Abstract

One of the most prominent NF-κB target genes in mammalian cells is the gene encoding one of its inhibitor proteins, IκBα. The increased synthesis of IκBα leads to postinduction repression of nuclear NF-κB activity. However, it is unknown why IκBα, among multiple IκB family members, is involved in this process and what significance this feedback regulation has beyond terminating NF-κB activity. Herein, we report an important IκBα-specific function dictated by its amino-terminal nuclear export sequence (N-NES). The IκBα N-NES is necessary for the postinduction export of nuclear NF-κB, which is a critical event in reestablishing a permissive condition for NF-κB to be rapidly reactivated. We show that although IκBα and another IκB member, IκBβ, can enter the nucleus and repress NF-κB DNA-binding activity during the postinduction phase, only IκBα allows the efficient export of nuclear NF-κB. Moreover, swapping the N-terminal region of IκBβ for the corresponding IκBα sequence is sufficient for the IκB chimera protein to export NF-κB similarly to IκBα during the postinduction state. Our findings provide a mechanistic explanation of why IκBα but not other IκB members is crucial for postrepression activation of NF-κB. We propose that this IκBα-specific function is important for certain physiological and pathological conditions where NF-κB needs to be rapidly reactivated.

The NF-κB/Rel family of inducible transcription factors is involved in the expression of numerous genes involved in important cellular and physiological processes such as growth, development, apoptosis, and inflammatory and immune responses (15, 45). Members of the Rel family include p65 (RelA), p105/p50, p100/p52, RelB, and c-Rel. These transcription factors can form homo- or heterodimers with each other to make transcriptionally competent or repressive complexes, loosely referred to as the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). The biological activity of NF-κB is tightly regulated by its inhibitor protein, IκB. Members of the IκB family include IκBβ, IκBγ, IκBɛ, Bcl-3, and the best-characterized member, IκBα (15). In most cells, IκBα and IκBβ are found associated with the p50-p65 heterodimer, the most ubiquitous NF-κB, to form a stable trimeric complex inside the cell.

The subcellular localization of NF-κB–IκB complexes dictates the ability of NF-κB to be activated by extracellular stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). We and others have previously shown that cytoplasmic localization of preinduced NF-κB–IκB complexes is important for efficient cytokine-dependent phosphorylation-ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of IκB proteins, which cause the release of NF-κB to the nucleus to alter gene expression (17, 38). Nuclear NF-κB–IκB complexes, however, are generally refractory to cytokine-induced IκB degradation. These observations suggest that cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB–IκB complexes plays an important role during the pre- and postinduced stages of NF-κB activation.

Localization of preinduced NF-κB population is partly controlled by an N-terminal nuclear export signal (N-NES) on IκBα (17, 23, 38, 43). NF-κB complexes formed with IκBα have a tendency to shuttle rapidly between the cytoplasm and nucleus, likely due to leaky exposure of p50 nuclear localization signal (NLS) coupled to a more dominant nuclear export by IκBα (17, 22). However, it is unknown whether IκBβ or other IκB members bound to NF-κB can also shuttle nucleocytoplasmically in the absence of stimuli.

The localization of postinduced nuclear NF-κB population is also carefully controlled, presumably by IκBα (1, 47). Postinduction repression refers to the condition in which activated nuclear NF-κB upregulates the expression of IκBα due to NF-κB consensus binding sites within the IκBα promoter (7, 8, 21, 27, 42), followed by nuclear accumulation of free IκBα, which dissociates NF-κB from NF-κB-bound DNA complexes to repress NF-κB function (2). These newly formed nuclear NF-κB–IκBα complexes are then exported out to the cytoplasm, thereby reestablishing the cytoplasmic pool of inactive NF-κB complexes that are primed for another round of activation to take place (2). Recent reports have shown intrinsic nuclear export functions in both IκBα (2, 17, 23, 38, 39, 43) and the p65 subunit of NF-κB complexes (16). However, it remains to be determined which of these newly characterized NESs can facilitate postinduction export of nuclear NF-κB complexes.

The leucine-rich NES motif is an evolutionarily conserved sequence used by a variety of proteins to facilitate their delivery from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and is also used as an important point of control by the cell to regulate protein function through subcellular localization (24, 28). Leptomycin B (LMB) is an extremely useful tool used to selectively inhibit Crm1 (exportin-1)-dependent nuclear export of NES-containing proteins (10, 11, 26, 35, 41). LMB appears to covalently modify Crm1 export receptor at a conserved cysteine residue that renders the receptor incapable of forming the exporting trimeric complex between cargo protein and RanGTP (25).

In the present study, we provide evidence that IκBα may be the only NF-κB inhibitor protein to possess an intrinsic nuclear export function. We employed LMB, knockout cells, chimeric constructs, and transient and stable transfection studies to monitor subcellular localization of NF-κB–IκB complexes, degradation of IκB proteins, and NF-κB DNA-binding activities during pre-and postinduction states. We found that N-NES of IκBα is primarily responsible for export of NF-κB during pre- and postinduction states. However, NF-κB–IκBβ complexes are incapable of shuttling during both of these states, suggesting that, unlike IκBα, IκBβ is capable of completely masking nuclear localization sequences of the NF-κB dimer and incapable of exporting the complex out of the nucleus. Swapping the N-terminal region of IκBβ for IκBα sequence allows NF-κB bound to the chimeric protein to be exported out of the nucleus in a manner identical to IκBα. These results provide deeper insights into the fundamental differences between regulatory mechanisms governing function of IκBα and IκBβ and possibly other IκB members and implicate biological relevance of IκBα-specific nuclear export function in regulation of such processes as apoptosis and inflammatory responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), 293 human embryonic kidney cells (HEK), and Cos-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratory, Inc.), 1,000 U of penicillin G (Sigma Chem. Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and 0.5 mg of streptomycin sulfate (Sigma) per ml in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator (Forma Scientific). The p65−/− 3T3 cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% bovine calf serum and supplemented with antibiotics as above. Cells (embryonic fibroblasts and Cos-7) were transiently transfected using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) and the standard calcium phosphate precipitation method (5).

Reagents.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma. MG132 was purchased from Peptides International. Human recombinant TNF-α was from CalBiochem and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (fraction V; Sigma). In each experiment, all samples received the same amounts of DMSO to control for potential DMSO effects. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against IκBα (C21), IκBβ (C20), and p65 (C20) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The 5432 rabbit polyclonal antibody was raised against the N-terminal 56 amino acids of murine IκBα conjugated to glutathione S-transferase as described previously (30). A monoclonal anti-HA.11 (influenza virus hemagglutinin epitope) antibody was purchased from BabCO, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse Ig antibodies were obtained from Amersham. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- and tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse Ig antibodies were purchased from Sigma. Hoechst dye 33342 and rhodamine phalloidin (R-415) were purchased from Molecular Probes.

Western blot and EMSA procedures.

Cell preparation and Western immunoblots were performed as described (31) and developed using the enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) procedure according to the manufacturer (Amersham). Blots were then exposed to X-ray film (Kodak). The Igκ-κB oligonucleotide probe and conditions for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were previously described (31). The total cell extract buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 350 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and aprotinin) was used for both Western blot analysis and EMSA. Nuclear and cytoplasmic biochemical fractionations were accomplished using buffer C and buffer A, respectively, as described (31).

Construction of IκBα, IκBβ and p65 chimeras and fusion proteins.

N-terminally fused green fluorescent protein (GFP)-IκBα was generated by subcloning PCR-amplified human wild-type IκBα (MAD3) into the HindIII and BamHI sites of the pEGFP vector (Clontech). The human p65 cDNA was kindly provided by D. Ballard (Vanderbilt, Tenn.). To make the GFP N-terminally tagged p65 fusion protein, the p65 cDNA with HindIII and BamHI flanking sites was created by PCR and ligated in-frame into the pEGFP vector (Clontech). Truncated p65s (amino acids [aa] 1 to 420 and 1 to 450) were made with 3′ primers specific to the C-terminal truncated portion of p65 and subcloned into the pEGFP vector as above. The murine p65 cDNA was blunt-end ligated into BamHI-NheI Klenow blunt-ended pCMX vector (provided by K. Umesono, Kyoto University). Similarly, CMX-p50 was generated by cleaving murine p105 cDNA at NcoI sites, Klenow filled, and blunt-ligated into BamHI-NheI Klenow blunt-ended pCMX vector. IκBβ expression vector was constructed by inserting murine IκBβ cDNA into pcDNA vector (Clontech). The amount of each plasmid vector was titrated to ensure the formation of IκBα and NF-κB complexes in Cos-7 cells and MEFs. The IκBαββ construct (pLHL-CA-IκBαββ) was made by using specific primer sets with either 3′ IκBα or 5′ IκBβ overhangs to PCR amplify pBS-IκBα (1 to 66) and pBS-IκBβ (45 to 359). The two PCR products were joined by PCR using 5′ IκBα and 3′ IκBβ-specific primers, subcloned into pBS at 5′ BamHI and 3′ XhoI, and subcloned into pLHL-CA vector at 5′ BamHI-BglII and 3′ XhoI sites. The N-NES mutant IκBαββ construct was constructed similarly to the IκBαββ construct except that the pBS-IκBα N-NES mutant construct was used as a template. The pBS-IκBα N-NES mutant template was generated using two-step PCR mutagenesis as described (17). The hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged murine IκBα gene (pLHL-CAHA-mIκBα) was constructed as described previously (31).

Visual analysis of NF-κB and IκBα proteins.

MEFs and Cos-7 cell lines were cultured in two-or four-welled chamber slides (Lab-Tek) and transiently transfected with various expression plasmid constructs. After drug treatment, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for several hours at 4°C. Fixed cells were then rinsed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were blocked with 2% normal goat serum for 1 h and subsequently incubated with appropriate primary antibodies in PBS–0.2% Tween 20–2% goat serum at 37°C overnight. Staining was detected with either FITC- or TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse or -rabbit Ig secondary antibodies. Cells were mounted with Prolong Antifade (Molecular Probes) and visualized and photographed using a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope with the aid of fluorescein- or rhodamine-specific filters. GFP fusion protein was visualized directly in living cells or under fixed conditions.

Generation of stable pools of MEFs.

MEFs deficient for IκBα were reconstituted with either HA-tagged murine IκBα or the chimeric IκBαββ gene via retroviral infection as described previously (31). Briefly, pLHL-CAHA-mIκBα or pLHL-CA-IκBαββ and pLHL-CA-IκBαββ N-NESmut constructs were contransfected with pCLeco (32) helper virus in HEK 293 cells. Viruses were then harvested and transferred onto MEFs for infection. Stably infected pools of MEFs were selected in the presence of hygromycin. The stable pools of MEFs were then grown in the absence of hygromycin for 2 days before experiments were initiated.

RESULTS

LMB cannot inhibit activation of NF-κB associated with IκBβ.

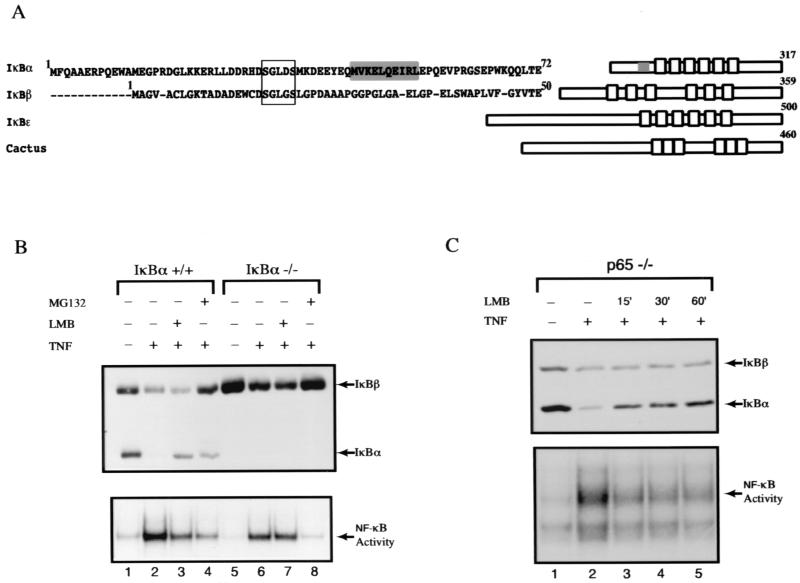

It is known that nuclear export of NF-κB can be mediated by the IκBα protein. It is yet unclear whether the capacity to export NF-κB out of the nucleus is a general function of all IκB family members. Scanning the primary amino acid sequences of other IκB members, such as IκBβ (44), p105/IκBγ (14, 20, 37), p100 (29, 33), IκBɛ (46), and Bcl-3 (34), or cactus (13), the Drosophila homolog of IκB, revealed no conserved NES motifs N-terminal of the first ankyrin repeat compared to IκBα (Fig. 1A; others not shown). Since IκBβ is widely expressed and responds to stimulus-dependent degradation in a manner similar to IκBα, we chose to compare and contrast the mechanistic differences in the ability of IκBα and IκBβ to modulate NF-κB localization and activation. Consistent with earlier reports (17, 38), TNF-α-induced NF-κB DNA-binding activity was inhibited by LMB (Fig. 1B, lower panel, lanes 2 and 3). However, surprisingly, LMB had no observable effect against TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in IκBα knockout cells (Fig. 1B, lower panel, lanes 6 and 7). Although TNF-α induced the degradation of both IκBα and IκBβ in the wild-type cells, LMB selectively retarded the degradation of IκBα, not IκBβ (Fig. 1B, upper panel, lanes 2 and 3). Likewise, IκBβ was degraded by TNF-α stimulation but was not inhibited upon pretreatment with LMB in the IκBα-deficient cells (Fig. 1B, upper panel, lanes 6 and 7). These results show that LMB inhibits NF-κB activation only through the IκBα protein. Together with a recent finding of the presence of a functional NES on p65 but not on the p50 or c-Rel subunit of NF-κB (16), our data suggest that the p65 NES does not dominantly affect IκBβ subcellular localization in an LMB-sensitive fashion. Alternatively, unlike IκBα, IκBβ completely masks both nuclear localization sequences present on dimeric NF-κB complexes, thereby preventing import of NF-κB in the uninduced state. In the latter case, NF-κB–IκBβ complexes do not shuttle in an NES-dependent manner, making their subcellular localization LMB insensitive.

FIG. 1.

IκBβ is refractory to LMB inhibition of TNF-α-induced degradation. (A) N-terminal primary amino acid sequence alignment of IκBα and IκBβ. Boxed region signifies the highly conserved IκB kinase phosphorylation sites on the dual serines on IκBα and IκBβ. Highlighted sequences (shaded box) are the recently identified “leucine-rich” N-terminal NES of IκBα that is not conserved in other IκB proteins such as IκBβ, IκBɛ, and cactus. (B) Wild-type and IκBα-deficient MEFs were untreated or treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 15 min; lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8) in the presence or absence of LMB (20 ng/ml; lanes 3 and 7) or MG132 (30 μM; lanes 4 and 8) pretreatment for 30 min. Total cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA by using an Igκ-κB probe (lower panel) and by Western blotting with IκBα (C-21) and IκBβ (C-20) antibodies (upper panel). (C) p65-deficient 3T3 cells were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 15 min; lanes 2 to 5) and pretreated in the presence or absence of LMB (20 ng/ml) for 15, 30, or 60 min (lanes 3, 4, and 5, respectively). Total cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA as described above (lower panel) and by Western blotting with IκBα- and IκBβ-specific antibodies (upper panel).

However, in the case of NF-κB associated with IκBα, it is unclear which of the NES motifs present on p65 and IκBα plays a dominant role in the shuttling of NF-κB–IκBα complexes during the preinduced state. Using p65-deficient cells, we sought to determine whether NF-κB–IκBα complexes are sensitive to LMB-induced nuclear localization in the absence of the p65 subunit. As in wild-type cells, TNF-α still targeted the degradation of both IκBα and IκBβ and induced the appearance of NF-κB (primarily p50 and c-Rel [4]) binding activity in p65 knockout cells (Fig. 1C, lower panel, lanes 1 and 2). As in wild-type cells, LMB still inhibited the degradation of IκBα (Fig. 1C, upper panel, lanes 3 to 5). Coupled with our earlier observation that disruption of IκBα N-NES sequence causes nuclear accumulation of associated NF-κB complexes (17), our results demonstrate that IκBα is the primary target of LMB action. These observations together demonstrate that during the preinduced state, the NF-κB–IκBα complexes still shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus even in the absence of the p65 NES.

IκBβ is insensitive to LMB-induced nuclear accumulation in preinduction state.

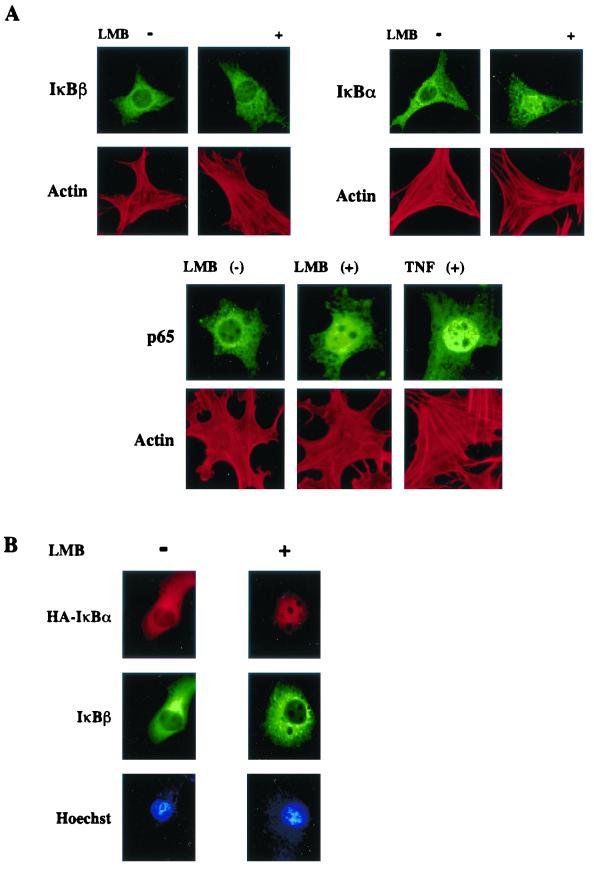

The above data suggest that NF-κB–IκBβ complexes do not shuttle in an LMB-sensitive fashion, unlike those containing IκBα. To directly determine whether the subcellular localization of preinduced IκBβ is not affected by LMB, endogenous IκBβ was stained with IκBβ-specific antibodies and visualized under a fluorescent microscope. As an internal control, IκBα subcellular localization was similarly monitored. In untreated MEFs, both IκBβ and IκBα were localized predominantly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A, upper left panels). Upon treatment of the cells with LMB, IκBα accumulated in the nucleus, as expected (Fig. 2A, upper right panels). In contrast, the localization of IκBβ remained cytoplasmic. To ensure that selective nuclear accumulation of IκBα but not IκBβ was achieved upon LMB treatment within the same cell, Cos cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged IκBα, IκBβ, and p50-p65 NF-κB subunits. Transfected cells were costained with antibodies specific to HA or IκBβ, and localizations of IκBα and IκBβ proteins were determined within the same cell. Exogenous IκBα was sensitive to LMB-induced nuclear accumulation, while IκBβ did not migrate substantially into the nucleus (Fig. 2B, upper and middle panels). These results demonstrate that cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-κB is controlled by at least two different mechanisms. When NF-κB is complexed with IκBα, the mechanism of localization is determined by the kinetics of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, with nuclear export being dominant during the preinduced state. However, cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB–IκBβ is not regulated by an LMB-sensitive export mechanism.

FIG. 2.

NF-κB–IκBβ complexes do not shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus in an LMB-sensitive manner. (A) Wild-type MEFs were untreated or treated with LMB (20 ng/ml for 30 min), fixed, and stained with either IκBβ (C-20) or IκBα (C-21) antibodies. Cells were also costained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin to visualize actin for cell cytoskeleton integrity. For control, cells were also treated with LMB or TNF-α as above and localization of p65 (C-20) was assessed. (B) Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged IκBα (1.0 μg), IκBβ (1.0 μg), p50 (1.0 μg), and p65 (1.0 μg) constructs, untreated or treated with LMB as described for panel A, and stained with HA (red) and IκBβ (green) antibodies. Cells were also stained with Hoechst DNA dye (blue).

NF-κB cannot be sequentially activated without IκBα.

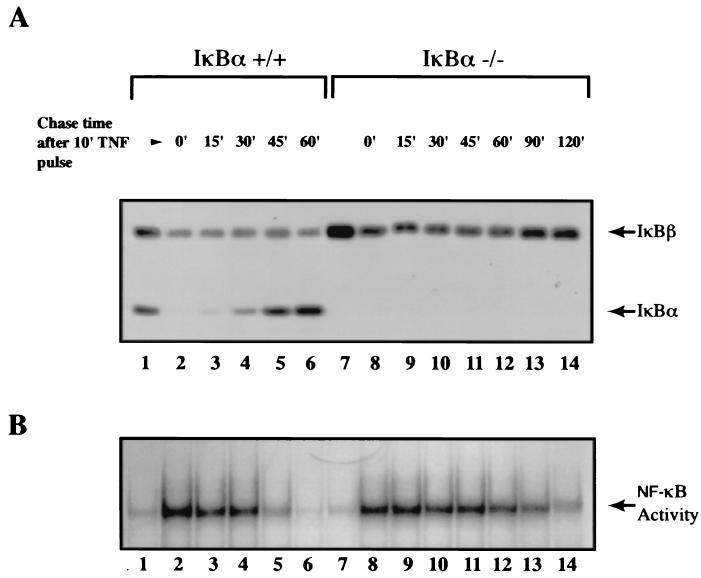

It was recently shown that when the IκBβ gene was replaced into the IκBα locus under control of the IκBα promoter, it could repress nuclear NF-κB DNA-binding activity following pulse induction with TNF-α (6). Thus, it was concluded that IκBβ is functionally equivalent to IκBα. However, we hypothesize that the export of NF-κB following the repression of NF-κB DNA-binding activity allows the system to become permissive for reactivation or postrepression activation of NF-κB. If NF-κB–IκB complexes are nuclear, reactivation by a second round of stimulation would not occur, since the activation event takes place primarily in the cytoplasmic compartment. To directly test this hypothesis, we first established the condition in which postinduction repression of NF-κB DNA-binding activity can be reproducibly detected using both wild-type and IκBα-deficient MEFs (Fig. 3). As expected, resynthesis of IκBα directly correlated with the reduction of NF-κB DNA-binding activity in wild-type cells (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 3 to 6). Similarly, NF-κB DNA-binding activity decreased, in good agreement with increased IκBβ protein levels in IκBα-deficient cells, but this effect required longer durations due to the lack of NF-κB-dependent transcription of the IκBβ gene (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 6 and 14). Once these conditions were established, MEFs were pulse stimulated with TNF-α and then chased with medium without TNF-α for 2 h before reactivation studies were performed (diagram in Fig. 4). Secondary stimulation of these cells with TNF-α reactivated NF-κB DNA-binding activity in wild-type cells (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 4). Importantly, while degradation of IκBα was observed during the reactivation phase, IκBβ was mostly refractory to this process (Fig. 4A and B, lower panels, lanes 4). Consistent with the above observation and also with our hypothesis, TNF-α could not efficiently activate NF-κB for the second time in the absence of IκBα (Fig. 4B, lower panel, lanes 2 to 4). These results for the first time demonstrate that the postrepression activation of NF-κB requires the NF-κB-dependent resynthesis of IκBα, which cannot be compensated for by other IκB family members.

FIG. 3.

Kinetic analyses of postinduction repression of NF-κB DNA-binding activity in the presence and absence of IκBα protein. (A) Wild-type and IκBα-deficient MEFs were pulse treated for 10 min with TNF-α (10 ng/ml; lanes 2 to 6 and 8 to 14) and subsequently chased with fresh medium without TNF-α for the indicated amounts of time (0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min). Lanes 1 and 7, untreated control samples. Total cell extracts from the samples were analyzed by Western blotting using IκBα- and IκBβ-specific antibodies (A) and EMSA as described above (B).

FIG. 4.

NF-κB cannot be sequentially activated in the absence of IκBα. (A) Wild-type MEFs were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 10 min; lanes 2 to 4), then chased with fresh medium for 120 min (lanes 3 and 4), and finally restimulated with TNF-α as above for 10 min (lane 4). Total cell extracts were analyzed by both EMSA (upper panel) and Western blotting (lower panel). The experimental setup is diagrammed above. Numbers in parentheses signify the lanes of the sample that were treated. (B) IκBα-deficient MEFs were treated as described above. IκBα- and IκBβ-specific antibodies were used in both A and B.

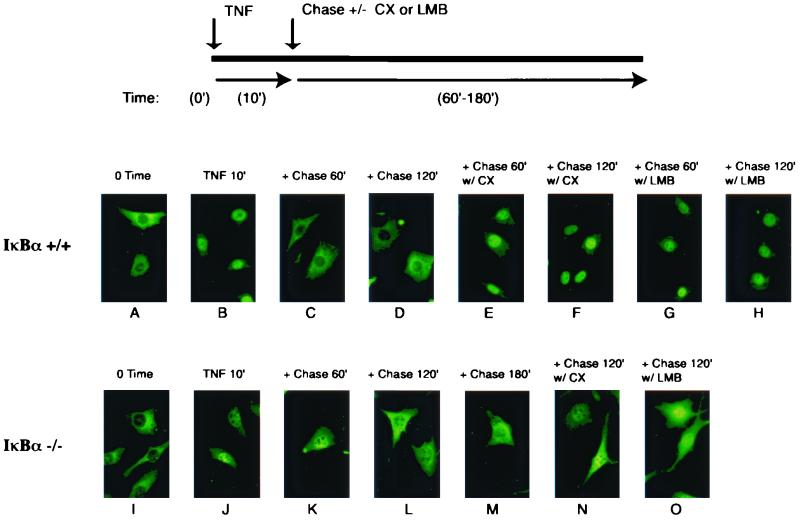

Postinduction export of nuclear NF-κB is inefficient in the absence of IκBα.

Our EMSA analyses indicate that postinduction export of inactive NF-κB complexes out of the nucleus requires the presence of IκBα. To directly determine the localization of NF-κB–IκB complexes during the postinduction phase, we examined the localization of the endogenous p65 by immunofluorescence in wild-type and IκBα−/− MEFs. The outline of the postinduction export experiment is diagrammed in Fig. 5. Consistent with NF-κB-dependent synthesis of IκBα within 30 to 60 min post-TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3), nuclear p65 in the wild-type cells was efficiently exported out to the cytoplasm within 60 min of chase without TNF-α (Fig. 5, panels C and D). Inclusion of cycloheximide or LMB during the chase period blocked the export of p65 (Fig. 5, panels G and H), demonstrating that nuclear export of NF-κB during the postinduction phase indeed requires IκBα resynthesis and an NES-dependent process. However, in the IκBα-deficient MEFs, the majority of p65 remained in the nucleus after 60 min during the chase period (Fig. 5, panel K). Even after 3 h of chase, a large pool of p65 was nuclear (panels L and M), correlating with the resistance of NF-κB to reactivation by TNF-α (Fig. 4). Interestingly, adding LMB during the chase period caused a further increase in the amount of p65 in the nucleus (panel O). This observation suggests that an NES-dependent process was responsible for some p65 export during the prolonged chase period in IκBα-deficient cells. These observations together demonstrate that while efficient and rapid export of NF-κB during postinduction phase requires the resynthesis of IκBα, it can be exported less effectively in the absence of IκBα, possibly via the recently identified NES on the p65 subunit.

FIG. 5.

Postinduction export of NF-κB is sensitive to LMB and inefficient in the absence of IκBα. Wild-type and IκBα-deficient MEFs were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 10 min; panels B to H and J to O) and chased with fresh medium for the indicated amounts of time (60, 120, or 180 min) in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (CX; 10 μg/ml) or LMB (20 ng/ml). The experimental setup is diagrammed above. The treated cells were then fixed and the endogenous p65 was stained with p65 (C-20)-specific antibody.

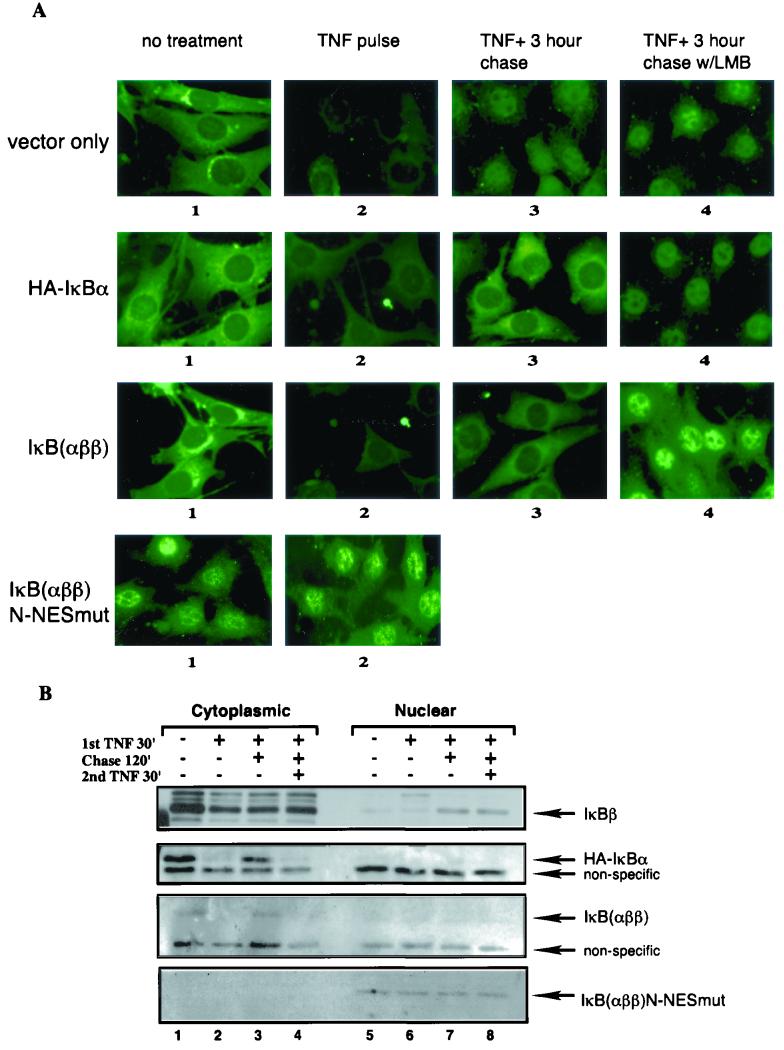

IκBβ can enter the nucleus but is not efficiently exported during postinduction phase.

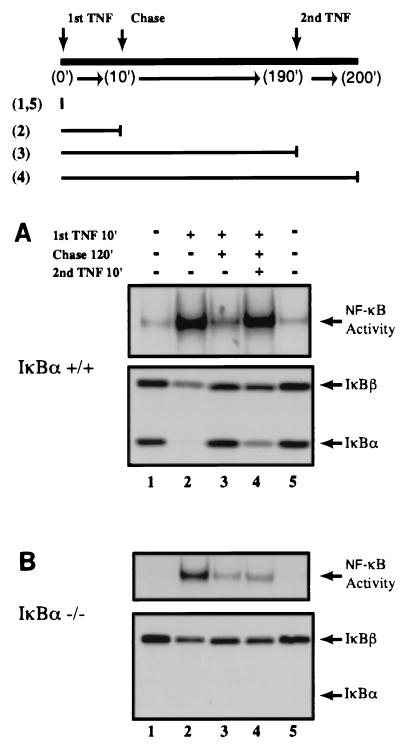

The observations thus far suggest that NF-κB associated with IκBα is exported efficiently but NF-κB associated with IκBβ is not during the postinduction phase. Direct examination of subcellular localization of IκBβ during postinduction phase by both immunofluorescence and biochemical subfractionation analyses confirmed that indeed newly synthesized IκBβ can enter the nucleus (Fig. 6A, vector only, panel 3, and 6B, compare IκBβ, lane 7). Interestingly, the signal detected by C20 anti-IκBβ antibody in immunofluorescence showed a similar extent of degradation as with IκBα after 30 min of TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 6A, compare panels 2), but Western blot analyses consistently showed incomplete IκBβ degradation compared to IκBα within the same time frame (Fig. 6B, IκBβ and IκBα, lanes 2). The significance of this observation is discussed below (see Discussion). Importantly, while the presence of nuclear IκBβ correlated well with the repression of NF-κB DNA-binding activity in IκBα-deficient cells, IκBβ was not exported out of the nucleus even up to 3 h during the chase period. LMB showed very little effect during the chase period (Fig. 6A, panel 4), suggesting that subcellular localization of IκBβ is not affected by an NES-dependent export process. The lack of nuclear export of IκBβ was not due to some defect of the IκBα-deficient cell system used because when IκBα tagged with the HA epitope (HA-IκBα) was stably expressed, HA-IκBα was efficiently exported during the postinduction phase in an LMB-sensitive fashion in a manner identical to endogenous IκBα in wild-type cells (Fig. 6A, HA-IκBα, panels 3 and 4). These results demonstrate that while newly synthesized IκBβ can enter the nucleus, it fails to export efficiently out of the nucleus during the postinduction phase.

FIG. 6.

N-terminal region containing the N-NES of IκBα is sufficient to mediate the postinduction export function. (A) IκBα-deficient MEFs were stably transfected with either vector (vector only), HA-tagged IκBα (HA-IκBα), IκBαββ chimera (IκBαββ), or N-terminal NES mutant IκBαββ chimera contructs (IκBαββ N-NESmut). Pools of stable transfectants were isolated, and subcellular localization of IκBs was visualized using antibodies against IκBβ (C-20, vector only), IκBα (C-21, HA-IκBα), N-terminal 56 amino acids of IκBα (5432, IκBαββ, and IκB αββ N-NESmut). The cells were also treated with TNF-α for 60 min (panels 2 to 4), chased with fresh medium for 180 min (panels 3), or in the presence of LMB (panels 4). (B) Stably transfected MEFs as above were either untreated (lanes 1 and 5), pulsed with TNF-α for 30 min (lanes 2 and 6), chased with fresh growth medium for 120 min (lanes 3 and 7), and rechallenged with TNF-α for another 30 min (lanes 4 and 8). Samples from each pool of cells were fractionated as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against IκBβ (C-20), IκBα (C-21), and amino-terminal IκBα (5432) for the detection of the chimera protein. Samples from vector only, HA-IκBα, IκBαββ, or IκBαββ N-NESmut are shown as panels with arrows indicating IκBβ, HA-IκBα, IκBαββ or IκBαββ N-NESmut, respectively.

IκBα N-NES is sufficient to mediate postinduction export function.

There are a total of three independent NES motifs reported on IκBα–NF-κB complexes, the N- and C- terminal NES motifs on IκBα and a p65 NES (2, 16, 17, 23, 40, 43). There is a controversy as to which of these putative NES sequences provide(s) the dominant nuclear export function for the complexes during the postinduction phase. To conclusively determine whether N-NES is sufficient to dominantly export the NF-κB–IκB complexes in the absence of C-NES, we asked whether IκBα N-terminal to the first ankyrin repeat could support dominant nuclear export function in the context of IκBβ protein. We therefore generated an IκBβ chimera expression construct in which the IκBβ N-terminal region upstream of the first ankyrin repeat was swapped with the N-terminal aa 1 to 66 of IκBα (IκBαββ) and stably expressed it in IκBα-deficient MEFs. Similar to HA-IκBα, the chimeric protein was largely expressed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A, panel 1) and associated with NF-κB as demonstrated by a coimmunoprecipitation assay (not shown). Degradation of IκBαββ after pulse stimulation with TNF-α was complete like IκBα but unlike IκBβ (Fig. 6A, IκBαββ, panel 2; Fig. 6B, IκBαββ, lane 2). Importantly, resynthesized IκBαββ was predominantly cytoplasmic, but LMB during the chase period trapped it in the nucleus (Fig. 6A, IκBαββ, panels 3 and 4). These results suggest that the N-terminal sequence of IκBα was able to dominantly export the chimeric complexes out of the nucleus.

To formally demonstrate that the export function of IκBαββ is mediated by the N-NES of IκBα, we mutated the NES sequence in the context of IκBαββ (IκBαββ N-NESmut), as described previously (17). IκBαββ N-NESmut was also stably introduced in the IκBα knockout MEFs. If N-NES is dominant for the localization of NF-κB–IκBαββ complexes, then we expected that the steady-state localization of the complexes would be nuclear in unstimulated cells. However, if N-NES had a minor effect, the complexes would be expected to be predominantly cytoplasmic. Our immunolocalization and biochemical fractionation analyses demonstrated that IκBαββ N-NESmut was predominantly nuclear in unstimulated cells (Fig. 6A, IκBαββ N-NESmut, panel 1; Fig. 6B, IκBαββ N-NESmut, lane 5). The mutant protein was still able to associate with NF-κB in a co-immunoprecipitation assay (not shown). The nuclear IκBαββ N-NESmut was refractory to TNFα-induced degradation (Fig. 6A, panel 2; Fig. 6B, lane 6), consistent with the hypothesis that NF-κB activation requires its cytoplasmic localization. These findings demonstrate that N-NES of IκBα is sufficient to confer export function that is dominant over any known NES sequences present on inactive NF-κB–IκB complexes.

Postrepression activation of NF-κB also requires the IκBα N-NES. Using a biochemical subfractionation assay, we also tested whether the postinduction-resynthesized IκBβ, HA-IκBα, and IκBαββ proteins in the context of IκBα knockout cells were capable of being degraded following a second stimulation with TNF-α (Fig. 6B). Although resynthesized nuclear IκBβ protein was refractory to restimulation with TNF-α, reconstituted HA-IκBα was capable of being degraded in response to a second TNF-α challenge (Fig. 6B, IκBβ, lanes 7 and 8; HA-IκBα, lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, resynthesized IκBαββ was also subjected to degradation following restimulation with TNF-α, demonstrating that the IκBα N-NES is sufficient to confer export function on the IκBβ protein to mediate postrepression activation of NF-κB (Fig. 6B, IκBαββ, lanes 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

Recently, several groups, including ours, discovered that NF-κB–IκBα inactive complexes shuttle continuously between the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments to achieve a predominant cytoplasmic localization during the absence of NF-κB-activating signals (17, 23, 38, 43). Maintaining the cytoplasmic localization of the inactive complexes is essential for NF-κB function, since signals derived from either the plasma membrane or the nucleus to target the degradation of IκBα are blocked if the inactive complexes are sequestered in the nuclear compartment (17, 18, 38). We therefore asked whether regulation of NF-κB by nucleocytoplasmic shuttling was a conserved mechanism of all IκB family members that negatively influence the important NF-κB family of transcriptional regulators.

By scanning the primary amino acid sequences, we failed to identify a similar N-NES motif present in IκBα in the N-terminal regions of mammalian IκBβ, p105/IκBγ, p100, IκBɛ, Bcl-3, and the Drosophila IκB homolog cactus (Fig. 1A). A classical NES sequence was also undetected in other regions of the IκB family members. These observations suggested that IκBα might be the only IκB family member that contained a novel nuclear export capacity to mediate rapid export of nuclear NF-κB. These sequence analyses further implied that IκBα might be a more recently evolved family member. Coincidentally, IκBα is one of the major NF-κB target genes in mammalian cells, which forms the autoinhibitory feedback loop to perform the postinduction repression of NF-κB function. Even without the presence of a conserved N-terminal NES on IκBβ, we could not rule out the possibility that the NF-κB–IκBβ complexes still shuttle in an LMB-sensitive manner, since a recent report has shown that the p65 subunit of NF-κB possesses a bona fide NES motif (16).

In the present study, we found that LMB selectively blocked the signal-induced degradation of IκBα but not IκBβ. IκBα knockout cells confirmed that TNFα-induced NF-κB activation cannot be inhibited by LMB in the absence of IκBα, since NF-κB–IκBβ, and possibly other NF-κB–IκB complexes, is insensitive to the LMB effect in these cells. Moreover, unlike IκBα-containing NF-κB complexes, NF-κB–IκBβ complexes that contained the p65 subunit were still largely refractory to LMB-induced nuclear accumulation. These surprising results enabled us to modify the NF-κB cytoplasmic sequestration model (3, 12), in which IκB proteins, excluding IκBα, are likely proficient in masking the dual NF-κB NLS motifs. Studies with IκBαββ suggest that the N-terminal sequence of IκBβ is required for efficient masking of NF-κB NLS sequences, since swapping of this region with that of IκBα permitted NF-κB associated with the chimera protein to shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 6 and unpublished observation).

The NF-κB–IκBα complexes, on the other hand, behave differently from other IκB proteins in that cytoplasmic localization of the complexes is a result of a dynamic balance between nuclear import and active nuclear export forces. This notion is further supported by the observation of incomplete p50 NLS masking by IκBα ankyrin repeats in NF-κB–IκBα cocrystals (19, 22) and the finding that the p65 NLS but not the p50 NLS motif is involved in direct association with IκBα (36). Even though at least three NES motifs have been identified in the NF-κB–IκBα trimeric complex (2, 16, 17, 23, 40, 43), our data demonstrate that their nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is dominantly controlled by the IκBα N-NES motif, since (i) these complexes do not efficiently shuttle when the IκBα N-NES is mutated or deleted (17), (ii) an IκBα C-NES mutation has little effect on shuttling of the complexes (17, 23, 43), (iii) they also efficiently shuttle without p65 protein or when p65-NES is deleted (unpublished observation), and (iv) the IκBα N-NES is sufficient to confer dominant shuttling function when grafted onto the IκBβ protein.

What is unclear is whether there are any physiological advantages to maintaining an energy-consuming and apparently futile shuttling process in order to preserve the asymmetric distribution of NF-κB–IκBα complexes in the preinduced state. Perhaps it is more efficient to regulate the localization of shuttling proteins by simply adjusting the rate of nuclear entry versus export in order to drastically alter the steady-state subcellular distribution of the complexes. It is conceivable that as yet undiscovered physiological control of NF-κB activity may exist which involves the altered regulation of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the inactive complexes. Adjusting the kinetics of shuttling by having the rate of import exceed the rate of export may be a novel mechanism to attenuate NF-κB function. However, our findings suggest that, depending on the ratio of NF-κB associated with IκBα or IκBβ or other IκB family members, only a subset of inactive NF-κB pools may be subjected to this type of regulation. This may explain why certain investigators fail to observe large effects of LMB on NF-κB activation in different experimental settings (23).

In contrast, what is clear from our present study is that the nuclear export function of IκBα N-NES is essential for rapid and efficient export of inactive NF-κB complexes out of the nucleus during the postinduction phase. Our findings from IκBα knockout cells demonstrate that other IκB family members could not efficiently perform this function. We found, in accordance with studies using cells isolated from IκBβ knockin mice (6), newly synthesized IκBβ protein was able to enter the nucleus and repress NF-κB DNA-binding activity. However, IκBβ, which does not possess a functional NES, could not efficiently carry NF-κB out of the nucleus. Thus, only IκBα protein was able to prime the NF-κB system for a subsequent reactivation event or provide a permissive condition for postrepression activation to take place.

Wild-type cells, which can properly export postinduced nuclear NF-κB out to the cytoplasm, could efficiently respond to secondary NF-κB stimuli. IκBα-deficient cells, however, were refractory to this NF-κB reactivation process. Thus, it is logical to consider that the initial postinduction repression of NF-κB DNA-binding activity is an important mechanism to rapidly shut off NF-κB-dependent gene transcription following a short exposure to cytokine stimulation in a biological setting. This IκB-mediated repression and removal of NF-κB from its DNA-binding sites may be necessary, since NF-κB has been shown to bind its cognate sites with very slow off rates in vitro (36). In addition, efficient removal of NF-κB from cognate DNA-binding sites may also be critical for allowing the NF-κB–IκBα complexes to interact with the soluble transport machinery, Crm1 and RanGTP (25, 28). Subsequently, the nuclear export of inactive NF-κB–IκBα complexes provides another important function to allow cells to become quickly permissive for a second challenge with either cytokine, bacterial, or viral insults. Without efficient export of nuclear NF-κB, the secondary activation process is defective. Thus, the nuclear export function of IκBα may contribute to the ability of an organism to respond rapidly to multiple cellular infections.

It is interesting to consider whether the N-NES of IκBα may have evolved to permit sequential NF-κB activation. Because the N-NES of IκBα needs to interact with Crm1 for export function, i.e., exposed on the surface of NF-κB–IκBα complexes, this domain may have lost the capacity to efficiently mask the p50 NLS. These events may have caused the NF-κB–IκBα complexes to nucleocytoplasmically shuttle in the preinduced conditions by default. Important goals of future investigation include determining how nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of NF-κB–IκBα complexes is regulated and whether disruption of these regulatory mechanisms has drastic biological and/or pathological consequences.

It is well known that IκBβ is less responsive to stimulus-induced degradation than IκBα, as determined by Western blot analyses. However, the mechanism for this resistance is unclear. Unexpectedly, we found that when IκBβ degradation was assessed by immunostaining using C20 IκBβ antibody, TNF-α stimulation caused almost complete loss of immunoreactivity, similar to that found with IκBα antibodies (Fig. 6). However, the same IκBβ antibody still showed only partial degradation on Western blot analyses, consistent with the weaker responsiveness of IκBβ to TNF-α-induced degradation. The pool of IκBβ that was resistant to initial TNF-α stimulation remained refractory to secondary stimulation even though it remained cytoplasmic, indicating that this pool of IκBβ is not accessible to the stimulus-induced degradation pathway. A recent study by Ghosh and colleagues found that κB-Ras might be critical for retarding IκBβ degradation during the NF-κB activation process (9). Interestingly, the interaction between κB-Ras and IκBβ is mediated by the C-terminal region of IκBβ, which contains the epitope recognized by C20 antibody. It is possible that when κB-Ras is bound to IκBβ, C20 may not recognize IκBβ due to epitope masking. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that there are at least two pools of IκBβ, one free of κB-Ras and the other associated with it. The IκBβ pool that is free of κB-Ras may be accessible for immunostaining with C20 and efficiently degraded by TNF-α stimulation. In contrast, IκBβ bound to κB-Ras might be inaccessible for immunostaining using C20 antibody and resistant to degradation. Thus, our study suggests that the C20 antibody may provide a useful tool to help elucidate the mechanism of partial degradation of IκBβ during NF-κB activation processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Baltimore for IκBα knockout MEFs and p65 knockout 3T3 cells, D. Ballard for human p65 cDNA, S. Shumway for critical reading of the manuscript, and M. Yoshida for continued support and the generous gift of LMB.

This work was supported by an NIH predoctoral training grant award through the Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology graduate program to T.T.H. and NIH RO1 CA77474, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fund through the University of Wisconsin Medical School, and the Shaw Scientist Award from the Milwaukee Foundation to S.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Thompson J, Rodriguez M S, Bachelerie F, Thomas D, Hay R T. Inducible nuclear expression of newly synthesized IκBα negatively regulates DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2689–2696. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Turpin T, Rodriguez M, Thomas D, Hay R T, Virelizier J-L, Dargemont C. Nuclear localization of IκBα promotes active transport of NF-κB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:369–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beg A A, Ruben S M, Scheinman R I, Haskill S, Rosen C A, Baldwin A S J. IκB interacts with the nuclear localization sequences of the subunits of NF-κB: a mechanism for cytoplasmic retention. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1899–1913. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beg A A, Sha W C, Bronson R T, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-κB. Nature. 1995;376:167–70. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Z D, Xiong J, Takeuchi M, Kurama T, Goeddel D V. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng J D, Ryseck R P, Attar R M, Dambach D, Bravo R. Functional redundancy of the nuclear factor κB inhibitors IκBα and IκBβ. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1055–1062. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Q, Cant C A, Moll T, Hofer-Warbinek R, Wagner E, Birnstiel M L, Bach F H, de Martin R. NF-κB subunit-specific regulation of the IκBα promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13551–13557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiao P J, Miyamoto S, Verma I M. Autoregulation of IκBα activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:28–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenwick C, Na S-Y, Voll R E, Zhong H, Im S-Y, Lee J W, Ghosh S. A subclass of ras proteins that regulate the degradation of IκB. Science. 2000;287:869–873. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj I W. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda M, Asano S, Nakamura T, Adachi M, Yoshida M, Yanagida M, E. N. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997;390:308–311. doi: 10.1038/36894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganchi P A, Sun S C, Greene W C, Ballard D W. IκB/MAD-3 masks the nuclear localization signal of NF-κB p65 and requires the transactivation domain to inhibit NF-κB p65 DNA binding. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1339–1352. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geisler R, Bergmann A, Hiromi Y, Nusslein-Volhard C. cactus, a gene involved in dorsoventral pattern formation of Drosophila, is related to the IκB gene family of vertebrates. Cell. 1992;71:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh S, Gifford A M, Riviere L R, Tempst P, Nolan G P, Baltimore D. Cloning of the p50 DNA binding subunit of NF-κB: homology to rel and dorsal. Cell. 1990;62:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90276-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh S, May M J, Kopp E B. NF-κB and rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harhaj E W, Sun S C. Regulation of RelA subcellular localization by a putative nuclear export signal and p50. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7088–7095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang T T, Kudo N, Yoshida M, Miyamoto S. A nuclear export signal in the N-terminal regulatory domain of IκBα controls cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-κB/IκBα complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1014–1019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang T T, Wuerzberger-Davis S M, Seufzer B J, Shumway S D, Kurama T, Boothman D A, Miyamoto S. NF-κB activation by camptothecin: a linkage between nuclear DNA damage and cytoplasmic signaling events. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9501–9509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huxford T, Huang D-B, Malek S, Ghosh G. The crystal structure of the IκBa/NF-κB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-κB inactivation. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue J, Kerr L D, Kakizuka A, Verma I M. IκBγ, a 70 kd protein identical to the C-terminal half of p110 NF-κB: a new member of the IκB family. Cell. 1992;68:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90082-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito C Y, Kazantsev A G, Baldwin A S J. Three NF-κB sites in the IκBα promoter are required for induction of gene expression by TNFα. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3787–3792. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs M D, Harrison S C. Structure of an IκBα/NF-κB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson C, Antwerp D V, Hope T J. An N-terminal nuclear export signal is required for the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of IκBα. EMBO J. 1999;18:6682–6693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaffman A, O'Shea E K. Regulation of nuclear localization: a key to a door. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:291–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudo N, Matsumori N, Taoka H, Fujiwara D, Schreiner E P, Wolff B, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9112–9117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kudo N, Wolff B, Sekimoto T, Schreiner E P, Yoneda Y, Yanagida M, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Bail O, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Israel A. Promoter analysis of the gene encoding the IκBα/MAD3 inhibitor of NF-κB: positive regulation by members of the rel/NF-κB family. EMBO J. 1993;12:5043–5049. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattaj I W, Englmeier L. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: the soluble phase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:265–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercurio F, DiDonato J A, Rosette C, Karin M. p105 and p98 precursor proteins play an active role in NF-κB-mediated signal transduction. Genes Dev. 1993;7:705–718. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyamoto S, Chiao P J, Verma I M. Enhanced IκBα degradation is responsible for constitutive NF-κB activity in mature murine B-cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3276–3282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto S, Seufzer B, Shumway S. Novel IκBα degradation process in WEHI231 murine immature B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:19–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naviaux R K, Costanzi E, Hass M, Verma I M. The pCL vector system—rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:5701–5705. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5701-5705.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neri A, Chang C C, Lombardi L, Salina M, Corradini P, Maiolo A T, Chaganti R S, Dalla-Favera R. B cell lymphoma-associated chromosomal translocation involves candidate oncogene lyt-10, homologous to NF-κB p50. Cell. 1991;67:1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohno H, Takimoto G, McKeithan T W. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 is related to genes implicated in cell lineage determination and cell cycle control. Cell. 1990;60:991–997. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90347-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ossareh-Nazari B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phelps C B, Sengchanthalangsy L L, Huxford T, Ghosh G. Mechanisms of IκBα binding to NF-κB dimers. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29840–29846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice N R, MacKichan M L, Israel A. The precursor of NF-κB p50 has IκB-like functions. Cell. 1992;71:243–253. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90353-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez M S, Thompson J, Hay R T, Dargemont C. Nuclear retention of IκBα protects it from signal-induced degradation and inhibits nuclear factor κB transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9108–9115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sachdev S, Bagchi S, Zhang D D, Mings A C, Hannink M. Nuclear import of IκBα is accomplished by a ran-independent transport pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1571–1582. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1571-1582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachdev S, Hannink M. Loss of IκBα-mediated control over nuclear import and DNA binding enables oncogenic activation of c-Rel. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5445–5456. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stade K, Ford C S, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun S C, Ganchi P A, Ballard D W, Greene W C. NF-κB controls expression of inhibitor IκBα: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science. 1993;259:1912–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tam W F, Lee L H, Davis L, Sen R. Cytoplasmic sequestration of rel proteins by IκBα requires Crm1-dependent nuclear export. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2269–2284. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2269-2284.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson J E, Phillips R J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. IκBβ regulates the persistent response in a biphasic activation of NF-κB. Cell. 1995;80:573–582. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verma I M, Stevenson J K, Schwarz E M, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-κB/IκB family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whiteside S T, Epinat J-C, Rice N R, Israel A. IκBɛ, a novel member of the IκB family, controls RelA and cRel NF-κB activity. EMBO J. 1997;16:1413–1426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zabel U, Baeuerle P A. Purified human IκB can rapidly dissociate the complex of the NF-κB transcription factor with its cognate DNA. Cell. 1990;61:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90806-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]