Abstract

The mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) performs the first and last step in oxidative phosphorylation by exchanging ADP and ATP across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Its optimal function has been shown to be dependent on cardiolipins (CLs), unique phospholipids located almost exclusively in the mitochondrial membrane. In addition, AAC exhibits an enthralling threefold pseudosymmetry, a unique feature of members of the SLC25 family. Recently, its conformation poised for binding of ATP was solved by x-ray crystallography referred to as the matrix state. Binding of the substrate leads to conformational changes that export of ATP to the mitochondrial intermembrane space. In this contribution, we investigate the influence of CLs on the structure, substrate-binding properties, and structural symmetry of the matrix state, employing microsecond-scale molecular dynamics simulations. Our findings demonstrate that CLs play a minor stabilizing role on the AAC structure. The interdomain salt bridges and hydrogen bonds forming the cytoplasmic network and tyrosine braces, which ensure the integrity of the global AAC scaffold, highly benefit from the presence of CLs. Under these conditions, the carrier is found to be organized in a more compact structure in its interior, as revealed by analyses of the electrostatic potential, measure of the AAC cavity aperture, and the substrate-binding assays. Introducing a convenient structure-based symmetry metric, we quantified the structural threefold pseudosymmetry of AAC, not only for the crystallographic structure, but also for conformational states of the carrier explored in the molecular dynamics simulations. Our results suggest that CLs moderately contribute to preserve the pseudosymmetric structure of AAC.

Significance

At both ends of oxidative phosphorylation, the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) switches between two conformational states, the cytoplasmic and matrix states, to import and export nucleotides across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Its optimal function depends on cardiolipins, which stabilize the protein as it undergoes conformational transitions. Here, we assess how these lipids, ubiquitous to the mitochondrial membrane, modulate the structural stability, symmetry, and ATP-binding properties of the carrier in its matrix state, and find that by strengthening interdomain noncovalent interactions, they promote more compact conformations of the protein. In turn, the cardiolipin-induced structural rigidity of ADP/ATP carrier regulates the number of conformations of ATP conducive for binding to the carrier. We also show that cardiolipins mildly preserve the threefold pseudosymmetry of the carrier.

Introduction

The mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) is an integral membrane protein responsible for the exchange of ADP and ATP across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) (1) and it is a member of the SLC25 mitochondrial carrier family (2,3). In eukaryotic cells, AAC is the most abundant protein in the IMM, and provides the first and the last step of oxidative phosphorylation by importing ADP from the mitochondrion and exporting the synthesized ATP out to the intermembrane space, which is confluent with the cytosol via channels (4,5). To fulfill its task, the AAC switches between two distinct conformational states. The first state, known as the cytoplasmic-state (c-state), binds ADP in a conformation open toward the intermembrane space. Conversely, the so-called matrix state (m-state) binds ATP in a conformation that is open toward the matrix. To date, two classes of inhibitors have been identified and broadly employed in biochemical studies and structural characterization of the transporter. The first class of inhibitors, which includes atractyloside and carboxyatractyloside (CATR), locks the carrier in the c-state. The second class of inhibitors, which includes bongkrekic (BKA) and isobongkrekic acid, lock the carrier in the m-state (1).

In 2003 (6), the structure of bovine AAC, trapped in its c-state by CATR, was solved by x-ray crystallography. The structure of the m-state had to wait, however, until 2019 to be unveiled for the fungal AAC in complex with BKA, also using x-ray crystallography (7). In either conformational state, AAC consists of a transmembrane (TM) domain composed of six α-helices, referred to as H1 through H6, connected by loops with short α-helical stretches, named h12, h34, and h56, which lie parallel to the membrane surface. Each odd-numbered helix, namely H1, H3, and H5, has a distinctive kink induced by a proline or serine residue (8). This pattern is found in a conserved motif, (PS)x(DE)xx(KR), characteristic of mitochondrial carriers (4). Furthermore, a conserved sequence, (YF)(DE)xx(KR), has been identified on the even-numbered helices, namely H2, H4, and H6 (9). Resolving the controversy that pervaded about the oligomeric state of AAC, the carrier fulfills its function in a monomeric form (10) based on a large number of independent observations (7,11). Availability of high-resolution three-dimensional structures for both the c- and m-states of AAC has paved the way for new research avenues aimed at elucidating the exchange mechanism of adenine nucleotides by the carrier. Yet, a comprehensive understanding of the transport mechanism of AAC by structural techniques, such as NMR or cryogenic electron microscopy, is difficult to achieve because the carrier is highly dynamic and unstable in detergent solutions (12). In this sense, computational techniques, such as molecular dynamics (MD), represent an attractive—and often unique—alternative to scrutinize complex biological objects embedded in a lipid environment, like the AAC. In fact, a recent study combining homology modeling with biased MD simulations was performed to study the m-state of AAC when its crystallographic structure was not available (13).

AAC possesses two outstanding features amid other transport proteins, which are critical to understand its mechanism. First, optimal function of AAC has been shown to occur in the presence of cardiolipins (CLs) (14,15), a signature phospholipid of energy-transducing membranes, like the IMM. CLs play a central role in several metabolism processes, including energy production, and it represents ∼15–20% of the total mitochondrial phospholipids (16,17). In fact, the crystallographic structures of AAC in both conformational states have been obtained in complex with several CLs, which is an indicator of the strong interactions of this particular phospholipid with the carrier (6, 7, 8). Biophysical investigations aimed at clarifying the role of CLs on the structure and function of the AAC are, therefore, of topical interest. Second, AAC presents a high degree of threefold symmetry in structure (6,18) and sequence (9), although it transports substrates that are structurally and chemically asymmetric (9). Critical residues for the transport mechanism are, indeed, likely symmetrically distributed, in contrast with residues involved in substrate binding (9). It is, thus, of paramount importance to assess the degree of symmetry in AAC to elucidate its substrate transport mechanism.

This manuscript sets out to critically examine the influence of CLs on the conformational equilibrium and the substrate-binding ability of the m-state of AAC. Toward this end, microsecond-scale MD simulations of apo-AAC in a lipid environment have been carried out and analyzed using a variety of observables. A new measure of the local threefold pseudosymmetry in AAC has been introduced to assess the impact of CLs on the geometric properties of the carrier. In addition, ATP-binding events were explored by means of unbiased MD simulations to characterize metastable states of substrate binding in AAC.

Materials and methods

Construction of the computational assay

The initial crystallographic structure of the m-state Thermothelomyces thermophila-AAC (7) was immersed in an orthorhombic cell containing a fully thermalized 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) lipid bilayer in equilibrium with a water lamella, 22 Å thick above and below it, representing an initial dimension of 90 × 90 × 98 Å3. To ensure electric neutrality, Cl– and K+ counterions were added to reach a salt concentration of 150 mM.

Computational details

All MD simulations were carried out with NAMD 2.13 (19), imposing three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions. The all-atom CHARMM36 force field for biomolecules was used to compute the potential energy of the system (20,21). Long-range electrostatic interactions were handled with the particle-mesh Ewald algorithm (22), whereas short-range electrostatic and van der Waals interactions were evaluated within a 12-Å cutoff sphere. To maximize sampling efficiency, a 4-fs time step was used to propagate motion. This approach is facilitated by combining the Shake/Rattle/Settle algorithms, which constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms to their equilibrium lengths, with a hydrogen-mass repartitioning scheme. All MD simulations were carried out in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, using Langevin dynamics and the Langevin piston algorithm (23) to maintain the temperature and the pressure at 298 K and 1 atm, respectively. A thermalization stage of 50 ns prefaced the unbiased MD simulations. Finally, the MD analyses and figures were prepared using the VMD visualization program (24).

Results and discussion

Structural features of fungal apo-AAC

A conformational and structural analysis of the m-state of fungal AAC embedded in a lipid environment (Fig. 1 A), in the presence and absence of CLs, has been carried out by all-atom MD simulations. In contrast with other phospholipids, CLs are found almost exclusively in the IMM, where they play an important role in the dynamics and morphological stability of the mitochondrial membrane (16). Additionally, CLs interact with and support the proper function of several IMM proteins, such as the enzyme complexes of the respiratory chain and AAC.

Figure 1.

AAC in the m-state immersed in a fully hydrated POPC bilayer. The protein is shown in a cartoon representation, with α-helices highlighted in purple. Lipids units are depicted in brown, with their phosphate and choline groups shown as orange and green spheres, respectively. Potassium and chloride counterions are depicted in yellow and silver, respectively (A). A continuous and semitransparent cyan representation is used for water. Time evolution of the RMSD over the backbone atoms of the α-helices of apo-AAC in the absence and in the presence of CLs with respect to the crystallographic geometry (PDB: 6GCI chain A) (B). RMSF over Cα-atoms of apo-AAC with and without CLs (C). The experimental RMSF values were obtained from the crystallographic structure (PDB: 6GCI chain A). Three-dimensional electrostatic isopotential map of apo-AAC in the m-state in the absence (a) and in the presence (b) of CLs (D). Here, we show a cross-section of the three-dimensional map along the longitudinal axis of the funnel. To see this figure in color, go online.

To investigate the role of CLs on the function and stability of AAC at the atomic level, a 1-μs-long, unbiased MD simulation was triplicated, i.e., 3 μs in total, for the m-state of AAC in the presence and in the absence of CLs. The starting coordinates for both simulations were obtained from the crystallographic structure of Thermothelomyces thermophila (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 6GCI chain A) (7). In addition, the initial position of the three CLs was defined based on the specific binding sites reported previously in the literature (7,8). The structural analysis of the first replica of the 1-μs MD trajectories for both systems is reported in Fig. 1, B–D. Overall, the time series of the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) over backbone-atom positions for the nine helices of AAC (Fig. 1 B) shows remarkable protein stability in both MD simulations, with an average fluctuation of ∼3 Å. The MD trajectories reveal a slightly lower RMSD fluctuation of the AAC structure in the presence of CLs, which indicates a perceptible stabilizing effect due to the CLs. Conversely, the stabilizing effect of the CLs on the AAC structure, measured by the RMSD time series of the two additional replicas of unbiased MD simulations, is only marginal, as highlighted in Fig. S1. Nevertheless, a stabilizing effect was observed by Škulj et al., compared with simulations of the carrier bereft of CLs, albeit with an RMSD nearly twice as large (25). The root mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) for the Cα-atom positions for each MD simulation are depicted in Fig. 1 C. These theoretical profiles are compared with their experimental counterpart obtained from the crystallographic B-factors, where the largest fluctuations are found in the loops, and the lowest fluctuations, in the α-helix-rich regions, thus, offering a good qualitative agreement between theory and experiment. The time series for the secondary structure, depicted in Fig. S2, was obtained for both MD simulations as a third structural metric of stability. Clearly, the secondary structure of AAC in both conditions is fully preserved during the two 1-μs simulations, indicative of no evidence of helix unfolding, or even fraying. Next, the electrostatic properties of the m-state of apo-AAC, in the presence and absence of CLs, were analyzed by computing the average isopotential contour map over the course of the MD simulations (Fig. 1 Da and b). First, for both conformations, an electropositive region located at the bottom of the central cavity is consistent with the characteristic electrostatic funnel shared by the bovine AAC in the c-state. A patch of basic residues borne by α-helices H1, H3, h12, and h34 (R54, K51, R71, R145, K153, K156, and R171) form the entry of the funnel, and the cavity allows the passage of negatively charged nucleotides, like ATP. A similar electrostatic potential analysis of the cytoplasmic open state (c-state) of bovine AAC was reported in earlier studies (26,27). These theoretical investigations demonstrated that an electrostatic funnel, open toward the intermembrane space in the c-state, represents a selective passageway to guide the entry of any negatively charged species into the carrier. Just like the m-state, a similar region of positively charged residues, formed by residues K91, K95, K198, and R187, and borne by α-helices H2 and H4, can easily interact with the substrate as it diffuses within the c-state of bovine AAC. Finally, to complement the analysis of the electrostatic potential of the AAC funnel, the dimension of the matrix-oriented cavity of the protein—i.e., the AAC mouth, in the presence and in the absence of CLs, was determined from the unbiased MD simulations. Considering the pyramid shape of the AAC cavity, the dimension of the AAC mouth was approximated as the perimeter of the triangle base formed by the Cα’s atoms of residues 79, 183, and 277. These residues line the outermost surface of the mouth of the carrier, as they are found at the end of helices H2, H4, and H6, respectively. The time series of the perimeter of the mouth generated from the unbiased (first replica) MD simulations of the m-state of apo-AAC, with and without CLs, are reported in Fig. S3 A. On average, conformations of the AAC featuring a mouth more widely open are found in the absence of CLs, indicative that interactions of the latter with the mitochondrial carrier provide additional stabilization, and, in turn, regulate substrate transport. A similar behavior can be observed from the analysis of the two additional MD simulations, as shown in Fig. S3 B.

Interactions between apo-AAC and CLs

The crystallographic structure of Thermothelomyces thermophila-AAC in the m-state was solved in complex with the three CLs located between the even-numbered α-helices and the α-helical stretches parallel to the membrane (Fig. S4). The first CL, marked as CL1, is found in the proximity of H4 and h56. Likewise, the second CL, referred to as CL2, is located between H2 and h34. Finally, the third CL is found in contact with H6 and h12. In all three cases, the headgroup of the CLs was completely resolved, but the acyl chains were only partially so, and for only one of them, and utterly absent for the remaining two. This crystallographic evidence can be explained by the strong polar interactions, namely hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, formed between the CL headgroups and the carrier, in stark contrast with the variable and weaker van der Waals contacts between the highly flexible acyl chains and the membrane protein. Interestingly enough, the unbiased MD simulations of the apo-AAC with CLs confirm the strong noncovalent interactions between the CL headgroups of CLs and the carrier, supported by the absence of unbinding event during the entire simulations, in all three replicas. The main hydrogen bonds and salt bridges formed between the CLs and AAC are presented for the first MD replica in Fig. S6. In particular, the phosphate groups of CL1 mainly interacts with the backbone atoms of G185 and S261, as well as with the side chains of R184, S260, and S261. The time series for these polar interactions are depicted in Fig. S6 A. Furthermore, the phosphate group of CL2 interacts constantly with the backbone of G81 and T83, as well as with the side chains of R80 and T83 (see Fig. S6 B). Last, the interaction pattern for the headgroup of CL3 shows polar contacts with the backbone of N284 and I285, as well as with the side chain of K40 (see Fig. S6 C). Among the three CLs, CL3 was the most mobile one, albeit it remained bound to the protein in all three MD replicas. A similar behavior was observed with the other two MD replicas, as shown in Fig. S7.

Time evolution of the cytoplasmic network

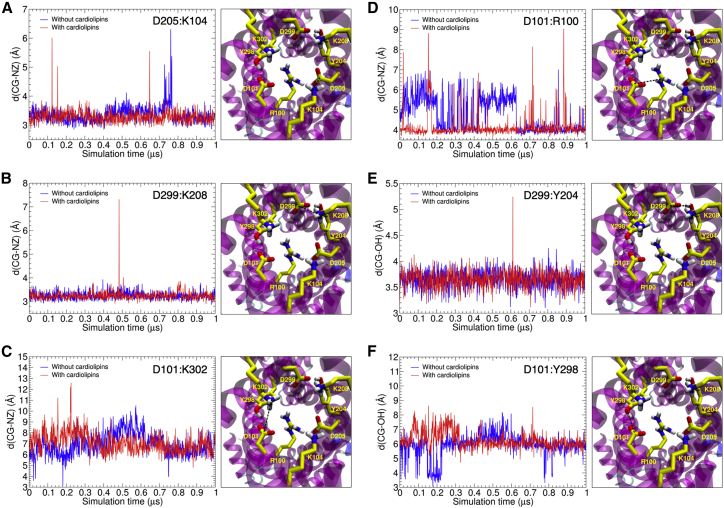

The two well-defined conformations of AAC, namely, the c- and m-states, are supported by two networks of salt bridges that interconnect the interdomain α-helices on either side of the carrier in a state-dependent way, thereby contributing to the global protein stability. Disruption of these two salt bridges is considered to be a starting point for the conformational transition between the two end states (9). Robustness of the noncovalent interactions at play is, therefore, critical to provide long-lived biological function of both m- and c-states, as it waits for the substrate. In the case of the m-state, the charged residues forming the cytoplasmic salt-bridge network, which link the even-numbered TM helices, are responsible for keeping the gate toward intermembrane space closed. The cytoplasmic network in AAC is composed of salt bridges network formed by 1) K102 on H2 and D205 on H4, 2) K208 on H4 and D299 on H6, and 3) K302 on H6 and D101 on H2. A Q302K mutation was introduced to stabilize the cytoplasmic network and thus the m-state (28), which will be discussed later. The time evolution of these three salt bridges is depicted in Fig. 2, A–D. Interestingly enough, salt bridges K104/D205 and K208/D299 were fully preserved during the entire MD simulations, both in the presence and in the absence of CLs (see Fig. 2, A and B). In stark contrast, the third salt bridge, K302/D101, was disrupted during both MD simulations, which indicates that the stability of this salt bridge is not directly correlated with the presence or absence of CLs (see Fig. 2 C). This might actually reflect the situation in wild-type AAC because Q302 might be able to interact only weakly or transiently with D101, as it has no charge and is shorter than the mutated lysine residue.

Figure 2.

Time evolution of four salt bridges: D205/K104 (A), D299/K208 (B), D101/K302 (C), D101/R100 (D) and two hydrogen bonds: D299/Y204 (E) and D101/Y298 (F) of apo-AAC in the m-state in absence and presence of CLs. To see this figure in color, go online.

Furthermore, the m-state of AAC possesses a set of highly conserved tyrosine residues, providing an additional interdomain stabilization through the formation of hydrogen bonds that “brace” the cytoplasmic salt-bridge network. In the tyrosine brace, Y204 establishes a hydrogen bond with D299, and Y298 with D101, thereby reinforcing salt bridges K208/D299 and D101/K302, respectively. The time evolution for the two hydrogen bonds in the tyrosine brace is shown in Fig. 2, E and F. Irrespective of the presence of CLs, the hydrogen bond formed between Y204 and D299 was stable throughout both MD simulations. In contrast, residues Y298 and D101 were found ∼6 Å from each other, which is incompatible with a steady hydrogen bond formation. Surprisingly enough, however, occasional hydrogen bond formations were observed in the absence of CLs on the timescale of the simulation. This effect might be due to movement of domain 1, which is bound less well in the BKA-inhibited state. AAC are unique in that they have an arginine replacement of one of the three tyrosine braces, i.e., R100, but the replacement fulfills a similar role. The intradomain salt bridge D101/R100 remained intact in the presence of CLs, but only transiently formed in their absence (see Fig. 2 D). Put together, interdomain salt bridges D205/K104, D299/K208, and hydrogen bond D299/Y204 constitute strong noncovalent interactions, which appear sufficient to maintain the carrier hermetically close on the cytoplasmic side, and preserve the overall architecture of the m-state. These interactions and R100/D205 were mildly stabilized in the presence of CLs.

Substrate-binding events from multiple MD simulations

To gain further insight into the binding mechanism of ATP to the carrier, a set of spontaneous substrate-binding experiments was conducted. Toward this end, one ATP was placed near the mouth of a well-equilibrated conformation of apo-AAC in its m-state and 20 unbiased MD replicas, 500-ns long, each using a different seed to generate the initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, were run independently. These substrate-binding experiments were performed in the presence and in the absence of CLs, corresponding to an aggregate 20 μs of MD sampling, which was subsequently utilized for geometric analyses.

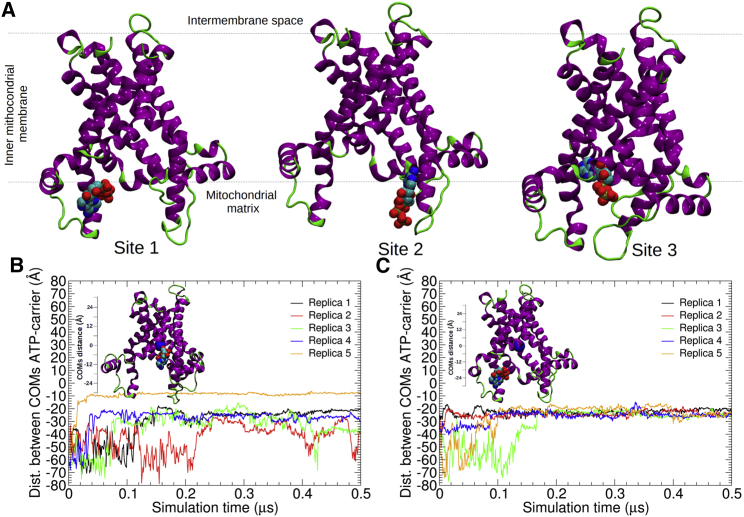

First, a set of binding sites for the substrate, depicted in Fig. 3 A, was identified by exploring each MD replica. These binding sites are the loci of metastable, short-lived binding modes of ATP in the vicinity of the mouth of the carrier. We have identified three of these binding sites for ATP in the m-state of AAC. Site 1 lies at the mouth of the carrier, and is formed by helices H2 and h12, whereby the protein is in a fully open, apo-like, conformation. Site 2 lies at the rim of the mouth, around helices H3 and h34, and, similar to site 1, the carrier is in a fully open conformation. In contrast, site 3 lies in the vicinity of the geometric center of the carrier, which adopts a conformation with a narrower mouth. In this study, site 3 is considered the most likely substrate-binding site (Ruprecht et al. in (7)) because it contains key residues that interact with both nucleotides, ATP and ADP, as well as the inhibitors CATR and BKA (see analysis hereafter).

Figure 3.

Identification of three binding sites in the m-state of AAC from MD simulations with and without CLs (A). Time evolution of the distance separating the center of mass of the substrate from that of the carrier (blue sphere) from unbiased ATP-binding assays in the absence (B) and in the presence (A and C) of CLs. For clarity, only the first five MD replicas are depicted. To see this figure in color, go online.

Second, we characterized quantitatively the substrate-binding events by measuring the distance between the center of mass of the carrier and ATP in each MD replica. The time series of this geometric variable for the 40 MD replicas, in the presence and in the absence of CLs, are shown in Fig. 3, B and C and Figs. S8–S13. In the absence of CLs (see Fig. 3 B; Figs. S8–S10), a total of four out of 20 replicas where identified, where the substrate binds to site 3, close to the center of the carrier. Not too surprisingly, no spontaneous unbinding event of ATP from site 3 was observed over the timescale of the simulations, indicative of strong substrate-carrier interactions. In most replicas, the substrate was found at site 1, and to a lesser extent at site 2, and unbinding events from both sites were observed, indicating that they are transient binding events (26,27,29). The area highly exposed to the solvent and the weak substrate-carrier interactions at sites 1 and 2 rationalize the binding and unbinding events monitored over the timescale of the simulations. In the presence of CLs (see Fig. 3 C; Figs. S11–S13), a total of only 2 out of 20 replicas correspond to a binding of the substrate in the proximity of the protein geometric center. Evidently, the CCL-AAC interactions generate conformations of the carrier that are less accessible to the substrate, in line with our analysis of the electrostatic properties of the carrier and of its interdomain noncovalent interactions.

Third, the last configuration of those MD replicas, whereby binding occurred at site 3, in the presence and in the absence of CLs, were extended to 1 μs. The aim for this assay was to examine the possible spatial rearrangement of ATP and its interaction with critical residues lining the binding site. To characterize the conformations adopted by the substrate in the AAC binding site, with and without CLs, a principal component analysis over Cartesian coordinates was performed on the ATP-heavy atoms. The principal component analysis plots alongside the binding poses of ATP from the 1-μs MD simulation in the absence and in the presence of CLs are gathered in Fig. S14, A and B. In the absence of CLs, the starting position of ATP in the binding site features the adenine moiety in contact with R88, whereas the phosphate groups interact with R88 and R287 by means of salt bridges. Then, around 0.6–0.8 μs of the simulation, the ATP reorients within the binding site, with the phosphate moieties still interacting with R88 and R287, whereas the adenine moiety is located in a hydrophobic subsite surrounded by G192, I193, and Y196, and forms a hydrogen bond with S238 (see Fig. S14 A). The binding pose for ATP in the presence of CLs is very different from that in the absence of CLs. ATP is found in a conformation, whereby the phosphate moieties engage in salt bridges with residues R197, R287, and R88, but the adenine moiety is oriented in such a way that it forms a cation-π-stacking interaction with residue R88, and a hydrogen bond with residue K30 (see Fig. S14 B). In the presence of CLs, the ATP preserves its orientation within the binding site over the entire MD simulation, whereas the adenine moiety remains in contact with residue R88. The presence of CLs rigidifies the interior of the membrane protein, thereby hindering substrate tumbling and isomerization toward the required orientation and extended conformation at the binding site.

Structure-based symmetry analysis

One particular feature found in AAC is its threefold pseudosymmetry, conserved across different species, as shown by the x-ray structures of the bovine (6) and the fungal (7) carriers. In fact, it is believed that the transport mechanism is likely to be symmetrical because of the salt-bridge networks and other symmetrical features (9). Loss of structural symmetry might be an indication of a nonfunctional protein (9). In this sense, an additional role attributed to CLs would be to preserve the symmetric spatial rearrangement of the α-helices in AAC, either in its m- or c-state, to guarantee protein functionality. With this hypothesis in mind, a metric, denoted Ψ, was proposed to assess the level of deviation from an ideal threefold symmetry, and is defined as,

| (1) |

where are the angles (in degrees) formed by three coplanar atoms, namely Cα-atoms, from similarity-related residues borne by helices H2, H4, and H6, thus, forming a triangle in the (x, y)-plane, parallel to the surface of the membrane (see Fig. 4 Aa and b). is expected to be nearly zero for a pure C3 symmetrical residue triad, and greater than zero for a distorted, i.e., nonequilateral, triangular set of residues. Higher values of are indicative of a high deviation from a threefold symmetry for the residue triad. Accordingly, Ψ quantifies the average deviation from a perfect threefold symmetry of a given triangular arrangement of symmetry-related residues in AAC. It is noteworthy that (9) introduced a sequence-based symmetric score to measure conserved threefold symmetry for subfamilies of mitochondrial transports. On the other hand, the symmetry metric proposed here is obtained from atomic coordinates of AAC. The symmetry analysis using a metric based on a three-dimensional structure—as opposed to just an amino-acid sequence—offers certain advantages, as it allows analyzing at an atomistic level the source and location of symmetry disruptions in the protein of interest.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of a C3-symmetric object for the definition of the symmetry score Ψ (A). Residues pertaining to H2, H4, and H6 of the crystallographic structure of AAC in its m-state (a) are highlighted using a color-gradient scheme according to their Ψ-value. An ideal C3 system (b) is represented as an equilateral triangle in which the corners correspond to the Cα-atoms of the residues borne by TM helices H2, H5, and H6. Symmetry analysis based on the Ψ score (B). Residues pertaining to H2, H4, and H6 of the crystallographic structure of AAC in its m-state (a) are highlighted using a color-gradient scheme according to their Ψ-value. Ψ-Values for the different triads of residues in H2, H5, and H6 for the crystallographic structure of AAC in its m-state (b). Time evolution of the Ψ-symmetry score analysis for the triads of residues in H2, H5, and H6 of AAC in its m-state, in the absence (C) and in the presence (D) of CLs. To see this figure in color, go online.

We have analyzed the variations in the threefold pseudosymmetry of the crystallographic structure of AAC in its m-state. Fig. 4 Bb shows the Ψ-values computed for 20 residue triads in the membrane protein, going from the cytoplasmic to the matrix side on the even-numbered helices. A color scheme has been introduced to highlight the residues according to their degree of symmetry quantified by Ψ (Fig. 4, Aa and Ba). Interestingly enough, we observed a high-symmetry conservation at the level of the cytoplasmic salt-bridge network, which progressively deteriorates toward the matrix network of the salt bridges, as observed previously (7).

Extending the symmetry analysis to conformations of AAC sampled by MD simulations in the presence and absence of CLs, we computed the time series of Ψ for the 20 residue triads based on the 1-μs MD simulations (See Fig. 4, C and D). A positive, albeit moderate influence of the CLs can be observed on the AAC symmetry profile. In particular, our MD simulations with and without CLs indicate a significant symmetry deviation in the first four groups of residue triads belonging to the cytoplasmic network. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic gate region shows a high conservation of its symmetry, irrespective of the presence of CLs. Last, a closer view at the time evolution of Ψ for those residues belonging to the binding site, as depicted in Fig. S15, A and B, reveals a slightly higher degree of symmetry in the presence of CLs, compared to that in their absence. This trend is also observed for the additional two MD replicas in the region of the binding site (see Fig. S15, C–F), where a higher symmetry is also found in the presence of CLs.

Conclusions

In this contribution, we have thoroughly investigated the impact of CLs on the conformational equilibrium, the topology, and the substrate-binding properties of AAC in its m-state by means of microsecond-timescale MD simulations. Overall, we confirm that the global stability of AAC is not compromised by the absence of CLs. Most of the internal noncovalent interactions comprising the cytoplasmic salt-bridge network and the tyrosine brace, critical for the global stability of the m-state of the mitochondrial carrier, remained robust during the simulations, irrespective of the presence of CLs. Yet, it is worth mentioning that CLs play a significant role on the rigidity of the protein scaffold, as well as on the constriction or narrowing of the cavity opening. The funnel-like gateway for ATP in the m-state of AAC is tighter in the presence of CLs, as demonstrated by the three-dimensional map of its electrostatic potential. This constriction is also supported by a reduced number of substrate-binding events when CLs were present because the freedom of movements is more restricted for the substrate. Three metastable binding sites were identified in the ATP-binding assays described herein. Two of these binding sites lie on the inner surface of the cavity mouth, whereas the third one is located deep inside the carrier just above, the level of the matrix salt-bridge network. Diffusion of the nucleotide to this third binding site is hindered by a tighter cavity induced by the presence of CLs. Binding to this site was only observed in the absence of CLs, suggesting that the recognition and association process is by and large slower in the m-state, relative to the c-state of bovine AAC (26,29). In this theoretical investigation, we also addressed how CLs impact the threefold pseudosymmetry of AAC, an important feature connected with the function of the transporter. Toward this end, we designed a symmetry score based on the three-dimensional information of the carrier. This metric allowed the average deviation from an ideal threefold symmetry of helices H2, H4, and H6 to be assessed for the conformations of the mitochondrial carrier sampled in MD simulations. Our analysis reveals that the threefold pseudosymmetry of m-state in AAC remains only moderately affected by the absence of CLs. Based on the atomistic insights into the influence of CLs on the structural, dynamical, and substrate-binding properties of the AAC in its m-state reported herein, our findings support the experimental evidence of the fundamental role of CLs in regulating ATP/ADP transport (7). They also lend credence to the view that CLs act as a tether, preventing the carrier from opening too much, in a disorderly fashion. This tighter structure may restrict the number of conformations by which ATP can bind to the binding site, which in turn may be of importance for the conformational transition between the two end states, required for nucleotide exchange across the mitochondrial membrane.

Author contributions

J.J.M.-A. and C.C. carried out all simulations. J.J.M.-A., C.C., F.D., E.R.S.K., and J.J.R. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the European Regional Development Fund and to the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ProteaseInAction) for their support of this research.

Editor: Philip Biggin.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.11.002.

Contributor Information

François Dehez, Email: francois.dehez@univ-lorraine.fr.

Christophe Chipot, Email: chipot@illinois.edu.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Ruprecht J.J., Kunji E.R. Structural changes in the transport cycle of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019;57:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruprecht J.J., Kunji E.R.S. The SLC25 mitochondrial carrier family: structure and mechanism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020;45:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunji E.R.S., King M.S., et al. Thangaratnarajah C. The SLC25 carrier family: important transport proteins in mitochondrial physiology and pathology. Physiology (Bethesda) 2020;35:302–327. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00009.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingenberg M. The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1978–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunji E.R.S., Aleksandrova A., et al. Ruprecht J.J. The transport mechanism of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863:2379–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pebay-Peyroula E., Dahout-Gonzalez C., et al. Brandolin G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature. 2003;426:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruprecht J.J., King M.S., et al. Kunji E.R.S. The molecular mechanism of transport by the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Cell. 2019;176:435–447.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruprecht J.J., Hellawell A.M., et al. Kunji E.R.S. Structures of yeast mitochondrial ADP/ATP carriers support a domain-based alternating-access transport mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E426–E434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320692111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson A.J., Overy C., Kunji E.R.S. The mechanism of transport by mitochondrial carriers based on analysis of symmetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17766–17771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809580105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunji E.R.S., Ruprecht J.J. The mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier exists and functions as a monomer. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020;48:1419–1432. doi: 10.1042/BST20190933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunji E.R.S., Crichton P.G. Mitochondrial carriers function as monomers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehez F., Schanda P., et al. Chipot C. Mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in dodecylphosphocholine binds cardiolipins with non-native affinity. Biophys. J. 2017;113:2311–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K., Hayashi S. Atomistic modeling of alternating access of a mitochondrial ADP/ATP membrane transporter with molecular simulations. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klingenberg M. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial carriers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:2048–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paradies G., Paradies V., et al. Petrosillo G. Functional role of cardiolipin in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1837:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paradies G., Paradies V., et al. Petrosillo G. Role of cardiolipin in mitochondrial function and dynamics in health and disease: molecular and pharmacological aspects. Cells. 2019;8:728. doi: 10.3390/cells8070728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senoo N., Kandasamy S., et al. Claypool S.M. Cardiolipin, conformation, and respiratory complex-dependent oligomerization of the major mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in yeast. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabb0780. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunji E.R.S., Harding M. Projection structure of the atractyloside-inhibited mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36985–36988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips J.C., Braun R., et al. Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., et al. Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klauda J.B., Venable R.M., et al. Pastor R.W. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feller S.E., Zhang Y., et al. Brooks B.R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38, 27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Škulj S., Brkljača Z., Vazdar M. Molecular dynamics simulations of the elusive matrix-open state of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Isr. J. Chem. 2020;60:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dehez F., Pebay-Peyroula E., Chipot C. Binding of ADP in the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier is driven by an electrostatic funnel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12725–12733. doi: 10.1021/ja8033087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., Tajkhorshid E. Electrostatic funneling of substrate in mitochondrial inner membrane carriers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9598–9603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801786105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King M.S., Kerr M., et al. Kunji E.R.S. Formation of a cytoplasmic salt bridge network in the matrix state is a fundamental step in the transport mechanism of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krammer E.-M., Ravaud S., et al. Chipot C. High-chloride concentrations abolish the binding of adenine nucleotides in the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier family. Biophys. J. 2009;97:L25–L27. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.