Abstract

Defense mechanisms are unconscious and automatic psychological processes that serve to protect the individual from painful emotions and thoughts. There is ample evidence from the adult psychotherapy and mental health literature suggesting the salience of defenses in the maintenance and amelioration of psychological distress. Although several tools for the assessment of children’s defenses exist, most rely on projective and self-report tools, and none are based on the empirically derived hierarchy of defenses. This paper outlines the development of the defense mechanisms rating scale Q-sort for children (DMRS-Q-C), a 60-item, observer-rated tool for coding the use of defenses in child psychotherapy sessions. Modifications to the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scale Q-Sort for adults to create a developmentally relevant measure and the process by which expert child psychotherapists collaborated to develop the DMRS-Q-C are discussed. A clinical vignette describing the child’s defensive functioning as assessed by the innovative DMRS-Q-C method is also reported. Finally, we provide an overview of forthcoming research evaluating the validity of the DMRS-Q-C.

Key words: Defense mechanisms, child psychotherapy, assessment, DMRS, Q-sort

Introduction

Defenses - defined as automatic psychological operations that mediate an individual’s reaction to emotional conflicts and to internal or external stressors (APA, 2013) - are important aspects of mental functioning that mediate individual’s resilience and adaptation to life’s demands (Vaillant, 1995; Cramer, 2006). Adaptive defenses, such as altruism, humour, and sublimation, are in maintaining physical and mental health across the lifespan (Beresford, 2012; Conversano, 2021; Malone et al., 2013; Metzger, 2014). Conversely, over-reliance on immature defenses, such as projective identification and splitting, is associated with greater symptom severity (Boldrini et al., 2020; Prout et al., 2020), suicide risk (Hovanesian et al., 2009), personality disorders (Lingiardi & Giovanardi, 2017; Maffei et al., 1995; Kempe et al., 2021), insecure attachment (Békés et al., 2021a; Tanzilli et al., 2021), negative physical health outcomes (Di Giuseppe et al., 2018) and high level of stress (Aafjes-Van Doorn et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2021a).

Defense mechanisms also share similarities with the neuroscience construct of implicit emotion regulation (Rice & Hoffman, 2014), allowing them to be measured as observable manifestations of automatic emotion regulation strategies (Gross & Thompson, 2007) that can improve during psychotherapy (Babl et al., 2019; Kramer et al., 2013; Perry & Bond, 2012). With their emphasis on the therapeutic relationship as a mechanism of change, psychodynamic psychotherapies are particularly effective in addressing changes in defense mechanisms and in supporting the improvement of implicit emotion regulation and treatment response (de Roten et al., 2021; Prout et al., 2019).

The assessment of defense mechanisms is an important component of the diagnostic process described in the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, Second Edition (PDM-2) (Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017). The PDM-2 proposes a multidimensional and multiaxial approach that implies the assessment of mental functioning (MC Axis), emerging personality patterns and difficulties (PC Axis), symptom patterns and their subjective experience (SC Axis). In the specific section dedicated to childhood, the PDM-2 emphasizes a developmental perspective that is particularly useful in helping clinicians consider children’s defensive strategies in the context of their current developmental stage. Defense assessment plays a crucial role in promoting an accurate diagnosis of children’ mental functioning (MC Axis) and personality organization (PC Axis). Indeed, among children (as with adults), mental functions such as the capacity to deal with stress, manage impulses, and negotiate conflict are greatly influenced by defenses. These habitual modes of dealing with perceived or anticipated conflicts or stresses are closely related to children’s mental functioning and they impact overall level of personality organization.

Defense mechanisms follow an empirically derived, hierarchical categorization ranging from immature to mature (or maladaptive to adaptive) defenses (Prout et al., 2021a; Vaillant, 1971). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) classified the following seven defense levels, ranked from immature to mature: Action (Level 1), Major Image Distortion (Level 2), Disavowal (Level 3), Minor Image-Distortion (Level 4), Mental Inhibitions (Level 5 and 6), and High Adaptive (Level 7). Perry (1990) further expanded the Mental Inhibitions defense level by organizing the mechanisms within this level into two new levels, Neurotic (Level 5) and Obsessional (Level 6), to differentiate mechanisms that defended against thoughts and emotions, respectively. Action level defenses take form through physical actions or withdrawal from the individual. Major Image-Distortion level defenses significantly distort images and ideas of the self or others. Disavowal level defenses keep unwanted thoughts, urges, and emotions out of the individual’s mind with or without misattributing these factors to environmental or situational causes. Minor Image-Distortion level defenses involve mechanisms that distort the individual’s image sense of self, body, or others to regulate self-esteem. Finally, High Adaptive level defenses result in the healthiest form of adapting to stressors by promoting conscious awareness of thoughts, feelings, and urges while balancing any conflicting motives that still might be at play.

Despite this large body of evidence on the centrality of defenses in mediating distress and their association with overall mental health outcomes and symptom reduction in psychotherapy, less is known about the role of defense mechanisms in child psychotherapy. Defense mechanisms are observable in infancy (e.g. infant gaze) and change with age basing on neurophysiological and psychological acquisitions. Phebe Cramer’s research demonstrated the ontogenetic developmental line of defense mechanisms among children and adolescents (Cramer, 2003; Porcerelli et al., 2010). Cramer’s systematic assessment of defense mechanisms, primarily through the use of projective assessments, showed that children rely on immature and cognitively simple defenses (e.g., denial) during early childhood, and progress toward more complex defense mechanisms (e.g., projection and identification) as their cognitive abilities and self-awareness develop in late childhood and adolescence (Cramer, 2015). Several studies confirmed these findings, demonstrating that defenses follow a clear developmental trajectory based on chronological age (Cramer, 2008; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020b) and gender (Giovanardi et al., 2021; Tallandini & Caudek, 2009).

To date, instruments assessing defenses in children have relied primarily on projective assessment and selfreport instruments. Among the most popular, the Defense Mechanisms Manual is used to rate three defense mechanisms - denial, projection, and identification - as revealed in stories told to TAT and CAT cards (Cramer, 1991). This measure has demonstrated validity and reliability (Hibbard & Porcerelli, 1998; Porcerelli et al., 2010), however it provides limited information due to the small number of defenses assessed (Nimroody et al., 2019; Di Giuseppe et al., 2021b). Another method is the comprehensive assessment of defense style (CADS) (Laor et al., 2001), a 72-item questionnaire for assessing 28 defenses organized into three factors - other-oriented, self-oriented, and mature. The responder is asked to rate, using a Likert scale, the extent to which items characterize the usual behaviour of the child. The CADS has good concurrent and convergent validity and a stable factor structure (Wolmer et al., 2001). Other coding systems are specifically tailored to child’s play (Tallandini & Caudek, 2010). One of the most comprehensive and detailed measure is the Defense Mechanisms Manual for Children’s Doll Play (DMCP) (Nimroody et al., 2019) created to code 32 different defense mechanisms on 10 story stems chosen from the MacArthur Story Stem Battery, that can also be applied to many types of play. Despite the good psychometric properties of these measures, none rely on the totality of the empirically derived hierarchical organization of defense mechanisms (APA, 1994; Perry, 1990), limiting comparisons with the widely used measures for defenses assessment (Perry, 2014; Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021).

In order to respond to the need to detect the whole hierarchy of defense mechanisms (see Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021 for review) among children in both clinical and research settings, we developed the child version the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort for Children (DMRS-Q-C), based on the adult version of this measure, the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort (DMRSQ) (Di Giuseppe et al., 2014).

Materials and methods

Our main aim in developing the DMRS-Q-C was to maintain in the child version the theoretical and methodological advantages of the DMRS-Q adult version (Di Giuseppe et al., 2014). These advantages, described in detail in the DMRS-Q Manual (Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021) are numerous:

The overall defensive functioning score informs on the level of adaptiveness of the individual’s defensive functioning and can be used as an outcome measure.

The defensive category scores inform on how frequently the individual uses mature, neurotic and immature defenses.

The defense level scores inform on how frequently the individual uses defenses with common functions

The individual defense scores inform on the individual’s characteristic defense mechanisms and can be used in the assessment of micro-changes during the psychotherapy process.

The qualitative score also-called defensive profile narratives (DPN) - uniquely provided in the DMRSQ but not in other measures based on the DMRS (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020c; Berney et al., 2014; Perry, 1990) - informs on the individual’s most characteristic defensive patterns that contribute to determine the defensive profile.

The online DMRS-Q software that allows for free and unlimited coding of defense mechanisms from any electronic device connected to the internet.

The lack of necessity for transcriptions for coding defense mechanisms, which allows clinicians to monitoring session-by-session changes in patient’s defensive functioning (Tanzilli et al., 2017; 2018; 2020).

The short training required for its reliable use (Békés et al., 2021).

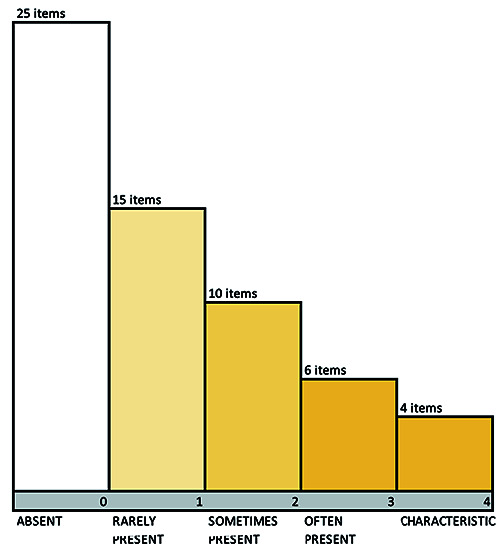

The first step toward the development of the DMRSQ- C was adapting the 150 items - five for each of 30 defenses - included in the DMRS-Q to be more appropriate to psychotherapy with patients between five and 13 years of age. For the majority of items, this required only the simple modification of a few words (i.e. ‘the child’ instead of ‘the individual’); however, in several instances items were rephrased to adapt to a developmentally appropriate, child perspective (Table 1). In line with our experience in child psychotherapy sessions and the small body of research on children’s defenses, where we observe a relatively small number of defenses used several times in a session, we decided to shorten the DMRS-Q-C to 60 items. Accordingly, a second step was asking a group of eight child psychologists and psychiatrists with advanced knowledge of defense mechanisms to rank-order the five items provided for each defense in relation to the definition and function of each defense mechanism described in the DMRS-Q manual. As a third step, we averaged the expert ratings and selected the two items ranked as most descriptive for each defense mechanism for inclusion in the final DMRS-Q set. Finally, we adapted the DMRS-Q-C forced distribution, which is the rating procedure used in all Q-sort methods to rankorder items according to criteria described in the manual (Block, 1978; Brown, 1993, 1995), to the shortened 60 item Q-set, as described in Figure 1.

Results

After ordering the 60 items into the five ordinal ranks corresponding to increasing level of intensity or frequency (from 0=absent to 4=characteristic), the rating is complete. To help the scoring procedure we developed the DMRSQ- C software that automatically provides qualitative and quantitative scores of the child’s defensive functioning. At this stage of the project the DMRS-Q-C software is only available to authors and associated research assistants who will utilize the tool in a forthcoming validation study. Later it will be available online alongside the parent adult version (link at: https://webapp.dmrs-q.com).

We identified a large sample of child psychotherapy videos to code with the newly developed DMRS-Q-C. Child psychotherapy sessions from a recent randomized controlled trial of Regulation Focused Psychotherapy for Children (RFP-C) (Hoffman et al., 2016; Prout et al., 2021b). RFP-C is a manualized play-based and verbal therapy psychodynamic treatment for children with externalizing problems. RFP-C conceptualizes disruptive behaviour problems as maladaptive attempts to regulate emotions (i.e. immature defenses) and fosters adaptation through a systematic interpretation of children’s maladaptive defense mechanisms (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020a; Prout et al., 2015). Children with externalizing symptoms experience implicit emotion dysregulation, struggling to tolerate painful emotions which results in further difficulties exploring the meaning behind their oppositional behaviours. Instead, these children engage in externalizing misbehaviours as a means of coping with their painful emotions (Rice & Hoffman, 2014). Disruptive behaviour is often not a conscious choice but rather a defense mechanism that creates a buffer between the child and his/her painful and intolerable affects. Defense mechanisms are particularly important as they can be clearly operationalized and used to measure implicit emotion regulation.

Table 1.

Example of item conversion from adult to child version.

| Measure | Item |

|---|---|

| DMRS-Q | When confronting emotionally charged topics, the subject tends not to address concerns directly and fully but wanders off to tangentially related topics that are emotionally easier for the subject to discuss or prefers to pay attention to someone else dealing with a similar situation. This can include preferring to read or watch a film portraying people dealing with similar problems. |

| DMRS-Q-C | When confronting emotionally charged topics, the child tends not to address concerns directly and fully but wanders off to tangentially related topics that are emotionally easier for the child to discuss or prefers to pay attention to someone else dealing with a similar situation. This can include consuming media that portrays people dealing with similar problems or developing imaginative play scenarios in which characters face similar problems. |

DMRS-Q, defense mechanisms rating scale Q-sort; DMRS-Q-C, defense mechanisms rating scale Q-sort for children.

The DMRS-Q-C allows for quantitative and qualitative description of a child’s defensive functioning after a clinical interview, play therapy session, or any form of talk therapy. An example of assessing defense mechanisms in children using the innovative DMRS-Q-C methodology is shown in the following clinical vignette.

Tom (pseudonym) is a seven-year-old boy with oppositional defiant disorder, participating in RFP-C. His 8th play session, right in the middle of the treatment, starts with involving the therapist in playing with guns that he builds with Lego blocks. Tom explains how the gun should be built and, finally, creates several little guns for the therapist (‘Here is yours!’). However, the child’s engagement with the therapist is an afterthought, consisting in sharing only a small, ineffective, or broken gun. The use of the defense undoing is also present few moments later, when the child uses his guns to outline a border between himself and the therapist (‘There is also a border here, like this’).

Whenever the child gets disappointed by the therapist’s words, play actions, and even movements, Tom denies the therapist’s impact on him (‘It doesn’t do anything’) or he acts out against the therapist in the play (i.e. he breaks some blocks, moves away, or shuts the therapist out of the play). Conversely, whenever the therapist acts consistently with the child’s needs, Tom shows an act of reparation mediating the previous acting out. For instance, when the therapist pretends to fall down after being ‘shot’, the child activates a cooperative response and offers the therapist a new tool to fight with. For most of the play, the child dominates the therapist with powerful weapons, in contrast to the therapist’s inadequate or broken tools. The child rationalizes this dynamic by giving inconsistent reasons for this imbalance, which is interpreted by the therapist during the play. However, Tom doesn’t seem concerned with the therapist’s interpretation; instead, he often passive aggressively responds with oppositional behaviours and comments that disavow her importance. For example, when the child displays concern about a noise coming from outside the room, the therapist responsively proposes they investigate the noise together; Tom agrees with her but then goes in a different direction, as if he wants to highlight the therapist’s inability to understand him. The therapist tries to investigate Tom’s anxiety about the noise and possible feelings of being in a danger, but he suddenly denies any sense of anxiety or fear and attempts to hurt the therapist within the play. When the therapist asserts the boundaries of the play and the importance of staying safe, Tom reacts very aggressively in the game by shooting the therapist whenever she starts talking. From this moment on, Tom sees the therapist as someone who must be destroyed because she is too frustrating. The child can only tolerate the therapist when she acts as if she is miserable, powerless, and defeated. Accordingly, he sees himself as someone powerful and threatening who takes pleasure in shooting the therapist. To sustain his defensive split between his own and others’ image, the child rationalizes his reasons by giving explanations for his behaviour with an omnipotent attitude (‘I like shooting you because you are an easy target’).

Figure 1.

The Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort for children forced distribution.

The child returns to undoing several times in the session in order to offset the impact of his aggressiveness. One example is when the therapist shows her worries (‘I wonder what I did to be attacked so much’). Tom seems to feel some compassion and invites her to build another gun for protection. However, he cannot tolerate that she might survive and keeps shooting her. The therapist does not react this time and this seems even more frustrating for Tom. He first responds by singing a song, and then keeps shooting her as if this will somehow alleviate his angry feelings. The more the child experiences frustration, the more aggressive he becomes during the play. All of these behaviours are also accompanied by the defense of isolation of affects. Tom does not show any expected feeling toward the character played by the therapist and keeps playing the omnipotent aggressor without appearing to feel touched, sad, or guilty. He plays as if his feelings are completely absent.

These redundant defensive patterns were coded with the DMRS-Q-C and resulted in the following DPN:

In response to interpersonal disappointment or disagreement the child tends to act impulsively, without reflection or considering the negative consequences. Whenever the child feels angry, disappointed or rejected, the child resorts to uncontrolled behaviours to escape from distressing feelings, such as reckless defiance of authority or hypomanic playfulness (ACTING OUT). At times when expressing an opinion or wish might be helpful, the child fails to express himself adequately, instead finding indirect, even annoying ways to show his or her opposition to the influence of others, for example, being silent (PASSIVE AGGRESSION). The child speaks of him or herself in a wholly negative way at times, as if there is nothing positive or redeeming about him or herself (SPLITTING OF SELF-IMAGE). The child attributes unrealistic negative characteristics to an object, such as being all-powerful, malevolent, threatening. As a result, he makes some effort to protect himself from its influence, even though this response appears unwarranted or exaggerated. The child expresses hatred toward someone or something and refuses to acknowledge anything that does not confirm the hatred (SPLITTING OF OTHERS’ IMAGE). Whenever asked about things the child did or felt, the child denies any involvement, does not want to talk about them or avoids explaining his reluctance (DENIAL). The child acts in a very self-assured way and asserts an ‘I can handle anything’ attitude, in the face of problems that he or she in fact cannot fully control (OMNIPOTENCE). The child conveys opinions about something or someone with a series of opposite or contradictory statements, as if uncomfortable with taking a clear stand one way or the other. After the child has done something that probably results in a feeling of guilt or shame, he makes an act of reparation, as if sorry. However, the child focuses on the act but avoids dealing with the sense of guilt or shame as one would whenever making a normal apology (UNDOING).

A summary of quantitative scores of Tom’s defensive functioning obtained from the DMRS-Q-C is presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Empirical research has highlighted the need of valid and reliable measures based on the gold-standard theory for the assessment of defense mechanisms. The DMRS represent the closest to a gold-standard approach and has inspired the development of several measures, as the one we presented in this article. The specialty of DMRS-based measures is that it informs on the function of defense mechanisms, the unconscious motives that suggests what internal conflicts behind the use of defense mechanisms (Perry, 2014; Di Giuseppe & Perry 2021). This become extremely important in child psychotherapy, where the patient’s ability of expressing him or herself directly is limited due to normal cognitive and psychological developmental processes (Cramer, 2015; Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017).

Defense mechanisms are strongly associated with personality in adults and adolescents (Kramer et al., 2013; Lingiardi et al., 1999; Perry & Bond, 2012). Recent studies have found that different personality traits show specific defensive profiles, consistent with defensive functioning observable in adults with similar personality traits (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020b). Furthermore, a recent empirical investigation has found that specific emerging personality patterns in children were significantly related to social and attention problems, aggressive and delinquent behaviour, and externalizing problems or disorders (Fortunato et al., 2021). In view of these findings, it appears that defense mechanisms influence personality development and help shape the developing child across the lifespan. Examination of defenses in childhood may provide a window into burgeoning personality development, allowing for a deeper understanding of childhood psychological functioning and developmental psychopathology.

The DMRS-Q-C offers the first observer-rated measure based on the widely accepted hierarchy of defense mechanisms and holding the unique strengths of the computerized and easy-to-use DMRS-Q (Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021). Although we are not able to present data on reliability and validity at present, our preliminary analyses suggested promising psychometric properties of the DMRS-Q-C comparable to that of other measures based on the DMRS (Békés et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2014; 2020c; Perry & Høglend, 1998; Prout et al., 2021a). The systematic assessment of defense mechanisms in children has the potential to foster greater understanding of both functional and pathological psychological development and may help clinicians more effectively address children’s defenses in the play therapy sessions, in the service of increasing resilience and adaptive ways of coping (Hoffman et al., 2016; Prout et al., 2019; Tanzilli & Gualco, 2020). In accordance with the PDM-2 approach, which provides a comprehensive method for conceptualizing childhood distress, the DMRSQ- C may offer a useful tool for identifying defense mechanisms assessment in children and in promoting an accurate clinical case formulation that can inform treatment (Lingiardi et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Tom’s defensive functioning assessed with the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort for Children quantitative scoring.

| Defensive functioning/category/level | DMRS-Q-C score (%) | Individual defense mechanism | DMRS-Q-C score (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall defensive functioning | 3.54 | L7: Suppression | 0 | |

| L7: Sublimation | 0 | |||

| Defensive category | L7: Self-observation | 2.90 | ||

| Mature (L7) | 8.70 | L7: Self-assertion | 1.45 | |

| Neurotic (L6 and L5) | 21.74 | L7: Humor | 1.45 | |

| Immature (L4, L3, L2, and L1) | 69.56 | L7: Anticipation | 1.45 | |

| L7: Altruism | 1.45 | |||

| Defense level | L7: Affiliation | 0 | ||

| Level 7 (L7): High-adaptive | 8.70 | L6: Isolation | 5.80 | |

| Level 6 (L6): Obsessional | 15.94 | L6: Intellectualization | 1.45 | |

| Level 5 (L5): Neurotic | 5.80 | L6: Undoing | 8.70 | |

| Level 4 (L4): Minor image-distorting | 14.49 | L5: Repression | 4.35 | |

| Level 3 (L3): Disavowal | 17.39 | L5: Dissociation | 0 | |

| Level 2 (L2): Major image-distorting | 20.29 | L5: Reaction Formation | 0 | |

| Level 1 (L1): Action | 17.39 | L5: Displacement | 1.45 | |

| L4: Devaluation of Self-image | 0 | |||

| Devaluation of Others’ image | 5.80 | |||

| L4: Idealization of Self-image | 1.45 | |||

| L4: Idealization of Others’ image | 0 | |||

| L4: Omnipotence | 7.25 | |||

| L3: Denial | 7.25 | |||

| L3: Rationalization | 5.80 | |||

| L3: Projection | 2.90 | |||

| L3: Autistic Fantasy | 1.45 | |||

| L2: Splitting of Self-image | 7.25 | |||

| L2: Splitting of Others’ image | 11.9 | |||

| L2: Projective Identification | 1.45 | |||

| L1: Passive aggression | 7.25 | |||

| L1: Help-rejecting Complaining | 0 | |||

| L1: Acting out | 10.14 |

DMRS-Q-C, Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort for Children.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Brittany Gurney, Leon Hoffman, Emma Kolpon, Tatianna Kufferath-Lin, Timothy Rice, Dani Sessler, and Sara Winograd for their helpful contribution to the DMRS-Q-C item selection process. We are also grateful to Lauren Smith and Carly Teperman for the many ways they have supported this project.

References

- Aafjes-Van Doorn K., Békés V., Xiaochen L., Prout T. A., (2021). What do therapist defence mechanisms have to do with their experience of professional self-doubt and vicarious trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647503. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Babl A. Grosse Holtforth M., Perry J. C. Schneider N. Dommann E. Heer S. Caspar F., (2019). Comparison and change of defence mechanisms over the course of psychotherapy in patients with depression or anxiety disorder: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 212-220. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Aafjes-Van Doorn K., Spina D., Talia A., Starrs C. J., Perry J. C., (2021a). The relationship between defence mechanisms and attachment as measured by observer-rated methods in a sample of depressed patients: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648503. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Prout T. A., Di Giuseppe M., Wildes Ammar L., Kui T., Arsena G., Conversano C. (2021b). Initial validation of the defence mechanisms rating scales Q-sort: A comparison of trained and untrained raters. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9(2). doi:10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3107. [Google Scholar]

- Beresford T. P. (2012). Psychological adaptive mechanisms: Ego defence recognition in practice and research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berney S., de Roten Y., Beretta V., Kramer U., Despland J. N., (2014). Identifying psychotic defences in a clinical in- terview. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 70(5), 428-439. doi:10.1002/jclp.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. (1978). The Q-Sort method in personality assessment and psychiatric research. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini T. Lo Buglio, G., Giovanardi G. Lingiardi V. Salcuni S., (2020). Defence mechanisms in adolescents at high risk of developing psychosis: An empirical investigation. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 23(1), 4-15. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2020.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. R. (1993). A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16, 91-138. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. R. (1995). Q methodology as the foundation for a science of subjectivity. Operant Subjectivity, 18, 1-16. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (1991) The development of defence mechanisms. Berlin: Springer. Available from: 10.1007/978-1-4613-9025-1_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2003). Personality change in later adulthood is predicted by defence mechanism use in early adulthood. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 76-104. doi:10.1016/ S0092-6566(02)00528-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2006). Protecting the self: Defence mechanisms in action. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2008). Seven pillars of defence mechanism theory. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1-19. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00135.x. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2015). Defence mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(2), 114-122. doi:10.1080/00223891.2014.947997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conversano C. (2021) The psychodynamic approach during COVID-19 emotional crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 670196. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roten Y., Djillali S., von Rotten F. C., Despland J.-N., Ambresin G. (2021). Defence mechanisms and treatment response in depressed patients. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 633939. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Ciacchini R., Micheloni T., Bertolucci I., Marchi L., Conversano C., (2018). Defence mechanisms in cancer patients: a systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 115, 76-86. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., (2021). The hierarchy of defence mechanisms: assessing defensive functioning with the defence mechanisms rating scales Q-sort (DMRS-Q). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 718440. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.718440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Prout T. A., Rice T., Hoffman L., (2020a). Regulation-focused psychotherapy for children (RFP-C): Advances in the treatment of ADHD and ODD in childhood and adolescence. Frontiers inPpsychology, 11, 572917. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Conversano C., Gelo O. C. G., Gennaro A. (2020b). Defence mechanisms, gender, and adaptiveness in emerging personality disorders in adolescent outpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 208(12), 933-941. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Lucchesi M., Michelini M., Vitiello S., Piantanida A., Fabiani M., Maffei S., Conversano C. (2020c). Preliminary reliability and validity of the DMRS-SR-30, a novel self-report based on the defence mechanisms rating scales. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 870. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J.C., Petraglia J., Janzen J., Lingiardi V., (2014). Development of a Q-Sort version of the defence mechanism rating scales (DMRS-Q) for clinical use. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 452-465. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Prout T. A., Conversano C., (2021a). Editorial: Recent empirical research and methodologies in defence mechanisms: Defenses as fundamental contributors to adaptation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 802602. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.802602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Nepa G., Prout. T. A., Albertini F., Marcelli S., Orrù G., Conversano C. (2021b). Stress, burnout, and resilience among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency: the role of defence mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 5258. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato A., Tanzilli A., Lingiardi V., Speranza A. M., (2021). Childhood personality assessment Q-sort (CPAPQ): a clinically and empirically procedure for assessing traits and emerging patterns of personality in childhood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 6288. doi:10.3390/ijerph18126288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanardi G., Mirabella M., Di Giuseppe M., Lombardo F., Speranza A. M., Lingiardi V. (2021). Defensive functioning of individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria at the beginning of their hormonal treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 665547. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.665547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J., Thompson R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In Gross J. J. (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3-24). New York, NY: Guildford Press. doi:10.1080/00140130600971135. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard S., Porcerelli J., (1998). Further validation for the Cramer defence mechanism manual. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70(3), 460-483. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa 7003_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L., Rice T. R., Prout T. A., (2016). Manual of regulation- focused psychotherapy for children (RFP-C) with externalizing behaviours: A psychodynamic approach. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hovanesian S., Isakov I., Cervellione K. L., (2009). Defence mechanisms and suicide risk in major depression. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(1), 74-86. doi:10.1080/1381111080257 2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe L., Bohn J., Remmers C., Hörz-Sagstetter S. (2021). It’s not that great anymore: The central role of defence mechanisms in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 661948. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer U., de Roten Y., Perry J. C., Despland J. N., (2013). Change in defence mechanisms and coping patterns during the course of 2-year-long psychotherapy and psychoanalysis for recurrent depression: a pilot study of a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(7), 614-620. doi:10.1097/NMD. 0b013e3182982982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laor N., Wolmer L., Cicchetti D. V., (2001). The comprehensive assessment of defence style: measuring defence mechanisms in children and adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(6), 360-368. doi:10.1097/00005053-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Giovanardi G., (2017). Challenges in assessing personality of individuals with gender dysphoria with the SWAP-200. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 40(7), 693-703. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., McWilliams N., Bornstein R. F., Gazzillo F., Gordon R. M., (2015). The psychodynamic diagnostic manual version 2 (PDM-2): assessing patients for improved clinical practice and research. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32(1), 94-115. doi:10.1037/a0038546. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., McWilliams N. (Eds.). (2017). Psychodynamic diagnostic manual: PDM-2 (2nd ed.). London: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Lonati C., Delucchi F., Fossati A., Vanzulli L., Maffei C., (1999). Defence mechanisms and personality disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(4), 224-228. doi:10.1097/00005053-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei C., Fossati A., Lingiardi V., Madeddu F., Borellini C., Petrachi M., (1995). Personality maladjustment, defences, and psychopathological symptoms in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Personality Disorders, 9(4), 330-345. doi:10.1521/pedi.1995.9.4.330. [Google Scholar]

- Malone J. C., Cohen S., Liu S. R., Vaillant G. E., Waldinger R. J., (2013). Adaptive midlife defence mechanisms and latelife health. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(2), 85-89. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger J. A. (2014). Adaptive defence mechanisms: function and transcendence. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 478-488. doi:10.1002/jclp.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimroody T., Hoffman L., Christian C., Rice T., Murphy S., (2019). Development of a defence mechanisms manual for children’s doll play (DMCP). Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 18, 58-70. doi:10.1080/15289168.2018.1565005. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (1990). Defence Mechanism Rating Scales (DMRS). 5th ed. Cambridge, MA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (2014). Anomalies and specific functions in the clinical identification of defence mechanisms, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 406-418. doi:10.1002/jclp.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Bond . M. (2012). Change in defence mechanisms during long-term dynamic psychotherapy and five-year outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 916-925. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Høglend P., (1998). Convergent and discriminant validity of overall defensive functioning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186(9), 529-535. doi:10.1097/ 00005053-199809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli J. H., Thomas S., Hibbard S., Cogan R., (1998). Defence mechanisms development in children, adolescents, and late adolescents. Journal of Personality Assessment, 71(3), 411-420. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa7103_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli J. H., Cogan R., Kamoo R., Miller K., (2010). Convergent validity of the defence mechanisms manual and the defensive functioning scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(5), 432-438. doi:10.1080/00223891.2010.497421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Gerber L. E., Gaines E., Hoffman L., Rice T. R., (2015). The development of an evidence-based treatment: regulation- focused psychotherapy for children with externalizing disorders. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 41(3), 255-271. [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Malone A., Rice T., Hoffman L., (2019). Resilience, defence mechanisms, and implicit emotion regulation in psychodynamic child psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy: On the Cutting Edge of Modern Developments in Psychotherapy, 49(4), 235-244. doi:10.1007/s10879-019-09423-w. [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Zilcha-Mano S., Aafjes-van Doorn K., Bekes V., Christman-Cohen I., Whisler K., Di Giuseppe M. (2020) Identifying predictors of psychological distress during COVID-19: A machine learning approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586202. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Di Giuseppe M., Zilcha-Mano S., Perry J. C., Conversano C., (2021a). Psychometric properties of the defence mechanisms rating scales-self-report-30 (DMRS-SR- 30): internal consistency, validity and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1080/00223891.2021.2019053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Rice T., Chung H., Gorokhovsky Y., Murphy S., Hoffman L. (2021b). Randomized controlled trial of regulation focused psychotherapy for children: A manualized psychodynamic treatment for externalizing behaviours. Psychotherapy Research. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1080/10503307.2021.1980626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T. R., Hoffman L., (2014). Defence mechanisms and implicit emotion regulation: A comparison of a psychodynamic construct with one from contemporary neuroscience. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 62, 693-708. doi:10.1177/0003065114546746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallandini M. A., Caudek C., (2010). Defence mechanisms development in typical children. Psychotherapy Research, 20(5), 535-545. doi:10.1080/10503307.2010.493536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Di Giuseppe M., Giovanardi G., Boldrini T., Caviglia G., Conversano C., Lingiardi V., (2021). Mentalization, attachment, and defence mechanisms: a Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual-2-oriented empirical investigation. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 24(1), 31-41. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2021.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Gualco I., Baiocco R., Lingiardi V., (2020). Clinician reactions when working with adolescent patients: the therapist response questionnaire for adolescents. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(5), 616-627. doi:10.1080/ 00223891.2019.1674318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Lingiardi V., Hilsenroth M., (2018). Patient SWAP-200 personality dimensions and FFM traits: Do they predict therapist responses? Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(3), 250-262. doi:10.1037/per 0000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Muzi L., Ronningstam E., Lingiardi V., (2017). Countertransference when working with narcissistic personality disorder: An empirical investigation. Psychotherapy, 54(2), 184-194. doi:10.1037/pst0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Gualco I., (2020). Clinician emotional responses and therapeutic alliance when treating adolescent patients with narcissistic personality disorder subtypes: A clinically meaningful empirical investigation. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34, 42-62. doi:10.1521/pedi.2020.34.supp.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H., Araujo K. B., Koopman C. (2001). The response evaluation measure (REM-71): A new instrument for the measurement of defences in adults and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 467-473. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp. 158.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1995). The wisdom of the ego. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1971). Theoretical hierarchy of adaptive ego mechanisms: A 30-year follow-up of 30 men selected for psychological health. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24(2), 107-118. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750080011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolmer L., Laor N., Cicchetti D. V., (2001). Validation of the comprehensive assessment of defence style (CADS): mothers’ and children’s responses to the stresses of missile attacks. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(6), 369-376. doi:10.1097/00005053-200106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]