This cohort study compares COVID-19 incidence, risk, outcome severity, and treatment response between immunocompromised individuals and those without immune dysfunction conditions before and after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Key Points

Question

Is immune dysfunction associated with an increased risk for COVID-19 breakthrough infection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination?

Findings

In this cohort study of 664 722 patients who received at least 1 dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, those with immune dysfunction, such as HIV infection, rheumatoid arthritis, and solid organ transplant, had a higher rate for COVID-19 breakthrough infection and worse outcomes after full or partial vaccination, compared with persons without immune dysfunction.

Meaning

The findings suggest that persons with immune dysfunction are at much higher risk for contracting a breakthrough infection and thus should use nonpharmaceutical interventions (eg, mask wearing) and alternative vaccination approaches (eg, additional dose or immunogenicity testing) even after full vaccination.

Abstract

Importance

Persons with immune dysfunction have a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes. However, these patients were largely excluded from SARS-CoV-2 vaccine clinical trials, creating a large evidence gap.

Objective

To identify the incidence rate and incidence rate ratio (IRR) for COVID-19 breakthrough infection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among persons with or without immune dysfunction.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), a partnership that developed a secure, centralized electronic medical record–based repository of COVID-19 clinical data from academic medical centers across the US. Persons who received at least 1 dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine between December 10, 2020, and September 16, 2021, were included in the sample.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Vaccination, COVID-19 diagnosis, immune dysfunction diagnoses (ie, HIV infection, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, solid organ transplant, and bone marrow transplantation), other comorbid conditions, and demographic data were accessed through the N3C Data Enclave. Breakthrough infection was defined as a COVID-19 infection that was contracted on or after the 14th day of vaccination, and the risk after full or partial vaccination was assessed for patients with or without immune dysfunction using Poisson regression with robust SEs. Poisson regression models were controlled for a study period (before or after [pre– or post–Delta variant] June 20, 2021), full vaccination status, COVID-19 infection before vaccination, demographic characteristics, geographic location, and comorbidity burden.

Results

A total of 664 722 patients in the N3C sample were included. These patients had a median (IQR) age of 51 (34-66) years and were predominantly women (n = 378 307 [56.9%]). Overall, the incidence rate for COVID-19 breakthrough infection was 5.0 per 1000 person-months among fully vaccinated persons but was higher after the Delta variant became the dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain (incidence rate before vs after June 20, 2021, 2.2 [95% CI, 2.2-2.2] vs 7.3 [95% CI, 7.3-7.4] per 1000 person-months). Compared with partial vaccination, full vaccination was associated with a 28% reduced risk for breakthrough infection (adjusted IRR [AIRR], 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68-0.76). People with a breakthrough infection after full vaccination were more likely to be older and women. People with HIV infection (AIRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.18-1.49), rheumatoid arthritis (AIRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.09-1.32), and solid organ transplant (AIRR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.96-2.38) had a higher rate of breakthrough infection.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that full vaccination was associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 breakthrough infection, regardless of the immune status of patients. Despite full vaccination, persons with immune dysfunction had substantially higher risk for COVID-19 breakthrough infection than those without such a condition. For persons with immune dysfunction, continued use of nonpharmaceutical interventions (eg, mask wearing) and alternative vaccine strategies (eg, additional doses or immunogenicity testing) are recommended even after full vaccination.

Introduction

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have been found to be highly effective and safe in both clinical trials and real-world settings.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Breakthrough infection, which is defined as COVID-19 infection after an individual has completed all required doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine with a typical 14-day lag period, is rare in the general population.5,6,8 In the US, 22 115 breakthrough infection cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) after approximately 183 million persons received full vaccination by September 27, 2021.9,10 However, because most of the breakthrough cases were asymptomatic or had mild disease,9 surveillance data likely reflect underreported cases.

A recent study observed that persons with immune dysfunction, including those living with HIV or receiving immunosuppressant medications (ie, recipients of solid organ transplant [SOT]), have a higher risk for developing severe COVID-19 outcomes.11 Whether a weakened immune system might prevent these individuals from responding to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has not been examined in a large-scale real-world setting. Marked immune deficiency, noted by lower CD4 cell counts, often indicates antibody responses to vaccines among persons living with HIV.12,13 Common immunosuppressant medications (eg, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolic acid) to prevent allograft rejection among SOT recipients affect the immune response to vaccination.14,15 Furthermore, treatment regimens (eg, monoclonal antibody therapies, corticosteroids, or methotrexate) for autoimmune diseases (ie, multiple sclerosis [MS] and rheumatoid arthritis [RA]) might interfere with the immunogenicity of vaccines and the development of an adequate immune response. Patients with cancer, especially those with hematologic cancers who are undergoing bone marrow transplantation (BMT) with ensuing long-lasting T-cell deficiency, also have suboptimal immune response to vaccination.16,17

A large evidence gap exists for patients with immune dysfunction because they were largely excluded from SARS-CoV-2 vaccine clinical trials.2,3 Limited data indicated that immunocompromised patients demonstrated weakened immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.18,19,20,21,22,23 Studies that evaluated antibody titers as proxies of postvaccine immunogenicity identified lower immune responses in some groups of persons with immune dysfunction.18 However, it remains unclear whether such proxies of immunogenicity are associated with the real-world effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Hence, using a national sample of US patients, we conducted this study to identify the incidence rate (IR) and incidence rate ratio (IRR) for COVID-19 breakthrough infection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among persons with or without immune dysfunction.

Methods

Design and Setting

The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) is a partnership that is supported and overseen by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The N3C developed a secure and centralized electronic medical record (EMR)–based repository of COVID-19 clinical data, including testing, diagnoses, and vaccination data, submitted by partner health care organizations (predominantly academic medical centers) across the US. The design, data collection, sampling approach, and data harmonization methods used by the N3C have been described previously24,25 and are summarized in eMethods 1 to 5 in Supplement 1. Each partner site contributes demographic, medication, laboratory, diagnosis, and vital status data to the central data repository, and the data are harmonized into the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership data model (eMethods 3 and eAppendix in Supplement 1). Deidentified data are transferred and accessible through the N3C Data Enclave under a data-sharing agreement, which is approved under the authority of the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board and with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine serving as a central institutional review board. This cohort study received approval from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. No informed consent was obtained because the study used deidentified data. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.26

For the current retrospective cohort study, we included patients in the N3C Data Enclave who (1) received at least 1 dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine between December 10, 2020, and September 16, 2021, and (2) had data that passed initial quality checks (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). We used December 10, 2020, the date that the US Food and Drug Administration approved the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for general use,27 as the beginning of the study observation period. The end of the observation period was October 14, 2021. To provide at least 14 days of follow-up after vaccination and account for the lag in data reporting, we included patients who were vaccinated on or before September 16, 2021. To account for changes in COVID-19 breakthrough infection rates attributable to the highly contagious Delta variant, we used June 20, 2021, as the date by which to stratify the follow-up period into a pre– or post–Delta variant period. The date was based on the CDC report of Delta being the dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain (>50%) in the US.28

Vaccination and Case Definition

Key concept definitions are provided in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. The data set we used included the 3 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines with Food and Drug Administration authorization (2 mRNA vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech [BNT162b2] and Moderna [mRNA-1273], and 1 viral vector vaccine from Johnson & Johnson/Janssen [JNJ-784336725]) and other vaccines (eg, from AstraZeneca). We defined full vaccination as completion of the recommended dosing regimen of any vaccine (2 doses for mRNA vaccines, 1 dose for Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine, or 2 doses for other vaccines) and partial vaccination as receipt of only 1 dose of an mRNA or other vaccine.

We followed the N3C COVID-19 diagnosis definition,24,25 which is publicly available.29 Patients with COVID-19 had a positive result from 1 of a set of a priori–defined tests (included real-time polymerase chain reaction, antigen, and antibody tests) and diagnostic conditions based on International Classification of Diseases codes.30 We excluded positive antibody test results from the COVID-19 diagnosis after December 10, 2020, because a portion of antibody tests were requested by patients as a confirmation of their immune response after vaccination. Of all breakthrough infection cases, 98% were confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction or antigen test and 2% were confirmed by diagnostic conditions. To allow for immune response, we defined breakthrough infection as a COVID-19 infection that was contracted on or after the 14th day of vaccination.

Preexisting Conditions and Covariates

Demographic characteristics (age, sex, and race and ethnicity [which were self-identified in the EMR of the partner sites]) and diagnoses of preexisting conditions (history of HIV infection, MS, RA, SOT, BMT, and other comorbid conditions) were identified from January 1, 2018, until either the date of breakthrough infection or the end of study observation for non–breakthrough infection cases. Sample distribution of patients with immune dysfunction by N3C partner sites is reported in eMethods 4 and 5 in Supplement 1. The number of comorbidities (including severe heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, dementia, pulmonary diseases, liver disease, diabetes, kidney diseases, and cancer) was classified into 4 groups: 0, 1, 2, 3 or more. Geographic regions were identified according to residential zip codes and then classified according to infection rates and sampling density into 5 categories (Northeast, Midwest, West, South, or unknown) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

COVID-19 Outcomes

Disease severity of COVID-19 was defined using EMR classification procedures and condition codes, which were categorized by the COVID-19 Clinical Progression Scale established by the World Health Organization31 and reported previously11 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Death was identified by date of death or transfer to hospice. We identified the most severe event within 45 days after COVID-19 diagnosis and combined outcomes into outpatient visit only, inpatient hospitalization, or severe outcomes (eg, mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death). We compared the severity of COVID-19 outcomes in breakthrough infection vs prevaccination cases.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics at first dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine are presented for all participants, people without immune dysfunction, and people with specific immune dysfunction conditions (HIV infection, MS, RA, SOT, and BMT). We assigned patients to each immune dysfunction group on a mutually exclusive basis. If multiple conditions were present (0.1% had ≥2 conditions), patients were assigned to the highest risk group (HIV infection < MS < RA < SOT < BMT). We estimated unadjusted and adjusted IRRs (AIRRs) for COVID-19 breakthrough infection with 95% CIs using Poisson regression models with robust SEs, comparing people with specific immune dysfunction conditions (HIV infection, MS, RA, SOT, or BMT group vs non–immune dysfunction group) to people without these conditions. Poisson regression model 1 was adjusted for a study period (pre– or post–Delta variant period: June 20, 2021), full vaccination status, COVID-19 infection before vaccination, demographic characteristics, geographic location, and comorbidity burden. Poisson regression model 2 was adjusted for model 1 covariates and immune dysfunction group.

Person-time (at risk) accrued from the date of the first dose of the vaccine to the date of breakthrough infection, death, transfer to hospice, or October 14, 2021, whichever occurred first. Vaccine status was considered a time-varying variable for patients who received the mRNA or other vaccines, and full vaccination for patients who received the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine was considered a time-fixed variable. Participants contributed person-time to partial vaccination status from 14 days after the first dose of the vaccine to the date of the second dose, breakthrough infection, or censoring, whichever occurred first. Participants contributed person-time to full vaccination status from 14 days after all required doses of the vaccine to the date of breakthrough infection or censoring, whichever occurred first. We controlled for study period (pre– or post–Delta variant dominance) and previous COVID-19 diagnosis before the first dose of the vaccine. Other covariates were selected on the basis of data availability, completeness, quality, and a priori knowledge of relevance.11,24,30 To account for other immune dysfunction groups that were not included in the primary analyses, we sequentially excluded from sensitivity analyses those individuals with a history of cancer or other rheumatic diseases (eg, spondyloarthritis, gout, systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, and rheumatoid lung disease). To account for the potential impact of COVID-19 before vaccination, we conducted a separate sensitivity analysis. We used Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves to demonstrate time to breakthrough infection by immune dysfunction status. Descriptive statistics were used to compare COVID-19 disease severity in cases before and after vaccination as well as in patients with and without immune dysfunction.

P = .05 indicated statistical significance. All analyses were conducted in the N3C Data Enclave using SparkR package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Of the 664 722 patients in the N3C sample who received at least 1 dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, with 4 436 139 person-months of follow-up, more than 90% received an mRNA vaccine (n = 633 365 [95.3%]) and completed all recommended doses (n = 604 035 [90.9%]). The sample included patients with a median (IQR) age of 51 (34-66) years (although 5.0% of patients were younger than 18 years), 378 307 women (56.9%), and 286 415 men (43.1%). The sample comprised 31 697 Asian American/Pacific Islander (4.8%), 111 457 Hispanic (16.8%), 70 093 non-Hispanic Black (10.5%), and 394 397 non-Hispanic White (59.3%) individuals as well as 38 309 persons (5.8%) who identified as having other (eg, multiple, unknown, or self-reported other) race and ethnicity (Table 1). We identified 35 512 patients (5.3%) with immune dysfunction. Compared with people without immune dysfunction, those in the SOT, BMT, or RA groups were older; those with HIV infection or SOT recipients were more likely to have a non-Hispanic Black race and ethnicity; and those with immune dysfunction condition were more likely to have 3 or more comorbid conditions.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With at Least 1 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination .

| Variable | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N3C sample (n = 664 722) | Patients without immune dysfunction (n = 629 211) | Patients with specific immune dysfunction | |||||

| HIV infection (n = 8536) | MS (n = 2970) | RA (n = 13 445) | SOT (n = 8688) | BMT (n = 1872) | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 51 (34-66) | 51 (33-66) | 51 (37-60) | 54 (41-65) | 65 (54-74) | 59 (47-67) | 60 (48-68) |

| Female sex | 378 307 (56.9) | 359 669 (57.2) | 2187 (25.6) | 2236 (75.3) | 9941 (73.9) | 3506 (40.4) | 768 (41.0) |

| Male sex | 286 415 (43.1) | 269 542 (42.8) | 6349 (74.4) | 734 (24.7) | 3504 (26.1) | 5182 (59.6) | 1104 (59.0) |

| Race and ethnicitya | |||||||

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 31 697 (4.8) | 30 527 (4.9) | 350 (4.1) | 31 (1.0) | 318 (2.4) | 402 (4.6) | 69 (3.7) |

| Hispanic | 111 457 (16.8) | 105 742 (16.8) | 1942 (22.8) | 233 (7.8) | 1665 (12.4) | 1648 (19.0) | 227 (12.1) |

| Non-Hispanic | |||||||

| Black | 70 093 (10.5) | 64 396 (10.2) | 1865 (21.8) | 385 (13.0) | 1725 (12.8) | 1532 (17.6) | 190 (10.1) |

| White | 394 397 (59.3) | 373 992 (59.4) | 3569 (41.8) | 2140 (72.1) | 9042 (67.3) | 4383 (50.4) | 1271 (67.9) |

| Otherb | 38 309 (5.8) | 36 289 (5.8) | 624 (7.3) | 153 (5.2) | 561 (4.2) | 581 (6.7) | 101 (5.4) |

| No. of comorbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 343 226 (51.6) | 335 720 (53.4) | 3169 (37.1) | 1153 (38.8) | 3070 (22.8) | 64 (0.7) | 50 (2.7) |

| 1 | 153 533 (23.1) | 145 645 (23.1) | 2373 (27.8) | 788 (26.5) | 3399 (25.3) | 969 (11.2) | 359 (19.2) |

| 2 | 76 945 (11.6) | 70 343 (11.2) | 1361 (15.9) | 478 (16.1) | 2584 (19.2) | 1745 (20.1) | 434 (23.2) |

| ≥3 | 91 018 (13.7) | 77 503 (12.3) | 1633 (19.1) | 551 (18.6) | 4392 (32.7) | 5910 (68.0) | 1029 (55.0) |

| Full vaccination | 604 035 (90.9) | 573 122 (91.1) | 7526 (88.2) | 2667 (89.8) | 11 993 (89.2) | 7145 (82.2) | 1582 (84.5) |

| Vaccine manufacturerc | |||||||

| Pfizer BioNTech | 472 830 (71.1) | 447 940 (71.2) | 5279 (61.8) | 2276 (76.6) | 9525 (70.8) | 6410 (73.8) | 1400 (74.8) |

| Moderna | 160 535 (24.2) | 151 528 (24.1) | 2696 (31.6) | 565 (19.0) | 3392 (25.2) | 1941 (22.3) | 413 (22.1) |

| Johnson & Johnson/Janssen | 25 042 (3.8) | 23 685 (3.8) | 529 (6.2) | 103 (3.5) | 401 (3.0) | 271 (3.1) | 53 (2.8) |

| Otherd | 6315 (1.0) | 6058 (1.0) | 32 (0.4) | 26 (0.9) | 127 (0.9) | 66 (0.8) | <20e |

| Time of first vaccination | |||||||

| Dec 10, 2020, to Mar 1, 2021 | 249 648 (37.6) | 237 070 (37.7) | 2332 (27.3) | 934 (31.5) | 5866 (43.6) | 2860 (32.9) | 586 (31.3) |

| Mar 1 to Jun 19, 2021 | 360 693 (54.3) | 341 452 (54.3) | 5402 (63.3) | 1807 (60.8) | 6348 (47.2) | 4637 (53.4) | 1047 (55.9) |

| Jun 20 to Sep 16, 2021 | 54 381 (8.2) | 50 689 (8.1) | 802 (9.4) | 229 (7.7) | 1231 (9.2) | 1191 (13.7) | 239 (12.8) |

Abbreviations: BMT, bone marrow transplantation; MS, multiple sclerosis; N3C, National COVID Cohort Collaborative; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SOT, solid organ transplant.

Race and ethnicity were self-identified in the electronic medical record of the partner sites.

Other category included multiple, unknown, or self-reported other race and ethnicity.

Vaccine manufacturer was noted for the first dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine received in case of a 2-dose series.

Other manufacturers included AstraZeneca.

N3C policy requires all cells that contain fewer than 20 persons to be reported as <20.

Breakthrough Infection in the N3C Sample

Of the 604 035 fully vaccinated persons, 22 917 had a COVID-19 breakthrough infection (5.0 per 1000 person-months). Compared with partial vaccination, full vaccination was associated with a 28% reduced risk for a breakthrough infection (AIRR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68-0.76). Breakthrough infection rates were substantially higher after June 20, 2021, when the Delta variant became the dominant strain (IR before vs after June 20, 2021, 2.2 [95% CI, 2.2-2.2] vs 7.3 [95% CI, 7.3-7.4] per 1000 person-months; AIRR, 3.46; 95% CI, 3.23-3.72) (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. COVID-19 Breakthrough Infection Among Patients With Immune Dysfunction .

| Patient group | Pre–Delta variant period | Post–Delta variant period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total person-months | No. of breakthrough infection cases | Incidence rate per 1000 person-months (95% CI)a | Total person-months | No. of breakthrough infection cases | Incidence rate per 1000 person-months (95% CI)a | |

| Partial vaccination | ||||||

| Overall | 553 478 | 2165 | 2.9 (2.9-2.9) | 218 443 | 1562 | 9.6 (9.5-9.7) |

| No immune dysfunction | 524 821 | 2007 | 2.8 (2.8-2.9) | 205 139 | 1433 | 9.3 (9.2-9.4) |

| HIV infection | 7010 | 37 | 3.6 (3.6-3.7) | 3354 | 26 | 11.9 (11.4-12.4) |

| MS | 2418 | <20b | 3.5 (3.5-3.6) | 954 | <20b | 11.6 (10.8-12.4) |

| RA | 10 718 | 46 | 3.7 (3.7-3.8) | 4003 | 27 | 12.2 (11.8-12.6) |

| SOT | 7007 | 66 | 6.3 (6.2-6.4) | 4164 | 55 | 20.6 (19.4-21.8) |

| BMT | 1503 | <20b | 3.4 (3.3-3.5) | 829 | <20b | 11.2 (10.3-12.2) |

| Full vaccination | ||||||

| Overall | 1 501 418 | 2808 | 2.2 (2.2-2.2) | 2 162 800 | 16 382 | 7.3 (7.3-7.4) |

| No immune dysfunction | 1 423 568 | 2484 | 2.2 (2.2-2.2) | 2 053 050 | 15 255 | 7.1 (7.1-7.2) |

| HIV infection | 17 336 | 45 | 2.8 (2.8-2.8) | 26 844 | 250 | 9.1 (8.8-9.4) |

| MS | 6568 | <20b | 2.7 (2.7-2.8) | 9644 | 85 | 8.9 (8.4-9.3) |

| RA | 32 847 | 103 | 2.8 (2.8-2.9) | 43 044 | 408 | 9.3 (9.1-9.6) |

| SOT | 17 314 | 137 | 4.8 (4.7-4.9) | 24 647 | 343 | 15.7 (15.1-16.4) |

| BMT | 3786 | 21 | 2.6 (2.6-2.7) | 5581 | 41 | 8.6 (8.0-9.1) |

Abbreviations: BMT, bone marrow transplantation; MS, multiple sclerosis; N3C, National COVID Cohort Collaborative; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SOT, solid organ transplant.

Estimated incidence rate was based on unadjusted Poisson regression model.

N3C policy requires all cells that contain fewer than 20 persons to be reported as <20.

Table 3. Association of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics With COVID-19 Breakthrough Infectiona.

| Variable | AIRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1b | Model 2c | |

| Immune dysfunction group | ||

| No immune dysfunction | NA | 1 [Reference] |

| HIV infection | NA | 1.33 (1.18-1.49) |

| MS | NA | 1.12 (0.93-1.35) |

| RA | NA | 1.20 (1.09-1.32) |

| SOT | NA | 2.16 (1.96-2.38) |

| BMT | NA | 1.09 (0.85-1.40) |

| Vaccination | ||

| Partial | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Full | 0.71 (0.67-0.76) | 0.72 (0.68-0.76) |

| Period after June 20, 2021d | 3.46 (3.23-3.72) | 3.46 (3.23-3.70) |

| COVID-19 diagnosis before vaccination | 0.46 (0.42-0.51) | 0.44 (0.40-0.48) |

| Geographic region | ||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest | 0.97 (0.85-1.12) | 0.98 (0.86-1.12) |

| West | 1.27 (1.13-1.42) | 1.28 (1.15-1.42) |

| South | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) | 1.22 (1.08-1.36) |

| Age group, y | ||

| <18 | 0.78 (0.69-0.87) | 0.78 (0.70-0.88) |

| 18-29 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 30-49 | 1.40 (1.27-1.54) | 1.39 (1.26-1.53) |

| 50-64 | 1.32 (1.21-1.43) | 1.31 (1.20-1.42) |

| ≥65 | 1.38 (1.25-1.52) | 1.40 (1.27-1.53) |

| Female sex | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Male sex | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) | 0.95 (0.89-1.00) |

| Race and ethnicitye | ||

| AAPI | 0.81 (0.73-0.89) | 0.81 (0.73-0.89) |

| Hispanic | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) |

| Non-Hispanic | ||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.75 (0.69-0.81) | 0.75 (0.69-0.80) |

| Otherf | 0.92 (0.85-0.99) | 0.91 (0.84-0.98) |

| No. of comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 1.04 (0.97-1.13) | 1.03 (0.96-1.11) |

| 2 | 1.09 (1.00-1.19) | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) |

| ≥3 | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 1.02 (0.85-1.12) |

Abbreviations: AAPI, Asian American/Pacific Islander; AIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; MS, multiple sclerosis; NA, not applicable; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SOT, solid organ transplant.

Breakthrough infection was defined as a COVID-19 infection that was contracted on or after the 14th day of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Estimated with multivariable Poisson regression, adjusting for a study period (pre– or post–Delta variant period, after Delta became the primary strain of SARS-CoV-2 in the US); full vaccination status; COVID-19 infection before vaccination; age, sex, and race and ethnicity; comorbid conditions (0, 1, 2, ≥3); and geographic region of study site.

Calculated with multivariable Poisson regression, adjusting for covariates in model 1 and immune dysfunction group.

Period was defined on the first day the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the Delta variant accounted for more than 50% of the COVID-19 cases in the US.

Race and ethnicity were self-identified in the electronic medical record of the partner sites.

Other category included multiple, unknown, or self-reported other race and ethnicity.

Older age, female sex, and a higher number of comorbidities were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of breakthrough infection. Specifically, risk for breakthrough infection increased by 30% to 40% among patients 30 years or older compared with those aged 18 to 29 years. Although risk for a breakthrough infection increased with greater number of comorbidities, this risk was associated with and notably attenuated by immune dysfunction status (Table 3, model 1 vs model 2).

Breakthrough Infection in People With Immune Dysfunction

Compared with people without immune dysfunction (Table 2 and Table 3), those with immune dysfunction had a higher rate of breakthrough infection after receiving partial or full vaccination. The difference is more noticeable in the period after the Delta variant became dominant (Table 2). Specifically, among individuals with full vaccination, the IR of breakthrough infection was 7.1 (95% CI, 7.1-7.2) per 1000 person-months for people without immune dysfunction vs 9.1 (95% CI, 8.8-9.4) per 1000 person-months for HIV infection, 8.9 (95% CI, 8.4-9.3) per 1000 person-months for MS, 9.3 (95% CI, 9.1-9.6) per 1000 person-months for RA, 15.7 (95% CI, 15.1-16.4) per 1000 person-months for SOT, and 8.6 (95% CI, 8.0-9.1) per 1000 person-months for BMT. Furthermore, HIV infection (AIRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.18-1.49), RA (AIRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.09-1.32), and SOT (AIRR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.96-2.38) were independently associated with increased breakthrough infection rate (Table 3). Individuals with vs without prevaccination COVID-19 diagnosis had a 56% reduced risk for a breakthrough infection (AIRR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.40-0.48). All associations were independent of demographic characteristics, geographic region, and comorbidity burden. Overall, sensitivity analyses that evaluated no 14-day lag period, excluded cancer and other rheumatic diseases, and excluded previous COVID-19 diagnosis yielded results similar to those in primary analyses (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

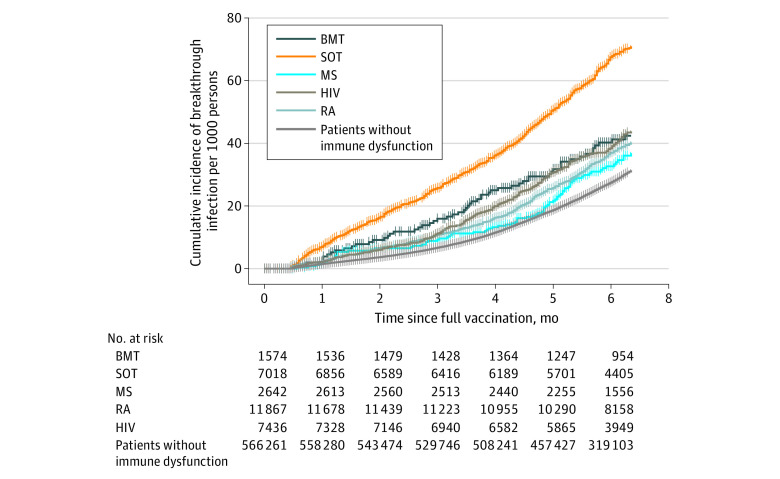

The median (IQR) time from full vaccination to breakthrough infection was 138 (85-178) days. Overall, 1.2% of patients had a breakthrough infection in 3 months and 2.8% contracted it in 6 months after completing vaccination. Compared with patients without immune dysfunction, patients with immune dysfunction conditions, especially patients with HIV infection or recipients of SOT or BMT, had substantially faster time to breakthrough infection (Figure 1; eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Specifically, more than 6% of SOT recipients contracted a breakthrough infection in 6 months. More than 50% of the breakthrough infections among patients with HIV infection or recipients of BMT or SOT occurred within the first 4 months of full vaccination.

Figure 1. Time to COVID-19 Breakthrough Infection by Immune Dysfunction Condition .

All breakthrough infections that occurred from 0 to 14 days after full SARS-CoV-2 vaccination were excluded. BMT indicates bone marrow transplantation; MS, multiple sclerosis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; and SOT, solid organ transplant.

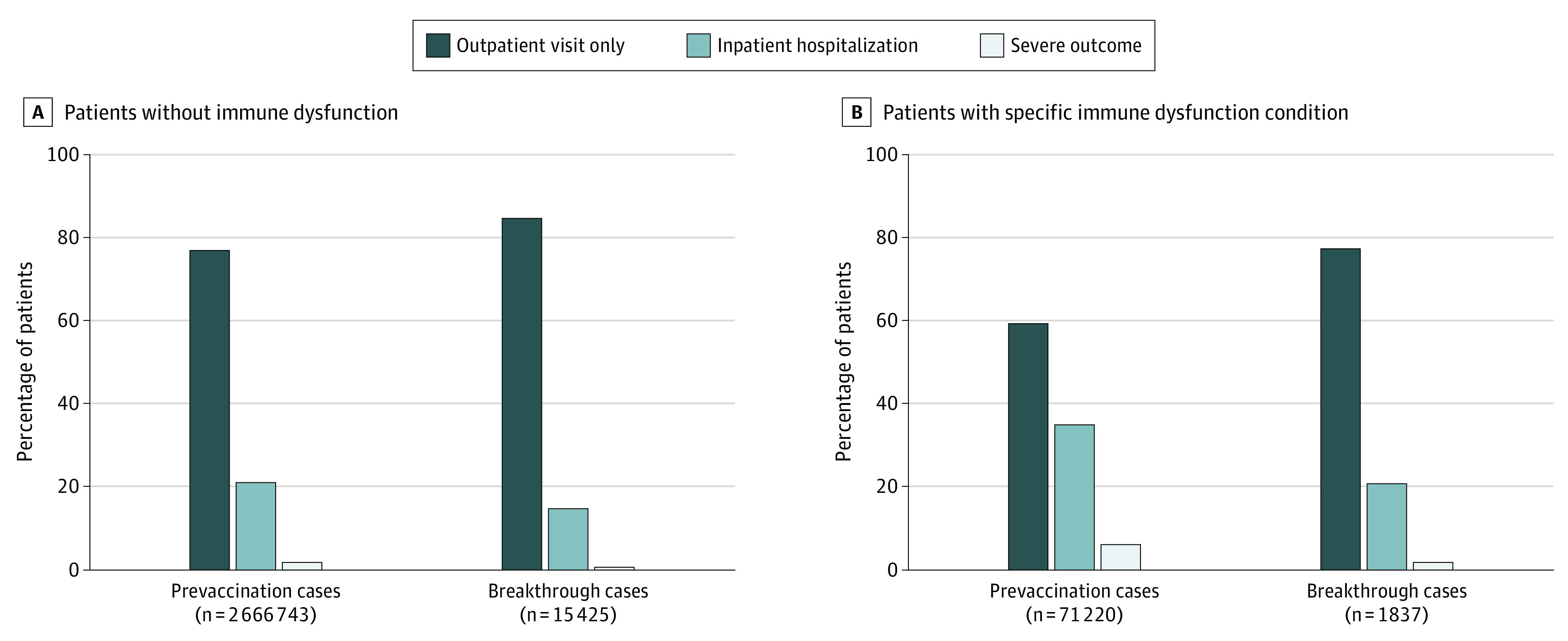

Compared with the 2 111 515 prevaccination COVID-19 cases in the N3C sample, COVID-19 outcomes within 45 days of diagnosis were less severe for the breakthrough infection cases (Figure 2). Among COVID-19 cases without immune dysfunction, the proportions with inpatient hospitalization and severe outcomes were lower among breakthrough cases compared with prevaccination cases (16.0% vs 24.4%). Patients with immune dysfunction had higher levels of severity but also experienced a notable decline in severity, especially those with severe outcomes from prevaccination to breakthrough infection (6.3% [n = 4486 of 71 365] vs 3.3% [n = 50 of 1538]).

Figure 2. COVID-19 Disease Severity in Prevaccination vs Breakthrough Infection Cases.

Prevaccination cases were defined as those with a COVID-19 diagnosis before the first dose of a vaccine. Breakthrough infection cases were defined as those who contracted a COVID-19 infection on or after the 14th day of vaccination. Disease severity was assigned as the highest level of health care utilization within 45 days of breakthrough infection. Severe outcomes included inpatient hospitalization with invasive ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death. Data are given in eTable 4 in Supplement 1.

Discussion

Leveraging real-world data from 664 722 persons who were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in the US, we observed that COVID-19 breakthrough infection occurred infrequently after full vaccination but was notably more common than the CDC surveillance estimates.9 We believe the findings confirm that individuals with varied immune dysfunction conditions had higher breakthrough infection rate. Although the breakthrough infection rate tripled after the emergence of the Delta variant, breakthrough cases tended to be substantially less severe compared with prevaccination COVID-19 cases, regardless of a person’s immune status. In addition, we believe that the data confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations have been highly successful and emphasized the importance of full vaccination for preventing breakthrough infection. This benefit is apparent, regardless of immune status, although intact immune function is associated with maximum protection.

Persons living with HIV or undergoing immunosuppressant treatment (patients with RA and SOT recipients) had a significantly higher risk for breakthrough infection, independent of older age, female sex, and comorbidity burden. Breakthrough infection occurred substantially faster among persons with immune dysfunction compared with the general population. Although the risk estimates for MS and BMT groups were not statistically significant in the Poisson regression in part because of the limited sample size, the IRs and time-to-event analysis demonstrated their potential higher risk for a breakthrough infection compared with people without immune dysfunction. In addition, patients with severe immune dysfunction (ie, recipients of BMT) may continue nonpharmaceutical prevention strategies, regardless of vaccination status, and thus reduce their risk for contracting a breakthrough infection.

Although patients with immune dysfunction had substantially less severe COVID-19 outcomes after vaccination compared with cases before vaccination, the disease severity of breakthrough infection cases was still noticeable (3.3% with severe outcomes). The finding that a higher likelihood and greater severity of a breakthrough infection were observed among persons with immune dysfunction prompts the consideration of alternative prevention and management approaches in this population.

We observed a higher breakthrough infection rate compared with the reported CDC surveillance data to date (estimated at 2.8% by 6 months after full vaccination vs 22 115 cases after 183 million vaccinations).10 Surveillance data from the CDC originated from the existing state health department reporting systems, identified primarily symptomatic cases, and almost certainly underestimated the true rate of breakthrough infection. In contrast, because the N3C population originated from predominantly academic medical centers and consisted of individuals either with or without previous COVID-19 diagnosis, persons at a higher risk for incident COVID-19 were likely overrepresented in this sample compared with the general US population. For instance, the study population consisted of older patients with many comorbidities and higher prevalence of immune dysfunction (5.3% in this study vs 2.7% in US adults32), which are factors associated with a higher susceptibility to a breakthrough infection in both the present and previous studies.5,7,8 Given the routine COVID-19 screening at hospitals for admissions or procedures, the N3C data may have captured more asymptomatic cases compared with the CDC surveillance data. Nonetheless, the observed prevalence in this study is comparable to the population-level data from the United Kingdom,33 in which the breakthrough infection rates after full vaccination against the Alpha and Delta variants were approximately 6 and 14 per 1000 persons, respectively. Although we were not able to directly identify specific variants in the current data, we were able to classify IRs before and after the Delta variant became the dominant strain. Although the true rate of breakthrough infection in the US remains difficult to estimate, the results of this study are reassuring regarding the relative infrequency of severe breakthrough infection among persons without immune dysfunction.

These findings are consistent with results of 2 studies from Israel and US, which corroborated that persons with immune dysfunction had substantially higher risk for a breakthrough infection compared with persons without immune dysfunction.7,8 A US case-control study of 1210 hospitalized patients suggested that 44% of hospitalized breakthrough cases occurred among immunocompromised patients, estimating that the vaccine was less effective at 59.2% within this group.7 We further addressed the excessive risk for a breakthrough infection among patients with specific immune dysfunction conditions in this large national sample. Although we observed that breakthrough infection rates were higher in persons with immune dysfunction, the severity of a breakthrough infection was reduced, underscoring that vaccination, although not as immunologically beneficial in this population, had considerable advantages.

A previous immunogenicity study suggested that the seropositivity rates of antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein after vaccination among patients with immune dysfunction were substantially lower than the rates in healthy control patients (37.2%-83.8% of seropositivity among patients with immune dysfunction vs 98.1% among healthy adults).18 Persons living with HIV showed a comparable immune response to healthy adults in this immunogenicity study,18 although the sample size was small (n = 37 persons with HIV) and their status of immune dysfunction (ie, CD 4 cell counts) was unclear. The large-scale real-world data we used confirmed that multiple groups of persons with immune dysfunction (SOT, RA, and HIV infection) displayed substantially higher rates for a breakthrough infection. This study included 8536 persons with HIV and showed that they had an independent 33% higher risk for a breakthrough infection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. A recent study reported an increased risk for severe COVID-19 infection in persons living with HIV that was associated with more advanced immune deficiency.11 Persons living with HIV, especially those with advanced immune deficiency, should be considered at a higher risk, comparable to other patients with immune dysfunction, in guidelines to prevent a COVID-19 breakthrough infection.

We believe the findings provide robust evidence to support the CDC recommendation of a booster vaccine dose in persons with immune dysfunction. Recent studies indicated that patients who underwent SOT experienced weak immune responses to 2-dose SARS-CoV-2 vaccines,21,22 but 3 doses of an mRNA vaccine may improve immunogenicity.20,34 Specifically, the detection of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies increased from 40% to 68% after the third dose of an mRNA vaccine in patients who underwent SOT.20 Although a third dose considerably improved the immune response among SOT recipients, the prevalence of antibody response was still substantially lower in that study than in the general population (<70% vs >90%, respectively).20 Severe immunodeficiency in some patients may preclude the appropriate antibody response regardless of the number of vaccine doses given.

The findings of this study suggest that nuanced guidance for COVID-19 prevention and control is needed for patients with immune dysfunction. Clinicians and patients should consider continuing nonpharmaceutical interventions even after vaccination, including mask wearing, social distancing, and avoiding densely crowded settings (especially indoors) as much as possible. For patients with immune dysfunction who contracted or were exposed to COVID-19 infection after vaccination, future studies can investigate the benefits of postexposure prophylaxis or preemptive therapy, close monitoring for early disease progression, and permissive use of additional therapies while evaluating the duration of viral shedding or potential for onward transmission. Although antibody levels may not always indicate vaccine protection, further immunogenic studies to identify protective thresholds of antibody response may aid in triaging patients with immune dysfunction who are at greatest risk for a breakthrough infection.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is limited by the nature of using EMR-based data, which could potentially lead to misclassified immune dysfunction and comorbid conditions, although we anticipate this misclassification to be nondifferential. Second, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status was captured in the EMR of large academic medical centers, which may not fully account for vaccinations that occur outside of their hospital settings, such as pharmacies and mass vaccination sites. However, this underreporting is less likely to affect patients with immune dysfunction because they are more likely to receive regular care, and would not alter the comparisons of risk. Third, we did not evaluate the risk for a breakthrough infection among patients with other immune dysfunctions, such as cancer and other rheumatoid diseases, nor did we directly evaluate exposure to immunosuppressant regimens. However, the sensitivity analysis we performed that excluded patients with cancer and other rheumatoid diseases yielded consistent results with the primary analyses.

Conclusions

This cohort study provided real-world evidence that patients with immune dysfunction had substantially higher risk for contracting COVID-19 breakthrough infection and had worse outcomes compared with those without immune dysfunction. Completion of all recommended doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is crucial in preventing a breakthrough infection regardless of a person’s immune status. The findings support the use of alternative vaccine strategies (eg, additional doses or immunogenicity testing) and nonpharmaceutical interventions (eg, mask wearing) even after full vaccination for people with immune dysfunction.

eFigure 1. Analytical Sample Selection Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. Geographic Region for Study Population in N3C, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 1. Key Variables and Concept Definitions

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses for SARS-CoV-2 Infection After Vaccination Among N3C Cohort, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 3. Time to SARS-CoV-2 Post-Vaccine Breakthrough Infection Among Patients Completed All Required Dose of Vaccination by Immune Dysfunction Group in N3C Cohort, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 4. COVID-19 Disease Severity Comparing Cases Prior to Vaccination Versus Breakthrough Infection Cases Identified in N3C Cohort

eMethods 1. N3C Methods

eMethods 2. Example of How a Source Vocabulary Term Is Mapped to a OMOP Concept Set

eMethods 3. List of 56 Data Partners Whose Data Is Available in the N3C Enclave

eMethods 4. Distribution of Patients Contributed by Each Submitting Institution for Each Cohort

eMethods 5. Distribution of Patients Contributed by Each Institution Broken Down by A) Vaccination Status of at Least One Dose and B) COVID-19 Diagnosis

eReferences

eAppendix. Additional Data Partners With Signed DTA and Pending Data Release

Nonauthor Collaborators. National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Consortium

References

- 1.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr, Falsey AR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2439-2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Jabal K, Ben-Amram H, Beiruti K, et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(6):2100096. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.6.2100096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1819-1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butt AA, Omer SB, Yan P, Shaikh OS, Mayr FB. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness in a high-risk national population in a real-world setting. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(10):1404-1408. doi: 10.7326/M21-1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenforde MW, Patel MM, Ginde AA, et al. ; Influenza and Other Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network . Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines for preventing Covid-19 hospitalizations in the United States. medRxiv. Preprint posted online July 8, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.07.08.21259776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brosh-Nissimov T, Orenbuch-Harroch E, Chowers M, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine breakthrough: clinical characteristics of 152 fully vaccinated hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Israel. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(11):1652-1657. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections reported to CDC–United States, January 1-April 30, 2021. Accessed May 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7021e3.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough case investigation and reporting. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html

- 11.Sun J, Patel RC, Zheng Q, et al. ; National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Consortium . COVID-19 disease severity among people with HIV infection or solid organ transplant in the United States: a nationally-representative, multicenter, observational cohort study. medRxiv. Preprint posted online July 28, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.07.26.21261028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolini LA, Magne F, Signori A, et al. Hepatitis B virus vaccination in HIV: immunogenicity and persistence of seroprotection up to 7 years following a primary immunization course. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(11):922-928. doi: 10.1089/aid.2017.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abzug MJ, Warshaw M, Rosenblatt HM, et al. ; International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1024 and P1061s Protocol Teams . Immunogenicity and immunologic memory after hepatitis B virus booster vaccination in HIV-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(6):935-946. doi: 10.1086/605448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckerle I, Rosenberger KD, Zwahlen M, Junghanss T. Serologic vaccination response after solid organ transplantation: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangappa S, Kokko KE, Carlson LM, et al. Immune responsiveness and protective immunity after transplantation. Transpl Int. 2008;21(4):293-303. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhodapkar MV, Dhodapkar KM, Ahmed R. Viral immunity and vaccines in hematologic malignancies: implications for COVID-19. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2(1):9-12. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-20-0177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rozans MK, Smith BR, Burakoff SJ, Miller RA. Long-lasting deficit of functional T cell precursors in human bone marrow transplant recipients revealed by limiting dilution methods. J Immunol. 1986;136(11):4040-4048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haidar G, Agha M, Lukanski A, et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccination in immunocompromised patients: an observational, prospective cohort study interim analysis. medRxiv. Preprint posted online June 30, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21259576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertrand D, Hamzaoui M, Lemée V, et al. Antibody and T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2147-2152. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021040480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Izopet J, Del Bello A. Three doses of an mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):661-662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, et al. Antibody response to 2-dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325(21):2204-2206. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marion O, Del Bello A, Abravanel F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of anti-SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccines in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(9):1336-1338. doi: 10.7326/M21-1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgery H, Devresse A, Yombi J-C, et al. Very low immunization rate in kidney transplant recipients after one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine: beware not to lower the guard! Transplantation. 2021;105(10):e148-e149. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, et al. ; N3C Consortium . The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):427-443. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, et al. ; National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Consortium . Clinical characterization and prediction of clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection among US adults using data from the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116901. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Browne SK, Beeler JA, Roberts JN. Summary of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee meeting held to consider evaluation of vaccine candidates for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease in RSV-naïve infants. Vaccine. 2020;38(2):101-106. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker: monitoring variant proportions. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

- 29.GitHub. National COVID Cohort Collaborative Phenotype Data Acquisition . Accessed September 30, 2021. https://github.com/National-COVID-Cohort-Collaborative/Phenotype_Data_Acquisition

- 30.Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, et al. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative: clinical characterization and early severity prediction. medRxiv. Preprint posted online January 23, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.12.21249511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall JC, Murthy S, Diaz J, et al. ; WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection . A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):e192-e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harpaz R, Dahl RM, Dooling KL. Prevalence of immunosuppression among US adults, 2013. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2547-2548. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 variant. medRxiv. Preprint posted online May 24, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.22.21257658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werbel WA, Boyarsky BJ, Ou MT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(9):1330-1332. doi: 10.7326/L21-0282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Analytical Sample Selection Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. Geographic Region for Study Population in N3C, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 1. Key Variables and Concept Definitions

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses for SARS-CoV-2 Infection After Vaccination Among N3C Cohort, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 3. Time to SARS-CoV-2 Post-Vaccine Breakthrough Infection Among Patients Completed All Required Dose of Vaccination by Immune Dysfunction Group in N3C Cohort, December 10, 2020 to September 24, 2021

eTable 4. COVID-19 Disease Severity Comparing Cases Prior to Vaccination Versus Breakthrough Infection Cases Identified in N3C Cohort

eMethods 1. N3C Methods

eMethods 2. Example of How a Source Vocabulary Term Is Mapped to a OMOP Concept Set

eMethods 3. List of 56 Data Partners Whose Data Is Available in the N3C Enclave

eMethods 4. Distribution of Patients Contributed by Each Submitting Institution for Each Cohort

eMethods 5. Distribution of Patients Contributed by Each Institution Broken Down by A) Vaccination Status of at Least One Dose and B) COVID-19 Diagnosis

eReferences

eAppendix. Additional Data Partners With Signed DTA and Pending Data Release

Nonauthor Collaborators. National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Consortium