal Victimization, 2019. U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Program, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JM, Johnson WE, D’Aunno LE, & Thornton HL (2005). Fathers in child welfare: Caseworkers’ perspectives. Child Welfare, 84(3), 387–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palusci VJ, & Ilardi M (2020). Risk Factors and Services to Reduce Child Sexual Abuse Recurrence. Child Maltreatment, 25(1), 106–116. 10.1177/1077559519848489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman JF, & Buckley RR (2006). Comparing maltreating fathers and mothers in terms of personal distress, interpersonal functioning, and perceptions of family climate. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(5), 481–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Ahn E, Prindle J, Magruder J, Webster D, & Wildeman C (2021). Cumulative Rates of Child Protection Involvement and Terminations of Parental Rights in a California Birth Cohort, 1999–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 111(6), 1157–1163. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Needed B, King B, & Johnson-Motoyama M (2013). Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 33–46. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, Babchishin L, Marquis R, & Fréchette S (2015). Childhood maltreatment and educational outcomes. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(4), 418–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarduzio JA, Carlyle KE, Harris KL, & Savage MW (2017). “Maybe She Was Provoked” Exploring Gender Stereotypes About Male and Female Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women, 23(1), 89–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer PG, & Ewigman BG (2005). Child deaths resulting from inflicted injuries: Household risk factors and perpetrator characteristics. Pediatrics, 116(5), e687–e693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TV, Barth RP, Mattingly J, Ayer D, & Berry S (2013). Child welfare birth match: Timely use of child welfare administrative data to protect newborns. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 7(2), 217–234. 10.1080/15548732.2013.766822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinanan AN (2011). The Impact of Child, Family, and Child Protective Services Factors on Reports of Child Sexual Abuse Recurrence. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20(6), 657–676. 10.1080/10538712.2011.622354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D, & Åsberg K (2012). Effectiveness of child protective services interventions as indicated by rates of recidivism. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2311–2318. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, Som A, McPherson M, & Dees J (2009). Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Taillieu TL, Cheung K, Sareen J, Katz LY, Tonmyr L, & Afifi TO (2019). Caregiver vulnerabilities associated with the perpetration of substantiated child maltreatment in Canada: Examining the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) 2008. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260519889941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018a). Child and Family Services Reviews Aggregate Report: Round 3: FYs 2015-2016 (Federal CFSR Aggregate Report, pp. 1–55). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Administration of Children & Families. Administration on Children, Youth, and Families. Children’s Bureau. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/cfsr-aggregate-report-round-3-fys-2015-2016 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018b). National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File: FFY 2018 [dataset]. Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Available from the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect Web Site: http://Www.Ndacan.Cornell.Edu. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020a). Child Maltreatment 2018. Child Maltreatment, 274. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020b). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2019 estimates as of June 23, 2020 (No. 27). https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport27.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Child Maltreatment 2019. Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2019.pdf

- Way I, Chung S, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2001). Maltreatment perpetrators: A 54-month analysis of recidivism ✫. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(8), 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White OG, Hindley N, & Jones DP (2015). Risk factors for child maltreatment recurrence: An updated systematic review. Medicine, Science and the Law, 55(4), 259–277. 10.1177/0025802414543855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C (2009). Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography, 46(2), 265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, & Lee H (2014). The Prevalence of Confirmed Maltreatment Among US Children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 706–713. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskaya S, Greenbaum PE, & Berson IR (2009). Profiles of child maltreatment perpetrators and risk for fatal assault: A latent class analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 24(5), 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Yavorsky JE, Dush CMK, & Schoppe-Sullivan SJ (2015). The Production of Inequality: The Gender Division of Labor Across the Transition to Parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 77(3), 662–679. 10.1111/jomf.12189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Y, Edwards FR, & Wildeman C (2020). Cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment and foster care placement for US children by race/ethnicity, 2011–2016. American Journal of Public Health, 110(5), 704–709. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski DS (2009). Child maltreatment and adult socioeconomic well-being. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(10), 666–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]