Abstract

Aichi viruses isolated in Vero cells from seven patients in five gastroenteritis outbreaks in Japan, five Japanese returning from Southeast Asian countries, and five local children in Pakistan with gastroenteritis were examined for differentiation based on their reactivities with a monoclonal antibody to a standard strain (A846/88) and a reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) of three genomic regions. The RNA sequences were determined for 519 bases of these 17 isolates at the putative junction between the C terminus of 3C and the N terminus of 3D. The analyses revealed an approximately 90% homology between these isolates, which were then divided into two groups: group 1 (genotype A) included six isolates from four outbreaks and one isolate from a traveler and group 2 (genotype B) included one isolate from the other outbreak, four isolates from returning travelers, and all of the isolates from the Pakistani children. Based on the isolate sequences, a primer pair and a biotin-labeled probe were designed for amplification and detection of 223 bases at the 3C-3D junction of Aichi virus RNA in fecal specimens. The Aichi virus RNA was detected in 54 (55%) of 99 fecal specimens from the patients in 12 (32%) of 37 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in Japan. Of the 12 outbreaks, 11 were suspected to be due to genotype A. These results indicated that RT-PCR can be a useful tool to detect Aichi virus in stool samples and that a sequence analysis of PCR products can be employed to identify the prevalent strain in each incident.

Aichi virus was first recognized in 1989 as the cause of oyster-associated nonbacterial gastroenteritis in humans. The ability to grow in cultured cells along with other biological properties suggested that Aichi virus was a member of the enteroviruses. However, none of the enterovirus antisera neutralized Aichi virus. Furthermore, a morphological study of purified Aichi virus virions indicated that the surface structure is characteristic of a small round virus (28). Recent genetic analyses performed on Aichi virus revealed that Aichi virus should be classified as a new type of the Picornaviridae family rather than any other genus such as Enterovirus, Rhinovirus, Cardiovirus, Aphthovirus, and Hepatovirus, as well as the echovirus 22 group (24). Recently, this virus was assigned to a new genus named Kobuvirus in the family Picornaviridae (14). “Kobu” means bump or knob in Japanese, which is derived from the characteristic morphology of the virus particle.

Aichi virus was isolated in Vero cells from 6 (12.3%) of 47 patients in five gastroenteritis outbreaks, 5 (0.7%) of 722 Japanese travelers returning from tours to Southeast Asian countries and complaining of gastrointestinal symptoms at the quarantine station of Nagoya International Airport in Japan, and 5 (2.3%) of 222 Pakistani children with gastroenteritis (25, 26). In this study, based on the nucleotide sequences of this virus, we developed a reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) method for the detection of Aichi virus and describe the antigenic and genetic analysis of these isolates in order to determine the relationship between Aichi virus isolates in Japan and those in other countries.

Viral gastroenteritis is a common illness, occurring in both epidemic and endemic forms. Rotaviruses, adenovirus types 40 and 41, Norwalk-like viruses, and astroviruses have been recognized as major etiological agents of human gastroenteritis (2–7). Aichi virus was also determined to be one of the causative agents of human gastroenteritis. In the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), 13 (23%) of 47 stool samples from adult patients in five oyster-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks were found to be positive for Aichi virus. However, seroconversion against Aichi virus was observed in 20 (47%) of 43 patients involved in these five outbreaks by a neutralization test using paired sera (26). These results suggested that the ELISA was not sufficient for diagnosis of the Aichi virus infection. RT-PCR for Aichi virus was also applied for detection of the RNA in stool samples to reveal the distinct prevalence of this virus in gastroenteritis outbreaks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The Aichi virus strains used in this study consisted of A1156/87 and A1258/87 from an oyster-associated gastroenteritis outbreak in March 1988; A844/88, A846/88 (standard strain), and A848/88 from an outbreak in March 1989; and A942/89 from an outbreak in December 1989 in Japan as previously reported (26). Strain A1471/96 was isolated from a patient with gastroenteritis from an outbreak in Aichi Prefecture in January 1997 and also used in this study. Aichi virus strains T132/90, M166/92, N128/91, N1277/91, and N628/92 were isolated from Japanese travelers returning from Thailand (T), Malaysia (M), and Indonesia (N) who had complained of gastrointestinal symptoms at the quarantine station of Nagoya International Airport between 1990 and 1992. P766/90, P803/90, P832/90, P840/91, and P880/90 were isolated from children with gastroenteritis in Pakistan between 1990 and 1992 (25). All 66 types of enteroviruses (including echovirus types 22 and 23) were obtained from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan. Astrovirus (types 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) was obtained from O. Nishio, National Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

The standard Aichi virus strain, A846/88, was grown in Vero cells and purified by CsCl and sucrose density gradient centrifugation, as described elsewhere (28). The purified strain (50 mg/ml) was diluted from 10−2 to 10−10 and applied for sandwich ELISA for detection of Aichi virus antigen as described previously (26), and an RT-PCR was developed in this study.

Stool samples.

Adult stool specimens examined in this study came from 268 subjects from 37 outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in Aichi Prefecture, Japan, between 1987 and 1998. Of the 37 outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis, 5 were confirmed to be associated with Aichi virus by detection with ELISA or seroconversion with a neutralizing test as described elsewhere (26). The sensitivity of the RT-PCR was compared with those of ELISA and seroconversion using the samples from these five outbreaks. Stool samples containing Norwalk-like virus were determined by an ELISA administered by K. Numata, Sapporo Medical College (20). Stool samples containing hepatitis A virus and rotavirus were determined at our laboratory by ELISA as described elsewhere (19, 30). Stool samples were also collected from 60 healthy children attending kindergarten. All stool samples were prepared as 10% homogenates in veal infusion broth with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (fraction V; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatants were stored at −30°C until the RT-PCR assay.

ELISA.

Aichi virus antibody-secreting hybridomas against the standard strain (A846/88) were prepared as described elsewhere (15, 27). The ELISA used to compare the reactivities to Aichi virus isolates was performed as follows. An anti-Aichi virus (A846/88) guinea pig antiserum, diluted 1:10,000 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), was used as the capture antibody. After a second coating, 100 μl of cell-cultured isolates (103 to 104 50% tissue culture infective doses per 25 μl) was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. After a wash, 100 μl of anti-Aichi virus monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), diluted 1:1 × 104 to 1:512 × 104 in PBS-Tween 20 with 1% bovine serum albumin, was added. After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the plates were washed, and 100 μl of peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) in PBS-Tween with 1% (bovine serum albumin was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. For color development, o-phenylenediamine (Wako Chemical, Osaka, Japan) was used. The MAb titer for each of the isolates was defined as the greatest dilution giving an optical density reading three times greater than that in virus-free wells and with an optical density value greater than 0.2.

Primers used in RT-PCR.

The primer pairs A, B, and C were initially designated for RT-PCR of Aichi virus isolates based on the sequence of the Aichi virus genome (accession no. AB010145). The sequences of the primers were selected randomly from different regions of the viral genome. The oligonucleotide primer sequences were selected as follows: A (1321, 5′-TGGTCCCGTCTCATGCACTCCGC; 2028, 5′-CCGGCATGGAACTGTGAGCCGT) amplifies a 708-bp region of VP 0, B (5412, 5′-ACCTGCGGATCAACGTCACCTC; 5968, 5′-AGAGTAGGCAGCTTGAGGTTCC) amplifies a 557-bp region from the C terminus of 2C to the 3A-3B junction, and C (6261, 5′-ACACTCCCACCTCCCGCCAGTA; 6779, 5′-GGAAGAGCTGGGTGTCAAGA) amplifies a 519-bp region between the C terminus of 3C and the N terminus of 3D.

RT-PCR.

Aichi virus grown in Vero cells and fecal extracts were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected for RT-PCR. As described by Jiang et al. (13), 0.2 ml of fecal extract was mixed with 0.1 ml of 24% polyethylene glycol 6000 and 1.5 M NaCl solution, stored at 4°C overnight, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet was suspended in 0.1 ml of water for RT-PCR. Virus RNA was extracted using the TRIZOL LS reagent (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) followed by isopropanol precipitation. Each nucleic acid was suspended in RT (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) mixtures containing oligo(dT) 15 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and random primer pd (N) 9 (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. PCR mixtures, containing primer pairs, were added directly into each of the RT mixtures, and amplification was performed in a Thermal Cycler 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) for 40 cycles (each cycle was 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min). Analysis of the amplification product was performed by agarose minigel electrophoresis, and the product was confirmed as a distinct band with ethidium bromide staining.

Cycle sequencing.

Following RT-PCR, amplified products from 17 Aichi virus isolates and two to three positive fecal samples from outbreaks were purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. Purified RT-PCR products were then precipitated with ethanol, and pelleted DNA was suspended in Tris-EDTA buffer and introduced into a pGM-T vector (Promega). The DNA sequence was determined by using a SequiTherm LongRead Cycle Sequencing Kit-LC (Epicentre Technologies Corporation, Madison, Wis.) and a Model 4000 automated DNA sequencer (Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, Nebr.). The nucleotide sequence was determined at least twice in both directions. For sequence alignments, we examined dendrograms, utilizing UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with averages), in a Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis package.

Southern blot analysis.

Following amplification by RT-PCR and DNA sequencing of 17 Aichi virus isolates, a biotin-labeled probe (AiPrb2, 5′-biotin-ACCTTCGAAGGTCTGTGCGG) was synthesized and purified by Life Technologies Oriental, Inc., Tokyo, Japan. PCR products that migrated on agarose minigel electrophoresis gels were transferred to a nylon membrane (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) and irradiated with 120 mJ of UV light (254 nm) in an auto-cross-linker (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Blots were hybridized in 0.75 M NaCl–20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–2.5 mM EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–Denhardt's solution (0.2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Ficoll, and 0.2% polyvinylpyrrolidone)–50 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml at 55°C with AiPrb2. After 20 h of hybridization, all blots were washed with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C and stained with streptoavidin- and alkaline phosphatase-labeled biotin and an alkaline phosphatase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences described above have been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. AB034649 to AB034663.

RESULTS

Reactivity of MAb for isolates.

A selected hybridoma, which produced an antibody reactive with a prototype strain (A846/88), was designated clone Ai/8. The immunoglobulin subclass was determined to be immunoglobulin G1. The reactivity of the MAb for 17 isolates was examined by ELISA. MAb Ai/8 reacted at titers between 1:32 × 104 and 1:128 × 104 with 7 of 17 isolates. However, it reacted only weakly with 10 of 17 isolates at a titer of 1:2 × 104 or less. These 10 isolates included one from an outbreak in Japan; four from travelers returning from Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia; and all of those from the Pakistani children (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reactivities for 16 isolates of Aichi virus with MAb Ai/8 and RT-PCR for the standard strain

| Virus | Reactivity for MAb Ai/8b | Reactivity for RT-PCR using primer set

|

Genotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||

| A1156/87 | 32 | + | + | + | A |

| A1258/87 | 32 | + | + | + | A |

| A844/88 | 64 | + | + | + | A |

| A846/88a | 128 | + | + | + | A |

| A848/88 | 32 | + | + | + | A |

| A1471/96 | 32 | + | + | + | A |

| N128/91 | 32 | + | + | + | A |

| A942/89 | <1 | − | − | + | B |

| N1277/91 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

| N628/92 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

| T132/90 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

| M166/92 | <1 | − | − | + | B |

| P766/90 | 2 | − | − | + | B |

| P803/90 | <1 | − | − | + | B |

| P832/90 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

| P840/91 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

| P880/90 | 1 | − | − | + | B |

Standard strain.

Reciprocal titer, (×10,000).

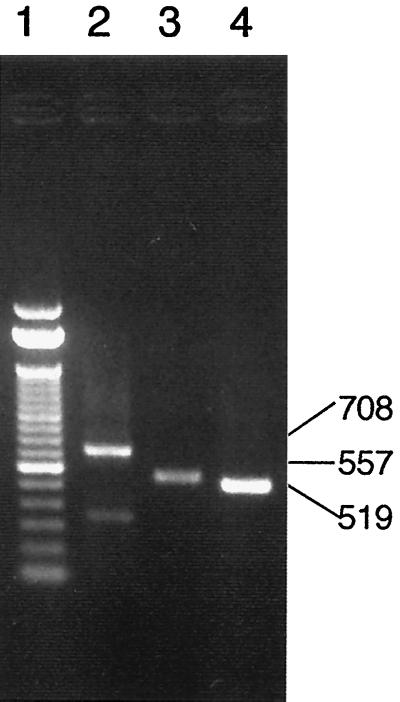

Reactivity for isolates in RT-PCR.

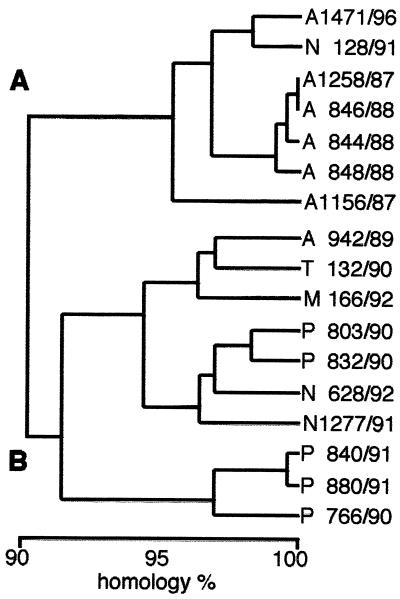

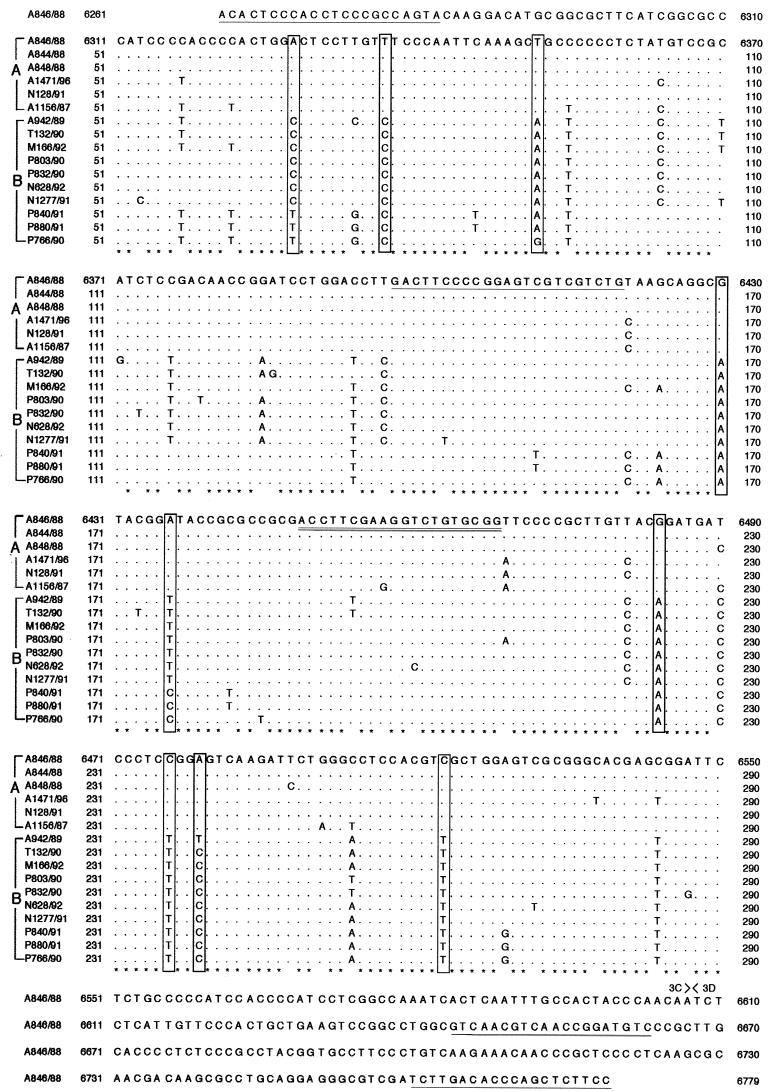

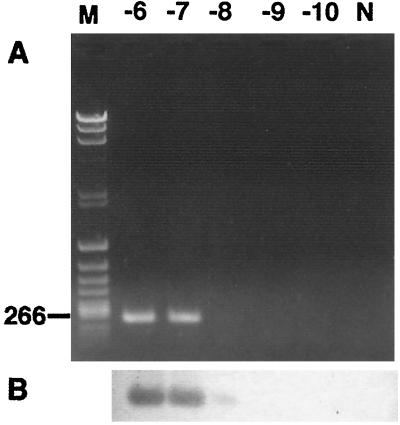

The three pairs of primers (A, B, and C) amplified 708, 557, and 519 bp, respectively. Figure 1 shows the results of RT-PCR-amplified products seen in an agarose gel after 40 cycles, using the Aichi virus standard strain (A846/88) RNA as the template. Seventeen isolates were examined by RT-PCR using these three primer sets. The primer sets A and B could not amplify the products of one isolate from an outbreak; four isolates from travelers returning from Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia; and all of the isolates of the Pakistani children with which MAb Ai/8 had reacted at low titers. The primer set C could amplify products from all 17 isolates at the putative junction between the C terminus of 3C and the N terminus of 3D. The sequence analysis of these products revealed approximately 90% homology among the 17 isolates. The dendrogram based on these sequences is depicted in Fig. 2, indicating that Aichi virus isolates could be divided into two groups (genotypes A and B). Figure 3 shows the sequence alignment of these isolates in the 3C region based on which the two genogroups were defined. These groups were also identified using reactivities for primer sets A and B and in ELISA using MAb Ai/8. Genogroup A stimulated a reaction in RT-PCR using primer sets A, B, and C and ELISA using MAb Ai/8. On the other hand, genogroup B did not stimulate a reaction by primer sets A and B and MAb Ai/8 (Table 1). Based on these sequences, a primer pair, C94b-246k (C94b, 5′-GACTTCCCCGGAGTCGTCGTCT; 246k, 5′-GACATCCGGTTGACGTTGAC), and a biotin-labeled probe (AiPrb2) were designated for the detection of 223 bp at the 3C-3D junction of Aichi virus RNA. These primers were unable to amplify RT-PCR products from Norwalk-like virus, rotaviruses, hepatitis A virus, 66 types of enteroviruses (including echovirus types 22 and 23), and 7 types of astroviruses. Aichi virus RNA was detected by RT-PCR using the primers C94b-246k followed by Southern blot analysis in a 10−8 dilution of purified strain A846/88 (50 mg/ml), while a 10−4 dilution of the sample was required to show a positive result by sandwich ELISA (Fig. 4). Based on the above results, these primers and probe AiPrb2, used for amplification and identification of the Aichi virus RNA from fecal specimens, were found to be effective.

FIG. 1.

Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of Aichi virus (A846/88 strain) RT-PCR products. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA ladder from GIBCO BRL; lanes 2 to 4, PCR with Aichi virus primer sets A (lane 2), B (lane 3), and C (lane 4). The numbers at right indicate the sizes of the RT-PCR products in base pairs.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of predicted genetic relationships among 17 isolates of Aichi virus by comparison of 519 bases at the putative junction between the C terminus of 3C and the N terminus of 3D.

FIG. 3.

Sequence of Aichi virus (A846/88) amplified with primer set C and partial alignment of nucleic acid sequences of isolates in the C terminus of the 3C region. Two genotypic groups (A and B) were defined by the boxed sequences. The position of the cleavage site between the 3C and 3D regions is indicated. The primer pairs C and C94b-245K are underlined, and a biotin-labeled probe (AiPrb2) is double underlined.

FIG. 4.

Detection of Aichi virus by RT-PCR with primers C94b-264k (A) and identification by Southern blot hybridization with probe AiPrb2 (B). Serial dilutions (from 10−6 to 10−10) of Aichi virus (50 mg/ml) were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. M, markers; N, negative control.

Detection of Aichi virus RNA in stool samples.

A total of 268 fecal specimens from 37 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in Aichi Prefecture, including 21 outbreaks of oyster-associated gastroenteritis, were examined by RT-PCR using the primer pair C94b-246K. Aichi virus RNA was detected in 54 (20.5%) of 268 samples (12 of 37 outbreaks) by the RT-PCR (Table 2). We found that 54 of 99 patients (55%) were Aichi virus positive in the 12 outbreaks. The positive rates ranged from 14 to 82%. On the other hand, 167 stool samples from the other 25 outbreaks were negative for Aichi virus RNA. Aichi virus was not also detected by RT-PCR in stool samples from 60 healthy children. Eleven of 12 outbreaks positive for Aichi virus were associated with oysters. The other outbreak (outbreak 9) occurred on a school excursion and was probably caused by supper at the students' hotel. Oysters were not contained in the food items prepared by the hotel. To determine the genotype of these positive samples, we sequenced 29 PCR products from isolates from these 12 outbreaks and compared their sequences with those from the 17 isolated Aichi viruses. The sequences of seven stool samples positive for virus isolation were found to be identical to those of the isolates. Of the 29 samples, 27 samples from 11 outbreaks were classified as genotype A and the other 2, from outbreak 6, were classified as genotype B. In 5 (outbreaks 1, 3, 7, 10, and 11) of these 12 outbreaks, both stool and paired serum samples were collected from 29 patients. Aichi virus was detected by RT-PCR in 19 (65.6%) of 29 patients from the five outbreaks (Table 3). This RT-PCR positive rate (65.6%) was higher than that for ELISA (37.9%) or seroconversion (58.6%). All samples positive for Aichi virus by ELISA or seroconversion were also positive by RT-PCR.

TABLE 2.

Outbreaks of gastroenteritis tested for Aichi virus by RT-PCR using primer pair C94b-264k

| Outbreak

|

RT-PCR result

|

Genotype (n)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Yr | Description | No. positive/no. tested | % | |

| 1 | 1987 | Oysters | 5/9 | 55.6 | A (3) |

| 2 | 1988 | Oysters | 5/7 | 71.4 | A (3) |

| 3 | Oysters | 9/11 | 81.8 | A (3) | |

| 4 | 1989 | Oysters | 0/3 | 0 | |

| 5 | Banquet | 0/4 | 0 | ||

| 6 | Banquet | 0/15 | 0 | ||

| 7 | Oysters | 4/5 | 80.0 | A (2) | |

| 8 | School lunch | 0/9 | 0 | ||

| 9 | School excursion | 9/14 | 64.3 | A (3) | |

| 10 | 1990 | Oysters | 2/4 | 50.0 | B (2) |

| 11 | Oysters | 6/11 | 54.5 | A (2) | |

| 12 | School lunch | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 13 | Oysters | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 14 | 1991 | Oysters | 4/6 | 66.7 | A (2) |

| 15 | 1992 | Oysters | 0/7 | 0 | |

| 16 | School lunch | 0/8 | 0 | ||

| 17 | Banquet | 0/7 | 0 | ||

| 18 | 1993 | School lunch | 0/10 | 0 | |

| 19 | 1994 | Oysters | 2/14 | 14.3 | A (2) |

| 20 | Delivered lunch | 0/4 | 0 | ||

| 21 | Oysters | 0/6 | 0 | ||

| 22 | School lunch | 0/6 | 0 | ||

| 23 | Delivered lunch | 0/7 | 0 | ||

| 24 | 1995 | School lunch | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 25 | 1996 | Oysters | 0/6 | 0 | |

| 26 | 1997 | Oysters | 5/8 | 62.5 | A (3) |

| 27 | Banquet | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 28 | Banquet | 0/3 | 0 | ||

| 29 | Dormitory supper | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 30 | Oysters | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 31 | Oysters | 0/7 | 0 | ||

| 32 | 1998 | School lunch | 0/16 | 0 | |

| 33 | Oysters | 2/4 | 50.0 | A (2) | |

| 34 | Oysters | 2/6 | 33.3 | A (2) | |

| 35 | Oysters | 0/4 | 0 | ||

| 36 | Oysters | 0/5 | 0 | ||

| 37 | Oysters | 0/12 | 0 | ||

| Total | 55/268 | 20.5 | A (27), B (2) | ||

Genotypes were determined for the limited number of fecal samples.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of sensitivities among RT-PCR, ELISA, and seroconversion in five outbreaks

| Outbreak no. | Patient no. | Identification of Aichi virus infection by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | ELISAa | Seroconversiona | ||

| 1 | 1 | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | |

| 3 | − | − | − | |

| 4 | − | − | − | |

| 5 | + | − | + | |

| 6 | + | + | + | |

| 7 | + | + | + | |

| 3 | 8 | − | − | − |

| 9 | + | + | + | |

| 10 | + | + | + | |

| 11 | + | − | + | |

| 12 | + | + | + | |

| 13 | − | − | − | |

| 14 | + | + | + | |

| 15 | + | + | + | |

| 7 | 16 | + | + | + |

| 17 | − | − | − | |

| 18 | + | + | + | |

| 19 | + | − | + | |

| 20 | + | + | + | |

| 10 | 21 | + | + | + |

| 22 | − | − | − | |

| 23 | − | − | − | |

| 24 | + | − | − | |

| 11 | 25 | + | − | + |

| 26 | + | − | + | |

| 27 | − | − | − | |

| 28 | + | − | − | |

| 29 | + | − | + | |

| No. positive (%) | 19 (65.6) | 11 (37.9) | 17 (58.6) | |

Reference 26.

DISCUSSION

The sequence analysis of PCR products from 17 isolates showed that the isolates could be divided into two groups. One group (genotype A) included five isolates from three outbreaks in Japan and one isolate from a traveler returning from Indonesia. The other group (genotype B) consisted of one isolate from the other outbreak in Japan; four isolates from travelers from Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia; and all of the isolates from Pakistani children. The ELISA with MAb Ai/8 revealed high reactivity only with isolates of genotype A, and this reactivity indicated the presence of a group antigen. RT-PCR using primer sets A and B also revealed nonreactivity with genogroup B viruses. These results suggested that the sequence in the P1 and P2 region of the Aichi virus was more diverse than that of the 3C-3D region analyzed in this study but that the two genogroups were still significantly similar in this region. However, there is no evidence that these genotypic differences affect other diagnostic procedures such as neutralization test or ELISA for detection of Aichi virus antigen (25, 26, 28).

We proposed designating a genotype A and a genotype B of Aichi virus. Following sequencing of 29 PCR products from stool samples in 12 outbreaks, 27 products from 11 outbreaks were classified as genotype A. This information was valuable for confirming the prevalent strain in Japan, where genotype A was suspected to be more prevalent than genotype B by sequence analysis of 17 isolates. In this study, we were able to identify another group (genotype B) which consisted of one isolate from an outbreak in Japan; four of five isolates of travelers from Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia; and all of the isolates from the Pakistani children. By accumulating more sequencing data for Aichi virus RNA, it may be possible to determine even more genotypes. In addition, the prevalence of a certain genotype may be discovered to be related to a specific geographic region.

Outbreaks of gastroenteritis have been associated with the consumption of raw oysters (9, 10, 16, 17, 21). In Japan, infection by a small round virus (Norwalk-like virus) has been reported in several oyster-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks (11, 12, 22, 23). Using RT-PCR, we were able to detect Aichi virus in 12 (32%) of 37 outbreaks in Japan occurring between 1987 and 1998. Aichi virus was not frequently associated with outbreaks between 1991 and 1998, and its clinical importance was not clearly defined in this study. However, the positive rates were greater than 50% in 10 of 12 outbreaks (Table 2). This result suggested the possibility of Aichi virus being an etiological agent of these 10 outbreaks. The observation that 11 of the 12 PCR-positive specimens came from oyster-associated outbreaks suggested a correlation between Aichi virus and seafood pollution. During feeding, shellfish such as oysters can accumulate pathogenic human microorganisms present in sewage-polluted seawater (8). Since the entire shellfish is usually consumed along with the gastrointestinal tract, shellfish may act as passive carriers of microorganisms such as enteric bacteria and viruses. The effective control of enteric bacterial disease spread by shellfish has resulted in the establishment of bacteriological standards using a coliform and fecal coliform index as the basis for a certification program. Improper documentation and an insufficient number of studies related to the transmission of viral disease by shellfish have so far impeded progress in implementing preventive measures (29). In addition, there has been a lack of sensitive techniques to adequately research this problem. RT-PCR can be expected to be a useful tool for detection of Aichi virus in shellfish such as oysters. Furthermore, using the primer set C and pair C94b-246K designated in this study, it will be possible to construct a nested PCR for the detection of Aichi virus RNA from environmental samples such as food and water. Epidemiological studies focusing on the presence of Aichi virus in environmental samples will aid in revealing transmission routes.

Aichi virus RNA was also amplified from nine patients in outbreak 9, which was not associated with oysters (Table 2). This means that Aichi virus can be transmitted by substances other than oysters. The prevalence rate for Aichi virus antibody was found to be 7.2% for persons aged 7 months to 4 years. The prevalence rate for antibody to Aichi virus increased with age, to about 80% in persons 35 years old (26). These results indicated that the Aichi virus is circulating in Japan. However, subclinical infections may be more common than clinically manifest diseases such as those caused by picornaviruses. Many picornaviruses cause several discrete clinical syndromes such as paralysis, aseptic meningitis, respiratory and intestinal illnesses, and hepatitis (1, 18, 31). The same picornavirus may cause more than one syndrome. In our previous study, using ELISA, Aichi virus antigen was detected for only one patient, who was diagnosed with lower respiratory tract illness (26). In this study, RT-PCR was 10,000 times more sensitive than ELISA for detection of purified Aichi virus. The development of RT-PCR for Aichi virus should be of interest for the clinical study of Aichi virus. RT-PCR may be useful for establishing a clinical diagnosis of illnesses including gastroenteritis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Nakib W. Rhinoviruses. In: Zuckerman A J, Banatvala J E, Pattison J R, editors. Principles and practice of clinical virology. 2nd ed. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashley C R, Caul E O, Paver W K. Astrovirus-associated gastroenteritis in children. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31:939–943. doi: 10.1136/jcp.31.10.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blacklow N R. Medical virology of small round gastroenteritis viruses. Med Virol. 1998;9:111–128. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz J R, Bartlett A V, Herrmann J E, Caceres P, Blacklow N R, Cano F. Astrovirus-associated diarrhea among Guatemalan ambulatory rural children. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1140–1144. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1140-1144.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubitt W D. The candidate caliciviruses. Ciba Found Symp. 1987;128:126–143. doi: 10.1002/9780470513460.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukor G, Blacklow N R. Human viral gastroenteritis. Microbiol Rev. 1984;48:157–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.2.157-179.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolin R, Treanor J, Madore H P. Novel agents of viral enteritis in humans. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:365–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerba C P, Goyal S M. Detection and occurrence of enteric viruses in shellfish: a review. J Food Prot. 1978;41:743–754. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-41.9.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill O N, Cubitt W D, McSwiggan D A, Watne B M, Bartlett C L. Epidemic of gastroenteritis caused by oyster contaminated with small round structured viruses. Br Med J. 1983;287:1532–1534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6404.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunn R A, Janowski H T, Lieb S, Prather E C, Greenberg H B. Norwalk virus gastroenteritis following raw oyster consumption. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:348–351. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haruki K, Seto Y, Murakami T, Kimura T. Pattern of shedding of small, round-structured virus particles in stools of patients of outbreaks of food-poisoning from raw oysters. Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1991.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi Y, Ando T, Utagawa E, Sekine S, Okada S, Yabuuchi K, Miki T, Ohashi M. Western blot (immunoblot) assay of small, round-structured virus associated with an acute gastroenteritis outbreak in Tokyo. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1728–1733. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1728-1733.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X, Wang J, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Detection of Norwalk virus in stool by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2529–2534. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2529-2534.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King A M Q, Brown F, Christian P, Hovi T, Hyypia T, Knowles N J, Lemon S M, Minor P D, Palmenberg A C, Skern T, Stanway G. Picornaviridae. In: van Regenmortel M H V, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Carsten E B, Esres M K, Lemon S M, Maniloff J, Mayo M A, McGeoch D J, Pringle C R, Wickner R B, editors. Virus taxonomy: seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1999. p. 996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature (London) 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindberg-Braman A M. Clinical observations on the so-called oyster hepatitis. Am J Public Health. 1965;53:1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackowiak P A, Caraway C T, Portnoy B L. Oyster-associated hepatitis: lessons from the Louisiana experience. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;103:181–191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minor P D, Morgan-Capner P, Schild G C. Enteroviruses. In: Zuckerman A J, Banatvala J E, Pattison J R, editors. Principles and practice of clinical virology. 2nd ed. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishio O, Ishihara Y, Isomura S, Inoue H, Inoue S. Long-term follow-up of infants from birth for rotavirus antigen and antibody in the feces. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1988;30:497–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1988.tb02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numata K, Nakata S, Jiang X, Estes M K, Chiba S. Epidemiological study of Norwalk virus infections in Japan and southeast Asia by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with Norwalk virus capsid protein produced by the baculovirus expression system. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:121–126. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.121-126.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portnoy B L, Mackowiak P A, Caraway C T, Walker J A, McKinley T W, Klein C A., Jr Oyster-associated hepatitis: failure of shellfish certification programs to prevent outbreaks. JAMA. 1975;233:1065–1068. doi: 10.1001/jama.233.10.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine S, Okada S, Hayashi Y, Ando T, Terayama T, Yabuuchi K, Miki T, Ohashi M. Prevalence of small round structured virus infection in acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in Tokyo. Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33:207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugieda M, Nakajima K, Nakajima S. Outbreaks of Norwalk-like virus-associated gastroenteritis traced to shellfish: coexistence of two genotypes in one specimen. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:339–346. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Tsuzuki H, Suzuki Y, Ishikawa N, Takeda N, Miyamura T, Yamazaki S. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of Aichi virus, a distinct member of the Picornaviridae associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. J Virol. 1998;72:8408–8412. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8408-8412.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Kobayashi S, Ishihara Y, Miyake T, Agboatwalla M, Isomura S. Isolation of cytopathic small round virus (Aichi virus) from Pakistani children and Japanese travelers from Southeast Asia. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:433–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Ishihara Y, Isomura S, Utagawa E. Prevalence of newly isolated, cytopathic small round virus (Aichi strain) in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2938–2943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2938-2943.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita T, Kasuya S, Noda S, Nagano I, Ohtsuka S, Ohtomo H. Newly isolated strains of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in Japan identified by using monoclonal antibodies to Karp, Gilliam, and Kato strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1859–1860. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1859-1860.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita T, Kobayashi S, Sakae K, Nakata S, Chiba S, Ishihara Y, Isomura S. Isolation of cytopathic small round viruses with BS-C-1 cells from patients with gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:954–957. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Ishihara Y, Isomura S. A 2-year survey of the prevalence of enteric viral infections in children compared with contamination in locally-harvested oysters. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;108:155–163. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita T, Sakae K, Ishihara Y, Isomura S, Totsuka A, Moritsugu Y. Family-acquired hepatitis A—prevalence of hepatitis A among the family in Aichi Prefecture, 1990. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis. 1992;66:781–785. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.66.781. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckerman A J. Hepatitis A and non-A, non-B hepatitis (hepatitis C; hepatitis E) In: Zuckerman A J, Banatvala J E, Pattison J R, editors. Principles and practice of clinical virology. 2nd ed. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]