Abstract

Identifying protein biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been challenging. Most previous studies have used individual proteins or preselected protein panels measured in blood samples. Mass spectrometry proteomic studies of lung tissue have been based on small sample sizes. We used mass spectrometry proteomic approaches to discover protein biomarkers from 150 lung tissue samples representing COPD cases and controls. Top COPD-associated proteins were identified based on multiple linear regression analysis with false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. Correlations between pairs of COPD-associated proteins were examined. Machine learning models were also evaluated to identify potential combinations of protein biomarkers related to COPD. We identified 4,407 proteins passing quality controls. Twenty-five proteins were significantly associated with COPD at FDR < 0.05, including interleukin 33, ferritin (light chain and heavy chain), and two proteins related to caveolae (CAV1 and CAVIN1). Multiple previously reported plasma protein biomarkers for COPD were not significantly associated with proteomic analysis of COPD in lung tissue, although RAGE was borderline significant. Eleven pairs of top significant proteins were highly correlated (r > 0.8), including several strongly correlated with RAGE (EHD2 and CAVIN1). Machine learning models using Random Forests with the top 5% of protein biomarkers demonstrated reasonable accuracy (0.707) and area under the curve (0.714) for COPD prediction. Mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis of lung tissue is a promising approach for the identification of biomarkers for COPD.

Keywords: biomarkers, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, machine learning, mass spectrometry, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a major public health problem diagnosed by persistent airflow obstruction, is associated with chronic lung inflammation that can persist decades after smoking cessation (1). In the United States, COPD is the fourth leading cause of death (2) and affects more than 16 million adults (3).

COPD is typically diagnosed using spirometry; however, chronic airflow obstruction results from a heterogeneous combination of emphysema, small airway disease, and large airway disease (4). Molecular biomarkers could potentially assist in COPD diagnosis. COPD also has variable rates of onset and progression, and molecular biomarkers could identify individuals at high risk for disease development or progression, who may be candidates for more aggressive therapeutic interventions (5–7).

To identify molecular biomarkers for COPD pathogenesis and/or progression, various Omics data types have been used, including transcriptomics, epigenetics, metabolomics, and proteomics (8). As key molecular agents, proteins are of particular interest as potential disease biomarkers. Previous studies have been performed using both single and multiple protein biomarkers. Single protein biomarkers associated with COPD have included SFTPD (surfactant protein D, encoded by SFTPD) (9), fibrinogen (encoded by FGA, FGB, and FGG) (10, 11), CC-16 (club cell secretory protein-16, encoded by SCGB1A1) (12), sRAGE (advanced glycosylation end-product specific receptor, encoded by AGER) (13), and IL-6 (interleukin 6, encoded by IL6) (14).

Protein biomarker panels measured in blood samples have also been investigated in COPD. In 2007, a panel of 24 serum protein biomarkers was shown to be correlated with important clinical outcomes of COPD including forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), carbon monoxide transfer factor, 6-min walk distance, and exacerbation frequency (15). In 2011, four plasma biomarkers (α2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, and hemopexin) were able to distinguish patients with asthma, COPD, and normal controls (16). More recently, larger panels of protein biomarkers have been associated with COPD severity (17) and exacerbations (18). However, most previous protein biomarker studies in COPD have utilized preselected protein biomarkers rather than unbiased assessments of all available proteins, and they have focused on blood samples rather than lung samples. A smaller number of studies have used mass spectrometry approaches for large-scale proteomic assessments in lung tissue samples, but their sample sizes have been limited (19–21).

We hypothesized that mass spectrometry analysis of lung tissue samples in COPD cases and smokers with normal spirometry would identify novel protein biomarkers for COPD. We assessed association of individual proteins with COPD case-control status, and we utilized machine learning methods to identify combinations of proteins associated with COPD. We also assessed the correlations between top protein biomarkers to understand potential biological relationships, and we compared our lung tissue protein biomarkers to previously reported COPD protein biomarkers from lung and blood. The integrated analyses not only identified new candidate COPD proteomic biomarkers, but also provided an initial step toward building predictive models for COPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed materials and methods are available in the Supplemental Data, including the overall workflow (Supplemental Fig. S1; all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16439025).

Study Population

We analyzed lung tissue samples from ex-smokers obtained during clinical thoracic surgery procedures. Most samples were obtained from the NHLBI Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC, n = 109, with 83 COPD cases and 26 control smokers). In addition, 43 subjects from a previously reported lung tissue population were also included (17 COPD cases and 26 control smokers) (22). LTRC participants provided written informed consent at each of the LTRC clinical centers. The Partners Human Research Committee IRB protocols for this study are 2013P000706/BWH and 2018P000186/PHS.

Sample Preparation and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Proteins were extracted from lung tissue through mechanical shearing followed by bead-mediated lysis in SDS buffer. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate by high resolution nano liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The raw mass spectra output files were analyzed using the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (23). The final protein quantity was estimated as the sum of up to the top three most abundant peptides among the proteotypic peptides (i.e., peptides that match to only a single protein), using the same peptides for each protein in each sample.

Biomarker Identification

Proteins with > 50% missing values and two outlier lung tissue samples based on missingness were removed (Supplemental Fig. S2). Principal component analyses were used to assess the data distribution before and after data preprocessing steps. After normalization, imputation, and batch effect correction, linear regression analyses were applied to identify COPD-associated proteomic biomarkers:

The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled at 5%. Additional linear regression models with covariates including body mass index (BMI), pack-years of smoking, and lung cancer status were also assessed (see Supplemental Tables S4–S9). Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlations between the top 5% of proteins associated with COPD; Bonferroni adjustments for these correlation analyses were performed, and we focused on pairwise correlations above 0.80.

Associations between COPD GOLD Stages and Proteomics

The associations between COPD GOLD stages and protein expression levels were evaluated by two methods:

Pairwise comparisons between each GOLD grade and control subjects were performed with t tests for COPD-associated proteins. For COPD-associated proteins, comparisons across GOLD stages within COPD subjects were also performed.

The associations between COPD GOLD stages and protein expression level were also evaluated using linear regression models in COPD cases as

Associations between FEV1% Predicted and Proteomics

The associations between FEV1% predicted and proteins in COPD cases were evaluated using linear regression model as

Machine Learning Analysis

Using the top 5% of proteins associated with COPD, we performed machine learning analysis using Random Forests, Naïve Bayes, and Elastic Net with nested fivefold cross-validation. For each machine learning model, the averaged accuracy, area under the curve in receiver-operator characteristic analysis (AUC), and feature importance were compared.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using the topGO algorithm was applied to the top 5% of proteins generated from the linear regression analyses to investigate potential related biological functions. Additional GO enrichment analyses with the same parameters were also applied to the top 5% of proteins positively and negatively associated with COPD.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

We included 152 lung tissue samples in our proteomics analysis. The clinical characteristics of these subjects are shown in Table 1. Clinical characteristics of COPD cases at different GOLD stages are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study population

| Controls | COPD Cases | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 52 | 100 |

| Age, yr | 65.83 (7.91) | 63.38 (8.31) |

| Sex (male/all) | 0.40 (21/52) | 0.44 (44/100) |

| Pack-years of smoking | 33.95 (19.74)* | 49.53 (26.85) |

| FEV1, % predicted | 101.29 (15.84)* | 35.18 (17.28) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.86 (0.57)* | 0.39 (0.14) |

| Race (white/all) | 1.00 (52/52) | 0.93 (93/100) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 28.34 (5.39)* | 25.99 (4.92) |

| Lung cancer, (cancer/all) | 0.85 (44/52)* | 0.31 (31/100) |

| COPD GOLD stage (number of subjects) | Not Applicable | GOLD Stage II: 21 |

| GOLD Stage III: 23 | ||

| GOLD Stage IV: 56 |

Values are means (SD) or n (%). BMI was not available for one subject. *P < 0.05 based on t test for quantitative variables and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Principal Component Analysis of Proteomic Data before and after Preprocessing

We applied principal component analysis to assess the proteomic data distribution during preprocessing (filtering, removing outliers, normalization and imputation, and adding surrogate variables for batch effect correction). The effects of removing outliers and exogenous factors are shown in Supplemental Fig. S3. After quality control, 4,407 proteins in 150 samples were available for analysis.

Linear Regression Analysis Results (Proteins with FDR < 0.05)

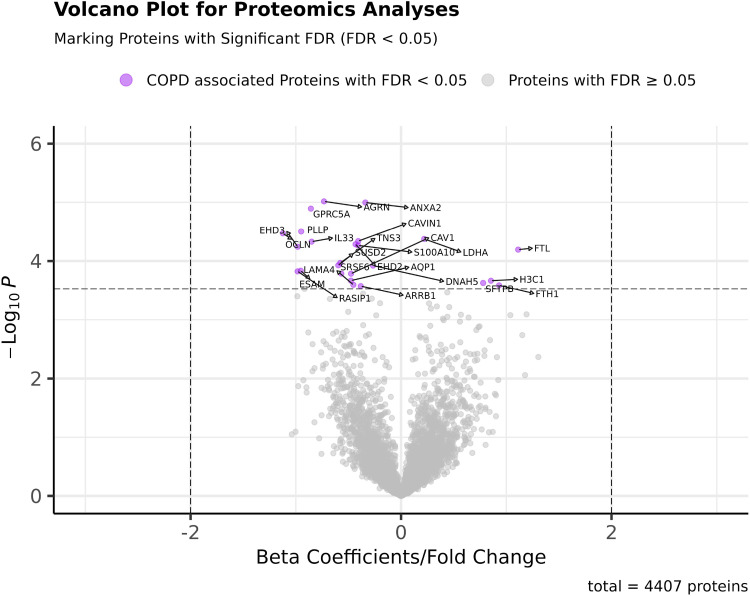

Linear regression models were established using the normalized and imputed datasets. The distribution of P values and regression β coefficients (fold changes) are presented in a volcano plot (Fig. 1).We identified 25 proteins that differed significantly between COPD and control lung tissue samples with FDR < 0.05. The FDR values and β coefficients of these proteins are shown in Table 2. Swarm plots comparing the residual expression level (removing effects of age, sex, batch effects and SVs) of the top 25 COPD-associated proteins are presented in Supplemental Fig. S4. In addition, we included proteins associated at a less conservative FDR threshold (FDR < 0.1) in Supplemental Table S10. Among the top 25 COPD-associated proteins, most were expressed at lower levels in lung tissue from the subjects with COPD. For example, the protein expression levels of Agrin, Annexin A2, Caveolin-1, and IL33 are negatively associated with COPD. Exceptions to this pattern were noted for the ferritin heavy and light chains, LDHA, and surfactant protein B, which were substantially higher in COPD cases. In the top 5% of proteins, there are 95 proteins positively and 125 proteins negatively associated with COPD. For comparison, we examined the linear regression results of several previously reported COPD protein biomarkers in Table 3. Trends for directionally consistent association (with P value < 0.05 but FDR > 0.05) were noted for RAGE, fibrinogen, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, TGM2, and macrophage capping protein. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S5, the proteins detected in our study and a previously reported mass spectrometry proteomics study in lung tissue [Brandsma C-A’s (21)] were generally similar; 3,498 proteins overlapped in both studies.

Figure 1.

Volcano plot for the P values and β coefficients of all proteins in COPD proteomics analyses (proteins with FDR < 0.05 are labeled with protein symbols). COPD proteomics biomarker identification was performed using linear regression models. Twenty-five proteins were identified to be associated with COPD with FDR < 0.05. The raw P values and β coefficients of each of the 4,407 proteins are shown in the volcano plot. Proteins significantly associated with COPD (FDR < 0.05) were marked in purple. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FDR, false discovery rate.

Table 2.

Top proteins associated with COPD based on linear regression analysis

| Gene Name | Protein Name | UniProt ID | Fdr | β Coefficient* | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGRN | Agrin | O00468 | 0.019 | −0.732 | 0.159 |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | P07355 | 0.019 | −0.339 | 0.074 |

| GPRC5A | Retinoic acid-induced protein 3 | Q8NFJ5 | 0.019 | −0.857 | 0.189 |

| PLLP | Plasmolipin | Q9Y342 | 0.023 | −0.949 | 0.22 |

| OCLN | Occludin | Q16625 | 0.023 | −1.123 | 0.262 |

| LDHA | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | P00338 | 0.023 | 0.220 | 0.052 |

| CAVIN1 | Caveolae-associated protein 1 | Q6NZI2 | 0.023 | −0.407 | 0.097 |

| IL33 | Interleukin-33 | O95760 | 0.023 | −0.850 | 0.202 |

| EHD2 | EH domain-containing protein 2 | Q9NZN4 | 0.023 | −0.432 | 0.104 |

| S100A10 | Protein S100-A10 | P60903 | 0.023 | −0.409 | 0.098 |

| EHD3 | EH domain-containing protein 3 | Q9NZN3 | 0.023 | −0.982 | 0.236 |

| FTL | Ferritin light chain | P02792 | 0.023 | 1.113 | 0.27 |

| TNS3 | Tensin-3 | Q68CZ2 | 0.035 | −0.578 | 0.145 |

| SUSD2 | Sushi domain-containing protein 2 | Q9UGT4 | 0.035 | −0.596 | 0.151 |

| DNAH5 | Dynein heavy chain 5, axonemal | Q8TE73 | 0.035 | −0.266 | 0.067 |

| ESAM | Endothelial cell-selective adhesion molecule | Q96AP7 | 0.038 | −0.953 | 0.244 |

| RASIP1 | Ras-interacting protein 1 | Q5U651 | 0.038 | −0.983 | 0.252 |

| SRSF6 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 6 | Q13247 | 0.038 | −0.568 | 0.146 |

| CAV1 | Caveolin-1 | Q03135 | 0.038 | −0.475 | 0.123 |

| AQP1 | Aquaporin-1 | P29972 | 0.045 | −0.476 | 0.125 |

| H3C1 | Histone H3.1 | P68431 | 0.045 | 0.854 | 0.225 |

| SFTPB | Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein B | P07988 | 0.047 | 0.780 | 0.207 |

| LAMA4 | Laminin subunit α-4 | Q16363 | 0.047 | −0.453 | 0.121 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin heavy chain | P02794 | 0.047 | 0.931 | 0.248 |

| ARRB1 | β-arrestin-1 | P49407 | 0.047 | −0.383 | 0.102 |

*Positive values mean increased risk of COPD and negative values mean decreased risk of COPD with increased protein levels. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3.

Linear regression results of selected previously reported COPD protein biomarkers

| Biomarker (Protein Name) |

Gene Name | Biosample Type | COPD GOLD Stage | COPD Stages Associated with Biomarkers | Selected Publications | Reported Protein Directions a,d | Current P value | Current FDR | Beta-coefficient (Standard error) in Current Studyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein D | SFTPD | Serum | Control :497 Stage II: 846 Stage III: 811 Stage IV: 229 |

COPD of all stages | Lomas et al. (9) | + | 0.302 | 0.772 | −0.456 (0.440) |

| Fibrinogen | FGA | Serum/plasma | Control: 8 Stage II-III: 9 Stage IV:20 |

COPD Stage IV | Philippot et al. (24) | + | 0.006 | 0.195 | 0.454 (0.162) |

| FGB | No GOLD stage information (392 cases) | Danesh et al. (10) | + | 0.076 | 0.501 | 0.33 (0.185) | |||

| FGG | + | 0.081 | 0.513 | 0.302 (0.172) | |||||

| Uteroglobin /CC-16(Club cell secretory protein -16) | SCGB1A1 | Serum | No stage information | Celli et al. (25) | − | 0.114 | 0.576 | 0.611 (0.384) | |

| Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor (RAGE) | AGER | Plasma | Controls: 42 Stage II: 14 Stage III: 28 Stage IV: 19 |

Not provided | Smith et al. (13) | − | 0.0004 | 0.063 | −0.676 (0.188) |

| Interleukin-6 | IL6 | Plasma | Not provided | Hurst et al. (14) | + | NAb | NAb | NAb | |

| Small ubiquitin-related modifier 2 | SUMO2 | Lung tissue | Controls: 8 Stage IV: 10 |

COPD Stage IV | Brandsma et al. (21) | − | 0.296 | 0.77 | −0.136 (0.13) |

| Collagenase 3/matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 | MMP13 | Lung tissue | Smoker control: 7 Non-smoker control:8 COPD (stage II):7 |

COPD Stage II | Lee et al. (19) | + | NAb | NAb | NAb |

| Glutaredoxin-3/thioredoxin-like 2 | GLRX3 | + | 0.143 | 0.612 | −0.428 (0.291) | ||||

| C-X-C motif chemokine 10 | CXCL10 | Lung tissue | Not Provided | Cornwell et al. (20) | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| C-C motif chemokine 2 | CCL2 | + | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Interleukin-10 | IL10 | + | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Interleukin-17A | IL17A | + | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 72 kDa type IV collagenase/matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 | MMP2 | − | 0.025 | 0.349 | −0.604 (0.266) | ||||

| Interstitial collagenase/matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 | MMP1 | + | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Macrophage-capping protein | CAPG | Lung tissue | Non-smoking Control: 9 Smoking control: 9 COPDI–II:8 COPD III–IV: 8 |

COPD of all stages | Ohlmeier et al. (26)d | + | 0.004 | 0.167 | 0.391 (0.133) |

| Cathepsin D | CTSD | COPD Stage I–II | +* | 0.174 | 0.652 | 0.307 (0.244) | |||

| Dihydropyrimidinase Like 2 | DPYSL2 | COPD of all stages | + | 0.006 | 0.205 | −0.114 (0.041) | |||

| Transglutaminase 2 | TGM2 | COPD Stage III–IV | +* | 0.0006 | 0.079 | 0.284 (0.081) | |||

| Tripeptidyl Peptidase 1 | TPP1 | COPD of all stages | +* | 0.442 | 0.848 | 0.099 (0.129) | |||

a,cDirections with increased protein levels: +/positive values mean increased risk of COPD; −/negative values, mean decreased risk of COPD. bNA, target proteins have not been identified in the current proteomics data set. dFor Ohlmeier et al.’s study, all five proteins were significantly upregulated in COPD subjects compared with nonsmoking controls. *Statistical differences in protein expression levels comparing smoking controls and at least one group of COPD subjects of different disease stages. The t test P values thresholds for associations between COPD different stages and nonsmoking controls were set as 0.05. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

To determine if any of the proteins were significantly associated with COPD severity, we performed association analyses on COPD GOLD stages and FEV1% predicted. As shown in Table S11, none of the 4,407 proteins were significantly associated with GOLD stage within COPD cases. The box plots showing the associations between top 25 COPD-associated protein levels and COPD GOLD Stages are presented in Supplemental Fig. S6. Proteins significantly associated with FEV1% predicted at FDR < 0.05 in all subjects are shown in Supplemental Table S12 (all subjects). Not surprisingly, most of these proteins were significantly associated with COPD case-control status. Within COPD cases only, two proteins (MZB1 and TRPM6) were associated with FEV1% predicted at FDR < 0.05 (Supplemental Table S13, COPD cases only). Of interest, a COPD GWAS gene product (DSP) was suggestively associated with FEV1% predicted in COPD cases (FDR = 0.063). Additional comparisons between the top 5% COPD-associated proteins, top 5% FEV1% predicted proteins in COPD cases, top 5% FEV1% predicted proteins in all subjects, and top 5% COPD GOLD stage-associated proteins in COPD cases are presented in a Venn diagram in Supplemental Fig. S7. There were five proteins that overlapped in these four groups: MZB1 (Q8WU39), MAVS (Q7Z434), ZN275 (Q9NSD4), LSAMP (Q13449), and AQP4 (P55087).

Correlations between Top Proteins from Linear Regression Analysis

We calculated the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients between the top 5% of COPD-associated proteins. Each pair of the top 5% of COPD-associated proteins (220 proteins) was regarded as a candidate protein pair. In total, the correlations between all possible 24,090 unique pairs of proteins were evaluated and the top pairwise correlations with absolute value of correlation coefficient > 0.8 and P value < 2 × 10−6 are shown in Table 4 (based on residuals after removing age, sex, batch effects, and surrogate variables). Also, we include a scatterplot to visualize the top correlations (Supplemental Fig. S8) and a histogram of pairwise correlations (Supplemental Fig. S9). Eleven high pairwise correlations (> 0.8) were noted. Some of the highest correlations involved proteins in shared molecular processes like FTL (ferritin light chain) and FTH1 (ferritin heavy chain), both part of ferritin, and CAV1 (Caveolin-1) and CAVIN1 (caveolae-associated protein 1), both involved in caveolae formation. Additional correlation pairs like EHD2 (EH domain-containing protein 2) and RAGE (advanced glycosylation end-product specific receptor), CAVIN1 and RAGE, and FTL and LGMN (legumain) were also identified.

Table 4.

Largest pairwise correlations between top 5% of proteins (after removing age, sex, batch effects, and surrogate variables) associated with COPD

| Protein 1 | Protein 2 | Correlation Coefficient, r | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferritin light chain | Ferritin heavy chain | 0.921 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Caveolae-associated protein 1 | Caveolin-1 | 0.888 | <2 × 10−6 |

| EH domain-containing protein 2 | Caveolae-associated protein 1 | 0.881 | <2 × 10−6 |

| EH domain-containing protein 2 | Caveolin-1 | 0.866 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Caveolae-associated protein 1 | Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor | 0.864 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Complement C3 | Ceruloplasmin | 0.844 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Annexin A2 | Protein S100-A10 | 0.836 | <2 × 10−6 |

| EH domain-containing protein 2 | Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor | 0.834 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Caveolae-associated protein 1 | Caveolae-associated protein 2 | 0.821 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Ferritin light chain | Legumain | 0.820 | <2 × 10−6 |

| Caveolin-1 | Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor | 0.820 | <2 × 10−6 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Machine Learning Protein Biomarker Prediction of COPD

Identifying the best model through cross-validation.

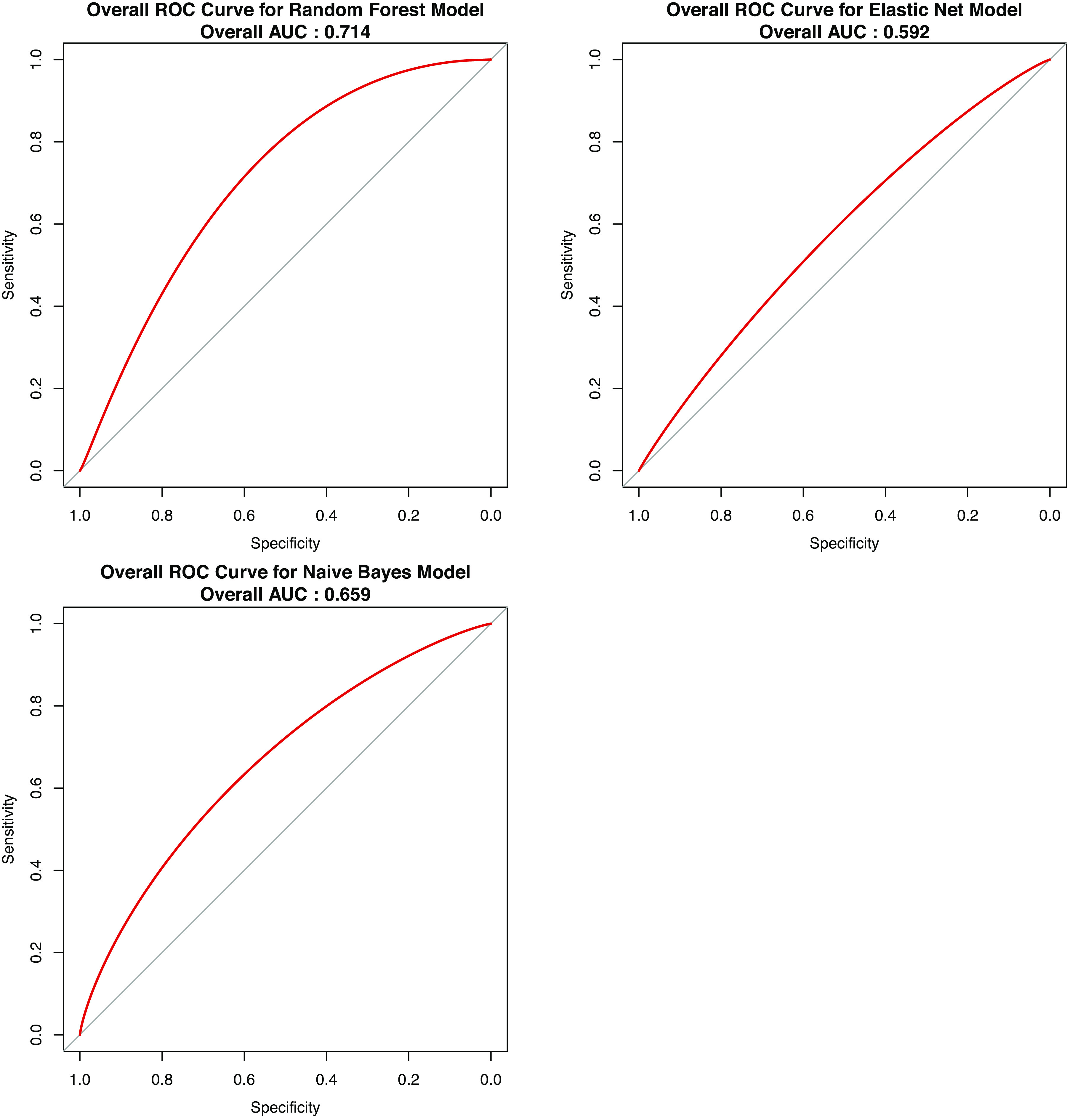

Our linear regression models only reflected the association between COPD and the expression level of one protein at a time. To study panels of proteins, we introduced machine learning models to establish multivariate prediction models for COPD. Three different machine learning methods were applied to develop predictive models distinguishing COPD subjects and controls: Random Forests, Naïve Bayes, and Elastic Net. Based on fivefold nested cross-validation (both inner loop and outer loop), we calculated the accuracy and AUC to evaluate their performance. After comparison, the Random Forest method has the best performance based on both accuracy and AUC (Table 5). The overall receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the three machine learning models are presented in Fig. 2.

Table 5.

Performance and comparison of three machine learning methods for COPD prediction

| Parameter | Naïve Bayes | Elastic Net | Random Forest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Averaged accuracy | 0.660 | 0.620 | 0.707 |

| Overall AUC | 0.659 | 0.592 | 0.714 |

AUC, area under the curve; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 2.

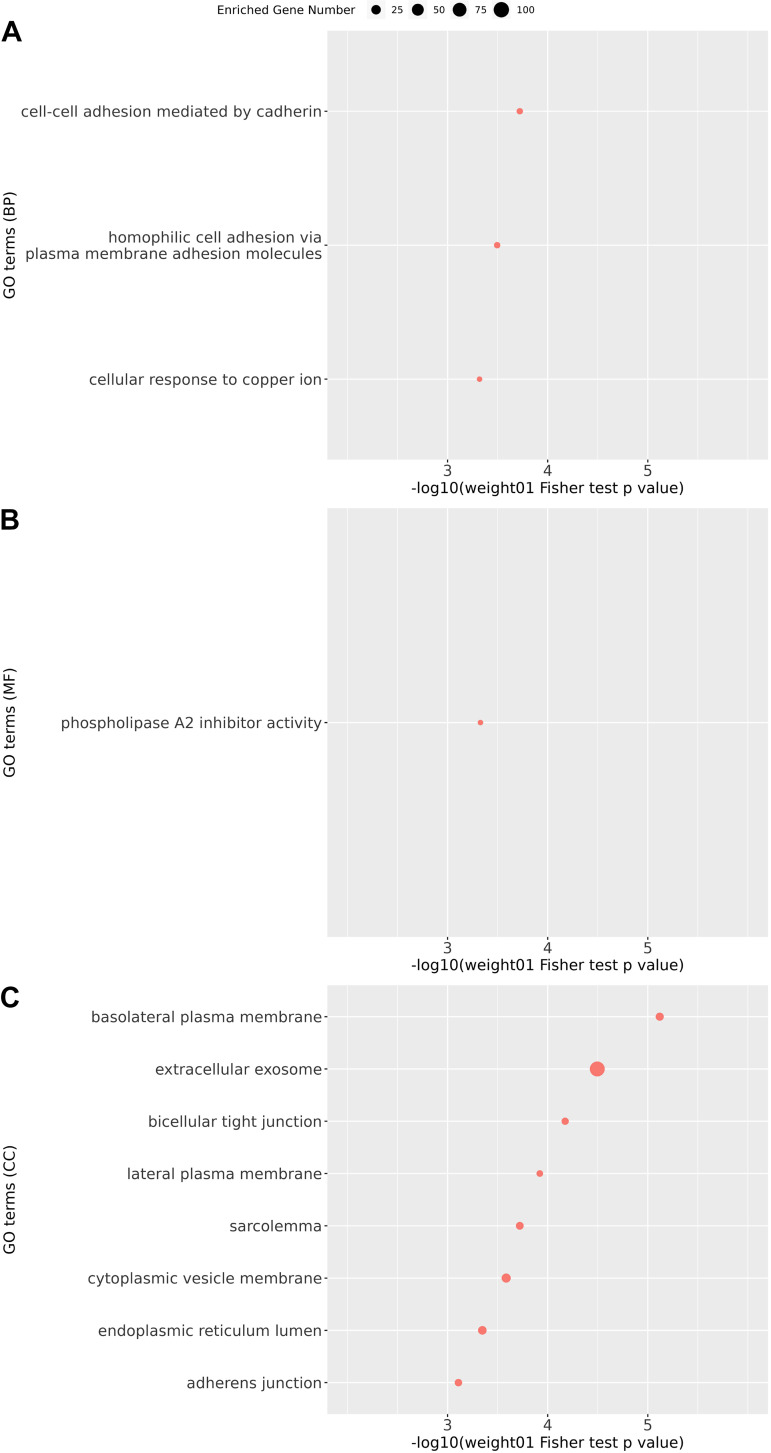

Gene ontology enrichment analysis on candidate protein biomarkers for COPD (top 5% of proteins according to FDR in linear regression analysis). GO enrichment analysis was performed on candidate protein biomarkers at three levels: biological processes (BP; A); molecular functions (MFs; B); and cellular components (CCs; C) with weight01 score threshold. The x-axis indicates the negative log value of weight01 Fisher test P value. The more significantly the GO term enriched, the higher the value on the x-axis. The y-axis indicates different GO terms ranked by the weight01 Fisher test P value. The size of the point in the figure indicates the number of genes significantly enriched in this GO term. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GO, gene ontology; FDR, false discovery rate.

Feature importance evaluation.

We evaluated the contribution of each Random Forest model feature to its COPD prediction performance. The feature importance of the top proteins and their original FDR in linear regression analysis are included in Table 6. Most proteins with high feature importance were also strongly associated in linear regression analyses. Some proteins with lower COPD association FDR also did achieve higher feature importance in Random Forests (e.g., BPIFA1, PPIL3). The feature importance was also presented as a plot in Supplemental Fig. S10.

Table 6.

Feature importance evaluation of Random Forest model

| Gene Name | Protein Name | UniProt ID | Random Forest Feature Importance | Univariate FDR | Univariate FDR Rank | Univariate P Value | Univariate P Value Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | P07355 | 68.324 (27.244) | 0.019 | 1 | 1.006E-05 | 2 |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A | P00338 | 60.758 (26.252) | 0.023 | 4 | 4.213E-05 | 6 |

| IL33 | Interleukin 33 | O95760 | 57.48 (33.691) | 0.023 | 4 | 4.689E-05 | 8 |

| BPIFA1 | BPI fold containing family A member 1 | Q9NP55 | 53.769 (33.17) | 0.077 | 34 | 6.116E-04 | 35 |

| CAV1 | Caveolin 1 | Q03135 | 50.591 (27.67) | 0.038 | 16 | 1.640E-04 | 19 |

| PPIL3 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase-like 3 | Q9H2H8 | 49.324 (17.118) | 0.134 | 54 | 1.649E-03 | 54 |

| GPRC5A | G protein-coupled receptor class C group 5 member A | Q8NFJ5 | 48.626 (14.654) | 0.019 | 1 | 1.279E-05 | 3 |

| AGRN | Agrin | O00468 | 47.213 (20.473) | 0.019 | 1 | 9.629E-06 | 1 |

| SRSF6 | Serine and arginine rich splicing factor 6 | Q13247 | 46.376 (15.608) | 0.038 | 16 | 1.639E-04 | 18 |

| SUSD2 | Sushi domain-containing 2 | Q9UGT4 | 46.272 (11.201) | 0.035 | 13 | 1.182E-04 | 14 |

| SH3BP1 | SH3 domain-binding protein 1 | Q9Y3L3 | 46.074 (18.258) | 0.091 | 38 | 8.375E-04 | 40 |

| FTL | Ferritin light chain | P02792 | 45.431 (22.038) | 0.023 | 12 | 6.398E-05 | 12 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin heavy chain 1 | P02794 | 45.108 (29.997) | 0.047 | 22 | 2.592E-04 | 24 |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium-binding protein A10 | P60903 | 43.535 (21.214) | 0.023 | 4 | 5.428E-05 | 10 |

| COL6A2 | Collagen type VI α 2 chain | P12110 | 42.427 (11.728) | 0.136 | 57 | 1.764E-03 | 57 |

| RPS8 | Ribosomal protein S8 | P62241 | 41.583 (28.111) | 0.094 | 42 | 8.918E-04 | 42 |

| KARS1 | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase 1 | Q15046 | 39.885 (26.54) | 0.103 | 46 | 1.078E-03 | 46 |

| DNAH5 | Dynein axonemal heavy chain 5 | Q8TE73 | 39.366 (16.554) | 0.035 | 13 | 1.195E-04 | 15 |

| EHD2 | EH domain-containing 2 | Q9NZN4 | 39.185 (16.001) | 0.023 | 4 | 5.191E-05 | 9 |

| GPAA1 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor attachment 1 | O43292 | 38.848 (32.254) | 0.156 | 70 | 2.605E-03 | 72 |

Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis with Candidate Protein Biomarkers for COPD

To investigate potential biological functions related to protein biomarkers, we chose the top 5% of COPD-associated proteins according to linear regression analysis for GO enrichment analysis (Supplemental Table S14). The enriched GO terms with P < 0.001 can be seen in Fig. 3. Of interest, extracellular exosomes, phospholipase A2 inhibitor activity, and cell adhesion were three of the top processes, suggesting that protein secretion in exosomes, phospholipase A2 inhibition, and cell adhesion could be relevant for COPD pathogenesis.

Figure 3.

Smoothed overall ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve for three machine learning models. The overall ROC value is included for each plot. Comparing the overall ROC curve, random forest model has the best performance with AUC = 0.714. AUC, area under the curve.

Additional analyses on the positively (n = 95) and negatively (n = 125) COPD-associated proteins in the top 5% of proteins were also performed. The enriched GO terms with P < 0.001 can be seen in Supplemental Figs. S11 and S12 with detailed results listed in Supplemental Tables S15 and S16. Substantial differences were observed, with positively COPD-associated proteins enriched for processes including neutrophil degranulation and extracellular exosomes, whereas negatively COPD-associated proteins were enriched for processes including plasma membranes and cell-cell adhesion by cadherin.

DISCUSSION

Although identification of protein biomarkers for COPD and COPD-related phenotypes has been a topic of intensive investigation, few studies have utilized mass spectrometry for large-scale assessments in lung tissue samples. We found multiple protein biomarkers associated with COPD in lung tissue. However, these lung tissue biomarkers were largely distinct from previously reported plasma protein biomarkers. Our analysis had four parts, focusing on the top proteins associated with COPD, correlations between top proteins, performance of machine learning models, and functional enrichment analysis.

Top Proteins Associated with COPD

We identified 25 protein biomarkers significantly associated with COPD. Other researchers have previously utilized mass spectrometry-based proteomics to investigate COPD in small sets of lung tissue samples. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 and thioredoxin-like 2 (GLRX3) were found to be elevated in COPD in a total study population of 22 subjects (19). We were unable to replicate the association to GLRX3, and we could not reliably detect MMP13. Cornwell et al. (20) studied 34 proteins in lung tissue from subjects with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE; n = 5), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF; n = 5), emphysema (n = 5), and normal lungs (n = 6). Inflammatory factors like IL-6 and CCL2 were upregulated in emphysema, whereas other proteins like MMP2 were downregulated (20); we found similar results for MMP2. Brandsma et al. (21) integrated proteomics and transcriptomics analysis (Control, n = 8; COPD cases, n = 10) and identified SUMO2 as a candidate COPD protein biomarker. Their study identified 327 differentially expressed proteins in COPD lung tissue; these included EHD3, EHD2, ANXA2, TNS3, RASIP1, ARRB1, and S100A10 from our top 25 proteins—which had consistent directions of effect in our study. Five COPD-specific proteins (TGM2, CAPG, Cathepsin D, TPP1, and DPYSL2) were identified in small sets of lung tissue samples from several different diseases (smoking control, nonsmoking control and IPF: n = 9 each; mild-moderate COPD, severe COPD, and α-1 antitrypsin deficiency: n = 8 each) by Ohlmeier et al. (26). We also identified TGM2 and CAPG with a consistent effect direction and nominally significant P value < 0.05. Apart from studies focusing on COPD, several lung tissue studies have evaluated proteomic signals for COPD subtypes (such as α-1 antitrypsin deficiency) (26) and COPD-associated phenotypes (such as COPD exacerbations) (27). With the limited clinical phenotyping available in our study population, we were unable to address these questions.

Among the 25 protein biomarkers in our analysis, several proteins have been previously implicated in COPD pathogenesis. IL33 is a cytokine serving as a mediator of chronic lung inflammation in COPD (28), but we found reduced IL33 levels in COPD lung samples. Agrin gene expression levels were found to be lower in lung tissue samples from severe COPD subjects (29), similar to our results. Plasma levels of the propeptide of surfactant protein B have been associated with COPD-related phenotypes (30). Previous studies (31–33) confirmed that depletion of GPRC5A can promote inflammatory reactions in lung tissue. GPRC5A protein levels were found to be downregulated in the lung tissue of patients with COPD (31), in agreement with our results. ANXA2 levels were found to be elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in COPD subjects (34), but we found lower levels in COPD lung tissue. Consistent with our results, Caveolin-1 has been reported to be downregulated in patients with COPD compared with normal controls in lung tissue samples (19). DNAH5 mutations can cause primary ciliary dyskinesia, which can include bronchiectasis, and DNA variations in the region may also be associated with total lung capacity in COPD subjects (35). Further studies of these candidate protein biomarkers may assist in understanding COPD pathogenesis.

Interestingly, increased levels of two ferritin peptides (FTL and FTH1) encoding the same protein complex were associated with COPD in our data set. Ferritin-associated proteins were previously reported to be upregulated in the BAL fluid (36) and alveolar macrophages (24) of smoking patients with COPD compared with healthy smokers, which is consistent with our results. Studies of one of the top COPD GWAS genes, IREB2, have focused on the role of iron-related pathways in COPD pathogenesis (37, 38). Determining whether these findings are related to the same underlying regulatory mechanisms in COPD pathogenesis requires further study.

The most consistently associated plasma protein biomarker with emphysema, RAGE (39), did not meet our FDR threshold for significance. However, RAGE was nominally significant (β = −0.68, P = 0.0004, FDR = 0.063), with lower expression levels in COPD lung tissue. Previous studies have confirmed negative correlations between the soluble isoform (sRAGE) and COPD (40, 41). Interestingly, the soluble and receptor forms of RAGE actually have opposite biological functions. Soluble RAGE plays a protective role against COPD pathogenesis (39), blocking the classic RAGE signaling pathway. However, the receptor form of RAGE promotes chronic inflammatory diseases including COPD (39, 42). The mixed detection of soluble and receptor RAGE may affect the quantitative results of mass spectrometry. We were unable to distinguish sRAGE and RAGE in our peptide analysis. Similarly, we were unable to identify different forms of another previously reported COPD-associated protein, ICAM1 (43). Further quantitative detection of different forms of RAGE and ICAM1, such as through more sensitive MS approaches utilizing targeted assays (44), may help clarify their significance.

We adjusted our association analyses of COPD case-control status in our study population of ex-smokers for age, sex, and technical factors. We did find confounding factors between COPD case-control status and pack-years (higher pack-years in COPD cases) and lung cancer diagnosis (more lung cancer in control subjects). Although some evidence for association to COPD of the top 25 proteins remained after adjusting for these confounders, the associations were often attenuated. Further investigation in other study populations will be required to determine if any of these top COPD-associated proteins are primarily related to lung cancer or smoking intensity.

Among our top 25 COPD-associated protein biomarkers, we did not find any significant associations with GOLD spirometry grade. Previous COPD proteomics studies, including the ECLIPSE study of SFTPD (no association with GOLD grade) (9) and the Ohlmeier study (only TGM2 was associated with GOLD grade) (26), have typically not found many significant associations with GOLD grade. This may reflect similar pathogenetic processes occurring across the spectrum of spirometric abnormality. Future proteomic studies addressing other approaches to dissect COPD heterogeneity (e.g., single cell proteomics) may lead to the identification of protein biomarkers for specific COPD subtypes (4).

Correlations between Top Proteins

Among the top 5% of proteins associated with COPD, we identified 11 pairs of highly correlated proteins (correlation coefficient > 0.8). Some of these proteins were parts of the same protein complex or biological process, such as FTL and FTH1 forming the ferritin complex, and CAVIN1 and CAV1 involved in caveolae formation. Of the 11 pairs of highly correlated proteins, EHD2 and CAVIN1 were each highly correlated with three other proteins, and both of them were correlated with RAGE (45, 46). Highly correlated proteins could directly contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD by participating in similar COPD-related pathways, and/or be coexpressed for reasons not due to COPD pathogenesis.

Performance of Machine Learning Models

To identify potential combinations of protein biomarkers related to COPD, we established three machine learning models using cross-validation. Considering both accuracy and AUC results, Random Forest provided the best performance in our proteomic data set. In several recent publications, Random Forest has been applied in multiple mass spectrometric-based proteomics studies with relatively good performance (47, 48).

Apart from the prediction performance evaluation, we also obtained an importance ranking of features that contributed to COPD prediction in Random Forest models. Most of the top proteins in this list, including AGRN (rank 1 in FDR list and rank 8 in feature importance list), ANXA2 (rank 2 in FDR list and rank 1 in feature importance list), GPRC5A (rank 3 in FDR list and rank 7 in feature importance list), and IL33 (rank 8 in FDR list and rank 3 in feature importance list) were also top features in the linear regression analysis. Apart from these proteins with FDR < 0.05, the previously widely reported COPD-associated gene AGER (which encodes RAGE) was also highlighted by the Random Forest model with rank 6. These results indicate that machine learning models verified the significance of many biomarkers identified in single protein analysis. Further investigation of proteins like PPIL3 (rank 6) and BPIFA1 (rank 4) that were highly important in Random Forest analysis but less significant in linear regression analysis may be warranted. Future studies of these machine learning models in plasma samples could lead to clinically relevant protein prediction models.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

GO enrichment analyses were performed on the top 5% of COPD-associated proteins for functional exploration. Several biological processes associated with cell adhesion were found, including GO:0044331 (cell-cell adhesion mediated by cadherin) and GO:0007156 (homophilic cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules). According to the Gene Ontology Resource (49), multiple cadherin-associated proteins (e.g., cadherin 1, cadherin 2, and cadherin 3) are included in these GO pathways. Cadherins are calcium-dependent proteins regulating cell adhesion processes (50). Furthermore, cadherin has also been reported to participate in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in smokers and subjects with COPD (51).

Among GO molecular function terms, only one term, GO:0019834 (phospholipase A2 inhibitor activity), was identified. COPD-associated oxidative stress was reported to promote the activity of phospholipase A2 (52, 53). The inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4 signaling, involving phospholipase A2, can inhibit neutrophilic inflammation in COPD (54).

Among GO terms for cellular components, GO:0070062 (extracellular exosomes) was identified. Extracellular exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicle released by multiple cell types. A systematic review of extracellular vesicles in the lung microenvironment noted that extracellular exosomes participate in the regulation of airway inflammation (55). Furthermore, the inhibition of extracellular vesicles (including exosomes) was reported to mediate autophagy, which indirectly controls COPD-associated processes like airway remodeling (56). Of interest, the cellular processes related to the proteins that were positively and negatively associated with COPD were substantially different; further investigation of the pathobiological implications of these findings will be required.

Limitations of the Current Study

Although our study has provided some progress in COPD proteomics analysis, we acknowledge several important limitations. We included lung tissue samples from 150 subjects. Although this is substantially larger than previous proteomic studies of lung tissue (19–21, 26), our sample size may be inadequate for comprehensive identification of COPD protein biomarkers. Missing values were problematic, similar to other mass spectrometry proteomic studies. These missing values could relate to low abundance proteins near the lower limit of detection, variable quality of the lung tissue samples, or disease-related variability in protein levels. We used the same proteomics data set to identify potential COPD biomarkers, build machine learning models, and evaluate model performance. The availability of replication datasets will be important to identify reliable biomarkers and establish stable prediction models. The lung tissue samples were obtained during thoracic surgical procedures for clinical indications that could influence proteomic profiles. Confounding of COPD case-control status with pack-years of smoking and lung cancer in our study population is a limitation of our studies. With limited clinical phenotyping and a modest sample size, we were unable to examine COPD subtypes or COPD-related phenotypes. In addition, we acknowledge that the subset of patients with COPD undergoing thoracic surgery is likely not representative of the general COPD population. Finally, use of bulk lung tissue samples does not allow us to determine if our results were related to changes in cellular composition or to changes of protein levels within specific cell types.

In summary, despite a moderate sample size of lung tissue specimens (yet the largest cohort to be analyzed to date), we identified 25 potential protein biomarkers associated with COPD. Some of these biomarkers have been previously related to COPD pathogenesis. Several of the top proteins were highly correlated. Except for RAGE and fibrinogen, we did not find evidence that previously reported COPD plasma protein biomarkers were differentially expressed in COPD lung tissue. Future studies should involve larger sample sizes, replication populations, and assessments of identified lung tissue biomarkers in more readily available biospecimens (e.g., plasma).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The mass spectrometry proteomics data that support this study are available at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the Proteomics Identification Database (PRIDE) at EMBL-EBI with the data set identifier PXD024124 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD024124).

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Figs. S1–S12 and Supplemental Tables S1–S16: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16439025.

GRANTS

The study is supported by NIH grants, including R01 HL133135, R01 HL147148, R01 HL137927, R01 HL124233, R01 GM087221, S10 RR027584, and P01 HL114501. This study utilized biological specimens and data provided by the Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC) supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

DISCLOSURES

In the past three years, E.K.S., P.J.C., and M.H.C. have received grant support from GSK and Bayer. M.H.C. has received speaking or consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Illumina. P.J.C. has received consulting fees from GSK and Novartis. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.-H.Z., R.L.M., and E.K.S. conceived and designed research; M.R.H., K.A.S., M.K.M., and R.L.M. performed experiments; Y.-H.Z., M.R.H., P.J.C., K.A.S., M.K.M., M.H.C., J.L., R.L.M., and E.K.S. analyzed data; Y.-H.Z., M.R.H., P.J.C., K.A.S., M.K.M., M.H.C., J.L., R.M., and E.K.S. interpreted results of experiments; Y.-H.Z., J.L., R.L.M., and E.K.S. prepared figures; Y.-H.Z., M.R.H., P.J.C., K.A.S., M.K.M., M.H.C., J.L., R.L.M., and E.K.S. drafted manuscript; Y.-H.Z., M.R.H., P.J.C., K.A.S., M.K.M., M.H.C., G.J.C., R.B., J.L., R.L.M., and E.K.S. edited and revised manuscript; Y.-H.Z., M.R.H., P.J.C., K.A. S., M.K.M., M.H.C., G.J.C., R.B., J.L., R.M. and E.K.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preliminary portions of this work were presented previously: ATS (American Thoracic Society) 2021 Abstract A4342, Poster Session “TP112 - TP112 Proteomics/Genomics/Metabolomics in Lung Disease.”

Preprint is available at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.07.21255030.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, Seyednejad N, Elliott WM, Sanchez PG, Wright AC, Gefter WB, Litzky L, Coxson HO, Paré PD, Sin DD, Pierce RA, Woods JC, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam SC, Cooper JD, Hogg JC. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 365: 1567–1575, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief 293: 1–8, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan J, Pravosud V, Mannino DM, Siegel K, Choate R, Sullivan T. National and state estimates of COPD morbidity and mortality—United States, 2014-2015. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 5: 324–333, 2018. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.5.4.2018.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaldi PJ, Boueiz A, Yun J, Estepar RSJ, Ross JC, Washko G, Cho MH, Hersh CP, Kinney GL, Young KA, Regan EA, Lynch DA, Criner GJ, Dy JG, Rennard SI, Casaburi R, Make BJ, Crapo J, Silverman EK, Hokanson JE; COPDGene Investigators. Machine learning characterization of COPD subtypes: insights from the COPDGene study. Chest 157: 1147–1157, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paone G, Leone V, Conti V, De Marchis L, Ialleni E, Graziani C, Salducci M, Ramaccia M, Munafò G. Blood and sputum biomarkers in COPD and asthma: a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20: 698–708, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foong RE, Hall GL. Can we finally use spirometry in the clinical management of infants with respiratory conditions? Thorax 71: 206–207, 2016. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreeva E, Pokhaznikova M, Lebedev A, Moiseeva I, Kuznetsova O, Degryse JM. Spirometry is not enough to diagnose COPD in epidemiological studies: a follow-up study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 27: 62, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortis S, Comellas A, Make BJ, Hersh CP, Bodduluri S, Georgopoulos D, Kim V, Criner GJ, Dransfield MT, Bhatt SP. Combined forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity bronchodilator response, exacerbations, and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 16: 826–835, 2019. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201809-601OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Edwards LD, Locantore NW, Miller BE, Horstman DH, Tal-Singer R; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints study investigators. Serum surfactant protein D is steroid sensitive and associated with exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J 34: 95–102, 2009. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00156508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration; Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GDO, Collins R, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA 294: 1799–1809, 2005. [Erratum in JAMA 294: 2848, 2015]. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groenewegen KH, Postma DS, Hop WC, Wielders PL, Schlösser NJ, Wouters EF; COSMIC Study Group. Increased systemic inflammation is a risk factor for COPD exacerbations. Chest 133: 350–357, 2008. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Edwards LD, Miller BE, Coxson HO, Tal-Singer R; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigators. Evaluation of serum CC-16 as a biomarker for COPD in the ECLIPSE cohort. Thorax 63: 1058–1063, 2008. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DJ, Yerkovich ST, Towers MA, Carroll ML, Thomas R, Upham JW. Reduced soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products in COPD. Eur Respir J 37: 516–522, 2011. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00029310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurst JR, Donaldson GC, Perera WR, Wilkinson TM, Bilello JA, Hagan GW, Vessey RS, Wedzicha JA. Use of plasma biomarkers at exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174: 867–874, 2006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-506OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto-Plata V, Toso J, Lee K, Park D, Bilello J, Mullerova H, De Souza MM, Vessey R, Celli B. Profiling serum biomarkers in patients with COPD: associations with clinical parameters. Thorax 62: 595–601, 2007. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verrills NM, Irwin JA, He XY, Wood LG, Powell H, Simpson JL, McDonald VM, Sim A, Gibson PG. Identification of novel diagnostic biomarkers for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 1633–1643, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1623OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemans RL, Jacobson S, Keene J, Kechris K, Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Bowler RP. Multiple biomarkers predict disease severity, progression and mortality in COPD. Respir Res 18: 117, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0597-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keene JD, Jacobson S, Kechris K, Kinney GL, Foreman MG, Doerschuk CM, Make BJ, Curtis JL, Rennard SI, Barr RG, Bleecker ER, Kanner RE, Kleerup EC, Hansel NN, Woodruff PG, Han MK, Paine R 3rd, Martinez FJ, Bowler RP, O'Neal WK; COPDGene and SPIROMICS Investigators. Biomarkers predictive of exacerbations in the SPIROMICS and COPDGene cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195: 473–481, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee EJ, In KH, Kim JH, Lee SY, Shin C, Shim JJ, Kang KH, Yoo SH, Kim CH, Kim HK, Lee SH, Uhm CS. Proteomic analysis in lung tissue of smokers and COPD patients. Chest 135: 344–352, 2009. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornwell WD, Kim C, Lastra AC, Dass C, Bolla S, Wang H, Zhao H, Ramsey FV, Marchetti N, Rogers TJ, Criner GJ. Inflammatory signature in lung tissues in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Biomarkers 24: 232–239, 2019. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2018.1542458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandsma C-A, Guryev V, Timens W, Ciconelle A, Postma DS, Bischoff R, Johansson M, Ovchinnikova ES, Malm J, Marko-Varga G, Fehniger TE, van den Berge M, Horvatovich P. Integrated proteogenomic approach identifying a protein signature of COPD and a new splice variant of SORBS1. Thorax 75: 180–183, 2020. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrow JD, Zhou X, Lao T, Jiang Z, DeMeo DL, Cho MH, Qiu W, Cloonan S, Pinto-Plata V, Celli B, Marchetti N, Criner GJ, Bueno R, Washko GR, Glass K, Quackenbush J, Choi AM, Silverman EK, Hersh CP. Functional interactors of three genome-wide association study genes are differentially expressed in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lung tissue. Sci Rep 7: 44232, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep44232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deutsch EW, Mendoza L, Shteynberg D, Slagel J, Sun Z, Moritz RL. Trans-proteomic pipeline, a standardized data processing pipeline for large-scale reproducible proteomics informatics. Proteomics Clin Appl 9: 745–754, 2015. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philippot Q, Deslée G, Adair-Kirk TL, Woods JC, Byers D, Conradi S, Dury S, Perotin JM, Lebargy F, Cassan C, Le Naour R, Holtzman MJ, Pierce RA. Increased iron sequestration in alveolar macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 9: e96285, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Celli BR, Anderson JA, Brook R, Calverley P, Cowans NJ, Crim C, Dixon I, Kim V, Martinez FJ, Morris A, Newby DE, Yates J, Vestbo J. Serum biomarkers and outcomes in patients with moderate COPD: a substudy of the randomised SUMMIT trial. BMJ Open Respir Res 6: e000431, 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlmeier S, Nieminen P, Gao J, Kanerva T, Rönty M, Toljamo T, Bergmann U, Mazur W, Pulkkinen V. Lung tissue proteomics identifies elevated transglutaminase 2 levels in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L1155–L1165, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00021.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun P, Ye R, Wang C, Bai S, Zhao L. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with COPD frequent exacerbators. Life Sci 230: 1–9, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabryelska A, Kuna P, Antczak A, Białasiewicz P, Panek M. IL-33 mediated inflammation in chronic respiratory diseases-understanding the role of the member of IL-1 superfamily. Front Immunol 10: 692, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Z, Shu J, Zhou F, Han Y. JQ1 is a potential therapeutic option for COPD patients with agrin overexpression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L690–L694, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00500.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung JM, Mayo J, Tan W, Tammemagi CM, Liu G, Peacock S, Shepherd FA, Goffin J, Goss G, Nicholas G, Tremblay A, Johnston M, Martel S, Laberge F, Bhatia R, Roberts H, Burrowes P, Manos D, Stewart L, Seely JM, Gingras M, Pasian S, Tsao MS, Lam S, Sin DD; Pan-Canadian Early Lung Cancer Study Group. Plasma pro-surfactant protein B and lung function decline in smokers. Eur Respir J 45: 1037–1045, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00184214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimoto J, Kadara H, Garcia MM, Kabbout M, Behrens C, Liu DD, Lee JJ, Solis LM, Kim ES, Kalhor N, Moran C, Sharafkhaneh A, Lotan R, Wistuba II. G-protein coupled receptor family C, group 5, member A (GPRC5A) expression is decreased in the adjacent field and normal bronchial epithelia of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 7: 1747–1754, 2012. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826bb1ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao Q, Fujimoto J, Men T, Ye X, Deng J, Lacroix L, Clifford JL, Mao L, Van Pelt CS, Lee JJ, Lotan D, Lotan R. Identification of the retinoic acid-inducible Gprc5a as a new lung tumor suppressor gene. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 1668–1682, 2007. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo W, Hu M, Wu J, Zhou A, Liao Y, Song H, Xu D, Kuang Y, Wang T, Jing B, Li K, Ling J, Wen D, Wu W. Gprc5a depletion enhances the risk of smoking-induced lung tumorigenesis and mortality. Biomed Pharmacother 114: 108791, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastor MD, Nogal A, Molina-Pinelo S, Meléndez R, Salinas A, González De la Peña M, Martín-Juan J, Corral J, García-Carbonero R, Carnero A, Paz-Ares L. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with lung cancer and COPD. J Proteomics 89: 227–237, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JH, McDonald ML, Cho MH, Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Hunninghake GM, Marchetti N, Lynch DA, Crapo JD, Lomas DA, Coxson HO, Bakke PS, Silverman EK, Hersh CP; COPDGene and ECLIPSE Investigators. DNAH5 is associated with total lung capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 15: 97, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghio AJ, Hilborn ED, Stonehuerner JG, Dailey LA, Carter JD, Richards JH, Crissman KM, Foronjy RF, Uyeminami DL, Pinkerton KE. Particulate matter in cigarette smoke alters iron homeostasis to produce a biological effect. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 1130–1138, 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-334OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cloonan SM, Glass K, Laucho-Contreras ME, Bhashyam AR, Cervo M, Pabón MA, Konrad C, Polverino F, Siempos II, Perez E, Mizumura K, Ghosh MC, Parameswaran H, Williams NC, Rooney KT, Chen ZH, Goldklang MP, Yuan GC, Moore SC, Demeo DL, Rouault TA, D'Armiento JM, Schon EA, Manfredi G, Quackenbush J, Mahmood A, Silverman EK, Owen CA, Choi AM. Mitochondrial iron chelation ameliorates cigarette smoke–induced bronchitis and emphysema in mice. Nat Med 22: 163–174, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nm.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloonan SM, Mumby S, Adcock IM, Choi AMK, Chung KF, Quinlan GJ. The “Iron"-y of iron overload and iron deficiency in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 1103–1112, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0311PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yonchuk JG, Silverman EK, Bowler RP, Agusti A, Lomas DA, Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Mayer RJ. Circulating soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) as a biomarker of emphysema and the RAGE axis in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192: 785–792, 2015. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0137PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng DT, Kim DK, Cockayne DA, Belousov A, Bitter H, Cho MH, Duvoix A, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, Miller BE, Reynaert N, Tal-Singer R, Wouters EF, Agustí A, Fabbri LM, Rames A, Visvanathan S, Rennard SI, Jones P, Parmar H, MacNee W, Wolff G, Silverman EK, Mayer RJ, Pillai SG; TESRA and ECLIPSE Investigators. Systemic soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts is a biomarker of emphysema and associated with AGER genetic variants in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 948–957, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0247OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockayne DA, Cheng DT, Waschki B, Sridhar S, Ravindran P, Hilton H, Kourteva G, Bitter H, Pillai SG, Visvanathan S, Müller KC, Holz O, Magnussen H, Watz H, Fine JS. Systemic biomarkers of neutrophilic inflammation, tissue injury and repair in COPD patients with differing levels of disease severity. PLoS One 7: e38629, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, Qu W, Taguchi A, Lu Y, Avila C, Kambham N, Bierhaus A, Nawroth P, Neurath MF, Slattery T, Beach D, McClary J, Nagashima M, Morser J, Stern D, Schmidt AM. RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 97: 889–901, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zandvoort A, van der Geld YM, Jonker MR, Noordhoek JA, Vos JT, Wesseling J, Kauffman HF, Timens W, Postma DS. High ICAM-1 gene expression in pulmonary fibroblasts of COPD patients: a reflection of an enhanced immunological function. Eur Respir J 28: 113–122, 2006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00116205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kusebauch U, Campbell DS, Deutsch EW, Chu CS, Spicer DA, Brusniak MY, Slagel J, Sun Z, Stevens J, Grimes B, Shteynberg D, Hoopmann MR, Blattmann P, Ratushny AV, Rinner O, Picotti P, Carapito C, Huang CY, Kapousouz M, Lam H, Tran T, Demir E, Aitchison JD, Sander C, Hood L, Aebersold R, Moritz RL. Human SRMAtlas: a resource of targeted assays to quantify the complete human proteome. Cell 166: 766–778, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sukkar MB, Wood LG, Tooze M, Simpson JL, McDonald V, Gibson P, Wark PAB. Soluble RAGE is deficient in neutrophilic asthma and COPD. Eur Respir J 39: 721–729, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00022011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miniati M, Monti S, Basta G, Cocci F, Fornai E, Bottai M. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in COPD: relationship with emphysema and chronic cor pulmonale: a case-control study. Respir Res 12: 37, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Izmirlian G. Application of the random forest classification algorithm to a SELDI‐TOF proteomics study in the setting of a cancer prevention trial. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1020: 154–174, 2004. doi: 10.1196/annals.1310.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swanson RK, Xu R, Nettleton D, Glatz CE. Proteomics-based, multivariate random forest method for prediction of protein separation behavior during cation-exchange chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1249: 103–114, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Gene Ontology Consortium . The gene ontology resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res 47: D330–D338, 2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meigs TE, Fedor-Chaiken M, Kaplan DD, Brackenbury R, Casey PJ. Gα12 and Gα13 negatively regulate the adhesive functions of cadherin. J Biol Chem 277: 24594–24600, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eapen MS, Myers S, Lu W, Tanghe C, Sharma P, Sohal SS. sE-cadherin and sVE-cadherin indicate active epithelial/endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT and EndoMT) in smokers and COPD: implications for new biomarkers and therapeutics. Biomarkers 23: 709–711, 2018. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2018.1479772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pniewska E, Pawliczak R. The involvement of phospholipases A2 in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mediators Inflamm 2013: 793505, 2013, doi: 10.1155/2013/793505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boukhenouna S, Wilson MA, Bahmed K, Kosmider B. Reactive oxygen species in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018: 5730395, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/5730395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meliton AY, Muñoz NM, Lambertino A, Boetticher E, Learoyd J, Zhu X, Leff AR. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition of β2-integrin adhesion caused by leukotriene B4 and TNF-α in human neutrophils. Eur Respir J 28: 920–928, 2006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00028406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujita Y, Kosaka N, Araya J, Kuwano K, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles in lung microenvironment and pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med 21: 533–542, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujita Y, Araya J, Ito S, Kobayashi K, Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Kadota T, Hara H, Kuwano K, Ochiya T. Suppression of autophagy by extracellular vesicles promotes myofibroblast differentiation in COPD pathogenesis. J Extracell Vesicles 4: 28388, 2015. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.28388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data that support this study are available at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the Proteomics Identification Database (PRIDE) at EMBL-EBI with the data set identifier PXD024124 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD024124).