Abstract

This cross-sectional study ranks the prevalent diagnoses among hospitalized children and related costs by hospital type.

Approximately 2 million nonbirth pediatric hospitalizations occur annually in the US,1 but scant evidence guides inpatient pediatric care. A critical first step in prioritizing research on hospitalized children is the identification of costly and common reasons for hospitalization,2 but existing studies are either limited in scope or outdated.1,2,3 In this study, we aimed to identify the demographic characteristics of hospitalized children nationally and rank the most common and costly diagnoses in this population.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2016 (most recent available) Kids' Inpatient Database (KID), the only all-payer, administrative data set designed for assessing hospitalizations of children in the US.4 We included all nonbirth hospital discharges for children aged 0 to 17 years, and we applied discharge weights to produce national estimates. Race and ethnicity were self-identified by parents and families using each hospital’s classification system (Asian or Pacific Islander; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Native American; White, non-Hispanic; and other [unlisted race and ethnicity category and more than 1 race and ethnicity]). Records were excluded if their primary diagnosis or cost data were missing (n = 32 310 excluded [1.2%, unweighted]). We grouped primary diagnoses using the Pediatric Clinical Classification System codes3,5 and rank-ordered total prevalence and cost by hospital type. The eMethods in the Supplement provides additional information on our methods. This study was deemed exempt from review by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board, which also waived the informed consent requirement because the study used a deidentified data set. Data analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), from April 19 to July 28, 2021.

Results

An estimated 1 777 023 nonbirth pediatric hospitalizations occurred in 3768 US hospitals in 2016 (Table). Most hospitalizations involved children with 1 or more chronic medical conditions and children residing in communities with below-average median incomes (first or second quartile). We found that 54.3% of hospitalizations took place in urban teaching hospitals (n = 960 947), 9.6% in urban nonteaching hospitals (n = 170 531), 31.6% in freestanding children’s hospitals (n = 559 850), and 4.4% in rural hospitals (n = 78 695).

Table. Characteristics of Nonbirth, Pediatric Hospitalizations in the United States, 2016 (N = 1 777 023).

| Patient characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| <1 | 447 906 (25.3) |

| 1-4 | 377 887 (21.3) |

| 5-12 | 448 666 (25.3) |

| 13-17 | 495 563 (28.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 863 941 (48.8) |

| Male | 913 082 (51.2) |

| Chronic medical condition | |

| None | 753 900 (42.6) |

| Noncomplex, chronic condition | 511 172 (28.9) |

| Complex, chronic condition | 504 951 (28.5) |

| Median income quartile by zip code | |

| 1st | 563 907 (31.9) |

| 2nd | 430 540 (24.3) |

| 3rd | 407 644 (23.0) |

| 4th | 341 711 (19.3) |

| Missing data | 26 161 (1.5) |

| Primary payer | |

| Government | 976 467 (55.1) |

| Private | 676 778 (38.2) |

| Self-pay, other payer, or missing data | 118 354 (6.7) |

| Race and ethnicitya | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 54 349 (3.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 283 687 (16.0) |

| Hispanic | 369 213 (20.9) |

| Native American | 16 500 (0.9) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 793 760 (44.8) |

| Otherb | 89 074 (5.0) |

| Missing data | 163 356 (9.2) |

| Elective hospitalization | 331 608 (18.7) |

| Accompanying ED record | 894 156 (50.5) |

| Transfer status | |

| Not a transfer | 1 465 707 (82.8) |

| Transferred inc | 296 355 (16.7) |

| Missing data | 8359 (0.5) |

| Discharge disposition | |

| Routine | 1 640 829 (92.7) |

| Transfer to another facility | 65 741 (3.7) |

| Home health | 49 283 (2.8) |

| AMA | 2710 (0.2) |

| Death | 9746 (0.6) |

| Unknown or missing data | 1491 (0.1) |

| LOS, median (IQR), d | 3 (1-5) |

Abbreviations: AMA, against medical advice; ED, emergency department; LOS, length of stay.

Race and ethnicity were self-identified by parents and families using each hospital’s classification system.

Other included both unlisted categories and more than 1 race and ethnicity.

Transferred in refers to transfer from another acute care hospital.

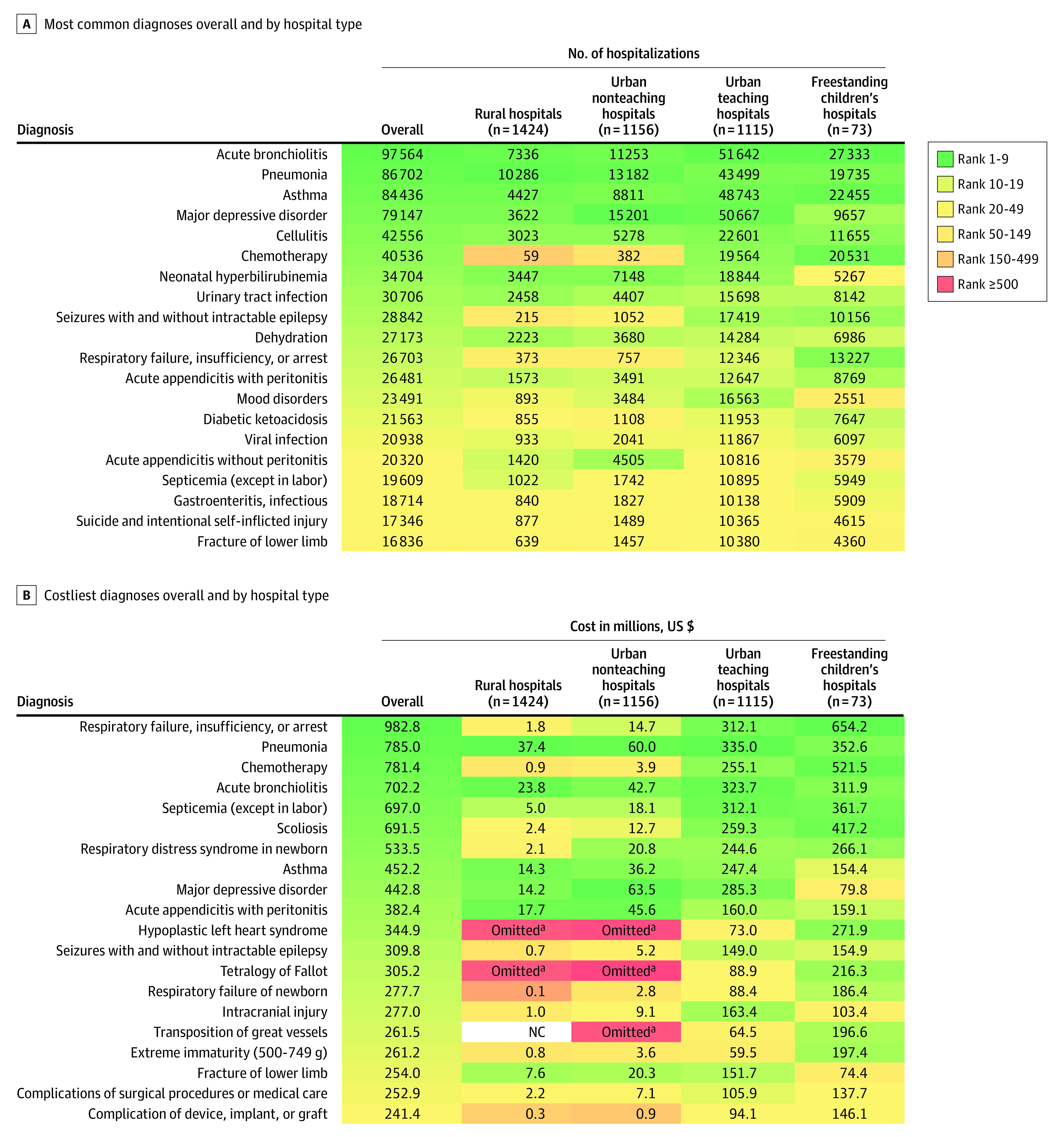

Figure, A illustrates the diagnosis prevalence rankings. The most common diagnoses overall were bronchiolitis (n = 97 564 hospitalizations), pneumonia (n = 86 702 hospitalizations), asthma (n = 84 436 hospitalizations), major depressive disorder (n = 79 147 hospitalizations), and cellulitis (n = 42 556 hospitalizations). Both major depressive disorder (rank 1 in urban nonteaching hospitals; n = 15 201 hospitalizations) and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (rank 5 in urban nonteaching hospitals; n = 7148 hospitalizations) were ranked higher outside of freestanding children’s hospitals (in freestanding children’s hospitals, rank 8 [n = 9657 hospitalizations] and rank 20 [n = 5267 hospitalizations], respectively). Chemotherapy, seizures, and respiratory failure were ranked higher in freestanding children’s hospitals (ranks 3, 5, and 7, respectively).

Figure. Most Common and Costly Diagnoses in Pediatric Hospitalizations, Overall and by Hospital Type.

NC indicates no cases.

aOmitted because of the reporting or disclosure policies of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Figure, B illustrates the diagnosis cost rankings. The costliest diagnoses overall were respiratory failure ($982.8 million), pneumonia ($785 million), chemotherapy ($781.4 million), bronchiolitis ($702.2 million), and septicemia ($697 million). Both asthma (rank 4 in rural hospitals; $14.3 million) and major depressive disorder (rank 5 in rural hospitals; $14.2 million) were ranked higher outside of freestanding children’s hospitals (rank 17 [$154.4 million] and rank 44 [$80 million], respectively). Respiratory failure, chemotherapy, septicemia, scoliosis, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome were ranked higher in freestanding children’s hospitals (ranks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7, respectively). Diagnoses with both high prevalence and cost overall included bronchiolitis, pneumonia, asthma, and major depressive disorder.

Discussion

Most pediatric hospitalizations took place outside of freestanding children’s hospitals, and the most common and costly diagnoses differed by hospital type. We believe these findings help guide the selection of high-priority diagnoses for pediatric research and quality improvement efforts that would make the greatest impact for children across the US. Future research and quality improvement prioritization efforts are needed, which should (1) leverage the findings from this study; (2) engage a wide spectrum of stakeholders (eg, parents or caregivers, nurses, and administrators) in the care of hospitalized children; and (3) incorporate additional factors such as practice variation, health disparities, and preventable harms.

One important finding was the increase in hospitalizations for major depressive disorder since 2012 (from rank 9 [n = 28 914 hospitalizations] in 2012 to rank 4 [n = 79 147 hospitalizations] in 2016).1 Recent data suggested that additional increases in mental health hospitalizations were associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.6 These findings reinforce the need to identify effective interventions for children who are hospitalized with mental health disorders.

Study limitations included the data in the KID database. Because the KID database contains discharge-level rather than patient-level records,4 the diagnoses represented by multiple hospitalizations from single patients could not be identified. In addition, the most recent KID data available were from 2016 and may not reflect current health care use. The study focused on primary diagnoses; therefore, it may have underestimated diagnoses that are less frequently selected as primary diagnoses.

eMethods. Detailed Study Methods

References

- 1.Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al. ; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network . Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155-1164. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill PJ, Anwar MR, Thavam T, et al. ; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting (PRIS) Network . Identifying conditions with high prevalence, cost, and variation in cost in US children’s hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2117816. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Overview of the Kids' Inpatient Database (KID). Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp

- 5.Children's Hospital Association . Pediatric Clinical Classification System (PECCS) codes. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

- 6.Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Detailed Study Methods