Abstract

In response to growing evidence of associations between harmful masculinities and adverse health outcomes, researchers developed the Man Box Scale to provide a standardized measure to assess these inequitable gender attitudes. In 2019, we evaluated the psychometric properties of the 17-item Man Box Scale and derived a 5-item short form. Using previously collected data (in 2016) from men aged 18–30 years across the United States (n = 1328), the United Kingdom (n = 1225), and Mexico (n = 1120), we conducted exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), assessed convergent validity by examining associations of the standardized mean Man Box Scale score with violence perpetration, depression, and suicidal ideation, and assessed internal consistency reliability of the full scale. We used item response theory (IRT) to derive a 5-item short form, and conducted CFA and additional assessments for reliability and convergent validity. We identified a single underlying factor with 15 items across all three countries. CFA resulted in good model fit. We demonstrated significant associations of standardized mean Man Box Scale score with violence perpetration (OR range = 1.57–5.49), depression (OR range = 1.19–1.73), and suicidal ideation (OR range = 1.56–2.59). IRT resulted in a 5-item short form with good fit through CFA and convergent validity, and good internal consistency. The Man Box Scale assesses harmful masculinities and demonstrates strong validity and reliability across three diverse countries. This scale, either short or long forms, can be used in future prevention research, clinical assessment and decision-making, and intervention evaluations.

Keywords: Survey research, Violence prevention, Masculinities

1. Introduction

There is strong evidence that young men who subscribe to inequitable gender norms (e.g., believe women are solely responsible for household chores and child-rearing) (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008) and endorse dominant and hostile forms of masculinities (e.g., believe women are sexual conquests) (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008) have higher rates of perpetrating psychological, physical, and sexual violence against women (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Jewkes et al., 2011; Malamuth et al., 1995; Parrott and Zeichner, 2003; Good et al., 1995; Schwartz et al., 2005; Copenhaver et al., 2000; Eisler et al., 2000; Jakupcak et al., 2002; Barker et al., 2011). Violence against women is a global health epidemic in which one in three women are impacted during their lifetime, leading to adverse health outcomes, such as depression, sexually transmitted infections, and exacerbation of chronic health conditions (World Health Organization, 2013). Research also shows emerging evidence of an association between “harmful masculinities” and perpetrating verbal and physical abuse, cyber bullying, and aggression towards gay, lesbian, and transgender people or those who do not conform to hetero-normative gender norms (Leemis et al., 2018; Steinfeldt et al., 2012; Leone and Parrott, 2015; Parrot, 2009; Vincent et al., 2011; Kelley and Gruenewald, 2015; Reidy et al., 2009; Espelage et al., 2018). Furthermore, studies have explored the impact of “harmful masculinities” on the health of the individual who endorses them, including poor care-seeking behaviors, and mental and sexual health outcomes (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Barker et al., 2011; Barker, 2000; Rivers and Aggleton, 1999; Addis, 2008; Barker and Ricardo, 2005; American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018; Jakupcak et al., 2017; Courtenay, 2000; Oliffe, 2009; Cho and Kogan, 2017). A recent study estimated that eliminating these hegemonic masculine norms could save the United States (U.S.) economy $15.7 billion (Heilman et al., 2019).

Recently, the association between “harmful masculinities” and health gained widespread media attention in response to the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men (American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018). These guidelines underscore the idea that men’s lives are complex, encouraging healthcare professionals to address health problems that disproportionately impact men. These guidelines also highlight the nuanced intersections of culture, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, power, and health, all of which contribute to “masculinities” (American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018).

We define “masculinities” as the “plural and dynamic ways in which masculine norms, attitudes, identities, power dynamics, and behaviors are lived” (Ragonese et al., 2018). Harmful masculinities, on the other hand, are detrimental beliefs that perpetuate rigid, hetero-normative, violent, and controlling norms about what a “real man” is (Heilman and Barker, 2018). Improving collective understanding of how harmful masculinities manifest in society and impact health is essential to resolve widespread gender inequities (Heilman and Barker, 2018). However, researchers have not reached consensus on how this construct should be measured. Variability exists in the psychometric validity of the scales used to investigate masculine norms (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Barker et al., 2011; Cho and Kogan, 2017; Levant et al., 2013). In the U.S., the Male Role Norms Inventory (MRNI) has been validated in its original, revised, short, very brief, and adolescent forms in multiple studies (Levant et al., 2013; Levant and McCurdy, 2018; Gerdes et al., 2018; McDermott et al., 2019; Levant et al., 2016a; Levant et al., 2016b). Recent research evaluating these studies called for further exploration of masculine norms among more diverse populations (Gerdes et al., 2018; Levant and McCurdy, 2018). Globally, the Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale has been implemented in developing countries (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Vu et al., 2017; Pulerwitz et al., 2015; Pulerwitz et al., 2012). There is a need to build on existing research to evaluate a parsimonious scale that yields valid and reliable assessment across a large, heterogenous, cross-cultural sample from multiple countries, particularly among young men where opportunities for intervention may be more successful. Such a scale can inform research design, allow for comparisons across studies, and help evaluate interventions to prevent the harms associated with rigid gender norms. Furthermore, while adherence to harmful masculinities has not been routinely assessed in clinical settings, such a scale may allow for clinicians to monitor and manage associated poor health outcomes.

To address this knowledge gap, researchers at Promundo-US, a global applied research organization, created the Man Box Scale with Axe Unilever as part of a community campaign on promoting healthy masculinity across diverse settings (Heilman et al., 2017). The terminology, “Man Box,” is derived from Paul Kivel’s “Act Like a Man Box,” depicting societal pressures felt by men constrained by traditional masculine norms (Kivel, 1998). The term has since been adapted and popularized (Porter, 2016). We define “Man Box” as “a set of beliefs, communicated by parents, families, the media, peers, and other members of society, that place pressure on men to be a certain way” (Heilman et al., 2017). The content of the Man Box Scale is grounded in social norms and gender theories, as well as gender equity research and programming (Heilman et al., 2017). The 17-item scale contained items related to theoretically- and empirically-derived aspects of masculine norms, including self-sufficiency, acting tough, physical attractiveness, rigid masculine gender roles, heterosexuality and homophobia, hypersexuality, and aggression and control (Heilman et al., 2017). Items were derived from decades of work implementing and adapting the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) and the GEM Scale (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Barker et al., 2011; Heilman et al., 2017). Through an iterative and collaborative process, Promundo-US piloted and field-tested over 100 items in more than 30 countries; the final 17 items were selected by key stakeholders, including content experts in gender and masculinities research, in-country partners, and the funder. The Man Box Scale has strong theoretical, empirical, and cross-cultural roots, but has yet to be psychometrically validated. Psychometric validation is important for widespread adoption and measurement of harmful masculinities, which is of increasing importance given numerous calls for prevention interventions in this area.

We evaluated elements of validity and reliability of the 17-item Man Box Scale by using a large sample of young adult men in the U.S., United Kingdom (U.K.), and Mexico. Addressing the need for short and easy-to-administer items, particularly as part of intervention studies, we also aimed to create a short form Man Box Scale that yields valid and reliable scores.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This is a secondary analysis of data from a cross-sectional survey, conducted among men aged 18–30 years (N = 3673) across the U.S. (n = 1328), U.K. (n = 1225), and Mexico (n = 1120). The original survey sought to better understand the prevalence of harmful masculinities among younger men in the context of widespread social change, and was built on previous work with collaborators in three countries (Heilman et al., 2017; Ruxton, 2002; Robb, 2007; Kimmel, 2008; Way, 2011; Guillermo, 2006; De Keijzer, 2001). Kantar TNS (2019) a global data company, led recruitment procedures using a purposive sampling strategy with quotas based on census information to achieve diverse sociodemographic representation. They sent email invitations to potential participants who had provided informed consent to be contacted regarding future surveys as part of an online panel. The online survey (available in English or Spanish) took participants about 20 min to complete, and included the Man Box Scale and demographic and health status questions. Kantar TNS conducted translation procedures, piloted surveys with 100 participants in each country, and made small adjustments to improve cultural appropriateness and correct errors in translation. Data were collected between September–October 2016. As an anonymous survey as part of a community campaign, the original Man Box survey did not meet the definition of human subjects’ research in the federal regulations at 45 CFR 46.102 (d). The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board also determined that the secondary analysis presented here did not meet the definition of human subjects’ research and thus did not require IRB review and approval.

2.2. Measures

The 17-item Man Box Scale was developed to measure men’s personal beliefs. Participants marked their agreement with each item (4-point Likert-type scale: 1-strongly disagree, the most gender-equitable; 2-disagree; 3-agree; 4-strongly agree, the least gender-equitable). We re-coded the scale 0–3 to ease interpretability of results.

For convergent validity, we included past-month violence-related outcomes: perpetration of verbal bullying, online bullying, physical bullying, and sexual harassment (4-point Likert-type scale: not at all, infrequently, often, and very often), using single measures adapted by content experts from previous literature (Table A.1) (Straus et al., 1996; Ybarra et al., 2007; Bennet et al., 2011; Cantor et al., 2019). For analyses, we dichotomized outcomes as any (infrequently to very often) or none. We also included items from The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) to assess depression and one item to assess suicidal ideation (i.e., “having thoughts of suicide”) over the past two weeks (Kroenke et al., 2003). For analyses, we dichotomized the PHQ-2 (total score 0–2 = not at risk for depression, 3–6 = at risk for depression) and suicidal ideation (“not at all” vs. “some days”/“more than half the day”/“almost every day”).

2.3. Statistical analyses

In 2019, we randomly divided each country’s sample in half, using one half for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the other for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We conducted the EFA and CFA for each country individually. For the EFA samples, we determined the underlying factor structure by reviewing Eigenvalues, scree plots, and parallel analyses. The method of factor analysis was principal components. We used oblique rotation to observe correlation patterns between each item and each underlying latent variable. We considered removing items with a factor loading < 0.4 in any country, indicating that the item was not strongly correlated with an identified factor. We required consensus among the research team prior to item removal. Using each country’s CFA sample, we estimated goodness-of-fit by reviewing values for root-mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Good fit was considered as RMSEA < 0.06, CFI > 0.95, TLI > 0.95, and SRMR < 0.08 (Satorra and Bender, 1994; Hu and Bender, 1999). EFA and CFA were conducted in Mplus (Version 8); items were specified as ordinal factor indicators with weighted least square mean and variance adjusted estimation. All analyses were repeated by treating items as continuous variables.

Based on factor analyses, the Man Box Scale was calibrated using Item Response Theory (IRT) fitted with a graded response model (GRM), designed for ordinal factor indicators, on the entire sample across all countries (StataCorp, 2017). IRT is used to evaluate items and identify ways to refine the scale to improve accuracy and reduce redundancy (StataCorp, 2017). We examined each item’s difficulty, discrimination, and item characteristic curve (ICC). Item difficulty estimates the point at which the probability of a participant answering “correctly” is 50% (An and Yung, 2014). Items with higher discrimination values have greater probability of differentiating among responses (An and Yung, 2014). The ICC graphically represents an item’s difficulty and discrimination parameters. IRT models assumed unidimensionality, as we had identified a single factor solution through factor analyses. All IRT analyses were conducted in Stata/SE (Version 15.1).

After refining the structure of the Man Box Scale, we tested for convergent validity by examining the association of the Man Box Scale with violence perpetration, depression, and suicidal ideation. We selected these outcomes because they are theoretically related to the construct we intended to measure (i.e., the Man Box Scale is theoretically positively associated with perpetration of violence and poor mental health) (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Jewkes et al., 2011; Malamuth et al., 1995; Parrott and Zeichner, 2003; Good et al., 1995, Schwartz et al., 2005; Copenhaver et al., 2000; Eisler et al., 2000; Jakupcak et al., 2002; Barker et al., 2011; Addis, 2008). We used unadjusted logistic regression to examine the relationship between the standardized mean summary score on the Man Box Scale and the four violence-related outcomes mentioned above, as well as depression and suicidal ideation (in separate models). We also calculated odds ratios adjusting for age, relationship status, employment, and sexual orientation, which were consistently measured across countries. Afterwards, we assessed internal consistency reliability using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.

Finally, we derived a short form by selecting the best performing items based on items’ discrimination, difficulty, item characteristic curve, and content importance. The final scale included items with highest discrimination. While we intended to have one item from each theoretically and empirically-identified aspect of masculine norms, we dropped items related to a norm if none of the items had a discrimination value higher than the lowest of other norms. Decisions on final item inclusion were made by team consensus and based on feasibility (i.e., final length of the survey) and theoretical foundation. We measured reliability through total information functions. After establishing the short form, we conducted CFA and convergent validity analyses (as previously described) with the full sample from each country. Finally, we determined the Pearson correlation coefficients between the standardized mean summary scores of the short and long forms of the Man Box Scale.

3. Results

We present demographic data in Table 1. Approximately half the sample were younger than 25 years old. The sample from the U.S. represented diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (47.4% white, 16.6% Black, 13.9% Hispanic/Latino, 19.6% Asian, 2.5% Other). The majority of the participants in the U.K. identified as white (67.8%). Surveyors did not assess race/ethnicity in Mexico. The most commonly reported employment status was full time employment. The majority of respondents (72.0%) reported some level of post-secondary training. In the U.S. and U.K., most respondents (> 49.9%) reported being single. In Mexico, 38.0% of participants noted that they were dating someone, while 33.9% said they were single. The vast majority (> 87.0%) identified as heterosexual.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Demographic variable | Total sample % (n) (n = 3673) |

United States % (n) (n = 1328) |

United Kingdom % (n) (n = 1225) |

Mexico % (n) (n = 1120) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 50.8% (1865) | 50.3% (668) | 48.6% (595) | 53.8% (602) |

| 25–30 | 49.2% (1808) | 49.7% (660) | 51.4% (630) | 46.2% (518) |

| Education level | ||||

| Less than high school | 3.1% (113) | 5.3% (70) | 1.1% (13) | 2.7% (30) |

| High school/secondary school | 24.9% (916) | 21.1% (280) | 13.7% (168) | 41.8% (468) |

| College/vocational training | 72.0% (2644) | 73.6% (978) | 85.2% (1044) | 55.5% (622) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed full time | 50.7% (1863) | 49.8% (662) | 55.8% (684) | 46.2% (517) |

| Employed part time | 12.8% (469) | 12.7% (182) | 10.9% (134) | 13.7% (153) |

| Unemployed | 10.8% (398) | 14.1% (187) | 11.8% (144) | 6.0% (67) |

| Student | 21.5% (789) | 20.4% (271) | 18.8% (230) | 25.7% (288) |

| Freelance/Consultant/Contractor | 3.4% (125) | 1.4% (18) | 2.0% (24) | 7.4% (83) |

| Other | 0.8% (29) | 0.6% (8) | 0.7% (9) | 1.1% (12) |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single/not dating | 46.4% (1703) | 53.6% (712) | 49.9% (611) | 33.9% (380) |

| Dating | 29.9% (1099) | 23.4% (311) | 29.6% (362) | 38.0% (426) |

| Married | 20.4% (750) | 21.2% (281) | 18.4% (226) | 21.7% (243) |

| Other | 3.3% (121) | 1.8% (24) | 2.1% (26) | 6.3% (71) |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 87.8% (3139) | 87.7% (1139) | 87.5% (1038) | 88.3% (962) |

| Homosexual/Gay | 6.2% (221) | 6.3% (82) | 6.1% (72) | 6.2% (67) |

| Bisexual | 4.5% (160) | 4.5% (58) | 4.3% (51) | 4.7% (51) |

| Other | 1.5% (54) | 1.5% (20) | 2.1% (25) | 0.8% (9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | – | 47.4% (630) | 67.8% (830) | – |

| Black | – | 16.6% (220) | 9.8% (120) | – |

| Hispanic/Latino | – | 13.9% (184) | – | – |

| Asian | – | 19.6% (261) | 18.0% (220) | – |

| Othera | – | 2.5% (33) | 4.5% (55) | – |

| Annual household income | ||||

| Less than $40,000 | – | 35.4% (470) | – | – |

| $40,000 or more | – | 64.6% (858) | – | – |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Lowest categories | – | – | 48.6% (595) | 81.8% (916) |

| Highest categories | – | – | 51.4% (630) | 18.2% (204) |

US other race/ethnicity: American Indian, Inuit or Aleut, Pacific islander, or some other ethnic background; UK other race/ethnicity: Gypsy or Irish Traveler, White and Black Caribbean, White and Black African, White and Asian, any other mixed/multiple ethnic background, Arab, or any other ethnic group; race/ethnicity was not assessed in Mexico. Household income was measured for US, socioeconomic status was measured for UK and Mexico.

3.1. Factor analyses

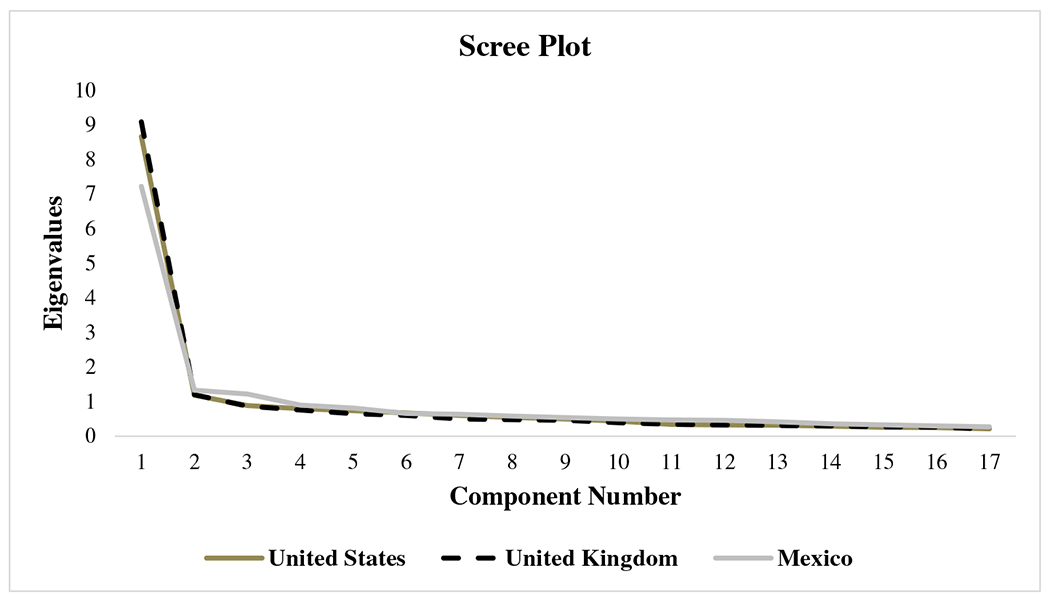

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin values were > 0.9, indicating adequate sample size for factor analysis; Bartlett’s test of sphericity across samples revealed p < 0.0001. The EFA resulted in a single factor solution in each country (Table 2), as shown by the scree plot (Fig. 1) and confirmed by parallel analyses. The ratio of the first two Eigenvalues were 8.66:1.18 for U.S., 9.09:1.20 for U.K, and 7.22:1.33 for Mexico. (Reeve et al., 2007) All items loaded strongly (> 0.4) onto one factor across all countries, except two items: “In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal”; and “In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin.” We removed these items for the remaining analyses, resulting in a 15-item scale.

Table 2.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the Man Box Scale across three countries using ordinal factor indicators.

| Item | Exploratory factor loadings |

Confirmatory factor loadings |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. (n = 664) |

U.K. (n = 612) |

Mexico (n = 560) |

U.S.A. (n = 664) |

U.K. (n = 613) |

Mexico (n = 560) |

|

| 1. In my opinion, a man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect. | 0.802 | 0.794 | 0.622 | 0.782 | 0.754 | 0.680 |

| 2. In my opinion, it is not good for a boy to be taught how to cook, sew, clean the house and take care of younger children. | 0.816 | 0.807 | 0.729 | 0.753 | 0.754 | 0.703 |

| 3. In my opinion, a gay guy is not a “real man”. | 0.739 | 0.782 | 0.715 | 0.728 | 0.730 | 0.694 |

| 4. In my opinion, a real man should have as many sexual partners as he can. | 0.786 | 0.756 | 0.790 | 0.765 | 0.785 | 0.784 |

| 5. In my opinion, a guy who doesn’t fight back when others push him around is weak. | 0.648 | 0.703 | 0.615 | 0.611 | 0.649 | 0.477 |

| 6. In my opinion, a man shouldn’t have to do household chores. | 0.866 | 0.841 | 0.793 | 0.869 | 0.822 | 0.802 |

| 7. In my opinion, guys should act strong even if they feel scared or nervous inside. | 0.533 | 0.640 | 0.509 | 0.596 | 0.574 | 0.423 |

| 8. In my opinion, it is very hard for a man to be successful if he doesn’t look good. | 0.451 | 0.550 | 0.483 | 0.476 | 0.509 | 0.395 |

| 9. In my opinion, a real man would never say no to sex. | 0.771 | 0.766 | 0.687 | 0.771 | 0.714 | 0.576 |

| 10. In my opinion, men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women. | 0.700 | 0.732 | 0.682 | 0.687 | 0.709 | 0.666 |

| 11. In my opinion, men should use violence to get respect if necessary. | 0.801 | 0.824 | 0.770 | 0.820 | 0.809 | 0.782 |

| 12. In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal.a,b | −0.387 | −0.308 | −0.329 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 13. In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin.b | 0.530 | 0.577 | 0.315 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 14. In my opinion, men should figure out their personal problems on their own without asking others for help. | 0.715 | 0.759 | 0.542 | 0.719 | 0.726 | 0.510 |

| 15. In my opinion, a man should always have the final say about decisions in his relationship or marriage. | 0.791 | 0.804 | 0.685 | 0.809 | 0.799 | 0.709 |

| 16. In my opinion, a guy who spends a lot of time on his looks isn’t very manly. | 0.662 | 0.655 | 0.587 | 0.676 | 0.582 | 0.547 |

| 17. In my opinion, if a guy has a girlfriend or a wife, he deserves to know where she is all the time. | 0.652 | 0.683 | 0.634 | 0.645 | 0.752 | 0.635 |

Reverse-coded question.

Items were removed from final scale because factor loadings < 0.4 in at least one country.

Fig. 1.

Scree plots for the Man Box Scale.

Scree plot demonstrating the resulting Eigenvalues from the exploratory factor analysis for the United States, United Kingdom, and Mexico samples.

We performed single-factor CFAs on the 15-item scale for each country, using the second half of the samples. The 15-item scale demonstrated good evidence of single factor solution with all factor loadings > 0.4 (Table 2). Fit indices (Table 3) were strong. For example, in the U.K. (n = 613), RMSEA = 0.067, CFI = 0.978, TLI = 0.975, and SRMR = 0.033. Continuous analyses show similar results (Table A.2). Mean values and total item scores are presented (Table A.3).

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis across three countries.

| Country | Goodness-of-fit statistics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEA |

CFI | TLI | SRMR | ||

| Value | 90% CI | ||||

| 15-item man box scale | |||||

| U.S.A (n = 664) | 0.075 | 0.068–0.082 | 0.970 | 0.965 | 0.037 |

| U.K. (n = 613) | 0.067 | 0.059–0.075 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.033 |

| Mexico (n = 560) | 0.071 | 0.063–0.079 | 0.958 | 0.951 | 0.045 |

| 5-item short form man box scale | |||||

| U.S.A (n = 664) | 0.071 | 0.042–0.103 | 0.995 | 0.991 | 0.014 |

| U.K. (n = 613) | 0.021 | 0.000–0.063 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.008 |

| Mexico (n = 560) | 0.040 | 0.000–0.078 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.013 |

CI = confidence interval; indications of good fit: RMSEA (Root mean squared error of approximation) < 0.06, CFI (Comparative fit index) > 0.95, TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) > 0.95, SRMR (Standardized root mean squared residual) < 0.08.

3.2. Item response theory

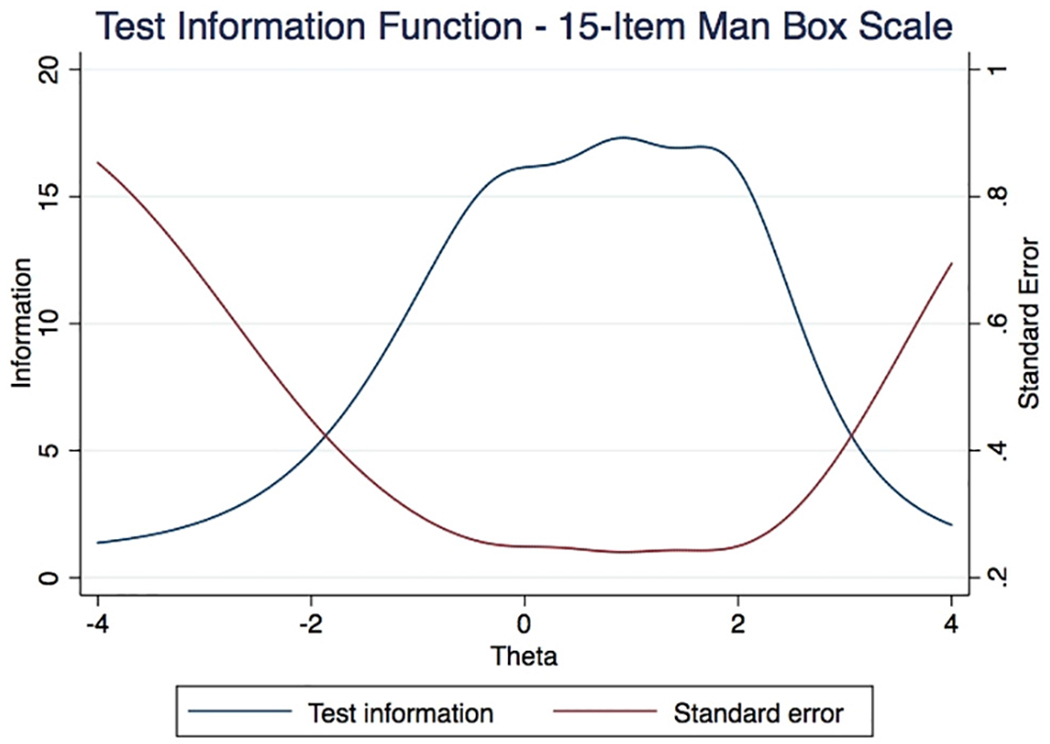

We determined a range of discrimination and difficulty parameters for the 15 items for the entire sample across all countries (Table A.4). Discrimination values ranged from 1.01 through 2.97. Difficulty parameters ranged from −1.96 through 2.53. The scale’s total information function was broadly distributed, measuring the underlying latent trait from −2 through 3.5 (Fig. A.1).

3.3. Convergent validity and reliability

The Man Box Scale standardized mean summary scores for the 15 items were significantly associated with all violence-related outcomes, as well as depression and suicidal ideation (Table 4). Within each country, participants with a higher standardized mean summary Man Box Scale score (i.e., endorsing less equitable beliefs) had significantly higher odds of perpetrating verbal, online, and physical bullying, as well as sexual harassment (OR range = 1.57–5.49). Individuals with a higher standardized mean summary Man Box Scale score also had significantly higher odds of being at risk for depression (OR range = 1.19–1.73) and experiencing suicidal ideation (OR range = 1.56–2.59). Odds ratios remained significant after adjusting for age, relationship status, employment, and sexual orientation. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the U.S. and U.K. were > 0.9. In Mexico, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.89.

Table 4.

Convergent validity: Man Box Scale standardized mean summary score and violence perpetration and mental health.

| Dependent variables | Independent variable: Man box scale standardized mean summary score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.A |

U.K. |

Mexico |

||||

| OR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| 15-item man box scale | ||||||

| Past month perpetration | ||||||

| Verbal bullying | 2.88 (2.49–3.32) | 2.96 (2.55–3.44) | 2.83 (2.44–3.28) | 2.74 (2.36–3.19) | 1.57 (1.38–1.78) | 1.55 (1.36–1.77) |

| Online bullying | 5.04 (4.17–6.09) | 5.60 (4.58–6.85) | 4.90 (4.05–5.93) | 4.68 (3.86–5.68) | 2.33 (1.97–2.76) | 2.25 (1.90–2.67) |

| Physical bullying | 5.49 (4.51–6.69) | 6.02 (4.88–7.43) | 5.15 (4.24–6.26) | 5.00 (4.10–6.10) | 2.49 (2.10–2.96) | 2.46 (2.06–2.93) |

| Sexual harassment | 4.70 (3.91–5.64) | 5.03 (4.15–6.11) | 5.38 (4.41–6.56) | 5.11 (4.19–6.25) | 2.65 (2.24–3.14) | 1.68 (2.25–3.20) |

| Mental health | ||||||

| PHQ-2 | 1.63 (1.45–1.84) | 1.70 (1.50–1.92) | 1.73 (1.52–1.95) | 1.82 (1.59–2.07) | 1.19 (1.03–1.37) | 1.23 (1.06–1.42) |

| Suicidal ideation | 2.17 (1.90–2.48) | 2.37 (2.05–2.73) | 2.59 (2.24–2.99) | 2.73 (2.34–3.17) | 1.56 (1.33–1.83) | 1.64 (1.39–1.94) |

| 5-item short form man box scale | ||||||

| Past month perpetration | ||||||

| Verbal bullying | 3.06 (2.64–3.54) | 3.13 (2.69–3.63) | 2.96 (2.56–3.42) | 2.86 (2.47–3.32) | 1.49 (1.31–1.69) | 1.47 (1.30–1.68) |

| Online bullying | 5.38 (4.46–6.50) | 5.88 (4.82–7.18) | 5.34 (4.42–6.45) | 5.18 (4.26–6.29) | 2.44 (2.07–2.86) | 2.37 (2.01–2.80) |

| Physical bullying | 5.55 (4.58–6.73) | 6.01 (4.91–7.36) | 5.08 (4.22–6.12) | 4.96 (4.10–6.00) | 2.54 (2.16–3.00) | 2.52 (2.13–2.98) |

| Sexual harassment | 5.09 (4.23–6.11) | 5.37 (4.44–6.51) | 5.67 (4.66–6.89) | 5.37 (4.41–6.53) | 2.56 (2.18–3.01) | 2.57 (2.18–3.02) |

| Mental health | ||||||

| PHQ-2 | 1.63 (1.45–1.83) | 1.68 (1.49–1.90) | 1.72 (1.53–1.95) | 1.79 (1.58–2.04) | 1.21 (1.06–1.40) | 1.25 (1.08–1.43) |

| Suicidal ideation | 2.23 (1.96–2.54) | 2.39 (2.08–2.74) | 2.78 (2.41–3.21) | 2.89 (2.49–3.36) | 1.62 (1.40–1.89) | 1.69 (1.45–1.98) |

We calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between the independent variable, 15-item (or 5-item Man Box Scale) standardized mean summary scores, and the dependent variables, past month bullying perpetration (dichotomized to “any” or “none”), as well as the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (dichotomized as not at risk for depression (total score = 0–2) vs. at risk for depression (total score = 3–6)) and suicidal ideation (dichotomized to “any” or “none”). We also calculated odds ratios and 95%CI, adjusting for age, relationship status, employment and sexual orientation (aOR).

3.4. Short form development

To create the short form, we retained the highest performing items (highest discrimination) related to rigid masculine gender norms, aggression and control, hypersexuality, self-sufficiency, and heterosexuality and homophobia to balance feasibility, psychometric accuracy, and theoretical rigor. As a result, the short form includes (aspect of harmful masculinity in parentheses):

In my opinion, a man shouldn’t have to do household chores (rigid masculine gender roles).

In my opinion, men should use violence to get respect if necessary (aggression and control).

In my opinion, a real man should have as many sexual partners as he can (hypersexuality).

In my opinion, a man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect (self-sufficiency).

In my opinion, a gay guy is not a “real man” (heterosexuality and homophobia).

Discrimination values ranged from 1.99 through 2.97. CFA results were similar for both the short and long form scales (Table 3). The short form had strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.85, 0.85, and 0.80 for the U.S., U.K., and Mexico, respectively). The short form’s total information function was broadly distributed, measuring the underlying latent trait from −1.5 through 3.0. Additionally, the short form had significant associations with the four violence perpetration outcomes, demonstrating convergent validity (OR range = 1.49–5.55). Furthermore, this scale was significantly associated with depression (OR range = 1.21–1.72) and suicidal ideation (OR range = 1.62–2.78). Odds ratios remained significant after adjusting for aforementioned covariates (Table 4). The Pearson correlation coefficients between the long and short forms are 0.94, 0.94, and 0.89 for U.S., U.K, and Mexico, respectively.

4. Discussion

We evaluated the psychometric properties of the Man Box Scale, and identified a measure that yields valid and reliable scores that assess personal attitudes regarding harmful masculinities among adult men in the U.S., U.K., and Mexico. We demonstrated construct validity through EFA and CFA and convergent validity through assessing associations with violence perpetration, depression, and suicidal ideation. While other scales exist to measure masculine gender norms (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Jewkes et al., 2011; Barker et al., 2011; Levant et al., 2013), this is the first unidimensional scale that can be applied to future research examining the relationship between harmful masculinities and health outcomes across multiple cultures.

The Man Box Scale provides several favorable advantages in comparison to existing scales. First, the full form offers an evaluation of harmful masculinities across several empirically and theoretically derived domains. Second, the scale consists of only 15 items, improving feasibility across research and programming. Third, we gathered validity evidence for the scale using a large sample from three countries. Many scales measuring masculine norms have been applied in different countries yet have only provided validity evidence from relatively homogenous populations (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Gerdes et al., 2018; Vu et al., 2017). Fourth, this scale, similar to the GEM Scale (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008), was derived from and developed with the intention of being used in public health programming to prevent and reduce violence and improve associated health outcomes. Notably, the Man Box Scale differs from the GEM Scale in that it has been updated with existing evidence and theory and is less focused on sexual and reproductive health. Fifth, we were able to further refine the Man Box Scale into a short form, consisting of the highest performing items across five masculine norms, offering further parsimony to improve usability.

While the original items were derived from several domains thought relevant to attitudes and behaviors about masculinities (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Barker et al., 2011; Heilman et al., 2017), our analysis of the Man Box Scale shows that we are measuring a single construct. Our total information functions, the reliability component of the IRT analysis, demonstrated that our retained items both in the long and short forms broadly cover one underlying latent variable, which measures of set of gender inequitable attitudes. Furthermore, we noted that two items in the initial 17-item scale did not consistently load across all three countries. The first, “In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal,” loaded poorly across all countries, indicating poor fit with our construct. This was the only positively framed item, potentially resulting in acquiescence bias in which respondents continued to select answers in the same pattern throughout the survey (Krosnick, 1999). This item is also different from other items as it discusses friendship rather than personal identity; respondents may agree that being friends with someone who identifies as gay is acceptable, but still may not view gay men as “real men.” The second item that we excluded from the final version, “In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin,” loaded in the U.S. and U.K., but not in Mexico, indicating that physical attractiveness may vary across cultures. Items related to physical attractiveness have not been included in previous scales measuring gender norms and are not as strongly grounded in existing conceptual frameworks (Pulerwitz and Barker, 2008; Barker et al., 2011; Levant et al., 2013).

Limitations include the use of cross-sectional data, limiting causal inference. We used data from three countries, but are unable to generalize to others. While our sample includes representation across diverse racial/ethnic and educational backgrounds, it is not nationally representative. For example, participant rates of suicidal ideation and depression were higher than national estimates (Bose et al., 2018; McManus et al., 2016; Slone et al., 2006). Yet many national surveys are face-to-face surveys, which underreport true prevalence (Bose et al., 2018; McManus et al., 2016; Slone et al., 2006). Our target population was young men aged 18–30 years of age. Despite knowing that adolescent boys also endorse harmful masculine norms (Vu et al., 2017; Brush and Miller, 2019; Miller et al., 2019), we were restricted to young adults given the original survey’s informed consent procedures. More research is needed to determine if this scale is valid in additional settings, with younger populations and across all genders. In our convergent validity analysis, our violence-related outcomes were limited to single items as a result of feasibility constraints (i.e. balancing survey length with diminished reliability and acquiescence bias). Finally, while we conducted several analyses supporting the Man Box scale’s validity, we did not test measurement invariance.

Clinically, the Man Box Scale, particularly the short form, could be used in symptom management efforts. By tracking patients’ Man Box Scale scores, clinicians may gain insight into how an individual’s identity is impacted by societal pressures and their relationships with others, and identify key opportunities for intervention. This may lead to improvements in associated health outcomes (e.g., depression and suicidality), through mechanisms such as strengthening care-seeking behaviors, decreasing internalization of stigma, and addressing limitations in existing gender-sensitive care for men and boys (American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018; Mahalik et al., 2012; Addis and Mahalik, 2003; Vogel et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2011; Vogel et al., 2007). Further research should examine the feasibility of using the Man Box Scale in clinical settings and explore the utility of developing targeted psycho-educational materials in shifting gender attitudes and improving health outcomes. Epidemiologically, the Man Box Scale could be used to track population-level changes in harmful masculinities over time. This would be helpful to better understand the effectiveness of implementing gender equitable policies or gender transformative prevention programs. Furthermore, by tracking shifts in the Man Box Scale, experts could determine if and how fluctuations in attitudes related to harmful masculinities impact sustained changes in health outcomes.

5. Conclusion

Harmful masculinities impact the health of all genders, yet these norms are not being evaluated in a standardized and systematic way. The Man Box Scale offers a valid and reliable measurement tool to enhance research on gender equity. By improving measurement, this scale may be useful in clinical, programmatic, or epidemiological settings to identity intervention opportunities to prevent harmful attitudes from developing and help mitigate associated adverse health consequences.

Funding

The original Man Box study was funded by Axe Unilever. This work was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism are both a part of the National Institutes of Health (Award Numbers TL1R001858 to Hill (PI: Kevin Kraemer, MD MSc) and K01AA027564 to Coulter). The content is solely the responsibilities of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the funding agencies. The funding agencies did not have a role in study design, data collection, data interpretation or analysis, report writing, or the decision to submit for publication.

Appendix A

Table A.1.

Outcome variables measured in the initial survey.

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Perpetration | |

| Verbal bullying | You made jokes about someone, teased someone, or called someone names that they did not like, for any reason |

| Online bullying | You insulted someone, posted photos meant to embarrass someone, or made threats to someone on SMS, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, or another app or website |

| Physical bullying | You physically hurt someone on purpose by pushing them down, kicking them, or hitting them with a hand, clenched fist, object, or weapon |

| Sexual harassment | You made sexual comments to a woman or girl you didn’t know, in a public place, like the street, your workplace, your school/university, or in an internet or social media place |

From the Man Box Report (Heilman B, Barker G, Harrison A. The Man Box: A Study on Being a Young Man in the US, UK, and Mexico. Washington, DC and London: Promundo-US and Unilever. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TheManBox-Full-EN-Final-29.03.2017-POSTPRINT.v3-web.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed December 2018.)

Table A.2.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the Man Box Scale across three countries using continuous factor indicators.

| Item | Exploratory factor loadings |

Confirmatory factor loadings |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. (n = 664) |

U.K. (n = 612) |

Mexico (n = 560) |

U.S.A. (n = 664) |

U.K. (n = 613) |

Mexico (n = 560) |

|

| 1. In my opinion, a man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect. | 0.750 | 0.744 | 0.561 | 0.733 | 0.702 | 0.620 |

| 2. In my opinion, it is not good for a boy to be taught how to cook, sew, clean the house and take care of younger children. | 0.751 | 0.741 | 0.644 | 0.690 | 0.696 | 0.619 |

| 3. In my opinion, a gay guy is not a “real man”. | 0.672 | 0.721 | 0.640 | 0.661 | 0.668 | 0.635 |

| 4. In my opinion, a real man should have as many sexual partners as he can. | 0.732 | 0.698 | 0.709 | 0.709 | 0.730 | 0.703 |

| 5. In my opinion, a guy who doesn’t fight back when others push him around is weak. | 0.590 | 0.650 | 0.560 | 0.565 | 0.600 | 0.419 |

| 6. In my opinion, a man shouldn’t have to do household chores. | 0.808 | 0.789 | 0.705 | 0.810 | 0.766 | 0.718 |

| 7. In my opinion, guys should act strong even if they feel scared or nervous inside. | 0.464 | 0.580 | 0.449 | 0.521 | 0.514 | 0.357 |

| 8. In my opinion, it is very hard for a man to be successful if he doesn’t look good. | 0.415 | 0.503 | 0.421 | 0.442 | 0.470 | 0.351 |

| 9. In my opinion, a real man would never say no to sex. | 0.725 | 0.717 | 0.630 | 0.718 | 0.668 | 0.511 |

| 10. In my opinion, men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women. | 0.643 | 0.674 | 0.618 | 0.632 | 0.649 | 0.602 |

| 11. In my opinion, men should use violence to get respect if necessary. | 0.735 | 0.746 | 0.662 | 0.750 | 0.733 | 0.690 |

| 12. In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal.a,b | −0.285 | −0.228 | −0.224 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 13. In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin.b | 0.486 | 0.534 | 0.287 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 14. In my opinion, men should figure out their personal problems on their own without asking others for help. | 0.655 | 0.700 | 0.483 | 0.662 | 0.672 | 0.448 |

| 15. In my opinion, a man should always have the final say about decisions in his relationship or marriage. | 0.742 | 0.751 | 0.620 | 0.760 | 0.746 | 0.645 |

| 16. In my opinion, a guy who spends a lot of time on his looks isn’t very manly. | 0.611 | 0.592 | 0.517 | 0.620 | 0.537 | 0.497 |

| 17. In my opinion, if a guy has a girlfriend or a wife, he deserves to know where she is all the time. | 0.603 | 0.634 | 0.572 | 0.597 | 0.705 | 0.580 |

Reverse-coded question.

Items were removed from final scale because factor loadings < 0.4 in at least one country.

Table A.3.

Man Box Scale scores for United States, United Kingdom, and Mexico.

| Item | Mean (standard error) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. (n = 1328) |

U.K. (n = 1225) |

Mexico (n = 1120) |

|

| 1. In my opinion, a man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect. | 2.10 (0.02) | 2.08 (0.03) | 1.91 (0.02) |

| 2. In my opinion, it is not good for a boy to be taught how to cook, sew, clean the house and take care of younger children. | 1.90 (0.03) | 1.96 (0.03) | 1.72 (0.03) |

| 3. In my opinion, a gay guy is not a “real man”. | 1.97 (0.03) | 2.04 (0.03) | 1.91 (0.03) |

| 4. In my opinion, a real man should have as many sexual partners as he can. | 1.93 (0.03) | 1.95 (0.03) | 1.65 (0.02) |

| 5. In my opinion, a guy who doesn’t fight back when others push him around is weak. | 2.35 (0.03) | 2.29 (0.03) | 2.30 (0.03) |

| 6. In my opinion, a man shouldn’t have to do household chores. | 1.88 (0.02) | 1.98 (0.03) | 1.65 (0.02) |

| 7. In my opinion, guys should act strong even if they feel scared or nervous inside. | 2.64 (0.02) | 2.49 (0.02) | 2.43 (0.03) |

| 8. In my opinion, it is very hard for a man to be successful if he doesn’t look good. | 2.45 (0.02) | 2.40 (0.02) | 2.35 (0.03) |

| 9. In my opinion, a real man would never say no to sex. | 2.03 (0.03) | 2.12 (0.03) | 2.09 (0.02) |

| 10. In my opinion, men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women. | 2.33 (0.03) | 2.30 (0.03) | 2.05 (0.02) |

| 11. In my opinion, men should use violence to get respect if necessary. | 1.78 (0.03) | 1.82 (0.03) | 1.51 (0.02) |

| 12. In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal.a | 1.78 (0.02) | 1.81 (0.02) | 1.78 (0.02) |

| 13. In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin | 2.49 (0.02) | 2.44 (0.02) | 2.40 (0.02) |

| 14. In my opinion, men should figure out their personal problems on their own without asking others for help. | 2.32 (0.02) | 2.23 (0.03) | 2.29 (0.02) |

| 15. In my opinion, a man should always have the final say about decisions in his relationship or marriage. | 2.19 (0.03) | 2.16 (0.03) | 1.98 (0.03) |

| 16. In my opinion, a guy who spends a lot of time on his looks isn’t very manly. | 2.32 (0.02) | 2.39 (0.02) | 2.19 (0.02) |

| 17. In my opinion, if a guy has a girlfriend or a wife, he deserves to know where she is all the time. | 2.41 (0.02) | 2.26 (0.03) | 2.07 (0.02) |

| Total mean score (17-items) | 36.9 (0.28) | 36.7 (0.29) | 34.3 (0.24) |

| Total mean score final scale (15-items) | 32.6 (0.26) | 32.5 (0.27) | 30.1 (0.23) |

| Total mean score short form (5-items) | 9.66 (0.10) | 9.87 (0.11) | 8.63 (0.09) |

Each item was assessed using a Likert-type Scale from 1 to 4 (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

Reverse-coded question.

Table A.4.

Item response theory discrimination factors for the Man Box Scale.

| Norms/items | a | b1 | b2 | b3 | Included in short form scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid masculine gender norms | |||||

| 6. In my opinion, a man shouldn’t have to do household chores. | 2.97 | −0.24 | 0.94 | 1.88 | Yes |

| 2. In my opinion, it is not good for a boy to be taught how to cook, sew, clean the house and take care of younger children. | 2.28 | −0.14 | 0.85 | 1.90 | No |

| 10. In my opinion, men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women. | 1.79 | −1.00 | 0.49 | 1.86 | No |

| Aggression and control | |||||

| 11. In my opinion, men should use violence to get respect if necessary. | 2.56 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 1.94 | Yes |

| 15. In my opinion, a man should always have the final say about decisions in his relationship or marriage. | 2.29 | −0.72 | 0.65 | 1.73 | No |

| 17. In my opinion, if a guy has a girlfriend or a wife, he deserves to know where she is all the time. | 1.67 | −1.15 | 0.46 | 1.97 | No |

| Hypersexuality | |||||

| 4. In my opinion, a real man should have as many sexual partners as he can. | 2.26 | −0.25 | 0.96 | 2.04 | Yes |

| 9. In my opinion, a real man would never say no to sex. | 1.92 | −0.76 | 0.76 | 1.91 | No |

| Self-sufficiency | |||||

| 1. In my opinion, a man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect. | 2.13 | −0.66 | 0.79 | 1.94 | Yes |

| 14. In my opinion, men should figure out their personal problems on their own without asking others for help. | 1.63 | −1.28 | 0.49 | 1.96 | No |

| Heterosexuality and homophobia | |||||

| 3. In my opinion, a gay guy is not a “real man.” | 1.99 | −0.32 | 0.78 | 1.80 | Yes |

| 12. In my opinion, straight guys being friends with gay guys is totally fine and normal. | N/Aa | No | |||

| Physical attractiveness | |||||

| 16. In my opinion, a guy who spends a lot of time on his looks isn’t very manly. | 1.48 | −1.46 | 0.47 | 2.06 | No |

| 8. In my opinion, it is very hard for a man to be successful if he doesn’t look good. | 1.01 | −1.96 | 0.25 | 2.53 | No |

| 13. In my opinion, women don’t go for guys who fuss too much about their clothes, hair, and skin. | N/Aa | No | |||

| Acting tough | |||||

| 5. In my opinion, a guy who doesn’t fight back when others push him around is weak | 1.44 | −1.22 | 0.32 | 1.98 | No |

| 7. In my opinion, guys should act strong even if they feel scared or nervous inside. | 1.18 | −1.89 | −0.13 | 2.05 | No |

Using full sample for all countries; a = discrimination, b1 = difficulty parameter for participant endorsing 0 vs. ≥1, b2 = difficulty parameter for participant endorsing 1 vs. ≥2, b3 = difficulty parameters for participant endorsing 2 vs. 3.

Excluded from Man Box Scale due to weak factor loadings (< 0.4).

Fig. A.1.

Total information function for the Man Box Scale.

This shows the test information function for the 15-item Man Box Scale, which is a measure of reliability.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amber L. Hill:Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Elizabeth Miller:Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Galen E. Switzer:Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Lan Yu:Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Brian Heilman:Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.Ruti G. Levtov:Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.Kristina Vlahovicova:Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.Dorothy L. Espelage:Writing - review & editing.Gary Barker:Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.Robert W.S. Coulter:Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

References

- Addis ME, 2008. Gender and Depression in Men. Clin. Psychol 15 (3), 153–168. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00125.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR, 2003. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help-seeking. Am. Psychol 58 (1), 5–14. 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group. APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Boys and Men. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/boys-men-practice-guidelines.pdf. Published August 2018. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- An X, Yung Y. Item Response Theory: What it is and How You Can Use the IRT Procedure to Apply it. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings14/SAS364-2014.pdf Revised 2014. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, 2000. Gender equitable boys in a gender inequitable world: reflections from qualitative research and programme development in Rio de Janeiro. Sex Relation Ther. 15 (3), 263–282. 10.1080/14681990050109854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C, 2005. Young men and the construction of masculinity in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for HIV/AIDS, conflict, and violence. World Bank Social Dev. Pap 26. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Contreras JM, Heilman B, Singh AK, Verma RK, Nascimento M. Evolving Men: Initial Results From the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES). Washington, D.C.: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Promundo. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Evolving-Men-Initial-Results-from-the-International-Men-and-Gender-Equality-Survey-IMAGES-1.pdf. Published January 2011. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet DC, Guran EL, Ramos MC, Margolin G, 2011. College students’ electronic victimization in friendships and dating relationships: anticipated distress and associations with risky behaviors. Violence Viet. 26 (4), 410–429. 10.1891/0886-6708.26.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J, Hedden SL, Lipari RN, Park-Lee E. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brush LD, Miller E, 2019. Trouble in paradigm: “gender transformative” programming in violence prevention. Violence Against Women 25 (14), 1635–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Harps S, Townsend R, Thomas G, et al. Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct. Rockville, MD: Westat. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/FULL_2019_Campus_Climate_Survey.pdf. Published October 2019, Accessed November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Kogan SM, 2017. Development and validation of the masculine attributes questionnaire. Am. J. Mens Health 11 (4), 941–951. 10.1177/1557988317703538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver MM, Lash SJ, Eisler RM, 2000. Masculine gender-role stress, anger, and male intimate abusiveness: implications for men’s relationships. Sex Roles 42 (5–6), 405–414. 10.1023/A:1007050305387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH, 2000. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med 50, 1285–1401. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keijzer B, 2001. Hasta Donde el Cuerpo Aguante: Genero, Cuerpo y Salud Masculina. UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Franchina JJ, Moore TM, Honeycutt HG, Rhatigan DL, 2000. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: effects of gender relevance of conflict situations on Men’s attributions and affective responses. Psychol. Men Masculinity 1 (1), 30–36. 10.1037/1524-9220.1.1.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Leemis RW, Hipp TN, Davis JP, 2018. Longitudinal examination of the bullying-sexual violence pathway across early to late adolescence: implicating homophobic name-calling. J. Youth Adolesc 47 (9), 1880–1893. 10.1007/s10964-018-0827-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes ZT, Alto KM, Jadaszewski S, D’Auria F, Levant RF, 2018. Content analysis of research on masculinity ideologies using all forms of the male role norms inventory (MRNI). Psychol. Men Masculinity 19 (4), 584–599. 10.1037/men0000134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Good GE, Hepper MJ, Hillenbrand-Gunn T, Wang L, 1995. Sexual and psychological violence: an exploratory study of predictors in college men. J. Men. Stud 4 (1), 59 10.1177%2F106082659500400105. [Google Scholar]

- Guillermo FJ, 2006. Ser Padres, Esposos e Hijos, Prácticas y Valoraciones de Varones Mexicanos. El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, Barker G. Unmasking Sexual Harassment – How Toxic Masculinities Drive Men’s Abuse in the US, UK, and Mexico and What We Can Do to End It. Washington, DC: Promundo-US. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Sexual-Harrassment-Brief-Final-To-Post.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, Barker G, Harrison A. The Man Box: A Study on Being a Young Man in the US, UK, and Mexico. Washington, DC and London: Promundo-US and Unilever. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TheManBox-Full-EN-Final-29.03.2017-POSTPRINT.v3-web.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, Guerrero-López CM, Ragonese C, Kelberg M, Barker G. The Cost of the Man Box: A Study on the Economic Impacts of Harmful Masculine Stereotypes in the United States. Washington, DC, and London: Promundo-US and Unilever. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Cost-of-the-Man-Box-US-Web.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentier PM, 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Lisak D, Roemer L, 2002. The role of masculine ideology and masculine gender role stress in men’s perpetration of relationship violence. Psychol. Men Masculinity 3 (2), 97–106. 10.1037/1524-9220.3.2.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Primack JM, Solimeo SL, 2017. Introduction to the special issue examining the implications of masculinity within military and veteran populations. Psychol. Men Masculinity 18 (3), 191–192. 10.1037/men0000126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K, 2011. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 6 (12), e29590. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantar TNS. http://www.tnsglobal.com/ Revised 2019. Accessed January 2019.

- Kelley K, Gruenewald J, 2015. Accomplishing masculinity through anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender homicide: a comparative case study approach. Men Masculinities 18 (1), 3–29 doi:10.1177%2F1097184X14551204. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel M, 2008. Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kivel P, 1998. Men’s Work: How to Stop the Violence. Hazelden Publishing, Center City, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, 2003. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 41, 1284–1292. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick JA, 1999. Survey research. Annu. Rev. Psychol 50, 537–567. 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemis RW, Espelage DL, Basile KC, Mercer LM, Davis JP, 2018. Traditional and cyber bullying and sexual harassment: a longitudinal assessment of risk and protective factors. Agress Behav. 1–12. 10.1002/ab.21808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone RM, Parrott DJ, 2015. Dormant masculinity: moderating effects of acute alcohol intoxication on the relation between male role norms and antigay aggression. Psychol. Men Masculinity 16 (2), 183–194. 10.1037/a0036427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, McCurdy ER, 2018. Toward diversifying research participants: measurement invariance of the male role norms inventory-short form (MRNI-SF) across recruitment method. Psychol. Men Masculinity 19 (4), 531–539. 10.1037/men0000138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Hall RJ, Rankin TJ, 2013. Male role norms inventory-short from (MRNI-SF): development, confirmatory factor analytic investigation of structure and measurement invariance across gender. J. Couns. Psychol 60 (2), 228–238. 10.1037/a0031545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, McDermott RC, Hewitt AA, Alto KM, Harris KT, 2016a. Confirmatory factor analytic investigation of variance composition, gender invariance, and validity of the male role norms inventory-adolescent-revised (MRNI-A-r). J. Couns. Psychol 63 (5), 543–556. 10.1037/cou0000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Hall RJ, Weigold IK, McCurdy ER, 2016b. Construct validity evidence for the male role norms inventory-short form: a structural equation modeling approach using the bifactor model. J. Couns. Psychol 63 (5), 534–542. 10.1037/cou0000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Good GE, Tager D, Levant RF, Maekowiak C, 2012. Developing a taxonomy of helpful and harmful practices for clinical work with boys and men. J. Couns. Psychol 59 (4), 591–603. 10.1037/a0030130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M, 1995. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict Men’s conflict with women. A 10-year follow-up study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 69 (2), 353–369. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott RC, Levant RF, Hammer JH, Borgogna NC, McKelvey DK, 2019. Development and validation of a five-item male role norms inventory using bifactor modeling. Psychol. Men Masculinity 20 (4), 467–477. 10.1037/men0000178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/q/3/mental_health_and_wellbeing_in_england_full_report.pdf/ Published 2016. Accessed 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Culyba AJ, Paglisotti T, Massof M, Gao Q, Ports KA, et al. , 2019. Male adolescents’ gender attitudes and violence: implications for youth violence prevention. Am. J. Prev. Med 58 (3), 396–406. Advanced online publication. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J, 2009. Health behaviors, prostate cancer, and masculinities. Men Masculinities 11 (3), 346–366 10.1177%2F1097184X06298777. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot DJ, 2009. Aggression toward gay men as gender role enforcement: effects of male role norms, sexual prejudice, and masculine gender role stress. J. Pers 77 (4), 1137–1166. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Zeichner A, 2003. Effects of hypermasculinity on physical aggression against women. Psychol. Men Masculinity 4 (1), 70–78. 10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter T, 2016. Breaking out of the “Man Box”: The Next Generation of Manhood. Skyhorse Publishing, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Barker G, 2008. Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men Masculinities 10 (3), 322–338. 10.1177/1097184X06298778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Barker G, Vergma R, 2012. Changing gender norms for HIV and violence risk reduction: a comparison of male-focused programs in Brazil and India. In: Obregon R, Waisbord S (Eds.), The Handbook of Global Health Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, West Sussex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Hughes L, Mehta M, Kidanu A, Verani F, Tewolde S, 2015. Changing gender norms and reducing intimate partner violence: results from a quasi-experimental intervention with young men in Ethiopia. Am. J. Public Health 105 (1), 132–137. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragonese C, Shand T, Barker G. Masculine Norms and Men’s Health: Making the Connections: Executive Summary. Washington, DC: Promundo-US. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Masculine-Norms-Mens-Health-Executive-Summary-1.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. , 2007. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks. Med. Care 45, S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Shirk SD, Sloan CA, Zeichner A, 2009. Men who aggress against women: effects of feminine gender role violation on physical aggression in hypermasculine men. Psychol. Men Masculinity 10 (1), 1–12. 10.1037/a0014794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers K, Aggleton P. Men and the HIV Epidemic. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme. Published 1999. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robb M, 2007. Youth in Context: Frameworks, Settings and Encounters. Sage Publications, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton S, 2002. Men, Masculinities, and Poverty in the UK. Oxfam GB, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM, 1994. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC (Eds.), Latent Variables Analysis: Applications for Developmental Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JP, Waldo M, Daniel D, 2005. Gender-role conflict and self-esteem: factors associated with partner abuse in court-referred men. Psychol. Men Masculinity 6 (2), 109–113. 10.1037/1524-9220.6.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slone LB, Norris FH, Murphy AD, Baker CK, Perilla JL, Diaz D, et al. , 2006. Epidemiology of major depression in four cities in Mexico. Depress. Anxiety 23, 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Item Response Theory Reference Manual: Release 15. https://www.stata.com/manuals/irt.pdf Revised 2017. Accessed January 2019.

- Steinfeldt JA, Vaughan EL, LaFollette JR, Steinfeldt MC, 2012. Bullying among adolescent football players role of masculinity and moral atmosphere. Psychol. Men Masculinity 13 (4), 340–353. 10.1037/a0026645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB, 1996. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J. Fam. Issues 17 (3), 283–316. https://doi-org.pitt.idm.oclc.org/10.1177%2F019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent W, Parrott DJ, Peterson JL, 2011. Effects of traditional gender role norms and religious fundamentalism on self-identified heterosexual men’s attitudes, anger, and aggression toward gay men and lesbians. Pyschol Men. Masc 12 (4), 383–400. 10.1037/a0023807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel D, Wade NG, Hackler AH, 2007. Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: the mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes towards counseling. J. Couns. Psychol 54 (1), 40–50. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel D, Heimerdinger-Edwards S, Hammer JH, Hubbard A, 2011. “Boys don’t cry”: examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. J. Couns. Psychol 58 (3), 368–382. 10.1037/a0023688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Bitman R, Hammer JH, Wade NG, 2013. Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. J. Couns. Psychol 60 (2), 311–316. 10.1037/a0031889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu L, Pulerwitz J, Burnett-Zieman B, Banura C, Okal J, Yam E, 2017. Inequitable gender norms from early adolescence to young adulthood in Uganda: tool validation and difference across age groups. J. Adolesc. Health 60, S15–S21. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way N, 2011. Deep Secrets: Boys’ Friendships and the Crisis of Connection. President and Fellows of Harvard College. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/. Published 2013. Accessed January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Espelage DL, Mitchell KJ, 2007. The co-occurrence of internet harassment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimization and perpetration associations with psychosocial indicators. J. Adolesc. Health 41 (6), S31–S41. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]